SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER ONE

CHARLES MINGUSJEREMY PELT

(April 17-23)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

(April 24-30)

AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS

(May 1-7)

KARRIEM RIGGINS

(May 8-14)

ETTA JONES

(May 15-21)

YUSEF LATEEF

(May 22-28)

CHRISTIAN SANDS

(May 29—June 4)

E. J. STRICKLAND

(June 5-11)

TAJ MAHAL

(June 12-18)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

(June 12-18)

DOM FLEMONS

(June 19-25)

HEROES ARE GANG LEADERS

(June 26-July 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/etta-jones-mn0000207498/biography

Etta Jones

(1928-2001)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

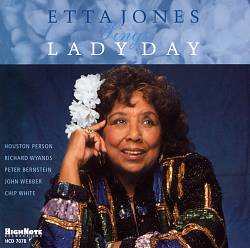

An understated, dynamic singer within jazz and popular standards, Etta Jones was an excellent singer always worth hearing. She grew up in New York and at 16, toured with Buddy Johnson. She debuted on record with Barney Bigard's pickup band (1944) for Black & White, singing four Leonard Feather songs, three of which (including "Evil Gal Blues") were hits for Dinah Washington. She recorded other songs during 1946-1947 for RCA and worked with Earl Hines (1949-1952). Jones' version of "Don't Go to Strangers" (1960) was a hit and she made many albums for Prestige during 1960-1965. Jones toured Japan with Art Blakey (1970), but was largely off record during 1966-1975. However, starting in 1976, Etta Jones (an appealing interpreter of standards, ballads, and blues) began recording regularly for Muse, often with the fine tenor saxophonist Houston Person. She died from complications of cancer on October 16, 2001, the day her last album, Etta Jones Sings Lady Day, was released.

Etta Jones

Etta Jones - vocalist, recording artist (1928-2001)

Etta Jones was a fine jazz singer who made the most of her vocal talents. She retained a loyal following wherever she sang, and was held in the highest regard by her fellow musicians. Her last three decades were her most productive, in both the quantity and artistic quality of her work.

She was born in South Carolina, but brought up in Harlem. She entered one of the famous talent contests at the Apollo Theatre as a 15 year old, and although she did not win, she was asked to audition for a job with the big band led by Buddy Johnson, as a temporary replacement for the bandleader's sister.

Johnson's band was popular on the black touring circuit of the day, and the experience provided a good grounding for the singer. Etta stayed with Johnson's big band for a year and then went out on her own in 1944 to record several sides with noted jazz producer and writer Leonard Feather. In 1947, she returned to singing in big bands, one led by drummer J.C. Heard and the next with legendary pianist, Earl “Fatha” Hines, whom she stayed with for three years. She worked for a number of bands in the ensuing years, including groups led by Barney Bigard, Stuff Smith, Sonny Stitt and Art Blakey, but went into a period of virtual obscurity from 1952 until the end of the decade, performing only occasionally.

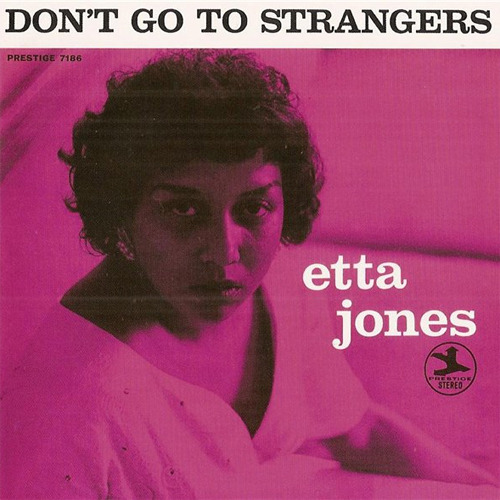

In 1960, she was offered a recording opportunity by Prestige Records, and immediately struck gold with her hit recording of “Don't Go To Strangers.” She cut several more albums for them in the next five years, including a with-strings session, and a guest spot on one of saxophonist Gene Ammons's many records.

In 1968, at a Washington, D.C. gig, Etta teamed up with tenor saxophonist, Houston Person and his trio. They decided to work together and formed a partnership that lasted over 30 years. She toured Japan with Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers in 1970, but after her final date for Prestige in 1965, she did not make another album until 1976, when she cut “Ms Jones To You” for Muse.

Her closest collaborator in that period was Houston Person, and they cut a string of well-received recordings from the mid-70’s onward, including the Grammy nominated albums “Save Your Love For Me,” (1981) and “My Buddy: Etta Jones Sings the Songs of Buddy Johnson” (1999). They developed an appealing, highly intuitive style of musical response, and were always jointly billed. The pair was married for a time, and he became her manager, and produced most of her subsequent records, initially for Muse Records, and then its successor, High Note.

As if to make up for lost time, she recorded eighteen records for the company, and worked steadily both in New York and on the international jazz festival circuit, including appearances in New York with pianist Billy Taylor at Town Hall and saxophonist Illinois Jacquet at Carnegie Hall.

She favored a repertoire of familiar jazz standards; the improvisatory style of her phrasing drew at least as much on the example of horn players as singers, but owed something to Billie Holiday in its sensitivity and phrasing (she was said to do remarkable impersonations of Holiday in private). She took a tougher, blues-rooted approach from Dinah Washington or the less familiar Thelma Carpenter, a singer with the Count Basie band whom Jones acknowledged as an early influence on her own style.

Unfortunately, her physical health began deteriorating, yet she re-emerged in the early 1990s with a new passion for life and a spirit for musical adventure. She took on more solo gigs and began collaborating with young musicians such as pianist Benny Green and veteran bluesman Charles Brown. She continued to perform regularly until just before her death, and still had forthcoming engagements in her diary when she succumbed to complications from cancer. Ironically, her last recording, a Billie Holiday tribute entitled “Etta Jones Sings Lady Day,” was released in the USA on the day of her death, in 2001.

Etta Jones

Singer

Jazz vocalist Etta Jones who was born on November 5, 1928, in Aiken, SC; died on October 16, 2001, in Mount Vernon, NY.recorded more than two dozen albums and earned three Grammy Award nominations during her six-decade-long career. Her popularity peaked in 1960 with the release of her single “Don’t Go to Strangers,” which climbed to number five on the R&B charts. In the late 1960s Jones formed a duo with tenor saxophonist Houston Person, with whom she toured for the next 35 years. “All I want to do is work, make a decent salary, and have friends,” Jones told National Public Radio in a quotation cited in the Dallas Morning News. Although she never attained a level of stardom comparable to such jazz and blues greats as Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, and Dinah Washington, Jones had a devoted following of listeners and made her own unique mark on jazz history.

Jones was born on November 5, 1928, in Aiken, South Carolina, and raised in New York City. As a three year old she dreamed of becoming a singer and would pose in front of a mirror to mimic songs from the radio. Billie Holiday, whom she saw in concert, and Thelma Carpenter, were some of her earliest influences. When Jones was 15 years old, she attended Amateur Night at the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem. Like jazz greats Ella Fitzgeraldand Sarah Vaughn, her career began at the Apollo, though at first glance her debut did not seem promising. On that evening in 1943 she was so nervous that she started singing off key and lost the talent competition. Yet the pianist-bandleader Buddy Johnson recognized her ability. Johnson immediately hired her to fill in for his vocalist sister, Ella Johnson, who was leaving the band to have a baby.

Jones toured with Johnson’s 19-man band for a year, until Ella returned, thus beginning a series of stints with other medium- and big-band New Yorkjazz groups, including the Harlemaires and the Barney Bigards Orchestra. It was with the latter that Jones made her first recording, arranged by pianist Leonard Feather in 1944. In subsequent years she performed and recorded with such jazz personalities as Pete Johnson, J. C. Heard, Kenny Burrell, Charles Brown, Milt Johnson, and Cedar Walton. In 1949 she started singing with Earl “Fatha” Hines, performing with his band for the next three years.

Jones also attempted to launch a solo career, though she was not successful at first. She recorded sides with such labels as Black & White and RCA Victor, but these singles flopped. At the time, R&B was enjoying increased popularity, but Jones avoided this genre, preferring to sing jazz. This decision limited her audience and her exposure as an artist, and for a number of years she remained an obscure singer.

Throughout the 1950s Jones faced hard times and had to take day jobs occasionally to make ends meet, working as an elevator operator, an album stuffer, and a seamstress. She continued to perform sporadically, as opportunities arose. In 1956 Jones recorded her first ull-length album, The Jones Girl… Etta … Sings, Sings, Sings, with King Records. But the album debuted with little fanfare and went largely unnoticed.

The tables turned for Jones in 1960 when her manager, Warren Lanier, sent a demo tape to Esmond Edwards, a producer at Prestige Records. Edwards liked the tape and decided to sign Jones immediately. On the Prestige label she recorded the album Don’t Go to Strangers, released in 1960. Since Strangers was a jazz album, no one expected it to appeal to a mainstream audience. Yet the title song was an instant hit, selling one million copies and putting Jones’ name on the top 40 charts. The song even earned her a Grammy Award nomination—the first of three in her career. While Jones was not an overnight success, she was a sudden success. Her weekly income increased from $50 to $750. Riding on this triumph, Jones recorded several more albums for Prestige throughout the 1960s. But, jazz audiences were dwindling in the United States with the arrival of the Beatles and the growing popularity of pop and rock sounds.

In 1968 Jones formed a musical partnership that would change her career. She met Houston Person, a highly regarded tenor saxophonist, when the two performed on the same bill at a Washington, D.C., nightclub. Jones and Person immediately hit it off, and they decided to tour together as a duo with equal billing, a partnership that would last for more than three decades. “They say… a lot of times singers and musicians don’t get along too well,” Jones told Billy Taylor of Billy Taylor’s Jazz at the Kennedy Center on National Public Radio in 1998, “but we got along famously.”

Person became not only Jones’ collaborator but also—after 1975—her manager and record producer. Their connection was so close that some jazz aficionados have mistakenly assumed they were married, though they were not. Yet their rapport as musicians was unique, and they developed a conversational style with vocals and saxophone riffs. “[Person] knows exactly what I’m going to do,” the New York Times recalls Jones saying. “He knows if I’m in trouble; he’ll give me a note. He leaves me room.”

From the mid-1970s until her death in 2001, Jones and Person recorded 18 albums for the Muse label, which later became High Note Records. While these albums appealed to a relatively narrow audience of jazz aficionados, they occasionally contained minor hits attracting a wider group of listeners. In 1981 Jones received a Grammy Award nomination for her album Save Your Love for Me. A third Grammy nomination came in 1999 for her tribute to her former boss, My Buddy—Etta Jones Sings the Songs of Buddy Johnson.

Late in her career, Jones was able to relax into her role as a highly respected, traditional jazz singer. “When I first started, I had to do some songs I didn’t care for, but now I more or less sing what I want to sing,” she told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1993, as quoted in the Washington Post. “I want a good lyric. I don’t want nonsense. I like heavy dramatic tunes—a tune that’s saying something, like Sammy Cahn’s ‘All the Way.’”

After a battle with cancer, Jones died on October 16, 2001. She was survived by her husband, John Medlock, two sisters, and a granddaughter (a daughter predeceased her). The day she died, High Note released her final recording, Etta Jones Sings Lady Day.

Selected discography:

Don’t Go to Strangers, Prestige/OJC, 1960.

Etta Jones and Strings, Original Jazz, 1960.

Something Nice, Prestige/OJC, 1961.

From the Heart, Prestige/OJC, 1962.

Hollar, Prestige, 1962.

Etta Jones’ Greatest Hits, Prestige, 1967.

Ms. Jones to You, Muse, 1976.

My Mother’s Eyes, Muse, 1977.

Save Your Love for Me, Muse, 1981.

Fine and Mellow, Muse, 1987.

Sugar, Muse, 1989.

Reverse the Charges, Muse, 1991.

At Last, Muse, 1993.

Doin’ What She Does Best, 32 Jazz, 1998.

My Buddy: Songs of Buddy Johnson, High Note, 1998.

Etta Jones Sings Lady Day, High Note, 2001.

Sources

Periodicals

Los Angeles Times, October 19, 2001, p. B13.

New York Times, October 19, 2001, p. C12.

Times (London), October 24, 2001, p. 19.

Washington Post, October 18, 2001, p. B6.

Online

“Etta Jones,” All Music Guide, http://www.allmusic.com. (January 28, 2002).

“Etta Jones,” Billy Taylor’s Jazz at the Kennedy Center, National Public Radio, http://www.npr.org/programs/btaylor/archive/jones_e.html (January 28, 2002).

“Etta Jones, Prolific, Soulful Jazz Vocalist, Nominated Twice for Grammys, Dies,” Dallas Morning News, http://www.dallasnews.com/obituaries/STORY.e99db45424.b0.af.0.a4.d797.html (January 28, 2002).

“Houston Person and Etta Jones at Joe Siegel’s Jazz Showcase in Chicago,” JazzSet, National Public Radio, http://www.npr.org/programs/jazzset/archive/2001/011206.ejones.html (January 28, 2002).

“Remembering Etta Jones,” All About Jazz, http://www.allaboutjazz.com/articles/arti1101_03.htm (January 28, 2002).

—Wendy Kagan

Bob Perkins Remembers The Time He Met Singer Etta Jones

But who’s to know early on what they will eventually become? How much information on how many people and subjects should be stored away for possible future use?

I entered into communications many years ago and, fortunately, my rewind button has been of great assistance in helping me make a living. In this column, I decided to write about singer Etta Jones. My recall took me back to the mid 1950s, when I first saw and heard her perform at a little club in Philly. She had not become “the” Etta Jones yet, and I certainly had no idea that six decades later, she would not be alive and I’d be writing a column about her.

I liked what I’d heard from Ms. Jones that night at the little club in Philly. I don’t remember hearing much about and from her, until her 1960 hit, “Don’t Go To Strangers.” When the single became an LP, it went gold.

I didn’t hear much about Etta between that first time, and “Strangers,” because she hadn’t been doing much recording. She was working to make ends meet, as an elevator operator, seamstress, and stuffing LPs into jackets for a major record company.

With “Don’t Go To Strangers,” Etta Jones became a known entity in the entertainment world. But that recognition came after a long apprenticeship, which began with her entering an amateur contest in 1943 at the age 15. Even though she did not take first prize, she caught the ear of bandleader Buddy Johnson and sang with his band for a year. She later recorded a few sides with the famed pianist and jazz authority Leonard Feather, then went on to sing in the bands of J.C. Heard and Earl “Fatha” Hines. The stint with Hines lasted three years.

But Etta’s successful single and follow-up LP did not bring her the future success expected. She made a number of other albums for Prestige and other labels, but nothing major happened, even though she had great looks, a fine voice, and knew how to put over a song as well as any of her female vocal contemporaries.

A change for the better came when she met saxophonist and bandleader Houston Person, who had a keen understanding of the recording industry, and not only was producing his own recording sessions for the Muse label, but those of other artists, too. He and Etta decided to join forces, travel together and work as a team, and they did so successfully for better than 30 years.

This took Etta out of the race for wider recognition she hadn’t been able to capture. Person was an excellent tenor saxophonist and bandleader, knew the music business, and was always working. He and Etta traveled together domestically and abroad, and were always in high demand. Each worked independently on occasion, but most of the time they appeared together, which gave rise to the belief among jazz writers and fans that they were married.

In 1977, I finally got to meet the lady I’d seen and heard when I introduced Etta and Houston at another club in Philly, at which I was the emcee. I continued to follow Etta’s career over the years, and whenever possible would attend her and Houston’s appearances.

In 2001, I learned she was seriously ill and may not have long to live. I was present at one of her last concerts in Atlantic City in July of that year. She had to be helped onstage and sang while seated. But standing or seated, it was still Etta Jones. I saw her after the show, and knew it would probably be the last time—and it was. Etta passed away a couple of months later, just shy of her 73rd birthday.

Etta Jones, a very fine singer of song who for whatever reasons didn’t get all the accolades her talent earned. I guess some folks just didn’t recognize her talent. She received three Grammy nominations and in 2008, her album Don’t Go To Strangers was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Much like Heinz, the maker of condiments who boasts having 57 varieties, Etta had at least that many ways of interpreting a song. She once said, “I never sing a song the same way again. I can’t even sing along to my own records.”

So even after six decades, every now and then the image and the memory of when and where I first saw and heard Etta Jones pops into my noggin.