SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER TWO

MARVIN GAYE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JUNIUS PAUL

(July 10-16)

JAMES BRANDON LEWIS

(July 17-23)

MAZZ SWIFT

(July 24-30)

WARREN WOLF

(July 31-August 6)

VICTOR GOULD

(August 7-13)

SEAN JONES

(August 14-20)

JESSIE MONTGOMERY

(August 21-27)

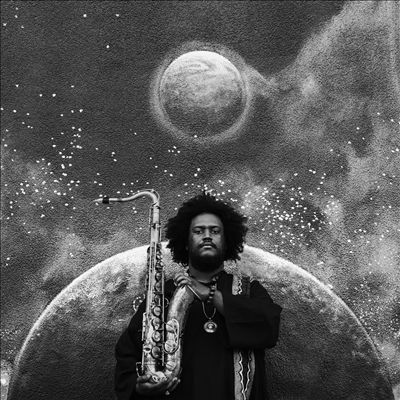

KAMASI WASHINGTON

(August 28-September 3)

TERRACE MARTIN

(September 4-10)

FLORENCE PRICE

(September 11-17)

DANIEL BERNARD ROUMAIN

(September 18-24)

ALFA MIST

(September 25-October 1)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/kamasi-washington-mn0000772447/biography

Kamasi Washington

(b. February 18, 1981)

Artist Biography by Andy Kellman

Kamasi Washington is a Los Angeles-based saxophonist, composer, and bandleader who was branded the future of the new jazz upon the arrival of his three-disc The Epic. While the term has been bandied about since the 1950s, what it refers to in his case is Washington's diversity, given his wide experience playing with artists of many disciplines. His sound draws few boundaries between modal and soul-jazz, funk, hip-hop, and electronic music.

He didn't pick up a saxophone until he was 13 years old, but by that point, he'd already been playing several other instruments. That's when he found his calling. Within a couple years, he was the lead tenor saxophonist at Hamilton High School Music Academy in his native Los Angeles. After graduation, he attended UCLA to study ethnomusicology. While enrolled at UCLA, he recorded a self-titled album with Young Jazz Giants, a quartet he had formed with Cameron Graves and brothers Ronald Bruner, Jr. and Stephen "Thundercat" Bruner, released in 2004.

From that point on, Washington continually performed and recorded with an impressive variety of major artists across several genres, including Snoop Dogg, Raphael Saadiq, Gerald Wilson, McCoy Tyner, George Duke, and PJ Morton. He self-released a handful of his own albums from 2005 to 2008 while also performing and recording as one-third of Throttle Elevator Music. In 2014 alone, Washington demonstrated his tremendous range with appearances on Broken Bells' After the Disco, Harvey Mason's Chameleon, Stanley Clarke's Up, and Flying Lotus' You're Dead!, among other albums that covered indie rock, contemporary and progressive jazz, and experimental electronic music.

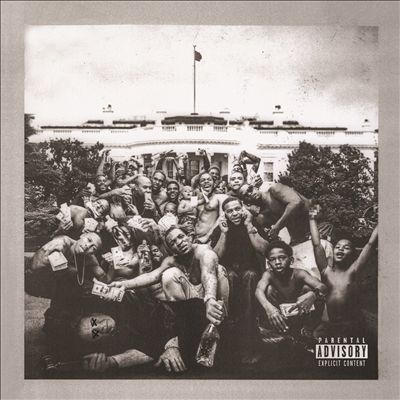

The following year, Washington contributed to Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly and released The Epic on Flying Lotus' Brainfeeder label. An expansive triple album nearly three hours in duration, it involved the other three-fourths of Young Jazz Giants -- by then part of his larger collective, alternately known as the Next Step and West Coast Get Down -- and a string orchestra and choir conducted by Miguel Atwood-Ferguson. A critical and commercial success, The Epic landed at number three on Billboard's jazz chart. Washington toured the U.S., played dates in Europe and Japan, and continued session work with contributions to albums by Terrace Martin, Carlos Niño, John Legend, Run the Jewels, and Thundercat, all while continuing to tour. Washington debuted the six-song project at the Whitney Biennial in March along with a film by A.G. Rojas and artwork by Amani Washington. In early 2017, Washington premiered Harmony of Difference, an original six-movement suite, as part of the Whitney Biennial, and compiled that recording for a six-track, 13-minute EP -- his first original music since The Epic two years earlier. Issued in September, Harmony of Difference explored the philosophical possibilities of counterpoint. Composed as a suite, it contains five separate movements and a sixth, "Truth," as a finale that includes tenets and themes from its predecessors. Washington returned in 2018 with the full-length Heaven & Earth. The double album featured contributions from Thundercat, Patrice Quinn, and Miles Mosley, and the singles "Fists of Fury" and "The Space Travelers" were released in advance of the record. Two years later Washington returned with Becoming, the original soundtrack to director Nadia Hallgren's documentary-film companion to Michelle Obama's 2018 memoir.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/kamasiwashington

Kamasi Washington

At the age of 13 Kamasi Washington decided to begin a life long quest of the many wonders to be found in music. He made this decision one night when after a rehearsal at his home his father left his soprano saxophone lying on the piano and left Kamasi with an uncontrollable curiosity of all the beauty he’d just heard come from it. So he took father’s horn, and even though he didn’t know anything about the saxophone, in fact he’d never even touched a saxophone, and played Wayne Shorter’s “Sleeping Dancer Sleep On”, his favorite song at the time. Kamasi was shocked he had been playing drums, piano, and clarinet for years but he’d never played the saxophone. Yet he was somehow able to play a song from his heart and in that received an early glimpse of the euphoria that music can bring. And at that moment he knew that music was his life’s quest and the saxophone was his voice.

Within two years Kamasi earned the lead tenor saxophone chair in the top jazz ensemble at the prestigious Hamilton High School Music Academy. At the same time Kamasi joined the Multi School Jazz Band (MSJB) where he was reunited with several child hood friends who were well on their way on their own musical quest. During his senior year of high school Kamasi formed his first band with childhood friends Ronald and Stephen Bruner on drums and bass, along with pianist Cameron Graves. The group was called “The Young Jazz Giants”. After high school Kamasi went on to study ethnomusicology at UCLA were he received a full scholarship and was exposed to many of the non-western musical cultures around the world. In the summer after his freshman year Kamasi recorded his first album with “The Young Jazz Giants” a platform they used to spread the new sound of jazz all around the country. In his second year at UCLA Kamasi went on his first national tour with the west coast hip-hop legend Snoop Dog. Ironically this band was made of many of the most talented young jazz musicians in the country. Later that year Kamasi joined The Gerald Wilson orchestra. Gerald Wilson was his biggest hero compositionally and being a part of his orchestra motivated him to make composition the focus of his major at UCLA. In doing so Kamasi began studying many of the great American and European composers.

After his senior year at UCLA Kamasi went on his first international tour with RnB legend Raphael Saadiq who had ¾ of “The Young Jazz Giants” in his band. Later that year he was given the honor of representing Gerald Wilson’s Los Angeles band on his album “In My Time” witch featured Wilson’s New York based orchestra. Over the next few years Kamasi was blessed to be able to perform and record with many of his musical heroes, from many different genres. He played with legendary jazz artist such as McCoy Tyner, Freddie Hubbard, Kenny Burrell, and George Duke. At the same time he was working with artist such as Lauryn Hill, Jeffrey Osborne, Mos Def, and Quincy Jones. During this same time Kamasi started his new band called “The Next Step”, a kind of modern spin on a big band, with two drummers, two bassist upright and electric, piano and keyboards, three horns and a vocalist.

Kamasi Washington. Credit: Awol Erizku for The New York Times

On a late October afternoon in South Central Los Angeles, Kamasi Washington was facing what is for him an increasingly familiar problem: making a lot of big ideas fit into a single space, even one as large as the nearby Club Nokia, a rock-star-size venue where he would be performing in December. His recent triple album, ‘‘The Epic,’’ is a nearly three-hour suite for a 10-piece jazz band, backed by a 32-piece orchestra and a 20-person choir. Washington’s show promised to be a typical swirl of activity, a sprawling procession of dancers, musicians, DJs and singers unified by the magisterial sound of Washington himself, a 34-year-old tenor saxophonist who has emerged as the most-talked-about jazz musician since Wynton Marsalis arrived on the New York scene three decades ago.

At that moment, Washington was at his aunt’s dance studio, trying to figure out where to put all the dancers. Lula Washington — whose troupe would be doing the dancing, at least if her nephew could convince her — knew that there would be a crowd onstage, and she didn’t want her people to get lost in it. Kamasi listened patiently, then got down on the floor and sketched the Nokia stage, insisting that it was more spacious than she imagined. Maybe a riser here? She looked skeptical. They would work it out somehow, she said, but she did not seem persuaded. (As it turned out, Kamasi’s vision exceeded the limits of this particular stage: Lula’s dancers did not perform in the show.)

Near the end of our visit, I asked Lula if she knew what the ‘‘epic’’ in the album title referred to. ‘‘As a matter of fact, I don’t,’’ she said. ‘‘Please, do tell.’’ I was relieved: Washington had been promising to tell me the story for several days. Since the release of ‘‘The Epic’’ last May, Washington has gone from being a well-known local musician to that rarest of musical species: a jazz celebrity, praised by critics and featured on ‘‘The Tavis Smiley Show.’’ The timing of the release was providential: Only months earlier, Washington played saxophone on Kendrick Lamar’s ‘‘To Pimp a Butterfly,’’ for which he also wrote the string arrangements. Lamar’s landmark hip-hop album, a harrowing coming-of-age memoir, featured the contributions of several of Washington’s bandmates, young Los Angeles musicians for whom the boundaries between jazz and more popular genres are so porous as to be nonexistent. On social media, ‘‘The Epic’’ was promoted as a kind of jazz sequel to ‘‘To Pimp a Butterfly.’’

I assumed that ‘‘The Epic’’ referred to some momentous story from the past or, more broadly, to the sweep of the album’s musical ambitions. But as far as I could tell, Washington had never told the story in public before, nor (apparently) had he told his own aunt. We looked at him expectantly.

The answer was more involved than I had guessed. ‘‘After I recorded the music,’’ he began, ‘‘I had this dream about a group of young warriors living in a village beneath a mountain.’’ He went on: ‘‘At the top of that mountain, there’s this gate, protected by a guard. The warriors spend all their time training to kill the guard and seize control of the gate. One by one, they are defeated by the guard. But the last warrior has the power to win, and the guard hesitates for the first time, because he sees that the warrior’s heart is good and that his own time has come.’’

‘‘That was all in one dream?’’ Lula asked.

Kamasi nodded. Actually, he said, he went on to have a series of interrelated dreams, a hall of mirrors in which it turns out that the guard wasn’t really killed by the young warrior. He said it would take him three hours — no, days — to tell us the whole thing. He planned to turn it all into a graphic novel with an illustrator friend.

I asked what all this had to do with jazz. Kamasi again nodded.

‘‘The guard is the person who protects the music and pushes it forward,’’ he said. The hope of the young warrior, he continued, is to take his place and impose his own standards. This explained, perhaps, why the first track of ‘‘The Epic’’ is called ‘‘Change of the Guard.’’ It begins with a bright series of chords laid down by the pianist Cameron Graves, followed by a tidal wave of reeds, choir and strings. A brash and infectiously bombastic wall of sound, the opening stirs memories of the grand, modal style that John Coltrane patented in the 1960s. When I first heard ‘‘Change of the Guard,’’ I was struck by its unabashed evocation of an era that Washington never experienced directly.

Unaware of the manga-style story that inspired the title, many listeners heard it as an allegory of that greatest of American epics, the African-American freedom struggle since slavery. Certainly Washington looked well cast for the part, a bearded, dashiki-clad man with an Afro whose sheer size seemed to convey the magnitude of his ambitions. ‘‘The Epic’’ tapped into an intense nostalgia for an era when, as Washington puts it, ‘‘music was a sword of the civil rights movement.’’ But it has awakened those feelings in listeners who, in most cases, were not alive to know that era. The audiences lining up to see his band have been unusually large (Washington plays in concert halls, not small jazz clubs), unusually multiracial and unusually young. And they do something that people at jazz concerts seldom do anymore: They dance. When I saw him perform in Brooklyn, the audience roared when he came onstage, as if he were a rock star. (He will, in fact, be joining Guns N’ Roses in the lineup at the Coachella festival in April.)

This kind of feverish response explains the hysteria — and occasional bewilderment — that Washington’s name provokes among jazz people. ‘‘People are talking about this in a way that I haven’t heard them talking about anything in a long time,’’ the jazz pianist Jason Moran told me. ‘‘It’s a moment when black L.A. has something to say, and people are listening.’’ He added: ‘‘Our relationship with this country has always been documented through how the music changes. This is a time when black America is on fire, and Kamasi is adding fuel to the flames.’’

Like the dream that inspired ‘‘The Epic,’’ Washington’s own story is a tale of guards and warriors. Every young jazz musician has had to wrestle with the gatekeepers of tradition; jazz celebrates youthful originality, but it also prizes respect, even reverence, for the music’s founders. Washington is no less sensitive to the spirits of the past than Wynton Marsalis and the so-called Young Lions who burst onto the scene in the early 1980s, playing a somewhat updated version of 1960s-era small-group jazz in Brooks Brothers suits. Marsalis wanted to revive the fundamentals of blues and swing, which he believed jazz musicians had forgotten during the 1970s, an era of avant-garde and fusion experimentation. Washington, by contrast, conjures the ghosts of 1960s and ’70s black-consciousness jazz, of the ecstatic, expressive Coltrane and his successors.

It would be unfair, and a little silly, to ask whether Washington might be the next Coltrane. In any case, there’s room for only one Coltrane in the theology of jazz. But with his overt spiritualism and his humble bearing, Washington has reawakened the widespread longing for a Coltrane-like figure who might lead jazz out of the desert of obscurity and restore its spiritual purpose. He is not the first such figure — Pharoah Sanders, Albert Ayler and David S. Ware have been cast as prophetic messengers in the wake of Coltrane’s death in 1967 — but he is the first to come along in some time. Stranger still, he comes from a city that few people even associate with jazz.

In fact, Los Angeles has a venerable jazz tradition, going back to the Central Avenue scene of the 1940s and the West Coast ‘‘cool’’ of the 1950s. But most of the city’s better-known players (Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Dexter Gordon) had to head East to make a name for themselves. Washington’s father, Rickey, a saxophonist and flutist, was one of those who stayed behind. In early October, shortly after I arrived in Los Angeles, I had lunch with Rickey and Kamasi at a vegan soul food restaurant in Inglewood, a working-class, predominantly black bedroom community near Los Angeles International Airport. They mostly talked about jazz. Actually, Rickey did most of the talking. He reeled off the names of the great musicians who made Los Angeles, his Los Angeles, such a vibrant jazz scene. Men like the pianist Horace Tapscott, the leader of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, who used his art to raise the political consciousness of the black community in the 1960s and ’70s, and the drummer Billy Higgins, who came home to build the World Stage, a performing-arts center in South Central. These were the musicians who nurtured him and prepared the way for his son. His pride in Kamasi was obvious, but I thought I also detected a rueful note: Rickey supported his family as a music teacher and never earned more than a local reputation. Kamasi didn’t say much, until a noisy piece of jazz fusion came on the stereo.

‘‘You know what record this is?’’ he asked.

‘‘Yeah, yeah. . . .’’ Rickey hummed the tune. ‘‘I don’t know who’s playing, though.’’

‘‘The drummer played in your band. He used to dye his hair blond.’’

‘‘Blond hair and played in my band?’’

‘‘It’s Ronald Bruner Sr.’’

Bruner Sr., who played with the Temptations, is the father of two of Kamasi’s bandmates: Ronald Bruner Jr., also a drummer; and the bassist and singer Stephen Bruner, who makes brooding, ethereal indie-funk under the name Thundercat and whose nimble playing is all over Kendrick Lamar’s latest album. Like the Marsalis brothers, many musicians in the Los Angeles scene come from musical families. Kamasi told me that ‘‘Change of the Guard’’ is a tribute to men like his father and Bruner Sr., musicians who ‘‘had something to say but never had a chance to say it’’ beyond Los Angeles. Throughout the 1980s, Rickey Washington led a Christian jazz band, which Bruner joined after giving up secular music. When Kamasi first expressed a desire to play, his father sent him to church. ‘‘It’s the best place to learn,’’ Rickey said. ‘‘You play every week, and you’ve got to play a groove. It doesn’t come any other way but with a groove. They’re clapping on two and four, and you’re moving to the music. If you listen to Kamasi, you know what the groove is, because it’s right in his body.’’

I went to hear Washington play gospel a few days later at a Nigerian evangelical church. The stage was bathed in pink and purple lighting worthy of a Prince show. Hundreds of parishioners, overwhelmingly Nigerian, many in African ceremonial clothes, swayed to gospel songs made faster and funkier by Nigerian highlife beats. Washington’s solos were modest in length, as befit a sideman, but he kept his big, preacherly sound. Whenever he played, the music came into stirring focus, and his flowing African robes gave him the air of a griot or medicine man.

‘‘I always noticed that ’Trane thing, that spirituality, in Kamasi’s playing,’’ said the guitarist Greg Dalton, who performs under the name Gee Mack and who once employed Washington in a band. ‘‘You can have all the technique in the world, but if you can’t connect with an audience, it doesn’t matter. And this man, Kamasi, is a poet.’’ The church’s pastor wasn’t aware that Washington is a rising star of the tenor sax, but as we left the church, a young boy came up to tell us that he had just seen him on television. Washington smiled at the boy. ‘‘Do you play an instrument?’’ he asked.

Washington lives in Inglewood, in the same house where he grew up. He now rents it from his father. The lawn is immaculately manicured, the yellow-stucco front entrance nearly hidden by flowerpots. He works on his music in the garage, which he converted with his father into a home studio furnished with a keyboard, a drum set and recording equipment. There are Christian inspirational illustrations on the wall; a dog-eared copy of the score of ‘‘The Rite of Spring’’ lies on his desk, and stacks of old vinyl cover the floor. Washington moved back to Inglewood a few years ago, after living in Westwood and Culver City, where he felt ‘‘an undercurrent of racism, like you don’t want me here.’’ He added, ‘‘This is home, whereas there, I felt like I was in someone else’s home.’’

That sense of home, of African-American pride and identity, reverberates throughout ‘‘The Epic.’’ It’s not just the tributes to his grandmother and great-grandmother, or the concluding hymn to Malcolm X, which incorporates Ossie Davis’s eulogy as well as one of Malcolm’s speeches. It’s the album’s soaring panorama of black American musical history, from gospel and blues to jazz, doo-wop and funk, offered as a celebration of black beauty in the face of adversity. Its sound is particularly evocative of the early 1970s, when Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield and Stevie Wonder were composing their own epics and jazz musicians like Max Roach were playing spirituals with gospel choirs. The Afro-futurist cover of ‘‘The Epic,’’ too, suggests an early ’70s LP: a picture of Washington in a black dashiki against an interstellar backdrop, saxophone in hand.

That blend of rebellious intent and retro self-fashioning is hardly unique to Washington. It permeates the cultural renaissance spawned by Black Lives Matter, a movement that has combined Black Power nostalgia with an exuberant faith in the revolutionary potential of technology and social media. ‘‘The Epic’’ is arguably the most ambitious expression thus far of this renaissance, whose touchstones also include Claudia Rankine’s prose-poem ‘‘Citizen,’’ Ta-Nehisi Coates’s memoir ‘‘Between the World and Me,’’ D’Angelo’s album ‘‘Black Messiah’’ and Kendrick Lamar’s ‘‘To Pimp a Butterfly,’’ with its indelible refrain, ‘‘We gon’ be alright.’’ Not surprisingly, ‘‘The Epic’’ has found a particularly receptive following among black intellectuals. As Robin Kelley, a historian at U.C.L.A. and a biographer of Thelonious Monk, puts it, ‘‘In a world where you feel like blackness is under assault and you’re looking for a way to express joy, pain and possibility, ‘The Epic’ speaks to what black people feel inside.’’ The writer Greg Tate, who calls Washington the ‘‘jazz voice of Black Lives Matter,’’ told me that his music offers ‘‘a healing force, a place of regeneration when you’re trying to deal with the trauma of being black in America.’’

I mentioned Tate’s assessment to Washington as we stood in the midday heat on Crenshaw, a main boulevard in South Central, in front of a Senegalese shop where he has his dashikis made. At the mosque next door, a small group of men was gathered, and an old man was selling baked chicken and cornbread from a cart. ‘‘Music is an expression of who you are, and — at least in that sense — I think I epitomize Black Lives Matter,’’ he said. ‘‘I’m a big black man, and I’m easily misunderstood. Before I started wearing these African clothes, people would assume that I was a threat and that it was O.K. to be violent toward me.’’ He scratched his beard and paused to reflect. ‘‘The harsh reality in our communities is that the greatest representatives of order, the police, are basically against you, so you feel as if you live in a society without order.’’

At 13, Washington announced to his father that he wanted to be a jazz musician. To test his seriousness, Rickey asked his son to sing a Charlie Parker solo. (‘‘I knew if you couldn’t sing it, you couldn’t play it,’’ Rickey said.) Kamasi sang the head and solo of Parker’s 1951 bop classic ‘‘Blues for Alice’’ note for note. His father’s reward was a Conn 6M alto saxophone, the same model Parker played. He played the alto in church for nearly a year, then switched to tenor — his father’s. ‘‘He took my tenor!’’ Rickey said. ‘‘A Selmer Mark VI, the best saxophone they make. He didn’t realize how valuable it was.’’ It’s the only tenor Kamasi has ever played.

Coltrane became his obsession. His favorite record was ‘‘Transition,’’ a defining work of Coltrane’s classic quartet. It was avant-garde yet still melodic, exhilaratingly expressive but never chaotic. ‘‘He was just treading a line in a way that was powerful,’’ Kamasi said. ‘‘ ‘Transition’ was like the rarest of the rare steaks without being raw. You could still eat it.’’ He modeled himself on Coltrane, not just his sound but also his legendary practice regimen — as long as 12 hours a day, with sometimes hours spent on a single scale or even a single note. Washington was soon averaging nine hours a day; as if to summon the master’s spirit, he often worked on Coltrane tunes. He and Cameron Graves, who is now his pianist, ‘‘used to compete with each other to see who could practice the most.’’ It was a monkish existence, Washington said. ‘‘Becoming a musician is a strange thing. It’s not all cupcakes and ice cream. You’re trying to master an instrument, and you sometimes can’t tell if you’re getting better. You love it, but you also hate it.’’

It was not long after he took up the tenor sax that Washington met another jazz ‘‘guard’’: Reggie Andrews, a music teacher at Locke High School in Watts. Andrews, whose former students included Rickey Washington, had grown frustrated that the city’s magnet schools had poached the best young musicians — including Kamasi Washington, who was discovering Prokofiev and Stravinsky at Alexander Hamilton High School, a prestigious musical academy near Culver City. Andrews began visiting nearby schools and asking the music teachers to identify their best pupils. His idea was to pick them up in his van after school, drive them to Locke and turn them into a group. He called it the Multi-School Jazz Band, and before long it was performing throughout the city. I drove with Washington to Locke, a squat structure surrounded by a wire fence that made it look more like a prison than a school. ‘‘The amazing thing is that white kids were coming down to Locke to rehearse because the band was so good and they wanted to be in it,’’ he remembered. ‘‘It was kind of ironic, since we were being bused to their schools.’’ Seeing young whites flock to Locke gave Washington a taste of power, an awareness of the cachet he possessed as an African-American musician. In spite of the ‘‘denial of our humanity,’’ he realized, ‘‘everybody wants to dress and talk like us.’’

‘Becoming a musician is a strange thing. It’s not all cupcakes and ice cream. You’re trying to master an instrument, and you sometimes can’t tell if you’re getting better. You love it, but you also hate it.’

The Multi-School Jazz Band reunited Washington with the Bruner brothers and introduced all three to the musicians with whom they would eventually form the Los Angeles jazz underground, including the alto saxophonist Terrace Martin (who wrote and produced much of the music on Kendrick Lamar’s latest album), the pianist Cameron Graves, the bassist Miles Mosley and the trombonist Ryan Porter. ‘‘Reggie Andrews realized that there was a brain drain from the community and that we were losing the advantages of being connected to one another,’’ Washington told me. After band practice, Washington would go home with Ronald Bruner Jr. and jam in his father’s shed. Like Washington, Bruner was driven partly by a sense that his own father hadn’t achieved his potential as a musician. ‘‘My father was on the way to becoming the guy, and then he gave it up to play Christian music,’’ he told me.

Music was not the only thing Andrews’s students had in common: Most of them were growing up black, male and at risk in Los Angeles. ‘‘We could have gone into gangbanging,’’ Bruner told me. ‘‘That model was available to us. I was in a situation that got out of control, and a friend of mine died. But that difficulty made everyone stronger. The threat of being caught up in that makes you push harder.’’

They had Andrews to keep them on track. A tall, solidly built man now in his late 60s who wears a mustache and a Tuskegee baseball cap, Andrews radiates self-confidence, drive and impatience with excuses. Over breakfast one morning at a local soul-food restaurant, he told me how he made sure his players kept their grades up and emphasized the importance of craftsmanship and professionalism. ‘‘Kamasi can do the Archie Shepp thing or the ’Trane thing and ride that note,’’ he said, ‘‘but he knows how to take it back.’’

Washington received a different kind of mentoring in Leimert Park, where he and his friends went to after-hours jam sessions. Leimert Park was designed by the Olmsted firm in the late 1920s as a whites-only planned community, but by the 1960s it had become an African-American neighborhood. After the 1965 Watts riots, Leimert Park became a center of the Black Arts movement, a cultural offshoot of the Black Power movement. Lined with fig trees and exuding community pride, Leimert Park was as close to an oasis as you could find in South Central. Even during the crack epidemic, it remained a home to black-owned art galleries, bookstores and clothing shops.

When Washington began going there in the mid-1990s, it was in the middle of a revival. Its mecca was the World Stage, the nonprofit performing-arts gallery established by Billy Higgins and the poet Kamau Daáood, a leader of the Black Arts movement. Higgins and Daáood envisioned the World Stage as an extension of the ’60s jazz activism pioneered by Daáood’s mentor, Horace Tapscott. It could barely seat 50 people, but it attracted some of the greatest musicians in jazz and helped inspire a scene that cut across divisions of generation and genre. ‘‘We were in Leimert Park every night,’’ Washington says. ‘‘We’d get in everywhere without money. I still don’t know how we did it.’’

In 1999, Washington began studying at U.C.L.A. with the composer Gerald Wilson, who had written charts for Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald. But in his first year, Marlon Williams, Snoop Dogg’s musical director, invited Washington to go on tour with the rapper. A former guitarist in the black rock band Fishbone, Williams had already recruited Washington’s friend Terrace Martin to put together Snoop’s horn section, and Martin immediately called Washington. ‘‘I was a big Snoop Dogg fan, and I knew the repertoire — I mean, this was dope,’’ Washington recalled. Although ‘‘it was cool to make money,’’ financial considerations were far less compelling than the promise of adventure. ‘‘I had never been on the road,’’ he said. ‘‘I’d been to New York and D.C. once, so it was a chance to go on tour. I was young and on a full scholarship, so I hadn’t even gotten to the point of thinking about the economics of the music business.’’ Washington continued his studies with Wilson, but he received an equally important education with Professor Snoop.

At the point when Washington got the call, he had been spending most of his time trying to master harmonically demanding songs like Coltrane’s ‘‘Giant Steps.’’ Now his job was to play apparently simple riffs to ‘‘line up with the groove.’’ Playing those riffs, however, was tougher than it looked: Hip-hop was a miniaturist art of deceptive simplicity. ‘‘When you play jazz in school, you talk about articulation, but it’s a very light conversation,’’ he said. ‘‘The question was about what you were playing, not how you were playing it. But when I was playing with Snoop, what I was playing was pretty obvious — anyone with ears could figure it out. The question was how to play it, with the right articulation and timing and tone.’’ Snoop didn’t come to rehearsals or even really explain what he wanted. ‘‘It was all very unspoken. You had to use your intuition to figure out why it didn’t sound right. We had to have it right before he got there, because if it was wrong, he’d veto it, and we’d have to just sit there.’’

Snoop was particularly demanding when it came to the placement of notes in relation to the beat, and Washington struggled at first to hear the beat the way Snoop did. After a while, though, he began to discern what he calls ‘‘the little subtleties,’’ the way, for example, ‘‘the drummer D-Loc would lock into the bass line.’’ He continued: ‘‘It wasn’t like the compositional elements in Stravinsky. It wasn’t about counterpoint or thick harmonies. It was more about the relationships and the timing, the one little cool thing you could play in that little space. It might just be one little thing in a four-minute song, but it was the perfect thing you could play in it. I started to hear music in a different way, and it changed the way I played jazz. Just playing the notes didn’t do it for me anymore.’’ He came to see hip-hop as a relative of jazz. ‘‘All forms are complex once you get to a really high level, and jazz and hip-hop are so connected,’’ he said. ‘‘In hip-hop you sample, while in jazz you take Broadway tunes and turn them into something different. They’re both forms that repurpose other forms of music.’’

Washington often skips in conversation from Kendrick Lamar to Coltrane, and from Charlie Parker to Stravinsky. The reason that we don’t see these connections, he says, is that we’re captives of ‘‘preconceived notions,’’ the most confining being the very idea of ‘‘jazz.’’ Some musicians complain that even the word ‘‘jazz’’ deprives them of a popular audience; others see it as an insult. As the trumpeter Nicholas Payton recently put it, ‘‘ ‘Jazz’ is an oppressive, colonialist slave term.’’ For musicians like Payton, ‘‘jazz’’ is a white establishment label that cuts their music off from other black musical forms; they prefer terms like ‘‘black art music,’’ ‘‘black classical music,’’ ‘‘black creative music’’ or simply ‘‘black music.’’

But Washington’s criticism of musical categories is at once more expansive and more subtle than Payton’s. For Washington, the problem is not merely that categories ghettoize forms of music, but that they prevent us from fully listening. All music, he believes, deserves a fair hearing — even much ridiculed forms like ‘‘smooth jazz.’’ I had brunch one morning with Washington and his girlfriend, Tiffany Wright, an earnest young woman with long braids who established a private elementary school in Wilshire under her own name, the Wright Academy. An insidiously saccharine ballad by the smooth-jazz saxophonist Najee came on. I asked Washington if it bothered him that some people mistook this sort of jazz for the real thing.

‘‘I don’t have an aversion to it,’’ he said. In fact, he went on, he liked some smooth jazz, notably the saxophone player Grover Washington Jr. (no relation). Gently taking me to task for my snobbery, he noted that Najee, like many smooth-jazz players, had roots in gospel — and that in any case, no musical genre is entirely devoid of value.

‘‘You want my layman’s interpretation?’’ Wright volunteered. ‘‘Kamasi is totally nonjudgmental, in all areas. It makes life a lot less stressful.’’

That mellow, West Coast inclusiveness is another pointed contrast between Washington and the young Wynton Marsalis, who once declared, ‘‘There is nothing sadder than a jazz musician playing funk.’’ When Washington and his trombonist, Ryan Porter, trade riffs, they make no secret of their love of Maceo Parker and Fred Wesley, two of the horn men in the James Brown band. ‘‘It wasn’t a mistake to call James Brown’s music funk, but I’m not sure it was good for jazz,’’ Washington told me. Jazz, as he sees it, is not so much a genre as a way of styling music. Which means that if he is playing Debussy’s ‘‘Clair de Lune’’ — as he does in a languorous, brazenly sentimental arrangement on ‘‘The Epic’’ — it’s jazz.

Surprisingly, given that Washington toured with Snoop and later Lauryn Hill, one genre you don’t hear on ‘‘The Epic’’ is hip-hop. ‘‘I was already playing all that,’’ he explains. ‘‘When I got to do my music, I wanted to play like me.’’

As it happened, his friends from the Multi-School Jazz Band felt the same way, and in 2009 they did what independently minded jazz musicians have done since the 1960s: They organized themselves into a collective, the West Coast Get Down. They started out playing at a Hollywood cocktail lounge called Piano Bar, developing a repertoire in front of crowds of 20-somethings who had no interest — or at least no prior interest — in jazz. (Eventually the crowds grew so large that the fire marshal was called in.) The collective’s founder was Miles Mosley, who plays an upright bass through a wah-wah pedal, but Washington soon established himself as the charismatic leader. He was playing jazz, but it was jazz imbued with the vibrations of the church and the ‘‘little subtleties’’ of pulse and timbre that he picked up from Snoop Dogg. It was, in other words, a groove-based jazz, adjacent to the Afro-futurist psychedelia of his friend and collaborator Steven Ellison, a musician who records under the name Flying Lotus. (Ellison is the grandnephew of Alice Coltrane, John Coltrane’s second wife and a major pianist and composer in her own right.) You didn’t have to be a jazz geek to appreciate it; in fact, it was easier to appreciate if you weren’t.

In 2011, after two years of testing their ideas at Piano Bar, Washington and his friends decided that it was time to go into the studio. They all pitched in to rent the Kingsize Soundlabs in Echo Park, canceled all their gigs for December and barely left except to sleep. The musicians weren’t paid for their work, because they were all playing on one another’s records. By the end of the month, they had 192 songs; 45 were under Washington’s leadership. He chose 17 for ‘‘The Epic,’’ 14 of them his own compositions. The album came out on Brainfeeder, an independent label run by Ellison.

Ellison didn’t blink when Washington told him that his album for Brainfeeder was going to be three hours of music. ‘‘Kamasi is a murderer on the saxophone,’’ Ellison said when I ran into him at a concert in downtown Los Angeles.

The music on ‘‘The Epic’’ was already quite dense, with three people on horns, two drummers, two bassists, two keyboardists and a singer, but Washington wasn’t done tinkering. While touring with Chaka Khan, he began to write choir and string parts. Washington told me that he wanted to evoke Stravinsky’s ‘‘Symphony of Psalms’’ in the choir and string arrangements, but they’re equally reminiscent of Marvin Gaye’s ‘‘What’s Going On’’ and Curtis Mayfield’s ‘‘Superfly.’’ Above all, ‘‘The Epic’’ breathes new life into the black consciousness or ‘‘spiritual’’ jazz of the early 1970s, when saxophonists like Pharoah Sanders, Gary Bartz, Joe Henderson and Billy Harper grafted free jazz sonorities onto hard-bop melodies and danceable grooves, often embroidering them with African percussion as well. An expression of the cultural nationalism that spread across urban black communities in the 1970s, spiritual jazz has often been dismissed as Afrocentric kitsch in histories of jazz, but it was popular in black America, and it was the jazz that Rickey Washington played on the stereo at home. It aimed to move the audience but also instruct them. If they didn’t get the message, the album titles spelled it out: ‘‘Black Unity,’’ ‘‘Black Saint,’’ ‘‘In Pursuit of Blackness,’’ ‘‘Power to the People.’’

‘Kamasi is a messenger, and his message speaks to something deep within me.’

Serendipity, of course, has been an important ingredient in their success. As Greg Tate told me, ‘‘You have to go to mysticism to explain how these things come together at the same time: the best heroic jazz origin story since the Marsalis brothers, being on Kendrick Lamar’s record and Flying Lotus’s label, and Black Lives Matter.’’ But the Los Angeles scene would not have had the same impact without Washington’s personal charisma, his deeply spiritual sound and his welcoming, Buddha-like aura. He may not be a major innovator, but he is a remarkably forceful communicator: in the words of Kamau Daáood, ‘‘a perfect vessel for the coming together of generations in his music.’’

In October, a couple of weeks before Washington would fly to Tokyo on his first world tour, his father organized a dinner with a group of distinguished older jazz musicians. ‘‘When you are chosen,’’ Rickey explained to me, ‘‘you need the blessings of your elders.’’ (Reggie Andrews had a more down-to-earth explanation: ‘‘Kamasi’s about to step into the fast lane, so Rickey wanted him to receive some advice from people who’ve been there.’’) This ‘‘change of the guard’’ ceremony took place at the Ladera Heights home of Curtis Jenkins, who runs a business that provides care for disabled children in South Central. In a flight of enthusiasm, Rickey had invited me to attend the dinner. The next day, Kamasi’s manager, Banch Abegaze, disinvited me; she said it was for only close friends and family. But she suggested that I stop by later in the evening.

When I arrived, the shades were fully drawn, as if a séance were in session, but inside I found a group of nine older men nibbling on plates of Ethiopian vegetarian food. (The only women there were Kamasi’s manager and his girlfriend.) There were paintings of Miles Davis, African-themed artworks and framed photographs of Jenkins with the Obamas and the Clintons. Jenkins, a small, excitable man who grew up in Compton at the time of the Watts riots and studied filmmaking at U.C.L.A., told me that when he first heard ‘‘The Epic,’’ it struck him as ‘‘an announcement.’’ Not since the days of Davis and Coltrane had he been so moved by a work of jazz. When he read in The Los Angeles Times that Kamasi Washington was the son of his old acquaintance Rickey Washington, he contacted Rickey, who asked him to document Kamasi’s concerts on video. He has been traveling with the band off and on ever since. ‘‘Kamasi is a messenger, and his message speaks to something deep within me.’’ I asked him what the message was. ‘‘Freedom of thought and action,’’ he replied.

After dinner, the men gathered on sofas around Kamasi, who sat in a chair in front of a fireplace. He was wearing a dashiki and a knitted Jamaican cap; he seemed to be deep in thought, his eyes in some far-off place. The first speaker was Bennie Maupin, who played bass clarinet on Davis’s ‘‘Bitches Brew’’ and a variety of reed instruments in Herbie Hancock’s fusion band Headhunters. He began by asking Kamasi to explain the meaning of his name.

‘‘It was intended to be Kumasi, the capital of the Ashanti tribes in Ghana,’’ he said. ‘‘To be under the kuma tree is to bring people together, to bring peace.’’ Rickey Washington and a friend had gotten lost one night in Kumasi while they were on tour in Ghana in the late 1970s. ‘‘A guy came out of his house and gave them a place to stay for the night,’’ Kamasi said. ‘‘The hospitality was higher than anything he’d experienced in Watts, where you might just get robbed. He wanted to name me after that city, but since this was before Yahoo and Google, he misremembered what it was called.’’

‘‘Yeah, I was into that whole consciousness thing when I named him,’’ Rickey said. ‘‘The kuma tree brings shade, and I prayed that Kamasi would be a person who brings people together.’’

‘‘The energy in this music is a healing energy,’’ Maupin continued, praising Kamasi’s wisdom and kindness, promising to stand behind him and urging him to choose his friends carefully and be mindful of his health. Coltrane, he recalled, had regretted ‘‘wasting so much time’’ at the end of his short life.

Kamasi Washington

by Kevin Le Gendre

A strong dynamic soloist who is adept at both changes and changes-free material Kamasi Washington has emerged as something of a spearhead for American, and more specifically West coast jazz, in the past few years

Without a doubt Washington has been the success story in jazz over the past few years. His 2016 debut The Epic was the kind of ambitious 3-CD set that most artists would record at a latter rather than earlier stage of their careers. However, the sprawling opus, which stood out for the considerable resources – double rhythm section, choir and string orchestra – deployed by the tenor saxophonist-composer, captured the public imagination to such a degree that several months after its release Washington made a sold-out appearance at the Barbican as part of the London Jazz festival, and also found himself in demand to headline at events such as A Love Supreme the following year.

The Epic achieved runaway success partly because its salient references, ‘70s Pharoah Sanders and the orchestral works of Horace Silver, as well as the hefty low end of hip-hop and funk, meant something to a generation of black music fans who came into jazz through samples and breakbeats. It was revealing that scores of young people turned up to Washington concerts.

But there was also the compelling back story of The West Coast Get Down, the collective of Los Angeles-based musicians whence he came, which featured strong personalities such as double bassist Miles Mosley, drummers Ronald Bruner and Tony Austin, bass guitarist Stephen Bruner aka Thundercat and vocalists Patricia Quinn and Dwight Trible.

Kamasi Washington's 'The Epic' in Concert

Having both issued work on the Ninjatune label, Thundercat and Trible were known to UK audiences, but the arrival of the full WCGD crew simply added to the considerable buzz around Washington whose cheerleaders were keen to present the LA cohort very much as an alternative to the traditional jazz epicentre of New York and the East Coast.

In any case, Washington’s credentials were impressive. Son of saxophonist-flautist Ricky Washington, a one time member of Earth, Wind & Fire, he had been mentored by legends such as the big band veteran Gerald Wilson, who specifically challenged him to write for strings as well as rhythm sections.

Tied as he was to the jazz tradition Washington had an avowed interest in hip-hop and the world of urban music also embraced the saxophonist partly because of his association with the likes of producer Flying Lotus and rapper Kendrick Lamarr, to whose To Pimp A Butterfly Washington made a vital contribution as both arranger and player.

A strong dynamic soloist who is adept at both changes and changes-free material Washington has emerged as something of a spearhead for American, and more specifically West coast jazz, in the past few years, and the fact that he has maintained high standards on his other releases to date, the 2017 EP Harmony Of Difference and 2018 album Heaven And Earth suggest Washington has his peak creative years ahead of him.

Kamasi Washington was born on February 18, 1981 in Los Angeles, California. Both of Washington’s parents were talented musicians and teachers, and were a big influence on their son’s passion for music. In his early years, Washington’s family moved from L.A. to Inglewood where he attended the Academy of Music of Alexander Hamilton High. His obvious talent playing instruments such as the saxophone became apparent during his time in high school, and Washington soon applied to study at UCLA’s Department of Ethnomusicology. Here, Washington began playing with some of his faculty members such as Billy Higgins, Kenny Burrell and trumpeter/band leader Gerald Wilson. Soon after, Washington established his own quartet with Cameron Graves and brothers Ronald Bruner, Jr. and Stephen “Thundercat” Bruner. In 2004, they released their self-titled album, Young Jazz Giants.

By 2005, Washington ventured into big band music when he joined the Gerald Wilson Orchestra for their 2005 album In My Time. Between 2005 and 2008, Washington released a handful of his own albums, and played with a number of talented musicians such as Snoop Dogg, Raphael Saadiq, Gerald Wilson, McCoy Tyner, George Duke, and PJ Morton.

2015 was a pivotal moment in Washington’s career when he was asked to contribute to Kendrick Lamar’s acclaimed album To Pimp a Butterfly. In it, Washington shows off his incredible talent at the tenor-saxophone. In the same year, he released the hit LP The Epic the Brainfeeder Label. The album “instantly set him on a path as our generation’s torchbearer for progressive, improvisational music that would open the door for young audiences to experience music unlike anything they had heard before.” The 172-minute odyssey featuring his 10-piece band, is littered with “elements of hip-hop, classical and R&B music, all major influences on the young saxophonist and bandleader, who exceeds any notions of what “jazz” music is.” Released to critical acclaim, The Epic won numerous awards, including the inaugural American Music Prize and the Gilles Peterson Worldwide album of the year. Since 2015, Washington has released two hit albums Harmony of Difference (2017) and Heaven & Earth (2018).

Street Fighter Mas (2018)

The song “Street Fighter Mas” was released on Washington’s 2018 album, Heaven & Earth. In an interview with National Public Radio, Washington explained that the song was a tribute to his favourite video game from his youth titled Street Fighter. As stated in the interview, “the video games and cartoons of his childhood make up a big part of his imagination today…The Heaven side of his new album Heaven and Earth, which includes “Street Fighter Mas,” is a dive into that imagination.”

Washington expressed that he struggled to make his last album – feeling confined by the concept of what the album should be. “I have to always check back in with my imagination just to remember that I have this infinite potential, and I can do anything and anything is possible.”

https://www.kcrw.com/music/shows/morning-becomes-eclectic/kamasi-washington-ballet-graphic-novel-hollywood-bowl-interviewKamasi Washington is composing a ballet, writing a graphic novel, and binge watching his own mind

‘There’ll be some big surprises, I’ll say that much,’ Kamasi Washington says of his return to the Hollywood Bowl for KCRW’s World Festival series. Photo by Russell Hamilton.

LA jazz luminary Kamasi Washington returns to the Hollywood Bowl with Earl Sweatshirt on Sunday night to kick off KCRW’s World Festival series. The artist’s hometown comeback after 18 months will be one for the books, featuring loads of new music and top-secret surprise guests under the stars.

The ever-prolific Washington seized his time off during the pandemic as an opportunity for personal reflection and creative inspiration, during which he embarked on new mediums, new styles, and perhaps the most profound journey of all, fatherhood. Washington catches up with KCRW’s Anne Litt on Morning Becomes Eclectic to discuss creativity in isolation, his upcoming projects, and what’s in store for the Bowl. Get tickets for this can’t-miss show here.

Read more: Kamasi Washinton on Morning Becomes Eclectic (2018)

KCRW: How does it feel to be back in front of people on the Hollywood Bowl stage, with 18,000 people there?

Kamasi Washington: “I’m super excited. I'm from LA, and there’s always something different about playing at home. And the Bowl is such an iconic venue. I remember going there and watching concerts. We used to play sometimes in the little walkway going up to the Bowl, and we’d try to sneak in with our instruments. I probably owe them a few dollars.”

Are you nervous at all?

“I mean, I am nervous. I've been playing, but I've been playing by myself. And playing by yourself and playing with 15 people on stage with you is different. I'm bringing my band. It's kind of a larger version of my band, with my dad [saxophonist Rickey Washington], and some special guests that I’m keeping a secret right now that I’m pretty sure no one’s gonna see coming. But there’ll be some big surprises for people. I'll say that much.”

Are you going to be playing new music?

“Yeah, a lot. Maybe a couple of world premieres, music that we never really played live, and some music that was released during the [pandemic].”

Have you been writing most of your new music alone, or have you been able to collaborate remotely with people?

“It was a bit of a lonesome period for me, in some regard. I recently had a daughter. And that's actually who I wrote the song “Sun Kissed Child” for. I was in a whole different kind of mode, but I was writing a lot. I didn’t get to do a lot of collabs, but I did some.”

Was that time more isolating or creative? Are they mutually exclusive?

“It was both, because I had so much time. Writing is kind of a solitary act in a lot of regards for me, in general. But the act of musically connecting with people, playing music with people, in that way, I felt pretty isolated. But creatively, I felt like I had time and space to really dive deep into some other things.”

You’re considered the leader of a new generation of jazz artists. Is there anyone coming up now who you have a lot of faith in and want to work with?

“Oh, yeah, there are tons of young musicians and musicians that I grew up with who are still waiting to have the opportunity to share their music with a really wide audience. I mean young guys like Jamael Dean, guys in my band like Brandon Coleman, who has a new record coming out pretty soon. Cameron Graves just put out an amazing new record. Miles Mosley is working on a record with Patrice Quinn. There's all kinds of new music that I'm so excited for people to hear.”

And that's all coming out of Los Angeles. I've noticed a scene in London as well. It seems like those two cities really have it all going on. Where does an artist like Hiatus Kaiyote fit into this for you?

“They're right in the middle of it. That’s just Australia. The world is such a smaller place because of technology and everything. And it just feels like everybody's kind of connected in a way that may have been different than 30, 40 years ago. We ran into them a lot on the road, and we know them. It's inspiring, because everywhere we go, there's somebody doing something cool. And when you hear music, it manifests itself into creative ideas for yourself. So hearing creative music, meeting creating people, talking to them, interacting with them, it boosts your own creativity.”

Since you haven't been able to tour this year and run into all those folks, how have you dealt with not getting that stimulation?

“I've got to get to all the things I've been wanting to do and have been working on. I'm actually working on a ballet, this really long, orchestral piece. I have this graphic novel I've been working on for quite a while. And then just being able to experiment musically in a way that was just sitting around for hours and hours, like when I was young, finding new possibilities within one chord or something like that. So that's been kind of cool.

Whereas the last five or six years, we've just been going, going, going, so that a lot of times your explorations end up only happening in between the cracks. So this time it was like I was back to being 17 again.”

Read more: MBE Throwback Session: Kamasi Washington (2015)

Where did your inspiration for the ballet come from? Are you working with a dance company?

Yeah, [choreographer, dancer, and teacher] Lula Washington

is my aunt. And I was talking to her and my cousin Tamika. We haven't

solidified yet. I'm still working on the music. I have the story in my

head. It started off as a purely musical thing, but then this story kind

of [emerged], which happens to me a lot. As I'm making music, I start

seeing things.

I’ve been in a mode of listening a lot, too. I was watching and listening to a lot of Stravinsky's ballets, and it just kind of inspired me. And it was like, ‘Well, I got this amazing dance component in my family.’ So we've high level talked about it. They’re probably going to get mad at me because I haven't really, really talked with them about it yet. So I’m kind of putting them on blast a little bit. But yeah, it’s still in the workings. I've never written a piece this long and involved before.”

Is it really different writing something that's orchestral and expansive, as opposed to writing the score for the Michelle Obama documentary “Becoming?”

“It’s just who you're serving. With this, I'm kind of serving my own thoughts. And with the documentary, I was serving Michelle Obama's thoughts, and the director Nadia Hallgren. I wouldn't say it's confining ... I've been lucky in that all the film projects I've ever worked on have all been with people who are pretty open minded, but it's still my job. And that is to find what they're trying to say and the music that frames that.

Whereas with [the ballet], it’s more like, what do I want to say? And then it also gets mixed into, what am I hearing musically? So the order of operations changes. I'm free musically to wander, find something, and then figure out, ‘What does this mean?’ … It’s like sailing the open sea to find a particular place, versus just sailing until maybe I see something way off in the distance.”

Talk about your graphic novel, because you’re also a fan of anime. Is there some connection between Los Angeles and anime? I know Flying Lotus and Thundercat are fans as well.

“Yeah, it's a trip. When we were kids, at least in South Central LA, where I grew up, anime was kind of a niche thing. Thundercat and I knew each other for years, and then we found out that we were both into anime. It was kind of like, ‘Oh, you like this too?’ That's back when you had to get someone to get a VHS from Japan. You had to have a Japanese VHS that you can then convert. It was like a whole thing, watching anime. It was a lot of bootlegs. And then it just kind of exploded. I went to Comic Con two years ago, and it was like, ‘Wow!’ It was so packed.”

What's your graphic novel about?

“Oh, it's a long story. But it's basically about a group of kids who grew up in this village. And they have this goal to challenge this guy that lives up in a mountain. They spend their whole lives training for it, and they finally get ready and go up there, and he's not there. And then they have all this power, and they have to figure out what to do with it. And that kind of leads them on this road that takes them to other worlds.”

You'll probably find some way to score that graphic novel as well, right?

“I’m sure that’s gonna happen when it gets to that level. I’m still just working on the story. Writing the story is such an interesting thing, because it's almost like I'm watching the movie and just writing down what I see [in my head]. That was the cool thing about the pandemic, was that I would have these blocks of time to just sit in a room and really dive into my psyche. It was kind of fun. It was like binge watching, almost, but in my own mind.”

What do you turn to musically when you need to be inspired or uplifted?

“When I feel depleted from inspiration, I usually look for something new, something that I haven't heard. For me, a lot of times, the spark is some new ideas or approaches. I’m someone who’s always taking risks and buying records where I don't know if they're good or not. Sometimes stuff will sit on the shelf for a little while because I'm a bit of a glutton when it comes to music, and then it’ll find its moment.

Sometimes I’ll have listened to something, but I didn't really dive deep into it, so I'll do that. And then sometimes I’ll just type some random description into YouTube and see what the matrix gives me. The other day I put in ‘Zimbabwe mbira music’ and this really beautiful piece came on. Stuff like that will just spark an idea, and then I'm often off and running again.”

“I would have these blocks of time to just sit in a room and really dive into my psyche. It was like binge watching in my own mind.” - Kamasi Washinton

Who is your horn player of choice?

“If you had to pick one star, you’d probably pick the Sun. So if I had to pick one horn player, I’d probably pick John Coltrane. But music is a personal expression, and as amazing as any person may be, no one is everyone. And everyone is someone. So as amazing as Coltrane is, you can't get what Joe Henderson has from John Coltrane.

And so for me, with certain people, you know how much of your spiritual inner space they've touched ... Coltrane has definitely been the biggest influence and the biggest inspiration for me. But I have a lot of influences from a lot of other people. Like Wayne Shorter is definitely the reason why I play saxophone. When I was a kid, I got into the Jazz Messengers, and then I heard Wayne Shorter. And at that point, I was playing clarinet. And I was just like, ‘Oh, man, I want to sound like that.’ So different people have different places in my life.”

Tell us about the new song you wrote for your daughter, “Sun Kissed Child.”

“When she was born, I had just never felt love like that. And it was instant. And it stayed with me. I was writing some music one day, and this song just kind of came to me. We are gonna play it at the Bowl. It's just special. There’s something to experiencing completely and utterly unconditional love. There's no reason behind it. There's nothing. It's just instantaneous. And you feel it and it's beautiful. It's a beautiful, amazing part of life. I'm a bit late into the game on that level, but I'm so happy and so grateful to have been able to experience that … it gives you a new hope for everything.”

Terrace Martin, Kamasi Washington, Denzel Curry share 'Racism on Trial' movement

Earlier this summer, Terrace Martin, Kamasi Washington and Denzel Curry teamed up for the groundbreaking Black Power Live virtual music festival hosted by Patrisse Cullors (co-founder of Black Lives Matter), presented by Jammcard and Form. Today, they share their collaboration as ‘Racism on Trial’ with three incredible, thought-provoking movements on YouTube, featuring Martin, Washington, Curry, Robert Glasper, Alex Isley, and more.

The Black Power Live event gathered 1.7 million viewers on it's livestream day via Twitch. With today’s release, all proceeds will go to Crenshaw Dairy Mart, Trap Heals, Transgender Law Center, Sankofa.org, and Black Men Build.

‘Racism on Trial’ follows Martin’s recent album Gray Area - Live at the JammJam, featuring the song “For Free?” which Terrace wrote with Kendrick Lamar. The album was released on Jammcard Music in partnership with Sounds of Crenshaw and Empire Distribution. Recorded at Studio A of United Recording, packed with 300 Jammcard members surrounding the performers, the album is filled with some of the most exciting and powerful jazz music created in years. The performance features Ronald Bruner Jr., Kamasi Washington, Maurice “Mobetta” Brown, Ben Wendel, Paul Cornish, and Joshua Crumbly.

For more information, visit jammcard.com

Kamasi Washington

November 8, 2018 @ 8:00 pm

Presented by Bowery Boston

Doors: 8:00 pm / Show: 9:00 pm

Kamasi Washington

When Kamasi Washington released his tour de force LP, The Epic, in 2015, it instantly set him on a path as a torchbearer for progressive, improvisational music that would open the door for new audiences to experience music unlike anything they had heard before. The 172-minute odyssey featuring his 10-piece band, The Next Step, was littered with elements of hip-hop, classical and R&B music, all major influences on the young saxophonist and bandleader, who exceeds any notions of what “jazz” music is.

Released to critical acclaim, The Epic won numerous “best of” awards, including the American Music Prize and the Gilles Peterson Worldwide album of the year. Washington followed that work with collaborations with other influential artists such as Kendrick Lamar, Run the Jewels, Ibeyi, and John Legend, and the creation of “Harmony of Difference,” a standalone multimedia installation during the 2017 Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

The fulfillment of Washington’s destiny begin when at age 13, Washington picked up his musician father’s horn and proceeded to play the Wayne Shorter composition “Sleeping Dancer Sleep On” despite never touching a saxophone or knowing how to play. After deciding to commit to his instrument, he became, lead tenor saxophone chair at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts at Alexander Hamilton High School,, where he started his first band—Young Jazz Giants—with pianist Cameron Graves, Thundercat, and Ronald Bruner, Jr.

Washington received a full scholarship to the University of California at Los Angeles, where he studied ethnomusicology. He recorded his first album with Young Jazz Giants during the summer following his freshman year. The quartet’s self-titled debut was dripping with maturity well beyond the players’ collective age, and with Washington penning four of the album’s seven original songs, became a platform to spread the “now” sound of jazz all around the country.

Following his sophomore year at UCLA, Washington went on his first national tour with West Coast hip-hop legend Snoop Dogg, performing alongside some of the most talented young musicians in the country. Later that year, the young saxophonist joined the orchestra of Gerald Wilson, one of his biggest heroes. After graduation, Washington toured with Grammy Award-winning producer, singer and songwriter Raphael Saadiq, and later that year, returned to Wilson’s band on the album In My Time.

His mass appeal continues to grow drawing vibrant, diverse, multi-generational crowds to his shows at the world’s most prominent festivals such as Coachella, Glastonbury, Fuji Rock, Bonnaroo and Primavera. A prominent journalist recently summed it up best when he wrote “in a millennium largely absent of anything new or captivating in the jazz idiom, Washington has just unleashed a musical hydra grounded in respect and intimate knowledge of the past and striking far out into a hopeful future.” Next up for Washington is the highly anticipated Harmony of Difference EP, due for release this Fall and his sophomore album slated for 2018.

***

Butcher Brown

Butcher Brown is an up-to-the minute throwback to the great progressive jazz bands of the 60s and 70s. They are a hard-working band in an era where most groups are fleeting assemblages, together only long enough to record. Their organic coherence emerges from long collaboration as a group of equals rather than a top-down, leader/sideman lineup. They are building their audience by any means necessary, combining a conventional, label-oriented approach with releasing “underground” tapes, disciplined rehearsal and engaging, adventurous performance.

This musical maturity is surprising in such a youthful band. The players in Butcher Brown were all born after the mid-70s golden age of fusion. But their modern, hip-hop-inflected funk has rich echoes of Weather Report, Return to Forever, early Earth Wind and Fire and, perhaps, a pungent whiff of Zappa. Like those bands, Butcher Brown’s unified sound comes from the intertwined talents of the four members, each bringing something unique to the mix.

https://www.theransomnote.com/music/reviews/kamasi-washington-the-epic/

THE RANSOM NOTE

Kamasi Washington - The Epic

LA resident releases monumental jazz album...

Every now and again an album comes out that blows you away. This is either because of the music, lyrics or subject matter. Kamasi Washington’s one hundred and seventy two, yes 172, minute debut album for Brainfeeder, The Epic, has all these things and more.

The album tells the story of an old guardian for a city. From his vantage point he can see a dojo. Eventually he hopes to be challenged, lose and thus hand the torch to the new guardian. One day the doors of the dojo open and three men emerge, all set on defeating the old guardian. The first challenger has speed, but not enough strength. The second has speed and strength but is not astute enough. The third, however, has speed, power and intelligence and defeats the old guardian. Sadly this has all been a dream and when the old guardian wakes up he looks at the dojo and all of the students are children. As time passes, the children do indeed become powerful enough to challenge but the old guardian has died without being defeated. This is a great story for a rock album, let alone jazz!

But who are the musicians that Washington has co-opted to tell this story and where are they from? The answer is slightly more bizarre than The Epic’s subject matter. During its mammoth existence The Epic uses a thirty two piece orchestra, a twenty piece choir and all this is underpinned by a vehemently voracious ten piece band, known as “The Next Step” or “The West Coast Get Down”. The Next Step has been meeting regularly since they were teenagers in a shed in Inglewood, South Central LA. The group consists of bassist, and Brainfeeder artist in his own right, Thundercat and his brother Ronald Bruner Jr. and Tony Austin, both on drums, Miles Mosley also on bass, Brandon Coleman on keyboards, Cameron Graves on piano, Ryan Porter on trombone and Patrice Quinn on vocals.

Right, that’s enough of who and where, what about they why? Why form the band, concoct an amazing story and release a three hour album? The answer is simple. Washington and the Next Step want to shake up jazz and make it exciting and dangerous again! The opening track 'Changing of the Guard' does this perfectly! Opening with massive horns, piano, keyboards, drums and choral vocals, it sounds like a mixture of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Sun Ra all rolled into one. The music engulfs and sweeps through you. 'Askim' slows things down pace-wise but the intensity is still there through horns and surging bass. 'Isabelle' is tender and melancholy, with slowly drawn out horns and a mournful piano. 'The Next Step' isn’t so much a track, as a statement of intent. During its fifteen minutes, the band show what they are capable of. The song skews and contorts between bop, free and big band jazz. It also foretells to what’s to come next on volume two and three of The Epic.

I could go on describing the rest of the album, but I won’t. I’ll leave that for you to explore this vast and monumental world. All I will say is that The Epic definitely lives up to its name. In the past ten years there have been good jazz albums but Washington has produced something that not only eclipses these, he obliterates them on style and deftness of playing. Washington looks like he’s set himself up for glorious career but at the back of his mind you know he’s looking down at the dojo waiting for the challengers to eventually appear.

https://brooklynrail.org/2015/11/music/the-shape-of-jazzs-past-to-come-kamasi-washingtons-the-epic

Music

The Shape of Jazz's Past to Come: Kamasi Washington's The Epic

November 2015

by Ryan

What’s there to say about Kamasi Washington that can’t be expressed in a few short words? He’s an expansive composer, and a meticulous one. In his arrangements, he matches power with restraint—which is to say, he’s patient. On record, his saxophone glides along with a mellow grace and a sharp ear for hooks. On stage, he’s affable, charismatic (though soft-spoken), exuding a sensuality checked by vague intimations of the spiritual. But above all, Kamasi Washington is confident.

This confidence is affectless and infectious. It stems largely from the decade or so he has spent as a bandleader in the Los Angeles jazz scene, but no doubt from his dozens of sessions as sideman for the likes of Ryan Adams, Robin Thicke, and Snoop Dogg as well. Paradoxical though it may sound, Washington has cultivated a will to immediacy on The Epic, his three-LP, three-hour debut, to match those of his erstwhile collaborators.

It’s a focus on audience gratification that one doesn’t commonly associate with jazz, and the pleasures that result are not unlike those of an extremely well produced Hollywood film. The Epic is bombastic and broad, bracing yet deeply familiar. Far from difficult, Washington’s compositions are highly approachable, even ensnaring—not despite their length, but in large part because of it. The variation and stamina of his drummers, Ronald Brunner Jr. and Tony Austin, bear this out on nearly every track. It’s their tenacity and invention that keep the music mobile, and restore the plot when it wanders (as it often can). Whether it’s a flare for novelty or pure danceability, this is not a band that’s shy about the beat. Washington’s solos work up against these rhythms, building intuitively into higher and more raucous spheres. It’s a gratifying if predictable pattern, deployed with variations throughout The Epic’s prodigious bulk.

I began with a question about what there was, really, to say about Washington. A look at the critics’ coverage of The Epic when it was released in May reveals a reluctance to say much, at least in a direct way. There is the requisite spot-the-influence game, the reaching abstractions, but there’s also a pervasive satisfaction with an album whose signifiers are offered so lovingly and (most importantly) safely, ripe for their own studied plucking.

This last part is only natural. Because of his pedigree—collaborations with friends Flying Lotus’s Steven Ellison and Kendrick Lamar that still overshadow his solo work—as much as his undeniable talent, Washington’s profile is higher at the moment than just about any figure in jazz. In releasing an album as ambitious, as gaudy, and as populist as The Epic, his timing was just about perfect. As much was evident the night of his packed CMJ set at Le Poisson Rouge in October, a preview for the upcoming Winter Jazzfest. Adorned in a spheroid beanie and priestly robes with solar gold lining, Washington looked every bit the acolyte of Sun Ra, although the atmosphere was more professional than prophetic. In person, the band’s dynamic is as precisely choreographed as it is in the studio. Only vocalist Patrice Quinn seems to figure as the force of jubilant chaos whose aesthetic they so openly court.

Without question, Washington’s solo set in January will be a major event, as much for jazz faithful as for those following the hype. Does Kamasi Washington’s arrival on the scene mark a turning point for mainstream culture’s downright cold reception of contemporary jazz? The answer is a resounding ‘probably not.’ The palates of receptive listeners of hip-hop and electronica will expand; many will use the album as a gateway to record store scavenger hunts, jazz clubs, and the corners of the Internet where Washington’s antecedents are given their due reverence. But as it stands, his cache is as an extension of the Brainfeeder collective (Ellison’s imprint and distributor of The Epic) rather than of any coherent jazz discourse.

Maybe this is what encapsulates my sense of Washington’s contribution and, at the same time, my fatigue in mulling it over. To listen to The Epic is not to be filled with feelings of a bright (if unwritten) future for a living art form; instead, one hears a skillful, even exhaustive renovation of older, rougher, exceedingly well-worn approaches from fusion to modal jazz. With The Epic, Washington has made jazz’s most focal contribution to the broader phenomenon of nostalgia culture.

This is a different strain of the same nostalgia for a genre’s peak creative period that we see in rock music in 2015. Expanding outward, it resonates with 'zombie formalism', the term popularized by art critic Jerry Saltz to describe a phenomenon in contemporary painting. Jazz is nowhere near as inundated with studious recapitulation, but The Epic’s warm reception feels like a (largely benign) symptom of a general hunger for the reassurances of a cultural past remembered both fondly and dimly—an indication as well of a burnout from the relentless futurism of truly forward-thinking contemporary music.

The ahistorical plasticity of Kanye West or Aphex Twin has created a gradient among the new generation for ready attachment to the past. For Lamar, it’s the g-funk era of West Coast hip hop; for Ellison, it’s his Aunt Alice as well as Herbie Hancock. For Washington, it’s Ra, and another former session collaborator, George Duke, the fusion artist most famous for his work with Frank Zappa, another former session collaborator.

Every artist interprets the continuum in which they flow. The particular interpretation Washington seems to have chosen, however, is the one of least resistance. Consider the alternative: Tyondai Braxton, whose HIVE1 is as expansive as it is claustrophobic, as conversant with Steve Reich as it is with Daniel Lopatin, as utterly lifeless in performance as it is eerily lifelike on headphones. The son of jazz-cubist visionary Anthony Braxton, Tyondai forsook a career with Battles—critical favorites and emissaries of another defunct avant-garde permutation, prog—to probe a form of music that speaks more honestly to the spirit of Ayler or Ra or even Coltrane than anything on The Epic.

None of this is to discount Washington’s achievements, which are formidable, and eminently joyous in and of themselves. Instead, it is to acknowledge that in 2015, a work of jazz, like a work of politics, cries out for follow-through. Kamasi Washington is in a rare position, possessing the talent, the momentum, and the attention necessary to create a new space for his art form—to elevate others as he was elevated, to probe his limitations like those before him, to reassert the primacy of this musical tradition. He just might do it too; he has expert timing.

Contributor

Ryan Meehan is a writer based in Brooklyn.https://tidal.com/magazine/article/a-tribute-to-ornette-coleman/1-13486

The Shape of Jazz that Came: A Tribute to Ornette Coleman

We asked Kamasi Washington to share his own thoughts on the passing of jazz legend.

On June 11, 2015, legendary American jazz innovator Ornette Coleman died at the age of 85. With his identifiable timbre and visionary drive, the saxophonist, multi-instrumentalist and composer was a critical force in the development (and coining) of the “free jazz” movement of the 1960s, remaining a revered and influential artist throughout his career. To pay tribute to Coleman’s powerful legacy, we asked Kamasi Washington to share his own thoughts on the passing of jazz legend.

* * *

My friend and bandmate Ryan Porter introduced me to the music of Ornette Coleman when I was in 9th grade.

He gave me the album The Shape of Jazz To Come and when I heard “Lonely Woman” and “Peace” they instantly became two of my favorite pieces of music.

The imagery that the music projected in my mind was so vivid it just blew me away! When I listening to them solo, it sounded as if the soloist was dictating the harmony through what they were playing instead of the changes dictating their possibilities. This idea was so amazing to me!

At this time my friend [pianist] Cameron Graves and I were both really into going outside of the chordal structures of tunes in our solos. In our high school jazz band, whenever we got a solo we would try to “go out,” and sometimes we would get lost in the form. So we would make up the chords and try to lead that into the bridge of the tune and hope that everyone would figure it out.

So when I heard Ornette and his band creating all the harmony on the spot, a light went off in my head that what Cameron and I were doing was actually cool and not a mistake!

So much to the dismay of our teachers, we started doing it on purpose. We would just change songs in whatever way we wanted and the challenge of figuring out what we were doing became our favorite way to improvise.