SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER THREE

MARC CARY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

REVOLUTIONARY ENSEMBLE

(June 11-17)

OLU DARA

(June 18-24)

WALTER SMITH III

(June 25-July 1)

BOBBY WATSON

(July 2-8)

JAMES MOODY

(July 9-15)

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

(July 16-22)

LEYLA McCALLA

(July 23-29)

RUSSELL MALONE

(July 30-August 5)

JOHN HANDY

(August 6-12)

GREG LEWIS

(August 13-19)

STANLEY CLARKE

(August 20-26)

JASON HAINSWORTH

(August 27-September 2)

John Handy

John Handy - saxophone, vocals

John Handy is an alto saxophonist who plays the tenor, saxello, baritone, clarinet, oboe and vocals. He is actually a consummate world musician and teacher who devoted his life to using music to elevate the human spirit. His soulful and fiery saxophone style is instantly recognizable to generations of jazz fans world-wide.

As a performer and composer he continues to sweep audiences into ecstasy with his vast range of creative, emotional, and technical inventiveness. With a superb knowledge and practical experience with music of several cultures, he fuses, with each selection, a musical genre that is coherent, provocative, logical, and enjoyable.

Known most readily as a saxophonist in jazz quartet and quintet settings, John Handy is also featured in solo, duets, and large ensembles ranging in size from big bands to concert bands, symphony orchestras, vocal groups, and choirs.

As a singer, he brings a kind of storytelling narrative to the blues that is entertaining, educational, and moving; while his "up tempo" scat vocals could be compared to the best scat singers anywhere. He sings ballads with inventiveness that is rare among singers.

John Handy has performed in the world’s great concert halls including Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Berlin Philharmonic Auditorium, San Francisco Opera House, Davies Hall; the major performance venues including Tanglewood, Saratoga (NY), and Wolf Trap; and the pre-eminent jazz festivals including the Monterey Jazz Festival, Newport Jazz Festival, Playboy Jazz Festival, Chicago Jazz Festival, Pacific Coast Jazz Festival; and international jazz festivals at Montreaux (Switzerland), Antibe (France), Berlin, (Germany) Cannes, (France) Yubari and Miyasaki (Japan) among others.

His album and CD covers read like a who’s who of record labels - Columbia, ABC Impulse, Warner Brothers, Milestone, Roulette, Boulevard, Quartet (Harbor), MPS Records and many others. His most recent recordings are "John Handy Live at Yoshi’s" and "John Handy’s Musical Dreamland" (available only on Boulevard Records, Stuttgart, Germany) "Centerpiece," and "Excursion in Blue." Some of his earlier works have been reissued on CD - "John Handy: Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival," "The Second John Handy Album," "New View," and "Projections." He recorded with Sonny Stitt, and recorded nine albums with Charles Mingus Jazz Workshop.

John Handy has taught at San Francisco State University, Stanford University, UC Berkeley, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, among others. He is a popular performer on university and college campuses where he also gives inspired lecture-demonstrations on the technical, academic, spiritual, and creative aspects of music, winning new converts to jazz.

John Handy has written a number of highly acclaimed, original compositions. "Spanish Lady" and "If Only We Knew" both earned Grammy nominations for performance and composition. The popular jazz/blues/funk vocal crossover hit, "Hard Work," brought him fame in another realm; while "Blues for Louis Jordan" displayed his talents in rhythm and blues. His more extensive works include "Concerto for Jazz Soloist and Orchestra" which was premiered by the San Francisco Symphony; and "Scheme Number One" which was lauded as a fine example of fixed and improvised music by the great composer, Igor Stravinsky.

Although he is well known in the continental United States, John Handy has taken his music to Germany, Austria, Spain, Italy, France, England, Sweden, Luxemburg, Finland, Norway, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, North and South India, Yugoslavia, Japan, Alaska, Canada, among other countries - all with great acclaim!

For the past 23 years, John has led John Handy WITH CLASS, featuring John Handy with three female violinists/vocalists in an unforgettable sound that captures the full range of jazz, blues, r&b, popular, and modal music. This innovative group creates a new musical expression which John refers to (tongue-in-cheek) as "Clazzical Jazz." He continues to lead and perform in groups with a combination of instruments and vocals.John Handy

John Richard Handy III (born February 3, 1933)[1] is an American jazz musician most commonly associated with the alto saxophone. He also sings and plays the tenor and baritone saxophone, saxello, clarinet, and oboe.[2]

Biography

Handy was born in Dallas, Texas, United States.[1] He first came to prominence while working for Charles Mingus in the 1950s.[1] In the 1960s, Handy led several groups, among them a quintet with Michael White, violin, Jerry Hahn, guitar, Don Thompson, bass, and Terry Clarke, drums.[1] This group's performance at the 1965 Monterey Jazz Festival was recorded and released as an album;[1] Handy received Grammy nominations for "Spanish Lady" (jazz performance) and "If Only We Knew" (jazz composition). [3]

After completing high school at McClymonds High School in Oakland, he studied music at San Francisco State College, interrupted by service during the Korean War, graduating in 1958. Following graduation, he moved to New York City. Handy has taught music history and performance at San Francisco State University, Stanford University, the University of California, Berkeley, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.[4]

In the 1980s he worked in the project Bebop & Beyond, which recorded tribute albums to Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. His son, John Richard Handy IV, is a drummer who has played with Handy on occasion.

In 2009, he received the Beacon Award from SF JAZZ.[4]

Discography

As leader

- In the Vernacular (Roulette, 1959)

- No Coast Jazz (Roulette, 1960)

- Jazz (Roulette, 1962)

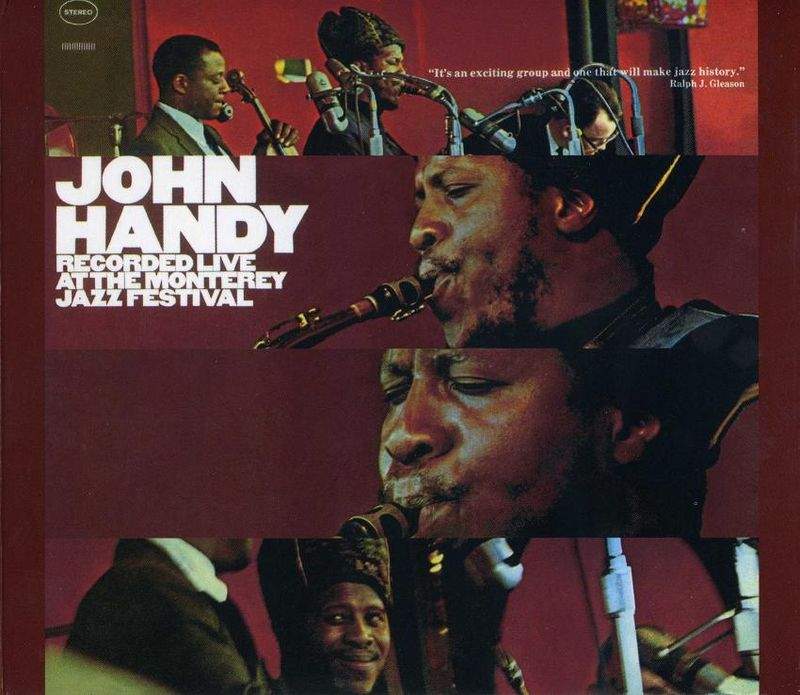

- Recorded Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival (Columbia, 1966)

- The 2nd John Handy Album (Columbia, 1966)

- New View (Columbia, 1967)

- Projections (Columbia, 1968)

- Karuna Supreme (MPS, 1975) with Ali Akbar Khan

- Hard Work (Impulse!, 1976)

- Carnival (Impulse! 1977)

- Where Go the Boats (Warner Bros., 1978)

- Handy Dandy Man (Warner Bros., 1978)

- Rainbow (MPS, 1980) with Ali Akbar Khan and Dr. L. Subramaniam

- Excursion in Blue (Quartet, 1988)

- Centerpiece (Milestone, 1989) with CLASS

- Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival (Koch, 1996)

- Live at Yoshi's Nightspot (Boulevard, 1996)

- John Handy's Musical Dreamland (Boulevard, 1996)

As sideman

With Brass Fever

- Brass Fever (Impulse!, 1975)

- Time Is Running Out (Impulse!, 1976)

With Charles Mingus

- Jazz Portraits: Mingus in Wonderland (United Artists, 1959)

- Mingus Ah Um (Columbia, 1959)

- Mingus Dynasty (Columbia, 1959)

- Blues & Roots (Atlantic, 1960)

- Right Now: Live at the Jazz Workshop (Fantasy, 1964)

With Mingus Dynasty

- Live at the Theatre Boulogne-Billancourt/Paris, Vol. 1 (Soul Note, 1988)

- Live at the Theatre Boulogne-Billancourt/Paris, Vol. 2 (Soul Note, 1988)

External links

- Official website

- John Handy talks about the Fillmore neighborhood and Bop City (1999)

- Jazz Weekly interview with Handy

- Hard Work-John Handy-1976 on YouTube

https://geoffreyslive.com/oaktown-sound/mcclymonds-own-genius-of-the-sax-john-handy/

Home

Oaktown Sound

McClymonds' Own Genius Of The Sax, John Handy

John Handy

Biography

John Handy has

been honored with the Bill Graham Lifetime Achievement Award from the

1997 Bay Area Music Awards!. Having played professionally since he was

fifteen, the saxophonist has worn coats of many cultures throughout his

long, prolific career, changing them as often as a chameleon alters its

hues.

John Handy was born in Dallas and moved to Oakland in 1948. As a teenager, he played around the Bay Area in blues bands led by Roy Hawkins, Pee Wee Crayton, Little Willie Littlefield, Jimmy McCracklin, Wild Willie Moore, and Dell Graham, and jazz artists such as Gerald Wilson, Teddy Edwards, and Frank Morgan. He made his recording debut in 1953 with Lowell Pulson . Although his musical approach changed after he heard Charlie Parker at San Francisco's Say When Club, the influence of such earlier saxophone favorites as Johnny Hodges, Louis Jordan, and Earl Bostic remained strong and contributed greatly to the development of his unique, searing style. Indeed, Handy is one of the few musicians who have come close to rivaling Bostic's awesome command of the instrument's upper registers.

Later, Handy secured a B. A. in Music from San Francisco State University, and has served as a music educator since 1968, teaching history and performance at a number of colleges, universities and special clinics - Stanford University, U.C. Berkeley and San Francisco State University among them.

Handy went on to compose and play classical pieces, performing "Concerto for Jazz Soloist and Orchestra" with the San Francisco Symphony in 1970, and in more recent years he has composed with the UC San Francisco orchestra.

After a stint in the Army, Handy headed for New York in 1958 and was soon hired by bassist Charles Mingus, who found the saxophonist's highly emotive style ideally suited to his alternately sweet and volatile music. Although Handy was a member of Mingus's band for less than a year, the association brought him a contract with Roulette Records. Because his distinctive approach didn't fit into either the prevailing East Coast or West Coast schools of the period, the company labeled Handy's music "No Coast Jazz."

Returning to San Francisco in 1962 to finish college, Handy stayed and has led a succession of groups ever since. The most successful was the one that featured violinist Michael White and Jerry Hahn. They were a sensation at the 1965 Monterey Jazz Festival and recorded several best-selling albums for Columbia. Indeed, Handy's performances of his own "Spanish Lady" and "If Only We Knew", the pinnacle notes of that Monterey Jazz Festival, earned Grammy nominations for both performance and composition.

Amazing John Handy Quintet at Dizzy's Music on Jazz at Lincoln Center

John Handy’s performance at the 1965 Monterey Jazz Festival was an unprecedented sensation. Brave, free, and unique, the set is considered a high point of improvisation and an essential listen amongst aficionados. The entire set is comprised of two lengthy, wholly captivating pieces full of extended solos on saxophone, guitar, violin, bass, and drums. From the opening minutes to the fiery climax, the music transports the listener, instilling a sense of wonder that remains palpable today. Recordings of the original performance have thankfully been reissued, but it will be a special privilege not only to hear this material in person, but to experience it with an audience almost unthinkably intimate compared to the Monterey crowd that gave Handy such thunderous applause 50 years ago:

https://indianapublicmedia.org/nightlights/john-handy-talks-with-night-lights-part-1.php

John Handy Talks With Night Lights:

Part 1

by David Johnson

January 30, 2008

Alto saxophonist John Handy has made monumental jazz records with bassist Charles Mingus, wowed crowds at the Monterey Jazz Festival, delved into world and classical music, had a chart hit with the 1976 single "Hard Work," and helped pave the way for the rise of jazz education. On February 3 he turns 75, and this week on Night Lights we'll be featuring his 1960s Roulette and Columbia recordings (including sidemen such as trumpeter Richard Williams, violinist Michael White, and pianist Don Friedman), in addition to a side that he recorded in 1959 with Mingus. Last week he spoke with me by phone from his home in California, and I'll be posting portions of the interview throughout the week on this website. In today's segment, he talks about early encounters with Dexter Gordon and Art Tatum, why he came to favor the alto over the tenor saxophone, and the legendary young bassist Albert Stinson, who was a member of Handy's late-1960s band.

DBJ: You played clarinet as an adolesecent, but you were also quite a skilled boxer. What made you decide to pursue boxing instead of music for awhile?

JH: The thing that stopped me from playing music and getting into boxing was because I was in a small school. By the time I reached the ninth grade, the seniors and older students had all graduated. They had had a small jazz and concert band, but they were gone and there weren‘t enough people to fill the band anymore. So they started a sports program, with softball, football, basketball and others. I was a good baseball player--physically, I was very well coordinated. Not a very big guy, but… anyway, I started boxing and I was much better than even I probably realized.

DBJ: You won some sort of state championship, right?

JH: Yes, I did. It was an amateur thing…in the tournament we were supposed to fight three times, and I knocked out a kid in 19 seconds. Nobody would box me after that, so I won…(laughs) I didn‘t have to fight the last two fights in the tournament.

DBJ: Who were some of your early music heroes? I read one interview in which you say you saw Charlie Parker with Jay McShann, but you didn‘t realize who it was until years later, because you were so young at the time.

JH: I didn‘t see them, I heard them. Actually, they had just recorded in Dallas in 1941. I lived there, but I was only 8 years old… but we had the recordings, and it was many years later, when I was in my late 20s or early 30s, that I realized that was where they had done those recordings, in my hometown.

DBJ: You‘ve spoken very respectfully of people like McShann and Benny Carter and Sonny Rollins…were there others as well that you really enjoyed listening to?

JH: Scores, yes. I came to know who these people were at a really young age--even some of the local guys, like Buddy Floyd, who later played with Roy Milton. I heard him on the radio in Dallas when I was a very young child. T-Bone Walker was around in those days--as a matter of fact, he played for my mother‘s 12th birthday party. But yeah, you know, the obvious guys who were recording in the 1930s and 1940s… early Louis Armstrong, early Louis Jordan, Lil Green (a singer), Sister Rosetta Tharpe with the Lucky Millinder band, Buddy Johnson‘s band…all this was radio. We used to listen to a program called "The Grand Prize Dance Parade" where they played lots of recordings of big bands and small bands. And there was a little bit of church music, too…we weren‘t avid churchgoers, but I went enough to know what it was about, and a number of different denominations, too--Seventh Day Adventists, for one. By the time I was 11 we started going to St. Peter‘s Academy, where we went to Catholic Church…I was playing by then, and the Gregorian chants and other songs in the Catholic Church were very beautiful to me. And I had that background in gospel music by then as well; that was in my head all the time, along with all the popular music, Nat King Cole, Big Maceo, blues singers, Lonnie Johnson.

DBJ: It sounds like you were exposed to a lot of different music early on.

JH: Yes, and by the time I was 14, I even had the experience of going and hearing the Dallas Symphony Orchestra--once, and very briefly, but it was a very beautiful experience.

DBJ: In the early 1950s you were playing at San Francisco‘s Bop City quite a lot. I read one story about you and Chet Baker trying to sit in with Dexter Gordon. Is that true?

JH: Yes! (Laughs) I was beginning to play quite often, and Chet too, sitting in with more experienced players. We knew each other, but I didn‘t know his name was Chet--I just called him Jim. He was in the Presidio Army Band right here in San Francisco, and I was still in high school here in Oakland. It was in Oakland, where Dexter was playing down on 7th Street, which was the location for most of the African-American clubs, jazz, blues, whatever else was presented. We went and sat in during a Sunday matinee…and we were young guys, we played too long, you know, we didn‘t--(laughs)--we should‘ve stopped, but we didn‘t. So Dexter didn‘t ask us to stop, he just played something we couldn‘t play. (Laughs) I think it was "Dizzy Atmosphere."

DBJ: (Laughs) And I‘ll bet the atmosphere started to feel dizzy!

JH: (Laughs) Years later, in the 1980s, I was talking to Dexter, and he kind of remembered meeting me when I was 18, and I told him what he‘d done to me and Chet, said "I guess you just got kind of tired of us" and he said (imitates Dexter‘s hoarse, stately voice), ‘Oh no, John, I didn‘t do that, did I?" and I said, "Oh, yes, you did!" (Laughs) We just didn‘t--it was his gig, you know?

DBJ: Didn‘t you have an encounter with Art Tatum around that time too?

JH: Yeah. Within the next year and a half I was working at this place…I‘d moved to San Francisco and I was a student at San Francisco State College. Anyway, Art sat in… while I was playing, he sat in and I didn‘t see him sit at the piano. All of a sudden...I was playing a song I didn‘t know very well, "You Go To My Head." Mind you, I was 19…I turned around and I recognized him. I knew he was in town--he made this big grin and I almost fainted, I was so scared. I didn‘t know the song, that‘s what bothered me. I was in the bridge, and I played the last 8 bars and I got down, like anybody else would‘ve. (Laughs) And it turns out I had breakfast with him the next day. I had a class at 7:40 a.m., so when the place closed at 6 a.m., I went into the little restaurant with my books, and the only person sitting in there was Art Tatum. So we sat at the counter together and started talking. And of course I wanted to ask him a lot of questions and I did. Two things I remember him saying: "If you play fast enough nobody‘ll know what you‘re playing anyhow." (Laughs) He asked me if I was taking music--I was actually in the band, but I was taking all academic courses. He told me he had a son who was studying engineering. As I got ready to leave he said, "Young man, if I have any advice to give you-if you‘re gonna be a musician, be the best." And I knew that was left up to guys like him, not me.

DBJ: That‘s really interesting, because I know you said in one interview that you didn‘t go to New York City till 1958 because it took you seven years to prepare. It seems like you had a pretty good sense of yourself as a musician and how you were developing, and that you didn‘t go to New York until you were really-

JH: No, I‘ll tell you, to be honest…and I‘m not being cocky, but I‘ve always believed I could do damned near anything, musically. I was kind of a wiz kid, and thought I could do anything--basically because most people didn‘t think I could. The sports thing, you have to prove your manhood and all this when you‘re at a certain age… The main reason I didn‘t want to go to New York earlier, was because first of all I wanted to go through college, have a university education. And I also saw a lot of the social problems that existed amongst the people with whom I wanted to play, and I decided--I knew how things went out here. I‘d met many of the people who lived in New York and all over the country. I just knew a little age would help, they‘d kind of leave you alone, because there is a hierarchy, at least I adhere to it even now, and there were social problems within the echelons of the jazz hierarchy. And something told me to be better prepared, to have more background and experience, and mainly just be my own man, and people would respect that--and they did.

DBJ: Around the time you went out to New York City, you‘d gone back to playing the alto sax as your primary instrument. What prompted that?

JH: Well, let‘s go back to the tenor. I was an alto player first, and the thing that prompted that was--I borrowed Sonny Simmons‘ tenor a couple times, we went to high school together-

DBJ: You went to high school with Sonny Simmons?!

JH: No, he went to high school with me! (Laughs)

DBJ: Okay. (Laughs)

JH: Six months older, okay? (Laughs) No, he had an instrument--I didn‘t actually own one, but I was borrowing a horn from school, and I found out that he had a tenor, and I borrowed his a couple of times. And musicians encouraged me, some of them liked me better on tenor than alto. So I was drafted in the meantime, and when I came back from Korea my horn (alto) was in such bad shape because of the weather there…and so I didn‘t have an alto for about three years. Then in the spring of 1958 I bought an alto from a guy with whom I was playing, Buddy Howells, who was leading a big band here. He was from Detroit…he had an almost-brand-new alto. So when I went to New York I‘d been playing alto again for about three months. I was still playing more as a tenor player, but I was bringing the alto back. And I always preferred it. But some of the older guys, Milt Jackson, and Miles I‘m told, liked me better as a tenor player. But here‘s a quick story about that--when Trane came out here with Miles in ‘56--I‘d met him before, with Johnny Hodges--so I knew him, we‘d hung out a bit and he came over to my house and met my parents. And we practiced a few times, and I played tenor, right? But we went to a jam session…I‘d jammed with him before, but this time we went to a couple places…and I played my tenor and I saw another friend of mine from high school, Sonny King, who had an alto, and I asked him to let me play his horn, and he did, because I used to borrow his horn in high school… (Laughs) So I played the alto while Trane held my tenor in his lap, and when I came back he said, "That‘s your horn." And I wanted to play the alto anyhow, so it encouraged me to go back to it.

DBJ: Years later you recorded a very nice version of his tune "Naima," right around the summer that he passed away. (On the album New View)

JH: You know, that was a coincidence, that I had recorded that--I recorded that in the latter part of June, when we had a whole month at the Village Gate, when I had Bobby Hutcherson, Pat Martino, Albert Stinson--a very fantastic, legendary, very young bass player--and Doug Sides as the drummer. We had finished the gig and we had recorded that live at the Village Gate. And then John died, and John Hammond, the impresario, dedicated it to John. And I would‘ve, but I actually didn‘t, because he was not actually dead when I recorded it.

DBJ: That‘s what I thought, because I was looking at the CD and it said, "June 28," and Trane died in the middle of July.

JH: That‘s right, I‘m glad you caught that, because most people have never said anything about that. And I was a little miffed because John took the liberties to do things like that, but you know, it wasn‘t bad, and since it happened I certainly wouldn‘t have said, "Don‘t do it, you shouldn‘t have done that."

DBJ: Well, I know you said John Hammond did other things too, like retitling "The Spanish Lady" to "Spanish Lady."

JH: Yes, he took the article off. (Laughs)

DBJ: Well, if I use it on the show, I‘ll playlist it as "THE Spanish Lady."

JH: Okay! (Laughs) Man, I liked John, I wasn‘t--I didn‘t have--he was a lot older, and he had done a lot of things for jazz, and that‘s why I went with that recording company. Because actually I was deciding between that company (Columbia) or Atlantic after I did the (1965) Monterey Jazz Festival. Nesuhi Ertegün came to my apartment after the Festival and tried to convince me to go with them. And I didn‘t--I liked Columbia better.

DBJ: I wanted to ask you quickly, just as an aside--could you tell me a little bit about working with Albert Stinson, because he‘s a musician I really like, and he died far too young.

JH: Much too young. He was in my band for about as long as Bobby Hutcherson…about seven months of 1967. He was very young, 22 when he was in the band. I was very impressed with both he and Bobby, because we had a rehearsal at Bobby‘s house--Albert lived about four doors away. And they were both so young, but they were each married and had a boy and had their own homes… Albert was one of these kids who just had a glorious talent, and he was a person that almost anybody would love. A very easy, sweet young guy, and his playing was just incredible. He seemed to have a bunch of natural ability, which I understood because I came that way myself, without that much experience, but just kind of knew how to do it. However, I was afraid- even with those guys in my band, there were drugs. And I didn‘t--they kept it away from me. They were younger, they kind of--you know, when you‘re the bandleader the little cliques kind of take place, and they weren‘t vicious, they just--I could see the half-generation difference in age and all. But something else, to tell you how great this guy could play… Bobby had left the band, and I got Mike Nock to play piano, so we had a quartet. We played Europe, and we came back here, and Gunther Schuller‘s Visitation opera was being played out here. I‘d done something with him in New York, so he asked me to get a jazz group to augment the orchestra that he had out here in San Francisco. So I brought in my band, Mike Nock and Albert and Doug Sides on drums…and these guys had been classically trained, except for Albert. Albert had never--he told me he had never played with a conductor, he didn‘t… (laughs) Well, man, he learned those parts by just--with one or two rehearsals, and they were very difficult, as you can imagine if you know anything about Gunther Schuller‘s music. And at one point Gunther Schuller stopped the rehearsal and said to the bass players, "Do you hear this bass player? He sounds as big as almost all of those guys put together back there!" And poor Albert was so sick, I didn‘t realize it, from doing crazy things, you know, and vomiting during the breaks because he was taking drugs…I didn‘t know that. He kept it away from me. All I know is he played his butt off. He and the drummer went back to L.A. after we finished the opera; for two weeks we were supposed to have gotten together, but we never did, and of course they never came back. And two years later he went with Gabor Szabo and that‘s where he died of an overdose, in a hotel in Boston…and I‘m really sad to say it, but I think also to tell some of the younger guys, to not be as--to be aware.

DBJ: Yeah, you know, you seemed to avoid that, and you came up in an era when that was really, you know-

JH: "Seemed to?" No, I totally--I--I didn‘t do it. I didn‘t get into that. It was crazy, it‘s stupid, and I think some of our problems with youth now had a lot to do with some of the older guys who started doing drugs, and people on the peripheries were inspired by us… you know, some of us were heroes. And they just wanted to be on the scene and they became part of the scene…and while many of us were never doing this, others were, and unfortunately… we‘ve lost a lot of wonderful people, and we‘ve helped tarnish generations to come with that--with drugs. It‘s bad, and I know I‘m sticking my neck out to say it, but in my heart of hearts, you know, I‘ve been around long enough and I‘ve kept my eyes open and I can see where a lot of this stuff came from.

(To be continued. In part 2 John Handy talks about his unusual method of tonguing, how he came to play with Charles Mingus, and the origins of "Goodbye Porkpie Hat")

https://indianapublicmedia.org/nightlights/john-handy-talks-with-night-lights-part-2.php

John Handy Talks With Night Lights:

Part 2

by David Johnson

January 31, 2008

In Part 2 of our interview with alto saxophonist John Handy, he discusses a unique aspect of his sound, the origins of Charles Mingus' Lester Young tribute "Goodbye Porkpie Hat," the night Mingus made a scene listening to him play, the Mingus gig that resulted in the live album Jazz Portraits, and the frustrations he faced recording his first album for Roulette. This week's Night Lights show, Handy On The Horn, will feature the saxophonist's recordings for Roulette and Columbia, made between 1959 and 1967.

JH: Charles McPherson‘s maybe my favorite alto player, I think--I know he is. I‘ve got to tell you a quick story about him, when I first heard him at Birdland. He was sitting in on one of those Monday-night things, I believe, when the name groups took off and the sidemen played. Well he was playing beautifully; I didn‘t know who he was, had never heard of him, and he played very much like Charlie Parker. Much more than--he‘s obviously been his own person for many years now. Anyhow, I was really excited about this young guy playing, and John Coltrane was standing near me at one point, and I said, "Trane, listen to this guy, isn‘t he great?" And I was very disappointed to hear him say, "Well, he plays too much like Charlie Parker." Well, it blew my mind, because Charles was only in his very early 20s, maybe 21, 23, somewhere in there… well, at one time Trane had played like everybody else, you know! Sonny Stitt, Charlie Parker… (laughs) before he became who he was. So I was a little disappointed to hear him say that…Charles McPherson is a great player, but then so was John! (Laughs)

DBJ: Talking about some of the things that have made up such a part of your individual sound, when and kind of how did you develop this unique form of tonguing you have? I know you said in one interview that it‘s not "double-tonguing"…

JH: It‘s really like a tremolo. Rahsaan (Roland Kirk) was another person who could do it. It‘s something you can either do it right away, or you can never do it. It‘s-physically you‘re kind of able to take the tip of the tongue and you do it, kind of on the reed as you would a stringed instrument, with a bow and a violin. And that‘s how you--normally I would never say this (laughs), but most people can‘t do it. Somebody wrote this part of the beginning of my solo on "Goodbye Porkpie Hat" that I recorded with Charles Mingus, and I did that with him for part of a chorus…and Charles could do the tremolo on his bass with his fingers. And if you heard that, we use that technique on my solo at one point. And this guy, Sy Johnson, he wrote an arrangement on that, and he used part of my solo--well, the saxophone players can‘t do it! (Laughs) It‘s not a putdown… I can‘t tongue regularly as fast as some people, but I can do that.

DBJ: I wanted to ask you about "Goodbye Porkpie Hat." How did that composition and recording come about?

JH: Oh, it‘s very interesting. We were working at the Half Note, and we were on the bandstand when we got the news that Lester Young had died. Well, you know, it was very sad news, and Mingus started to play a very slow, mournful blues in C minor…very slow…and he had me play first, and he just kept goading me to play longer and longer, and so I played a long time on it before anybody else did, so… I believe we took a break and, you know, we were just saddened and walked off for quite awhile. And we were recording within a day or two, and he came up with that melody…and I think we actually had it on the bandstand, and it was in a totally different key. It was in E flat minor. And he had written these very complicated changes that were nothing like most blues (laughs) or any kind of tune that anybody had ever played. It was totally unique to that particular composition. And since he never gave us the chords to anything, it didn‘t really matter, because you had to, kind of had to go for yourself no matter what. What he had written, if you didn‘t hear it, you didn‘t get it right, it was recorded that way, if it wasn‘t right! (Laughs) So, luckily what he did on the recording is they played straight minor blues, you know, more traditional, something that we were all used to. That saved me, and it saved the tune.

DBJ: I want to ask you a little bit more about playing with Charles Mingus, but when you first came to New York City, one of your most significant gigs was playing with pianist Randy Weston.

JH: I played many more gigs with Randy than I did with Charles. And I liked playing with Randy much better than I did with Charles.

DBJ: I‘m guessing that the tune you recorded on Roulette, "To Randy," was written for Randy Weston.

JH: It certainly was! By the way, that‘s one of the first or second tunes recorded in 5/4 time. I remember dedicating this to him; he was standing in the club, and when I started to play, he walked out, so he never heard it! (Laughs)

DBJ: What are your recollections of performing with him? Did it influence you in any way?

JH: No, I don‘t think it influenced me, but what it did was it gave me a chance to really stretch out in ways that I really wanted to play eventually. See, I had bands here in California, in San Francisco, and I tried to convey the idea of playing modes here, in ‘57, ‘58, before I went to New York, and I could not get these guys to be able to deal with the concept. They couldn‘t do it. So, Randy wasn‘t doing modes, but he played with more of an approach that--musically, he was a maverick. His music was different. And it made me, you know, it was a challenge. And I loved his songs, his pieces were great and he gave me lots of space…We were at the Five Spot for 16 weeks. And I actually played with Randy before I played with Mingus. I played some other gigs with him, up in Harlem at Small‘s--the only time I ever played at Small‘s--and then I went with Charles the last week of ‘58. I played sporadically with Charles, but I did a lot of albums with him--but I played far more consistently with Randy than I did with Charles.

DBJ: You went with Mingus after he saw you playing at the Five Spot with Frank Foster, right?

JH: (Laughs) Well, Frank Foster and Thad Jones were with Basie. And that night they were--it was a Monday night, an off-night for the regular bands. They were late coming in… I was out looking for a gig, because my wife and I were broke…I‘d never, ever been in that position before! So I dressed up, you know, put on my blazer jacket and horn-rimmed glasses, and…I went down there mainly because I knew Frank was going to be there. I knew him from Bop City here when I was an 18-year-old kid. Frank was late, and Thad Jones were late, and nobody was playing the horn, so I asked the rhythm section if I could sit in. Well, I knew (pianist) Phineas Newborn, and I knew (bassist) George Joyner…(drummer) Roy Haynes I didn‘t. So we all said hello…there were a lot of musicians in there, but I was the only one who sat in. And I played three or four pieces, then Frank came in, and Idries Suliemann came in, the trumpet player, who‘d actually introduced me to Randy Weston…he came on the stand, and we did a tune or so. Then Thad and Frank came… and after a tune or so we came down. And then Charles came in, and I was sitting at the bar facing the bandstand and at one point when they finished a tune Charles said, "Hey, why don‘t you all let this guy play?" And they looked over at me and Frank said, "Well, he can play if he wants to." Well, everybody there knew I had played several pieces, right? But, so, Mingus says "Go up there and play!" I was a little embarrassed to go back up because I‘d been there, but I needed a gig and I just thought, "Well, hell, what the hell"…

So we played "There Will Never Be Another You" and I kind of played my ass off, I guess! And Charles went--oh, man, it was both embarrassing and very comical. He started saying, "Man, Bird‘s back! Bird is back!" (Laughs) He was so excited that he ran out the door… we had those big double- saloon doors…so he hit the doors, it was like he was gonna tear the place down. I was just killin‘ him so much he couldn‘t take it, right? (Laughs) He came back in the same way… so I got down off the stage and started to walk to the back. Sonny Rollins was sitting in this phone booth right by the door, and Charles yells, "Sonny! Bird‘s back!" and Sonny goes (deep, hoarse voice) "Yeah, yeah, Charlie." It was both embarrassing and funny. I wasn‘t prompting him… he said, "Hey, baby, are you working anywhere?" I said no. "Well, you‘ll open here with me in two weeks!"

DBJ: I know Mingus was a really intense musician to work with. What would you say was the best and worst thing about playing with Charles Mingus?

JH: Well, the best thing was when the music was good, it was wonderful. When it was bad it was some of the worst music I ever played in my life. And with his grumpiness--sometimes he was, it was so bad that I didn‘t want to be there, and that‘s why I didn‘t stay there. At the time Charles was very young, you know, he was only 35, 36 years old himself, he was not an old guy. But I just knew in my heart of hearts that something was wrong with him, that this guy was not just coming on like this. He was carrying some extra baggage, you know!

DBJ: Yeah, he really was a pretty complex character. You really did turn in some great performances with him, especially on the album that came out as Jazz Portraits. That was a live show in New York City, at the Nonagon Art Gallery…Whitney Balliett really raved about your playing at that show. Do you remember that gig at all?

JH: Oh yeah, as matter of a fact that was the first recording we did, and we were at the Five Spot on that first gig I played with him. It was the first week--Dannie Richmond only played the first week, because he got busted during our off-day, a Monday, and he didn‘t play the rest of that gig. So it was the first week, and we‘d finally gotten off the bandstand…Charles would get on the bandstand, and he wouldn‘t get off, he‘d play so long, and I thought it was very rude to Sonny Rollins (playing opposite the Mingus group). Anyhow, we were coming off the stand and he said, "Get on your coats and get your horns together, we‘re going around the corner and play a gig." And I thought this was crazy…it was December or January, bad weather in New York, sleet, snow, but okay, we did it. We walked about three or four blocks in the slush, and then we started up these dark stairs… we really couldn‘t see, and Charles is carrying a big bass in front of us. We opened the door, and the place was packed. I didn‘t know it was an art gallery, I didn‘t know where I was. They were waiting for us, and it really blew my and everybody else‘s mind. We went up and just played the way we‘d play on the bandstand--we went on, and that was--the magic was there, and we finished the set, put our coats on, put our horns back in the case and went back to the other gig. So while Sonny was on the bandstand, we went and played a concert, did a recording, and came back and finished the gig! (Laughs) I remember seeing Whitney Balliett, looking kind of Ivy League, wearing combat boots with a suit. (Laughs)

DBJ: Around that time, or sort of around that time, you did your first recordings as a leader. In the Vernacular you did in ‘59, and No Coast I think you did a year or two later…and they evidently got a good critical reaction. Musically speaking, were you happy with how they turned out?

JH: No, not at all. As a matter of fact, what happened is--you know, it was my first recording, and luckily… I‘d been playing with Charles at the Five Spot, and because of the two strong names (Mingus and Rollins) we had an audience every night. We got great write-ups, and I knew that I was on the spot, at the Five Spot especially, because, you know, I went to New York to have my own band, I never really went there to play with anybody. And I went there with my own music, my own book, as I‘d done a lot of stuff out here, with some very fine musicians. So, what happened is, I really work hard when I‘m on the spot and when I have to, I will deliver. And I was there to do that. And when Charles got written up, I did almost as much as he did and sometimes as much--as, like, the newcomer on the scene. And that‘s how I got a recording so early. My wife was my manager, and she was able to get that recording for Roulette Records. The reason that album--it could‘ve been a lot better. You know, I had never recorded before on my own, and we kept having to go over so many of those tunes because the drummer in my band was a kid from out here, and he just freaked…and I just got totally exhausted from going over those tunes. Richard Williams, the trumpet player, was much cooler, but I was worrying about the whole band, and the drummer just kept making mistakes, and some of that stuff was so hard (laughs)…and again, I‘m switching between the alto and tenor, I‘m playing one horn almost as much as the other, it got a little bit confusing…oh, this is kind of interesting…on the last day of the rehearsals for my first album, a piano player I knew came in with Kind of Blue. (laughs) And he insisted on putting it on--he said "This is Miles‘ latest, you‘ve gotta hear this, you won‘t believe it!" He put it on and I immediately heard a mode, a modal piece, and I said "That‘s what I was trying to tell these guys to do!" I stopped it right there, and I went over to the piano, Roland Hanna was the pianist, and I showed him, you know, a minor 7th, how to voice the chords…well, I didn‘t have to show him a lot, he grasped it very readily… so did George Tucker, the bass player…and I thought about it while we were in the studio, and Roy Haynes had to come and bail us out (on drums). So we did "Suggestive Line," (a piece Handy had written previously) and it was really the second jazz mode or modal piece, by virtue of the fact that I couldn‘t get anybody to understand it out here in San Francisco.

(To be continued. You can also read part 1of the Night Lights John Handy interview.)

Photo of John Handy: KQED

About Night Lights

John Handy Talks With Night Lights: Part 3

by David Johnson

February 2, 2008

In Part 3 of our interview with saxophonist John Handy, he discusses his troubled relationship with his first record label, his recording of "Alice in Wonderland" with Charles Mingus, why trumpeter Richard Williams didn't appear on his second album, his move back to California in the early 1960s, his Freedom Band civil-rights project, and the formation of his quintet that would appear at Monterey in 1965:

DBJ: You had some really good players on those Roulette records--trumpeter Richard Williams, who‘d also played with Mingus and Gigi Gryce…Don Friedman on piano, Lex Humphries on drums… were you happier with how the second Roulette album (No Coast) turned out?

JH: The only reason I didn‘t use Richard on that second record was that he‘d done something that really p***ed me off. On our gig at Birdland, my first major gig as a leader--which is a big deal, you know--on his birthday night--he and Don Friedman, the pianist, had the same birthday--well, Richard couldn‘t make the gig the next night. You know, this was my first time there, and luckily a trumpet player from here, Mike Downs, who recorded with Philly Joe Jones, was able to make the gig for one night. And I loved Richard, Richard was such a genius of a player, he could do anything…but it put me in such a bad mood, because I depended on him so much--you know, the second horn, and I‘d played with him out here (California)--and that‘s why I never used another horn player. Because Richard couldn‘t--I‘ll put it this way, he wasn‘t able to make the gig that night and almost didn‘t make the rest of the gigs, so…counter to what (critic) John S. Wilson said in New York that I was so overshadowed by him on the first album that I made sure I didn‘t use him the second time, it‘s not true. I didn‘t use him because he was not reliable. And I didn‘t use anybody else until I used a violin player.

DBJ: I read that review, and I wondered if that was really the story (behind Williams‘ absence from No Coast).

JH: I never even saw that little b*****d, and I really resent people saying things like that that put you in a bad light. They don‘t know you, they don‘t know what your reasons for--you know, I would never try to--even if Richard had played 10 times much as I, if I used him once I‘d certainly--I‘d played with him in many places. That was not the only thing we‘d ever done before. And we played a number of things with Charles Mingus, but I just wouldn‘t hire him again, because, unfortunately…we all knew that Richard was great on the first set! (Laughs) And after that he went downhill. He drank. And he was a wonderful, beautiful person, but he couldn‘t control his alcohol.

DBJ: Oh man, that‘s really sad.

JH: It hurt, because he finished college when he was 20 years old… I mean, he could read flyspecks, and he understood music, he was very bright, and likeable…oh, something else I meant to tell you about that first recording with Charles that we were talking about earlier. Horace Parlan, who was actually the pianist in the band when we did "Alice in Wonderland" at the Nonagon Art Gallery…he had gotten angry with Charles, and he decided not to show up for the gig. And Richard Wyands, who was from out here, sat in and played that difficult--especially that "Alice in Wonderland," he sight-read that. He never played with (Mingus) again as far as I know…I believe I recommended him because I knew he was there.

DBJ: "Alice in Wonderland" did sound like it must have been a pretty difficult piece to learn. How many times had you had a chance to practice that before you guys actually recorded it?

JH: That‘s the only piece that I ever had conflicts with Charles. I was new in the band, and instead of giving us music he‘d hum the damn tunes, or play it on the piano. And you know, I was right out of college, I was used to reading, playing in tune…as a matter of fact, many times they wouldn‘t tune to the piano, they‘d tune to me. Because our school out here, our bandleader-saxophone-clarinet teacher Ed Kruth was very strong on playing in tune. Anyhow--the piece seemed--I said, "Why don‘t you give me the music? I can learn this, I can read it…" Well, he got angry, that was our first and only argument pretty much about music, per se. He finally brought it to me, and it was so difficult to…(laughs) he made every effort to write it in a way that…it was difficult to read, but it wasn‘t impossible. I thought it was crazy, making all those crazy (imitates mournful-bray passage) crazy sounds in there; I didn‘t really go there to do that. (Laughs)

DBJ: I just wanted to ask you one more question about Roulette. You had a contract to do 10 records for Roulette, and you ended up doing three. What happened to make you leave Roulette?

JH: Well, I noticed a lot of the same things happening to other musicians. They were very sloppy in the production, they didn‘t give you very much--the money was embarrassing, that they give you…It was more than the musicians‘ scale if you were the leader, but side people only made the scale; and they never gave you any accounting of how much was sold, and they did this through the years, and I just couldn‘t--I couldn‘t…music, no matter how easy it might come or how much work you put into it…you know, I was very diligent about the music, especially those things with them (Roulette). I wrote all of that stuff, I had my own charts done when I was still a student, I worked hard, had good people, we practiced…and you know, for someone to put out a few thousand dollars to not ever--oh yeah, then they wanted to take your music, put it in their publishing companies. And to me it was like, when I got to know what sharecropping was like! That‘s what it‘s like--you‘re always in debt to the boss, or the owner. And that was b.s., it was insulting, demeaning, and I just couldn‘t do it. I mean, if I‘d been beaten up--and I would‘ve fought back to the last breath (laughs)--for people like that, I didn‘t respect them, because this was wrong, and it wasn‘t just Roulette. It happened at the other companies too. I just simply wouldn‘t--they wouldn‘t do right, they were cheating, they weren‘t coming up with their part of the contract. And I put the music down, the labor, the time, all those years I could not record for them, and I still can‘t record for them.

DBJ: Well, I know Roulette in particular was reputed to be a rather shady label. What was going on in the early 1960s that prompted you to leave New York and go back to San Francisco?

JH: Basically to finish school, to get my degree at San Francisco State. I had--another thing went on there, that was just… appalling. Well, I was not a great student in college. By the time I got in college, I wasn‘t doing great, but I did more than passing, and I always did something--when I had assignments, especially when it came to the creative part, I got encouragement, because I always did something original, and obviously, it was good. Because of my experience and my knowledge of harmony and theory, I never had to take the preparatory courses; I took an exam for those. I thought I had graduated when I went to New York, and they never sent me my degree, and I kept getting--I even came back, went to summer school, and they still lied to me. They just out-and-out lied to me. So that‘s why I came back… That, and the recording situation, I just decided I‘d go back to school and they‘d have to give me a degree of some kind. So I came back, and I got married a second time, and bought a house. I had this big house, and that just kind of kept me here, and I was doing some wonderful things with musicians and bands of my own out here. I just hung tight until the thing happened with playing at Monterey in ‘65. So I got a new contract… and I ran out of the contract with those guys. They could‘ve gotten 10 albums from me; if they‘d treated me right, I might‘ve given them more. And the same thing with Columbia--I didn‘t give them but four. They were a lot better, but just by a matter of a few degrees

DBJ: Is that how--you know, one of the articles I read from the mid-1960s alluded to rumors that the mob had been after you in New York, and that that‘s why you left. In the article, you totally discounted that; you said "No, I just went back to go to school." But did those rumors start in part because--Roulette was said to have some gangster affiliations, wasn‘t it?

JH: Well, yes, that‘s what I was told. Charles even told me that, and it became almost apparent…when I was with him, after we‘d played the Nonagon Art Gallery, a week or so after, I was very surprised and flattered that he asked me to go with him to edit that album (Jazz Portraits). And he didn‘t have to, I was just another sideman. He took me with him over to New Jersey; I guess that was Rudy van Gelder. By going to that and watching Mingus and him work together, how they edited, how they spliced a lot of things together or took some things out… I was amazed how that could be done, and it seemed fairly simple. That helped me to edit my own album. But as to having been run out of New York, I don‘t know anything about that. (Laughs) Nobody told--nobody threatened me, ever. I went in a number of times to see Morris Levy, the owner of Roulette, the president, and he was always a very nice guy; he was never rude. He never said anything threatening to me; he simply didn‘t pay me! (Laughs) The rumor, I have no idea where it came from, and I‘m not easily terrified. You know, I fight back, I don‘t care who it is-

DBJ: You were in a band with Charles Mingus! (Laughs)

JH: Well, it didn‘t matter with him, because Charles wouldn‘t--we never had any fights, and that‘s why, you know-it‘s an attitude. Like, everybody can be hurt, I don‘t care who they are. (Laughs)

DBJ: I‘m just saying you‘re obviously pretty fearless if you were in a band with Charles Mingus.

JH: Well, actually--fear makes me angry. If I‘m frightened, I do get angry, because I don‘t want to be in that, and the only way to get out of it most of the time is to let people know that there‘s a price to pay if they become violent. I‘ve never had any trouble; I‘ve been able to walk away from everything. I‘ve never looked for anything, but I feel that they don‘t want to either. (Laughs)

DBJ: I wanted to ask you, John, about something you did out in California in the early 1960s, called the Freedom Band. It was a nine-piece band, I guess that you had, and I think the tune on New View called "Tears of Ole Miss" kind of grew out of it. Can you tell me a little bit about that band?

JH: Yeah, as a matter of fact that was a band I organized to raise funds for the civil-rights movement in the years ‘64, ‘65, right in there… it was about a nine or ten-piece group, usually three saxophones, a couple of trumpets, and trombone and piano and rhythm section. Eddie Henderson (trumpeter) was in that band at one point! Eddie told me that it was his first gig. And he wasn‘t a kid; he was young, 23 or so, but he was married and had a couple of kids. The Freedom Band, there were times, depending on the personnel, when it was a very good band. But you know, we lived in California, and especially then there was no coverage… we did have a couple of guys who came out and listened, but there was never any writeup. It would‘ve been fine, had it happened, but we did what we did. We raised money, and then we started to be hired for the fact that the band was very good. That was my first time writing, in a jazz setting, for more than five pieces, so that helped my writing. We also had a vocalist, Heather Evans…it was a very good band. I still have that book, and I‘m thinking about doing some gigs with it. Maybe recording it some day, you know.

DBJ: That‘d be cool. I‘m going to jump ahead a bit and ask about Monterey. I know you‘d known violinist Michael White since high school, but how did he end up joining your group around 1964?

JH: Yeah, in high school days we were sitting next to each other in the boys‘ choir. When I moved here, I came right in the midst of the semester, and Michael was a tenor and I was a baritone singer. I didn‘t see him again till I was out of the Army, 23 or so. I came over to San Francisco from Oakland for a jam session, and there he was, playing violin. I ran into him again a few years later--I can‘t even recall how we ended up meeting again--but immediately I got him to join my group. And we were doing "The Spanish Lady." I had played it the first time, written it in Canada, and we were playing it, and at that time Charlie Haden was here, Charlie was in the band, and we had a guitar player, and a year later we did the Monterey thing. Freddie Redd, the pianist from New York; he was out here, and I had a gig in Vancouver and took those guys, Freddie and Michael, and we went up there and ended up with the bassist and drummer, Terry Clarke and Don Thompson. They couldn‘t believe how those guys could play and how the band sounded. So that‘s how I started that band.

DBJ: The instrumentation of that group was so unusual--you eventually replaced Freddie Redd with a guitarist, Jerry Hahn. How did that sound come about? Was that kind of something that you‘d heard in your head, or was it partly just circumstances, or-

JH: It was kind of happenstance, because--I keep forgetting this, but there was a guy in my band who was from Canada who played guitar…he actually was in the band playing guitar before Freddie Redd, before Jerry Hahn. And we didn‘t record, but we started playing that piece with him in it. And then Freddie Redd played piano, and that gave it a different texture. And I liked the way Freddie sounded. But Freddie kept doing some stupid stuff. After I brought the bassist and drummer, Terry Clarke and Don Thompson, down from Vancouver, he (Redd) was the first person in my band to ever get fired. He started playing solos right on top of any of us--if we played on the head, he was okay, but when I played he would play solos on it, Michael White… so I had to fire his a**. And that‘s how Jerry Hahn was here. And Jerry had been in the Freedom Band, and I knew how he played, but I didn‘t know he could play the Spanish thing. I knew he could play the blues, and we got together, I showed him what I wanted, and he sounded better than anybody else who‘d played on it.

(To be continued. You can also read part 1 and part 2) of the Night Lights John Handy interview.)

https://indianapublicmedia.org/nightlights/john-handy-talks-with-night-lights-part-4.php

John Handy Talks With Night Lights: Part 4

by David Johnson

February 5, 2008

In the conclusion of our four-part interview with saxophonist John Handy, he discusses why his quintet broke up, playing Bartok with classical pianist Leonid Hambro, a forthcoming Mosaic Records collection of previously-unreleased 1960s recordings, his experiences as a jazz educator, and his memories of Monterey and the mid-1960s rock scene. To hear some of Handy's music from the 1960s, check out Handy On the Horn in the Night Lights archives.

DBJ: Yeah, well that band has an incredible sound. Ralph Gleason, I know, had heard you at the Both/And in San Francisco and started writing about you, and then you were this big hit at Monterey in ‘65. What do you think were the factors that made that appearance such a success for you?

JH: Well, the music was so powerful. That piece in particular ("The Spanish Lady") but we also did another piece, "If Only We Knew," another modal-type thing that I‘d actually written back in 1956, when I was a student. I wrote it originally for piano and viola. I incorporated it and the band changed the arrangement and gave it more of a rhythmic motif that was not originally--it was more classical when I first wrote it.

DBJ: That Monterey group almost seems to anticipate fusion in some ways--and I‘m guessing that Miles Davis must have heard you, either live or on record. Did you ever hear what he thought of that band?

JH: Miles Davis--when we played a number of concerts…this was when he had Wayne and Herbie and those guys, and Trane had Elvin… we didn‘t play opposite Trane, we played opposite Miles several times. And I remember when we played across the street from each other, Miles would always be in there, listening to us. He did like the band. He liked the band I had at Birdland, with Richard Williams. He loved Richard Williams! But yes, Miles… I‘ll put it this way, someone--we dated the same person, several of the same people, and you know, they‘d fish around to ask questions like this, and I was told this by more than one person, that Miles, when he was asked "What do you think about John Handy?" would say (imitates Miles‘ hoarse whisper) "He knows what he‘s doing…he knows what he‘s doing." (Laughs)

DBJ: (Laughs) That‘s a great story. Did the quintet ever play live much outside of the West Coast? Did you ever take that band around the country much?

JH: No. It‘s amazing, we played almost all West Coast--California, Vancouver, Seattle, Portland…we only played about four western states, and in 1966 we came within two points of tying the most popular jazz band in the country, Miles (in a Downbeat poll) and we‘d never even gone to New York, or Chicago, or any place out of here.

DBJ: Why did you never go to New York or Chicago?

JH: Actually, it was bookings, to an extent. You know, we were working all the time, and I thought about it, but we were so busy working here…and I didn‘t really have the management… There were people interested, but there were also--I‘m just kind of a strange and different guy, I guess. There were people who wanted to manage us, including the late Monte Kay, who had the Modern Jazz Quartet from its inception…they wanted to do certain things, and you know, I wasn‘t going to give 35 to 50 percent of my earnings to anybody. And so, he got us some very interesting gigs out here; we were making a living out here. And I‘d lived in New York, I‘d played in New York as a headliner, I‘d done just about everything that everybody else had done there. A month at the Five Spot, I‘d had gigs like that, a month at the Village Gate… you know, that‘s about as good as you‘re gonna get during those times, right? We were doing festivals, we did Monterey twice, we did, up and down the coast, new festivals… University of California, we played at Stanford. Life was pretty good when you consider we weren‘t traveling that much.

DBJ: Why did the Monterey quintet eventually break up?

JH: Mainly--there were some things that went badly in there, where I had some problems with the drummer…he was going through some social things, growing up in another culture and not quite knowing who you are and what you are…but I think it really started with Michael (White) and Jerry Hahn. The real truth is like a lot of groups--jealousy. Jealousy. Jerry Hahn was the first one to leave. Jerry just went berserk one day when we were getting out of our van in Denver, our first time there…He fired himself, I‘ll put it that way. And then so did Michael, about a month later… I had to fire each of them on the spot. And Mike lived only a block away from me, and a couple of years later we talked it out and we started again in another band, where I had Mike Nock on the piano playing with us… (laughs) and they stole the band while I was in the hospital, and it became the Fourth Way!

DBJ: When I first called you you mentioned some sort of forthcoming Mosaic issue with Michael White…

JH: Yeah, there are some of the recordings that we did with Columbia…we did some studio pieces that were not released. And so they‘re going to release them, along with some takes on pieces that we‘d already recorded before, with different solos and that kind of thing. So they‘re doing this after- (laughs) how many years is that, 40?

DBJ: Is it going to be a single CD, or a three-CD set, or-

JH: No, I don‘t think there‘s enough for more than one, or two, maybe. For instance, we‘re doing, not only with Michael White, but I did a Carnegie Hall Spirituals to Swing concert with John Hammond in 1967…they‘re putting the whole performance together. John Hammond would splice my tapes and never say a thing about it, you know, and I just rode with it. But on the other hand it‘s probably good that he didn‘t release some of it! (Laughs)

DBJ: You know, all of your Columbia records--The Second John Handy Album, New View, Projections--they reflect a pretty wide musical spectrum. When you look at the arc of your whole career, you‘ve gone down a number of different musical paths. What do you think created this open-minded interest that‘s led you to compose musical pieces for orchestra, and you‘ve played Bartok‘s Night Music with classical pianist Leonid Hambro, and you‘ve played with people like Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan-

JH: Where‘d you get all this information? Man, nobody knows all this stuff. That‘s amazing! (Laughs) Wow, that‘s great. I was very proud of that concert (with Hambro). I have to tell you something--I don‘t like to put anybody down, but when people put you down for the wrong reasons, or even the right reasons…John S. Wilson came to the concert that I did with Leonid Hambro. I was in a jazz organization and we sponsored that concert at Huntington College, with Cannonball‘s quintet, Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, and my band. And Don Friedman was there--I think Addison Farmer was the bassist. Anyhow, a member of my band said, "Man, you played better than I ever heard you play!" You know what John S. Wilson said? My playing was "bland." And you know, I really trust the musicians, and I trust myself…I did play well. "Bland," I don‘t think I‘m quite bland in anything….even if I‘m not good, I‘m not bland. (Laughs)

Anyway, God, I forgot that--Night Music! What happened with that--I‘ve forgotten how Leonid and I got together, but I remember him coming to my house and playing this music for me, and he broke--(laughs)--he played so strongly that he broke the pedals on the piano! (Laughs) And he never paid for it! (Laughs) Anyhow, I took a theme, a motif from Bartok‘s Night Music, and I wrote it out for the band to play with Leonid Hambro, where we improvised on it…and you know, it wasn‘t the world‘s most, or greatest discovery of music, but it was viable, it was interesting, it was a collaboration, and we had fun doing it, and the audience enjoyed it too. The musicians did… we were pleased with it, we weren‘t embarrassed, as this little b*****d said, who said we were "bland." (Laughs)

DBJ: It (that concert) seems like part of this whole overall pattern with you, where you really have been pretty open-minded and pretty courageous about exploring a lot of different kinds of music in your career.

JH: You just do it, I guess, because--we moved a lot when I was a kid (laughs) so my exposure to cultures and different people--and I have a curious mind. You know, on The Second John Handy Album, I don‘t know if you read this but the piece called "Scheme #1"…well, Joe Webber, a bandmate of mine at San Francisco State--at 21 he was writing symphonies (laughs) and I mean they were great for a young guy…well, Joe called me one morning, at like 7 in the morning, and he said, "John! This is Joe Webber! Did you know that Stravinsky used your piece in a lecture? He thought it was some of the best fixed and improvised music that he‘d ever heard!" And you know, of course I was flattered…(laughs) first of all I was a little miffed that I‘d gotten a call that early from Joe, who‘d called me maybe a couple of times before, but always at the right time of day. But he was excited and of course it excited me, because he‘s the kind of guy who would know Stravinsky, and maybe call him at 2 or 4 or 7 in the morning. (Laughs) He was one of a kind, very talented, but I‘ve never heard from him since then. By the way, I wrote that piece for a recital that I organized and presented at Carnegie, I think in ‘62, and our pianist was Bill Evans. In ‘66 we were playing that piece and he was playing opposite us at the Both/And in San Francisco… or maybe it was at the Vanguard, I‘m not sure… Anyway, the reaction (to the piece) was not crazy, people weren‘t totally enthusiastic, but Bill told me, he said, "Man, I think you guys play the most sensible and musical avant-garde of that style of anybody that I‘ve heard." And I didn‘t think about it at the time, but he played the original piece, and maybe he remembered it and I didn‘t remember that he was on it. We did it with a quartet with Charlie Persip playing the drums, who just totally tried to ruin the concert, and a friend of mine, a bass player, Julian Yule, who doesn‘t live in New York anymore.

DBJ: I wanted to ask you about another kind of music, rock ‘n roll, which was provoking a lot of reaction in the 1960s jazz world. Some musicians were really, you know, kind of angry about it and railing against it, and others were trying to incorporate it into their sound. What was your take on it?

JH: We were in the heart of it, right here (in San Francisco). Our band, that same band with Michael White and all, we were the first headliners at Fillmore West, the Bill Graham rock ‘n roll headquarters. But we didn‘t play…Bill Graham and I got in an argument and we didn‘t play that night. But the poster still exists, with the John Handy Quintet as the headliner, and it‘s for sale. We had done three benefits for him--he was helping, it was a fundraiser for a mime troop here. Well, we played opposite almost all of those guys…as a matter of fact, many times they played second to us. You know, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Janis Joplin lived about half a block from me. People like that, Jefferson Airplane…these guys came up, Santana, listening to us, the ones who ventured out to hear jazz. We played opposite them, and to be honest, we always took the crowd, because even young people who were there to listen to rock ‘n roll, when we played "The Spanish Lady"… in Orange County we played with the Lovin‘ Spoonful, who had a hit record out, and they came in so cocky one night… we (the Handy group) had been on this gig for five weeks, and they didn‘t even say hello. I‘ve never seen such amateurs, such bigshots, and they weren‘t…They came in with a whole entourage, and the bass player had played there before with someone else, and he was OK…Jim somebody…but the rest of them were just, you know, basically damn near amateurs, and didn‘t even say hello or acknowledge us. So we went on first, they were the stars, and we played for all these blond, suntanned kids…we were right on the beach, the ocean, the Golden Bear at Huntington Beach…we brought the first black kids from Watts out there, not long after the (1965) riots. As a matter of fact they wanted us to play a command performance in Watts, and I said, "Man, we can‘t go to Watts…our band is three-fifths white!" He (the promoter) said, "Man, you guys don‘t have to worry about that…the guys who are raising all the hell are policing the place." So we went, and it was wonderful.

But anyway, the Lovin‘ Spoonful, those young people who were there, when we played we looked around and the crowd was like, "What?" And when we finished they were standing on the tables, they went crazy. And Lovin‘ Spoonful went on--you know, they weren‘t experienced, and they hadn‘t played many gigs, obviously. And they couldn‘t get their music together, and they almost got booed. Anyway, we played opposite a lot of those (rock ‘n roll) groups, and most of those guys were very nice, we liked them, and that rock ‘n roll crowd--this is what John Hammond realized, why Bill Graham wanted to put us in the Fillmore, that we had the crowd before they did. We were the musicians. And we could play something like "The Spanish Lady," and they‘d stop dancing and sit down and meditate on the floor. I‘m telling you, man, it was phenomenal. Given the chance to be exposed, the rock ‘n rollers were… I got to know Steve Miller in a gentleman‘s organization here, he was around here then, and he talks about those times when he was just a kid…I knew a bunch of them (rock n‘ roll musicians), the Charlatans and some of the groups that didn‘t make it, and some of the guys who had even been my students…some got in there and did very well, and some did nothing. And again, unfortunately a lot of drugs got in their way, you know.

DBJ: Talking about students, you were a very early advocate for jazz education. You started teaching early, and in a 1960 Metronome article you‘re already talking about how important you think it is that jazz eventually be taught at the university level. And you spent a long time teaching at San Francisco State…What did or does a typical John Handy jazz class consist of?

JH: Well, that would take a long time because… (laughs) I basically taught a historical survey of jazz, the beginnings, like most people would, but I think in a lot more detail, because I even knew people like Pops Foster, who was one of the first guys to popularize bass solos. And he used to come by my house without calling me, during that time. I knew those people, I knew Turk Murphy, and I‘d even played with some of them, played a bit of that music too. So I knew a lot of that firsthand, as well as bebop…I‘d played big bands, and so I could tell them not only that, I could demonstrate it. And I was lucky enough, I had Mingus‘ sextet in my class to demonstrate some of his things…Monk was in my classroom with the quartet…Sun Ra with a 14-piece band…(laughs) I had some guys come in who were so far out that they even called the security on us. They didn‘t hurt anything, but they were so crazy that one of my students thought they were going to tear up the place! (Laughs) I had the students writing blues charts, blues choruses, and they loved it, some of them were very creative. And a little later we had Black Studies, where I went more into African music and music from other parts of the globe, and showing the kinship and how it corresponded with things we know and techniques that we use in the music. So I really enjoyed it for most of the time…I stayed much longer than I should‘ve, but I didn‘t know when to quit. (Laughs)

DBJ: I know Monterey was obviously one high point for you in your career, but what, from the vantage point of 2008, have been some other high points for you?

JH: Oh, playing my first concerto with the San Francisco Symphony was a triumph, about as high as Monterey for me, because Arthur Fiedler gave me a real hard time, even racially, and he had to eat his words…It turned out that we broke all attendance records in the Symphony‘s 25-year history (at that point). And it prompted him to say later that year--around 1970--somebody asked him who his favorite saxophonist player was, and he said, "John Handy." (Laughs) That was in Time Magazine, by the way, November issue. And I‘ve written one, another concerto, that was done in June three years ago, premiered here…and I played a lot with the people from India, with Ali Akbar Khan and recorded with Ravi Shankar…as a matter of fact I might be going to New York City with Zakir Hussain, the great Indian drummer, tabla player, whose father played with Ravi Shankar for many years before he passed.

DBJ: This might be a bit of an off-the-wall question, but can you tell me the background behind that hat you wore on the cover of the Monterey album?

JH: It‘s called a tea cozy. I won ten dollars from Freddie Redd--he challenged me to wear it on stage, and I was just kind of doing it as a joke, because I‘d already won the ten dollars. Somebody gave it to me in Vancouver when we‘d been up there, and I came to rehearsal, walked into the rehearsal room at my house with this hat on, and everybody started laughing, and Freddie said, "I‘ll bet you won‘t wear that tonight"…we had a regular gig at the Both/And and he said, "I‘ll bet you ten dollars you won‘t wear it." So I did, and then I kind of got used to it…I did it too many times, but I got used to it, and I forgot to take it off for a couple of years.

DBJ: What‘s your remembrance of that night at Monterey? Could you tell pretty much right away that you‘d done something special that night?

JH: Not right away. One of the reasons why--it was afternoon, so you could see the audience and all…but the band was a working band, we were working six nights a week, so we did that music every night. And what‘s amazing is these guys--we were on an emotional level and a creative level close to what Trane and those guys were doing, and people knew it. We just got into the music and you didn‘t think about it. Denny Zeitlin went on first, with Charlie Haden and Jerry Granelli. They had been in my band in ‘64, when Mike White had just come into the band. They could have come and played that music just as well. And they went on and played so well, Denny‘s music, that I was just thinking, "What the hell are we gonna do after these guys?" And it‘s unfortunate that they didn‘t get more credit. But yes, we went on, and we just--we all did what we do. And we supported each other, and each time I hear that record--which is not often, sometimes I go five or ten years without hearing that music--I think, "Good Lord, I didn‘t know Jerry was doing that, I didn‘t know so-and-so played like that… I kind of remember my playing…but one thing I remember--I got a little miffed because Jerry Hahn missed a cue. He went to the coda before he was supposed to…(laughs) I got a little mad at him, but he‘d had an accident and broken his nose, and I think he was kind of dizzy from the accident (laughs), so I forgave him. (Laughs)

DBJ: John, I want to thank you so much for all of your time. You‘ve been extraordinarily generous with it…

JH: David, you‘re welcome. It‘s been fun; I really appreciate the questions, and you‘ve prompted me to start rattling here, and I don‘t know when to stop. Thanks very much for thinking about me.

About Night Lights

Listen to jazz artist John Handy's collaborations with India's classical music greats

This is fusion at its finest.

by Nate Rabe

June 26, 2016JOHN HANDY & MAHARAJ BROTHERS

August 8, 2012American jazz artist John Coltrane’s experiments with twin basses to effect the sound of the tanpura in the early ’60s is often cited as the moment when the impregnation began. Others point to Jamaican saxophonist Joe Harriot’s collaboration with Indian composer John Mayer beginning in the mid-1960s as the first time the term fusion was used in jazz.

A case could also be made that it was actually Uday Shankar’s adventurous blending of Indian and western dance styles in the 1930s that created the cultural consciousness for an East-West fusion in music.

Whoever eventually gets the credit, there is no doubt that by taking a dip in the musical sangam of Indian classical music and jazz, many musicians from both traditions have tapped into deep streams of creativity.

Within the jazz fraternity, American alto-sax player John Handy’s collaborative work with various Indian classical artists stands out for its beauty and finesse.

Handy, now 83, keeps a low profile. But his career as a music educator, sideman and leader dates back to the late 1940s and includes stints in R&B bands, Count Basie’s big band and an intense few years with the prickly bassist Charlie Mingus.

Handy’s adventurous spirit can be seen in the music of John Handy with Class, his band of the last 23 years which features three female violinists cum vocalists! It is also exemplified in his collaborations with some of India’s finest musicians, which we explore this week.

Ganesha’s Jubilee Dance (with Ali Akbar Khan and Zakir Hussain), Karuna Supreme

Handy’s ties with sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan began in 1971 at the Ali Akbar College of Music in California, which Khan had established just a few years previously.

The two became close and Handy considered Khan a rare genius. “His alaps, they could make you cry!” he once told a journalist. The two played together for several years before making 1975’s stellar record Karuna Supreme.

The album, which also included tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain, then the director of percussion at Khan’s College, is universally regarded as one the best examples of East-West fusion ever made.

Hussain, whose first jazz recording this was, opens the piece with flourish and is quickly joined by Khan plucking a folk-like melody line. Handy enters seamlessly before the two embark on a set of alternating solos that leave the heart pumping with joy. Those who haven’t heard this album should definitely seek it out. It shimmers with lustre like a precious deep sea pearl.Raag Hinglaj (with Maharaj Brothers)