He

signed with Blue Note and recorded three brilliant piano trio albums

from 1955-1956, adding another one for Bethlehem in late 1957. Nicholslanguished

in obscurity after those sessions, though; sadly, just when he was

beginning to find a following among several of the new thing's

adventurous, up-and-coming stars, he was stricken with leukemia and died

on April 12, 1963. In the years that followed, Nichols became a favorite composer in avant-garde circles, with tributes to his sorely neglected legacy coming from artists like Misha Mengelberg and Roswell Rudd. He also inspired a repertory group, called the Herbie Nichols Project, and most of his recordings were reissued on CD.

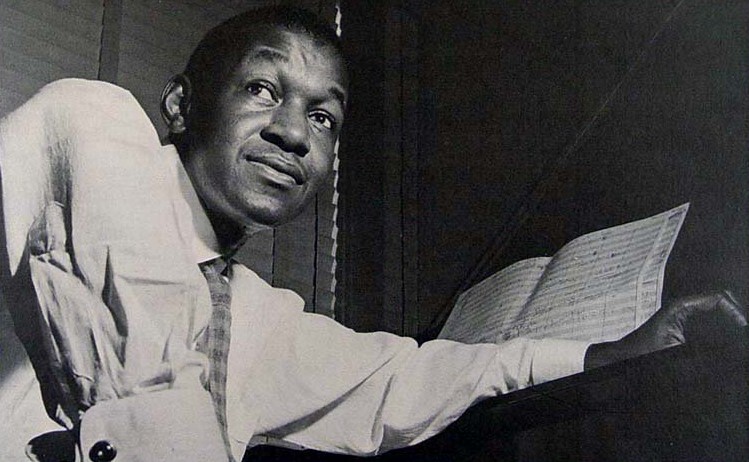

Herbie Nichols

Herbie

Nichols is a perennially neglected jazz pianist and composer. He

recorded less than half of his 170 compositions on three classic trio

albums for Blue Note and one for Bethlehem before dying of leukemia at

the age of 43 in 1963.

He

is often compared to Thelonious Monk, and his piano playing and

compositions certainly do have some of the harmonic angularity people

associate with Monk. But he had a very distinctive sound of his own,

more melancholy and, for lack of a better word, poetic than Monk in many

ways. In fact, Nichols was something of a poet, as the titles to his

tunes suggest. And he was fully Monk's equal in the quality and

individuality of his tunes. He is held in high critical esteem within

jazz, although his tunes are still not widely recorded. Outside of jazz

circles, the only tune of his anyone is likely to know is “The Lady

Sings the Blues,” which Billie Holiday set lyrics to and adopted for the

title of her autobiography.

Nichols

was born in New York in 1919 and died there forty-four years later. In

the course of his brief life he was for a time an associate of Monk's,

though to consequently call his music Monk-like is to do it a grave

disservice. He played with amongst others Milt Larkin and Rex Stewart

out of economic necessity. His own harmonically extraordinary music was

no small distance removed from theirs.

This

is not to imply however that his music amounted merely to an academic

exercise. As it was to be with Andrew Hill some years later, Blue Note

records afforded Nichols an unprecedented opportunity to record his own

music, and he made full use of it, as the three CD set of “The Complete

Blue Note Recordings” shows. The music found here comes exclusively from

his pen and it was recorded in a bout of concentrated recording

activity between May 6, 1955, and April 19, 1956. It was all performed

in the trio setting, and throughout Nichols plays with a variety of

virtuosity that couldn't be included in any jazz curriculum.

As

a player he has capable not only of dark lyricism but also of writing

melodies so harmonically adventurous that they can make the listener

laugh out loud over their audacity. Furthermore, his music was in a

rhythmic league of its own, and Nichols was indeed fortunate in the

drummers he worked with in his brief recording career these Blue Note

sides find him in the company of both Art Blakey and Max Roach.

In

his lifetime Nichols only put out four records under his own name,

three for Blue Note and one for the even smaller Bethlehem label, this

time in the company of Dannie Richmond, Charles Mingus's drummer of

choice. This date offers listeners evidence of his way with a standard

song or two.

The

music of Herbie Nichols is undoubtedly an acquired taste. Whilst he

plowed an individual furrow he did so with clarity of purpose and

vision. The irony of it is that if he were alive today he would probably

have to work outside of music in order to make a living. The passing of

time has moved several steps away from the recording and marketing of

music as idiosyncratic as his. As such, his life was and is a stark

example of the gulf between art and commerce.

Source: Nic Jones

ALL THAT JAZZ

A Too-Brief Glimpse of Herbie Nichols

by DON HECKMAN | SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

Herbie Nichols is one of the forgotten heroes of jazz.

Thirty-four

years after his death in 1963, he continues to be relatively unknown,

even to many serious jazz fans. Sadly, the lack of recognition simply

continues the circumstances of his brief life (he was 44 when he died of

leukemia), since Nichols--despite a prodigious talent as a pianist and

composer--recorded rarely and was obliged to spend a good part of his

life accompanying shows and playing in Dixieland bands.

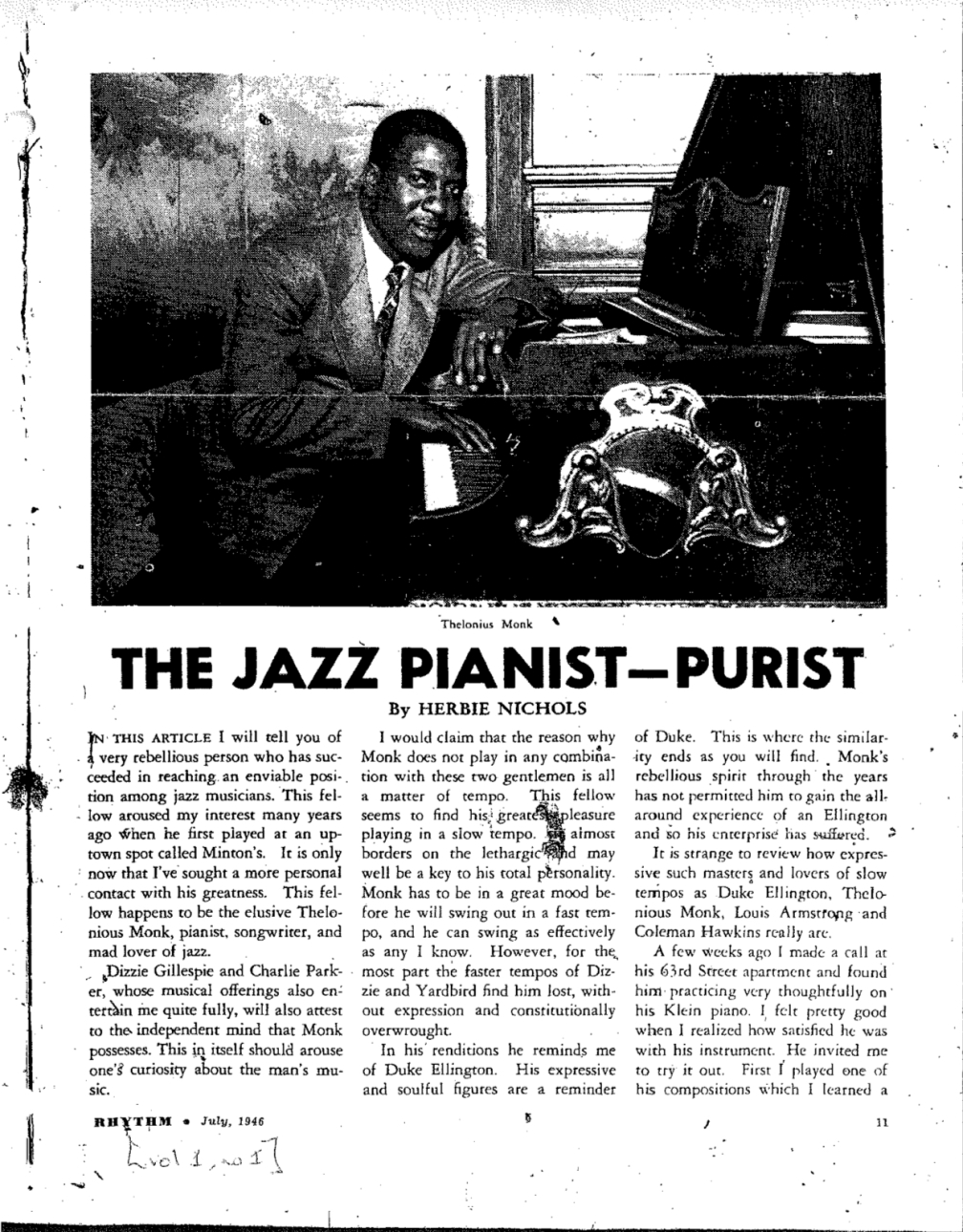

Ironically,

he wrote an article about Thelonious Monk for the African American

magazine Music Dial in 1946 that may have been instrumental in bringing

Monk to the attention of producer Alfred Lion at Blue Note. Yet Nichols

himself, despite sending frequent tapes to Lion, was not recorded by

Blue Note until eight years after the company signed Monk in 1947.

And

when he did get around to recording, his career was painfully short. In

five trio sessions for Blue Note, recorded in 1955-56, he produced

material intended for release on five 10-inch LPs. All of those

recordings, as well as extensive alternate takes, have now been released

in a three-CD collection, "Herbie Nichols: The Complete Blue Note

Recordings."

What

emerges is a too-brief portrait of a genuinely original talent.

Nichols' playing bears references to Monk and to Art Tatum, even a few

traces of Teddy Wilson and Bud Powell. And one wonders if Phineas

Newborn Jr. was familiar with Nichols, given some of the similarities in

their style. But mostly Nichols simply sounds like a unique player--so

unique that it's hard to understand why he wasn't recorded more often.

His

tunes are solid melodies, often moving in unlikely harmonic directions,

and--like Monk's music--intriguing enough and filled with sufficient

musical resources to attract the attention of other players.

Unfortunately, the music in this compilation, attractive as it is,

represents a small portion of Nichols' 170 compositions.

Still,

it's all that remains of his work as a leader (he recorded on rare

occasion as a backup player), and Blue Note should be commended for

making it available. (Mosaic issued the same material a few years ago in

a limited-edition, five-LP boxed set.)

A.B.

Spellman's book "Black Music: Four Lives" (Schocken Books) includes an

extensive interview with Nichols, speaking shortly before his death.

"I'm not making $60 a week," Nichols told Spellman. "I'm trying to sell

some copyrights, but if you don't have somebody behind you in this

country, you die."

Nichols'

talent, his creativity, and his intelligent observations about the

music business are the stuff of an important jazz voice--one that

deserves to be rescued from its current anonymity.

On

the Shelves: There is plenty of interesting reading matter available

for holiday gift giving for both the dedicated and the casual jazz fan.

For example, no less than three Thelonious Monk books arrived in the

legendary jazzman's 80th anniversary year.

"Thelonious

Monk: His Life and Music," by Thomas Fitterling (Berkeley Hills Books),

first published in Europe in 1987 and now available in a new

translation, takes a look at Monk from three perspectives: his piano and

composition techniques and his discography.

"Straight,

No Chaser, The Life and Genius of Thelonious Monk," by Leslie Gourse

(Schirmer Books), is written in the author's characteristically detailed

style, filled with anecdotal material, and based upon extensive

interviews with friends and family.

"Monk,"

by Laurent de Wilde (Marlowe & Company), is particularly intriguing

because it was written by a first-rate jazz pianist. De Wilde's

observations are all highly personal, his viewpoint that of a musician

attempting to find insights and understanding in the life of a

much-admired influence.

Miles

Davis fans will find a variety of diverse views of the Prince of

Darkness in a series of essays in "A Miles Davis Reader," edited by Bill

Kirchner (Smithsonian).

Another

book by a practicing musician, "What Jazz Is," by pianist Jonny King

(Walker), informatively addresses questions listeners always ask about

jazz--"Where's the melody?" "What does the rhythm section do?," etc.

And

budding guitarists who have worn out their blues licks will enjoy the

quick entree into jazz phrases provided by guitarist Sid Jacobs'

"Complete Book of Jazz Guitar Lines and Phrases" (Mel Bay

Publications).

Mark Miller’s Herbie Nichols: A Review

September 23rd, 2010

Jazz Journalists Association

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

by Mark Miller

Mercury Press, Toronto, 2009; 224 pp.; $19.95 paperback

The jazz world is filled with musicians who have not received the recognition they deserve. But after reading Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life by veteran journalist Mark Miller, the obscurity surrounding this pianist seems particularly tragic.

Nichols

had his heart set on being a classical pianist, but because a classical

career was impossible for a young African-American in the 1930s, he

switched to jazz. “My earliest ambitions were to become a Prokofiev,”

Miller quotes him as saying. “When I learned that I would be unable to

obtain formal conservatory training I decided to become an Ellington and

to enter the fascinating field of jazz.”

In

the author’s notes and acknowledgements, Miller quotes one of Nichols’

admirers, pianist Frank Kimbrough: “I can’t imagine anyone coming up

with enough information for a book [on Nichols].” Miller is to be

commended for completing that task. However, one wonders how many jazz

followers know enough about Nichols to be interested in learning more.

Nichols clearly had the talent to be successful, but he had a somewhat

distant personality and also seemed to be haunted by the success of his

peer, Thelonious Monk.

Nichols

often lamented his separation from the classical world and was critical

of the attitude of other jazz musicians toward it. According to Miller,

“He acknowledged the tension between classical and jazz musicians, a

tension that he clearly still felt in himself, given his early

aspirations in the classical field and his undying respect for its

ideals and innovations.” Writing in the Harlem magazine, Rhythm,

Nichols said, “The funniest thing to me is the complete realization

that our florid 1946 jazzmen are austere creatures who actually sneer at

the classicists. It is all an emotional mumble jumble wherein we fools

should be big enough to view everything objectively.”

Nichols’s

alienation from many of his contemporaries is typified in comments he

made to the poet George Moorse: “I used to sit in a lot in the late

thirties and forties with the guys who later became known as the

bopsters. I guess my playing was even too far out for them. And most of

them thought I couldn’t say anything. Of course, in those days I must

have looked like a professor, with a starched white shirt. I used to

talk about poetry almost as much as I talked about music.”

The

vocalist Sheila Jordan recalled that Nichols would “sit in a corner. It

wasn’t that he was standoffish, I think he was shy – or maybe his mind

was elsewhere…. He was very quiet, stayed to himself, went and stood

outside of the club, smoked his cigarets [sic]. I don’t ever remember

him even talking to anybody.”

Then

there were the comparisons with Monk, who did achieve the widespread

recognition that alluded Nichols. According to Miller, both were

“similarly influenced by Ellington,” but Monk by 1944 was “already a

force among his contemporaries for the formative role that he had played

at Minton’s [Playhouse] in shaping the conventions of bebop.” Critic

Lawrence Gushee, writing about Nichols’s 1957 Bethlehem album Love Gloom Cash Love in The American Record Guide,

said there were “pretty obvious” reasons for comparing Nichols and Monk

but concluded that Nichols “is far from the champion that Monk is.” On

the other hand, Alfred Lion, co-owner of Blue Note Records, told

producer Michael Cuscuna in 1985 that when he first heard Nichols, “I

hadn’t been so excited about someone since I first heard Monk.”

Miller’s

book is at its best when describing Nichols’s live performances and his

willingness, coupled with practical necessity, to play at all kinds of

gigs, giving his all even when the style wasn’t his preference. The book

only bogs down when Miller goes into unnecessary detail about each

selection of Nichols’ recordings.

Dan

Morgenstern expressed the tragedy of Herbie Nichols most succinctly in a

quote at the beginning of chapter five, which covers the period from

1958-1961. “Herb Nichols,” wrote Morgenstern in the January 1959 issue

of Jazz Journal,

“has, of course, recorded with Rex Stewart, and with his own trio on

two ten-inch Blue Note LPs and on the defunct Hi-Lo label, but all of

this is out of circulation, and so is Herb.”

About the Author:

Sanford Josephson is the author of Jazz Notes: Interviews Across the Generations (Praeger/ABC-Clio), and currently writes the “Big Band in the Sky” obituary section for Jersey Jazz, the magazine of the New Jersey Jazz Society.

The Complete Blue Note Recordings by Herbie Nichols

There

is a little dark bar I like to go to where people know things. We wile

away the nights in friendly arguments. Which phase of Bergman’s career

gave us the best movies, where in Mexico is Ambrose Bierce living and

who are the all time greatest jazz pianists? What is interesting is that

now, one of the main ingredients in determining "the best" seems to be

their level of exposure.

Perhaps

the greatest accolade and curse an artist can be given is to be termed

"an artist's artist." The label which seems to resign them to obscurity

except among the most hard core aficionados. This has largely been

Herbie Nichols’ fate.

Herbie

Nichols (1919-1963) started formally studying piano at the age of nine.

Early on he mainly played in Dixieland bands, a start akin to two other

fonts of progressive improvisation, Steve Lacy and Roswell Rudd. These

two would also later prove to be two of the most talented interpreters

of his music. For all of them, these early Dixieland years were more of a

financial necessity than an aesthetic choice.

Herbie

also played in The Savoy Sultans while mingling with the early

progenitors of Bop. Aside from a friendship with Thelonious Monk, he did

not get much joy out of the then fertile 52nd Street scene. During this

time there was still a misplaced nobility associated with jazz

musicians and addiction(s). Herbie, ever the tea-totaler was shunned.

Another off-putting aspect of this quite young man was his intellect.

Herbie played chess, wrote and appreciated poetry. He also wrote

insightful jazz articles. Well before jazz aficionados gleaned onto him,

he wrote an article on Monk for Dial Magazine.

In

1941 he was drafted into the army. It would be another two years before

he was demobilized, partially eating up the time by writing poetry and

lyrics.

Upon

his discharge, he found himself back in New York where he had to play

piano for burlesques in Greenwich Village to make rent.

Pianist Mary Lou Williams was the first to record one of Herbie’s songs (1951) "Stennell," which was re-titled "Opus Z."

Starting

in 1947 he would send his music to Blue Note’s Alfred Lion. For various

reasons it would take nine more years before Herbie would be signed.

Herbie was one of three all time great pianist-composers signed by

Alfred Lion (Thelonious Monk and Andrew Hill being the other two).

Things

seemed to be looking up for Herbie. Also around this time (1956) Billy

Holiday fell hard for his piece "Lady Sings the Blues" writing lyrics

for it and making it her own to the point of using it for the name of

her autobiography, too. The piece, originally titled "Serenade" has

become an important part of the jazz lexicon and a totem of longing and

heartache.

Herbie

wrote over 170 songs. After his death much of his writing which was

then stored at his father’s house was lost in a flood. We owe much of

our knowledge of his pieces to Herbie himself, he had always been

diligent about supplying the library of congress with his scores.

He

would record three albums for Blue Note Records and one for Bethlehem.

This would be followed by five years of studio inactivity, when jazz was

in a constant frenzied state of flux. At the end of this period Herbie

would die way too early of leukemia. A factor in Herbie’s long standing

obscurity would seem to be lack of recorded sideman appearances. He did

share the stage with some established heavy weights, but unlike another

"obscure" pianist who also recorded for Blue Note, Elmo Hope, there is

not sideman documentation on record for fans to hunt down or the casual

listener to come across. An artistic ascension established without wax

pedigree save for his own recordings.

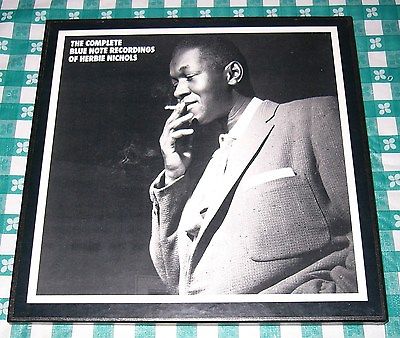

The

Blue Note boxed set collects all of his Blue Note output. It comprises

thirty songs with eighteen, previously unreleased alternate tracks.

Unlike some alternate tracks to be found on other musical omnibus, these

alternate tracks will appeal to more than just the jazz completionists.

Often it is subjective which is the "better" version of a track. The

liner notes make mention that it sometimes took lengthy discussions to

decide.

The

packaging is aesthetically pleasing and avoids some of the more

impractical concepts of other boxed sets. A cardboard slip case houses

three CDs and a booklet. The tracks and musician information are listed

on back of the slipcase and in the booklet itself. The CDs each go in a

slim case which contains a different image on each by Francis Wolf, the

man responsible for some of jazz’s most iconic images. The booklet

contains the album’s original liner notes by Herbie himself and an

informative essay by Frank Kimbrough and Ben Allison; the founders of

The Herbie Nichols Project which is a group seeking to further

appreciation of Herbie’s work through recordings and concerts.

The

sound is pristine, the entire collection having been remastered by

Michael Cuscuna, a man behind many important reissues over the years and

a man who has made the remaster an art unto itself. The Super Bit

Mapping process was used which allows the music to retain its ambient

warmth while combining it with digital clarity.

From

the start, Herbie’s intellect and formal training had given him an

appreciation for 20th century composers. It is not too much of a stretch

to see similarities between some of Herbie’s oeuvre and turn of the

century French pianist/composer Erik Satie, whose deceptively simple

melodies and their daydream inducing properties (Gymopedies,

Gnossiennes) Herbie’s own compositions sometimes mirrors.

Also

in the classical tradition, much of Herbie’s music was Programme music,

music which like some of Debussy’s and Liszt’s was inspired by and

describes a specific thing. Song titles were given much thought and an

important part of the overall creative process for Herbie.

Although

a contemporary of both Monk and Bud Powell, Herbie has often been

referred to as a "disciple of.... " His playing does have some

percussive aspects to it, the earliest most visible proponent of such

technique being Bud Powell. I have found though, that one of the marvels

of Herbie’s playing is his ability often contained within one piece to

change tempos, touch and the actual cadence of his pianos tone. While

there is definite joy to be had listening to the percussive school of

playing, after awhile a formula is detected in a song’s structure. This

never occurs with Herbie’s playing and pieces.

His

friend Monk is a noticeable influence but no more so than the jagged

lines to be found in the rhythmic works of Hungarian composer Bela

Bartok who Herbie also greatly enjoyed.

Too

often it is the easy thing to call any pianist/composer with odd time

signatures or jagged note/chord clusters "Monk-like". Cecil Taylor and

Andrew Hill also frequently get this adjective. What the three have in

common is that they represent separate artistic evolutions stemming from

the same instrument and to some extent the same inspiration of Monk. It

is a new modern classical. Jazz is sometimes referred to as American

classical, but these three provide a more literal example. To really

listen to their music is to realize they are from jazz but not of jazz.

It

is not a case of "better than" but of the three Herbie is the more

accessible style wise. While he remained his own man, he drew from

diverse sources such as the previously mentioned classical idiom. There

was of course the vernacular of jazz in many forms to be found too in

both his playing and composing, elements of bop, stride and things yet

to come, but also Caribbean rhythms which made up some of his ethnic

background and Indian music which was another key to his works rhythmic

complexity. Cecil Taylor’s music is amazing and complex as is Andrew

Hill’s, even now their music seems ahead of the curve; musical taste

makers still not having caught up to them. A modernism which in its

newness and containing cerebral aspects, manages to intimidate many.

Herbie’s manages to be cerebral but often with a playful sense of humor.

Before

these sessions, as was Blue Note’s habit, the artists were allowed

ample rehearsal time. In general, this practice led to the freedom to do

more complex pieces and not have to have non-touring/working bands rely

on jazz standards for lack of knowledge of a new piece.

There

are no weak links in what is essentially two trios. Another practice of

Blue Note’s was to put a more established musician from their stable on

a session by a new guy. While this has never been disastrous it had

made for some odd and uncomfortable pairings, such as some of the

session men of Thelonious Monk’s Blue Note Debut "The Genuis of". Al

McKibbon had been the house bassist at Birdland and often played with

Thelonious Monk. He is able throughout the recordings to provide a solid

bottom without any hint of boredom inducing repetition.

While

it is easy to lament the fact that Herbie never got to play with the

likes of Elvin Jones or Tony Williams, to name but two top notch

skin-men, here, Max Roach is a perfect fit.

Like

Herbie and many other greats of jazz’s next era, Max formally studied

at the Manhattan School of Music. At the age of eighteen Max had been

the house drummer at Monroe’s Uptown House, which along with Minton’s

Playhouse was ground zero for bop. Here he came into contact with jazz’s

vanguard.

He

and Kenny Clark were directly involved with the creation of bop. Max

was one of the first, true percussion stars who helped change the way

his instrument was played. Instead of keeping time and then impressing

during solos with pure speed, Max created the now well known technique

of creating pulse points not with the base drum as had been the standard

but utilizing the cymbals. This allowed for great freedom for the other

instruments’ solos as well as his own. It also allowed for more

dramatic and supple tempo changes.

Max

would perfect his voice initially on the early important records of

Charlie Parker’s, who he was with 1945, 1947-49 and 1951-53. He would

appear with the who’s who of jazz. It was not until 1953 however that he

finally recorded a date as a leader. Like many of his peers, he now saw

bop as becoming formulaic but still a worth while jumping off point.

With Miles Davis and a host of others there would be the "Birth of the

Cool" sessions where he would participate in the birth of third-stream

music, a sort of hybrid of symphonic big band mixed with intricate solos

which organically grew out of the main body of a piece. There was ever

an ongoing process of things being added to Max’s palate, the common

factor throughout it all was an intricate forward thinking bent.

Around

the time he was doing the sessions with Herbie he had also had his own

group, co-led with trumpeter Clifford Brown and Bud Powell’s younger

pianist brother, Ritchie. The group would last for only two years, a

fatal car crash taking both Clifford and Ritchie. Max would continue the

group with Kenny Dorham on trumpet and Sonny Rollins replacing Harold

Land on tenor sax. These two versions of his group showed him the way to

naturally meld impressive solos with more intricate arrangements,

arrangements which did more than serve to fill time between the

musicians' solos.

With

Herbie you hear a most successful partnership not born of touring but

sharing the same combination of daring and highly polished talent.

On

disc two "House Party Starting" contains subtle tempo changes and a

long snaking rhythm which is trance inducing, like watching candlelight

reflect off the polished wood of a bar. The song seems to almost stop

time without relying on mere repetition. This was actually the first

song I ever heard by Herbie and every time, still, I marvel at not just

the song structure but his ability to seamlessly change himself within

the body of one piece.

Teddy

Kotick throughout his career took great pride in sticking with the

rhythm section and avoiding solos. He had a rich tone which has been

heard on many important jazz records from the 50’s and 60’s. What is

interesting is the subtle difference in the pieces which feature him as

opposed to Al. Too often if a bassist does not specialize in solos or

does not take his obligatory turn during a piece, people seem hard

pressed to notice a difference. But notice the subtle changes in Max’s

playing on pieces which feature him with Teddy instead of Al. Both

bassists add to the pieces which already contain kinetic aspects to

them.

The

other drummer on the sessions is Art Blakey. Art had gotten his start

in the big band circuit including time in the forward thinking Flecther

Henderson group. He naturally gravitated towards the bop players brining

the steady funky groove concept to this new jazz.

Art

felt that with the possibilities of this new music being made, a band

should work as a cohesive unit, not just providing back up for whom ever

was soloing. He appeared on many seminal albums before forming a sort

of jazz collective, The Jazz Messengers.

Art

was one of the first jazz musicians to be interested in what would

later be known as world music, mixing in aspects of it in his playing.

Aside from leaving a legacy of adding to percussionists over all

palette, he left what could possibly be considered jazz’s version of an

ivy league school, The Jazz Messengers.

Many

of his band members would go on to lead groups of their own. There were

many incarnations of this band and the roster reads like jazz royalty

role call.

Even

while working with various versions of his own ensemble, Art was

frequently to be found on other artists’ dates. He played on Thelonious

Monk’s first Blue Note dates (now available as two separate remasters

Genuis of Modern Music vols 1&2.) Similar to this Herbie Nichols

collection, he and Max split drum duties on the still amazingly powerful

album "Thelonious Monk Trio (Fantasy Records 1952.)

Around

the time of the Herbie Nichols session, Art and an incarnation of the

Jazz Messengers which featured Clifford Brown, Horace Silever, Lou

Donaldson and Curly Russell were recorded live at Birdland. (A Night at

Birdland Vols 1&2 Blue Note Records). Aside from being a compelling

live document of a version of the Messengers which was as powerful as

it was short lived, it manages to capture if not the birth, then the

infancy of what would become known as hard-bop.

Both Max and Art had always been polyrhythmic, but Art ‘s was more an emphasis on setting up a funky groove.

On

the first CD "It Didn’t Happen" which Herbie wrote just four days

before going into the studio. It was inspired by an unrequited romance

and Art shows that funky can also be accomplished with great subtlety.

Like

Monk, Herbie did not often do covers and usually when done they would

be lesser known pieces that could be made their own. Here Herbie tackles

Gershwin’s "Mine" from a musical revue "Of Thee I Sing".

All

the music to be found on these three discs is thoroughly engrossing,

but not in a way that demands one listens in silence or alone.

When

it comes up again, and I am looked at with skepticism by those who have

yet to discover Herbie’s art, is he one of the greatest?

All I can do is paraphrase Joyce’s Molly Bloom:

"Yes, yes.."

Additional Info

Artist / Group Name: Herbie Nichols

CD Title: Herbie Nichols-The Complete Blue Note Recordings

Genre: BeBop / Hard Bop

Year Released: 1997

Reissue Original Release: 1955-56

Record Label: Blue Note

Musicians: Herbie Nichols (piano), Al McKibbon, Teddy Kotick (bass), Max Roach, Art Blakey (drums)

Label Website: -

Rating: Four Stars

Albums We Love: Herbie Nichols

by Jessica Rand KMHD Jazz Radio | June 4, 2013 3 p.m. | Updated: April 1, 2015 12:54 p.m.

Herbie Nichols

Love, Gloom, Cash, Love (Bethlehem, 1957)

Herbie

Nichols has been called one of jazz’s “most tragically overlooked

geniuses” and the pianist’s final 1957 masterpiece, Love, Gloom, Cash,

Love, bears witness to that description. Some think of him as a disciple

of Thelonius Monk, but that’s not giving him nearly enough credit.

Highly imaginative and unpredictable, Nichols was a contemporary of

Monk; he was also equally innovative, curious and playful.

For

those who only know his earlier Blue Note recordings, or the iconic

song he composed — Lady Sings the Blues — for Billie Holiday, the

Bethlehem date is a revelation. The soothing sophistication of his piano

work is rounded out by Charles Mingus’ drummer Dannie Richmond and

bassist George Duvivier to create the challenging, provocative and

magical wonderland that is Nichols’ vision of jazz. The melodies are

complex; the rhythms subdued.

Denzil

Best’s 45 Degree Angle is a finger-snapping, mischievous smoker while

All the Way is breathtakingly restrained and romantic. The spirited

warmth of Every Cloud is a playful exchange between Nichols’ heavy piano

chords and Richmond’s shifting rhythms. Beyond Recall is a

call-and-response jazz march, perhaps reminiscent of his days serving in

World War II. Nichols’ whimsical imagination comes to the fore in the

title track, Love, Gloom, Cash, Love, a sweet, gratifying waltz.

Sadly,

just as Nichols began to develop a following, he was stricken with

leukemia and died too young in 1963. Humble and hard-working, he wasn’t

alive long enough to reap the benefits of his genius and his works went

largely forgotten. It’s time to pull this album from the vaults and

rediscover the warmth, imagination and spirit of his long overlooked

brilliance.

– Jessica Rand, Host of Takin’ Off, Mon-Thurs, 3-6pm.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Herbie-Nichols

Herbie Nichols

American musician

- Also known as

-

- born

January 3, 1919

- died

April 12, 1963 (aged 44)

Herbie Nichols, byname of Herbert Horatio Nichols (born Jan. 3, 1919, New York, N.Y., U.S.—died April 12, 1963, New York City), African-American jazz pianist and composer whose advanced bop-era concepts of rhythm, harmony, and form predicted aspects of free jazz.

Nichols attended the City College of New York and served in the U.S. Army in 1941–43. He participated in the Harlem sessions that led to the development of bop, and Billie Holiday wrote lyrics to his song “Lady Sings the Blues.” Most of his career, however, he spent playing in Dixieland

and swing groups or accompanying singers and nightclub acts, only

occasionally working with stylistic contemporaries or performing his

original music publicly.

He

composed about 170 songs, and in 1955–57 he recorded the four albums

upon which his reputation is largely based. After his death, from leukemia, most of his unrecorded compositions were

destroyed in an apartment flood; however, unissued recordings by

Nichols, including eight “new” songs, were discovered and released in

the 1980s.

As

a pianist Nichols was at his best interpreting his own compositions; he

also was his own best interpreter. Like early jazz composers, Nichols

created portraits (“117th Street,” “Dance Line”) and dramas (“Love,

Gloom, Cash, Love,” “The Spinning Song”) in his themes. The harmonic

foundations of his songs were original and often daring; his structures

frequently extended song form far beyond the customary four strain, 32

measure limits. His solos, which were variations on his themes,

incorporated rhythmic displacements and reharmonizations and created

open spaces in his melodic lines that inspired interplay with his

drummers. The generous strain of humour in his work belied the

difficulties he experienced in his career.

Friday, March 13, 2015

The Music of Herbie Nichols featuring Jason Marsalis

I've

got a string of interesting gigs coming up these days including several

dates leading a quartet featuring Jason Marsalis on vibraphone, playing

the music of pianist Herbie Nichols.

I've

been fascinated with Nichols' music for over ten years now. I was first

introduced to his music while I was studying with Matt Wilson in New

York City in 2004 and he was playing with the Herbie Nichols Project, a

band co-led by Ben Allison and Frank Kimbrough that extensively

researched and performed his music.

I'm also looking forward to finally working with Jason Marsalis. He's a force on the drums AND now the vibraphone as well!

We are at the Yardbird Suite in Edmonton, AB on Friday, March 20th:

And River Park Church in Calgary on Saturday, March 21st, presented by JazzYYC:

Here's a link to a little interview I did with JazzYYC in advance of our Calgary concert:

Interview: Fay Victor on Herbie Nichols

(photo: Fay Victor by Eliseo Cardona)

Some of the most memorable – poetically exuberant and just plain house-rocking – concerts over the past five years of the Sound It Out series have been those by singer Fay Victor’s Herbie Nichols Sung band. This Friday, June 23, at Greenwich House Music School,

Fay will return to lead her hard-grooving quintet in a two-set event to

help celebrate the fifth anniversary of Sound It Out, as well as raise

money for Greenwich House. Fay and company – Michaël Attias (alto and baritone saxophones), Anthony Coleman (piano), Ratzo Harris (double-bass) and Devin Gray

(drums) – will be performing her vocal re-creations of music by the

great, unsung bop-era pianist-composer Herbie Nichols, who penned the

music for Billie Holiday’s “Lady Sings the Blues,” along with making

evergreen trio recordings under his own name for Blue Note and

Bethlehem. Nichols, a New York City native born in 1919 and who died at

age 44 in 1963, would no doubt love what Fay does with his music, as he

once said: “The voice is the most beautiful instrument of all.”

About

her project to convey the spirit of this music vocally, Fay told me:

“I’ve been working with Herbie Nichols’ music for over a decade and a

half – I’m madly in love with it. His is joyous, irresistible music,

even if it has been sadly underplayed. There are scholarly approaches to

his pieces, but our way is to open up the forms and get that joyousness

across. Except for Billie’s words to ‘Lady Sings the Blues,’ I wrote

the lyrics to all the tunes, with the words coming out of the music

itself and my response to it. The way the band plays is sensitive and

open but with real muscularity and intensity. I hope people aren’t

intimidated if they don’t know the music or even the name of Herbie

Nichols – I want them to come dig the music and leave having been taken

by the beauty of the melodies and their singability. I want people to

fall in love with Herbie Nichols like I have.”

Before

my interview with Fay continues below, it’s perhaps best to interpolate

a description of Nichols’ music – the best I know – that appears in the

liner notes to the indispensable boxed set The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Herbie Nichols.

Describing the art of Nichols, estimable jazzers Frank Kimbrough and

Ben Allison write: “As a pianist, [Herbie] was kaleidoscopic,

encompassing the entire history of jazz piano and much of European

classical music as well, which blended with his own innovative harmonic

and rhythmic ideas – allowing him to weave a style that is essentially a

school unto itself. Although his playing is often compared to that of

his contemporaries Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell – and one can also

detect the influence of Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum and Jelly Roll Morton,

among others – [Herbie] is like no other. He possessed a touch capable

of evoking the entire emotional spectrum, from quiet introspection to

joyous exuberance, and from delicate sensitivity to primitive brutality…

“As

a composer… [Herbie penned] tunes that are evocative, usually written

with a particular place, person, event or feeling in mind. His oblique

approach to melody and harmony creates musical ideas that sparkle the

more they are scrutinized. Herbie’s love of mixing the strange with the

familiar gives his music the feeling of simultaneously looking backward

and forward in time. Imagine a Dixieland beat, a diatonic, hummable

melody, and the harmonies of Bartók all woven together and you’ll get

the idea. Nobody’s music grooves like Herbie’s… [It] reveals a lope and

sense of humor that could only come from playing the Harlem and

Greenwich Village dives where he so often worked. You can feel the sweat

of the crowd, see the dancers, taste the 15-cent beers, smell the

cigarette smoke swirling around the music.”

How could you not dig that? Now onto more of my conversation with Fay…

Bradley Bambarger: Was the late-’80s LP Carmen Sings Monk, by Carmen McRae, a key inspiration for you? Did it plant a seed for your Herbie Nichols Sung project?

Fay Victor:

Oh, yes, that was a big inspiration, as I first heard it around the

time I got started singing. I know and love that album deeply – it’s

amazing, so adventurous. It was the first record I knew where a singer

devoted an entire album to exploring a composer of primarily

instrumental music. As much as I had loved Monk before that – and knew

the famous vocal versions of “Round Midnight” that had already been done

– the Carmen McRae album made Monk’s music more accessible to me as a

singer. It opened up possibilities in my thinking. But a figure who

inspired me directly when it came to the music of Herbie Nichols was the

late Mischa Mengelberg [the Dutch pianist, composer and arranger, who

recorded exciting, individualist interpretations of Nichols’ music with

his ICP Orchestra]. I’m dedicating this concert to Mischa’s memory, his

example. He had this deep knowledge of the jazz tradition, as well as a

real love of improvisation – and a playful sense of humor.

My

first work with Herbie’s music was when I wrote lyrics for his tune

“House Party Starting,” calling it “Tonight.” I recorded that song for

my second album, Darker Than Blue,

which came out in 2001. Pianist Vijay Iyer and bassist John Hébert, who

many jazz fans know well, were on that record. All these years later,

and I’ve recently recorded a live trio album of Herbie Nichols music in

Europe, with pianist Achim Kaufmann and reed player Tobias Delius at the

Bimhuis in Amsterdam and the Loft in Cologne.

BB: What does the music of Herbie Nichols say to you?

FV:

More than anything, there’s that joy in Herbie’s compositions. The

sheer exuberance in his music is one element that makes it ideal for

singing. You know, Herbie’s mother was from Trinidad and so was my

mother. I’ve spent a lot of time down there, and I can discern a

characteristic Trinidadian trait in his music, a mix of intellectual

confidence on one hand and not taking yourself too seriously on the

other. There’s a good-time element to Herbie’s songs coupled with a

sense of cultural and creative achievement. We want to bring something

of that alive in the way we use the tunes as vehicles for improvisation,

taking advantage of the elasticity of the music. One thing I learned

from working with Mischa and the ICP is that it’s not just the notes and

the harmonic contours of a song that matter – it’s also the spirit of

what it means to us. So, we open the songs up: The composition as a

composition is stated, but where in the process it’s stated is open to

the moment.

BB: Describe the particular sonic character of your Herbie Nichols Sung band.

FV:

First of all, these guys bring a real intensity to this music, whether

it’s the sort of smoldering intensity that Michaël Attias has or the

burning intensity of Anthony Coleman. Ratzo Harris, too – the whole band

has a strong sense of ‘inside-outside’ playing, as we’re going in and

out of the structure of the material. These guys are so good at jumping

between the two worlds seamlessly. For jazz repertory bands, it’s hard

to find players who both know the tradition and can take it further, but

these are the right musicians for it. They can take the music to a free

space and then jump back to form and time effortlessly. All of these

guys love Herbie’s music, and you can hear that. Michaël was into Herbie

way before this band. Anthony, of course, is someone who knows jazz

from its very beginnings all the way forward. He had previously delved

more deeply into Monk and Jelly Roll Morton, but that experience makes

him an ideal player for Herbie’s music. The usual drummer for this

project, Rudy Royston, couldn’t make the gig, so we have Devin Gray –

this will be his first show with the band. We rehearsed the other day,

and Devin got it right off – while bringing his own energy to the music.

BB: Which tunes will be on the set list?

FV:

We’ll be doing “House Party Starting,” “The Gig,” “2300 Skidoo,” “Step

Tempest” and “Lady Sings the Blues,” among others. And we’ll be

presenting three tunes with my lyrics for the first time live: “Double

Exposure,” “Another Friend” and “Twelve Bars.” We’re really looking

forward to sharing this music with the Sound It Out audience at

Greenwich House. As I said before, we want people to fall in love with

the music of Herbie Nichols like we have.

(photo: Fay Victor’s Herbie Nichols Sung, by Bradley Bambarger)

Posted in

Apple Music Preview

Herbie Nichols

One

of jazz's most tragically overlooked geniuses, Herbie Nichols was a

highly original piano stylist and a composer of tremendous imagination

and eclecticism. He wasn't known widely enough to exert much influence

in either department, but his music eventually attracted a rabid cult

following, though not quite the wide exposure it deserved.

Nichols

was born January 3, 1919, in New York and began playing piano at age

nine, later studying at C.C.N.Y. After serving in World War II, Nichols

played with a number of different groups and was in on the ground floor

of the bebop scene. However, to pay the bills he later focused on

Dixieland ensembles; his own music -- a blend of Dixieland, swing, West

Indian folk, Monk-like angularity, European classical harmonies via

Satie and Bartók, and unorthodox structures -- was simply too

unclassifiable and complex to make much sense to jazz audiences of the

time. Mary Lou Williams was the first to record a Nichols composition --

"Stennell," retitled "Opus Z," in 1951; yet aside from the song he

wrote for Billie Holiday, "Lady Sings the Blues," none of Nichols' work

got enough attention to really catch on.

He

signed with Blue Note and recorded three brilliant piano trio albums

from 1955-1956, adding another one for Bethlehem in late 1957. Nichols

languished in obscurity after those sessions, though; sadly, just when

he was beginning to find a following among several of the new thing's

adventurous, up-and-coming stars, he was stricken with leukemia and died

on April 12, 1963. In the years that followed, Nichols became a

favorite composer in avant-garde circles, with tributes to his sorely

neglected legacy coming from artists like Misha Mengelberg and Roswell

Rudd. He also inspired a repertory group, called the Herbie Nichols

Project, and most of his recordings were reissued on CD. ~ Steve Huey

ORIGIN

New York, NY

GENRE

-

BORN: 3 Jan 1919

Top Songs

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life