ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/05/miles-davis 1926-1991-legendary-iconic_23.html

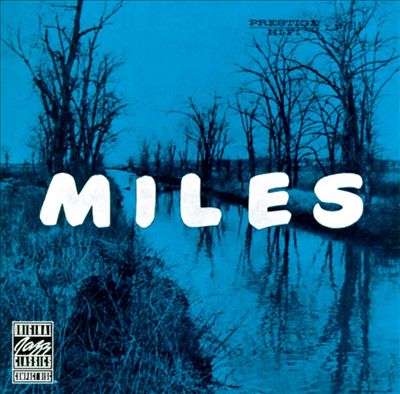

PHOTO: MILES DAVIS (1926-1991)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/miles-davis-mn0000423829

Miles Davis

(1926-1991)

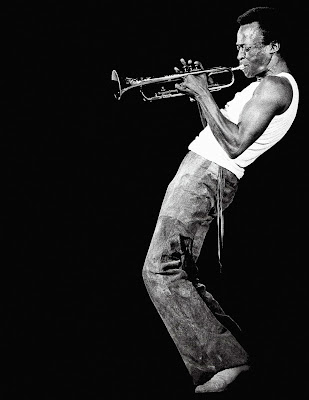

Biography by William Ruhlmann

A monumental innovator, icon, and maverick, trumpeter Miles Davis helped define the course of jazz as well as popular culture in the 20th century, bridging the gap between bebop, modal music, funk, and fusion. Throughout most of his 50-year career, Davis played the trumpet in a lyrical, introspective style, often employing a stemless Harmon mute to make his sound more personal and intimate. It was a style that, along with his brooding stage persona, earned him the nickname "Prince of Darkness." However, Davis proved to be a dazzlingly protean artist, moving into fiery modal jazz in the '60s and electrified funk and fusion in the '70s, drenching his trumpet in wah-wah pedal effects along the way. More than any other figure in jazz, Davis helped establish the direction of the genre with a steady stream of boundary-pushing recordings, among them 1957's chamber jazz album Birth of the Cool (which collected recordings from 1949-1950), 1959's modal masterpiece Kind of Blue, 1960's orchestral album Sketches of Spain, and 1970's landmark fusion recording Bitches Brew. Davis' own playing was obviously at the forefront of those changes, but he also distinguished himself as a bandleader, regularly surrounding himself with sidemen and collaborators who likewise moved in new directions, including the luminaries John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, and many more. While he remains one of the most referenced figures in jazz, a major touchstone for generations of trumpeters (including Wynton Marsalis, Chris Botti, and Nicholas Payton), his music reaches far beyond the jazz tradition, and can be heard in the genre-bending approach of performers across the musical spectrum, ranging from funk and pop to rock, electronica, hip-hop, and more.

Born in 1926, Davis was the son of dental surgeon, Dr. Miles Dewey Davis, Jr., and a music teacher, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, and grew up in the Black middle class of East St. Louis after the family moved there shortly after his birth. He became interested in music during his childhood and by the age of 12 began taking trumpet lessons. While still in high school, he got jobs playing in local bars and at 16 was playing gigs out of town on weekends. At 17, he joined Eddie Randle's Blue Devils, a territory band based in St. Louis. He enjoyed a personal apotheosis in 1944, just after graduating from high school, when he saw and was allowed to sit in with Billy Eckstine's big band, which was playing in St. Louis. The band featured trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Charlie Parker, the architects of the emerging bebop style of jazz, which was characterized by fast, inventive soloing and dynamic rhythm variations.

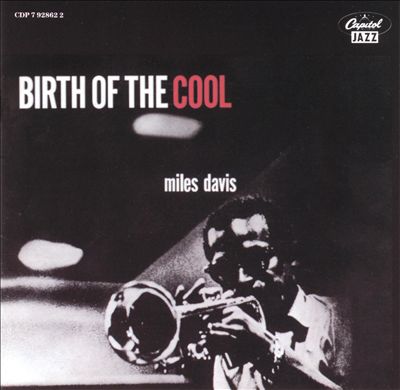

It is striking that Davis fell so completely under Gillespie and Parker's spell, since his own slower and less flashy style never really compared to theirs. But bebop was the new sound of the day, and the young trumpeter was bound to follow it. He did so by leaving the Midwest to attend the Institute of Musical Art in New York City (renamed Juilliard) in September 1944. Shortly after his arrival in Manhattan, he was playing in clubs with Parker, and by 1945 he had abandoned his academic studies for a full-time career as a jazz musician, initially joining Benny Carter's band and making his first recordings as a sideman. He played with Eckstine in 1946-1947 and was a member of Parker's group in 1947-1948, making his recording debut as a leader on a 1947 session that featured Parker, pianist John Lewis, bassist Nelson Boyd, and drummer Max Roach. This was an isolated date, however, and Davis spent most of his time playing and recording behind Parker. But in the summer of 1948, he organized a nine-piece band with an unusual horn section. In addition to himself, it featured an alto saxophone, a baritone saxophone, a trombone, a French horn, and a tuba. This nonet, employing arrangements by Gil Evans and others, played for two weeks at the Royal Roost in New York in September. Earning a contract with Capitol Records, the band went into the studio in January 1949 for the first of three sessions and produced 12 tracks that attracted little attention at first. The band's relaxed sound, however, affected the musicians who played it, among them Kai Winding, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, J.J. Johnson, and Kenny Clarke, and it had a profound influence on the development of the cool jazz style on the West Coast. (In February 1957, Capitol finally issued the tracks together on an LP called Birth of the Cool.)

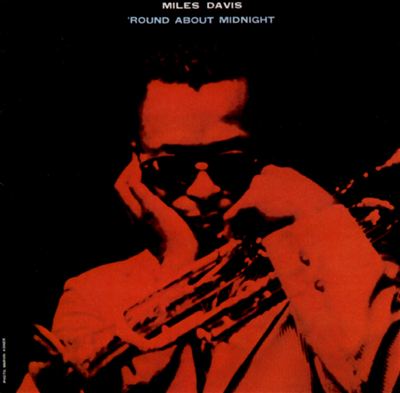

Davis, meanwhile, had moved on to co-leading a band with pianist Tadd Dameron in 1949, and the group took him out of the country for an appearance at the Paris Jazz Festival in May. But the trumpeter's progress was impeded by an addiction to heroin that plagued him in the early '50s. His performances and recordings became more haphazard, but in January 1951 he began a long series of recordings for the Prestige label that became his main recording outlet for the next several years. He managed to kick his habit by the middle of the decade, and he made a strong impression playing "'Round Midnight" at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1955, a performance that led major-label Columbia to sign him. The prestigious contract allowed him to put together a permanent band, and he organized a quintet featuring saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones, who began recording his Columbia debut, 'Round About Midnight, in October.

As it happened, however, he had a remaining five albums on his Prestige contract, and over the next year he was forced to alternate his Columbia sessions with sessions for Prestige to fulfill this previous commitment. The latter resulted in the Prestige albums The New Miles Davis Quintet, Cookin', Workin', Relaxin', and Steamin', making Davis' first quintet one of his better-documented outfits. In May 1957, just three months after Capitol released the Birth of the Cool LP, Davis again teamed with arranger Gil Evans for his second Columbia LP, Miles Ahead. Playing flügelhorn, Davis fronted a big band on music that extended the Birth of the Cool concept and even had classical overtones. Released in 1958, the album was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, intended to honor recordings made before the Grammy Awards were instituted in 1959.

In December 1957, Davis returned to Paris, where he improvised the background music for the film L'Ascenseur pour l'Echafaud. Jazz Track, an album containing this music, earned him a 1960 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance, Solo or Small Group. He added saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to his group, creating the Miles Davis Sextet, which recorded Milestones in April 1958. Shortly after this recording, Red Garland was replaced on piano by Bill Evans and Jimmy Cobb took over for Philly Joe Jones on drums. In July, Davis again collaborated with Gil Evans and an orchestra on an album of music from Porgy and Bess. Back in the sextet, Davis began to experiment with modal playing, basing his improvisations on scales rather than chord changes.

This led to his next band recording, Kind of Blue, in March and April 1959, an album that became a landmark in modern jazz and the most popular album of Davis' career, eventually selling over two million copies, a phenomenal success for a jazz record. In sessions held in November 1959 and March 1960, Davis again followed his pattern of alternating band releases and collaborations with Gil Evans, recording Sketches of Spain, containing traditional Spanish music and original compositions in that style. The album earned Davis and Evans Grammy nominations in 1960 for Best Jazz Performance, Large Group, and Best Jazz Composition, More Than 5 Minutes; they won in the latter category.

By the time Davis returned to the studio to make his next band album in March 1961, Adderley had departed, Wynton Kelly had replaced Bill Evans at the piano, and John Coltrane had left to begin his successful solo career, being replaced by saxophonist Hank Mobley (following the brief tenure of Sonny Stitt). Nevertheless, Coltrane guested on a couple of tracks of the album, called Someday My Prince Will Come. The record made the pop charts in March 1962, but it was preceded into the best-seller lists by the Davis quintet's next recording, the two-LP set Miles Davis in Person (Friday & Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, San Francisco), recorded in April. The following month, Davis recorded another live show, as he and his band were joined by an orchestra led by Gil Evans at Carnegie Hall in May. The resulting Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall was his third LP to reach the pop charts, and it earned Davis and Evans a 1962 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Large Group, Instrumental. Davis and Evans teamed up again in 1962 for what became their final collaboration, Quiet Nights. The album was not issued until 1964, when it reached the charts and earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group or Soloist with Large Group.

In 1996, Columbia Records released a six-CD box set, Miles Davis & Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings, that won the Grammy for Best Historical Album. Quiet Nights was preceded into the marketplace by Davis' next band effort, Seven Steps to Heaven, recorded in the spring of 1963 with an entirely new lineup consisting of saxophonist George Coleman, pianist Victor Feldman, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Frank Butler. During the sessions, Feldman was replaced by Herbie Hancock and Butler by Tony Williams. The album found Davis making a transition to his next great group, of which Carter, Hancock, and Williams would be members. It was another pop chart entry that earned 1963 Grammy nominations for both Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Soloist or Small Group and Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group. The quintet followed with two live albums, Miles Davis in Europe, recorded in July 1963, which made the pop charts and earned a 1964 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group, and My Funny Valentine, recorded in February 1964 and released in 1965, when it reached the pop charts.

By September 1964, the final member of the classic Miles Davis Quintet of the '60s was in place with the addition of saxophonist Wayne Shorter to the team of Davis, Carter, Hancock, and Williams. While continuing to play standards in concert, this unit embarked on a series of albums of original compositions contributed by the bandmembers themselves, starting in January 1965 with E.S.P., followed by Miles Smiles (1967 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group [7 or Fewer]), Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky (1968 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group), and Filles de Kilimanjaro. By the time of Miles in the Sky, the group had begun to turn to electric instruments, presaging Davis' next stylistic turn. By the final sessions for Filles de Kilimanjaro in September 1968, Hancock had been replaced by Chick Corea and Carter by Dave Holland. But Hancock, along with pianist Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin, participated on Davis' next album, In a Silent Way (1969), which returned the trumpeter to the pop charts for the first time in four years and earned him another small-group jazz performance Grammy nomination. With his next album, Bitches Brew, Davis turned more overtly to a jazz-rock style. Though certainly not conventional rock music, Davis' electrified sound attracted a young, non-jazz audience while putting off traditional jazz fans.

Bitches Brew, released in March 1970, reached the pop Top 40 and became Davis' first album to be certified gold. It also earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Arrangement and won the Grammy for large-group jazz performance. He followed it with such similar efforts as Miles Davis at Fillmore East (1971 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Group), A Tribute to Jack Johnson, Live-Evil, On the Corner, and In Concert, all of which reached the pop charts. Meanwhile, Davis' former sidemen became his disciples in a series of fusion groups: Corea formed Return to Forever, Shorter and Zawinul led Weather Report, and McLaughlin and former Davis drummer Billy Cobham organized the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Starting in October 1972, when he broke his ankles in a car accident, Davis became less active in the early '70s, and in 1975 he gave up recording entirely due to illness, undergoing surgery for hip replacement later in the year. Five years passed before he returned to action by recording The Man with the Horn in 1980 and going back to touring in 1981.

By now, he was an elder statesman of jazz, and his innovations had been incorporated into the music, at least by those who supported his eclectic approach. He was also a celebrity whose appeal extended far beyond the basic jazz audience. He performed on the worldwide jazz festival circuit and recorded a series of albums that made the pop charts, including We Want Miles (1982 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist), Star People, Decoy, and You're Under Arrest. In 1986, after 30 years with Columbia, he switched to Warner Bros. and released Tutu, which won him his fourth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance.

Aura, an album he had recorded in 1984, was released by Columbia in 1989 and brought him his fifth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist (on a Jazz Recording). Davis surprised jazz fans when, on July 8, 1991, he joined an orchestra led by Quincy Jones at the Montreux Jazz Festival to perform some of the arrangements written for him in the late '50s by Gil Evans; he had never previously looked back at an aspect of his career. He died of pneumonia, respiratory failure, and a stroke within months. Doo-Bop, his last studio album, appeared in 1992. It was a collaboration with rapper Easy Mo Bee, and it won a Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Instrumental Performance, with the track "Fantasy" nominated for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo. Released in 1993, Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux won Davis his seventh Grammy for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Performance.

Miles Davis took an all-inclusive, constantly restless approach to jazz that won him accolades and earned him controversy during his lifetime. It was hard to recognize the bebop acolyte of Charlie Parker in the flamboyantly dressed leader who seemed to keep one foot on a wah-wah pedal and one hand on an electric keyboard in his later years. But he did much to popularize jazz, reversing the trend away from commercial appeal that bebop started. And whatever the fripperies and explorations, he retained an ability to play moving solos that endeared him to audiences and demonstrated his affinity with tradition. He is a reminder of the music's essential quality of boundless invention, using all available means. Twenty-four years after Davis' death, he was the subject of Miles Ahead, a biopic co-written and directed by Don Cheadle, who also portrayed him. Its soundtrack functioned as a career overview with additional music provided by pianist Robert Glasper and associates. Additionally, Glasper enlisted many of his collaborators to help record Everything's Beautiful, a separate release that incorporated Davis' master recordings and outtakes into new compositions. In 2020, the trumpeter was also the focus of director Stanley Nelson's documentary Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool, which showcased music from throughout Davis' career. Also included on the documentary's soundtrack was a newly produced track, "Hail to the Real Chief," constructed out of previously unreleased Davis recordings by the trumpeter's fusion-era bandmates drummer Lenny White and drummer (and nephew) Vince Wilburn, Jr.

Miles Davis

Throughout a professional career lasting 50 years, Miles Davis played the trumpet in a lyrical, introspective, and melodic style, often employing a stemless harmon mute to make his sound more personal and intimate. But if his approach to his instrument was constant, his approach to jazz was dazzlingly protean. To examine his career is to examine the history of jazz from the mid-'40s to the early '90s, since he was in the thick of almost every important innovation and stylistic development in the music during that period, and he often led the way in those changes, both with his own performances and recordings and by choosing sidemen and collaborators who forged the new directions. It can even be argued that jazz stopped evolving when Davis wasn't there to push it forward.

Davis was the son of a dental surgeon, Dr. Miles Dewey Davis, Jr., and a music teacher, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, and thus grew up in the black middle class of East St. Louis after the family moved there shortly after his birth. He became interested in music during his childhood and by the age of 12 had begun taking trumpet lessons. While still in high school, he started to get jobs playing in local bars and at 16 was playing gigs out of town on weekends. At 17, he joined Eddie Randle's Blue Devils, a territory band based in St. Louis. He enjoyed a personal apotheosis in 1944, just after graduating from high school, when he saw and was allowed to sit in with Billy Eckstine's big band, which was playing in St. Louis. The band featured trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Charlie Parker, the architects of the emerging bebop style of jazz, which was characterized by fast, inventive soloing and dynamic rhythm variations.

It is striking that Davis fell so completely under Gillespie and Parker's spell, since his own slower and less flashy style never really compared with theirs. But bebop was the new sound of the day, and the young trumpeter was bound to follow it. He did so by leaving the Midwest to attend the Institute of Musical Art in New York City (since renamed Juilliard) in September 1944. Shortly after his arrival in Manhattan, he was playing in clubs with Parker, and by 1945 he had abandoned his academic studies for a full-time career as a jazz musician, initially joining Benny Carter's band and making his first recordings as a sideman. He played with Eckstine in 1946-1947 and was a member of Parker's group in 1947-1948, making his recording debut as a leader on a 1947 session that featured Parker, pianist John Lewis, bassist Nelson Boyd, and drummer Max Roach. This was an isolated date, however, and Davis spent most of his time playing and recording behind Parker. But in the summer of 1948 he organized a nine-piece band with an unusual horn section. In addition to himself, it featured an alto saxophone, a baritone saxophone, a trombone, a French horn, and a tuba. This nonet, employing arrangements by Gil Evans and others, played for two weeks at the Royal Roost in New York in September. Earning a contract with Capitol Records, the band went into the studio in January 1949 for the first of three sessions which produced 12 tracks that attracted little attention at first. The band's relaxed sound, however, affected the musicians who played it, among them Kai Winding, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, J.J. Johnson, and Kenny Clarke, and it had a profound influence on the development of the cool jazz style on the West Coast. In February 1957, Capitol finally issued the tracks together on an LP called Birth of the Cool.

Davis, meanwhile, had moved on to co-leading a band with pianist Tadd Dameron in 1949, and the group took him out of the country for an appearance at the Paris Jazz Festival in May. But the trumpeter's progress was impeded by an addiction to heroin that plagued him in the early '50s. His performances and recordings became more haphazard, but in January 1951 he began a long series of recordings for the Prestige label that became his main recording outlet for the next several years. He managed to kick his habit by the middle of the decade, and he made a strong impression playing "'Round Midnight" at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1955, a performance that led major label Columbia Records to sign him. The prestigious contract allowed him to put together a permanent band, and he organized a quintet featuring saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones that began recording his Columbia debut, Round About Midnight, in October. As it happened, however, he had a remaining five albums on his Prestige contract, and over the next year he was forced to alternate his Columbia sessions with sessions for Prestige to fulfill this previous commitment. The latter resulted in the Prestige albums The New Miles Davis Quintet, Cookin', Workin', Relaxin', and Steamin', making Davis' first quintet one of his better documented outfits.

In May 1957, just three months after Capitol released the Birth of the Cool LP, Davis again teamed with arranger Gil Evans for his second Columbia LP, Miles Ahead. Playing flugelhorn, Davis fronted a big band on music that extended the Birth of the Cool concept and even had classical overtones. Released in 1958, the album was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, intended to honor recordings made before the Grammy Awards were instituted in 1959. In December 1957, Davis returned to Paris, where he improvised the background music for the film L'Ascenseur pour l'Echafaud (Escalator to the Gallows). Jazz Track, an album containing this music, earned him a 1960 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance, Solo or Small Group. He added saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to his group, creating the Miles Davis Sextet, which recorded the album Milestones in April 1958. Shortly after this recording, Red Garland was replaced on piano by Bill Evans and Jimmy Cobb took over for Philly Joe Jones on drums. In July, Davis again collaborated with Gil Evans and an orchestra on an album of music from Porgy and Bess.

Back in the sextet, Davis began to experiment with modal playing, basing his improvisations on scales rather than chord changes. This led to his next band recording, Kind of Blue, in March and April 1959, an album that became a landmark in modern jazz and the most popular disc of Davis' career, eventually selling over two million copies, a phenomenal success for a jazz record. In sessions held in November 1959 and March 1960, Davis again followed his pattern of alternating band releases and collaborations with Gil Evans, recording Sketches of Spain, containing traditional Spanish music and original compositions in that style. The album earned Davis and Evans Grammy nominations in 1960 for Best Jazz Performance, Large Group, and Best Jazz Composition, More Than 5 minutes; they won in the latter category.

By the time Davis returned to the studio to make his next band album in March 1961, Adderley had departed, Wynton Kelly had replaced Bill Evans at the piano, and John Coltrane had left to begin his successful solo career, being replaced by saxophonist Hank Mobley (following the brief tenure of Sonny Stitt).

Nevertheless, Coltrane guested on a couple of tracks of the album, called Someday My Prince Will Come. The record made the pop charts in March 1962, but it was preceded into the bestseller lists by the Davis quintet's next recording, the two-LP set Miles Davis in Person (Friday & Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, San Francisco), recorded in April. The following month, Davis recorded another live show, as he and his band were joined by an orchestra led by Gil Evans at Carnegie Hall in May. The resulting Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall was his third LP to reach the pop charts, and it earned Davis and Evans a 1962 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Large Group, Instrumental.

Davis and Evans teamed up again in 1962 for what became their final collaboration, Quiet Nights. The album was not issued until 1964, when it reached the charts and earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group or Soloist with Large Group. In 1996, Columbia Records released a six-CD box set, Miles Davis & Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings, that won the Grammy for Best Historical Album. Quiet Nights was preceded into the marketplace by Davis' next band effort, Seven Steps to Heaven, recorded in the spring of 1963 with an entirely new lineup consisting of saxophonist George Coleman, pianist Victor Feldman, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Frank Butler. During the sessions, Feldman was replaced by Herbie Hancock and Butler by Tony Williams. The album found Davis making a transition to his next great group, of which Carter, Hancock, and Williams would be members. It was another pop chart entry that earned 1963 Grammy nominations for both Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Soloist or Small Group and Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group. The quintet followed with two live albums, Miles Davis in Europe, recorded in July 1963, which made the pop charts and earned a 1964 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group, and My Funny Valentine, recorded in February 1964 and released in 1965, when it reached the pop charts.

By September 1964, the final member of the classic Miles Davis Quintet of the 1960s was in place with the addition of saxophonist Wayne Shorter to the team of Davis, Carter, Hancock, and Williams. While continuing to play standards in concert, this unit embarked on a series of albums of original compositions contributed by the band members, starting in January 1965 with E.S.P., followed by Miles Smiles (1967 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group [7 or Fewer]), Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky (1968 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group), and Filles de Kilimanjaro. By the time of Miles in the Sky, the group had begun to turn to electric instruments, presaging Davis' next stylistic turn. By the final sessions for Filles de Kilimanjaro in September 1968, Hancock had been replaced by Chick Corea and Carter by Dave Holland. But Hancock, along with pianist Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin, participated on Davis' next album, In a Silent Way (1969), which returned the trumpeter to the pop charts for the first time in four years and earned him another small-group jazz performance Grammy nomination.

With his next album, Bitches Brew, Davis turned more overtly to a jazz-rock style. Though certainly not conventional rock music, Davis' electrified sound attracted a young, non-jazz audience while putting off traditional jazz fans. Bitches Brew, released in March 1970, reached the pop Top 40 and became Davis' first album to be certified gold. It also earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Arrangement and won the Grammy for large- group jazz performance. He followed it with such similar efforts as Miles Davis at Fillmore East (1971 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Group), A Tribute to Jack Johnson, Live-Evil, On the Corner, and In Concert, all of which reached the pop charts. Meanwhile, Davis' former sidemen became his disciples in a series of fusion groups: Corea formed Return to Forever, Shorter and Zawinul led Weather Report, and McLaughlin and former Davis drummer Billy Cobham organized the Mahavishu Orchestra.

Starting in October 1972, when he broke his ankles in a car accident, Davis became less active in the early 1970s, and in 1975 he gave up recording entirely due to illness, undergoing surgery for hip replacement later in the year. Five years passed before he returned to action by recording The Man With the Horn in 1980 and going back to touring in 1981. By now, he was an elder statesman of jazz, and his innovations had been incorporated into the music, at least by those who supported his eclectic approach. He was also a celebrity whose appeal extended far beyond the basic jazz audience. He performed on the worldwide jazz festival circuit and recorded a series of albums that made the pop charts, including We Want Miles (1982 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist), Star People, Decoy, and You're Under Arrest. In 1986, after 30 years with Columbia, he switched to Warner Bros. Records and released Tutu, which won him his fourth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance. Aura, an album he had recorded in 1984, was released by Columbia in 1989 and brought him his fifth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist (on a Jazz Recording).

Davis surprised jazz fans when, on July 8, 1991, he joined an orchestra led by Quincy Jones at the Montreux Jazz Festival to perform some of the arrangements written for him in the late 1950s by Gil Evans; he had never previously looked back at an aspect of his career. He died of pneumonia, respiratory failure, and a stroke within months. Doo-Bop, his last studio album, appeared in 1992. It was a collaboration with rapper Easy Mo Bee, and it won a Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Instrumental Performance, with the track "Fantasy" nominated for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo. Released in 1993, Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux won Davis his seventh Grammy for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Performance.

Miles Davis took an all-inclusive, constantly restless approach to jazz that had begun to fall out of favor by the time of his death, even as it earned him controversy during his lifetime. It was hard to recognize the bebop acolyte of Charlie Parker in the flamboyantly dressed leader with the hair extensions who seemed to keep one foot on a wah-wah pedal and one hand on an electric keyboard in his later years. But he did much to popularize jazz, reversing the trend away from commercial appeal that bebop began. And whatever the fripperies and explorations, he retained an ability to play moving solos that endeared him to audiences and demonstrated his affinity with tradition. At a time when jazz is inclining toward academia and repertory orchestras rather than moving forward, he is a reminder of the music's essential quality of boundless invention, using all available means.

Awards

- 1955, Winner; Down Beat Reader's Poll

- 1957, Winner; Down Beat Reader's Poll

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Composition Of More Than Five Minutes Duration for Sketches of Spain (1960)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Performance, Large Group Or Soloist With Large Group for Bitches Brew (1970)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist for We Want Miles (1982)

- Sonning Award for Lifetime Achievement In Music (1984; Copenhagen, Denmark)

- Doctor of Music, honoris causa (1986; New England Conservatory)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist for Tutu (1986)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist for Aura (1989)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Big Band for Aura (1989)

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1990)

- Knighted into the Legion of Honor (July 16, 1991; Paris)

- Grammy Award for Best R&B Instrumental Performance for Doo-Bop (1992)

- Grammy Award for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Performance for Miles And Quincy Live At Montreux (1993)

- Hollywood Walk Of Fame Star (February 19, 1998)

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction (March 13, 2006)

- Hollywood's Rockwalk Induction (September 28, 2006)

- RIAA Triple Platinum for Kind of Blue

https://view.joomag.com/my-new-black-magazine-nyu-black-renaissance-noire-brn-fall-206-issue-release/0136805001445708478?page=4

Miles Davis: A New Revolution in Sound

by Kofi Natambu

Black Renaissance Noire

Volume 14, Number 2

Fall, 2014

—Miles Davis

Scheduled merely as a quick programming lead-in to stage changes between featured performances by the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ), the Count Basie and Duke Ellington Orchestras, Lester Young, and Brubeck, nothing special was planned in advance for this short set which, like most jam sessions, was completely improvised by the musicians performing onstage. Davis was then the least well known musician in the assembled group which was made up of Thelonious Monk, individuals from the MJQ, and other individual members of various groups playing in the festival. Wein just happened to be a big fan of Davis and added him because he was "a melodic bebopper" and a player who, in Wein's view, could reach a larger audience than most other musicians because of the haunting romantic lyricism and melodic richness of his style. Wein's insight turned out to be prophetic.

Despite the fact that most of the mainstream audience on hand had only a vague idea of who Davis was, he was a standout sensation in the jam session and his searing performance was one of the most talked about highlights of the festival. Appearing in an elegant white seersucker sport coat and a small black bow tie, thus already demonstrating the sleek, sharp sartorial style that quickly became his trademark (and led to his eventual appearance on the covers of many fashion magazines in the U.S, Europe, and Asia), Davis captivated the festival throng with haunting, dynamic solos and brilliant ensemble playing on both slow ballads and intensely up-tempo quicksilver tunes alike. Taking complete command of the setting with his understated elegance and relaxed yet naturally dramatic stage presence, the handsome and charismatic Davis breezed through two famous and musically daunting compositions by Thelonious Monk ("Hackensack" and "Round Midnight"), and then ended his part of the program by playing an impassioned bluesy solo on a well-known Charlie Parker composition entitled "Now is the Time" which Davis had originally recorded with Bird in 1945. That clinched it. He was a hit. Miles had returned from almost complete oblivion to becoming a much talked about and heralded star seemingly overnight (of course this personal and professional recognition had been over a decade in the making). After a long, arduous struggle as both an artist and individual that began in his hometown of East St. Louis, Illinois when he started to play trumpet at the age of 13 in 1939, Miles Davis had finally "arrived." For the first time since 1950 he was completely clean and off drugs. No longer addicted, Miles now played with a bravura, command, and creative clarity that he had been fervently searching for well before he had become addicted to heroin. It would be the beginning of many more incredible triumphs and struggles that would catapult the fiery young trumpet player to the very pinnacle of his profession and global fame and wealth over the next ten years.

On hand for that historic summer concert in Newport, RI. was George Avakian, a young music producer from the large corporate recording company called Columbia (now Sony). Miles had been after Avakian for over five years trying to get a recording contract with Columbia which was then the largest and most successful music company in the United States, but Avakian had been cautiously waiting for a sign that Davis had conquered his personal problems and was ready to commit fulltime to his music. Clearly Miles was now ready. Avakian's brother Aram whispered to George during the concert that he should sign Davis now, before he became a big hit and signed with a rival company instead. Miles, himself nonplussed about the critical acclaim he was finally receiving, wondered what the fuss was all about and maintained that he was simply playing like he always had been. While there was some truth to this assertion it was also clear that Miles's highly disciplined demeanor, new responsible attitude, and impeccable playing now indicated his intent on making a new commitment to living a life strictly devoted to his art.

Avakian and Columbia representatives met with Davis two days later on July 19, 1955 to sign him to a new contract with the understanding that Davis would first fulfill the remainder of his contract with the Prestige label by doing a series of recordings in the fall of 1955 and the spring and fall of 1956 while at the same time making his first recordings with Columbia that would not be released until after the public appearance of the Prestige sessions. These small label recordings for Prestige would immediately become famously known as the "missing g" sessions (so-called for the dropping of the letter 'g' in the titles of these records, (e.g. Walkin', Workin', Cookin', Steamin', and Relaxin'). As Miles's first great legendary Quintet this young aggregation (the oldest member of the group was 33 years old) featured then relative unknowns John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. From the very beginning this group and Miles himself would remake Jazz history and become innovative and protean harbingers of great changes to come in the music as well as the general culture.

As with many great musicians, Miles's unique, highly individual sound on his chosen instrument--the trumpet--would be the creative basis and structural foundation of this new cultural and aesthetic intervention. His was a sound that embraced the entire history of Jazz trumpet in its meticulous attention to the demanding technical and physical requirements of the instrument yet also sought a creative and expressive approach that openly allowed for more subtle emotional nuances to emerge from his playing than were common traditionally on trumpet. Miles brought a highly burnished lyricism that was both deeply introspective and fiercely driving all at once. A major characteristic of Davis's playing was a new and different way of phrasing in which a major emphasis and focus on the relationship of space to tempo and melody (and the intervals between notes) became the hallmark of his style. In the process Davis dramatically redefined and expanded the expressive and creative range of the tonal palette and instrumental timbre of the trumpet. By shifting the traditional emphasis from the heraldic and bravura functions of the instrument to a more diverse and expansive range of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic ideas Miles was able to openly express the anguished conflict, sardonic irony, restless desire for cultural and social change, and questing existential/ psychological anxiety of the modern age. This intense attention to the broader expressive possibilities of both musical improvisation and composition also turned the feverish search for new forms and methods that characterized the era into a parallel personal quest for discovering a wider range of emotional and psychological contexts in which to play. The sonic exploration of the complexities and ambiguities of joy, rage, love, and melancholia was a major hallmark of Miles's style. Central to Miles's vision and sensibility was an equally exhilarating appreciation for the balanced expressive and intellectual relationship between relaxation and tension in his music. By focusing specifically on the spatial and rhythmic dimensions of melodic invention Miles developed musical methods that called for, and often resulted in, a precise minimalist approach to playing in which each note (or corresponding chord) carried an implied reference to every other note or chord in a particular sequence of musical phrases. Through a technical command of breath control and timbral dynamics induced by his embouchure and unorthodox valve fingerings, Miles could maintain or manipulate tonal pitch at the softest or loudest volumes. By creating stark dialectical contrasts in his sound through alternately attacking, slurring, syncopating or manipulating long tones in particular ensemble or orchestral settings (a technical device Miles often referred to as "contrary motion") Miles was able to convey great feeling and emotion through an economy of phrasing and musical rests. This rapt attention to allowing space or the silence between note intervals to dramatically assert itself as much or more as the notes themselves created great anticipation in his audience as to how these tensions would be resolved (or not). In this respect, the insightful observation by the French Jazz critic and music historian André Hodeir that Miles's sound tends toward a discovery of ecstasy is a rather apt description of Davis's expressive approach. What emerged from Miles's intensely comprehensive investigation of the creative possibilities of the instrument was a deep and lifelong appreciation for the tonal, sonic, and textural dimensions of playing and composing music. These aesthetic concerns as well as Miles's innovative creative solutions to the rigorous challenges of improvisational and composed ensemble structures alike in the modern Jazz tradition soon revolutionized all of American music and made Davis one of the leading and most influential musician-composers in the world during the last half of the 20th century.

Davis's widespread social, cultural, and political influence didn't end there however--especially in the black community. Miles also quickly became a social and cultural avatar whose highly personal combination of cool reserve, fiery defiance, detached alienation, intellectual independence, and striking stylistic innovation in everything from clothes to speech embodied, and largely defined for many, the ethos of 'hip' that pervaded the black Jazz world of the 1950s and early 1960s. But Miles, while remaining very hip, at the same time also lived and worked far beyond the insular world of hipsterism and avant-garde bohemia. He was unique in that his stance was simultaneously existentialist and engaged. As many observers, fans, scholars, friends, and critics have noted, Miles became, in many ways, what the critic Garry Giddins called "the representative black artist" of his era. John Szwed, Yale University music professor and author of a 2002 biography on Miles entitled So What: The Life of Miles Davis speaks for a couple of generations of writers, fans, artists and musicians when he states that by the late '50s, early 1960s:

“Miles was becoming the coin of the realm, cock of the walk, good copy for the tabloids, and inspiration for literary imagination. Allusions to him could turn up anywhere…Tributes to him sprang up in poems by Langston Hughes (“Trumpet Player: 52nd Street”), and Gregory Corso…Young people ostentatiously carried his albums to parties and sought out his clothing in the best men’s stores. In person, his every action was observed and read for meaning…A discourse developed around him, one that bore inordinate weight in matters of race—Miles stories—narratives about his inner drives, his demons, his pain, and his ambition. Invariably, his stories climaxed with a short comment, crushingly delivered in a husky imitation of the man’s voice, capped by some obscenity…He was the man.”Among many black people, Davis's outspoken, defiant social stance and hip, charismatic aura signified a profound shift in cultural values and attitudes in the national black community that also had a lasting political significance and influence. This was especially true for the emerging adolescent youth and radical young adults of the era whose overt displays of rebellion and defiance of racism and repression were becoming pervasive with the rise of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Miles quickly became a major symbol of this modern revolutionary spirit in African American culture and was seen by many as an important artistic leader in this struggle and its widespread social and political demands for respect, justice, equality, and freedom for African Americans that marked the period. Thus, it is not surprising that many of the various musical aesthetics that Davis devised and expressed during the late '50s and throughout the '60s consciously sought to advance specifically new ideas about the structural, formal, and expressive dimensions of the modernist tradition in contemporary Jazz music. These changes would openly challenge many of the orthodoxies of this tradition both in terms of form and content while at the same time asserting a radically different set of ideological and aesthetic values about the intellectual and cultural worth, use, and intent of the music that in attitude and style sought to resist or go beyond standard notions of both high art and commercial popular culture. Simultaneously however, Davis sought to consciously establish an even more socially intimate relationship with his black audience (and especially its youthful members) that would embody and hopefully expand Davis's views on the broad necessity for deeply rooted political and cultural change within the African American community and the U.S. as a whole.

In the quest to critique many of the philosophical assumptions governing conventional modernist discourse in art while still retaining a fundamental aesthetic connection to other important aspects and principles of modernism--especially those having to do with the continuous necessity of creative change and revision--Davis epitomized the 'progressive' African American Jazz musician's desire to use black vernacular sources, ideas, and values to engage these modernist traditions and principles on his/her own independent social, cultural, and intellectual terms. In such major recordings from the 1957-1967 period as his orchestral masterpieces Miles Ahead, (1957) Porgy & Bess, (1959) and Sketches of Spain (1960)--made in collaboration with his longtime friend and colleague, the white composer and arranger Gil Evans --and his equally significant and highly influential small group Quintet and Sextet recordings, Milestones, (1958) Kind of Blue, (1959) Live at the Blackhawk, (1961) My Funny Valentine, (1965) Four & More, (1964) E.S.P., (1965) Miles Smiles, (1966) Miles in Berlin, (1964) Miles in Tokyo, (1964) Live at the Plugged Nickel, (1965) and Nefertiti, (1967) Davis was at the forefront of those African American artists of the period who, in all the arts, were feverishly looking for and often finding fresh, new modes of pursuing aesthetic innovation and social change. By dialectically synthesizing and extending ideas, strategies, methods, and structures culled from such disparate sources as 20th century classical music, the blues, R&B, and many different stylistic forms from the Jazz tradition (i.e. Swing, Bebop, 'Cool' and 'Hard Bop' etc.)--many of which Davis himself had played a pivotal role in developing and popularizing--Miles helped bring about a new creative synthesis of modern and vernacular expressions that greatly changed our perceptions of what American music was and could be.

FOR MILES DAVIS

(Poem from: THE MELODY NEVER STOPS

by Kofi Natambu. Past Tents Press, 1991}

A Review of Miles Davis and American Culture

The New Journal

October, 2002

The essays by William Howland Kenney, Eugene Redmond and Benjamin Cawthra situate Davis's music within the cultural and economic history of East St. Louis, Missouri. Specifically, Kenney and Cawthra attempt to account for why Miles Davis is known as someone only "from" East St. Louis, why Davis both chose and had to leave for New York in 1944. Kenney's essay, "Just Before Miles: Jazz in St. Louis, 1926-1944," discusses Davis's formative years as a musician in "hot-dance" riverboat bands in Missouri and Illinois. Kenney argues that the demise of these riverboat bands--due to the advent of air conditioning, interstate highways, federal regulations, and the aging boats themselves--was as crucial a factor in Davis's decision to leave the Midwest as his desire to play with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker in New York. Cawthra's contribution, "Remembering Miles in St. Louis: A Conclusion," argues that the erosion of East St. Louis's economic and cultural infrastructures, due to deep-seated racism and political expediency, was and is as great a factor in the city's inability to retain its cultural talent as is the obvious attractions of the East and West coasts. More optimistic is Eugene Redmond's celebratory poem/prose, "'So What'(?)...It's 'All Blues' Anyway: An Anecdotal/Jazzological Tour of Milesville." Unlike Kenney and Cawthra, Redmond reads Davis's "from East St. Louis" as, at worst, mere description, at best, something to be proud of since, Redmond suggests, Davis's legacy might serve as a cornerstone of the foundation on which East St. Louis rebuilds itself.

The book also features interviews with record industry a & r impresario George Avakian and musicians Quincy Jones, Ron Carter, Ahmad Jamal, and Joey DeFrancesco. It concludes with a reprint of Davis's 1962 Playboy interview with Alex Haley. Other contributors include Quincy Troupe, Farah Jasmine Griffin, John Gennari, Ingrid Monson and Waldo Martin, Jr.

As noted above, the essays by Gerald Early, Eric Porter and Martha Bayles attempt comprehensive overviews of the twists and turns of Davis's career: from a "Newer Negro" (Early) playing black music (hard bop) and a black man playing Negro music (cool) to, after 1969, a black man playing black-and-white music (fusion and pop) and, finally, a black man playing African-American music (hip-hop). The intersection between ethnicity, race and gender in the preceding reflects concerns that orient almost all the writings here.

Gerald Early's introductory essay, "The Art of the Muscle: Miles Davis as American Knight and American Knave," begins from the premise that the key to understanding Miles Davis as a man and musician lies in the relationship between his ascendancy as a major force in jazz at the very moment that the music's commercial appeal was in decline. About the latter, Early writes: "No music can eschew its own commercial dimension, and if it does, as jazz sometimes has...it only winds up, paradoxically, trying to sell itself on the basis that it is noncommercial...." (4) Early argues that Davis attempted to solve this dilemma by embracing elitism while repositioning himself within the marketplace.

The decline of jazz as a popular music due, in part, to its own pretensions is an issue taken up later by Martha Bayles, but the theme is a familiar one in the arguments of Stanley Crouch, Wynton Marsalis, Ralph Ellison, Albert Murray and others. The common target is bebop, held responsible, to varying degrees, for jazz's demise as a popular music. The target behind the target is the modernist conception of "art" and the "artist," perceived as intrinsically antipopulist, self-indulgent and formalistic to the point of narcissism. In all its forms this argument leads to problematic, if not contradictory, positions, as we will see in Bayles's essay.

Gerald Early, for one, understands the pitfalls of the antiart argument and the rest of his essay dances around its implications. He acknowledges that any contradictions one might perceive in Davis wanting to have it "both ways" depend on prior presumptions about the inviolability of musical genres - which the musician may not share: "In a sense, what Davis wanted to do was transcend jazz and simply embody musical improvisation." (5) However, this generous reading of Davis's motivations will not, as Early knows, sustain scrutiny. Early is merely setting the ground for his own reading of Davis as the quintessential ever-searching, ever-restless romantic figure of jazz. This is Miles Davis through a European lens (to adopt one of Bayles's more useful strategies of reading jazz history). This is Miles Davis as a white man, which might explain why Early writes, with a straight face: "Miles Davis is the American bad boy of jazz, our Huckleberry Finn...."

Early does not neglect the "black" Miles Davis, the would-be homeboy, "Jim." Most illuminating in this regard is his discussion of Davis's fascination with boxing in general and his hero-worship of Sugar Ray Robinson in particular. Davis saw in Robinson's - and, earlier, Jack Johnson's - celebration of the "sporting life" (the indulgence in women, gambling, drugs, etc.) - a model and challenge to the "straight" life, not from the point of view of "hipness" but on the assumption (right or wrong) that black bourgeois culture was largely a form of accommodation to white racism. In particular, as Early makes clear, Davis viewed some - but not all - middle-class mores as attempts to police the "black body," strategies in concert with white modes of control. As a black male secularist and musician dedicated to the pleasures of the body, Davis could no more stomach "Crow Jim" attitudes among Negroes than he could Jim Crow white law. And just as Jack Johnson had, by virtue of his exploits in and out of the ring, become a "New Negro" worthy of the accolades of the Harlem Renaissance literary elite, so too, later, Miles Davis would become a "Newer Negro." Early points out that Davis saw himself as a part of a "black male heroic tradition," but whereas Johnson and Robinson - six years older than Davis - operated as New Negroes in spite of white American hostility, Davis, simply because he was in the right place at the right time, benefitted from the "white Negro"/Newer Negro phenomenon. His on- and off-stage antics thrilled the young, hip, white jazz aficionados (among them, of course, the Beats) of the 1950s. In this context, as Early makes clear, Davis's resentment, however heartfelt, was, like Lionel Hampton's accommodationism, based on the same premise: the audience for jazz, traditional or avant-garde, was overwhelmingly white.

Just as Davis is, for Early, a figure of the romantic artist and opportunistic businessman, benefitting the historical period in which he lived - the rise of the music industry - he is likewise, for Martha Bayles, a latter-day Ulysses, a straight man in an epic tale of pretension and slapstick. Its theme: "the day the music died." Bayles's largely laudatory essay, "Miles Davis and the Double Audience," links the modernist divide between technique and accessibility in modern European music (e.g., serialism) and American music (bebop) to the growing belief in progress and science in the early 20th century. For Bayles, the result is "no audience" for European modernism (she cites Milton Babbitt's famous essay, "Who Cares If You Listen?") and "two audiences" for American modernism. Aside from exasperating class differences and polarizing blacks and whites, the elevation of technique, Bayles argues, has resulted in the debasement of "traditional" musical values (especially melody). Miles Davis is thus the exception that proves the rule, negotiating the Scylla and Charbydis of crass commercialism (accessibility) and artistic isolation (technique): "to the yang of hard bop Davis brought stillness, melodic beauty, and understatement; to the yin of cool he brought rich sonority, blues feeling, and an enriched rhythmic capacity that moved beyond swing to funk." (155). This is, of course, a gloss on Gary Giddins's more pithy observation - cited by two other authors in this book - that Davis was the "Midwestern parent" of both West Coast cool and East Coast bop. These two modes of jazz quickly became color-coded as white and black in the late Fifties and early Sixties. As Gerald Early implied with his Huckleberry Finn-Sugar Ray Robinson metaphors, Davis is, for Bayles, a figure of musical and racial reconciliation despite his occasional posturing.

Bayles's essay stands alone in this volume in its attempt to not only bracket but also criticize the extramusical forces that influenced Davis's music, particularly after 1969 when he helped popularize fusion. In relation to music criticism, these forces function as "contexts." Bayles begins by noting, pace Porter et al, Davis's interracial audiences and the resulting discomfiture for this son of a "race man." (149) But audience, too, is a "context," and Bayles will privilege this particular context - for whom is this music? - and oppose other "contextual" approaches for being, of all things, insufficiently contextual. Especially, it seems, the political context(s). Yet what surprises one is the insufficient attention Bayles pays to historical contexts, a failure which results in misreadings and distortions of the historical record. Bayles, thinking of Gary Tomlinson (cited by Eric Porter), asserts that notions of "dialogue," like that of "contestation," do not provide "genuine insight" into Davis's music and its significance. Those terms, of course, not only imply "contexts" but, more important, they presuppose separate black and white cultures and traditions. This is what Bayles must reject as "significant," much less "positive," influences on Davis's music. And though she concedes the limitations of a purely "formal analysis" of Davis's music, Bayles proceeds to place into abeyance all contextual factors except "audience." Of course, this makes perfect sense since to invoke formalism sans audience would mean a retreat into modernist isolation.

I do not have the space to discuss the ways Bayles distorts the relationship between modernism, science and "progress" (in this respect she misreads Babbitt's essay) vis-a-vis serialism and aleatory music (though her distinction between aleatory music and free jazz is illuminating). Instead I will conclude by focusing on what Bayles has to say about American jazz and pop. It is perhaps a little fussy to note that Davis's infamous turning of his back to the audience is read by Bayles as contempt (she tries to distinguish gradations of contempt in Davis's behavior) when he himself claimed that his stage movements were a rejection of the jazz musician as "entertainer." As already noted in Gerald Early's essay, Davis came onto the stage of history when a black musician could not only be tolerated for rejecting the mask that Louis Armstrong had to wear but could, in fact, be lionized for doing so. This rejection of the entertainer role preceded Davis (as Bayles notes), but she can only see it in extremes, in polarized terms as either contempt or "a clever marketing device." She quotes Davis gleefully reveling in his "bad boy" role without sufficiently attending to its significance as a "role."

More egregious is Bayles's reading of Davis's "electric turn." Effusing over the 1960s in terms of "crossover" audiences, Bayles writes, "The seemingly miraculous spectacle of the double audience blending into one attracted Davis." Not according to almost everyone else in this volume and elsewhere. It was not race that mattered to Davis in this context but age - he wanted to go after the youth market, and the youth market was rock 'n roll and r&b. Had these audiences already been 'blending into one" fusion would have already been popular. Moreover, the term "crossover" was and is equivalent to "integration," largely a one-way street in popular music and social history. Black music was and is more popular with white audiences than the reverse just as black people move into white neighborhoods more often than the reverse.

So what "genuine insight" does Bayles offer in lieu of "dialogue" and "contestation"? Contemplating Davis's turn to fusion, she writes: "With the popular audience Davis shared an appreciation for the primary capacities of music: the power of rhythm to move the body (dance) and the power of melody to move his emotions (song). Perhaps fusion should be judged by these standards." (161) I could not agree more, but that's not to say that these are more profound criteria than the "simplistic notions of 'dialogue' and 'contestation.'" On the contrary, Bayles has simply withdrawn Davis's music from one "context" (political and social forces) and inserted it in another context (audience reception) on the basis of traditional musical values (melody, rhythm). Which really means: certain kinds of melodic treatment, certain kinds of rhythmic measure.

As I hope my extended - if incomplete - analyses of Early's and Bayles's essays - and there are other good ones here - imply, Miles Davis and American Culture is a worthy addition to the collection of anyone still fascinated by the enigma that was - and is - Miles Davis.

All contents copyright The New Journal, 2002

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/for-the-artists-critical-writing-volume-2

For the Artists: Critical Writing, Volume 2

by GREG MASTERS

October 31, 2007

AllAboutJazz

“Miles' music of the 1970s is not just a rejection of beauty, but a beautiful embrace of the rejected.”

Miles Davis: The Complete On the Corner Sessions

Sony Legacy Music, October 2007

"There is no architecture and no build-up. Just a vivid, uninterrupted succession of colors, rhythms and moods." —Arnold Schoenberg, describing his Five Pieces for Orchestra in a letter to Richard Strauss, 1909

From: The Rest is Noise by Alex Ross (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007)

For the Artists, Vol. 2 -© 2014 Greg Masters

The music Miles Davis forged in the first half of the 1970s, his so-called "electric period," is not jazz. In a determined effort to keep his sound fresh, he took the audacious step of leaving behind all the frameworks of the art form which had made him a recognized and venerated figure throughout the world. In an effort to open himself up to new ideas and to expand his audience, his new sound maintains elements of the jazz style he'd evolved for the previous 30 years, while appropriating styles of music outside the jazz repertoire, namely the propulsive dance groove of 70s funk (particularly James Brown and Sly Stone), the raucous, rough-edged, electro-charged brashness of Jimi Hendrix, the metallic sparkle of India's Ravi Shankar, the European classical avant-garde methods of Karlheinz Stockhausen, as well as the traditions of jazz going back to Dixieland and ragtime. It's also indebted to the free playing of Albert Ayler and late John Coltrane with Pharoah Sanders.

And what does this add up to? All I know is that the music manages to expresses feelings I've yet to find in any other art form. Complex, raw, primal feelings splayed and made tangible.

The music Miles made in these years—particularly with the scorching electric guitars of Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas, grounded in the steady, incantory pulse of Al Foster's 4/4 rhythm on drums and Michael Henderson's unswerving definition of tempo and key via electric bass—defined an organic, body-centered response to nature. Bird calls and the sound of wind through the trees is as much a part of the pastiche as is the dance of the inner psyche. We've heard these sounds on walks through the woods.

But the music is—despite the assault of its unfamiliar gestures and its straying beyond bar measures—rooted in blues. The whole thing is still a child of the body and spirit-form called blues. Miles was clearly intending to move his music out of the elite confines of the music hall and into the street, or at least onto the radio.

Miles' generosity of spirit, his openness to influences from outside the expected, his need to dig deep into emotional recesses never before expressed so vividly, make it seem that the music is contemporary. To these ears it is not at all dated or relegated to a nostalgic dip into the past. It was so far ahead of its time that we're still catching up to it nearly 40 years later.

The Complete On the Corner Sessions (Sony-Legacy Music, 2007) is the eighth and final set in a series of Miles Davis boxes. This six-CD package includes six-plus hours of music, including 12 previously unissued tracks, plus five tracks previously unissued in full. The package contains a 120-page booklet with liner notes and essays by musician/co-producer Bob Belden (Michael Cuscuna is the other co-producer), journalist Tom Terrell and arranger/musician Paul Buckmaster.

The Complete On the Corner Sessions is an inaccurate and misleading title in an academic sense. The tracks he recorded at Columbia Studio B over the course of 16 sessions presented in this set from March 9, 1972 to May 5, 1975 offer up at least two very different artistic intentions. The first is the material realized for what would be released as On the Corner in July 1972 —the "extended grooves," as bassist Michael Henderson explains in the liner notes. This is a singular event in the Miles chronology, although it can be seen as an extension of the sound he had developed in 1970 in an ensemble that included Keith Jarrett, Jack DeJohnette, Michael Henderson, Gary Bartz, John McLaughlin and Airto Moreira (represented on The Cellar Door Sessions, released as a six-CD box set in 2005).

Other tracks collected here, particularly those assembled on Get Up With It (released November 1974), are another matter. Following the June 1972 sessions that resulted in On the Corner, Miles moved the ensemble sound away from an insistence on a churning, full-speed-ahead jam on one chord. On a handful of sessions over the next few years, orchestral colors are explored and there's room for chord changes and melodies. Perhaps it's quibbling, but I'm more comfortable with distinguishing each of the original LPs as distinct periods, or moments, in Miles' continuous evolution.

The new solo

In the early 1970s, Miles could not play trumpet with the intensity, force and bravado he'd exhibited throughout his career and which had been at a peak in 1969 and 1970 as he put himself on display to a whole new audience of rock crowds at the Fillmore East (March 6-7, 1970 and again June 17-20, 1970) and Fillmore West (April 10-11, 1970 and again Oct. 15-18, 1970), at huge rock festivals (Isle of Wight, Aug. 29, 1970) and other venues larger than the night clubs and corner bars he'd been playing for decades.

His embouchure was compromised. He was in ill health. His use of recreational drugs was reportedly abundant. Playing trumpet is physically demanding and Miles, in the 1970s, was willing, but his body was just not near the same levels as it had been. His soloing and his steering of the ensemble sound via his horn was diminished from what it had been.

But what he lacked in physical stamina, he made up for by taking huge risks in exposing his every vulnerability via a shift in musical intention. He refused to rely on playing crowd favorites or tunes from his past repertoire. He was intent on forging something entirely brand new, of presenting something which hadn't been seen or heard before.

The case could be made that he was insulting his devoted audience by merely presenting incomprehensible noise. But I am in the camp which believes this music is valuable in its revolutionary intentions.

The Complete On the Corner Sessions box showcases Miles' power as a leader. While the musicians are not playing charts, within their prescribed roles each player contributes an individual intensity and voice while fitting into the ensemble sound.

Miles' conducting of the group improvisation is firm enough to give a recognizable shape to the tune while trusting enough of the individual voices to bring out their best. Not many of the musicians who passed through Miles' various groups ever sounded better than when they were with him. Why? Because part of Miles' genius was in encouraging his partners to reach for expressions they hadn't known were within them. As leader, he afforded them the time to expand on their ideas, while at the same time maintaining a unifying order to contain the amalgam of personal contributions.

However, here the soloing is less rewarding to listen to because the musicians aren't as skilled as were the musicians in Miles' previous ensembles. And there's often less gradations to which the improvisations can respond. Often the solos are enlisted to override the churning, molten funk of the groove laid down by the rest of the pack. So, less skilled and less brave than Miles was when he complemented Charlie Parker's fusillade attack with a whole different approach, the soloing musicians on these sessions take less risks and resort to sounding off on their horns in a frenzy of notes in their attempt to meet the demands of the ensemble sound. There's little nuance, little chance to explore and test, as the musical concept is forceful and deliberate.

But this is less a liability because the act of soloing acquires a new purpose and intent on these tracks. Each solo is less ego-based than solos from the 60 years of improvisational music dating back to Louis Armstrong's emergence with King Oliver. Here, the solo is not the showcase for virtuosity it was before. While each player's skill is on display and each brings his own personal touch to the solo, it's more directed to serve the music. The solo is a momentary display within the textures of the process. It's a thread in the fabric.

Too, while Charlie Parker in the 78 rpm era only had three minutes to make his statement, Miles in the LP era can take his time and uses the space to elongate the music-listening experience so it can extend the range and incorporate moods and tones beyond bebop and standards boundaries.

The argument could be made that the level of musicianship in the ensembles Miles led throughout these electric years was not as skilled as it had previously been. These musicians lacked the virtuosic capabilities of the now recognized jazz masters who had played with Miles throughout the 40s, 50s and 60s, players who were capable of soloing at the proper time in their prescribed roles as sidemen—beautiful statements that adhered to the chord changes and showed off their technical facility and aesthetic craft in the service of making art music.

This was the basic structure: A small team of musicians would play a theme, then each would take a turn soloing, the theme would be stated again by the ensemble and the piece would end. The audience knew what to expect. The thrill was in how articulate the soloists could express themselves.

Miles, even at 19 years old when he joined the Charlie Parker band, added something different to the pyrotechnic virtuosity of players like Parker. Miles' sound brought a softer, feminine element, a brooding, reflective wistfulness that countered the alpha male assertiveness of most other jazz music of the time and of the preceding 50 years.

There are several reasons why Miles' music of the 70s may be less attractive to listeners. For one, it's nasty. It digs deep to express dark recesses of feelings and sustains those moods for long stretches. It is not enjoyable in the sense that art had served previously. As Theodor Adorno says, in discussing the music of Schoenberg, affability ceases. The music is less about serving as entertainment and is more an unrestrained attempt to express the rawest emotions. It's beyond entertainment. Miles was through pandering to audience expectations. Too, with his trumpet-playing limited because of poor health, he began using an electric organ to produce occasional howls, chords not heard before, eerie, dark blocks of sound.

Defiling the Cult of Beauty: The Influence of Stockhausen and Messiaen

The music deserves more serious examination and certainly more recognition and acclaim. It is remarkable music in that it integrates a universe of sounds. It's not simply bringing in the ethnic influence of a foreign culture, as Dizzy Gillespie did decades earlier by bringing Caribbean dance rhythms into his sound. The music adds textures and complexities learned from European avant-garde—particularly the collage effects of Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose pieces since the 1950s, besides traditional orchestral instrumentation, were making use of electronic effects (synthesizers, amplified soloists, ring modulators), as well as short wave receivers.

In the liner notes, Paul Buckmaster, a British cellist and composer who had experimented with tape loops, recounts how he exposed Miles to the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen at this time. The influence this had on Miles' sound is easy to imagine. Stockhausen's music is a radical break from the classical music tradition in that it does not rely on narrative. Like a Godard movie, it interrupts the spoon-fed story-telling structure to offer up a new palette of sensual and intellectual effects. It is full of surprises, as the listener can never anticipate what's coming next. It's a music free of sentiment, unencumbered from the Romantic strategy of appealing to common urges (assuming agreement is pleasing).

After an absorption in the compositions of Stockhausen, as well as those of Olivier Messiaen, with their open-ended structures, Miles' methods can be seen to jettison the traditional thematic structure left over from the Romantic era, where a piece of music follows a pattern, or narrative, describing a set of experiences or feelings through time. Miles begins here, like modern composers Messiaen and Stockhausen, to make use of the moment. The allegiance to a story is abandoned. Each moment of the musical piece is attuned to the extraordinary. Miles acquires a new tonal palette incorporating ominous and chilling explorations, such as examined in the music of Stockhausen and Messiaen.

Also, with the use of silences, the band's forward progression coming to a sudden halt, a strategy also likely picked up from Stockhausen, the music emphasizes the collage-like, fragmentary nature of perception, not an ideal make-believe illusion. The listener can enter and leave anywhere.

Too, not answerable to any agenda, the music's idiosyncratic path is decidedly not intended to placate audience expectation. Pure art seeks to explore and enunciate more than entertain.

These expressions take art away from the merely beautiful and the artifice of luxury. The illusion of safe extravagance is removed in order to portray less-than-polite feelings. Left behind is good taste, decorative entertainment for the comfort of paying patrons.

The music is so densely layered and there is so much musical activity that repeated listening is rewarded as moments and threads are heard differently each time. And, without the formal dependence on theme and dramatic progression, our listening experience is splayed out to concentrate on the moment, not the anticipation of a climax and resolution.

Much of the music contained in this package could be designated "new age," though it's often more raucous than what we typify today as the calming ambient music we use for relaxing or performing yoga.

While Miles' intentions with his music might have been to get people up to dance, at the same time he created a panache of listenable grooves filled with surprises and unprecedented ensemble sounds that still retain their freshness and audacious attitude.

Dissonance, Our Friend

Miles' music of the 1970s is not just a rejection of beauty, but a beautiful embrace of the rejected.

For Miles, dissonance was an acknowledgement that there was more to be expressed in music than comfort and resolvable sensations. The musical vocabulary of traditional Western harmony—the I, IV, V form, the basic foundation for everything from church hymns to blues, standards and rock 'n' roll —imposed limitations to exploring and expressing a range of emotions and a depiction of possibilities beyond the familiar tonal centers available in major and minor patterns.

His departure from these confines might be traced back as far as 1959's Kind of Blue, which broke from the blues-based form by using modal scales that gave an effect of suspension, as chords didn't resolve back to the root chord as in the familiar traditional manner. Pleasing an audience with tasteful, familiar songs, providing entertainment, became too tired. Miles wanted to grow as an artist.

Miles' group of the mid-60s took it even further. Pushed by Wayne Shorter's spiral compositions and fragmentary style of soloing on sax and by keyboardist Herbie Hancock's schooling in Debussy and Ravel and drummer Tony Williams' aggressive splattering of bar lines, this music too offered a sense of suspension as it uprooted the root and tonic.

The shift from the traditional standards repertory to a push into something new is discerned in The Complete Live at The Plugged Nickel set from Dec. 22-23, 1965 (released as an eight-CD box set in July 1995). Miles, the leader, seems in poor health. His trumpet playing lacks breath and his soloing comes in short bursts which he can't sustain. He, in fact, does not play a lot over the course of the seven live sets over two nights. His weakness gives more of the spotlight to his young, energetic sidemen, who are eager to advance into new realms beyond the standards repertoire to which their boss has been anchored.

Later in the decade, Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea would even be nudging the music into totally free territory—leaving behind the grounding in a common key and time signature—before Miles, not quite convinced of the emotional impact of a total abandonment of order, would rein the group back down to a place of agreement.

Fortunate to be working for a record company—Columbia (now Columbia/Legacy, a division of Sony BMG Music Entertainment)—that indulged his direction and allowed him to pursue his project, Miles ran with it. Not obliged to the record company to fester as a recognizable brand, Miles could use the studio and countless live dates, to continue developing and pushing into unexplored territory to create sounds which were unheard and unimagined previously.

The Tunes

There are some gems among the previously unreleased tracks, particularly "On the Corner (take 4)" and "Mr. Foster," and the release of unheard music from this phase of Miles' career will thrill devotees of his electric music.

"On the Corner (take 4)" offers up the entire universe in one chord. It's a five-minute studio fragment that propels the listener via one effect: a determined mining of a vamp pedaled to one chord onto which the musicians, particularly John McLaughlin, augment with furious yet mannered waves of variation. It could have fit onto side one of A Tribute to Jack Johnson (released Feb. 1971).

On "On the Corner (unedited master)," as well as the unedited master and issued take of "Helen Butte/Mr. Freedom X," some new variants are heard, dark colorful chords on organ, but pedestrian, Theremin-like keyboard noodling by Harold Ivory Williams (my guess, the other two keyboardists were Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock, or possibly it's Dave Creamer on guitar) is amateurish and grates after awhile. We hear for the first time instrumental solos by Keith Jarrett on electric piano, John McLaughlin on electric guitar and even Miles on wah-wah trumpet that were excised in the final mix, sacrificed for the ensemble concept.

The idea here is that individual efforts contribute to a whole. Ego is gone. What's important is the ensemble.