AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION

(ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK

ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/08/abbey-lincoln-1930-2010-legendary.html

PHOTO: ABBEY LINCOLN (1930-2010)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/abbey-lincoln-mn0000487535/biography

Abbey Lincoln

(1930-2010)

Biography by Scott Yanow

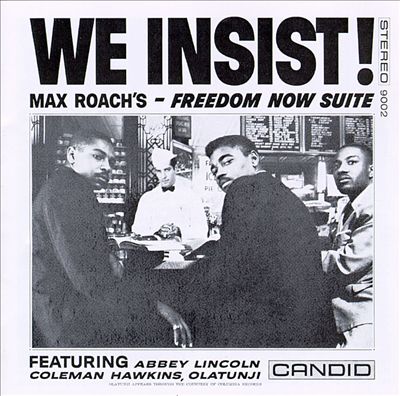

As with her hero Billie Holiday, Abbey Lincoln always meant the lyrics she sang. A dramatic performer whose interpretations were full of truth and insight, Lincoln actually began her career as a fairly lightweight supper-club singer. She went through several name changes (including Anna Marie, Gaby Lee, and Gaby Woolridge) before settling on Abbey Lincoln. She recorded with Benny Carter in 1956 and performed a number in the 1957 Hollywood film The Girl Can't Help It. Lincoln's first of three albums for Riverside (1957-1959) had Max Roach on drums and he was a major influence on her; she began to be choosy about the songs she sang and to give words the proper emotional intensity. Lincoln held her own on her early dates with such sidemen as Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins, Wynton Kelly, Curtis Fuller, and Benny Golson. She was quite memorable on Roach's Freedom Now Suite, showing some very uninhibited emotions. Lincoln's Candid date Straight Ahead (1961) had among its players Roach, Booker Little, Eric Dolphy, and Coleman Hawkins, and she made some important appearances on Roach's Impulse! album Percussion Bitter Suite.

Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach were married in 1962, an association that lasted until 1970. They worked together for a while but Lincoln (who found it harder to get work in jazz due to the political nature of some of her music) became involved in acting and did not record as a leader during 1962-1972. She finally recorded for Inner City in 1973 and gradually became more active in jazz. Her two Billie Holiday tribute albums for Enja (1987) showed listeners that the singer was still in her prime, and she recorded several excellent sets for Verve in the 1990s. In the following years, she released a handful of recordings including Over the Years in 2000; It's Me in 2003; and her final recording, Abbey Sings Abbey, in 2007. Abbey Lincoln died in New York City on August 14, 2010; she was 80 years old. Because she put so much thought into each of her recordings, it is not an understatement to say that every set she issued is well worth owning.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/abbey-lincoln/

Abbey Lincoln

"How can you have a career and never say anything? To experience it all and not say a word, you're supposed to stand up and speak your mind in the music. Some people like to hear some reality. I'm not trying to save or fix the world. I'm just singing about my experiences. My songs are observations."

For four decades Lincoln's life has been a constant transformation of experience, of awakenings into growth, of the communication of what she has witnessed. She has grown through many stages: a naive young lounge singer; a movie and jazz club sex kitten; a vocal African-American with a deepened cultural awareness; a sensitive actress contradicting cultural perceptions; an artistic and cultural exile; a poetic jazz sage. She has gone by many names, finding and then defining herself individually, culturally, and humanistically. Lincoln's music, which at first served as an escape from the life around her, grew into a means of expression, understanding, and communication with others.

Lincoln was born Anna Marie Wooldridge in Chicago in 1930. Her parents soon moved the family to Calvin Center, Michigan, her mother believing a rural area was the best place to raise a family. Since the family was poor, the children often had to entertain themselves with singing, but as the tenth of twelve children, Lincoln had a hard time distinguishing herself. She also sang in school and church choirs, often as a soloist. Her musical approach, however, was mainly influenced by recordings of singers her father borrowed from neighbors: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Lena Horne.

Lincoln proved her own singing capabilities by winning an amateur contest when she was 19 and began her musical career by moving to Los Angeles to sing in nightclubs. By 1952, she had moved to Honolulu to perform as a resident club singer under the stage name Anna Marie, but she still hadn't developed her own identity as a singer.

Lincoln returned to Hollywood in 1954 to sing at the Moulin Rouge, a nightclub with a French-style revue. Under the advice of her manager, lyricist Bob Russell, she changed her name to Abbey Lincoln. She made her recording debut in 1955 “Abbey Lincoln's Affair. A Story of a Girl in Love” (Bluenote) and went on to make several important albums for Riverside as “That’s Him”, “It’s Magic”, and “Abby is Blue”. These albums featured Max Roach on drums, with whom she also collaborated on 1960's landmark jazz civil rights recording, “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite”, composed by Max Roach with lyrics by Oscar Brown, Jr. Her studio sessions included some remarkable sidemen as Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins, Wynton Kelly, Curtis Fuller and Benny Golson.. She recorded “Straight Ahead” (Candid) in 1961 which included Roach, Booker Little, Eric Dolphy and Coleman Hawkins. There was a spell in the mid ‘60’s, in which she pursued an acting career and did not record, save for one date in ’68 again with Max Roach, whom she married in 1962. She wrote “Blues for Mama”, which was covered brilliantly by Nina Simone in 1966.

Despite winning accolades for film roles, Lincoln was relegated to minor television spots, never being allowed to fulfill her possible destiny as an actress. In 1970, frustrated by a stifled acting career and despondent over her recent divorce from Roach, Lincoln sought emotional relief. She began writing her own songs. Since then she has consistently crafted new tunes for her albums. "I write when I'm inspired," she explains. "I don't just sit around waiting to write-or sing or paint for that matter. I wait. If I hear something, I'll write it down or commit it to memory one way or another."

In 1979, almost 15 years after her last U.S. release, Lincoln offered “People in Me.” She had spent the decade writing songs, training her voice, and finding inner peace. After almost ten years of self-exile, Lincoln had emerged as a "strong black wind, blowing gently on and on."

Throughout most of the 1980s, Lincoln continued "in the shadows, looking inward, taking the stuff of her own life—the loneliness, pain, and joy—and turning it into music," Her approach to songwriting is autobiographical; she records the world as she encounters it and offers it back in telling observations. "A singer has the power of the word," she explains. "What we say is direct.... I come from a long line of great singers who were social and specific and sang about their lives and the lives of their people."

Lincoln's voice ascended to that of her celebrated predecessors not only in content but also in timbre. It is a voice now often compared to one of her childhood idols, Billie Holiday, a deep, rich voice, truer to the emotional content of her songs than to musical perfection. She delivers with a strong sense of conviction, conveying the message that she believes every word. She recorded two tribute albums to Billie in 1987, released on the Enja label.

With two releases in the early 1990’s “The World Is Falling Down,” and “You Gotta Pay the Band,: Ms. Lincoln earned both commercial and artistic success. Both are a testament to her life, her artistic vision, her overall empathy for humanity. On 1991's “You Gotta Pay the Band,” she was joined by the great jazz saxophonist Stan Getz, who died shortly after its release. The music they created and communicated together transcended not only the simple joys of life but the pain at its very end.

“A Turtles Dream” (1995) featured an all star lineup and was very well received. The opening song on the record “Throw it Away,” is very poignant, and sets the mood for the duration.

Since 2000 Ms. Lincoln has released “Over the Years,” (2000) “It’s Me,” (2003) “Naturally” (2006), and her most recent “Abby Sings Abby,” released in 2007 on Verve.

With the authority of her years and her musical and human understanding, Abbey Lincoln sheds light on every song she sings. A consummation to date of her life's mastery of word, music, and performance, it's at once a thought- provoking and a life-affirming State of the Soul address.

Abbey Lincoln passed on August 14, 2010.

Source: James Nadal

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2010/08/abbey-lincoln-1930-2010-groundbreaking.html

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Abbey Lincoln, 1930-2010: Groundbreaking Singer, Songwriter, Actor, Painter, Poet, and Activist

Abbey Lincoln was an iconic cultural figure and one of the most important and creatively profound singers--and later songwriters--of the past half century. Belonging to an elite and exclusive pantheon of truly original and innovative song stylists and expressive vocal artists in the Jazz tradition like such towering and legendary figures as Billie Holiday (1915-1959), Sarah Vaughan (1924-1990), Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996), Betty Carter (1929-1998), Dinah Washington (1924-1963), and Nina Simone (1933-2003), Lincoln (born Anna Marie Wooldridge) was an extraordinary and highly gifted individual who not only excelled as a singer and songwriter (and painter) but was also a very fine actress. She was also a deeply committed and progressive social activist who with her late husband the legendary Jazz drummer and composer Max Roach (1924-2007) played a pivotal and dynamic role in the radical African American political and cultural movements of the 1960s and '70s. To say that Lincoln's magnificent and lasting contributions will be sorely missed is a great understatement. She was simply one of the short list of absolutely major and indispensable American artists of our time and like her phenomenal mentors and contemporaries in music, acting, and the visual arts her legacy has been and will continue to be felt wherever great art is being created and shared in this society and culture...

Kofi

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/abbey-lincoln-spirited-and-spiritual-abbey-lincoln-by-rj-deluke.php

Abbey Lincoln: Spirited and Spiritual

by R.J. DELUKE,Lincoln is in a sense a blithe spirit, and yet concerned about the world around her. She sees the problems in society and in the world of art and music, yet avoids complaining or blaming. Like her one idol, Billie Holiday, she tells it like it is. Very often she does it in her own words, with her own poetry expressing her inner feelings and her outer attitudes. The evidence comes forth again on Lincoln's 10th CD for Verve records, It's Me. Like her other Verve discs, it's heavily laden with original songs, put across in her direct, musical-yet-theatrical style that has become one of the most poignantly expressive voices in jazz music — especially since her 1990 signing with Verve.

Abbey is an artist, first and foremost. Secure, content, inquisitive. She is sassy and direct in her commentary — and insightful. She can be brash and charming at the same time, chastising what society and the music industry have done to black music and artists, but at the same time maintaining a whimsical stance when looking at life and the big picture of it all. She's both spirited and spiritual.

"Even though I do not know anything, like everybody on this planet, because they forget everything," she says in her distinctive thoughtful, yet playful, tone. "The human being possesses the art of music all over the world. There's no such thing as people without music. It's more than the birds, because the birds don't write it down. Sometimes they improvise, and sometimes they don't. But the human being is maybe designed on a musical pattern. I don't know. But I know we have music and the people in Africa were definitely given it, and that's why people who are musicians can become athletes and all kind of things, because it's good for your health. It cleanses the air that you breathe and it creates other expressions, to dance and sing and play instruments and get it off!"

Add a dash of realism, however. On the downside, "it has to be for money. That's the thing. It's not our fault. This is what it is. Between us and the god of music is the god of money," says Abbey with a knowing laugh. "The god of money has got us up against the wall."

It's Me begins with an elegant version of "Skylark," done in her behind-the-beat style; expressive and clear and resounding. But that's the last of the standards. There are Abbey originals, as well as a song by her late brother, Robert Wooldridge, who she said was a "wonderful singer" but chose instead to become a lawyer, and later a judge. Also, it is the first label recording with Lincoln and an orchestra. Arrangements by Laurent Cugny and Alan Broadbent augment seven tracks.

"I didn't really know what it was until it was done and I was listening to it," she says of the new CD. "It's really about the music. A tribute to the music they call jazz — the best thing that ever happened to me in my life."

"They Call It Jazz" is an open homage to the art form; a ballad given a heartfelt rendering. "Runnin' Wild" is more up-tempo, though Abbey delightfully strolls effortlessly, almost conversationally, despite the quicker pace. "Can You Dig It" offers uplifting advice for those who may be caught up in a crazy world. Masterful musicians like Kenny Barron, Ray Drummond and Jaz Sawyer offer superb support throughout and help Lincoln get her message out.

"I let it come," she says of her compositional method. "But what it mostly is, usually, is about something that I feel, that I realize and it's what I share. It's like having therapy. I can talk about these things and then I can throw it away. Then I'm not burdened with what I'm witnessing. It can be burdensome, because this is really weird, the world that we've been delivered to. So I sing about it. It makes it possible for me to hang in there [laughter]. Otherwise, I'd be lying on the couch, crazy as a loon."

"The human being is spiritual. It's the only being on the planet that is spiritual, that we know of. We were given dominion here. And we're supposed to be useful to your relatives and distant relatives and everybody else. We know each other from the work that we've left. After the artist is gone the work that they leave here lives forever. We, as a people, have really been blessed in that there's always been some music," says Abbey, illustrating its longevity by noting the title cut, 'It's Me' is a traditional song — probably written 300 years ago, during slavery. "Nobody knows who wrote it. But the writer said something that's universal and forever. He said 'I'm the one. It's me who needs some prayer. Not anybody else. I'm the one who's in charge of my destiny.'"

Lincoln's lyrics throughout her career reflect emotions, personal discoveries and philosophies, and offer illustrative vignettes about existence. With all the trouble in the world, and the eternal struggle for jazz to gain acceptance in the United States, Lincoln is dismayed, but not depressed. Why? Perhaps it comes to down-home logic she learned going back to her childhood with 11 siblings and strong parenting.

"Life has a way of bringing you down front," she says sharply. "And you pay dues for being a fool."

Born Anna Maria Wooldridge, Abbey Lincoln has led a colorful life — cover girl model, actress, singer, political activist, musician — and draws on all her experiences to help shape her pointed observations. From a singing standpoint, she draws on only one person for inspiration.

"Billie Holiday. She sang about the world she lived in. She wasn't phony. And she didn't try to have a good voice. She just told everybody what it was. She told us what it was. It was easy to listen to. I didn't have to worry about her making any notes. It wasn't strange at all," says Abbey, intoning with emotion a lyric to a Holiday staple, " You?ve changed/That sparkle in your eye is gone/Your smile is just a careless yawn. "

"'Strange Fruit,' 'God Bless the Child That's Got His Own.' I don't know of another singer who did what she did, except for Bessie Smith who came before her."

Musically, she's influenced by many of the great jazz artists, including her former husband, the legendary Max Roach. "There's never been a greater drummer on the planet than him. I had a chance to hear Charlie Parker. I met Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton. There's a great wealth of musicians. If you join this force, you will be rewarded wonderfully, if you know how to go there. Not everybody knows how to go there.

"Roach taught me a lot. I learned a lot from him. And Dizzy Gillespie. They are masters. They know exactly what's going down with the music. John Coltrane. They're not guessing at anything. They know what it is they're playing. That's why they call it jazz, because they don't want to give them credit for being anything. Then they'll say, 'I don't want to hear all that jazz.' It's not complimentary," says Lincoln. "In the meantime, that's all they have here in America. There are other forms that they call rock and rhythm and blues, and they're not serious forms. They're great forms. They're marvelous. But what they call jazz is the cream of the crop. It's the world that we live in. It lives forever. Louie Armstrong. Duke Ellington.

"I know we don't remember and don't understand. There's a part of me that forgets my self-existence. I know that we didn't do this on purpose. This was brought to us. When you can't claim your name, then you cannot know your ancestors. And consequently, you don't know your gods and don't know your power. This is what we're stuck with. This music that we call jazz is from these people, who remember, and don't remember anything."

As for other singers, she heard and knew them, but "I like Abbey a lot," she says with a glimmer. "I'm my best fan."

"I'm different," from other jazz singers, including Holiday, she says, "because I am also an actress. And I'm a composer and I'm a lyricist, and I paint. I think that I practice the arts to a greater extent than most people do. Most people are dependent on an industry to see them through. I don't give a hoot about the industry. They can give it to their mother !" she says, biting off the last word... "I met this work long before I even knew there was an industry. I don't need any money. I never did, because the forces have always seen to it that Abbey, even when my name was Anna Marie, didn't starve. I've never been without. I learned how to make garments. My mother taught me how. We had sewing machines, and we learned how to make things. I witnessed my father, whistling while pounding the nail in. That's who I come from."

Lincoln's parents are huge influences in her life.

"I'm the 10th of 12 children. My father midwifed my mother for the last six. He built the house I was born in and grew up in. He also secured a piano for us, because momma didn't work, except in the house, taking care of the children. And she was spiritual. She was beautiful. I was allowed to sit at the piano when I was five years old. I didn't go to it until I was about that age. My mother and father never said to me, 'Anna Marie get off the piano' or 'Anna Marie, play the piano.' They left me alone there. My own space. And none of my brothers and sisters bothered me. They didn't dare.

"I was given this at home. I wasn't abused. I wasn't raped, I wasn't cursed. I got everything I'm wearing right now at home, through my mother and father. I think of my mother every morning. She taught me how to live here, save my soul and not be a victim."

Lincoln began singing as a girl in school and church. The family moved from Chicago to Michigan, and Anna Maria Wooldridge continued singing a bit, but it had slowed down until a friend urged her to try out for a show in Kalamazoo, Mich., "Band Follies," where she performed for three years. "I did not know there was such a thing as a career until I was about 20."

One of her brothers was living in California, and on one of his visits back home, Abbey sought permission to go back with him and live on the west coast. Off she went. It took her on a whirlwind part of her career that included getting film parts and being captured in photographs as a sex symbol, including a magazine cover. She continued to sing, changing her name to Gaby Lee for a time.

"I met a photographer who took pictures of me. I was a pretty girl, they said. Sexy Sepia. And I had my fill of that. My management got me a movie called The Girl Can?t Help It (1956) in Marilyn Monroe's dress, a dress that they said she had worn in 'Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,'" says Lincoln, almost chuckling as she looks back. "They put me in this dress. That wasn't my thing. [laughs] Roach saved me from that too. He said, 'Abbey, I don't like that dress.' Cause I toured in it. So I had a chance to be a sexy glamour queen, Sepia, or to be what Billie Holiday was. It wasn't hard to figure that out.

"I will always remember seeing [Holiday] standing on the stage in a relaxed stance, with her hands like a little doll, looking from one side of the room to the other. Nobody spoke. She sang, ' Hush now, don't explain.' She stole my heart and I think of her always. She was the one who was social. Bessie Smith, before Billie, sang: Up on Black Mountain a child will smack your face/ Baby's crying for liquor and all the birds sing bass/,' she said, 'I'm going up on Black Mountain with my razor and my gun/ I'm gonna shoot him if he stands still, and cut him if he runs..

"The same truth about our world. Well, we live in it. But the best thing that you can do for yourself — I know because I've seen a couple psychiatrists — all you have to do is just be real and tell yourself what you're doing. You don't have to tell anybody else. Tell yourself what you've been doing," she says with a chuckle.

Lincoln's career developed "as a very natural thing. I didn't know there was such a thing as a career," she says, adding in a sly voice, "I was looking for a man to take me to heaven."

"My life took me where I'm at and where I've gone, with the help, always, of my mother. She didn't try and influence me either. But in those days a woman didn't need a job; she didn't need to be successful in money. She married a man who was. I'm partial to that approach," she laughs. "My first recording was with Benny Carter and Bob Russell, ( Abbey Lincoln's Affair: A Story of a Girl in Love, 1956) who wrote the words to 'Do Nothing Till You Hear From Me.' He was the first great lyricist that I ever met in my life. 'Don't Get Around Much Anymore.' 'Crazy He Calls Me.' I met the cream of the crop, the great Bob Russell."

It was Russell who renamed her Abbey Lincoln and became her manager for a time. "That's how I knew what a song was. This was when I was 26 or 27. But I didn't starve along the way. And I wasn't pregnant [laughs]. I wasn't a junkie. I didn't go through none of this crap that I see people go through nowadays, acting like they're crazy."

Lincoln met Roach in California, and upon moving to New York City in her 20s, she ran into him at Small's Paradise. The pair got involved and eventually wed. "Slowly, I got a hold on the music from that perspective, because I got a chance to spend some time with it. Roach introduced me to many brilliant musicians. Thelonious Monk., for one. So I had a chance to meet and know, on a certain level, a bunch of masters. They really are. And the young ones are just like the elders. I don't miss the old men. The men I work with are brilliant. But we need patronage. All people do. If you have a serious form of anything, you need patronage. Someone who'll help you to live and keep you from being luckless and lost. And there are many people with money today who could be paying back what they got from the crowd they were hanging with. Basketball players, football players and any other kind of players. They got it at home. They ought to bring some of it home."

She adds with a sparkle, "If I had any magic, I'd snap my fingers and do it."

"We're not healthy and the reason we're not healthy is that we were sacrificed for slavery," she says of the jazz world. "And nothing has changed. And the country doesn't want to make it well. They want everything they have. You know why it's a ball in Europe, to go there for a little while. They didn't bring the Africans to their shores to enslave. They brought them over here to America, but they don't have any history of that in France or Germany. They knew better than that."

Her time with Roach included helping black causes like CORE and the NAACP. Roach was noted for his activism in the 1960s, with civil rights on the front burner. "He was all the way wide awake, Max was," she says. Lincoln participated in Roach's famous recording We Insist: Freedom Now Suite. During that period, "Nina Simone was singing, 'To Be Young Gifted and Black.' It was a time when Dr. King was on the stump. We did some things for Malcolm X and for Dr. King, even though I never met Dr. King. It was a movement that helped all our lives."

Fighting for rights is still important today, she says, but with the right approach. "We don't need anybody to complain against. We need to look inside and see what it is we're doing wrong. That's all we need to do. And leave everybody alone and stop blaming other people for your crap."

In the 1970s, life shifted again for Lincoln. Her marriage broke up and she was back in California, where she made films like For Love of Ivy with Sidney Portier.

"I taught school in the 70s and also I did a play at the Ebony Showcase Theater. I found things to do. I was the first performer with a name to work the Parisian Room, which was up the street from my house. I created an atmosphere for myself. I didn't go there and lay low and not know what to do. Improvised theater. I did things for Alice Childress, when she was here. If you can't create an atmosphere for yourself, it's too bad. I found that from my mother and my father. My dad was the first generation from slavery. He didn't wait for somebody to see to him. He knew how to see to himself. And his children. That's where I came from. My greatest asset is really my ancestors."

Her career has had the solid support of Verve since 1990, which she calls "a blessing." The company has always been accommodating to the types of projects she wants to do and the music she creates, she said. She tours when she wants and has plenty of offers. But in overall American society, "they're trying to kill the music here. It should be obvious to everybody."

In the meantime, she continues to be creative and hopes the world will wake up soon, "brought down front," so that people learn respect for one another and learn to cherish high forms of artistic expression, like jazz.

"The people are ungrateful and filled with jealousy and worship god in other people's images," she says, even though the answers are really not far away and can be found if people know where to look. "The people who wrote and told us what we should and should not do, and lived thousands of years ago. It wasn't to save our souls. Our souls are brilliant and beautiful. It was to keep you from falling into the hole, dummy. Do you understand? To keep you safe. [But] we didn't get it yet."

Lincoln is aware she's one of the last of the early great singers. "I think about it. Everybody's gone. Betty Carter. Etta Jones. Most everybody's gone." But she knows there are outstanding young musicians on the rise, including singers. "Cassandra (Wilson) is working on it. And Diane Reeves. But the thing that concerns me sometimes is sometimes the singer sounds like they're imitating the horn of musicians. But she has the words and she shouldn't do this because the musicians don't have words to use."

From Lincoln's vantage point, she has risen above the turmoil, if not unscathed, at least no worse for the wear. She has kept herself above the abyss. "I'm a fortunate woman. I'm a movie star, I had a famous marriage, I have many, many songs and the company's named Moseka Music. I don't have a thing to worry about. I followed my heart and my heart brought me home. Besides," she adds with another sly glimmer, " it's time for Abbey."

Related Article: Abbey Lincoln: Through the Years

https://newrepublic.com/article/73368/abbey-lincoln-the-axis-the-civil-rights-movementAbbey Lincoln on the Axis of the Civil Rights Movement

I’d like to stay on the subject of music and Civil Rights for one more post. The ongoing talk about Joan

Baez’s performance of “We Shall Overcome” at the White House has

reminded me how readily we embrace the idea of music as an instrument of

political change when, often, music is more a reflection of changes in

the political realm—an effect, rather than a cause. Not that songs have

no power to influence the way people think or feel; to say that would be

to deny the very value of music as a form of art. Still, in our

eagerness to valorize art and artists, we sometimes inflate the ability

of songs to change the world—especially when the singers of those songs

are agents of white benevolence, like Baez—and we often ignore how

dramatically the world changes music and musicians. Let’s look at the

case of Abbey Lincoln, one of my favorite singers and composers. She

made one of her first appearances on national television in 1958, on

“The Steve Allen Show,” and the performance can be retrieved from

history on YouTube

Allen, probably thinking he was flattering her as a black woman by pawing all over her in words, introduces her as “one of the loveliest young singers we’ve had the pleasure of looking at and listening to on this show in a long time, the beautiful Abbey Lincoln,” and she accommodates him and the panting male public by slithering around as she sings a hipster bossa version of the old swing standard “You Came a Long Way from St. Louis.”

Six years later, after the Freedom Rides and the March on Washington, Lincoln appears in a televised performance with the jazz drummer and composer Max Roach and his band, and she is no longer accommodating the Steve Allen world.

She opens with a few bars of Cole Porter’s “Love for Sale,” spits the song onto the soundstage floor, and proceeds to demonstrate her transformation into a champion of fearless, uncompromising black womanhood. The piece she sings is one movement from the “Freedom Now Suite,” co-composed by Lincoln, Roach (who was married to Lincoln at the time), and Oscar Brown, Jr., and it remains shattering, decades after it was aired—not in America, I should add, but a considerable distance from St. Louis, on Belgian TV.

Abbey Is Blue is the fourth album by American jazz vocalist Abbey Lincoln featuring tracks recorded in 1959 for the Riverside label

AllMusic awarded the album 4½ stars, with the review by Scott Yanow stating: "Abbey Lincoln is quite emotional and distinctive during a particularly strong set... very memorable".[3] All About Jazz also gave the album 4½ stars, with David Rickert calling it "a breakthrough performance in jazz singing", and observing: "With the civil rights movement looming over the horizon, no longer did singers need to stick with standards and Tin Pan Alley tunes and could truly sing about subjects that mattered to them. Lincoln picked up Billie Holiday's skill at inhabiting the lyrics of a song and projecting its emotional content outward, and these songs, all of which deal with sorrow, are stark and harrowing accounts of loss and injustice.

Reflections On A Dozen Years With Abbey Lincoln

Marc Cary came to New York City to find and save his father. Instead, he found artists like Betty Carter and Abbey Lincoln — and saved himself.

"I hadn't seen my dad in 10 years," Cary says over a recent lunch in downtown Manhattan. "He's a percussionist, but he was living another lifestyle, and I came to rescue him. He was living at the Port Authority Bus Station."

Cary was 21; he arrived with only $20 in his pocket. But he was also a talented jazz pianist. On the recommendation of a friend, he soon connected with the late Art Taylor, a venerated jazz drummer. Taylor was assembling a new incarnation of the Wailers, his own seminal jazz group.

"I called him that night, and he told me to come over immediately," Cary says. At the time, Taylor lived a block away in Harlem. When Cary arrived, Abbey Lincoln was there; she lived next door. "[Lincoln] checked me out, gave me a lot of encouragement and told me that one day we'll play together."

Cary's latest album, For the Love of Abbey, is his first solo piano recording. It honors his 12-year tenure with the late jazz vocalist, as well as her prowess for writing emotionally arresting lyrics. But he also pays homage to all those who shaped him, notably his family.

Today, his father is a barber. "When I got out of touch with him, I just let my locks grow," says Cary, who wears dreadlocks. "I never let anybody cut my hair but my dad."

Embracing A Heritage

Born in New York City, Cary was raised between Providence, R.I., and Washington, D.C. Cary's mother, Penny Gamble-Williams, is a cellist. Mae York Smith, his great-grandmother, was not only a classical vocalist and concert pianist for silent movies, but also practiced four-handed piano alongside pianist Eubie Blake. And his grandfather, Otis Gamble, was the first cousin of trumpeter Cootie Williams, best known for his work with the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Like his father, Cary played drums as a teenager, working in a go-go band. But at the time, Cary couldn't fully embrace his musical lineage. His personal life was in disarray, and when he was 15, his parents entered him into a rehabilitation program called RAP, Inc., based in D.C.

"I had a whole other life before music," he says. "I was like most kids these days and I had some problems with the law. To keep me from going to jail, they sent me to this program."

RAP brought him into contact with a gifted musician named Daniel Whitt — a man who could listen to a symphony and transcribe the score as it played. "He was [also] an incredible pianist who took his time to show me some very important things about the piano that I didn't know," Cary says. It marked the first time in his life when he imagined himself as a jazz musician.

Betty And Abbey

Years later, Cary got the gig with Art Taylor's Wailers. That brought him into contact with the late jazz vocalist Betty Carter, who was known for her work with emerging jazz musicians. Cary's name came up frequently, and she finally agreed to have him audition for her band. "By the end of the audition, she was asking me if I had my passport," Cary says.

Carter not only helped Cary obtain a passport, but also bought him a suit and brought him on the road for the next six weeks, traveling to a different city every day. When Cary reached the end of his two-and-a-half-year term with Carter, she told him that he was ready to play with the guys now. "She gave me a little envelope, put it in my vest pocket, smacked me on my ass and told me to get on about my business," he says. "Betty's the one who set me up properly as far as the etiquette of being a musician."

Cary's time with Carter also prepared him for working with another legend of jazz singing: Abbey Lincoln. He was reunited with Lincoln while performing at the memorial service for pianist Don Pullen, fulfilling the prophecy she made years ago in Art Taylor's apartment. He worked with Lincoln for a dozen years.

Cary says one of the most important lessons that he learned from Lincoln was to be "live" and in the moment. "There would be some nights when I would let the emotions kind of run me," he says. "I would try to feel each word and put a chord in that went with the emotion." Lincoln's advice was a great relief: It encouraged him to be more present and instinctual musically. "It's just a simple song," Lincoln would say to him. "I'm delivering the lyric, so just give me the thing that I need. Don't be too emotional. Just be there."

He also credits both Carter and Lincoln for giving him the sensitivity that he needed to approach this music. "A lot of times you won't get that from instrumentalists, because they're not dealing with lyric," Cary says. "Both Betty and Abbey taught me everything about how to accompany a vocalist and how to express myself as a soloist."

People In Me

For the Love of Abbey also proved as something of a cathartic release from the loss of the many musicians who have inspired Cary. Lincoln herself died in 2010 at age 80.

Prior to her death, Lincoln was living in a hospice. Due to an impasse on musician visits, it had been a year and a half before Cary was allowed to see her.

"When I walked in the room, I smiled at her," he says. "Abbey said, 'Marc, we got a gig tonight!' I had to tell her that I left my clothes at home and I'll have to go home and get them." Lincoln had not remembered anyone in months. "The fact that she remembered who I was lets me know that I made an impact on her that even dementia couldn't take away."

One of Lincoln's unfulfilled dreams was to create a physical place for musicians called Moseka House. (She was given the name Aminata Moseka during a ceremony in Africa as a guest of the late Miriam Makeba.) "Almost like a monastery, a place where [musicians] can go and be safe; where they can speak about things that they think about," Cary said.

Moseka House had only existed for Lincoln in her mind. Lately, Cary has been thinking about making Moseka House into a reality. "Because she could realize it in her head," he says, "it lives."

Marc Cary solo - "Throw it Away"

(Composition by Abbey Lincoln)

Marc Cary showcases music from his Abbey Lincoln tribute album, "For the Love of Abbey", at a solo concert at the Yamaha Room in Manhattan.

https://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2010/08/great-abbey-lincoln-1930-2010-throw-it.html

Friday, August 20, 2010

THE GREAT ABBEY LINCOLN (1930-2010)

"Throw It Away" (1980 and 2007)

"You can never lose a thing if it belongs to you..."

Abbey Lincoln (born Anna Marie Wooldridge on August 6, 1930 in Chicago, Illinois) was a jazz vocalist, songwriter, and actress. In 2003 she was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts' (NEA) Jazz Masters Award.

With Ivan Dixon, she co-starred in Nothing But a Man (1964), an independent film written and directed by Michael Roemer. She also co-starred with Sidney Poitier and Beau Bridges in 1968's For Love of Ivy. She was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for For Love of Ivy in 1969. Abbey Lincoln also appears in the 1956 film The Girl Can't Help It, for which she interpreted the theme song, working with Benny Carter. She sang on the 60's landmark jazz civil rights recording, We Insist! - Freedom Now Suite (1960) by jazz musician Max Roach and was married to him from 1962 to 1970.

She worked with many other great jazz musicians like Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, Coleman Hawkins, Jackie McLean, Clark Terry, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Cedar Walton, Joe Lovano, Pat Metheny, Ron Carter, and Miles Davis and made albums with Stan Getz, Mal Waldron and Archie Shepp as well as her own groups.

Abbey Lincoln: "Throw It Away"

Verve Record label, 2007

| 1 Blue Monk | (by Thelonious Monk) | ||

| 2 | Throw It Away | 5:18 | |

| 3 | And It's Supposed To Be Love | 4:45 | |

| 4 | Should've Been | 5:26 | |

| 5 | The World Is Falling Down | 3:39 | |

| 6 | Bird Alone | 4:55 | |

| 7 | Down Here Below | 6:51 | |

| 8 | The Music Is The Magic | 3:53 | |

| 9 | Learning How To Listen | 4:36 | |

| 10 | The Merry Dancer | 6:27 | |

| 11 | Love Has Gone Away | 4:39 | |

| 12 | Being Me |

- Accordion – Gil Goldstein

- Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Resonator Guitar [National], Steel Guitar, Mandolin – Larry Campbell

- Arranged By [Cello, Accordion] – Gil Goldstein (tracks: 4, 7, 11)

- Art Direction – Patrice Beauséjour

- Bass – Scott Colley

- Cello – Dave Eggar

- Composed By – Abbey Lincoln (tracks: 2 to 12)

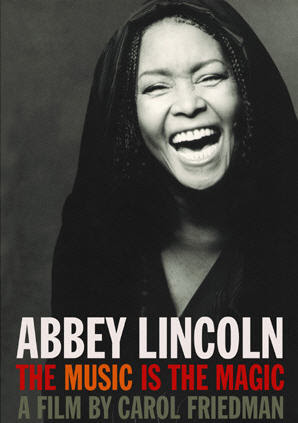

Abbey Lincoln | The Music is the Magic

Documentary film by Carol Friedman

ABOUT THE DIRECTOR:

http://www.carolfriedmanstudio.com/portraits

Carol Friedman photographs and designs image campaigns for celebrated and emerging figures in the art, music and media worlds. Her classic portraits elegantly capture the allure, depth and idiosyncratic style of her iconic subjects. In addition to her photographic works, Friedman's executive and marketing background includes positions as Creative Director for Elektra Entertainment, Art Director and chief photographer for Blue Note Records and Vice President, Creative Director for Motown.

An avowed music lover, her images of jazz, soul and classical recording artists have been widely published and may be seen on hundreds of album and CD covers. Jazz artists, in Friedman's view, "the last bastion of genius, humor and style," were her first subjects and continue to inspire her life and work. Her acclaimed collection of portraits of jazz artists, The Jazz Pictures, was published in 2001 by Arena Editions. She is currently at work on several book and film projects.Friedman is currently editing her feature length documentary film, Abbey Lincoln: The Music Is The Magic, for a fall 2023 release.

Fueled

by a fierce integrity and idiosyncratic style on and off the stage,

Abbey Lincoln has always gone her own way. This ninety-minute

documentary feature film presents Ms.Lincoln's life and work; from her

beginnings as a Hollywood Glamour girl to actor and civil rights

activist to her present standing as one of the most gifted and original

singers and composers of our time. Produced and directed by photographer

Carol Friedman, the film was shot on 16mm in black & white and

color over a period of twenty years.

The film features rare music performances spanning two decades here

and abroad; historic footage of early broadcast performances and clips from her work as a film

actress — all accompanied by Lincoln’s own distinctive narrative. Commentary is

provided by percussionist Max Roach, author and culture critic Gary Giddins, Music producer

Jean-Philippe Allard, Director Michael Roemer, author and columnist Stanley Crouch, Jazz

impresario George Wein and Lincoln’s brother David Wooldridge. In addition to her

performances on stage and screen, we see Lincoln as journeyman — both on the road and in

the recording studio. The trajectory of her remarkable ascension as a prolific composer/lyricist

is the heart of her story. Besides her ever-independent spirit, what sets Lincoln apart from

so many of her contemporaries is her steadfast allegiance to practicint he arts — proficiently

— and in several arenas — and the unwavering integrity that she has always sewn

through all that she does. This film presents an anatomy of the history, discipline, and seemingly

organic process that has hatched this most formidable and original artist.An Interview With Abbey Lincoln from 2001

Yesterday was the 81st birthday anniversary of the singer Abbey Lincoln—also known as Aminata Moseka, and born Anna Marie Wooldridge—who died last August 14th.

Like her inspiration, Billie Holiday, Lincoln was never out to prove that her voice was a great instrument — although, in its own way, it was. Never afraid to make a mistake, never self-censoring, she reached for what she heard. Usually it worked.

I had an opportunity to interview Ms. Lincoln for the bn.com website in February 2001, when her Verve album, Over The Years — one of many superb collaborations with the French producer Jean-Philippe Allard — was released. What follows is the unedited transcript.

Follow this link for her discography.

Abbey Lincoln (2-5-01):

In all of the records that you’ve done with Jean-Philippe Allard, you’ve had various magnificent tonal personalities intersecting with you. How do you go about deciding who you’re going to work with and make music with for each particular project?

Well, I use my band, as usual, the trio that I work with. It was Jean-Philippe who suggested Joe Lovano. I hadn’t thought of him for the album. But I’m glad he did. He was brilliant. And I asked for Jerry Gonzalez, because he worked with me before as a percussionist on an album called Talking To The Sun. I didn’t know he played trumpet! Jaz Sawyer, who is a brilliant musician and drummer, I asked him about a cello player, and he sent me Jennifer Vincent. Kendra Shank came to see me one day, and we were having a little jam, and she played this song for me and I fell in love with it.

Did you do that much before the association with Verve; that is, intersect with other horns within your groups in the period directly before that?

People in Me. In the album I made in Japan, Miles Davis sent me some of his musicians. I asked him for his drummer, and he sent me Al Foster, Mtume and Dave Liebman. I’ve always had a lot of help in the music. When I was with Roach, I got to work with Coleman Hawkins. My first album was with Benny Carter, and Marty Paich was one of the arrangers. Jack Montrose as well.

But you know, it’s a happening. I’m not that wise. It’s like writing a song. I start out at a point, and it gathers energy. I’m fortunate, I think.

What usually comes first, the words or the music, when you’re writing a song?

It all depends. Sometimes it’s the words. Usually it’s the words, and sometimes the music comes much later. But it’s a story that I hear, a point of view, and I have developed it with the words and with the music. But the words are really important for me.

Your songs on this record, are they all recent or do they come from different points? Part of what I’m asking is: Do you write for projects, or with each project do you select from a well of material?

I select from a wealth of material. I don’t wait to record to write a song. If it comes to me, I write it then. “Bird Alone,” when I wrote that, I was in Japan, and Miles Davis was working there as well. He wasn’t so well, you know. And I thought I was writing it for him. But it really was for myself. Later on, years later, I finished the song and recorded it.

The records that you’ve done with Allard have been so rich…

Yes.

…in so many ways. I wonder if you could speak about that relationship and the effect on your records.

I think he is very, very bright. He is a brilliant man, and he knows a lot about music, not only this form, but the Classical tradition and other forms. He called me in 1989 and asked me what I wanted to do. He never tried or suggested that I didn’t know what I was doing, and he wanted to help me to do what I was doing, and that’s what he’s done. The first album was called The World Is Falling Down. He brought me J.J. Johnson. And I asked for Ron Carter. So I get this kind of help from him. I asked for Stan Getz, and he told me he would check it out. So I’ve not been here alone. Jean-Philippe is a great ally. He told me that the newest album, Over The Years, he liked it a lot. So a lot of it is due to an alliance with Allard.

In interpreting your tunes, how specific are you with the musicians?

They’re brilliant.

They help create the arrangements…

No. They’re head arrangements. In that way they help create them. But I know how many choruses I’m going to use. I know what key it is in. And I write them. So it’s me.

Does that develop on the bandstand over touring?

No! [LAUGHS] It’s not as if… They have lead-sheets, they learn the songs, and bring their understanding and their spirit to it. So I don’t try and really control things — except that I do. I like the tempo that I want. Everything is about how I hear the song. And they know how to interpret the song. Brandon McCune is brilliant. So is John Ormond, and so is Jaz Sawyer. That’s my quartet.

Let me ask you about the notion of style, which I think is an insufficient word to describe the way you sing, or maybe I should call it the craft of singing. I realize you’ve said these things before, but could you discuss some of the singers you concentrated on when you were forming your singing personality, and a few words about them.

Well, I heard Billie Holiday when I was 14, on a Victrola, in the country where I was living. She was always a great influence on my life. She was social. And she didn’t try to prove that she had a great instrument. This is not the form for people who use that approach. That’s the European Classical tradition. We have voices. Louis Armstrong was a great singer. It has nothing to do with having a great voice. So I had a chance to listen and to meet many of these great performers and singers, and I come from Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, all of these people. I sing in that tradition. I don’t try for anything they do, just like they didn’t try for anything that anybody else was doing, but interpret a song on a level of understanding and with skills, knowing where one is… They’re brilliant. It’s a brilliant musical form. The musicians are masterful when it comes to theory and harmony… Yeah.

So I’m not here alone. I learned a lot about the music through Max Roach. I didn’t know about Charlie Parker, I didn’t know who he was — or Dizzy or Monk or all these people. Working with Max, I had a chance to meet some of these folks. All of them.

You were just speaking about singing the song with understanding. Could you say a few words about the songs not by you on Over the Years. I’m interested in “Somos Novios.”

Yes! That’s a beautiful love song.

And you sing it beautifully..

Thank you. Armando Mazanero is the writer. I’ve been singing this song for about 15 years, and in Spanish. I’m not sure of everything I’m saying, but I know that it’s a love song. We are lovers. And it has nothing to do with motive or anything. A pure love. It’s one of my favorite songs.

The opening song “When The Lights Go On Again,” is one I’m unfamiliar with.

That comes from the Second World War. When I was 12 or 13 or something like that, I heard that song. I must have been in Kalamazoo at the time. One day I was thinking, working on the album before I went into the studio, and that line just came into my ear. “When the lights go on again all over the world.” I thought, “Wow.” So I called the music store, and they sent it to me…or somebody brought it for me. So it’s like an unconscious companion that is with me all the time, and whispers in my ear sometimes.

I have a certain memory of “The Windmills of Your Mind” with a certain connotation, but it’s certainly not the connotation that you give it.

Well, that’s the glory of a song. It can have more than one meaning.

On Lovano’s solo he sounds like a windmill.

Yes.

“Lucky To Be Me.”

That’s the great Leonard Bernstein. I remember singing that song years ago. There was a brilliant singer named Mabel Mercer, and I heard her sing that on a recording, and I’d been meaning to sing it over the years, but I finally got to it.

And I was spellbound by the conclusion, by “Tender As a Rose.” I was listening last night at about 1 in the morning over headphones so I could have you in my head overnight, and it caught me!

It’s the second time I had a chance to record it. The first time was on an album called That’s Him, with Max and Sonny Rollins and Kenny Dorham, Paul Chambers, and Wynton Kelly. I hadn’t had a chance to have it transposed, because Wynton did that for me. We needed one more song, so I sang it alone, and I’m glad I did. Phil Moore, the composer and the writer, was a brilliant coach whom I went to see a couple of times. He was one of Lena Horne’s teachers. So I added the last line. “Well, that’s the way the story goes, and sometimes the rose was he.” Joanne is here, too. Joe isn’t the only one who is a stalker. Joanne does that, too. Know what I mean? And leads a youngster astray.

I was actually about to ask you about the conclusion of the song. Because not many women would really think to say something like that at the end of a song about evil men.

Well, women like to talk about a man. This is what the songs always were when I came to the stage. It’s about this man who she has to have, and how he treats her badly. Well, I decided I’m not singing that any more. If he’s nothin’, then that makes me nothin’ too. Mmm-hmm. So I sing, for the most part, the praises of a man. He’s God and the Devil and she’s not responsible for anything! [LAUGHS] Well, anyway, I’m not playing that.

But I guess you were placed in that role a lot in the first stage of your career…

Yes.

…as far as having to sing that kind of material and project that type of image.

Yes. I was following after the other singers. Sarah was singing, “You’re mine, you; you belong to me; I will never free you.” [LAUGHS] I was singing the songs of the women who were prominent on the stage. “Happiness is just a THING called Joe.” And “My Man, he beats me, too, what shall I do.” I thought, “Well, leave him.” You know? So I found my way to other conversations and to other things to address.

Another thing that’s fascinating to me is that your songwriting started in mid-life.

It takes a while, I think, to awaken here. I have been writing words, but I never saw myself as a composer. And I would write lyrics to other people’s songs, like Oscar Brown, Jr. So I wrote a lyric to Thelonious’ “Blue Monk.” We hadn’t talked about it. I didn’t ask him if I could write it. But I just wrote it, because I felt that I knew what he was talking about, and it really touched me. And he gave me permission to use it, to record it, and was instrumental… Because he was quoted on the liner notes to an album… They asked Max to do the liner notes when Straight Ahead was rereleased about ten years later. And Thelonious was quoted as saying that I was not only a great singer and actress, but a great composer. I had never written a thing. I knew that he knew something that I didn’t know. Because Thelonious was not a flatterer, nor a liar. And it freed me up. So when I heard “People In Me,” I used it. I mean, I believed it. It’s like a child’s song. And the compositions get better and better for me, I think.

Also, in some of the articles, I remember reading of Monk telling you not to be too perfect. I’ve heard other musicians relate that. Benny Golson relating almost the exact same story, of Monk talking to him and saying “make a mistake; you’re too perfect.”

Well, Roach was the one who said “Make a mistake.” When I told him about it, Roach said, “He means ‘make a mistake.'” It took me a minute…a while to understand that. But what they meant was, you try for something. If you crack, at least you tried for it. Don’t be so perfect. Yeah. Make a mistake. Mmm-hmm. And that’s what this form of singing is all about. I mean, you reach for something and it works. [LAUGHS] Yes.

You made a comment in a piece that Amiri Baraka wrote about you in Jazz Times that men… Well, you came up in a generation when everybody was a rugged individualist, and you couldn’t really be anything if you weren’t. You made a comment toward the end of the piece that women have always been in the music, but the men have been out front, and you said, “the men have a hard time keeping a standard that’s individual.”

I didn’t say that.

Oh, you’re quoted as saying that.

That’s one of the reasons I really dread sometimes interviews. Because I didn’t tell Amiri that.

The men, I say, have like a conception, and it’s a delivery. They cannot run away from their work. It’s something that they have to do. A woman can get married and have a child. She has other options. But he delivers this work. It’s him. Yes. And they all have a style that is their own. If you’re not an individual, you can’t stand along the masters. No, I didn’t say that.

But you just said what you said.

Yes.

In your bands you’ve nurtured a lot of the most individualistic younger musicians, like Steve Coleman and Rodney Kendrick and Mark Cary and the band you have now. I just wonder if you have any sense of the struggles of this generation in maintaining their individuality against the incredible magnificence and weight of the tradition they’re trying to come out of, which you may represent to them as well.

I’ve never worked with greater musicians than the ones I’m working with now, the ones I’ve been working with. They are not lauded and they are not rich yet in money. But I remember when all of these folks weren’t either. It’s always been kind of a secret society. And the musicians are as great as they ever were. There will never be another Charlie Parker. Or John Coltrane. That’s what this work affords us, is individuality, and that’s who you are, and there is nobody to replace you. But Jaz Sawyer and John Ormond… Brandon McCune I got through Betty Carter, you know. That’s how I inherited Marc Cary. He worked with Betty. She was a great teacher, I believe. She taught them a lot about the work. About on the beat! [LAUGHS]

A strict taskmaster, right?

Yes! And it works, too. Mmm-hmm. So I am benefitting from her work.

https://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks/2010/11/12/wandas-picks-radio

Wanda's Picks Radio

- Broadcast in Art

Abbey Lincoln: Blue Monk (1973):

Thejazzsingers channel

Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln: Love For Sale

Abbey Lincoln Quartet 1994 live performance of "Midnight Sun" by Lionel Hampton:

"The Music Is The Magic" by Abbey Lincoln

From the album: 'Abbey Lincoln Through the Years': 1956-2007

Recording labels: Riverside, Candid, Verve; various european labels from France, Germany, UK, and Belgiem

https://www.allmusic.com/album/through-the-years-1956-2007-mw0001958186

Through the Years: 1956-2007

Review by Thom Jurek

Anyone who has followed Abbey Lincoln’s career with any regularity understands that she has followed a fiercely individual path and has paid the cost for those choices. Through the Years is a cross-licensed, three-disc retrospective expertly compiled and assembled by the artist and her longtime producer, Jean-Philippe Allard. Covering more than 50 years in her storied career, it establishes from the outset that Lincoln was always a true jazz singer and unique stylist. Though it contains no unreleased material, it does offer the first true picture of he range of expression. Her accompanists include former husband Max Roach, Benny Carter, Kenny Dorham, Charlie Haden, Sonny Rollins, Wynton Kelly, Benny Golson, J.J. Johnson, Art Farmer, Stan Getz, and Hank Jones, to name scant few.

Disc one commences with “This Can’t Be Love” from

1956; one of the best-known tunes off her debut album, arranged and

conducted by Golson. But the story begins to change immediately with "I Must Have That Man" with her fronting the Riverside Jazz All-Stars in 1957. Tracks from It’s Magic, Abbey Is Blue, and Straight Ahead

are here, and the story moves ahead chronologically and aesthetically

all the way to 1984. But there are also big breaks stylistically, with

her primal performance on “Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace” from We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite in 1960 and the amazing “Lonesome Lover” from It’s Time: Max Roach and His Orchestra and Choir in 1962, which is where her story takes its first recording break. It picks up in 1973 with "Africa" from People in Me. It breaks again until 1980, with “Throw It Away” off the beautiful Painted Lady, and continues through appearances with Cedar Walton and Sun Ra. There is another break in the narrative between discs one and two, commencing again in 1990 with the issue of the brilliant The World Is Falling Down on Verve when she began her association with Allard

and recorded regularly. This disc contains a dozen tracks all recorded

between 1990 and 1992. Disc three commences in 1995 and goes straight

through to 2007. The latter two discs reflect the periods when Lincoln

finally assumed her rightful status as a true jazz icon; individual

track performances from standards to self-written tunes and folk songs

are all done in her inimitable style and are well-known to fans. This

set is gorgeously compiled and sequenced. As a listen, Through the Years

is literally astonishing in its breadth and depth. It establishes her

commitment to artistic freedom, and her fierce dedication to discipline,

song, and performance. The box features liners by Gary Giddins, and great photographs, as well as stellar sound quality.

Track Listing - Disc 1

| Title/Composer | Performer | Time | Stream |

|---|

| 1 | Abbey Lincoln | 02:25 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 2 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:42 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 3 | Abbey Lincoln | 03:57 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 4 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:06 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 5 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:30 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 6 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:13 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 7 | Abbey Lincoln | 08:09 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 8 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:48 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 9 | Abbey Lincoln | 07:04 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 10 | Abbey Lincoln | 07:10 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 11 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:36 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 12 | Abbey Lincoln | 04:40 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 13 | Abbey Lincoln | 04:58 | SpotifyAmazon |

Track Listing - Disc 2

| Title/Composer | Performer | Time | Stream |

|---|

| 1 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:22 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 2 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:01 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 3 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:30 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 4 | Abbey Lincoln | 08:32 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 5 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:10 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 6 | Abbey Lincoln | 08:40 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 7 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:11 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 8 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:22 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 9 | Abbey Lincoln | 03:55 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 10 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:44 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 11 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:15 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 12 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:25 | SpotifyAmazon |

Track Listing - Disc 3

| Title/Composer | Performer | Time | Stream |

|---|

| 1 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:39 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 2 | Abbey Lincoln | 06:52 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 3 | Abbey Lincoln | 07:36 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 4 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:11 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 5 | Abbey Lincoln | 07:56 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 6 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:05 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 7 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:55 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 8 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:24 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 9 | Abbey Lincoln | 03:40 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 10 | Abbey Lincoln | 05:13 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 11 | Abbey Lincoln | 03:54 | SpotifyAmazon | |||

| 12 | Abbey Lincoln | 08:48 | SpotifyAmazon |

Max Roach Quartet & Abbey Lincoln, BRT TV Studio, Schaarbeek, Belgium, January 10, 1964 (Colorized):

Presentation Jan Gheysen 00:00

We Insist! Freedom Now Suite: Intro 2:30

Driva Man 4:50

Triptych (Prayer/Protest/ Peace) 9:58

All Africa 19:09

Freedom Day 25:27

MAX ROACH SEXTET:

Max Roach: drums

Abbey Lincoln: vocals

Clifford Jordan: tenor saxophone

Coleridge Perkinson: piano

Eddie Khan: bass

https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2010/08/18/129285755/the-music-of-abbey-lincoln-pt-1A Look Back At The Music Of Abbey Lincoln, Pt. 1

A Blog Supreme contributor Lara Pellegrinelli first interviewed Abbey Lincoln in 1998. Since then, she's had many further occasions to talk to the late vocalist and songwriter about her life's work. Here, she surveys the entire career of Abbey Lincoln, complete with musical examples which chart Lincoln's growth into a compositional force. Part two will run soon. --Ed.

I've been reading the various tributes to Abbey Lincoln, but it seems that almost everyone has missed the point when it comes to why this woman's music was important and what her place in the history of jazz ought to be. Yes, she was a great singer, one of the best of her generation. She was also a passionate agitator for civil rights, playing an instrumental role in her then-husband Max Roach's groundbreaking Freedom Now Suite. Although both are noteworthy accomplishments, ironically, those who praise Lincoln for the way she sang tend to overlook what she sang.

Her most substantial and potentially lasting achievement is her own body of compositions, around 40 songs in total. They are not innovative in terms of melody, harmony or other technical features. Rather, they are significant first and foremost simply because she wrote them and found opportunities to perform and record them.

To this day, jazz musicians lack recognition as composers. When Lincoln first emerged in the mid-1950s, it was unthinkable that a singer -- let alone a female singer -- would write the majority of her own material.

The cover art to Affair: A Story of a Girl in Love.

It took her until the 1970s to cross that bridge. Lincoln's early records were filled with classics from the so-called American popular songbook: Sentimental, escapist fodder by Gershwin, Rodgers and Hart, Kern and Porter. One only has to see the cover of her debut album on Liberty -- the same label that recorded calendar girl Julie London -– to know what was really being sold: Lincoln is photographed stretched out on her back, her breasts nearly overflowing from the bodice of her dress.

The arrangements, by Benny Carter and Marty Paich, are also a pretty package, bow-tied with strings. They're purely pop, with nothing in Lincoln's forceful but straightforward delivery to suggest that she would become a jazz singer.

"Crazy He Calls Me," from Abbey Lincoln, Affair: A Story of a Girl in Love (1956).

A strikingly beautiful woman, Lincoln told me that she was often judged her by her appearance; people assumed that she couldn't be attractive and a good musician. Luckily, she found an early ally in manager Bob Russell, the lyricist who wrote "Crazy He Calls Me," "Do Nothing 'Til You Hear From Me," and "Don't Get Around Much Anymore." He was the first to encourage Lincoln to study song lyrics, giving her books on vocabulary and semantics.

By the time she recorded her second album, That's Him (1957), she had already started a quest for alternatives to the popular song. Her ensemble here consists of top-shelf jazz musicians: Trumpeter Kenny Dorham, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Max Roach. And Lincoln takes on material associated with Billie Holiday, including this dramatic reading of the troubling "My Man."

"My Man," from Abbey Lincoln, That's Him (1957).

Purchase: Amazon.com / Amazon MP3 / iTunes

"When I came to the stage," Lincoln would later say, repudiating torch song masochism, "the women, the divas, were singing about a man who wasn't much. I did that for a minute and thought, 'Well, this is a drag. If he's nothin', I'm nothin' neither.'"

So she asked fellow vocalist and playwright Oscar Brown, Jr. to write her a song about a beautiful man, a man like her father or her brother. Countering standards of beauty dictated by white society, as well as the kind of racialist descriptions found in lyrics like "Good For Nothin' Joe," Brown breaks new ground with "Strong Man": "Hair crisp and curly and cropped kind of close / Picture a lover like this. / Lips warm and full that I love the most / Smiling between every kiss."

"Strong Man," from Abbey Lincoln, That's Him (1957).

Purchase: Amazon.com / Amazon MP3 / iTunes

Of course, Lincoln told me she still had a bone to pick with Brown over those lyrics: "'I'm in love with a strong man and he tells me" -- not that he is --"He tells me he's wild about me.' Dig it?"

Through the late 1950s and early 1960s, Lincoln's singing gradually became more conversational and idiosyncratic, her rhythm loosened up. Her sense of pitch purposefully became flatter, more nasal and blues-oriented. She started calling herself a jazz singer as a statement of black pride. For her repertoire, she turned increasingly towards the music of her peers in the jazz community: Brown, soon-to-be-husband Max Roach, vocalist Jon Hendricks, saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, flutist Herbie Mann, trombonist Julian Priester, pianists Randy Weston and Thelonious Monk.

It wasn't long before she would begin writing her own lyrics. The first to appear on record is an anxious blues, full of stress and strain: "Let Up," from the 1959 recording of Abbey Is Blue.

"Let Up," from Abbey Lincoln, Abbey is Blue (1959

Purchase: Amazon.com / iTunes

The cover art to Straight Ahead.

By the time Lincoln recorded Straight Ahead in 1961 for journalist Nat Hentoff's Candid label (months after the Freedom Now suite), she wouldn't include any material from the popular songbook on the album whatsoever. Lincoln contributes lyrics to tunes by Monk, Priester, and Mal Waldron, who accompanies her on his own composition "Straight Ahead."

Lincoln's sound is also a far cry from the proper young singer who made Affair just six years earlier. She had caused controversy in those years by wearing her hair naturally; it sounds like let her voice has gone natural, too.

"Straight Ahead," from Abbey Lincoln, Straight Ahead (1961).

Purchase: Amazon.com / Amazon MP3 / iTunes

A Look Back At The Music Of Abbey Lincoln, Pt. 2

PHOTO: Abbey Lincoln, photographed for her 2003 album It's Me. Adger W. Cowans

A Blog Supreme contributor Lara Pellegrinelli has interviewed Abbey Lincoln about her life's work on many occasions. She concludes her two-part survey of the late, great vocalist and songwriter's recorded legacy. Part one is here. --Ed.

1961's Straight Ahead would be the last album Lincoln would record for over a decade. She acted in the films Nothing But a Man (1964) and For Love of Ivy (1968), the latter in which she co-starred with Sidney Poitier. Then her life essentially fell apart: She divorced, checked herself into a mental hospital, and eventually returned to Los Angeles, where she lived in an apartment above a garage.

Sensing that her friend could use a change of scenery, South African singer Miriam Makeba brought Lincoln along on a two-month tour of Africa in 1972. The experience proved life-changing.

Cover art to People In Me. Philips

"I had on an African cloth, but I had made it into a style," Lincoln said. "And I had braided nylon into my hair -- I was coming out of a building with Miriam and another South African woman, and this man asked me, 'Where are you from now?' And I said, 'I'm a citizen in America.' And he said, 'Oh.' That's when I wrote 'People in Me.' They used to tell us we were bastardized here, that we had been raped, that we weren't anything. But that's a lie. He knew I was an African woman. He just didn't know where the hell to put me. 'Where are you from now?'"

"People in Me," from Abbey Lincoln, People in Me (1973).

From that time forward, Lincoln created a steady stream of songs. Of course, she wasn't the only jazz singer to have been a songwriter. Nina Simone blazed this trail during the time of the Civil Rights Movement, but her production tailed off in the 1970s. Betty Carter also wrote some of her own material, but it was "not about the melody," as she often said, or even the narrative for that matter; Carter's songs functioned primarily as vehicles for improvisation.

She was signed to Gitanes (a French arm of what is now Universal Music Group) by producer Jean-Philippe Allard in 1990, resulting in 10 albums. Released on Verve in the United States, they not only re-established Lincoln as a major talent, but also placed her among a roster of stellar voices, ones critical to the label's revitalization and future directions in jazz singing. Because Lincoln refused to be defined by the words of others, she inspired then-up-and-coming singers like Cassandra Wilson to reevaluate their repertoire, and helped open doors for others to create their own material.

She was not only a singer and songwriter. Lincoln painted, made dolls, sewed her own clothes, acted, wrote a play. She created her own distinctive aesthetic world, drawing on African sensibilities and re-envisioning folk traditions of storytelling within jazz. For example, the album Talking to the Sun, which features saxophonist Steve Coleman, pianist James Weidman, bassist Billy Johnson, drummer Mark Johnson and percussionist Jerry Gonzalez, opens with "The River," a radical re-imagining of the American highway:

"The River," from Abbey Lincoln, Talking to the Sun (1983).

Purchase: Amazon.com / Amazon MP3 / iTunes

Cover art to The World Is Falling Down.

From Lincoln's perspective, women -- the ones "who bring the people," as she liked to say -- are endowed with special powers. They are not objects or victims, but rather the teachers of children, the griots, the "ones who tell us where we came from." Her message of female empowerment has no equivalents among the standards. "I Got Thunder (And It Rings)" draws on the Yoruba thunder god Xango: "I'm a woman hard to handle / If you need to handle things / Better run when I start comin' / I got thunder and it rings."

"I Got Thunder (And It Rings)," from Abbey Lincoln, The World Is Falling Down (1990).

Purchase: Amazon MP3 / iTunes

Lincoln's songs tend toward allegory. They are also preoccupied with spirituality: God, ghosts, ancestors. The I Ching is the "magic book" that provides the source for the advice in "Throw It Away," but the song also recalls the period of Lincoln's life when she had disposed of her marriage, and thought she had disposed of her career.

"Throw It Away," from Abbey Lincoln, A Turtle's Dream (1995).

Purchase: Amazon MP3 / iTunes

Lincoln embraced the human condition as one of perfect imperfection. The "Wholly Earth" is not only holy, but "full of cracks and holes like me," Lincoln told me.

"Wholly Earth," from Abbey Lincoln, Wholly Earth (1998).

Personally, she was uncompromising. Fueled by righteous indignation about the ills of our society, she could be unpredictable, cantankerous, intimidating and downright ferocious -- yet also sensitive, kind, and generous. Lincoln was never shy about expressing her opinions. I once asked her if she thought her songs had anything to do with her longevity as a performer. She hesitated only for a moment, nodded, and boiled her answer down into a single phrase: "Because I have something to say."

We owe much to Lincoln's songs for her marvelous career as a performer, as a pioneering woman and singer. If she could hear the ghosts, the spirits in the sounds of the music we call jazz, by the same token, Abbey Lincoln and her music should be with us for a very long time to come.

Abbey Lincoln in concert 1994

The songs: Down here below, Bird Alone, love is you, ce si bon

Abbey Lincoln - Straight Ahead

Candid label, 1961

Straight Ahead is an album by American jazz vocalist Abbey Lincoln featuring performances recorded in 1961 for the Candid label.

This is widely considered by many Jazz critics and listeners one of Abbey Lincoln's greatest recordings, and one of the most influential among singers in Jazz history.

Abbey Lincoln, Bold and Introspective Jazz Singer, Dies at 80

by NATE CHINEN

August 14, 2010

New York Times

Abbey

Lincoln, a singer whose dramatic vocal command and tersely poetic songs

made her a singular figure in jazz, died on Saturday in Manhattan. She

was 80 and lived on the Upper West Side.

Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times. Singer-composer Abbey Lincoln at her home in Manhattan in 2002.

Cinerama Releasing

Ms. Lincoln in the 1968 film “For Love of Ivy.”

Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos

Ms. Lincoln, 1991.

Her death was announced by her brother David Wooldridge.

Ms.

Lincoln’s career encompassed outspoken civil rights advocacy in the

1960s and fearless introspection in more recent years, and for a time in

the 1960s she acted in films, including one with Sidney Poitier.

Long

recognized as one of jazz’s most arresting and uncompromising singers,

Ms. Lincoln gained similar stature as a songwriter only over the last

two decades. Her songs, rich in metaphor and philosophical reflection,

provide the substance of “Abbey Sings Abbey,” an album released on Verve

in 2007. As a body of work, the songs formed the basis of a

three-concert retrospective presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2002.

Her

singing style was unique, a combined result of bold projection and

expressive restraint. Because of her ability to inhabit the emotional

dimensions of a song, she was often likened to Billie Holiday, her chief

influence. But Ms. Lincoln had a deeper register and a darker tone, and

her way with phrasing was more declarative.

“Her utter

individuality and intensely passionate delivery can leave an audience

breathless with the tension of real drama,” Peter Watrous wrote in The

New York Times in 1989. “A slight, curling phrase is laden with

significance, and the tone of her voice can signify hidden welts of

emotion.”

She had a profound influence on other jazz vocalists,

not only as a singer and composer but also as a role model. “I learned a

lot about taking a different path from Abbey,” the singer Cassandra

Wilson said. “Investing your lyrics with what your life is about in the

moment.”

Ms. Lincoln was born Anna Marie Wooldridge in Chicago on

Aug. 6, 1930, the 10th of 12 children, and raised in rural Michigan. In

the early 1950s, she headed west in search of a singing career,

spending two years as a nightclub attraction in Honolulu, where she met

Ms. Holiday and Louis Armstrong. She then moved to Los Angeles, where