SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FOUR

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FOUR

BILLIE HOLIDAY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ERIC DOLPHY

July 18-24

MARVIN GAYE

July 25-31

ABBEY LINCOLN

August 1-7

RAY CHARLES

August 8-14

SADE

August 15-21

BETTY CARTER

August 22-28

CHARLIE PARKER

August 29-September 4

MICHAEL JACKSON

September 5-11

CHAKA KHAN

September 12-18

JOHN COLTRANE

September 19-25

SARAH VAUGHAN

September 26-October 2

THELONIOUS MONK

October 3-9

July 18-24

MARVIN GAYE

July 25-31

ABBEY LINCOLN

August 1-7

RAY CHARLES

August 8-14

SADE

August 15-21

BETTY CARTER

August 22-28

CHARLIE PARKER

August 29-September 4

MICHAEL JACKSON

September 5-11

CHAKA KHAN

September 12-18

JOHN COLTRANE

September 19-25

SARAH VAUGHAN

September 26-October 2

THELONIOUS MONK

October 3-9

http://www.furious.com/perfect/ericdolphy.html

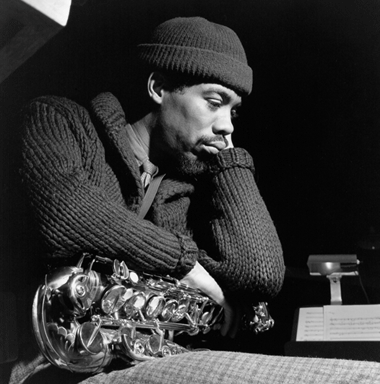

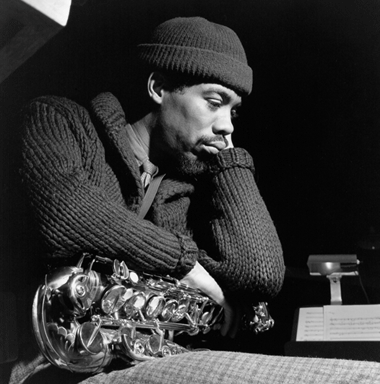

Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group

"Lloyd Reese was a master musician," Mingus said. "He knew jazz and all the fundamentals of music from the beginning. He used to be the first alto player in Les Height's band. And he could play anything."

Shy and introspective as a teenager, Eric spent nearly every waking hour cloistered away in his backyard studio, practicing and studying music. Dolphy fed his voracious musical appetite with everything from field recordings of pygmy yodeling to modern composers like Schoenberg.

Viewing a rare videotape of an interview with Eric Dolphy's parents conducted years ago by Alan Saul, a college student at the time, supplied enormous insight into the multi-instrumentalist's personality and supplied this article with many of the quotes from his folks. There were long awkward silent pauses as Alan, a self-conscious, well-intentioned young hippie, held a legal pad, as he nervously looked over a long list of questions while Dolphy's parents sat on the sofa graciously obliging. Eric Sr. was reserved and thoughtful. He let his wife and his polka dot shirt do most of the talking.

Dolphy's mother Sadie recalled how he got up each morning by five to practice until breakfast and then left for school. After classes, he'd hurry back home again to work on his tone.

"He'd blow one note all day long!" Sadie exclaimed.

"For weeks at a time!" Eric Sr. added. "Then he'd play it and put it on his tape recorder and listen to it. He'd say, "Dad it's got to be right."

I'd say, "It sounds right to me."

But Eric, perfectionist that he was, replied, "No. It's not right yet."

"Sometimes we'd be sleeping and hear him plunking on the piano," Eric Sr. continued. "And I'd say, ‘Hey, what ya doin'?' He'd say, ‘I just got an idea.' And he'd be writing y'know."

"He was gonna be a musician. He wasn't gonna do anything else!" Sadie said.

"He became discouraged when he couldn't get any work. But he kept on working at it because he figured some day, somehow he'd make it."

Like every saxophonist of his generation Eric was heavily inspired by Charlie Parker. Dolphy spent years mastering Bird's technique and concepts, employing them as the foundation for his own imaginative improvisations. Lillian Polen, a close friend of Eric's at this time recalled that Dolphy wholeheartedly "worshipped Bird." She recalled regularly "falling by the Oasis," a small club on Central Avenue in LA to check out Dolphy's band. At the time, Eric worried that people would write him as just another Charlie Parker imitator.

Years later, Eric explained his inspiration for his album title Far Cry: "The title's meaning is that it's a far cry from the impact Bird had when he was alive and his position now. I wrote this to show that I haven't forgotten him or what he's meant to me. But the song also says that as great as he was, he was a far cry from what he could have been. And, finally, it says that I'm a far cry from being able to say all I want in jazz."

Eric came to prominence during a transitional period in jazz. In the evolution of the alto saxophone, his horn bridged the gap between Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman and helped usher be bop into the uncharted realm of the avant-garde or the "New Thing." His unique sense of harmony and jagged melody lines had more in common with the fractured piano of Thelonious Monk than any horn player of his time. His lyrical leaps from one register to the next spanned a broad range of emotion and expression that few musicians then or now have been capable of. Dolphy's vocabulary ranged from a gentle whisper to a full-blown anxiety attack. Like Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, Eric also battled the grim existential atmosphere of cold war era with an irrepressible howl.

"To me, jazz is like part of living, like walking down the street and reacting to what you see and hear. And whatever I react to, I can say immediately in my music," he once said.

"It was evident he had his Charlie Parker together, but little did I realize that he would become one of the groundbreakers of the new music of the Sixties," critic Ira Gitler exclaimed after witnessing Dolphy with Chico Hamilton's Quintet at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958.

At the time, Hamilton's group typified West Coast cool. Their soft tasteful chamber jazz, comprised of guitar, cello and woodwinds, was a forerunner to future New Age bands like the Paul Winter Consort and Oregon. In this setting, Dolphy's fiery approach to improvisation was rather risky. At any moment, Eric could suddenly bust Chico's groovy mood wide open with just a few slurs and squawks from his bass clarinet. Critics that just didn't get it heard Eric's joyous squeals as amateurish, shrill and offensive.

Earlier that year Buddy Collette left Chico Hamilton's Quintet, suggesting Eric Dolphy as his replacement. Eric played in the group a short time before re-locating to New York in the autumn of 1959 when he joined forces with his old friend from L.A., the volatile bassist Charles Mingus.

Back in California, Dolphy had been harshly criticized for playing out of tune.

"The public in general wasn't ready for Eric when he was in my band," Hamilton later admitted. Many complained, suggesting that Chico fire him and find someone more suitable to his smooth sound. "But Eric was such an original type player. He had a legitimate background in music to the extent of the classics and he studied with [William] Kincaid. He did everything correct. He was total music," Hamilton said in his former sideman's defense.

Chico believed it a coincidence that Dolphy became a jazz musician in the first place. He felt Eric's exceptional technique and diversity would have allowed him to pursue any style of music he desired, from classical to R&B.

Dolphy employed traditional song structures as his foundation for expression and exploration while Ornette's approach came straight out of Planet X. The kind of freedom practiced and encouraged by members of Coleman's quartet shook the very foundations of jazz at its core. Unless the listener was willing to approach the complexity of Ornette's music with an unbiased mind and open ears, allowing the sound to wash over them without analysis, they would never grasp its full impact.

Coleman's image as the era's premiere iconoclast may have overshadowed many of his peers but Dolphy's role in the avant-garde was unquestionably integral to its development. One listen to his contribution to such milestone recordings as Coleman's Free Jazz and Oliver Nelson's Blues and the Abstract Truth and John Coltrane's Live at the Village Vanguard will immediately set the record straight.

For whatever reason, many of Eric's best solos were recorded as a sideman. Free from the pressures of leading his own band, Dolphy may have been able to express himself on a deeper level, embellishing his cohort's compositions with his lyrical and explosive reed work. Or perhaps it was the camaraderie that inspired to reach a little deeper. Yet Dolphy's music stands alone as an entirely valid expression unto itself, with or without his association to Mingus, Coltrane and Coleman.

"He had such a big sound, as big as Charlie Parker's," Mingus claimed. "Inside that sound was great capacity to talk in his music about the most basic feelings. He knew that level of language which very few musicians get down to."

"Near the end of ‘What Love' Mingus and Dolphy (on bass clarinet) have a long and different kind of conversation on their instruments, apparently about Dolphy's intention of quitting the band," Whitney Balliett revealed in Night Creatures. "Eric Dolphy and I were having a conversation about his leaving the band. Mainly it was curse words, except for Eric. Eric didn't curse until the very end of his solo," Mingus joked. "He was absolutely without a need to hurt," Charles explained. The duets at the Five Spot with Mingus playing bass and Dolphy on bass clarinet are among the greatest musical dialogues in the history of the music. "We used to talk to each other, and you could understand – and I mean understand in words – what he was saying to me," Mingus said.

Friction continued to develop between the two and by the end of the 1964 tour Dolphy had grown weary of Mingus' outrageous antics. True to form, Charles lived up to his myth as the mad, sexy genius he was, busting microphones, telephones and doors. He was also arrested for wielding a knife.

"Eric played with Mingus after I did," Composer/multi-instrumentalist David Amram told me in a recent interview. "I played French horn with Mingus in '55. Mingus loved Eric's bass clarinet. Both instruments were unusual in a jazz setting. Mingus could hear these instruments in a different way and adjust his music to what they could do. I was particularly interested in Eric's bass clarinet as I had a part for one in my opera, Twelfth Night. I told him, ‘Some of the registers you're playing on the bass clarinet, I wouldn't dare write because nobody could stay in tune or make it sound good, playing that high.' He said, ‘They should either check me out or practice,' David laughed. "He believed there were no limitations in music, that if you wanted to do it enough, you would find a way. He had a great sense of adventure and daring. He was a true improviser. Remember he had a real foundation in music. There are a lot of free jazz players these days that don't have that kind of background. He could play within the mainstream but he just followed how he felt."

Seldom does a musician's search for a new mode of expression culminate in a riotous response from their audience. The most notorious instance in the twentieth century was Igor Stravinsky's premiere of "Sacre du Printemps" in 1913. A little over fifty years later, Bob Dylan suddenly shed his Woody Guthrie/weary dust bowl bumpkin balladeer guise, put on his black leather jacket and plugged in his Stratocaster at the Newport Folk Festival. The crowd erupted in outrage and anger. In the heat of the moment, the banjo-strumming King of Sing-Along, Pete Seeger was said to have grabbed an ax with the intent of whittling the soundboard into kindling but was thankfully subdued. The folkies felt betrayed by their boy wonder. Before them stood Bob Dylan, like Judas in Beatle boots, defiantly flailing his Fender while crowing, "I ain't gonna work on Maggie's Farm No More!" His message came across loud and clear. He had turned his back on "the cause." Dylan may have sold out to rock and roll as many claimed, but he also happened to be playing some of the best damn music of his career.

With the release of My Favorite Things in the spring of 1961, John Coltrane experienced a wave of popularity unlike anything he'd ever known. With his soaring soprano saxophone, Coltrane transformed Julie Andrews' little ditty from the popular Disney film The Sound of Music into a lilting waltz that was at once romantic, accessible and cool. In the process, Coltrane had unwittingly hipped an entire generation of tweed-clad, flat-topped college kids to jazz. Even girls liked it!

Suddenly reporters from Newsweek scurried down the narrow, red-carpeted stairs of the Village Vanguard to cover the story. But it wasn't long before Rogers and Hammerstein's lovely tune became a vehicle for some of Coltrane's most torrid improvisations.

In no time, the critics attacked Coltrane like a pack of rabid hounds, tearing him apart for blowing half hour solos over a repetitive two-chord vamp. Leonard Feather believed this latest development in John's music was "retrogressive in terms of development in jazz." Feather also complained that Coltrane's endless soloing was monotonous when compared to the lush harmonic complexity of an Ellington arrangement.

"You see, that is another complexity in itself, of playing on 1 or 2 changes." Dolphy countered. Eric actually found it more challenging for a creative musician to play over a sparse framework. The simple repetition laid bare the musician's technique and intent for all to hear. With no place to hide, their shortcomings were certain to become obvious after just a few choruses.

"This automatically gives him more time to think, and it gives him the chance to unfold a lot more. Like in Indian music they only have one [chord], in our Western music we can usually hear one minor chord, but they call it a raga or scale and they'll play for twenty minutes."

Eric understood the rigorous path of discipline and practice that Indian classical musicians must endure to perfect their technique and build a musical vocabulary diverse enough to successfully improvise over a single chord without becoming redundant.

"Music contains like, rhythm and pitch, time, space and all these elements go into improvisation," Dolphy once said. "You have to take that into consideration. It's not a question of running notes, running notes in random."

Eric was deeply inspired by the hypnotic beauty of Indian music, not as a superficial trend but as a form of discipline and expression similar to his own. Years before Beatle George Harrison and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones employed the sitar's exotic twang as a condiment to their catchy pop tunes, Coltrane and Dolphy could be heard improvising within the framework of these scales on John's haunting composition "India."

As fate would have it Eric met the spectacular sitarist Ravi Shankar on his first tour of the U.S. It was a great opportunity for the multi-instrumentalist to learn about ragas, talas and other intricacies of Indian music directly the master of the form.

As Dolphy later explained it: "Classical Indian music is the music of [Indian] people and jazz is the music of the American people, especially the American Negro. Quite naturally, there's something of a connection there, of people expressing themselves in the same way [ancient blues of variable hues]. To the listener that doesn't pay close attention to the notes, the sound will get monotonous. But to the person that listens to the actual notes and the creation that's going on and the building within the players and within themselves, they'll notice that something is actually happening."

In November 1961, Trane toured England bringing Eric Dolphy along to augment his classic quartet. Jazz writer/photographer Val Wilmer believed their performance had "an enormous impact, particularly on local musicians."

Regarding the classic quartet, pianist McCoy Tyner once remarked, "That group was like four pistons in an engine. We were all working together to make the car go." If that was indeed the case, many critics and fans alike looked at the addition of Eric Dolphy as an extraneous fifth wheel.

The reaction in the press to Dolphy joining the group was second only to the Spanish Inquisition. On November 23, Down Beat published a scathing review by John Tynan, who claimed that "melodically and harmonically" the group's collective improvisations sounded like "gobbledygook."

Suddenly John and Eric were perceived as a pair of charlatans, plotting "an anarchistic course," and playing a defiant brand of "anti-jazz" that didn't swing. Both Coltrane and Dolphy were stumped by Tynan's term. Eric found the accusation confusing and absurd. "In fact, it swings so much I don't know what to do – it moves me so much," he replied. "I'd like to know how they explain ‘anti-jazz'. Maybe they can tell us something."

"There are various types of swing," Coltrane theorized. "There's 4/4, with heavy bass drum accents. Then there's the kind of thing that goes on in Count Basie's band. In fact, every group of individuals assembled has a different feeling, a different swing. It's a different feeling than in any other band," John said, regarding his quintet. "It's hard to answer a man who says it doesn't swing."

"It's kind of alarming to the musician when someone has written something bad about what the musician plays but never asks the musician anything about it. At least the musician feels bad. But he doesn't feel so bad that he quits playing," Eric countered. "The critic influences a lot of people. If something new has happened, something nobody knows what the musician's doing, he should ask the musician about it. Because somebody may like it; they might want to know something about it. Sometimes it really hurts, because a musician not only loves his work but depends on it for his living. If somebody writes something bad about musicians, people stay away. Not because the guys don't sound good but because somebody said something that has influence over a lot of people."

Photo courtesy of All About Jazz

God Bless The Child, Part II

An advocate of free jazz, Dolphy was a champion of free speech as well. Ultimately Eric believed that Tynan was entitled to voice his opinion, but he questioned the motivation behind the critic's terse words. Gentle as he was, Eric would not stand by idly while somebody made ignorant comments that were damaging to both his and Coltrane's career.

"You use other notes in the chord to give you certain expressions to the song, otherwise you'd be playing what everybody else is playin'. The thing only happens at the moment when you do it, and quite naturally it might change," Eric said, hoping to shed some light on the elusive process of improvisation.

When Eric Dolphy moved to Manhattan in 1960, he first joined the Mingus Workshop, then later that same year he began playing with Ornette Coleman.

In retrospect, it's surprising that Coleman's music caused such a maelstrom. Many of his compositions have an almost child-like, singsong quality while others reveal a West-Indian calypso feel. His drummers, Eddie Blackwell and Billy Higgins always swung hard. In his unorthodox approach to group soloing, which had its roots in traditional New Orleans music, Ornette would forge a fresh, new, dimension of sound. No matter how radical his concept of Harmolodics, Coleman never completely abandoned changes that chords (if they had been employed) inferred.

"You CAN play every note you like," Dolphy told Leonard Feather, in a desperate attempt to convey the essence of the new music. "Of course, you can only play what you can hear, and quite naturally... more or less I guess what I hear is not your hearing."

In the spring of 1964, Dolphy left Mingus' band while on a tour of Europe and planned to live in Paris where quite a number of expatriate musicians found themselves welcome with open arms. But that June, Dolphy suddenly died due to complications from diabetes. Two months earlier Mingus had composed and recorded a blues entitled "So Long Eric" which he maintained was not a "eulogy" but a "complaint."

At the end of Alan Saul's video, he sits on Dolphy's sofa asking if they ever feel bitter about the way things all went down.

It will be difficult to avoid clichés here. In their defense, clichés originate from an authentic place; they are mostly an attempt, at least initially, to articulate something honest and immutable. And so: Eric Dolphy is among the foremost supernovas in all of jazz (Clifford Brown, Booker Little and Lee Morgan—all trumpeters incidentally—also come quickly to mind): he burned very brightly and very briefly, and then he was gone. Speaking of clichés, not a single one of the artists just mentioned—all of whom left us well before their fortieth birthdays—died from a drug overdose. Dolphy, the grand old man of the bunch, passed away at the age of 36, in Europe. How? After lapsing into a diabetic coma. Why? The doctors on duty presumed the black musician who had collapsed in the street was nodding off on a heroin buzz. To attempt to put the magnitude of this loss in perspective, consider that Charles Mingus, perhaps the most difficult and demanding band leader of them all, declared Dolphy a saint, and regarded his death as one of a handful of setbacks he could never completely get over. Dolphy holds the distinction of quite possibly being the one artist nobody has gone on record to say a single negative thing about. His body of work, the bulk of which was recorded during an almost miraculously productive five-year stretch, is deep, challenging, and utterly enjoyable. Outward Bound, then, holds a special place as his debut recording as a leader.

Music

Jazz Enigma of the ’60s Has an Encore

A New Focus on Eric Dolphy, in Washington and Montclair

MAY 27, 2014

New York Times

Jazz Festival to Honor Eric Dolphy

Question: What’s it all about?

Answer: I don’t know.

But I do know a few things.

I know some of the things that make me tick.

Even though I write (for fun, for real and forever), I would still say that music has always been the central element of my existence. Or the elemental center. Writing is a compulsion, a hobby, a skill, a craft, an obsession, a mystery and at times a burden. Music simply is. For just about anyone, all you need is an ear (or two); that is all that’s required for it to work its magic. But, as many people come to realize, if you approach it with your mind, and your heart and, eventually (inevitably) your soul, it is capable of making you aware of other worlds, it can help you achieve the satisfaction material possessions are intended to inspire, it will help you feel the feelings drugs are designed to approximate. Et cetera.

I know that jazz music has made my life approximately a million times more satisfying and enriching than it would have been had I never been fortunate enough to discover, study and savor it.

During the last 4-5 years, I’ve had (or taken) the opportunity to write in some detail about Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Freddie Hubbard, Ornette Coleman, John Zorn, and Herbie Hancock. This has been important to me, because I feel that in some small way, if I can help other people better appreciate, or discover any (or all) of these artists, I will be sharing something bigger and better than anything I alone am capable of creating.

Before this blog (and PopMatters, where virtually all of my music writing appears), and during the decade or so that stretched from my mid-’20s to mid-’30s, I used to have more of an evangelical vibe. It’s not necessarily that I’m less invested, now, then I was then; quite the contrary. But, if I wasn’t particuarly interested in converting people then (I wasn’t), I’m even less so today. When it comes to art in general and music in particular, entirely too many people are very American in their tastes: they know what they like and they like what they know. And there’s nothing wrong with that, since what they don’t know won’t hurt them. Also, let’s face it, the only thing possibly more annoying than some yahoo proselytizing their religion on your doorstep is some jackass getting in your grill about how evolved or enviable his or her musical tastes happen to be. Life is way too short, for all involved.

On the other hand, back in the day I was obliged to talk about music using only words. Now there is YouTube. You can’t believe everything you read, but you can always have faith in what you hear; the ears never lie. Not when it comes to music. Not when it comes to jazz music.

How to talk about jazz music? Well, perhaps it’s better to determine how not to talk about jazz music. Hearing is believing. That’s it. And if you hear something that speaks to you, keep listening. Whatever effort you put in will be immeasurably rewarded. Trust me. But first, eradicate cliché. Possibly the most despicable myth (that, fortunately doesn’t seem as widespread, perhaps –sigh– because less people talk or care about jazz music in 2010) is one I found myself ceaselessly rebutting back in the bad old days. You know which one: that lazy, anecdotally innacurate and often racist assumption that all jazz artists are (or at least were) heroin addicts. That’s like saying all pro athletes are steroid abusers. Oh wait…

There are several dozen top-tier jazz musicians whose artistic (and personal) lives could be held up as examples any sane person should want to emulate. And while geniuses like Wayne Shorter, Jackie McLean, McCoy Tyner, Max Roach, Henry Threadgill and Sonny Rollins all spring immediately to mind, the one I believe serves as the ultimate example of everything sublime about jazz music is Eric Dolphy. I’ve discussed –and celebrated– the man at length here, as well as here, here and here.

This is an excerpt from my review of Dolphy’s Outward Bound:

It will be difficult to avoid clichés here. In their defense, clichés originate from an authentic place; they are mostly an attempt, at least initially, to articulate something honest and immutable. And so: Eric Dolphy is among the foremost supernovas in all of jazz (Clifford Brown, Booker Little and Lee Morgan—all trumpeters incidentally—also come quickly to mind): he burned very brightly and very briefly, and then he was gone. Speaking of clichés, not a single one of the artists just mentioned—all of whom left us well before their fortieth birthdays—died from a drug overdose. Dolphy, the grand old man of the bunch, passed away at the age of 36, in Europe. How? After lapsing into a diabetic coma. Why? The doctors on duty presumed the black musician who had collapsed in the street was nodding off on a heroin buzz. To attempt to put the magnitude of this loss in perspective, consider that Charles Mingus, perhaps the most difficult and demanding band leader of them all, declared Dolphy a saint, and regarded his death as one of a handful of setbacks he could never completely get over. Dolphy holds the distinction of quite possibly being the one artist nobody has gone on record to say a single negative thing about. His body of work, the bulk of which was recorded during an almost miraculously productive five-year stretch, is deep, challenging, and utterly enjoyable.

One of the paradoxical reasons Dolphy tends to get overlooked, even slighted, is not because of any lack of proficiency, but rather an abundance of it. It does not quite seem possible—particularly for lazier critics and ringleaders amongst the jazz intelligentsia—that such a relatively young musician could master three instruments. In actuality, Dolphy was an exceedingly accomplished alto sax player, drawing freely (pun intended) from Bird while pointing the way toward Braxton. Perhaps most egregiously disregarded is his flute playing, which not only achieves a consistent and uncommon beauty, but more than holds its own against fellow multi-reedists Yusef Lateef and Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Nevertheless, it is the signature, unmistakable sounds he makes with the bass clarinet that ensure his place in the pantheon: no one of note, excepting Harry Carney, employed this instrument on the front line before Dolphy and, arguably, no one has used it as effectively and indelibly since…Let there be no doubt that Eric Dolphy warrants mention amongst jazz music’s all-time immortals.

So: a sample of some of Dolphy’s finer moments

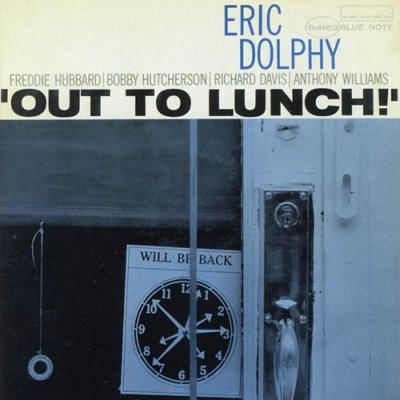

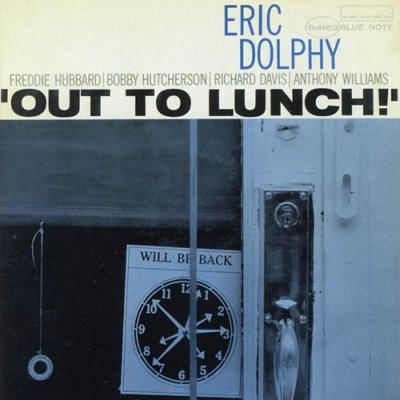

1. “Hat And Beard” from Out To Lunch.

This song, the first track from his last proper album, can serve as well as virtually any other composition I can think of to best illustrate what jazz is; what it is capable of conveying. In this song, the primary feeling is ecstasy. The ecstasy of discovery; the ecstasy of shared purpose amongst the musicians (and this is an unbelievable group of masters, including Freddie Hubbard, Tony Williams and Bobby Hutcherson) and the ecstasy of expression. This song’s title is a tribute to Thelonious Monk, but the notes are all Dolphy. Here is his slightly surreal, intentionally off-kilter, totally focused and deeply, darkly beautiful vision fully developed and delivered. This is not the easiest music to absorb, at least initially, but once you “get it”, you stay got.

2. “Come Sunday” from Iron Man.

That Dolphy is able to cover the immortal Duke Ellington so convincingly is remarkable; that he is able to do it so indelibly with only one other musician (Richard Davis) is more than a little miraculous. The sheer volume of feeling in this performance is mind boggling, and life changing. Dolphy’s bass clarinet sings, cries and cajoles. It whispers and it pleads, and then it sighs. By the end, it has exhausted itself; it has said everything there is to say.

3. “Eclipse” from Out There.

Another tribute to another great composer: his friend, mentor and bandmate Charles Mingus. Writing recently about Jimi Hendrix, I observed that “The Wind Cries Mary” captures the feeling of melancholy as well as any song ever has. And it does. But to do similar work without words, as Dolphy does here, is a truly staggering achievement. The mournful cadence of Dolphy’s clarinet here gets right inside you, and the feeling expressed is magnified by Ron Carter’s bowed cello, which weaves in and around, at once among the corners and right within the heart of the song. The sounds these two men achieve are so unusual, so unsettling and (the word has to be used again) so surreal, it almost defies explanation. This is music best categorized as other and the album title, Out There, is more than a little appropriate. Dolphy was indeed “out there” in the sense that most of us are blissful or oblivious inside our little boxes, incapable of hearing, much less expressing, the joyful noises that reside in those most inaccessible spaces: within each of us.

4. “Left Alone” from Far Cry.

So, you might ask, are you really telling me I should want to listen to music that is capable of making me cry?

Yes, I would reply.

And, you might add, why would I want to do such a thing?

It’s simple, I’d say. So that you know you are alive.

5. “Miss Ann” from Last Date.

Eric Dolphy, dead at 36. There is nothing anyone can say that could possibly begin to explain or rationalize that travesty of justice; that affront to life. It is the intolerable enigmas like these that make certain people hope against hope that there is a bigger purpose and plan, a way to measure or quantify this madness. But in the final, human analysis, whatever we lost can never overwhelm all that we received. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: It helps that we will always have the gifts the artist left behind. It’s never enough; it’s more than enough.

After the final cut of his final recording, Dolphy offers the following observation: “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone in the air…you can never capture it again.”

What he said.

"Whatever I'd say would be an understatement. I can only say my life was made much better by knowing him. He was one of the greatest people I've ever known, as a man, a friend, and a musician." – John Coltrane on Eric Dolphy

“When you hear music, after it's over, it's gone, in the air. You can never capture it again.” – Eric Dolphy

"I'm leaving to live in Europe. Why? Because if you try to do something new and different in this country (the U.S.) people put you down for it."

THE MUSIC OF ERIC DOLPHY: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH MR. DOLPHY:

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/eric-dolphy-the-complete-prestige-recordings-by-mike-neely.php

Eric Dolphy Turns Eighty

Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group

God Bless The Child

By John Kruth

(August 2008)

Eric Allan Dolphy was born eighty years ago on June 20th 1928. An

only child, of parents of West-Indian heritage, Eric grew up in L.A.. He

loved sports, swimming and tennis in particular. Eric also adored

classical music, the French impressionists, Ravel and Debussy and later

on, Webern, as his tastes expanded. By age seven, Eric began playing the

clarinet, then took up saxophone by the time he turned sixteen. Dolphy

also loved the oboe and his folks, Eric Sr. and Sadie, hoped their son

might one day fill a chair in the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra. But

his music teacher, Lloyd Reese led the impressionable teenager down the

primrose path to a life in jazz, crushing Eric's parent's plans of a

more respectable and secure lifestyle for their son.

"Lloyd Reese taught Eric Dolphy; Harry Carney also studied with him

and so did Ben Webster and Buddy Collette, to name a few," Charles

Mingus wrote in the liner notes to his album Let My Children Hear Music.

"Lloyd Reese was a master musician," Mingus said. "He knew jazz and all the fundamentals of music from the beginning. He used to be the first alto player in Les Height's band. And he could play anything."

Shy and introspective as a teenager, Eric spent nearly every waking hour cloistered away in his backyard studio, practicing and studying music. Dolphy fed his voracious musical appetite with everything from field recordings of pygmy yodeling to modern composers like Schoenberg.

Viewing a rare videotape of an interview with Eric Dolphy's parents conducted years ago by Alan Saul, a college student at the time, supplied enormous insight into the multi-instrumentalist's personality and supplied this article with many of the quotes from his folks. There were long awkward silent pauses as Alan, a self-conscious, well-intentioned young hippie, held a legal pad, as he nervously looked over a long list of questions while Dolphy's parents sat on the sofa graciously obliging. Eric Sr. was reserved and thoughtful. He let his wife and his polka dot shirt do most of the talking.

Dolphy's mother Sadie recalled how he got up each morning by five to practice until breakfast and then left for school. After classes, he'd hurry back home again to work on his tone.

"He'd blow one note all day long!" Sadie exclaimed.

"For weeks at a time!" Eric Sr. added. "Then he'd play it and put it on his tape recorder and listen to it. He'd say, "Dad it's got to be right."

I'd say, "It sounds right to me."

But Eric, perfectionist that he was, replied, "No. It's not right yet."

"Sometimes we'd be sleeping and hear him plunking on the piano," Eric Sr. continued. "And I'd say, ‘Hey, what ya doin'?' He'd say, ‘I just got an idea.' And he'd be writing y'know."

"He was gonna be a musician. He wasn't gonna do anything else!" Sadie said.

"He became discouraged when he couldn't get any work. But he kept on working at it because he figured some day, somehow he'd make it."

Like every saxophonist of his generation Eric was heavily inspired by Charlie Parker. Dolphy spent years mastering Bird's technique and concepts, employing them as the foundation for his own imaginative improvisations. Lillian Polen, a close friend of Eric's at this time recalled that Dolphy wholeheartedly "worshipped Bird." She recalled regularly "falling by the Oasis," a small club on Central Avenue in LA to check out Dolphy's band. At the time, Eric worried that people would write him as just another Charlie Parker imitator.

Years later, Eric explained his inspiration for his album title Far Cry: "The title's meaning is that it's a far cry from the impact Bird had when he was alive and his position now. I wrote this to show that I haven't forgotten him or what he's meant to me. But the song also says that as great as he was, he was a far cry from what he could have been. And, finally, it says that I'm a far cry from being able to say all I want in jazz."

Eric came to prominence during a transitional period in jazz. In the evolution of the alto saxophone, his horn bridged the gap between Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman and helped usher be bop into the uncharted realm of the avant-garde or the "New Thing." His unique sense of harmony and jagged melody lines had more in common with the fractured piano of Thelonious Monk than any horn player of his time. His lyrical leaps from one register to the next spanned a broad range of emotion and expression that few musicians then or now have been capable of. Dolphy's vocabulary ranged from a gentle whisper to a full-blown anxiety attack. Like Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, Eric also battled the grim existential atmosphere of cold war era with an irrepressible howl.

"To me, jazz is like part of living, like walking down the street and reacting to what you see and hear. And whatever I react to, I can say immediately in my music," he once said.

"It was evident he had his Charlie Parker together, but little did I realize that he would become one of the groundbreakers of the new music of the Sixties," critic Ira Gitler exclaimed after witnessing Dolphy with Chico Hamilton's Quintet at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958.

At the time, Hamilton's group typified West Coast cool. Their soft tasteful chamber jazz, comprised of guitar, cello and woodwinds, was a forerunner to future New Age bands like the Paul Winter Consort and Oregon. In this setting, Dolphy's fiery approach to improvisation was rather risky. At any moment, Eric could suddenly bust Chico's groovy mood wide open with just a few slurs and squawks from his bass clarinet. Critics that just didn't get it heard Eric's joyous squeals as amateurish, shrill and offensive.

Earlier that year Buddy Collette left Chico Hamilton's Quintet, suggesting Eric Dolphy as his replacement. Eric played in the group a short time before re-locating to New York in the autumn of 1959 when he joined forces with his old friend from L.A., the volatile bassist Charles Mingus.

Back in California, Dolphy had been harshly criticized for playing out of tune.

"The public in general wasn't ready for Eric when he was in my band," Hamilton later admitted. Many complained, suggesting that Chico fire him and find someone more suitable to his smooth sound. "But Eric was such an original type player. He had a legitimate background in music to the extent of the classics and he studied with [William] Kincaid. He did everything correct. He was total music," Hamilton said in his former sideman's defense.

Chico believed it a coincidence that Dolphy became a jazz musician in the first place. He felt Eric's exceptional technique and diversity would have allowed him to pursue any style of music he desired, from classical to R&B.

Eric Dolphy arrived in Manhattan at a time when the revolutionary

concepts of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor had turned jazz on its ear.

The term avant-garde no longer belonged exclusively just to painters,

sculptors and experimental musicians with classical backgrounds (read

white Europeans, like John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen).

Ornette, in his highly personalized mission to redefine beauty, had

unleashed a strange new theory of music on the world he dubbed

"Harmolodics" (one part harmony/one part motion/one part melody)

although his bleating tone on a white plastic alto sax was considered

anything but beautiful by many. Meanwhile Cecil's scrambled madcap piano

extrapolations were demolishing traditional song structures with a

tremendous force known only to a Stravinsky symphony or an atomic blast.

On April Fools Day, 1960 Eric recorded his first album under his own name in for the New Jazz label. The cover painting for Outward Bound by an artist simply known as "The Prophet" presented a desolate green twilight zone where space and the future met. Dolphy's eyes are shut in deep concentration. Planets glow above his head. The album's title immediately identified him with the likes of Sun Ra, Coleman and Taylor. Now in hindsight, it's clear that Dolphy's musical concepts were far more conventional. His cohort and roommate at the time, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard was certainly no match for the likes of Don Cherry when it came to bending the perimeters of jazz. Once Eric played a solo and stepped back from the microphone, his band sounds ten years behind him. Although the rhythm section provided superb support and propelled the music onward and outward, there's little trace of invention or innovation in their playing.

On April Fools Day, 1960 Eric recorded his first album under his own name in for the New Jazz label. The cover painting for Outward Bound by an artist simply known as "The Prophet" presented a desolate green twilight zone where space and the future met. Dolphy's eyes are shut in deep concentration. Planets glow above his head. The album's title immediately identified him with the likes of Sun Ra, Coleman and Taylor. Now in hindsight, it's clear that Dolphy's musical concepts were far more conventional. His cohort and roommate at the time, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard was certainly no match for the likes of Don Cherry when it came to bending the perimeters of jazz. Once Eric played a solo and stepped back from the microphone, his band sounds ten years behind him. Although the rhythm section provided superb support and propelled the music onward and outward, there's little trace of invention or innovation in their playing.

Dolphy employed traditional song structures as his foundation for expression and exploration while Ornette's approach came straight out of Planet X. The kind of freedom practiced and encouraged by members of Coleman's quartet shook the very foundations of jazz at its core. Unless the listener was willing to approach the complexity of Ornette's music with an unbiased mind and open ears, allowing the sound to wash over them without analysis, they would never grasp its full impact.

Coleman's image as the era's premiere iconoclast may have overshadowed many of his peers but Dolphy's role in the avant-garde was unquestionably integral to its development. One listen to his contribution to such milestone recordings as Coleman's Free Jazz and Oliver Nelson's Blues and the Abstract Truth and John Coltrane's Live at the Village Vanguard will immediately set the record straight.

For whatever reason, many of Eric's best solos were recorded as a sideman. Free from the pressures of leading his own band, Dolphy may have been able to express himself on a deeper level, embellishing his cohort's compositions with his lyrical and explosive reed work. Or perhaps it was the camaraderie that inspired to reach a little deeper. Yet Dolphy's music stands alone as an entirely valid expression unto itself, with or without his association to Mingus, Coltrane and Coleman.

In 1960, pianist Sy Johnson played a two-week stint with Mingus at

the Showplace in Greenwich Village. According to author Janet Coleman,

Johnson recalled that once a night Mingus would inevitably chase

trumpeter Ted Curson down Fourth Street in a rage. The explosive bassist

also frequently scolded Dolphy to "play with taste."

Eric soon found a fitting, yet temporary position in the Mingus Jazz

Workshop, in a piano-less quartet that Charles led with Ted Curson and

long-time drummer Dannie Richmond. Their rendition of "Stormy Weather"

on The Candid Recordings recorded in the fall of 1960 is a prime example of the group's dynamics, telepathy and imagination.

"He had such a big sound, as big as Charlie Parker's," Mingus claimed. "Inside that sound was great capacity to talk in his music about the most basic feelings. He knew that level of language which very few musicians get down to."

"Near the end of ‘What Love' Mingus and Dolphy (on bass clarinet) have a long and different kind of conversation on their instruments, apparently about Dolphy's intention of quitting the band," Whitney Balliett revealed in Night Creatures. "Eric Dolphy and I were having a conversation about his leaving the band. Mainly it was curse words, except for Eric. Eric didn't curse until the very end of his solo," Mingus joked. "He was absolutely without a need to hurt," Charles explained. The duets at the Five Spot with Mingus playing bass and Dolphy on bass clarinet are among the greatest musical dialogues in the history of the music. "We used to talk to each other, and you could understand – and I mean understand in words – what he was saying to me," Mingus said.

Friction continued to develop between the two and by the end of the 1964 tour Dolphy had grown weary of Mingus' outrageous antics. True to form, Charles lived up to his myth as the mad, sexy genius he was, busting microphones, telephones and doors. He was also arrested for wielding a knife.

"Eric played with Mingus after I did," Composer/multi-instrumentalist David Amram told me in a recent interview. "I played French horn with Mingus in '55. Mingus loved Eric's bass clarinet. Both instruments were unusual in a jazz setting. Mingus could hear these instruments in a different way and adjust his music to what they could do. I was particularly interested in Eric's bass clarinet as I had a part for one in my opera, Twelfth Night. I told him, ‘Some of the registers you're playing on the bass clarinet, I wouldn't dare write because nobody could stay in tune or make it sound good, playing that high.' He said, ‘They should either check me out or practice,' David laughed. "He believed there were no limitations in music, that if you wanted to do it enough, you would find a way. He had a great sense of adventure and daring. He was a true improviser. Remember he had a real foundation in music. There are a lot of free jazz players these days that don't have that kind of background. He could play within the mainstream but he just followed how he felt."

Seldom does a musician's search for a new mode of expression culminate in a riotous response from their audience. The most notorious instance in the twentieth century was Igor Stravinsky's premiere of "Sacre du Printemps" in 1913. A little over fifty years later, Bob Dylan suddenly shed his Woody Guthrie/weary dust bowl bumpkin balladeer guise, put on his black leather jacket and plugged in his Stratocaster at the Newport Folk Festival. The crowd erupted in outrage and anger. In the heat of the moment, the banjo-strumming King of Sing-Along, Pete Seeger was said to have grabbed an ax with the intent of whittling the soundboard into kindling but was thankfully subdued. The folkies felt betrayed by their boy wonder. Before them stood Bob Dylan, like Judas in Beatle boots, defiantly flailing his Fender while crowing, "I ain't gonna work on Maggie's Farm No More!" His message came across loud and clear. He had turned his back on "the cause." Dylan may have sold out to rock and roll as many claimed, but he also happened to be playing some of the best damn music of his career.

With the release of My Favorite Things in the spring of 1961, John Coltrane experienced a wave of popularity unlike anything he'd ever known. With his soaring soprano saxophone, Coltrane transformed Julie Andrews' little ditty from the popular Disney film The Sound of Music into a lilting waltz that was at once romantic, accessible and cool. In the process, Coltrane had unwittingly hipped an entire generation of tweed-clad, flat-topped college kids to jazz. Even girls liked it!

Suddenly reporters from Newsweek scurried down the narrow, red-carpeted stairs of the Village Vanguard to cover the story. But it wasn't long before Rogers and Hammerstein's lovely tune became a vehicle for some of Coltrane's most torrid improvisations.

In no time, the critics attacked Coltrane like a pack of rabid hounds, tearing him apart for blowing half hour solos over a repetitive two-chord vamp. Leonard Feather believed this latest development in John's music was "retrogressive in terms of development in jazz." Feather also complained that Coltrane's endless soloing was monotonous when compared to the lush harmonic complexity of an Ellington arrangement.

"You see, that is another complexity in itself, of playing on 1 or 2 changes." Dolphy countered. Eric actually found it more challenging for a creative musician to play over a sparse framework. The simple repetition laid bare the musician's technique and intent for all to hear. With no place to hide, their shortcomings were certain to become obvious after just a few choruses.

"This automatically gives him more time to think, and it gives him the chance to unfold a lot more. Like in Indian music they only have one [chord], in our Western music we can usually hear one minor chord, but they call it a raga or scale and they'll play for twenty minutes."

Eric understood the rigorous path of discipline and practice that Indian classical musicians must endure to perfect their technique and build a musical vocabulary diverse enough to successfully improvise over a single chord without becoming redundant.

"Music contains like, rhythm and pitch, time, space and all these elements go into improvisation," Dolphy once said. "You have to take that into consideration. It's not a question of running notes, running notes in random."

Eric was deeply inspired by the hypnotic beauty of Indian music, not as a superficial trend but as a form of discipline and expression similar to his own. Years before Beatle George Harrison and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones employed the sitar's exotic twang as a condiment to their catchy pop tunes, Coltrane and Dolphy could be heard improvising within the framework of these scales on John's haunting composition "India."

As fate would have it Eric met the spectacular sitarist Ravi Shankar on his first tour of the U.S. It was a great opportunity for the multi-instrumentalist to learn about ragas, talas and other intricacies of Indian music directly the master of the form.

As Dolphy later explained it: "Classical Indian music is the music of [Indian] people and jazz is the music of the American people, especially the American Negro. Quite naturally, there's something of a connection there, of people expressing themselves in the same way [ancient blues of variable hues]. To the listener that doesn't pay close attention to the notes, the sound will get monotonous. But to the person that listens to the actual notes and the creation that's going on and the building within the players and within themselves, they'll notice that something is actually happening."

In November 1961, Trane toured England bringing Eric Dolphy along to augment his classic quartet. Jazz writer/photographer Val Wilmer believed their performance had "an enormous impact, particularly on local musicians."

Regarding the classic quartet, pianist McCoy Tyner once remarked, "That group was like four pistons in an engine. We were all working together to make the car go." If that was indeed the case, many critics and fans alike looked at the addition of Eric Dolphy as an extraneous fifth wheel.

The reaction in the press to Dolphy joining the group was second only to the Spanish Inquisition. On November 23, Down Beat published a scathing review by John Tynan, who claimed that "melodically and harmonically" the group's collective improvisations sounded like "gobbledygook."

Suddenly John and Eric were perceived as a pair of charlatans, plotting "an anarchistic course," and playing a defiant brand of "anti-jazz" that didn't swing. Both Coltrane and Dolphy were stumped by Tynan's term. Eric found the accusation confusing and absurd. "In fact, it swings so much I don't know what to do – it moves me so much," he replied. "I'd like to know how they explain ‘anti-jazz'. Maybe they can tell us something."

"There are various types of swing," Coltrane theorized. "There's 4/4, with heavy bass drum accents. Then there's the kind of thing that goes on in Count Basie's band. In fact, every group of individuals assembled has a different feeling, a different swing. It's a different feeling than in any other band," John said, regarding his quintet. "It's hard to answer a man who says it doesn't swing."

"It's kind of alarming to the musician when someone has written something bad about what the musician plays but never asks the musician anything about it. At least the musician feels bad. But he doesn't feel so bad that he quits playing," Eric countered. "The critic influences a lot of people. If something new has happened, something nobody knows what the musician's doing, he should ask the musician about it. Because somebody may like it; they might want to know something about it. Sometimes it really hurts, because a musician not only loves his work but depends on it for his living. If somebody writes something bad about musicians, people stay away. Not because the guys don't sound good but because somebody said something that has influence over a lot of people."

See Part II of the Eric Dolphy article

Eric Dolphy Turns Eighty

Photo courtesy of All About Jazz

God Bless The Child, Part II

By John Kruth

An advocate of free jazz, Dolphy was a champion of free speech as well. Ultimately Eric believed that Tynan was entitled to voice his opinion, but he questioned the motivation behind the critic's terse words. Gentle as he was, Eric would not stand by idly while somebody made ignorant comments that were damaging to both his and Coltrane's career.

Meanwhile, Dolphy lived in a lower Manhattan loft with no heat while

the winter snow blew through cracks in the bricks of his humble abode.

The criticism of Coltrane's Quintet continued in Down Beat

with a holy war fervor. Eric Dolphy, Coltrane's controversial cohort,

was blamed of inciting John to abandon his modal melodies and explore

the outer reaches of the avant garde.

John immediately rose to his partner's defense, claiming Eric was a

long time friend and a student of jazz with whom he freely exchanged

ideas. Coltrane recalled the first time that Dolphy sat in with his

group - "Everyone enjoyed it because his presence added some fire to the

band," he said.

According to biographer Bill Cole, Dolphy had an enormous influence

on Coltrane's music. "Trane made very few big musical decisions without

first consulting with him," Cole claimed. "I was always calling him on

the phone and he was calling me and we'd discuss things musically, so we

might as well be together. Maybe we can help each other some. I know he

helps me a lot," Coltrane told Benoit Querson.

"Eric is really gifted and I feel he's going to produce something

inspired," Coltrane predicted in 1961. "We've been talking about music

for years but I don't know where he's going and I don't know where I'm

going. He's interested in progress, however, and so am I, so we have

quite a bit in common."

"Eric was a very, very gifted musician and a very nice guy on top of

it," McCoy Tyner told me in a recent interview. "He had a very personal

approach to playing and enjoyed expanding the limits of imagination.

Eric played so many instruments, his pockets were bulging with all these

mouthpieces," McCoy said chuckling at the memory. "He was the first guy

to come on as a guest with the band. At the time he came along he was

doing his own thing and made a tremendous impression. We felt that the

quartet was self-contained. Jimmy, Elvin and I felt that we had built

something and were still on that journey. We didn't exactly understand

where John was going in terms of adding Eric. We were like little kids

in a sense like this is our band and we want to keep it that way. But

then again it wasn't like we didn't want to share our experience. John

was the leader and he was the one that made the final decisions. He

decided that maybe if I do this, this will cause something else to

happen. And it did! They played so differently. Eric added another

dimension to the sound. John never rested on his laurels. He was like a

scientist in the laboratory always searching for something new or

different. By adding Eric he was expanding the music. John and Eric had a

very different type of life experience. Eric had a very academic

approach. He studied a lot. John coming from the South had that real

gutsy approach. His father was a minister and his grandfather was a

minister. He spent a lot of time in church and you could hear that in

the music. At the same time there were points where the two met and

could make something very interesting happen."

"Eric added a very interesting component to the music," McCoy

continued. "John believed in what Eric was doing. He wanted to help him.

At the same time he wanted to open the music up. It was a very good

experience for Eric as well, being surrounded by the quartet. Ole

was one of the highlights of Eric's presence. He had his own approach

to the bass clarinet. He had personal things he would do on the

instrument and got sounds out of it that you normally didn't hear on a

bass clarinet. He was very animated and very enthusiastic."

Augmenting the Coltrane Quartet at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1961

was Eric Dolphy and guitar great Wes Montgomery for an hour long set

which consisted of just three tunes, "My Favorite Things," Coltrane's

transcendent ballad "Naima" and Miles Davis's "So What." The subsequent

review in Down Beat offered praise to Montgomery's "rhythmic flair"

while knocking John for making "animal sounds."

Once again it was open season on Eric Dolphy. "While his flute work

was generally good, part of his solo sounded as if he were trying to

imitate birds. His use of quartertone on ‘Things' led nowhere. And this

seemed his greatest hang-up; none of his solos had a clear direction."

The idea of Dolphy enhancing "My Favorite Things" with bird songs on

his flute, or in Coltrane's case, creating "animal sounds" on his

soprano saxophone seems more playful than something to get bent out of

shape about, after all the song's lyric mentions bees, kittens and dogs!

"Eric told me that one morning that when he got up, the birds were

singing outside his window and he said, ‘Oh!' and that became part of

his music," journalist Nat Hentoff said in a recent phone interview.

"This musician embodied what I call the life-force of jazz. You could

feel the intensity of his need to express himself in everything he did.

But it was always himself. He was one of the true originals in the

field."

The basis for Dolphy's approach to improvisation rarely relied on

the song's chord progression alone. "They're based on freedom of sound.

You start with one line and you keep inventing as you go along. And you

keep creating until you state a phrase," he explained to Leonard

Feather.

"You use other notes in the chord to give you certain expressions to the song, otherwise you'd be playing what everybody else is playin'. The thing only happens at the moment when you do it, and quite naturally it might change," Eric said, hoping to shed some light on the elusive process of improvisation.

When Eric Dolphy moved to Manhattan in 1960, he first joined the Mingus Workshop, then later that same year he began playing with Ornette Coleman.

"I heard about him and when I heard him play, he asked me if I liked

his pieces and I said I thought they sounded good," Eric told Martin

Williams. "When he said that if someone played a chord, [he said] he

heard another chord on that one. I knew what he was talking about,

because I had been thinking the same things."

Dolphy soon signed on as a member of Coleman's double quartet, which

featured two drummers, two bassists, two trumpets and Dolphy and Ornette

on reeds and yielded the watermark recording Free Jazz.

"I had known Eric back in the fifties when I shared some music that I

had been working on with him," Ornette Coleman told me recently. "He

was very open to the things that I was doing. I think that he thought I

was not in his class of perfection because I had just come to California

from the South. But it didn't bother me. There was an appreciation from

one musician to another. I invited him to play on my Free Jazz

record and he asked me, ‘Which instrument would you like for me to

play?' I said, ‘It doesn't matter. I wasn't concerned about him being

the worst or best or whatever. I was concerned about him expressing the

things he wanted to."

In retrospect, it's surprising that Coleman's music caused such a maelstrom. Many of his compositions have an almost child-like, singsong quality while others reveal a West-Indian calypso feel. His drummers, Eddie Blackwell and Billy Higgins always swung hard. In his unorthodox approach to group soloing, which had its roots in traditional New Orleans music, Ornette would forge a fresh, new, dimension of sound. No matter how radical his concept of Harmolodics, Coleman never completely abandoned changes that chords (if they had been employed) inferred.

"You CAN play every note you like," Dolphy told Leonard Feather, in a desperate attempt to convey the essence of the new music. "Of course, you can only play what you can hear, and quite naturally... more or less I guess what I hear is not your hearing."

"As I play more and more, I hear more notes to play against the more

common chord progressions. And a lot of people say they're wrong. Well, I

can't say they're right, and I can't say they're wrong. To my hearing,

they're exactly correct," Eric mused.

It seems that Dolphy was simultaneously cursed and blessed with, as

he put it "a whole different type of hearing." Ultimately it was Eric's

refreshingly open and inquisitive nature to life and sound that allowed

him to utilize a wider range of expression than many of his peers.

"Eric Dolphy is a hell of a musician, and he plays a lot of horn.

When he is up there searching and experimenting I learn a lot from him,"

John Coltrane commented.

"He was just brimming over with ideas all the time," Elvin Jones

said. "In fact that was probably his biggest problem… he just had too

much to say, and this occasionally would get in the way of his saying

it."

Jones felt Dolphy lacked the "self discipline" needed to express all

his ideas clearly. Although the last time Eric played with Coltrane's

group Elvin felt Dolphy "was better organized in his musical thinking."

Jones also admired Eric's confidence on the bandstand, claiming he

"never heard him hesitate" in the heat of the moment. "He was always

ready – if you wanted to play, he was there," Elvin declared.

"Eric never stood still with his music," George Avakian once said. The

pianist/producer believed one day Dolphy would get his props as "the

father of the new thing."

"He was very influential in the avant-garde movement," close friend,

bassist Richard Davis said in a phone interview. "He was one of the

forerunners in that area. I was fortunate to work with him," Richard

said, claiming that Eric was a major inspiration on his musical

development.

"I rate him as a genius. I knew what was inside his music; I was

familiar with it and how he put it together." Davis believed that

whether or not people understood Dolphy's music they could still

"appreciate the tremendous feeling in his playing."

Their interpretation of "Come Sunday," Duke Ellington's wistful

ballad was their finest of many duets. Notes from Dolphy's bass clarinet

sputter and bubble up like black tar on a hot July afternoon while

Davis serenely bows the melody. Eric's clarinet suddenly leaps registers

in a single bound, reeling and collapsing like Ray Bolger's weak in the

knee scarecrow until finally catching up to Richard and taking over the

melody, allowing Davis to stretch out.

On classic recordings like Dolphy's own Iron Man and Nelson's Blues and the Abstract Truth,

Eric's alto sax can be heard zigzagging like a crazy figure skater,

carving figure eights into your brain. Sound splashes and sloshes around

in your ears like Jackson Pollock spilling his drink. Perhaps to some

Dolphy's playing comes off as a bit of sonic slapstick at times, but he

knows how take it right to the edge, like a carnival clown riding a

unicycle on a tight-rope wire who appears out of control. But just

before falling to his certain death, he suddenly regains his balance,

much to the crowd's relief. If you think for a moment that Eric Dolphy

is lost, the joke is on you. His intent was to stretch musical

boundaries, not to deliberately shatter them.

"Eric was, first and foremost a person who respected the tradition

and wanted to extend the tradition or extend the creativity in

accordance with the most positive aspects of what he brought forth from

the tradition," Anthony Braxton once said.

"Many musicians did not understand Eric and were critical of his

work," Third Stream composer Gunther Schuller claimed. "I could never

understand, for example, how perfectly respectable musicians could say

that Eric didn't know his changes," Schuller said, sighting Dolphy's

inspired soloing on the Mingus arrangement of "Stormy Weather."

"I play notes that would not ordinarily said to be in a given key,

but I hear them as proper. I don't think I ‘leave the changes' as the

expression goes; every note I play has some reference to the chords of

the piece," Eric offered.

In a Down Beat Blindfold Test, Miles Davis once famously quipped that Dolphy sounded "like somebody was standing on his foot."

Avant-garde guitarist/reedman/composer Elliott Sharp had a different

response altogether. "It was pure mystery. When I heard Dolphy's bass

clarinet playing, it was like a voice from Mars. It was so vocal. It was

like he was speaking in tongues," Sharp told me. "I knew I had to get

one at some point."

Surprisingly, the daddy of dada rock Captain Beefheart (a neophyte at

best on the bass clarinet) found Eric's music "real limited." "It

didn't move me," he complained to Lester Bangs years ago in Musician magazine.

"Dolphy didn't MOVE you?" Bangs replied incredulously. "Well he moved

me," Beefheart allowed, "but he didn't move me as much as a goose, say.

Now that could be a hero, a gander goose could definitely be a hero,

the way they blow their heart out for nothing like that."

"Like any mature, creative musician, Eric was not unduly disturbed by

such comments," Gunther Schuller countered. "It was his nature to turn

everything – even harsh criticism – to some positive, useful purpose. In

the seven or eight years I knew Eric, I never heard him say a harsh

word about anything or anybody connected with music. This was a sacred

territory to him and I think he sincerely believed that anything as

beautiful as music could only produce more beauty in people."

"He was always real modest," his mother Sadie recalled. "We never

realized either how well thought of he was. He was always a happy

person. Even if things weren't going well you'd never notice. He was

always happy and always helping someone else, even though he didn't have

too much money. He'd always be takin' somethin' to somebody else, some

musician, if they were out of work. When musicians came to town and he

found out they had a family he would give them his job. He'd take them

to the job sometimes because he always had a car. He'd tell them, ‘you

have kids while I live at home where I can always eat.'"

Tales of Eric Dolphy's gentle, compassionate nature are almost as

legendary as his musicianship. Richard Davis remembered Eric as "a

beautiful person." "Even when he didn't have enough for himself, he'd

try to help others," he said, recalling Eric's generosity and concern

for others. "I remember how he once bought groceries for a friend who

was out of work, though he was just as much in need himself."

Mingus simply referred to Eric as "a saint," and named his son the singer, Eric Dolphy Mingus in his honor.

In the spring of 1964, Dolphy left Mingus' band while on a tour of Europe and planned to live in Paris where quite a number of expatriate musicians found themselves welcome with open arms. But that June, Dolphy suddenly died due to complications from diabetes. Two months earlier Mingus had composed and recorded a blues entitled "So Long Eric" which he maintained was not a "eulogy" but a "complaint."

Eric Dolphy died in Berlin, on June 29, 1964 just nine days after his

thirty-sixth birthday. He'd arrived two days earlier to play a new club

called the Tangente. Seriously ill, he barely made it through the first

two of the evening's three scheduled sets before having to leave the

bandstand. The next day, wracked with pain and delirious, Eric could

barely utter the words "Take me home… Take me home..."

The next day Eric Allan Dolphy got his hat. According to doctors at

Berlin Achenbach, Hospital the brilliant multi-instrumentalist was a

diabetic with too much sugar in his bloodstream. They claimed that Eric

was unaware of his condition. He had also suffered a complete collapse

of his circulatory system as well.

Sadie Dolphy said her son never suffered from heart disease or

diabetes. "He never complained about anything," she lamented. Mrs.

Dolphy believed her son died so young as a result of always pushing

himself too hard. The funeral took place on July 9, in Los Angeles.

"Whatever I say would be an understatement. I can only say my life

was made much better by knowing him. He was one of the greatest people

I've ever known, as a man, a friend, an as a musician," a shocked John

Coltrane murmured after hearing the news of his friend's death.

"So close was their relationship that Dolphy's mother gave Trane

Eric's bass clarinet because she claims that she had nightmares about

Eric playing the instruments," Bill Cole recalled in his biography of

John Coltrane.

Mingus and Eric's relationship was of a far more complex nature.

"There was not a lot of conversation; at times it seemed as though

Charles disliked him but at the same time it was also the feeling that

he loved him dearly," Danny Richmond surmised. "And there were times

when they dueled musically with each other on the bandstand. So that

Eric's death I know it affected Charles very, very deeply. I have a

feeling that there was something left unsaid between the two of them."

Mingus maintained that Dolphy had been murdered. Charles recalled

that a Manhattan physician named Finklestein had given Eric a thorough

check-up and a clean bill of health before leaving on their tour of

Europe. Before departing Eric had undergone an operation to remove the

egg-shaped tumor from his forehead. "This would not have been done if

Eric had been a diabetic," Mingus protested.

At the time, drummer Sunny Murray had also been touring Europe with

saxophonist Albert Ayler, playing their unique brand of spiritual free

jazz in an explosive quartet featuring bassist Gary Peacock and Don

Cherry.

"See I was getting strange vibrations all the time we was in Europe,"

Murray said. "We were getting very in tune with the spirits when the

Free Jazz group was over there – we were the most spiritual band in

Europe at the time. Eric Dolphy, who had come over earlier with Mingus

had remained in Europe to play with us, with the Free Jazz group. He

wanted to bust loose and really play free. But he died suddenly. Rumor

was that he was poisoned. That set me off and I began to realize that a

lot of people were doing things to me to hang me up and I started to get

very nervous."

As we know, the sixties was a politically volatile era. Everywhere,

the air was rife with revolution and conspiracy. It has been said time

and time again of that highly romanticized decade - if you weren't

paranoid, you weren't paying attention.

Eventually, Coltrane and Dolphy's devotion to music developed into a

relentless quest to find God. They began living on a steady diet of

honey, and conversation was reserved for all things holy.

"Eric Dolphy died from an over dose of honey," arranger/band leader

Gil Evans believed. "Everybody thinks that he died from an overdose of

dope but he was on a health kick. He got instant diabetes. He didn't

know he had it. He's eating nuts and a couple little jars of honey every

day [and] it killed him. He went into a coma and never came out of it."

At the end of Alan Saul's video, he sits on Dolphy's sofa asking if they ever feel bitter about the way things all went down.

"He wasn't that big," Eric Sr. lamented. "Just before he died he was

just getting up; just coming into his own, but he passed away."

"No... No..." Sadie answered with a sigh. "It could have been better

but life is a struggle and we are people that are used to strugglin'."

December 28, 2008

Out There: The Music of Eric Dolphy

'When you hear music, after it's over, it's gone, in the air. You can never capture it again.'

--Eric Dolphy

I first encountered Eric Dolphy's name on the cover of his most famous solo album, Out to Lunch (Blue

Note). I've seen it in a thousand jazz bargain bins, and it surfaces

time and again in the classic all-time lists. It took me awhile to get

my head around Dolphy's playing, whether it was the flute, the clarinet

or the alto saxophone: his approach often sounded more like a

cacophonous noise than an attempt to play, and the lack of coherency was

something that completely turned me off. In some ways, I associated his

playing with the spoofs and potshots often attributed to avant garde

jazz: the image of the jazz musician as pretentious and aloof, making a

ridiculous noise and calling it art.

So I put Out to Lunch to

one side for awhile, and instead settled for more traditional jazz

music. I have always been a great fan of Charles Mingus, not simply for

his mastery of the double-bass but for his big, brash compositions -

filled with an energy and a power that was invigorating for my walk home

from work. I listened to Blues and Roots and Mingus Ah Um during this period, before extending myself toward some of the live recordings. Mingus at Antibes came

at the top of this particular list, and I found myself playing it on my

iPod every time I left the house. It was the perfect music for

footsteps, and for a sense of gathering momentum.

Mingus is the master of powerful build-ups, and Mingus At Antibes includes

some of his greatest works. But what makes them so precious is the fact

that they are live life recordings: they are at times sloppy and

disorganized, but the momentum carries each tune forward to its climax,

and it's all completely captivating. There's a lust for life in this

music that's difficult, if not impossible, to ignore. And in all

honesty, I think that Charles Mingus was one of the key figures that

drew me toward jazz music. The bass got you hooked, and the music

carried you away. I can't even count the number of times I've listened

to Mingus while walking down a busy city street, a beaming smile all

over my face. It's joyous stuff.

It was at this point that I discovered Eric Dolphy all over

again, as an alto saxophonist in Mingus's band. There are seconds where

the tumultuous storm of the music, or the swelling of the melody, falls

into silence, and Dolphy takes over. The sound, or tone, of the

instrument is so clear and unique, that you begin to hear it in other

recordings as distinct and unique to Dolphy himself. Suddenly I could

recognize him in a crowd: no one else plays like that.

But it wasn't just the sound of the instrument that stuck with me,

but the notes he played. Eric Dolphy's approach would take something

from the overall narrative of a given piece, and then blast off with

something that was absolutely his own. This could mean a repetition of a

main theme, or notes played in harmony with the rhythm, but at its apex

it would dart and blast and resist all of these things at once. The

music would suddenly take off in a saxophone solo that sounded

simultaneously catchy and avant garde, although there was no longer a

tune to be heard or grappled with. Eric Dolphy's solo would reduce each

recording to a series of super-fast squeaks and squawks and crazy

hell-bent yelps. But, by some miracle, you could tap your foot to it.

I started to hear some kind of logic in Dolphy's music from

that point onwards. He fitted perfectly into the Mingus ensemble, and

managed to bring something new to the table without detracting from the

talent that was around him: they worked together seamlessly, in a way

that added finesse and excitement and drama to the music. It gave each

track the sense that it really was performed live and in the moment, and

this has a captivating effect on the listener.

So I began to trace some of Eric Dolphy's solo work, from Out to Lunch to Outward Bound and Out There.

A pattern begins to emerge, that self-consciously separates Dolphy from

his time and place in the history of jazz: he continually positions

himself outside of traditional, conventional musical standards and finds