ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/07/eric-dolphy-1928-1964-legendary.html

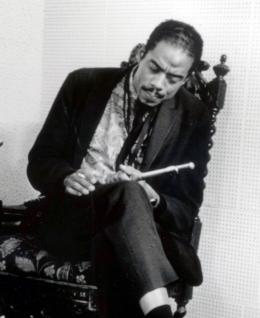

PHOTO: ERIC DOLPHY (1928-1964)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/eric-dolphy-mn0000800100#biography

Eric Dolphy

(1928-1964)

Biography by Fred Thomas

Eric Dolphy's visionary spirit left an indelible impression on jazz, especially in shaping the earliest phases of the free jazz movement, but it also affected many facets of how the artform evolved through the early '60s. A composer and multi-instrumentalist who primarily played bass clarinet, flute, and alto sax, Dolphy is often credited with bringing bass clarinet into the jazz arena, and his approach to soloing on all of his instruments pushed the boundaries of bebop until the sounds resembled something new altogether. With improvisation characterized by wide intervals, contorting notes into non-musical or speech-like sounds, and unbridled, ecstatic expression, Dolphy's playing had a huge influence on John Coltrane as he moved away from structure and into free sounds. In addition to extensive work with Chico Hamilton, Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, and others, Dolphy was a bandleader in his own right, creating new levels of excitement and abstraction on his groundbreaking Blue Note debut, 1964's Out to Lunch! Dolphy's life was tragically cut short that same year when he was just 36, his brief time on the planet impacting the entire timeline of jazz yet leaving so much unfinished.

Dolphy was born in Los Angeles in 1928. He became interested in music early in life, starting out on clarinet and receiving a scholarship to study the instrument at the University of Southern California School of Music while he was just barely into his teens. At this point he had taken up oboe and saxophone as well, and his love of classical music had him working toward a future as a symphonic musician. His earliest recordings were made in 1949 when he played flute, clarinet, and alto and baritone sax on various sessions with drummer Roy Porter. After several years in the army, Dolphy returned to Los Angeles in 1953, where he played music in various incarnations throughout the rest of the '50s. His first big break came in 1958 when he joined Chico Hamilton's band. After a year of heavy touring, Dolphy left California for New York City, where he joined Charles Mingus' band and began accelerating the development of his distinctively curious and multifaceted instrumental voice. Dolphy quickly integrated into the New York scene, playing on multiple important records and live dates with Mingus, but also contributing to landmark albums from Oliver Nelson, Ron Carter, Gunther Schuller, Booker Little, and many more, all between 1960 and 1961. Dolphy played bass clarinet on the collective improvisation that became Ornette Coleman's 1961 album Free Jazz, giving a title to the burgeoning movement. In 1961 he officially joined John Coltrane's band after sitting in on many occasions, contributing to albums like Africa/Brass and Live! At the Village Vanguard, and playing a major influential role in Coltrane's shift from hard bop to more unrestricted sounds.

Dolphy also came into his own as a leader during this time, recording a series of albums for the Prestige label beginning with formative sets such as 1960's Outward Bound and 1961's Out There. On these albums and others where he acted as a leader, Dolphy's innovations were at the fore. In addition to an uncommon fluidity between his various instruments and a playing style that was at times jarringly un-musical for its time, Dolphy was also one of the first to record unaccompanied horn solos on record, pre-dating other notable examples of this by several years. The love of classical music that had inspired him early on showed up as an influence on his compositions as well, setting him even further apart from his more traditionalist contemporaries.

After playing with Coltrane for several years, Dolphy returned to working with Mingus, playing on 1963's Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus and joining the band on tour in 1964. The same year, he signed on with Blue Note and recorded his masterwork Out to Lunch! After the completion of a European tour with Mingus in early 1964, Dolphy opted not to return to the United States, hoping to find a better reception for his music, which was often rejected or misunderstood by American audiences. While getting his bearings in Europe, he recorded, wrote, and also performed occasional gigs with friends from the states who were passing through like Donald Byrd. He made plans to join Albert Ayler's band, and to start work with Cecil Taylor and others. In June of 1964, however, Dolphy became severely ill while performing in Berlin. He was hospitalized after collapsing on-stage. Reports vary, but one account posits that when he was admitted to the hospital, doctors assumed Dolphy was suffering a drug overdose, going on the stereotype of the time that jazz musicians were largely addicts. Because of this, he was treated for an overdose and left to ride the experience out. Not only was Dolphy not a drinker, smoker, or drug user of any kind, but he was also diabetic, and he died in the hospital on June 29, 1964, after slipping into a diabetic coma, a potentially avoidable fate brought on by neglect and prejudice.

Dolphy's legacy consistently echoed throughout jazz and other circles of music long after his death. Sessions he recorded during his lifetime were released posthumously, as were a wealth of archival recordings. Peers like Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Tony Williams, and many others all leaned into progressively further out playing styles pioneered by Dolphy, and subsequent generations of avant-gardists like the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Anthony Braxton used Dolphy's influence as a jumping off point for exploration of their own. Even experimental rock musicians like Frank Zappa found inspiration in Dolphy's innovative body of work, translating his irrepressible style into non-jazz idioms. It's impossible to know what Dolphy would have accomplished had he lived into his forties, but what he did leave behind, in just a sort time, comprises multiple lifetimes' worth of monumental creation.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/eric-dolphy/

Eric Dolphy

Dolphy was one of several groundbreaking jazz alto players to rise to prominence in the 1960s. He was also the first important bass clarinet soloist in jazz, and among the earliest significant flute soloists; he is arguably the greatest jazz improviser on either instrument. On early recordings, he occasionally played traditional B-flat soprano clarinet. His improvisational style was characterized by a near volcanic flow of ideas, utilizing wide intervals based largely on the 12-tone scale, in addition to using an array of animal- like effects which almost made his instruments speak. Although Dolphy's work is sometimes classified as free jazz, his compositions and solos had a logic uncharacteristic of many other free jazz musicians of the day; even as such, he was definitively avant-garde. In the years after his death his music was more aptly described as being "too out to be in and too in to be out."

Dolphy was born in Los Angeles and was educated at Los Angeles City College. He performed locally for several years, most notably as a member of the big band led by Roy Porter. Dolphy finally had his big break as a member of Chico Hamilton's quintet, with Hamilton he became known to a wider audience and was able to tour extensively through 1958, when he parted ways with Hamilton and moved to New York City.

Dolphy wasted little time upon settling in New York City, quickly forming several fruitful musical partnerships, the two most important ones being with jazz legends Charles Mingus and John Coltrane, musicians he'd known for several years. While his formal musical collaboration with Coltrane was short (less than a year between 1961-62), his association with Mingus continued intermittently from 1959 until Dolphy's death in 1964. Dolphy was held in the highest regard by both musicians - Mingus considered Dolphy to be his most talented interpreter and Coltrane thought him his only musical equal.

Coltrane had gained an audience and critical notice with Miles Davis's quintet. Although Coltrane's quintets with Dolphy (including the Village Vanguard and Africa/Brass sessions) are now legendary, they provoked Down Beat magazine to brand Coltrane and Dolphy's music as 'anti- jazz.' Coltrane later said of this criticism "they made it appear that we didn't even know the first thing about music (...) it hurt me to see (Dolphy) get hurt in this thing."

The initial release of Coltrane's stay at the Vanguard selected three tracks, only one of which featured Dolphy. After being issued haphazardly over the next 30 years, a comprehensive box set featuring all of the recorded music from the Vanguard was released by Impulse! in 1997. The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings carried over 15 tracks featuring Dolphy on alto saxophone and bass clarinet, adding a new dimension to these already classic recordings. A later Pablo box set from Coltrane's European tours of the early 1960s collected more recordings with Dolphy for the buying public.

During this period, Dolphy also played in a number of challenging settings, notably in key recordings by Ornette Coleman (Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation), Oliver Nelson (The Blues and the Abstract Truth) and George Russell (Ezz- thetic), but also with Gunther Schuller and Max Roach among others.

Dolphy's recording career as a leader began with the Prestige label. His association with the label spanned across 13 albums recorded from April 1960 to September 1961, though he was not the leader for all of the sessions. Prestige eventually released a nine-CD box set containing all of Dolphy's recorded output for the label.

Dolphy's first two albums as leader were Outward Bound and Out There. The first is more accessible and rooted in the style of bop than some later releases, but it still offered up challenging performances, which at least partly accounts for the record label's choice to include "out" in the title. Out There is closer to the third stream music which would also form part of Dolphy's legacy, and reminiscent also of the instrumentation of the Hamilton group with Ron Carter on cello. Far Cry was also recorded for Prestige in 1960 and represented his first pairing with trumpeter Booker Little, a like-minded spirit with whom he would go on to make a set of legendary live recordings (At the Five Spot) before Little's tragic death at the age of 23.

Dolphy would record several unaccompanied cuts on saxophone, which at the time had been done only by Coleman Hawkins and Sonny Rollins before him. The album Far Cry contains one of his more memorable performances on the Gross-Lawrence standard Tenderly on alto saxophone, but it was his subsequent tour of Europe that quickly set high standards for solo performance with his exhilarating bass clarinet renditions of Billie Holiday's God Bless The Child. Numerous recordings were made of live performances by Dolphy, and these have been issued by many sometimes dubious record labels, drifting in and out of print ever since.

20th century classical music also played a significant role in Dolphy's musical career, having performed and recorded Edgard Varèse's Density 21.5 for solo flute as well as other classical works, and participated heavily in the Third Stream efforts of the 1960s.

In July 1963, Dolphy and producer Alan Douglas arranged recording sessions for which his sidemen were among the leading emerging musicians of the day. The results were his Iron Man and Conversations LPs.

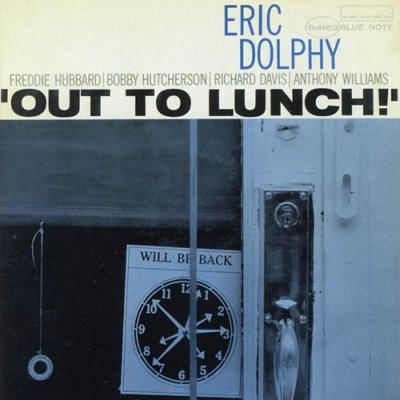

In 1964, Dolphy signed with the legendary Blue Note label and recorded Out to Lunch (once again, the label insisted on using "out" in the title). This album was deeply rooted in the avant garde, and Dolphy's solos are as dissonant and unpredictable as anything he ever recorded. Out to Lunch is often regarded not only as Dolphy's finest album, but also as one of the greatest jazz recordings ever made.

After Out to Lunch and an appearance as a sideman on Andrew Hill's Point of Departure, Dolphy left to tour Europe with Charles Mingus' sextet (one of Mingus' most underrated bands and without a doubt one of the most exciting) in early 1964. From there he intended to settle in Europe with his fiancée, who was working on the ballet scene in Paris. After leaving Mingus, he performed with and recorded a few sides with various European bands and was preparing to join Albert Ayler for a recording.

On the evening of June 28, 1964, Dolphy collapsed on the streets of Berlin and was brought to a hospital. The attending hospital physicians, who had no idea that Dolphy was a diabetic, thought that he (like so many other jazz musicians) had overdosed on drugs, so they left him to lie in a hospital bed until the "drugs" had run their course.

The notes to the Prestige nine-disc set say he "collapsed in his hotel room and when brought to the hospital he was diagnosed as being in a diabetic coma. After being administered a shot of insulin (apparently a type stronger than what was then available in the US) he lapsed into insulin shock and died."

Dolphy would die the next day in a diabetic coma, leaving a short but tremendous legacy in the jazz world, which was immediately honored with his induction into the Down Beat magazine Hall of Fame that same year. Coltrane paid tribute to Dolphy in an interview: "Whatever I'd say would be an understatement. I can only say my life was made much better by knowing him. He was one of the greatest people I've ever known, as a man, a friend, and a musician."

Dolphy's musical presence was deeply influential to a who's who of young jazz musicians who would become legends in their own right. Dolphy worked intermittently with Ron Carter and Freddie Hubbard throughout his career, and in later years he hired Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson and Woody Shaw at various times to work in his live and studio bands. Out to Lunch featured yet another young lion who had just begun working with Dolphy in drummer Tony Williams, just as his participation on the Point of Departure session brought his influence into contact with up and coming tenor man Joe Henderson.

Carter, Hancock and Williams would go on to become one of the quintessential avant-garde rhythm sections of the decade, both together on their own albums and as the backbone of the second great quintet of Miles Davis. This part of the second great quintet is an ironic footnote for Davis, who was not fond of Dolphy's music yet absorbed a rhythm section who had all worked under Dolphy and created a band whose brand of "out" was unsurprisingly very similar to Dolphy's.

In addition, his work with jazz and rock producer Alan Douglas allowed Dolphy's unique brand of musical expression to posthumously spread to musicians in the jazz fusion and rock environments, most notably with artists John McLaughlin and Jimi Hendrix. Frank Zappa, an eclectic performer who drew some of his inspiration from jazz music, paid tribute to Dolphy's style in the instrumental The Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue.

Eric Dolphy was a true original with his own distinctive styles on alto, flute, and bass clarinet. His music fell into the “avant-garde” category yet he did not discard chordal improvisation altogether (although the relationship of his notes to the chords was often pretty abstract). While most of the other “free jazz” players sounded very serious in their playing, Dolphy’s solos often came across as ecstatic and exuberant. His improvisations utilized very wide intervals, a variety of nonmusical speechlike sounds, and its own logic. Although the alto was his main axe, Dolphy was the first flutist to move beyond bop (influencing James Newton) and he largely introduced the bass clarinet to jazz as a solo instrument. He was also one of the first (after Coleman Hawkins) to record unaccompanied horn solos, preceding Anthony Braxton by five years.

Eric Dolphy first recorded while with Roy Porter & His Orchestra (1948-1950) in Los Angeles, he was in the Army for two years, and he then played in obscurity in L.A. until he joined the Chico Hamilton Quintet in 1958. In 1959 he settled in New York and was soon a member of the Charles Mingus Quartet. By 1960 Dolphy was recording regularly as a leader for Prestige and gaining attention for his work with Mingus, but throughout his short career he had difficulty gaining steady work due to his very advanced style. Dolphy recorded quite a bit during 1960-1961, including three albums cut at the Five Spot while with trumpeter Booker Little, Free Jazz with Ornette Coleman, sessions with Max Roach, and some European dates.

Late in 1961 Dolphy was part of the John Coltrane Quintet; their engagement at the Village Vanguard caused conservative critics to try to smear them as playing “anti-jazz” due to the lengthy and very free solos. During 1962-1963 Dolphy played third stream music with Gunther Schuller and Orchestra U.S.A., and gigged all too rarely with his own group. In 1964 he recorded his classic Out to Lunch for Blue Note and traveled to Europe with the Charles Mingus Sextet (which was arguably the bassist’s most exciting band, as shown on The Great Concert of Charles Mingus). After he chose to stay in Europe, Dolphy had a few gigs but then died suddenly from a diabetic coma at the age of 36, a major loss.

Virtually all of Eric Dolphy’s recordings are in print, including a nine-CD box set of all of his Prestige sessions. In addition, Dolphy can be seen on film with John Coltrane (included on The Coltrane Legacy) and with Mingus from 1964 on a video released by Shanachie. ~ Scott Yanow

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/how-eric-dolphy-deepened-my-love-of-jazz

How Eric Dolphy Sparked My Love of Jazzby Richard Brody

January 25, 2019

The New Yorker

I got into jazz because of Dave Brubeck, but jazz got into me because of Eric Dolphy. I had just turned fifteen when a random encounter with Brubeck’s music made me start listening curiously to New York’s jazz station at the time, WRVR; a few weeks later, when I heard the title tune of Dolphy’s 1960 album “Out There” on that station, it was a conversion experience. It instantly made jazz my prime artistic obsession and Dolphy my foremost musical hero. I had no idea that he was considered “out there” as an avant-gardist, revered by some and reviled by others for his musical audacity and originality—but I soon found myself delving deeply into Dolphy’s discography and then to records of other musicians directly or indirectly connected to him, such as John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Charles Mingus, and Albert Ayler.

Dolphy’s life was shockingly brief, his recorded legacy both delayed and truncated: he led only a handful of studio sessions and officially recorded concerts, starting in 1960, and he died in 1964, at the age of thirty-six. (At the time, he was in Europe, where he was planning to stay for an extended time because of critical hostility to his music in the United States and his resultant inability to pursue his career steadily here.) Nonetheless, his discography is copious, because he worked as a sideman in some major groups, including ones led by Mingus and Coltrane, and recorded generously with them—both officially and on bootlegs. There are also fine bootlegs of performances led by Dolphy—most, as a soloist with pickup rhythm sections (often, fine ones) in Europe, and a few, with his own groups, stateside.

The tracks on “Eric Dolphy, Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions,” a three-disk set, from Resonance Records, that is out on Friday, were recorded between July 1 and July 3, 1963, in New York. They were produced by Alan Douglas, a devoted and discerning producer who had previously recorded Coltrane, Taylor, Mingus, Jackie McLean, and other jazz luminaries (as well as the epochal album “Money Jungle,” featuring Duke Ellington, Max Roach, and Mingus) and would, later, record Jimi Hendrix. The Dolphy sessions were taped for Douglas’s own, short-lived record label, FM, which issued two LPs of them (“Conversations,” from 1963, and “Iron Man,” from 1968), both of which I owned and listened to excitedly, even as a teen-ager. The Resonance set includes two disks featuring the tracks from those albums, which, until now, have been available on CD only. What’s more, many hours of recordings from the week of sessions remained unissued, and “Musical Prophet” includes an entire disk-plus, eighty-five minutes’ worth, of alternate takes and also compositions that are being issued here for the first time. (It also includes a ninety-six-page booklet that’s teeming with information about and reflections on Dolphy, including interviews with Richard Davis and Sonny Simmons, two of the musicians who perform—brilliantly—on the album, and with other great musicians who knew him, including Sonny Rollins and Joe Chambers.)

Dolphy, born in Los Angeles in 1928, may have seemed like a late starter—his first major public role came in 1958, as part of the Chico Hamilton Quintet—but he was actually a precocious artist who cultivated his art devotedly, privately, and in the company of like-minded musicians who knew of his prodigious talent long before the world at large got to hear it. Dolphy practiced and studied obsessively; his fluency and proficiency rival Coltrane’s; in his years of study, he developed techniques and ideas that, when he did emerge publicly, in Hamilton’s group, were fully formed. His main instrument was alto saxophone, on which he has a full, ringing, siren-like tone that’s instantly recognizable; he also played flute, clarinet, and, especially, an instrument that hardly any other jazz musician used—the bass clarinet. His sound and style on it were so distinctive that, to this day, the instrument is closely identified with him.

Dolphy’s music emerged from the bebop revolution of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bud Powell and opened it into a new dimension. His music is tonal, largely related to the harmonic structure of the compositions he played (whether his own, other composers’, or American Songbook standards), but his sense of tonality is intricately chromatic and rendered all the more complex by his frequent, jolting leaps of wide intervals that make even harmonious lines sound disjunctive and bend the family resemblances of his solos toward modern, atonal composed music. That abstract mood is also reflected in the severe yet spontaneous logic of his solos—yet his multidimensional sense of form is as natural and intimate as breathing. Dolphy’s way with blue tones is angular, jauntily inflected, urbane; his music has the tangle and the clamor of city streets, the ferocity of crowds, the romanticism of late-night lights. At the same time, there’s an intensity to his playing that, too, is exemplary of jazz modernism; the emotional and intellectual stakes are enormous, and his sense of solitary dedication and introspective commitment provides a fierce, bright illumination.

What I thought I was hearing, when I first heard Dolphy, was intellectual realism, philosophical refractions of recognizable, passionate personal experiences; and the performances on “Musical Prophet” extend the range of those experiences beyond that of other releases. In an essay that’s included in the set’s extensive booklet, Douglas’s former associate Michaël Lemesre cites an interview in which Douglas recalled the origins of the session, the first to be made for FM: “We began with Eric Dolphy. I asked him what he wanted to record. He replied, ‘Just to play—nobody lets me make what I want—with musicians who I love.’ ” In “Musical Prophet,” Dolphy assembles an extraordinary and unusual batch of musicians, and he groups them in distinctive, revealing ways.

Dolphy’s studio recordings for other labels featured him in quartets or quintets, and, here, too, there are pieces placing Dolphy in the front line of a quintet alongside the trumpeter Woody Shaw, who was then eighteen years old and had been recruited by Dolphy to make his first recordings. Dolphy also plays several duets with the bassist Richard Davis that recall his duets with Mingus, and he plays a brief, scintillating unaccompanied piece for alto (“Love Me,” which is also heard in two wondrous alternate takes). What makes “Musical Prophet” unusual in the context of Dolphy’s oeuvre is that it includes three pieces for groups ranging from a sextet to the near-big-band assemblage of ten musicians, which also feature several powerful soloists alongside Dolphy—notably, the alto saxophonist Sonny Simmons, the flutist Prince Lasha, the saxophonist Clifford Jordan (best known for tenor, here playing soprano), and the vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson.

These compositions’ orchestrations reflect an enduring interest of Dolphy’s, one that he hardly fulfilled. For instance, in his association with Coltrane, Dolphy orchestrated the big-band arrangements on Coltrane’s “Africa/Brass” album, from 1961; in 1960, and again in 1962, he performed as a soloist in the rigorous compositional context of works by Gunther Schuller; and, as in these earlier recordings, the ensemble’s interjections in the larger-group pieces in “Musical Prophet” provide the horn soloists with brusque and complex springboards for improvisation—and suggest the broader spectrum of Dolphy’s ambitions. Some of these larger pieces feature playful arrangements (notably, of Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz” and Simmons and Lasha’s “Music Matador”) with a theatrical flair akin to that of some of Mingus’s works; others have a fierce, eruptive density that reflects his interest in modern composed music.

Yet Dolphy was never able to maintain a steady working group for long, because he could never be sure of working steadily. The prospect of developing compositions for large ensembles was even more elusive, and “Musical Prophet” offers tantalizing hints of the directions that, with a little success and a little recognition, his work might have taken. Dolphy had expressed the desire to work with Taylor, a pianist whose thunderous and crystalline abstractions also expanded to original and large-scale group concepts—albeit ones that also, for financial reasons, were realized all too rarely.

At the same time, “Musical Prophet” catches Dolphy perched on the edge of a precipice of his own seeking. For all the demanding intellectual organization of his performances, his work always stretched tensely between sound and sense. Not only did he have a distinctive tone on all of his instruments, but his search for his own world of sound was as crucial as his search for notes—and his quest for a sound that was more than one note, or wasn’t necessarily a note at all but perhaps even a shout, a growl, a roar, or a cry, wove throughout his work and occasionally blazed forth in extraordinary outbursts. The musician of the times who most ardently pursued that ideal, Albert Ayler, was also in Europe in 1964, and Dolphy, who had just left Mingus’s band, was planning to join Ayler’s group. But, in West Berlin, in June of that year, he collapsed in a diabetic coma and never emerged. It went undiagnosed: local doctors reportedly assumed that Dolphy, as a black jazz musician, had a drug problem, and never checked his blood sugar. (Dolphy didn’t use drugs; for that matter, he didn’t drink or smoke cigarettes.)

Racism is the explicit subject of one of the performances included in “Musical Prophet,” the only one that wasn’t recorded by Douglas. That piece, “A Personal Statement,” a.k.a. “Jim Crow,” is a composition by the pianist Bob James, who is white; he wrote it for a quartet (himself, Dolphy—on alto, flute, and bass clarinet—a bassist, and a drummer), along with lyrics and vocalise performed by the countertenor David Schwartz with a fervent, keening air of lamentation. It’s neither a masterwork of composition nor of poetry, but, along with Dolphy’s superb solos, it further reflects his interest in blending improvisation with composition—and the curiosity, generosity, and sense of principle and purpose that are at the core of his own art.

There are other recordings of Dolphy that I listen to more frequently than those of “Musical Prophet”—especially ones, such as “Out There,” “In Europe, Vol. 3,” and “Last Date,” on which he’s the only wind-instrument soloist and where he solos at greater length, pursuing a rare and exalted sort of introspective intensity. But “Musical Prophet” offers thrills that are unique in Dolphy’s discography. It reaches very far afield, at the vanishing point of Dolphy-ism; it crystallizes ideas latent in Dolphy’s career at that time and points far in the direction of paths that lay open in his imagination. It makes clear that his work as an itinerant soloist and as a sideman wasn’t the result of his failure to develop his own group concept but the result of economics and of politics. “Musical Prophet” also features other wonderful musicians (notably, Simmons, whose solos are among the album’s high points) alongside Dolphy, whose opportunity to play in such varied and happily assembled groups gave rise to some sequences and moments of an astounding power. In college, I blew out a speaker listening to a solo by Dolphy on one of the tracks on this set (the piece titled “Iron Man”); for all its cerebral majesty, Dolphy’s playing was, for me, also noise music, a visceral blast of musical energy that outshocked all the electric guitars in my album collection. Here’s a Spotify playlist of some of my favorites of his recordings.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Richard Brody began writing for The New Yorker in 1999. He writes about movies in his blog, The Front Row. He is the author of “Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard.”

December 28, 2008

Out There: The Music of Eric Dolphy

'When you hear music, after it's over, it's gone, into the air. You can never capture it again.'

Also featured in the Jazz Issue, comments on Eric Dolphy from Bobby Hutcherson, Sonny Rollins, Ted Curson, Peter Brotzmann, Gary Giddins, Ira Gitler and more

Click here to read an interview about Dolphy with Richard Davis

BOBBY HUTCHERSON

Vibraphonist, performed on Out to Lunch

I’m rehearsing with Eric at his loft — myself, Tony Williams, Richard Davis and a trumpet player named Eddie Armour. We were rehearsing for about an hour and a half. It was a cold winter day. All of a sudden, right in the middle of the tune, the trumpet player, Eddie, starts cussing and packing up his horn. We get to the end of the tune and Eddie says to Eric, “You’re nasty.” And Eric was real sweet, just like Trane was — you know, a real sweet cat. Eric said, “What?” Eddie says, “I don’t like you, I don’t like your music, and I’m not going to play this gig. I’m out of here. F you. F this band. That’s it. How do you like that?”

We’re all standing there thinking, “My God, how can this cat say this?” And he continues to put his horn away, clip the fasteners on his trumpet case. He grabs his coat, pulls his hat down and goes stomping to the door. He gets to the door — I mean, just yanks it open. The door hits the wall. Bam! He’s just about to go out the door.

Eric had just been sitting there with his head down. We’re all thinking, “Eric must feel horrible. What’s he going to do?” All of a sudden, Eric says, “Hey, Eddie.” Eddie turns around and says [in growling voice] “What?” Eric, with the most conviction and love, says, “If I can ever do anything you need, please don’t hesitate to call me. I’ll be there for you anytime.”

Whoa! And Eric was serious. With that, this cat really got upset — he slammed the door and stormed out. We just stood there all quiet. It was like he Sunday punched him with love. The lesson was, “Love conquers all,” you know? It’s like the devil couldn’t take that love, and this is what Eric was showing him. He went out that door with so much hate, but with a message that Eric still cared about him. This was one of the biggest lessons Eric showed me — that if you can forgive somebody right when they do the most horrible thing they can to you, you just immediately take the weight of what they did off your back and just make it this beautiful experience, so that you can go on and do the things you want to do during the day and not waste time with negative feelings and negative thoughts.

Well, we sat there quiet for two or three minutes — didn’t say anything. Then we went on with rehearsal and we never played so hard in our lives. We were just overcome. Then Eric called Freddie Hubbard, and that’s when we did Out to Lunch.

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

A TRIBUTE TO ERIC DOLPHY (1928–1964)

Reflections on the virtuoso reedman, from his formative days in Los Angeles to his last date in Berlin

Also featured in the Jazz Issue, comments on Eric Dolphy from Bobby Hutcherson, Sonny Rollins, Ted Curson, Peter Brotzmann, Gary Giddins, Ira Gitler and more

RICHARD DAVIS

Bassist, performed on Out to Lunch

and Eric Dolphy at the Five Spot, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2

For more on Richard Davis, visit his website

Stop Smiling: When did you and Eric first meet?

Richard Davis: New York, 1961.

SS: You recorded some duets with Eric, including “Ode to CP” and “Come Sunday.” Can you talk about playing with Eric one-on-one?

RD: It was a delightful experience. Eric had a lot of ideas that I needed to hear — ideas that I was, in a sense, wanting to hear, because my ear was going in that same direction.

Eric had a very even temperament. He was angelic. It’s hard to say much about Eric that isn’t close to him being an angel. He had a way about him — he was just a sweet guy. Most people would say that about him. When I met his mother and father, I could see that they must have raised him that way. They were angelic types, too. I don’t think Eric worried about things that much. He would give money to people who didn’t have any — musicians would come to town and he’d give them money. Eric was an unusual guy. You could take him groceries sometimes. Somebody told me he gave other musicians his gigs. They’d come to town and he’d give them the gig.

Eric was an exceptional human being. We had the same car — he had a Volkswagen, I had a Karmann Ghia — and I said, “I can’t get this tire changed. It’s flat.” He was instructing me with what to do. Within two minutes he said, “I’ll be right there.” He lived 40 minutes from me. He came out there and changed that tire, man. He was that kind of guy — all giving.

SS: When you met his parents, was that in California?

RD: Yeah. I told Eric I was going out there. He gave me his mother’s address and told me to say hello. He called his mother, Sadie. He had a garage out there, which had been converted into a practice studio. I was in that studio and his mother would make me a glass of lemonade from a big lemon tree.

SS: Did Eric speak with you about his interest in birds and how he tried to replicate the sounds of birds in his music?

RD: No, Eric didn’t talk to me much about that. Eric talked to me mostly about encouraging me to use my bow more.

SS: When you would spend time together in New York, what were some of the things Eric enjoyed doing other than playing?

RD: Cooking swordfish steak. It was the first I’d ever heard of a swordfish steak. He went out to the neighborhood fish market, bought it and cooked it.

SS: When you two played together in New York and wanted to go out and celebrate after a great show, what kinds of things would Eric like to do?

RD: I think Eric would probably go hear some other musicians. We used to go hear Cecil Taylor a lot because he was working in the same neighborhood we were in, the Village. Eric was not a partygoer — he would go and hear other musicians.

SS: Did Eric like New York City?

RD: I never heard him say anything against New York City.

SS: How about yourself, did you take to it?

RD:

I had no problems. I lived there for 23 years, from 1954 to 1977. I

liked it because it was a place where everything could happen in music.

One day I’m working in a sawdust, gutbucket place, the next day I’m

working with Igor Stravinsky. It all rolled there.

SS: When Eric went to play overseas, did you stay in touch?

RD:

I never traveled with Eric. I remember seeing him off when he went on

that trip. I was working at Radio City Music Hall, and I went to say

goodbye to him. I had no idea that would be the last time I’d see him.

SS: Do you remember what you talked about?

RD:

I was a very busy studio musician, and Eric was beginning to get a lot

of work recording. He said, “I’m getting like you now. I’ll have to get a

date book.” I remember giving him a watch as a going-away present. And

that was it. Next thing I know, Charles Lloyd called me. Charles thought

I knew Eric had died. He was calling to give me condolences, because he

knew how tight Eric and I were. That was the first I’d heard of it. But

then I called Eric’s father, because I didn’t want to believe it. I

couldn’t say to his father, “Is Eric dead?” I just asked him how he was.

He said, “My boy is gone.” Then I knew Eric was gone.

Eric’s

girlfriend was with him in New York at some of those gigs. She said he

was playing more than she’d ever heard him play, and she heard him a

lot. She said he was trying to get it all out.

Eric Dolphy Quintet

Outward Bound

by Sean Murphy

6 February 2007

PopMatters

It will be difficult to avoid clichés here. In their defense, clichés originate from an authentic place; they are mostly an attempt, at least initially, to articulate something honest and immutable. And so: Eric Dolphy is among the foremost supernovas in all of jazz (Clifford Brown, Booker Little and Lee Morgan—all trumpeters incidentally—also come quickly to mind): he burned very brightly and very briefly, and then he was gone. Speaking of clichés, not a single one of the artists just mentioned—all of whom left us well before their fortieth birthdays—died from a drug overdose. Dolphy, the grand old man of the bunch, passed away at the age of 36, in Europe. How? After lapsing into a diabetic coma. Why? The doctors on duty presumed the black musician who had collapsed in the street was nodding off on a heroin buzz. To attempt to put the magnitude of this loss in perspective, consider that Charles Mingus, perhaps the most difficult and demanding band leader of them all, declared Dolphy a saint, and regarded his death as one of a handful of setbacks he could never completely get over. Dolphy holds the distinction of quite possibly being the one artist nobody has gone on record to say a single negative thing about. His body of work, the bulk of which was recorded during an almost miraculously productive five-year stretch, is deep, challenging, and utterly enjoyable. Outward Bound, then, holds a special place as his debut recording as a leader.

- Eric Dolphy: "GW" Video

- Eric Dolphy: "245" Video

Music

Jazz Enigma of the ’60s Has an Encore

A New Focus on Eric Dolphy, in Washington and Montclair

MAY 27, 2014

New York Times

by BEN RATLIFF

New York Times

Though he had recorded a fair amount, especially in his last four years, culminating in the 1964 album “Out to Lunch!” and a Dutch performance recorded 27 days before his death and released as “Last Date,” there is still more to be known about what produced and drove him. Right now, a half-century after his death, might be a significant turning point. His musical papers have just been acquired by the Music Division of the Library of Congress, and his music, including pieces never performed before, will be played at a two-day festival in his honor, called Eric Dolphy: Freedom of Sound, this weekend in Montclair, N.J.

The papers were long in the possession of Dolphy’s close friends the composer Hale Smith, who died in 2009, and his wife, Juanita, who later gave them to the flutist and composer James Newton. The cache, five boxes of material, is available to scholars in the Library of Congress Performing Arts Reading Room. It includes several previously unperformed works, as well as extensions or alternative arrangements of Dolphy pieces, including “Hat and Beard,” “Gazzelloni” and “The Prophet.”

It also holds a key to how he thought and what he practiced: his transcriptions of other music, including bits of Charlie Parker and Stravinsky; Bach’s Partita in A minor for flute; and a bass-clarinet arrangement for Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1. There are also many scales of Dolphy’s own devising, which he was using as the basis for improvisation; practice books and lead sheets; and a page of transcriptions of bird calls.

“The thing that really astounded me,” Mr. Newton said recently, “was that this was a person who thought very profoundly about the organization of his music.” Dolphy wrote out hundreds of his altered or “synthetic” scales. In some cases, including on the individual parts for “Out to Lunch!,” he wrote out the unusual scales beneath the composition, as a possible basis for improvisation.

“Eric was developing multiple styles of music simultaneously,” Mr. Newton continued. “There was this highly chromatic post-bop; then music that combined elements of jazz and contemporary classical; and jazz combined with world music.” (Dolphy, along with his friend John Coltrane, was listening to Hindustani music and the songs of the so-called Pygmy peoples of Central Africa.)

The festival, organized by the drummer Pheeroan akLaff and produced by his nonprofit organization, Seed Artists, will be held this Friday and Saturday at Montclair State University. It will include some of those previously unperformed works, which Mr. Newton is reasonably sure come from the end of Dolphy’s life. It will also include other Dolphy-related music performed by several generations of musicians, including Andrew Cyrille, Henry Threadgill, Don Byron, Vernon Reid, Oliver Lake, Marty Ehrlich, David Virelles, James Brandon Lewis and Dolphy’s former bandmate the 84-year old bassist Richard Davis.Dolphy, born in 1928, played alto saxophone, bass clarinet and flute. He grew up in Los Angeles and didn’t move to New York until the age of 30 — not the standard narrative of most great figures in jazz during that time. He was an only child, and a prodigy: While still in junior high, he won a two-year scholarship to study at the music school of the University of Southern California, and his parents built him a music studio behind the house.

Dolphy came into a compositional style that used wide interval jumps in various ways, sensuous or fractured. He also organized an original improvising language, both in and out of traditional Western harmony and jazz convention. He was influenced by, among others, Parker, Art Tatum and Arnold Schoenberg, as well as the microtones and quick-pivoting phrasing of bird song.

“In my own playing,” he told the critic Martin Williams in 1960, “I am trying to incorporate what I hear. I hear other resolutions on the basic harmonic patterns, and I try to use them. And I try to get the instrument to more or less speak — everybody does.”

Toward the end of his life, Dolphy wasn’t getting enough work playing his own music. He’d been derided in the jazz press, especially after touring with Coltrane in 1961 and 1962. “He was getting criticized even by friends,” Ms. Smith said.

He left New York for Europe in early 1964, to tour with Charles Mingus. (He eventually quit that tour, determined to work on his own in Europe and to settle down with his fiancée, the dancer Joyce Mordecai, who was living in Paris.) Before leaving, he dropped off his papers and other things, including tapes and a reel-to-reel recorder, with the Smiths. The tapes yielded “Other Aspects,” an album released in 1987. But the sheet music, finally given to Mr. Newton in 2004, took a while longer to be sorted out.

Among the never previously performed pieces scheduled for the weekend are an untitled solo bass-clarinet work, to be played by Mr. Byron; a short piece for flute and bass, “To Tonio, Dead”; and “Song F.T.R.H.” and “On the Rocks,” for jazz ensembles.

Those last two were written without tempo markings, but Mr. Newton and Mr. akLaff agree that they are to be played slowly. Mr. akLaff said the pieces could be described as ceremonial music, having a “deep, dark grandeur.” (Dolphy seemed to like word puzzles; we don’t know what F.T.R.H. stands for, nor the meaning of words written in pencil on one version of the score: “Split clock birds drink wood’s angel through longhouse.”)

If Dolphy didn’t have enough cultural capital at his death to inspire a school of imitators, he became a model for how to be dedicated and curious. Mr. Lewis, 30, a saxophonist who will perform in an ensemble on Saturday, said that Dolphy suggests “a figure determined to say what he had to say at the highest level in which he had to say it.” (Like everyone who talks about Dolphy, at a certain point Mr. Lewis just had to indicate an example and listen, agog: He specified Dolphy’s bass-clarinet solo on Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train,” live with Mingus in 1964, which can be easily found on YouTube. )

“He’s just amazing,” Mr. Lewis added. “He sounds completely different than anyone else on stage, but he sounds confident.”

A version of this article appears in print on May 28, 2014, on page C1 of the New York edition with the headline: Jazz Enigma of the ’60s Has an Encore.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

His improvisational style was characterized by the use of wide intervals, in addition to employing an array of extended techniques to emulate the sounds of human voices and animals.[5][6][7] He used melodic lines that were "angular, zigzagging from interval to interval, taking hairpin turns at unexpected junctures, making dramatic leaps from the lower to the upper register."[6] Although Dolphy's work is sometimes classified as free jazz, his compositions and solos were often rooted in conventional (if highly abstracted) tonal bebop harmony.[8][9][10]

Early life, family and education

Eric Dolphy was born and raised in Los Angeles, California.[11][12] His parents were Sadie and Eric Dolphy, Sr.,[13] who immigrated to the United States from Panama.[1] He began music lessons at the age of six, studying clarinet and saxophone privately.[14] While still in junior high, he began to study the oboe, aspiring to a professional symphonic career,[14] and received a two-year scholarship to study at the music school of the University of Southern California.[12] When aged 13, he received a "Superior" award on clarinet from the California School Band and Orchestra festival.[14] He attended Dorsey High School, where he continued his musical studies and learned additional instruments.[14] By 1946, he was co-director of the Youth Choir at the Westminster Presbyterian Church run by Reverend Hampton B. Hawes, father of the jazz pianist of the same name.[14] He graduated in 1947, then attended Los Angeles City College, during which time he played contemporary classical works such as Stravinsky's L'Histoire du soldat and, along with Jimmy Knepper and Art Farmer, performed with Roy Porter's 17 Beboppers,[14] He went on to make eight recordings with Porter by 1949.[1] On these early sessions, Dolphy occasionally played baritone saxophone, as well as alto saxophone, flute and soprano clarinet.

Dolphy entered the U.S. Army in 1950 and was stationed at Fort Lewis, Washington.[15] Beginning in 1952, he attended the Navy School of Music.[7] Following his discharge in 1953, he returned to L.A., where he worked with many musicians, including Buddy Collette, Eddie Beal, and Gerald Wilson,[7] to whom he later dedicated the tune "G.W.", recorded on Outward Bound.[16] Dolphy often had friends come by to jam, enabled by the fact that his father had built a studio for him in the family's backyard.[12] Recordings made in 1954 with Clifford Brown document this early period.[17]

Dolphy had his big break when he was invited to join Chico Hamilton's quintet in 1958.[11] With the group he became known to a wider audience and was able to tour extensively through 1958–59, when he left Hamilton's group and moved to New York City.[7] Dolphy appears with Hamilton's band in the film Jazz on a Summer's Day playing flute during the Newport Jazz Festival of 1958.

Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus had known Dolphy from growing up in Los Angeles,[18] and the younger man joined Mingus' Jazz Workshop in 1960, shortly after arriving in New York.[19] He took part in Mingus' big band recording Pre-Bird (sometimes re-released as Mingus Revisited), and is featured on "Bemoanable Lady".[20] Later he joined Mingus' working band at the Showplace during 1960 (memorialized in the poem "Mingus at the Showplace" by William Matthews),[21] and appeared on the leader's two Candid label albums, Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and Mingus. Dolphy, Mingus said, "was a complete musician. He could fit anywhere. He was a fine lead alto in a big band. He could make it in a classical group. And, of course, he was entirely his own man when he soloed.... He had mastered jazz. And he had mastered all the instruments he played. In fact, he knew more than was supposed to be possible to do on them."[22] In the same year, Dolphy took part in the Mingus led Jazz Artist Guild project and its Newport Rebels recording session.[23]

Touring in Europe with Mingus in 1961, Dolphy continued on to perform as a solo artist, and he was recorded in Scandinavia and Berlin. (See The Berlin Concerts, The Complete Uppsala Concert, Eric Dolphy in Europe Volumes 1, 2, and 3 (1 and 3 were also released as Copenhagen Concert), and Stockholm Sessions.[24]) He was later among the musicians who worked on Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus in 1963, and is featured on "Hora Decubitus".

In early 1964, Dolphy returned to Mingus' working band,[7] now including Jaki Byard, Johnny Coles, and Clifford Jordan. This sextet worked at the Five Spot before playing at Cornell University and Town Hall in New York (both were recorded: Cornell 1964 and Town Hall Concert) and subsequently touring Europe. The short tour is well-documented on Revenge!, The Great Concert of Charles Mingus, Mingus in Europe Volume I, and Mingus in Europe Volume II.

Dolphy and John Coltrane knew each other long before they formally played together, having met when Coltrane was in Los Angeles with Johnny Hodges in 1954.[25][26] They would often exchange ideas and learn from each other,[27] and eventually, after many nights sitting in with Coltrane's band, Dolphy was asked to become a full member in early 1961.[28][29] Coltrane had gained an audience and critical notice with Miles Davis's quintet, but alienated some leading jazz critics when he began to move away from hard bop. Although Coltrane's quintets with Dolphy (including the Village Vanguard and Africa/Brass sessions) are now accepted, they originally provoked DownBeat magazine to brand Coltrane and Dolphy's music as 'anti-jazz'. Coltrane later said of this criticism: "they made it appear that we didn't even know the first thing about music (...) it hurt me to see [Dolphy] get hurt in this thing."[30]

The initial release of Coltrane's residency at the Vanguard selected three tracks, only one of which featured Dolphy. After being issued haphazardly over the next 30 years, a comprehensive box-set featuring the music recorded at the Vanguard was released on Impulse! in 1997, called The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings. The set features Dolphy heavily on both alto saxophone and bass clarinet, with Dolphy the featured soloist on their renditions of "Naima".[31] A 2001 Pablo box set, drawing on recordings of Coltrane's performances from his European tours of the early 1960s, features tunes absent from the 1961 Village Vanguard material, such as "My Favorite Things", which Dolphy performs on flute.[32]

Trumpeter Booker Little and Dolphy had a short-lived musical partnership.[33] Little's leader date for Candid, Out Front, featured Dolphy mainly on alto sax, though he played bass clarinet and flute on some ensemble passages. In addition, Dolphy's album Far Cry, recorded for Prestige, features Little on five tunes (one of which, "Serene", was not included on the original LP release).

Dolphy and Little also co-led a quintet at the Five Spot during 1961. The rhythm section consisted of Richard Davis, Mal Waldron and Ed Blackwell.[1] One night was documented and has been released as At the Five Spot (plus a Memorial Album) as well as the compilation Here and There. In addition, both Dolphy and Little backed Abbey Lincoln on her album Straight Ahead and played on Max Roach's Percussion Bitter Sweet. Little died at the age of 23 in October 1961.

Others

Dolphy also performed on key recordings by George Russell (Ezz-thetics), Oliver Nelson (Screamin' the Blues, The Blues and the Abstract Truth, and Straight Ahead), and Ornette Coleman (Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation and the Free Jazz outtake on Twins). He also worked and recorded with Gunther Schuller (Jazz Abstractions), multi-instrumentalist Ken McIntyre (Looking Ahead), and bassist Ron Carter (Where?).

Dolphy's recording career as a leader began with Prestige. His association with the label spanned 13 albums recorded from April 1960 to September 1961, though he was not the leader for all of the sessions. Fantasy released a 9-CD box set in 1995 containing all of Dolphy's recorded output for Prestige.[34]

Dolphy's first two albums as leader were Outward Bound and Out There; both featured cover artwork by Richard "Prophet" Jennings.[35][1] The first, sounding closer to hard bop than some later releases,[36][37] was recorded at Rudy Van Gelder's studio in New Jersey with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, who shared rooms with Dolphy for a time when the two men first arrived in New York.[38] The album features three Dolphy compositions: "G.W.", dedicated to Gerald Wilson, and the blues "Les" and "245". Out There is closer to third stream music,[39] which would also form part of Dolphy's work, and features Ron Carter on cello. Charles Mingus's "Eclipse" from this album is one of the rare instances where Dolphy solos on soprano clarinet (others being "Warm Canto" from Mal Waldron's The Quest,[40] "Densities" from the compilation Vintage Dolphy,[41] and "Song For The Ram's Horn" from an unreleased recording from a 1962 Town Hall concert).

Dolphy occasionally recorded unaccompanied saxophone solos;[42] his only predecessors were the tenor players Coleman Hawkins ("Picasso", 1948)[43] and Sonny Rollins (for example, "Body and Soul", 1958),[44] making Dolphy the first to do so on alto. The album Far Cry contains his performance of the Gross-Lawrence standard "Tenderly" on alto saxophone,[45] and, on his subsequent tour of Europe, Billie Holiday's "God Bless the Child" was featured in his sets.[46] (The earliest known version was recorded at the Five Spot during his residency with Booker Little.) He also recorded two takes of a short solo rendition of "Love Me" in 1963, released on Conversations and Muses.

Twentieth-century classical music was also part of Dolphy's musical career. He was very familiar with the music of composers such as Anton Webern and Alban Berg,[27] had a large record collection that included music by these composers, as well as by Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, and Bartók,[47] and owned scores by composers such as Milton Babbitt, Donald Erb, Charles Ives, and Olivier Messiaen.[48][49][50] He visited Edgard Varèse at his home,[51] and performed the composer's Density 21.5 for solo flute at the Ojai Music Festival in 1962.[52] Dolphy also participated in Gunther Schuller's and John Lewis's Third Stream efforts of the 1960s, appearing on the album Jazz Abstractions, and admired the Italian flute virtuoso Severino Gazzelloni, after whom he named his composition Gazzelloni.[53]

Around 1962–63, one of Dolphy's working bands included the pianist Herbie Hancock, who can be heard on The Illinois Concert, Gaslight 1962, and the unissued Town Hall concert with poet Ree Dragonette.

In July 1963, producer Alan Douglas arranged recording sessions for which Dolphy's sidemen were emerging musicians of the day, and the results produced the albums Iron Man and Conversations, as well as the Muses album released in Japan in late 2013. These sessions marked the first time Dolphy played with Bobby Hutcherson, whom he knew from Los Angeles, and whose sister he dated at one point.[54] The sessions are perhaps best known for the three duets Dolphy performs with bassist Richard Davis on "Alone Together", "Ode To Charlie Parker", and "Come Sunday"; the aforementioned release Muses adds another take of "Alone Together" and an original composition for duet from which the album takes its name.

In 1964, Dolphy signed with Blue Note Records and recorded Out to Lunch! with Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Hutcherson, Richard Davis and Tony Williams. This album features Dolphy's fully developed avant-garde yet structured compositional style rooted in tradition. It is often considered his magnum opus.[55]

European career

After Out to Lunch! and an appearance on pianist/composer Andrew Hill's Blue Note album Point of Departure, Dolphy left for Europe with Charles Mingus' sextet in early 1964. Before a concert in Oslo, Norway, he informed Mingus that he planned to stay in Europe after their tour was finished, partly because he had become disillusioned with the United States' reception of musicians who were trying something new. Mingus then named the blues they had been performing "So Long Eric". Dolphy intended to settle in Europe with his fiancée Joyce Mordecai, who was working in the ballet scene in Paris, France.[12] After leaving Mingus, he performed and recorded a few sides with various European bands, and American musicians living in Paris, such as Donald Byrd and Nathan Davis. Last Date, originally a radio broadcast of a concert in Hilversum in the Netherlands, features Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink, although it was not Dolphy's last public performance. Dolphy was also planning to join Albert Ayler's group,[11] and, according to Jeanne Phillips, quoted in A. B. Spellman's Four Jazz Lives, was preparing himself to play with Cecil Taylor.[56] He also planned to form a band with Woody Shaw, Richard Davis, and Billy Higgins,[57] and was writing a string quartet, Love Suite.[1]

Personal life and death

Dolphy was engaged to marry Joyce Mordecai, a classically trained dancer who lived in Paris.[12] He did not smoke[11] and did not use drugs or alcohol.[11][58]

Before he left for Europe in 1964, Dolphy left papers and other effects with his friends Hale Smith and Juanita Smith. Eventually much of this material was passed on to the musician James Newton.[12] It was announced in May 2014 that six boxes of music papers had been donated to the Library of Congress.[12][59]

On June 27, 1964, Dolphy traveled to Berlin, Germany, to play with a trio led by Karl Berger at the opening of a jazz club called The Tangent.[60] He was apparently seriously ill when he arrived, and during the first concert was barely able to play. He was hospitalized that night, but his condition worsened.[61] On June 29, Dolphy died after falling into a diabetic coma. While certain details of his death are still disputed, it is largely accepted that he fell into a coma caused by undiagnosed diabetes. The liner notes to the Complete Prestige Recordings box set say that Dolphy "collapsed in his hotel room in Berlin and when brought to the hospital he was diagnosed as being in a diabetic coma. After being administered a shot of insulin he lapsed into insulin shock and died". A later documentary and liner notes dispute this, saying Dolphy collapsed on stage in Berlin and was brought to a hospital. Allegedly, the attending hospital physicians did not know Dolphy was a diabetic and assumed, based on a stereotype of jazz musicians, that he had overdosed on drugs.[11] In this account, he was left in a hospital bed for the drugs to run their course.[62] Ted Curson recalled the following: "That really broke me up. When Eric got sick on that date [in Berlin], and him being black and a jazz musician, they thought he was a junkie. Eric didn't use any drugs. He was a diabetic—all they had to do was take a blood test and they would have found that out. So he died for nothing. They gave him some detox stuff and he died, and nobody ever went into that club in Berlin again. That was the end of that club."[63] Shortly after Dolphy's death, Curson recorded and released Tears for Dolphy, featuring a title track that served as an elegy for his friend.

Charles Mingus said, "Usually, when a man dies, you remember—or you say you remember—only the good things about him. With Eric, that's all you could remember. I don't remember any drags he did to anybody. The man was absolutely without a need to hurt."[22]

Dolphy was buried in Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles. His headstone bears the inscription: "He Lives In His Music."[64]

John Coltrane acknowledged Dolphy's influence in a 1962 DownBeat interview, stating: "After he sat in... We began to play some of the things we had only talked about before. Since he's been in the band, he's had a broadening effect on us. There are a lot of things we try now that we never tried before. This helped me... We're playing things that are freer than before."[65] Coltrane biographer Eric Nisenson stated: "Dolphy's effect on Coltrane ran deep. Coltrane's solos became far more adventurous, using musical concepts that without the chemistry of Dolphy's advanced style he might have kept away from the ears of his public."[66] In his book Free Jazz, Ekkehard Jost provided specific examples of how Coltrane's playing began to change during the time he spent with Dolphy, noting that Coltrane started using wider melodic intervals like sixths and sevenths, and began focusing on integrating sound coloration and multiphonics into his solos.[67] Jost contrasted Coltrane's solo on "India", recorded in November 1961 while Dolphy was with the group, and released on Impressions, with his solo on "My Favorite Things", recorded roughly a year earlier, and released on the Atlantic album,[68] and observed that on "My Favorite Things", Coltrane "accepted the mode as more or less binding, occasionally aiming away from it... at tones foreign to the scale,"[69] whereas on "India", Coltrane, like Dolphy, played "around the mode more than in it."[69]

Dolphy's musical presence was also influential to many young jazz musicians who would later become prominent. Dolphy worked intermittently with Ron Carter and Freddie Hubbard throughout his career, and in later years he hired Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson and Woody Shaw to work in his live and studio bands. Out to Lunch! featured yet another young performer, drummer Tony Williams, and Dolphy's participation on Hill's Point of Departure session brought him into contact with the tenor player Joe Henderson.

There is a celebration held at Le Moyne College based on a Frank Zappa song, "The Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue," inspired by him.

Carter, Hancock and Williams would go on to become one of the quintessential rhythm sections of the decade, both together on their own albums and as the backbone of Miles Davis's second great quintet. This aspect of the second great quintet is an ironic footnote for Davis, who was critical of Dolphy's music: in a 1964 DownBeat "Blindfold Test", Miles quipped: "The next time I see [Dolphy] I'm going to step on his foot."[70] However, Davis new quintet's rhythm section had all worked under Dolphy, thus creating a band whose brand of "out" was strongly influenced by Dolphy.

Dolphy's virtuoso instrumental abilities and unique style of jazz, deeply emotional and free but strongly rooted in tradition and structured composition, heavily influenced such musicians as Anthony Braxton,[71] members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago,[72] Oliver Lake,[73] Arthur Blythe,[74] Don Byron,[75] and Evan Parker.[76]

Dolphy was posthumously inducted into the DownBeat magazine Hall of Fame in 1964.[77] John Coltrane paid tribute to Dolphy in an interview: "Whatever I'd say would be an understatement. I can only say my life was made much better by knowing him. He was one of the greatest people I've ever known, as a man, a friend, and a musician."[78] After Dolphy died, his mother gave Coltrane his flute and bass clarinet, and Coltrane, who traveled with Dolphy's photograph, hanging it on his hotel room walls,[26] proceeded to play the instruments on several subsequent recordings.[79]

Frank Zappa acknowledged Dolphy as a musical influence in the liner notes to the 1966 album Freak Out![80] and included a Dolphy tribute entitled "The Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue" on his 1970 album Weasels Ripped My Flesh.

Pianist Geri Allen analyzed Dolphy's music for her master's thesis at the University of Pittsburgh,[81] and paid tribute to Dolphy in tunes like "Dolphy's Dance," recorded and released on her 1992 album Maroons.[82]

In 1989, Po Torch Records released an album titled "The Ericle of Dolphi," featuring Evan Parker, Paul Rutherford, Dave Holland, and Paul Lovens.[83]

In 1997, the Vienna Art Orchestra released Powerful Ways: Nine Immortal Non-evergreens for Eric Dolphy as part of its 20th anniversary box-set.[84]

In 2003, to mark what would have been Dolphy's 75th birthday, a performance was made in his honor of an original composition by Phil Ranelin at the William Grant Still Arts Center in Dolphy's hometown Los Angeles.[85] Additionally, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors designated June 20 as Eric Dolphy Day.[85]

In 2014, marking 50 years since Dolphy's death, Berlin-based pianists Alexander von Schlippenbach and Aki Takase led a project called So Long, Eric!, celebrating Dolphy's music and featuring musicians such as Han Bennink, Karl Berger, Tobias Delius, Axel Dörner, and Rudi Mahall. That year also saw a Dolphy tribute by a Berlin-based group led by Gebhard Ullmann, who had previously founded a quartet named Out to Lunch in 1983.[82] In the United States, the arts group Seed Artists presented a two-day festival entitled Eric Dolphy: Freedom of Sound in Montclair, New Jersey, that year.[12][86]

Dolphy's compositions are the inspiration for many tribute albums, including Oliver Lake's Prophet and Dedicated to Dolphy, Jerome Harris' Hidden In Plain View,[87] Otomo Yoshihide's re-imagining of Out to Lunch!,[88] Silke Eberhard's Potsa Lotsa: The Complete Works of Eric Dolphy,[89] and Aki Takase and Rudi Mahall's duo album Duet For Eric Dolphy.[90]

The ballad "Poor Eric", composed by pianist Larry Willis and appearing on Jackie McLean's 1966 Right Now! album, is dedicated to Dolphy.

Dolphy was the subject of a 1991 documentary titled Last Date, directed by Hans Hylkema, written by Hylkema and Thierry Bruneau, and produced by Akka Volta.[91][92] The film includes video clips from Dolphy's television appearances, along with interviews with the members of the Misha Mengelberg trio, with whom Dolphy recorded in June 1964, as well as commentary from Buddy Collette, Ted Curson, Jaki Byard, Gunther Schuller, and Richard Davis.

Discography

Lifetime releases

1960: Outward Bound (New Jazz, 1960)

1960: Caribé with The Latin Jazz Quintet (New Jazz, 1961)

1960: Out There (New Jazz, 1961)

1960: Far Cry (New Jazz, 1962)

1961: At the Five Spot, Vol. 1 (New Jazz, 1961) – live

1961: At the Five Spot, Vol. 2 (Prestige, 1963) – live

1963: Conversations (FM, 1963) – also released as Music Matador (Affinity)

Posthumous releases (July 1964)

1959–60: Hot & Cool Latin (Blue Moon, 1996)

1960–61: Candid Dolphy (Candid, 1989) – alternate takes from sessions as a sideman

1960–61: Fire Waltz (Prestige, 1978)[2LP] – reissue of Ken McIntyre's Looking Ahead (New Jazz, 1961) and Mal Waldron's The Quest (New Jazz, 1962)

1960–61: Dash One (Prestige, 1982) – out-takes & previously unissued

1961: Memorial Album: Recorded Live At the Five Spot (Prestige, 1965) – live

1961: The Berlin Concerts (enja, 1978) – live

1961: The Complete Uppsala Concert (Jazz Door, 1993) – initially unofficial

1960–61: Here and There (Prestige, 1966) – live

1961: Eric Dolphy in Europe, Vol. 1 (Prestige, 1964) – live

1961: Eric Dolphy in Europe, Vol. 2 (Prestige, 1965) – live

1961: Eric Dolphy in Europe, Vol. 3 (Prestige, 1965) – live. also released as Copenhagen Concert with Eric Dolphy in Europe, Vol. 1.

1961: Stockholm Sessions (Enja, 1981)

1961: 1961 (Jazz Connoisseur, ?) – live in Munich. also released as Live in Germany (Stash); Softly, As in a Morning Sunrise (Natasha Imports); Munich Jam Session December 1, 1961 by Eric Dolphy Quartet with McCoy Tyner (RLR).[93]

1962: Eric Dolphy Quintet featuring Herbie Hancock: Complete Recordings (Lone Hill Jazz, 2004) – also released as Live In New York (Stash); Left Alone (Absord); Gaslight 1962 (Get Back)

1963: The Illinois Concert (Blue Note, 1999) – live

1962–63: Vintage Dolphy (GM Recordings/enja, 1986) – live

1963: Iron Man (Douglas International, 1968) – both Conversations and Iron Man were released as Jitterbug Waltz (Douglas , 1976)[2LP]; Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions (Resonance, 2019)[3CD].

1964: Out to Lunch! (Blue Note, 1964)

1964: Last Date (Fontana, 1964) – for radio program at Hilversum

1964: Naima (Jazzway/West Wind, 1988) – for ORTF radio program at Paris

Compilation: Unrealized Tapes (West Wind) – recorded in 1964 for ORTF radio program at Paris. also released as Last Recordings and The Complete Last Recordings In Hilversum & Paris 1964 (Domino).

Compilation: Other Aspects (Blue Note, 1987) – recorded in 1960 & 64

With Ornette Coleman

1960: Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (Atlantic, 1961)

1959–61: Twins (Atlantic, 1971)

With John Coltrane

Olé Coltrane (Atlantic, 1961)

Africa/Brass (Impulse!, 1961)

Live! at the Village Vanguard (Impulse!, 1962) – rec. 1961

Impressions (Impulse!, 1963)

The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings (Impulse!, 1997) – rec. 1961

Live Trane: The European Tours (Pablo, 2001) – rec. 1961–63

The Complete Copenhagen Concert (Magnetic, -)

/Complete 1961 Copenhagen Concert (Gambit, 2009) – rec. 1961

So Many Things: The European Tour 1961 (Acrobat, 2015) – rec. 1961

Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy (Impulse!, 2023) – rec. 1961

With Chico Hamilton

1958: The Chico Hamilton Quintet with Strings Attached (Warner Bros., 1959)

1958: Gongs East! (Warner Bros., 1959)

1958: The Original Ellington Suite (Pacific Jazz, 2000)

1959: The Three Faces of Chico (Warner Bros., 1959)

1959: That Hamilton Man (SESAC, 1959)

With John Lewis

1960: The Wonderful World of Jazz (Atlantic, 1961)

1960: Jazz Abstractions (Atlantic, 1961)

1960–62: Essence (Atlantic, 1965)

With Charles Mingus

1960: Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus (Candid, 1960)

1960: Pre-Bird (Mercury, 1961) – aka Mingus Revisited

1960: Mingus (Candid, 1961)

1960: Mingus at Antibes (Atlantic, 1976) – live

1962: The Complete Town Hall Concert (Blue Note, 1994) – live

1963: Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (Impulse!, 1964)

1964: Town Hall Concert (Jazz Workshop, 1964) – live

1964: The Great Concert of Charles Mingus (America, 1971) – live

1964: Mingus in Europe Volume I (Enja, 1980) – live

1964: Mingus in Europe Volume II (Enja, 1983) – live

1964: Revenge! (Revenge, 1996) – live

1964: Cornell 1964 (Blue Note, 2007) – live

With Oliver Nelson

Screamin' the Blues (New Jazz, 1961) – rec. 1960

The Blues and the Abstract Truth (Impulse!, 1961)

Straight Ahead (New Jazz, 1961)

With Orchestra U.S.A.

Debut (Colpix, 1963)

Mack the Knife and Other Berlin Theatre Songs of Kurt Weill (RCA Victor, 1964)

With others

Clifford Brown, Clifford Brown + Eric Dolphy – Together: Recorded live at Dolphy's home, 1954 (Rare Live, 2005)

Ron Carter, Where? (New Jazz, 1961)

Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Trane Whistle (Prestige, 1960)

Sammy Davis Jr., I Gotta Right to Swing (Decca, 1960)

Phil Diaz, The Latin Jazz Quintet (United Artists, 1961)

Benny Golson, Pop + Jazz = Swing (Audio Fidelity, 1961)

Ted Curson, Plenty of Horn (Old Town, 1961)

Gil Evans, The Individualism of Gil Evans (Verve, 1964) – rec. 1963–64

Andrew Hill, Point of Departure (Blue Note, 1965) – rec. 1964

Freddie Hubbard, The Body & the Soul (Impulse!, 1963)

Abbey Lincoln, Straight Ahead (Candid, 1961)

Booker Little, Out Front (Candid, 1961)

Ken McIntyre, Looking Ahead (New Jazz, 1961)

Pony Poindexter, Pony's Express (Epic, 1962)

Max Roach, Percussion Bitter Sweet (Impulse!, 1961)

George Russell, Ezz-thetics (Riverside, 1961)

Mal Waldron, The Quest (New Jazz, 1962) – rec. 1961

Further reading

Belhomme, Guillaume. Eric Dolphy. Biographical sketches, Hofheim: Wolke Verlag, 2023. ISBN978-3-95593-146-9

Horricks, Raymond. The Importance of Being Eric Dolphy. Great Britain: D. J. Costello Publishers, 1989. ISBN0-7104-3048-5

Simosko, Vladimir and Tepperman, Barry. Eric Dolphy: A Musical Biography and Discography. New York: Da Capo Press, 1979. ISBN0-306-80107-8

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Eric Dolphy. Eric Dolphy at adale.org

Eric Dolphy session and discography at JazzDisco.org

Eric Dolphy pages by Alan Saul (archived)

Eric Dolphy Collection at the Library of Congress

Dolphy played alto saxophone, flute and bass clarinet, and outside of his own work was a favored collaborator of Chico Hamilton, John Coltrane and Charles Mingus. He died of a diabetic disorder in Berlin in 1964, at 36, four months after recording the landmark album “Out to Lunch,” which has just been released on vinyl by Blue Note records, in the first batch of the label’s year-long reissue program of its greatest records. Tickets for the festival will be available in mid-April; information is at seedartists.org.

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/eric-dolphy-freedom-of-sound#/story

Eric Dolphy: Freedom of Sound

Seed Artists has gathered world-class musicians and artists to celebrate visionary multi-instrumentalist and composer Eric Dolphy, who died 50 years ago this June. Legends of the Sixties avant garde, today’s leading innovators, from solo cello to large ensemble—the slate and scope are unrivaled. (The nightly schedules are listed at the end of the pitch.)

But it gets even better:

We are profoundly honored to debut Eric Dolphy compositions that have NEVER BEEN RECORDED, NEVER PERFORMED. They have sat unplayed for 50 years, and it is unclear if even Dolphy ever heard them played. From solo bass clarinet to a full ensemble, we will present them both nights in a world premiere of historical importance. This is Holy Grail of Jazz territory.

A Dolphy symposium will feature revelations from his personal papers that show a theoretical and conceptual sophistication far beyond what anyone had imagined. Dolphy Reborn.

And in keeping with Seed’s core mission of Great Art for Good Works, we will donate proceeds to two partner nonprofits: the Jazz Foundation of America (JFA) and the Montclair Academy of Dance and Laboratory of Music (MADLOM).

The pieces are in place, now we need to complete funding. We hope that you will help us to help others, and to make music history.

Unfamiliar with Dolphy? Check out our video at the top.

This, too.

(If you haven't already done so, click into the rectangle at the bottom center of the screen at the end of the pitch video. It's our cellphone-video tribute to Dolphy.)

As fans ourselves,

we’re counting the days (and humbled) to see and hear this unparalleled gathering of legends and young innovators. You’ll find nothing like it anywhere.

Gunther Schuller, giant of modern music? Yes.

Don Byron, Oliver Lake, Vernon Reid…a debut composition from Henry Threadgill, a birdsong suite from Diane Moser, a bass-clarinet quartet, God Bless the Child on cello…And not just music but dance from an Alvin Ailey instructor, a National Book Ward-nominated poet, photography, video--a slate and scope for the devotee and the Dolphy-curious, a tonic for the merely bored. (See the performance schedules at the end of this pitch. You'll be floored.)

A Bit About Seed Artists

Renowned drummer Pheeroan akLaff and his wife, Luz Marina Bueno, founded Seed Artists in Brooklyn in 2005. Seed used jazz and creative music to bridge cultural and generational gaps, spark community engagement, and bring the arts to at-risk youth. From music instruction at underserved schools to concerts at nursing homes and in community gardens. DIY through and through.

When Pheeroan and Luz Marina moved to Montclair, Seed was initially dormant. Then he met Chris Napierala (me) and Michael Schreiber at a yard sale, and we fell into the Jazz Wormhole

We emerged with plans to revive Seed. When we realized that this summer would mark 50 years since Dolphy’s death, and we found no planned tribute (!), we decided to do it ourselves. Absent existing funding, we put in the volunteer hours to create an event that would do Dolphy justice. A grand project, but such a significant anniversary merits an equally significant celebration.

THE SCHEDULE

FRIDAY, MAY 30 – 7pm-10:30pm

Andrew Cyrille & Pheeroan akLaff

What’s It All About, Then? Part One: Jazz, Featuring Eric Dolphy

Question: What’s it all about?

Answer: I don’t know.

But I do know a few things.

I know some of the things that make me tick.