SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER ONE

CHARLES MINGUSJEREMY PELT

(April 17-23)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

(April 24-30)

AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS

(May 1-7)

KARRIEM RIGGINS

(May 8-14)

ETTA JONES

(May 15-21)

YUSEF LATEEF

(May 22-28)

CHRISTIAN SANDS

(May 29—June 4)

E. J. STRICKLAND

(June 5-11)

TAJ MAHAL

(June 12-18)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

(June 12-18)

DOM FLEMONS

(June 19-25)

HEROES ARE GANG LEADERS

(June 26-July 2)

Yusef Lateef

(1920-2013)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Yusef Lateef a hard-blowing tenor who greatly expanded his stylistic menu by exploring Asian and Middle Eastern rhythms, instruments, and concepts.long had an inquisitive spirit and he was never just a bop or hard bop soloist. Lateef, who did not care much for the term "jazz," consistently created music that stretched (and even broke through) boundaries. A superior tenor saxophonist with a soulful sound and impressive technique, by the 1950s Lateef was one of the top flutists around. He also developed into the best jazz soloist to date on oboe, was an occasional bassoonist, and introduced such instruments as the argol (a double clarinet that resembles a bassoon), shanai (a type of oboe), and different types of flutes. Lateefplayed "world music" before it had a name and his output was much more creative than much of the pop and folk music that passed under that label in the '90s.

Yusef Lateef grew up in Detroit and began on tenor when he was 17. He played with Lucky Millinder (1946), Hot Lips Page, Roy Eldridge, and Dizzy Gillespie's big band (1949-1950). He was a fixture on the Detroit jazz scene of the '50s where he studied flute at Wayne State University. Lateef began recording as a leader in 1955 for Savoy (and later Riverside and Prestige) although he did not move to New York until 1959. By then he already had a strong reputation for his versatility and for his willingness to utilize "miscellaneous instruments." Lateef played with Charles Mingus in 1960, gigged with Donald Byrd, and was well-featured with the Cannonball Adderley Sextet (1962-1964). As a leader, his string of Impulse! recordings (1963-1966) was among the finest of his career, although Lateef's varied Atlantic sessions (1967-1976) also had some strong moments. He spent some time in the '80s teaching in Nigeria.

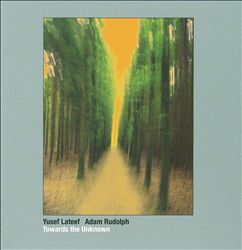

His Atlantic records of the late '80s were closer to mood music (or new age) than jazz, but in the '90s (for his own YAL label) Lateef recorded a wide variety of music (all originals) including some strong improvised music with the likes of Ricky Ford, Archie Shepp, and Von Freeman. Lateef remained active as a composer, improviser, and educator (teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst) into the 21st century, performing and recording as a leader and collaborator on such noteworthy recordings as Towards the Unknown with composer/percussionist Adam Rudolph (released in 2010, the same year Lateef was recognized as a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts). Yusef Lateef died at his home in Shutesbury, Massachusetts in December 2013; he was 93 years old.

Yusef Lateef

Renaissance man Dr. Yusef Lateef was born William Emanuel Huddleston in Chattanooga, Tennessee on October 9th, 1920. At the age of 5 he moved with his family to Detroit. Growing up in Detroit he came in contact and forged friendships with many a giant of jazz such as Kenny Burrell, Milt Jackson, Tommy Flanagan, Barry Harris, Paul Chambers, and Donald Byrd. By the time he graduated from high school he was a proficient tenor saxophonist. He started soon after graduation playing professionally and touring with different swing orchestras among them those of Hot Lips Page, Roy Eldridge and Lucky Millender. In 1949 he joined Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra (using the stage name William Evans), and stayed with them for one year. In 1950 he returned to Detroit and to enrolled in the Wayne State University’s Music Department and studying composition and flute. During his tenure at Wayne State he converted to Islam and changed his name to Yusef Lateef. He stayed in Detroit until 1960 and during this decade he led his own quintet for a while, recorded his first album as a leader for the Savoy label, Stable Mates, and furthered his musical education by studying oboe with Ronald Odemark of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

In 1960 he returned to New York and enrolled in the Manhattan School of Music to further his studies in flute and music education. Over the next 10 years he recorded several records as a leader and played on many more under other musicians’ leadership, toured with Charles Mingus, Cannonball Adderley, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and Babatunde Olatunji and obtained a BA in music and a MA in music education. Among the highlights of his recording career from this decade are Eastern Sounds, Live at Pep’s and The Golden Flute. One can already hear on these records the incorporation of different eastern musical influences into the more straight-ahead jazz idiom. These albums also are one of the first places one can hear Dr Lateef play different reed instruments including the bassoon, bamboo flute, shanai, shofar, argol, sarewa, and taiwan koto. During the 70s he taught courses in autophysiopsychic music (which comes from one’s spiritual, physical and emotional self) at the music theory department in the Manhattan School of Music. From 1972 till 1976, he was an associate professor of music at the Borough of Manhattan Community College.

In 1975 he was awarded a Ph.D. in Education from University of Massachusetts in Amherst, MA and he continues to be a professor there. Suite 16 or Blues Suite, Dr. Lateef’s first work for large orchestra, premiered in 1969 at the Georgia Symphony Orchestra in Augusta and it was performed in 1970 by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra at the Meadowbrook Music Festival, and recorded by the WDR Orchestra in Cologne. The NDR Radio Orchestra of Hamburg commissioned him to compose the tone poem “Lalit,” in 1974. He also recorded his Symphony No.1 with the same orchestra later that year. He has toured the world with his ensembles and other musicians performing in concert halls and music festivals.

The recorded highlight of this stage of his career is Autophysiopsychic. In the 80s Dr. Lateef spent 4 years at the Center for Nigerian Cultural Studies at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria researching the Fulani flute. In 1987 he won a Grammy for Yusef Lateef’s Little Symphony.

In 1992 he established his own label YAL. In 1993 Yusef Lateef’ composed his most ambitious work to date, The African American Epic Suite, a four-movement work for quintet and orchestra dedicated to 400 years of African American history. It premiered with the WDR orchestra and later was also performed by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Among his lesser known accomplishments are 3 works of fiction; A Night in the Garden of Love and two collections of short stories, Spheres and Rain Shapes.

Dr. Lateef continues to perform, record and expand the boundaries of music.

Yusef Lateef, Innovative Jazz Saxophonist and Flutist, Dies at 93

December 24, 2013

Yusef Lateef, a jazz saxophonist and flutist who spent his career crossing musical boundaries, died on Monday at his home in Shutesbury, Mass., near Amherst. He was 93.

His death was announced on his website.

Mr. Lateef started out as a tenor saxophonist with a big tone and a bluesy style, not significantly more or less talented than numerous other saxophonists in the crowded jazz scene of the 1940s. He served a conventional jazz apprenticeship, working in the bands of Lucky Millinder, Dizzy Gillespie and others. But by the time he made his first records as a leader, in 1957, he had begun establishing a reputation as a decidedly unconventional musician.

He began expanding his instrumental palette by doubling on flute, by no means a common jazz instrument in those years. He later added oboe, bassoon and non-Western wind instruments like the shehnai and arghul. “My attempts to experiment with new instruments grew out of the monotony of hearing the same old sounds played by the same old horns,” he once told DownBeat magazine. “When I looked into those other cultures, I found that good instruments existed there.”

Those experiments led to an embrace of new influences. At a time when jazz musicians in the United States rarely sought inspiration any farther geographically than Latin America, Mr. Lateef looked well beyond the Western Hemisphere. Anticipating the cross-cultural fusions of later decades, he flavored his music with scales, drones and percussion effects borrowed from Asia and the Middle East. He played world music before world music had a name.

In later years he incorporated elements of contemporary concert music and composed symphonic and chamber works. African influences became more noticeable in his music when he spent four years studying and teaching in Nigeria in the early 1980s.

Mr. Lateef professed to find the word “jazz” limiting and degrading; he preferred “autophysiopsychic music,” a term he invented. He further distanced himself from the jazz mainstream in 1980 when he declared that he would no longer perform any place where alcohol was served. “Too much blood, sweat and tears have been spilled creating this music to play it where people are smoking, drinking and talking,” he explained to The Boston Globe in 1999.

Still, with its emphasis on melodic improvisation and rhythmic immediacy, his music was always recognizably jazz at its core. And as far afield as his music might roam, his repertoire usually included at least a few Tin Pan Alley standards and, especially, plenty of blues.

He was born on Oct. 9, 1920, in Chattanooga, Tenn. Many sources give his birth name as William Evans, the name under which he performed and recorded before converting to Islam in the late 1940s (he belonged to the reformist Ahmadiyya Muslim Community) and changing his name to Yusef Abdul Lateef. But according to Mr. Lateef’s website, he was born William Emanuel Huddleston.

When he was 5 his family moved to Detroit, where he went on to study saxophone at Miller High School. After spending most of the 1940s on the road as a sideman with various big bands, he returned to Detroit in 1950 to care for his ailing wife and ended up staying for a decade.

While in Detroit he became a popular and respected fixture on the local nightclub scene and a mentor to younger musicians. He also resumed his studies, taking courses in flute and composition at Wayne State University and later studying oboe as well.

In the later part of the decade he began traveling regularly from Detroit to the East Coast with his working band to record for the Savoy and Prestige labels. By 1960 he had settled in New York, where he worked with Charles Mingus, Cannonball Adderley and the Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji before forming his own quartet in 1964.

He was soon a bona fide jazz star, with successful albums on the Impulse and Atlantic labels and a busy touring schedule. But he also remained a student, and he eventually became a teacher as well.

He received a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from the Manhattan School of Music, and taught both there and at Borough of Manhattan Community College in the 1970s. He earned a doctorate in education from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in 1975 (his dissertation: “An Overview of Western and Islamic Education”) and later taught there and elsewhere in New England.

The more he studied, the more ambitious Mr. Lateef grew as a composer. He recorded his seven-movement “Symphonic Blues Suite” in 1970 and his “African-American Epic Suite,” a four-part work for quintet and orchestra, two decades later. His album “Yusef Lateef’s Little Symphony,” on which he played all the instruments via overdubbing, won a Grammy Award in 1988, though not in any of the jazz or classical categories; it was named best New Age performance. Mr. Lateef said at the time that, while he was grateful for the award, he didn’t know what New Age music was.

In 2010 he was named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Mr. Lateef is survived by his wife, Ayesha; a son, Yusef; a granddaughter; and several great-grandchildren. His first wife, Tahira, died before him, as did a son and a daughter.

His creative output was not limited to music. He painted, wrote poetry and published several books of fiction. He also ran his own record company, YAL, which he established in 1992.

He remained musically active until a few months before his death. In April he appeared at Roulette in Brooklyn in a program titled “Yusef Lateef: Celebrating 75 Years of Music,” performing with the percussionist Adam Rudolph and presenting the premieres of two works, one for string quartet and the other for piano.

A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 25, 2013, Section A, Page 21 of the New York edition with the headline: Yusef Lateef, Innovative Jazz Musician, Is Dead at 93. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

Always Something New—Remembering Yusef Lateef (1920-2013)

Anyone reading this most likely already knows about the unique and deep beauty of Yusef Lateef’s sound. As with all the great musicians, we can recognize him upon hearing the first note. Yusef always said, “The tradition is to have your own sound.” And in fact the Dogon people of Mali have a word, “mi”, which describes the inner spirit of a person expressed though the voice of a musical instrument. When we hear Yusef play, we hear him always playing from the heart. I have witnessed both audience and performers moved to tears by his flute playing. I have heard Yusef play the entire history of the tenor saxophone in one solo. Always the story was deep, more than nine decades of life experience coming through—clear and beautiful. Look and listen: imagination, knowledge, and heartfelt expression are the guiding principles of real freedom.

Yusef Lateef in 2002. Photo by Kevin Ramos, courtesy Adam Rudolph.

I first met Brother Yusef in the summer of 1988 when I was living in Don Cherry’s loft on Long Island City, New York. We rehearsed there for a concert of Yusef’s with our group Eternal Wind (myself on hand drums and percussion, Charles Moore, Ralph Jones and Federico Ramos) plus Cecil McBee on bass. I was honored when Yusef asked me to bring my compositions for us to perform; in rehearsal he approached them with real interest and respect. That concert, produced by the World Music Institute, took place at Symphony Space in New York. Yusef had written all new music specifically for the occasion. I realize now that this was how he worked: every performance he did was always all new music. In the ensuing 25 years, Yusef and I performed and collaborated worldwide in many contexts: quartets, octets, with orchestras, and, most often in the last two decades, as a duo. He always brought new music and new creative processes and concepts to each concert and recording date. Yusef said, “With each project I try to do something I have never done before.” I have often reflected upon this; one of many seeds of wisdom that Yusef generously shared. For me, it suggests the idea of three qualities that I value deeply and which I saw Yusef embody in his life and work: creative imagination, studiousness and courage. A couple of personal experiences come to mind that illustrate these characteristics.

In 1995, when Yusef and I were discussing how to approach our second compositional collaboration The World at Peace for 12 musicians, Yusef suggested that for two of the movements I write for half of the instruments, telling him only which instruments I had written for, the tempo and how many bars it was. He would then compose, without seeing my music, for the other six musicians. At the same time, he would compose two other pieces, sending me only which six instruments he had chosen, the tempo and how many bars. So it also became my task to compose for the other six musicians without having seen what he had written. This seemed to me a brilliant and original idea. When we heard the combined music’s in rehearsal, we decided that three out of the four compositions worked, in that they sounded unlike any music we had ever heard before, while serving our expressive intentions.

Adam Rudolph and Yusef Lateef in 1996

Several years later, Yusef was asked by the Interpretations series to create an evening of music to celebrate his 80th year in a concert at Alice Tully Hall. In addition to asking me to compose some new music for this octet project, Yusef’s new idea was that we co-compose several pieces in a formula of writing alternating bars for the entire ensemble. For example, I would write the first five bars, he would write the next nine bars, I would write the next seven, and so on. The results were surprising, fresh and beautiful, and worthy of inclusion in the concert and the subsequent recording. On both of these occasions, I was inspired by Yusef’s courage and willingness to try completely new and unproven processes even in a major concert setting. And as I reflect upon it now, I wonder – how did Yusef think of these ideas in the first place? Yusef seemed to have no bottom to his wellspring of creative ideas, as anyone who has worked with him will attest.

The first recording I heard of Yusef’s was one of his early forays into an expanded western “classical” orchestration. As a fourteen-year-old growing up on the south side of Chicago, I was excited to be discovering both live and recorded music. I often raided my father’s vast record collection. The Centaur and the Phoenix thus found a regular rotation on my turntable and it still sounds fresh today. When I once asked Yusef about that recording, he told me he wanted to move beyond the codified instrumentation and harmonic materials prevalent at that time and “try something new.”

This amazing inventiveness seems to have always been in Yusef’s character. In the mid-1950s, he was one of the first improvising artists to embrace Middle Eastern and Eastern modes, rhythms, and instruments into his music. When asked about this, he told me that he wanted to have a long career creating music and to do so he would have to study as much about all kinds of music as possible in order to be able to vary his musical palette. Again, words to live by for the serious musician.

Yusef’s art traveled in higher dimensions, transcending medium or style. His telescope of intuition ranged far into deep space, towards new galaxies of thought and musical processes. He often referred to us as “musical evolutionists.” In speaking about his process he said: “When you get rid of one thing you have to replace it with something else.” As I see it, this means first having the courage to abandon something one may have invested years in developing. (In Yusef’s case, that was the harmonic structures that he and Barry Harris refined throughout the 1950s.) Then one must have the imagination to think of a genuinely new approach rooted in a foundation of musical substance and experience. This is no small task. Yusef’s amazingly diverse and inventive musical output of his last 25 years is testimony to his words. In 1985, following his return from four years of teaching, studying and performing in Nigeria, Yusef embarked on a new phase of his creative life. The way Yusef’s music opened up and expanded reminds me of his good friend and fellow evolutionist John Coltrane’s last years. In fact Yusef often quoted one of Coltrane’s favorite sayings: “Knowledge will set you free.”

As I see it, Yusef was a prototype of the modern renaissance artist. He refused to let any outside force define him or his activities. In addition to his compositions that have become central to the contemporary improvisers repertoire of “standards,” Yusef composed dozens of pieces for piano, chamber groups, choirs, and orchestras. He invented and built new musical instruments, carved bamboo flutes, taught scores of students, and published dozens of musical pedagogical studies (of which The Repository of Musical Scales and Patterns stands as one of the most important music reference books of the last 50 years). And this creative outpouring was not limited to music alone. In addition to earning his Doctorate in Education, Yusef painted and wrote two novels, Night in the Garden of Love and Another Avenue (which he made into an opera). He wrote several books of poetry, plays, and numerous articles on subjects ranging from Lester Young and Charlie Parker to Confucius and Martin Buber.

In 1992 Yusef started YAL records, which released over 36 recordings of what he called “Autophysiopsychic” music. He used this term to describe his music, which means “music coming from the physical, spiritual and mental self.” Over the years Yusef asked me to contribute my percussion, electronics, and arrangements to 18 of these recordings. He inspired me to start my own Meta records label and our two labels co-released several collaborative projects including Voice Prints (2013), Towards the Unknown (2010), In the Garden (2003), Beyond the Sky (2001) and The World at Peace (1997). Yusef was a great motivator: he made me aspire to realize my own creative potential. This is a gift I believe he has given to many.

Yusef, like all great artists, was never afraid of what others thought. He dedicated himself to following his own muse, cultivating his imagination with lifelong study and fearless experimentation. Although Yusef’s music had deep roots, he never wanted to recreate his past music. He always chose to make music that expressed what interested him in the present moment in his life. In 2010, when Yusef was awarded the NEA “Jazz Masters” award, they asked him to perform one of his older pieces with the Lincoln Center Big Band at the ceremony. Yusef informed them that his older music was not “where he was at” creatively any more. I was honored when a few days later he called and asked me to perform in duet with him for his portion of the evening’s events. The night of the awards Yusef and I stepped on stage following a rousing piece played by the Lincoln Center Big Band. After some moments of silence Yusef blew a solitary note on his bamboo flute. You could hear a pin drop—Yusef had (yet again) brought magic into the house. We continued with Tibetan bells, then moved to the blues via tenor saxophone and hand drums (accompanied by an electronic music tape that Yusef had created), then on into our piano and flute duet. Finally I played the didgeridoo while Yusef sang his rendition of the slave song “Brother Hold Your Light” (I want to get to the other side). Perhaps there had been some in attendance who initially wished to hear Yusef go back and revisit his music of the past. But Yusef wanted to present the person he was, who we were, at that place, at that time—in the moment of the now. Yusef received the standing ovation he richly deserved by an audience that included many of his peers. It was a great evening, and one I shall never forget.

In the fall of 2012 we did our last European tour around Yusef’s 92nd birthday, and in April of 2013 we played our last duet concert at Roulette in New York. Both in his playing and composing Brother Yusef continued to stay creative up to the very end. Only days before his passing he told me about new intervallic ideas he was developing. He sent his fourth symphony to the copyist only a couple months ago. This past October Yusef brought his sound and spirit to a concert of Go: Organic Orchestra at the Athenaeum in Hartford. It was his last public performance.

Brother Yusef will continue to be an inspiration to many of us. I consider him to be my most important teacher, not only of music, but also of how to live as an artist and a human being. Over the years he became a true and dear friend. Anyone who spent time with Brother Yusef will testify to his kind and gentle nature. He radiated peace and love. He was a luminous being. To put it another way, as Yusef himself said recently, “Brother Adam, have you noticed the leaves waving to you? It’s okay to wave back.”

December 24, 2013

Deadline Detroit

September 7, 2018

Vinyl Factory

A formative influence on John Coltrane’s modal-jazz experiments in the late 1950s and on the astral-jazz style associated with Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane a decade later, tenor saxophonist and multi-reed player Yusef Lateef was never a fully paid-up member of either movement. Instead he followed his own idiosyncratic path, switching directions several times. Chris May picks 10 essential records from Lateef’s five-decade catalogue.

Brought up in Detroit, where he lived until moving to New York in the late 1950s, Yusef Lateef’s early years as a professional musician were spent in the city’s cheek-by-jowl jazz and R&B worlds. While still based in Detroit, he was among the first musicians to embrace Middle Eastern and Asian instruments, and the harmolodic motifs which were important features of his recordings from 1957 onwards. In the early 1960s, he was a member of the Cannonball Adderley Sextet alongside Joe Zawinul, and so was part of some of the earliest stirrings of jazz fusion. From 1968 to 1976, Lateef recorded exclusively for Atlantic, where he made a series of albums which brought his Detroit soul roots prominently back into the mix.

Lateef continued to make compelling albums into the 1980s, but his work became less interesting after the formation of his own label, YAL, in 1992. After a couple of strong co-headlining projects with Archie Shepp and Von Freeman – neither of them yet available on vinyl – Lateef changed focus to new-age music and released a profusion of self-produced and curiously bland albums.

But between 1957 and the mid 1980s, Lateef recorded some of the most characterful and culturally outward-facing albums in the jazz repertory. Here are 10 of the best.

Yusef Lateef

Jazz Mood

(Savoy LP, 1957)

In 1957, Lateef was taking jazz into “exotic” cultural orbits that would only be more widely explored after Pharoah Sanders’ Tauhid caught the wave in 1967. On Jazz Mood, Lateef plays the Egyptian argol as well as tenor saxophone and flute, Ernie Farrow (Alice Coltrane’s big brother) plays the Afghani rabat and double bass, and trombonist Curtis Fuller gets nimble with the Turkish finger cymbals. Intimations of astral jazz were definitely in the studio the day the album was recorded.

Yusef Lateef

Other Sounds

(New Jazz LP, 1959)

Another entrancing astral-jazz precursor. Produced in 1957 by Prestige’s Bob Weinstock, Other Sounds went unreleased until the expiry of Lateef’s Savoy contract in 1959, when it came out on Prestige subsidiary New Jazz. Ernie Farrow is back on bass and rabat, pianist Hugh Lawson takes over on finger cymbals, and Lateef again plays tenor sax, flute and argol. New drummer Oliver Jackson doubles on earth-board.

Yusef Lateef

The Centaur And The Phoenix

(Riverside LP, 1960)

On The Centaur And The Phoenix, Lateef continued to explore music from the East, but also dips into the European classical tradition with the angular, Stravinsky-esque title track and the sublimely lyrical ‘Summer Song’. Both were adapted by composer Charles Mills from his symphonic scores. Fellow Cannonball Adderley sideman Joe Zawinul is on piano. Another significant contributor, and portent of the future, is Kenny Barron, who arranged two tracks. As keyboard player, composer and arranger, Barron would play a key role on Lateef’s Atlantic albums in the mid 1970s.

Yusef Lateef

Eastern Sounds

(Moodsville LP, 1961)

Lateef’s best known album has merits but also shortcomings – and while Eastern Sounds includes some beautiful tunes, Lateef’s arrangements often seem to play safe. The clue is in the name of the label. Moodsville was launched by Prestige boss Bob Weinstock as a subsidiary label dealing in “mood music”, a genre which makes exotica sound like P-Funk. Only the muscular tenor work-out ‘Snafu’ is prime Lateef. Collectable for its significance in Lateef’s career, as much as for its content.

Curtis Fuller

Boss Of The Soul-Stream Trombone

(Warwick LP, 1961)

One of a handful of unreconstructed hard-bop albums released by the shortlived New York indie Warwick, whose major earner and primary focus was Johnny & The Hurricanes. On Boss Of The Soul-Stream Trombone, Lateef is reunited with Jazz Mood’s Curtis Fuller. Ostensibly a Fuller album, the main soloists are actually Lateef and the up and coming Freddie Hubbard, both on busting form. The record was later reissued under Hubbard’s name as Getting’ It Together.

Yusef Lateef

Live At Pep’s

(Impulse! LP, 1965)

Lateef recorded half a dozen albums for Impulse! between 1964 and 1966. All of them – including this club performance in Philadelphia – were immaculately produced by John Coltrane’s producer, Bob Thiele, and engineered by Rudy Van Gelder. For Live At Pep’s, Lateef’s regular quartet was expanded to include trumpeter Richard Williams, a featured soloist on Oliver Nelson’s ‘Screamin’ The Blues’. Lateef turns in a visceral set which includes R&B standard ‘See See Rider’ – played on oboe.

Yusef Lateef

The Blue Yusef Lateef

(Atlantic LP, 1968)

The first of ten, mostly stonkingly good soul-jazz albums Lateef released on Atlantic between 1968 and 1976, all made with R&B producer Joel Dorn and showcasing Lateef’s Detroit soul as well as jazz roots. The series was controversial – jazz purists hated the backbeats and bass ostinatos, and, on The Blue Yusef Lateef, the inclusion of vocal group the Sweet Inspirations (featuring Cissy Houston, shortly before she went solo). Lateef adds the Indian tambura and Japanese koto to his instrumental repertoire. The drummer is the magnificent Roy Brooks, whose The Free Slave on Muse in 1972 is a stellar first-wave spiritual-jazz album.

Yusef Lateef

The Doctor Is In…And Out

(Atlantic LP, 1976)

Roy Brooks lived with mental health issues for most of his life, and when The Doctor Is In…And Out was recorded he was temporarily out of action. But the new rhythm section – including Miles Davis alumni Ron Carter on bass, Al Foster on drums and Weather Report’s Dom Um Romao on percussion – is irresistible. Since 1972, Lateef’s Atlantic bands had included keyboard player Kenny Barron (from The Centaur And The Phoenix), who composed and arranged half the tracks here. The highlight, however, is Lateef’s deep-pocket opener, ‘The Improvisers’.

Yusef Lateef

In A Temple Garden

(CTI LP, 1979)

After setting up Impulse! and supervising John Coltrane’s label debut Africa/Brass, producer Creed Taylor left for more mainstream territory. After a spell at Verve he founded CTI, specialising in lushly orchestrated and lavishly-produced crossover music. Lateef’s In A Temple Garden band includes top fusion players Randy and Michael Brecker on trumpet and tenor saxophone, Eric Gale on guitar, Jeremy Wall on keyboards and Steve Gadd on drums. You either love the CTI sound or loathe it, there is no middle ground.

Yusef Lateef

In Nigeria

(Landmark LP, 1985)

From 1983 to 1986, Lateef lived in northern Nigeria, teaching jazz at Ahmadu Bella University and immersing himself in traditional Yoruba and Hausa music. He made two albums with local drum and percussion groups – In Nigeria, for Riverside founder Orrin Keepnews’ Landmark label, and Hikima (Creativity), released by the university’s Centre for Nigerian Cultural Studies. Hikima is as good as impossible to find. In Nigeria turns up occasionally. Both should be seized on sight.

January 3, 2014

Several African-American musicians took Muslim names in the 1960s.Yet few lived up to them with the conviction of Yusef Lateef, who was originally born William Emanuel Huddleston in Chattanooga, Tennessee but assumed his familiar moniker, which means ‘the gentle one’ in Arabic, when he embraced Islam in Detroit in the 1950s.

Those fortunate enough to have met Lateef will vouch for his overwhelming humility and generosity of spirit. Several years ago, when he was honoured by the Danish Jazz Federation for his lifetime’s work he shed a tear at the memory of his dear friend Ben Webster rather than dwell too greatly on his own achievements.

There were many. More than any other artist Lateef brought the sounds of the universe to improvised music, and his introduction of a plethora of Asian and Middle Eastern reed and percussion instruments greatly enriched the sound canvas of the basic piano-horns ensemble.

Lateef’s championing of woodwinds associated with classical music, bassoon and oboe, stemmed from an irrepressible desire to see beyond genre, as he pursued the ideal of a musical Esperanto in which non-western scales and modes provided a platform for composition and improvisation. Landmark albums cut between the early 1960s and late 1990s – The Centaur And The Phoenix, Eastern Sounds, Into Something, The World At Peace – revealed a multi-instrumentalist intent on exploring robust overtones and esoteric timbres.

Yet Lateef never lost faith in the blues, and his swooning, swing-style tenor saxophone was supplemented by a sensual, charged singing voice that could warm the hearts of any gathering of lost souls. The world, as well as America, has lost a truly original adventurer in sound.

– Kevin Le Gendre

Beyond category: Remembering Yusef Lateef

Reminiscences

Volume 114, No. 2February, 2014

Yusef Lateef, 93, the saxophonist, multi-reed player and flutist, died on Dec. 23. He had been a Local 802 member since 1960. Below, jazz writer Peter Zimmerman remembers Lateef’s versatility, which was really beyond category.

Last July, when I spoke with Yusef Lateef at his home in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, I was surprised to hear the retired UMass professor say that he didn’t consider himself to be a jazz musician. Instead, he referred to his music as “autophysiopsychic.”

He won his only Grammy in the New Age category, for “Yusef Lateef’s Little Symphony,” which Billboard described as “an atmospheric four-movement classical/jazz composition.” On the album, Dr. Lateef played all the instruments, including tenor sax, alto, tenor and soprano flutes, water drums, gourd, kalangu, casio, sitar, shannie, and Ensoniq Mirage, a sampler-synth.

However you want to label him, few would dispute that many of Dr. Lateef’s albums from the late 1950s and 60s – dozens of them, including “The Golden Flute” – could be categorized as jazz. And this is not to mention his work with the seminal Dizzy Gillespie big band of the late 1940s (allegedly, that’s his solo on “Hey Pete! Let’s Eat More Meat”).

Dr. Lateef, who converted to Islam (the Ahmadiyya sect) in 1948, described autophysiopsychic as “music from the physical, the mental, and the spiritual – and from the heart.” He told me that Lester Young personified this type of music. Dr. Lateef spent eight years teaching in Nigeria, where he studied a type of flute called the serewa, described as the “soul of nightlife.” He spent his life collecting instruments from around the world. “I look for them,” he said, “and some of them are given to me.”

I asked him what he thinks about labeling music. He replied that people are free to call it what they like, but he added, “If Picasso named a painting ‘The Bull Fight,’ I wouldn’t call it ‘The Kitty Cat.’”

Dr. Lateef was a 2010 recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts award. Herb Boyd’s biography of him, called “The Gentle Giant” (his nickname), was published in 2006.

Mr. Lateef is survived by his wife, Ayesha; a son, Yusef; a granddaughter; and several great-grandchildren.

100 Reasons We Love Yusef Lateef for His 100th Birthday

Early in college, the alto saxophonist Darius Jones checked out a VHS of Cannonball Adderley from the library. As he watched the European concert, one of Adderley’s sidemen struck him as peculiar.

“He was standing next to this other guy who looked like a professor or something,” Jones tells Discogs. “I had never seen a Black man like that in my whole life. The sight of him was just unusual. I was like, ‘Is that real?’”

It wasn’t a mirage; it was the improviser, composer, and multi-reedist Yusef Lateef, playing the blues on an oboe. Jones was in for a lifelong ride.

At first, when Jones tried to get into Lateef, his body of work flummoxed him. Lateef not only played tenor saxophone but also indigenous instruments from far-flung lands: flute, oboe, shehnai, shofar, koto. “There are certain albums that were weird; I didn’t know what was happening,” Jones says. “Like, ‘Why isn’t he playing the saxophone? Why is he playing flute on this record?’ Now, I realize that in my pursuit of freedom, I was looking at the freest person.” Today, Jones is emotional when discussing Lateef, who died at age 93 in 2013.

“He changed my view of Blackness,” explains Jones, who himself is Black. “He helped evolve and grow it. He helped me not look at it so narrowly. He helped me get past spaces of ignorance and not only open my ears and my mind, but my heart to new perspectives and paths.”

Lateef’s 80-plus record discography is the work of a complete artist — a global citizen, a curious mind, a gentle soul. He played “world music” decades before it was a bankable idea. Dip in at random, and you might hear funk, ambient, neoclassical, sound collage, or post-bop. But the gentle giant, who would have turned 100 years old this Friday (October 9), was about more than just his records; he had a transformative effect on people.

“I was a young guy. I had natural, raw talent, but I didn’t have any direction in how to have a musical life,” the tenor giant Sonny Rollins tells Discogs about meeting Lateef early on. “Yusef exemplified all of that to me and sent me on the right track. He was my mentor in so many ways. He had such a good life, and he was inspirational to so many players as a musician and human being.”

Lateef was born William Emanuel Huddleston in Chattanooga, Tennessee. In 1925, when he was four, his family moved to the music-filled Paradise Valley neighborhood in Detroit. There, he adopted his father’s chosen surname and became Bill Evans. As Mark Stryker writes in 2019’s Jazz From Detroit, he grew up soaking up the sounds of the city, which is a music hub due to its vibrant Black communities and exceptional music programs in its public schools.

Huddleston attended Miller High School with future greats like the vibraphonist Milt Jackson. In his late teens, influenced by the Alpha and Omega of the tenor saxophone, Coleman Hawkins, and Lester Young, he took up the instrument himself. In 1948, he converted to Islam, and soon after, he joined Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra and took the name Yusef Abdul Lateef. “Being a member of Dizzy’s band for two years was like attending a top-flight musical academy,” Lateef wrote in 2006’s The Gentle Giant: The Autobiography of Yusef Lateef.

In the early 1950s, Lateef worked on a Chrysler assembly line while gigging around town. One day, a Syrian co-worker showed him the Islamic rabab. “He told me that King David, who is mentioned in the Bible, played the [rabab] during his prayers more than 5,000 years ago,” he wrote in his autobiography. From there, he sought out the argol, a double-reed bamboo flute, and the rest, as they say, is history.

In honor of his centenary, Discogs spoke to 14 musicians and authors — some lifelong friends and colleagues, some students he taught, others merely admirers. As you’ll find in the following expressions, those three categories blurred together more often than not. Here are 100 reasons we love Yusef Lateef on his 100th birthday.

1. He embraced indigenous instruments.

Jeff Coffin (multi-reeds): He wasn’t just playing ding-ding-ding, a swing pattern. He explored multiple cultures of music.

Mark Stryker (author): I think there’s no question that his study of Islam broadened his worldview. It opened him up to interest in cultures worldwide — particularly the Middle East and the Near East.

Ralph “Buzzy” Jones (multi-reeds): Back in the 1950s, he had a vast array of indigenous instruments he would play and incorporate in his performances.

Do Yeon Kim (gayageum): Before I moved to America, I Googled “world music” and I found Yusef immediately. I loved the exotic melodies and atmosphere in his music.

Adam Rudolph (percussion): In improvised music, he was one of the first musicians — if not the first — to explore music from other cultures.

Sonny Rollins (tenor sax): He used to make these bamboo flutes.

Herb Boyd (author): He made me a bamboo flute. I’ve got three of them here!

Louis Hayes (drums): Listening to Yusef’s playing on the oboe, wooden flute, and other instruments, I’m very happy that it was recorded.

2. He wasn’t a cultural tourist; he was a pioneer.

R. Jones: He had a valid reason for this. He said it was like going into a buffet. You want to try different things. You want to try different modes of expression.

Stryker: He gravitated toward these instruments, put them within a cultural context, and explored them because they were seeding into his larger understanding of the world.

3. He approached unfamiliar musical traditions respectfully.

Rudolph: He wasn’t so much looking for the other-ness in music, like “This is music from another place.” It was about expanding his palette and his conceptual and process base.

Stryker: He mastered the instrument, but he also learned a broader understanding of the culture around it, which is one of the things that gave him so much depth.

4. And he drew from Western forms skillfully.

Rudolph: His study of Western 20th-century harmonies, starting the 1950s, expanded the resources of inspiration for improvisational musicians.

5. He was against the word “jazz.”

Rudolph: Yusef did not consider himself a jazz musician.

R. Jones: Many musicians were very critical of the terms that were, as John Coltrane said, “foisted” on us. They did not embrace the word “jazz.”

Rudolph: He wanted to feel free, and he did feel free to move to wherever his creative imagination could take him.

R. Jones: We didn’t want to be in a box. We always felt that our music would transcend the characteristics of these labels that were put on us.

6. He coined a new genre.

Rudolph: He called his music “autophysiopsychic.”

7. With it, he took on the dictionary.

Rudolph: He gave a whole lecture at UCLA about it once. He had all the authors of the dictionary sitting around and defining it. Webster’s dictionary defined it as adultery and fornication, and Yusef said, “I don’t know what that has to do with my music.” Then he’d reply to them by playing his saxophone. It was an incredible lecture.

8. But that word encompasses the human experience.

Rudolph: It means music coming from one’s mental, physical, and spiritual self.

R. Jones: Through the particular evolution of autophysiopsychic music, Yusef has mentored and inspired me mentally, physically, and spiritually.

9. On tenor saxophone, he was a force of nature.

Dave Liebman (multi-reeds): He had an old-school, big sound. He had one of the biggest tenor sounds of the ‘60s.

Coffin: He knocked me out. I loved his writing. I loved his expression. I loved his tone.

James Brandon Lewis (tenor sax): That big sound, that tenor sound. When I hear him, I hear that sound.

Stryker: He’s putting so much air and life-force into the horn. He gets these tone manipulations — the low barking register, the overtone.

Lewis: I dig a more open sound, in terms of what’s informing your oral cavity. Suppose it’s an o sound, an e sound, or an ah. He had an open sound similar to Sonny Rollins and Jimmy Heath.

10. He was up there with the greats of the instrument.

Lewis: I would put his tenor sound with many different sounds I preferably like on tenor: John Coltrane, Gene Ammons, Sonny Rollins, David S. Ware.

11. Exhibit A: Into Something.

Stryker: I have a real fondness for the record Into Something, which he recorded in 1961 for Riverside with an all-Detroit band — Barry Harris on piano, Herman Wright on bass, Elvin Jones on drums. Half of the record is a quartet with piano. Half of it is a trio. The sound that Yusef gets on tenor is so big and roomy.

12. He didn’t need to be flashy to make a point.

Stryker: He’s not flying through the changes like, let’s say, Sonny Rollins would, but he’s making a statement.

Boyd: He had his own style in terms of overblowing and playing vibrato. He could play speedier-tempo things as well, but he was a bit slower.

Stryker: When you’re young, you get dazzled by people who have a lot of technique and can play the hell out of chord changes and have a certain kind of flash to them. But when you get older, you begin to listen a little deeper to someone like Yusef.

Liebman: He didn’t run a lot. You know, using your fingers and playing fast. He didn’t do that. He was very slow and methodical.

Kim: My favorite Dr. Lateef recording was a live performance with Ahmad Jamal at the Olympia in 2012. I love how they support, respect, and listen to each other; their synergy is great. Ahmad provided a lot of space for Dr. Lateef to explore, and backed him so gracefully. This attitude can only happen when musicians really trust each other. I love that so much.

13. He rooted himself in the blues.

Barry Harris (piano): To me, he was the greatest blues tenor player in the whole world. I would hate to see any cat — Sonny Stitt, any of them — go up against Yusef, playing some blues. They could just forget it.

Liebman: He was very blues-oriented. He comes from that tradition in which you had to play the blues. You had to find some kind of way of doing it that was convincing.

Stryker: The sound of his tenor was so deep and rich and expressive, and so rooted in the blues.

Harris: He made me so mad, man! I’d say, “You’re the greatest blues player and you won’t play the blues no more! You’re going all Eastern on me!” We had a falling-out about this, but that was the way it was.

14. He wrote the book on music theory.

Liebman: He wrote one of the best books on music called The Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns. It’s a big, thick repository of scales, intervals, and tunes.

Lewis: That book kept me sane and motivated to continue to push and strive.

Glenn Siegel (jazz advocate, concert producer): So many musicians refer to that as a bible.

Coffin: He’s giving us scales and interpolations of those scales from different cultures from around the world.

Liebman: You can turn anywhere in that book, and you can get something out of it, even if only for sight-reading. Any page will knock you out.

15. And he wrote it for everybody.

Rudolph: Don Cherry, Muhal Richard Abrams, Ornette Coleman, all the elders who I had the privilege to be around, they all said it one way or the other: Music doesn’t belong to anybody.

Siegel: He could have written that for an academic journal, and it could have sat on a shelf somewhere, but he wrote it with the intention of musicians using it. And a lot of people use it.

Rudolph: It filters down, and whatever you’re able to hold in your cup, it’s there to be shared. That’s how the music stays alive.

16. He was sincere in all his pursuits.

Rollins: His desire to learn, to study and research, was an inspiration to me.

Coffin: Authenticity was important to him. He was very authentic in his pursuits.

Rudolph: The more he could learn about other kinds of music, it continued to keep him energized and expanded and inspired.

17. He usually mastered what he learned.

Boyd: He had every kind of musical instrument you could think of around his house. A lot of people have instruments, but they don’t know how to play them. They can get a sound out of them, and that’s the extent of it. He more than “got” the sound — he got the full expression out of each particular instrument.

18. He was a universalist.

Boyd: The universality he brought to his music is one thing that makes him unique among all those people coming out of Detroit.

19. He was decades ahead of his time.

Kim: Non-Western instruments have different tunings, which can sound dissonant or uncomfortable to Western music listeners. However, Yusef boldly used non-Western tunings for texture and color.

Coffin: He was into world music in the ‘50s, well before Coltrane got into Indian music and that kind of thing.

Boyd: He was into world music long before they called it world music.

20. He could play one note memorably.

Stryker: He was the kind of player that could play just a couple of notes or one long note and carry an incredible load of meaning.

21. He sometimes played straighter than one might think.

Darius Jones (alto sax): There are times where he’s just making straight R&B music!

22. But his body of work spans musique concrète.

Stryker: There are early pieces recorded on Prestige that are like sound collages, where he’s anticipating the Art Ensemble of Chicago by a decade or so.

23. And “out” music.

Stryker: When you get to the later years, there’s free music where he expands on the non-Western ideas he had early on.

24. And blends of various folk music.

Stryker: There are things where the improvisation is in a pan-African, pan-Middle-Eastern, pan-Asian environment.

D. Jones: Blues music is American folk music. To me, Yusef embodies the idea of folk music.

25. He made unconventional use of the oboe.

Liebman: He played oboe and flute, and he was quite good at those instruments. Of course, that was unusual in those days.

Lewis: Oboe wasn’t a thing you played in jazz. But that probably influenced generations after him.

Liebman: My wife plays the oboe. It’s not a walk in the park; I’ll tell you that.

D. Jones: Live at Pep’s is like a blues album. He’s playing oboe and flute, but it still takes you there.

Harris: Yusef had a tone, and when he went to the oboe, it was Yusef. When he went to the flute, it was Yusef. No matter what he did, it was Yusef, and you could tell it. He had a special sound.

26. He was part of the Detroit story.

Stryker: Yusef grew up in the heart of the African-American community here in Detroit. Music saturated that community.

Boyd: I went to Northwestern High School, and it was pretty much like a jazz conservatory.

R. Jones: All the Detroit public schools had incredible music programs. They were putting out great musicians, like Milt Jackson and Kenny Burrell from Miller High School; Donald Byrd and Ron Carter from Cass Technical High School; Roy Brooks, Charles McPherson, and Wendell Harrison from Northwestern High School.

Stryker: Yusuf’s family lived above a theater on Hastings Street, a key commercial avenue that bisected the African-American neighborhoods Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. He would sit in the front row and soak up the sound of these big bands. That’s how he heard the great tenor men of the day, like Lester Young, “Chu” Berry, and Coleman Hawkins. You could almost say he listened to these people in his living room.

Harris: Yusef and John Coltrane came to my house. I was teaching these two young cats. I was teaching something that hadn’t been taught. I didn’t believe in twos — two to five. I didn’t believe in that kind of stuff. I believed a five over two is just a chord on the fifth of the five. So how can you play two into five when two is five? People still do it right — they say you’ve got to play the two into five. I think that’s bullshit. Because two is five. This is the kind of stuff I was teaching, and Yusef came. Coltrane came. Joe Henderson came. Hugh Lawson came. All of them came to Detroit! I recognize now that they must have heard about me all over the country. Not that I even thought about this until late in my life. They must have come because they heard about this young piano player.

27. He and his peers had an unmistakable style.

Boyd: When he took his band to New York, Thelonious Monk was in the club, heard him play, and said, “Detroit musicians have got a whole different tempo!” You’re talking about Barry Harris, Tommy Flanagan, Hugh Lawson, and Terry Pollard. You had some of the finest piano players Detroit ever produced.

Harris: You notice he had a sound. A lot of cats nowadays just play straight. They don’t work on having a sound of their own. They don’t play long tones. They don’t use vibrato. Vibrato is your identification. It’s almost like your fingerprint. We know who you are.

28. And Detroit was his launchpad to new dimensions.

Stryker: While Yusef is a quintessential product of the Detroit story, he also traveled further from his roots than any other musician from Detroit. The trajectory of his career took him further than any other Detroit musician, which is interesting.

29. Some of his music is akin to science fiction.

D. Jones: I’ve been watching Lovecraft Country. I feel like Yusef’s music would fit right inside of that. 1984 is a crazy album. The way it starts and ends makes you feel like you’re on a sci-fi adventure at times, but at the same time, a Black one.

30. He tore it up with Cannonball Adderley.

Liebman: He was a wonderful sideman to Cannonball and his brother, Nat Adderley, in the Cannonball Adderley Sextet. The three-horn thing was great. They were loyal to the blues. They had several distinct styles, especially blues playing — honking, screaming, real blues.

Hayes: He added so much to Cannon’s band. With Cannonball, we did a lot of traveling together in cars during that time. When you take together musically, you get to know a person very well.

31. Dizzy Gillespie, too.

Rollins: He was an inspiring musician in Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra. When my buddies and I saw him play with Dizzy Gillespie, before he changed his name to a Muslim name, he sounded great. All us musicians who met him appreciated his playing.

32. He was John Coltrane’s peer and equal.

Coffin: Coltrane’s soprano playing is very much in line with the shenai and other Middle Eastern double-reed instruments. So it wouldn’t surprise me at all if some of that came from Yusef’s friendship and mentorship.

33. His Repository includes a mysterious Trane drawing.

Siegel: At the beginning of The Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns, with no explanation, you’ll see a diagram Coltrane gave to Yusef.

D. Jones: I remember picking up that book and diving into it. There’s John Coltrane’s circle-of-fifths matrix.

Coffin: There’s a hand drawing Coltrane did on the front of Yusef’s book that goes through this heavy harmonic progression Coltrane was into.

D. Jones: It was like going inside of a universe. It felt like some Lord of the Rings shit!

34. He had one foot in academia.

Lewis: Sometimes, you have conversations where it’s like, “This person’s a player, and this person’s an academic.” With Yusef Lateef, those worlds are blurred.

R. Jones: Yusef inspired me to get my bachelor’s degree. He encouraged me to teach and to pass the knowledge I have on to the next generation, which is what I’ve tried to do on a lot of different levels.

Liebman: He was interested in the scholarly aspect of the music. It wasn’t like that was common in those days. There were no jazz schools — very few in the United States.

35. But you don’t need a higher education to enjoy him.

D. Jones: To me, it’s not intellectual. When you put the academic cap on it, it’s all this shit and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

Siegel: He didn’t hole up in an ivory tower.

D. Jones: Yusef plays music. His music is for the people.

36. He was a phenomenal teacher.

Siegel: I’ve interviewed 10 to 15 of his former students. He profoundly impacted their lives, and they’re still learning lessons from him.

37. His chosen name carries power.

“I went to court and had my name legally changed. I took Yusef after the prophet Joseph, and Lateef means gentle, amiable, and incomprehensible,” Lateef wrote in The Gentle Giant.

38. He had a bottomless range of interests.

Boyd: Yusef was very much into mathematics. He was very much into world religions. He was very much into language. How to put together an autobiography — I’ve learned some lessons even in that!

39. He was a multidisciplinary artist.

Stryker: He wrote poetry and short stories and did exhibition-quality drawings of trees.

Rudolph: He was a wonderful artist. He wrote two novels, wrote plays, and painted.

40. By any measure, he was enlightened.

Siegel: He was an academic. He had a doctorate in education.

Stryker: At various points in his life, he used education and concentrated areas of study to reinvigorate his art and ideas. It happened in the ‘50s, it happened in the ‘60s, and it happened in the early ‘80s. I think that’s important.

Liebman: He was multi-leveled, multifaceted. He was a very nice and educated man.

41. He was a liberated soul.

D. Jones: To me, his story is about the idea of freedom. You’re listening to someone being free.

42. He was radically open.

Oran Etkin (clarinet): His openness was very inspiring. He was very interested in discussing philosophical and religious things.

Rudolph: This attitude of openness, freedom, experimentation, projecting your spirit into whatever sound you generate and share, all those things came through the oral tradition, and academia can’t really transmit them.

Kim: Dr. Lateef was open-minded and unafraid about incorporating new sounds into his music. Often when we adopt opinions that music “must be a certain way,” we shut ourselves off from unfamiliar musical experiences, which sometimes are the most enriching. I hope all modern musicians can adopt an open-minded attitude like Dr. Lateef.

43. His discography is oceanic as a result.

D. Jones: You don’t know what you’re going to get if you put on a Yusef Lateef album. It could be anything, and that’s what’s so hip about it.

Liebman: In the ‘70s or ‘80s, his work was packed full of good things. It was a candy basket that never stopped being filled.

44. And he earned every drop of it.

Stryker: His commitment to always learning new things and exploring new ideas — the older you get, the more you begin to see how profound that is.

45. You can engage with it on a complex level.

D. Jones: Is it challenging and uncomfortable at times? Yes. But you’re looking at a person who is being free and themselves. You don’t know what you’re going to get, but the thing is if you’re open, free, and down to go on that journey? Man! It’s going to fuck you up.

46. Or a simple one.

D. Jones: Just look at Yusef’s music from the perspective of Black American music and look at him as a Black American composer, musician, and academic. That’s what he is. You’re looking at an individual who embraced the fullness of Blackness.

Kim: His compositions and improvisations have a melodic storytelling quality, which I appreciate. He plays in a manner that feels understandable and comfortable to the audience, which builds an emotional connection. This approach, I think, is the vehicle through which he successfully introduced non-Western musical influences.

47. Artistically, he has everything you could need.

Jones: Yusef is a planet unto himself. You can fly to Yusef Lateef Planet and just hang. Everything is there. There’s water, earth, vegetation, the sky, clouds, wind, birds, other humanoid figures, fish, mammals, and there may be some magic and alchemy.

48. To know him was to love him.

R. Jones: I think Ornette Coleman once said, “Yusef Lateef has no enemies.”

49. He had a spiritual presence.

Stryker: Because he was a Muslim, had a shaved head, was a big man, the way he dressed, his whole countenance was of this man of real spiritualism and a seeker of truth.

Hayes: His religion had to do with his music because of who he was. It was part of his life, so I’m sure it did. But I can’t speak to that. His religion was his own personal religion.

Rollins: He exemplified everything good about humanity. I’m not a Muslim like he was, but to me, all that stuff doesn’t matter. He could have been Christian or Buddhist or Muslim. To me, he was a good human being.

Rudolph: I considered him to be a radiant being, and he became more and more radiant over the 25 years that I knew him.

Rollins: He just exemplified goodness. You got a spiritual feeling being around him. He certainly exuded so much of that all the time.

50. That extended to how he treated other musicians.

R. Jones: We observed how he reacted not only on the bandstand but off the bandstand. He always acted in the highest spiritual way, dealing with people he didn’t know. The way he carried himself was very influential to us. I never heard Yusef critique anyone’s music negatively. Ever.

51. And how he treated women.

R. Jones: I used to wonder, “Why do you bow to women?” He would not allow women to embrace him. He said, “My wife has that honor.” He would bow to women. Bowing to a person is the highest form of humility that you can do. I observed this and began to look at it the same way and understand.

52. He was humble at all times.

Rudolph: His studiousness relates to being humble. If you feel like, “I know it all, I have my way to do it, and that’s that,” that’s the end, right? But if you’re humble, you can say, “Wow, I can always learn more from somebody else.” I consider him my mentor, but he treated me like a peer.

53. But he was no pushover.

“He radiated peace but took care of business. When a club owner once said he couldn’t afford to pay the band, Lateef picked up the cash register and walked into the back office and refused to leave until he got paid,” Stryker wrote in Jazz From Detroit.

54. He had unshakeable integrity.

Siegel: We all have friends who will say nice things about us, but I’ve never heard anyone say anything bad about him.

55. Much of that had to do with his religious beliefs.

Hayes: Yusef was such a warm gentleman. He was such a dedicated person to his religion and himself.

56. He was willing to take heat for his principles.

Siegel: When he was recording for Atlantic, that was a high-profile label, and someone from there got him on the David Sanborn show Night Music. It was a Tonight Showkind of thing, but it focused on music and the arts. Yusef was one of the guests; he had an album coming out, and they were promoting it. Right before he was supposed to go on, he looked over the contract and saw that Michelob beer was one of the sponsors of the show. He said, “I can’t go on. I can’t do the show because you’re promoting alcohol.” Sanborn’s people were scrambling and said, “We’ll scroll text along the bottom reading that Yusef Lateef doesn’t endorse Michelob beer.” He stuck to his guns and said, “No, I’m not going on.” Which, I’m sure, pissed off the people at Atlantic Records and impacted their bottom line, and I’m sure it pissed off David Sanborn’s people because they had a hole in their schedule. So, they might have been mad at him.

57. And those principles elevated his art form.

D. Jones: When he said, “We shouldn’t be playing in clubs or basements,” he was trying to take the music and put it on another level. To me, it’s a way of trying to help others to see the music from a different perspective, and perspective is everything. He’s saying that if you change the venue, and the person is sitting there like they’re listening to a symphony orchestra, their perspective on what’s happening is going to change.

58. That said, he wasn’t a scold; he was hilarious.

Rollins: He had a sense of humor. We used to have a lot of fun telling jokes and everything.

Rudolph: Things would just crack him up. He had a dry, wry sense of humor, and he enjoyed humor too. There were times on the road where we’d be laughing and laughing at funny stories and things like that.

59. He was a terrific host.

Rollins: I met his wife; he met my wife. We’d been to each others’ homes over the years. He was always gentle and kind and so generous.

Boyd: He had sensitivity and respect for other people. A sense of warmth and gentleness, just like his name, Lateef.

60. He addressed everyone as a sibling.

Coffin: At UMass Amherst, everybody I know who knew him called him “Brother Yusef.” He would call everyone “brother” or “sister.”

61. Even people much younger than him.

Etkin: He used to call me “Brother Oran.” He was many years my elder and my mentor, and there’s no reason he would need to call me “brother,” but that’s the way he saw things and talked to people.

62. He listened before he spoke.

Etkin: He was somebody that made you very aware he was listening. In my mind, the most important thing a musician does is listen.

63. He was radically accepting.

Coffin: He was embracing of everybody, which is what Islam is. When Malcolm X went to Mecca, he had an epiphany. At the end of his autobiography, he said he realized he was praying with people of all colors and all nations. He realized everybody were his brothers and sisters. He had to renounce Elijah Muhammad and the Black Muslims because true Islam is embracing of everybody. As little as I know about Islam, I think Yusef embodied that. He embodied that in his spirit and the way he was giving to other people.

64. He was a voracious reader.

Rudolph: He was always interested in learning new things — not only in music but all kinds of things. I remember telling him that my father-in-law was a scholar of John Dewey, and he was so interested in Dewey. I sent him a copy of Art as Experience, and he read the whole thing.

65. In his craft, he was a perfectionist.

Boyd: He was very much concerned about seriously learning what that music was all about. He wanted to perfect the tone, performance, the technical aspects, the mystical aspects of it.

66. But he never claimed the results were perfect.

Coffin: Because The Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns was handwritten, there are a few little mistakes in it, which gives it feeling to me. I’d be going through it, and I’d be like, OK, this pattern is symmetrical, but all of a sudden, it changes. It might be a half-step off or something. I thought, well, you know, everyone makes mistakes, man — big deal. If you’re playing through it and you find something, fix it. Do the homework, rather than saying, “Oh, there’s a mistake here! It sucks!”

67. He lived modestly.

D. Jones: His office was this little room down in a basement. It was a tiny space.

68. He was inquisitive.

Coffin: I’m assuming that part of his interest in Middle Eastern music was from his conversion to Islam, although it probably wasn’t just the religious aspect. He was probably like, “I wonder what their music is like!” I think he was a curious person. When he converted to Islam, I can only assume that he got into the culture of music also.

69. He showed people who they were.

Boyd: He would ask me a lot of questions. “Who are you?” “What are you about?” I would ask him questions, but he’d turn it around and ask me questions. “What are you doing? What’s your exercise? What’s your latest project?”

Rudolph: Yusef used to say to me, “Brother Adam, we’re evolutionists.”

70. He’s comparable to great spirits throughout history.

Rudolph: People talk about these radiant beings like Hazrat Inayat Khan, Lama Govinda, Thích Nhất Hạnh, Rumi, and the Dalai Lama that we hear or read about, but he was a person we knew who was like that.

71. He was a wholly Black thinker.

D. Jones: This will sound like an intense thing to say, but to me, Yusef Lateef’s music is the epitome of Blackness. It shows how vast and diverse Blackness is. To me, he embodies this intellectualism, but also a connection to the blues is there, overtly. Then, there’s that connection to the cosmos and going beyond, and that street thing is in him as well.

Stryker: He recorded in every imaginable African-American vernacular that there was — bebop, post-bop, blues, gospel, R&B, fusion, free, you name it.

72. He’s a galvanizing force to Black educators.

D. Jones: As a teacher, I want to make sure that I’m representing full-throated, full-bodied Blackness. Not Black from one perspective, but Black from a multitude of perspectives.

73. He wrote classical music.

Stryker: Yusef wrote concert works in the classical tradition. He wrote symphonies, string quartets, solo piano pieces, sonata-like pieces, duets, trios, and chamber music.

74. And he was terrific at it.

D. Jones: What attracts me to Yusef’s music is that you hear that depth. The beginning of 1984 sounds like a symphony orchestra, the way it works.

Stryker: There’s one record called The Centaur and the Phoenix, where he’s playing some extended compositional works by Charles Mills, a contemporary classical composer with interest in jazz. So they’re almost like third-stream works. He’s playing oboe; he’s playing the flute; there’s just so much going on.

75. We can appreciate that the classical world unfairly marginalized him.

D. Jones: Check it out: Yusef played the oboe, and the thing is, Black folks couldn’t participate in the classical world at all. Billy Strayhorn, Nina Simone, and Eric Dolphy were all individuals who desired to participate in the classical realm. Because they were Black, there was no way in, no opportunity, nothing for them to participate in that universe. The very few [that did get in], like Marian Anderson, were marginalized to an enormous level. It wasn’t a logical thing to do. The classical world is white supremacist in many ways.

76. But he forged ahead anyway.

D. Jones: This is a mindset of a very aware, knowledgeable Black individual. He’s saying, “I will not be made to be smaller because of my surroundings.”

77. To disregard him was classical music’s loss.

D. Jones: I say this to my students all the time: “Imagine if Black people didn’t constantly get interrupted. Imagine if they were able to walk into that world and present their work, develop it, and grow.” Our society is creating a narrowing effect. We’re losing out on a lot of beauty because of foolishness.

78. He shows these problems also extend to academia.

D. Jones: If you had Black professors, Black deans, and Black presidents of universities, especially inside the musical realm, you would start to draw more Black students. My story is a perfect example. Yusef Lateef made me aware of something I didn’t know existed. He was a catalyst for me to pursue the work that I’m doing now. You have to have examples, and they can’t be examples that aren’t present or seen.

79. But he left us the tools to fix it.

D. Jones: When you look at his books, philosophies, interviews, and teachings, he’s giving you information on how to do this. He’s teaching you about it. His records are forms of communication that can help you understand how to start to dismantle these things.

80. He never stopped developing.

Stryker: One of the things that’s fascinating about Yusef is that the degree of experimentalism in his music picks up as he gets older. It doesn’t diminish. So think about that — there are very few musicians like that where the older they get, the more experimental they get.

81. He inspires others to self-educate.

Lewis: Yusef Lateef inspires me. I’m reading a lot of molecular biology books and about George Washington Carver. I’m working on some poetry.

D. Jones: He loved nature; I’m one of those people too. I draw a lot from nature.

Lewis: The number of mediums he crosses over into, like literature and visual art, has influenced my work. I gave up on the flute, though.

82. Late in life, he rowed uncharted creative waters.

Stryker: To the extent that Yusef is underrated, I think because the last period of his life was so gargantuan and the music goes in so many directions. It’s so far removed from what we think of as conventional jazz. It’s hard to get your arms around it. You have to sit down and spend some time with it. It’s not a casual listen, and Yusef’s career is not casual.

83. He redefined tradition.

Rudolph: We never got lost in the sense of our own identity. Yusef used to say, “The tradition is to sound like yourself.” You’re tuning in to your voice and putting your music in resonance with your life experience and your environment.

84. He reminded us what soul means.

Rudolph: One of the first books he wrote was How to Improvise Soul Music. He didn’t mean how to perform soul-R&B. It’s soul music, coming from the soul. He always put heart, soul, and deep feeling into his music.

85. He collaborated in livewire ways.

Rudolph: He received a commission from the Rockefeller Foundation to write a piece and asked me to co-compose it with him. He decided it was for 12 musicians, and he had this idea to choose six instruments, and he would write so many bars, tell me how many bars he wrote, and the approximate tempo, like slow, medium, fast. Then he asked me to write for the other same number of bars at a similar tempo. We didn’t hear what the other person did until we were at rehearsal. What an innovative and courageous idea! The surrealists used to do that. They used to paint on each others’ paintings, and they called it Exquisite Corpse.

86. And he could flip the script.

R. Jones: I learned so much about music, about what not to play, how to approach music. Sometimes he would give suggestions about playing something backward or inside-out.

87. His eclecticism wasn’t jarring.

D. Jones: The thing is, you can have Ligeti and all these other guys check out African cultures and bring those influences into their music, but when a Black person does it, it’s considered avant-garde or unusual.

88. His body of work is nourishing.

D. Jones: To me, Yusef is a full-course meal. He’s beyond only apple pie. You get your vegetables, meat, protein, carbs, water, and dessert.

89. Which means it’s substantial and never junk food.

D. Jones: It’s not about what I want. It’s about what I need and what goodness can be fed to my soul.

90. His music is never egotistical.

Coffin: It’s not about “Dig me.” It’s about “Dig the music.”

91. That’s why it gets less attention.

Siegel: Yusuf was under the radar. Even though he won a Grammy and was an NEA Jazz Master, he wasn’t playing in clubs. He led a very quiet life.

92. But his profile is worth raising today.

Rudolph: When people listen to his music, it’s alive if they find a place within themselves where it resonates inside of them and becomes something living, not just entertainment.

Rollins: Good people like Yusef never get enough notoriety. His life is going to be so important.

93. Understanding him begins with listening to him.

Siegel: Listening to his music is the best way to get to know him. To get to know him, I’d pick a couple of albums from every decade, from the 1950s to the 2010s, and start there.

Hayes: The music speaks for itself. All a person has to do is listen to the music. That will say enough as to the kind of relationship we had. Listen to the music, and that will say everything.

94. And you can spend a lifetime in his world if you want.

D. Jones: I don’t get tired of Yusef like I do some other artists because he’s willing to move in a different fashion at all times.

95. We can mirror his qualities.

Lewis: When someone like Yusef Lateef leaves the kind of body of work that he did, it should only inspire us to continue to peel back our onion within our own experience.

96. Like him, we can fulfill our creative potential.

Lewis: I don’t think everyone is afforded the opportunity to present who they are in so many different mediums.

97. We can rethink the way we teach.

D. Jones: He is part of the matrix that informs my perspective on how to change the paradigm and the world of academia.

98. We can be kind to others like he was.

Rollins: He was one of the best human beings I’ve met in my life. He was such a good person.

99. And leave an immense impression as a result.

Rollins: I must have done something right in my previous life to have had a chance to meet an individual like Yusef.

100. Brother Yusef lives.

Hayes: Brother Yusef was an amazing person. What a gentleman. We had a warm, magnificent relationship together.

Lewis: God, I wish I would have met him. I would have thousands of questions.

Hayes: I hope he’s having a wonderful journey. I hope he had a great journey here, and I hope he’s having a great journey now. All the best to you, my brother, Yusef Lateef.

D. Jones: That, for me, is Yusef Lateef. That’s what makes him beautiful. I don’t know how to simplify it any more.

An Interview With Yusef Lateef

SUN: I know you carne from Chattanooga, Tennessee, originally. When did you come to Detroit?

YUSEF: In 1925.

SUN: So you were . . .

YUSEF: Five years old.

SUN: Who or what was your inspiration?

YUSEF: My father and mother. My mother played piano and my father sang. Not professionally, you know, but they were marvelous musicians. The first band I played with was a high school band here in Detroit. It was called Massy Rucker and the 13 Spirits of Swing, out of Miller High School. In 1939 we went on a tour through the United States- we left high school and toured, primarily the south, for a whole year, under the leadership of Harvey Toots- he's dead now. Then we returned and finished high school in '41, at Miller High. It's Miller ]r. High School now.

SUN: We've run into any number of musicians who went to Miller High School . . .

YUSEF: Yeah, Milt Jackson was in the same music class that I was. Kenny Burrell's brother, Billy Burrell, was in school with me also. Kenny was younger than I was. He went to Miller after I had left. Let's see, who else was there? Of course there was a tenor player maybe you have never heard of, Lorenzo Lawson. SUN: I've heard the name.