SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER THREE

MAX ROACH

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BEN WEBSTER

(September 7-13)

GENE AMMONS

(September 14-20)

TADD DAMERON

(September 21-27)

ROY ELDRIDGE

(September 28-October 4)

MILT JACKSON

(October 5-11)

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN

(October 12-18)

GRANT GREEN

(October 19-25)

ROY HARGROVE

(October 26-November 1)

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT

(November 2-8)

BLUE MITCHELL

(November 9-15)

BOOKER ERVIN

(November 16-22)

LUCKY THOMPSON

(November 23-29)

Roy Eldridge

(1911-1989)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

One of the most exciting trumpeters to emerge during the swing era, Roy Eldridge's

combative approach, chance-taking style and strong musicianship were an

inspiration (and an influence) to the next musical generation, most

notably Dizzy Gillespie. Although he sometimes pushed himself farther than he could go, Eldridge never played a dull solo.

Roy Eldridge started out playing trumpet and drums in carnival and circus bands. With the Nighthawk Syncopators he received a bit of attention by playing a note-for-note re-creation of Coleman Hawkins' tenor solo on "The Stampede." Inspired by the dynamic playing of Jabbo Smith (Eldridge would not discover Louis Armstrong for a few years), Eldridge played with some territory bands including Zack Whyte and Speed Webb and in New York (where he arrive in 1931) he worked with Elmer Snowden (who nicknamed him "Little Jazz"), McKinney's Cotton Pickers, and most importantly Teddy Hill (1935). Eldridge's recorded solos with Hill, backing Billie Holiday and with Fletcher Henderson (including his 1936 hit "Christopher Columbus") gained a great deal of attention. In 1937 he appeared with his octet (which included brother Joe on alto) at the Three Deuces Club in Chicago and recorded some outstanding selections as a leader including "Heckler's Hop" and "Wabash Stomp." By 1939 Eldridge had a larger group playing at the Arcadia Ballroom in New York. With the decline of Bunny Berigan and the increasing predictability of Louis Armstrong, Eldridge was arguably the top trumpeter in jazz during this era.

During 1941-1942 Eldridge sparked Gene Krupa's Orchestra, recording classic versions of "Rockin' Chair" and "After You've Gone" and interacting with Anita O'Day on "Let Me Off Uptown." The difficulties of traveling with a White band during a racist period hurt him, as did some of the incidents that occurred during his stay with Artie Shaw (1944-1945) but the music during both stints was quite memorable. Eldridge can be seen in several "soundies" (short promotional film devoted to single songs) of this era by the Krupa band, often in association with O'Day, including "Let Me Off Uptown" and "Thanks for the Boogie Ride." He is also very prominent in the band's appearance in Howard Hawks' Ball of Fire, in an extended performance of "Drum Boogie" mimed by Barbara Stanwyck, taking a long trumpet solo -- the clip was filmed soon after Eldridge joined the band in late April of 1941, and "Drum Boogie" was a song that Eldridge co-wrote with Krupa.

Eldridge had a short-lived big band of his own, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic, and then had a bit of an identity crisis when he realized that his playing was not as modern as the beboppers. A successful stay in France during 1950-1951 restored his confidence when he realized that being original was more important than being up-to-date. Eldridge recorded steadily for Norman Granz in the '50s, was one of the stars of JATP (where he battled Charlie Shavers and Dizzy Gillespie), and by 1956, was often teamed with Coleman Hawkins in a quintet; their 1957 appearance at Newport was quite memorable. The '60s were tougher as recording opportunities and work became rarer. Eldridge had brief and unhappy stints with Count Basie's Orchestra and Ella Fitzgerald (feeling unnecessary in both contexts) but was leading his own group by the end of the decade. He spent much of the '70s playing regularly at Ryan's and recording for Pablo and, although his range had shrunk a bit, Eldridge's competitive spirit was still very much intact. Only a serious stroke in 1980 was able to halt his horn. Roy Eldridge recorded throughout his career for virtually every label.

Roy David Eldridge was a jazz trumpet player in the Swing era. His sophisticated use of harmony, including the use of tritone substitutions, resulted in him sometimes being seen as the link between Louis Armstrong-era swing music and Dizzy Gillespie-era bebop. Roy's rhythmic power to swing a band was a dynamic tradmark of the Swing Era.

Eldridge was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Eldridge played in the bands of Fletcher Henderson, Gene Krupa and Artie Shaw before making records under his own name. He also played in Benny Goodman's and Count Basie's Orchestras, and co-led a band with Coleman Hawkins.

Also known as “Little Jazz” Roy Eldridge was a fiery, energetic trumpeter who although short in stature was a larger-than-life figure in the jazz trumpet lineage. Stylistically speaking he was the bridge between the towering trumpet stylists Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie. One of a significant number of jazz greats from the city of Pittsburgh, Roy’s first teacher was his alto saxophonist older brother Joe. Some of the great rhythmic drive of Eldridge’s later trumpet exploits could be traced to his beginnings on the drums, which he began playing at age six. His first professional work came at age 16 when he worked with a touring carnival, playing drums, trumpet, and tuba.

As a trumpeter Roy had come under the spell of Louis Armstrong’s irrisistable style. Among his earliest band affiliations were Oliver Muldoon, Horace Henderson, Zack Whyte, Speed Webb, and his own band, under the banner of Roy Elliott and his Palais Royal Orchestra. In 1930 he made the move to New York and headed straight to Harlem, where he gained work with a number of dance bands, among which was the Teddy Hill band. He left New York in 1934 to join the Michigan-based McKinney’s Cotton Pickers alongside such significant players as tenor man Chu Berry. Roy returned to New York to rejoin Teddy Hill in 1935, with whom he made his first recordings as a soloist in 1935. Prior to recording with Hill he toured with the Connie’s Hot Chocolates revue. After he left Hill’s band he became the lead trumpeter in Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra where his upper register abilities were highlighted. It didn’t take long for Eldridge to exert himself as a bandleader, forming his own octet in 1936 in Chicago; a band which included his brother Joe.

Eldridge recorded with the Three Deuces group, then left music for a short time to pursue radio engineering, an interesting twist considering his Chicago group’s nightly radio broadcasts. By the end of the 1930s after freelancing with such a wide array of bands Eldridge had gained notice as one of the swing bands’ most potent soloists. In 1941 he joined drummer Gene Krupa’s band. Not only did he provide trumpet fireworks for Krupa’s outfit he also sang, recording a memorable duet with the band’s female singer, Anita O’Day (NEA Jazz Master 1997) on the tune “Let Me Off Uptown” in 1941. Later, after Krupa’s band disbanded in 1943, and a period of freelancing, he toured with the Artie Shaw band in 1944. After Shaw it was time for Roy to lead his own big band, though economics forced him back to small swing groups.

In 1948 Norman Granz recruited Eldridge for his Jazz at the Philharmonic, an ideal situation for Roy since he was one of the ultimate jam session trumpeters. He toured briefly with Benny Goodman and took up residence in Paris in 1950, where he made some of his most successful recordings. He returned to New York in 1951 and continued freelancing with small bands, including work with Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Ella Fitzgerald, and Johnny Hodges. He made notable albums for Verve Records alongside Hawkins and continued freelancing and leading a house band at Jimmy Ryan’s club in New York. In 1980 he was felled by a stroke but that didn’t cut off his musicality. Disabled from the rigorous demands of playing the trumpet, Eldridge continued to make music as a singer and pianist until his 1989 passing.

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/roy-eldridge

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-02-28-ca-691-story.html

When Roy (Little Jazz) Eldridge died on Sunday, it was obvious, whatever the official cause of death, that he was the victim of a broken heart. His wife of 53 years, Viola, had recently died, and Eldridge, 78, felt he had nothing to live for. (In a bizarre coincidence, Eldridge’s cousin Reunald Jones Sr. also died Sunday in Los Angeles. He, too, was 78 and played trumpet in many name bands.)

Eldridge had been forced to put down his trumpet forever after suffering a stroke in 1980, and had been seen publicly since then only in occasional appearances singing and playing drums.

My first exposure to Eldridge was a magical evening in 1936 at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom; he was with Teddy Hill’s memorable band, with saxophonist “Chu” Berry as the other principal soloist.

Because Eldridge was unknown then, having made almost no records, his unique, searing sound and impassioned style came as a revelation. After he and Berry joined the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra he began to achieve recognition as the first major trumpet influence since Louis Armstrong.

In Chicago, in 1938, Roy played at the Three Deuces with an incredible small band. Art Tatum was at the piano; John Collins was the guitarist, Zutty Singleton the drummer. This was Swing era combo music at its supreme level.

In May, 1940, Milt Gabler and I produced a session for Commodore Records with Eldridge, Benny Carter and Coleman Hawkins in the front line. Roy’s solos in this intimate setting became classics that have been reissued time and again.

He played alongside Louis Armstrong for their first joint appearance in the Esquire Allstars concert at the Metropolitan Opera House. Roy’s disposition always seemed happy and outgoing; it was not until after his later experiences with Jim Crow that bitterness surfaced.

“Artie came in and he was real great. He made the guy apologize that wouldn’t let me in, and got him fired.

“Man, when you’re on the stage, you’re great, but as soon as you come off, you’re nothing. It’s not worth the glory, not worth the money, not worth anything. Never again!”

Happily, Eldridge did not have to live up to his resolution. Conditions improved a little, and by 1949 he was back in the Krupa band. The following year he worked with Benny Goodman, touring Europe, then stayed on the Continent playing with everyone from Sidney Bechet to Charlie Parker and recording, among other things, a delightful blues vocal in French, “Tu Disais Que Tu m’Aimais.”

Much of the rest of his playing career was with mixed bands, most notably on tour with Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic (named for Los Angeles’ Philharmonic Auditorium). He also co-led a quintet with Coleman Hawkins.

Roy Eldridge was to the evolution of jazz trumpet in the 1930s and early ‘40s what Armstrong had been in the ‘20s, and what Dizzy Gillespie would be from the mid-'40s, what Miles Davis would be in the ‘50s. He recorded with everyone from Art Tatum and Harry (Sweets) Edison and Oscar Peterson and Bud Freeman, with a string ensemble with a Dixieland band.

How it must have rankled him, during those last eight years when playing was forbidden to him, to see so many avenues opening up. What a joy it would have been to share his company, and his sound, at the jazz parties and on the jazz cruises. The last time we talked, a year ago, he sounded as cheerful as ever. If he was laughing on the outside and still crying on the inside, he did a magnificent job of concealing it.

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-02-27-mn-399-story.html

If you haven’t cozied up to Gary’s storytellings, you might want to start with a copy of Rhythm-a-ning: Jazz Tradition and Innovation.

You can locate more information about this book and others that Gary has written by visiting him at www.garygiddins.com.

The showiest expressions of passion frequently border on outright pandering, but immoderation of that sort is a healthy symptom — it tends to proliferate in a milieu where authentic excitement also flourishes. Over the past decade, excitement has been scarce to a degree that not even the spaciest '50s cool-jazz hipster could have anticipated, while vulgarity continues unabated in its new garb, substituting pretentious meditation for caterwauling. Still, that part of the audience that hasn't been rendered insensible by ECM-styled stabiles of sound, in which slowness indicates profundity, hungers for le jazz hot, as witness the gratitude with which it greets the appended swing theme that, in so many contemporary performances, caps an hour's worth of esoteric clamor. …

Trumpeter Roy Eldridge's legendary sound and bravado dwarfed his 5'6" frame. Known as "Little Jazz," and later just "Jazz," his nicknames befit his devotion (five decades) to the art form. His peers spoke of his soulful style and great competitiveness, not to mention his ridiculous chops. These qualities marked him as one of the greatest trumpet kings of all time; he reigned from the late 1930s and beyond, when many other top trumpeters came into the fold.

But Eldridge's legend endured. He was an innovator who, for many historians, conveniently bridged the gap between Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie in jazz's evolutionary chain. This may be hyperbole or an oversimplification, but many agree that Eldridge modernized the way to play jazz. And nobody ever discounted the red-hot passion that once crackled from his brass. On Jan. 30, Eldridge would have been 100, so we celebrate The Little Jazz Centennial with some of his fieriest early performances.

Hear "Rockin' Chair" on A Blog Supreme.

https://www.nytimes.com/1981/06/30/arts/roy-eldridge-s-ambition-to-outplay-anybody.html

https://jerryjazzmusician.com/2015/01/roy-eldridge-story/

Roy was born on January 30, 1911 in Pittsburgh Pa. One of the most exciting trumpeters to emerge during the swing era, Roy Eldridge’s combative approach, and strong musicianship were an inspiration and influence to the next musical generation, most notably Dizzy Gillespie. Although he sometimes pushed himself farther than he could go, Eldridge never played a dull solo.

Roy Eldridge started out playing trumpet and drums in carnival & circusbands. He would not discover Louis Armstrong for a few years. He worked with bands of Zack Whyte and Speed Webb in 1931. He worked with Elmer Snowdenwho nicknamed him “Little Jazz” also McKinney’s Cotton Picker’s and most importantly Teddy Hill in 1935. Eldridge recorded solos with Hill backing Billie Holiday and with Fletcher Henderson including his 1936 hit, “Christopher Columbus” gained a great deal of attention. In 1937 he appeared with his octet with his Brother Joe on Alto Sax at the Three Deuces Club in Chicago. His group recorded some outstanding selectionsas a leader, including: “Heckler’s Hop” & “Wabash Stomp”.

The Summer of 1938, I was playing with the Joaquin Grill Orchestra at the Willows at Oakmont Pa. on the Allegheny River. One night after we finished playing at 1:00 a.m. my friends, Louis Mitchell trpt. and Cliff Fishbackour arranger and piano player, decided to go into Pittsburgh about 15 milesaway to a Jazz Club . It was a place where some of the local jazz playerswould go to jam. It all would start late at night and could go on till thewee hours of the morning. We arrived around 1:45 a.m. and the place was nothingmuch to look at. We walked up a full flight of stairs and our ears told usthat we arrived at the right place. It was jumping with some great sounds.

As we walked into the room where all the music was coming from, we couldn’t see a thing because the room was filled with cigarette smoke. As we lookedaround for a place to sit, the band started up again. It sounded fine, but when the trumpet player started up we realized that it was the great Eldridge. What a surprise. Roy was one of our favorite players and here we were in the same room with him.

Roy Eldridge and his Band had just finished a long engagement at the ‘Three Deuces’ a famous Jazz Club in Chicago. They had a lot of air time broadcasting from that spot and we would always try to hear him whenever we could get near a radio from where ever we would be. He was our favorite jazz player.

Of course Cliff, Lou and I went to hear the band rehearse at Eldredge’s home the next afternoon. His home was across the Allegheny River in an industrial area near the Heinz Ketchup factory…As we entered Roy’s house we could hear his band playing and it sounded great, even with the smell of ketchup in the air it was a memorable experience…The band sat around in a relaxed manner and without music stands played head arrangements. We enjoyed the day…

We invited Roy and his Brother Joe to our home in Oakmont for a dinner that I would cook. Cliff, Lou and I rented this beautiful brick home for the summer while we were playing the music job at the Willows. I must say that renting this home was probably the best deal anyone could have. It so happened that this elegant home belonged to two elderly women that were going to Europefor the summer and as our engagement at the famous Willows was booked for the summer, we were able to rent this home…It was completely furnishedwith beautiful furniture in all the rooms on two floors and all the dishes, pots and pans, and silverware included for the unheard of sum of $90.00 per month (unbelievable even for 1938.) and linens too…We split the cost 4 ways, Cliff, Lou, myself and Joe Bruhl & wife Vera. As I remember, I think we took good care of the place.

Roy and Joe Eldridge came over for dinner the next afternoon. We enjoyed each others company talking about the music business in general…Roy told me that when he first started playing the trumpet he didn’t even have a trumpet lesson book, but he used his brother Joe’s clarinet music book to learn. We also took several pictures together with our cameras. I servedan Italian dinner that everyone seemed to enjoy.

By 1939 Roy had a larger group playing at the Arcadia Ballroom in New York. With the decline of Bunny Berigan and the increasing predictability of LouisArmstrong, Roy Eldridge was arguably the top trumpet player in jazz during this era

During 1941-1942, Eldridge sparked the GENE KRUPA ORCHESTRA recording a classic version of ‘Rockin Chair’ and ‘After you’ve gone’ and interacting with Anita O’Day on the great recording of “Let Me Off Uptown”.

It was about this time that the Gene Krupa Band was riding on a high as a bandleader, came to Sacramento, California. It was September of 1941 and Krupa’s Band with Anita and Roy were engaged to do a show at the California S

tate Fair. By coincidence I was hired to play in the State Fair Concert Orchestra. It was 3 years since I had seen Roy and I was looking forward to see him again. After I finished my job that night, I went where the Gene

Krupa Band was performing and after they finished their show I went backstageand there was ‘Little Jazz’. It was good to see him and we talked about goingsomewhere to visit. He introduced me to some of the musicians and the famous Anita O’Day. Meanwhile Roy said that the Band members were going downtown to the Senator Hotel where they were going to stay for the night, but becausehe was a black man he would not be able to stay with the rest of the bandand would look around and see where to stay for the night. I said “Roy, you will stay with me.” I know that Roy remembered Lou Mitchell from our meeting in Pittsburgh and told him that I had a place in his family home with Lou’smother, Mrs. Mitchell…Lou was working in the music studios of Hollywood at the time.

Roy said that would be great . We went home and after a good nights rest I went upstairs to the main floor where Mrs. Mitchell would be in the kitchenand told her “Guess what Mrs. Mitchell? Roy Eldridge is downstairs in my room he stayed with me last night. Can you believe he is the star of the Gene KrupaBand and he couldn’t even stay at the hotel with the rest of the band becausehe is black?” Mrs. Kate Mitchell knew all about Roy Eldridge as she was aware of all the famous musicians at the time. Having two sons, Lou (trumpet) and Andy (trombone) she knew all about the existence of the music greats at the time: Ellington, the Dorsey Brothers , Goodman, Armstrong and so on…She asked me, “What do you think he would like for breakfast?” How about yourscrambled eggs cooked in the great Mitchell Olive Oil and bacon would be good.

I went downstairs to get Roy and as we started up the stairs, which was onthe out side of the house, there were some large Pyracantha shrubs full oforange berries. This was Roy’s first time in California and he looked at

the little orange berries and said, ” Man! look at the baby oranges.” Wehad a nice breakfast with Mrs. Mitchell then took Roy to join the rest ofthe band as they were to continue on to their next engagement .

The difficulties of a black musician traveling with a white band during aracist period hurt him as did some of the incidents that occurred duringhis stay with the Artie Shaw Orchestra 1944-1945, but the music during both stints

was memorable. He toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic and a successfulstay in France during the years 1950-1951. He recorded steadily for NormanGranz in the 1950’s. On Jazz at the Philharmonic he battled the famous trumpeters

Charlie Shavers and Dizzy Gillespie and teamed up with Coleman Hawkins tenorsax great in a quintet. Roy Eldridge in the 1960’s put in a time with theCount Basie Band.

After my meeting with Eldridge in Sacramento in 1941 I didn’t see Roy untilhe came to San Francisco in the late 1960’s. He was Ella Fitzgerald’s conductor,manager, and trumpet star. They were in the Venetian Room of the FairmontHotel. I went over to see them and when Roy saw me he hugged me and toldElla about me and my putting him up for the night when he couldn’t get aroom at the same hotel as the rest of the band.

It was just before showtime and Roy walked me across the dance floor to asingle table in front of the bandstand to see Ella’s show. We know she is great. After her show she brought me her autographed picture, which I still

have hanging up on my family room wall.

Roy continued on thru the 1970’s . Only a serious stroke in 1980 was able to halt his horn. Roy Eldridge recorded throughout his career for virtually

every label.

Roy passed away on February 26, 1989 at Valley Stream N.Y.

Roy Eldridge started out playing trumpet and drums in carnival and circus bands. With the Nighthawk Syncopators he received a bit of attention by playing a note-for-note re-creation of Coleman Hawkins' tenor solo on "The Stampede." Inspired by the dynamic playing of Jabbo Smith (Eldridge would not discover Louis Armstrong for a few years), Eldridge played with some territory bands including Zack Whyte and Speed Webb and in New York (where he arrive in 1931) he worked with Elmer Snowden (who nicknamed him "Little Jazz"), McKinney's Cotton Pickers, and most importantly Teddy Hill (1935). Eldridge's recorded solos with Hill, backing Billie Holiday and with Fletcher Henderson (including his 1936 hit "Christopher Columbus") gained a great deal of attention. In 1937 he appeared with his octet (which included brother Joe on alto) at the Three Deuces Club in Chicago and recorded some outstanding selections as a leader including "Heckler's Hop" and "Wabash Stomp." By 1939 Eldridge had a larger group playing at the Arcadia Ballroom in New York. With the decline of Bunny Berigan and the increasing predictability of Louis Armstrong, Eldridge was arguably the top trumpeter in jazz during this era.

During 1941-1942 Eldridge sparked Gene Krupa's Orchestra, recording classic versions of "Rockin' Chair" and "After You've Gone" and interacting with Anita O'Day on "Let Me Off Uptown." The difficulties of traveling with a White band during a racist period hurt him, as did some of the incidents that occurred during his stay with Artie Shaw (1944-1945) but the music during both stints was quite memorable. Eldridge can be seen in several "soundies" (short promotional film devoted to single songs) of this era by the Krupa band, often in association with O'Day, including "Let Me Off Uptown" and "Thanks for the Boogie Ride." He is also very prominent in the band's appearance in Howard Hawks' Ball of Fire, in an extended performance of "Drum Boogie" mimed by Barbara Stanwyck, taking a long trumpet solo -- the clip was filmed soon after Eldridge joined the band in late April of 1941, and "Drum Boogie" was a song that Eldridge co-wrote with Krupa.

Eldridge had a short-lived big band of his own, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic, and then had a bit of an identity crisis when he realized that his playing was not as modern as the beboppers. A successful stay in France during 1950-1951 restored his confidence when he realized that being original was more important than being up-to-date. Eldridge recorded steadily for Norman Granz in the '50s, was one of the stars of JATP (where he battled Charlie Shavers and Dizzy Gillespie), and by 1956, was often teamed with Coleman Hawkins in a quintet; their 1957 appearance at Newport was quite memorable. The '60s were tougher as recording opportunities and work became rarer. Eldridge had brief and unhappy stints with Count Basie's Orchestra and Ella Fitzgerald (feeling unnecessary in both contexts) but was leading his own group by the end of the decade. He spent much of the '70s playing regularly at Ryan's and recording for Pablo and, although his range had shrunk a bit, Eldridge's competitive spirit was still very much intact. Only a serious stroke in 1980 was able to halt his horn. Roy Eldridge recorded throughout his career for virtually every label.

Roy Eldridge

Roy Eldridge

Roy David Eldridge was a jazz trumpet player in the Swing era. His sophisticated use of harmony, including the use of tritone substitutions, resulted in him sometimes being seen as the link between Louis Armstrong-era swing music and Dizzy Gillespie-era bebop. Roy's rhythmic power to swing a band was a dynamic tradmark of the Swing Era.

Eldridge was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Eldridge played in the bands of Fletcher Henderson, Gene Krupa and Artie Shaw before making records under his own name. He also played in Benny Goodman's and Count Basie's Orchestras, and co-led a band with Coleman Hawkins.

Also known as “Little Jazz” Roy Eldridge was a fiery, energetic trumpeter who although short in stature was a larger-than-life figure in the jazz trumpet lineage. Stylistically speaking he was the bridge between the towering trumpet stylists Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie. One of a significant number of jazz greats from the city of Pittsburgh, Roy’s first teacher was his alto saxophonist older brother Joe. Some of the great rhythmic drive of Eldridge’s later trumpet exploits could be traced to his beginnings on the drums, which he began playing at age six. His first professional work came at age 16 when he worked with a touring carnival, playing drums, trumpet, and tuba.

As a trumpeter Roy had come under the spell of Louis Armstrong’s irrisistable style. Among his earliest band affiliations were Oliver Muldoon, Horace Henderson, Zack Whyte, Speed Webb, and his own band, under the banner of Roy Elliott and his Palais Royal Orchestra. In 1930 he made the move to New York and headed straight to Harlem, where he gained work with a number of dance bands, among which was the Teddy Hill band. He left New York in 1934 to join the Michigan-based McKinney’s Cotton Pickers alongside such significant players as tenor man Chu Berry. Roy returned to New York to rejoin Teddy Hill in 1935, with whom he made his first recordings as a soloist in 1935. Prior to recording with Hill he toured with the Connie’s Hot Chocolates revue. After he left Hill’s band he became the lead trumpeter in Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra where his upper register abilities were highlighted. It didn’t take long for Eldridge to exert himself as a bandleader, forming his own octet in 1936 in Chicago; a band which included his brother Joe.

Eldridge recorded with the Three Deuces group, then left music for a short time to pursue radio engineering, an interesting twist considering his Chicago group’s nightly radio broadcasts. By the end of the 1930s after freelancing with such a wide array of bands Eldridge had gained notice as one of the swing bands’ most potent soloists. In 1941 he joined drummer Gene Krupa’s band. Not only did he provide trumpet fireworks for Krupa’s outfit he also sang, recording a memorable duet with the band’s female singer, Anita O’Day (NEA Jazz Master 1997) on the tune “Let Me Off Uptown” in 1941. Later, after Krupa’s band disbanded in 1943, and a period of freelancing, he toured with the Artie Shaw band in 1944. After Shaw it was time for Roy to lead his own big band, though economics forced him back to small swing groups.

In 1948 Norman Granz recruited Eldridge for his Jazz at the Philharmonic, an ideal situation for Roy since he was one of the ultimate jam session trumpeters. He toured briefly with Benny Goodman and took up residence in Paris in 1950, where he made some of his most successful recordings. He returned to New York in 1951 and continued freelancing with small bands, including work with Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Ella Fitzgerald, and Johnny Hodges. He made notable albums for Verve Records alongside Hawkins and continued freelancing and leading a house band at Jimmy Ryan’s club in New York. In 1980 he was felled by a stroke but that didn’t cut off his musicality. Disabled from the rigorous demands of playing the trumpet, Eldridge continued to make music as a singer and pianist until his 1989 passing.

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/roy-eldridge

NEA Jazz Masters

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-02-28-ca-691-story.html

‘Little Jazz’ Left His Mark as a Giant

by Leonard Feather

February 28, 1989

Los Angeles Times

When Roy (Little Jazz) Eldridge died on Sunday, it was obvious, whatever the official cause of death, that he was the victim of a broken heart. His wife of 53 years, Viola, had recently died, and Eldridge, 78, felt he had nothing to live for. (In a bizarre coincidence, Eldridge’s cousin Reunald Jones Sr. also died Sunday in Los Angeles. He, too, was 78 and played trumpet in many name bands.)

Eldridge had been forced to put down his trumpet forever after suffering a stroke in 1980, and had been seen publicly since then only in occasional appearances singing and playing drums.

My first exposure to Eldridge was a magical evening in 1936 at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom; he was with Teddy Hill’s memorable band, with saxophonist “Chu” Berry as the other principal soloist.

Because Eldridge was unknown then, having made almost no records, his unique, searing sound and impassioned style came as a revelation. After he and Berry joined the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra he began to achieve recognition as the first major trumpet influence since Louis Armstrong.

In Chicago, in 1938, Roy played at the Three Deuces with an incredible small band. Art Tatum was at the piano; John Collins was the guitarist, Zutty Singleton the drummer. This was Swing era combo music at its supreme level.

In May, 1940, Milt Gabler and I produced a session for Commodore Records with Eldridge, Benny Carter and Coleman Hawkins in the front line. Roy’s solos in this intimate setting became classics that have been reissued time and again.

He played alongside Louis Armstrong for their first joint appearance in the Esquire Allstars concert at the Metropolitan Opera House. Roy’s disposition always seemed happy and outgoing; it was not until after his later experiences with Jim Crow that bitterness surfaced.

He was the only black musician in Gene Krupa’s band from 1941-43, one of several blacks in an all-star band on Mildred Bailey’s CBS radio series in 1943-44, then became the only black with Artie Shaw’s band in 1945.

After he left Shaw he told me of his humiliating experiences.

“As long as I’m in America,” he said, “I’ll never work in a white band again! It all goes back to when I joined Gene Krupa. It thrilled me to be accepted as a regular member of the band, but I knew that all eyes were on me to see if I’d do anything wrong.

“All the guys in the band were nice, Gene especially. Then we headed for California and the trouble began. We arrive in one town and the rest of the band checks in. I can’t get into their hotel, so I keep my bags and start looking for another place. I get to where someone is supposed to have made a reservation for me; then the clerk sees me, suddenly discovers that a regular tenant just arrived and took the last available room. I lug my dozen pieces of luggage back onto the street and start looking again.

“By the time that kind of thing has happened night after night, it begins to work on my mind; I can’t think right, I can’t play right. When we finally got to the Palladium in Hollywood, I had to watch who I could sit at tables with. If they were movie stars who wanted me to come over, that was all right; if they were just the jitterbugs, no dice. And all the time the bouncer with his eye on me, just watching for a chance....

“I had to live way out in Los Angeles, while the rest of the guys stayed in Hollywood. It was a lonely life. One night the tension got so bad I flipped. I started trembling, ran off the stand and threw up. They carried me to the doctor’s. I had 105 (degree) fever; my nerves were shot.

“When I went back a few nights later, I heard that people had been asking for their money back because they couldn’t hear ‘Let Me Off Uptown.’ This time they let me sit at the bar.

“Later on, when I was with Artie Shaw, I went to a dance date and they wouldn’t even let me in the place. ‘This is a white dance,’ they said, and there was my name right outside. I told them who I was. When I finally did get in, I played that first set, trying to keep from crying. By the time I got through the set, the tears were rolling down my cheeks. I went up to a dressing room and stood in a corner crying and saying to myself why the hell did I come out here again when I knew what would happen.

“Artie came in and he was real great. He made the guy apologize that wouldn’t let me in, and got him fired.

“Man, when you’re on the stage, you’re great, but as soon as you come off, you’re nothing. It’s not worth the glory, not worth the money, not worth anything. Never again!”

Happily, Eldridge did not have to live up to his resolution. Conditions improved a little, and by 1949 he was back in the Krupa band. The following year he worked with Benny Goodman, touring Europe, then stayed on the Continent playing with everyone from Sidney Bechet to Charlie Parker and recording, among other things, a delightful blues vocal in French, “Tu Disais Que Tu m’Aimais.”

Much of the rest of his playing career was with mixed bands, most notably on tour with Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic (named for Los Angeles’ Philharmonic Auditorium). He also co-led a quintet with Coleman Hawkins.

Roy Eldridge was to the evolution of jazz trumpet in the 1930s and early ‘40s what Armstrong had been in the ‘20s, and what Dizzy Gillespie would be from the mid-'40s, what Miles Davis would be in the ‘50s. He recorded with everyone from Art Tatum and Harry (Sweets) Edison and Oscar Peterson and Bud Freeman, with a string ensemble with a Dixieland band.

How it must have rankled him, during those last eight years when playing was forbidden to him, to see so many avenues opening up. What a joy it would have been to share his company, and his sound, at the jazz parties and on the jazz cruises. The last time we talked, a year ago, he sounded as cheerful as ever. If he was laughing on the outside and still crying on the inside, he did a magnificent job of concealing it.

Ave atque vale, Little Jazz.

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-02-27-mn-399-story.html

Jazz Great Roy Eldridge, Innovator on Trumpet, Dies

by Kenneth Reich

February 27, 1989

Los Angeles Times

Roy Eldridge, one of the great innovators on the jazz trumpet, died Sunday in New York at the age of 78.

Eldridge’s passing in a hospital in Valley Stream, Long Island, came just three weeks after the death of his wife of 53 years, Viola.

“He just stopped eating and wanted to die,” said a friend of the musician.

In naming him a member of his “greatest All-Star Jazz Band” several years ago, Times jazz critic Leonard Feather wrote:

“Roy Eldridge has often been called the link between (Louis) Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, but he was much more. To what Armstrong had contributed he added many new elements: longer, crackling, fiery phrases, sudden upward and downward movements, growling guttural sounds and often a sense of intensity that surpassed even Armstrong’s.”

It was in the 1930s and ‘40s that the trumpeter reached the high point of his career, but at a time of great difficulty for black musicians. When he left Artie Shaw’s band in 1945, he complained bitterly about many racial incidents while on tour and declared that he could never again play with a white band, even though Shaw, personally, had been nice to him.

Later, however, he did play with many such bands as segregation faded.

Born David Roy Eldridge in Pittsburgh, Pa., on Jan. 30, 1911, Eldridge studied with his elder brother, the late Joe Eldridge, playing the drums and appearing publicly for the first time at the age of only 6. Later, he got much early experience playing the horn at carnivals.

Coming to New York City in 1930, he worked in Cecil Scott’s band and later with the Elmer Snowden Band at Smalls, then with Teddy Hill, Connie’s Hot Chocolates, Fletcher Henderson and Mal Hallett, performing often as a soloist and occasionally organizing his own bands.

Eldridge became nationally prominent as the featured trumpeter and singer with Gene Krupa’s band from 1941 to 1943, at the same time becoming one of the first black jazz musicians to be accepted as a permanent member of the brass section of a white band.

After ending his tour with Shaw, he served a long stint with Norman Granz’s Jazz at the (New York) Philharmonic.

In 1950, with some saying he had become old-fashioned, he joined the Benny Goodman sextet for a European tour and remained on the Continent for 18 months. He was a great hit in France, where he made some of his most famous recordings.

Returning to the United States in 1951, he became part of the mainstream jazz movement, frequently appearing in small groups with Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges, Ella Fitzgerald and Coleman Hawkins.

Described by music magazine editor Barry Ulanov as “a biting, driving brass man, almost without equal for sheer power from the earliest years of swing,” he was known for an exuberant personality and a keen sense of competition.

Even in his later years, he enjoyed challenging younger musicians to cutting contests, according to Groves Dictionary of Jazz.

Groves said that Eldridge drew his main inspiration not from Armstrong but from the saxophonists Carter and Hawkins, “whose fleet arpeggio style and rich tone he adapted to his instrument. As a result, Eldridge early acquired a keen awareness of harmony, an unprecedented dexterity, particularly in the highest register, and a full, slightly overblown timbre, which crackled at moments of high tension.”

He also had a formative impact on early bop musicians, and his work in swing had particular influence over Gillespie, with whom he competed in a series of “trumpet battles” at Minton’s in the early 1940s.

By the late 1950s, Eldridge was alternating between fluegelhorn and trumpet. He was an adequate performer on piano, bass and drums. As a singer, he had what is described as a “personable, gruff quality,” and his best-known song was “Let Me Off Uptown,” a duet with Anita O’Day.

Eldridge, who lived in Queens, N.Y., is survived by a daughter, Carol.

Funeral arrangements were incomplete.

Friday, March 25, 2016

"The Excitable Roy Eldridge" by Gary Giddins

© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

The editorial staff at JazzProfiles wouldn’t dream of denying Gary Giddins his “Challah and butter,” but we hope he won’t mind too much if we use the following excerpts from Rhythm-a-ning: Jazz Tradition and Innovation to fulfill a long-standing wish to feature something about trumpeter Roy Eldridge on these pages.

If you haven’t cozied up to Gary’s storytellings, you might want to start with a copy of Rhythm-a-ning: Jazz Tradition and Innovation.

You can locate more information about this book and others that Gary has written by visiting him at www.garygiddins.com.

Thankfully, many of the recordings that Roy recorded over the span of his career for Norman Granz at Mercury and later for Norman’s own labels - Clef, Norgran and Verve - are still available as commercial CD’s and Mp3 download. You can locate a comprehensive listing of his output by going here.

The Excitable Roy Eldridge

“Through much of its history, jazz made avid converts with the simple promise of undying excitement, whether maximized by throbbing rhythms, blood-curdling high notes, violent polyphony, layered riffs, hyperbolic virtuosity, fevered exchanges, or carnal funk. Yet excitement often gets a bum rap from those converts who, having mined the music's deeper recesses, suspect all crowd-pleasing gestures of vulgarity. At bottom, the distinction between the two is subtle but clear: if you like it, it's exciting; if not, it's vulgar. As Sidney Bechet noted, "You got to be in the sun to feel the sun. It's that way with music too." If you're cold to a musician's impassioned yowling, that passion will seem awfully dim if not aimless, and since crowds more than individuals thrive on excitement, your response to musical rabble-rousing may depend on your willingness to get lost in a crowd.

The showiest expressions of passion frequently border on outright pandering, but immoderation of that sort is a healthy symptom — it tends to proliferate in a milieu where authentic excitement also flourishes. Over the past decade, excitement has been scarce to a degree that not even the spaciest '50s cool-jazz hipster could have anticipated, while vulgarity continues unabated in its new garb, substituting pretentious meditation for caterwauling. Still, that part of the audience that hasn't been rendered insensible by ECM-styled stabiles of sound, in which slowness indicates profundity, hungers for le jazz hot, as witness the gratitude with which it greets the appended swing theme that, in so many contemporary performances, caps an hour's worth of esoteric clamor. …

[Roy] Eldridge ... [one of the most] … electrifying of jazz trumpeters first came to prominence in the '30's with a flashy, passionate, many-noted style that rampaged freely through three octaves, rich with harmonic ideas and impervious to the fastest tempos. In part, his secret was to transfer ideas patented on the more facile tenor saxophone to the trumpet; his ability to play Coleman Hawkins's solo on Fletcher Henderson's 1926 "Stampede" got him his first job, and more than a decade later, when Hawkins, lording it in Europe, heard the first Eldridge recordings, he vowed to work with the younger man when he returned to the States ….

The decade preceding the emergence of bop was rife with frantic, exhilarating trumpeters. After the war, the tenor sax would assume that role of crowd pleaser, honking and moaning like a Baptist who'd just heard the word. But in the '30s and early '40s Louis Armstrong's instrument was still king, and while many of its best practitioners pursued the course of lyrical composure (among them Buck Clayton, Bobby Hackett, Bill Coleman, Harry Edison, and Doc Cheatham), others—Eldridge, Red Allen, Bobby Stark, Hot Lips Page, Charlie Shavers, Shad Collins, Rex Stewart—strove for an agitated, coruscating approach as thrilling as anything heard in American music. If they were more likely to overstep the bounds of good taste, there was a payback — they took the most expressive risks. Eldridge was the most emotionally compelling, versatile, rugged, and far-reaching. His ballads were complicated but stirringly lucid, and his bravura numbers were played with such bracing authority that they dwarfed the competition. To a young Dizzy Gillespie, "He was the Messiah of our generation."

In one way or another, Armstrong fathered all the trumpeters mentioned above. Eldridge started listening to him in 1931, at twenty, taking cues from his dramatic storytelling intensity, his logic, his gleaming high-note flourishes. ...

Nor were Eldridge's high notes rounded like Armstrong's. Instead, shaded by a rapid shake, they seemed a spontaneous, un-containable explosion of feeling. …. His high notes were never merely high; and rather than concluding performances, they tended to prefigure fiery parabolas of melody. Orson Welles once explained that the screaming white cockatoo in Citizen Kane was inserted to keep the audience alert. Eldridge's expressive cries and banshee whistles serve the same purpose, telegraphing his own excitement…”

If you have never seen a 78 rpm [revolutions per minute] record in action, then you are sure to enjoy the following video which features Roy’s very exciting original 78 rpm version of After You’ve Gone as played on a Victrola.

Roy Eldridge: The 'Little Jazz' Centennial

Trumpeter Roy Eldridge's legendary sound and bravado dwarfed his 5'6" frame. Known as "Little Jazz," and later just "Jazz," his nicknames befit his devotion (five decades) to the art form. His peers spoke of his soulful style and great competitiveness, not to mention his ridiculous chops. These qualities marked him as one of the greatest trumpet kings of all time; he reigned from the late 1930s and beyond, when many other top trumpeters came into the fold.

But Eldridge's legend endured. He was an innovator who, for many historians, conveniently bridged the gap between Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie in jazz's evolutionary chain. This may be hyperbole or an oversimplification, but many agree that Eldridge modernized the way to play jazz. And nobody ever discounted the red-hot passion that once crackled from his brass. On Jan. 30, Eldridge would have been 100, so we celebrate The Little Jazz Centennial with some of his fieriest early performances.

Roy Eldridge: The 'Little Jazz' Centennial

Let Me Off Uptown

- from Uptown

- by Roy Eldridge with Gene Krupa and Anita O'Day

After You've Gone

- from Black Legends Of Jazz: The Original Decca Recordings

- by Roy Eldridge and His Orchestra

Rockin' Chair

- from Uptown

- by Roy Eldridge with Gene Krupa and Anita O'Day

Hear "Rockin' Chair" on A Blog Supreme.

Blue Moon

- from Roy and Diz

- by Roy Eldridge

Bean Stalkin'

- from Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge at the Opera House

- by Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge

https://www.nytimes.com/1981/06/30/arts/roy-eldridge-s-ambition-to-outplay-anybody.html

ROY ELDRIDGE'S AMBITION:

'TO OUTPLAY ANYBODY'

by John S. Wilson

EIGHT

months ago Roy Eldridge, the jazz trumpeter, who is often spoken of as a

bridge between Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, suffered a heart

attack that has kept him from playing since then. But, like Mr.

Armstrong and Mr. Gillespie, Mr. Eldridge is also a singer - his duet

with Anita O'Day on ''Let Me Off Uptown'' was one of his most memorable

singing performances.

So tonight, when

a musical ''Portrait of Roy Eldridge'' is presented at Town Hall as

part of the Kool Jazz Festival, Mr. Eldridge will be on hand to

contribute some authentic touches to the portrait by singing a few

songs. But he is not yet ready to play his horn again.

''Since

I had the heart attack,'' he said a few days ago, ''I've been working

around the house, listening to police calls on the radio. But I don't

dabble in music. I don't want to get hung up on it and start yearning.''

'Have to Start Right'

Mr. Eldridge,

who was 70 years old in January, appears very fit and vigorous and talks

with the bubbling energy that has always been characteristic of him.

''When

I get ready to go back, I'll know it,'' he said confidently. He paused,

and then added: ''And I think I'm getting ready. I'm beginning to

listen. I've got a tape of Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five in my car,

and I play it whenever I go someplace.''

''But,

to play again, I first got to make sure that my teeth are straight,''

he continued. ''When you don't play for a long time, you have to start

right to get yourself back together. So I'll have my teeth checked. Then

I'll take the fluegelhorn and try to get a sound out of it. Then for a

week or two I might play some songs or jam a little bit.''

Although

Mr. Eldridge will not be playing songs or jamming at tonight's concert,

some of his friends and admirers will perform a few of the Eldridge

classics. Jimmy Maxwell, the trumpeter, will play Mr. Eldridge's

treatment of ''Rockin' Chair'' and Lee Konitz will adapt Mr. Eldridge's

''Body and Soul'' to the saxophone - a not surprising transformation,

because one of Mr. Eldridge's primary inspirations is Coleman Hawkins,

the tenor saxophonist (''The best cat I ever worked with,'' Mr. Eldridge

says) and he continues to have special admiration for such saxophonists

as Ike Quebec, Eddie (Lockjaw) Davis and Zoot Sims, who will be on the

program tonight. 'I Thought It Was Me'

However,

several trumpet men in addition to Mr. Maxwell will contribute to the

portrait of Mr. Eldridge - Clark Terry, Johnny Letman, Jon Faddis and

Dizzy Gillespie, who will both play and reminisce about Mr. Eldridge.

Mr.

Eldridge has one particularly poignant memory of Mr. Gillespie, who got

his first important job in the 1930's with Teddy Hill's band at the age

of 19 because, Mr. Gillespie has admitted, ''I sounded so much like

Roy.'' Mr. Eldridge first became aware of Mr. Gillespie when he heard

Lionel Hampton's 1939 recording of ''Hot Mallets.''

''I

heard this trumpet solo and I thought it was me,'' Mr. Eldridge said.

''Then I found out it was Dizzy. ''I was never trying to be a bridge

between Louis Armstrong and something,'' he said, referring to

references to him as the connecting link between Mr. Armstrong and Mr.

Gillespie. ''I was just trying to outplay anybody, and to outplay them

my way.''

Tonight's ''Portrait'' will

also include orchestral transcriptions of celebrated Eldridge

recordings, some of which were transcribed by Dick Hyman for a tribute

to Mr. Eldridge by the New York Jazz Repertory Company, one of several

tribute concerts of which he has been the subject in recent years. They

will be played by an orchestra led by the saxophonist Budd Johnson. In

the course of these recent tributes, Mr. Eldridge has heard numerous

groups and individuals play the solos that he created. 'To Me, It's All

Music'

''But the only time it got to

me,'' he said, ''was at the New York School of Music. I was rehearsing

''Body and Soul'' with the school's band. I played the first part. Then I

made my break and the whole brass section played my chorus. They had

the whole flavor of it. It touched me. I got so choked up I couldn't

rehearse any more.''

Mr. Eldridge had

been leading the band at Jimmy Ryan's for 11 years when he had his heart

attack last year. Jazz followers were amazed when Mr. Eldridge went

into Ryan's, which has always been a home of Dixieland and traditional

jazz, styles that Mr. Eldridge has never been associated with.

''People

would say, 'What's he doing there?','' Mr. Eldridge recalled. ''To me,

it's all music. I learned how to play bar mitzvahs - I did it for eight

years at Long Beach. Forty years ago, when I took my band into the

Arcadia ballroom, where we had to play tangoes and Viennese waltzes, I'd

never played tangoes or waltzes. I learned on the job.

''So

at Ryan's I got into 'High Society' and 'Tin Roof Blues' and the

standard Dixieland things. I learned that first. Then I started getting

some of my own things in. We used to practice in the basement. There's a

cat that's lived down there for eight years. It's never been outside

but it comes up to listen to the music.''

''The

job turned out nice,'' he reflected. ''I can go out and come back when I

want to. When I go out, I play a lot in Europe and Japan, and when

people who heard me there come to New York, they come to Ryan's because

we play what they want to hear.

''And I can pace myself the way I want. I don't have to start right out screaming.''

A version of this article appears in print on , Section C, Page 5 of the National edition with the headline: ROY ELDRIDGE'S AMBITION: 'TO OUTPLAY ANYBODY'. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

ROY ELDRIDGE:

JAZZ TRUMPETER FOR ALL DECADES

by John Wilson

Roy

Eldridge's feisty, crackling trumpet has been silent since he had a

heart attack two years ago. At the age of 71, he now seems fit, vigorous

and energetic but he has not resumed playing his horn since that

illness. But if this has cut off the possibility of hearing Mr. Eldridge

in person, it has finally inspired record producers to bring together

the kind of overviews of his recorded work that have not been accorded

to him before - the kind of collections that we have of the works of

such jazz stars as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Bix

Beiderbecke, Jelly Roll Morton, Benny Goodman, Jack Teagarden and Woody

Herman as well as Fletcher Henderson, Gene Krupa and Artie Shaw, in

whose bands Mr. Eldridge played.

Three

Eldridge collections have recently been issued - a single disk in MCA's

''Jazz Heritage'' series, ''All the Cats Join In,'' MCA 1355, largely

devoted to his performances with big studio bands in 1945 and 1946; a

two-disk album, ''Roy Eldridge - The Early Years,'' Columbia C2 38033, a

sampling of his work between 1935 and 1949 with Teddy Hill's band, his

own small group, as accompanist to Billie Holiday and Mildred Bailey and

with Gene Krupa's orchestra; and a four-disk album split between Mr.

Eldridge and Mr. Armstrong, ''Louis Armstrong - Roy Eldridge/Jazz

Masterpieces,'' the first in a mail order series, ''The Greatest Jazz

Recordings of All Time,'' produced by the Institute of Jazz Studies and

distributed by the Franklin Mint Record Society.

The

new Franklin Mint series appears to be an attempt to parallel

Time-Life's excellent ''Giants of Jazz'' series which has already issued

21 volumes. In the Time-Life series, three disks are devoted to each

''Giant,'' as opposed to Franklin Mint's two and the biographical and

discographical notes are lengthier. However, Time-Life has not done an

Eldridge album and apparently has no immediate intention of doing one, a

pointed instance of the way in which Mr. Eldridge has been passed over

until now.

Although there is some

duplication between Columbia's two-disk Eldridge set and Franklin Mint's

two disks, the point of view of the two albums (and, one presumes, the

availability of records) is different. Columbia, limited to records that

come from its own catalogue, concentrates on Mr. Eldridge's eight-piece

band of 1937 (seven cuts) and his work with Mr. Krupa's orchestra,

which takes up two of the set's four sides. The Franklin Mint disks are

more wide ranging, starting, as the Columbia does, with a Teddy Hill

record of 1935 and including, along with Mr. Eldridge's octet and Mr.

Krupa's band, selections with the bands of Fletcher Henderson and Artie

Shaw and a variety of performances from the mid-40's to the mid-60's

with groups that include Oscar Peterson, Benny Carter and Coleman

Hawkins.

Hearing

Mr. Eldridge over three decades in this fashion, one is impressed by

the consistent level of his playing under all kinds of circumstances and

the fact that, within an identifiable sound and style, he continued to

find fresh ideas. He has always been a musician who responds to

challenge, whether the challenge came from others or from himself. For

years he has been described as the bridge between Louis Armstrong and

Dizzy Gillespie but, as Mr. Eldridge once said, ''I was never trying to

be a bridge between Louis Armstrong and something.''

''I

was just trying to outplay anybody,'' he explained, ''and to outplay

them my way.'' His way bristled with nervous intensity. It had an

electricity that was quite different from Mr. Armstrong's grand

theatricality or Mr. Gillespie's dazzling eruptions. Mr. Eldridge

provided a classic definition of the difference between his playing and

that of Mr. Armstrong on a 1951 duet with the French pianist, Claude

Bolling, on ''Fireworks'' (included in the Franklin Mint set) in which

Mr. Eldridge plays a chorus that is pure Armstrong and follows it with a

brilliant demonstration of his own passionate, driving development.

Most

of the major jazz stars have hit a peak relatively young and then

settled on that peak for the rest of their careers. But Mr. Eldridge,

like Coleman Hawkins, the tenor saxophonist, hit an early peak and then

kept on going, getting better as he got older. The fact that there was

no stopping Mr. Eldridge's growth as time went by is one of the

revealing aspects of the Franklin Mint set, a revelation that simply

underlines the basic excitement of his individual performances.

But

Mr. Eldridge is not all speed and brilliance. His ripping, cutting

attack on open horn is balanced by his virtuosity with a mute. The

intensity of his muted playing builds brilliantly on a blues, ''Dale's

Wail,'' and soars in tandem with Benny Carter's alto saxophone on Mr.

Carter's tune, ''I Still Love Him So.'' His peppery energy is

transferred to the piano on ''Wailing'' and gives a buoyant lift to

''School Days'' that removes this children's song from the mincing

mockery that Mr. Gillespie brought to it.

All

of these selections are in the Franklin Mint set as well as a sampling

of his sensitivity as an accompanist as he backed Billie Holiday on

''What Shall I Say?'' The Holiday song is also in the Columbia

collection along with an even lovelier bit of backing on Mildred

Bailey's ''I'm Nobody's Baby'' on which he plays into a felt hat to fill

out the soft warmth of its tone.

Some

of the best selections on the Columbia set are repeated in the Franklin

Mint collection - ''After You've Gone,'' ''Heckler's Hop'' and ''Wabash

Stomp'' by Mr. Eldridge's 1937 band and ''Rockin' Chair'' with Mr.

Krupa's band. The Columbia album also includes two of his other major

pieces with Mr. Krupa, ''Let Me Off Uptown'' which he sings with Anita

O'Day, and a big-band version of ''After You've Gone.''

But

there are some performances by the Krupa band in the Columbia set that

are inexplicable except as a demonstration that nothing daunts Mr.

Eldridge. Given a mere eight-bar solo after Miss O'Day has labored

through the dismal lyric of ''Massachusetts,'' he manages to make them

seem as vital and important as three powerful choruses. When he is

surrounded by the nonsense of such World War II trivia as ''Harlem on

Parade'' or ''The Marines Hymn'' (sung by a very lightvoiced Johnny

Desmond), one can appreciate the skill with which he rescues these

pieces from being total dross, but they are scarcely worth the effort he

puts into them.

A version of this article appears in print on , Section 2, Page 25 of the National edition with the headline: ROY ELDRIDGE:JAZZ TRUMPETER FOR ALL DECADES. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

https://jerryjazzmusician.com/2015/01/roy-eldridge-story/

A Roy Eldridge story

January 30, 2015

Happy Birthday #104 to Roy Eldridge, who in addition to being one of

the great trumpet players of his time, is known as the “bridge” between

Armstrong and Dizzy.I loved the brightness of his playing, and for

contributing to one of the great moments in jazz — his vocal duet with

Anita O’Day, leading into a seldom-in-a-generation trumpet solo on “Let

Me Off Uptown.”

When I was a kid, my dad used to tell me stories about his friendship

with “Eldridge,” and in particular one eventful experience he had while

he was traveling with his band in Pennsylvania. In 1998, two years

before his passing, my father wrote this piece for Jerry Jazz Musician about this very special experience in his life. I hope you enjoy his telling of it…

___________

My name is Joe Maita, Sr. I am 81 years old and was a musician formany years. This is about my experience meeting and knowing the great trumpet player Roy Eldridge.

Roy was born on January 30, 1911 in Pittsburgh Pa. One of the most exciting trumpeters to emerge during the swing era, Roy Eldridge’s combative approach, and strong musicianship were an inspiration and influence to the next musical generation, most notably Dizzy Gillespie. Although he sometimes pushed himself farther than he could go, Eldridge never played a dull solo.

Roy Eldridge started out playing trumpet and drums in carnival & circusbands. He would not discover Louis Armstrong for a few years. He worked with bands of Zack Whyte and Speed Webb in 1931. He worked with Elmer Snowdenwho nicknamed him “Little Jazz” also McKinney’s Cotton Picker’s and most importantly Teddy Hill in 1935. Eldridge recorded solos with Hill backing Billie Holiday and with Fletcher Henderson including his 1936 hit, “Christopher Columbus” gained a great deal of attention. In 1937 he appeared with his octet with his Brother Joe on Alto Sax at the Three Deuces Club in Chicago. His group recorded some outstanding selectionsas a leader, including: “Heckler’s Hop” & “Wabash Stomp”.

The Summer of 1938, I was playing with the Joaquin Grill Orchestra at the Willows at Oakmont Pa. on the Allegheny River. One night after we finished playing at 1:00 a.m. my friends, Louis Mitchell trpt. and Cliff Fishbackour arranger and piano player, decided to go into Pittsburgh about 15 milesaway to a Jazz Club . It was a place where some of the local jazz playerswould go to jam. It all would start late at night and could go on till thewee hours of the morning. We arrived around 1:45 a.m. and the place was nothingmuch to look at. We walked up a full flight of stairs and our ears told usthat we arrived at the right place. It was jumping with some great sounds.

As we walked into the room where all the music was coming from, we couldn’t see a thing because the room was filled with cigarette smoke. As we lookedaround for a place to sit, the band started up again. It sounded fine, but when the trumpet player started up we realized that it was the great Eldridge. What a surprise. Roy was one of our favorite players and here we were in the same room with him.

Roy Eldridge and his Band had just finished a long engagement at the ‘Three Deuces’ a famous Jazz Club in Chicago. They had a lot of air time broadcasting from that spot and we would always try to hear him whenever we could get near a radio from where ever we would be. He was our favorite jazz player.

We found out that Pittsburgh was his home and that he actually was born there.

It was our luck to walk in on this unexpected treat…. Of course when the music group took a break, we invited Roy over to our table and we had a great time meeting each other and discussing the music business in general…Roy introduced his brother, Joe Eldridge to us at this time. Joe was a fine alto sax man and also arranged music for some of the big

bands. One band he arranged for was Bob Crosby and his Bob Cats, Bing’s

brother, who had a fine band at the time. It was a happy night for all of us and it ended up with Roy inviting us to his house across the river to hear his band rehearse on the next day.

Of course Cliff, Lou and I went to hear the band rehearse at Eldredge’s home the next afternoon. His home was across the Allegheny River in an industrial area near the Heinz Ketchup factory…As we entered Roy’s house we could hear his band playing and it sounded great, even with the smell of ketchup in the air it was a memorable experience…The band sat around in a relaxed manner and without music stands played head arrangements. We enjoyed the day…

We invited Roy and his Brother Joe to our home in Oakmont for a dinner that I would cook. Cliff, Lou and I rented this beautiful brick home for the summer while we were playing the music job at the Willows. I must say that renting this home was probably the best deal anyone could have. It so happened that this elegant home belonged to two elderly women that were going to Europefor the summer and as our engagement at the famous Willows was booked for the summer, we were able to rent this home…It was completely furnishedwith beautiful furniture in all the rooms on two floors and all the dishes, pots and pans, and silverware included for the unheard of sum of $90.00 per month (unbelievable even for 1938.) and linens too…We split the cost 4 ways, Cliff, Lou, myself and Joe Bruhl & wife Vera. As I remember, I think we took good care of the place.

Roy and Joe Eldridge came over for dinner the next afternoon. We enjoyed each others company talking about the music business in general…Roy told me that when he first started playing the trumpet he didn’t even have a trumpet lesson book, but he used his brother Joe’s clarinet music book to learn. We also took several pictures together with our cameras. I servedan Italian dinner that everyone seemed to enjoy.

By 1939 Roy had a larger group playing at the Arcadia Ballroom in New York. With the decline of Bunny Berigan and the increasing predictability of LouisArmstrong, Roy Eldridge was arguably the top trumpet player in jazz during this era

During 1941-1942, Eldridge sparked the GENE KRUPA ORCHESTRA recording a classic version of ‘Rockin Chair’ and ‘After you’ve gone’ and interacting with Anita O’Day on the great recording of “Let Me Off Uptown”.

It was about this time that the Gene Krupa Band was riding on a high as a bandleader, came to Sacramento, California. It was September of 1941 and Krupa’s Band with Anita and Roy were engaged to do a show at the California S

tate Fair. By coincidence I was hired to play in the State Fair Concert Orchestra. It was 3 years since I had seen Roy and I was looking forward to see him again. After I finished my job that night, I went where the Gene

Krupa Band was performing and after they finished their show I went backstageand there was ‘Little Jazz’. It was good to see him and we talked about goingsomewhere to visit. He introduced me to some of the musicians and the famous Anita O’Day. Meanwhile Roy said that the Band members were going downtown to the Senator Hotel where they were going to stay for the night, but becausehe was a black man he would not be able to stay with the rest of the bandand would look around and see where to stay for the night. I said “Roy, you will stay with me.” I know that Roy remembered Lou Mitchell from our meeting in Pittsburgh and told him that I had a place in his family home with Lou’smother, Mrs. Mitchell…Lou was working in the music studios of Hollywood at the time.

Roy said that would be great . We went home and after a good nights rest I went upstairs to the main floor where Mrs. Mitchell would be in the kitchenand told her “Guess what Mrs. Mitchell? Roy Eldridge is downstairs in my room he stayed with me last night. Can you believe he is the star of the Gene KrupaBand and he couldn’t even stay at the hotel with the rest of the band becausehe is black?” Mrs. Kate Mitchell knew all about Roy Eldridge as she was aware of all the famous musicians at the time. Having two sons, Lou (trumpet) and Andy (trombone) she knew all about the existence of the music greats at the time: Ellington, the Dorsey Brothers , Goodman, Armstrong and so on…She asked me, “What do you think he would like for breakfast?” How about yourscrambled eggs cooked in the great Mitchell Olive Oil and bacon would be good.

I went downstairs to get Roy and as we started up the stairs, which was onthe out side of the house, there were some large Pyracantha shrubs full oforange berries. This was Roy’s first time in California and he looked at

the little orange berries and said, ” Man! look at the baby oranges.” Wehad a nice breakfast with Mrs. Mitchell then took Roy to join the rest ofthe band as they were to continue on to their next engagement .

The difficulties of a black musician traveling with a white band during aracist period hurt him as did some of the incidents that occurred duringhis stay with the Artie Shaw Orchestra 1944-1945, but the music during both stints

was memorable. He toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic and a successfulstay in France during the years 1950-1951. He recorded steadily for NormanGranz in the 1950’s. On Jazz at the Philharmonic he battled the famous trumpeters

Charlie Shavers and Dizzy Gillespie and teamed up with Coleman Hawkins tenorsax great in a quintet. Roy Eldridge in the 1960’s put in a time with theCount Basie Band.

After my meeting with Eldridge in Sacramento in 1941 I didn’t see Roy untilhe came to San Francisco in the late 1960’s. He was Ella Fitzgerald’s conductor,manager, and trumpet star. They were in the Venetian Room of the FairmontHotel. I went over to see them and when Roy saw me he hugged me and toldElla about me and my putting him up for the night when he couldn’t get aroom at the same hotel as the rest of the band.

It was just before showtime and Roy walked me across the dance floor to asingle table in front of the bandstand to see Ella’s show. We know she is great. After her show she brought me her autographed picture, which I still

have hanging up on my family room wall.

Roy continued on thru the 1970’s . Only a serious stroke in 1980 was able to halt his horn. Roy Eldridge recorded throughout his career for virtually

every label.

Roy passed away on February 26, 1989 at Valley Stream N.Y.

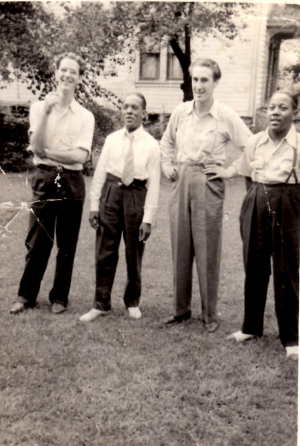

Cliff Fishback, unknown member of Roy Eldridge’s band, Louis Mitchell, and Roy Eldridge

Oakmont, Pennsylvania

Summer, 1938

Photo taken by Joseph Maita, Sr.

Roy Eldridge, 78, Jazz Trumpeter Known for Intense Style, Is Dead

by John S. Wilson

February 28, 1989

New York Times

Roy Eldridge, a jazz trumpeter who was the connecting link in the line that went from the pioneering Louis Armstrong to the modernist innovator Dizzy Gillespie, died Sunday at Franklin General Hospital in Valley Stream, L.I. He was 78 years old.

A nursing supervisor contacted last night at the hospital said she could not reveal details about his death. On Sunday, however, the Rev. John Garcia Gensel of St. Peter's Lutheran Church in Manhattan said Mr. Eldridge ''wasn't eating well. And I know he was very dehydrated.''

Mr. Eldridge, who gave up the trumpet for health reasons in 1980, played with a crackling intensity that set him apart from all his contemporaries.

''Roy took as his point of departure the fantastic style of the middle Armstrong period,'' Ross Russell, a jazz record producer and historian, wrote in 1949. ''But Roy's trumpet went beyond Louis in range and brilliance. It had greater agility. His style was more nervous. His drive was perhaps the most intense jazz has ever known.'' 'More Soul in One Note'

''God gives it to some and not others,'' Ella Fitzgerald once said, speaking of Mr. Eldridge. ''He's got more soul in one note than a lot of people could get into the whole song.''

Mr. Eldridge's first influences on trumpet were Rex Stewart (''I liked his speed, range and power,'' Mr. Eldridge said) and Red Nichols (''I liked the nice, clean sound he was getting''). But he began to find his own musical personality from a saxophonist,

Coleman Hawkins. He copied Mr. Hawkins's sleek driving solo with Fletcher Henderson's orchestra on ''Stampede'' so successfully that it set him apart from other young trumpet players of the late 20's.

''I was very technical then,'' Mr. Eldridge recalled, ''but I couldn't swing. Chick Webb used to say, 'Yeah, he's fast but he's not saying anything.' '

Mr. Eldridge learned to say something when he saw Armstrong for the first time, at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem in 1932.

''I didn't think so much of him at first,'' Mr. Eldridge conceded. ''But I stayed for the second show, and I suddenly realized he built his solos like a book - first, an introduction, then chapters, each one coming out of the one before and building to a climax.'' A Nickname: Little JazzIt was a year before, in 1931, that Mr. Eldridge acquired his nickname, Little Jazz, which stayed with him the rest of his life. His irresistible urge to play impressed Otto Hardwick, a mainstay of Duke Ellington's early saxophone section, when he was playing with Mr. Eldridge at Small's Paradise in Harlem.

''I was blowing all the time,'' Mr. Eldridge recalled. ''So he called me Little Jazz.''

Physically he fit the description. Born in Pittsburgh on Jan. 30, 1911, he was a short, compact and wiry man who was often jumping with energy. He left home at 16 to play with a band called the Night Hawk Syncopaters. Mr. Eldridge paid his dues with a variety of territory bands, sometimes playing drums as well as trumpet, before he reached New York in 1930. A Brash, Crackling Attack

In New York, he combined the fiery virtuosity he had shown playing ''Stampede'' with the insights he had gained from Armstrong to create the brash, crackling attack that became his musical identity.

''I liked to hear a note cracking,'' he later told Barry Ulanov of Metronome magazine. ''A real snap. It's like a whip when it happens.''

In the 30's, Mr. Eldridge formed his own band with his older brother, Joe, a tenor saxophonist. He also played in McKinney's Cotton Pickers, in Teddy Hill's band and in Fletcher Henderson's last great band - the mid-30's Henderson band in which Mr. Eldridge was the most vital spark among such notable artists as Chu Berry, Sid Catlett, Buster Bailey and Israel Crosby.

After another attempt at leading his own band, he announced his retirement from music in 1939, ''because I couldn't get any bread.''

He studied radio engineering and electronics, but, he said, ''I couldn't do it.'' By 1941 Mr. Eldridge was playing again, with Gene Krupa's band. He teamed up as a vocalist with Anita O'Day on ''Let Me Off Uptown'' and ''Knock Me a Kiss,'' and he developed a magnificent trumpet solo on ''Rockin' Chair.'' Harrowing Experiences Joining Mr. Krupa, Mr. Eldridge became one of the first black musicians to become an integral part of a white jazz band. Later, he held a similar position with Artie Shaw's band. They occasioned harrowing experiences, and he later told an interviewer from Down Beat magazine: ''One thing you can be sure of. As long as I'm in America, I'll never in my life work with a white band again.''

Although he said Mr. Krupa, Mr. Shaw and other band members were very supportive, he was constantly turned away from hotels where the other musicians stayed, from restaurants where they ate and even from the ballrooms where he was playing with them. At Metropole and Jimmy Ryan's

In the 50's Mr. Eldridge played on the Jazz at the Philharmonic tours run by Norman Granz, who insisted in his contract on first-class accommodations for all his musicians and on playing to unsegregated audiences. Between tours, Mr. Eldridge often played at the Metropole, the long, narrow mirror-lined room just off Times Square.

In 1969 he took over leadership of the band at Jimmy Ryan's on West 54th Street, a jazz room that primarily featured Dixieland. During more than 40 years, Mr. Eldridge's relationship with Dixieland had never been more than peripheral. He adapted by learning the Dixieland routines. But learning the routines did not mean that he submitted to them.

''The band may be pumping through 'Royal Garden Blues,' '' a reviewer for The New York Times wrote, ''when, with a sudden ripping burst of sound, Mr. Eldridge razzle-dazzles his way into an electrifying solo, served with the crackling phrases and bright, sharp clusters of notes that have always been his hallmark.'' A Spokesman at Jazz Events

After developing heart problems in 1980, Mr. Eldridge, who had still been playing at Jimmy Ryan's, made the difficult decision to stop playing the trumpet. In later years he performed as a singer, a drummer and a spokesman for jazz at schools and major jazz events.

Mr. Eldridge's wife of 53 years, Viola, died three weeks ago. He is survived by a daughter, Carol, of Queens.

A service is to be held at St. Peter's Lutheran Church, in the Citicorp Center, at 54th Street and Lexington Avenue, tomorrow at 10 A.M.

A version of this article appears in print on Feb. 27, 1989, Section B, Page 7 of the National edition with the headline: Roy Eldridge, 78, Jazz Trumpeter Known for Intense Style, Is Dead. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

Eldridge in New York, 1946.