AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION

(ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK

ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/11/max-roach-1924-2007-legendary-iconic.html

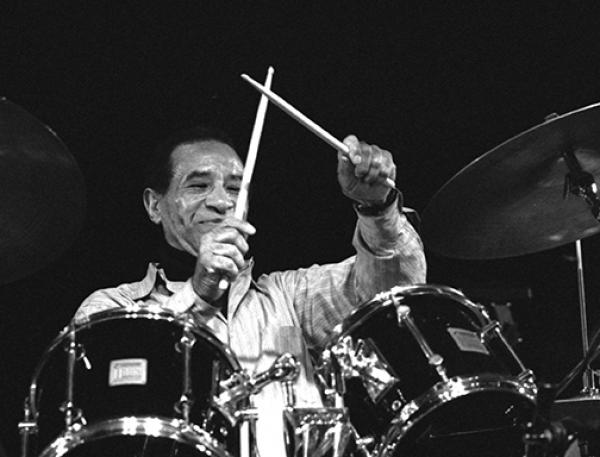

PHOTO: MAX ROACH (1924-2007)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/max-roach-mn0000396372/biography

Max Roach

(1924-2007)

Biography by Thom Jurek

One of the most gifted musicians in jazz history, Max Roach helped establish a new vocabulary for jazz drummers during the bebop era and beyond. He shifted the rhythmic focus from the bass drum to the ride cymbal, a move that gave drummers more freedom. He told a complete story, varying pitch, tuning, patterns, and volume. He was a brilliant brush player, and could push, redirect, or break up the beat. In 1948 he participated in Miles Davis' seminal Birth of the Cool sessions before forming his own quintet with iconic bop trumpeter Clifford Brown. In 1953, he served as drummer in "the quintet" for the historic Jazz at Massey Hall concert, alongside Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Charles Mingus. Later, the drummer's seminal 1961 We Insist! Freedom Now Suite set the tone for Civil Rights activism among his peers. Throughout the 1970s and '80s, Roach continued breaking new ground. He formed the percussion ensemble M'Boom in 1970, issuing a handful of acclaimed albums including 1973's Re: Percussion, M'Boom in 1979, and To the Max in 1991. He worked with vanguard musicians including storied duos with Anthony Braxton (The Long March) and Cecil Taylor (Historic Concerts). During the '90s Roach taught at the University of Massachusetts and continued to perform. He never stood still musically: he worked in trios, with symphony orchestras, backed gospel choirs, and with rapper Fab Five Freddy. Friendship, his final album in collaboration with trumpeter Clark Terry, was issued in 2002.

Roach was born in rural North Carolina in 1924. His mother sang gospel. His family moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, New York in 1928. Roach began his musical vocation as a child playing bugle in parades. He started playing drums at seven, and at ten, he was playing drums in gospel bands. He started playing jazz in earnest while in high school. In 1942, as an 18-year-old graduate, he received a call to fill in for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan. He starting hanging out and sitting in at the jazz clubs on 52nd Street, and at 78th Street & Broadway. His first professional recording took place in December 1943, backing saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. While serving as house drummer at Minton's Playhouse, he fell in with saxophonist Charlie Parker, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and others at the famed locale. He was a frequent participant in after-hours jam sessions. Roach played brief stints with Benny Carter and Duke Ellington's band, then joined Gillespie's quintet in 1943 and served in Parker-led bands in 1945, and from 1947 to 1949. Roach traveled to Paris with Parker in 1949 and recorded there with him and others including Kenny Dorham. He also played with Louis Jordan, Red Allen, and Hawkins. He participated in Miles Davis' historic Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949.

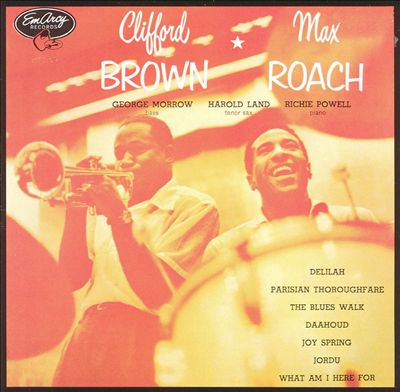

Roach enrolled in a classical percussion degree course at the Manhattan School of Music in 1950. He picked up with Parker again in 1951, and remained with him until he left school in 1953. During that tenure he served as drummer in "the quintet," and played at the historic Jazz at Massey Hall concert in Toronto with Charles Mingus, Bud Powell, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bird. These concerts marked the final time that the latter two would play together. During the early 1950s, Roach also toured with the Jazz at the Philharmonic revue, and recorded with Howard Rumsey's Lighthouse All-Stars, replacing Shelly Manne. During the mid-'50s, he was a sideman with Sonny Rollins for several years and co-led the Max Roach/Clifford Brown orchestra, with Powell's brother Richie on piano and saxophonists Harold Land and later, Rollins. Roach's frenetic, yet precise drumming laid the foundation for Brown's amazing trumpet solos. This group made landmark records during its short tenure, among them Clifford Brown & Max Roach (1954), Study in Brown and Brown and Roach Incorporated (1955), and At Basin Street (1956). Brown and Powell were tragically killed in a car crash on the way to a gig in Chicago in 1956. A devastated Roach tried to keep the group alive with Dorham and Rollins, and later with trumpeter Booker Little and saxophonist George Coleman. He became involved in a record label partnership with Charles Mingus, forming Debut Records in the mid-'50s. The label issued Jazz at Massey Hall in 1958 and Percussion Discussion (considered an avant-garde release at the time). Roach also appeared with Dorham, pianist Ramsey Lewis, saxophonist Hank Mobley, and bassist George Morrow. Later, he led another influential band, this time with Little, Coleman, tuba player Ray Draper, and bassist Art Davis. They cut seminal dates for Riverside and Emarcy, among them Deeds Not Words.

After playing with pianist Randy Weston on Uhuru Afrika, Roach, a deeply committed Civil Rights activist, composed and recorded We Insist! Freedom Now Suite in 1960. A multi-faceted work, it featured vocals by his then-wife Abbey Lincoln and lyrics by Oscar Brown, Jr. It vehemently confronted racial injustice in America, and its influence endures in the 21st century. In 1962, he recorded Money Jungle, a collaborative album with Mingus and Ellington. It is regarded as one of the finest trio albums ever put to tape. Roach and his various bands recorded and toured frequently. He released the collaborative Much Max with Stanley Turrentine in 1964 and the now-classic Drums Unlimited in 1966. In 1968 Roach and the Turrentine Brothers released Let's Groove for Time Records.

In 1970, Roach formed his long-lived percussion ensemble M'Boom. Its original members included Roy Brooks, Warren Smith, Joe Chambers, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, and Freddie Waits. The following year, he led a sextet that included saxophonist Billy Harper, trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater, pianist George Cables, electric bassist Eddie Mathias, and percussionist Ralph MacDonald. This group collaborated with gospel singers J.C. and Dorothy White, Ruby McClure, and a 22-voice choir to record the enduring jazz/gospel fusion outing Lift Every Voice and Sing for Atlantic. The six-track set offered sometimes radical rearrangements of gospel standards arranged by William Bell, Lincoln, and Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson.

Re:Percussion, the debut album by M'Boom, was released by Strata East in 1973 and reissued by Japan's Baystate the following year. Roach continued recording prolifically for various labels. In 1976, he cut the oft-reissued Force - Sweet Mao - Suid Afrika 76 in a duo with saxophonist Archie Shepp, and a year later released The Loadstar for Italy's Horo label, leading a quartet with Harper, Bridgewater, and bassist Reggie Workman. He cut the duo offering Streams of Consciousness with pianist Abdullah Ibrahim in 1977. The drummer's quartet -- with bassist Calvin Hill in place of Workman -- issued Confirmation in 1978, the same year Roach and Anthony Braxton released the duo offering Birth and ReBirth for Black Saint.

In 1980, Columbia released M'Boom. Recorded the previous year, this eponymously titled offering is regarded by critics and historians alike as foundational in the evolution of jazz and world music as it wove together strands from jazz, salsa, African and European traditions. That same year, the drummer's quartet released Pictures in a Frame for Soul Note, and Roach and Shepp recorded and released the double-live duo album The Long March on Switzerland's Hat Hut label, recorded at their concert at the Willisau Jazz Festival. During the same festival, Roach and Braxton played and recorded a duo concert, releasing it as One in Two-Two in One in 1980. In 1981, the Roach quartet, with saxophonist/flutist Odean Pope replacing Harper, issued the charting Chattahoochee Red for Columbia. The following year that group released the historic In the Light, and the drummer issued Swish, a duo with pianist Connie Crothers. In 1984, a December 1979 duo concert between Cecil Taylor and Roach was released as Historic Concerts on Soul Note. That same year, the drummer released Long as You're Living, his Enja debut, with a new quintet including trombonist Julian Priester, Stanley and Tommy Turrentine, and bassist Bobby Boswell, as well as the quartet recordings Scott Free, It's Christmas Again, and Survivors. 1984 also saw the release of Collage, the third album from M'Boom. During that decade, Roach performed with many ensembles, including a group of break dancers and rapper Fab 5 Freddy in what may be the first fusion of jazz and hip-hop.

In 1985 he released Live at Vielharmonie Munich featuring the Swedenborg String Quartet; it was billed to the Max Roach Double Quartet. He followed it that year with Easy Winners in collaboration with the Uptown String Quartet that included his daughter, Maxine Roach, on viola. The string group's name morphed into the Max Roach Double Quartet for 1986's Bright Moments. On June 15, 1989 at La Grande Hale, in La Villette, Paris, Roach took part in the Paris All Stars: Homage to Charlie Parker concert alongside saxophonists Jackie McLean, Phil Woods, and Stan Getz, Gillespie, pianist Hank Jones, bassist Percy Heath and vibraphonist Milt Jackson. The set was released by A&M in 1990 alongside a duo recording with Gillespie simply titled Paris 1989. The year also saw the Manhattan School of Music award Roach -- who had begun teaching full time at University of Massachusetts, Amherst -- an honorary doctorate. He also released Drum Conversation, his first solo percussion album. In 1992, M'Boom issued their final offering, Live at S.O.B.'s for the Blue Moon label.

In 1994, he appeared on Rush drummer Neil Peart's Burning for Buddy, performing "The Drum Also Waltzes" Pt. 1 and Pt. 2 on the first of the two-volume tribute set. Roach spent most of his time teaching, but still performed and discovered new directions in jazz. In 1998, he released Beijing Trio, a collaborative date on the Asian Improv label with pianist Jon Jang and famed erhu player Jiebing Chen. The following year, Explorations ... To the Mth Degree, a duo performance with Mal Waldron from the latter's 1995 70th birthday concert, was released by Slam Productions. In 2002, Roach teamed with longtime friend and trumpeter Clark Terry to release Friendship with bassist Marcus McLaurine and pianist Don Friedman for Columbia. It was the drummer's final album. He became less active due to several forms of illness. Roach died in New York of complications related to Alzheimer's in August 2007.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/max-roach/

Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel Roach is a percussionist, drummer, and jazz composer. He has worked with many of the greatest jazz musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins. He is widely considered to be one of the most important drummers in the history of jazz.

Roach was born in Newland, North Carolina, to Alphonse and Cressie Roach; his family moved to Brooklyn, New York when he was 4 years old. He grew up in a musical context, his mother being a gospel singer, and he started to play bugle in parade orchestras at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands. He performed his first big-time gig in New York City at the age of sixteen, substituting for Sonny Greer in a performance with the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

In 1942, Roach started to go out in the jazz clubs of the 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom (playing with schoolmate Cecil Payne). He was one of the first drummers (along with Kenny Clarke) to play in the bebop style, and performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis.

Roach played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy 1945 session, a turning point in recorded jazz.

Two children, son Daryl and daughter Maxine, were born from his first marriage with Mildred Roach. In 1954 he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and had another son, Raoul Jordu.

He continued to play as a freelance while studying composition at the Manhattan School of Music. He graduated in 1952.

During the period 1962-1970, Roach was married to the singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of Roach's albums. Twin daughters, Ayodele and Dara Rasheeda, were later born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach.

Long involved in jazz education, in 1972 he joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

In the early 2000s, Roach became less active owing to the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications.

Renowned all throughout his performing life, Roach has won an extraordinary array of honors. He was one of the first to be given a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant, cited as a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France, twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, elected to the International Percussive Society's Hall of Fame and the Downbeat Magazine Hall of Fame, awarded Harvard Jazz Master, celebrated by Aaron Davis Hall, given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by the University of Bologna, Italy and Columbia University.

In 1952 Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus. This label released a record of a concert, billed and widely considered as "the greatest concert ever," called Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Mingus and Roach. Also released on this label was the groundbreaking bass-and- drum free improvisation, Percussion Discussion.

In 1954, he formed a quintet featuring trumpeter Clifford Brown, tenor saxophonist Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell), and bassist George Morrow, though Land left the following year and Sonny Rollins replaced him. The group was a prime example of the hard bop style also played by Art Blakey and Horace Silver. Tragically, this group was to be short-lived; Brown and Powell were killed in a car accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in June 1956. After Brown and Powell's deaths, Roach continued leading a similarly configured group, with Kenny Dorham (and later the short-lived Booker Little) on trumpet, George Coleman on tenor and pianist Ray Bryant. Roach expanded the standard form of hard-bop using 3/4 waltz rhythms and modality in 1957 with his album Jazz in 3/4 time. During this period, Roach recorded a series of other albums for the EmArcy label featuring the brothers Stanley and Tommy Turrentine.

In 1960 he composed the "We Insist! - Freedom Now" suite with lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. Using his musical abilities to comment on the African-American experience would be a significant part of his career. Unfortunately, Roach suffered from being blacklisted by the American recording industry for a period in the 1960s. In 1966 with his album Drums Unlimited (which includes several tracks that are entirely drums solos) he proved that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, rhythmically cohesive phrases. He described his approach to music as "the creation of organized sound."

Among the many important records Roach has made is the classic Money Jungle 1962, with Mingus and Duke Ellington. This is generally regarded as one of the very finest trio albums ever made.

During the 70s, Roach formed a unique musical organization—"M'Boom"—a percussion orchestra. Each member of this unit composed for it and performed on many percussion instruments. Personnel included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.

Not content to expand on the musical territory he had already become known for, Roach spent the decades of the 80s and 90s continually finding new ways to express his musical expression and presentation.

In the early 80s, he began presenting entire concerts solo, proving that this multi-percussion instrument, in the hands of such a great master, could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these solo concerts; a solo record was released by Bay State, a Japanese label, just about impossible to obtain. One of these solo concerts is available on video, which also includes a filming of a recording date for Chattahoochee Red, featuring his working quartet, Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater and Calvin Hill.

He embarked on a series of duet recordings. Departing from the style of presentation he was best known for, most of the music on these recordings is free improvisation, created with the avant-garde musicians Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, Abdullah Ibrahim and Connie Crothers. He created duets with other performers: a recorded duet with the oration by Martin Luther King, "I Have a Dream"; a duet with video artist Kit Fitzgerald, who improvised video imagery while Roach spontaneously created the music; a classic duet with his life-long friend and associate Dizzy Gillespie; a duet concert recording with Mal Waldron.

He wrote music for theater, such as plays written by Sam Shepard, presented at La Mama E.T.C. in New York City.

He found new contexts for presentation, creating unique musical ensembles. One of these groups was "The Double Quartet." It featured his regular performing quartet, with personnel as above, except Tyrone Brown replacing Hill; this quartet joined with "The Uptown String Quartet," led by his daughter Maxine Roach, featuring Diane Monroe, Lesa Terry and Eileen Folson.

Another ensemble was the "So What Brass Quintet," a group comprised of five brass instrumentalists and Roach, no chordal instrumnent, no bass player. Much of the performance consisted of drums and horn duets. The ensemble consisted of two trumpets, trombone, French horn and tuba. Musicians included Cecil Bridgewater, Frank Gordon, Eddie Henderson, Steve Turre, Delfeayo Marsalis, Robert Stewart, Tony Underwood, Marshall Sealy, and Mark Taylor.

Roach presented his music with orchestras and gospel choruses. He performed a concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He wrote for and performed with the Walter White gospel choir and the John Motley Singers. Roach performed with dancers: the Alvin Aily Dance Company, the Dianne McIntyre Dance Company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company.

In the early 80s, Roach surprised his fans by performing in a hip hop concert, featuring the artist-rapper Fab Five Freddy and the New York Break Dancers. He expressed the insight that there was a strong kinship between the outpouring of expression of these young black artists and the art he had pursued all his life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Roach

Max Roach

In the mid-1950s, Roach co-led a pioneering quintet along with trumpeter Clifford Brown. In 1970, he founded the percussion ensemble M'Boom. He made numerous musical statements relating to the civil rights movement.

Early life and career

Max Roach was born to Alphonse and Cressie Roach in the Township of Newland, Pasquotank County, North Carolina, which borders the southern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp. The Township of Newland is sometimes mistaken for Newland Town in Avery County, North Carolina. Although his birth certificate lists his date of birth as January 10, 1924, Roach has been quoted by Phil Schaap, saying that his family believed he was actually born on January 8, 1924.[4]

Roach's family moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, when he was four years old. He grew up in a musical home with his gospel singer mother. He started to play bugle in parades at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands.

In 1942, as an 18-year-old recently graduated from Boys High School in Brooklyn, he was called to fill in for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra performing at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan. He starting going to the jazz clubs on 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom, where he played with schoolmate Cecil Payne.[5] His first professional recording took place in December 1943, backing Coleman Hawkins.[6]

He was one of the first drummers, along with Kenny Clarke, to play in the bebop style. Roach performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis. He played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy Records November 1945 session, which marked a turning point in recorded jazz. His early brush work with Powell's trio, especially at fast tempos, has been highly praised.[7]

Roach nurtured an interest in and respect for Afro-Caribbean music and traveled to Haiti in the late 1940s to study with the traditional drummer Ti Roro.[8]

1950s

Roach studied classical percussion at the Manhattan School of Music from 1950 to 1953, working toward a Bachelor of Music degree. The school awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in 1990.

In 1952, Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus. The label released a record of a May 15, 1953 concert billed as "the greatest concert ever", which came to be known as Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Parker, Gillespie, Powell, Mingus, and Roach. Also released on this label was the groundbreaking bass-and-drum free improvisation, Percussion Discussion.[9]

In 1954, Roach and trumpeter Clifford Brown formed a quintet that also featured tenor saxophonist Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell), and bassist George Morrow. Land left the quintet the following year and was replaced by Sonny Rollins. The group was a prime example of the hard bop style also played by Art Blakey and Horace Silver.

The Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet created one of the very greatest string of small-group recordings in jazz history, worthy of consideration alongside the Hot Fives and Sevens of Louis Armstrong and the quintets of Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. Over the next eight years Roach's stature grew as he recorded with a host of other emerging artists (including Bud Powell, Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk) and co-founded Debut, one of the first artist-owned labels, with Charles Mingus. Roach participated in the legendary bebop summit concert that produced the Jazz at Massey Hall recordings of 1953. Later that year, he relocated to the Los Angeles area, where he replaced Shelly Manne in the popular Lighthouse All Stars.[10]

Brown and Richie Powell were killed in a car accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in June 1956. The first album Roach recorded after their deaths was Max Roach + 4. After Brown and Powell's deaths, Roach continued leading a similarly configured group, with Kenny Dorham (and later Booker Little) on trumpet, George Coleman on tenor, and pianist Ray Bryant. Roach expanded the standard form of hard bop using 3/4 waltz rhythms and modality in 1957 with his album Jazz in 3/4 Time. During this period, Roach recorded a series of other albums for EmArcy Records featuring the brothers Stanley and Tommy Turrentine.[11]

In 1955, he played drums for vocalist Dinah Washington at several live appearances and recordings. He appeared with Washington at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958, which was filmed, and at the 1954 live studio audience recording of Dinah Jams, considered to be one of the best and most overlooked vocal jazz albums of its genre.[12]

1960s–1970s

In 1960 he composed and recorded the album We Insist! (subtitled Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite), with vocals by his then-wife Abbey Lincoln and lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. In 1962, he recorded the album Money Jungle, a collaboration with Mingus and Duke Ellington. This is generally regarded as one of the finest trio albums ever recorded.[13]

During the 1970s, Roach formed M'Boom, a percussion orchestra. Each member composed for the ensemble and performed on multiple percussion instruments. Personnel included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.[14]

Long involved in jazz education, in 1972 Roach was recruited to the faculty of the University of Massachusetts Amherst by Chancellor Randolph Bromery.[15] He taught at the university until the mid-1990s.[16]

1980s–1990s

In the early 1980s, Roach began presenting solo concerts, demonstrating that multiple percussion instruments performed by one player could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these solo concerts, and a solo record was released by the Japanese jazz label Baystate. One of his solo concerts is available on a video, which also includes footage of a recording date for Chattahoochee Red, featuring his working quartet, Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater, and Calvin Hill.

Roach also embarked on a series of duet recordings. Departing from the style he was best known for, most of the music on these recordings is free improvisation, created with Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, and Abdullah Ibrahim. Roach created duets with other performers, including: a recorded duet with oration of the "I Have a Dream" speech by Martin Luther King Jr.; a duet with video artist Kit Fitzgerald, who improvised video imagery while Roach created the music; a duet with his lifelong friend and associate Gillespie; and a duet concert recording with Mal Waldron.

During the 1980s Roach also wrote music for theater, including plays by Sam Shepard. He was composer and musical director for a festival of Shepard plays, called "ShepardSets", at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in 1984. The festival included productions of Back Bog Beast Bait, Angel City, and Suicide in B Flat.[17] In 1985, George Ferencz directed "Max Roach Live at La MaMa: A Multimedia Collaboration".[18]

Roach found new contexts for performance, creating unique musical ensembles. One of these groups was "The Double Quartet", featuring his regular performing quartet with the same personnel as above, except Tyrone Brown replaced Hill. This quartet joined "The Uptown String Quartet", led by his daughter Maxine Roach and featuring Diane Monroe, Lesa Terry, and Eileen Folson.

Another ensemble was the "So What Brass Quintet", a group comprising five brass instrumentalists and Roach, with no chordal instrument and no bass player. Much of the performance consisted of drums and horn duets. The ensemble consisted of two trumpets, trombone, French horn, and tuba. Personnel included Cecil Bridgewater, Frank Gordon, Eddie Henderson, Rod McGaha, Steve Turre, Delfeayo Marsalis, Robert Stewart, Tony Underwood, Marshall Sealy, Mark Taylor, and Dennis Jeter.

Not content to expand on the music he was already known for, Roach spent the 1980s and 1990s finding new forms of musical expression and performance. He performed a concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He wrote for and performed with the Walter White gospel choir and the John Motley Singers. He also performed with dance companies, including the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the Dianne McIntyre Dance Company, and the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. He surprised his fans by performing in a hip hop concert featuring Fab Five Freddy and the New York Break Dancers. Roach expressed the insight that there was a strong kinship between the work of these young black artists and the art he had pursued all his life.[2]

Though Roach played with many types of ensembles, he always continued to play jazz. He performed with the Beijing Trio, with pianist Jon Jang and erhu player Jeibing Chen. His final recording, Friendship, was with trumpeter Clark Terry. The two were longtime friends and collaborators in duet and quartet. Roach's final performance was at the 50th anniversary celebration of the original Massey Hall concert, with Roach performing solo on the hi-hat.[19]

In 1994, Roach appeared on Rush drummer Neil Peart's Burning For Buddy, performing "The Drum Also Waltzes" Parts 1 and 2 on Volume 1 of the 2-volume tribute album during the 1994 All-Star recording sessions.[20]

Death

In the early 2000s, Roach became less active due to the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications.

Roach died of complications related to Alzheimer's and dementia in Manhattan in the early morning of August 16, 2007.[21] He was survived by five children: sons Daryl and Raoul, and daughters Maxine, Ayo, and Dara. More than 1,900 people attended his funeral at Riverside Church on August 24, 2007. He was interred at the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

In a funeral tribute to Roach, then-Lieutenant Governor of New York David Paterson compared the musician's courage to that of Paul Robeson, Harriet Tubman, and Malcolm X, saying that "No one ever wrote a bad thing about Max Roach's music or his aura until 1960, when he and Charlie Mingus protested the practices of the Newport Jazz Festival."[22]

Personal life

Two children, a son and daughter, were born from Roach's first marriage with Mildred Roach in 1949. In 1956, he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and fathered another son. During the period 1962–1970, Roach was married to singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of his albums. In 1971, twin daughters were born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach.

He had four grandchildren: Kyle Maxwell Roach, Kadar Elijah Roach, Maxe Samiko Hinds, and Skye Sophia Sheffield.

His godson is artist, filmmaker and hip-hop pioneer, Fab Five Freddy.[23]

Roach identified himself as a Muslim in an early 1970s interview with Art Taylor.[24]

Style

Roach started as a traditional grip player but used matched grip as well as his career progressed.[25]

Roach's most significant innovations came in the 1940s, when he and Kenny Clarke devised a new concept of musical time. By playing the beat-by-beat pulse of standard 4/4 time on the ride cymbal instead of on the thudding bass drum, Roach and Clarke developed a flexible, flowing rhythmic pattern that allowed soloists to play freely. This also created space for the drummer to insert dramatic accents on the snare drum, crash cymbal, and other components of the trap set.

By matching his rhythmic attack with a tune's melody, Roach brought a newfound subtlety of expression to the drums. He often shifted the dynamic emphasis from one part of his drum kit to another within a single phrase, creating a sense of tonal color and rhythmic surprise.[1] Roach said of the drummer's unique positioning, "In no other society do they have one person play with all four limbs."[26]

While this is common today, when Clarke and Roach introduced the concept in the 1940s it was revolutionary. "When Max Roach's first records with Charlie Parker were released by Savoy in 1945", jazz historian Burt Korall wrote in the Oxford Companion to Jazz, "drummers experienced awe and puzzlement and even fear." One of those drummers, Stan Levey, summed up Roach's importance: "I came to realize that, because of him, drumming no longer was just time, it was music."[1]

In 1966, with his album Drums Unlimited (which includes several tracks that are entirely drum solos) he demonstrated that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, and rhythmically cohesive phrases. Roach described his approach to music as "the creation of organized sound."[14] Roach's style has been a big influence on several jazz and rock drummers, most notably Joe Morello,[27] Tony Williams[28] Peter Erskine,[29] Billy Cobham,[30] Ginger Baker,[31] and Mitch Mitchell.[32] The track "The Drum Also Waltzes" was often quoted by John Bonham in his Moby Dick drum solo and revisited by other drummers, including Neil Peart and Steve Smith.[33][34] Bill Bruford performed a cover of the track on the 1985 album Flags.

Honors

Roach was given a MacArthur Genius Grant in 1988 and cited as a Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France in 1989.[35] He was twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, was elected to the International Percussive Art Society's Hall of Fame and the DownBeat Hall of Fame, and was awarded Harvard Jazz Master. He was celebrated by Aaron Davis Hall and was given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by Medgar Evers College, CUNY, the University of Bologna, and Columbia University, in addition to his alma mater, the Manhattan School of Music.[36]

In 1986, the London borough of Lambeth named a park in Brixton after Roach.[37][38] Roach was able to officially open the park when he visited London in March of that year by invitation from the Greater London Council.[39] During that trip, he performed at a concert at the Royal Albert Hall along with Ghanaian master drummer Ghanaba and others.[40][41]

Roach spent his later years living at the Mill Basin Sunrise assisted living home in Brooklyn, and was honored with a proclamation honoring his musical achievements by Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz.[42] Roach was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.[43]

Discography

As leader/co-leader

|

Co-leader with Clifford Brown

Co-leader with M'Boom

|

Compilations

- Alone Together: The Best of the Mercury Years (Verve, 1995) – recorded in 1954–60

As sideman

With Chet Baker

- Witch Doctor (Contemporary, 1985) – recorded in 1953

With Don Byas

- Savoy Jam Party (1946)

With Jimmy Cleveland

- Introducing Jimmy Cleveland and His All Stars (EmArcy, 1955)

With Al Cohn

- Al Cohn's Tones (Savoy, 1956) – recorded in 1953

With Miles Davis

- Birth of the Cool (Capitol, 1949)

- Conception (Prestige, 1951)

With John Dennis

- New Piano Expressions (1955)

With Kenny Dorham

- Jazz Contrasts (Riverside, 1957)

With Billy Eckstine

- The Metronome All Stars (MGM, 1953)[10 inch]

With Duke Ellington

- Paris Blues (United Artists, 1961)

- Money Jungle (United Artists, 1962) also with Charles Mingus

With Maynard Ferguson

- Jam Session featuring Maynard Ferguson (EmArcy, 1954)

With Stan Getz

- Opus BeBop (Savoy, 1957) – Compilation recorded in 1946-47

- Stan Getz and the Cool Sounds (Verve, 1957) – recorded in 1953-55

With Dizzy Gillespie

- Diz and Getz (Verve, 1953) – with Stan Getz

- The Bop Session (Sonet, 1975) with Sonny Stitt, John Lewis, Hank Jones and Percy Heath

With Benny Golson

- The Modern Touch (Riverside, 1957)

With Johnny Griffin

- Introducing Johnny Griffin (Blue Note, 1956)

With Slide Hampton

- Drum Suite (Epic, 1962)

With Coleman Hawkins

- Rainbow Mist (Delmark, 1992) – compilation of Apollo recordings in 1944

- Coleman Hawkins and His All Stars (1944)

- Body and Soul (1946)

With Joe Holiday

- Mambo Jazz (Original Jazz Classics, 1991) – recorded in 1951-54

With J.J. Johnson

- Mad Be Bop (Savoy, 1978)[2LP] – recorded in 1946-54

- First Place (Columbia, 1957)

With Thad Jones

- The Magnificent Thad Jones (Blue Note, 1956)

With Abbey Lincoln

- That's Him! (Riverside, 1957)

- Straight Ahead (Riverside, 1961)

With Booker Little

- Out Front (Candid, 1961)

With Howard McGhee

- Howard McGhee All Stars (Blue Note, 1952)[10 inch]

With Gil Mellé

- Gil Mellé Quintet/Sextet (Blue Note, 1953)

With Charles Mingus

- Mingus at the Bohemia (Debut, 1955); "Percussion Discussion" only

- The Charles Mingus Quintet & Max Roach (Debut, 1955)

With Thelonious Monk

- Genius of Modern Music: Volume 2 (Blue Note, 1952)

- Brilliant Corners (Riverside, 1956)

With Herbie Nichols

- Herbie Nichols Trio (Blue Note, 1955)

With Charlie Parker

- Town Hall, New York, June 22, 1945 (1945) – with Dizzy Gillespie

- The Complete Savoy Studio Recordings (1945–48)

- Lullaby in Rhythm (1947)

- Charlie Parker's Savoy and Dial sessions/Complete Charlie Parker on Dial/Charlie Parker on Dial (Dial, 1945–48)

- The Band that Never Was (1948)

- Bird on 52nd Street (1948)

- Bird at the Roost (1948)

- Charlie Parker Complete Sessions on Verve (Verve, 1949–53)

- Charlie Parker in France (1949)

- Live at Rockland Palace (1952)

- Yardbird: DC–53 (1953)

- Big Band (Clef, 1954)

With Oscar Pettiford

- Oscar Pettiford Sextet (Vogue, 1954)

With Bud Powell

- The Bud Powell Trip (1947)

- The Amazing Bud Powell (Blue Note, 1951)

With Sonny Rollins

- Work Time (Prestige, 1955)

- Sonny Rollins Plus 4 (Prestige, 1956)

- Tour de Force (Prestige, 1956)

- Rollins Plays for Bird (Prestige, 1956)

- Saxophone Colossus (Prestige, 1956)

- Freedom Suite (Riverside, 1958)

- Stuttgart 1963 Concert (1963)

With George Russell

- New York, N.Y. (1959)

With A. K. Salim

- Pretty for the People (Savoy, 1957)

With Hazel Scott

- Relaxed Piano Moods (1955)

With Sonny Stitt

- Sonny Stitt/Bud Powell/J. J. Johnson (Prestige, 1956)

With Stanley Turrentine

- Stan "The Man" Turrentine (Time, 1960 [1963])

With Tommy Turrentine

- Tommy Turrentine (1960)

With George Wallington

- The George Wallington Trip and Septet (1951)

With Dinah Washington

- Dinah Jams (EmArcy, 1954)

With Randy Weston

- Uhuru Afrika (Roulette, 1960)

With Joe Wilder

- The Music of George Gershwin: I Sing of Thee (1956)

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/max-roach

Max Roach

Photo by Michael Wilderman. jazzvisionsphotos.com

Bio

Max Roach was one of the two leading drummers of the bebop era (along with Kenny Clarke) and was one of the leading musicians, composers, and bandleaders in jazz since the 1940s. His often biting political commentary and strong intellect, not to mention his rhythmic innovations, kept him at the vanguard of jazz for more than 50 years.

Roach grew up in a household where gospel music was quite prominent. His mother was a gospel singer and he began drumming in a gospel ensemble at age 10. Roach's formal study of music took him to the Manhattan School of Music. In 1942, he became house drummer at Monroe's Uptown House, enabling him to play and interact with some of the giants of the bebop era, such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Bud Powell. Roach would later record with Parker, Gillespie, Powell, and bassist Charles Mingus at the historic Massey Hall concert in 1953.

Throughout the 1940s, Roach continued to branch out in his playing, drumming with Benny Carter, Stan Getz, Allen Eager, and Miles Davis. In 1952, he and Mingus collaborated to create their own record label, Debut Records. In 1954, Roach began a short-lived but crucial band with incendiary trumpeter Clifford Brown. This historic band, which ended abruptly with Brown's tragic death in 1956, also included saxophonists Harold Land and Sonny Rollins.

In the late 1950s, Roach began adding political commentary to his recordings, starting with Deeds Not Words, but coming into sharper focus with We Insist! Freedom Now Suite in 1960, on which he collaborated with singer-lyricist Oscar Brown, Jr. From then on he became an eloquent spokesman in the area of racial and political justice. Roach continued to experiment with his sound, eschewing the use of the piano or other chording instruments in his bands for the most part from the late 1960s on. His thirst for experimentation led to collaborations with seemingly disparate artists, including duets with saxophonist Anthony Braxton and pianist Cecil Taylor, as well as partnerships with pianist Abdullah Ibrahim and saxophonist Archie Shepp.

As a drum soloist he had few peers in terms of innovations, stemming from his deeply personal sound and approach. His proclivities in the area of multiethnic percussion flowered with his intermittent percussion ensemble M'Boom, founded in 1970. A broad-based percussionist who was a pioneer in establishing a fixed pulse on the ride cymbal instead of the bass drum, Roach also collaborated with voice, string, and brass ensembles, lectured on college campuses extensively, and composed music for dance, theater, film, and television.

Selected Discography

Clifford Brown and Max Roach, At Basin Steet, EmArcy, 1956

We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, Candid, 1960

M'Boom, Columbia, 1979

To The Max, Rhino, 1990-91

Explorations to the Mth Degree, Slam, 1994

Related Audio:

Anthony Braxton on recording with his idol Max Roach:

https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/XM-288.mp3

Transcript:

RUFFIN: NOW, A JAZZ MOMENT

Birth under

NEA JAZZ MASTER ANTHONY BRAXTON TALKS ABOUT RECORDING WITH ONE OF HIS IDOLS, DRUMMER MAX ROACH.

ANTHONY BRAXTON: I remember everything about it. And first I was surprised to know that the great man had chosen me. I didn't choose him. I would never ever have even suggested that I walk across the street while he was playing. I worshipped the ground he walked on. And of course my answer was, "Yes, yes, yes, sir."

And so we walked into the studio. He had nothin' to say to me. And I said, "Uh, Mr. Roach, good afternoon, sir. Is, uh, everything okay?" Nothin' to say. He turned to the engineer. He says, "Turn on the tape. Let's play."

Birth up and hot

Everything was in one swoop. There was no breaks. And then after the recording was finished he said, "Anthony, how are you?" And that’ when our relationship started. It was actually very beautiful. The old master checked me out to see if I was on a level where it was worth it. And then after the recording we became friends. I was the luckiest guy on the planet.

THIS JAZZ MOMENT WITH ALTO SAXOPHONIST ANTHONY BRAXTON WAS PRODUCED BY THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS

Excerpt of "Birth" composed and performed by Anthony Braxton and Max Roach from the album, Birth and Rebirth, used courtesy of CamJazz / Black Saint and used by permission of Kobalt Music Publishing [BMI].

"The music in this album is a result of our belief in a continuum that links the present with the past. Our spontaneous improvisations are true to those well defined principles basic to African American culture. Thank you for listening." --Max Roach & Anthony Braxton - 'Birth And Rebirth', Black Saint records (Italy) 1978

https://www.pas.org/about/hall-of-fame/max-roach

Max Roach

by Rick Mattingly

As the big band era of the 1930s and early '40s gave way to the bebop

era of the late 1940s and '50s, Max Roach became the most important bop

drummer through his work with bebop founders Charlie "Bird" Parker and

Dizzy Gillespie. Roach was at the forefront of a new drumming style in

which the ride cymbal was the focal element of the drumkit, and Roach's

ability to play extremely fast ride patterns set a new standard for

drumming excellence.

Born in North Carolina but raised in Brooklyn, Maxwell Roach began

playing piano at age eight and started playing drums at age 10. "Jo

Jones was the first drummer I heard who played broken rhythms," Roach

said. "I listened to him over and over again. But a lot of people

inspired me. Chick Webb was a tremendous soloist. There was Sonny Greer,

Cozy Cole, and Sid Catlett, who incorporated this hi-hat and ride

cymbal style. Then I heard Kenny Clarke. He exemplified personality and

did more with the instrument. It affected me."

After graduating from high school, Roach became the house drummer at

Monroe's Uptown House in 1942, and he participated in the jam sessions

there and at various 52nd Street clubs with Parker and Gillespie that

led to the development of bebop. He recorded with Coleman Hawkins in

1943, and the following year he was a member of a bop band led by

Gillespie and Oscar Pettiford, and then a band led by Gillespie and Budd

Johnson. Roach then played with Benny Carter's big band before joining

the Gillespie-Parker quintet and also playing in Gillespie's big band.

He played with Parker's quintet from 1947–49 and appeared on many of

Parker's most important recordings.

Roach also recorded with Miles Davis in 1949 for the album Birth of the

Cool. The hi-hat and ride cymbal can be heard very cleanly on that

album, and one can hear Roach using the ride cymbal in the bop style,

but still sometimes riding on partially open hi-hats in the swing style.

But it was recordings such as this that gave rise to the myth that bop

drummers were not using the bass drum as a timekeeping element,

relegating it only to occasional accents. "That is not what was going

on," Roach insisted in a interview published in the book The Drummer's

Time. "We played the bass drum, but the engineers would cover it up

because it would cause distortion due to the technology at the time.

There were never any mic's near our feet; they would have one mic' above

the drumset, and that was all.

"It was funny to me that when I would hear a recording, I didn't hear

the bass drum, because in those days the bass drum was always prevalent.

You could not get a job unless the bandleader could hear that 4/4 on

the bass drum. I remember standing in front of Chick Webb's drumset. His

bass drum was so strong and constant I could hear it in my stomach:

BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM constantly. Then on 52nd Street, we learned how

to play the bass drum softly. It was always there, underneath the bass

fiddle.

"But you never heard it on the recordings," Roach said. "I've heard

people say that, historically, I introduced the technique of not playing

the bass drum and concentrating on the ride cymbal, which was not the

case. You didn't carry a bass drum around on the subways of New

York—like we used to—and then not use it."

One of the most famous of all the bop recordings is Jazz at Massey Hall,

which was recorded in 1953 and features Parker, Gillespie, Roach, Bud

Powell, and Charles Mingus. Tunes such as "Salt Peanuts" reveal Roach's

finesse with extremely fast tempos. "We'd have jam sessions at Minton's

where the tenor players were long-winded," Roach explained. "Don Byas

would play 20 minutes on ‘Cherokee,' and then Johnny Griffin would play

another 20 minutes, and then somebody else would play. And then they'd

turn to you and say, ‘You got it.' They'd wear you out and then give you

a solo, right? So I had to learn to not give it all up right away so I

would have something left an hour later. Those sessions were

unbelievable, but it makes you strong and teaches you how all four limbs

have the responsibility to create the illusion that you're playing

super fast."

In 1954, Roach formed a band with trumpet player Clifford Brown, and for

the next two years it was one of the hottest groups on the scene,

featuring pianist Richie Powell and saxophonist Sonny Rollins. The group

was cut short by Powell and Brown's untimely deaths in an automobile

accident in 1956.

On the Brown/Roach recording of "I'll Remember April," the band plays in

a style originated by Dizzy Gillespie on "Night In Tunisia" in which

the rhythm changes back and forth between Latin and swing feels. But

whereas many jazz drummers base their Latin-flavored playing around a

cymbal-bell ride pattern, Roach played the Latin sections of "I'll

Remember April" entirely on tom-toms. "That had a lot to do with the

Caribbean thing," Roach explained, "because I grew up in Brooklyn with

people from Jamaica and Trinidad and places like that, so I heard that

music all the time. And then when the Cubans came to New York, they

would have four or five percussionists playing congas and timbales. I

was really fascinated by that."

Roach became politically active in the 1960s, and his album We Insist!

Freedom Now Suite reflected the tension of the era. "That was a period

of total protest," Roach said, "and I was heavily involved in the civil

rights movement. I've never believed in art just for the sake of art. It

is entertainment, of course, and dancing is also part of it, but it can

also be for enlightenment."

Roach also pioneered solo drum compositions, such as "The Drum Also

Waltzes" from his 1966 album Drums Unlimited. "When I was going to the

Manhattan School of Music," Roach said, "I was able to see Ravi Shankar

when he came to town around 1944. This marvelous tabla player he brought

with him, Chatur Lal, did 15 minutes by himself on those tablas, and it

was the most fascinating and musical thing I'd ever heard. That gave me

the inspiration to deal with drums by themselves. I would also watch

Art Tatum play piano by himself on 52nd Street and wonder if it were

possible to do that with the drumset. And when Segovia or Pablo Casals

would come to New York, they would play by themselves in a huge concert

hall and just mesmerize an audience. I knew there had to be some way to

do that with the percussion instrument.

"My first solo piece was called ‘Drum Conversation,' and people would

ask me, ‘Where are the chords? Where's the melody?' And I would say,

‘It's about design. It isn't about melody and harmony. It's about

periods and question marks. Think of it as constructing a building with

sound. It's architecture.'"

Considering Roach's penchant for playing solo drum compositions, it was

surprising to some that he never used more than a basic five-piece kit,

which he often referred to as the "multiple percussion instrument."

"I don't need to have a lot of drums around me," Roach said. "A

percussion ensemble has concert toms, the snare choir from piccolo to

tenor, and the whole array of instruments. But the drumset itself is

just that five-piece kit.

"The drumset is the freshest instrument in the world of percussion

because the player has to use all four limbs. With all the other

percussion instruments, we just use our hands. But the drumset uses all

the technique that has been developed for playing drums with the hands,

and having your feet in there adds other dimensions of technique. The

variety on that set is amazing. It has a lot to do with taking the least

and making the most of it."

As an extension of his solo drum compositions, Roach started the first

jazz percussion ensemble, M'Boom. "Musicians were so oriented that music

was this holy triangle of melody, harmony, and rhythm," Roach said. "If

you didn't have this perfect balance, you really weren't dealing with

organized music. But people forgot that there were percussion ensembles

in Africa and Europe, as well as groups like the Kodo drummers of Japan.

The drumset doing solos was new to us here, but it wasn't new to the

rest of the world.

"So M'Boom grew out of my still trying to justify what we were about as

percussionists. I decided we were going to be the front line and

everything. The first thing was, I wanted everybody to be well versed in

the trap set. But I also wanted them to be composers, because I knew

that if I got a group of people together like that, eventually we could

deal with mallets and timpani and everything."

In his later years, Roach led his own groups and also performed with a

wide variety of artists, from avant-garde musicians such as Cecil Taylor

and Anthony Braxton to classical string quartets and the Japanese taiko

group Kodo. Roach's Double Quartet featured his regular jazz quartet

with the Uptown String Quartet, which was led by his daughter, Maxine.

Roach also taught at the Lennox (Mass.) School of Jazz in the late 1950s

and during the 1970s and '80s at the University of Massachusetts at

Amherst. He was awarded two honorary degrees and in 1988 received the

first MacArthur Fellowship ever awarded to a jazz musician.

Roach died on Aug. 16, 2007 after a lengthy illness.

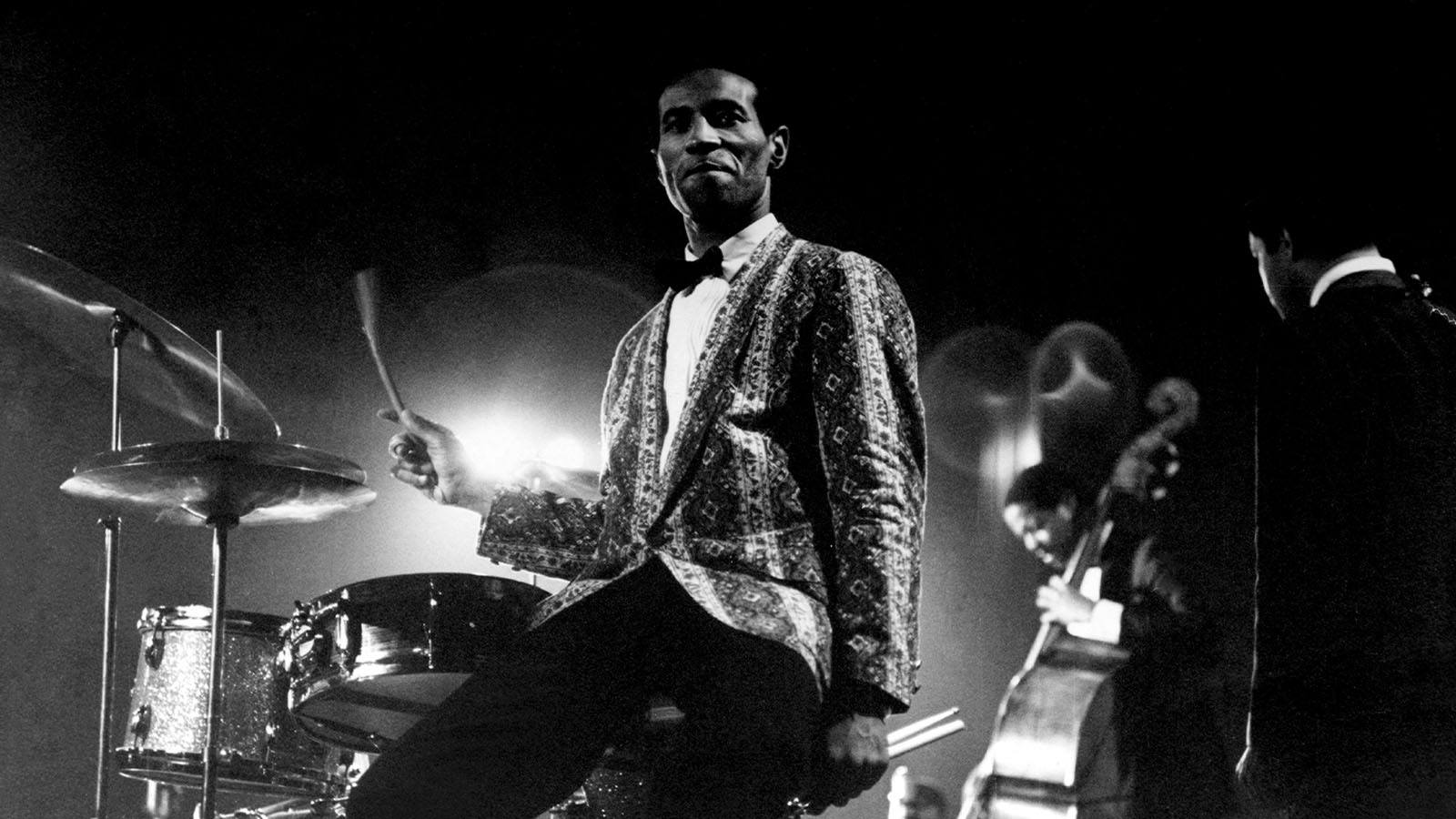

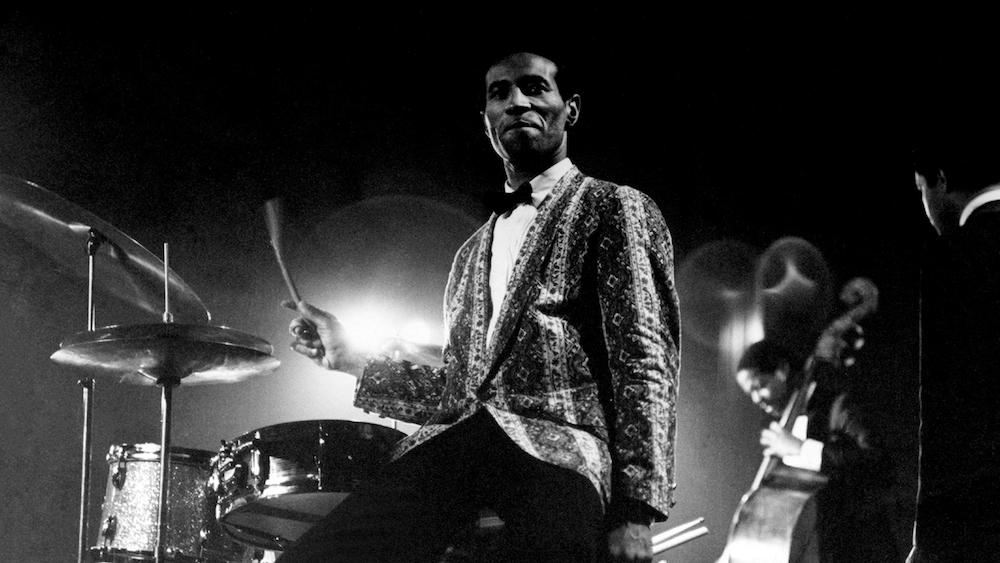

Max Roach | Triptych 1964

Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 – August 16, 2007) was an American jazz drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered alongside the most important drummers in history. He worked with many famous jazz musicians, including Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Abbey Lincoln, Dinah Washington, Charles Mingus, Billy Eckstine, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, and Booker Little. He was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1992.

Roach also co-led a pioneering quintet along with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the percussion ensemble M'Boom. He made numerous musical statements relating to the civil rights movement.

Max Roach was born to Alphonse and Cressie Roach in the Township of Newland, Pasquotank County, North Carolina, which borders the southern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp. The Township of Newland is sometimes mistaken for Newland Town in Avery County, North Carolina. Although his birth certificate lists his date of birth as January 10, 1924, Roach has been quoted by Phil Schaap, saying that his family believed he was actually born on January 8, 1925.

Roach's family moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, when he was four years old. He grew up in a musical home with his gospel singer mother. He started to play bugle in parades at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands.

In 1942, as an 18-year-old recently graduated from Boys High School, he was called to fill in for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra performing at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan. He starting going to the jazz clubs on 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom, where he played with schoolmate Cecil Payne. His first professional recording took place in December 1943, backing Coleman Hawkins.

He was one of the first drummers, along with Kenny Clarke, to play in the bebop style. Roach performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis. He played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy Records November 1945 session, which marked a turning point in recorded jazz. His early brush work with Powell's trio, especially at fast tempos, has been highly praised.

Roach nurtured an interest in and respect for Afro-Caribbean music and traveled to Haiti in the late 1940s to study with the traditional drummer Ti Roro.

--

Abbey Lincoln - Vocal

Clifford Jordan - Sax

Max Roach With Abbey Lincoln - Triptych (PrayerProtest Peace) 1964

http://www.biography.com/people/max-roach-9459691#evolving-career

Drummer, Educator, Civil Rights Activist, Songwriter (1924–2007)

Birth Date

January 10, 1924

Death Date

August 16, 2007

Education

Manhattan School of Music

Synopsis

Early Life

Jazz Success

Evolving Career

Later Years

A pioneer of the bebop style, drummer Max Roach spent decades creating innovative jazz.

“You can't write the same book twice. Though I've been in historic musical situations, I can't go back and do that again. And though I run into artistic crises, they keep my life interesting.”—Max Roach

Max Roach was born on January 10, 1924, in New Land, North Carolina. He was raised in Brooklyn and studied at the Manhattan School of Music. One of the great jazz drummers and a pioneer of bebop, he worked with Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, Charlie Parker and Clifford Brown. Roach was also a composer and a professor of music at the University of Massachusetts. He died in New York City in 2007.

Early Life

Maxwell Lemuel Roach, generally known as Max Roach, was born on January 10, 1924, in New Land, North Carolina. He was raised in Brooklyn and played in gospel groups as a child. Though he started on the piano, Roach found his instrument when he began playing the drums at age 10.

Jazz Success

Growing up in New York City exposed Roach to an exuberant jazz scene. In 1940, 16-year-old Roach filled in with Duke Ellington's orchestra. During the 1940s, he played with jazz greats like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Benny Carter and Stan Getz. Roach further developed his skills by studying at the Manhattan School of Music.

Roach joined with Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and others to help bebop—a form of jazz that featured more intense rhythms and sophisticated musicality—come into being. He soon gained a reputation as a virtuoso bebop drummer, one who could enhance a song with his musical choices. From 1947 to 1949, Roach was part of Parker's trailblazing quintet.

Roach's drumming could be heard on many recordings, starting with his debut with Hawkins in 1943. His other albums include Woody 'n' You (1944)—considered one of the first bebop records—and Davis's Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949-50. In 1952, Roach co-founded Debut Records with Charles Mingus. The label released a recording of a seminal jazz concert held at Massey Hall in 1953, where Roach performed with Mingus, Parker, Gillespie and Bud Powell.

In 1954, Roach and Clifford Brown formed a quintet that became one of the most highly regarded groups in modern jazz. Unfortunately, their collaboration ended when Brown and another member of the group were killed in a 1956 car accident. The loss was a depressing blow for Roach; he began drinking heavily, but eventually sought professional help to regain his footing. He also continued creating music, taking on projects with Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins.

Evolving Career

With We Insist! Freedom Now Suite (1960), Roach used music to address the need for racial equality. Despite the risks that taking an outspoken political stance posed to his career, Roach continued to support the Civil Rights Movement. He later created a drum accompaniment for Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

In 1972, Roach was named as a professor of music at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. His career accomplishments were further recognized when Roach was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame in 1982, and when he was selected as a 1984 Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1988, Roach received a MacArthur Foundation "genius grant," the first given to a jazz musician.

Roach's adaptability and inventiveness spurred him to work on an increasingly diverse list of projects. In 1970, he founded M'Boom, an all-percussion group. Roach also composed for choreographer Alvin Ailey and created music for plays written by Sam Shepard (his work with Shepard garnered Roach an Obie Award). His other collaborators include hip-hop artists Fab Five Freddy, writer Toni Morrison (Roach provided musical accompaniment at her spoken word concerts), Japanese taiko drummers and avant-garde instrumentalists Cecil Taylor and Anthony Braxton.

Later Years

Roach gave his last concert in 2000 and made his final recording in 2002.He suffered from a neurological disorder for an extended period before his death in New York City on August 16, 2007, at the age of 83. All three of Roach's marriages ended in divorce, but he was survived by two sons and three daughters.

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/16/arts/music/16cnd-roach.html

Max Roach, a Founder of Modern Jazz, Dies at 83

Max Roach, a founder of modern jazz who rewrote the rules of drumming in the 1940’s and spent the rest of his career breaking musical barriers and defying listeners’ expectations, died early today in Manhattan. He was 83.

His death was announced today by a spokesman for Blue Note records, on which he frequently appeared. No cause was given. Mr. Roach had been known to be ill for several years.

As a young man, Mr. Roach, a percussion virtuoso capable of playing at the most brutal tempos with subtlety as well as power, was among a small circle of adventurous musicians who brought about wholesale changes in jazz. He remained adventurous to the end.

Over the years he challenged both his audiences and himself by working not just with standard jazz instrumentation, and not just in traditional jazz venues, but in a wide variety of contexts, some of them well beyond the confines of jazz as that word is generally understood.

He led a “double quartet” consisting of his working group of trumpet, saxophone, bass and drums plus a string quartet. He led an ensemble consisting entirely of percussionists. He dueted with uncompromising avant-gardists like the pianist Cecil Taylor and the saxophonist Anthony Braxton. He performed unaccompanied. He wrote music for plays by Sam Shepard and dance pieces by Alvin Ailey. He collaborated with video artists, gospel choirs and hip-hop performers.

Mr. Roach explained his philosophy to The New York Times in 1990: “You can’t write the same book twice. Though I’ve been in historic musical situations, I can’t go back and do that again. And though I run into artistic crises, they keep my life interesting.”

He found himself in historic situations from the beginning of his career. He was still in his teens when he played drums with the alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, a pioneer of modern jazz, at a Harlem after-hours club in 1942. Within a few years, Mr. Roach was himself recognized as a pioneer in the development of the sophisticated new form of jazz that came to be known as bebop.

He was not the first drummer to play bebop — Kenny Clarke, 10 years his senior, is generally credited with that distinction — but he quickly established himself as both the most imaginative percussionist in modern jazz and the most influential.

In Mr. Roach’s hands, the drum kit became much more than a means of keeping time. He saw himself as a full-fledged member of the front line, not simply as a supporting player.

Layering rhythms on top of rhythms, he paid as much attention to a song’s melody as to its beat. He developed, as the jazz critic Burt Korall put it, “a highly responsive, contrapuntal style,” engaging his fellow musicians in an open-ended conversation while maintaining a rock-solid pulse. His approach “initially mystified and thoroughly challenged other drummers,” Mr. Korall wrote, but quickly earned the respect of his peers and established a new standard for the instrument.

Mr. Roach was an innovator in other ways. In the late 1950s, he led a group that was among the first in jazz to regularly perform pieces in waltz time and other unusual meters in addition to the conventional 4/4. In the early 1960s, he was among the first to use jazz to address racial and political issues, with works like the album-length “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite.”

In 1972, he became one of the first jazz musicians to teach full time at the college level when he was hired as a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. And in 1988, he became the first jazz musician to receive a so-called genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation.

Maxwell Roach was born on Jan. 10, 1924, in the small town of New Land, N.C., and grew up in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. He began studying piano at a neighborhood Baptist church when he was 8 and took up the drums a few years later.

Even before he graduated from Boys High School in 1942, savvy New York jazz musicians knew his name. As a teenager he worked briefly with Duke Ellington’s orchestra at the Paramount Theater and with Charlie Parker at Monroe’s Uptown House in Harlem, where he took part in jam sessions that helped lay the groundwork for bebop. By the middle 1940’s, he had become a ubiquitous presence on the New York jazz scene, working in the 52nd Street nightclubs with Parker, the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and other leading modernists. Within a few years he had become equally ubiquitous on record, participating in such seminal recordings as Miles Davis’s “Birth of the Cool” sessions in 1949 and 1950.

He also found time to study composition at the Manhattan School of Music. He had planned to major in percussion, he later recalled in an interview, but changed his mind after a teacher told him his technique was incorrect. “The way he wanted me to play would have been fine if I’d been after a career in a symphony orchestra,” he said, “but it wouldn’t have worked on 52nd Street.”

Mr. Roach made the transition from sideman to leader in 1954, when he and the young trumpet virtuoso Clifford Brown formed a quintet. That group, which specialized in a muscular and stripped-down version of bebop that came to be called hard bop, took the jazz world by storm. But it was short-lived.

In June 1956, at the height of the Brown-Roach quintet’s success, Brown was killed in an automobile accident, along with Richie Powell, the group’s pianist, and Powell’s wife. The sudden loss of his friend and co-leader, Mr. Roach later recalled, plunged him into depression and heavy drinking from which it took him years to emerge.

Nonetheless, he kept working. He honored his existing nightclub bookings with the two surviving members of his group, the saxophonist Sonny Rollins and the bassist George Morrow, before briefly taking time off and putting together a new quartet. By the end of the 50’s, seemingly recovered from his depression, he was recording prolifically, mostly as a leader but occasionally as a sideman with Mr. Rollins and others.

The personnel of Mr. Roach’s working group changed frequently over the next decade, but the level of artistry and innovation remained high. His sidemen included such important musicians as the saxophonists Eric Dolphy, Stanley Turrentine and George Coleman and the trumpet players Donald Byrd, Kenny Dorham and Booker Little. Few of his groups had a pianist, making for a distinctively open ensemble sound in which Mr. Roach’s drums were prominent.

Always among the most politically active of jazz musicians, Mr. Roach had helped the bassist Charles Mingus establish one of the first musician-run record companies, Debut, in 1952. Eight years later, the two organized a so-called rebel festival in Newport, R.I., to protest the Newport Jazz Festival’s treatment of performers. That same year, Mr. Roach collaborated with the lyricist Oscar Brown Jr. on “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite,” which played variations on the theme of black people’s struggle for equality in the United States and Africa.

The album, which featured vocals by Abbey Lincoln (Mr. Roach’s frequent collaborator and, from 1962 to 1970, his wife), received mixed reviews: many critics praised its ambition, but some attacked it as overly polemical. Mr. Roach was undeterred.

“I will never again play anything that does not have social significance,” he told Down Beat magazine after the album’s release. “We American jazz musicians of African descent have proved beyond all doubt that we’re master musicians of our instruments. Now what we have to do is employ our skill to tell the dramatic story of our people and what we’ve been through.”

“We Insist!” was not a commercial success, but it emboldened Mr. Roach to broaden his scope as a composer. Soon he was collaborating with choreographers, filmmakers and Off Broadway playwrights on projects, including a stage version of “We Insist!”

As his range of activities expanded, his career as a bandleader became less of a priority. At the same time, the market for his uncompromising brand of small-group jazz began to diminish. By the time he joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts in 1972, teaching had come to seem an increasingly attractive alternative to the demands of the musician’s life.

Joining the academy did not mean turning his back entirely on performing. In the early ‘70s, Mr. Roach joined with seven fellow drummers to form M’Boom, an ensemble that achieved tonal and coloristic variety through the use of xylophones, chimes, steel drums and other percussion instruments. Later in the decade he formed a new quartet, two of whose members — the saxophonist Odean Pope and the trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater — would perform and record with him off and on for more than two decades.

He also participated in a number of unusual experiments. He appeared in concert in 1983 with a rapper, two disc jockeys and a team of break dancers. A year later, he composed music for an Off Broadway production of three Sam Shepard plays, for which he won an Obie Award. In 1985, he took part in a multimedia collaboration with the video artist Kit Fitzgerald and the stage director George Ferencz.

Perhaps his most ambitious experiment in those years was the Max Roach Double Quartet, a combination of his quartet and the Uptown String Quartet. Jazz musicians had performed with string accompaniment before, but rarely if ever in a setting like this, where the string players were an equal part of the ensemble and were given the opportunity to improvise. Reviewing a Double Quartet album in The Times in 1985, Robert Palmer wrote, “For the first time in the history of jazz recording, strings swing as persuasively as any saxophonist or drummer.”

This endeavor had personal as well as musical significance for Mr. Roach: the Uptown String Quartet’s founder and viola player was his daughter Maxine. She survives him, as do two other daughters, Ayo and Dara, and two sons, Raoul and Darryl.

By the early ‘90s, Mr. Roach had reduced his teaching load and was again based in New York year-round, traveling to Amherst only for two residencies and a summer program each year. He was still touring with his quartet as recently as 2000, and he also remained active as a composer. In 2002 he wrote and performed the music for “How to Draw a Bunny,” a documentary about the artist Ray Johnson.

https://www.siff.net/festival/max-roach-the-drum-also-waltzes

Seattle International Film Festival

Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes

USA | 2023 | 82 min. | Sam Pollard, Ben Shapiro

The life and times of drummer Max Roach, who forever changed the landscape of America through his timeless music and lifetime of cultural activism, structured as a series of chapters that reflect his constant reinvention over his seven-decade career.

Since the bebop trailblazer died only in 2007, and since Samuel Pollard and Ben Shapiro have been working on this doc for over 35 years, there's a good amount of interview footage with drummer Max Roach himself—who disdains the term "jazz" as a nickname: "I'm an African American musician, and that's the kind of music that I play," he asserts early on. His musical life certainly branched out into more than jazz, embracing collaborations with gospel choirs, turntablists and rappers, even John Cage-style experimental percussion-only music. Roach's early career was spent hanging and performing with Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and the other demigods who made post-WWII New York City an unsurpassable jazz heaven. (The talking heads Pollard and Shapiro persuaded to participate are no less legendary, including Sonny Rollins, Quincy Jones, and Seattle's own Julian Priester.) Now, correlation is not necessarily causation, but not long after the hideous 1956 auto-accident death (at 25!) of his prime musical partner, trumpeter Clifford Brown, Roach met vocalist Abbey Lincoln and turned to outspoken social protest; partnering romantically as well as musically, the two became a sort of Black Power power couple. But then in 1972 Roach's career took its most shocking turn: academia. A faculty position at the University of Massachusetts, Roach explains, gave him both steady contact with the political concerns of the college generation and the resources to experiment. Copious family interviews and plenty of music (the filmmakers got the rights to what seems like Roach's entire discography) make this the definitive portrait of a musical and civil rights giant.

—Gavin Borchert

- Director: Sam Pollard, Ben Shapiro

- Principal Cast: Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, Quincy Jones, Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson, Abbey Lincoln, Harry Belafonte, Abdullah Ibrahim, Sonia Sanchez, Randy Weston, Jimmy Heath

- Country: USA

- Year: 2023

- Running Time: 82 min.

- Producer: Sam Pollard, Ben Shapiro

- Cinematographers: Ben Shapiro

- Editors: Russell Greene

- Music: Christopher North

- Website: Official Film Website

- Filmography: Pollard: Debut Feature Film; Shapiro: Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters (2012)

- Language: English

SXSW Film Review: Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes

The life and impact of the jazz drumming pioneer

by Marjorie Baumgarten

March 13, 2023

The Austin Chronicle

Decades in the making, Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes had its unveiling in a world premiere at SXSW.

Decades in the making, Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes had its unveiling in a world premiere at SXSW.

The documentary about the groundbreaking jazz drummer’s career is co-directed by Samuel Pollard and Ben Shapiro, who pooled their separate early efforts to mount a singular biopic about Roach and created this informative and powerful investigation into the musician’s accomplishments and legacy. The film is scheduled to air in the fall lineup of PBS’ American Masters series.

The film uses a vast array of archival footage and interviews to bring the recent past to life, often building sections into pulsating impressions that reflect its subject and an overall musicality. Jazz novices and well-steeped aficionados will all find this an edifying document that presents an overall biography of a significant life in music as well as a revealing portrait of what made the artist, a Black man who made his bones in Jim Crow America, tick.

It’s clear from the film’s opening seconds that the artist and his milieu will be inextricably entwined when we hear an on-camera white journalist asks Roach early in his career if his music can be used as a weapon. In reply, Roach, whose music demonstrably reflects the conflicted racial times, answered in the affirmative and went on to explain that even the term “jazz” is diminishing when a more proper descriptor might be something like “African American instrumental music.”

We may have Max Roach to thank for the often-dreaded drum solo in modern music. Roach lifted drumming from a mere beat-keeping anchor to an expressive instrumental showpiece and compositional tool. Playing with titans such as Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk in his early bebop years, Roach formed several combos of his own and developed a style that fostered free improvisation, and by the Seventies even created a percussion ensemble called M’Boom. In later decades, Roach composed for theatre and dance companies, as well as performing in a a hip-hop concert with his godson Fab 5 Freddy because he saw an intrinsic kinship between his jazz roots and the burgeoning hip-hop revolution. Roach also composed and recorded an album commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation called We Insist!: Max Roach’s Freedom Suite and music for a video of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream Speech.”

For their interviews, the filmmakers largely tap fellow musicians who knew Roach and could add personal knowledge and reminiscences rather than jazz historians and academics presenting facts. Interviewees include such musicians as Sonny Rollins, Harry Belafonte, Roach’s former wife Abbey Lincoln, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Randy Weston, Fab 5 Freddy, and poet Sonia Sanchez. Rollins perhaps sums up Roach’s lasting influence best when he describes Roach’s harmonious thrust: “He was always playing something that makes me want to play.”

Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes

24 Beats Per Second, World Premiere

Thu 16, 2:15pm, Alamo Lamar E

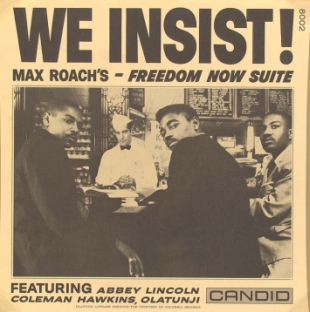

We Insist! Max Roach's - Freedom Now Suite (1960)

- On View

- Musical Crossroads Gallery

- Museum Maps

- Objects in this Location

- Exhibition

- Musical Crossroads

- Composed by

- Roach, Max, American, 1924 - 2007

- Written by

- Brown, Oscar, American, 1926 - 2005

- Recorded by

- Roach, Max, American, 1924 - 2007

- Lincoln, Abbey, American, 1930 - 2010

- Published by

- MiruMir Music Publishing, Russian, founded 2004

- Date

- 1960; re-released 2013

- Medium

- vinyl, cardboard

- Dimensions

- Diameter (.a, album): 11 13/16 in. (30 cm)

- H x W (.b, album jacket): 12 5/16 × 12 5/16 in. (31.3 × 31.3 cm)

- Description:

- An LP vinyl record (2015.103.3a) and jacket (2015.103.3b) of the "We Insist-Freedom Now Suite" performed by jazz percussionist, drummer and composer Max Roach.

- The LP vinyl record (2015.103.3a) has a black-and-white label, with white writing set against a black background. The type on the front of label reads: [So Far Out/ Side A/ OUT5001LP/ WE INSIST!/ MAX ROACH AND OSCAR BROWN, Jr.'s/ FREEDOM NOW SUITE/ DRIVA' MAN (5:10) FREEDOM DAY (6:02)/ TRIPTYCH: PRAYER. PROTEST, PEACE (7:58)]. The reverse side of the label reads: [So Far Out/ Side B/ OUT5001LP/ WE INSIST!/ MAX ROACH AND OSCAR BROWN, Jr.'s/ FREEDOM NOW SUITE/ ALL AFRICA (7:57)/ TEARS FOR JOHANNESBURG (9:36)].