SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BAIKIDA CARROLL

(September 3-9)

BILLY DRUMMOND

(September 10-16)

BOBBY MCFERRIN

(September 17-23)

ALBERT KING

(September 24-30)

ZENOBIA POWELL PERRY

(October 1-7)

DEAN DIXON

(October 8-14)

DOROTHY DONEGAN

(October 15-21)

BOBBY BLUE BLAND

(October 22-28)

CLORA BRYANT

(October 29-November 4)

CARLOS SIMON

(November 5-11)

VALERIE CAPERS

(November 12-18)

ROLAND HAYES

(November 19-25)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/albert-king-mn0000617844/biography

Albert King

(1923-1992)

Biography by Stephen Thomas Erlewine

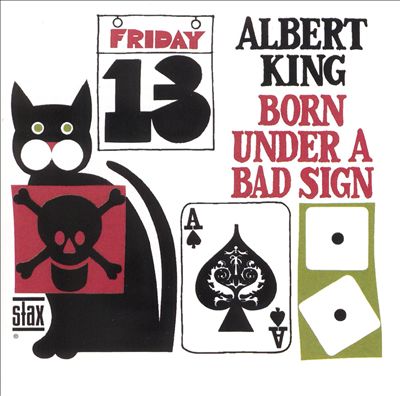

Along with B.B. and Freddie King, Albert King is one of the major influences on blues and rock guitar players, and without him, modern guitar music would not sound as it does -- his style has influenced blues players from Otis Rush and Robert Cray to Eric Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan. It's important to note that while almost all modern blues guitarists seldom play for long without falling into a B.B. King guitar cliché, Albert King never did -- he had his own style and unique tone from the beginning. He played left-handed, without re-stringing the guitar from the right-handed setup; this "upside-down" playing accounts for his difference in tone, since he pulls down on the same strings that most players push up on when bending the blues notes. His first album for Stax, the 1967 singles collection Born Under a Bad Sign, became one of the most popular and influential blues albums of the late '60s. King's massive tone and unique way of squeezing bends out of a guitar string enormously impacted followers, especially in rock & roll, where many players who emulate his style may never have heard of Albert King, let alone heard his music. His style is immediately distinguishable from all other blues guitarists, and he holds the status of one of the most important blues guitarists to ever pick up the electric guitar.

Born in Indianola, Mississippi, but raised in Forrest City, Arkansas, Albert King (born Albert Nelson) taught himself how to play guitar when he was a child, building his own instrument out of a cigar box. At first, he played with gospel groups -- most notably the Harmony Kings -- but after hearing Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, and several other blues musicians, he solely played the blues. In 1950, he met MC Reeder, who owned the T-99 nightclub in Osceola, Arkansas. King moved to Osceola shortly afterward, joining The T-99's house band, the In the Groove Boys. The band played several local Arkansas gigs besides The T-99, including several shows for a local radio station.

After enjoying success in the Arkansas area, King moved to Gary, Indiana, in 1953, where he joined a band that also featured Jimmy Reed and John Brim. Both Reed and Brim were guitarists, which forced King to play drums in the group. At this time, he adopted the name Albert King, which he assumed after B.B. King's "Three O'Clock Blues" became a huge hit. Albert met Willie Dixon shortly after moving to Gary, and the bassist/songwriter helped the guitarist set up an audition at Parrot Records. King passed the audition and cut his first session late in 1953. Five songs were recorded during the session and only one single, "Be on Your Merry Way"/"Bad Luck Blues," was released; the other tracks appeared on various compilations over the next four decades. Although it sold respectably, the single didn't gather enough attention to earn him another session with Parrot. In early 1954, King returned to Osceola and re-joined the In the Groove Boys; he stayed in Arkansas for the next two years.

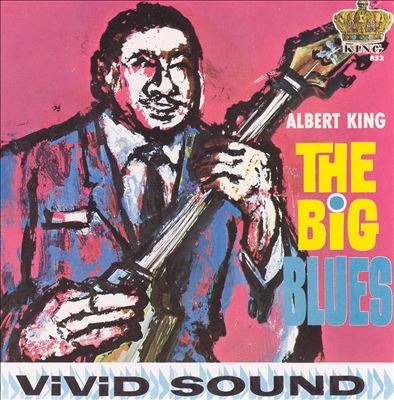

In 1956, Albert moved to St. Louis, where he initially sat in with local bands. By the fall of 1956, King was headlining several clubs in the area. King continued to play the St. Louis circuit, honing his style. During these years, he began playing his signature Gibson Flying V, which he named Lucy. By 1958, Albert was quite popular in St. Louis, which led to a contract with the fledgling Bobbin Records in the summer of 1959. On his first Bobbin recordings, King recorded with a pianist and a small horn section, which made the music sound closer to jump blues than Delta or Chicago blues. Nevertheless, his guitar was taking center stage, and it was clear that he had developed a unique, forceful sound. King's records for Bobbin sold well in the St. Louis area, enough so that King Records leased the "Don't Throw Your Love on Me So Strong" single from the smaller label. When the single was released nationally late in 1961, it became a hit, reaching number 14 on the R&B charts. King Records continued to lease more material from Bobbin -- including a full album, Big Blues, which was issued in 1963 -- but nothing else approached the initial success of "Don't Throw Your Love on Me So Strong." Bobbin also leased material to Chess, which appeared in the late '60s.

Albert King left Bobbin in late 1962 and recorded one session for King Records in the spring of 1963, which was much more pop-oriented than his previous work; the singles issued from the session failed to sell. Within a year, he cut four songs for the local St. Louis independent label Coun-Tree, which was run by a jazz singer named Leo Gooden. Though these singles didn't appear in many cities -- St. Louis, Chicago, and Kansas City were the only three to register sales -- they foreshadowed his coming work with Stax Records. Furthermore, they were very popular within St. Louis, so much so that Gooden resented King's success and pushed him off the label.

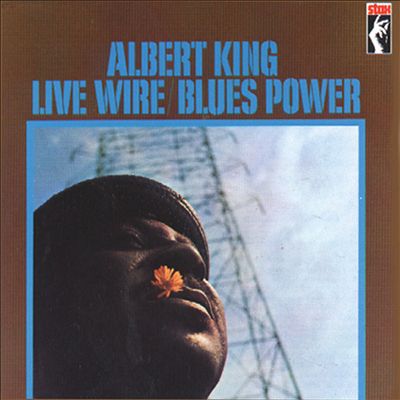

Following his stint at Coun-Tree, Albert King signed with Stax Records in 1966. Albert's records for Stax would bring him stardom, within both blues and rock circles. All of his '60s Stax sides were recorded with the label's house band, Booker T. & the MG's, which gave his blues a sleek, soulful sound. That soul underpinning gave King crossover appeal, as evidenced by his R&B chart hits -- "Laundromat Blues" (1966) and "Cross Cut Saw" (1967) both went Top 40, while "Born Under a Bad Sign" (1967) charted in the Top 50. Furthermore, King's style was appropriated by several rock & roll players, most notably Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, who copied Albert's "Personal Manager" guitar solo on the Cream song, "Strange Brew." Albert King's first album for Stax, 1967's Born Under a Bad Sign, was a collection of his singles for the label and became one of the most popular and influential blues albums of the late '60s. Beginning in 1968, Albert King was playing not only to blues audiences, but also to crowds of young rock & rollers. He frequently played at the Fillmore West in San Francisco and he even recorded an album, Live Wire/Blues Power, at the hall in the summer of 1968.

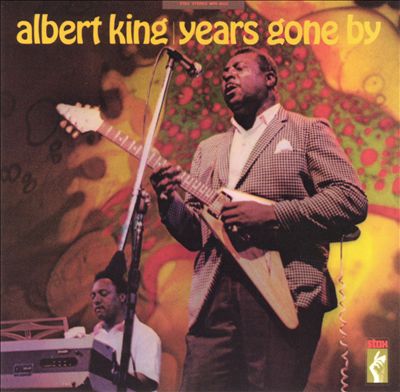

Early in 1969, King recorded Years Gone By, his first true studio album. Later that year, he recorded a tribute album to Elvis Presley (Blues for Elvis: Albert King Does the King's Things) and a jam session with Steve Cropper and Pops Staples (Jammed Together), in addition to performing a concert with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. For the next few years, Albert toured America and Europe, returning to the studio in 1971, to record the Lovejoy album. In 1972, he recorded I'll Play the Blues for You, which featured accompaniment from the Bar-Kays, the Memphis Horns, and the Movement. The album was rooted in the blues, but featured distinctively modern soul and funk overtones.

By the mid-'70s, Stax was suffering major financial problems, so King left the label for Utopia, a small subsidiary of RCA Records. Albert released two albums on Utopia, which featured some concessions to the constraints of commercial soul productions. Although he had a few hits at Utopia, his time there was essentially a transitional period, where he discovered that it was better to follow a straight blues direction and abandon contemporary soul crossovers. King's subtle shift in style was evident on his first albums for Tomato Records, the label he signed with in 1978. Albert stayed at Tomato for several years, switching to Fantasy in 1983, releasing two albums for the label.

In the mid-'80s, Albert King announced his retirement, but it was short-lived -- Albert continued to regularly play concerts and festivals throughout America and Europe for the rest of the decade. King continued to perform until his sudden death in 1992, when he suffered a fatal heart attack on December 21.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/albert-king

Albert King

Bluesman Albert King was one of the premier electric guitar stylists of the post-World War II period. By playing left- handed and holding his guitar upside-down (with the strings set for a right-handed player), and by concentrating on tone and intensity more than flash, King fashioned over his long career, a sound that was both distinctive and highly influential. He was a master of the single-string solo and could bend strings to produce a particularly tormented blues sound that set his style apart from his contemporaries.

King was also the first major blues guitarist to cross over into modem soul; his mid- and late 1960s recordings for the Stax label, cut with the same great session musicians who played on the recordings of Otis Redding, Sam & Dave,Eddie Floyd, and others, appealed to his established black audience while broadening his appeal with rock fans. Along with B.B. King (no relation, though at times Albert suggested otherwise) and Muddy Waters, King helped nurture a white interest in blues when the music needed it most to survive.

King was born in Indianola, Mississippi and taught himself how to play on a homemade guitar. Inspired by Blind Lemon Jefferson, King quit singing in a family gospel group and took up the blues. He worked around Osceola, Arkansas, with a group called the In the Groove Boys before migrating north and ending up in Gary, Indiana, in the early 1950s. For a while, King played drums behind bluesman Jimmy Reed. In 1953, King convinced Parrot label owner Al Benson to record him as a blues singer and guitarist. That year King cut "Bad Luck Blues" and "Be On Your Merry Way" for Parrot. Because King received little in the way of financial remuneration for the record, he left Parrot and eventually moved to St. Louis, where he recorded for the Bobbin and the King labels. In 1959 he had a minor hit on Bobbin with "I'm a Lonely Man." King's biggest release, "Don't Throw Your Love on Me So Strong," made it to number 14 on the R&B charts in 1961.

King didn't become a major blues figure until after he signed with Stax Records in 1966. Working with producer-drummer Al Jackson, Jr., guitarist Steve Cropper, keyboards ace Booker T. Jones, and bass player Donald "Duck"Dunn, better known as Booker T. and the MG's, King created a blues sound that was laced with Memphis soul strains. Although the blues were dominant on songs such as"Laundromat Blues" and the classic "Born Under A Bad Sign", the tunes had Memphis soul underpinnings that gave King his crossover appeal. A collection of these singles were compiled onto an LP in 1967, and it proved to be an important recording in modern Blues history. Titled, "Born Under A Bad Sign," this performance is still quite impressive forty years after its release, a testament to Albert King’s talent and pivotal in the career of the bluesman. He was finally getting the attention and recognition he deserved.

Not only was he the first blues artist to play the legendary San Francisco rock venue the Fillmore West, but he was also on the debut bill, sharing the stage opening night in1968 with Jimi Hendrix and John Mayall. King went on to become a regular at the Fillmore; his album "Live Wire/Blues Power" was recorded there in 1968.King was also one of the first bluesman to record with a symphony orchestra: in1969 he performed with the St. Louis Symphony, triumphantly bringing together the blues and classical music, if only for a fleeting moment.

During the 1970s King toured extensively, often playing to rock and soul crowds. He left Stax in 1974 to record for independent labels like Tomato and Fantasy. King was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Hall of Fame in 1983.

He continued recording and touring throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, playing festivals and concerts, often with B.B. King.

He died of a heart attack in 1992, just prior to starting a major European tour.

Source: James Nadal

Gear

Gibson Flying V

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_King

Albert King

Albert Nelson (April 25, 1923 – December 21, 1992), known by his stage name Albert King, was an American blues guitarist and singer whose playing influenced many other blues guitarists. He is perhaps best known for the popular and influential album Born Under a Bad Sign (1967) and its title track. He, B.B. King, and Freddie King, all unrelated, were known as the "Kings of the Blues".[2] The left-handed King was known for his "deep, dramatic sound that was widely imitated by both blues and rock guitarists."[3]

He was once nicknamed "The Velvet Bulldozer" because of his smooth singing and large size–he stood taller than average, with sources reporting 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) or 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m), and weighed 250 lb (110 kg)–and also because he drove a bulldozer in one of his day jobs early in his career.[4][5]

King was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1983. He was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013. In 2011, he was ranked number 13 on Rolling Stone's 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.[6]

Early life

Albert King was born on a cotton plantation in Indianola, Mississippi. During childhood he sang at a church with a family gospel group, in which his father played the guitar. One of 13 children, he grew up picking cotton on plantations near Forrest City, Arkansas, where the family moved when he was eight years old.[3]

King's identity was a longtime source of confusion. He stated in interviews that he was born in Indianola on April 25, 1923 (or 1924), and was a half-brother of B.B. King (an Indianola native) but, documentation suggests otherwise. King stated that whenever he performed at Club Ebony in Indianola, the event was celebrated as a homecoming, and he cited the fact that B.B.'s father was named Albert King.[3] However, when he applied for a Social Security card in 1942, he gave his birthplace as "Aboden" (most likely Aberdeen, Mississippi) and signed his name as Albert Nelson, listing his father as Will Nelson.[3] Musicians also knew him as Albert Nelson in the 1940s and early 1950s.

He started using the name Albert King in 1953 as an attempt to be associated with B.B King; he was billed as "B.B. King's brother".[3] He also used the same nickname as B.B King, "Blues Boy", and he named his guitar Lucy (B.B. King's guitar was named Lucille).[3] B.B. King later said: "He called his guitar 'Lucy,' and for a while he went around saying he was my brother. That bothered me until I got to know him and realized he was right; he wasn't my brother in blood, but he sure was my brother in the blues."[7]

According to King, his father left the family when Albert was five, and when he was eight he moved with his mother, Mary Blevins, and two sisters to an area near Forrest City, Arkansas.[5] He said his family had also lived in Arcola, Mississippi, for a time. He made his first guitar out of a cigar box, a piece of a bush, and a strand of broom wire. He later bought a real guitar for $1.25.[5] As a left-hander learning guitar on his own, he turned his guitar upside down. He picked cotton, drove a bulldozer, worked in construction, and held other jobs until he was able to support himself as a musician.[3]

Career

King began his professional work as a musician with a group called the Groove Boys in Osceola, Arkansas.[4] During this time he was exposed to the work of many Delta blues artists, including Elmore James and Robert Nighthawk.[2]

In 1953, he moved north to Gary, Indiana where he briefly played drums in Jimmy Reed's band and on several of Reed's early recordings.[8] In Gary, he recorded his first single ("Bad Luck Blues" backed with "Be On Your Merry Way"), for Parrot Records.[9] The record sold a few copies, but made no significant impact and Parrot did not request any follow-up records or sign King to a long-term contract.[4] In 1954, he returned to Osceola and re-joined the Groove Boys for two years.

In 1956, he moved to Brooklyn, Illinois, just across the river from St. Louis, and formed a new band.[10] He became a popular attraction around the St. Louis nightclub scene alongside Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm and Chuck Berry.[11] He signed to Little Milton's Bobbin label in 1959,[12] releasing a few singles, but none of them charted. However, he caught the attention of King Records which released the single "Don't Throw Your Love on Me So Strong" in November 1961. The recording features musician Ike Turner on piano and became King's first hit; peaking at number 14 on the Billboard R&B chart.[13] The song was included on his first album The Big Blues in 1962. King left Bobbin in late 1962 and recorded one session for King Records. In 1963, He signed with jazz artist Leo Gooden's Coun-Tree label and cut two records for them, but these failed to chart.[14]

With no apparent career prospects other than touring the club circuit in the South and Midwest, King moved to Memphis, where he signed with the Stax record label.[4] Produced by Al Jackson Jr., King with Booker T. & the MGs recorded dozens of influential sides, such as "Crosscut Saw" and "As the Years Go Passing By".[15] In 1967, Stax released the album Born Under a Bad Sign, a collection of the singles King recorded at Stax.[4] The title track of that album (written by Booker T. Jones and William Bell) became King's best-known song and has been covered by several artists (including Cream, Paul Rodgers, Homer Simpson, and Jimi Hendrix). The production of the songs was sparse and clean and maintained a traditional blues sound while also sounding fresh and thoroughly contemporary. The key to King's success at Stax was giving his songs an upbeat, slick R&B feel that made the songs more appealing and radio-friendly than the slow, maudlin traditional blues sound.

In 1967, King was performing at Ike Turner's Manhattan Club in East St. Louis when promoter Bill Graham offered him $1,600 to play three nights at the Fillmore West in San Francisco.[16][17] He released the album Live Wire/Blues Power from one of the concerts.[8]

In 1969, King performed live with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. That same year, he released the album Years Gone By. In 1970, he released an Elvis Presley tribute album, Albert King Does the King's Things. It was a collection of Presley's 1950s hits reworked and re-imagined in King's musical style, although critics felt the results were mixed.

On June 6, 1970, King joined the Doors on stage at the Pacific Coliseum in Vancouver, Canada. Recordings of this performance were released in 2010 by Rhino Records as Live in Vancouver 1970.[18]

In 1971, he released the album Lovejoy which notably includes a cover of the Rolling Stones' hit "Honky Tonk Women". To retain his popular appeal, King eagerly embraced the new sound of funk. In 1972, he recorded "I'll Play the Blues for You", which featured accompaniment from the Bar-Kays, the Memphis Horns, and the Movement (Isaac Hayes's backing group).[8] He recorded another album with the Bar-Kays, I Wanna Get Funky (1974). He also made a cameo on an Albert Brooks' comedy album, A Star Is Bought (1975).[19]

In 1975, King's career took a turn downward when Stax Records filed for bankruptcy, after which he moved to the small Utopia label. His next two albums, Albert and Truckload of Lovin' (1976), devolved into generic 1970s pop music. His third album for Utopia, King Albert (1977), while somewhat more subdued, still lacked any standout material, and King's guitar took a backseat to the background instruments. Clara McDaniel teamed up with King at Ned Love's Club. This led to her touring with King in the Deep South in the 1970s.[20][21] When McDaniel returned home she managed King's fleet of taxicabs. The last recording King made for Utopia was Live Blues in 1977, from his performance at the Montreux Jazz Festival. The track "As the Years Go Passing By" is noteworthy for his duet with the Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher.[22]

In 1978, King moved to a new label, Tomato Records, for which he recorded the album New Orleans Heat. The label paired him with the R&B producer Allen Toussaint, who had been responsible for scores of hits in that genre in the 1960s and 1970s but was a novice at working with blues artists. The album was a mix of new songs (including Toussaint's own "Get Out of My Life, Woman") and re-recordings of old material, such as "Born Under a Bad Sign".

King took a four-year break from recording after the disappointing sales of his albums in the late 1970s. During this period, he re-embraced his roots as a blues artist and abandoned any arrangements except straight 12-bar guitar, bass, drums, and piano. In 1983, he released a live album for Fantasy Records, San Francisco '83, which was nominated for a Grammy Award.[23] The same year he recorded a studio television session, more than an hour long, for CHCH Television in Canada, featuring the up-and-coming blues sensation Stevie Ray Vaughan; it was subsequently released as an audio album and later as an audio album plus DVD titled In Session.

In 1984, King released the album, I'm in a Phone Booth, Baby, which was nominated for a Grammy Award.[23] The album included a redo of "Truckload of Lovin'" and two old songs by Elmore James, "Dust My Broom" and "The Sky Is Crying".

King's health problems led him to consider retirement in the 1980s, but he continued regular tours and appearances at blues festivals, using a customized Greyhound tour bus with "I'll Play The Blues For You" painted on the side.[4] His final album, Red House (named after the Jimi Hendrix song) was released in 1991.

At the time of his death, he was planning a tour with B.B. King and Bobby "Blue" Bland.[11] Bland told the Associated Press, "there was never any type of jealousy when we three worked together on a package. One just pushed the others."[24]

Death

King died of a heart attack on December 21, 1992, in his Memphis home.[11] His final concert had been in Los Angeles two days earlier. He was given a funeral procession with the Memphis Horns playing "When the Saints Go Marching In" and was buried in Paradise Gardens Cemetery in Edmondson, Arkansas, near his childhood home.[25]

King was survived by his wife, Glendle; two daughters, Evelyn Smith and Gloria Randolph; a son, Donald Randolph; a sister, Elvie Wells; 8 grandchildren, and 10 great-grandchildren.[11]

Artistry

Instruments

King's first instrument was a diddley bow. Next, he built himself a cigar box guitar, and eventually he bought a Guild acoustic guitar. The instrument he is usually associated with is a 1958 Gibson Flying V. In 1974 he began using a Flying V built by Dan Erlewine, and after 1980 he also played one built by Bradley Prokopow.[26] After 1987, Albert played a custom Archtop Flying V,[27] built by Tom Holmes upon commission from Billy Gibbons, it was given to King for his 65th birthday. Around 2017, this guitar was sold by Gruhn's guitar[28] to an unknown collector.

King was left-handed, but usually played right-handed guitars flipped over upside-down. He used a dropped open tuning, possibly more than one, as reports vary: (C#-G#-B-E-G#-C#) or open E-minor (C-B-E-G-B-E) or open F (C-F-C-F-A-D).[29] Steve Cropper (who played rhythm guitar on many of King's Stax sessions), told Guitar Player magazine that King tuned his guitar to C-B-E-F#-B-E (low to high).[30] The luthier Dan Erlewine said King tuned to C-F-C-F-A-D with light-gauge strings (0.050", 0.038", 0.028", 0.024" wound, 0.012", 0.009"). The lighter-gauge strings, and lower string tension of the dropped tuning, were factors in King's string-bending technique.

For amplification, King used a solid-state Acoustic amplifier, with a speaker cabinet containing two 15-inch speakers and a horn ("which may or may not have been operative"). Later in his career he also used an MXR Phase 90.[26]

Influence

King influenced other guitarists, including Jimi Hendrix, Mick Taylor, Derek Trucks, Warren Haynes, Mike Bloomfield and Joe Walsh (the James Gang guitarist spoke at King's funeral). He also influenced his contemporaries Albert Collins and Otis Rush. He was often cited by Stevie Ray Vaughan as having been his greatest influence. Eric Clapton has said that his work on the 1967 Cream hit "Strange Brew" and throughout the album Disraeli Gears was inspired by King.[24]

Accolades

Over the course of his career, King was nominated for two Grammy awards. In 1983, he was nominated for Best Traditional Blues album for San Francisco '83 and the next year he was also nominated for I'm In A Phone Booth, Baby.[23]

In 1983, King was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame.[3]

King received a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame in 1993.[31]

In 2011, King was honored with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail in his hometown Indianola.[3][32]

King was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013.[33] At the induction ceremony, Gary Clark Jr. performed King's "Oh, Pretty Woman" and was then joined by John Mayer and Booker T. Jones to perform King's "Born Under a Bad Sign".[34]

King was inducted into the Memphis Music Hall of Fame in 2013.[5]

Discography

Studio albums

- The Big Blues, also known as Travelin' to California (1962)

- Born Under a Bad Sign (1967)

- Years Gone By (1969)

- Blues for Elvis – King Does the King's Things (1970)

- Lovejoy (1971)

- I'll Play the Blues for You (1972)

- I Wanna Get Funky (1974)

- Albert (1976)

- Truckload of Lovin' (1976)

- King Albert (1977)

- The Pinch, also known as The Blues Don't Change (1977)

- New Orleans Heat (1978)

- San Francisco '83, also known as Crosscut Saw: Albert King in San Francisco (1983)

- I'm in a Phone Booth, Baby (1984)

- The Lost Session (1971, released 1986)

Videography

- Maintenance Shop Blues (VHS), PBS (1981)

- Godfather of the Blues: His Last European Tour (DVD), P-Vine Records (2001)

- Live in Sweden, Image Entertainment (2004)

- In Session... Albert King with Stevie Ray Vaughan, Stax, Concord Music Group (2010)

External links

- Albert King at Rolling Stone

- The Big Blues, Alan di Perna, Guitar Aficionado, February 2013

https://www.guitarworld.com/artists/celebrating-life-and-legacy-guitar-giant-albert-king

Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Guitar Giant Albert King

Albert King was a giant among bluesmen, and not only for his immense talents on the guitar. A 250-pound giant of considerable bulk, King stood between six-four and six-seven and made any guitar he held in his massive hands look like a child’s plaything.

But the notes and tones he tore from the instrument were anything but small. In the middle years of the 20th century, King grabbed hold of a Gibson Flying V and boldly went where no blues guitar player had gone before, or has gone since.

A left-hander, he flipped a right-handed guitar upside down, put it in an unorthodox tuning, and forged a style steeped in steely drama and epic note-bends that evoke the vertiginous blood rush of powerful emotions.

King’s impact on the blues and rock guitar legacy is prodigious. Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield, Jimi Hendrix, and Stevie Ray Vaughan have been among his greatest admirers. Each drafted huge chunks of King’s fiercely original style into his own playing. Clapton famously nicked the solo from King’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” and inserted it in “Strange Brew” from Cream’s wildly influential 1967 album, Disraeli Gears.

Jimi Hendrix cited King’s “Crosscut Saw” as one of his favorite tunes. Mike Bloomfield covered Albert’s “Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong,” and Cream recorded their own version of King’s signature tune, “Born Under a Bad Sign.” As for Stevie Ray Vaughan, he outdid his King-crazed predecessors by recording an In Session television special with his hero in 1983.

His influence on many of the world’s most revered guitarists is sufficient to make him a national treasure of American music. But in many ways, his own achievements outshine those of his acolytes. After all, he did it first. And he certainly did it his way.

True to his name, King is arguably the monarch of upside-down-lefty guitarists, a distinguished company that includes Otis Rush, Doyle Bramhall II, Elizabeth Cotton, and Coco Montoya in the blues-folk realm, and everyone from Babyface to Bob Geldof in other genres.

The barbed-wire minimalism of King’s searing leads makes an ideal counterpoint to his husky, gospel-inflected vocal style. It’s a true call-and-response passion play. King was nicknamed the Velvet Bulldozer, a name that resonates once you realize that he once made his living driving a bulldozer. Albert King lived the blues. That’s why he played and sang them so beautifully.

He had a remarkably wide perspective on the blues as well, crossbreeding more traditional 12-bar forms with everything from sweet Stax soul to big-band balladry. Like a lot of left-hand/right-brain creatives, Albert King didn’t play by any rulebook but his own, nor would he suffer fools gladly. Possessed of a notoriously bad temper, he would lay into band members onstage if things weren’t going his way. In one famous public display of anger, he chewed out John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, who were backing him, for playing too loud.

Luthier Dan Erlewine, who made King one of the Flying V guitars that he played throughout his career, had a few occasions to witness the Velvet Bulldozer in high dudgeon.

“The first time Albert was playing at the Grande Ballroom, I was backstage after the show,” Erlewine says, referring to Detroit’s legendary Sixties rock venue, just a few miles from the bridge to Windsor, Ontario. “And Albert was pissed at the promoters, who were trying to pay him with Canadian bills. He wouldn’t take them. ‘I don’t want none of that funny money,’ he said. And they got him want he wanted.”

King was known to pack a gun, so people were reluctant to cross him. But his hot temper was only one aspect of a complex and gifted artist. Erlewine puts the anger down to a combination of impatience and competitiveness. “I’d say Albert was more competitive than some, certainly more so than the older folks out there, like [his blues contemporaries] Mance Lipscomb and Johnny Shines. As a person, though, Albert had a softness and kindness inside. But he kept it hidden a lot.”

Along with B.B. and Freddie, Albert King is one of the three kings of the blues, although the man born Albert Nelson was related to neither of those great bluesmen by blood. He was, however, born in the same place as B.B. King—Indianola, Mississippi—on April 25, 1923. While he may not have literally been born under a bad sign, his birth date does put Albert King in the contentious and creative zodiacal house of Taurus. Later in life, he would assume the regal surname King as a stage name, some say in homage to B.B. King.

The family moved to Forrest City, Arkansas, when Albert was eight. He spent some time as an agricultural laborer, picking cotton, but set his sights on making a life for himself in music early on. He once joked that he didn’t learn from studying any other guitarists, saying, “Everything I do is wrong.” But that isn’t strictly accurate. King also spoke often of being influenced by Lonnie Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Elmore James.

“I listened to the slide guitar of Elmore James and a couple of more people I knew way back there,” he told one interviewer. “Then along came T-Bone Walker, and that did it. So I just mixed it all together, and I couldn’t get it exactly like they had it, but I just put my own thing to it.”

It may have been the open slide-guitar tunings of players like Jefferson and James that inspired King’s own use of alternate tunings. He is mainly associated with an E minor tuning (low to high, C B E G B E). But he also tuned to the same intervals in both C# and D. He was known to use open F (low to high, C F C D A D) as well.

For guitarists accustomed to playing in standard, none of these tunings are as intuitive as, say, open G or E. But remember that Albert King was holding a right-handed electric guitar the “wrong” way around. This yields a different perspective on the instrument, one that is, in a way, more in tune with nature, with the low strings closer to the ground and the high strings nearer to the sky. But even upside down, some of King’s open tunings are mighty strange, which also accounts for the unique beauty embodied in some of his phrasing.

“I knew I was going to have to create my own style,” he told guitar journalist Dan Forte, “because I couldn’t make the changes and chords the same as a right-handed man could. I play a few chords, but not many. I always concentrated on my singing guitar sound—more of a sustained note.”

King also enjoyed what’s known as the “lefty advantage” when it comes to bending notes. With the strings’ vertical arrangement flipped, you bend notes on the critical higher-pitched strings by pulling the string downward, which is much easier than pushing upward to execute a bend. King exploited this capacity to particularly dramatic effect, sometimes bending notes as much as four tones up. His huge hands were another factor in this aspect of his style, as was the slackness of the strings in the low-slung tunings Albert favored.

As if all this weren’t unconventional enough, King didn’t use a pick. He mainly used his thumb to pluck the notes. But his first finger would also sometimes come into play in helping shape the steely pinched tones that are another hallmark of his style. “I never could hold a pick in my hand,” King explained to Forte. “I had started out playing with one, but I’d be really gettin’ into it, and after a while the pick would sail across the room. I said, ‘To hell with this.’ So I just play with the meat of the thumb.”

The core elements of King’s riveting style are all evident, albeit embryonically, on his first recording, “Bad Luck Blues,” recorded in Chicago in 1953 for Parrot Records. By the time he cut this disc, King had paid plenty of dues, singing lead tenor with gospel quartet the Harmony Kings, fronting his own group—the Groove Boys—in Osceola, Arkansas, and playing drums for seminal blues guitarist and singer Jimmy Reed. But “Bad Luck Blues” lived up to its name by not providing King with the hit he might have been hoping for.

He didn’t score big until eight years later, when he released “Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong” in 1961. The record climbed to Number 14 on the R&B charts and put Albert King on the map. It also became a featured track on his very first album, The Big Blues, in 1962. A study in pinched, plucked passion, the lead guitar intro to “Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong” makes it clear from the start that Albert King ain’t about to do things in a small way. This is the lowdown slow blues at its finest, and the guitar-and-vocal interplay is exquisite. King’s biting leads alternate with a vocal performance that scales the full emotional range, from a mournful croon to a high-pitched gospel wail. The symbiotic relationship between King’s guitar and voice is one of the blues’ greatest treasures.

By the time the disc was released, King had found his instrument: a 1958 korina wood Gibson Flying V. There has been much speculation as to why he favored this particular guitar, but upside-down lefties tend to seek out instruments with symmetrically shaped bodies and headstocks, as they look much less awkward when flipped. And among symmetrically shaped guitars, a Flying V certainly has far more flash and panache than, say, an SG or 335. Along with Lonnie Mack, King was one of the earliest guitarists to popularize Gibson’s angular, V-shaped masterpiece.

Like many archetypal bluesmen, King was often on the move, particularly in the early phases of his career. By 1966, he was down in Memphis and had been signed to Stax, the premier mid-Sixties R&B label, then riding high with hits by Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Rufus Thomas, Carla Thomas, Eddie Floyd, and Wilson Pickett. The marriage of King’s 12-bar blues with the funky Stax backbeat is a true revelation on his 1967 hit, “Born Under a Bad Sign.” On it, he is supported solidly by Booker T. & the MGs and the Memphis Horns as well as Isaac Hayes, whose piano vamp sets the groove strutting at a pimp-crawlin’ pace. The deep, dark Memphis Horns reinforce the driving bass line, and funky off-beats walk up to the V chord. King’s guitar sounds crisper and more incisive than ever, his voice plumbing the desperate depths of this ultimate hard-luck narrative.

Stax had one of the greatest-sounding recording rooms of the period as well as a brilliant pool of staff musicians, producers, and tunesmiths, including Hayes and Booker T. & the MGs, consisting of organist Booker T. Jones, guitarist Steve Cropper, bassist Duck Dunn, and drummer Al Jackson Jr. It was at Stax that King’s maverick talent found an ideal home. His Stax years yielded the lion’s share of his signature recordings, including “Laundromat Blues,” “Crosscut Saw,” “Personal Manager,” and “As the Years Go Passing By,” all of which were collected on King’s first album for Stax, also titled Born Under a Bad Sign.

This was a new sound in the blues: urgently contemporary, no mere exercise in the kind of purist reconstructionism that had come into vogue at the time. The Stax tracks helped King cross over to a wider audience than he’d ever reached before.

By this point, his original 1958 Flying V had gone missing, allegedly lost by the guitarist in a game of craps. It was replaced by a 1966 Flying V presented to King by Gibson. This instrument accompanied the guitarist onto the stage for his many appearances at Bill Graham’s legendary Fillmore venues in San Francisco and New York City. These shows found King sharing bills with rock and blues titans like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, the Byrds, the Allman Brothers Band, Van Morrison, and B.B. King. After years of hard work, Albert King found an appreciative audience among the era’s blues-crazed rock fans.

One of these incendiary Fillmore nights was captured on King’s seminal live album Live Wire/Blues Power. In many ways, King is best understood through his live recordings. The spontaneity and uninhibited abandon of live performance, as compared with studio recordings, seemed particularly suited to the man’s blues muse.

But one aspect of King’s work that typically drew a puzzled response from his new young fans was his love of schmaltzy balladry. His cover of the American songbook standard “The Very Thought of You” that closes Born Under a Bad Sign was easily the disc’s most frequently skipped-over track. It probably still is, for that matter. But King refused to conform to anyone’s notion of what he, or the blues, should be. In 1969, he performed with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Why shouldn’t a bluesman have full symphonic backing? Albert King was the first to go there. And why shouldn’t a bluesman record an album of Elvis Presley covers, should the mood take him? Albert went there too with 1970’s Blues for Elvis: King Does the King’s Thing.

In the early Seventies, King acquired his third iconic Flying V, the instrument custom-built by Dan Erlewine. This was his only truly left-handed guitar, with the tone controls and output jack on what would be the lower bout for King. With his previous, flipped-over right-handed Vs, the volume tone controls were awkwardly located on the upper bout. Erlewine recalls King mentioning that it was annoying for him to reach up to adjust his tone or volume. “That was one of the reasons he wanted a lefty,” he explains. “He also wanted his name on the fretboard in pearl and abalone, so it would flash under the lights.”

Fashioned from a 125-year-old piece of black walnut, this guitar would be King’s main ax from 1972 until his passing, 20 years later. Nineteen seventy-two was an especially good year for King, witnessing the release of another landmark recording, “I’ll Play the Blues for You,” a soulful minor-key outing much in the vein of B.B. King’s “The Thrill Is Gone.” On “I’ll Play the Blues for You”—both the song and entire album of the same name—Albert is backed by members of two other great Stax outfits, the Bar-Kays and Isaac Hayes’ backing group, the Movement.

King stuck with Stax throughout the company’s decline in the early Seventies, moving on to several other labels after the company went bankrupt in 1975. His Seventies recordings didn’t have quite the same impact as his Sixties work, although there are some fine tracks to be discovered among the 10 or so albums that King released between 1970 and 1978. And while King remained active as a recording and touring artist throughout the Seventies, he began to slow down in the Eighties, moving into semiretirement from the studio but continuing to play select festivals and other live dates. Constant touring under far less than five-star circumstances was one of the things said to exacerbate the guitarist’s irritability and bad temper.

But one very important gig he was able to perform—and which seemed to put him in quite a good mood—was a 1983 date with Stevie Ray Vaughan for the Canadian music television series In Session. It is a true passing-the-torch moment, two guitar legends from very different generations seated comfortably side by side and trading licks on blues standards and some of their own most-loved tracks. Vaughan’s admiration for his six-string idol is palpable, and King really shines in this welcoming environment. The DVD document of the performance is highly recommended.

Fortunately, and unlike many of his peers, King lived to see his work embraced by several generations of blues and rock guitarists. How much this meant to the irascible bluesman is hard to say. At times he seemed more interested in going fishing and smoking his pipe, two of his favorite leisure-time pursuits. But he was a road warrior to the last: Albert King died of a heart attack on December 21, 1992, at age 69. He’d played his last show two days earlier, in Los Angeles.

It was fitting that the Memphis Horns, who had backed King on some of his greatest musical triumphs, accompanied his body on its journey down Beale Street and across the Mississippi River to King’s final resting place in Edmondson, Arkansas. They played “When the Saints Go Marching In.” One likes to think that SRV, Hendrix, Bloomfield, and many of Albert’s other gone-beyond acolytes were lined up to greet him at the Pearly Gates—or whatever serves as the musicians’ entrance to heaven.

This story originally appeared in the March/April 2013 issue of Guitar Aficionado.

https://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/albert-king

Albert King - Indianola

Albert King (1923-1992), who was billed as “King of the Blues Guitar,” was famed for his powerful string-bending style as well as for his soulful, smoky vocals. King often said he was born in Indianola and was a half-brother of B. B. King, although the scant surviving official documentation suggests otherwise on both counts. King carved his own indelible niche in the blues hierarchy by creating a deep, dramatic sound that was widely imitated by both blues and rock guitarists.

Albert King’s readily identifiable style made him one of the most important artists in the history of the blues, but his own identity was a longtime source of confusion. In interviews he said he was born in Indianola on April 25, 1923 (or 1924), and whenever he appeared here at Club Ebony, the event was celebrated as a homecoming. He often claimed to be a half-brother of Indianola icon B. B. King, citing the fact that B. B.’s father was named Albert King. But when he applied for a Social Security card in 1942, he gave his birthplace as “Aboden” (most likely Aberdeen), Mississippi, and signed his name as Albert Nelson, listing his father as Will Nelson. Musicians also knew him as Albert Nelson in the 1940s and ’50s. But when he made his first record in 1953–when B. B. had become a national blues star–he became Albert King, and by 1959 he was billed in newspaper ads as “B. B. King’s brother.” He also sometimes used the same nickname as B. B.–“Blues Boy”–and named his guitar Lucy (B. B.’s instrument was Lucille). B. B., however, claimed Albert as just a friend, not a relative, and once retorted, “My name was King before I was famous.”

According to King, he was five when his father left the family and eight when he moved with his mother, Mary Blevins, and two sisters to the Forrest City, Arkansas, area. King said his family had also lived in Arcola, Mississippi, at one time. He made his first guitar out of a cigar box, a piece of a bush, and a strand of broom wire, and later bought a real guitar for $1.25. As a southpaw learning guitar on his own, he turned his guitar upside down. King picked cotton, drove a bulldozer, did construction, and worked other jobs until he was finally able to support himself as a musician.

King’s first band was the In the Groove Boys, based in Osceola, Arkansas. In the early ’50s he also worked with a gospel group, the Harmony Kings, in South Bend, Indiana, and–as a drummer–with bluesman Jimmy Reed in the Gary/Chicago area. He recorded his debut single for Parrot Records in Chicago before returning to Osceola and then moving to Lovejoy, Illinois. Recordings in St. Louis drew new attention to his talents and a stint with Stax Records in Memphis (1966-1974) put his name in the forefront of the blues. Rock audiences and musicians created a new, devoted fan base, while King’s funky, soulful approach helped him maintain a following in the African American community. Among his most notable records were Live Wire/Blues Power, an album recorded at the Fillmore in San Francisco, and the Stax singles “Born Under a Bad Sign,” “Cross Cut Saw,” “The Hunter,” and “I’ll Play the Blues for You.” King remained a major name in blues and was elected to the Blues Hall of Fame in 1983, but he never enjoyed the commercial success that many of his followers (including Eric Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan) did. He died after a heart attack in Memphis, his frequent base in his final years, on December 21, 1992.

content © Mississippi Blues Commission

Willie Clayton (b. 1956), another Indianola area native who became a prominent performer on the Southern soul and blues circuit, performed on bills with Albert King and, like King, began making homecoming appearances at the Club Ebony.

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/12/23/arts/albert-king-a-master-of-the-blues-is-dead-at-69.html

Albert King, a Master of the Blues, Is Dead at 69

Albert King, a blues guitarist and singer who became a major figure in postwar American music, died on Monday in Memphis, where he lived.

Mr. King, who was 69, died after a heart attack, the N. J. Ford & Sons Funeral Home in Memphis said.

Mr. King was an intense performer, and his sound -- loaded with bent and crying notes -- was among the meanest produced by any bluesman. His solos might consist of only a few positions on the guitar, but he would contort them into wailing, cursing, anguish-filled choruses. He used his smooth voice, made passionate by a steady vibrato, to project doom and authority. He conjured up anger and loss in his songs.

Mr. King was born in Indianola, Miss., and did farm work as a child. His first experiences with music were in the church, and he spent the 1940's doing manual labor and occasionally singing in a family gospel group.

In the early 1950's, he moved north looking for work. In Gary, Ind., Mr. King played drums for Jimmy Reed, who was starting his own career. In 1953, at the suggestion of Muddy Waters, Mr. King made his first recordings, for the Parrot label. On the Blues Circuit

In the mid-1950's he moved to St. Louis, where a flourishing blues scene nurtured Chuck Berry and Ike Turner. There, he put together one of his best bands and became a major figure on the blues circuit, playing exclusively for black audiences.

His career took a radical turn in 1966, when he was signed by the Memphis-based Stax Records. Backed by excellent bands, including Booker T. and the MG's, he made the classic albums "Born Under a Bad Sign" and "Live Wire/Blues Power."

His music changed as well. To stay current, he began recording funk and soul, and the contrast between his acidic guitar work and a funk rhythm section created one of the more distinct sounds in popular music. He became a regular on the rock-and-roll circuit, and white audiences received his music enthusiastically. Guitarists as disparate as Jimi Hendrix, J. J. Cale, Mark Knopfler, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Johnny Winter and Eric Clapton all owe their styles in part to Mr. King.

Mr. King spent the rest of his career touring regularly, working with his own band, capturing a dark, Southern blues sound, and singing and playing with undiminished power. He was planning a European tour with two other blues masters, Bobby (Blue) Bland and B. B. King, who Mr. King said was a distant cousin.

Mr. King is survived by his wife, Glendle, of Lovejoy, Ill.; two daughters, Evelyn Smith of Racine, Wis., and Gloria Randolph of Phoenix; a son, Donald Randolph, of Venice, Ill.; a sister, Elvie Wells of Chicago; 8 grandchildren, and 10 great-grandchildren.

Albert King

Albert King: Born Under A Bad Sign (Stax)

Review by Max Jones, Melody Maker, 8 June 1968

'Born Under A Bad Sign'; 'Crosscut Saw'; 'Kansas City'; 'Oh, Pretty Woman'; 'Down Don't Bother Me'; 'The Hunter'; 'I Almost Lost My Mind'; 'Personal Manager'; ...

Interview by Jim Delehant, Hit Parader, September 1968

As Told To Jim Delehant ...

Albert King: Steve Paul's Scene, New York NY

Live Review by Mike Jahn, The New York Times, 17 October 1968

Albert King, Guitarist, Gives Loud Support to Blues Power ...

Buddy Guy, Albert King, King Curtis: Village Gate, New York City

Live Review by Ian Dove, Billboard, 15 February 1969

NEW YORK — The world of music moves closer as the long-established jazz spot, the Village Gate, took a brief weekend — but possibly regular ...

https://www.antonyscott.com/blogs/axe-legends/why-albert-king-remains-king-of-the-blues

Why Albert King Remains King of the Blues

by Mark Scott

September 6, 2021

Elvis Presley has always been called the King of Rock n’ Roll. However, the title of “King of the Blues” goes to Albert King, an Axe legend guitarist who was perhaps the best-known blues guitarist of the 20th century.

Albert inspired modern instrumental guitar music. He wasn’t just an inspiration to other African American blues musicians like Robert Cray and Otis Rush. He was also an inspiration to white blues musicians like Stevie Ray Vaughan and Eric Clapton. Albert created his own style and tone of blues music that no other musician could duplicate.

“Born Under a Bad Sign” is Albert’s best-known blues album. It features 11 blues song recordings throughout 5 different sessions. When the album first came out in 1967, it didn’t rank in any notable music charts. But as more people have listened to the album over the years, it is now considered one of the best blues albums ever recorded.

Music Style

Albert was a left-handed guitar player on a right-handed guitar setup. He basically pulled the guitar strings upside-down, which would explain why the tone of his guitar-playing sounded so much different. His eventual iconic guitar choice? A Flying V, played upside-down. The resulting sounds were dramatic, emotional, and spiritual all at the same time. Many other guitarists tried to imitate his dramatic guitar style, but they never came close to mimicking Albert’s talent and excellence.

Life and Career

On April 25th, 1923, Albert was born in Indianola, Mississippi, on a cotton plantation under the birth name Albert Nelson. His family soon moved to Forrest City, Arkansas and participated in a gospel group at their local church. He would eventually sing at the church while his father played the guitar. But his father left the family before he could teach him how to play the guitar.

Albert was self-taught, and built his first guitar using an old cigar box. He continued to play gospel at the church until he decided to focus on blues music solely. People noticed his unique style of playing the guitar from the beginning. When Albert got older, he brought his talent into several nightclubs throughout the Arkansas area.

Musicians knew his name was Albert Nelson. But as Albert became more eager to make a name for himself, he started promoting himself under the stage name “Albert King.” It was an effort to look like he was related to B.B. King, who was a more famous Blues musician at the time. Albert told people he was his brother, though he was not actually related in any way.

In the 1950s, Albert became a professional musician after joining the Groove Boys group. This opportunity exposed him to several other blues artists, such as Robert Nighthawk and Elmore James. He moved around a lot during the 1950s, first to Gary, Indiana, and then to Brooklyn, Illinois.

Albert’s first single record was “Bad Luck Blues” for Parrot Records in Gary. Unfortunately, the single record did not generate very many sales. He continued to record songs and perform with notable artists in nightclubs like Chuck Berry and Ike Turner. After Albert recorded the song “Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong” with Ike Turner, it landed on the Billboard R&B chart at number 14.

The 1960s and 1970s were not much better for Albert either. Although he continued to get record deals and give live performances around the country, nothing ever gained him colossal notoriety. Albert went from one record label to another to record songs and albums. To his disappointment, the number of sales was less than satisfying.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that everything turned around for him. Now in his 50s, Albert would record the album “San Francisco ‘83” for Fantasy Records. It would earn him his first Grammy Award nomination and the opportunity to record a studio television session in Canada. That was followed by a second Grammy Award nomination for his next album, “I’m in a Phone Booth, Baby”, in 1984.

Albert had health problems and considered retiring, but he couldn’t walk away from his newfound fame. He went on nationwide tours and performed live at blues festivals for the rest of the decade. On December 21st, 1992, Albert died of a heart attack at his home in Memphis, Tennessee. His death came just two days after he played his last concert in Los Angeles, California.

Albert’s death prompted critics and blues fans to re-evaluate his work. They grew to appreciate his music a lot more after his death than they did during his life. Now he has officially achieved legendary status in the music world.

Awards and Accolades

Albert was the recipient of two Grammy Award nominations. The first nomination came for his work on the album “San Francisco ‘83” under the category of Best Traditional Blues Album. His second nomination came one year later for his next album, “I’m In A Phone Booth, Baby.”

In 1983, Albert was given the honour of getting inducted into the prestigious Blues Hall of Fame. He shared the honour with other blues inductees, including Louis Jordan, Robert Nighthawk, Ma Rainey, and Big Joe Turner. Ten years later, in 1993, Albert was given a star on the Walk of Fame in St. Louis, Missouri.

Albert never got to live long enough to see his induction into the legendary Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013. He joined the ranks of the great legends like James Brown, Ray Charles, Fats Domino, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley.

Check out the new Axe Legend Albert King set!

Albert King: Letting It Roll All Night Long

When Albert King and the trio that accompanies him in live performance take the stage they invariably start things off with an instrumental. Usually it’s a slow shuffle, nice and relaxed in tempo, and Albert keeps things simple on the guitar. In the middle of the number he steps forward and introduces himself and his group and then he smiles at his audience and says, “. . . we’re gonna let it roll all night long.”

There is no loud pickup after he says it. The band just continues to swing easily letting the power of Albert’s guitar continue to gradually elevate the level of tension. And by the time they get to swinging through the last two or three choruses you can hear yourself saying out loud: “Let it roll all night long.”

Albert King is a huge man in his forties. He is Mississippi born, uneducated, and in many ways, an old fashioned bluesman. In live performance he plays a wide range of blues and some pop tunes which emphasize his guitar and voice about equally. His traveling band includes only organ, bass and drums.

I asked Albert about the lack of horns in his live band while he was in Boston for a weekend engagement at the Boston Tea Party, the last weekend of August. The fact is that the absence of horns lessens King’s potential impact on several of his best numbers, including “Born Under A Bad Sign.” Albert would like to have horns and is earning enough money so that he could probably afford them. The problem, as he puts it, is “Horn players fall in love.” He went on to explain that while it is obviously the case that everybody falls in love, horn players fall in love more easily than other people.

“You laugh,” he went on. “It’s the truth. A guitar player goes on road and he misses his girl friend for a while but he manages to get along. A horn player gets, out on the road, plays two or three towns and then he’ll get lonely and next thing you know he’s packed up and left. It’s better not to hire him in the first place.”

When King has traveled with horns in the past he has been very demanding of them. He has upon occasion paid arrangers as much as $150 per song to arrange horn sections for his band’s book. Naturally enough, he expects his men to play the arrangements exactly as written. One could surmise that therein lies another source of potential friction between King and his hornmen.

King does most of his cross country traveling in his own car, a Cadillac. Being on the road so much seems to depress him a good deal. On Saturday night he was scheduled to leave Boston immediately after the last set. The first set that evening didn’t go that well. When I went back stage to talk some more with him he was extremely tense and when I mentioned that the audience had enjoyed what had obviously not been a first rate effort he got angry and said it burns him up when things weren’t right with his music. He continued to talk and it rapidly became apparent that what was really upsetting him was the impending trip, this time to Los Angeles. Albert and his sidemen drive non-stop, each taking a turn at the wheel while the others get as much rest as they can. As soon as Albert started talking about dreaded cross-country drive he started thinking out loud about his eventual retirement.

King has been on the road for ten years. It has taken a lot out of him and he sometimes seems a bit bored. While he would like to slow down the pace of things a bit, he obviously isn’t going to quit now. He’s been kicking around a long time and it is only recently he has acquired an audience that takes more than routine interest in his music. He is earning a decent cut at the boxoffice and has no intention of stopping. “Maybe in three or four years,” he says.

While speaking of his growing audience I asked King how he felt about the interest other musicians had been taking in his music. The subject came up when someone happened to mention Jack Bruce. King didn’t remember who Bruce was so I reminded him that he was the bass player from Cream. “Oh, those guys. They sure work hard. Play mighty good.” I asked what he thought of the obvious influence he has had on Eric Clapton and he replied, “Last time I worked a show with them I teased them about it. They’re real nice.” He was excited about having worked with them.

King’s own favorite guitarist is B. B. King. But he says that lately B. B. has been shucking and you have to go way back in the alley and dig his old stuff to hear him at his best. King’s interests run far beyond blues and other names that are likely to come up in a discussion of music with him include Joe Turner, Count Basie, and Arthur Prysock. King particularly enjoys band vocalists like Prysock who have silky smooth voices.

When King starts rapping he shows himself to be a marvelous raconteur. One of his stories in particular sheds some light on the kind of milieu his particular brand of blues has developed out of. A while back Little Milton and B.B. King did a concert together in Chicago. Milton came out of the concert claiming he was the new “King of the Blues” and that he had dethroned B. B. Soul magazine went so far as to report on Milton’s “coronation.” Albert was touring in the south at the time and got a phone call from Little Milton.

“Albert, I beat B. B. I whupped him.”

“What did you beat him at? Marbles?”

“I whupped him playing the blues and now I’m gonna whup you.”

Milton was obviously interested in promoting his rather lackluster carreer and wanted a “Battle of the Blues” to be held at Chicago’s Regal theatre. The stars were to be B. B. King, Junior Parker, Bobby Bland, Albert King and Count Basie, as well as Milton. Albert agreed to appear on the condition that Milton appear between him and Bobby Bland.

When Albert finished his set he says. . . “I left that stage smoking. You could see the smoke rising. We played mighty good.” Thereafter he and Bobby Bland went upstairs to the Regal’s balcony to watch Milton do his set. When Milton came on the only people applauding were the Little Milton Girls in their Little Milton sweaters. Milton then proceded to run through his half-baked imitations of the other blues greats (Milton is known for his highly derivative styles) to an increasing amount of razzing from Bland. Pretty soon he started futzing around on the stage and before he was halfway through the set he blew the whole thing. Albert reports that Milton was so mad he thinks that he and before he was halfway through the set he blew the whole was so mad he thinks that he and Bland “. . . had some words about it. Strong words.”

Who won the contest? Count Basie, hands down.

King himself is often highly derivative in his approach and prides himself on the fact that he can do Ray Charles’ numbers exactly as Ray does them. Likewise Arthur Prysock. Two songs on Born Under A Bad Sign reflect King’s closeness to the Prysock tradition: “As the Years Go Passing By” and “The Very Thought of You.” The two cuts are King’s best vocal efforts on the album and are reason enough for concluding that King vocally is more at home with the richly melodic type of song common to that style than he is with straight blues or soul. This opinion was confirmed by the fact that “As the Years Go Passing By” was by far the single most moving performance I saw Albert do in the course of six different sets.

King is very happy at Stax. It is not widely known that he tried to get something going at Stax in the early days, back around 1962, when Jim Stewart was running the show single handedly. Nothing came of it but Albert found his way back to Stax about two and a half years ago. Almost all of the material on Born Under A Bad Sign originally appeared as singles, none of which ever really made it. While Al Jackson is the man who works most intimately with Albert, and is credited with being his producer, Albert is supported by everyone at Stax. Steve Cropper does a lot of technical work for King and plays rhythm guitar on many of his recordings. Booker T. does all of the horn arrangements.

King particularly enjoys working with the men at Stax. “Cold Feet,” one of King’s delightful singles, is an instrumental with King’s voice almost mumbling brief comments about how he and the band are just trying to come up with a hit. It seems the song was recorded after a day in the studio during which king was unable to come up with anything of commercial value. Everyone was frustrated and they decided to lay down a simple instrumental. Albert soon got to swearing at his bad luck. Most of what he said had to be taken off the record because it was unfit for AM (or FM) radio. Jim Stewart more or less ran that particular session.

There are two things one realizes after seeing King perform on a good night. The first is that his guitar playing is more limited than his vocal work. The second is that within his limits, Albert King is one of the great contemporary bluesmen.

King’s guitar style is like no other. I asked him who he had learned how to to play from and he answered, “Nobody. Everything I do is wrong.” Indeed, it would seem so. King plays with his thumb, uses a low and unorthodox tuning, and plays a Vshaped Gibson (first brought to the public’s attention by the wham of that “Memphis man,” Lonnie Mack). None of this is normal.

Within the context of the bluesmen who have gotten to be well known with white audiences, Albert’s frequent reliance on a shuffle tempo is also an anomaly. One of his numbers sounds very close to Arthur Smith’s “Guitar Boogie Shuffle” of ten years ago. Albert likes the shuffle (“with a back-beat,” if you please) because it breaks up the set. Albert needs to do that because he likes to linger over the numerous slow blues in his repetoire, the best of which is “Stormy Monday.”

Albert’s approach to this sort of material is very close to B. B.’s. They both rely on the slow buildup in tension with a mounting crescendo from the accompanists. However, Albert has to suffer by comparison, if for no other reason than his organist plays a Farfisa (compared to King’s Hammond) and he lacks the horns which are so important in that that kind of build up. Nonetheless, when King puts everything into it and lets it roll on for a couple of choruses, it achieves the desired results and you can see the people standing up and calling out to him, applauding in the middle of the breaks and clapping in time. He does get to the audience.

In live performance it is “Lucy” and “Born Under A Bad Sign,” two of Albert’s best recordings, that suffer most from the lack of instrumental depth. On the other hand, “As the Years Go Passing By” is somehow simpler and sweeter without the encumbrance of horns and the live version surpasses even the beauty of the studio version. “Kansas City” is also great live. On the record it has one King’s greatest horn arrangements. During the singing the horns lay out of the way but when they get to the instrumental segment they play against the guitar and change the whole direction of the beat. Live, the song is turned into a guitar tour de force and the tricky horn arrangement is forgotten. The result is a wholly different arrangement, but still great. (Although neither Albert nor anyone else has ever really come up to Wilbur Harrison’s “Kansas City.” Little Richard’s version was a whole different song and that’s quite a number too.)

King is not a big one for encores. But if he comes back and plays anything, most likely it will be a shuffle. The same kind of thing that he opened the set with only a bit faster. And if it’s long and it builds just right it’s enough to push the audience over the top. At his best Albert King leaves you wishing he meant it when he said at the beginning, “We’re gonna roll all night long.”

This story is from the October 26th, 1968 issue of Rolling Stone.

http://alanpaul.net/2014/05/an-interview-with-albert-king/

Foto by Kirk West

Let’s take another look at this old story, one of the highlights

of my years at Guitar World. I wrote the intro a few years ago when the

piece ran in Hittin’ the Note.

See many more great rock, blues and country photographs at www.kirkwestphotography.com.

*

Just days after I became the Guitar World Managing Editor in February, 1991, I sat at my desk listening two of my colleagues (“bosses” would have been the word I used at the time) discussing an interview with Albert King, scheduled for the following week in Cleveland. They couldn’t think of anyone up to the task of interviewing the great and ornery bluesman. I shifted my weight, cleared my throat and waited for them to ask if I was interested. When the offer didn’t come, I piped up that King was my favorite guitarist and I would be honored to take the assignment. After a bit of back and forth, the job was mine.

As the day grew near, I became increasingly nervous. I desperately wanted to do a great job and he had a reputation as a tough, mean old man. I once saw him fire a sax player on the bandstand – surely he’d cancel an interview without a second thought. I called his manager just before I left for the airport to verify our arrangements. “I told Albert about it,” he said. “Hopefully he’ll remember and feel like doing it.”

I spent the day at my cousin Stephen’s house in Cleveland, preparing for the interview and growing increasingly edgy. It started to snow, first lightly, then heavily, and I drove to the theater through a pelting blizzard. Albert was playing with Bobby “Blue” Bland and B.B. King on a spinning theater in the round, and I fidgeted throughout his set. Following his performance, I arrived backstage at my appointed hour, praying that I would be granted an audience with the King.

I was brought to a small dressing room, crowded with band members and their lady friends. King shook my hand and pointed to a seat next to him. As we began to talk, he turned to the others and shouted, “Be quiet! I’m doing an interview.” Silence fell over the room and all eyes and ears turned to me. I have never felt younger, whiter, shorter, or more insignificant. Albert leaned forward and extended his long arm directly over my shoulder to get at some popcorn. Leaning close, he smiled, flashing two gold front teeth, and told me to commence my questioning.

For 45 minutes, Albert answered my questions, though when he considered something foolish or misguided, he shot me a look that could freeze a volcano. He was patient, professional – and every bit as intimidating as I could have imagined, which somehow made me happy. His personality fit his music to a tee; no one has ever played the guitar with more authority or focused intent.

King, who died of a heart attack at age 69 on December 21, 1992, was a vastly influential guitarist for many reasons: He played with a raw ferocity that appealed equally to fellow bluesman and younger rockers. He was one of the first black electric bluesmen to cross over to white audiences, and one of the first to adapt his playing to Sixties funk and soul backings, on classics like “Born Under a Bad Sign.” But perhaps King’s ultimate legacy is that he embodied two of guitardom’s most sacred tenets: what you don’t play counts as much as what you do, and speed can be learned, but feeling must come from within. The left-handed guitarist played “Lucy,” his upside-down flying V, with absolute conviction and economy. He could slice through a listener’s soul with a single screaming note, and play a gut-wrenching, awe-inspiring 10-minute solo without venturing above the 12th fret.

I last saw King perform about eight months before his death, at Tramp’s, a mid-sized Manhattan club. Arriving after midnight, I imagined his final set would be brief, even perfunctory, and was dismayed when he came onstage and sat down – his towering, 6’-5” hulk was always such a large part of his stage presence. Was he feeling infirm? I was further shaken up when he began noodling leads around the band’s funky vamp in the wrong key. I began to wonder if my hero had lost it, but then he found his footing, caught the groove and began to soar.

King delivered a stirring, two-and-half hour performance, seeming to gain strength as the night wore on, closing the show at 3:00 AM with a coolly passionate version of “The Sky Is Crying” that will remain forever etched in my mind. I left the club with a renewed conviction that music is not about showing off, or impressing fellow musicians, or anything else other than creating sounds that forge a mystical bond with listeners. It’s something that Albert King did with unsurpassed skill.

Blues legend has it that Mike Bloomfield, lead guitarist of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and for a time the Sixties guitar hero, once engaged Jimi Hendrix in a cutting contest before thousands of screaming fans. Hendrix drew first and unleashed a soaring, cosmic blues attack. As Bloomfield stood transfixed in awe, struggling to plot a response to Hendrix’s brilliant fury, one thought ran like a mantra through his mindæ“I wish I were Albert King… I wish I were Albert King….”

Two decades have passed, and both Bloomfield and Hendrix are gone. But King and his music remain hale and heartyæeven on a blustery Cleveland night some months ago, when brutal winds and two feet of swirling snow made the city inhospitable to man and blues alike. Inside a suburban club, however, a force of nature even more powerful than a blizzard held sway as Albert Kingæall six-feet-five inches of himæstood puffing a pipe, his upside down Flying V looking like a toy guitar in his massive hands. As clouds of smoke billowed from his snarling mouth, the left-handed King ripped off scorching, jagged blues lines.

On that wintry Ohio night it was easy to understand Bloomfield’s desperate invocation of the massive bluesman in his hour of need. And it was equally clear that King has lost little of the of the devastating blues power that has made his playing the standard of excellence for guitarists from Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton to Stevie Ray Vaughan and Gary Moore.

Several nights after the Cleveland show King, resplendent in an open-collared tuxedo, stepped from a limousine in midtown Manhattan. His pipe was still gripped tightly between his teeth, but the on stage snarl was gone. King was all smiles as he headed into a posh nightclub to receive a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation.

“I never really considered myself r&b,” King said. “I’m a bluesman. But there’s nothing like being honored by your peers. There’s also nothing like this.” His gold teeth sparkled in a broad smile as he held up a check for $15,000, his bounty for a lifetime of groundbreaking work.

While King is inarguably a bluesman, his earliest recordings for Bobbin Records (recently re-released on CD by Modern Blues as Let’s Have a Natural Ball) featured hard-swinging big band arrangements. Later, he would record his most influential workæincluding “Born Under a Bad Sign” and “Crosscut Saw”æfor Stax, backed by Booker T and the MGs, the r&b label’s famed house band.

But whatever the musical setting, King’s lead playing has always been

characterized by stinging, river deep tone and a totally identifiable

style, developed as a result of his unorthodox technique. The

left-handed King plays with his guitar held upside down, treble strings

up, which, among other things, causes him to bend his strings down.

“I learned that style myself,” King said. “And no one can duplicate it, though many have tried.”

AP: You’ve recorded a very wide variety of material, much of which has departed from the standard blues formats. How did you arrive at the appropriate approach for any given song?

KING: I did that in the studio. We would come up with different styles to go behind songsæthen I’d do whatever fit. I might try three or four rhythms behind a song, find the one that feels just right and record it. I can hear real good and I never saw the point of limiting what I listened toælots of times I heard new things that surprised me. The guys at Stax [guitarist Steve Cropper, bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, drummer Al Jackson and organist Booker T. Jones, plus the Memphis Horns] were real good for playing with different grooves and helping me find the right one. I liked playing with them because they were good idea peopleæthey’d twist things around into different grooves. It worked real good.

AP: Your guitar style changed noticeably from your early recordings with the Bobbin label to your work with Stax. You didn’t use a much vibrato originally, for instance.

KING: No, I didn’t. I never made a decision to change my style. Some of it I forgot and some of it just automatically changed. Nothing can stay the same forever. I do all of the vibrato with my hand. I don’t use no gadgets or anything. I used to only use Acoustic amps, but I went to a Roland 120 because it’s easier to handle and it puts out for me.

AP: There has always been so much swing to your music. Have you listened to a lot of jazz?

KING: Yes. I’ve always been a lover of jazz – especially big band jazz. On the Bobbin stuff, I used a lot of orchestration and big band arrangements to mix the jazz with the blues. I went for the swinging jazz arrangements and the pure blues guitar.

AP: Your lead guitar has always been very lyrical. Do you think of the guitar as a second voice?

KING: Yes, I do. I play the singing guitar, that’s what I’ve always called it. I also sing along with my notesæit’s how I think about where I’m going.

AP: You don’t play a lot of chords.

KING: No, I play single-note. I can play chords but I don’t like ’em. I don’t have time for them. I’m paying enough people around me to play chords. [Laughs.]

AP: You’re also noted for your tendency to bend two strings at one time.

KING: Yeah. Lots of times I don’t intend to do that but I’m reaching for a bend and bring another one along. My fingers get mixed up, because I don’t practice. When I get through with a concert, I don’t even want to see my guitar for a while.

AP: Have you always felt that way?

KING: No, no. Just lately – in the last four or five years. Since I’ve been really feeling like I want to retire.

AP: You are one the only guitarists I’ve ever heard who will start a song with a bent noteæon “Angel of Mercy,” for instance.