SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER THREE

MARC CARY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

REVOLUTIONARY ENSEMBLE

(June 11-17)

OLU DARA

(June 18-24)

WALTER SMITH III

(June 25-July 1)

BOBBY WATSON

(July 2-8)

JAMES MOODY

(July 9-15)

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

(July 16-22)

LEYLA McCALLA

(July 23-29)

RUSSELL MALONE

(July 30-August 5)

JOHN HANDY

(August 6-12)

STANLEY CLARKE

(August 13-19)

GREG LEWIS

(August 20-26)

JASON HAINSWORTH

(August 27-September 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/stanley-clarke-mn0000745316/biography

Stanley Clarke

(b. June 30, 1951)

Biography by Matt Collar

An innovative jazz bass superstar, Stanley Clarke is an immensely adept and highly acclaimed performer, whose melodic and harmonically rich approach to playing the bass revolutionized its role from being simply a part of the rhythm section to becoming a front-stage lead instrument. Emerging in the 1970s as a founding member of Chick Corea's groundbreaking fusion band Return to Forever, Clarke helped redefine the sound of jazz, appearing on such landmark albums as 1971's Light as a Feather and 1975's Grammy-winning No Mystery. He also embarked on his own influential and commercially successful solo career, issuing albums like 1976's School Days and 1988's If This Bass Could Only Talk, many of which found him exploring a broad array of sounds, from funk and R&B to post-bop and modal jazz. In addition to his work with Corea, Clarke has often paired with his similarly inclined contemporaries. He scored a hit with "Sweet Baby" from 1981's The Clarke/Duke Project, his first of three albums with keyboardist George Duke. Other collaborations followed, including Animal Logic with the Police's Stewart Copeland, Rite of Strings with fellow RTF bandmate Al Di Meola and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, and Thunder, the debut from his bassist supergroup S.M.V. with Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten. A marquee draw on his own, Clarke continues to collaborate often, picking up a Grammy with Corea and RTF drummer Lenny White for 2011's Forever, and regularly leading the Stanley Clarke Band with an ever-evolving lineup of artists.

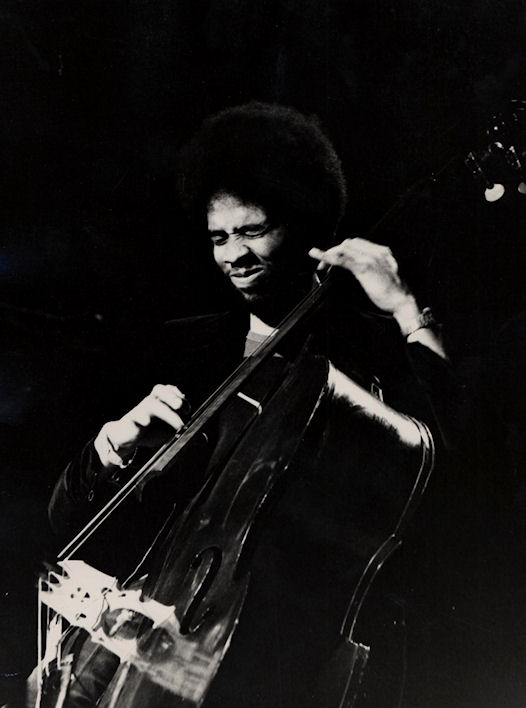

Born in Philadelphia in 1951, Clarke developed an interest in music at a young age, and was encouraged by his mother, a church choir member who often sang opera at home. Starting out first on accordion, then violin and cello, he eventually settled on the bass while attending Philadelphia's Settlement Music School. For five years, he took classical bass lessons, and originally set his sights on playing in a symphony orchestra. However, a gig at age 15 playing with saxophonist Byard Lancaster during a week of shows at the landmark Showboat Lounge solidified his passion for jazz. By high school, he was working regularly, splitting his time between jazz gigs and shows playing in pop and rock bands. He then honed his skills studying at the prestigious Philadelphia Music Academy, all the while continuing to gig around town. It was during this period that he first met future bandmate and collaborator keyboardist Chick Corea while playing a show.

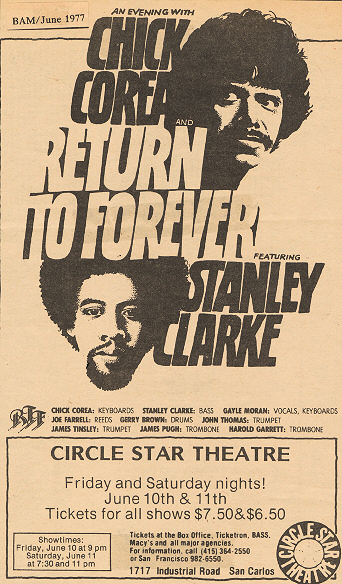

Upon graduating, he moved to New York City and quickly found work with a bevy of luminaries, including Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Dexter Gordon, Joe Henderson, Pharoah Sanders, Stan Getz, and others. It was while playing with Getz that he reconnected with Corea and co-founded the landmark jazz fusion outfit Return to Forever. For most of the 1970s Clarke toured and recorded with RTF, joined at various times by bandmates saxophonist Joe Farrell, percussionist Airto Moreira, singer Flora Purim, drummers Steve Gadd and Lenny White, guitarist Al Di Meola, and others. Along with having a strong creative influence, the band enjoyed enormous popularity, and toured the world often. In 1975, Clarke picked up his first Grammy for RTF's No Mystery, which took home the award for Best Jazz Performance by a Group.

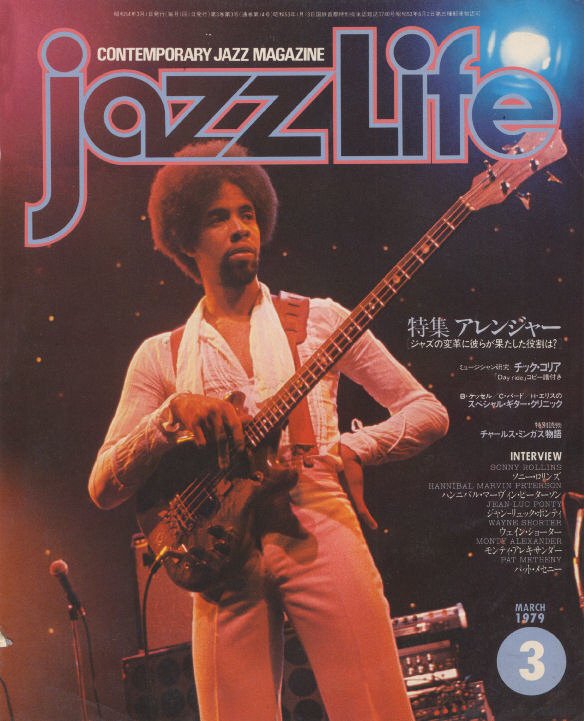

Away from Return to Forever, Clarke continued to pursue his solo career and gained increasing acclaim for his fluid bass style, which found him moving away from the instrument's traditional rhythm section role and playing lead lines and improvising. In 1973, Clarke made his debut as leader with the expansive, funk-infused Children of Forever. He then signed with Nemperor Records and issued a handful of highly acclaimed albums, including the breakthrough School Days. Featuring contributions by keyboardist George Duke, drummer Billy Cobham, guitarist John McLaughlin, and others, the album was a major success for Clarke, hitting number 34 on the Billboard 200 and number two on the Jazz Albums chart. More albums followed, like 1978's Modern Man and 1979's I Wanna Play for You. There were also sessions with Gato Barbieri, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Freddie Hubbard, Stan Getz, and others. As evidence of his growing profile outside of the jazz world, he also joined Rolling Stones bassist Ron Wood's all-star band, the New Barbarians, and toured with guitarist Jeff Beck in 1979.

In the early '80s, Clarke teamed with longtime friend and colleague keyboardist George Duke for The Clarke/Duke Project. They scored a Top 20 pop hit with "Sweet Baby," and paired again in 1983 for a follow-up and tour. He issued several more of his own jazz, funk, and R&B-infused efforts, including 1985's Find Out! (his first under the Stanley Clarke Band moniker) and 1986's Hideaway, which featured George Howard, Angela Bofill, Herbie Hancock, and Stewart Copeland. The bassist then paired again with Copeland for two albums in the fusion project Animal Logic. He closed out the decade with 1988's more post-bop and modal jazz-leaning If This Bass Could Only Talk, which also featured Copeland as well as Wayne Shorter, Allan Holdsworth, and tap dancer Gregory Hines.

Clarke stayed active throughout the '90s, reuniting with Duke for 3 and issuing his own 1993 album, East River Drive. He expanded into film music, supplying the soundtrack to the 1992 Wesley Snipes' Passenger 57. He also paired with longtime associates Al Di Meola and Jean-Luc Ponty for 1995's The Rite of Strings. In 1998, he founded the Superband, touring alongside Lenny White, Larry Carlton, Billy Cobham, Najee, and Deron Johnson. He also formed the similar all-star outfit Vertú in 1999, touring and recording with drummer White, Rachel Z, Karen Briggs, and Richie Kotzen. In 2003, he released 1, 2, to the Bass, and then paired with pianist Patrice Rushen for 2006's Standards.

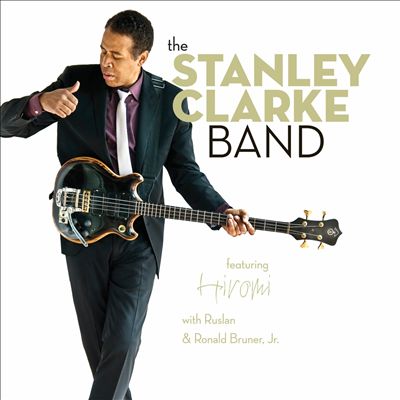

More all-star groups followed, including S.M.V., a jazz bassist supergroup featuring the talents of Clarke alongside Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten. The trio released its debut self-titled album on Heads Up in 2008. Two years later, he picked up his second Grammy, this time for Jazz Instrumental Album, for The Stanley Clarke Band, which included Japanese pianist Hiromi, keyboardist Ruslan Sirota, drummer Ronald Bruner, Jr., and a slew of guest performers.

In 2012, Clarke traveled to France to participate in a concert celebration of violinist Ponty's 50th anniversary as a recording artist. There, he joined Ponty and guitarist Biréli Lagrène in a performance that later led to the trio recording 2015's D-Stringz for Impulse! In 2018, Clarke returned to his band format with The Message, featuring pianist Beka Gochiashvili, keyboardist Cameron Graves, and drummer Mike Mitchell. The following year, the bassist supplied the score to the fashion documentary Halston, mixing jazz combo, orchestration, and synthesizer-based sounds.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/stanley-clarke

STANLEY CLARKE

Four-time Grammy™ winner Stanley Clarke is quite possibly the most celebrated acoustic and electric bassist in the world. As a performer, composer, conductor, arranger, recording artist, producer, and film scorer known for his ferocious dexterity and consummate musicality, Clarke is a true pioneer in jazz and of the bass itself. Unquestionably he is a “living legend,” lauded with every conceivable award available to a musician in his over 40- year career as a bass virtuoso.

Clarke’s incredible proficiency has been rewarded with: four Grammys, gold and platinum records, Emmy nominations, an honorary Doctorate from Philadelphia’s University of the Arts, and much more. He was Rolling Stone’s very first Jazzman of the Year and bassist winner of Playboy’s Music Award for ten straight years. Clarke was honored with Bass Player Magazine’s Lifetime Achievement Award and is a member of Guitar Player Magazine’s “Gallery of Greats.” He was even given the key to the city of Philadelphia.

Digging through the great multitude of accolades bestowed upon Stanley reveals an interesting phenomenon. It is difficult to remember how limited the potential career path of a bass player was before he came on the scene. Stanley almost single-handedly took the bass out of the shadows and brought it to the very front of the stage, literally and figuratively.

The traditional role of the bass was largely one of time-keeping that sonically filled out the spectrum. Clarke says: “Before I came along a lot of bass players stood in the back. They were very quiet kind of guys who didn’t appear to write music. But many of those bass players were serious musicians. All that I did was just take the step and create my own band.”

Certainly there were great and celebrated bass players before Stanley like Ron Carter, Scott LaFaro, and the pioneering composer Charles Mingus. But Clarke became the first bassist in history to headline sold-out world tours and have gold albums. He was also the first to double on acoustic and electric bass with equal virtuosity, power, and fire. By the time he was 25 years old, he was already regarded as a pioneer in the jazz fusion movement.

Clarke cites Mingus as a great influence personally and professionally. “The greatest moment in my life that changed me was having dinner with the great Charlie Mingus. He had the personality of a revolutionary that could have run a paramilitary group. He was very intense, heavy! That’s when I realized exactly what I wanted to do with the bass. I was going to approach my career completely like a revolutionary. Whatever was there, I was going to do the opposite.” The rest, as they say, literally is history.

Interestingly electric bass, for which Stanley is most renowned, is not his principal instrumental. His first passion, which carries to this day, is for the acoustic bass. “Electric bass is my secondary instrument. When I first started playing electric it was at parties and just for having fun. But I made records and got famous more as an electric bass player than as an acoustic bass player.”

In 1971, 20-year-old Stanley Clarke exploded into the jazz world, fresh out of the Philadelphia Academy of Music. Arriving in New York City, he immediately landed jobs with bandleaders such as Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Dexter Gordon, Joe Henderson, Pharaoh Saunders, Gil Evans, Stan Getz, and a budding young pianist-composer named Chick Corea. Stanley says: “my original goal was to be a classical bassist. I wanted to be one of the first black musicians in the Philadelphia orchestra. Chick Corea changed my mind about that.”

Clarke and Corea formed the wildly influential jazz fusion band Return to Forever, a showcase for each of the quartet’s strong musical personalities, composing prowess, and instrumental voices. They recorded eight albums, two of which are certified gold (Return to Forever and Romantic Warrior). They also won a Grammy (No Mystery) and received numerous nominations while touring incessantly.

Clarke then fired the “shot heard ‘round the world” that started the 1970s bass revolution and paved the way for all bassist/soloist/bandleaders to follow. In 1974, he released the eponymous Stanley Clarke album which featured the hit single, “Lopsy Lu.” Two years later, he released School Days, an album whose title track is now a bona fide bass anthem, a must-learn for nearly every up-and-coming bassist, regardless of genre.

Aspiring bassists must also master the percussive slap funk technique that Clarke pioneered as well. Sly and the Family Stone’s Larry Graham first developed the rudimentary slap technique. Stanley took the idea and ran with it, adapting it to complex jazz harmonies.

Always in search of new challenges, Clarke turned his boundless creative energy to film and television scoring in the mid-1980s. He is now an elite in- demand composer in Hollywood. Starting in television with an Emmy- nominated score for Pee Wee’s Playhouse, he transitioned to the silver screen and now has over 65 credits to his name.

As composer, orchestrator, conductor, and performer he has scored blockbuster films: Boyz ‘N the Hood, What’s Love Got To Do With It?, The Transporter, Romeo Must Die, Passenger 57, Poetic Justice, and The Five Heartbeats. He also scored the Michael Jackson video Remember the Time, directed by Jon Singleton. More recently he scored the 2013 box-office hit, Best Man Holliday. He has been nominated for three Emmys and won a BMI Award for Boyz ‘N the Hood.

“Film has given me the opportunity to write large orchestral scores and compose music I’m not normally associated with,” says Clarke. “It has given me the chance to conduct orchestras and arrange music for various types of ensembles. It has focused my skills and made me a more complete musician.” His 1995 CD release, Stanley Clarke at the Movies, is a testament to this. Stanley promises that he will find time to release At the Movies Two compiled from the 20 additional years of film scores since then.

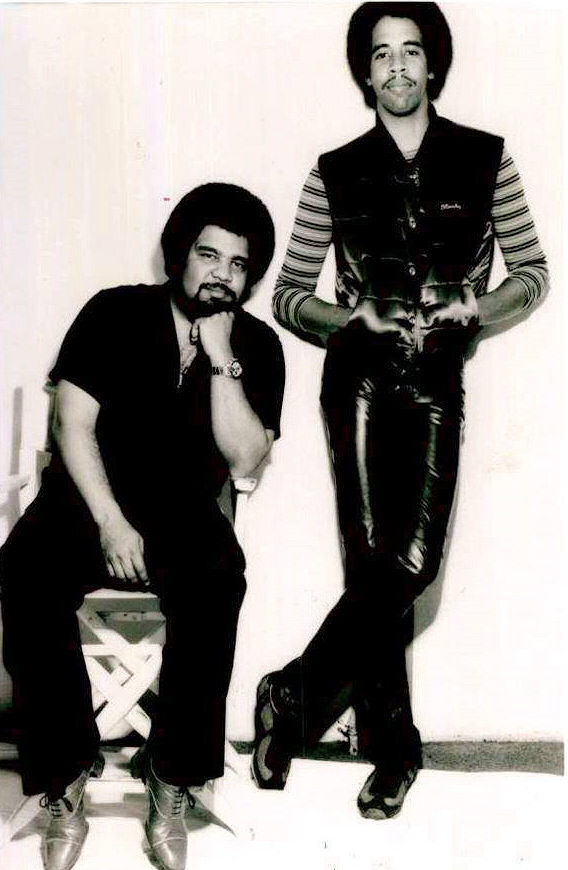

In addition to his own band, Clarke has always enjoyed collaborating with other artists. Stanley teamed up with keyboardist George Duke in 1981 to form the Clarke/Duke Project. Together they scored a top 20 pop hit, “Sweet Baby,” and recorded three albums. Stanley worked with George in various situations for over 40 years until George’s untimely passing in 2013.

Some of Stanley’s other notable projects as band member or co-leader include: Jeff Beck, Keith Richards’ New Barbarians, Animal Logic (with Stewart Copeland), Superband (with Larry Carlton, Billy Cobham, Najee, and Deron Johnson), Rite of Strings (with Jean-Luc Ponty and Al Di Meola), Vertu’ (with Lenny White), Trio! (with Bela Fleck and Jean Luc Ponty), and SMV (with Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten).

Clarke passionately believes in helping young worthy musicians. He and his wife Sofia established The Stanley Clarke Foundation in 2000, a charitable organization which offers music scholarships. In 2007 Clarke released a critically-lauded DVD entitled Night School: An Evening with Stanley Clarke and Friends chronicling the third annual Stanley Clarke Scholarship Concert with proceeds going to the fund. The concert features Stevie Wonder, Wallace Roney, Bela Fleck, Sheila E., Stewart Copeland, Flea from The Red Hot Chili Peppers, Wayman Tisdale, and Marcus Miller.

To this day Stanley Clarke remains as passionate about music as that young prodigy from Philadelphia with big dreams. His journey has already been epic and storied. Yet it is far from over.

Source: Ivan Bodley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Clarke

Stanley Clarke

Stanley Clarke at Leverkusener Jazztage (Germany), November 7, 2016

Stanley Clarke (born June 30, 1951) is an American bassist, film composer and founding member of Return to Forever, one of the first jazz fusion bands. Clarke gave the bass guitar a prominence it lacked in jazz-related music. He is the first jazz-fusion bassist to headline tours, sell out shows worldwide and have recordings reach gold status.[1][2][3]

Clarke is a 5-time Grammy winner, with 15 nominations, 3 as a solo artist, 1 with the Stanley Clarke Band, and 1 with Return to Forever.[4][5] Clarke was selected to become a 2022 recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Fellowship.[6]

A Stanley Clarke electric bass is permanently on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.[7][8][1]

Music career

Early years

Clarke was born on June 30, 1951 in Philadelphia.[9] His mother sang opera around the house, belonged to a church choir, and encouraged him to study music.[10] He started on accordion, then tried violin.[11] But he felt awkward holding such a small instrument in his big hands when he was twelve years old and over six feet tall. No one wanted the acoustic bass in the corner, so he picked it up.[12] He took lessons on double bass at the Settlement Music School in Philadelphia, beginning with five years of classical music. He picked up bass guitar in his teens so that he could perform at parties and imitate the rock and pop bands that girls liked.[10]

Clarke attended the Philadelphia Musical Academy (later known as the Philadelphia College of the Performing Arts, and ultimately as the University of the Arts, after having merged with the Philadelphia College of Art) and after graduating moved to New York City in 1971.[13] His recording debut was with Curtis Fuller. He worked with Joe Henderson and Pharoah Sanders, then in 1972 with Stan Getz, Dexter Gordon, and Art Blakey, followed by Gil Evans, Mel Lewis, and Horace Silver.[11]

Return to Forever (band)

Clarke intended to become the first black musician in the Philadelphia Orchestra until he met jazz pianist Chick Corea.[14] At the time, Corea was working with Stan Getz putting together a new backing band for him and writing music for the group; these pieces first surfaced on two albums recorded in February/March 1972 in New York, Captain Marvel (credited to Getz, released in 1974) and Return to Forever (credited to Corea, issued in Europe in 1972). Clarke's playing and improvising was prominent on both albums; the band also played a couple of gigs with Getz in Europe. At this early stage, the band as separate from Getz was mostly a studio side project, but the members soon realized that it had potential as a regular live band, and so the band Return to Forever had been born.

The first edition of Return to Forever performed primarily Latin-oriented music and used only acoustic instruments (except for Corea's Fender Rhodes piano). This band consisted of singer Flora Purim, her husband Airto Moreira (both Brazilians) on drums and percussion, Corea's longtime musical co-worker Joe Farrell on saxophone and flute, and Clarke on bass. Their first album, titled Return to Forever, was recorded for ECM Records in 1972. The second album, Light as a Feather (1973), was released by Polydor and included the song "Spain".[15][16]

After the second album, Farrell, Purim and Moreira left the group to form their own band, and guitarist Bill Connors, drummer Steve Gadd and percussionist Mingo Lewis were added. Lenny White (who had played with Corea in Miles Davis's band) replaced Gadd and Lewis on drums and percussion, and the group's third album, Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy (1973), was released.

Fusion was a combination of rock and jazz which they helped develop in the early 1970s. Clarke was playing a new kind of music, using new techniques, and giving the bass guitar a prominence it lacked. He drew attention to the bass guitar as a solo instrument that could be melodic and dominant in addition to being part of the rhythm section.[17] For helping to bring the bass guitar to the front of the band, Clarke cites Jaco Pastorius, Paul McCartney, Jack Bruce, and Larry Graham.[18]

After Return to Forever's second album, Light as a Feather, Clarke received job offers from Bill Evans, Miles Davis, and Ray Manzarek of the Doors, but he remained with Return to Forever until 1977.[18] During the early 1980s, he toured with Corea and Return to Forever, then worked with Bobby Lyle, Eliane Elias, David Benoit and Michel Petrucciani. He toured in a band with Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter in 1991. In 1998 he founded Superband with Lenny White, Larry Carlton, and Jeff Lorber.

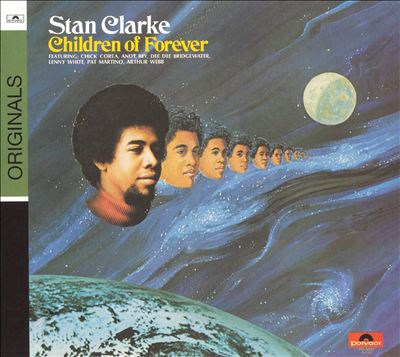

Solo

Corea produced Clarke's first solo album, Children of Forever (1973), and played keyboards on it with guitarist Pat Martino, drummer Lenny White, flautist Art Webb, and vocalists Andy Bey and Dee Dee Bridgewater. Clarke played double bass and bass guitar.[19]

Clarke's second self-titled album Stanley Clarke (1974) featured Tony Williams on Drums, Bill Connors - Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, and Jan Hammer - Synthesizer [Moog], Electric Piano, Organ, Piano [Acoustic].

While on tour, British guitarist Jeff Beck was performing the song "Power" from that album, and this was the impetus for their meeting and Beck's introduction to Hammer. They toured together, and Beck appeared on some of Clarke's albums, including Journey to Love (1975)[20] and Modern Man (1978).[21]

The album School Days (Epic, 1976) brought Clarke the most attention and praise he had received so far. With its memorable riff, the title song became so revered that fans called out for it during concerts.[18][22]

Rock and funk

Clarke has spent much of his career outside jazz. In 1979, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones formed the New Barbarians with Clarke and Keith Richards.[23] Two years later, Clarke and keyboardist George Duke formed the Clarke/Duke Project, which combined pop, jazz, funk, and R&B. They met in 1971 in Finland when Duke was with Cannonball Adderley. They recorded together for the first time on Clarke's album Journey to Love. Their first album contained the single "Sweet Baby",[24][25] which became a Top 20 pop hit. They reunited for tours during the 1990s[11] and the 2000s.[24]

Clarke joined fellow bassist Paul McCartney in 1981 to play bass on McCartney's 1982 & 1983 releases Tug of War[26] & Pipes of Peace.[27][28][29]

The Stanley Clarke Band

The Stanley Clarke Band is an American jazz band led by Clarke. He founded the band in 1985, with Ruslan Sirota, Shariq Tucker, Cameron Graves, Beka Gochiashvili, Salar Nader,and Evan Garr. They released the album Find Out!. With a new group, The Stanley Clarke Band released the album The Stanley Clarke Band which won the 2011 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Album.[30] Their album The Message was released in 2018.[31]

Career

The band's first album Find Out! was recorded at Sunset Sound Studios and was released in 1985 by Sony. With a band composed of Stanley Clarke on bass, Ronald Bruner Jr. on drums, and Ruslan Sirota on keyboards, the Stanley Clarke Band released The Stanley Clarke Band album. It was produced by Lenny White and Stanley Clarke."[32]

The album The Stanley Clarke Band won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Album at the 53rd Annual Grammy Awards.[33] Additionally, the track "No Mystery" was nominated for Best Pop Instrumental Performance.

The Stanley Clarke Band with Clarke, Bruner Jr., and Sirota released The Message[34]

Discography

- Find Out! (Sony BMG, 1985)

- The Stanley Clarke Band (Heads Up, 2010)

- Up (Mack Avenue, 2014)

- The Message (Mack Avenue, 2018)

Other groups

In 1988, Clarke and drummer Stewart Copeland of the rock band the Police formed Animal Logic with singer-songwriter Deborah Holland. He and Copeland were friends before the Police formed.[10] Copeland appeared on Clarke's album Up (Mack Avenue, 2014).[35]

In 2014 Clarke was invited on stage with Primus during their "Primus And The Chocolate Factory" tour featuring other guest appearances from Stewart Copeland and Danny Carey of Tool to perform the Primus classic "Here Come The Bastards" with Clarke and Les Claypool having a shred bass duel midway.

In 2020 Clarke was invited as a teacher at a Bass Bootcamp hosted by bassist Gerald Veasley. The camp was hosted in Philadelphia where bassists of all ages were taught and featured many educators and professionals such as Richard Waller, Rob Smith, Freekbass, Michael Manring, and more. Unfortunately the camp was delayed and moved to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other jazz groups

In 2005, Clarke toured as Trio! with Béla Fleck and Jean-Luc Ponty.[36][37] Clarke and Ponty had worked in a trio with guitarist Al Di Meola in 1995 and recorded the album The Rite of Strings.[38] They worked in a trio again in 2012 with guitarist Biréli Lagrène and two years later recorded D-Stringz (Impulse!, 2015).[9]

In 2008, Clarke formed SMV with bassists Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten and recorded the album Thunder.[39][40][41]

In 2009 he released Jazz in the Garden, featuring the Stanley Clarke Trio with pianist Hiromi Uehara and drummer Lenny White. The following year he released the Stanley Clarke Band, with Ruslan Sirota on keyboards and Ronald Bruner, Jr. on drums; the album also features Hiromi on piano.[42]

His album Up, released in 2014, has enlisted an all-star cast in his musical ensemble, including former Return to Forever bandmate Chick Corea on piano, with drummer Stewart Copeland (The Police) and guitarist Jimmy Herring (Widespread Panic), among others.[43]

In 2018, Clarke released The Message, featuring the new Stanley Clarke Band with Cameron Graves on synthesizers, pianist Beka Gochiashvili, and drummer Mike Mitchell. The album also features rapper/beatboxer Doug E. Fresh and trumpeter Mark Isham.[44][45]

In 2019, The Stanley Clarke Band has transformed again as Clarke, Cameron Graves, and Beka Gochiashvili were joined by Shariq Tucker on Drums, Salar Nader on Tabla, and Evan Garr on Violin.[46]

Television and movies

Clarke has written scores for television and movies. His first score, for Pee-wee's Playhouse, was nominated for an Emmy Award. He also composed music for the movies Boyz n the Hood, Passenger 57, and What's Love Got to Do with It,[13] the television programs Lincoln Heights and Soul Food, and the video for "Remember the Time" by Michael Jackson.[40]

In 2007, Clarke released the DVD Night School: An Evening of Stanley Clarke and Friends, a concert that was recorded in 2002 at the Musicians' Institute in Hollywood. Clarke plays both acoustic and electric bass and is joined by guests Stewart Copeland, Lenny White, Béla Fleck, Shelia E., and Patrice Rushen.[47]

Clarke's TV and movie music contribution can be found in Soul Food (2000-2004), Static Shock (2000-2004), First Sunday (2008), Soul Men (2008), The Best Man Holiday (2013), and Barbershop: The Next Cut (2016).[48][49][50][51]

His latest score composition work was for the documentary film Halston (2019), directed by Frédéric Tcheng.[52][53] The film tells the extraordinary story of the life and death of the American fashion designer, Roy Halston Frowick.

Record label

In 2010, Clarke founded Roxboro Entertainment Group in Topanga, California. He named it after the high school that he attended in the 1960s. The label's first releases were by guitarist Lloyd Gregory and composer Kennard Ramsey. Roxboro's roster also includes keyboardist Sunnie Paxson, pianist Ruslan Sirota, and pianist Beka Gochiashvili.[54]

Electric bass technique

When playing electric bass, Clarke places his right hand so that his fingers approach the strings much as they would on an upright bass, but rotated through 90 degrees. To achieve this, his forearm lies above and nearly parallel to the strings, while his wrist is hooked downward at nearly a right angle. For lead and solo playing, his fingers partially hook underneath the strings so that when released, the strings snap against the frets, producing a biting percussive attack. In addition to an economical variation on the funky Larry Graham-style slap-n'-pop technique, Clarke also uses downward thrusts of the entire right hand, striking two or more strings from above with his fingernails (examples of this technique include "School Days", "Rock and Roll Jelly", "Wild Dog", and "Danger Street").[55][56][57][58] Clarke has been playing Alembic short scale basses since 1973. Alembic also manufactures a series Stanley Clarke Signature Bass models.

Awards and honors

Grammy Awards

| Year | Nominee/work | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | No Mystery (Track) | Best Jazz Performance by a Group | Won |

| 1977 | Life is Just A Game (Track) | Best Instrumental Arrangement | Nominated |

| 1979 | Modern Man (Album) | Best R&B Instrumental Performance | Nominated |

| 1982 | The Clarke/Duke Project (Album) | Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals | Nominated |

| 1985 | Time Exposure (Track) | Best R&B Instrumental Performance | Nominated |

| 1987 | Overjoyed (Track) | Best Pop Instrumental Performance | Nominated |

| The Boys Of Johnson Street (Track) | Best R&B Instrumental Performance | Nominated | |

| 2004 | Where Is The Love (Track) | Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals | Nominated |

| 2011 | The Stanley Clarke Band (Album) | Best Contemporary Jazz Album | Won |

| No Mystery (Track) | Best Pop Instrumental Performance | Nominated | |

| 2012 | Forever (Album) | Best Jazz Instrumental Album | Won |

| 2015 | Last Train To Sanity (Track) | Best Instrumental Composition | Nominated |

Latin Grammy Awards

Clarke received the Latin Grammy for Best Instrumental Album in 2011 at the 12th Annual Latin Grammy Awards for the album "Forever", along with Chick Corea and Lenny White.[60]

Other honors

- Lifetime Achievement Award, Bass Player, 2006[61]

- Honorary doctorate in fine arts, The University of the Arts, 2008[62]

- Honorary Doctorate in Music, Musicians Institute, 2009[63]

- Miles Davis Award, 2011[64]

- NEA Jazz Master Fellowship, 2021[6]

Discography and filmography

Music Credits:

“1504 Suite” music and performance by Stanley Clarke and Ruslan Sirota.

“Hello Again” composed by Stanley Clarke, performed by Return to Forever, from the album, The Best of Return to Forever.

“School Days,” composed and performed by Stanley Clarke from the album, School Days.

“La Canción de Sofia” composed by Stanley Clarke, performed by The Stanley Clarke Band, from the album, Up

Excerpt from Boyz ‘n the Hood, composed by Stanley Clarke

“NY” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the album Soul Sand. Used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Jo Reed: You’re listening to 2022 NEA Jazz Master bassist and composer Stanley Clarke accompanied by pianist Ruslan Sirota. From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed

There’s so much to say about Stanley Clarke, it’s hard to know where to begin…..he’s played with jazz legends like Art Blakey, Horace Silver, and Stan Getz—among others. Clarke is one of the original members of Return to Forever, a jazz fusion group founded by Chick Corea that has been expanding the sounds of jazz for the past half century. Clarke has worked as a solo artist—placing the bass front and center as the lead instrument, t and releasing a number of successful albums including the epic School Days. He teamed up with keyboardist and singer George Duke for the Clarke-Duke Project-- touring and recording a number of albums together including a top 20 pop hit, “Sweet Baby.” Firmly rejecting being pigeon-holed, Clarke plays across genres—including performances with rock and roll giants like Keith Richards, Paul McCartney, and Ronnie Wood. Since the 1980s he’s composed some 70 film and television scores including John Singleton’s Boyz ‘n the Hood, Jet Li’s Romeo Is Dead, and the documentary Halston. He’s led and been part of trios with a variety of musicians while his group The Stanley Clarke Band won a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Album—it’s one of four Grammys and many honors that he’s received. And because Clarke believes in giving back, he established the Stanley Clarke Foundation which awards scholarships to talented young musicians each year. Those are just some of the highlights of his still vibrant career. So when he was named a 2022 NEA Jazz Master, I knew the conversation would be far-ranging. I’m always interested in beginnings, so when I spoke with Stanley we went back, back, back to his upbringing in Philadelphia and his mother’s early nurturing of his musical talent.

Stanley Clarke: Well, my mother was the artist. She was a semi-pro opera singer. Very talented. She was a great painter as well. Just an extremely creative woman. And I think at a young age out of the three of us kids, she chose me to be the one that would go take music lessons and I started taking music lessons at a very young age. I had a short thing with the piano, but although the piano stayed with me up until now, and I started playing bass eventually when I got to the age of 12. Prior to playing bass, believe it or not, I played accordion. The first music lessons I did, I was, "it-da-dit-da-du--" I was doing that sort of stuff because down the street, that was the music teacher. Back in those days in those neighborhoods you had the doctor in the neighborhood. You had the dentist and well, we think he was a dentist. And then you had <laughs> the corner guy that had a storefront that was a music teacher, because it was very important back in those days. So this guy sold a lot of accordions and gave lessons. So I got my foundational music information, believe it or not, from learning the accordion. And eventually I got to the bass and it was things got really serious then.

Jo Reed: What was it about the bass, Stanley, that attracted you, that drew you to it?

Stanley Clarke: Well, in many ways I played the acoustic bass by default. There was an announcement in the school that I went to that said any kids that wanted to play in the orchestra come to the music room at 12:00, 1:00, I forget. I got there late and all the instruments were taken except a bass drum, a sousaphone and an acoustic bass. And I noticed that everyone didn't-- never looked at the acoustic bass. And so I felt-- it felt unique and so therefore I figured, well, if I embrace this instrument, maybe some uniqueness will come to my, you know, my way. And so I grabbed the acoustic bass and my life goal was trying to make it sound good.

Jo Reed: In other interviews, you’ve discussed people in your early life who call “shining lights.” And one of them was Mr. Rossi, your teacher. Tell us about Mr. Rossi.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah, Mr. Rossi was like a very short I used to call him my little Roman friend because he was an Italian guy. And he in many ways is, like, really responsible for a lot of my musical values having to do with education and having to do with preparedness. He was old school. You know, sometimes he was a little rough when my hands weren't in the right position, he had a little paddle.

Jo Reed: Would he really do that?

Stanley Clarke: It wasn't hard. You know, just, you know. No, he was a-- he was a great guy. He really taught me a lot. You know, when I started studying with him I used to come late and he used to sit me down and explain to me about the importance and the purpose of being on time. You know, not just be on time because someone else said to be on time. You know, when you look at how much achievement you're going to have, how fast you're going to rise, I mean if you come late to your lessons all the time, there's things you're going to miss. There's an attitude you're going to have. There's an underlying attitude that may seep into other things like how you practice, how you approach your instrument. And that was very interesting to me. And so I studied with him and I saw my improvement. I would like to think maybe it was, you know, some sort of European approach to it. I don't know. All I knew, he was the only guy I had ever met like that and we remained friends for the longest time.

Jo Reed: Another significant person from that time was Harry Giamo.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah. Well, Harry, Mr. Giaimo, was a really important person to me because when I got to high school there were no high schools for the performing arts and I was really, I was set. My goal, I was going to actually play bass in the Philadelphia Orchestra. I wanted to be one of the first African-Americans in the Philadelphia Orchestra so I was studying classical music. You know, I was in the music room a lot. I really, really, really found something that I was going to do and I approached it very seriously. So there's a little story that I was, you know, I was getting ready to graduate from high school. I had a couple scholarships from various music institutions and I had this one course which was Chemistry and can honestly say, maybe I went there half of the time and I deserved to fail. But Mr. Giaimo, I think he gave the Chemistry teacher an offer he couldn't refuse. <laughs> I'll just put it that way. I got a D-plus and I graduated and I went ono to music conservatory. And the reason why he's so significant to me because he understood me.

Jo Reed: And he introduced you to jazz?

Stanley Clarke: Yes. When we were in high school, he at one point, he said, "You know, have you ever heard much jazz music?" And I said, "Yeah. A bit." And he said, "Did you ever hear Charlie Mingus?" And he showed me a record called "A Clown" by Charlie Mingus. And it had this great picture of a clown on it and it was an acoustic bass player that had a record. I thought that was amazing. Wow. This guy, I was used to, you know, you get a record it's a singer up there with a microphone, you know and here was a guy with a bass. And so I got turned on to Charlie Mingus, Stan Getz and later everyone else. And I really thank him for that.

Jo Reed: When did you start picking up an electric bass and add that to your arsenal as well as the acoustic bass?

Stanley Clarke: The electric bass came around I think it was eleventh grade, somewhere around there. And basically, there were school dances and guys would say, "Hey, man, can you make this gig and play the school dance?" And at first I brought my acoustic bass and I would watch television and see the, you know, in those times The Beatles were coming on television and The Rolling Stones and James Brown. And so I got an electric bass I think for about $15 dollars, $20 bucks. It was called a Kent bass. And I just thought it was cool and I thought I looked better, you know, and my chances of talking to girls, you know, if I had this bass, it looked better than this acoustic bass, at least to me it did. And yeah, it was just a cooler thing and it was really, my first electric bass was really raw. It was-- <laughs> And the amplifiers, you know, you just got the bass, took the wire, plugged it in. Turned it up to 10. Boom and you go. It was fun. And the electric bass still to this day to me is fun. I don't really look at it so much as a serious-- I mean, it is a serious instrument. You can study at any college of music the electric bass. Back in those days, you couldn't. The electric bass was kind of a second instrument to the acoustic bass. But I always had fun. When I play the electric bass, I think of grooving, having fun, you know, playing loud. It's great.

Jo Reed: What do you think of when you play the acoustic bass?

Stanley Clarke: Unfortunately, it's a little more serious. <laughs> I mean, unfortunately and fortunately at the same time because it's a much harder instrument to play, number one. And number two, you have two really distinctive techniques you have to master. If you're a jazz player, you have to master pizzicato with your fingers. But then the other thing, which actually you start out with, is with the bow. And I mean, and that can be just torturous to the ears. I mean, you put a bow on an electric bass, it's oh. In the beginning it's like the cow died, his voice went down two octaves and it's bad. <laughs>

Jo Reed: But when it's good, it's so beautiful. <laughs>

Stanley Clarke: Yeah, yeah. When you get it. I mean, I really stuck with it and I had great teachers. And yeah, I did get it.

Jo Reed: You were 15 when you played your first gig in a club, the Showboat Lounge.

Stanley Clarke: The Showboat. Philadelphia. Yeah.

Jo Reed: With Bayard Lancaster. Tell me that story.

Stanley Clarke: Well, you know, Bayard lived up the street from me maybe three doors up. And he was a really unusual character. He was an avant-garde saxophone player. Sometimes I'd see him walking down the street with clothes that looked like he was in a circus playing the saxophone up in the air like this, just screaming and playing. But then once I sat down and I talked to Bayard and Bayard, Bayard gave me a great lesson. He told me, "You know, you should listen to a lot of different types of music and not for the purpose of liking them." Like a lot of young kids, "Yeah, I'm into this kind of music. I'm into that." So you hear music to have an opinion about it, like it or dislike it. He said, "You should just listen to music just to listen to it and observe that it's here. And if you want to make a point about it in your mind whether it's good or bad, that's your own personal thing, but you should listen." So at that point, I started listening to African music, music from Puerto Rico, music from Cuba, music from Scandinavia, German music, Asian music. I listened to a lot of things. I sort of reserved my opinion about it. So as I got to hang out with Bayard more myself and a friend of mine named Darryl was a year younger than me. He played drums. Bayard was a little crazy. He says, "Listen. You want to do a gig at a world-famous jazz club?" I said, "Oh, yeah. Yeah." So owe go play the Showboat. He put sunglasses on me. I had this suit. <laughs> And my drummer, the drummer was even younger and he put these big wide sunglasses on that he had gotten in Paris and kind of covered the guy's face and we went in. And I remember the club owner kind of looking at us like this but let us go. We sounded great because we were very, had a lot of energy and we had a lot of skills at that age. And it was great. That was my first experience playing in a jazz club. I loved it. I loved it.

Jo Reed: You first played with Chick Correa when you were working with Joe Henderson, correct?

Stanley Clarke: Yeah. Yeah. I had been playing with Joe Henderson. I had started out in New York playing with Horace Silver then I played with Art Blakey and a few others and then eventually Stan Getz and then eventually I played with Joe Henderson. And we were playing a gig in Philadelphia and our piano player couldn't make it a particular week. In those days, you would play one week at a club, 6 days. And so we got there, something happened to the piano player, so Joe said, "I'm bringing this guy down from New York and his name is Chick Correa." So I had heard of him. He had a record out. And I heard he played with Miles and that's about it. And so he came down and it was one of those kind of bonds musically that happened. We really bonded musically. It was almost supernatural in many ways because whatever he did, I knew what he was going to do and vice versa. And so we kind of took over the stage and steered the rhythm sections where we wanted it to go and Joe was just following. <laughs> And, and then it was great and then I, you know, I sort of didn't see Chick for a while and then I saw him later again and a couple things happened and we eventually connected up and started playing together with a group.

Jo Reed: And that was Return To Forever; but I would bet any amount of money you and Chick didn't sit down and say, "Hey, let's start a fusion band."

Stanley Clarke: No, no. I don't think anybody did that.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I don't think so either.

Stanley Clarke: You know, it wasn't that. You know, when I try to explain that period to people, I have to be very specific. You know, you had guys like myself, Larry Coryell, Chick Correa, John McLaughlin, Billy Cobham, all the guys, yes, we grew up and we listened to Coltrane and we listened to Miles, but we also listened to Jimi Hendrix and we listened to James Brown. Some of us listened to The Beatles. I was a sort of a Rolling Stone fan so when the time came for us to make music, when we made those records I used to get a kick out of the jazz critics that used to put us down, that music, as if we were being dishonest. And in actual fact, we were the honest ones. We were-- <laughs> We were putting everything out there. And also Chick and myself had a pretty healthy classical music appetite so our records had compositions. That's kind of what distinguished Return To Forever. We would get together and sit down, take a month off and write our compositions and you know, pencil and you know, the old-fashioned way and really did it, come in and rehearse. And so I used to get a kick out of that. That music was exactly what we were into at that time.

Jo Reed: When did you start composing?

Stanley Clarke: I started probably right out of high school.

Jo Reed: During that time in the beginning with Return To Forever, you really helped transform the sound of the bass and the place of the bass in a band. Typically the bass had been the centering instrument, if you will. You know, it kept the rhythm. It's where the rhythm and harmony could meet. But you expanded that into playing melodies.

Jo Reed: Yeah. Well, you know, I kind of looked at all my favorite bass players were like kind of like in the center of a concentric circle. Like the guy was right in the middle and there were all these rings and maybe a trumpet player was on one of the rings and the piano player. Maybe a singer here, a drummer there. And I always thought that music would be much more interesting if you could jump around on the concentric circle and maybe go to the outer ring, go to the third ring or maybe stay in the middle. Maybe put someone else in there. And so that's what I did. And then also I had ability to play the bass. I was studying the most I think complicated stuff I could think of at that time on the acoustic bass, so I didn't want to just sit and go boom-boom-boom-boom, you know. So I wanted to play some other things. And then and it's funny you mentioned composition, I actually believe that a really decent percentage of an artist, how he plays, has a lot to do with his compositional skills, whether he writes it down or it's just in his head. Because, you know, if you're thinking something, you're composing it. It doesn't necessarily have to be written out. And so I was always thinking of tunes and I used to say, "You know, what about that melody being played on the bass? I wonder how that would sound?" And I was fortunate enough to be able to write it down so I would put bands together as a young kid and we'd get the bands and we'd start rehearsing and they'd say, "Okay, who's going to play the melody?" I'd say, "I'm going to play the melody." "Get out of here. You're kidding." Yeah. And so that's how a lot of that started.

Jo Reed: I'm paraphrasing you and probably badly, but you said something to the effect of musicians need to know technique. They have to have the fundamentals but then you have to let it go and just be wild at heart.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, there was a great thing that Charlie Parker said which is, you know, study, study, study. Study, study, study and more study and then forget it. And that's him.

Jo Reed: Did you have to learn to forget it? Or was that something that came pretty naturally to you?

Stanley Clarke: That was pretty easy for me. Because I mean, you know, when you do serious studying, there's an element of struggle and pain. <laughs> And especially the acoustic bass. And I was glad to let it go. And then I just, you know, I have this stuff that's in my universe, you know, and it comes out when I need it, you know. But believe me, I prefer being like a free spirit musically. That's another thing about Chick Correa that's not-- I'm not sure whether it's known, but you know, he was a guy his favorite thing to do is just jump up on a stage with no music, with nothing, with guys that he knew musically and just play. It was like a clean canvas and you just go up and you do it. And I mean, what better way to create than that?

Jo Reed: That art of improvisation, what Roscoe Mitchell calls spontaneous composition.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah, yeah. I mean, you know, he's God. He's one of my favorites. I mean, you know, when you look the word composition up, you know, there's some dictionaries had, you know, when it pertains to music they reference paper and a pencil. But it's really, it really doesn't have anything to do with it. The notation of it is just so you can have a picture of it. You know what I mean? It's the only way you can, like, really snap a snapshot of something, so you put it down there and then you can give it to someone else too play. That's the only purpose of notation is so someone else can play this idea you had yesterday. <laughs>

Jo Reed: Well, to state the obvious, Return To Forever was massively successful. You made 7 albums. You did lots of touring. The music you made was wonderful-- is wonderful, because music lives forever. And then you began a solo career and you're making solo records with the bass front and center. One of your solo albums is "School Days" which was epic, both the album and the song itself was huge. And I read somewhere that originally you thought the bass on it was too loud?

Stanley Clarke: I actually did. You know, I recorded the song with a great engineer. This was my third album I did with this engineer. His name was Ken Scott. He was an English engineer. I liked using him because his sounds were really sophisticated. He had worked on The Beatles' "White Album." He recorded David Bowie albums. So we did a record "School Days" and, you know, I was very much like a jazz musician. I didn't believe in overdubbing solos. The song went down, that was our-- The first take we had to stop halfway point because the drummer kicked the mic or something. So then we did the second take and that was the song and I told the guys, "No, you don't fix. Just this is going to be honest." Ken was a great engineer. His playbacks was his thing and he made the playbacks sound like records. So I came in and I heard this bass, I said, "Man. Damn, you got to turn the bass down." And he looks at me in a heavy, heavy English accent he says, "The bass is never too loud." I go, "I like that." So I just <laughs> kind of let it be and that record came out and as you say, it was an iconic record. Kind of a bass anthem. And I was very fortunate. You know, when I wrote that song it was interesting, because Return To Forever was winning a Grammy and I was so excited because I didn't know much about the Grammys. You know, we were jazz musicians. We played for 100 people in a club, live in a small apartment, didn't expect much. You know, I was about the music. I expected I'll be 80-years-old in this apartment here. But anyway, that didn't happen. <laughs> But the point being is I was so happy after that. I had the bass with me and I remember playing the line to "School Days." Because it's a very uptone line, very happy. And so I played that and I wrote it down, because in those days none of us could really record at home, so I wrote the thing down. And in the morning I put the B section and just finished the song and put it away and I was going to record it again. So I took it in the studio, record it. My hardest problem was always giving song's titles. So I couldn't call the song, "I Just Won A Grammy." That wasn't going to work.

<laughter>

Stanley Clarke: So, well, there was a guy named Ron Moss who later managed Chick Corea. So he asked me the right question. He says, "Well, does it make you feel like?" I said, "Happy." He says, "When were you happiest?" "When I was in school." I was very happy when I was in school. He says, "Well, let's call it 'School Days.'" So we called it "School Days" and that was that.

Jo Reed: In "School Days," when you play the bass you use a slap technique. You sort of incorporate that into the structure of the song. Can you describe that and how you got there.

Stanley Clarke: Well, the slap technique, it actually comes from the bass player Larry Graham who played with Sly and the Family Stone and believe it or not, the drummer, Lenny White, showed me how to slap on the bass. A lot of people think that I invented this thing. Not true. And many think that I just woke up one day and it just like just sort of appeared on my fingertips and it didn't. You know, I had heard Larry do it and I thought, "Wow. That's really something." And Lenny says, "Yeah. Let me show you." And then he did a very primitive way. It didn't sound that great. But I saw what he was trying to do there. And I figured it out and figured my own way of doing it. And it was just sort of another thing for the arsenal there, I'll put it that way, another technique.

Jo Reed: Yeah. Another tool in the toolkit.

Stanley Clarke: Exactly.

Jo Reed: So meanwhile, you have your solo records. You've worked with Return To Forever. You're doing jazz. You're doing fusion. You clearly don't care about labels because you then begin playing some not just rock and roll but with some of the best rockers around. You're playing with Keith Richards and Ron Wood and Stewart Copeland and Jeff Beck. Can you just talk a little bit about that time and what that was like and how different was it from playing the 100 people in your jazz club?

Stanley Clarke: Well, it was great. You know, I think there is this sort of a thought that's really not true. You know, jazz musicians, rock musicians, country musicians, classical musicians, because we play different music and there's different genres there is the idea that we don't talk to each other or not play with other and it is really incorrect. I mean, we're all friends. I met Paul McCartney a long time ago. We were playing at the some club in London called Ronny Scott's and Paul came. And same with Mick Jagger. Our early days in Return To Forever, we were playing a little club called the Village Vanguard in New York and Mick Jagger showed up with the head of Atlantic Records at that time and they said, "Yeah, yeah. We're playing over at the Madison Square Garden. You know, let's hang out after the gigs." It's just like the gigs. You know, we're here, they're there and you know, Stewart Copeland, I've known him way before the Police. We go way back. There's a lot of musicians that I know. And so the idea of playing different types of music, a lot of it for me had to do with friendship. I don't think musicians really look at, "Oh, now I'm going to play with a country musician or, oh, now I'm going to do this." You know, if someone wants you to play, they like your playing and you like them, that person musically or you like the person, you know, you go do the gig and let it roll. You know, providing you can play that music, you can play that genre of music. I've never really defined myself within a genre of music. I play bass. I play the bass.

Jo Reed: And you've played with many people. You and George Duke played on a number of projects together. Can you describe his musicality and how it fit with yours? How it complemented yours, you complemented each other? You made some great, great music together.

Stanley Clarke: Well, you must have read my mind. That's a great example of playing music because you're friends. I met George in Finland 1971 and we became friends and that night we jammed and all that sort of stuff. And especially when I came from New York to Los Angeles, we started doing records with each other and we found ourself playing on records together. And he was a friend. A really cool guy named Vernon Slaughter at Epic Records said, "You know, you guys hang out so much, you should make a record. We'll call it the Clarke-Duke Project." The record was gigantic and we had a hit single because George was a great singer.

Jo Reed: "Sweet Baby."

Stanley Clarke: "Sweet Baby" was like a top 20, top 10 single.

Jo Reed: Yeah. It's a great song.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah. It was a great song and we had fun.

Jo Reed: Let me ask you, take the Stanley Clarke Band, your band that you're leading, what do you look for when you're looking for people to be part of that band?

Stanley Clarke: Well, first and foremost, they can play the charts. You know, the some of the charts are a little difficult. And so the guy has to be able to play that. And if he has a great personality, it's perfect. That's really pretty much it, you know. I like young players. I like to pass down, you know, what I've learned because that was done to me when I played with Stan Getz, particularly Art Blakey. That's probably out of all the older bands I've played with, the one I'm the most proud of is Art Blakey because so many people went through his band. Even though they don't mention it much online, but myself and Chick Correa, we were Jazz Messengers, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. And I mean, everybody-- From Wayne Shorter, Lee Moore, all kinds of people went through his band. And I think it's because we didn't record with him much that we're not mentioned, but I was there. I toured with him for about a year. And I learned so much from him. He was crazy. But man, there was a wealth of information there.

Jo Reed: You've played with some great, great drummers. You still do. I'd love to have you talk about that relationship you have with Lenny White, who you've played with practically your entire professional life.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah. Yeah, Lenny, Lenny's one of those musicians that like Chick, whatever he does, I know what he's going to do and vice versa. It's really interesting, you know. You know, music is like language and once you understand a person's language and even the sublanguage that's' within the language. We're playing jazz, but that person has a particular way that he plays, that he takes that language. Kind of like slang, you know. And once you understand that, man, the sky's the limit with that person. It's a beautiful, beautiful thing. I have that with Chick. I have that with Lenny. A few other people.

Jo Reed: What’s the difference for you between recording in a studio and performing live?

Stanley Clarke: Well, you know, recording in a studio, if we're playing a chart and you're playing something for the first time, it has its good points because you're playing something new; if you're in there with some new guys, it's great. You know, and then you have the advantage of having great sound. But you know, when you're playing live there's so many other advantages musically because of you have a great audience, you have the interplay, the energy. A lot of energy. And then you have the idea of spirit of play where you have people playing off of each other so it's you have all these different things. And then you don't have the time constraint. I did a lot of studio work when I first came to New York. Played on a lot of records. And, you know, you have to learn how to be able to, like, shine immediately like snap of a finger. Bang. You're right there. You know, playing live sometimes you can take time, you know, you can do a lot more things, longer, play longer. You can take the time to roll something out. It's great.

Jo Reed: And you also did Forever with Chick Correa and with Lenny White, and that was, two disks, but the first disk is recorded live from concert appearances.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah. Yeah. You know, that was kind of a collection of all kinds of different things. I mean, some of that stuff was just rehearsal. We were rehearsing to play at the Hollywood Bowl and we were in a studio and we just rolled the tape and recorded everything. I think we got some Grammys for that.

Jo Reed: Indeed, you did. And the bowing you did on "Sofia."

Stanley Clarke: "La Cancion de Sofia."

Jo Reed: Is so gorgeous.

Stanley Clarke: Thank you. Yeah, it's a nice piece, song for Sofia. Sofia, my wife, you know, she likes it when I play with the bow and so I was working on some of the Bach Cello Suites, you know, she would always come in and go, like, "That's not quite right yet." <laughs> And so I said, "I'm going to write a Sofie song." And so I did.

Jo Reed: You also got this super group together Three Basses with Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten.

Stanley Clarke: Yeah, that was one of those kind of almost provocative ideas, you know. Three basses and three premier basses and we went around the world and I mean my God, so many people came out to see us. And all the promoters were afraid. They thought we were going to just blow up their PA system, We played maybe 25 shows in Europe and maybe 10 in the United States. Anyway, what we did was we devised a really amazing way so that wouldn't happen. We fazing. So we had Marcus Miller's bass right down the middle, Victor Wooten's bass was to the left and I was stage right. So all three basses were never in one area at the same time, you know, that the speakers would start to have convulsions, you know, and just blow up. And we went all through Europe and it was great. It's all on YouTube, great shows. Tremendous.

Jo Reed: Well, you have this whole other career as a composer for television and movies. And it all began in a very unlikely place when you wrote some music for "Pee Wee's Playhouse" and the rest is history.

Stanley Clarke: Well, "Pee Wee's Playhouse," well first of all, that show was an interesting show. Like, they had different composers come in for different episodes. I received an Emmy nomination for that. So I thought, wow. That's pretty good. It was like a daytime Emmy nomination. And then a film composing agent contacted me and said, "You know, hey, you know, you're definitely pretty good at this sort of thing. Why don't you do some other things?" And then I started doing some other shows and never looked back. Been doing it ever since.

Jo Reed: You have a band. You have a solo career. Why did you want to move into scoring for films

Stanley Clarke: Well, film composing is an interesting-- I think I can still call it an art form. But it's something that combines a lot of different skills. Like obviously you got to be able to write music. You have to have a mathematical mind because you're dealing with picture and so maybe you have to write from here to here. And if you're doing an action picture, I remember once I was doing a Jet Li movie called "Romeo Must Die" and I had to write this music and you have to catch when the guy's leg kicks through a door or he kicks a guy in the head. So you have to measure all that out. And at the same time, it has to sound musical. And so there's a way to do that, you know, where you pick the right tempo, like you pick all the different spots. Say there's three spots, the guy kicks here, he falls down here, another guy, whatever. And you can pick the right tempo where each one of those things happen on the beat or off the beat or something. And so there's a mathematical way to do that. So you have to kind of have that together. Also, there's social skills. When you're doing a movie you're going to be dealing with particularly a director maybe for two months. Guy has to know that he can like you, he has to know he can talk to you. (laughs)

Jo Reed: Well, clearly, you and John Singleton were able to talk. You scored a few films for him.

Stanley Clarke: I did his first three movies. And then we did a couple other things too.

Jo Reed: And it began with “Boyz ‘n the Hood.” What do you remember about that film.

Stanley Clarke: “Boyz ‘n the Hood” was much like a script that you would expect from a guy in college, like a college film. It was very like humble, very sober. You know, just it didn't have a lot of bells and whistles. So I remember reading it going, "Wow. Okay." You know, but when John got to shoot the movie, I understood the purpose of his scripts. His scripts were just his framework because then when you got, you know, all this other stuff, this flavor of the hood, the way people talk, the way they moved, which was not written in the script because he couldn't. It would be stupid to write that stuff in there. So you know, so I started writing the music from the script and then when the movie came, when the movie came to me, it was interesting taking some of that music and laying it up against the picture and I was surprised that a lot of it worked. It's a wonderful art form. I tell you, some of the smartest people I've ever met make movies because it's an interesting thing. It's kind of like you're deciding to create life but in a parallel universe. That's a cool thing.

Jo Reed: Well, a couple of years ago, you were the artist in residence at the Detroit Jazz Festival. And you actually conducted a 60 piece orchestra performing the score from “Boyz ‘n the Hood” the soundtrack as the film played. That had to have been interesting and kind of daunting. I would have been daunted by it.

Stanley Clarke: That was probably technically the hardest thing I ever did. We said yeah and so,I was going to do three nights, so I did one night was a jazz night, straight ahead. The second night was fusion and the third night I'm going to conduct this 60 piece orchestra and we're going to show 9 really significant scenes out of “Boyz ‘n the Hood.” Never did we think how are we going to do this. Like what are we going to do? So my guy that works in my office and my engineer who's a bright guy, we really had to construct this whole design how to do it. And then fortunately, we found people that had done that before. We had these huge screens. It was in kind of an amphitheater downtown Detroit. And so it had to be big enough, the sound had to be right. The orchestra was there. We had to provide sort of a click track for the orchestra so they'd be in synch with the picture. And I had to have communication devices like headphones to communicate. And then the mixers were back there. One guy mixing the orchestra and then we had, like, a rhythm section with it and it was pumped up. And I tell you what, it came out perfect. And when I came off the stage, I think I had lost 5 pounds. And I remember saying, "This is beginner's luck. If I had to do this all over again, it would be a complete disaster." You know, this was one of those moments. It was really magical. And what was nice about it was because it was one of those movies that I had never realized. I mean, I've done I forget how many movies now, TV and feature films. It could be close to 80, 70-something. Somewhere up there. And but I didn't realize what that movie meant for a lot of people. I sometimes forget that as a film composer and as a film maker, a part of making a film, if you're lucky enough to contribute to films that mean something, you affect a lot of people. And John Singleton's movies said something about something and directed towards his audience, you know. And so that was nice. And it just reminded me just the importance of any creativity, any creative act. If it's directed at people and it has a positive message hanging on that, it's incredible. It's the best thing. I mean, that's what we need on this planet. We need more of that.

Jo Reed: And you have an educational fund, the Stanley Clarke Foundation.

Stanley Clarke: Well, that's something that's been going on about, I don't know, 15, 16 years. I don't know. We've sent a lot of people to higher education in music. We've been raising money quietly. It was not something that we wanted to make a big deal about, me and the wife. And during the year many people would apply to the scholarship from all over the world and they'd come in once we did a process of elimination and we had 5 finalists and then we'd have a concert. And they'd come and they'd play. And the difference between our scholarship foundation and others is that everybody wins. The top 2 people get the biggest, the most amount of money. Then the next person gets a certain amount of money. And then the last 2 get cash and to do whatever they want to do with it, a significant amount of cash. And the reason why I did it was because I remember when I was going to a music conservatory in Philadelphia, my biggest problem was just having money. You know, playing the bass is, you had the rehair the bow, buy rosin, the strings were really expensive. And I had an apartment, $35 dollars a month. Food. You know, it was just at that time, it was just that was a lot for me. And so I remembered that and I remember kids that go through that kind of hassle. So we gave cash awards. And so it was a very festive, very happy thing. All the people you mentioned, like Stewart Copeland, all those guys come down. Sheila E. Flea. You know, a lot of people come down and we'd have a great time and we'd play, all the judges would play. Then we'd play with the kids and it was a lot of fun.

Jo Reed: Stanley, let me ask you finally, you have got four Grammys, many other awards. The Key to the City of Philadelphia. And now you're named an NEA Jazz Master. And I really would like to know what that means for you.

Stanley Clarke: Well, you know, awards in general mean a couple things to me. one, you know, I was a guy that started something many years ago and all I knew was just to work. And the next day work and work and work. And sometimes it's nice to be acknowledged, you know. And if it comes in the form of an award, that's great. Now there are some awards that mean more than others. Like this award means a lot because it's a I think it's is it one of the highest awards you can get as a jazz musician?

Jo Reed: It's the highest honor the nation gives to jazz musicians.

Stanley Clarke: There you go. <laughs> That's special. It's, you know, it's great. It's in the form of an acknowledgment. It makes you think of your life, you know, and retrospect all the things that you've done. And it's nice that people are out there that are, you know, caring, observant enough to recognize something that you've done and, and award you something. It's wonderful. Thank you.

Jo Reed: And so well deserved. Many, many congratulations, Stanley and thank you for giving me your time.

Stanley Clarke: Thank you.

Jo Reed: That was bassist, composer and 2022 NEA jazz Master Stanley Clarke. The concert honoring the NEA Jazz Masters took place at SF Jazz on March 31, and you can watch, listen and enjoy it, in its entirety at arts.gov. You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us on Apple or Google Play and leave us a rating, it helps people to find us. Next week, I’m speaking with poet Huascar Medina—be sure to listen. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening.

###

Related Video

NEA Jazz Masters: Stanley Clarke (2022)

https://www.npr.org/2022/04/21/1093770637/stanley-clarke-the-virtuoso-bass-doubler-is-now-an-nea-jazz-master

Stanley Clarke performs at the Jazz Festival Basel, on November 1, 2017 in Switzerland. Goffredo Loertscher/WBGO

Stanley Clarke's prolific output can take you back to medieval times, soothe you with a gentle bow of the bass, or launch you into an interplanetary future. His playing holds a reckless abandon, clarity, and facility rarely heard on the low end.

Clarke, a 2022 NEA Jazz Master, spent his formative years in Philadelphia and came up playing with local saxophonist Byard Lancaster, who snuck an underage Clarke into the clubs. Soon, he was picked up by heavyweights like pianist Horace Silver, drummer Art Blakey and saxophonists Stan Getz and Joe Henderson. A lifelong friend and collaborator, drummer Lenny White, helped him get the gig with Henderson, which is also how Clarke would meet Chick Corea.

By that time he was playing — had mastered — the electric bass, and he and Corea co-created the album Return to Forever. The band capitalized on Clarke's ability to double on both acoustic and electric and catapulted his career far outside the confines of jazz. To date, Clarke has racked up more than 50 albums as a leader and co-leader, and more than 150 albums as a sideman with artists like Dianne Reeves and Paul McCartney, in addition to scoring films like Boyz n the Hood and The Transporter.

- "Bass Folk Song" (Stanley Clarke)

- "No Me Esqueca" (Joe Henderson)

- "After the Cosmic Rain" (Clarke)

- "Dayride" (Clarke)

- "Romantic Warrior" (Live) (Chick Corea)

- "Detroit" (Joe Henderson, Stanley Clarke, Cameron Graves)

In this episode we hear from Lenny White, who says that playing on Return to Forever with Clarke was different because, despite the band borrowing from rock, the two had experience in straight-ahead jazz: "So it was like putting on a pair of [dress] shoes, and then taking us out and putting on a pair of sneakers."

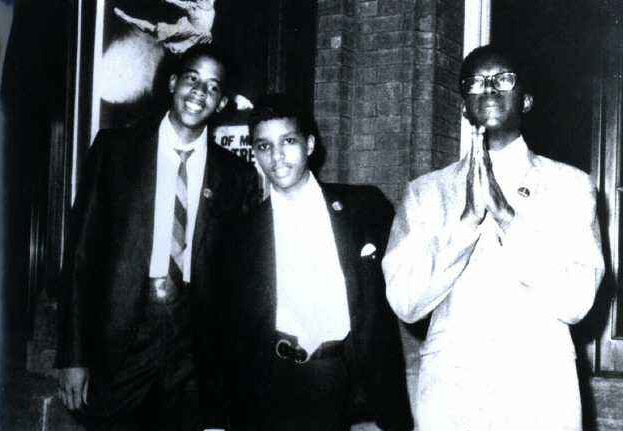

The show also features a moment from Los Angeles-based pianist Cameron Graves, known for his work with saxophonist Kamasi Washington. Clarke says that it's a musician's duty "to find that special person that has some really, unusually tremendous talent and help that person." Like Byard Lancaster and Joe Henderson had with him and he later did with Graves, who he also brought into his own band. Now, to date, Clarke and Graves have helped mentor dozens of budding musicians through his Stanley Clarke Scholarship Foundation.

Full circle: Graves first saw posters of Clarke on the walls of his high school. "He looked like a rock star," Graves remembers. "He reminded me of Jim Kelly ... from [Bruce Lee's] Enter the Dragon."

We'll hear the two in an intimate acoustic arrangement from an NPR Music taping at the 2017 Detroit Jazz Festival.

Musicians:

"Bass Folk Song" from Children of Forever by Stanley Clarke

Stanley Clarke, bass; Arthur Webb, flute; Chick Corea, keyboards; Part Martino, guitar; Lenny White, drums

"No Me Esqueca" from In Pursuit of Blackness by Joe Henderson

Joe Henderson, tenor saxophone; Curtis Fuller, trombone; Pete Yellin, alto saxophone; George Cables, electric piano; Stanley Clarke, bass; Lenny White, drums; Tony Waters, congas

"After the Cosmic Rain" from Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy by Return to Forever

Chick Corea, keyboards; Stanley Clarke, bass; Bill Connors, guitar; Lenny White, drums

"Dayride" from No Mystery by Return to Forever

Stanley Clarke, bass; Lenny White, drums; Al Di Meola, guitar; Chick Corea, keyboards

"Romantic Warrior" (Live) from Returns by Return to Forever

Chick Corea, keyboards; Stanley Clarke, bass, Al Di Meola, guitar; Lenny White, drums

"Detroit" from the "Night Owl" NPR Music series

Cameron Graves, piano; Stanley Clarke, bass

Set List:

Credits: Writers and Producers: Camilo Garzón and Alex Ariff; Consulting Editor: Katie Simon; Host: Christian McBride; Project Manager: Suraya Mohamed; Senior Director of NPR Music: Keith Jenkins; Executive Producers: Anya Grundmann and Gabrielle Armand.

Special thanks to 1504 Productions, Josephine Reed, and the team at National Endowment for the Arts.

https://stanleyclarke.com/stanley/

STANLEY

Long before he became a four-time Grammy Award-winning recording artist, performer, composer, conductor, arranger, producer, a composer for recordings and film, as well as one of the most celebrated acoustic and electric bass players in the world, Stanley Clarke was a student. Stanley’s “school days” were not only the inspiration for his world-renowned bass anthem, but essential to the origin story of the pioneering bass virtuoso from the streets of Philadelphia.

In his early teens, Stanley moved from the violin, his fingers were too big for, and the cello that never sat well with him, to an abandoned acoustic double bass in the corner of a school band room. It was the first of many moments that would shape his future and the role of the bassplayer for years to come.

With the guidance and encouragement of teachers like Eligio Rossi at the Settlement Music School, Stanley steadily developed technique and confidence on the bass. The tall, sports-minded kid began spending as much time on the bass as the basketball court, perfecting the mastery of the classical music repertoire he was studying, with aspirations of one day playing in his city’s symphony orchestra.

Stanley made his professional debut at 15-years old, when he was invited by saxophonist Byard Lancaster to join him for a week of shows at the landmark Showboat Lounge, where many of the greats like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Art Blakey, Stan Getz and others would play and record. The gig, for which Stanley and drummer Darryl Brown were paid about $75, was an experience which sparked the flame of inspiration that would propel the nascent ambitions of the young bassist like a rocket.

With the arrival of the British Invasion bands and his Roxborough High School years, the electric bass, a Kent electric bass purchased for around $50, found its way into Stanley’s hands and so did opportunities to play parties and shows with many bands across the City of Brotherly Love.

Upon leaving the Philadelphia Musical Academy (now part of the University of the Arts), Stanley made his way to New York City where he very quickly landed opportunities to work with such greats as Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Dexter Gordon, Joe Henderson, Pharaoh Saunders, Gil Evans and Stan Getz. He would also find himself playing again with Chick Corea. The two had met when Chick came to Philadelphia to sit in for a keyboard player in a band in which Stanley was playing. Almost immediately, the two recognized something in the talents of the other that night that would form the basis of their musical friendship and the creation of the groundbreaking jazz-rock fusion unit, Return to Forever.

RTF, which became one of the seminal bands of the fusion era, included Lenny White on drums, Billy Connor, and later, Al Di Meola on guitar. The musical personas, compositional skills and virtuosity of each player elevated the band and informed its enormous success and popularity. The group would tour the world many times over, achieving the kind of devoted following once reserved exclusively for rock bands.

Stanley’s spellbinding dexterity on the bass was getting noticed whenever and wherever he performed. He was soon signed to Nemperor Records, co-founded by The Beatles manager, Brian Epstein. The release of his self-titled Stanley Clarke in 1974 and the widely regarded School Days two years later, took the world by storm, transforming the bass into a melodic and harmonic lead instrument, as never before. Stanley’s hypnotic, innovative approach to playing the instrument liberated the bass from the back to the front of the stage. In the process, he became the first jazz-fusion bassist to headline tours, sell out shows worldwide and have recordings reach gold status. His talent and success directly influenced and inspired a whole generation of bassists who followed in his footsteps.