SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JEREMY PELT

(April 17-23)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

(April 24-30)

AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS

(May 1-7)

KARRIEM RIGGINS

(May 8-14)

ETTA JONES

(May 15-21)

YUSEF LATEEF

(May 22-28)

CHRISTIAN SANDS

(May 29—June 4)

E. J. STRICKLAND

(June 5-11)

TAJ MAHAL

(June 12-18)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

(June 12-18)

DOM FLEMONS

(June 19-25)

HEROES ARE GANG LEADERS

(June 26-July 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/william-grant-still-mn0000361592/biography

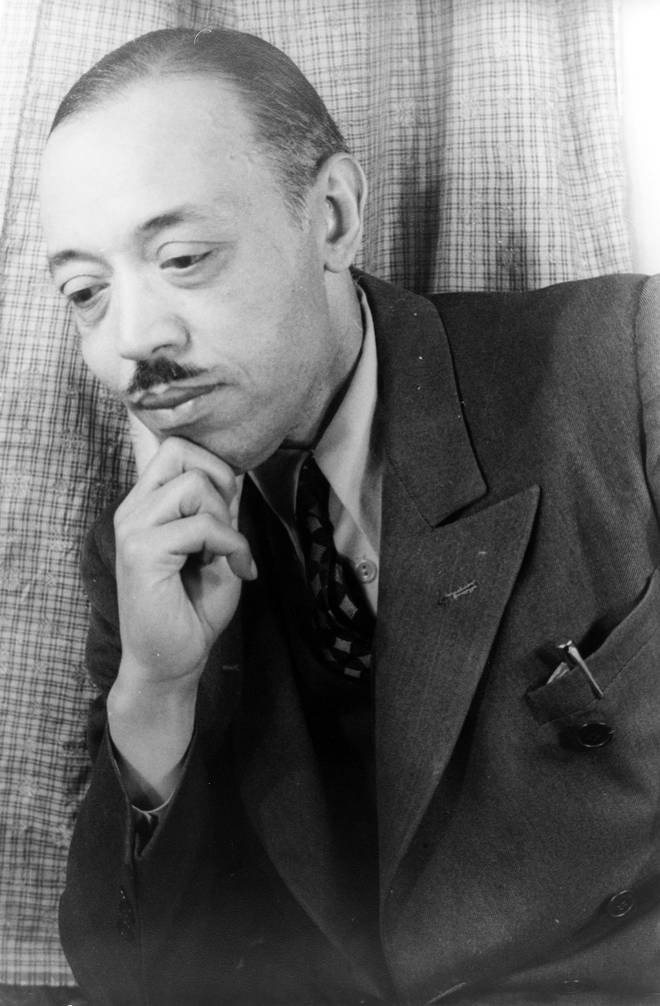

William Grant Still

(1895-1978)

Artist Biography by Chris Morrison

"With humble thanks to God, the Source of Inspiration." Such is the inscription to be found on the scores of the works of William Grant Still, sometimes called "The Dean of African-American Composers" and one of America's most versatile musicians.

Still was but three months old when his father, the town bandmaster, died. Shortly thereafter, his family moved to Little Rock, AK. Still has written movingly of the influence his mother and grandmother had in forming his character and instilling in him a love for the arts. In addition, his new stepfather was a big music fan, and encouraged his stepson's interest by taking him to operettas and buying him recordings. Still's education continued at Wilberforce University, which he entered at age sixteen, and at the Oberlin Conservatory, where he studied theory and composition. He also had studies with George W. Chadwick and Edgard Varèse, all the while supporting himself by playing in orchestras and bands.

After a stint in the U.S. Navy in 1918, Still did arrangements for W. C. Handy and Paul Whiteman, played oboe in the famous Noble Sissle-Eubie Blake revue Shuffle Along, and began a decades-long association with radio, arranging and producing programs for the Mutual and Columbia networks. His early compositions were fairly dissonant and complex (perhaps under Varèse's influence); he made a major breakthrough when he took Chadwick's advice and started incorporating elements of African American and popular musical styles into his works. His first big hit, and his best-known work to this day, is his first symphony, the "Afro-American," which was given its premiere in Rochester, NY, in 1931, and was soon performed all over the world.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1934, Still turned his attention to film, providing the scores for movies like Lost Horizon and the original Pennies from Heaven. Later he also scored a number of television shows, including Perry Mason and Gunsmoke. Guggenheim and Rosenwald Fellowships allowed him to produce large-scale works like the ballet Lenox Avenue (1937) and the operas Blue Steel (1935) and Troubled Island (1938). The last-named work -- with a libretto by Langston Hughes and based on the life of Dessalines, the first Emperor of Haiti and one of the major figures in Haiti's independence -- was premiered by the New York City Opera in 1949 and was very well received.

Still continued to write politically and racially conscious works throughout his life, such as the narrated work And They Lynched Him On A Tree (1940) and In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died For Democracy (1944). In the 1950s, he turned to writing children's works, such as The American Scene (1957), a set of five suites for young people based on geographic regions of the United States.

In 1981, Still's opera A Bayou Legend was the first by an African-American composer to be performed on national television. He was also the first African American to conduct a major U.S. orchestra (when he led the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a Hollywood Bowl concert of his own music), and the first African-American composer to have his works performed by major American orchestras and opera companies.

https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200186213

Biographies William Grant Still, 1895-1978

William Grant Still New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

Known as the "Dean of African-American Composers," William Grant Still was born in Woodville, Mississippi and raised in Little Rock, Arkansas, where his mother was a high school English teacher. He began to study the violin at age 14 and taught himself to play a number of other instruments, excelling at the cello and oboe. In 1911, Still entered Wilberforce University in Ohio where he gained valuable experience conducting the University band and producing his first attempts at composition and orchestration. Although his abilities as a performer and arranger led to many opportunities for him beyond the concert hall, he was inspired by the career of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor to become a composer of concert music and opera. He left Wilberforce University in 1915 and began to work as a freelance performer and arranger for many of the top bands in the Ohio region, eventually developing an association with W.C. Handy for whom Still made his first published arrangement. His work in the world of commercial music lasted throughout his career including film scoring (largely uncredited) while living in Los Angeles during the 1930s and work as an arranger for theatre orchestras and early radio, most notably with Paul Whiteman, Sophie Tucker, Willard Robison and Artie Shaw.

Still's education continued off and on throughout the 1920s with a brief stint at Oberlin College, where he studied theory and counterpoint. He studied composition with George Chadwick at New England Conservatory and privately with experimental composer Edgard Varèse, who became Still's most influential teacher. Varèse was also an advocate for Still, programming his compositions on concerts of the International Composers' Guild, an organization which he helped found in 1921.

William Grant Still's career was comprised of many "firsts". He was the first African-American composer to have a symphony performed by a professional orchestra in the U.S., the Symphony no. 1 "Afro-American" (1930). It was premiered by Howard Hanson and the Rochester Philharmonic. The piece's New York premiere was given by the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall in 1935. He also became the first African-American to conduct a major symphony orchestra in the United States when he led the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1936. In the world of opera, his Troubled Island was the first by an African-American to be performed by a major opera company (New York City Opera, 1949) and that same opera was the first by an African-American to be nationally televised.

Although William Grant Still did not write a large quantity of works for solo voice and piano, the quality is very high. Still set many of the great poets of the Harlem Renaissance including Paul Laurence Dunbar, Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. He also set poetry by his second wife, Verna Arvey, an accomplished writer and pianist who wrote the libretti for most of Still's operas. Perhaps his most ambitious work for voice and piano is the song cycle "Songs of Separation" which sets poetry by Dunbar, Hughes, Arna Bontemps and Haitian poet Philipps Thoby-Marcelin (in French). In the cycle, Still sets five poems of diverse authorship with a common literary theme and constructs a unified musical framework around the poems. As in his famous Symphony no. 1, Still utilizes the harmonic and rhythmic language of jazz and blues to portray the sense of "otherness" inherent in the poetry.

Further Reading

- Arvey, Verna. In One Lifetime. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1984.

- Spencer, J.M.. The William Grant Still Reader. A special issue of Black Sacred Music: A Journal of Theomusicology, 6 no. 2. (Fall 1992).

- Still, Judith Anne, Michael J. Dabrishus and Carolyn L. Quin. William Grant Still: A Bio-bibliography. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1996.

- http://www.williamgrantstillmusic.com/

https://americansymphony.org/concerts/online/william-grant-still/

Composer in Context: William Grant Still

Description

Ranked among the greatest American composers, William Grant Still was nicknamed the “Dean of African American Composers” for the many firsts he achieved during his substantial career. He was the first African American to have a symphony performed by a professional orchestra (Symphony No. 1 performed by the Rochester Philharmonic in 1931); conduct a major American orchestra in his own music (Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1936); and have an opera performed by a major opera company (Troubled Island performed by the New York City Opera in 1949) and nationally televised (Bayou Legend televised in 1981).

Though more well-known today as a symphonist, he embraced all of America’s music, composing and arranging a variety of works from film scores, art songs and popular music to symphonies, operas, concerti, and chamber music. Still flourished in his compositional career; during a time when Jazz was the epitome of Black artistic expression, he managed to forge a difficult path and claim his right of access to the world of classical music. Still utilized the expressive liberties claimed by White modernists while rejecting their elitism and conveyed the struggles of being a Black person in America through his music—an experience that was quite uncommon within the primarily White realm he was navigating.

Presently, while diversity in classical music has improved, the reality is still bleak especially for composers. A difficult hurdle to maneuver once a work is completed is getting a significant orchestra or ensemble to premiere it, granting the composer exposure and further access in an already exclusionary field. Additionally, many Black composers were historically confined to the Jazz or Blues genres—if not outright ignored—with the assumption that the Black experience and sound was monolithic. As a result, many Black composers—historically and contemporarily—have gone largely unnoticed and forgotten.

Listen today to hear our recordings of three landmarks from the great William Grant Still’s composing career that represent aspects of three of his self-described style periods…and if you can make it, join us on September 12 in Sewell, NJ to hear a chamber program curated by ASO’s Philip Payton to celebrate and explore the significant contributions Black composers have made to classical music, including mesmerizing works by contemporary composers Jessie Montgomery and Trevor Weston.

Text adapted from concert notes for Revisiting William Grant Still.

Don’t miss a single offering, sign up for our email list.

Details

Program

Africa

“An American Negro has formed a concept of the land of his ancestors

based largely on its folklore, and influenced by his contact with

American civilization. He beholds in his mind’s eye not the Africa of

reality but an Africa mirrored in fancy, and radiantly ideal.”

In attempting to represent matters African—a compelling topic for artists in the 1920s—Still confronted the aesthetic gulf between the exploitative primitivism so prevalent among the (white) modernists and the character with which he, as a man of the Harlem Renaissance, wanted to represent the ancestral and cultural African connections of Black Americans. Even though he struggled for over a decade while writing Africa, Still’s distinctive aesthetic and artistic integrity manifests itself as compellingly as the overarching idealism of its purpose.

Symphony No. 2 in G minor, Song of a New Race

An extension of his first Symphony, Afro-American Symphony,

Still’s Symphony No. 2 (1937) served to represent “the American colored

man of today,” a vision and hope for an integrated society. This theme

is manifested in the characteristically expansive nature of the piece

and is further highlighted through his use of the brass section to

express a call and response dialogue—which is common practice in African American churches and folk songs.

Darker America

Still’s Darker America (1924) was both his first extended piece

and indicator of his success as a concert music composer. Premiered in

1926, Still reflected on the depth of his intentions for the piece

noting that it “is representative of the American Negro, and suggests

triumph over sorrows through fervent prayer.” The opening theme of this

tone poem features “the American Negro” in the strings, a “sorrow theme”

in the English horn, a theme of “hope” in the muted brass, and a prayer

of “numbed rather than anguished souls” in the oboe. As the rest of the

piece unfolds, the listener can bear witness to the development of the

theme from sorrow to triumph.

Artists

Composed by William Grant Still

Conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Audio

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Grant_Still

William Grant Still

Portrait of Still by Carl Van Vechten | |

| Born | May 11, 1895 Woodville, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | December 3, 1978 (aged 83) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

William Grant Still Jr. (May 11, 1895 – December 3, 1978) was an American composer of nearly 200 works, including five symphonies, four ballets, eight operas, over thirty choral works, plus art songs, chamber music and works for solo instruments. Born in Mississippi, he grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas,[1] attended Wilberforce University and Oberlin Conservatory of Music,[2][3] and was a student of George Whitefield Chadwick and later Edgard Varèse.[4] Due to his close association and collaboration with prominent African-American literary and cultural figures, Still is considered to have been part of the Harlem Renaissance.

Often referred to as the "Dean of Afro-American Composers," Still was the first American composer to have an opera produced by the New York City Opera. Still is known primarily for his first symphony, Afro-American Symphony (1930), which was, until 1950, the most widely performed symphony composed by an American. Also of note, Still was the first African-American to conduct a major American symphony orchestra, the first to have a symphony (which was, in fact, the first one he composed) performed by a leading orchestra, the first to have an opera performed by a major opera company, and the first to have an opera performed on national television.

Life

William Grant Still, Jr. was born on May 11, 1895, in Woodville, Mississippi.[1]:15 He was the son of two teachers, Carrie Lena Fambro[5] (1872–1927) and William Grant Still Sr[1]:5 (1871–1895). His father was a partner in a grocery store and performed as a local bandleader.[1]:5 William Grant Still Sr. died when his infant son was three months old.[1]:5

Still's mother moved with him to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught high school English.[1]:6 She met and in 1904[5] married Charles B. Shepperson, who nurtured his stepson William's musical interests by taking him to operettas and buying Red Seal recordings of classical music, which the boy greatly enjoyed.[1]:6 The two attended a number of performances by musicians on tour.[citation needed][6] His maternal grandmother Anne Fambro[5] sang African-American spirituals to him.[7]:6, 12

Still started violin lessons in Little Rock at the age of 15. He taught himself to play the clarinet, saxophone, oboe, double bass, cello and viola, and showed a great interest in music.[citation needed] At 16 years old, he graduated from M. W. Gibbs High School in Little Rock.[7]:3

His mother wanted him to go to medical school, so Still pursued a Bachelor of Science degree program at Wilberforce University, a historically black college in Ohio.[2] Still became a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. He conducted the university band, learned to play various instruments, and started to compose and to do orchestrations. He left Wilberforce without graduating.[1]:7

Upon receiving a small amount of money left to him by his father, he began studying at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.[3] Still worked for the school assisting the janitor, along with a few other small jobs outside of the school, yet still struggled financially.[3] When Professor Lehmann asked Still why he wasn't studying composition, Still told him honestly that he couldn't afford to, leading to George Andrews agreeing to teach him composition without charge.[3] He also studied privately with the modern French composer Edgard Varèse and the American composer George Whitefield Chadwick.[4]:249[5]

On October 4, 1915,[5] Still married Grace Bundy, whom he had met while they were both at Wilberforce.[1]:1,7 They had a son, William III, and three daughters, Gail, June, and Caroline.[5] They separated in 1932 and divorced February 6, 1939.[5] On February 8, 1939, he married pianist Verna Arvey, driving to Tijuana for the ceremony because interracial marriage was illegal in California.[1]:2[5] They had a daughter, Judith Anne, and a son, Duncan.[1]:2[5] Still's granddaughter is journalist Celeste Headlee by way of Judith Anne.

On December 1, 1976, his home was designated Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #169. It is located at 1262 Victoria Avenue in Oxford Square, Los Angeles.[8]

Career

In 1916 Still worked in Memphis for W.C. Handy's band.[5] In 1918 Still joined the United States Navy to serve in World War I. After the war he went to Harlem, where he continued to work for Handy.[5] During his time in Harlem Still was involved with other important cultural figures of the Harlem Renaissance such as Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, Arna Bontemps, and Countee Cullen, and is considered to be part of that movement.[9]

He recorded with Fletcher Henderson's Dance Orchestra in 1921,[10]:85 and later played in the pit orchestra for Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake's musical, Shuffle Along[1]:4 and in other pit orchestras for Sophie Tucker, Artie Shaw, and Paul Whiteman.[11] With Henderson, he joined Henry Pace's Pace Phonograph Company (Black Swan).[12] Later in the 1920s, Still served as the arranger of "Yamekraw", a "Negro Rhapsody" (1930), composed by the Harlem stride pianist James P. Johnson.[13]

In the 1930s Still worked as an arranger of popular music, writing for Willard Robison's Deep River Hour and Paul Whiteman's Old Gold Show, both popular NBC Radio broadcasts.[11]

Still's first major orchestral composition, Symphony No. 1 "Afro-American", was performed in 1931 by the Rochester Philharmonic, conducted by Howard Hanson.[5] It was the first time the complete score of a work by an African American was performed by a major orchestra.[5] By the end of World War II the piece had been performed in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Berlin, Paris, and London.[5] Until 1950 the symphony was the most popular of any composed by an American.[14] Still developed a close professional relationship with Hanson; many of Still's compositions were performed for the first time in Rochester.[5]

In 1934 Still moved to Los Angeles. He received his first Guggenheim Fellowship[15] and started work on the first of his eight operas, Blue Steel.[16]

In 1936, Still conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl; he was the first African American to conduct a major American orchestra in a performance of his own works.[17][11]

Still arranged music for films. These included Pennies from Heaven (the 1936 film starring Bing Crosby and Madge Evans) and Lost Horizon (the 1937 film starring Ronald Colman, Jane Wyatt and Sam Jaffe).[5] For Lost Horizon, he arranged the music of Dimitri Tiomkin. Still was also hired to arrange the music for the 1943 film Stormy Weather, but left the assignment because "Twentieth-Century Fox 'degraded colored people.'"[5]

Still composed Song of a City for the 1939 World's Fair in New York City.[18] The song played continuously during the fair by the exhibit "Democracity."[18] According to Still's granddaughter, he couldn't attend the fair except on "Negro Day" without police protection.[19]

In 1949 his opera Troubled Island, originally completed in 1939, about Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti, was performed by the New York City Opera.[5] It was the first opera by an American to be performed by that company[20] and the first by an African American to be performed by a major company.[17] Still was upset by the negative reviews it received.[5]

In 1955 he conducted the New Orleans Philharmonic Orchestra; he was the first African American to conduct a major orchestra in the Deep South.[17] Still's works were performed internationally by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, and the BBC Orchestra.[citation needed]

In 1981 the opera A Bayou Legend was the first by an African-American composer to be performed on national television.[21]

Still was known as the "Dean of Afro-American Composers".[9][17] Still and Arvey's papers are held by the University of Arkansas.[9]

Legacy and honors

- Still received three Guggenheim Fellowships in music composition (1934, 1935, 1938)[15] and at least one Rosenwald Fellowship.[11]

- In 1949, he received a citation for Outstanding Service to American Music from the National Association for American Composers and Conductors[5]

- In 1976, his home in Los Angeles was designated a Historic-Cultural Monument.[8][22]

- He was awarded honorary doctorates[5] from Oberlin College, Wilberforce University, Howard University, Bates College, the University of Arkansas, Pepperdine University, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, and the University of Southern California.[citation needed]

- He was posthumously awarded the 1982 Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters award for music composition for his opera A Bayou Legend.[5][23]:6

Selected compositions

Still composed almost 200 works, including eight operas,[24]:200 five symphonies,[24]:200 four ballets,[25] plus art songs, chamber music, and works for solo instruments.[5] He composed more than thirty choral works.[11] Many of his works are believed to be lost.[5]:278

- Saint Louis Blues (comp.W.C.Handy; arr.Still; 1916)[26][27]:310

- Hesitating Blues (comp.W.C.Handy; arr.Still; 1916)[27][28]

- From the Land of Dreams (1924)[5][2]:4

- Darker America (1924)[4]:251

- From the Journal of a Wanderer (1925)[29]:224

- Levee Land (1925)[4]:251

- From The Black Belt (1926)[4]:252

- La Guiablesse (1927)[5]

- Yamekaw, a Negro Rhapsody (comp.J.P.Johnson; arr.Still; 1928)

- Sahdji (1930)[2]:4

- Africa (1930)[5]

- Symphony No. 1 "Afro-American" (1930, revised in 1969)[4]:253

- A Deserted Plantation (1933)[2]:4

- The Sorcerer (1933)[2]:4

- Dismal Swamp (1933)[4]:251

- Kaintuck (1933)[4]:252

- Blue Steel (1934)[2]:4

- Three Visions (1935)[4]:253

- Summerland (1935)[4]:253

- A Song A Dust (1936)[4]:253

- Symphony No. 2, "Song of A New Race" (1937)[4]:253[25]

- Lenox Avenue (1937)[4]:252

- Song of A City (1938)[4]:253

- Seven Traceries (1939)[2]:5

- And They Lynched Him on A Tree (1940)[4]:251

- Miss Sally's Party (1940)[2]:5

- Can'tcha line 'em, for orchestra (1940)[2]:5

- Old California (1941)[4]:252

- Troubled Island, opera, produced 1949 (1937–39)[5]

- A Bayou Legend, opera (1941)[5]

- Plain-Chant for America (1941)[4]:252

- Incantation and Dance (1941)[2]:5

- A Southern Interlude (1942)[2]:5

- In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died for Democracy (1943)[4]:252

- Suite for Violin & Piano (1943)[2]:5

- Festival Overture (1944)[4]:251

- Poem for Orchestra (1944)[4]:252

- Bells (1944)[4]:251

- Symphony No. 5, "Western Hemisphere" (1945, revised 1970)[4]:253[25]

- From The Delta (1945)[4]:252

- Wailing Woman (1946)[2]:5

- Archaic Ritual Suite (1946)[4]:251

- Symphony No. 4, "Autochthonous" (1947)[4]:253

- Danzas de Panama (1948)[4]:251

- From A Lost Continent (1948)[4]:251

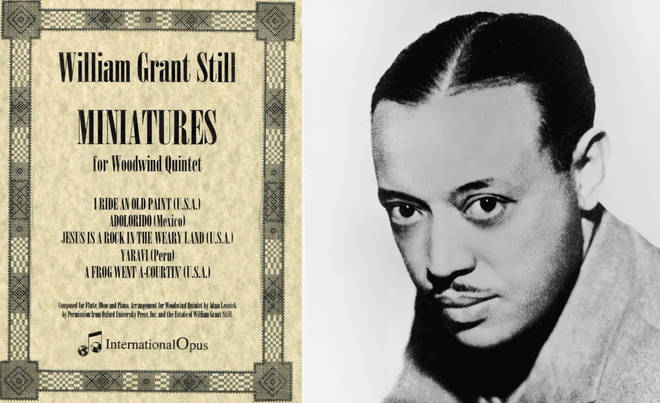

- Miniatures (1948)[4]:250

- Constaso (1950)[4]:251

- To You, America (1951)[4]:253

- Grief, originally titled as Weeping Angel (1953)[citation needed]

- The Little Song That Wanted To Be A Symphony (1954)[4]:252

- A Psalm for The Living (1954)[4]:252

- Rhapsody (1954)[4]:252

- The American Scene (1957)[4]:251

- Serenade (1957)[4]:252

- Ennanga (1958)[4]:251[2]:6

- Symphony No. 3, "The Sunday Symphony" (1958)[4]:253[30]

- Lyric Quartette (1960)[2]:7

- Patterns (1960)[4]:252

- The Peaceful Land (1960)[4]:252

- Preludes (1962)[4]:252

- Highway 1 USA (1963)[4]:252

- Folk Suite No. 4 (1963)[4]:251

- Threnody: In Memory of Jan Sibelius (1965)[4]:253

- Little Red School House (1967)[4]:252

- Little Folk Suite (1968)[4]:252

- Choreographic Prelude (1970)[4]:251

See also

- Black conductors

- List of African-American composers

- List of jazz-influenced classical compositions

- Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, early Black British composer

Sources

- Horne, Aaron. Woodwind Music of Black Composers, Greenwood Press, 1990. ISBN 0-313272-65-4

- Roach, Hildred. Black American Music. Past and Present, second edition, Krieger Publishing Company 1992. ISBN 0-894647-66-0

- Sadie, Stanley; Hitchcock, H. Wiley. The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, Grove's Dictionaries of Music, 1986. ISBN 0-943818-36-2

Further reading

- Reef, Catherine (2003). William Grant Still: African American Composer. Morgan Reynolds. ISBN 1-931798-11-7

- Sewell, George A., and Margaret L. Dwight (1984). William Grant Still: America's Greatest Black Composer. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi

- Southern, Eileen (1984). William Grant Still – Trailblazer. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

- Still, Verna Arvey (1984). In One Lifetime. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

- Still, Judith Anne (2006). Just Tell the Story. The Master Player Library.

- Still, William Grant (2011). My Life My Words, a William Grant Still autobiography. The Master Player Library.

External links

- William Grant Still Music, Official Site

- Bibliography at Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- William Grant Still, A Study in Contradictions, University of California

- William Grant Still, Interview, African American Music Collection, University of Michigan

- William Grant Still, "Composer, Arranger, Conductor & Oboist". Extensive info at AfriClassical.com

- William Grant Still and Verna Arvey Papers, University of Arkansas, Special Collections Department, Manuscript Collection MC 1125

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/the-harlem-renaissance-and-american-music-by-mike-oppenheim.php

The Harlem Renaissance and American Music

The Harlem Renaissance and the "New Negro"

One of the most

significant intellectual and artistic trends of twentieth century

American history, the Harlem Renaissance impacted art, literature, and

music in a manner that forever altered the American cultural landscape.

The Harlem Renaissance was a movement in the 1920s through which

African-American writers, artists, musicians, and thinkers sought to

embrace black heritage and culture in American life. This shift towards a

more politically assertive and self-confident conception of identity

and racial pride led to the establishment of the concept of the "New

Negro," coined by Alain Locke.

While describing the "New Negro,"

Locke referred to a renewed intellectual curiosity in the study of

black culture and history among the African-American population. This

evaluation of identity required an honest representation of the

African-American experience. The adoption of serious portrayals of black

American life in art, as opposed to the caricatures provided through

minstrelsy and vaudeville, was a necessary step in the cultivation of

the Harlem Renaissance ideals. To Locke, the black artist's objective

was to "repair a damaged group psychology and reshape a warped social

perspective" (1968:10). Significantly, these goals were most immediately

attainable through the "revaluation by white and black alike of the

Negro in terms of his artistic endowments and cultural contributions,

past and prospective" (ibid.:15). For the thinkers and artists of the

Harlem Renaissance, the way to achieve this revaluation was through

incorporating themes of black identity and history into their works.

The

perception of Africans and African-Americans as essential cultural

contributors became significant in the social struggles black Americans

faced in the twentieth century. Using the concept of the "New Negro,"

artists of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond sought to bring black

culture from the status of folk art to a position of sophistication and

dignity.

William Grant Still,

the most prominent African-American art music composer of the time, was

greatly influenced by the concept of the "New Negro," a theme

frequently evident in his concert works. Duke Ellington, a renowned jazz artist, began to reflect the "New Negro" in his music, particularly in the jazz suite Black, Brown, and Beige

. The Harlem Renaissance prompted a renewed interest in black culture

that was even reflected in the work of white artists, the most well

known example being George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.

Through applying the concept of the "New Negro," the depiction of

African-Americans in American art music shifted from a misrepresentative

stereotype to a depiction of people of African descent as significant

contributors to the American cultural landscape.

William Grant Still: Tone Poems and Operas

The composer most often associated with the Harlem Renaissance and

African-American art music is William Grant Still, a prominent figure

musically, socially, and politically. A major factor contributing to the

birth of the Harlem Renaissance was the emergence of an educated black

middle-class, to which William Grant Still belonged. Still began

studying music at Wilberforce University in 1911 with the goal of

composing concert music and opera. Still produced several instrumental

works, choral works, and operas during his career, often championing

black culture and sometimes overtly criticizing American society (such

as in the 1940 choral work And They Lynched Him on a Tree).

The values introduced by the Harlem Renaissance are clearly discernible in Still's Afro-American Symphony,

composed in 1930, and heavily based on the blues "to prove that the

Negro musical idiom is an important part of the world's musical culture"

(Murchison 2000:52). Still incorporated the blues scale and blue notes

(flat third and flat seventh), call-and-response structure, and

descending melodic contours typical of the blues into the art music

genre of a symphony, merging black culture and "high art."

Additionally, the Afro-American Symphony

is a programmatic work, or tone poem, intended to be an emotional or

psychological portrait of the African-American experience. In this

representation of black America, Still aimed to express emotional

longing, sorrow, and the aspirations of the "Old Negro," themes overcome

through hope and prayer in his later tone poems. This series of tone

poems presents Still's conception of the history, culture, and

psychology of African-Americans; in his representation black Americans

rise up from a history of slavery and sorrow to a position of

self-empowerment and triumph.

The 1939 opera Troubled Island,

a collaborative effort between William Grant Still and the poet

Langston Hughes, features an even more attentive representation of black

cultural history than Still's tone poems. Hughes' libretto is based on

his 1928 play Drums of Haiti. The opera is about the rise and

fall of Haiti's first emperor, Jean Jacques Dessalines. Dessalines leads

the Haitian revolt against French colonials and installs himself in

power, yet as the emperor, he laments his own illiteracy and ignorance

when requested to provide a teacher for one of his villages. The opera

concludes with Dessalines death at the hands of a revolting population.

Dessalines

rise to power represents the elevation of the African-Americans,

paralleling the rise from slavery depicted in Still's tone poems. The

themes of sorrow and ignorance are again presented to contrast with the

concept of the educated and hopeful "New Negro." Troubled Island

challenges the viewer to contemplate the importance of history,

education, and the cultural contributions of black America to American

culture in general.

William Grant Still's music exemplifies the incorporation of Harlem

Renaissance ideals into art music through expressing African-American

heritage in his music. In addition to championing black culture as a

composer, Still broke several racial barriers in the American music

scene. His Afro-American Symphony was the first symphony

composed by an African-American and performed by a major orchestra, and

he was the first black American to conduct a white radio orchestra (Deep River Hour,

1932), conduct a major orchestra (the Los Angeles PO in 1936), or

receive a series of commissions from major American orchestras.

Duke Ellington: Beyond the "Jungle Sound"

Duke Ellington provides an interesting contrast to his contemporary,

William Grant Still. While both are among the most prominent composers

of the Harlem Renaissance, they came from strikingly different

backgrounds. Ellington was never formally trained in music; he began

studying piano at age seven, taught himself harmony at the piano, and

learned orchestration through experimentation with his band. Ellington

is best known as a big band leader and arranger, as a songwriter, and as

the voice of "jungle music." In the 1920s and early 1930s Ellington's

band was the house band for Harlem's Cotton Club. Far from

sophistication, the Cotton Club gigs often featured jungle decor and

elaborate costumes to accompany the "jungle sound," intended to imply

the "exotic" music of Africa.

Despite Ellington's early

involvement with the Cotton Club he eventually embraced the beliefs of

Alain Locke and sought to present black music as high art, most notably

achieved when his suite Black, Brown, and Beige

debuted at Carnegie Hall in 1943. In 1930, Ellington expressed the

desire to compose a work that would serve as a musical history of the

black experience; beginning in Africa, progressing through Southern

slavery, and finally to Harlem (Tucker 2002: 69). This framework

eventually became Black, Brown, and Beige, though it was not

composed for over a decade after its conception. However, during this

period Ellington did compose several pieces dealing with

African-American themes including Symphony in Black in 1934, Jump for Joy in 1941, and the unfinished opera Boola.

Black, Brown, and Beige

was Ellington's conception of a "tone-parallel," illustrating the

history of black Americans. The composition is accompanied by poetry

penned by Ellington, depicting the scenes that the music is meant to

evoke. The overall work is divided into three sections, which are

further divided into songs. The first section, Black, first depicts blacks in Africa and proceeds to give a narrative of life as a Southern slave. Black

consists of "Work Song," "Come Sunday," and "Light;" these songs and

poems represent the ideas of the sorrow of slavery, the redemption of

faith, and the hope for a better future. Brown depicts the triumph of blacks over the oppression of slavery in the song "Emancipation Proclamation." The work ends with Beige, which celebrates Harlem and depicts African-Americans as a community characterized by pride and knowledge.

Composed with the goal of racial advancement, Black, Brown, and Beige

expresses racial pride and history, the celebration of African-American

identity, and the social progress of black Americans in the twentieth

century. The structure of the work emphasized the continuity of black

history from slavery to the present. Brown deals with the

sacrifices made by black soldiers in the Revolutionary War and connects

it to the black soldiers participating in the Second World War; clearly

marking African-Americans as loyal and dedicated American citizens.

Ellington aimed to correct "the common misconception of the Negro which

has left a confused impression of his true character and abilities,"

through his portrayal of modern black America (DeVeaux 1993:129

Though

Ellington presented African-Americans as culturally distinct, he sought

to draw this identity into unity with American culture. The final

movement is accompanied by the text "We're black, brown and beige but

we're red, white and blue!" (ibid.:132). In the midst of World War II

Ellington aimed not only for the social advancement of

African-Americans, but for the unity of the United States as a whole.

That Black, Brown, and Beige was performed in Carnegie Hall is also significant. First, it elevated

black music to the premier American concert hall; and second, it broke

social barriers by bringing a significantly large black audience into a

white venue.

George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess as it Reflects the Harlem Renaissance

George Gershwin began formally studying piano in 1912, focusing on

works by classical composers such as Liszt, Chopin, and Debussy, but by

the age of fifteen Gershwin worked as a song-plugger on Tin Pan Alley.

Living in New York, Gershwin was in prime location to take notice of the

happenings of the Harlem Renaissance. His compositions show significant

influence from African-American musical styles. Gershwin's use of the

blues scale and jazz syncopation is heard in several of his songs and

larger compositions, particularly in 1924's Rhapsody in Blue.

Gershwin demonstrated that jazz, a black music, was worthy of elevation

to symphonic arrangements and performance on the concert stage. As a

result Gershwin is credited as the first to bring jazz into the concert

hall.

Porgy and Bess, a collaboration between Gershwin

and writer DuBose Heyward, was conceived as a folk opera based on the

lives of African-Americans in Charleston, South Carolina. The libretto

is based on a work of Heyward's entitled Porgy. Porgy

was intended to be a "Negro novel" that would "leave an authentic record

[of black life in] the period that produced it" (Crawford 1972:18). In

1926, one year after its publication, Gerswhin contacted Heyward with

the idea for Porgy and Bess. Though he was already using

aspects of black music such as syncopation and blue notes, Gershwin

decided to visit Heyward in Charleston, South Carolina to "hear some

spirituals and perhaps go to a colored café or two," in order to

experience the local culture and music firsthand (ibid.:20).

Gershwin's Porgy and Bess does not represent black

characters in the context of the "New Negro." In fact, it seems to

adhere to the existing stereotypes that the artists of the Harlem

Renaissance sought to discredit. Gershwin and Heyward's approach to the

topic of the African-American experience differs from those of William

Grant Still and Duke Ellington. Still and Ellington both created a

cultural history of African-Americans culminating in the establishment

of black communities in urban centers. Porgy and Bess was an

attempt to create a representation of rural black life, contrary to

Harlem Renaissance ideals of the sophisticated, city-dwelling "New

Negro." As a result, Gershwin was accused of creating "fakelore," or

pseudo-folklore, denigrating the black community through the portrayal

of their culture as quaint and primeval.

Musically, Porgy and Bess

tells a different story of black culture. Gershwin continued to

incorporate the blues scale, syncopated rhythm, and call-and-response

technique into the score. More importantly though, Gershwin made use of

the practice of "signifying" African-American music, showing a degree of

perception and understanding of black music and culture not expressed

in the libretto.

Signifying is the practice of quoting ideas

from another song or musical form of black origin (i.e., gospel,

spirituals, blues). Signifying is seen in jazz, the blues, spirituals,

and ragtime; it is important because it connects all of these forms

through their African-American origin. "Summertime," which occurs

throughout Porgy and Bess, features excellent examples of

signifying. The spiritual "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" is

actually the basis for "Summertime." Gershwin used the intervallic

structure and the rhythm (in augmentation) from the spiritual to create a

new piece of music that maintains an identity as a product of black

culture, linking black culture and history to contemporary America

(Floyd 1993).

Towards a New Perception of American Identities

Bibliography

Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. 1993. "Troping the Blues: From Spirituals to the Concert Hall." Black Music Research Journal 13(1): 31-51.

Locke, Alain. 1968. "The New Negro," in The New Negro: An Interpretation. Edited by Alain Locke. New York: Arno Press.

Murchison, Gayle. 2000. "'Dean of Afro-American Composers' or 'Harlem Renaissance Man': The New Negro and the Musical Poetics of William Grant Still," in William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions. Edited by Catherine Parsons Smith. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Tucker, Mark. 2002. "The Genesis of 'Black, Brown, and Beige.'" Black Music Research Journal 22: 131-150.

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

"The Dean of Afro-American Composers"

May 11, 1895 - December 3, 1978

William Grant Still is remembered for many musical and historical achievements, including becoming the first African-American...

To conduct a major symphony orchestra in the United States.

To direct a major symphony orchestra in the Deep South.

To conduct a major American network radio orchestra.

To have an opera produced by a major American company, and...

To have an opera televised over a national network in the

United States, (after his death ).

https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/how-composer-william-grant-still-changed-classical-music/

How William Grant Still, the ‘Dean of Afro-American composers’, changed American classical music forever

16 October 2020

Classicfm.con

William Grant Still.

Picture:

Getty / International Opus

William Grant Still was the first American to have an opera produced by New York City Opera, and the first African American composer to conduct a major US symphony orchestra – here’s everything you have to know about the ‘Dean’ of Black classical music.

“William Grant Still will conduct two of his own works.”

With that, The Los Angeles Times’ music and dance critic, Isabel Morse Jones, nonchalantly tabulated one of the most momentous occasions in American classical music history – that on 23 July 1936, at Hollywood Bowl, a Black conductor would lead a major US orchestra in concert, for the very first time.

When William Grant Still took to the podium at the helm of the LA Philharmonic, he was just ticking off a “first” of the many “firsts” that defined his career. Still was also the first American composer to have an opera performed by the New York City Opera and the first African American composer to have an opera performed by a major company; the first African American to have a symphony performed by a major US orchestra; and the first to have an opera performed on National TV.

Dubbed ‘The Dean of African American Composers’, Still composed more than 150 works, including five symphonies – his first of which was the most-performed symphony of any American for a long time – eight operas, and numerous other works. He was also a conductor, arranger and oboist.

Read more: 9 Black composers who changed the course of music history >

Read more: Discover the life and music of Scott Joplin, the ‘King of Ragtime’ >

Who was William Grant Still?

William Grant Still was born on 11 May in 1895. His mother, Carrie Lena Fambro, and his father, William Grant Still Sr, were both teachers.

His father died when Still was young, and music came from his stepfather, who encouraged him from a young age. Still took violin lessons from 15, and also taught himself to play the clarinet, saxophone, oboe, bass, cello and viola.

At his mother’s encouragement, Still studied medicine at university, but never completed the course. While at university, he stayed heavily involved with music, playing in university orchestras and bands, and he eventually got to Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio to further his musical studies.

His composer credentials come from a teacher lineage that includes French revolutionary Edgard Varèse among others, and Still combined this classical clout with his passion for folk- and jazz-inspired styles.

Depicting the African American experience through orchestral music

Grant Still incorporated the blues, spirituals, jazz, and other ethnic American music into his orchestral and operatic compositions.

His orchestral piece, Wood Notes, depicts Still’s love of nature. And works like his ‘Afro-American’ Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2, the symphonic tone poem Africa, and his ballet Sahdji all “depict the African American experience” and “present the vision of an integrated American society.”

William Grant Still is very much considered part of the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ movement, which highlighted and celebrated African American intellectual, social, and artistic contributions to American cultural life, fanning out from Harlem in New York.

His works were performed internationally by the best orchestras in the world, including the Berlin Phil, the London Symphony Orchestra and Tokyo Philharmonic.

Other contributions to musical life

As well as being a prolific composer of symphony, opera and ballet works – many of which highlighted struggles of Black lives in America, including The Troubled Island and Highway No. 1 USA – William Grant Still also worked for ‘Father of the Blues’ W.C. Handy in Memphis.

Still was a prolific arranger of pop music, and played in pit bands and for recordings, including for pianist Fletcher Henderson, singer Sophie Tucker and jazz clarinet Artie Shaw, and many others.

He also arranged movie music, including for Pennies from Heaven (1936) and Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon.

William Grant Still received an honour for Outstanding Service to American Music from the National Association for American Composers and Conductors, and had a raft of honorary doctorates, reflecting the extraordinary contribution he made to classical music history in America – and the world.

Still died on 3 December 1978 in LA.

Hear William Grant Still’s music played by Chi-chi Nwanoku OBE, the founder of the Chineke! Foundation, on Chi-chi’s Classical Champions, and during other programmes on Classic FM.

Click here to catch up with Chi-chi’s Classical Champions on Global Player, the official Classic FM app.

https://www.allclassical.org/black-history-month-william-grant-still/

Black History Month: William Grant Still

Since 1976, the United States has officially recognized February as Black History Month, an annual time to recognize the central roles blacks have played in U.S. history and a celebration of the achievements of African Americans in our culture and society. All Classical Portland will be joining the celebration of Black History Month, featuring some of the best recordings of composers of African origin (American, and around the world).

One of the critical values of classical music (and of art in general)

is that it allows listeners to hear the world through different lenses.

Through their unique set of backgrounds, experiences, and values,

composers create works that expose their audiences to humanity’s rich

variety of perspectives and cultural traditions. However, as an art that

draws from a primarily western European tradition, celebrating

diversity is also one of classical music’s greatest challenges to

overcome. Even today, black composers remain on the outskirts of the

classical music establishment. Social prejudices, as well as other

factors, have excluded them from entering the classical canon, which

continues to be largely dominated by white, male composers. However,

African-Americans have deeply influenced the orchestral tradition in the

United States and beyond.

One of the most prominent African American contributors to the history of classical music was William Grant Still (1895-1978), a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance and known to his colleagues as the “Dean of Afro-American composers.” Born in Mississippi and raised in Arkansas, Still took formal violin lessons and taught himself clarinet, saxophone, oboe, viola, cello and double bass. He was interested in pursuing a college music education, but his mother pushed him to study medicine at Wilberforce University in Ohio, concerned that societal limitations would prevent a successful career as a black composer. Nevertheless, Still later dropped out of Wilberforce and entered Oberlin University to study music.

Still had a diverse musical training. He wrote jazz arrangements for

blues masters and bandleaders such as Artie Shaw, Paul Whiteman and W.C.

Handy, but also received formal instruction from composers including

George Chadwick of the first New England school, and the French

modernist composer Edgard Varèse. Over his career, Still wrote over 150

compositions, including operas, ballets, symphonies, chamber works,

choral pieces, and solo vocal works.

Still broke racial barriers and earned many “firsts” in the realm of classical music. He was the first African American to conduct a major symphony orchestra in the United States, as well as first to have an opera produced by a major company in the United States. Additionally, Still composed the first symphonic work by a black composer to be performed by a major U.S. orchestra, the Afro-American Symphony, premiered by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in 1931 under the direction of Howard Hanson. On Thursday, February 1st, All Classical will be featuring this work alongside some of the other greatest works by African-American composers.

The Afro-American Symphony fits within the standard framework of a European four-movement symphony but incorporates African American musical idioms throughout the piece. By blending jazz, blues, and spirituals into a traditional classical form and placing them within the context of the concert hall, Still highlights these styles as something to be celebrated, rather than downcast as low class or vulgar music. Let’s explore the ways that Still interweaves these three African American idioms – jazz, blues, and spirituals – into his Afro-American Symphony, with a focus on the first movement.

The Afro-American Symphony is scored for full orchestra, including celeste, harp, and tenor banjo (the piece was the first time a banjo had been used in symphonic music). The symphony has a typical sonata-form first movement, a slow movement, a scherzo, and a fast finale. While Still did not intend the Afro-American Symphony to be an explicitly programmatic piece, his notebooks did include alternate titles for each movement (“Longing,” “Sorrow,” “Humor,” and “Aspiration”). After completion of the symphony, Still linked each movement to verses from poems by the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), which heighten the emotional impact of each movement. Dunbar was one of the first African American poets to achieve a national reputation from both white and black audiences. His accurate portrayals of African American life in the South using folk materials and dialects aptly complement Still’s efforts to interweave African and European traditions in his piece.

William Grant Still: Afro-American Symphony - I. Moderato Assai:

For the music itself, the opening movement begins with an introductory melody by the English horn, followed by the first theme played by a muted trumpet, a blues melody adapted from W.C. Handy’s Saint Louis Blues. This tune becomes a prominent centerpiece, reappearing in altered forms throughout both the first movement and the symphony as a whole. We might now think of blues music as any sort of sad, downcast kind of song, but the blues has a rich African American history, beginning as a folk style that developed in the southern United States and becoming a standard genre by the end of the nineteenth century.

Since the 1920s, the blues has helped shape jazz, country music,

and rock’n’roll, and many other popular musical genres. Still’s melody

has several key features that make it a classic blues tune, including

its use of the standard twelve-bar blues harmonic progression, a swung

rhythm, and a use of lowered fifth, third, and seventh scale degrees in

the melody that imitate “blue” notes. Still was aware that inserting a

blues tune into his symphony could cause some listeners to perceive it

as unrefined. However, as he writes in his sketchbook, his decision to

place the tune at the forefront of the piece reflects his fierce defense

of blues as a powerful emblem of African American identity:

“I harbor no delusions as to the triviality of the Blues, the secular folk music of the American Negro, despite their lowly origin and the homely sentiment of their texts. The pathos of their melodic content bespeaks the anguish of human hearts and belies the banality of their lyrics. What is more, they, unlike many Spirituals, do not exhibit the influence of Caucasian music.”

Other elements throughout the movement reflect characteristic

features of African American music. Later, for example, the first theme

repeats in the clarinet, this time with interjections from other winds.

These interjections between short phrases of melody suggest the

“call-and-response” style found in much African music. Still also

frequently uses syncopation in the melody and accompaniment (rhythms

with accents displaced on the weak beat) and chords including both major

and minor thirds, further suggesting African American-influenced jazz

music.

Also of note is Still’s unusual instrumental timbres. Still groups

instruments together to create sounds typical of jazz big bands,

including trumpets and trombones with Harmon mutes, drum set effects

such as steady taps on the bass drum, dampened strikes on the cymbal,

and col legno (on the wood of the bow) rhythms in the violins.

All of these factors give a nod to the seminal influence of jazz as the

style that became most associated with America between the two World

Wars. American classical composers seeking a way to write music that was

distinctly “American” took advantage of the new idiom of jazz as

inspiration, including George Gershwin, Marc Blitzstein, and Leonard

Bernstein. Jazz also influenced classical composers in Europe, including

Erik Satie and Igor Stravinsky.

As the first movement continues to develop the jazzy melodies from the first theme, however, it transitions to a second theme with a melancholy mood, with pentatonic contours suggestive of an African American spiritual. Spirituals originated when slaves heard hymns upon conversion to Christianity and used the hymns as musical models, applying their own ideas to Biblical texts with themes of longing freedom from bondage. Still’s combination of blues and spiritual-influenced music fittingly reflects movement’s subtitle of “Longing” while sharing a core aspect of the African American experience with his audience.

William Grant Still: Afro-American Symphony - II. Adagio:

The rest of the symphony continues with this fusion of African

American experience into classical European form. The second movement, Adagio

(“Sorrow,”) continues with themes that relate to the first movement but

carrying on in the spiritual style. The third movement, Animato

(“Humor”), presents a pair themes and variations. Interestingly,

several measures into the first theme is a tune that closely resembles

Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.” Did Gershwin get his melody from Still, or

was it the other way around? While scholars haven’t reached a decisive

conclusion, musicologist Catherine Parsons Smith suggests that Still

believed Gershwin had picked up the melodic and rhythmic ideas of the

tune from improvisations by Still while playing in the orchestra pit of Shuffle Along

ten years earlier. Either way, the melody is a joy to listen to, and in

addition to the more fanfare-like second theme the movement echoes the

themes of African American emancipation and empowerment in the Dunbar

poem attached to the movement. The final movement, Lento con risoluzione (“Aspiration”),

begins with a poignant hymn-like section reminiscent of gospel and

choral music, and gradually culminates into a lively finale.

The Afro-American Symphony is a compelling reflection of

Still’s diverse range of experiences as a composer and musician. Still’s

incorporation of three prominent forms of African American music into

his piece, the blues, jazz, and spirituals, creates a unique symphonic

style that celebrates the complexity and richness of the black

experience in the post-Civil War musical era. Since the 1931 premiere of

the Afro-American Symphony, Still’s multifarious style has

gone on to influence even non-classical music. In 1934, Still moved to

Los Angeles, where he composed music for films alongside his classical

works, helping shape a style that other composers and arrangers used for

scoring films and popular music. The Afro-American Symphony,

however, remains as Still’s landmark piece, and remains one of the most

frequently performed symphonies by an American composer in the United

States. Bringing together a lifetime of musical experiences, it has

earned a place in the canon of the Western classical music tradition not

in spite of, but because of its daring and creative integration of African American and European idioms.

Hungry for more listening? Music Director John Pitman also has some recommended recordings of Still’s works from All Classical’s music library. John chose a particular recording of Still’s Symphony for several reasons:

“The performance, by the Cincinnati Philharmonia Orchestra, is especially bright and full of life. There are also two rare gems by the composer on the CD, and a work by Olly Wilson called Expansions II, which connects Still’s mid-century music to more recent times. The liner notes are especially valuable, as they include several paragraphs by the composer’s daughter, Judith Anne Still, who has dedicated her life to preserving her father’s important contribution to American music.”

If you are interested in listening to this CD, it can be purchased via this link to Arkivmusic.com. When purchasing the CD using this link, All Classical’s programming receives 10% from the sale.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for more blog posts this month featuring composers, conductors and musicians in celebration of Black History month, including Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, André Watts, Kathleen Battle and more!

References

- Burkholder, J. Peter, Grout, Donald Jay, and Palisca, Claude V. A History of Western Music. 9th New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014. Print.

- Burkholder, J. Peter, and Palisca, Claude V. Norton Anthology of Western Music. Volume Three: The Twentieth Century and After. 7th New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014. Print.

- “Dunbar and Still.” Duke Library. Web. Accessed 30 Jan 2018. https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/scriptorium/sgo/texts/dunbar.html

- Latshaw, Charles William. “William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony: A Critical Edition.” Indiana University, doctoral dissertation, May 2014. Web. Accessed 30 Jan 2-18. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/17492/Latshaw%2C%20Charles%20%28DM%20Orch%20Cond%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- O’Bannon, Ricky. “Listening Guide: William Grant Still.” Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. Web. Accessed 30 Jan 2018. https://www.bsomusic.org/stories/listening-guide-william-grant-still/

- “Symphony No. 1 “’Afro-’”Wikipedia.com. Web. Accessed 30 Jan 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._1_%22Afro-American%22

- William Grant Still. Richard Fields, Piano. Cincinnati Philharmonia Jindong Cai, conductor. CD. Centaur: CRC 2331.

Symphony No.1 in A flat major "Afro-American" - William Grant Still

Symphony No.2 in G minor "Song of a New Race" - William Grant Still

Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Neeme Järvi

I

Slowly: 0:00

II

Slowly and deeply expressive: 9:55 III

Moderately fast: 18:17 IV

Moderately slow: 22:00

The Symphony No.2 in G minor by William Grant Still was completed in 1937, premiered on December 10, 1937, performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski. The structure of the symphony is identical to his first symphony. A classic style in four movements, inherited from Brahms, in which the weight of the work falls on the extreme movements, being the two central ones more lighter. If we analyze the internal structure of each of the movements we will see that it is identical to the one used previously. The first movement, Slowly, begins with a brief introduction, presenting the main theme of the work, a new blues theme. This theme is developed before the interpretation of the second theme, a lyrical theme of noble grandeur. After a brief development, the recapitulation presents the themes in reverse. The main theme leads us to a conclusive coda. Corresponds to the longings of his previous symphony, but now, what was once only a project, has been realized. The second movement, Slowly and Deeply Expressive, begins presenting a sweet theme, which develops until its conversion into the main theme. Presented by the first violin, it consists of a characteristic theme of folk affinity. Its development leads us to moments of romanticism, until being interrupted by a new theme of rhythmic character. But a brief climax brings us back to the main theme that is recapitulated. The coda, with a more agitated character, acts as a link with the next movement, which is interpreted without interruption. The feelings of pain of his first symphony have become a spiritual development of these feelings, to achieve the greatness of his goals. The third movement, Moderately Fast, which corresponds to the scherzo, presents us with an air of folkloric dance, typically of the American ragtime. Classic jazz motifs adorn the theme. The music shows the style of symphonic jazz cultivated by white Americans. The religious exaltation of his previous Humor, has been moderated to approach the religiosity of other peoples. The last movement, Moderately Slow, presents a theme derived from the blues of the first movement. Its development becomes more classical, as to indicate the possible integration of black music in the patrimony of the white race. The westernized blues theme is repeated solemnly. A conclusive coda closes the work. The previous Aspirations have become the desire to offer humanity, the best heritage inherited by the Africans of America. Despite having the structure similar to his first symphony, this style is more tempered, more moderate. He has left primitivism to approach Western civilization. According to the composer himself, "the Afro-American Symphony showed the daily life of black people shortly after the period of the civil war. The Symphony in G minor describes the black people of the current America, a totally new man, as a result of the mixture of white, Indian and black bloods". Picture: “The 99 Series/Part Three" (2014) by the Ethiopian photographer Aïda Muluneh. Sources from this spanish website on Still symphonism: http://www.historiadelasinfonia.es/na...

https://portlandyouthphil.org/blog/blog/william-grant-still/454

October 12, 2018

WILLIAM GRANT STILL (part 1 of 5)

William Grant Still (with instrument case) with his friends at Wilberforce University, 1915. Photo from the holdings of the University of Arkansas Libraries’ Special Collections.

William Grant Still (1895-1978) is known as “The Dean of African-American Composers”, for good reason. The standard sites and survey history books cite the same litany of impressive firsts:

—the first African-American to conduct a major American symphony orchestra,

—the first to have a symphony (his First Symphony) performed by a leading orchestra,

—the first to have a grand opera performed by a major opera company,

—the first to have an opera performed on national television,

—the first to conduct a major symphony orchestra, the New Orleans Philharmonic, in the Deep South

Along with multiple honorary doctorates, abundant commissions, and two Guggenheim Fellowships, all these landmark accomplishments suggest a blessed, prolific career flowing smoothly from recognition to recognition. Still’s lived reality was far rockier, however, and the fate of his work, as with almost all art, was completely enmeshed in the complex racial and cultural politics of his time.

We are extremely lucky to have an abundance of Still’s writings and

speeches. He communicated in words as he did in music, presenting

nuanced ideas in an unaffected, understandable way that talks neither

above his audience, nor down to them either.

When at all possible, I’ll be quoting Still’s own words, or those of his

wife Verna Arvey, or his daughter, Judith Anne Still, or granddaughter,

Celeste Headlee, as well as various scholars. This series of entries

will cover different periods of Still’s life and work. Sources will be

referred to in an abbreviated form in the body of the entries, and

fully identified at the end of the last blog entry.

Finally, of course Still was only one of many African-American composers for the concert hall who came before and after him, each with their own particular perspective, such as R. Nathaniel Dett, who studied at Harvard, later with Nadia Boulanger, and earned a masters from Eastman; the prolific Florence Price, who graduated from the same Little Rock, Arkansas high school Still would, and was the first African-American woman to have a composition played by a major orchestra; and William Levi Dawson, whose gorgeous Negro Folk Symphony premiered in 1934. Of necessity, however, this extremely *brief* overview will have to focus on Still’s life and career in particular.

William Grant Still, who was of not only African-American, but also Spanish, Native American, and Scots-Irish ancestry, was the first generation of his family not born into slavery; one of his ancestors, William Still, was a famous African-American abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad. Born in Mississippi to two high school teachers, he grew up with all the expectations attendant to being a ‘teacher’s kid.’ His parents were also very musically inclined; his grandmother would sing him spirituals.

After William’s father passed, his mother moved the family to Little Rock and remarried. The family “lived in a comfortable middle-class home, with luxuries such as books, musical instruments, and phonograph records…” (WGS, “My Arkansas Boyhood”). Still’s stepfather collected and played ‘Victor Red Seal’ records, which was a premium label representing the highest level of classical performance including opera, and took him to stage shows, where young William fell in love with the stage. His life in Little Rock, which would become infamous for its segregation and resistance to school integration, was unusual for the time:

It is true that there was segregation in Little Rock during my boyhood, but my family lived in a mixed neighborhood and our friends were both white and colored. So were my playmates…So, while I was aware of the fact that I was a Negro, and once in a while was reminded of it unpleasantly, I was generally conscious of it in a positive way, with a feeling of pride….my association with people of both racial groups gave me the ability to conduct myself as a person among people instead of an inferior among superiors. (WGS, “Boyhood”)

His mother continued to encourage literacy in her community and took other active roles in social/cultural leadership, while planning for her son to become a doctor and community leader as well. Still thus dutifully enrolled in Wilberforce University, the nation’s first private historically black university, for pre-med studies. Nevertheless, he spent most of his time in music ensembles and spent his money on instruments.

When Still eventually decided that he wanted to be a professional composer, his mother was initially extremely upset because, as he wrote, “in her experience, the majority of Negro musicians were disreputable and were not accepted into the best homes.” As he reflected later, though,

She lived long enough to know that my initial serious compositions had been successful, and her pride knew no bounds. Although she had opposed my career in music, she finally understood that music meant to me all the things she had been teaching me: a creative, serious accomplishment worth of study and high devotion as well as sacrifice. She knew at last that the ideals which she had passed on to me during my boyhood in Arkansas had borne worthy fruit. (WGS, “Boyhood”)

Indeed, the progress of Still’s composing style seems to have been integrally motivated by a series of social ideals, his approach to music determined by what he felt to be the highest calling of his life in each period.

Click here to read part two of the series.

Carolyn Talarr

Community Programs Coordinator

11/05/18 | WILLIAM GRANT STILL (part 1 of 5)

https://portlandyouthphil.org/blog/blog/william-grant-still-early-adult-years/455/

October 10, 2018

WILLIAM GRANT STILL: EARLY ADULT YEARS (part 2 of 5)

Company photo, “Shuffle Along” on tour in Boston, 1921; Still is second from far left. Photo from Broadway Collection.

Even though William Grant Still never completed his Bachelor’s degree, in his twenties he managed to cobble together an astoundingly broad and deep musical education that was probably more multifaceted and multicultural in its outlook than any other single composer of his era. Even more astounding, he did it in and amongst the need to make money while also serving his country and navigating twentieth-century racial tensions.

In 1915, at 20 years old, Still left Wilberforce without a degree but completely set on a career in music. (In 1936 Wilberforce awarded him his first honorary degree, a Master of Music.) Luckily, he got hired to play oboe and cello in an orchestra in Cleveland and gigged around the city in various ensembles as well. While he was living job to job, he composed his first orchestral work, which proved to be characteristically entitled the American Suite, and sent it, unsolicited, to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It wasn’t performed, but the boldness is impressive in a 20 year-old!

The next year was pivotal for Still; he was hired to arrange, and play oboe and cello, in one of the bands of W.C. Handy, “the father of the Blues.” Still and Handy quickly became lifelong friends; in this era Still “made the first band arrangements ever of the historic ‘Beale Street Blues’ and ‘St. Louis Blues’” (Handy/Southern). Still commented that at this time “I had been making it a point to listen to Negro music everywhere I went. On Beale Street in Memphis…as an onlooker in small Negro churches, and in popular bands” (WGS, “Boyhood”).

Through learning about Blues in their original contexts, he “realized that the American Negro had made an unrecognized contribution of great value to American music” beyond the more socially-acceptable spirituals and folk songs:

When he reached 21 and could receive his father’s inheritance, Still enrolled in Oberlin Conservatory, although he needed to take on significant work-study as well. He couldn’t afford to take composition, but his theory professor arranged for Still to study privately with the composition professor free of charge. It was a heady few terms, cut short by Still’s enlistment in the navy in WWI.

After the war ended in 1918, Still painfully worked his way back to Ohio for a short time, studying a bit more at Oberlin, only to leave when W.C. Handy called him to New York once again, to arrange music for him and tour in his main band. One gig led to another, including playing oboe in the pit orchestra of the epochal musical Shuffle Along.

While on tour in Boston with Shuffle Along, Still reached out to the person who proved to be the second major influence on his musical philosophy: George Chadwick. Chadwick, a well-known, generally conservative composer of the time, was Director of the New England Conservatory (NEC). Florence Price had also studied with Chadwick when she attended the NEC.

Important for Still, however, was that Chadwick had evidently recently come to champion the nationalistic idea that Antonín Dvořák had advocated in the 1890s when he briefly directed the then-prestigious National Conservatory of Music in New York: the necessity of creating a purely American idiom rather than imitating European styles. Dvořák had stated that a non-European idiom would have to come from Native American and African-American musical traditions; despite initial resistance from the European-inclined American music community, his words eventually changed the course of both American and world music. Still credited his brief private study with Chadwick with “acquainting [him] with serious American music” (although his stepfather’s records had surely helped in that regard as well). (SIDE NOTE: PYP will be performing Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 as part of this same program; it was the last symphony Dvořák composed before coming to the United States. The Third Movement, Furiant, based on a traditional Bohemian [later Czech] dance, is a perfect example of Dvořák’s integration of folk music into the classical idiom.)

Back in New York, Still continued arranging for Handy’s publishing house, and then served as arranger and recording director at the first Black-owned record company, Black Swan Records. It could be said that in terms of symphonic music, Still’s “big break” happened here, when he found his third major educational influence: Edgard Varèse.

Inspired by Dvořák’s having taught many African-American musicians at the National Conservatory, the modernist Varèse wrote to Black Swan specifically asking for any promising Black composers to study avant-garde composition with him. Still happened to see the letter and jumped on the offer for himself, as he was always trying to learn from everyone he could.

It’s somewhat ironic that the “ultramodern,” “cerebral” (Still’s words) musical idiom Still acquired from this instruction, which was intended to inflect what Varèse called “[Still’s] lyrical nature, typical of his race,” was actually European in origin, not an American-originated style at all. Further, the ‘European-influenced’ American modernists would play an unexpectedly pivotal role decades later in Still’s future.

At this time, however, Still absorbed the lessons Varèse taught—yet one can hear his experiences with “Negro music” already insisting on a place at the ‘serious music’ table. After a couple of attempts, Still’s first ‘serious’ success in 1926 was the amazing tone poem Darker America, which premiered a mere 9 months after Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Such a clear document of where Still’s mind was at the time, the piece fascinatingly integrates modernist dissonances, blues and jazz.

Although Still continued to employ modernist techniques when he found them appropriate for the rest of his career, the most lasting outcome of this period was that Varèse crucially promoted Still and his music to the concertgoing community. From that point for years afterward, Still straddled the commercial world of arranging music, which was more open to African-Americans, and the less-open world of the concert hall. As Harold Bruce Forsythe, a friend and colleague who astutely subtitled his vivid 1930 biographical sketch of Still “A Study in Contradictions”, wrote affectionately, “He has hidden behind his position as an arranger of popular music…I knew him for months before I had the first inkling of his significance and before he showed me one of his orchestral scores” (Forsythe in Smith, 2000).

Click here to read part three of the series.

Carolyn Talarr

Community Programs Coordinator

11/05/18 | WILLIAM GRANT STILL: EARLY ADULT YEARS (part 2 of 5)

https://portlandyouthphil.org/blog/blog/william-grant-still-crystallizing-the-dream/456/

October 8, 2018

WILLIAM GRANT STILL: CRYSTALLIZING THE DREAM (part 3 of 5)

William Grant Still in rehearsal. From Houston Public Media.

Still’s self-identified second period took its shape, as his wife Verna Arvey later related, from a “dream dating back to 1916 when as a young man, he went to Memphis to work with W.C. Handy” (Arvey, Memo to Musicologists). Once he learned about the Blues in their original context, he resolved that he someday he would elevate the Blues so they could hold a dignified position in symphonic literature” (Arvey, Memo). Still wrote,