ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2021/05/etta-jones-1928-2001-outstanding.html

PHOTO: ELLA JONES (1928-2001)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/etta-jones-mn0000207498/biography

Etta Jones

(1928-2001)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

An understated, dynamic singer within jazz and popular standards, Etta Jones was an excellent singer always worth hearing. She grew up in New York and at 16, toured with Buddy Johnson. She debuted on record with Barney Bigard's pickup band (1944) for Black & White, singing four Leonard Feather songs, three of which (including "Evil Gal Blues") were hits for Dinah Washington. She recorded other songs during 1946-1947 for RCA and worked with Earl Hines (1949-1952). Jones' version of "Don't Go to Strangers" (1960) was a hit and she made many albums for Prestige during 1960-1965. Jones toured Japan with Art Blakey (1970), but was largely off record during 1966-1975. However, starting in 1976, Etta Jones (an appealing interpreter of standards, ballads, and blues) began recording regularly for Muse, often with the fine tenor saxophonist Houston Person. She died from complications of cancer on October 16, 2001, the day her last album, Etta Jones Sings Lady Day, was released.

Etta Jones

Etta Jones - vocalist, recording artist (1928-2001)

Etta Jones was a fine jazz singer who made the most of her vocal talents. She retained a loyal following wherever she sang, and was held in the highest regard by her fellow musicians. Her last three decades were her most productive, in both the quantity and artistic quality of her work.

She was born in South Carolina, but brought up in Harlem. She entered one of the famous talent contests at the Apollo Theatre as a 15 year old, and although she did not win, she was asked to audition for a job with the big band led by Buddy Johnson, as a temporary replacement for the bandleader's sister.

Johnson's band was popular on the black touring circuit of the day, and the experience provided a good grounding for the singer. Etta stayed with Johnson's big band for a year and then went out on her own in 1944 to record several sides with noted jazz producer and writer Leonard Feather. In 1947, she returned to singing in big bands, one led by drummer J.C. Heard and the next with legendary pianist, Earl “Fatha” Hines, whom she stayed with for three years. She worked for a number of bands in the ensuing years, including groups led by Barney Bigard, Stuff Smith, Sonny Stitt and Art Blakey, but went into a period of virtual obscurity from 1952 until the end of the decade, performing only occasionally.

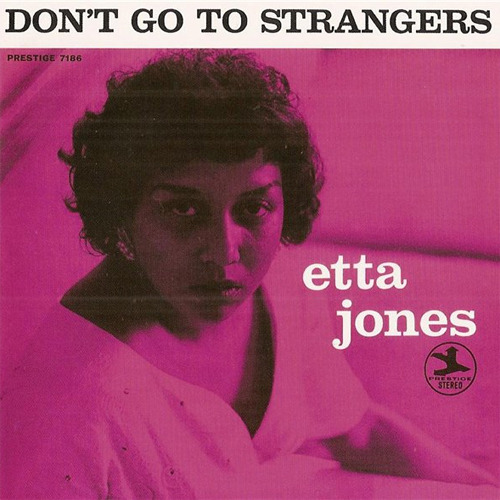

In 1960, she was offered a recording opportunity by Prestige Records, and immediately struck gold with her hit recording of “Don't Go To Strangers.” She cut several more albums for them in the next five years, including a with-strings session, and a guest spot on one of saxophonist Gene Ammons's many records.

In 1968, at a Washington, D.C. gig, Etta teamed up with tenor saxophonist, Houston Person and his trio. They decided to work together and formed a partnership that lasted over 30 years. She toured Japan with Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers in 1970, but after her final date for Prestige in 1965, she did not make another album until 1976, when she cut “Ms Jones To You” for Muse.

Her closest collaborator in that period was Houston Person, and they cut a string of well-received recordings from the mid-70’s onward, including the Grammy nominated albums “Save Your Love For Me,” (1981) and “My Buddy: Etta Jones Sings the Songs of Buddy Johnson” (1999). They developed an appealing, highly intuitive style of musical response, and were always jointly billed. The pair was married for a time, and he became her manager, and produced most of her subsequent records, initially for Muse Records, and then its successor, High Note.

As if to make up for lost time, she recorded eighteen records for the company, and worked steadily both in New York and on the international jazz festival circuit, including appearances in New York with pianist Billy Taylor at Town Hall and saxophonist Illinois Jacquet at Carnegie Hall.

She favored a repertoire of familiar jazz standards; the improvisatory style of her phrasing drew at least as much on the example of horn players as singers, but owed something to Billie Holiday in its sensitivity and phrasing (she was said to do remarkable impersonations of Holiday in private). She took a tougher, blues-rooted approach from Dinah Washington or the less familiar Thelma Carpenter, a singer with the Count Basie band whom Jones acknowledged as an early influence on her own style.

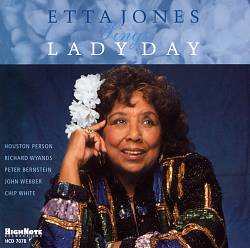

Unfortunately, her physical health began deteriorating, yet she re-emerged in the early 1990s with a new passion for life and a spirit for musical adventure. She took on more solo gigs and began collaborating with young musicians such as pianist Benny Green and veteran bluesman Charles Brown. She continued to perform regularly until just before her death, and still had forthcoming engagements in her diary when she succumbed to complications from cancer. Ironically, her last recording, a Billie Holiday tribute entitled “Etta Jones Sings Lady Day,” was released in the USA on the day of her death, in 2001.

Etta Jones

Singer

Jazz vocalist Etta Jones who was born on November 5, 1928, in Aiken, SC; died on October 16, 2001, in Mount Vernon, NY.recorded more than two dozen albums and earned three Grammy Award nominations during her six-decade-long career. Her popularity peaked in 1960 with the release of her single “Don’t Go to Strangers,” which climbed to number five on the R&B charts. In the late 1960s Jones formed a duo with tenor saxophonist Houston Person, with whom she toured for the next 35 years. “All I want to do is work, make a decent salary, and have friends,” Jones told National Public Radio in a quotation cited in the Dallas Morning News. Although she never attained a level of stardom comparable to such jazz and blues greats as Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, and Dinah Washington, Jones had a devoted following of listeners and made her own unique mark on jazz history.

Jones was born on November 5, 1928, in Aiken, South Carolina, and raised in New York City. As a three year old she dreamed of becoming a singer and would pose in front of a mirror to mimic songs from the radio. Billie Holiday, whom she saw in concert, and Thelma Carpenter, were some of her earliest influences. When Jones was 15 years old, she attended Amateur Night at the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem. Like jazz greats Ella Fitzgeraldand Sarah Vaughn, her career began at the Apollo, though at first glance her debut did not seem promising. On that evening in 1943 she was so nervous that she started singing off key and lost the talent competition. Yet the pianist-bandleader Buddy Johnson recognized her ability. Johnson immediately hired her to fill in for his vocalist sister, Ella Johnson, who was leaving the band to have a baby.

Jones toured with Johnson’s 19-man band for a year, until Ella returned, thus beginning a series of stints with other medium- and big-band New Yorkjazz groups, including the Harlemaires and the Barney Bigards Orchestra. It was with the latter that Jones made her first recording, arranged by pianist Leonard Feather in 1944. In subsequent years she performed and recorded with such jazz personalities as Pete Johnson, J. C. Heard, Kenny Burrell, Charles Brown, Milt Johnson, and Cedar Walton. In 1949 she started singing with Earl “Fatha” Hines, performing with his band for the next three years.

Jones also attempted to launch a solo career, though she was not successful at first. She recorded sides with such labels as Black & White and RCA Victor, but these singles flopped. At the time, R&B was enjoying increased popularity, but Jones avoided this genre, preferring to sing jazz. This decision limited her audience and her exposure as an artist, and for a number of years she remained an obscure singer.

Throughout the 1950s Jones faced hard times and had to take day jobs occasionally to make ends meet, working as an elevator operator, an album stuffer, and a seamstress. She continued to perform sporadically, as opportunities arose. In 1956 Jones recorded her first ull-length album, The Jones Girl… Etta … Sings, Sings, Sings, with King Records. But the album debuted with little fanfare and went largely unnoticed.

The tables turned for Jones in 1960 when her manager, Warren Lanier, sent a demo tape to Esmond Edwards, a producer at Prestige Records. Edwards liked the tape and decided to sign Jones immediately. On the Prestige label she recorded the album Don’t Go to Strangers, released in 1960. Since Strangers was a jazz album, no one expected it to appeal to a mainstream audience. Yet the title song was an instant hit, selling one million copies and putting Jones’ name on the top 40 charts. The song even earned her a Grammy Award nomination—the first of three in her career. While Jones was not an overnight success, she was a sudden success. Her weekly income increased from $50 to $750. Riding on this triumph, Jones recorded several more albums for Prestige throughout the 1960s. But, jazz audiences were dwindling in the United States with the arrival of the Beatles and the growing popularity of pop and rock sounds.

In 1968 Jones formed a musical partnership that would change her career. She met Houston Person, a highly regarded tenor saxophonist, when the two performed on the same bill at a Washington, D.C., nightclub. Jones and Person immediately hit it off, and they decided to tour together as a duo with equal billing, a partnership that would last for more than three decades. “They say… a lot of times singers and musicians don’t get along too well,” Jones told Billy Taylor of Billy Taylor’s Jazz at the Kennedy Center on National Public Radio in 1998, “but we got along famously.”

Person became not only Jones’ collaborator but also—after 1975—her manager and record producer. Their connection was so close that some jazz aficionados have mistakenly assumed they were married, though they were not. Yet their rapport as musicians was unique, and they developed a conversational style with vocals and saxophone riffs. “[Person] knows exactly what I’m going to do,” the New York Times recalls Jones saying. “He knows if I’m in trouble; he’ll give me a note. He leaves me room.”

From the mid-1970s until her death in 2001, Jones and Person recorded 18 albums for the Muse label, which later became High Note Records. While these albums appealed to a relatively narrow audience of jazz aficionados, they occasionally contained minor hits attracting a wider group of listeners. In 1981 Jones received a Grammy Award nomination for her album Save Your Love for Me. A third Grammy nomination came in 1999 for her tribute to her former boss, My Buddy—Etta Jones Sings the Songs of Buddy Johnson.

Late in her career, Jones was able to relax into her role as a highly respected, traditional jazz singer. “When I first started, I had to do some songs I didn’t care for, but now I more or less sing what I want to sing,” she told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1993, as quoted in the Washington Post. “I want a good lyric. I don’t want nonsense. I like heavy dramatic tunes—a tune that’s saying something, like Sammy Cahn’s ‘All the Way.’”

After a battle with cancer, Jones died on October 16, 2001. She was survived by her husband, John Medlock, two sisters, and a granddaughter (a daughter predeceased her). The day she died, High Note released her final recording, Etta Jones Sings Lady Day.

Selected discography:

Don’t Go to Strangers, Prestige/OJC, 1960.

Etta Jones and Strings, Original Jazz, 1960.

Something Nice, Prestige/OJC, 1961.

From the Heart, Prestige/OJC, 1962.

Hollar, Prestige, 1962.

Etta Jones’ Greatest Hits, Prestige, 1967.

Ms. Jones to You, Muse, 1976.

My Mother’s Eyes, Muse, 1977.

Save Your Love for Me, Muse, 1981.

Fine and Mellow, Muse, 1987.

Sugar, Muse, 1989.

Reverse the Charges, Muse, 1991.

At Last, Muse, 1993.

Doin’ What She Does Best, 32 Jazz, 1998.

My Buddy: Songs of Buddy Johnson, High Note, 1998.

Etta Jones Sings Lady Day, High Note, 2001.

Sources

Periodicals

Los Angeles Times, October 19, 2001, p. B13.

New York Times, October 19, 2001, p. C12.

Times (London), October 24, 2001, p. 19.

Washington Post, October 18, 2001, p. B6.

Online

“Etta Jones,” All Music Guide, http://www.allmusic.com. (January 28, 2002).

“Etta Jones,” Billy Taylor’s Jazz at the Kennedy Center, National Public Radio, http://www.npr.org/programs/btaylor/archive/jones_e.html (January 28, 2002).

“Etta Jones, Prolific, Soulful Jazz Vocalist, Nominated Twice for Grammys, Dies,” Dallas Morning News, http://www.dallasnews.com/obituaries/STORY.e99db45424.b0.af.0.a4.d797.html (January 28, 2002).

“Houston Person and Etta Jones at Joe Siegel’s Jazz Showcase in Chicago,” JazzSet, National Public Radio, http://www.npr.org/programs/jazzset/archive/2001/011206.ejones.html (January 28, 2002).

“Remembering Etta Jones,” All About Jazz, http://www.allaboutjazz.com/articles/arti1101_03.htm (January 28, 2002).

—Wendy Kagan

But who’s to know early on what they will eventually become? How much information on how many people and subjects should be stored away for possible future use?

I entered into communications many years ago and, fortunately, my rewind button has been of great assistance in helping me make a living. In this column, I decided to write about singer Etta Jones. My recall took me back to the mid 1950s, when I first saw and heard her perform at a little club in Philly. She had not become “the” Etta Jones yet, and I certainly had no idea that six decades later, she would not be alive and I’d be writing a column about her.

I liked what I’d heard from Ms. Jones that night at the little club in Philly. I don’t remember hearing much about and from her, until her 1960 hit, “Don’t Go To Strangers.” When the single became an LP, it went gold.

I didn’t hear much about Etta between that first time, and “Strangers,” because she hadn’t been doing much recording. She was working to make ends meet, as an elevator operator, seamstress, and stuffing LPs into jackets for a major record company.

With “Don’t Go To Strangers,” Etta Jones became a known entity in the entertainment world. But that recognition came after a long apprenticeship, which began with her entering an amateur contest in 1943 at the age 15. Even though she did not take first prize, she caught the ear of bandleader Buddy Johnson and sang with his band for a year. She later recorded a few sides with the famed pianist and jazz authority Leonard Feather, then went on to sing in the bands of J.C. Heard and Earl “Fatha” Hines. The stint with Hines lasted three years.

But Etta’s successful single and follow-up LP did not bring her the future success expected. She made a number of other albums for Prestige and other labels, but nothing major happened, even though she had great looks, a fine voice, and knew how to put over a song as well as any of her female vocal contemporaries.

A change for the better came when she met saxophonist and bandleader Houston Person, who had a keen understanding of the recording industry, and not only was producing his own recording sessions for the Muse label, but those of other artists, too. He and Etta decided to join forces, travel together and work as a team, and they did so successfully for better than 30 years.

This took Etta out of the race for wider recognition she hadn’t been able to capture. Person was an excellent tenor saxophonist and bandleader, knew the music business, and was always working. He and Etta traveled together domestically and abroad, and were always in high demand. Each worked independently on occasion, but most of the time they appeared together, which gave rise to the belief among jazz writers and fans that they were married.

In 1977, I finally got to meet the lady I’d seen and heard when I introduced Etta and Houston at another club in Philly, at which I was the emcee. I continued to follow Etta’s career over the years, and whenever possible would attend her and Houston’s appearances.

In 2001, I learned she was seriously ill and may not have long to live. I was present at one of her last concerts in Atlantic City in July of that year. She had to be helped onstage and sang while seated. But standing or seated, it was still Etta Jones. I saw her after the show, and knew it would probably be the last time—and it was. Etta passed away a couple of months later, just shy of her 73rd birthday.

Etta Jones, a very fine singer of song who for whatever reasons didn’t get all the accolades her talent earned. I guess some folks just didn’t recognize her talent. She received three Grammy nominations and in 2008, her album Don’t Go To Strangers was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Much like Heinz, the maker of condiments who boasts having 57 varieties, Etta had at least that many ways of interpreting a song. She once said, “I never sing a song the same way again. I can’t even sing along to my own records.”

So even after six decades, every now and then the image and the memory of when and where I first saw and heard Etta Jones pops into my noggin.

Etta Jones, jazz singer: born Aiken, South Carolina 25 November 1928; married (one daughter deceased); died New York 16 October 2001.

"Somewhere betrween Ella Fitzgerald and Dinah Washington," was how the bandleader Earl Hines described his singer Etta Jones. He could have said that she was somewhere between Billie Holiday and Ella Johnson as well, and yet, paradoxically, Etta Jones's style was unique.

Because she chose to sing the same kind of subtle and demanding ballads that Sarah Vaughan did, her work has not dated. She was a musical singer with clear diction who could see a whole performance, not just her own role in it, and she took care to give major roles to her accompanying musicians. As a result it is still a most invigorating experience to hear her 1978 version of Tadd Dameron's "If You Could See Me Now", or "It Could Happen to You".

"When I first started I had to do some songs I didn't care for," she said in 1993. "But now I more or less sing what I want to sing. I want a good lyric. I don't want nonsense. I like heavy, dramatic tunes."

But she was also expert at rhythm and blues and the more sophisticated edges of pop music. Her 1960 recording of "Don't Go to Strangers" made more than $1m. She was an improvising jazz singer, too. "I never sing a song the same way again. I can't even sing along to my own records."

Few of her many albums were sold in this country but her albums won two Grammy nominations and she recorded for Prestige, Muse, RCA, Roulette and High Note records. Even so, mysteriously, her talents were largely unrecognised. Maybe she wasn't pushy enough. "All I want to do is work, make a decent salary and have friends," she said.

Despite latterly being confined to a wheelchair, she sang to her many friends in New York clubs until the end of her life and her last album, a tribute to Billie Holiday called Etta Jones Sings Lady Day, arrived in the record shops on the day that she died.

Born in South Carolina, she grew up in New York and made her first mark when, at 15, she was discovered at one of the famous talent contests at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem. As a result Jones was hired in 1944 to sing with the Buddy Johnson Band, succeeding Buddy's sister Ella Johnson, who became her lifelong friend and mentor. Jones made her first recording with Johnson's band and during the Forties recorded with a variety of jazz instrumentalists ranging from Barney Bigard to Kenny Burrell and Milt Jackson. She moved on to Earl Hines's band and stayed with the pianist for three years.

In 1952 she decided to go out on her own but work was scarce and during the next few years she also worked as an elevator operator, a seamstress and at other more mundane jobs. It came as a surprise when success finally arrived in 1960 with "Don't Go to Strangers". "They told me I was all over the jukeboxes and I couldn't believe it. So a friend of mine took me to a bar. I couldn't believe it." She earned a gold record.

She was working in Washington, DC, in 1968 when she first sang with the trio of a young tenor saxophonist called Houston Person. Their music mixed with such delicacy that they decided to work as a regular team and did so for almost 29 years. "It's been a wonderful relationship. He takes care of me, he watches over me. He's just been my best, best friend." The partnership was compared to the legendary collaboration between Billie Holiday and Lester Young in the Thirties.

Person and Etta Jones reunited for their last job together in New York three weeks ago. "We didn't have any egos or anything," Person said last week. Both had sensitive musical perspective and the blend of vocal and instrumental solo was made more telling by their modesty.

Jones fought off serious illness at the beginning of the Nineties and came back for some remarkable collaborations with the younger generation of jazz musicians, including the pianist Benny Green and the blues singer Charles Brown.

Apart from her gold record, Etta Jones won Grammy Award nominations for her album Save Your Love for Me (1981) and My Buddy – the songs of Buddy Johnson (1998). She also picked up the Eubie Blake Jazz Award and the lifetime achievement award of the International Women in Jazz Foundation.

Steve Voce

https://www.pilotonline.com/entertainment/columns/article_a9679464-357b-522f-853c-fabff06fcdfa.html

Play With Fire Til Your Fingers Burn: Etta Jones Sings Don't Go to Strangers

by RASHOD OLLISON

THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT

October 2, 2013

Like most artists of her generation, Etta was influenced by Billie Holiday, absorbing the legend's languorous, hornlike behind-the-beat phrasing. Etta was assured and seasoned in the summer of 1960. Lady Day still haunted her sound, but Etta had a tart and sensitive style all her own.

Soon after signing a contract with Prestige Records, she stepped inside Van Gelder Studio with a sharp quintet: Frank Wess on flute and tenor sax; Skeeter Best on guitar; George Duvivier on bass; Roy Haynes on drums; and Richard Wyands on piano. By the end of that June evening, they had recorded all 10 tracks for Don't Go to Strangers, Etta's debut for Prestige and her finest album. It was also the record that made her a star, if only for a moment.

It opens with a swinger, "Yes Sir, That's My Baby," which Etta handles with soulful ease, shifting tones as though she were a saxophone and driving the tune, all while singing behind the beat. The solos, Frank's bright flute and Richard's economical piano, complement the song's sprightliness.

The second cut, the album's title tune, became Etta's signature. She had selected the song for the session, a number her producer, Esmond Edwards, hadn't heard before. Maybe that explains the unfussiness of the production – not that any other parts of the album are overproduced. But "Don't Go to Strangers" almost has a charming demo quality to it, as though later the "sweetening" (strings and things) were going to be added. Back in 1960, that was the way ballads were usually produced.

But "Don't Go to Strangers" is a crystalline jazz performance, which became a pop and R&B hit after Prestige had the good sense to release it as a single. The song's appeal lies in its gorgeous simplicity, leavened by the silken wonder of Etta's vocal. What made her great is encapsulated here: the supple blues-suffused phrasing and the way she suspends time, pulling notes like taffy or setting them adrift in the airy, graceful arrangement.

The song reached No. 5 on the R&B chart and peaked at No. 36 on the pop side, fueling sales for the album. "Don't Go to Strangers" was a superlative cut, on par with any of the greatest recordings of Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. Still, the album glimmered with other gems.

Etta pays tribute to her idol, Lady Day, on "Fine and Mellow," a sophisticated blues that's equal parts uptown and downtown. Etta is at her bluesy best here. Skeeter's guitar shines behind the vocalist on "If I Had You." Etta beautifully recasts the melody, giving the old chestnut new life. Her uncanny sense of timing – pushing and pulling the melody without sacrificing the integrity of the lyric – is showcased "On the Street Where You Live."

She imbues "Bye Bye Blackbird" with a slight gospel feel while improvising the melody like a sly horn player. The album closes with "All the Way," a song identified with Frank Sinatra. Dripping with sweet earthiness, Etta's version almost renders Ol' Blue Eyes' irrelevant.

She recorded many other albums for Prestige – most solid but some were overdone with florid strings. Throughout the '60s, the singer was often confused with Etta James, the legendary, hard-living soul shouter who reinvented herself as a jazz singer in her later years.

Like Someone in Love - https://youtu.be/ZTcA1dg-67I

Etta Jones featuring The Cedar Walton Trio: A Soulful Sunday, Live at the Left Bank

by Will Layman

January 31, 2019

Spectrum Culture

by Ben Ratliff

October 19, 2001

New York Times

Etta Jones, a great and permanently underrated jazz singer who for three decades toured constantly with her musical partner, the saxophonist Houston Person, died on Tuesday at her home in Mount Vernon, N.Y. She was 72.

The cause was cancer, said Joe Fields, the manager of her record label, High Note.

Born in Aiken, S.C., and reared in Harlem, Ms. Jones early on developed wily devices for a small voice. She used silence, the sound of the breath, a quick yodel here and there, lyric readings that drew out or shut down syllables idiosyncratically, and a sliding pitch that made her an extraordinary blues singer. Billie Holiday was the most obvious and famous precedent for her style, and she was capable of astonishingly close Holiday impersonations, though she rarely let her audiences hear them.

But her hard-edged blues sensibility owed something to Dinah Washington, while her highly improvised phrasing came from horn players like Sonny Stitt. Ms. Jones always cited as an influence Thelma Carpenter, a onetime Count Basie vocalist who became a heavy-vibrato torch singer. Neither a shouter, a whisperer nor a bebopper, Ms. Jones clung fast to a set of jazz standards from the 1940's and 50's, and tunes by composers like Sammy Cahn, her favorite, whose songs are the subject of her 1999 album, ''All the Way.''

With Mr. Person, her musical partner of more than 30 years, Ms. Jones toured the country, still playing often to primarily black audiences, but also by the late 90's appearing twice a year at the Village Vanguard in Manhattan and at international jazz festivals; she was an evergreen presence in the New York jazz world, and kept up her concert schedule until two weeks before her death.

At 15, Ms. Jones sang at the Apollo Theater's amateur night in the summer of 1944, and immediately after her performance she auditioned for and won a job singing with Buddy Johnson, who led a 19-man band. Johnson's group played in a common vernacular jazz style of the 40's -- a mixture of rhythm-and-blues and jump blues -- and, as a second-tier group not as popular as the likes of Basie, Ellington and Eckstine, the band toured black-only clubs and auditoriums throughout the country.

Her job was as a temporary replacement for Ella Johnson, Buddy Johnson's sister, who was on a maternity leave. When Ella Johnson returned to the band, Ms. Jones began working for different groups until the early 1950's, among them the Harlemaires and bands, from medium-size to big, led by Barney Bigard, Pete Johnson, Earl Hines, J. C. Heard and Sonny Stitt.

In 1952 she began eight years of semiretirement, singing intermittently. Finally, in 1960, she was contracted by Prestige Records, and recorded ''Don't Go to Strangers,'' which became a Top 40, million-selling hit, changing her weekly income, as she once put it, from $50 to $750.

By the end of the 1960's, she had developed a trusting partnership with Mr. Person, a big-toned saxophonist. In performance they developed a conversational style of answering each other's lines. ''He knows exactly what I'm going to do,'' she once said. ''He knows if I'm in trouble; he'll give me the note. He leaves me room.'' They were always billed equally, an unusual arrangement for any jazz singer. Starting in 1976, they began recording for Muse, which later changed its name to High Note, and Mr. Person became her manager and record producer through 18 records.

She had three Grammy nominations, for the ''Don't Go to Strangers'' LP in 1960, ''Save Your Love for Me'' in 1981 and ''My Buddy'' in 1999. But she never recorded for a major label; her temperament was decidedly unlike a diva; and outside of the small period of time around ''Don't Go to Strangers,'' she never commanded high concert fees.

Ms. Jones is survived by her husband, John Medlock, of Washington; a granddaughter, Lia Greatheart-Mitchell of Mount Vernon; and sisters Edna Taylor of Akron, Ohio, and Georgia Johnson of Aiken.

Her new and final High Note album appeared in stores on the day she died, ''Etta Jones Sings Lady Day.''

Etta Jones (November 25, 1928 – October 16, 2001) was an American jazz singer.[1] Her best-known recordings are "Don't Go to Strangers" and "Save Your Love for Me". She worked with Buddy Johnson, Oliver Nelson, Earl Hines, Barney Bigard, Gene Ammons, Kenny Burrell, Milt Jackson, Cedar Walton, and Houston Person.[2]

Jones was born in Aiken, South Carolina,[1] and raised in Harlem, New York. Still in her teens, she joined Buddy Johnson's band for a tour although she was not featured on record. Her first recordings—"Salty Papa Blues", "Evil Gal Blues", "Blow Top Blues", and "Long, Long Journey"—were produced by Leonard Feather in 1944, placing her in the company of clarinetist Barney Bigard and tenor saxophonist Georgie Auld.[1] In 1947, she recorded and released an early cover version of Leon Rene's "I Sold My Heart to the Junkman" (previously released by the Basin Street Boys on Rene's Exclusive label) while at RCA Victor Records.[3] She performed with the Earl Hines sextet from 1949 to 1952.[4]

Following her recordings for Prestige, on which Jones was featured with high-profile arrangers such as Oliver Nelson and jazz stars such as Frank Wess, Roy Haynes, and Gene Ammons, she had a musical partnership of more than 30 years with tenor saxophonist Houston Person, who received equal billing with her.[5] He also produced her albums and served as her manager after the pair met in one of Johnny "Hammond" Smith's bands.

Although Etta Jones is likely to be remembered above all for her recordings on Prestige, her close professional relationship with Person (frequently, but mistakenly, identified as Jones' husband) helped ensure that the last two decades of her life would be marked by uncommon productivity. Starting in 1976, they began recording for Muse, which later changed its name to HighNote. Mr. Person became her manager, as well as her record producer and accompanist, in a partnership that lasted until her death in 2001.[6]

Only one of her recordings—her debut album for Prestige Records (Don't Go to Strangers, 1960)—enjoyed commercial success with sales of over 1 million copies. However, her remaining seven albums for Prestige, and beginning in 1976, her recordings for Muse Records, and for HighNote Records secured her a devoted following.[1] She had three Grammy nominations: for the Don't Go to Strangers album in 1960, the Save Your Love for Me album in 1981, and My Buddy[7] (dedicated to her first employer, Buddy Johnson) in 1998. In 2008 the album Don't Go to Strangers was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[8] In 1996, she recorded the jazz vocalist tribute album, The Melody Lingers On, for the HighNote label.[9] Her last recording, a tribute to Billie Holiday, was released on the day of Jones' death.[10] Over the course of her career, Jones had 27 songs appear on the Billboard Hot 100 with nine of them reaching the top 40.[11]

She died in Mount Vernon, New York at age 72, from cancer.[2][12]

Guest appearances

With Houston Person

- The Real Thing (Eastbound, 1973)

- The Lion and His Pride (Muse, 1994)

- Christmas with Houston Person and Friends (Muse, 1994)

- Together at Christmas (HighNote Records, 2000)

Discography

- The Jones Girl...Etta...Sings, Sings, Sings (King, 1958)

- Don't Go to Strangers (Prestige, 1960)

- Something Nice (Prestige, 1961)

- So Warm: Etta Jones and Strings (Prestige, 1961)

- From the Heart (Prestige, 1962)

- Lonely and Blue (Prestige, 1962)

- Love Shout (Prestige, 1963)

- Hollar! (Prestige, 1963)

- Soul Summit Vol. 2 (Prestige, 1963)

- Jonah Jones Swings, Etta Jones Sings (Crown, 1964)

- Etta Jones Sings (Roulette, 1965)

- Etta Jones '75 (20th Century/Westbound 1975)

- Ms. Jones to You (Muse, 1976)

- My Mother's Eyes (Muse, 1978)

- If You Could See Me Now (Muse, 1979)

- Save Your Love for Me (Muse, 1981)

- Love Me with All Your Heart (Muse, 1984)

- Fine and Mellow (Muse, 1987)

- I'll Be Seeing You (Muse, 1988)

- Sugar (Muse, 1990)

- Christmas with Etta Jones (Muse, 1990)

- Reverse the Charges (Muse, 1992)

- At Last (Muse, 1995)

- My Gentleman Friend (Muse, 1996)

- The Melody Lingers On (HighNote, 1996)

- My Buddy: Etta Jones Sings the Songs of Buddy Johnson (HighNote, 1997)

- Some of My Best Friends Are...Singers with Ray Brown (Telarc, 1998)

- All the Way (HighNote, 1999)

- Together at Christmas (HighNote, 2000)

- Easy Living (HighNote, 2000)

- Etta Jones Sings Lady Day (HighNote, 2001)

- Don't Misunderstand: Live in New York with Houston Person (HighNote, 2007)[9]

- The Way We Were: Live in Concert with Houston Person (HighNote, 2011)

External links

Funny story. So I’m quickly trawling through Counterpoint Records in Hollywood and stumble upon a record marked “rare.”It’s a day before Christmas and I’m looking for a last minute gift. An album from Etta James can’t help but be well-received, right? In light of her shaky health, her music gains an extra (unneeded but natural) pathos. So I take the gift to the friend. Records spins. Album cover is scrutinized. “This isn’t Etta James.” Indeed.

The inevitable Wiki research reveals that I need to go to the Derek Zoolander School for Kids Who Can’t Read Good. Certainly I’m not the only one to make this mistake. Etta Jones‘ Wiki highlights the fact that she is not to be confused with Etta James nor her namesake, Etta Jones (formerly of the Dandridge Sisters). Apparently, there is not much difference that a name makes. Both Etta’s share gorgeous voices, jazz sensibilities and a timeless nature to their music. Their sound is so pristine that it could make a slum seem sparkling.

The record in question was Don’t Go to Strangers, Jones’ first record released on jazz indie Prestige in 1960. Stranger still is that this was once considered a pop record, a platinum seller that briefly made Jones a star. It’s all covers (Billie Holiday, Cole Porter) or songs scribed by other songwriters. And they’re all beautiful and ideal at deluding you into believing you’re in a different decade. Jones slipped off the earth in 2001 and her name hasn’t achieved the resonance of the other Etta. But don’t let anyone tell you differently. If she ain’t better than Billie, she’s the closest one (or at least tied). Chalk another victory up for the wonderful serendipity that illustrates why record shops will always be better than buying online. And that hooked on phonics is some bullshit.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2001/10/18/singer-etta-jones-dies-at-72/

Singer Etta Jones Dies at 72

by Adam Bernstein

October 18, 2001

The Washington Post

Etta Jones, 72, a jazz singer whose sinuous, after-midnight style could be heard on about 25 albums and at countless club dates, and who was best known for her 1960 recording of "Don't Go to Strangers," died of complications from cancer Oct. 16 at her home in Mount Vernon, N.Y. She also had a residence in Washington.

"Don't Go to Strangers" earned more than $1 million for the Prestige label. Since then, Ms. Jones became a respected interpreter of standards like "Stormy Weather," "Say It Isn't So," "Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You" and "But Not For Me."

Fond of improvising, she told the audience during a 1998 Kennedy Center concert with pianist Billy Taylor and his trio: "I never sing [a song] the same way again. I can't even sing along to my own records."

Ms. Jones received Grammy Award nominations for "Save Your Love For Me" (Muse, 1981) and "My Buddy: The Songs of Buddy Johnson" (HighNote Records, 1998).

She died on the day her most recent album was released, "Etta Jones Sings Lady Day" (HighNote), a tribute to Billie Holiday.

Of all those with whom she performed, including saxophonist Illinois Jacquet at Carnegie Hall, her most recognizable partner was tenor saxophonist Houston Person.

They were first booked together in 1968 at Jimmy McPhail's Gold Room in the District, and until their final date together three weeks ago, their interaction was often likened to the fruitful pairing of Holiday and saxophonist Lester Young in the 1930s.

A St. Louis Post-Dispatch reviewer called their collaboration "one of those rare musical matches in which each artist complements the other -- without any battles for the spotlight."

"We didn't have any egos or anything," Person said in an interview yesterday.

Despite her long career, Ms. Jones never achieved household name recognition and was considered a hidden treasure to fans such as Taylor.

"All I want to do is work, make a decent salary and have friends," she once told an interviewer. "What's so good about this singing business is that I have friends all over the world. And without singing, I wouldn't have that."

Ms. Jones, a native of Aiken, S.C., grew up in New York, where her parents encouraged her singing. At 15, she lost a talent contest, but pianist-bandleader Buddy Johnson hired her anyway. In 1944, she made her first recording, for composer-critic Leonard Feather.

Through the 1940s, she recorded with clarinetist Barney Bigard, guitarist Kenny Burrell and vibraphonist Milt Jackson, among others. She became a vocalist for three years with legendary pianist Earl "Fatha" Hines.

Beginning in 1952, she tried to carve a solo career but had to work as an elevator operator, a seamstress and an album stuffer to make ends meet. Then came "Don't Go to Strangers."

She worked for the Prestige label during the next five years and then toured Japan with drummer-bandleader Art Blakey in 1970. She made many recordings for the Muse label from the mid-1970s to mid-1990s, when she became affiliated with its successor firm, HighNote.

During the past decade, she performed with pianist Benny Green and blues pianist and singer Charles Brown.

"When I first started, I had to do some songs I didn't care for, but now I more or less sing what I want to sing," she told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1993. "I want a good lyric. I don't want nonsense. I like heavy dramatic tunes -- a tune that's saying something, like Sammy Cahn's 'All the Way.' "

She received the Eubie Blake Jazz Award and the International Women in Jazz Foundation's lifetime achievement award.

Survivors include her husband, John Medlock of Washington; two sisters; and a granddaughter.

A daughter from a previous marriage predeceased her.

Grammy-nominated jazz singer Etta Jones, shown with saxophonist Houston Person, died at 72.