SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JEREMY PELT

(April 17-23)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

(April 24-30)

AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS

(May 1-7)

KARRIEM RIGGINS

(May 8-14)

ETTA JONES

(May 15-21)

YUSEF LATEEF

(May 22-28)

CHRISTIAN SANDS

(May 29—June 4)

E. J. STRICKLAND

(June 5-11)

TAJ MAHAL

(June 12-18)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

(June 12-18)

DOM FLEMONS

(June 19-25)

HEROES ARE GANG LEADERS

(June 26-July 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/amina-claudine-myers-mn0000748121/biography

Amina Claudine Myers

(b. March 21, 1942)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

A very original pianist who displays her gospel roots when she plays organ or sings, Amina Claudine Myers started studying music when she was seven. She sang with gospel groups in school. After moving to Chicago, Myers taught in the public schools, played with Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, and joined the AACM. She moved to New York in 1976 (where she would record with Lester Bowie and Muhal Richard Abrams), formed her own group, spent a few years in the early '80s in Europe, and toured with Charlie Haden's Liberation Music Orchestra in 1985. Amina Claudine Myers has recorded a diverse variety of music as a leader for Sweet Earth, Leo, Black Saint, Minor Music, and Novus.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/aminaclaudinemyers

Amina Claudine Myers

Amina Claudine Myers, Pianist, Organist, Vocalist, Composer, Master Improvisationalist, Actress and Educator. Ms. Myers has performed nationally and internationally throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia and North America. She is well known for her work involving voice choirs, voice and instrumental ensembles. Ms. Myers’ career in music began in her preteens and throughout high school directing church choirs, singing and playing gospel and rhythm and blues. She began playing and singing jazz in college in and around Arkansas. Myers studied concert music at Philander Smith College, Little Rock, Arkansas and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Music Education.

After moving to Chicago, Ill. in the 1960’s Ms. Myers taught in the public school system for six years. She attended Roosevelt University briefly and became a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in 1966. As an AACM member she started composing for voice and instruments. In 1975 she organized her very first choir for a musical she wrote called I DREAM.

In 1976 Ms. Myers moved to New York City where her career became even more multifaceted. In 1977 she moved into the theater realm, writing pieces for this medium. She acted and composed music for a number of Off-Broadway productions. Ms. Myers was the assistant musical director for AIN’T MISBEHAVIN' prior to it’s Broadway production. In 1978 she was choral director at SUNY at Old Westbury for a year.

Ms. Myers has recorded and/or performed with Archie Shepp, Charlie Haden’s Liberation Orchestra, James Blood Ulmer, Lester Bowie, Bob Stewart, Joey Baron, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Muhal Richard Abrams, Bill Laswell, Eddie Harris, Von Freeman, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Frank Lowe, Rahsaan Roland Kirk and other well known artists. Myers conducts workshops, seminar and residencies at colleges and universities, nationally and internationally.

There are eleven recordings released under Ms. Myers’ name: SAMA ROU (Songs From My Soul), piano and voice, Amina C Records; AUGMENTED VARIATIONS , Solo piano and voice, Vocal Quartet with Instrumental Trio and the Amina Claudine Myers Trio, Amina C Records; AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS LIVE in Bremen, Germany, Tradition and Modern Records; AMINA and IN TOUCH, RCA Novus; JUMPING IN THE SUGARBOWL and COUNTRY GIRL, Minor Music; THE CIRCLE OF TIME, Black Saint; AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS SALUTES BESSIE SMITH and SONG FOR MOTHER E, Leo Records; POEMS FOR PIANO, the piano music of Marion Brown, Sweet Earth Records.

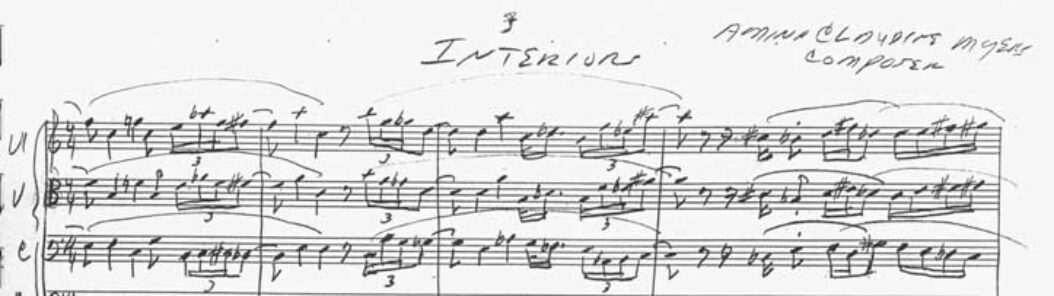

Her larger works include: INTERIORS, a composition for chamber orchestra conducted by Peter Kotik and performed by S.E.M. Orchestra. This piece was produced by the AACM and performed at the NYC Society of Ethical Culture; IM-PROVISATIONAL SUITE FOR CHORUS, PIPE ORGAN AND PERCUSSION; for 16 operatic voices, pipe organ and two percussionists; WHEN THE BERRIES FELL, eight voices, piano, Hammond B3 and percussion; A VIEW FROM THE INSIDE, a staged piece showing the workings of the inside mind. This included a chef from New Orleans and his assistant, a weaver, pianist, guitar/trumpet/voice (Olu Dara) and choreographer Rrata Christine Jones. Original art work by Ms. Myers was on the set; FOCUS, a piece written for piano, voice, electric bass and photographic images from Myers’ home town of Blackwell. HOW LONG BRETHREN, based on Negro Songs of Protest originally created by Helen Tamiris, was recreated by choreographer Diane McIntyre. The music score was created by Genevieve Pitot with original orchestra arrangements by Leslie Loth. The orchestral score was discovered with instrumentation only. Ms. Myers recreated and re-edited parts that were found in pieces from the archives of George Mason University. She conducted the symphony orchestras with choruses (The Wesley Boyd Singers of Washington, D.C at George Mason University; and the Western University Chorus from Western University). Myers has composed a few big band compositions performed by AACM musicians. She has performed works written by writer Ntozake Shange and other new works created by Diane McIntyre. Myers has collaborated in ongoing concerts with her soul sister Sola Liu where they are combining Chinese and Afro-American music traditions through singing, playing and dancing.

Most recently Ms. Myers has been performing original works of jazz, blues, gospel, spirituals and improvisations for the pipe organ. She has performed at Columbia University (St. Paul’s Chapel) NYC; St. Marks, Phil., Penn. and cities throughout North America, Germany, Hungary, Austria, Italy, Norway and Finland.

In 2010 Myers was commissioned by the Chicago Jazz Institute to compose and direct a composition for a 17 piece jazz orchestra in honor of the late and great composer, arranger and pianist Miss Mary Lou Williams’ 100th birthday. She was also commissioned by Baritonist Thomas Buckner to compose a composition for him. She titled it I WILL NOT FEAR THE UNKNOWN for baritone and piano. The performances were “lots of fun” says Myers.

Ms. Myers has received many grants and awards, including National Endowment for the Arts, Meet The Composer, and The New York Foundation for the Arts. She was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame 2001 and the Arkansas Jazz Hall of Fame 2010.

Amina Claudine Myers, Pianist, Organist, Vocalist, Composer, Master Improvisationalist, Actress and Educator. Ms. Myers has performed nationally and internationally throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia and North America. She is well known for her work involving voice choirs, voice and instrumental ensembles. Ms. Myers’ career in music began in her preteens and throughout high school directing church choirs, singing and playing gospel and rhythm and blues. She began playing and singing jazz in college in and around Arkansas. Myers studied concert music at Philander Smith College, Little Rock, Arkansas and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Music Education.

After moving to Chicago, Ill. in the 1960’s Ms. Myers taught in the public school system for six years. She attended Roosevelt University briefly and became a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in 1966. As an AACM member she started composing for voice and instruments. In 1975 she organized her very first choir for a musical she wrote called I DREAM.

In 1976 Ms. Myers moved to New York City where her career became even more multifaceted. In 1977 she moved into the theater realm, writing pieces for this medium. She acted and composed music for a number of Off-Broadway productions. Ms. Myers was the assistant musical director for AIN’T MISBEHAVIN' prior to it’s Broadway production. In 1978 she was choral director at SUNY at Old Westbury for a year.

Ms. Myers has recorded and/or performed with Archie Shepp, Charlie Haden’s Liberation Orchestra, James Blood Ulmer, Lester Bowie, Bob Stewart, Joey Baron, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Muhal Richard Abrams, Bill Laswell, Eddie Harris, Von Freeman, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Frank Lowe, Rahsaan Roland Kirk and other well known artists. Myers conducts workshops, seminar and residencies at colleges and universities, nationally and internationally.

There are eleven recordings released under Ms. Myers’ name: SAMA ROU (Songs From My Soul), piano and voice, Amina C Records; AUGMENTED VARIATIONS , Solo piano and voice, Vocal Quartet with Instrumental Trio and the Amina Claudine Myers Trio, Amina C Records; AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS LIVE in Bremen, Germany, Tradition and Modern Records; AMINA and IN TOUCH, RCA Novus; JUMPING IN THE SUGARBOWL and COUNTRY GIRL, Minor Music; THE CIRCLE OF TIME, Black Saint; AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS SALUTES BESSIE SMITH and SONG FOR MOTHER E, Leo Records; POEMS FOR PIANO, the piano music of Marion Brown, Sweet Earth Records.

Her larger works include: INTERIORS, a composition for chamber orchestra conducted by Peter Kotik and performed by S.E.M. Orchestra. This piece was produced by the AACM and performed at the NYC Society of Ethical Culture; IM-PROVISATIONAL SUITE FOR CHORUS, PIPE ORGAN AND PERCUSSION; for 16 operatic voices, pipe organ and two percussionists; WHEN THE BERRIES FELL, eight voices, piano, Hammond B3 and percussion; A VIEW FROM THE INSIDE, a staged piece showing the workings of the inside mind. This included a chef from New Orleans and his assistant, a weaver, pianist, guitar/trumpet/voice (Olu Dara) and choreographer Rrata Christine Jones. Original art work by Ms. Myers was on the set; FOCUS, a piece written for piano, voice, electric bass and photographic images from Myers’ home town of Blackwell. HOW LONG BRETHREN, based on Negro Songs of Protest originally created by Helen Tamiris, was recreated by choreographer Diane McIntyre. The music score was created by Genevieve Pitot with original orchestra arrangements by Leslie Loth. The orchestral score was discovered with instrumentation only. Ms. Myers recreated and re-edited parts that were found in pieces from the archives of George Mason University. She conducted the symphony orchestras with choruses (The Wesley Boyd Singers of Washington, D.C at George Mason University; and the Western University Chorus from Western University). Myers has composed a few big band compositions performed by AACM musicians. She has performed works written by writer Ntozake Shange and other new works created by Diane McIntyre. Myers has collaborated in ongoing concerts with her soul sister Sola Liu where they are combining Chinese and Afro-American music traditions through singing, playing and dancing.

Most recently Ms. Myers has been performing original works of jazz, blues, gospel, spirituals and improvisations for the pipe organ. She has performed at Columbia University (St. Paul’s Chapel) NYC; St. Marks, Phil., Penn. and cities throughout North America, Germany, Hungary, Austria, Italy, Norway and Finland.

In 2010 Myers was commissioned by the Chicago Jazz Institute to compose and direct a composition for a 17 piece jazz orchestra in honor of the late and great composer, arranger and pianist Miss Mary Lou Williams’ 100th birthday. She was also commissioned by Baritonist Thomas Buckner to compose a composition for him. She titled it I WILL NOT FEAR THE UNKNOWN for baritone and piano. The performances were “lots of fun” says Myers.

Ms. Myers has received many grants and awards, including National Endowment for the Arts, Meet The Composer, and The New York Foundation for the Arts. She was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame 2001 and the Arkansas Jazz Hall of Fame 2010.

Ms. Myers resides and teaches privately in New York City.

Amina Claudine Myers: From Mozart to Miles and Beyond

byAllAboutJazz

All About Jazz: While your recordings have mostly highlighted your jazz piano and songwriting, you have also done a lot of choral and theatrical work with bigger ensembles. How difficult is it finding opportunities to present large-scale works?

Amina Claudine Myers: I'm doing workshops and seminars in the States but most of my work is being done in Europe, the voice choir and pipe organ work. Improvisation Suite in 1979 was one of my first pieces for choir and organ. I wanted to showcase the operatic voice in an improvisational setting. That was performed at Saint Peter's Church and that's how I started playing the pipe organ. I have music for choir, but it's too much for a small group, I need a larger group.

Diane McIntyre, the choreographer, and

I are doing an ongoing project where I was able to conduct an orchestra

in a piece called How Long Brethren by the great dancer Helen Tamaris.

She came along during the Martha Graham days. She took black protest

songs—How long, how long, must my people suffer—she took these songs and

made a piece that played for a month on Broadway. Diane McIntyre wanted

to recreate this piece. I had to recreate the scores, some of these

pieces were missing. We did that in 1991 and in 2006. Those are giant

productions; those chances don't come along very easily.

AAJ:

But theatrical productions weren't anything new to you, even back in

1991. Weren't theater pieces a part of the AACM's early work?

ACM: Muhal Richard Abrams wrote a play called The Dream, back in Chicago [in 1968] with no written dialogue, with Lester Bowie and Roscoe Mitchell in it. It ran every weekend for a month. I played Joseph Jarman wife. He was a musician and I was a real materialist, always on him about earning more money.

It

was so creative back then—Muhal painting, Joseph doing his theater—they

were all just creating and writing. Roscoe would be running around with

a stovepipe hat and a cigar box and he'd reach in the box and give you

something and then the next week he'd ask you for something to put in

the box. I started writing poems and painting. And everybody encouraged

you, people would play with you. That was very inspiring. Something was

going on all the time.

And then when I came to New York, Amiri Baraka had written a play called Primitive World.

The world had been destroyed by the primitive money-makers. They put me

behind the stage playing piano for that, but I thought of myself as an

actor and a singer. Piano just came natural to me.

AAJ:

You've worked in so many styles, from composed music to jazz and even

leaning toward rhythm and blues. Where did your music education begin?

What was the first music you performed?

ACM:

I started studying European classical piano when I was five or six; I'd

go over to the next town from Blackwell, which had a population of

about 5,000. That was a very rare thing back then, a little black girl

studying classical piano. At age seven I moved to Dallas with my aunt.

There was a vacation Bible school and for some reason the pianist they

had couldn't play these simple songs they had and I could play it and

they thought it was wonderful. I was Methodist, but these ladies from

the Baptist church got a group of us together; they were putting on

Christmas plays and we were trying to emulate the gospel quartet

singers.

We could get the country and western

stations—that Hank Williams was bad!—but the quartet singers would

travel around and come to the church and we'd try to emulate them. Those

quartet singers would come to town and everybody in town would come.

All the white people would sit in back! But that music brings people

together. Then I got into high school and I began to sing in the choir,

that's how I got into choral music. There's something to that sound, all

those voices together, that I try to get in my choral music.

And

then when I was about 15, we moved back to Arkansas and put a group

together with my childhood friends. When we sang gospel we were called

the "Gospel Four" and then we'd be called the "Royal Hearts" when we did

popular songs. We opened for the Staple Singers when they came through.

I

went to college to be a schoolteacher but then this girl came up to me

and said "I got a job for you playing in a nightclub." I said, "Girl, I

can't do that." I knew "Greensleeves," "Misty," a few other things. But I

went down there and I learned the blues. And the people kept bringing

me in and it was like God was hitting me on the head and saying, "You're

supposed to be a musician." And my family was always very supportive.

Here I was, 18 years old, and I had a rhythm and blues band. One time Rahsaan Roland Kirk

came in. I didn't know that, but then years later we were playing in

one of the clubs in New Jersey and he came up and said, "Are you

Claudine Myers?" He remembered me by my voice. I couldn't believe that.

I

got jobs with Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt. I worked with Dexter

[Gordon]. And this guy came in, Cozy Eggleston and we got together and

[drummer, AACM member and Sun Ra

Arkestra alum] Ajaramu heard me and he said he wanted to form an organ

group. So I got with Ajaramu and Cozy always said he stole me away! But

that's how I got to the AACM.

AAJ: You've

recorded piano duos with Muhal Richard Abrams and then you've recorded

songs that could be done by Alicia Keys. How do you balance those

different approaches to writing and performing?

ACM:

It can be very hard, but it's a system. First I was writing poems and

those songs came out of those. The first songs I remember doing were in

[her stageplay] I Dream, around 1975. It was supposed to be a story told just with songs.

I never thought of my music as avant-garde, but other people do. Now I'm writing this piece for viola, piano and voice and I'm concentrating on how to showcase the full range of the voice. I purposely want those kind of operatic voices for the kind of sound I want. I was raised around the gospel, the country and western, I love John Lee Hooker, the rural blues. But then I was in love with Miles Davis. I fell in love with Mozart's Requiem and all that choral music. I've been fortunate to be exposed to a lot of forms of music.

Selected Discography:

Amina Claudine Myers, The Circle of Time (Black Saint, 1983)

Frank Lowe, Live From Soundscape (DIW, 1982)

Muhal Richard Abrams, Duet (feat. Amina Claudine Myers) (Black Saint, 1981)

Amina Claudine Myers, Salutes Bessie Smith (Leo, 1980)

Amina Claudine Myers, Poems for Piano: The Piano Music of Marion Brown (Sweet Earth, 1979)

Amina Claudine Myers

A source for news on music that is challenging, interesting, different, progressive, introspective, or just plain weird

Amina Claudine Myers Birthday Celebration on March 21

Source: ARTS FOR ART.

Amina Claudine Myers Birthday Celebration

Vision Festival 25 Lifetime Achievement Honoree

March 21, 2021 – 3:00pmSolo Piano Performance Streaming Live from Scholes Music Studio

A special solo piano performance celebrating the birthday of Vision Festival 25 Lifetime Achievement Honoree Amina Claudine Myers. Following the performance, Myers will participate in the Artist Talk with Patricia Nicholson.

Funds raised support the lifetime achievement programming at the Vision Festival, including the creation of a new biopic on Myer’s art and career.

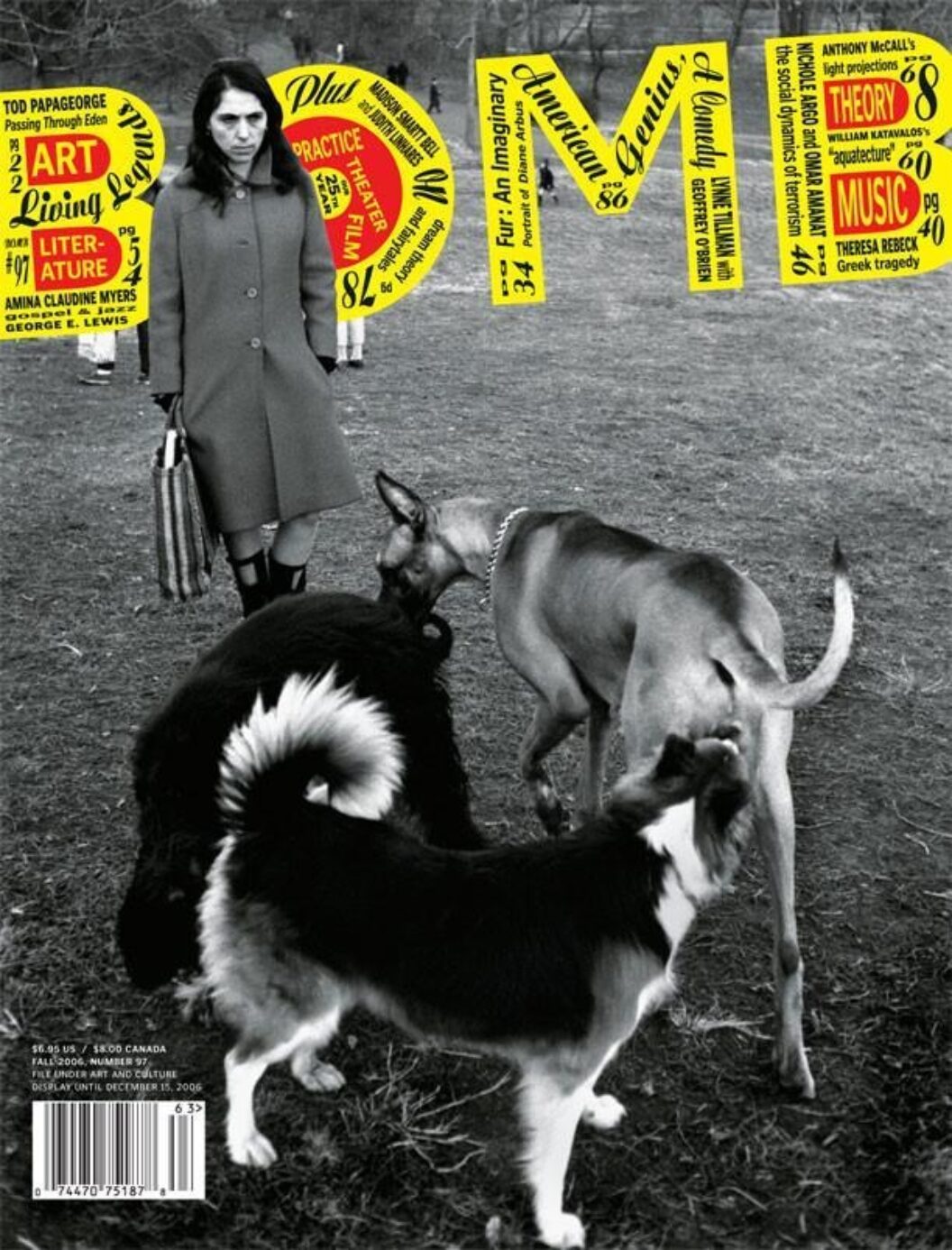

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/amina-claudine-myers/

Amina Claudine Myers by George Lewis

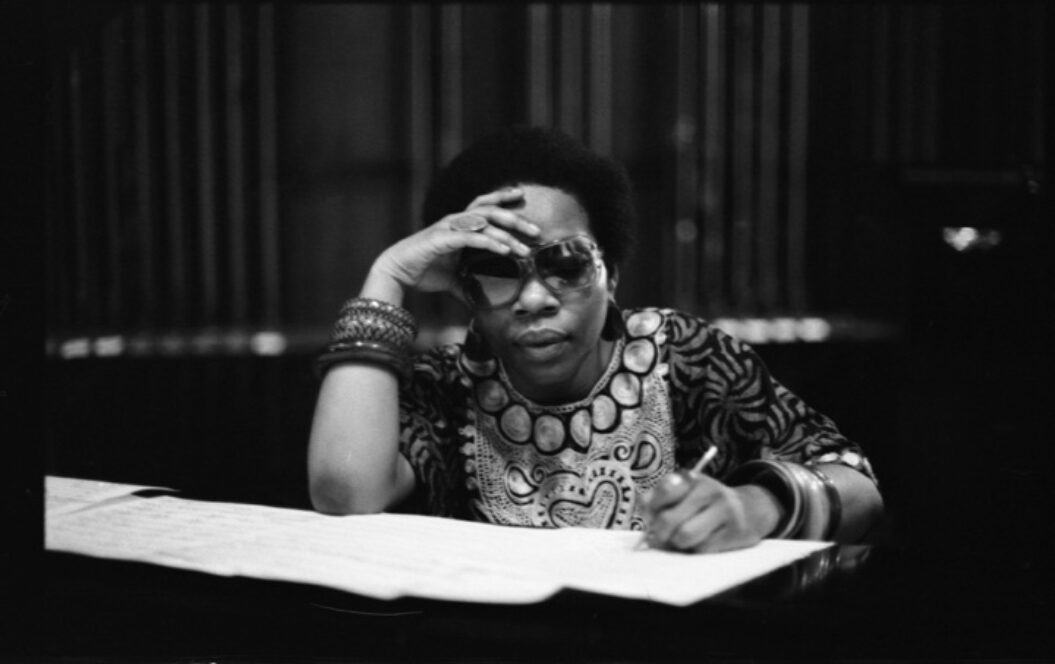

Amina Claudine Myers composing at the piano, New York, 1977. All photos courtesy of George Lewis

Amina Claudine Myers composing at the piano, New York, 1977. All photos courtesy of George LewisA number of younger scholars working on new music have noted that widely accepted historicizations appear to premise the very identity of American experimental music upon the erasure of African-American forms, histories, and aesthetics, despite the ongoing centrality of blackness to the international identity of American music. As it happens, the form most often assumed as the “invisible man” of American experimentalism is that of a black woman. Among the 90+ oral histories I compiled for my forthcoming book on the AACM, Myers’s observations numbered among the most trenchant and vivid, and in this interview I wanted to explore the articulations between sound, history, and place that are central to her work. Along the way, I learned something about the limitations of standard interviewing practice as a tool for investigating complex issues that are difficult to verbalize—the questions with which thinkers have engaged throughout the centuries without identifying even provisionally satisfying answers. Equally unsatisfying, however, is the Armstrong-Wittgenstein Evasion, i.e., “If you have to ask, you’ll never know,” or “What we cannot speak of we must pass over in silence.” So this interview was an experiment in speaking past the silence, with a creative musician whose modesty and generosity always precedes her formidable reputation.

George Lewis You were brought up in Blackwell, Arkansas, a small village with about how many people?

Amina Claudine Myers No one really knows the population, but I guess about 250. A little hamlet.

GL Rural, spread out.

ACM Definitely. People lived off the main highway. Some lived back in the woods, some lived back in a clearing where they grew crops, and some lived right up on the highway where the houses were closer together. You had the grocery store, the post office, the train stop, the churches.

GL Maybe you could talk a little bit about the sounds you heard as a child.

ACM The main sounds I remember hearing were the crickets at night. And there were the birds, and we had this plant that grew all around the house, like lilacs, that attracted the bees, so there would be that humming sound. Then about 9:00 every night the train would come by. You’d hear it from way off, that whistle blowing. And you heard the bells of the cows when they were coming in.

GL You had cows?

ACM My grandmother had cows. They took them out to the pasture in the morning, and when I got old enough, my cousin and I would go get them. We’d have to listen to see where they were. They would wander off and eat, and we would have to find them.

And then the chickens would come running to the house when you got ready to feed them. You’d hear their feet—it was like a patter of chicken feet. (laughter)GL For me, a city boy, the idea of a chicken foot having a sound—

ACM Yeah, they would hear that back door and run to you as a group, maybe about 15 or 20. The sounds of chicken feet running in the dirt, I can hear it in my mind. And you’d hear the rooster; he would come to the back door and crow. My grandmother would say, I knew you were coming, the rooster crowed.

GL That sounds kind of like a spiritual thing embodied within the sound.

ACM You could say that. They also used to say that if you dropped a dishrag, company was coming. You ever hear that?

GL No.

ACM Oh, yeah. If I drop a dishrag now, I figure somebody’s coming. Now, my hand would itch—

GL When company’s coming?

ACM When I’m going to get money. It happened the other day. I got some money by surprise, and my hand had been itching, the palm of my hand.

GL Maybe that’s why they call it “scratch.”

ACM That’s good (chuckles). Anyway, Blackwell was peaceful, the sounds of nature.

GL Peaceful, with all that going on?

ACM It was calming. It wasn’t chaotic or intense. It was just the normal everyday life.

GL When you went to school, what was it like?

ACM Very small. It was two rooms. You could hear the children in the next room reciting, a lot of reciting. In my class there were about three of us. The other class would maybe have five or six.

GL Was there a time when all the kids would get together?

ACM At recess. We played “Ring Around the Rosy” and “Jumpin’ in the Sugar Bowl.”

GL That’s like that composition of yours—

Jumpin’ in the sugar bowl, jump jump jump

Jumpin’ in the sugar bowl, jump jump jump.

ACM That’s where it came from. There would be a big cluster of people in a circle. You’d end up stepping on people’s feet, and you’d laugh and it would break up.

GL I was going to ask you how all these sounds were a factor in how you work as a musician, but that seems like an obvious example right there. I didn’t know that it came from when you were a child. Did you jump rope too?

ACM Yeah, the double dutch, when you run in while the rope is turning. That’s all about timing, so you don’t trip up the rope. They do it as fast as they can.

GL There’s a book that just came out, let me see if it’s here—

ACM Oh, Games That Black Girls Play. George, I’ve got to get this.

GL It’s a great book. A lot of people are writing stuff on music now that’s not the standard stuff. This one’s by Kyra Gaunt. She’s a musician too.

ACM (examining the book) That double dutch was something.

GL I look at it as, everybody had to have timing—the people turning the rope, and everybody jumping.

ACM That’s right, you had to have rhythm. The girls on the end, they’d say, Ready? Then they’d start, and you had to time it going in. You could turn around in it, do all kinds of stuff. Some people would get slick, you know.

GL It seems that you never forget how to do it. I saw my aunt doing it when she was in her fifties, right there with the kids.

ACM Here’s another really good game that deals with rhythm. This is the rhythm you’ve got going: (slap thigh, clap) One, two! (slap thigh, clap) Two, four! (slap thigh, clap) Four, six! (slap thigh, clap) Six, one! (slap thigh, clap) If your number is called, you must answer back without missing a beat.

GL Everybody had their own number?

ACM Yes. Say I’m one, you’re two. (slap thigh, clap) One, two! (slap thigh, clap)

GL (tries with limited success)

ACM You have to answer right away. It starts like this. First you set the rhythm. You hit each other’s hands.

GL Let me try again.

ACM We’ll do it slow.

GL Okay.

ACM (slap thigh, clap) One, two!

GL (slap thigh, clap) Two, three!

ACM (slap thigh, clap) Three, two!

GL (slap thigh, clap) Two, one!

ACM (slap thigh, clap) One, six—and so on.

GL It’s like a march, or a hip rhythm.

ACM It was called “Rhythm,” if I’m not mistaken.

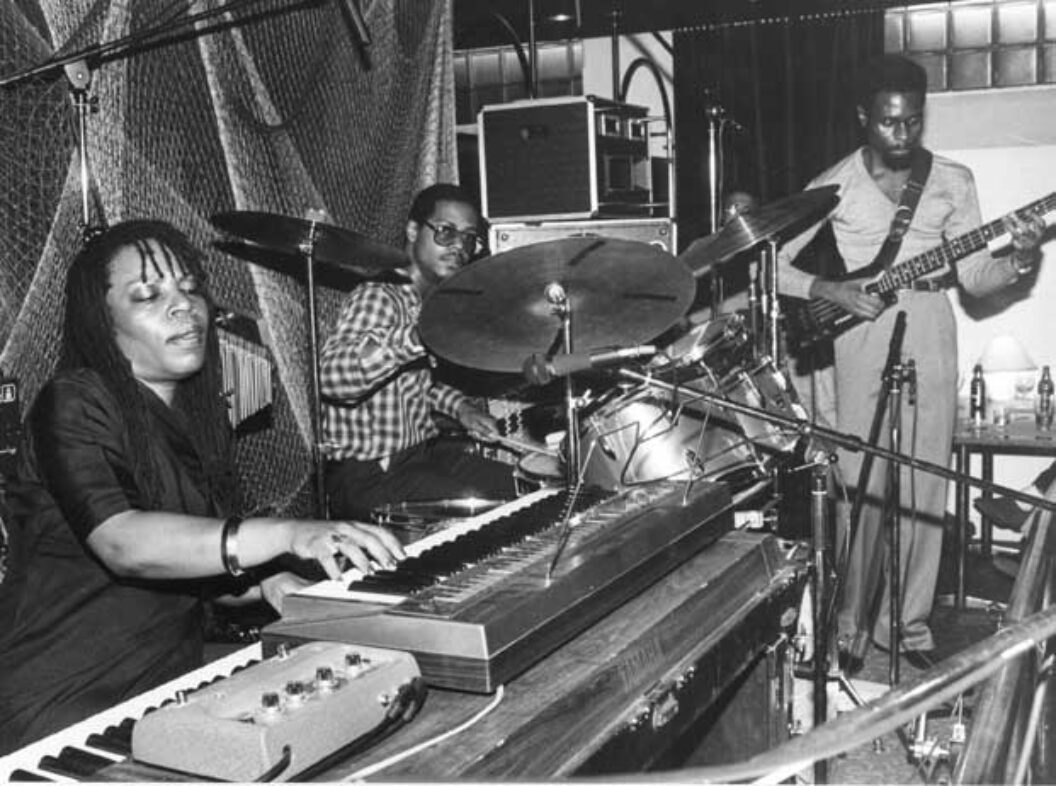

Amina Claudine Myers (organ), Skip James (Tenor Saxophone), Ajaramu (drums), CA. 1964.

GL I want to ask you about the sounds of church, because you were so involved with all those choirs. It was mostly women, right?

ACM In Arkansas you had those quartets

that traveled to the country churches. Some recorded, like the Swan

Silvertones and the Five Blind Boys of Alabama—there were several of

those “Blind Boy” groups—but there were musicians who weren’t recorded

who were wonderful. Before, they were just a cappella. The guitar came

later. They would sing in harmony and they kept their rhythms by

slapping their thighs. It was something. That stuff would be rollin’.

You’d hear the whole church stomping. So when I first started singing

with a group down in Dallas, we tried to emulate the quartet singers by

slapping our thighs.

GL These were male quartets.

ACM Yes. My grandmother used to listen

to Rosetta Tharpe [a pioneering gospel singer, songwriter, and recording

artist who attained great popularity in the ’30s and ’40s]. Rosetta was

bad. So this past spring, I played for Bethel [AME Church] on 132nd

Street. The women sing every fifth Sunday, and then they have Women’s

Day in May. They had this woman preacher, and she was bad. I started

playing—something just told me to do it—I started playing behind her.

She said, I’m going, da-da, dah! and I went, Hmm da-da dah!

And then she raised it and went to the climax, and when she stopped I

kind of finished it off, brought it back down. Later the choir director

said, Girl, the way you played it, I wish I could do that. I said, I

didn’t want to overdo it. I hope she didn’t mind. They said, I think

maybe you could have done more.

GL It’s not so different from what I’ve heard you do in a concert.

ACM I know, but I had never done it in a

church setting. I just go by the feeling of it. It’s blues changes, the

minor thirds, the flat fifths. It’s interesting how it all works as

one, the minister, the music, the congregation. Some churches don’t do

that, conservative churches where they have hymns and anthems, but for

those where the spirit hits, the musicians help the minister build up

their sermons. That’s one thing you hear in the churches, a lot of

shouting.

GL I remember that they would “get happy,” they called it, go into a trance.

ACM One time one of my cousins hit me,

and it looked like some kind of electricity was running through her

body. I looked at her, and she looked like she didn’t know she had done

that.

GL What you were playing at Bethel, I

heard it as a thing where you’re finding out stuff about the preacher

through the playing, the same as if you’re playing music with somebody.

Playing with people in these free-improvisation contexts, too, I can

figure out a lot about the other musicians—where they want to take the

music, the messages that they are interested in or capable of receiving.

And I’m sure they’re finding this out about me too. Have you had these

kinds of experiences?

ACM Well, there’s one musician, a

bassist; it seems like he always knows the right thing to do that works

with the music. Technically he can do it, and he has feeling and soul.

He knows what I’m doing and where I’m going. There’s no ego.

GL How do you tell when somebody doesn’t have an ego in the music—or, how does ego come out in the music?

ACM Well, with this other bass player,

when I played my music with him, he took it the way he wanted to go. I

had no control, and I didn’t know how to deal with that. That was

strange.

GL If all this comes out in the music, can you be dishonest in the music, when you’re playing with somebody? Can you trick people?ACM I don’t think so, no. You can’t fake the music. It’s a real thing.GL You told me about Ajaramu [the

drummer, an original member of the AACM], that he believed in playing

what you hear. What does that mean?

At that time, I found myself in a position that I really didn’t want to be in. I was shy about playing jazz onstage. My dream was to be a singer and an actress. Piano playing was natural, and then I started studying. I hated those jam sessions at McKie’s in Chicago, with Gene Dinwiddie and all them coming in with “All The Things You Are,” and “There Will Never Be Another You.” Ajaramu and I, and Skip James, we were the house band, and I had to try and pick up those tunes. I was so naive, George.

GL But what about once you leave the blues and that context, like in the record we made with Muhal in 1980, “Spihumonesty,” with Youseff Yancey playing the theremin? Is there any reason to fear in an open context like that? Or in the duo piano record you made with Muhal?

ACM With Muhal it was totally open, once you got past the reading part. Henry Threadgill’s music is hard, and Roscoe’s [Mitchell] and Leo’s [Smith]. [Anthony] Braxton, his stuff looks hard, but you just have to keep up with the time span. I found that with Leo too. He has some tricky stuff, so you have to keep up. They go for the overall sound. This is what I tell my musicians now—this is just a feeling, don’t worry about the music. The music is a guide; just do your thing. The charts Muhal wrote for the AACM—I was inexperienced, in from the country (laughter), and his music seemed hard. You had to practice.

GL But we learned how to play it.

ACM Like with Coltrane, when he came out with “Ascension.” Ajaramu came home and put the record on, and I said, Ooh, take that off, it’s too much. Later I realized that with Coltrane all these sounds were going on at the same time, and if you listen, you listen to the complete network of sound, you are able to hear it all together.

GL Jeff Donaldson [one of the founders of the Africobra art movement] said that some of his paintings were doing something like what the musicians were doing with sound—lots of colors and shapes and directions going on at the same time, which was too much for some people in the art world. “Too many notes,” you know?

ACM But if you train yourself to accept things, your brain will adjust.

GL That’s interesting: you have to learn to accept things.

ACM Just close your eyes and you’re surrounded with sound, like with the Art Ensemble. You’re living within the sound, and it takes you places where you’re just dealing with life.

GL But what about once you leave the blues and that context, like in the record we made with Muhal in 1980, “Spihumonesty,” with Youseff Yancey playing the theremin? Is there any reason to fear in an open context like that? Or in the duo piano record you made with Muhal?ACM With Muhal it was totally open, once you got past the reading part. Henry Threadgill’s music is hard, and Roscoe’s [Mitchell] and Leo’s [Smith]. [Anthony] Braxton, his stuff looks hard, but you just have to keep up with the time span. I found that with Leo too. He has some tricky stuff, so you have to keep up. They go for the overall sound. This is what I tell my musicians now—this is just a feeling, don’t worry about the music. The music is a guide; just do your thing. The charts Muhal wrote for the AACM—I was inexperienced, in from the country (laughter), and his music seemed hard. You had to practice.GL But we learned how to play it.ACM Like with Coltrane, when he came out with “Ascension.” Ajaramu came home and put the record on, and I said, Ooh, take that off, it’s too much. Later I realized that with Coltrane all these sounds were going on at the same time, and if you listen, you listen to the complete network of sound, you are able to hear it all together.

GL Jeff Donaldson [one of the founders of the Africobra art movement] said that some of his paintings were doing something like what the musicians were doing with sound—lots of colors and shapes and directions going on at the same time, which was too much for some people in the art world. “Too many notes,” you know?

ACM But if you train yourself to accept things, your brain will adjust.

GL That’s interesting: you have to learn to accept things.

ACM Just close your eyes and you’re surrounded with sound, like with the Art Ensemble. You’re living within the sound, and it takes you places where you’re just dealing with life.

Amina Claudine Myers, “Interiors” (score excerpt), 1995

Amina Claudine Myers, “Interiors” (score excerpt), 1995 GL It seems that one of the hardest things is to teach people how to listen to things, how to hear things in a different way. One of the things I’ve noticed in teaching classes is that when I ask people to describe new and unfamiliar music, they can’t. They don’t have the vocabulary for it. What they can do is make up an impromptu movie scenario instead, a music-video scene. It’s not like synesthesia, seeing sounds or hearing colors; it’s more like they hear a sound track and they create the movie. More and more, in this culture, sound’s major purpose is to serve as accompaniment for moving pictures.

ACM They also connect those sounds with things that have happened in the past. The sounds have to go along with something instead of being on their own.

GL One thing they said about Coltrane was that his music had a spiritual component. How might one learn about spirituality through sound? Do you feel that your approach to spirituality was developed in part through sound?

ACM Spirituality is something you have to be born with. Coltrane’s Olé, that was deeply spiritual. Spirituality is being in touch with the soul of yourself and the universe. It’s not for me to say who is spiritual and who is not. Like Miles, I couldn’t say if he was spiritual, but he was a beautiful musician and I loved the music. He had soul, but soul and spirituality are two different things, though they do go hand in hand.

GL What about the emotional thing, when people say that they can hear emotion in someone’s music? Do you feel that you hear that?

ACM Yes, because when I listen to, say, Dinah Washington—they say she was difficult, but I feel she was beautiful. What she was doing with this music—she had a way of expressing where you could feel the hurt and pain she went through. Look at Mary J. Blige. I don’t know much about her, but when I first heard her, I liked her. Her feelings come through in all her music.

GL When you play music, is it that you are expressing emotions or that you are feeling the emotions?

ACM I try to portray the feeling of what the song is about. I try to put that feeling across. I try to paint pictures, make it visual.

GL So that’s different from saying, I’m going to be “emotional” now.

ACM Oh, no, I can’t do that. For me I try to feel good, so that I can be relaxed and let the Creator work through my hands. Just focus and let the spirit come through the music.xxx

GL When I did the book interviews, the men I interviewed hardly ever connected the music with their personal relationships, but practically all the women did, including you. For example, you had that long relationship with Ajaramu.

ACM Ajaramu was a creative brother in my life, and we were friends more than anything else. I realized that later. He’s the one who brought me into the AACM. Ajaramu heard me with [tenor saxophonist] Cozy Eggleston, and Cozy had some heated discussions with Ajaramu. He kept saying Ajaramu “stole” me from him (chuckles).

I really didn’t feel qualified. I didn’t know enough. I went along with things, but when I got into the AACM, everybody was so respectful. Muhal showed me stuff on the piano, Roscoe showed me stuff. It was a lot to digest, but the AACM members accepted me. After a while I started formulating things in my mind that I wanted to do, and that was when I split with Ajaramu. I said, I no longer want to do Ajaramu’s thing. I want to do my thing. Like with Gene Ammons: after the third time we went on tour, I started hearing other stuff and wanting to do it, but with Jug I had to stay within the framework, the sound that Jug and them had. So I left Jug. It took a lot of nerve. Another lady told me that it’s hard to play music together with your husband or mate. Shirley Scott and Stanley Turrentine, I heard that they used to have disagreements back in the dressing room, and then they’d come out on stage and play, united as one. But I had to learn how to separate. I would go on the stage mad and Ajaramu would tell me, “Look, you have to leave your personal stuff at home.”

GL Let’s say that you’re not working with them as a musician. Women always talked about the situation of having children and how that affected the music, and whether the men were supportive.ACM I had one boyfriend who would try to sabotage me. I didn’t see it then. I’m not blaming him—he was the way he was. I was blindly thinking that I was in love, but I would feel terrible when I went on tour or to do a gig. It was never, “How was your gig?” But when you get onstage, none of that is there; it’s all about the music.

GL We haven’t talked about Papa [Kanguele Sissokho, Amina’s late husband, a translator fluent in French, English, Bambara, and Wolof, among other languages], and I didn’t really want to go into that too much, but I want to ask you what it was like going to Senegal for the funeral.

ACM It was wonderful. After passport control I was greeted by four or five men with their prayer beads and white robes. There were some others downstairs with the body, getting ready to take it over to the mosque. The spirituality of the country hit me as soon as I got there. It felt good. They were so warm. They had everything prepared for me. I didn’t have to do anything. The women had their heads covered with their African dress, modest, with the fans. They invited me to dinner. There was a lot of love there. I wish Papa had seen me over there. I guess he sees it now, but I wish he could have known how much I loved his country. He probably thought I wouldn’t like it, knowing how I am, Americanized and Westernized, but like I told him, I’m from the country. I loved Dakar. There was a natural breeze.

GL The weather reminded me of San Diego, beautiful.

ACM Even though it’s a struggle, everybody is just living and doing their thing. It was beautiful.

GL Was there a service for him?

ACM At the mosque they had prayers. They said the women could come to the grave afterward. They took the body, washed him, said the prayers, and took him straight to burial.

GL He was brought up as a Muslim.

ACM Yes. The family wanted him buried close to home. There was a man there with the Qu’ran and his prayer rug, who was out there all day, praying. They said, “This is what we do. They’ll do the same for me when I leave this earth.” It was about tradition, pride, and dignity. We walked to the grave, and there was a wooden marker with Papa’s name. Then out by his house they had a tent set up, and they had someone to speak on him.

GL Did they have any music there?

ACM No, just a man speaking. When I left the gravesite they called us and said that there were so many people that we wouldn’t be able to get through. They had blocked the streets; you could not get up to the house. There were over 200 people every day coming to the condolences to hear about Papa.

GL When I went out there last year, people received me with incredible hospitality. I saw right away that Papa’s family was very highly respected. His great-niece is a well-known contemporary artist [Madeleine Bomboté].

ACM I went to the museum and they had an exhibit of her work.

GL What was your impression of how Dakar sounded?

ACM It was alive. I liked the energy of the sounds. You had people walking, the wagons with the horses, mixed with the cars. Traffic was really bad, but you know, the people would be patient. Just the sounds of everyday life. You had the animals, the goats, standing around eating and baa-ing. I loved it. Everything just worked well together. Papa’s cousin said, It’s surprising how this country is constantly building, with no money. You always heard hammering and stuff.

Amina Claudine Myers Ensemble, 1980s. Reggie Nicholson, drums; Jerome Harris, bass

ACM Well, I’m working on a choreographed piece on Harriet Tubman, for instrumental ensemble and dancers. It’s called “General Harriet Tubman.” It starts off with the banjo, and I’ve been writing the banjo part, with people dancing, stepping. While the banjo is playing you hear the basses and trombones and tubas come in, lots of space, sneaking in. That means that the people are sneaking out, slowly. It goes into a rock beat, they’re marching out, they’re heading North, Doum doum DOUM doum, DOOOOM / Doum doum DOUM doum, DOOOOM … And then there are the blackouts with flutes and piccolos, and the string ensemble.

GL So the writing portrays these lives in a very direct way.

GL How many instruments are you going to use?

GL It’s like a chamber orchestra, but with drums.

ACM Yeah, for the rock beat, regular trap drums, and trumpet and snare drums, for that kind of sound.

GL Actually, I have one other question, kind of a personal one. You told Christian Broecking in an interview about hearing Philippa Schuyler [1931–1967; American concert pianist, composer, and author, daughter of African-American author and journalist George Schuyler and white Texan artist and journalist Josephine Cogdell].

ACM Ooh, yes, when I was about 14 years old, in Dallas. I had great teachers in high school. You know, those bad, strong black teachers. Cedar Walton knew this teacher who had a bad choir when I was in ninth grade, and Cedar told me much later that she talked about me. Her name was Mrs. Bailey. I realize now that she was one of my greatest influences in directing choral music. But then I changed schools and Mrs. Turrell became my music teacher, and my piano teacher and the choir director, and she took me to see Philippa Schuyler. It was at the Baptist church. Somebody gave her some flowers, and she came out and set them right in front of the keyboard. But honey, she was out. It was beautiful. People called it “ay-vant-garde.” You know, she was doing some stuff.

GL She was writing her own music.

ACM Writing her own music, honey. I mean, she tore that up. She was one of my first influences, before Coltrane and everybody. I was fascinated with her. After the performance we went down to the dressing room, and there were all these black churchwomen. We’re down in the basement, and she’s sitting in a chair with all of her music in her lap. No smile, but she wasn’t mean. People were scared to approach her. I said how much I enjoyed it, and she smiled. She said, thank you, and went right back to that serious look. Then I read in Jetmagazine that she was killed in a plane crash, about 35 years old. That woman was bad. Her mother and father, five years before she was born, went on a vegetarian diet because they wanted to have a genius child. It said that in Jet too.

GL There’s a biography of her called Composition in Black and White.

ACM Oh, I’ll have to get that.

GL The reason I asked you about that is that I heard her play too.

ACM You did? Where?

GL In Chicago. I was only five or six. But I remember that regal look, and all the black churchwomen, including my mother.

ACM You remember the black churchwomen too?

GL Oh yeah, because it was at a church.

ACM Yeah, that’s where they had, you see, the black classical musicians. They did concerts in the church. You don’t see that now.

GL Well, you don’t see a lot of mention of black classical music at all.

ACM That’s what I’m talking about.

GL You had the classical music training as well as the gospel training, but even a lot of the black cultural writers and celebrities don’t pay that much attention to the black classical composers and performers, people like Hale Smith, Olly Wilson, Alvin Singleton, William Brown—

ACM They sure don’t, and the ones on TV that could promote it don’t. Take people like Oprah Winfrey, she’s into the Princes and the Patti LaBelles, Halle Berry, which is all good, but that’s just one part of it. You don’t hear anything about the classical musicians, the composers, the painters. Nothing. We’re not projecting the culture.

GL I did see that Lorna Simpson and Kara Walker made it to O Magazine, though. Actually, this reminds me of something that Lester Bowie told me. For example, you went to all-black schools when you were growing up, isn’t that right? Where you learned about a lot of different kinds of music. In fact, a lot of the people in the AACM who went to college went to all-black colleges—Leroy Jenkins, John Stubblefield, Ann Ward. Famoudou Moye went to an all-black college for a while.

ACM Yes, but whenever I talk to people about how I want to do something with a choir, the first thing they say is, Oh yes, we have a nice little gospel choir. I say, Look, this music that I write, it’s not straight-ahead gospel. I want readers, but I also want people who are able to improvise. This is what the emphasis is on. Why not the university choir and the gospel choir? People have to be versatile.

GL What Lester was saying was that because so many influential musical ideas are derived from African diasporic sources, the black colleges should be like meccas for contemporary black art and music, the place where you would have to go to see the newest creative music, the newest things going on.

ACM My college professor was head of the music department, and he taught Stockhausen and Copland. He had a blues band, and he might have mentioned Charlie Parker, but as far as teaching the black music, no. The choir director did choral music of a few black composers, but it was mainly the standard repertoire.

GL We’re trying to create some people who can move in multiple directions. That’s what we need as composers, people who can switch between the different cultures, sounds, and practices. I mean, you lived with a man from Senegal, and this was just one part of an intercultural experience. The music is like that too.

ACM Yes, I’m just looking ahead to do bigger projects, to bring all of that together.