SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER THREE

MARC CARY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

REVOLUTIONARY ENSEMBLE

(June 11-17)

OLU DARA

(June 18-24)

WALTER SMITH III

(June 25-July 1)

BOBBY WATSON

(July 2-8)

JAMES MOODY

(July 9-15)

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

(July 16-22)

LEYLA McCALLA

(July 23-29)

GREG LEWIS

(July 30-August 5)

RUSSELL MALONE

(August 6-12)

JOHN HANDY

(August 13-19)

STANLEY CLARKE

(August 20-26)

JASON HAINSWORTH

(August 27-September 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/leyla-mccalla-mn0002886373/biography

Leyla McCalla

(b. October 3, 1985)

Biography by Steve Leggett

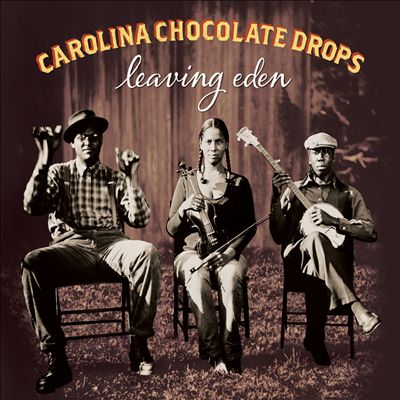

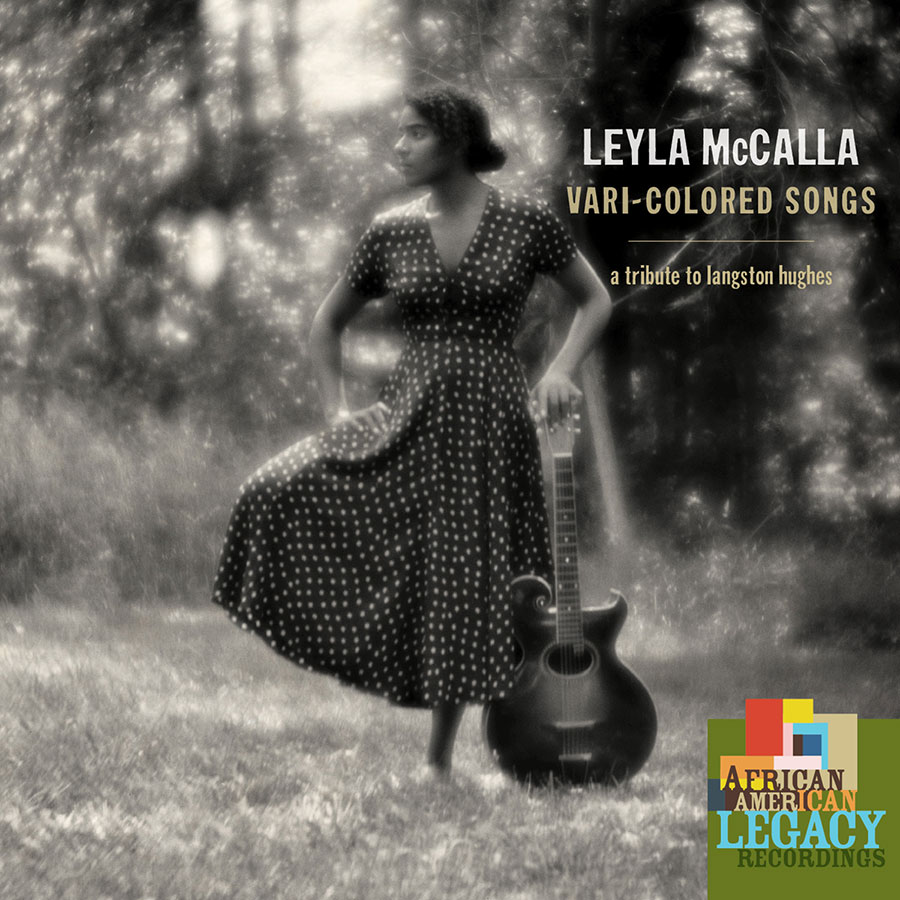

Haitian-American singer, songwriter, arranger, cellist, and multi-instrumentalist Leyla McCalla combines folk, jazz, and classical elements with the Louisiana musical traditions of her adopted New Orleans home. A member of the string band Carolina Chocolate Drops from 2011 to 2013, she appeared on the Grammy Award-winning group's fourth studio album, Leaving Eden. She issued her debut solo effort, Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes, in 2014, followed by a string of innovative releases, including 2022's multidisciplinary music, dance, and theater work Breaking the Thermometer. In addition to her solo work, McCalla is a member of the folk and roots music supergroup Our Native Daughters.

Leyla McCalla was born in New York City to Haitian immigrant parents, raised in a New Jersey suburb, and then spent two years in Ghana as a teenager, returning to the U.S. to attend Smith College before moving on to study cello performance and chamber music at New York University. Not afraid to gamble, she relocated to New Orleans after college, intent on busking with her cello in the French Quarter. She fell in love with Louisiana Creole culture, particularly fiddlers like Canray Fontenot and Bébé Carrière, whose styles she began to explore on the cello. While playing on the street, McCalla met Tim Duffy, director of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, who in turn introduced her to the Carolina Chocolate Drops string band.

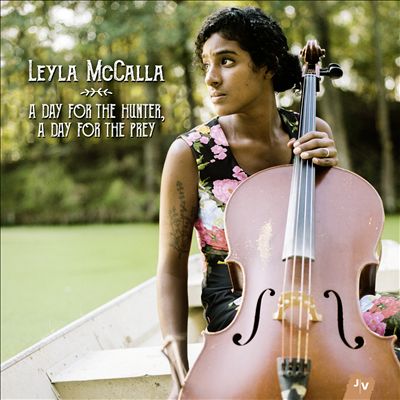

After touring with the Chocolate Drops and appearing on the group's Leaving Eden album, McCalla began to concentrate on a solo career. Her debut album, Vari-Colored Songs, a tribute to Langston Hughes, appeared in Europe in 2013 and was named album of the year by both the London Times and Songlines magazine. It was issued internationally by the Music Maker Relief Foundation in early 2014. McCalla toured the U.S, Europe, and Israel in support. The title of her sophomore effort, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, was ultimately derived from a Haitian proverb. It featured songs in English, French, and Haitian Creole, with appearances by Marc Ribot, Rhiannon Giddens, Louis Michot of the Lost Bayou Ramblers, and New Orleans singer/songwriter Sarah Quintana. The set was issued by Jazz Village in May 2016.

2019's Capitalist Blues saw McCalla enlist Jimmy Horn of King James & the Special Men to produce a wide-ranging set of bustling songs that embraced Haitian, Brazilian, Cajun, zydeco, and calypso styles. That same year, she teamed up with Rhiannon Giddens, Allison Russell, and Amythyst Kiah under the banner Our Native Daughters and issued the acclaimed Songs of Our Native Daughters on Smithsonian Folkways. 2022's innovative Breaking the Thermometer combined original compositions with traditional Haitian tunes and historical broadcasts from the country's first Kreyòl-speaking radio station.

Leyla McCalla

Leyla Sarah McCalla[1] (born October 3,[2] 1985)[3] is an American classical and folk musician.[4] She was a cellist with the Grammy-winning[5] string band Carolina Chocolate Drops[6] but left to focus on her solo career.[7]

Background

Both of McCalla's parents were born in Haiti.[6] Her father Jocelyn McCalla[8] was the Executive Director of the New York-based National Coalition for Haitian Rights[9] from 1988 to 2006[10] and is credited as translator on her album Vari-Colored Songs.[11] Her mother Régine Dupuy arrived in the United States at age 5, and is the daughter of Ben Dupuy who ran Haïti Progrès, a New York-based Haitian socialist newspaper.[9] McCalla's mother went on to found Dwa Fanm, an anti-domestic violence human rights organization.[9] McCalla's younger sister, Sabine McCalla, is also a musician in New Orleans.[12][13]

McCalla was born in Queens, New York City, and raised in Maplewood, New Jersey,[14] where she attended Columbia High School.[15][9] She lived in Accra, Ghana for two years as a teen. After a year at Smith College, she transferred to New York University to study cello performance and chamber music. In 2010 she then moved to New Orleans[9] where she honed her craft playing music on the streets of the French Quarter. In addition to cello, she also plays banjo and guitar.[15]

Career

From 2011 to 2013, McCalla was a member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops.[16] As of 2019 she is a member of Our Native Daughters.

As of 2017, McCalla was touring with her New Orleans-based trio, which also included her Québécois husband Daniel Tremblay on guitar, banjo, and iron triangle (ti fer); and Free Feral on vocals and guitar.[16]

As of 2019 into 2020, McCalla has been touring with her Leyla McCalla Quartet, which also includes New Orleans musicians Dave Hammer (electric guitar), Shawn Myers (drums/percussion), and Pete Olynciw (electric and acoustic bass).[17][18]

First album

McCalla's critically acclaimed album Vari-Colored Songs is a tribute to Langston Hughes which includes adaptations of his poems, Haitian folk songs sung in Haitian Creole,[4] and original compositions.[6] McCalla says the first song she wrote for the album was "Heart of Gold" because it provided "a window into Hughes' thinking".[19] McCalla chose to dedicate this work to Hughes because she says "reading his work made me want to be an artist."[6] McCalla started working on the album 5 years prior to its release.[6] Commentators have noted the influence of Louisiana musical traditions such as old Cajun fiddle melodies and trad-jazz banjo on the album.[5] Members of the Carolina Chocolate Drops appear on the album.[5] The album was financed at least in part through a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter which exceeded its goal of $5,000 to raise $20,000.[15]

Personal life

As of 2019, McCalla is married to fellow musician, and electrician, Daniel Tremblay. They live in the New Orleans area and have three children.[9][16][20][21]

Discography

- Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes[19] (February 4, 2014, Music Maker[6])

- A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey (May 20, 2016, Jazz Village/Harmonia Mundi)

- Capitalist Blues (January 25, 2019, Jazz Village/PIAS)

- Breaking The Thermometer (May 6, 2022, ANTI-)

Collaborations

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Leaving Eden (February 24, 2012, Nonesuch)

- Our Native Daughters: Songs of Our Native Daughters (February 22, 2019, Smithsonian Folkways)

External links

Kanaval: Haitian Rhythms And The Music Of New Orleans: Episode 1

A sketch map of Saint-Domingue, a French colony in the Caribbean from 1659-1890. Following a revolution by enslaved Africans, the territory was declared the Republic of Haiti. Archive Photos/Getty Images

Listen To Our Kanaval Documentary

In order to understand the deep connections and musical relationship between Haiti and New Orleans, we must go back to before Haiti was Haiti.

The island was a French colony called Saint-Domingue, prized for its money-making prowess from sugar and coffee crops. Sugar was extremely lucrative, but its production was punishing. In order to maximize profits, the colonists' economic model entailed working slaves literally to death and then replace them with newly enslaved Africans.

These conditions enforced brutal slave labor by a recently enslaved population, in an era alive with revolutionary ideas. Eventually, they yielded just that: a revolution.

Explore xpnkanaval.org for even more on the documentary.

Kanaval has been supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support from the Wyncote Foundation.

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/976648559/976840589" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

https://www.anti.com/artists/leyla-mccalla/

Leyla McCalla

There are more questions than

answers on Leyla McCalla’s remarkable new album, Breaking The

Thermometer. What does democracy look like? Who does it work for? How

long can it last? On its surface, the record explores the legacy of

Radio Haiti—Haiti’s first radio station to report the news in Haitian

Kreyòl, the voice of the people—as well as the journalists who risked

and lost their lives to broadcast it for nearly 50 years. But on a more

fundamental level, the collection is a deeply personal reckoning with

memory and identity, with the roles of artists and activists and

immigrants in modern society, with the very notion of storytelling

itself. In delving into the project, McCalla found herself forced to

grapple with her own experiences as a Haitian-American woman, unraveling

layers of marginalization and generations of repression and resolve as

she searched for a clearer vision of herself and her purpose. The result

is at once a work of radical performance art, historical scholarship,

and personal memoir, a wide-ranging and powerful meditation on family

and democracy and free expression that couldn’t have arrived at a more

timely moment.

“The more I researched this project, the more I

found myself examining my own sense of Haitian-ness,” McCalla reflects.

“I spent a lot of time recalling my experiences visiting Haiti as a

child, thinking deeply about the moments in my life when I felt very

Haitian and the moments when I didn’t. In the end, the music and the

stories here all brought me to a more nuanced understanding of both the

country and myself.”

Born out of a multi-disciplinary theater

project commissioned by Duke University, which acquired the complete

Radio Haiti archives in 2016, Breaking The Thermometer combines original

compositions and traditional Haitian tunes with historical broadcasts

and contemporary interviews to forge an immersive sonic journey through a

half century of racial, social, and political unrest. The music is

captivating, fueled by rich, sophisticated melodic work and intoxicating

Afro-Caribbean rhythms, and the juxtaposition of voices—English and

Kreyòl, personal and political, anecdotal and journalistic—is similarly

entrancing, raising the dead as it shines a light on the enduring spirit

of the Haitian people. McCalla isn’t just some detached observer here,

though; she writes with great insight and introspection, examining her

own journey of growth and self-discovery as she uncovers the Radio Haiti

story and the inextricable ties that bind us all to it.

“Haiti’s

always seen as this far away place,” she says, “but we’re far more

connected as Americans than we realize. Haiti was the first independent

Black nation in the western hemisphere. Its very existence was and

remains a threat to colonial power. At the same time, though, it

symbolizes a lot about injustice and oppression around the world. When

we talk about ‘Black Lives Matter,’ Haiti is a huge part of that.”

Born

in New York City to a pair of Haitian emigrants and activists, McCalla

developed an early fascination with the country and its culture thanks

in part to the time she spent visiting her grandmother there as a child.

After moving to Ghana for two years and later graduating from NYU,

McCalla eventually drifted south to New Orleans, where she planned to

make a living playing cello on the streets of the French Quarter.

“At

the time, I didn’t realize how deep the Haitian roots of New Orleans

ran,” she explains, “but I very quickly found myself diving into all the

cultural and historical connections. And then once I picked up the

tenor banjo, I started researching Haitian folks songs, as well, and I

was amazed to discover this incredibly rich banjo tradition, which led

me to travel back to Haiti again in 2013.”

‘We’ve been offered a myopic view of history’: folk singer Leyla McCalla untangles Haiti’s complex roots

The Haitian-American musician, known for Carolina Chocolate Drops and Our Native Daughters, has seen her country harshly disparaged in the US – so she is trying to tell its true story

Leyla McCalla’s memories of Haiti fall somewhere in the hazy space between dream and reality, in the way so many childhood recollections do. She can still hear the goats that would gather outside her grandmother’s house, where she came to visit from New York as a kid, or the drums and the gunshots that would ring out at night, in and out of sync. There were rabbits, lovebirds, roosters and guinea pigs – “a Noah’s ark of Haitian birds and small animals” as McCalla, now 36, puts it, while sitting upstairs at a Nashville coffee shop in late March. Then there was the time her mother was bitten in the breast by an aggressive horse.

“My mother told me later that my grandmother said that horse was a man,” McCalla says, laughing. “Because in Haitian spirituality, nothing is as it seems. My mother asked her, ‘Why would you think that horse was a man?’ And my grandmother said, ‘Why else would it bite you in the breast?’”

It was one in a series of moments that helped the virtuosic multi-instrumentalist, singer and member of roots supergroup Our Native Daughters understand Haiti – its rich spirituality and traditions, its beauty, and the ugliness in its inequities and bloodshed. McCalla, who was born in New York to Haitian emigres, came home that summer, 10 years old, and told her mother that she identified as Haitian above all. Like many of her recollections, it was a conversation she didn’t remember until her mother reminded her of it. A recording of their recent talk, along with the sounds of roosters, birds, rolling Caribbean waves and lush, complex instrumentation make up her beautiful new album Breaking the Thermometer. It was originally based around a stage production of the same name and evokes a misunderstood place through plucked cello, immersive compositions, lyrics that dance between English and Kreyòl, and animal calls that McCalla found online.

Breaking the Thermometer is based in part on McCalla’s own experiences in Haiti, but the bulk of the storytelling is centred on her journey into the archives of Radio Haiti, the first station to report news in Kreyòl and a cornerstone of the nation’s democratic fight in the 1960s against the oppressive Duvalier regime, an authoritarian state thought to have killed tens of thousands of people in an attempt to maintain power. Using new interviews and archival materials from Radio Haiti, Breaking the Thermometer tells a story about freedom of the press, the undying fight for truth and how citizens – armed with just a pen or a microphone – can help work towards democracy, a story that resonates through the Trump administration to the war in Ukraine.

It also draws attention to a place that is often deeply misunderstood. “Haiti has been so disparaged and so ostracised culturally and socially and politically,” she says. “Its sovereignty has always been in question since its inception. So how do you undo that while also acknowledging the painful, ugly things that have been perpetuated? You look at a place like Haiti, or even Russia or Ukraine [as if they are] so far away from us. We have no nuanced sense of place.”

The record interweaves McCalla’s memories with the collective memory and history of Haiti as told through Radio Haiti, including stories pulled from original broadcasts. She spent hours in the station’s archives at Duke University in North Carolina, and became close with Michèle Montas, widow of the station’s owner, Jean Dominique, who was murdered on his way to work. His killers were never found (attempts were also made on Montas’ life, one killing her bodyguard). Their relationship adds another layer to Breaking the Thermometer. “A big part of their connection and their love for each other was their love for journalism and their vision for what this could do to transform their country,” McCalla says. “It’s a really hard thing to have faith in, but that faith held them together.” She laughs. “I want that!”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it’s an album that also has roots in the Trump presidency: Breaking the Thermometer was influenced by McCalla’s observations of how his policies were affecting Americans, particularly Black Americans and immigrants – but also how they were not without historical precedent.

“Freedom of the press, issues of censorship, crackdowns on protests, all of these things were factoring really strongly into my thinking about how to frame this story,” says McCalla, who is based in New Orleans. “And there was a lot of outcry about the detention of children and families, but no one talks about how we’ve been doing that since the 80s. Or how the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], the same organisation that is telling us how to navigate the pandemic, told us that Aids was caused by haemophilia, heroin, homosexuals and Haitians. Maybe it’s just been shock and awe for so long that we just forget, but it brings a lot up for me in terms of: how much has actually changed?”

Amplifying the unheard is a cornerstone of McCalla’s work, and a resonant theme given the context of our meeting. McCalla is in Nashville for a production of her 2014 album Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes at the National Museum of African American Music. The city represents an industry built from whitewashing roots music and marginalising Black creators: a state of affairs that many in the genre fight dearly to preserve, while others, such as McCalla, are attempting to stage radical interventions. “I was listening to commercial country music travelling through Tennessee,” says McCalla of her journey to the city today. “And it was so much Auto-Tune and twangs and so many stereotypes. I thought, I don’t relate to this. And I think so many people don’t.”

From a young age, McCalla knew she would make work to fill that void. As a Black female cello player in a youth orchestra, she was “marginalised and tokenised” all at once. It didn’t deter her, and she went on to study music at New York University. Soon after, she moved to New Orleans and joined seminal Black string band the Carolina Chocolate Drops. She and fellow Chocolate Drops member Rhiannon Giddens later formed another collective, Our Native Daughters, which centres on the Black origins of folk and string band music, and highlights the banjo’s origins in Africa (Amythyst Kiah and Allison Russell complete the quartet).

“It’s been extremely uplifting to be a part of that kind of collective,” McCalla says. “To validate and lift each other up has been a huge thing. I started touring with Rhiannon when I was really green and hadn’t released any albums, and I feel like it gave me the chance to do what I am doing now. Being in the Chocolate Drops legitimised my sense of what I already wanted to do and how I could work in the world: to be able to traverse the music industry and still make work that is super meaningful.”

Although Breaking the Thermometer tells stories of Fort Dimanche, where political prisoners were tortured and killed, as well as journalists who were assassinated or persecuted in their fight to bring truth to the Haitian people, it is full of hope: “Let the light shine in, let a new day begin,” she sings on You Don’t Know Me, an adaptation of a song by Brazilian composer Caetano Veloso. “I’ve never been someone who’s like, ‘Music is gonna change the world,’” McCalla says. “It’s not just single-handedly music. But [music reflects] the way that people think, the things that people are attached to, the passion that people have for wanting to see positive change.”

Breaking the Thermometer is a true culmination of this vision – and it’s also nowhere near the end. Like the reporters she sings about, McCalla will keep asking questions. “We’ve been offered a very myopic view of history,” she says. “And I think we have a long way to go. But it is changing, and I’m curious what it will be like when we are grandmas.” She laughs again, as she often does when the tension needs to break – as if she’s composing a piece of music in real time. “My goal,” she adds, “is to be an old person one day.”

On a Gorgeous New Album, Leyla McCalla Weaves Haiti’s History With Her Own

Leyla McCalla couldn’t have known that, weeks after releasing her fourth solo album, Breaking the Thermometer, the New York Times would publish a major report detailing the long history of Haiti’s mistreatment at the hands of France and the United States. But McCalla, the Haitian American daughter of Haitian-born human rights activists and the granddaughter of a radical journalist, was already well aware of Haiti’s troubled past and present. The subject lies at the heart of this album, which grew from a multimedia theatrical project based on Duke University’s Radio Haiti archives.

Radio Haiti was the first Haitian outlet to broadcast news in Kreyòl, the country’s main native language, while challenging government corruption and brutality; the Duke project’s title, Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever, came from a phrase Radio Haiti founder Jean Dominique used to characterize that government’s violent repression of its citizens. Dominique was assassinated in 2000, 10 years before McCalla, a cellist who earned a music degree at New York University, moved to New Orleans to become a “trad jazz” busker. As she learned more about New Orleans and Haitian history, she discovered banjo had played a prominent role in Haitian music. In time, she was recruited to join the Carolina Chocolate Drops — which eventually led to Our Native Daughters, the banjo-playing collective that Rhiannon Giddens formed with McCalla, Amythyst Kiah and Allison Russell. Both groups have focused on reclaiming Black musical history and shining light on Black experiences.

On Breaking the Thermometer, McCalla delves into the Haitian aspect of Black history, weaving spoken memories and snippets of Radio Haiti broadcasts into a gorgeous musical narrative. Through lyrics sung in both English and Kreyòl, she examines Haiti’s political turmoil, rich culture and deep spirituality, while exploring her own identity and relationship to this complex land.

BGS: How did the commission for the project that led to this album come about?

McCalla: I was at a place that I really wanted to be doing something that would be life-changing; that would change the way I saw things and be creatively challenging and fulfilling. So when Duke University asked me if I wanted to be involved in creating a multimedia performance based on the Radio Haiti archives, I said yes. We ended up creating a piece called “Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever” that incorporates video projection, sound design, music and dance. That was definitely way more mediums than I’d ever worked with or coordinated before. It became really clear right away that I would need to have other collaborators, so I hired Kiyoko McCrae to direct. We did a lot of workshopping and brainstorming and creative writing, trying to get to the source of what this was about. It took a few years of working on the project to realize that I even wanted it to be an album.

I found out later that my father had helped Duke University get in touch with Michèle Montas [Dominique’s partner], the journalist who was hugely a part of the making of this record, to help facilitate the transfer of the archive from Haiti to Duke — and that Duke also acquired the archives of the National Coalition for Haitian Rights, which my father ran. In that archive, there’s a picture of me at a protest with my mom. I think I met Michèle Montas when I was 15, at a screening of The Agronomist, the film about Jean Dominique, who is credited with elevating journalism in Haiti. A lot of serendipity and personal connections have been revealed over time.

I take it your parents are very prominent in the Haitian American community.

I can’t go anywhere without someone knowing my parents [laughs], especially Haitian spaces. And everyone is very excited that I’m talking about Haiti, because there’s a lot to talk about; a lot to discover. There’s so much misinformation — or no information — about Haiti.

One of the things that I’ve been grappling with in creating this piece, and why I inserted my own personal story into this — which was not my idea, by the way; it was Kiyoko McCrae, the director, who [noticed] I was getting a lot of memories coming up [while] listening to these recordings and trying to really understand the culture, because I’m [part of] a diaspora, I’m not Haitian — not just Haitian. My identity has a big duality in it, with my Americanism. That became a big point of conversation in all of our brainstorming, and Kiyoko said, “I feel like we’re going to be able to reach people at the emotional level, at the heart level, If you share your perspective.” So that became a storytelling device.

I started to put the timeline of my own life against the timeline that we’re looking at with Haitian history and Radio Haiti, and seeing all these intersections and filling a lot of gaps in my knowledge. Part of the challenge for me in creating this work is that I grew up in a Haitian family that didn’t speak in Kreyòl to me. … We decided to confront that disconnect head on by inserting my story into the narratives.

Americans have this perception of Haiti as a very poor country with terrible dictators, which may be true, but it’s probably very reductionist. What are we missing?

I think we’re missing historical context and significance of Haiti, which is something that is just now starting to be talked about more. Haiti was the first independent Black nation in the Western Hemisphere, and was founded on the abolition of slavery, on the abolition of an economic system that kept Black people in the so-called New World impoverished. Haiti being born out of this struggle to create an identity that was not about being a slave, that was about surviving slavery, is something that is hugely underestimated as a threat to Western power structures.

I think you just nailed something there. That leads to exactly what’s going on in the U.S.

Absolutely. If people understood more about Haitian history and that Haiti’s sovereignty has always been something that it has paid for, in one way or another — that there’s been a lot of meddling in Haitian politics by the French government, by the U.S. government in particular — maybe Haiti wouldn’t seem so far away then.

And yet we love New Orleans because it incorporates and celebrates that culture.

New Orleans wouldn’t be what it is without the Haitian revolution, which started in 1791. There were masses of immigrants from the island of Saint-Domingue — it wasn’t Haiti yet — and masses of émigrés who came trying to resettle their sugar plantations in France, which was Louisiana.

With Haiti, it’s all political, and it’s all about slavery, about these people whose plantations were slashed and burned. The slaves just burned down all the plantations. People were fleeing the revolution and trying to stabilize their wealth. It was French colonists who considered themselves Saint Dominicans, because they had been there for generations. They’re essentially Haitian, but a lot of them were slave owning, and some of them were free people of color. So you see how that moved to New Orleans and Louisiana.

The economy in the United States flourished, but it was obviously based on this barbaric system, where the justification was that Black people are not human, so they can’t have the same rights and privileges that [whites] have. We are still contending with these issues. Haiti needs to be talked about way more, because Haiti is part of really dissecting how the transatlantic slave trade created the economic systems that we’re still living in. … This isn’t just a pure defense of Haiti. It’s aiming for a more nuanced understanding of history, and our relationship to history on a global level.

Most of this album uses the language of the original broadcasts. Were you worried about making it understandable for people?

Well, honestly, a lot of my work has been trying to understand it better for myself. I realized, in the course of the album releasing, “Oh my God, no one knows about this. It just isn’t part of the conversation that we are having.” Ultimately, I want an album that is fun to listen to. I’m passionate about music, but there is an educational component to what I’m doing, because there’s been so much miseducation.

The Caribbean rhythms and texture that you incorporated are so lovely to listen to. Even though you might be telling us about an assassination, it’s done in a way that you can listen to just for the music, or you can listen to the conversations and extrapolate from that.

I developed this music with a man named Damas Louis. He is a Hougan, which is like a wizard of religion, a spiritual leader. He helped me develop the spiritual foundation for the music. A lot of the songs are based in Vodou rhythms. Vodou is another thing that has been so disparaged — especially in the American imagination — dating back to like, the ‘20s in Hollywood, with depictions of zombies. Even in the ‘80s, during the AIDS epidemic, the CDC said that there were the four H’s for contracting AIDS: hemophiliacs, heroin addicts, homosexuals and Haitians. So there’s been a lot of negative stereotypes about Haitians, and their — our — spiritual foundation, which is the Vodou religion. I’m not a religious person, but it felt like such a natural fit to be part of the music. It also felt like it served as a subversive kind of tool for understanding this history.

Are there any specifics songs that you would like to discuss?

Hmm. They all tell different parts that all feel essential to the story that I constructed, but I am glad that you said the music is enjoyable, because it is deeply spiritual and I sometimes felt like, should I even be putting this out there in this way? Do I have the authority to be playing Vodou music?

It’s not like it’s cultural appropriation.

I don’t think so, either. I just have a sensitivity about how Haiti is spoken of and represented. I’ve done a lot of work on myself to just be able to say, “Hey, this is where I’m coming from. And this is the only place I could possibly be coming from, because this is where I am. And this is who I am. This has been my experience.” All of the songs ultimately come from that place.

In “Memory Song,” I just love that line, How much does a memory weigh? What’s the price our bodies will pay? What was the inspiration for that song?

I was feeling the responsibility of representing Haiti well and fulfilling my mission with this work. And then feeling like I wasn’t sure that I had enough to offer, but also feeling like “You are the chosen one; you have been chosen to create this incredible work.” And I’m like, “Oh, God, what if it’s not that incredible?”

But literally, you were chosen!

It makes me laugh to think about now because obviously I take it very seriously, and I was grappling with a lot of my memories of Haiti and trying to figure out how those could be part of this conversation about Radio Haiti. I was just thinking how our memories are so much a part of our existence in our minds and our experience, even with things we can’t [recall]. What is the effect of that on us, physically and spiritually, emotionally?

The lyrics in “Artibonite” really caught me. It’s such a spiritual call and response. Is there some history with that?

That’s a song I found on the archive, originally written by Sanba Zao, who is part of the musical collective Lakou Mizik. Samba in Kreyòl means poet. He’s a deeply spiritual guy, and he was singing in a language — I actually sent the Mp3 to my dad to try to get a translation, but my even my dad didn’t understand what he was saying. I suspect he was singing in ngas, a language with very voodooist lyricism and these old words from Africa; it’s hard to know exactly where they come from. But I love the melody so much. And there was this call and response with these women singers and the melody he was singing, so I decided to write new words to that song because it was honoring the assassination of Jean Dominique, the significance of that, and I thought that was so beautiful.

It stood out not just because it was in English, but because you could feel the spirituality, and it does take you back to how slaves communicated in the fields. And it’s just such a lovely melody. But I loved the determination in your lyrics, too.

He lives in the fields

He lives in the flowers

Hold on to your strength

Hold on to your power.

I was thinking about Jean Dominique’s life; how he was originally an agronomist in the Artibonite region of Haiti, which comprises most of Haiti’s exports. It’s a super beautiful place, and he really had a close relationship with some of the farmers who were trying to unionize in that region, so I kept with that theme. There’s also a proverb in Haiti that says, “Beyond mountains, more mountains,” which is fitting because ayiti is a Taino word that means mountainous land. There’s a bunch of Haitian proverbs that I always try to incorporate into my songwriting; that’s why I was thinking, beyond mountains there are mountains yet to cross, thinking about the cyclical nature of — I mean, this tragedy and all the repression, and how we’re still fighting in these cycles. And once we get over the next mountain, there’s gonna be another mountain, and how much that is just a part of the human experience and a part of life.

Photo Credit: Noe Cugny

https://liveartsmiami.org/events/leyla-mccalla/

Leyla McCalla

Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever

Leyla McCalla finds inspiration from her past and present, whether it is her Haitian heritage or her adopted home of New Orleans, she — a bilingual multi-instrumentalist, and alumna of Grammy award-winning African-American string band, the Carolina Chocolate Drops — has risen to produce a distinctive sound that reflects the union of her roots and experience. This Haitian Heritage Month, join Live Arts Miami to experience McCalla’s latest project, Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever, a new multidisciplinary performance work exploring themes of exile, return, and the complexities of what it means to be Haitian.

Breaking the Thermometer is inspired by the legacy of Radio Haiti-Inter, Haiti’s first independent radio station to broadcast news in Haitian Creole—the voice of the people—until the assassination of the station’s founder, Jean Dominque. The title is derived from a proverb used by Dominique to describe the spirit of Haiti’s marginalized poor in the face of violence and political oppression. Directed by renowned theater director Kiyoko McCrae, the work weaves together arrangements of Haitian songs, traditional dances, audio and video recordings from Duke’s Radio Haiti Archive, and Leyla’s own personal storytelling. Through this juxtaposition of voices — the personal and political, the anecdotal and the journalistic — McCalla gives expression to the enduring spirit of Haiti’s people

Leyla McCalla is also set to release her new album, entitled Breaking The Thermometer, featuring music from this project in conjunction with her Miami performance on May 6. The album features sophisticated melodies and Afro-Caribbean rhythms with lyrics in English and Haitian Creole.

“Her voice is disarmingly natural…her magnificently transparent music holds tidings of family, memory, solitude and the inexorability of time: weighty thoughts handled with the lightest touch imaginable.” —The New York Times

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Leyla McCalla is a New York-born Haitian-American living in New Orleans, who sings in French, Haitian Creole, and English, and plays cello, tenor banjo, and guitar. Deeply influenced by traditional Creole, Cajun, and Haitian music, as well as by American jazz and folk, her music is at once earthy, elegant, soulful, and witty — it vibrates with three centuries of history, yet also feels strikingly fresh, distinctive, and contemporary. By 2014, McCalla had already risen to fame as a member of the GRAMMY Award-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops, a group she’d spent two years touring and recording with before leaving to pursue her own career. McCalla’s debut album, Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes, was named 2013’s Album of the Year by the London Sunday Times and Songlines magazine. It was followed by the critically acclaimed 2016 album A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, an extended exploration of the themes of social justice and pan-African consciousness that marked her debut. In January 2019, McCalla released Capitalist Blues, her first full-band album, which examines, through McCalla’s eyes, the divided sociopolitical climate in the United States. Her latest album, Breaking the Thermometer – inspired by the theatrical piece of the same name, is being released on May 6, 2022.

Genres of One

Exploring a host of artists who carve out musical categories of their own.

IV: Leyla McCalla: Classically Trained Creolo

Leyla McCalla. Photo by Tim Duffy

Sitting on the street in New Orleans, playing Bach’s Cello Suites by memory, Leyla McCalla assumed the man taking her photograph was just another tourist. She was a young street musician, after all, situated at the corner of Royal and Conti streets in the French Quarter, between the fabled Café Beignet and a police station. And his family was with him. But when the man finally spoke to McCalla, she understood that he’d been looking for her—actually, he’d been sent to find her.

“He said, ‘You have a sister named Sabine McCalla who goes to Warren Wilson College and lives in Asheville, North Carolina,’” she remembers. “Who is this?”

The man with the camera was Tim Duffy, the manager of the pioneering African-American string band the Carolina Chocolate Drops and the founder of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, a nonprofit that locates and advocates for the country’s aging folk and blues musicians. At a Chocolate Drops show in Asheville, Duffy had met Sabine—a young, black fiddle student interested in string-band music. She piqued his interest as part of the narrative the Drops had been telling tirelessly for years, of how American folk music was a multi-racial form, not simply one of white provenance. She pointed him instead to her older sister, a classically trained cellist subsisting in New Orleans by playing Bach, folk songs and some tunes based around the poems of Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. That’s who the Drops should meet, she said.

Duffy agreed. After that initial encounter in the French Quarter, they gathered later for drinks. McCalla gave him the four-song CD she’d made back in New York and told him of her plans to create a larger project from Hughes’ words. A few weeks later, he wrote to say that he wanted to manage her. He even asked her to come play on Leaving Eden, the follow-up to the Drops’ Grammy-winning major label debut. These ideas she’d had suddenly had new momentum.

“It gave me a focus about my work that I didn’t have. Before, it was, ‘Wake up. Get on your bicycle with your cello. Set up your little spot. Play,’” she says. “But he said this is great music. You should create what you’ve been wanting to create.”

That conversation occurred in 2010, not long after McCalla had permanently relocated to New Orleans from her native New York. And at last, she’s done what Duffy suggested then, to finish her own project and start her career. McCalla’s debut—the stunning 13-song set Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes—sets Hughes’ poems, traditional Haitian numbers sung in Creole and a handful of yearning originals to the pizzicato warmth of McCalla’s cello. Her playing—on cello, tenor banjo and guitar—suggests a perpetual spring, giving these songs about losing innocence and finding death a vibrancy that fits their folk music function. Her voice is a velvety purr that’s both wise and bright, not unlike the surreal sophistication of Jolie Holland’s best work.

“I never saw the cello as, ‘This is what’s going to make me different.’ I know that’s a big part of what has shaped my ear and how I hear things,” she says. “But I’m focused more on expressing these songs than my cello technique, because there’s so much I can do on cello that I never do on stage. The songs that I play and the stories I tell are what makes me different. I think of myself as an artist first. These are my tools.”

Photo by Tim Duffy

At 28, McCalla’s life and musical education have been defined by a steadily outward expansion of her interests and approaches. She began playing cello in elementary school after a teacher handed her one as an assignment. She steadily grew her repertoire and honed her skills as a young classical musician. At home, her parents, both Haitian immigrants who’d arrived in America as children, mostly played the sounds of cultural assimilation—Stevie Wonder and Bob Marley, Paul Simon and James Taylor. They kept in touch with the sound of Haiti’s modern compas music, but the island nation’s traditional songs did not soundtrack McCalla’s childhood.

Instead, she found the trail of folk music through a friend’s mother, who sang old-time American songs and played guitar. When she was 13, McCalla began teaching herself to pick six strings instead of four, playing the songs she learned from the mentor, plus the Radiohead and Smashing Pumpkins numbers she loved on the radio. Those very casual studies shaped a strange parallel to her more academic musicianship.

Though she eventually studied cello at New York University, she began to understand that the cloistered world of classical music might not be in her future. After all, she’d mostly put the instrument down after her family moved to Ghana for two years. (“There was no one to study with there and it put my conservatory hopes on hold,” she told The Guardian last year.) Back in New York, when she was 18, McCalla met the cellist Rufus Cappadocia, who dominated a five-string cello in a Haitian roots music band. He plucked and strummed and plundered the groove in a way that she didn’t know was possible. He became her teacher, and the possibilities of the instrument she’d played since fourth grade suddenly exploded. She worked as a cocktail waitress at the Williamsburg venue and restaurant Zebulon, too, an experience that further stretched her understanding of what music might become.

“I had my eye outside of that classical scene,” she says. “I don’t want to live my life with these people. I don’t even like being around them in school. I didn’t care enough about classical music to suffer for it. I have a completely different relationship with my own music now.”

That relationship stems in large part from the two years she spent touring with the Carolina Chocolate Drops after Duffy found her in New Orleans. That stint gave her surprising insights not only into the songs they played but into the strange social dynamics that playing them created.

“It was such a unique experience to be part of a folk band that was all black, even as a black person. It’s not like we all think the same thing about everything,” she says, laughing. “I don’t think white folk bands had the conversations that we had. And that’s the essence of the Carolina Chocolate Drops: They start conversations that a lot of other bands don’t go near. ”

However auspicious Vari-Colored Songs might be, it seems only like the beginning of its own conversation, a prelude for McCalla rather than an endpoint. She already seems to have pushed past its even acoustic keel and generally pleasant atmosphere, moved as she is these days by more lively Creole and Cajun tunes. And though she largely plucks the cello’s strings on Vari-Colored Songs, she’s working on new songs that incorporate more bowing and, overall, more ideas to stretch her set. And the cultural continuum between Haiti and Louisiana is something she hopes to share through her music. She wants to redefine the attitudes people have about the influence of the benighted country.

A cellist who sings Langston Hughes poems might seem plenty different to many. McCalla insists, however, that this is only her initial step.

“I feel like I have a few techniques that you might not have seen,” she says, “but I feel like there’s so much more I could be doing.” —Grayson Currin

https://www.breakingthethermometer.com/

Breaking the Thermometer

to Hide the Fever

World Premiere March 4-6 Duke University Durham, NC

Directed by Kiyoko McCrae, Breaking the Thermometer combines storytelling, dance, video projection, and audio recordings from the Radio Haiti Archive housed at Duke University and is anchored by McCalla’s original compositions and arrangements of traditional Haitian songs. We see Haiti through Leyla’s eyes as she grapples with the harsh political realities of its people and the journalists, like Dominique, who fought to uplift their voices.

Duke Performances is lead commissioner of Breaking the Thermometer. The project will premiere in Durham, NC in March 2020 and is currently seeking commissioning and presenting partners. The work is available for touring nationally and internationally in Spring 2020 and beyond.

The Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans is hosting a series of production residencies for the project from 2018 to 2020.

Header photo by Rush Jagoe.

https://folkways.si.edu/leyla-mccalla/vari-colored-songs-a-tribute-to-langston-hughes

Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes

by Leyla McCalla

Leyla McCalla’s Vari-Colored Songs is a celebration of the complexity of Black culture and identity, and a tribute to the legacy of poet and thinker Langston Hughes. A songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, McCalla sets Hughes’ poems to her own spare yet profound compositions. She juxtaposes these with arrangements of folk songs from Haiti, the first independent Black nation and the homeland of her parents, tapping into the nuances of Black experience. McCalla’s music elegantly weaves Haitian influences together with American folk music, just as Hughes incorporated Black vernacular into his remarkable poetry, and the way the Haitian Kreyòl is a beacon for the survival of African identity through the brutal legacy of colonialism. This is music of reclamation, imbued with a quiet power that grapples with the immense weight of history.

Vari-Colored Songs had a limited release in 2013, with the New York Times proclaiming that “[McCalla’s] magnificently transparent music holds tidings of family, memory, solitude and the inexorability of time: weighty thoughts handled with the lightest touch imaginable.” The recording is being brought to a wider audience by Smithsonian Folkways at a time when the history McCalla explores is more relevant than ever. As she states in the album’s liner notes, “The wisdom and truth that Langston Hughes continues to provide us through his prolific output inspires us to celebrate the assumedly mundane and stigmatized parts of our society. The future has always been uncertain, and it has always been up to us to push for the changes that we want to see in the world.”

Track Listing

|

Audio Player

101

|

Heart of Gold | Leyla McCalla | 02:59 |

|

Audio Player

102

|

When I Can See the Valley | Leyla McCalla | 02:10 |

|

Audio Player

103

|

Mèsi Bondye | Leyla McCalla | 02:26 |

|

Audio Player

104

|

Girl | Leyla McCalla | 02:51 |

|

Audio Player

105

|

Kamèn sa w fè? | Leyla McCalla | 02:21 |

|

Audio Player

106

|

Too Blue | Leyla McCalla | 02:28 |

|

Audio Player

107

|

Manman Mwen | Leyla McCalla | 03:19 |

|

Audio Player

108

|

Song for a Dark Girl | Leyla McCalla | 02:49 |

|

Audio Player

109

|

As I Grew Older / Dreamer | Leyla McCalla | 03:50 |

|

Audio Player

110

|

Love Again Blues | Leyla McCalla | 02:39 |

|

Audio Player

111

|

Rose Marie | Leyla McCalla | 02:58 |

|

Audio Player

112

|

Latibonit | Leyla McCalla | 03:49 |

|

Audio Player

113

|

Search | Leyla McCalla | 03:20 |

|

Audio Player

114

|

Lonely House | Leyla McCalla | 03:27 |

|

Audio Player

115

|

Changing Tide | Leyla McCalla | 03:03 |