ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/04/duke-ellington-1899-1974-legendary-and.html

PHOTO: DUKE ELLINGTON (1899-1974)

One of the greatest composers of the 20th century, and the leader for 50 years of a band that became the greatest of all jazz orchestras.

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/duke-ellington-mn0000120323#biography

Duke Ellington

(1899-1974)

Biography by William Ruhlmann

Duke Ellington was the most important composer in the history of jazz as well as being a bandleader who held his large group together continuously for almost 50 years. The two aspects of his career were related; Ellington used his band as a musical laboratory for his new compositions and shaped his writing specifically to showcase the talents of his bandmembers, many of whom remained with him for long periods. Ellington also wrote film scores and stage musicals, and several of his instrumental works were adapted into songs that became standards. In addition to touring year in and year out, he recorded extensively, resulting in a gigantic body of work that was still being assessed a quarter century after his death.

Ellington was the son of a White House butler, James Edward Ellington, and thus grew up in comfortable surroundings. He began piano lessons at age seven and was writing music by his teens. He dropped out of high school in his junior year in 1917 to pursue a career in music. At first, he booked and performed in bands in the Washington, D.C., area, but in September 1923 the Washingtonians, a five-piece group of which he was a member, moved permanently to New York, where they gained a residency in the Times Square venue The Hollywood Club (later The Kentucky Club). They made their first recordings in November 1924, and cut tunes for different record companies under a variety of pseudonyms, so that several current major labels, notably Sony, Universal, and BMG, now have extensive holdings of their work from the period in their archives, which are reissued periodically.

The group gradually increased in size and came under Ellington's leadership. They played in what was called "jungle" style, their sly arrangements often highlighted by the muted growling sound of trumpeter James "Bubber" Miley. A good example of this is Ellington's first signature song, "East St. Louis Toodle-oo," which the band first recorded for Vocalion Records in November 1926, and which became their first chart single in a re-recorded version for Columbia in July 1927.

The Ellington band moved uptown to The Cotton Club in Harlem on December 4, 1927. Their residency at the famed club, which lasted more than three years, made Ellington a nationally known musician due to radio broadcasts that emanated from the bandstand. In 1928, he had two two-sided hits: "Black and Tan Fantasy"/"Creole Love Call" on Victor (now BMG) and "Doin' the New Low Down"/"Diga Diga Doo" on OKeh (now Sony), released as by the Harlem Footwarmers. "The Mooche" on OKeh peaked in the charts at the start of 1929.

While maintaining his job at The Cotton Club, Ellington took his band downtown to play in the Broadway musical Show Girl, featuring the music of George Gershwin, in the summer of 1929. The following summer, the band took a leave of absence to head out to California and appear in the film Check and Double Check. From the score, "Three Little Words," with vocals by the Rhythm Boys featuring Bing Crosby, became a number one hit on Victor in November 1930; its flip side, "Ring Dem Bells," also reached the charts.

The Ellington band left The Cotton Club in February 1931 to begin a tour that, in a sense, would not end until the leader's death 43 years later. At the same time, Ellington scored a Top Five hit with an instrumental version of one of his standards, "Mood Indigo" released on Victor. The recording was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. As "the Jungle Band," the Ellington Orchestra charted on Brunswick later in 1931 with "Rockin' in Rhythm" and with the lengthy composition "Creole Rhapsody," pressed on both sides of a 78 single, an indication that Ellington's goals as a writer were beginning to extend beyond brief works. (A second version of the piece was a chart entry on Victor in March 1932.) "Limehouse Blues" was a chart entry on Victor in August 1931, then in the winter of 1932, Ellington scored a Top Ten hit on Brunswick with one of his best-remembered songs, "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)," featuring the vocals of Ivie Anderson. This was still more than three years before the official birth of the swing era, and Ellington helped give the period its name. Ellington's next major hit was another signature song for him, "Sophisticated Lady." His instrumental version became a Top Five hit in the spring of 1933, with its flip side, a treatment of "Stormy Weather," also making the Top Five.

The Ellington Orchestra made another feature film, Murder at the Vanities, in the spring of 1934. Their instrumental rendition of "Cocktails for Two" from the score hit number one on Victor in May, and they hit the Top Five with both sides of the Brunswick release "Moon Glow"/"Solitude" that fall. The band also appeared in the Mae West film Belle of the Nineties and played on the soundtrack of Many Happy Returns. Later in the fall, the band was back in the Top Ten with "Saddest Tale," and they had two Top Ten hits in 1935, "Merry-Go-Round" and "Accent on Youth." While the latter was scoring in the hit parade in September, Ellington recorded another of his extended compositions, "Reminiscing in Tempo," which took up both sides of two 78s. Even as he became more ambitious, however, he was rarely out of the hit parade, scoring another Top Ten hit, "Cotton," in the fall of 1935, and two more, "Love Is Like a Cigarette" and "Oh Babe! Maybe Someday," in 1936. The band returned to Hollywood in 1936 and recorded music for the Marx Brothers' film A Day at the Races and for Hit Parade of 1937. Meanwhile, they were scoring Top Ten hits with "Scattin' at the Kit-Kat" and the swing standard "Caravan," co-written by valve trombonist Juan Tizol, and Ellington was continuing to pen extended instrumental works such as "Diminuendo in Blue" and "Crescendo in Blue." "If You Were in My Place (What Would You Do?)," a vocal number featuring Ivie Anderson, was a Top Ten hit in the spring of 1938, and Ellington scored his third number one hit in April with an instrumental version of another standard, "I Let a Song Go out of My Heart." In the fall, he was back in the Top Ten with a version of the British show tune "Lambeth Walk."

The Ellington band underwent several notable changes at the end of the 1930s. After several years recording more or less regularly for Brunswick, Ellington moved to Victor. In early 1939 Billy Strayhorn, a young composer, arranger, and pianist, joined the organization. He did not usually perform with the orchestra, but he became Ellington's composition partner to the extent that soon it was impossible to tell where Ellington's writing left off and Strayhorn's began. Two key personnel changes strengthened the outfit with the acquisition of bassist Jimmy Blanton in September and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster in December. Their impact on Ellington's sound was so profound that their relatively brief tenure has been dubbed "the Blanton-Webster Band" by jazz fans. These various changes were encapsulated by the Victor release of Strayhorn's "Take the 'A' Train," a swing era standard, in the summer of 1941. The recording was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

That same summer, Ellington was in Los Angeles, where his stage musical, Jump for Joy, opened on July 10 and ran for 101 performances. Unfortunately, the show never went to Broadway, but among its songs was "I Got It Bad (And That Ain't Good)," another standard. The U.S. entry into World War II in December 1941 and the onset of the recording ban called by the American Federation of Musicians in August 1942 slowed the Ellington band's momentum. Unable to record and with touring curtailed, Ellington found an opportunity to return to extended composition with the first of a series of annual recitals at Carnegie Hall on January 23, 1943, at which he premiered "Black, Brown and Beige." And he returned to the movies, appearing in Cabin in the Sky and Reveille with Beverly. Meanwhile, the record labels, stymied for hits, began looking into their artists' back catalogs. Lyricist Bob Russell took Ellington's 1940 composition "Never No Lament" and set a lyric to it, creating "Don't Get Around Much Anymore." The Ink Spots scored with a vocal version (recorded a cappella), and Ellington's three-year-old instrumental recording was also a hit, reaching the pop Top Ten and number one on the recently instituted R&B charts. Russell repeated his magic with another 1940 Ellington instrumental, "Concerto for Cootie" (a showcase for trumpeter Cootie Williams), creating "Do Nothin' Till You Hear from Me." Nearly four years after it was recorded, the retitled recording hit the pop Top Ten and number one on the R&B charts for Ellington in early 1944, while newly recorded vocal cover versions also scored. Ellington's vintage recordings became ubiquitous on the top of the R&B charts during 1943-1944; he also hit number one with "A Slip of the Lip (Can Sink a Ship)," "Sentimental Lady," and "Main Stem." With the end of the recording ban in November 1944, Ellington was able to record a song he had composed with his saxophonist, Johnny Hodges, set to a lyric by Don George and Harry James, "I'm Beginning to See the Light." The James recording went to number one in April 1945, but Ellington's recording was also a Top Ten hit.

With the end of the war, Ellington's period as a major commercial force on records largely came to an end, but unlike other big bandleaders, who disbanded as the swing era passed, Ellington, who predated the era, simply went on touring, augmenting his diminished road revenues with his songwriting royalties to keep his band afloat. In a musical climate in which jazz was veering away from popular music and toward bebop, and popular music was being dominated by singers, the Ellington band no longer had a place at the top of the business; but it kept working. And Ellington kept trying more extended pieces. In 1946, he teamed with lyricist John Latouche to write the music for the Broadway musical Beggar's Holiday, which opened on December 26 and ran 108 performances. And he wrote his first full-length background score for a feature film with 1950's The Asphalt Jungle.

The first half of the 1950s was a difficult period for Ellington, who suffered many personnel defections. (Some of those musicians returned later.) But the band made a major comeback at the Newport Jazz Festival on July 7, 1956, when they kicked into a version of "Diminuendo and Crescendo in blue" that found saxophonist Paul Gonsalves taking a long, memorable solo. Ellington appeared on the cover of Time magazine, and he signed a new contract with Columbia Records, which released Ellington at Newport, the best-selling album of his career. Freed of the necessity of writing hits and spurred by the increased time available on the LP record, Ellington concentrated more on extended compositions for the rest of his career. His comeback as a live performer led to increased opportunities to tour, and in the fall of 1958 he undertook his first full-scale tour of Europe. For the rest of his life, he would be a busy world traveler.

Ellington appeared in and scored the 1959 film Anatomy of a Murder, and its soundtrack won him three of the newly instituted Grammy Awards, for best performance by a dance band, best musical composition of the year, and best soundtrack. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his next score, Paris Blues (1961). In August 1963, his stage work My People, a cavalcade of African-American history, was mounted in Chicago as part of the Century of Negro Progress Exposition.

Meanwhile, of course, he continued to lead his band in recordings and live performances. He switched from Columbia to Frank Sinatra's Reprise label (purchased by Warner Bros. Records) and made some pop-oriented records that dismayed his fans but indicated he had not given up on broad commercial aspirations. Nor had he abandoned his artistic aspirations, as the first of his series of sacred concerts, performed at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco on September 16, 1965, indicated. And he still longed for a stage success, turning once again to Broadway with the musical Pousse-Café, which opened on March 18, 1966, but closed within days. Three months later, the Sinatra film Assault on a Queen, with an Ellington score, opened in movie houses around the country. (His final film score, for Change of Mind, appeared in 1969.)

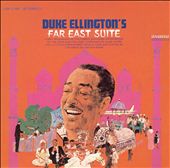

Ellington became a Grammy favorite in his later years. He won a 1966 Grammy for best original jazz composition for "In the Beginning, God," part of his sacred concerts. His 1967 album Far East Suite, inspired by a tour of the Middle and Far East, won the best instrumental jazz performance Grammy that year, and he took home his sixth Grammy in the same category in 1969 for And His Mother Called Him Bill, a tribute to Strayhorn, who had died in 1967. "New Orleans Suite" earned another Grammy in the category in 1971, as did "Togo Brava Suite" in 1972, and the posthumous The Ellington Suites in 1976.

Ellington continued to perform regularly until he was overcome by illness in the spring of 1974, succumbing to lung cancer and pneumonia. His death did not end the band, which was taken over by his son Mercer, who led it until his own death in 1996, and then by a grandson. Meanwhile, Ellington finally enjoyed the stage hit he had always wanted when the revue Sophisticated Ladies, featuring his music, opened on Broadway on March 1, 1981, and ran 767 performances.

The many celebrations of the Ellington centenary in 1999 demonstrated that he continued to be regarded as the major composer of jazz. If that seemed something of an anomaly in a musical style that emphasizes spontaneous improvisation over written composition, Ellington was talented enough to overcome the oddity. He wrote primarily for his band, allowing his veteran players room to solo within his compositions, and as a result created a body of work that seemed likely to help jazz enter the academic and institutional realms, which was very much its direction at the end of the 20th century. In that sense, he foreshadowed the future of jazz and could lay claim to being one of its most influential practitioners.

Duke Ellington

By the time of his passing, he was considered amongst the world’s greatest composers and musicians. The French government honored him with their highest award, the Legion of Honor, while the government of the United States bestowed upon him the highest civil honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He played for the royalty and for the common people and by the end of his 50-year career, he had played over 20,000 performances worldwide. He was The Duke, Duke Ellington.

Edward Kennedy Ellington was born into the world on April 29, 1899 in Washington, D.C. Duke’s parents, Daisy Kennedy Ellington and James Edward Ellington, served as ideal role models for young Duke, and taught him everything from proper table manners to an understanding of the emotional power of music. Duke’s first piano lessons came around the age of seven or eight and appeared not to have had that much lasting effect upon him. It seemed as if young Duke was more inclined to baseball at a young age.

Duke got his first job selling peanuts at Washington Senator’s baseball games. This was the first time Duke was placed as a "performer" for a crowd and had to first get over his stage fright. At the age of 14, Duke began sneaking into Frank Holliday’s poolroom. His experiences from the poolroom taught him to appreciate the value in mixing with a wide range of people.

As Duke’s piano lessons faded into the past, Duke began to show a flare for the artistic. Duke attended Armstrong Manual Training School to study commercial art instead of going to an academics-oriented school. Duke began to seek out and listen to ragtime pianists in Washington and, during the summers, in Philadelphia or Atlantic City, where he and his mother vacationed .

While vacationing in Asbury Park, Duke heard of a hot pianist named Harvey Brooks. At the end of his vacation, Duke sought Harvey out in Philadelphia where Harvey showed Duke some pianistic tricks and shortcuts. Duke later recounted that, "When I got home I had a real yearning to play. I hadn’t been able to get off the ground before, but after hearing him I said to myself, ‘Man you’re going to have to do it.’" Thus the music career of Duke Ellington was born.

Duke was taken under the wings of Oliver "Doc" Perry and Louis Brown, who taught Duke how to read music and helped improve his overall piano playing skills. Duke found piano playing jobs at clubs and cafes throughout the Washington area. Three months shy of graduation, Duke dropped out of school and began his professional music career.

In late 1917, Duke formed his first group: The Duke’s Serenaders. Between 1918 and 1919, Duke made three significant steps towards independence. First, he moved out of his parents’ home and into a home he bought for himself. Second, Duke became his own booking agent for his band. By doing so, Ellington’s band was able to play throughout the Washington area and into Virginia for private society balls and embassy parties. Finally, Duke married Edna Thompson and on March 11, 1919, Mercer Kennedy Ellington was born.

In 1923, Duke left the security that Washington offered him and moved to New York. Through the power of radio, listeners throughout New York had heard of Duke Ellington, making him quite a popular musician. It was also in that year that Duke made his first recording. Ellington and his renamed band, The Washingtonians, established themselves during the prohibition era by playing at places like the Exclusive Club, Connie’s Inn, the Hollywood Club (Club Kentucky), Ciro’s, the Plantation Club, and most importantly the Cotton Club. Thanks to the rise in radio receivers and the industry itself, Duke’s band was broadcast across the nation live on "From the Cotton Club." The band’s music, along with their popularity, spread rapidly.

In 1928, Ellington and Irving Mills signed an agreement in which Mills produced and published Ellington’s music. Recording companies like Brunswick, Columbia, and Victor came calling. Duke’s band became the most sought-after band in the United States and even throughout the world.

Some of Ellington’s greatest works include "Rockin’ in Rhythm," "Satin Doll," "New Orleans," "A Drum is a Women," "Take the 'A' Train," "Happy-Go-Lucky Local," "The Mooche," and "Crescendo in Blue."

Duke Ellington and his band went on to play everywhere from New York to New Delhi, Chicago to Cairo, and Los Angeles to London. Ellington and his band played with such greats as Miles Davis, Cab Calloway, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and Louis Armstrong. They entertained everyone from Queen Elizabeth II to President Nixon. Before passing away in 1974, Duke Ellington wrote and recorded hundreds of musical compositions, all of which will continue to have a lasting effect upon people worldwide for a long time to come.

The Jazz legend, Ellington become the first black American to be prominently featured on a U.S. coin in circulation with the release of a quarter honoring the District of Columbia.

U.S. Mint and D.C. officials celebrated the release of the coin February 2009, during a ceremony at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

“Like many great Americans who succeed in what they love doing, Duke Ellington was equal parts talent, hard work, passion and perseverance," U.S. Mint Director Ed Moy said.

The coin with Ellington resting his elbow on a piano was officially released Jan. 26,2009 but officials took time February to hand out some of the “mint condition" quarters to D.C. schoolchildren.

Monday, April 29, 2013

The Legacy of Elegance Or How Duke Ellington (and His Music) Changed the World: A Tribute To A Master On His Birthday

I submit the following question and perhaps even a wiseguy challenge to any and all possible doubters out there who should know better by now but perhaps don't (or sadly and to their own considerable loss maybe won't make the necessary effort to find out) and that is: Just how great was (and is) Duke Ellington...really? Well let's closely examine what the man and the visceral power, beauty, elegance, and sheer majesty of his artistry as conveyed through music actually accomplished in the world during the 20th century and what it just as clearly and forcefully continues to teach and inspire us in the 21st.

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington was born on April 29, 1899 in Washington D.C. After an extensive apprenticeship with a number of outstanding local teachers and musical mentors like the legendary African American classical composer and multi-instrumentalist Will Marion Cook, Ellington began his professional career as a pianist and orchestra leader in 1924 and kept his extraordinary orchestra playing and recording for an astonishing 50 years(!) until his death in 1974 at the age of 75. During his prolific career Ellington wrote over 2,000 compositions and performed in all fifty states and throughout the world many times in such major international capitols as London, Paris, Berlin, Lisbon, Rio De Janeiro, Mexico City, Toronto, Montreal, Dakar, New Delhi, and Istanbul.

Recognized by many critics throughout the world as one of the major and most important composers and musicians of the 20th century, Ellington's deep impact on other musicians and composers in many different genres of music has been immense and continues to this day. Happy Birthday Duke!

The Duke Of Ellington: The Renaissance Man Of Jazz

Ella Fitzgerald called him The Duke of Ellington; he was a true Renaissance man and one of the giants of 20th Century music – jazz or any other kind.

| |

| Play Ella Fitzgerald on Amazon Music Unlimited (ad) | |

Music publishers are not generally noted for their eloquence or their feelings towards the art that they represent, but Irving Mills had this to say about Duke Ellington. “I immediately recognized that I had encountered a great creative artist and the first American composer to catch in his music the true jazz spirit.” Duke Ellington was born on April 29, 1899, and passed away on May 24, 1974, and he embodied jazz like few others.

The Duke’s jazz was innovative with arrangements that featured his piano playing against a rich, deep sound played by the brilliant musicians that he always had in his orchestra. Over five hundred of the best jazz musicians in the world passed through his ranks; rarely was anyone fired because he hired the best. At the same time, he wrote wonderful and popular songs, extended jazz works, suites and also gave sacred concerts. Versatility was what the Duke was all about – Duke Ellington was the renaissance man of jazz.

Listen to the best of Duke Ellington on Apple Music and Spotify.

Becoming the “Duke”

Edward Kennedy Ellington’s father was a butler in a house not far from the White House; he wanted his son to become an artist. Ellington senior expected his children to behave themselves, to dress and speak according to their upbringing, which was much better than most of young Edward’s future colleagues. He began studying piano when he was seven or eight; back then ragtime was about as jazzy as things got in the Capital. He learned to read music early on, which helped him to achieve greatness later on.

It was when he was a teenager that he first became known as “Duke”; he was described as being somewhat detached back then, maybe even a little haughty. He made his professional debut as a teenager in 1916 having learned ragtime piano from a pianist named Doc Perry; even before he made his debut he had composed his first rag. He played in the Capitol’s nightspots with a small group that included drummer Sonny Greer, who worked with The Duke for many years.

In 1922 he took his trio to New York City to work, but it was a failure. Encouraged to return the following year by Fats Waller he took his Washingtonians to a job at Barron’s in Harlem; a few months later they were uptown at the Kentucky Club on Broadway. Soon the Duke was working up more complicated arrangements as well as experimenting with his own material.

His first taste of success

Not long after Duke began to find success in New York he decided he needed a manager. Irving Mills, a music publisher and all-around man about music proved to be the right choice when he secured the prestigious gig at the Cotton Club. When they opened, the band was a ten-piece having been joined by clarinetist Barney Bigard, along with saxophonists, Johnny Hodges on alto and Harry Carney on baritone.

The Washingtonians had first recorded back in November 1924 and over the next couple of years cut a few more sides. It wasn’t until 1926, when Duke was being billed as Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra, that he really started to show promise in the studio with “It Was A Night In Harlem” and the first rendition of East St Louis “Toodle-o” ; a later version of this with “Toodle-oo” on the end made the Billboard best-seller list. Over the next two to three years the Ellington Orchestra was rarely out of the studio; Creole Love Call, Black and Tan Fantasy, and The Mooche all made the Billboard chart.

Pivotal to Duke’s success were his radio broadcasts from the Cotton Club, which carried his name directly into homes all across America on the CBS network, which had been formed in 1927. As the 1920s came to an end Ellington’s orchestra were not just known in America; word had spread to Europe and Britain. In June 1931 Ellington was in a studio in Camden, New Jersey to record one of his most ambitious records – “Creole Rhapsody.”

It took up both sides of a 78-rpm record, something completely new for a jazz band; this is what classical orchestras did. It certainly gives some insight into what Ellington was thinking and we can only speculate what he might have done had better technology been available. He went on to create many extended works during the 1930s, the most creative period of his entire career.

Finding international fame

Ellington eventually left the Cotton Club and began appearing in cities all over America. In 1933 he embarked upon his most ambitious tour, crossing the Atlantic to appear in Britain. The Duke’s records sold in large numbers, particularly in, “London and university cities,” according to the press. He appeared at the London Palladium for the first time on June 12, 1933, and was afforded a “wildly enthusiastic welcome.” Among those in the audience was Nesuhi Ertegun who had taken his younger brother Ahmet to witness “the King of Jazz” as the newspapers dubbed the Duke; Ahmet would later co-found Atlantic Records.

The 1930s saw some of the Duke’s biggest selling records including, “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” “Sophisticated Lady,” “Stormy Weather,” “Cocktails for Two,” “Solitude” and “Caravan.” On many of these records, as well as Ellington’s 1933 trip to London, were some outstanding musicians, included Barney Bigard on clarinet, Cootie Williams on trumpet, and Ben Webster on tenor sax.

“Duke Ellington was the real pioneer in jazz concerts.” – Norman Granz

By the time Ellington returned to Britain in 1939 Billy Strayhorn, Duke’s longtime collaborator, had joined the band as arranger, composer, and second pianist. He added yet more depth and variety to the Ellington sound. The tours in the USA had got bigger and more lavish as the years went by. Instead of traveling by bus, like most bands, “Duke Ellington’s Famous Orchestra,” as they were billed, traveled in their own Pullman car. This was not the inspiration for one of the band’s most famous records, “Take The A Train,” which they recorded in Hollywood in January 1941. The song, written by Billy Strayhorn, which has become synonymous with the band, as well as becoming their signature tune, was actually about the New York subway.

Creating a jazz anthem

“Take The A Train” was just one of a whole string of amazing recordings made between 1939 and 1942; the orchestra were at their absolute best. But even these were to be eclipsed by the Duke’s first really long work – “Black, Brown and Beige” – which had its premiere at Carnegie Hall in November 1943. The inspiration behind the piece was to tell the story of African-Americans and their struggle. It was the first in a series of concerts, which showcased Ellington’s longer works. While the Duke was not the first jazz musician to have played at Carnegie Hall, his was the most ambitious musical programme.

With the strictures of war, followed by the decline in interest in big bands, Ellington’s Orchestra was no different to almost any other in that there were fewer opportunities on both record and in concert. Fortunately, Ellington was better placed than the others in that he had his song publishing affairs well managed. It meant that the royalties from songwriting were subsidizing his band, to some extent. “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” “Mood Indigo” and “Sophisticated Lady” were just three of the compositions that earned significant sums, running well into six figures for each song, even during the 1940s.

The end of the big band era

By the early 1950s things had become much worse for all of the big bands, Ellington in particular suffered when he lost two of his stalwarts – Johnny Hodges and Sonny Greer; for a while it seemed that the Duke might actually fold his touring band altogether. However the advent of the long-playing record allowed Duke to focus his composing efforts on increasingly interesting pieces. At the same time there were also foreign tours but things certainly weren’t what they used to be.

Then in 1956, there was something of a revival in the Orchestra’s fortunes, beginning with an appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival in July. With new saxophonist Paul Gonsalves playing a six-minute solo on Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue, a piece dating from the late Thirties, the Ellington Orchestra took the festival by storm.

They were helped too by the return to the fold of Johnny Hodges and a new record deal with Columbia Records that released “Ellington at Newport” and sold a hat full. On the back of this resurgence another major European tour in 1958 gave the band a renewed international status that had been in danger of ebbing away. Ellington and Strayhorn also wrote the score for the film Anatomy of a Murder in 1959, which added another level of interest in what they were doing.

Embraced by a new jazz generation

In the early 60s, Ellington also worked with some younger jazz stars, including, Charles Mingus and John Coltrane, which helped to introduce him to a new generation of fans recently brought into the jazz fold by this new breed of musicians. But it wasn’t just the new breed that were acknowledging the Duke; Ella Fitzgerald recorded her songbook tribute to Ellington – it was a master class.

In 1965 he recorded his first concert of sacred music, which met with mixed reviews; a fact that did nothing to deter the Duke from reprising it all over the world on numerous occasions. At the other end of the musical spectrum, he did the music for a Frank Sinatra film called Assault On A Queen; the music was much better than the movie but it did not feature Sinatra singing. The following year the Ellington Orchestra worked on an album with Frank called “Francis A and Edward K.” This unique collaboration went almost unnoticed at the time of its release, failing to even make the Top 40 album chart; it was THE voice alongside one of THE great jazz orchestras.

Among the songs they recorded was the beautiful “Indian Summer” with a stunning arrangement by Billy May that is both reflectively modern, and at the same time old fashioned, as befits a song written in 1919. It is one of the best songs Frank ever recorded for Reprise. Johnny Hodges sax solo certainly adds to the overall effect and so enthralled was Sinatra during its recording that when it ends he’s half a second late in coming in to sing. Hodges died two years later and this was a fitting elegy to great saxophonist.

In 1969, Ellington received the Medal of Freedom at the White House; it would certainly have shocked his father, but possibly not. Come the 1970s and Ellington was working all around the world. This included a tour of Russia in 1971 and a concert in Westminster Abbey in London in December 1973 that featured his sacred music. The Duke was suffering from lung cancer by this time and he died on 24 May 1974.

Unquestionably, Duke Ellington was one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. He sold records in large quantities and created a sound that was all his own for which jazz will forever be the richer.

Listen to Duke Ellington’s rich catalogue here.

“Jazz is the freest musical expression we have yet seen. To me, then, jazz means simply freedom of musical speech! And it is precisely because of this freedom that so many varied forms of jazz exist. The important thing to remember, however, is that not one of these forms represents jazz by itself. Jazz simply means the freedom to have many forms.”

—Duke Ellington, 1947

https://www.vermontpublic.org/programs/2013-04-29/reuben-jackson-on-duke-ellington

Reuben Jackson On Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington was the composer of American jazz standards such as Mood Indigo, sumptuous extended works like The Afro Eurasian Eclipse, The Far East Suite and three Sacred Concerts. He was also the consummate multitasker.

If I learned anything during my 20 year stint as archivist and curator with the Smithsonian's Duke Ellington Collection, it was this: It was not uncommon for the Washington, D.C. native to juggle studio sessions, new compositions, interviews, meetings, concert dates, friends, fans and, yes, romantic interests. He was not the central casting isolated artist seeking the muse in, say, some remote corner of Vermont's Northeast Kingdom. Humanity was his Walden Pond.

Still, it's one thing to be a multitasker. It's another to multitask with the deceptively casual attention and intense focus Ellington gave to each part of his life. Ellington loved people; he said the key to accomplishing as much as he did was "mental isolation."

When cataloging the sound recordings in the Smithsonian's collection, I still wondered how he managed to gracefully handle dozens of inane press conference questions about "jazz," a word he abhorred, then lead his Orchestra through an accessible yet musically radical reworking of an Ellington standard like "Mood Indigo" a few hours later. I have no idea how he did this with such unfailing grace—and I probably never will.

As some of you in the VPR listening audience know, I am also currently employed as an English teacher at Burlington High School. On average, I see an average of 35 students with very different personalities, interests and needs every day. By contrast, Ellington worked with groups of varying sizes, skills, and issues (curmudgeons, kleptomaniacs, some addicts) for nearly 50 years. More importantly, he consistently got the best out of these ensembles. Even "students" who disliked him intensely reveled in the time spent with the man they called The Maestro. (And I have the nerve to pant like an exhausted marathon runner on Friday afternoon!)

If Duke Ellington were reading this, he might utter one of his frequently-used axioms: "Don't let your intelligence get in the way of your learning." With that in mind, I'll cease with the first person reflections (I've commented at length about Ellington and some of his contemporaries in this VPR Presents lecture), and share that which mattered most to Duke Ellington: The music.

Below you'll find video of a couple of my favorites and a bibliography of reading and listening. You'll also hear something composed, performed or inspired by Ellington every week on my show.

-- Reuben Jackson, Host of Friday Night Jazz

Here's a solo piano rendition of "Le Sucrier Velour"—a movement from 1959's "The Queen's Suite.":

The second Ellington composition is entitled "Chinoserie" It is the opening movement from 1971's "Afro Eurasian Eclipse"—complete with Ellington's silver, no, platinum-tongued introduction:

All are but a taste of the mad skills (as the rappers say) Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington possessed—and continues to share with the world.

Recommended Reading

- Cohen, Harvey G. Duke Ellington's America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Ellington, Duke. Music Is My Mistress. New York: Da Capo, 1976,

- Ellington, Mercer. Duke Ellington In Person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978.

Recordings

- Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. The Ellington Suites.

- Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. And His Mother Called Him Bill.

- Duke Ellington-The Far East Suite-Special Mix

http://www.redhotjazz.com/duke.html

EDWARD "DUKE" ELLINGTON (1899-1974)

Duke Ellington brought a level of style and sophistication to Jazz that it hadn't seen before. Although he was a gifted piano player, his orchestra was his principal instrument. Like Jelly Roll Morton before him, he considered himself to be a composer and arranger, rather than just a musician. Duke began playing music professionally in Washington, D.C. in 1917. His piano technique was influenced by stride piano players like James P. Johnson and Willie "The Lion" Smith. He first visited New York in 1922 playing with Wilbur Sweatman, but the trip was unsuccessful. He returned to New York again in 1923, but this time with a group of friends from Washington D.C. They worked for a while with banjoist Elmer Snowden until there was a disagreement over missing money. Ellington then became the leader. This group was called The Washingtonians. This band worked at The Hollywood Club in Manhattan (which was later dubbed the Kentucky Club). During this time Sidney Bechet played briefly with the band (unfortunately he never recorded with them), but more significantly the trumpet player Bubber Miley joined the band, bringing with him his unique plunger mute style of playing. This sound came to be called the "Jungle Sound", and it was largely responsible for Ellington's early success. The song "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo" is a good example of this style of playing. The group recorded their first record in 1924 ("Choo Choo (Gotta Hurry Home)" and "Rainy Nights (Rainy Days)", but the band didn't hit the big time until after Irving Mills became their manager and publisher in 1926. In 1927 the band re-recorded versions of "East St.Louis Toodle-Oo," debuted "Black and Tan Fantasy" and "Creole Love Call", songs that would be associated with him the for rest of his career, but what really put Ellington's Orchestra over the top was becoming the house band at the Cotton Club after King Oliver unwisely turned down the job. Radio broadcasts from the club made Ellington famous across America and also gave him the financial security to assemble a top notch band that he could write music specifically for. Musicians tended to stay with the band for long periods of time. For example, saxophone player Harry Carney would remain with Duke nonstop from 1927 to Ellington's death in 1974. In 1928 clarinetist Barney Bigard left King Oliver and joined the band. Ellington and Bigard would later co-write one of the orchestra's signature pieces "Mood Indigo" in 1930. In 1929 Bubber Miley, was fired from the band because of his alcoholism and replaced with Cootie Williams. Ellington also appeared in his first film "Black and Tan" later that year. The Duke Ellington Orchestra left the Cotton Club in 1931 (although he would return on an occasional basis throughout the rest of the Thirties) and toured the U.S. and Europe.

Unlike many of their contemporaries, the Ellington Orchestra was able to make the change from the Hot Jazz of the 1920s to the Swing music of the 1930s. The song "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)" even came to define the era. This ability to adapt and grow with the times kept the Ellington Orchestra a major force in Jazz up until Duke's death in the 1970s. Only Louis Armstrong managed to sustain such a career, but Armstrong failed to be in the artistic vanguard after the 1930s . Throughout the Forties and Fifties Ellington's fame and influence continued to grow. The band continued to produce Jazz standards like "Take the 'A' Train", "Perdido", "The 'C' Jam Blues" and "Satin Doll". In the 1960s Duke wrote several religious pieces, and composed "The Far East Suite". He also collaborated with a very diverse group of musicians whose styles spanned the history of Jazz. He played in a trio with Charles Mingus and Max Roach, sat in with both the Louis Armstrong All-Stars and the John Coltrane Quartet, and he had a double big-band date with Count Basie. In the 1970s many of Ellington's long time band members had died, but the band continued to attract outstanding musicians even after Ellington's death from cancer in May, 1974, when his son Mercer took over the reins of the band.

SUGGESTED READING:

Duke Ellington In Person by Mercer Ellington with Stanley Dance, Da Capo Press, 1988

Ellington: The Early Years, Mark Tucker, 1995

Beyond Category : The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington by John Edward Hasse (Introduction by Wynton Marsalis), 1995, Da Capo Press

The World of Duke Ellington by Stanley Dance, 1981, Da Capo Press

The Duke Ellington Reader by Mark Tucker, 1995, Oxford University Press

Duke Ellington's America by Harry G. Cohen, 2010,

University of Chicago Press

Duke Ellington and His World: Biography by A. H. LawrenceRoutledge, 2001

Duke Ellington

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life.[1]

Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was based in New York City from the mid-1920s and gained a national profile through his orchestra's appearances at the Cotton Club in Harlem. A master at writing miniatures for the three-minute 78 rpm recording format, Ellington wrote or collaborated on more than one thousand compositions; his extensive body of work is the largest recorded personal jazz legacy, and many of his pieces have become standards. He also recorded songs written by his bandsmen, such as Juan Tizol's "Caravan", which brought a Spanish tinge to big band jazz.

At the end of the 1930s, Ellington began a nearly thirty-year collaboration with composer-arranger-pianist Billy Strayhorn, whom he called his writing and arranging companion.[2] With Strayhorn, he composed multiple extended compositions, or suites, as well as many short pieces. For a few years at the beginning of Strayhorn's involvement, Ellington's orchestra featured bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster and reached a creative peak.[3] Some years later following a low-profile period, an appearance by Ellington and his orchestra at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1956 led to a major revival and regular world tours. Ellington recorded for most American record companies of his era, performed in and scored several films, and composed a handful of stage musicals.

Although a pivotal figure in the history of jazz, in the opinion of Gunther Schuller and Barry Kernfeld, "the most significant composer of the genre",[4] Ellington himself embraced the phrase "beyond category", considering it a liberating principle, and referring to his music as part of the more general category of American Music.[5] Ellington was known for his inventive use of the orchestra, or big band, as well as for his eloquence and charisma. He was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize Special Award for music in 1999.[6]

Early life and education

Ellington was born on April 29, 1899, to James Edward Ellington and Daisy (née Kennedy) Ellington in Washington, D.C. Both his parents were pianists. Daisy primarily played parlor songs, and James preferred operatic arias.[7] They lived with Daisy's parents at 2129 Ida Place (now Ward Place) NW, in D.C.'s West End neighborhood.[8] Duke's father was born in Lincolnton, North Carolina, on April 15, 1879, and in 1886, moved to D.C. with his parents.[9] Daisy Kennedy was born in Washington, D.C., on January 4, 1879, the daughter of two former American slaves.[8][10] James Ellington made blueprints for the United States Navy.

When Ellington was a child, his family showed racial pride and support in their home, as did many other families. African Americans in D.C. worked to protect their children from the era's Jim Crow laws.[11]

At the age of seven, Ellington began taking piano lessons from Marietta Clinkscales.[7] Daisy surrounded her son with dignified women to reinforce his manners and teach him elegance. His childhood friends noticed that his casual, offhand manner and dapper dress gave him the bearing of a young nobleman,[12] so they began calling him "Duke". Ellington credited his friend Edgar McEntee for the nickname: "I think he felt that in order for me to be eligible for his constant companionship, I should have a title. So he called me Duke."[13]

Though Ellington took piano lessons, he was more interested in baseball. "President [Theodore] Roosevelt would come on his horse sometimes, and "stop and watch us play," he recalled.[14] Ellington went to Armstrong Technical High School in Washington, D.C. His first job was selling peanuts at Washington Senators baseball games.

Ellington started sneaking into Frank Holiday's Poolroom at age fourteen. Hearing the music of the poolroom pianists ignited Ellington's love for the instrument, and he began to take his piano studies seriously. Among the many piano players he listened to were Doc Perry, Lester Dishman, Louis Brown, Turner Layton, Gertie Wells, Clarence Bowser, Sticky Mack, Blind Johnny, Cliff Jackson, Claude Hopkins, Phil Wurd, Caroline Thornton, Luckey Roberts, Eubie Blake, Joe Rochester, and Harvey Brooks.[15]

In the summer of 1914, while working as a soda jerk at the Poodle Dog Café, Ellington wrote his first composition, "Soda Fountain Rag" (also known as the "Poodle Dog Rag"). He created the piece by ear, as he had not yet learned to read and write music. "I would play the 'Soda Fountain Rag' as a one-step, two-step, waltz, tango, and fox trot", Ellington recalled. "Listeners never knew it was the same piece. I was established as having my own repertoire."[16] In his autobiography, Music is my Mistress (1973), Ellington wrote that he missed more lessons than he attended, feeling at the time that piano was not his talent.

Ellington continued listening to, watching, and imitating ragtime pianists, not only in Washington, D.C. but also in Philadelphia and Atlantic City, where he vacationed with his mother during the summer.[16] He would sometimes hear strange music played by those who could not afford much sheet music, so for variations, they played the sheets upside down.[17] Henry Lee Grant, a Dunbar High School music teacher, gave him private lessons in harmony. With the additional guidance of Washington pianist and band leader Oliver "Doc" Perry, Ellington learned to read sheet music, project a professional style, and improve his technique. Ellington was also inspired by his first encounters with stride pianists James P. Johnson and Luckey Roberts. Later in New York, he took advice from Will Marion Cook, Fats Waller, and Sidney Bechet. He started to play gigs in cafés and clubs in and around Washington, D.C. His attachment to music was so strong that in 1916 he turned down an art scholarship to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Three months before graduating, he dropped out of Armstrong Manual Training School, where he was studying commercial art.[18]

Career

Early career

Working as a freelance sign painter from 1917, Ellington began assembling groups to play for dances. In 1919, he met drummer Sonny Greer from New Jersey, who encouraged Ellington's ambition to become a professional musician. Ellington built his music business through his day job. When a customer asked him to make a sign for a dance or party, he would ask if they had musical entertainment; if not, Ellington would offer to play for the occasion. He also had a messenger job with the U.S. Navy and State departments, where he made a wide range of contacts.

Ellington moved out of his parents' home and bought his own as he became a successful pianist. At first, he played in other ensembles, and in late 1917 formed his first group, "The Duke's Serenaders" ("Colored Syncopators", his telephone directory advertising proclaimed).[18] He was also the group's booking agent. His first play date was at the True Reformer's Hall, where he took home 75 cents.[19]

Ellington played throughout the D.C. area and into Virginia for private society balls and embassy parties. The band included childhood friend Otto Hardwick, who began playing the string bass, then moved to C-melody sax and finally settled on alto saxophone; Arthur Whetsel on trumpet; Elmer Snowden on banjo; and Sonny Greer on drums. The band thrived, performing for both African-American and white audiences, rare in the segregated society of the day.[20]

When his drummer Sonny Greer was invited to join the Wilber Sweatman Orchestra in New York City, Ellington left his successful career in D.C. and moved to Harlem, ultimately becoming part of the Harlem Renaissance.[21] New dance crazes such as the Charleston emerged in Harlem, as well as African-American musical theater, including Eubie Blake's and Noble Sissle's (the latter of whom was his neighbor) Shuffle Along. After the young musicians left the Sweatman Orchestra to strike out on their own, they found an emerging jazz scene that was highly competitive with difficult inroad. They hustled pool by day and played whatever gigs they could find. The young band met stride pianist Willie "The Lion" Smith, who introduced them to the scene and gave them some money. They played at rent-house parties for income. After a few months, the young musicians returned to Washington, D.C., feeling discouraged.

In June 1923, they played a gig in Atlantic City, New Jersey and another at the prestigious Exclusive Club in Harlem. This was followed in September 1923 by a move to the Hollywood Club (at 49th and Broadway) and a four-year engagement, which gave Ellington a solid artistic base. He was known to play the bugle at the end of each performance. The group was initially called Elmer Snowden and his Black Sox Orchestra and had seven members, including trumpeter James "Bubber" Miley. They renamed themselves The Washingtonians. Snowden left the group in early 1924, and Ellington took over as bandleader. After a fire, the club was re-opened as the Club Kentucky (often referred to as the Kentucky Club).

Ellington then made eight records in 1924, receiving composing credit on three including "Choo Choo".[22] In 1925, Ellington contributed four songs to Chocolate Kiddies starring Lottie Gee and Adelaide Hall,[citation needed] an all-African-American revue which introduced European audiences to African-American styles and performers. Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra grew to a group of ten players; they developed their own sound via the non-traditional expression of Ellington's arrangements, the street rhythms of Harlem, and the exotic-sounding trombone growls and wah-wahs, high-squealing trumpets, and saxophone blues licks of the band members. For a short time, soprano saxophonist and clarinetist Sidney Bechet played with them, reportedly becoming the dominant personality in the group, with Sonny Greer saying Bechet "fitted out the band like a glove". His presence resulted in friction with Miley and trombonist Charlie Irvis, whose styles differed from Bechet's New Orleans-influenced playing. It was mainly Bechet's unreliability—he was absent for three days in succession—which made his association with Ellington short-lived.[23]

Cotton Club engagement

In October 1926, Ellington made an agreement with agent-publisher Irving Mills,[24] giving Mills a 45% interest in Ellington's future.[25] Mills had an eye for new talent and published compositions by Hoagy Carmichael, Dorothy Fields, and Harold Arlen early in their careers. After recording a handful of acoustic sides during 1924–26, Ellington's signing with Mills allowed him to record prolifically. However, sometimes he recorded different versions of the same tune. Mills regularly took a co-composer credit. From the beginning of their relationship, Mills arranged recording sessions on nearly every label, including Brunswick, Victor, Columbia, OKeh, Pathé (and its subsidiary, Perfect), the ARC/Plaza group of labels (Oriole, Domino, Jewel, Banner) and their dime-store labels (Cameo, Lincoln, Romeo), Hit of the Week, and Columbia's cheaper labels (Harmony, Diva, Velvet Tone, Clarion), labels that gave Ellington popular recognition. On OKeh, his records were usually issued as The Harlem Footwarmers. In contrast, the Brunswicks were usually issued as The Jungle Band. Whoopee Makers and the Ten BlackBerries were other pseudonyms.

In September 1927, King Oliver turned down a regular booking for his group as the house band at Harlem's Cotton Club;[26] the offer passed to Ellington after Jimmy McHugh suggested him and Mills arranged an audition.[27] Ellington had to increase from a six to 11-piece group to meet the requirements of the Cotton Club's management for the audition,[28] and the engagement finally began on December 4.[29] With a weekly radio broadcast, the Cotton Club's exclusively white and wealthy clientele poured in nightly to see them. At the Cotton Club, Ellington's group performed all the music for the revues, which mixed comedy, dance numbers, vaudeville, burlesque, music, and illicit alcohol. The musical numbers were composed by Jimmy McHugh and the lyrics were written by Dorothy Fields (later Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler), with some Ellington originals mixed in. (Here, he moved in with a dancer, his second wife Mildred Dixon). Weekly radio broadcasts from the club gave Ellington national exposure. At the same time, Ellington also recorded Fields-JMcHugh and Fats Waller–Andy Razaf songs.

Although trumpeter Bubber Miley was a member of the orchestra for only a short period, he had a major influence on Ellington's sound.[30] As an early exponent of growl trumpet, Miley changed the sweet dance band sound of the group to one that was hotter, which contemporaries termed Jungle Style, which can be seen in his feature chorus in East St. Louis Toodle-Oo (1926).[31] In October 1927, Ellington and his Orchestra recorded several compositions with Adelaide Hall. One side in particular, "Creole Love Call", became a worldwide sensation and gave both Ellington and Hall their first hit record.[32][33] Miley had composed most of "Creole Love Call" and "Black and Tan Fantasy". An alcoholic, Miley had to leave the band before they gained wider fame. He died in 1932 at the age of 29, but he was an important influence on Cootie Williams, who replaced him.

In 1929, the Cotton Club Orchestra appeared on stage for several months in Florenz Ziegfeld's Show Girl, along with vaudeville stars Jimmy Durante, Eddie Foy, Jr., Ruby Keeler, and with music and lyrics by George Gershwin and Gus Kahn. Will Vodery, Ziegfeld's musical supervisor, recommended Ellington for the show.[34] According to John Edward Hasse's Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, "Perhaps during the run of Show Girl, Ellington received what he later termed 'valuable lessons in orchestration from Will Vody." In his 1946 biography, Duke Ellington, Barry Ulanov wrote:

From Vodery, as he (Ellington) says himself, he drew his chromatic convictions, his uses of the tones ordinarily extraneous to the diatonic scale, with the consequent alteration of the harmonic character of his music, it's broadening, The deepening of his resources. It has become customary to ascribe the classical influences upon Duke—Delius, Debussy, and Ravel—to direct contact with their music. Actually, his serious appreciation of those and other modern composers, came after he met with Vody.[35]

Ellington's film work began with Black and Tan (1929), a 19-minute all-African-American RKO short[36] in which he played the hero "Duke". He also appeared in the Amos 'n' Andy film Check and Double Check released in 1930, which features the orchestra playing "Old Man Blues" in an extended ballroom scene.[37] That year, Ellington and his Orchestra connected with a whole different audience in a concert with Maurice Chevalier and they also performed at the Roseland Ballroom, "America's foremost ballroom". Australian-born composer Percy Grainger was an early admirer and supporter. He wrote, "The three greatest composers who ever lived are Bach, Delius and Duke Ellington. Unfortunately, Bach is dead, Delius is very ill but we are happy to have with us today The Duke".[38] Ellington's first period at the Cotton Club concluded in 1931.

Early 1930s

Ellington led the orchestra by conducting from the keyboard using piano cues and visual gestures; very rarely did he conduct using a baton. By 1932 his orchestra consisted of six brass instruments, four reeds, and a rhythm section of four players.[39] As the leader, Ellington was not a strict disciplinarian; he maintained control of his orchestra with a combination of charm, humor, flattery, and astute psychology. A complex, private person, he revealed his feelings to only his closest intimates. He effectively used his public persona to deflect attention away from himself.

Ellington signed exclusively to Brunswick in 1932 and stayed with them through to late 1936 (albeit with a short-lived 1933–34 switch to Victor when Irving Mills temporarily moved his acts from Brunswick).

As the Depression worsened, the recording industry was in crisis, dropping over 90% of its artists by 1933.[40] Ivie Anderson was hired as the Ellington Orchestra's featured vocalist in 1931. She is the vocalist on "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)" (1932) among other recordings. Sonny Greer had been providing occasional vocals and continued to do in a cross-talk feature with Anderson. Radio exposure helped maintain Ellington's public profile as his orchestra began to tour. The other 78s of this era include: "Mood Indigo" (1930), "Sophisticated Lady" (1933), "Solitude" (1934), and "In a Sentimental Mood" (1935).

While Ellington's United States audience remained mainly African-American in this period, the orchestra had a significant following overseas. They traveled to England and Scotland in 1933, as well as France (three concerts at the Salle Pleyel in Paris)[41] and the Netherlands before returning to New York.[42][43] On June 12, 1933, the Duke Ellington Orchestra gave its British debut at the London Palladium;[44] Ellington received an ovation when he walked on stage.[45] They were one of 13 acts on the bill and were restricted to eight short numbers; the booking lasted until June 24.[43][46] The British visit saw Ellington win praise from members of the serious music community, including composer Constant Lambert, which gave a boost to Ellington's interest in composing longer works.

His longer pieces had already begun to appear. Ellington had composed and recorded "Creole Rhapsody" as early as 1931 (issued as both sides of a 12" record for Victor and both sides of a 10" record for Brunswick).[47] A tribute to his mother, "Reminiscing in Tempo", took four 10" 78rpm record sides to record in 1935 after her death in that year.[48] Symphony in Black (also 1935), a short film, featured his extended piece 'A Rhapsody of Negro Life'. It introduced Billie Holiday, and won the Academy Award for Best Musical Short Subject.[49] Ellington and his Orchestra also appeared in the features Murder at the Vanities and Belle of the Nineties (both 1934).

For agent Mills, the attention was a publicity triumph, as Ellington was now internationally known. On the band's tour through the segregated South in 1934, they avoided some of the traveling difficulties of African Americans by touring in private railcars. These provided accessible accommodations, dining, and storage for equipment while avoiding the indignities of segregated facilities.

However, the competition intensified as swing bands like Benny Goodman's began to receive widespread attention. Swing dancing became a youth phenomenon, particularly with white college audiences, and danceability drove record sales and bookings. Jukeboxes proliferated nationwide, spreading the gospel of swing. Ellington's band could certainly swing, but their strengths were mood, nuance, and richness of composition, hence his statement "jazz is music, the swing is business".[50]

Later 1930s

From 1936, Ellington began to make recordings with smaller groups (sextets, octets, and nonets) drawn from his then-15-man orchestra.[51] He composed pieces intended to feature a specific instrumentalist, such as "Jeep's Blues" for Johnny Hodges, "Yearning for Love" for Lawrence Brown, "Trumpet in Spades" for Rex Stewart, "Echoes of Harlem" for Cootie Williams and "Clarinet Lament" for Barney Bigard.[52] In 1937, Ellington returned to the Cotton Club, which had relocated to the mid-town Theater District. In the summer of that year, his father died, and due to many expenses, Ellington's finances were tight. However, his situation improved in the following years.

After leaving agent Irving Mills, he signed on with the William Morris Agency. Mills, though, continued to record Ellington. After only a year, his Master and Variety labels (the small groups had recorded for the latter) collapsed in late 1937. Mills placed Ellington back on Brunswick and those small group units on Vocalion through to 1940. Well-known sides continued to be recorded, "Caravan" in 1937, and "I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart" the following year.

Billy Strayhorn, originally hired as a lyricist, began his association with Ellington in 1939.[53] Nicknamed "Sweet Pea" for his mild manner, Strayhorn soon became a vital member of the Ellington organization. Ellington showed great fondness for Strayhorn and never failed to speak glowingly of the man and their collaborative working relationship, "my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine".[54] Strayhorn, with his training in classical music, not only contributed his original lyrics and music but also arranged and polished many of Ellington's works, becoming a second Ellington or "Duke's doppelgänger". It was not uncommon for Strayhorn to fill in for Duke, whether in conducting or rehearsing the band, playing the piano, on stage, and in the recording studio.[55] The decade ended with a very successful European tour in 1939 just as World War II loomed in Europe.

Ellington in the early to mid-1940s

Two musicians who joined Ellington at this time created a sensation in their own right, Jimmy Blanton and Ben Webster. Blanton was effectively hired on the spot in late October 1939, before Ellington was aware of his name, when he dropped in on a gig of Fate Marable in St Louis.[57] The short-lived Blanton transformed the use of double bass in jazz, allowing it to function as a solo/melodic instrument rather than a rhythm instrument alone.[58]Terminal illness forced him to leave by late 1941 after around two years. Ben Webster's principal tenure with Ellington spanned 1939 to 1943. An ambition of his, he told his previous employer, Teddy Wilson, then leading a big band, that Ellington was the only rival he would leave Wilson for.[59] He was the orchestra's first regular tenor saxophonist and increased the size of the sax section to five for the first time.[60][59] Much influenced by Johnny Hodges, he often credited Hodges with showing him "how to play my horn". The two men sat next to each other in the orchestra.[61]

Trumpeter Ray Nance joined, replacing Cootie Williams who had defected to Benny Goodman. Additionally, Nance added violin to the instrumental colors Ellington had at his disposal. Recordings exist of Nance's first concert date on November 7, 1940, at Fargo, North Dakota. Privately made by Jack Towers and Dick Burris, these recordings were first legitimately issued in 1978 as Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live; they are among the earliest of innumerable live performances which survive. Nance was an occasional vocalist as well, although Herb Jeffries was the main male vocalist in this era (until 1943) while Al Hibbler (who replaced Jeffries in 1943) continued until 1951. Ivie Anderson left in 1942 for health reasons after 11 years, the longest term of any of Ellington's vocalists.[62]

Once more recording for Victor (from 1940), with the small groups being issued on their Bluebird label, three-minute masterpieces on 78 rpm record sides continued to flow from Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Ellington's son Mercer Ellington, and members of the orchestra.[63] "Cotton Tail", "Main Stem", "Harlem Air Shaft", "Jack the Bear", and dozens of others date from this period. Strayhorn's "Take the "A" Train", a hit in 1941, became the band's theme, replacing "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo". Ellington and his associates wrote for an orchestra of distinctive voices displaying tremendous creativity.[64] The commercial recordings from this era were re-issued in the three-CD collection, Never No Lament, in 2003.

Ellington's long-term aim, though, was to extend the jazz form from that three-minute limit, of which he was an acknowledged master.[65] While he had composed and recorded some extended pieces before, such works now became a regular feature of Ellington's output. In this, he was helped by Strayhorn, who had enjoyed a more thorough training in the forms associated with classical music than Ellington. The first of these, Black, Brown, and Beige (1943), was dedicated to telling the story of African Americans and the place of slavery and the church in their history.[66] Black, Brown and Beige debuted at Carnegie Hall on January 23, 1943, beginning an annual series of Ellington concerts at the venue over the next four years. While some jazz musicians had played at Carnegie Hall before, none had performed anything as elaborate as Ellington's work. Unfortunately, starting a regular pattern, Ellington's longer works were generally not well received.

A partial exception was Jump for Joy, a full-length musical based on themes of African-American identity, which debuted on July 10, 1941, at the Mayan Theater in Los Angeles. Hollywood actors John Garfield and Mickey Rooney invested in the production, and Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles offered to direct.[67] At one performance, Garfield insisted that Herb Jeffries, who was light-skinned, should wear makeup. Ellington objected in the interval and compared Jeffries to Al Jolson. The change was reverted. The singer later commented that the audience must have thought he was an entirely different character in the second half of the show.[68]

Although it had sold-out performances and received positive reviews,[69] it ran for only 122 performances until September 29, 1941, with a brief revival in November of that year. Its subject matter did not make it appealing to Broadway; Ellington had unfulfilled plans to take it there.[70] Despite this disappointment, a Broadway production of Ellington's Beggar's Holiday, his sole book musical, premiered on December 23, 1946,[71] under the direction of Nicholas Ray.

The settlement of the first recording ban of 1942–44, leading to an increase in royalties paid to musicians, had a severe effect on the financial viability of the big bands, including Ellington's Orchestra. His income as a songwriter ultimately subsidized it. Although he always spent lavishly and drew a respectable income from the orchestra's operations, the band's income often just covered expenses.[72] However, in 1943 Ellington asked Webster to leave; the saxophonist's personality made his colleagues anxious and the saxophonist was regularly in conflict with the leader.[73]

Early post-war years

Musicians enlisting in the military and travel restrictions made touring difficult for the big bands, and dancing became subject to a new tax, which continued for many years, affecting the choices of club owners. By the time World War II ended, the focus of popular music was shifting towards singing crooners such as Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford. As the cost of hiring big bands had increased, club owners now found smaller jazz groups more cost-effective. Some of Ellington's new works, such as the wordless vocal feature "Transblucency" (1946) with Kay Davis, were not going to have a similar reach as the newly emerging stars.

Ellington continued on his own course through these tectonic shifts. While Count Basie was forced to disband his whole ensemble and work as an octet for a time, Ellington was able to tour most of Western Europe between April 6 and June 30, 1950, with the orchestra playing 74 dates over 77 days.[74] During the tour, according to Sonny Greer, Ellington did not perform the newer works. However, Ellington's extended composition, Harlem (1950), was in the process of being completed at this time. Ellington later presented its score to music-loving President Harry Truman. Also during his time in Europe, Ellington would compose the music for a stage production by Orson Welles. Titled Time Runs in Paris[75] and An Evening With Orson Welles in Frankfurt, the variety show also featured a newly discovered Eartha Kitt, who performed Ellington's original song "Hungry Little Trouble" as Helen of Troy.[76]

In 1951, Ellington suffered a significant loss of personnel: Sonny Greer, Lawrence Brown, and, most importantly, Johnny Hodges left to pursue other ventures. However, only Greer was a permanent departee. Drummer Louie Bellson replaced Greer, and his "Skin Deep" was a hit for Ellington. Tenor player Paul Gonsalves had joined in December 1950[74] after periods with Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie and stayed for the rest of his life, while Clark Terry joined in November 1951.[77]

André Previn said in 1952: "You know, Stan Kenton can stand in front of a thousand fiddles and a thousand brass and make a dramatic gesture and every studio arranger can nod his head and say, Oh, yes, that's done like this. But Duke merely lifts his finger, three horns make a sound, and I don't know what it is!"[78] However, by 1955, after three years of recording for Capitol, Ellington lacked a regular recording affiliation.

Career revival

Ellington's appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival on July 7, 1956, returned him to wider prominence. The feature "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue" comprised two tunes that had been in the band's book since 1937. Ellington, who had abruptly ended the band's scheduled set because of the late arrival of four key players, called the two tunes as the time was approaching midnight. Announcing that the two pieces would be separated by an interlude played by tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves, Ellington proceeded to lead the band through the two pieces, with Gonsalves' 27-chorus marathon solo whipping the crowd into a frenzy, leading the Maestro to play way beyond the curfew time despite urgent pleas from festival organizer George Wein to bring the program to an end.

The concert made international headlines, and led to one of only five Time magazine cover stories dedicated to a jazz musician,[79] and resulted in an album produced by George Avakian that would become the best-selling LP of Ellington's career.[80] Much of the music on the LP was, in effect, simulated, with only about 40% actually from the concert itself. According to Avakian, Ellington was dissatisfied with aspects of the performance and felt the musicians had been under-rehearsed.[80] The band assembled the next day to re-record several numbers with the addition of the faked sound of a crowd, none of which was disclosed to purchasers of the album. Not until 1999 was the concert recording properly released for the first time. The revived attention brought about by the Newport appearance should not have surprised anyone, Johnny Hodges had returned the previous year,[81] and Ellington's collaboration with Strayhorn was renewed around the same time, under terms more amenable to the younger man.[82]

The original Ellington at Newport album was the first release in a new recording contract with Columbia Records which yielded several years of recording stability, mainly under producer Irving Townsend, who coaxed both commercial and artistic productions from Ellington.[83]

In 1957, CBS (Columbia Records' parent corporation) aired a live television production of A Drum Is a Woman, an allegorical suite which received mixed reviews. Festival appearances at the new Monterey Jazz Festival and elsewhere provided venues for live exposure, and a European tour in 1958 was well received. Such Sweet Thunder (1957), based on Shakespeare's plays and characters, and The Queen's Suite (1958), dedicated to Britain's Queen Elizabeth II, were products of the renewed impetus which the Newport appearance helped to create. However, the latter work was not commercially issued at the time. The late 1950s also saw Ella Fitzgerald record her Duke Ellington Songbook (Verve) with Ellington and his orchestra—a recognition that Ellington's songs had now become part of the cultural canon known as the 'Great American Songbook'.

Around this time Ellington and Strayhorn began to work on film scoring. The first of these was Anatomy of a Murder (1959),[39] a courtroom drama directed by Otto Preminger and featuring James Stewart, in which Ellington appeared fronting a roadhouse combo. Film historians have recognized the score "as a landmark—the first significant Hollywood film music by African Americans comprising non-diegetic music, that is, music whose source is not visible or implied by action in the film, like an on-screen band." The score avoided the cultural stereotypes which previously characterized jazz scores and rejected a strict adherence to visuals in ways that presaged the New Wave cinema of the '60s".[84] Ellington and Strayhorn, always looking for new musical territory, produced suites for John Steinbeck's novel Sweet Thursday, Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker Suite and Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt.

Anatomy of a Murder was followed by Paris Blues (1961), which featured Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier as jazz musicians. For this work, Ellington was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Score.

In the early 1960s, Ellington embraced recording with artists who had been friendly rivals in the past or were younger musicians who focused on later styles. The Ellington and Count Basie orchestras recorded together with the album First Time! The Count Meets the Duke (1961). During a period when Ellington was between recording contracts, he made records with Louis Armstrong (Roulette), Coleman Hawkins, John Coltrane (both for Impulse) and participated in a session with Charles Mingus and Max Roach which produced the Money Jungle (United Artists) album. He signed to Frank Sinatra's new Reprise label, but the association with the label was short-lived.

Musicians who had previously worked with Ellington returned to the Orchestra as members: Lawrence Brown in 1960 and Cootie Williams in 1962.

The writing and playing of music is a matter of intent... You can't just throw a paintbrush against the wall and call whatever happens art. My music fits the tonal personality of the player. I think too strongly in terms of altering my music to fit the performer to be impressed by accidental music. You can't take doodling seriously.[16]

He was now performing worldwide and spent a significant part of each year on overseas tours. As a consequence, he formed new working relationships with artists from around the world, including the Swedish vocalist Alice Babs, and the South African musicians Dollar Brand and Sathima Bea Benjamin (A Morning in Paris, 1963/1997).

Ellington wrote an original score for director Michael Langham's production of Shakespeare's Timon of Athens at the Stratford Festival in Ontario, Canada, which opened on July 29, 1963. Langham has used it for several subsequent productions, including a much later adaptation by Stanley Silverman which expands the score with some of Ellington's best-known works.

Last years

Ellington was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1965. However, no prize was ultimately awarded that year.[85] Then 66 years old, he joked: "Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn't want me to be famous too young."[86] In 1999, he was posthumously awarded a special Pulitzer Prize "commemorating the centennial year of his birth, in recognition of his musical genius, which evoked aesthetically the principles of democracy through the medium of jazz and thus made an indelible contribution to art and culture."[6][87]

In September 1965, he premiered the first of his Sacred Concerts. He created a jazz Christian liturgy. Although the work received mixed reviews, Ellington was proud of the composition and performed it dozens of times. This concert was followed by two others of the same type in 1968 and 1973, known as the Second and Third Sacred Concerts. Many saw the Sacred Music suites as an attempt to reinforce commercial support for organized religion. However, Ellington simply said it was "the most important thing I've done".[88] The Steinway piano upon which the Sacred Concerts were composed is part of the collection of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. Like Haydn and Mozart, Ellington conducted his orchestra from the piano—he always played the keyboard parts when the Sacred Concerts were performed.[89]

Duke turned 65 in the spring of 1964 but showed no signs of slowing down as he continued to make recordings of significant works such as The Far East Suite (1966), New Orleans Suite (1970), The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse (1971) and the Latin American Suite (1972), much of it inspired by his world tours. It was during this time that he recorded his only album with Frank Sinatra, titled Francis A. & Edward K. (1967).