SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER THREE

DONALD HARRISON

(October 2-8)

CHICO FREEMAN

(October 9-15)

BEN WILLIAMS

(October 16-22)

MISSY ELLIOTT

(October 23-29)

SHEMEKIA COPELAND

(October 30-November 5)

VON FREEMAN

(November 6-12)

DAVID BAKER

(November 13-19)

RUTHIE FOSTER

(November 20-26)

VICTORIA SPIVEY

(November 27-December 3)

ANTONIO HART

(December 4-10)

GEORGE ‘HARMONICA’ SMITH

(December 11-17)

JAMISON ROSS

(December 18-24)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/missy-elliott-mn0000502371/biography

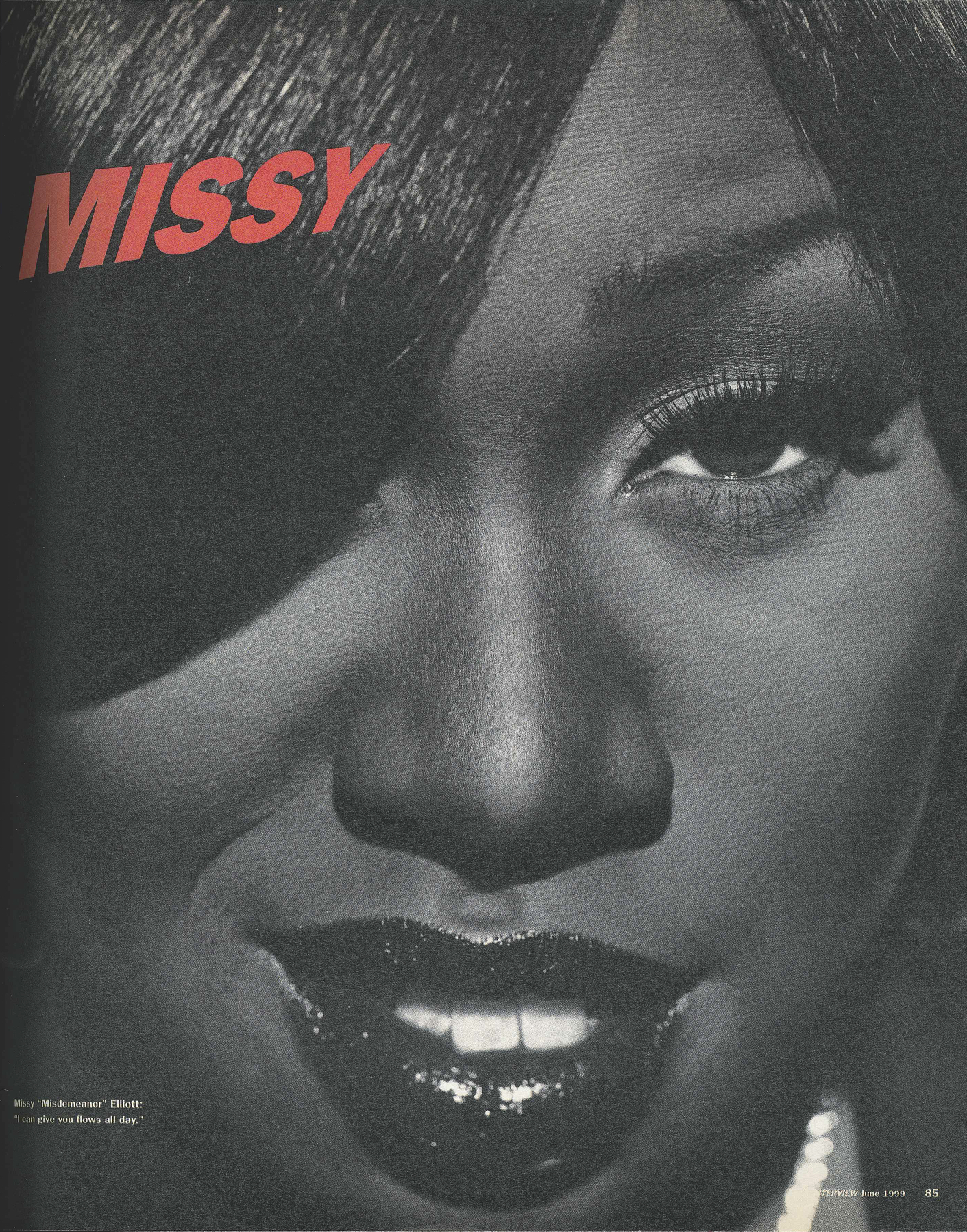

Missy Elliott

(b. July 1, 1971)

Artist Biography by Andy Kellman

Few artists have had the cultural impact of Missy Elliott, her visionary presence as both a producer and an artist reshaping the entirety of rap and R&B that followed her. From worldwide breakthrough-producing hits for artists like Aaliyah and Tweet to Grammy Award-winning solo albums, Elliott put her stamp on the music industry at large throughout the late '90s and 2000s. Even when slowing down on her solo output in the 2010s, Elliott continued working as a producer, and her watershed albums like 1997's Supa Dupa Fly and 2002's Under Construction changed the course of commercial rap and R&B for years to come.

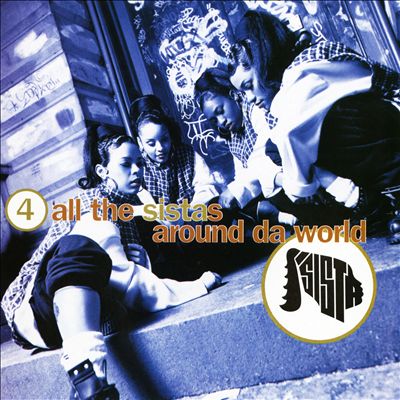

Born in Portsmouth, Virginia, in 1971, Melissa Arnette Elliott began her professional career when Jodeci's DeVante Swing signed her group Sista (previously Fayze) to his Elektra-affiliated Swing Mob label. Elliott, who was also part of the Swing Mob collective behind the scenes, subsequently left her first Billboard chart impression in 1993 as the co-writer, co-producer, and featured vocalist on Raven-Symoné's number 68 pop hit "That's What Little Girls Are Made Of." The following year, "Brand New," a Sista single written and fronted by Elliott, touched number 84 on the R&B/hip-hop chart. Its parent album, 4 All the Sistas Around da World, was shelved in the U.S., but Elliott shrewdly remained beside fellow Swing Mob member Timbaland and worked extensively with him on Aaliyah's 1996 album One in a Million, the source of the chart-topping singles "One in a Million" and "If Your Girl Only Knew." The move proved to be key, as the album racked up enormous sales and led to sessions with other artists and a recording contract with Elektra. Her debut as Missy Misdemeanor Elliott, Supa Dupa Fly, hit the streets in 1997 and went platinum within two months. Along with name-making tracks such as "Sock It 2 Me," "The Rain," and "Beep Me 911," it contained an astounding crop of album tracks that naturally emphasized Elliott's versatility. By the end of the '90s, Elliott added to her list of production and songwriting feats with hits like Nicole's "Make It Hot," Total's "Trippin," and 702's "Where My Girls At?" as well as work for Fantasia, Monica, Tweet and others.

Into the mid-2000s, as a steady succession of emerging and established artists was boosted by her songwriting and production, Elliott released five additional albums that, like Supa Dupa Fly, went double platinum. Da Real World, her much-awaited second album, was even more ambitious than her debut, featured appearances from Aaliyah, Eminem, and Beyoncé, and included her first headlining Top Ten pop hit, "Hot Boyz," also her first solo platinum single. Around this time, her mainstream status was further affirmed with appearances in television ads for clothing and soft drink brands. The cycle repeated itself in 2001 with Miss E...So Addictive, powered by the nutty "Get Ur Freak On." Another Top Ten smash, the song was a Grammy winner in the category of Best Rap Solo Performance, the same year Elliott's work on a cover of Labelle's "Lady Marmalade" was acknowledged with the award for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals. Elliott's winning streak continued a year later with album four, Under Construction, and its hits "Work It" and "Gossip Folks," which were somehow old-school reminiscent and alien-futuristic at once. The former hit made Elliott a repeat Best Rap Solo Performance winner. Her music machine continued to pummel the charts with This Is Not a Test! in 2003 and The Cookbook in 2005, full-lengths that didn't require event-level singles to sell over two million copies each. Respect M.E., a straightforward anthology, was released in 2006 in several territories outside the U.S. Multiple discs showcasing her songwriting and production work could have been assembled around the same time. By the end of the 2000s, in fact, she had added Tweet's "Oops (Oh My)," Ciara's "1, 2 Step," Fantasia's "Free Yourself," and Jazmine Sullivan's "Need U Bad" to her ever-lengthening list of hits.

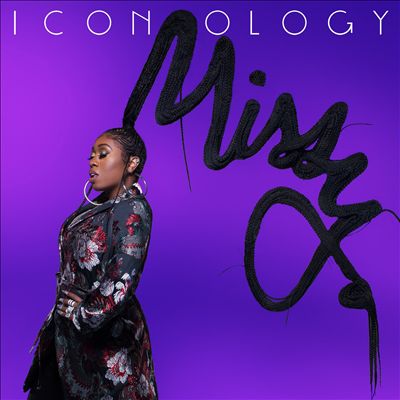

The seventh Missy Elliott studio album, tentatively titled Block Party, remained elusive for over a decade. Elliott revealed in 2011 that she had been living with Graves' disease, a thyroid disorder that kept her from the studio. Into the late 2010s, she worked primarily in the background with Keyshia Cole, Jazmine Sullivan, and Monica. Her own releases were sporadic, limited to a handful of tracks highlighted in 2015 by the platinum-certified Pharrell Williams collaboration "WTF (Where They From)." Meanwhile, Elliott performed at some high-profile events, including the halftime show of Super Bowl XLIX and the 2018 Essence Music Festival. After hinting that she'd been working on new material, Elliott released the five-song Iconology EP in August 2019. Though slight, the EP produced several charting singles, including "Cool Off."

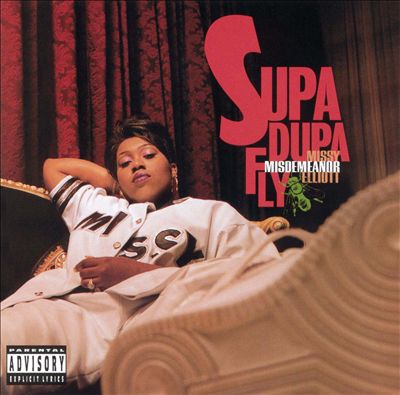

https://www.allmusic.com/album/supa-dupa-fly-mw0000594733

Supa Dupa Fly Review

by Steve Huey

AllMusic

Arguably the most influential album ever released by a female hip-hop artist, Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott's debut album, Supa Dupa Fly, is a boundary-shattering postmodern masterpiece. It had a tremendous impact on hip-hop, and an even bigger one on R&B, as its futuristic, nearly experimental style became the de facto sound of urban radio at the close of the millennium. A substantial share of the credit has to go to producer Timbaland, whose lean, digital grooves are packed with unpredictable arrangements and stuttering rhythms that often resemble slowed-down drum'n'bass breakbeats. The results are not only unique, they're nothing short of revolutionary, making Timbaland a hip name to drop in electronica circles as well. For her part, Elliott impresses with her versatility -- she's a singer, a rapper, and an equal songwriting partner, and it's clear from the album's accompanying videos that the space-age aesthetic of the music doesn't just belong to her producer. She's no technical master on the mic; her raps are fairly simple, delivered in the slow purr of a heavy-lidded stoner. Yet they're also full of hilariously surreal free associations that fit the off-kilter sensibility of the music to a tee. Actually, Elliott sings more on Supa Dupa Fly than she does on her subsequent albums, making it her most R&B-oriented effort; she's more unique as a rapper than she is as a singer, but she has a smooth voice and harmonizes well. Guest rappers Busta Rhymes, Lil' Kim, and da Brat all appear on the first three tracks, which almost pulls focus away from Elliott until she unequivocally takes over with the brilliant single "The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)"; elsewhere, "Sock It 2 Me," "Beep Me 911," and the weeded-out "Izzy Izzy Ahh" nearly match its genius. Elliott and Timbaland would continue to refine and expand this blueprint, sometimes with even greater success, but Supa Dupa Fly contains the roots of everything that followed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supa_Dupa_Fly

Supa Dupa Fly

Supa Dupa Fly is the debut studio album by American rapper Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott, released July 15, 1997 on The Goldmind and Elektra Records. The album was recorded and produced solely by Timbaland in October 1996, and features the singles, "The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)", "Sock It 2 Me", "Hit Em wit da Hee" and "Beep Me 911". Guest appearances on the album include Busta Rhymes, Ginuwine, 702, Magoo, Da Brat, Lil' Kim, and Aaliyah. The album was recorded in just two weeks.[3]

The album received acclaim from critics, who praised Timbaland's futuristic production style and Elliott's performances and persona. It debuted at number three on the US Billboard 200 and topped the US Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart. The album was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and has sold 1.2 million copies in the United States.

In 2020, the album was ranked 93 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[4]

Background and recording

While in high school, Elliott formed a group called Fayze—later to be renamed Sista—with three of her friends.[5][6] The group attracted the attention of record producer DeVante Swing, who was part of the R&B group Jodeci. After being signed the Swing Mob record label, Sista recorded an album in New York, but the album was never released. This led to subsequent termination of Sista's recording contract. Elliott returned to Portsmouth, Virginia, where she and record producer Timbaland began writing songs and contributed to singer Aaliyah's album One in a Million. In 1996, Elliott was signed to Elektra Records and was given her own record label, The Goldmind Inc.. Chairmen and chief executive officer (CEO) of Elektra at the time, Sylvia Rhone encouraged Elliott to embark in a solo career.[5] Recording sessions of the Supa Dupa Fly took place at the Master Sound Studios in Virginia Beach, Virginia.[7] The album was produced solely by Timbaland.[5]

The first single released from the album was "The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)".[8] As part of the promotional drive for her album, Elliott took part of the 1998 Lilith Fair tour; she became the first female rapper to perform at the event.[9] She also joined rapper Jay-Z's Rock the Mic tour.[9]

Musical content

Supa Dupa Fly brings together elements of hip hop, dance, R&B, electronic music, and soul.[10][11] Music critic Garry Mulholland described Timbaland's production as "eschewing samples for a bump 'n' grind electronica, strongly influenced by the digital rhythms of dancehall reggae, but rounder, fuller, fatter".[12] AllMusic described it as consisting of “lean, digital grooves [...] packed with unpredictable arrangements and stuttering rhythms that often resemble slowed-down drum'n'bass breakbeats."[10] Elliott's raps were described as “full of hilariously surreal free associations that fit the off-kilter sensibility of the music to a tee.”[10] According to author Mickey Hess, the album's lyrical content "reveals Elliott's complex, creative, and challenging discussion about womanhood; her demand for respect, respect for her personal voice and her desire for fulfilling intimacy with lovers and friends".[13] The album's opening track, "Busta's Intro", features rapper Busta Rhymes as a town crier warning of a "historical event about to unfold".[13] "The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)" contains a sample of Ann Peebles' 1973 song "I Can't Stand the Rain".[14] "Pass da Blunt" is partly based on the song "Pass the Dutchie" by Musical Youth. The track "Bite Our Style (Interlude)" samples the song "Morning Glory" by Jamiroquai.[15]

Upon its release, Supa Dupa Fly received acclaim among music critics. Writers lauded record producer Timbaland's production as unique and revolutionary. AllMusic called the album a “boundary-shattering postmodern masterpiece” whose “futuristic, nearly experimental style became the de facto sound of urban radio at the close of the millennium.”[10] Elliott's rapping, singing and songwriting also received much acclaim. The 2004 edition of The Rolling Stone Album Guide rated the album five out of five stars, noting that the avant-garde sound of the album "made Elliott and Timbaland the hottest writer/producer team around".[22] Mulholland called the album a "key prophecy of the dominant 21st century black pop", noting Elliott's ability to "avoid the whole east vs. west, playas vs. gangstas mess." He described Elliott's style as "everything the hip hop doctor ordered; a woman who could flip between aggression and romance, sex and nonsense, materialism and imagination, without batting one outrageously spidery eyelash".[12]

With the release of Supa Dupa Fly, Elliott became one of the most prominent female rappers.[25] The album is credited for redefining hip hop and R&B.[10] Steve Huey of AllMusic felt that the album was "arguably the most influential album ever released by a female hip-hop artist".[10] Spin magazine ranked the album at number nine on its Top 20 Albums of the Year.[13] In 1998, four out of five music critics from The New York Times ranked the album as one of their top ten favorite albums of 1997.[26] The album earned Elliott two Grammy Award nominations: Best Rap Album and Best Rap Solo Performance for "The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)".[13]

All tracks produced by Timbaland.

2. "Hit Em wit da Hee" (featuring Lil' Kim)

Elliott

Timothy Mosley

Kimberly Jones

Alicia Richards 4:19

3. "Sock It 2 Me" (featuring Da Brat)

Elliott

Mosley

William Hart

Thom Bell

Shawntae Harris 4:17

4. "The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)"

Elliott

Mosley

Ann Peebles

Bernard Miller

Don Bryant 4:11

5. "Beep Me 911" (featuring 702 & Magoo)

Elliott

Mosley

Melvin Barcliff 4:57

6. "They Don't Wanna Fuck wit Me" (featuring Timbaland)

Elliott

Mosley 3:18

7. "Pass da Blunt" (featuring Timbaland)

Elliott

Mosley

Jackie Mittoo

Lloyd Ferguson

Felix Headley Bennett

Huford Brown

Robbie Lyn

Leroy Sibbles

Fitzroy Simpson 3:17

8. "Bite Our Style (Interlude)"

Elliott

Mosley 0:43

9. "Friendly Skies" (featuring Ginuwine)

Elliott

Mosley 4:59

10. "Best Friends" (featuring Aaliyah)

Elliott

Mosley 4:07

11. "Don't Be Commin' (In My Face)"

Elliott

Mosley 4:11

12. "Izzy Izzy Ahh"

Elliott

Mosley 3:54

13. "Why You Hurt Me"

Elliott

Mosley

Eddie Floyd 4:31

14. "I'm Talkin'"

Elliott

Mosley 5:02

15. "Gettaway" (featuring Space and Nicole Wray)

Elliott

Mosley

Tracey Selden

Lashone Siplin 4:25

16. "Busta's Outro" (featuring Busta Rhymes)

Smith

Mosley 1:38

17. "Missy's Finale" Elliott 0:24

Personnel

Credits for Supa Dupa Fly adapted from AllMusic.[31]

702 – vocals, performer

Aaliyah – vocals, performer

Kwaku Alston – photography

Starr Foundation/Romon Yang - Art Direction

Gregory Burke – design

Busta Rhymes – vocals, rap, performer

Richard Clark – assistant engineer

Nicole - vocals, performer

Drew Coleman – assistant engineer

Da Brat – vocals, performer

Jimmy Douglas – engineer, audio mixing

Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott – vocals, rap, executive producer

Ginuwine – vocals, performer

Lil' Kim – performer

Magoo – rap

Bill Pettaway – bass, guitar

Herb Powers – mastering

Timbaland – vocals, producer, performer, executive producer, mixing

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/10/20/the-new-negro

Missy Elliott’s Hip-Hop

I first met Missy Elliott last June, in the waiting room at WPGC-FM, a D.C. soul station. She was there to promote the release of her début solo album, “Supa Dupa Fly,” and, in characteristic Missy Elliott fashion, she had dressed for the occasion—in a red-and-yellow baseball jersey, bright-yellow vinyl overalls, a bright-yellow vinyl jacket, and brown Timberland boots. Her hair was styled in crisp finger waves close to her head, like tiny black ribbons, and her fingernails, two inches long, were varnished white. But there was no publicist or receptionist to greet her. On the wall above the reception desk were a number of shabby, poster-size black-and-white photographs of the station’s disk jockeys, their hair and teeth celebrity-bright, which did nothing to dispel the forlorn atmosphere. She looked around and reduced the dim room and the station’s lack of amenities to a weary expletive: “Damn.”

Missy had arrived with three people in tow: her cousin Malik, who is as tall and lanky as Missy is short and round; Rene McLean, a rap promoter from the Elektra Entertainment Group; and Keisha, a pretty young black woman who is a third of the girl group Total. As is often the case in Missy’s professional circle, exactly who was promoting whom wasn’t initially clear.

WPGC was Missy’s final guest appearance that day; earlier, she had publicized her album at three record stores and another radio station in the Washington area, and she had been greeted in all those places with considerable fanfare. (“Yo, it was dope,” Keisha said, chewing gum as she smiled her most seductive girl-group smile.) In an effort to generate a little of that excitement at WPGC, Missy dispatched Rene to find Tigger, the host of the program she was supposed to appear on. Then she announced that Keisha would be interviewed on Tigger’s show, too: less airtime for “Supa Dupa Fly,” maybe, but more exposure for another Missy project: she had co-produced and co-written a number of tracks on Total’s yet-to-be-released album.

Malik returned with Tigger, and in short order Missy, sitting opposite Keisha in the control booth, was introducing her to WPGC’s listening audience. She then took calls from her fans—whom she addressed as Baby, Boo, or Go-Go Head—while autographing her way through a stack of eight-by-ten black-and-white glossies. Even four months ago—before she appeared on David Letterman, before the MTV Video Music Awards, before her record went gold—Missy’s unorthodox blend of personal confidence, professional generosity, and entrepreneurial spirit were in ample evidence. After signing off, Missy talked about the lyrics she’d written for her song “The Rain,” which was already on its way to becoming a hit: “One minute I’m talking about weed, the next minute I’m talking about a man—like that. Closer to life and closer to how my mind works.” She walked into a WPGC conference room and sat down, her oversized yellow overalls ballooning up around her. “I don’t want to be oh-so-brag-about-it, but ‘The Rain’ is hot,” she said with a shy laugh, her almond-shaped eyes closing up tight. Then she made the comment that would become her mantra in the coming weeks: “We give our music a futuristic feel. I don’t make music or videos for 1997—I do it for the year 2000.”

In the nineteen-sixties, when Diana Ross was with the Supremes, she was a superb New Negro. When she sang, she did so much more than just sing: she shrugged her shoulders, bugged her eyes, and bopped her big head on her skinny neck. When she sang “Where Did Our Love Go?” she looked as though she were having a very controlled, elegant freak-out. Then, in the seventies, the Pointer Sisters clunked around in Andrews Sisters wedgies and Ruby Keeler shorts, while waving little American flags and singing riffs from “Swanee” with a great deal of energy and irony. In the eighties, the disco diva Grace Jones not only intoned that she could feel like a woman while “looking like a man” but also, in her extended video “One Man Show,” resurrected Dietrich’s “Blonde Venus” ape suit, with its racist overtones. In 1997, Missy Elliott is the New Negro of hip-hop.

“Women in rap, it’s the same as it ever was—they come and go,” Sharee, a New York d.j., told me. “Back in the day, in the nineteen-eighties, they were cute and sexy. Now they’re cute and sexy and mad about something. They don’t last, because they work one gimmick—their sex appeal—and that doesn’t last long. Think Marilyn Monroe talking in rhyme, and you have a pretty good idea of the way most female rappers go.” But Missy Elliott has not only avoided the prevailing stereotypes of the music-video industry; she has spent the last few months bringing the industry around to her style of dance, costume, and song. “She slowed down rap—she took chances,” Jac Benson, a senior producer at MTV says. “She opened the door for other sounds.” As for Missy’s lyrics, they are about her internal world—not the material world of money, jewels, and men—and in her video she has managed to catapult herself beyond the clichéd horny-boy images of girls in Jacuzzis chugalugging champagne. Instead, she has capitalized on the hip aesthetic that Sly Stone founded in the late nineteen-sixties, when he developed a persona that managed to retain a hard-edged black sound without making white listeners feel hopelessly unhip. Missy told me that she wants her work to show “where black folks are from, and where we’re going.”

In the video “The Rain,” her hair, which fits her like a cap, is reminiscent of the marcelled coiffure that Duke Ellington sported in the forties and fifties. In some shots, she wears an inflated black patent-leather suit and black sunglasses attached to a rhinestone headpiece—a look that the Whitney Museum curator Thelma Golden has described as “cyber mammy.” In another sequence, she moves toward the camera wearing a lime-green outfit and oversized yellow-framed glasses, jerking her arms up and down and proclaiming, “I’m supa dupa fly!” Missy’s little dance looks like an accelerated version of Walter Brennan’s “dead bee” hop-and-skip walk in “To Have and Have Not.” In another shot, her lips and eyes are “morphed,” or enlarged. Features once made grotesque by racist caricaturists are celebrated by this New Negro: exaggerations of physiognomy are an aspect of her style.

In another “Rain” clip, Missy is chanting—her warm, rich voice layered against the song’s background track, the soul classic “I Can’t Stand the Rain”—“I feel the wind / Five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten / Nine, ten / Begin / I sit on hills like Lauryn until the rain starts comin’ down, pourin’.” Sitting on a near-psychedelic grassy knoll and running her fingers through a straight-haired wig she’s wearing, she’s a caricature of the Little Bo-Peep white girl. “We wanted to make fun of the ways record companies try to make black women look white,” Missy has said. “Fake hair, fake music.”

Missy conceived of “The Rain” video together with the black music-video director Hype Williams, who has also directed the rap stars Busta Rhymes and the late Tupac Shakur. Both Missy and Williams were aware that for many viewers the video would provide a way into her music. “Videos are the most valuable tool for selling songs,” says Gina Harrell, who heads Elektra’s video-production department. “Until they saw the video, radio programmers didn’t understand ‘The Rain.’ She taught people how to move to the track. And Hype was able to pull out the core of Missy—the performance artist.” It was only after radio programmers and the general public saw Missy dancing that her position as a New Negro icon was established. After all, the idea that “it’s a ten because you can dance to it” didn’t go out with “American Bandstand.” “The Rain” has inspired a score of imitations since its release—some of them directed by Hype Williams himself. “I wanted the video to look avant-garde, so white people could get into it, too,” Missy told me. “And if I lose cool points with other rappers ’cause I don’t want my sound and look to be about one thing, then I lose cool points.”

Melissa Elliot was born in Portsmouth, Virginia, in 1971, two years before “I Can’t Stand the Rain” was first recorded and released. As an only child, Missy, as she was called by her family, amused herself by lining up her dolls—“Baby Alive, G.I. Joe, whatever”—and singing to them. Her parents’ marriage was an unhappy one, and when Missy was fourteen they separated. She and her mother have lived together in Portsmouth ever since.

A solitary and industrious teen-ager, she helped form a singing group with three other neighborhood girls. The group’s first name was Fay Z; then it became Sista. “Missy always wanted to be up there,” her mother, who works as a dispatcher at an electric company, recalls. “As a little girl, she would ask me to bring home stamps, for all these letters she was writing. The letters would be returned, and I’d see that she’d written to Diana Ross, and whatnot.”

Sista began performing at local talent shows and local colleges, and in 1992 attracted the attention of Devante, a member of the popular singing group Jodeci, by waylaying him at a concert. When Devante signed Sista (“We had long-ass weaves, we was a mess,” Missy recalls), Missy was twenty. She and another neighborhood friend, Tim Mosley, who went by the name of Timbaland, had written many of the songs that the group performed. Sista eventually dissolved, but Timbaland and Missy are still partners.

Their songwriting process has been the same for years: first, they create the basic tracks (often incorporating samples from soul classics like “Pass the Dutchie”). “Then I’ll sit down,” Missy says. “He may go to the movies, the mall, or something. And I sing the whole song, background and all.” The work grows out of a variety of musical genres—reggae, rap, R. & B. ballads—but its basis and primary influence is soul music, ranging from Rick James’s “Super Freak” to black-exploitation-movie soundtracks like Curtis Mayfield’s “Superfly.” By 1995, Missy and Timbaland were writing songs for the hottest acts in R. & B., from Aaliyah to Ginuwine, and were on their way to becoming a latter-day Ashford and Simpson.

“When people say the music business, they mean the producer business,” Jac Benson told me. “Producers, not artists, are the ones who really get to control an artist’s over-all sound and message.” And Missy recognized that very early. Unlike most performers, who first struggle to succeed as solo artists before they turn to producing, Missy did the reverse. Her experience with Devante turned out to be a bad one—Sista had made a record and then waited for years, in vain, for it to be released—and she was determined not to repeat it. “I didn’t want to just be an artist and let someone else have all that control over me,” she said. “I knew I would have to produce.”

In fact, Missy’s potential as a solo artist and video presence didn’t become evident until last year, when her now signature “hee haw” rap for Gina Thompson’s remix of “The Things You Do” was showcased in the video. “Gina’s song was the ice-cream sundae,” the hip-hop impresario Fab Five Freddy told me. “Missy’s rap was the cherry on top.” In contrast to the funky bubblegum ballads she’d written for groups like SWV and 702, Missy’s raps were sharp and strong: the woman was always saying what she wanted, and when and where she wanted it. And Missy’s visual impact proved to be as captivating as it was unexpected. “She’s a full-figured black woman,” Freddy continued, “and, let’s face it—a lot of black women look like her. She has Southern sophistication, a country elegance.” But there was also an iconic quality to Missy on video from the beginning; Freddy described her as “the twenty-first-century incarnation of Aunt Jemima; it feels like she’s putting the whole house in order.”

After the Thompson video came out, rap fans began asking for the “hee-hee haw-haw” girl. Missy says that she was approached by companies from Arista Records to Motown, but that they wanted to sign her only as an artist, and she refused. Merlin Bobb and Sylvia Rhone, two senior executives at Elektra, agreed to give her more. “We wanted to set her up in a small situation where she could develop her songwriting and producing abilities,” Bobb explains, “whereas other companies wanted to sign her as an artist and make some fast money.” He adds, “Missy was shocked when she understood that we were interested in her business sense.” In the summer of 1996, Elektra agreed to subsidize a small label called Gold Mind Records, which Missy now oversees. Bobb says that when Missy first joined Elektra she was writing songs for other artists, but that she soon grew confident enough to begin writing songs for herself. In the spring of 1997, she and Timbaland recorded the music and Missy’s vocals for “Supa Dupa Fly” in a week.

On July 22nd, the video of “The Rain” was nominated for three MTV Video Music Awards: Best Rap Video, Best Direction in a Video, and Breakthrough Video. The next day, “Supa Dupa Fly” went gold—No. 3 on Billboard’s pop chart, and No. 1 on its R. & B. chart—thereby reinforcing Elektra’s belief in Missy as a strong, marketable artist. By mid-August, articles had appeared in the Times, the Washington Post, and the business section of the Los Angeles Times. By August 20th, Missy had begun working on a new video of her second single, “Sock It 2 Me,” with Hype Williams.

When I saw Missy at the filming of the video, in a cavernous hangar in Long Island City, she was wearing red superhero boots, white tights, and red Pac-Man arms, and she had a big red “M” emblazoned on her chest: the inspiration for this video, which also featured Da Brat and Lil’ Kim, was Japanese superhero animation. This time, Missy was not only the video’s main attraction but also its co-producer. “Sock It 2 Me” had a nine-hundred-thousand-dollar budget, half of which Missy was personally responsible for—a budget that she hoped would make the video harder to rip off visually. (“If people gonna copy me this time, they gonna have to come out of their pockets,” Missy says.) She is unlike many performers in that her wit and her sense of character go hand in hand with her marketing savvy: her rap on SWV’s “Tonight” begins, “Me and Timbaland / We got the hits from here to overseas for SWV.”

Throughout the day, Missy would look at the playbacks—alone, and then with whoever else wanted to watch. (At one point, the stylist for the shoot, June Ambrose, walked by. Glancing at Missy’s image on the flickering screen, she remarked, “She has lost her mind, and that’s a good thing.”) Missy consulted with Timbaland several times about her performance. She was not concerned with how she looked; rather, she wanted to know whether “Sock It 2 Me” was a suitable follow-up to what she had done before; she wondered out loud if people could “really understand where this Missy thing is going.”

Sylvia Rhone, for one, sees the “Sock It 2 Me” video going in the direction of television: “No one’s really used that Japanimation kind of thing, and I want to take this video and try to sell the concept of these characters—which are played by Missy, Lil’ Kim, and Brat—and do a real special cartoon. Black folks haven’t moved into that genre.”

Rhone was particularly pleased about the coverage that Missy received in the L.A. Times. “I want white America, which is scared of hip-hop artists, to see that some of us are real businesspeople, who command major dollars and a major consumer base, and have more vision than just doing a rap record.” Rhone thinks that Missy’s easygoing manner can be misleading. “If you ran into Missy, you would say, ‘This is a ghetto girl with ghetto curls,’ ” she told me. “Underneath the ‘hee-hee haw-haw,’ she’s one of the sharpest businesswomen I’ve ever come up against.”

And, if Missy wants greater longevity than is usually accorded a rap star, writing and producing under her own label, Gold Mind, may provide it. “I feel like, O.K., if I can make it as a singer, then let me try rapping,” Missy told me. “If I can make it as a rapper, then let me try writing. All right? If I make it as a rap singer and writer, then why not try to produce? I don’t feel limited in any way. There’s that saying ‘God gave you talent, and if you don’t use it He’ll take it away from you.’ And I always said, ‘I don’t want God to come down and take my talents away.’ So, by using all these talents and being successful in all of them, I’ve always got something to fall back on.”

On September 3rd, the night of the rehearsal for the MTV Video Music Awards, Missy Elliott arrived at Radio City Music Hall to perform her rap on Lil’ Kim’s single “Not Tonight,” along with the radio personality Angie Martinez; Left Eye, from TLC; and Da Brat. As usual, she was dressed to thrill, and, as usual, she looked like no one else there. In an industry where, as Missy says, “you either gotta be light-skinned or have long hair” to satisfy a teen-age boy’s video idea of a proper “vide-ho,” Missy Elliott has managed to be something else altogether. Before her “Supa Dupa Fly” success, she had the feeling that people “might not like me hopping around,” she recalls. “You wouldn’t see me in one of those model magazines unless it was, like, Healthy Woman. But I’m cool.”

Lil’ Kim’s number was to have an Egyptian theme: Lil’ Kim, Left Eye, and Angie would be dressed in Nefertiti-like costumes; Da Brat would be dressed as a Roman gladiator. They all assembled on the stage and, silhouetted against a big-screen projection of a pyramid, began working out various moves with the choreographer. Unlike the other participants, Missy would be entering the act from the audience, dressed as herself—as though her fellow-entertainers were her bitches. While the women gyrated and gestured onstage, Missy sat with her cousin Malik, drinking a large bottle of soda pop and looking apprehensive. This would be her first live television performance. It was a far cry from singing in hair extensions and Jordache jeans at the local high school in Portsmouth. Billy B., Missy’s makeup person, had been eavesdropping when her mother beeped her a few days earlier: “I could hear Missy say, ‘Now, Ma, please don’t come to the awards. I’ll be too nervous to perform—it’s the white people’s awards, Ma. Very important.’ ”

But when it came time for Missy to walk the length of the aisle doing her little Walter Brennan dance, her nervousness seemed to vanish. A number of MTV staff members, publicists, and managers representing other artists moved to seats at the front of the stage in order to have a clear view. Hop-skipping down the aisle toward her sister rappers, Missy carried a mike in one hand and made flapping gestures with her other, saying, “Yo, yo, Kim, you not gonna get me on this song just singing hooks. What I look like—Patti LaBelle or something?” Then Lil’ Kim giggled her peroxide giggle as Missy engulfed her in a tight embrace.

Each time they ran through Lil’ Kim’s number, Missy performed her part of the song differently. Sometimes she added an extra “yo,” or she made a little “tiki tiki” sound between the “yo”s, like an urban voodoo priest bent over a cauldron. One time when she said, “Oh, what a night,” at the song’s conclusion, she conveyed a certain flirtatiousness; another time she conveyed boredom. Unlike the majority of rappers, who try to approximate in their live performances the exact sounds and movements they’ve used in their videos for easy audience identification, Missy approaches rapping the way jazz musicians approach jazz—as an improvisational musical form. It was only after the rehearsal was over—when the others had wandered off and she stood alone on that vast and unfamiliar stage, blowing kisses and mouthing “Thank you”s to a nonexistent audience—that one remembered how astonishing it was that such a newcomer had performed there in the first place.

A week later, on September 10th, Missy was in a dressing room on the sixth floor of the Ed Sullivan Theatre, at Broadway and Fifty-third Street, getting ready to perform “The Rain” on the “Late Show with David Letterman.” Missy had never been on a late-night show before, and, while the invitation was a welcome indication of her recent crossover success, she did not have a clear idea of who, precisely, Letterman was. “I never catch the show,” she said. “What does he do up there?”

That afternoon, during Missy’s pre-taping rehearsal, Letterman’s technical staff had been plagued by a similar question: What, exactly, were Missy and her entourage planning to do up there? She was singing with a seven-piece band, but there were also two dancers, two more rappers, and two backup singers in attendance. In addition, Ann Peebles, the woman who first made “I Can’t Stand the Rain” famous, was making a guest appearance with Missy. “They didn’t know where to put the camera,” Missy’s manager, Louise C. West, recalled later.

Fifteen minutes before Missy was to appear in front of a live studio audience, Anne Kristoff, her publicist, and Billy B. were waiting outside the performer’s dressing room. There was consternation over the fact that Missy hadn’t announced a final plan for her performance, and Billy B. was upset with his client for not giving him the time he needed to make her up. (“I was promised an hour to do her face,” he complained, to no one in particular. “Missy’s face is my face. I want to be proud of it.”)

Then Sylvia Rhone stepped off the elevator with Merlyn Bobb, and Rhone asked how Missy was and what time she was going on. “Now,” replied a young woman who was passing by in the narrow hall. Right behind her was Missy herself, wearing outsized red leather trousers, a large white T-shirt, and a gold pendant depicting an Afro’d woman in silhouette. A sleeveless red leather basketball jersey had the word “Supa” written on the front and a big purple leather fly stitched on the back. She was trailed by Malik, two dancers in purple trousers and tops, and the singers Magoo and Timbaland. Everyone else stepped into line behind them, followed Missy into the elevator, and disappeared, like circus performers pouring into a tiny joke car.

Downstairs, the non-performing members of Missy’s entourage sat in the greenroom watching as Letterman introduced the number while holding Missy’s CD upside down. The camera closed in on the face of Ann Peebles singing, “Missy, you can’t stand the rain,” while Missy performed her distinctive shimmy and belted out the lyrics “Beep, beep, who got the keys to the jeep, vroom!” Rhone was watching the monitor in the greenroom, and her eyes filled with tears. “She’s got it, she’s got it!” she chanted.

At the end of the song, David Letterman kissed Missy’s hand. Suddenly, the woman who only moments before had been skating from one side of the stage to the other and making cat’s eyes at the audience became modest and subdued. “You Missy people come back!” Letterman called after her as she and her fellow-performers left the stage. Minutes later, Missy was climbing into a black stretch limousine—with Magoo, Malik, and Louise in tow—that had been waiting outside the theatre. Clutching her cell phone, she called her mother: “Yo, Ma, watch me tonight on David Letterman. What channel is it on, y’all? Yeah, Ma, Channel 4.”

In the coming months, Missy will be a presenter at the 1997 MTV Europe Music Awards. She will tour England, France, Holland, and Germany to promote “Supa Dupa Fly.” But she will also be launching Nicole Ray, a young singer from her home town, on Gold Mind, and producing four songs on the Total album. At twenty-five, after less than two years as a producer with Elektra, she’s already sounding like an old hand (“I like young people—not to say that I block old people out. It’s just that you can develop young people”). It also may be time, Missy thinks, to break into the movies. “I don’t want big scenes at first,” she explained to me recently. “I want to work my way up. Sometimes, when you get a heavy role, you can’t deliver, and people are so jealous, they’d be like, ‘Yo, Missy can’t act.’ But if it’s something small people will say, ‘Yo, Missy is tight.’ ”

After the Letterman taping, as the limousine moved through the blue twilight, the driver asked Missy how the show had gone. When he heard that Letterman had kissed her hand, he observed that that was a sign of great respect—or props, as he called it. “That means Letterman’s a European,” he explained. “Those Europeans, they can give it up to a Negro; Missy, one day soon they gonna give you all your props.” ♦

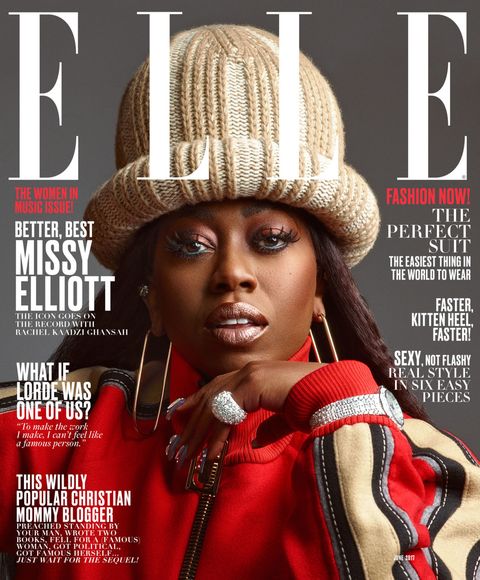

https://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a44891/missy-elliott-june-2017-elle-cover-story/

Her Eyes Were Watching the Stars: How Missy Elliott Became an Icon

She's been making ahead-of-the-curve music and mind-bending videos for 20 years—and that's no fluke. Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah goes behind the curtain with the ultraprivate creative genius.

This article appears in the June 2017 issue of ELLE, on newsstands now.

At the photo shoot, the accoutrements of being her precede her. A tray of acrylic nails and an almost-empty bottle of professional-grade nail polish remover are carried by Bernadette Thompson, the Takashi Murakami of manicurists. A tall, strong-looking man walks around distractedly, wheeling a Louis Vuitton duffel bag that is smaller than his forearm; from time to time, he spins it in a wide circle out of boredom. Jewels—gold chokers, hoop earrings, and rings in a velvet-lined box—are attended to by a thin young man wearing a black Balenciaga fitted cap and high-top Nikes. There's a bottle of jewelry cleaner harnessed to his chest and a chain of styling clips attached to his hoodie strings; he looks listless, like he has given his body over to the task. On the table, someone has set down two Kangol hats, one tan, one black: fuzzy, wearable homages to the golden era of hip-hop. They sit there like low-key crowns.

I take a seat out of sight, behind Misa Hylton, the stylist who is the reason people let their pants sag and their Calvins show. Dressed like a ballet dancer from Brixton—or is it Ginza—in a baggy gray sweatshirt and a sheer, tutu-ish white skirt, she sucks on a lollipop, not saying much but taking everything in. When Missy Elliott needs help pulling off her shoe, Misa rushes in to steady her. I recognize the intimacy of it; it's like having your mother or your sister oil your hair. They share a joke; Missy laughs. Misa walks back to her seat, and because they seemed so comfortable, others start to crowd around to look. I still can't see anything from my seat, but I can hear Missy ask something so softly that it has to be repeated and shouted back: "Everybody move back and give her some privacy. Please." Then a large white scrim is stretched out that totally eclipses her from our view. And she turns into a silhouette behind the screen.

What does it mean to be a shy black woman performer in a world where black women are never thought to be shy? Before I went to meet her, I had read articles that decided it just wasn't possible that Missy Elliott is shy. The Guardian wrote that "scary diva is what you expect"; they do not explain why they expected her to be scary, they just say it. In the same way that no one explains what I should expect when I'm told over and over again that Missy Elliott is very shy, without anyone offering a larger understanding of what it might mean. Would she need to be coaxed to open up? Would she not answer my questions? At the shoot, the photographer yells out to her: "Don't be shy—I love it! Let's turn the music up."

Although I got the sense that others were fretful about how this "shyness" would manifest itself in our conversation, after I watched videos of her performing in concert, I was not.

What no one seems to realize is that Missy, like most shy black girls, had long ago been forced to master a certain skill: to hammer down her shyness, along with any fear, to some low, unseen place deep inside of herself, and keep it there until she could step over it, again, again, again.

From the moment I walked on the set, I assumed that Missy Elliott was someone who had this skill, that her ability to rise was ingrained, and I wasn't there for long before we are all watching just that: Missy the Performer—exuberant, high-stepping, arms up in the air, roof-raising, and hair whipping—taking over the monitors and smiling like a woman who has released five platinum albums, possesses four Grammys, and has sold 30 million records and knows very well how to overcome being called scary or feeling shy.

When Missy Elliott dropped her debut album exactly 20 years ago, she altered the spectrum and the range of hip-hop. She made it wild and hyperdimensional. Suddenly, we could all see and hear more. The first rap album I ever purchased was Supa Dupa Fly. And the most important video in the story of my life is "The Rain." On "The Rain," she raps about what still sounds like a perfect day: some light precipitation that clears, smoking some weed, driving to the beach, and dumping an undeserving man. It's a simple enough narrative, but she made it sound strange and wonderful. This was what hip-hop would sound like if it were conceived inside of the calyx of an African violet, unfurling and wet.

I remember seeing that video for the first time in Atlanta at my

cousin's one summer in 1997. I was 16. We didn't have cable at our

house, so my sister and I stood in his basement and stared at the screen

as a woman in a bubble suit that seemed to be filled with equal parts

helium and black cool wobbled and bopped. These were lyrics we got

intuitively even though we usually didn't understand a word. The

vertiginous beats, the cacophony of thunderclaps, and her movements—both

fluid and staccato—put me on the floor. I lay there, sweating in that

Southern humidity, wondering what I had just seen.

I spent those first early summer weeks in Atlanta fucking up the norms of my cousin's neighborhood, a place where the social codes seemed to be as thick and intricate as in Downton Abbey or any E. M. Forster novel, but with sweet tea and beepers. I was greedy to fit in and also aware I never would. We had been there for two weeks when I saw her, sitting on her "Hill's like Lauryn / Until the rain starts, comin' down, pourin'." Years later, she would put it all into words and boast, "For those of you who hated / You only made us more creative." The double entendres, the hair flipping, the irreverent eye rolls, the smirks, the wink, and the symbolic power of putting on an ink-colored balloon suit and becoming blacker, larger, lovelier, and gigantic with daring weren't lost on me.

Pharrell Williams, who has known and worked with Missy for almost 25 years, calls me on her behalf one Sunday afternoon. He talks about her properly, like she is a sonic theory, a leader, and a woman he adores as a creative liberator. "We came up in a time where we were always told no. Where we were always placed in a box. And she defied it. Over and over again. She defied the physics that were dictated to us. She ignored the gravity of standards and prejudices and stereotypes. She ignored that gravity."

Missy Elliott is in constant metamorphosis, but there is still something about her that feels like your homegirl—if your homegirl had a fleet of cars that include a Rolls-Royce, two Lamborghinis, a Porsche 911, a Ferrari 599, an Aston Martin Vanquish, a Spyker, a Range Rover, an Escalade, and a Jeep Cherokee that she says she prefers over all of them. Missy owns enough houses to start a small village (she splits her time between Florida, Virginia, New Jersey, and Los Angeles), but she tells me that she just feels lucky not to have to pay rent and to be financially secure. These are the rewards of being a 45-year-old humble rapper who is still very much in demand at a time when other rappers her age are trending down.

But what makes her iconic is not the numbers; it is what she empowers in others. Missy was always aware of her worth, her real worth—not the fluff or the proxies for currency and confidence that most people depend on. She always expressed what so many of us feel on the inside but have no model for how to display. Her refusal to discuss her personal life has allowed her to deftly deflect any inquiries about her real life toward her surreal life: The one she inhabits with her many costumes and her various personalities. In almost every video, Missy Elliott is a different character (a black Barbie in "Beep Me 911"; a floss-fluorescent, bald-headed creature in "She's a Bitch"; a black Beatrix Kiddo at war with a rival gang that's driving the Pussy Wagon in "I'm Really Hot"). This is the stuff that makes her Missy Elliott, the legend. It is a demand for privacy, but also a sign of wisdom. She's kept our eyes on the prize. She seemed to know early on that the only thing that matters is the work, and it can look fun. But ultimately, the relentlessness and the far-reachingness of it are what have kept her in orbit.

Missy Elliott is a creator's creator. They say that, before he died, Michael Jackson asked her to teach him how to rap. The Dirty Projectors work below a triptych of the people they consider to be the all-time greats: Joni Mitchell, Missy Elliott, and Beethoven. Tyler, the Creator once told GQ that in his mind, alongside Elizabeth Taylor, Missy Elliott was one of the most stylish women ever to exist. "I'm not even talking about her normal dressing. Just the swag that she had in her videos. She made a fucking plastic bag look awesome," he said. Björk, Herbie Hancock, Debbie Harry, Lil Wayne, and Solange Knowles cite her as an inspiration. And Patti LaBelle has thanked her for bringing R&B back. "Missy's so amazing," Thom Yorke of Radiohead once said, that "she makes me want to spit."

While other rappers were adversarial, making you feel broke, or uncool, or backed up against despair, Missy was inviting us to join her party. Others insulted us for listening, told us about what we didn't have, didn't own, and couldn't brag about, whereas Missy said, Forget who you are, forget what you heard, and come dance with me. In Missy Elliott's songs, bodies jiggle, jangle, they sweat, they drip, they drop, they are invested in the beat. In the early eighties, Michael Jackson gave an interview in which he told the interviewer that above all, he liked "to really forget." What feels good about Missy's music is that for four or six minutes, your body is helmed by her control of the beat; you can "really forget" your own life because there is so much to pay attention to in hers. In the "Pass That Dutch" video, she runs through a primer of black footwork in a cornfield while instructing us to work our legs. In "Lose Control," she samples an old electro song by Cybotron, turning things frenetic, until they sound double-timed and fast enough to fly off the handle. In "Slide," a track that feels enormous, a booming cut-time march, she uses a simple rhyme scheme and her background vocals to remind us to work the waist and keep it slippery. "Slide, slide, dip, shake / Move it all around," she purrs. Missy raps from within the rhythm—she doesn't work against it or with it, she doesn't ride it, she becomes it. Words zigzag and stretch to match time signatures. She can speed them up and slow them down; she organizes her harmonies like string sections; and if she can't do it alone, she'll invite someone else—Ludacris, Jay Z, or Tweet—to join her.

What I realized when Missy and I finally sat down to talk is that Missy is communal and sentimental in a way that hip-hop at times denies itself. She tells me about a last-minute sleepover party that she had with Mary J. Blige, Queen Latifah, Misa Hylton, and Lil' Kim in Virginia for her birthday a few years ago. It touched her that they could be "real friends, not just friends for the camera." She seems far too delicate to be asked about Aaliyah, the singer who died in a plane crash in 2001, who was her best friend, collaborator, and "little sister." Missy mourns and pours visual libation to Aaliyah in most of her videos and many of her songs.

Missy Elliott's work doesn't deny death, or poverty, or bad times, but it pushes for recovery. In her most recent single, "I'm Better (feat. Lamb)," which was released in January, the chorus circles around and gets repeated with a robotic flow: "I'm better, I'm better, I'm better / It's another day, another chance / I wake up, I wanna dance / So as long as I got my friends /...I'm better, I'm better, I'm better." This is not a boast from her to her fans; it is a mantra to them from her, even if there is a self-help quality to it. What matters more is that it feels determined, and that is what her fans depend on her to provide—the good news.

She was born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Patricia, a dispatcher for the power company, and Ronnie Elliott, a former Marine. She was their only child, and her parents named her Melissa Arnette Elliott. Missy told me that when the other kids in her class were asked what they wanted to be, they changed their minds every other week. "It would come to me, and I would be like, 'I'm going to be a superstar!' And the whole class would bust out laughing. But every Friday I would say the same thing. And I would watch them change to different things. Now the doctor is going to be a fireman, but still, when it came to me, I wanted to be a superstar. They thought I was the class clown. But I was like, 'I'm going to be a superstar.' So when I would get in my room, it was like, if y'all don't see it, I'm going to create it myself."

The black sculptor Augusta Savage once said of her father that she believed his violence was the result of him trying to whip the "art out of her." The expression of her artistry, her voice being utilized outside of him, was an affront to his masculinity. So he beat her and tried to break her down. Missy's father beat her mother almost every single day. He dislocated her arms; he berated her. He hit Missy only once, but the violence and instability in her life were relentless. She was eight when an older boy, a family member, saw her vulnerability and preyed upon it—he began molesting her in the afternoons.

Unable to stop her father, put off her molester, or save her mother, Missy shut her door. She turned her room into something that she describes as her Wonderland. This was where she would write fan letters to her favorite singers, the Jacksons, with the unexpressed hope that they would appear, see how musically gifted she was, and come to her rescue. The Hype Williams–directed videos that would define her sensibilities decades later were conceived in spirit in this workshop. Here, she practiced singing along to the radio or to the records her family gave her. And before each performance, she twisted her doll babies' arms up, so they were frozen, forever applauding her.

There are two ways to look at a story like Missy Elliott's. The first is within the context of that little girl now. All grown up, in her mid-forties, talking with me while wearing four diamonds in her ears that are bigger than my eyes. This is the woman who will tell you matter-of-factly, "I believe that I spoke it all into existence," and can explain year by year how she actualized her vision, but gives glory to God that she did. The other way to see this enormous dream is as one that was steeped both in pragmatism and what could not be helped: fate.

Although she does not call it this, Missy Elliott believes in the technology of the self, the idea that we can alter our lives by what we create and transmute, and in doing so, we can become invincible. For her, black innovation, black America's ability to overcome all odds and create, are a kind of passed-along technology. "We are survivors, and once we know that, we are unstoppable," she tells me one evening, as the sun makes it look like there are long, Dalí-like threads attached to her sequined sneakers. "I always said I wouldn't be no other color, because if there's one thing about us, we never really had, but we know how to—we know how to survive."

Missy survived abject poverty and years of abuse by tucking herself into sound. She was young, but when she listened to music, she found it impossible to be casual about it. Instead, she immersed herself in the process; she became the song's student. From her father, she learned to listen to the Temptations and Marvin Gaye. "I remember when 'Sexual Healing' came out. It made me listen to a record like that and think of how to do records like 'Pussy don't fail me now,' " she said, quoting her song "Pussycat." "I was trying to find creative ways of doing stuff.… And my mother had the gospel side, where I sat and studied their harmonies."

When she wasn't studying, she practiced. Missy Elliott had no Joe Jackson. She was no man's babe in the woods. She was self-actualized, self-realized, self-taught. There was no father to her style, but she had many mothers and sisters: Queen Latifah, Donna Summer, and Grace Jones. By the time she reached high school, Missy had started cutting class to invite friends over to rehearse in her living room, and her once-high grades plummeted. All of this alarmed her mother, who'd packed up a moving truck after her father had left for work one day; the two were living on their own. Her mother knew Missy was intelligent and just wanted her daughter to do the right thing, not realizing yet that for her daughter, music wasn't a sign of delinquency, but her path toward the only future she could envision for herself.

We were discussing her rocky years in school, during which she was identified by her school district as having both a "genius" IQ and being in extreme danger of failing every subject, when Missy asked me if I had ever heard of Poe.

"You know Poe?" she asked me, with an urgency that caught me off guard. "The Raven?" she added, smiling to conceal her slight impatience.

"Edgar Allan Poe?" I asked.

"Yes, so I studied, locked down—cause I knew I could do it…and when I had to do The Raven, I turned it into a rap, had one of my friends beatbox. I turned it into a rap! Got an A!"

"Are you big poetry person?" I asked her, since hip-hop is black America's repurposing of the poem.

"Uh, well… I wouldn't say that necessarily," she said, laughing. Then she stopped to think, and she got reflective. "You know, maybe I did like it. Because I murked that. I murked that."

It was around then, in high school, when her friend Magoo connected her with Timbaland and Pharrell Williams. Timbaland, she said, "had a little Yamaha keyboard, and Tim's hands are humongous. He was able to take the claps, the little dog sounds, and make beats with it. Then I just started rapping and singing over him playing with the Yamaha. Tim was very quiet. Pharrell was way on planet Mars. And, you know, I was just whatever. I was kind of crazy. But for whatever reason, we all understood each other."

The geography of Virginia—Southern, hanging off the edge of the East Coast—also inadvertently fortified their sound. They had very little access to what was trending, and it set them free to experiment and make music from what they had. "We got everything so late," she recalled, "it also allowed us to be different because we didn't hear. I will never forget when I first met Pharrell, even being from Virginia, he always was so different. I remember him coming into the studio, and he had some jeans on, and he had the cuffs where they came all the way up to his knees! And I had never seen cuffs that big in my life! And I was like, 'What part of Virginia he from?' "

At the time, Pharrell and Timbaland were in a group called Surrounded by Idiots, and Missy had an all-female rap group called Fayze. When Fayze found themselves in contact with the road manager for Jodeci, who at the time were the biggest force in R&B music, Missy devised an elaborate plan to audition for the group in outfits that matched the ones that Jodeci was famous for. Missy had never performed for anyone this famous before, but she knew what people like James Brown and Tina Turner had done. She took that workhorse approach and told the other girls, "I will need y'all to kick a leg up and put that cane on the floor!" It worked: Fayze soon had a record deal and an invitation to join Jodeci at their house in New Jersey.

Alice Walker once asked in her essay "In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens": "How was the creativity of the black woman kept alive, year after year and century after century, when for most of the years black people have been in America, it was a punishable crime for a black person to read or write?" Imagine the discouragement, the slights, and the drudgery that were directed toward these women when they, too, contained art. "Listen to the voices of Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Roberta Flack, and Aretha Franklin, among others, and imagine those voices muzzled for life." Because so many of them couldn't express themselves, "our mothers and grandmothers have, more often than not anonymously, handed on the creative spark, the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see: or like a sealed letter they could not plainly read." When she was little, Missy's mother had been offered a chance to tour the world singing gospel music, but Missy told me that when her mother saw her daughter in the window crying, she put her bags down and walked back in. When Missy walked out the door of her mother's house in 1991 and drove away from Portsmouth, she was doing what her mother could not. She has what Walker described as "the living creativity some of our great-grandmothers knew, even without 'knowing' it." And like those women, but with the dream of performing on bigger stages, Missy Elliott "never had any intention of giving it up."

When Katy Perry asked her to appear for exactly 2.5 minutes in the middle of Perry's set at the 2015 Super Bowl, it was Missy's first big appearance in years. Missy hadn't released an album since 2006. She's said that backstage, having had a panic attack that required medical care the night before, she swore to herself, "If I can get over this [first] step, then I know all my dance steps will be on point." Twenty-four hours later, "Get Ur Freak On," "Work It," and "Lose Control" would be downloaded about 20,000 times each, taking turns hitting the number one spot for downloads on iTunes.

Missy Elliott's mind thinks in bloom, and ideas emerge like buds pushing up from the ground. The Super Bowl story prompts her to tell me that typically she would be most comfortable having this conversation sitting on the floor.

To stay grounded?

"Yes, to stay humble."

Or maybe to remember that this adulation was not always there. The first big song she wrote was for Raven-Symoné in 1993, but when it came time to shoot the video for "That's What Little Girls Are Made Of," for which she rapped a verse, she didn't even receive a call about it. In the video, a thin, light-skinned model who has swallowed Missy's voice raps along with Raven. The rejection was so painful that Missy gave up on trying to be a star and devoted herself to songwriting. Three years later, she and Timbaland would write and produce the majority of Aaliyah's classic album One in a Million. When the record labels circled back around, this time they understood: They were signing someone who wanted her own imprint, with complete creative control over her music and the ability to freely write and produce for others. Missy Elliott was 24 when she got what she wanted from Sylvia Rhone, the CEO of Elektra Entertainment Group at the time, and she called it her new record label Goldmind Inc.

There is an early New Yorker profile of Missy that once referred to her look in "The Rain" as being that of a "cyber mammy." But Missy has never served or played servant to anyone in her life. There is nothing about Missy now, or then, that could belong in anything but a prosperous, liberated future. She even sings in "Work It": "Picture blacks saying yes sir, master? No!" A mammy as a trope was never a self-defined, self-articulating, sexualized woman. We knew nothing of her pleasure. If anything, the trash-bag suit in "The Rain" was about taking it all with you—the rarely spoken-about black woman's pleasure principle. (And who has written more songs about being sexually satisfied and self-satisfying than Missy Elliott?) The knowledge that you are beautiful. It is having been denied, and returning tender, exuberant, monumental, and hyperdimensional. "To me," Missy explained a few days after our first conversation, "the outfit was a way to mask my shyness behind all the chaos of the look. Although I am shy, I was never afraid to be a provocative woman. The outfit was a symbol of power. I loved the idea of feeling like a hip-hop Michelin woman. I knew I could have on a blow-up suit and still have people talking. It was bold and different. I've always seen myself as an innovator and a creative unlike any other."

What is off-putting about some of the interpretations of Missy Elliott's style is that they apply a retrograde framework to a woman who is so firmly from the future. And in doing so, they put undue, incorrect emphasis on her body, and assume things that tell us nothing about her and everything about the erasures that occur to women like her. In the late 2000s, she began to feel ill and suffer dizzy spells and unexplained weight loss. This played a large part in her taking time off. She was diagnosed with the thyroid condition Graves' disease, but when she did an interview with a New York radio station and tried to explain her condition, the host described her weight loss as the upside of her getting sick. To be a woman is to know that your flesh can matter more than your brilliance.

All world-building is an act of construction that requires real effort and no shortcuts. Perhaps because producing necessitates a specialized understanding of music, Missy the Producer doesn't get as much play as Missy the Performer. Both are solidifying elements of her autonomy, but the former guarantees her ability to be the architect of her own sound. Because it's a science to produce—it's a kind of alchemy to sit in a studio and bring forth music from nothing—women are discouraged from doing it. They are ignored when they master it, and, like any other science, they are underrepresented among those who are thought to be the best at it.

There is an interview that Björk did years ago for French television in which she describes the stress of being a woman and containing a certain rare level of musicality. "When somebody comes to make great music, I feel like I have less work to do," she confessed. "When Missy Elliott or, like, Peaches arrives with something good, I would be like, yes! It means I can do other things. Maybe I don't have to worry or stress about rhythmic music anymore because they are taking care of that." Young women are regularly taught how our bodies can be of service or put to work toward the desires of others, but rarely are we instructed how to be in charge of our art. "I remember," Björk has said, "seeing a photo of Missy Elliott at the mixing desk in the studio and being like, aha!" That Missy can draw all of the music out of herself, and work the board, write the music, and execute her ideas often goes undiscussed, but it makes her an aberration and a lighthouse. "When I was a kid, I wrote raps and I wanted to sound just like Missy," Syd, the lead singer of the R&B group the Internet, texts me one morning. A Grammy-nominated polymath, Syd sings, writes, produces, and engineers the majority of her music (and for years did so for her band, Odd Future). And like so many young black women in music, she knows she is a direct descendant of Missy Elliott's quiet revolution in the studio. "But I was even more inspired by her when I got older and learned how much other music she had written and produced. She is definitely one of my biggest role models in music. She's a genius…and her attitude shines through."

Missy Elliott has written more than 500 songs, produced music for Ciara, Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, and Whitney Houston, and taken just three vacations in her entire lifetime. She has written gospel songs that seem ready to break all the stained glass in the chapel with their high notes and full harmonies, and she has written a song where she implores her "pussycat" not to fail her. In her "Sock It 2 Me" video, she became the black woman who promised a new generation, just like Uhura did in Star Trek, that not only would we survive the new millennium and be found in the farthest reaches of the galaxy, we would be there fighting aliens in Teflon spacesuits, cracking up with our girls, smacking our gum, and looking good while doing it.

In her videos, Missy Elliott taught us how to move to her sound, to bop, to bounce along with her. "Missy was making films, you know? She was making three-minute films, working with the best technology at the time, and she still does, by the way," Pharrell explains. "And it felt like there were no bounds to what she could do, and she continued to teach people over and over again, you can do this, you can do that." And we learned to enjoy watching her. "I know my dances are going to be the puzzle," she says, "so even if you thought it was weird, I put the visual in your face so now you see how you're supposed to move to it." What she did with her body is move it as a dancer and performer. And her moves seem natural, like you could try it and not make a fool of yourself. But really she is possessed of a very singular ability as a choreographer: She knows how to put us all on the moon to dance with her without self-concern or a care in the world, and that is what only the greatest pop artists have done.

What is disarming about her in person is that all of these parts fit and feel rooted. She is a businesswoman, a flashy rapper, but she has a songwriter's need for solitude that brings to mind the moods of Kate Bush, Laura Lee, Sade, and Laura Nyro. The need to retreat and go deep and remain exceedingly private. "I'm probably like the lamest but still sauciest artist out there," Missy says. "I don't know how that works, where you cannot do nothing and still be saucy, but my friends, they always tell me when they come to the house, 'Ohh, you don't need to be an introvert' and 'Dude, you gotta get out, like you don't do nothing but just sit in the studio.' But you know, for me, I find comfort in that for whatever reason. It's, like, therapeutic for me."

Until it flooded, Missy spent a great deal of time at her mountain house near the Poconos, where bears would wander into her front yard and, because she was alone, she would have to wait until they wandered off to go outside. She tells me she likes to drive her cars and listen to old soul music.

She has worked with Timbaland since she was a teenager, but even he has never been in the studio with her when she records. "I'm private about recording, because it allows me to be myself and not have to worry. The energy has to be right for me, if I'm in that booth and somebody's energy is off and not really, like, moving their head or something, it may make me start to doubt what I'm doing. You gotta be careful in the energies that you let come in the room, because it will begin to make you doubt and fear and not want to take that risk."

"We been quiet too long lady-like very patient," she says in an interlude on her 2002 album, Under Construction. And there is a moment in her VH1 Behind the Music special where Missy's mother cringes. She is discussing Missy's decision to reveal the sexual abuse and violence that barbed itself around her childhood. "When Missy went open about the abuse," her mother says, "I was like, This is our secret; you don't tell the world what happened." Her mother was not being malicious. She was just afraid for her daughter. For many years, her mother lived with her in her house in Virginia; they are very close. But this is a generational reminder, a well-worn mode of discretion that most black girls hear at some point in their lives. It comes in many forms, a whisper in your ear to always keep your panties clean so if you are killed in an accident they will know you aren't a dirty woman, a curt warning not to tell your business in the street—these silences, this keeping it quiet, are supposed to let the world know who we are. I realized that what Missy had done on a very basic level is decide that those good intentions—meant to beckon us toward being flatter than we are, quieter than we are—wouldn't work for her as a rapper or a songwriter.

In 1983, Octavia E. Butler, the first major black

woman science fiction writer, published a story, "Speech Sounds," that

imagines a world where almost everyone has lost their voice, and because

of that they no longer remember how language works. One of the few

exceptions is a woman named Rye, and as the story progresses, she comes

to realize that even though is it dangerous to speak, she has to, and

she has to help the children who have been left behind, who like her are

still trying to form words and express themselves under such perilous

conditions.

On Missy's 2015 song "WTF (Where They From)," there is a sample of a young girl speaking. The voice belongs to Rachel Jeantel, the friend of Trayvon Martin who was on the phone with him when he was murdered. Missy doesn't bring this up, I do. She goes almost mute when I say that by sampling Jeantel's voice, Pharrell and she have done a remarkable thing that has reversed what usually happens to the words of girls who look like Rachel Jeantel. They have preserved them for the record, credited her for her voice and her words, and made sure she got paid. The witness becomes the writer. From the test comes the testimony.

And so a shy girl rises to the occasion, to speak, to write, and she becomes herself—because who else is going to explain why it is imperative that women don't put up with lousy lovers, or show us that we can wear sneaks every single day and still desire to get those nails done every other day? (Her nail tech, Bernadette, tells me: When it comes to glam, Missy is the most feminine artist of all time.) Missy is a multiplatinum artist who views Andre 3000 and Erykah Badu as her creative peers; she is an icon who likes to sit on the floor. This is what she does best: convince others that all of this is contained inside of her, while still finding a way to remain herself.

Across the street from the photo studio, the Chelsea Piers are turning themselves over to the night. And Missy's publicist and team are in a hurry to make sure I'm not taking up too much of her time, but Missy herself doesn't seem rushed to go anywhere yet. If anything, she seems deliberate. She sips through a straw from a cup of fresh-squeezed juice, and then she holds the cup with both hands. Her baseball cap is cocked to the side, and her two-inch nails are painted iridescent blue. Her legs are open but locked at the ankle. She looks in command—even more so because she is smiling.

I want to know more about her absences from the spotlight. What is it like to re-enter a world where Twitter can determine who becomes president, where music can feel like it was created to last for exactly for one minute and then disappear into the ether?

Yeah, it is a brave new world, she agrees. But she isn't despondent. Not at all.

"One thing I won't do is compromise." She takes another sip of juice and thinks for a moment. "I will never do something based on what everybody else is telling me to do. And have to kick myself in the ass every night," she says, drawing her head back and shaking it.

"Nah. I have to make sure that it's right," she continues. "I've been through so many stumbling blocks to build a legacy, so I wouldn't want to do something just to fit in. Because I never fit in. So…."

I wait for her to finish her sentence, but she doesn't. Her smile just grows into a laugh, a shy one, and then she shrugs. As if to say, Take it or leave it, love me or leave me.

It's a blueswoman's confidence, the realest shrug in the world, a gesture that comes from knowing full well that most of us made our choice about her a long time ago.

https://www.revolt.tv/2019/8/27/20852729/how-missy-elliott-s-influence-impacted-an-entire-generation

How Missy Elliott’s influence impacted an entire generation

In honor of her new Michael Jackson Video Vanguard award, let's examine all of the innovations that the famed rapper has made in music and culture throughout her career.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer or company.

by Dontaira Terrell

This year, at a glance, was a huge one for Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott. As the first female rapper to receive the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award at the Video Music Awards on Monday (Aug. 26) night, it's clear that her dominance in the industry is unyielding, and her substantial influence has left an imprint on a slew of artists from all genres.

During the VMAs, rapper Lizzo posed the question, "Where would hip hop be without Missy Elliott?" And mega-producer Timbaland reminded us, "People wouldn't do the videos they are doing today if it wasn't for [her]." The 48-year-old has tremendously impacted the game and is truly one-of-a-kind. She is known for pushing creative boundaries with confidence, charisma, and exceptional ease. Being in the game for more than 20 years, the Virginia native has influenced the music industry with new fashion, era-defining videos, innovative dance moves, and bold lyrical content. On top of that, Elliott has made a name for herself by crafting so many 90s and early 2000 anthems, and classic hits that black women can unapologetically relate to.

Just last week, the internet was abuzz after she dropped her EP Iconology, and a music video for "Throw it Back," a song from the five-track project. It was both refreshing and nostalgic to witness the creative aesthetic of the "Supa Dupa Fly" star back in her element. It also came as no surprise that the lead visual for the project instantly became the number one trending music video on YouTube.

Although the trailblazing songwriter stepped out of the immediate spotlight for several years, her widespread impact is extremely relevant. Weekly podcast "The Read's" hosts Kid Fury and Crissle West, and superfans worldwide championed for her comeback and for her to also receive the Video Vanguard Award. Fast forward and campaigning for her continued success paid off, and spoke to the indelible footprint that she has deeply embedded in the culture.

After killing the stage during her performance and recreating a few of her iconic videos such as "Lose Control," "Pass That Dutch," and "Work It," the star humbly accepted her Moonman trophy. The trailblazing talent made sure to thank her loyal day ones when she said, "I have worked diligently for over two decades. It means so much to me. I promise it doesn't go unnoticed, the love and support y' all have shown me over the years."