SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER THREE

DONALD HARRISON

(October 2-8)

CHICO FREEMAN

(October 9-15)

BEN WILLIAMS

(October 16-22)

MISSY ELIOTT

(October 23-29)

SHEMEKIA COPELAND

(October 30-November 5)

VON FREEMAN

(November 6-12)

DAVID BAKER

(November 13-19)

RUTHIE FOSTER

(November 20-26)

VICTORIA SPIVEY

(November 27-December 3)

ANTONIO HART

(December 4-10)

GEORGE ‘HARMONICA’ SMITH

(December 11-17)

JAMISON ROSS

(December 18-24)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/donald-harrison-mn0000184406/biography

A celebrated New Orleans-born jazz saxophonist, Donald Harrison is an adept performer known for a hard-swinging improvisational style that touches upon acoustic post-bop, traditional New Orleans jazz, and R&B. Harrison initially emerged as a young lion in the '80s, playing in Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers alongside trumpeter Terence Blanchard. Harrison and Blanchard then signed with Columbia Records and issued several highly regarded albums, including 1987's Crystal Staircase and 1988's Black Pearl. On his own, the saxophonist has displayed an innovative knack for mixing New Orleans second rhythms, jazz, hip-hop, and R&B on albums like 1992's Indian Blues and 1997's Nouveau Swing. Having lived through Hurricane Katrina, he appeared in Spike Lee's HBO documentary When the Levees Broke, and issued his own homage to the city with 2006's The Survivor. While he splits his time between New York and New Orleans, Harrison (who was named Big Chief of The Congo Square Nation Afro-New Orleans cultural group in 1999) remains a vital proponent of his birth city's music and cultural heritage.

Born in New Orleans on June 23, 1960, Harrison is the son of the late Donald Harrison, Sr., a legendary New Orleans folklorist and, during his lifetime, the Big Chief of four different NOLA tribes. The younger Harrison began his education at the prestigious New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts and studied with Ellis Marsalis. After graduation, he attended the Berklee College of Music. Though he began playing as a professional while in high school, Harrison gained recognition for his tone and acumen on both alto and tenor horns, playing in the bands of Roy Haynes, Jack McDuff, and most famously, Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers along with trumpeter and future musical partner Terence Blanchard -- they succeeded Wynton and Branford Marsalis.

The pair left Blakey's band and began recording as the Terence Blanchard/Donald Harrison Quintet. Between 1983 and 1988, they issued five albums, including New York Second Line (1984) and Discernment (1986), both for Concord, and Nascence (1986), Crystal Stair (1987), and Black Pearl (1988) for Columbia. While with the unit, Harrison also took part in recording sessions in the jazz vanguard: in 1985, he played on the avant The Sixth Sense (Black Saint) with Bobby Battle, Olu Dara, and Fred Hopkins, and in 1986, he recorded with Don Pullen. The Quintet split in 1989.

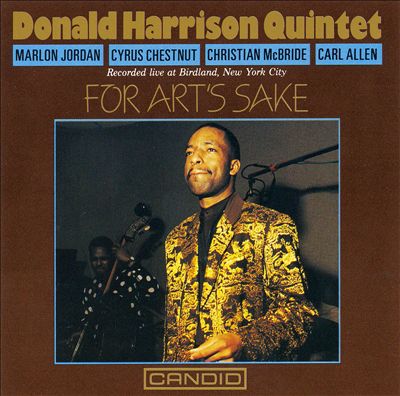

As a bandleader in his own right, Harrison issued the hard bop Blakey tribute album For Art's Sake on Candid in 1991, and followed it with the historic Indian Blues. It was the first time that Harrison actively engaged his New Orleans musical heritage on a large scale. It wedded Mardis Gras Indian tunes and chanting (courtesy of the Guardians of the Flame Mardi Gras Indians, with his father on vocals), to funky Crescent City rhythm & blues and modern jazz. The session featured Dr. John, Cyrus Chestnut, Carl Allen, Phil Bowler, Bruce Cox, and Howard Smiley Ricks. Harrison also recorded the smooth jazz date The Power of Cool, which was released in Germany in 1991, and in the States in 1994.

In 1993, he signed to GRP/Impulse. His first album for that label was Nouveau Swing, the album -- and concept -- that gave Harrison his nickname "the King of Nouveau Swing." That set employed straight-ahead jazz concepts on half the set, and Caribbean rhythms on the remainder. His follow-up went even further afield, establishing the nouveau swing concept by including Latin rhythms, more rhythm & blues, smooth jazz, and even hip-hop. In 1999, Harrison officially became a Big Chief and founded the Congo Nation Mardi Gras Indians to honor his father and further New Orleans African roots culture. To close out the century, he recorded The New Sounds of Mardi Gras, which merged New Orleans traditional music with hip-hop.

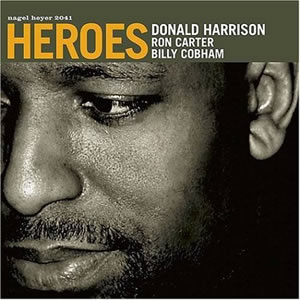

In 2000, Harrison issued the landmark Spirits of Congo Square album, recorded with his New Orleans Legacy Ensemble. The album featured parade rhythms -- and hard bop solos -- whether the tune was a traditional NOLA number or a jazz standard by a modern composer. In 2002, he issued his first collaboration with nephew Christian Scott in a quintet setting of newly arranged jazz standards called Kind of New. In 2003, he recorded a pair of albums for Nagel Heyer Records. The first, Free Style, may have been a thorough jazz date, but it was entirely inspired by hip-hop rhythms. The second, Heroes, with Ron Carter and Billy Cobham, was more conventionally post-bop, but offered extremely inspired playing by each of the trio's members. In 2004, Harrison also issued Paradise Found, his second quintet offering with his nephew.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Harrison began to immerse himself in New Orleans' life as an educator as well as a musician and Big Chief. He began employing high school students in his bands and had them play dates with other professional musicians in order to foster New Orleans' musical heritage and to give the younger players more professional exposure. Many musicians had left the city in the aftermath of Katrina, and Harrison saw it as his duty to keep the flame alive.

In 2006 he issued Survivor, a straight-ahead jazz date with Mulgrew Miller and others. He also released the first volume of a projected three-album series entitled 3D (one volume to showcase each of his playing styles). This first entry focused on the commercially viable side of Harrison's musical identity in smooth jazz, urban rhythm & blues, and funk. (Vols. 2 & 3 will be dedicated to straight-ahead jazz and hip-hop, respectively.) In 2008, he released The Chosen in Europe only. In 2009, he released three titles on Nagel Heyer: The Ballads, The Burners, and Two of a Kind with Christian Scott. In 2010, Harrison became an occasional member of the cast of the HBO television series Treme, playing himself. The saxophonist then reunited with Carter and Cobham for a live date entitled This Is Jazz: Live at the Blue Note, playing a program of originals and standards. It included a new Harrison composition entitled "Treme Swagger." He then issued the concert album Live at Jazzfest 2018.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/donald-harrison

"Donald Harrison is one of the most confident and convincing improvisers in jazz today."

—All About Jazz

Updated: May 20, 2021

Biography

Articles

News

Press

Similar

Born: June 23, 1960

New Orleans born saxophonist Donald Harrison is a musician/composer who master musicians consider a master of every era of jazz, soul, funk, and a composer of orchestral classical music. He is also a genius, according to geniuses like Eddie Palmieri and Mike Clark. In the HBO drama Treme, Emmy winning director David Simon created two characters to portray how Harrison innovated new styles of music. Harrison has appeared as an actor/musician in 9 episodes of Treme, Oscar-winning director Johnathon Demme’s film Rachel Getting Married, Spike Lee’s When The Levee’s Broke documentary, and Marvel’s Luke Cage. This talented artist is the recognized Big Chief of Congo Square in Afro-New Orleans culture and was made a Chief in 2019 by Queen Diambi Kabatusuila in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa.

Harrison honed his experience playing with Roy Haynes, Art Blakey, Eddie Palmieri, Dr. John, Lena Horne, McCoy Tyner, Dr. Eddie Henderson, Miles Davis, Ron Carter, Billy Cobham, Chuck Loeb, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Digable Planets, Guru’s Jazzmatazz, The Headhunters, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and The Notorious BIG. He has performed with over 200 jazz masters and created three influential styles of jazz. At the age of nineteen, Harrison created a modern jazz take on the New Orleans second-line tradition and introduced his composition New York Second-Line to the jazz world in 1979. By the mid-’80s, he created Nouveau Swing, a distinctive sound that blended the swing beat of modern jazz with hip-hop, funk, and soul music. In the ’90s, Harrison recorded hits in the smooth jazz genre. He began exploring music through the lens of quantum physics in 2000. With quantum jazz, Harrison heard how to move music from a two-dimensional state into a four-dimensional state. Harrison has been a mentor to artist as diverse as The Notorious Big, Jonathon Batiste, Christian Scott, Trombone Shorty, and Esperanza Spaulding.

In 2020 look for Harrison performing Charlie Parker with strings in tribute to his centennial. He is composing orchestral classical music for upcoming premiers and adding hip-hop/jazz to his multi-genre recordings and performances.

Awards

2007 Jazziz Magazine Person of the Year

2007 Arts Council of New Orleans Community Arts Award Recipient

2008 Big Easy Music Awards Ambassador of Music

Gear Donald Harrison is an International Woodwind Artist

http://www.internationalwoodwind.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Harrison

Donald Harrison

Biography

The foundation of Harrison's music comes from his lifelong participation in New Orleans culture. He started in New Orleans secondline culture and studied New Orleans secret tribal culture, under his father, Big Chief Donald Harrison Sr.[2] Whereas, Harrison Jr. is currently the Chief of Congo Square in Afro-New Orleans Culture. He studied at the Berklee College of Music.[2] As a professional musician he worked with Roy Haynes and Jack McDuff, before joining Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers with Terence Blanchard and recorded albums in a quintet until 1989.[1] Two years later, Harrison released a tribute album to Blakey, For Art's Sake.[3] This was followed by an album that reached into Harrison's New Orleans heritage, with guest appearances by Dr. John and Cyrus Chestnut and chants by the Guardians of the Flame Mardi Gras Indians.[4] He devoted half the album, Nouveau Swing (1997), to mixing the swing beat of modern acoustic jazz, with modern dance music and half to mixing the swing beat with Caribbean-influenced music.[5] On the next album, his experiments continued by mixing modern jazz's swing beat with hip hop, Latin music, R&B, and smooth jazz.[6][7]

His albums, 3D Vols. I, II, and III, present him in three different musical genres. On Vol. I he writes, plays, and produces smooth jazz and R&B style.[2] On Vol. II he writes, produces and plays in the classic jazz style. On Vol. III he writes plays and produces hip hop.

His group, Donald Harrison Electric Band, has recorded popular radio hits and has charted in the top ten of Billboard magazine. He performs as a producer, singer, and rapper in traditional New Orleans jazz and hip hop genres with his group, The New Sounds of Mardi Gras.[2] The group, which has recorded two albums, was started in 2001 and has made appearances worldwide. In 1999, Harrison was named the Big Chief of the Congo Nation Afro-New Orleans Cultural Group, which keeps alive the secret traditions of Congo Square.[2]

In 2016, Harrison recorded his first orchestral work with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. He followed up the piece for the MSO by writing classical orchestral works for the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra, The New York Chamber Orchestra, and The Jalapa Symphony Orchestra in 2017.

Harrison has nurtured a number of young musicians including trumpeter Christian Scott (Harrison's nephew), Mark Whitfield, Christian McBride, and The Notorious B.I.G.[8] Harrison was in Spike Lee's HBO documentary, When the Levees Broke, and has appeared as himself in eleven episodes of the television series, Treme.[9]

Harrison was chosen Person of the Year by Jazziz magazine in January 2007.

Discography

As leader

- 1990: Full Circle (Sweet Basil)

- 1991: For Art's Sake (Candid)

- 1992: Indian Blues (Candid) with Dr. John

- 1994: The Power of Cool (CTI)

- 1997: Nouveau Swing (Impulse!)

- 1999: Free to Be (Impulse!)

- 2000: Spirits of Congo Square (Candid)

- 2001: Real Life Stories (Nagel Heyer)

- 2002: Kind of New (Candid)

- 2003: Paradise Found (Fomp)

- 2004: Heroes (Nagel Heyer)

- 2004: Free Style (Nagel Heyer)

- 2005: New York Cool: Live at The Blue Note (Half Note)

- 2005: 3D (Fomp)

- 2006: The Survivor (Nagel Heyer)

- 2008: The Chosen (Nagel Heyer)

- 2011: This Is Jazz: Live at The Blue Note (Half Note)[10]

As co-leader with Terence Blanchard

- 1983: New York Second Line (Concord)

- 1984: Discernment (Concord)

- 1986: Nascence (Columbia)

- 1986: Eric Dolphy & Booker Little Remembered Live at Sweet Basil, Vol. 1 (Evidence)

- 1986: Fire Waltz: Eric Dolphy & Booker Little Remembered Live At Sweet Basil, Vol. 2 (Evidence)

- 1987: Crystal Stair (Columbia)

- 1988: Black Pearl (Columbia)

As sideman

With Art Blakey

- Oh-By the Way (Timeless, 1982)

- New York Scene (Concord, 1984)

- Blue Night (Timeless, 1985)

- New Year's Eve at Sweet Basil (Evidence, 1985)

With Joanne Brackeen

- Turnaround (Evidence, 1992)

With The Headhunters

- Evolution Revolution (Basin Street, 2003)

With the Brian Lynch/Eddie Palmieri Project

- Simpático (ArtistShare, 2007)

With Eddie Palmieri

- Palmas (Elektra Nonesuch, 1995)

- Arete (RMM, 1995)

- Vortex (RMM, 1996)

- Listen Here! (Concord, 2005)

- Wisdom/Sabiduria (Ropeadope, 2017)

With Don Pullen

- The Sixth Sense (Black Saint, 1985)

With Lonnie Smith

With Esperanza Spalding

With Jane Monheit

On DVD

- Live with Clark Terry

- Live at the Supper Club with Lena Horne

https://www.thelastmiles.com/profiles_donald-harrison/

Miles’s Musician Profiles: Donald Harrison

Background before joining Miles: Played with Art Blakey, Terence Blanchard, Roy Haynes.

How he got the Miles gig: Harrison received a call to contact Miles. Miles invited him to his house and he was then invited to join the band.

Played from: A couple of weeks in December 1986, alongside Bob Berg.

Official albums and DVDs featured on: None

Tracks worth checking out: N/A

Harrison on Miles: “To me, he was really into people. He was fully aware of what was going on in the world of music. I learnt that to get it right, you have to have an understanding of people. Because whenever you study people, you write music that is informed from the times that you live in. That’s why he was always correct.”

Comments: Harrison’s main instrument is the alto saxophone and he complemented Bob Berg, who played tenor and soprano saxophone. The nature of Harrison’s arrival and departure in and out of Miles’s band is shrouded in mystery (Harrison says he didn’t quit, but nor was he sacked). After leaving Miles’s band, he re-joined Terence Blanchard and also played with numerous artists including, Tony Williams, Ron Carter and Billy Cobham. Next month’s update will feature an interview with Donald.

The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis

1980-1991

A Book by George Cole

The Last Miles is published by Equinox Publishing in the UK and the University of Michigan Press in the USA.

http://www.thecookersmusic.com/about/donald-harrison/

Donald Harrison

Donald was born in New Orleans in 1960 and grew up in a home environment saturated with the city’s traditional music of brass bands, parades, modern Jazz, R&B, Funk, Classical, World and Dance music. His connection to New Orleans roots were deepened by his father, a Big Chief, in a new style of African culture developed New Orleans. The culture is an offshoot culture of Congo Square, one of the only known places in North America where Africans openly participated in their culture in the 18th and 19th centuries and has incorporated some aspects of Native American culture as well. Donald himself became the Big Chief of The Congo Square Nation Afro-New Orleans cultural group in 1999 and coined the term Afro-New Orleans. He built the first costume that merges East, West and Central African designs with Afro-New Orleans style cultural designs.

Donald also created “Nouveau Swing,” a style of jazz that merges it with modern dance music like R&B, Hip-Hop, Soul and Rock. He also combined jazz with Afro-New Orleans traditional music on his critically acclaimed albums “Indian Blues” (1991) and “Spirits of Congo Square” (2000). The recordings deepened Harrison’s commitment to maintaining the offshoot rituals, call and response chants and drumming as well as traditional jazz music alive for the next generation.

Donald has performed and recorded with an illustrious list of distinguished musicians in Jazz, R & B, Funk, Classical and more including Art Blakey, Roy Haynes, The Cookers, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Lena Horne, Ron Carter, Billy Cobham, Eddie Palmieri, Jennifer Holiday, Dr. John, Guru’s Jazzmatazz, McCoy Tyner, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Digable Planets, Notorious BIG, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra and The Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra to name just a few.

As an actual evacuee/survivor of Hurricane Katrina, he had a prominent role in Spike Lee’s HBO documentary “When the Levees Broke.” He also appeared as himself and co-wrote the sound track for Academy Award winning director Jonathan Demme’s feature film “Rachel’s Getting Married” starring Anne Hathaway and Debra Winger. Aspects of Donald’s life and music are chronicled with two characters in David Simon’s ground breaking HBO series, Treme. He was also a character consultant and appeared as himself in eleven episodes.

Donald recorded “Quantum Leap” in 2012, which musicians and critics agree is a next step for jazz and is an amalgamation of his years of playing with jazz masters and his life’s experiences. With quantum jazz, Donald has opened up new areas for time, harmony, and melody. The recording also melds cutting edge jazz with New Orleans funk, connecting the past with the present with jazz music that transcends boundaries.

Donald is also co-founder and artistic director for the Tipitina’s Intern Program and founder of The New Jazz School where he along with a staff of his hand pick of seasoned veterans teach Jazz, Soul, Funk, theory, harmony, composition, and history to students ages 13 to 18. The Tipitina’s Intern Program is a college preparatory and professional music training program for junior and senior high school students. The program at Tip’s has garnered close to $10,000,000.00 in scholarships for it’s graduates and placed many prominent young musicians amongst the professional ranks. Harrison taught and mentored the following musicians: trumpeter Christian Scott, hip-hop icon The Notorius B.I.G., trombonist/singer Trombone Shorty, guitarist Josh Connelly and saxophonists Louis Fouche, Chris Royal and Aaron Fletcher. His working groups have proven to be an incubator for jazz bandleaders such as trumpeter Christian Scott, guitarist Mark Whitfield, pianist Cyrus Chestnut and bassists Christian McBride and Esperanza Spaulding.

His awards include two of France’s “Grand Prix du Disque”, Switzerland’s “The Ascona Award”, Japan’s Swing Journal “Alto Saxophonist of the Year,” The Jazz Journalist Association’s “A List Award,” 2012 New Orleans Civic Award, 2007 Jazziz Magazine’s “Person of the Year,” the Big Easy Music Awards “Ambassador of Music” and is a Down Beat Magazine Alto Saxophone Poll Winner. He was also a 2006 Resident at William and Mary College, a 1995 “Meet The Composer” recipient and has also earned a 2012 Grammy nomination.

Website: http://donaldharrison.com/

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/donald-harrison-jr

Donald Harrison, Jr.

Photo courtesy of Donald Harrison, Jr.

Bio

Harrison is the son of the late New Orleans folklorist Donald Harrison, Sr., who was known for his involvement in local Mardi Gras traditions. Like his father, Harrison devoted himself to the Crescent City's multifaceted cultural heritage, founding the Congo Square Nation Afro-New Orleans Cultural Group to honor the place that Blacks, both free and enslaved, could sing and dance in public. “The incredible part to me is, even though the players today don’t have a consciousness of that, some of those things are still at the root of what we call jazz music,” Harrison noted in a 2021 Tennessean story.

He also has served as artistic director and educator for Tipitina's Foundation's Internship Program, a nonprofit after-school program for New Orleans high school students interested in music business careers. The program allowed them to perform at New Orleans-based festivals and gave them opportunities to travel to Los Angeles, Memphis, New York, and even to Japan for performances, cultural exchange, and master class experiences.

Harrison studied at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts with Ellis Marsalis, Jr. before attending the Berklee College of Music in Boston. Playing professionally during his high school years, Harrison soon was noticed for his talent on both the alto and tenor horns, playing in the bands of Roy Haynes, Jack McDuff, as well as in Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, along with fellow New Orleans native, trumpeter Terence Blanchard.

Harrison also performs in the traditional New Orleans jazz and hip-hop genres with his group the New Sounds of Mardi Gras and has performed and recorded with distinguished musicians such as Ron Carter, Billy Cobham, Miles Davis, Lena Horne, Eddie Palmieri, the Notorious B.I.G., as well as with the powerhouse jazz group the Cookers. As part of his dedication to preserving New Orleans traditions, Harrison appeared in Spike Lee's When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts, a documentary about the devastation on the city after Hurricane Katrina hit, and also in the post-hurricane New Orleans HBO series Treme. He continues to celebrate and promote the culture and music he loves.

Selected Discography:

Donald Harrison/Terence Blanchard, Black Pearl, Columbia, 1988

Nouveau Swing, Impulse!, 1996

Spirits of Congo Square, Candid, 2000

The Survivor, Nagel Heyer Records, 2004

The Cookers, The Call of the Wild and Peaceful Heart, Smoke Sessions, 2016

Being chosen amongst the illustrious list of NEA Jazz Masters is an honor nonpareil. For me, this is an acknowledgment for staying the course in jazz culture, and it leaves me in awe. I hope the future sees me on the same path of learning our music then sharing those lessons with others. I dedicate this honor to my parents, Donald and Herreast, my wife Mary, my daughter Victoria, and my siblings Cherice, Michele, and Cara. In addition to them, my nephews Brian, Kiel, and Chris, son-in-law Derrick, family, friends, and all who use their lives to keep and advance jazz. I am grateful to the NEA for having the Jazz Masters Fellowships. In my estimation, the award recognizes the work against all odds that jazz artists and advocates wage every day. In my case, the award showcases that I live on both sides of the aisle. My role is that of a musician and cultural participant who has advocated for all. My heart is joyous and humbled for being selected as the 2022 A.B. Spellman Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy recipient. The work and passion of A.B. Spellman toward jazz being the best it can is a shining beacon that I will work to purport as a musician, teacher, and proponent.

Arts & Entertainment

The Musical Journey of Donald Harrison

Harrison's Journey Includes Honorary Doctorate, Star-Studded Global Performance Video, Coltrane-Inspired Single, Concert Tour and More

As the jazz world slowly emerges from the more than year-long pandemic, the New Orleans-born alto saxophonist Donald Harrison– the critically-acclaimed, innovative musician with four decades of experience as an instrumentalist, sideman and leader who has worked with everyone from Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers and salsa legend Eddie Palmieri, to the legendary rapper Notorious B.I.G. – unleashed a flurry of new projects, along with some prominent news features.

On May 8, Harrison was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Music from his Alma Mater, Berklee College of Music, as part of the virtual Class of 2021 commencement. As President Roger Brown stated, Harrison was awarded his doctorate for "his creativity, innovation and lasting impact on jazz." Accepting his award, Harrison spoke of how heartwarming it was to "receive an Honorary Doctorate and have the opportunity to communicate my experiences with our students, their parents, guardians, and advocates of music."

Harrison is featured in the new global video production of the New Orleans R&B standard, "Iko Iko," produced by the Playing for Change Foundation, a non-profit, 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to building music and art schools for children around the world, and creating hope and inspiration for the future of our planet. The video features musicians performing from Ghana, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Panama, Costa Rica, Italy, Japan, Los Angeles and New Orleans, featuring Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann (both of The Grateful Dead), Ivan Neville, the late Dr. John and Harrison, chanting and playing the saxophone in his stunning Congo Nation, Afro-New Orleans-inspired attire. Check out the video at https://playingforchange.com/.

"I'm an Afro-New Orleans cultural participant," Harrison says. "I know the secrets that go all the way back to Africa, and how they were used in jazz, and I'm probably the only jazz musician who knows that." Harrison formed Congo Nation, an Afro-New Orleans cultural group in 1999, and learned those chants from his father, Donald Sr.

Harrison is also set to release his first single of the year, entitled "Upper Stratus," his take on John Coltrane's complex, supersonically syncopated 1959 composition, "Countdown," from Harrison's latest two-disc CD, The Eclectic Jazz Revolution of Unity. "What I noticed about John Coltrane is that he played basically eight notes on "Giant Steps"and "Countdown," … Harrison says, "so I figured out how to add all these other tiny spaces where you're doubling up, playing across the time and putting forms inside of forms, and to my surprise, the musicians are saying that I actually moved Trane forward to another perspective."

Harrison's latest CD, also features "Stepper's Paradise," a grooving, track composed for the Chicago-based, urban dance genre, called Steppin,' which features his daughter Victoria Harrison on vocals. The compilation also includes "Congo Square," a three-part symphonic opus Harrison composed and recorded with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra in 2015. "The first movement is a chant with drums and percussion," Harrison says. "The second movement features the orchestra utilizing those real life chants from Congo Square, and the third movement features the jazz band with the symphonic orchestra."

The saxophonist's other recent releases include his multi-genre single, "The Magic Touch," which combines two versions of the composition – a 2007 acoustic version featuring pianist Victor Gould and a 2005 smooth jazz track featuring trumpeter Chris Botti, guitarist Chuck Loeb and members of the soul group Maze. In 2019, Harrison released his swinging, straight-ahead take on Lil Nas X's mega-hit single, "Old Town Road."

In his four decades on the scene, Harrison has contributed three genres to the jazz continuum. He created an Upsouth version of his hometown's parade rhythms called the New York Second Line, which was the title of the 1983 album he co-led with Terence Blanchard. In the nineties, he debuted his concept of Nouveau Swing: his jazz-inflected mix of soul, jazz, Afro-Caribbean, soul and hip-hop, which can be heard on the albums, Nouveau Swingand Free to Be. In the early 21stCentury, he unveiled his quantum jazz concept on his 2010 CD, Quantum Leap, where "the African drums had a link to quantum physics, because the drummers of West Africa are connected to the universe," Harrison says, "which led me to understand that we think of music in two dimensions, and through Quantum Jazz, I can hear music in four dimensions, with new ideas in time in every direction."

Harrison is a presence on the TV and the silver screen. He's featured in the recent Christopher Wallace/Notorious B.I.G. Netflix documentary, Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell, as an early music tutor to the rapper. "I was initially trying to groom Chris to be a jazz artist, because he was so talented," Harrison says in the documentary. "One of the things we worked on was putting what a snare did in bebop drumming into the rhythm of a rhyme. We listened to Max Roach with Clifford Brown … Max has a very melodic way of playing the drums … Notorious B.I.G. was accenting those notes in a way that exudes all of the qualities of a bebop drummer." Harrison has also mentored many musicians, including his nephew, Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, Esperanza Spalding, Trombone Shorty and Jon Batiste.

"I remember coming up trying to figure things out musically, trying to figure out how to lead a band, how to be a performer, how to play my instrument on the highest level possible. Donald Harrison is considered to be one of the greatest educators in the last 50 years for anyone, in any style of music," said Batiste about his mentor.

In the HBO series Treme, Emmy-winning director David Simon created two characters to portray how Harrison innovated new styles of music, and he appeared in nine episodes. Harrison was also featured in Oscar-winning director Johnathon Demme's film, Rachel Getting Married, Spike Lee's When The Levees Brokedocumentary, Marvel's Netflix series Luke Cage, and he had a cameo as a child in the James Bond 1973 film, Live and Let Die.

Picking up where he left off before the pandemic shut down venues around the world, Donald has a busy performance schedule, including:

· July 8-9 – Baltimore, Keystone Korner (with the Headhunters)

· July 24 – Chicago, Super Chill Backyard Festival (with Mike Clark, Fred Wesley, Robert Walter, Will Bernard)

· July 25 – Indianapolis, The Jazz Kitchen (Mike Clark + Donald Harrison Organ Quartet featuring Kendall "Keyz" Carter)

· August 7 – New Orleans, Snug Harbor (Donald Harrison Quartet Tribute to Bird)

· August 12-15 – Chicago, Jazz Showcase (Donald Harrison Quartet Tribute to Bird)

· August 19-21 – New York City, Birdland (Donald Harrison Quartet Tribute to Bird)

· August 25 – Baltimore, Keystone Korner (Donald Harrison Quartet Tribute to Bird)

· August 28 – Charlie Parker Jazz Festival (Donald Harrison Quintet & The Harlem Symphony Orchestra play Charlie Parker with Strings)

Harrison continues touring throughout September and October with performances in Long Island, Minneapolis, Seattle, Denver and several dates at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

An articulate spokesman for jazz, Harrison is often quoted and featured in newspapers and magazines. In a February 22, 2021 USA Todayarticle about New Orleans music, Harrison remarked on how modern musicians channel the spirit of New Orleans music, "even though the players today don't have a consciousness of … some of those things are still at the root of what we call jazz music." Harrison has also been featured in Hot House, Jazziz, JazzTimes, the New York Timesand Wall Street Journal, among others.

New Orleans is the source of Harrison's multifaceted musicianship. Born there on June 23, 1960, Harrison grew up playing with the same broad approach to music that Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet and all of his forebears did, playing jazz, funk, R&B, Latin, blues, gospel and traditional New Orleans music. Harrison is a graduate of the famed New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (/NOCCA), which also included Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Harry Connick, Jr. and future partner Terence Blanchard. He attended Southern University before he transferred to Berklee.

Harrison has recorded 17 recordings as a leader and performed and recorded with over 250 musicians, including Roy Haynes, Art Blakey, Dr. John, Lena Horne, McCoy Tyner, Dr. Eddie Henderson, Miles Davis, Ron Carter, Billy Cobham, Chuck Loeb, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Digable Planets, Guru's Jazzmatazz, The Headhunters and The Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He is a long-standing member of Latin pianist Eddie Palmieri's ensembles, and is a member of the jazz collective, The Cookers. "The lessons of all those great masters gave me the real deal, not out of a book," Harrison says.

A truly multi-dimensional musician, Donald Harrison continues to go forward and is boldly heading where no jazz musician has gone before. 'I'm trying to learn as much as I can from the masters, and see where the music takes me."

A Serious Jazz Take on "Old Town Road"? Big Chief Donald Harrison, Jr. Has Got It Covered

Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road,” the country-trap single and pop-cultural juggernaut, just ended its record-breaking run at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, after a staggering 19 weeks. But while its chart-topping dominion may be over, its impact keeps rippling outward. It was probably only a matter of time before a jazz musician took the reins.

Donald Harrison, Jr. — prominent alto saxophonist, veteran jazz educator, Big Chief of the Congo Nation Afro-New Orleans Cultural Group — was the person to do it.

His instrumental version of “Old Town Road,” made with a New Orleans rhythm section, is an attempt to harness the renegade spirit of the original within the hybrid style that Harrison calls “Nouveau Swing.” The track has just been released as a single on Spotify and Apple Music, and can also be heard here.

It opens with a brooding ostinato in G-sharp minor, just as the original does (to the extent that an “original” version can accurately be traced). But there’s a bounce in the bass line, and Harrison’s entry on alto is pure post-bop swagger. Yep, he’s gonna ride ‘til he can’t no more — but at his own clip, in any direction he chooses.

Curious about the inspiration for the track, and the way it all came together, I called Harrison this week. We talked about how “Old Town Road” connects to jazz history (really) and what it means to bring such disparate musical elements together in a way that breathes. Here is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

This has been the summer of “Old Town Road.” Do you remember how it first hit your radar?

I was looking through music on YouTube, and there was a video of Lil Nas X performing his song for a country-music audience. The energy of his performance caught my eye. I really enjoyed it. I said, ‘This kid is doing something that I’ve been trying to do for jazz music, which is unite people.’ Then I started thinking about what I could do with that in a jazz context.

You mention bringing people together, and the song has absolutely proven itself in that regard. But when did you become aware of the controversy around its exclusion from Billboard’s Country chart?

For me, music is inclusive. That’s a statement I’ve been making for a long time. So once you say this is exclusive to only these artists, it becomes something motivated by prejudice. That’s really unfortunate. Maybe he’s not a master of country music. But I don’t think he was trying to be. He mixed different forces together and came up with a new sound.

And the back story of that sound is fascinating: a darkly atmospheric Nine Inch Nails sample that gets mixed with a trap beat. There’s something about that amalgamation that must feel familiar to you, coming from New Orleans.

Really, it’s the history of jazz music. I consider myself a jazz artist who adds other things to it. Duke Ellington, Sidney Bechet, John Coltrane – these were people who added to what the music already was. Now, it’s a little different because those guys actually mastered jazz music, and then added to it. I don’t know that Lil Nas X has mastered certain styles of music. But he is a person who, in my estimation, figured out how to put different elements together and come up with something that touches everybody who hears it. Whether you love country music, or love trap music, or love Nine Inch Nails, you have to commend him for that.

He’s also such a magnetic performer. He comes out with the fringe jacket and the cowboy hat…

[Laughs]

…and I wonder how that speaks to you. When we talk about presentation, and the power of embodying a persona, what insights can you share as someone coming out of the Mardi Gras Indian tradition?

First of all, I’ve renamed what I do. I consider myself a participant in Afro-New Orleans culture now, because I’m coming out of Congo Square. Some of the older guys told me that when they were masking, they were masking African culture. There’s different factions who consider themselves Mardi Gras Indians, which is a term that was made up in the ‘70s. But that’s a convoluted subject.

It’s an important distinction, though, and a terminology that I can use, going forward.

Right. Anyway, this morning I was looking at George Clinton. When he started putting on those outfits, people paid attention. I just feel like this kid, Lil Nas X, the way he dresses, he was bringing different factions together, and all the things that he may be into. The tradition I come from, it’s understanding that our cultural attire tells a story linked to antiquity. You have to understand all of those elements and then, just like jazz music, try to push it forward and create something that speaks to who you are. So, you know what? Maybe the way he dresses — the cowboy hat and the multicolored clothes that he wears — maybe he’s adding those elements to speak of himself. Which is the same thing I’m doing, to speak of who I am as a chief.

Back in June, the Postmodern Jukebox posted their cover of “Old Town Road,” with Miche Braden on vocals. It’s a lighthearted pastiche, which is their stock in trade. By contrast, when I heard your version, I was struck by the seriousness of the intention. How important was that to convey?

There are different ways of approaching songs. My first inclination is to make sure that the history of this music, which we call jazz, is present in what we play. The idea of reaching for your highest level is always there. I felt that this was a vehicle where we could do that, and also try to be true to the essence of trap music, with some country and some bebop in there, some John Coltrane. Take all those elements and move some ideas forward, from a perspective of understanding and connection to the universe. From my deepest convictions, so that it would be serious, and feel serious.

Speaking of trap rhythm: your nephew, Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, is another improviser who has incorporated it into his music, in a way that feels very organic.

Right. He calls his style “Stretch Music,” but I consider it an offshoot of Nouveau Swing. We came to a compromise: Now he says: “No Nouveau Swing, no Stretch.” I’ll go with that. [Laughs] But I was fortunate in that I had already told my drummers to learn how to play the trap beats on the drum set, so that they would be comfortable with playing that kind of music but with the feeling of a human being. The young kids I teach, I tell them to learn bebop and all the different styles of jazz, from New Orleans jazz to Albert Ayler, and everything in between.

And the musicians on this single — unless I’m mistaken, these are all New Orleans musicians of a younger generation.

Except for Chris Severin, the bassist, who’s actually a little older than me. He’s playing in a way where you can hear a little bit of the hip-hop influence, but you can also hear that he’s a seasoned jazz person. The drummer, Thomas Glass, he’s about 20 years old. He’s one of my students. And the pianist, Shea Pierre, went to Oberlin but he was one of my students as well. All of these guys are adept at a lot of different styles of music. And that’s key for me. That we can go play Sidney Bechet one minute, and then Charlie Parker the next minute. And put them together.

You play that recognizable vamp from “Old Town Road,” and then you introduce a second vamp. Where did that counter-vamp come from?

I just felt it needed another element for what we were doing. So in the studio I said “Let’s just put this in here. It’ll make the song have more feeling in it, and be more exciting.” That’s why I did that. At first it was a little unbalanced, but when I heard it over I said “No, we came up with a good thing here.” And actually, everybody who hears it, that’s the part they can’t get out of their mind.

Have you performed this song live?

We haven’t,

as of yet. And we’re playing in New York in October, so we’re going to

debut it then. We’re going to be at Smoke, and reintroduce Nouveau Swing.

Donald Harrison, Jr. ‘Nouveau Swing’

Donald grew up in New Orleans in a family of musicians and creative people, studied with the great jazz teacher Alvin Batiste at Southern University, and then at Berklee School of Music in Boston.

Following Charlie Parker’s motto “If you didn’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn,” he set out to meet and play with the greatest jazz musicians he could, and made the experiences a part of himself. In the 1980s he and fellow New Orleanian Terence Blanchard worked with the great Art Blakey, and he also got the opportunity to work with more of his idols, including Miles Davis, and musicians who performed alongside John Coltrane and Charlie Parker.

And it’s now part of his life’s work to share that level of experience with young musicians, including the high school-age players at the Tipitina’s Intern Program in New Orleans.

This special performance was recorded live by New Orleans Calling for this program: Donald performing with bassist Max Moran, drummer Joe Dyson, piano player Shea Pierre, and guitarist Detroit Brooks at the historic Basin St Station.

Find out more about Mr. Harrison on a recent episode of WWOZ's New Orleans

Calling:

neworleanscalling.wwoz.org/donald-harrison-jr-you-have-to-live-it/

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2003/jan/03/jazz.artsfeatures

Donald Harrison, Kind of New

also reviewed Donald Harrison, Real Life Stories / 4 stars (Nagel Heyer)

If a recent flurry of promotion by the British Candid label helps win the 42-year-old New Orleans musician Donald Harrison a wider reputation (one more in tune with the soulfulness and streaming fluency of his alto-sax playing), it wouldn't be before time. Kind of New is the tribute to Miles Davis that Harrison vivaciously played live in London last November, and the earlier Real Life Stories features six originals plus three classics: Sonny Rollins's Oleo, Dizzy Gillespie's A Night in Tunisia and Paul Desmond's Take Five. The former disc might appeal more for the iconic familiarity of its repertoire (Miles Davis's 1960 Kind of Blue is the best-selling jazz album ever), but both discs hum with life.

If a recent flurry of promotion by the British Candid label helps win the 42-year-old New Orleans musician Donald Harrison a wider reputation (one more in tune with the soulfulness and streaming fluency of his alto-sax playing), it wouldn't be before time. Kind of New is the tribute to Miles Davis that Harrison vivaciously played live in London last November, and the earlier Real Life Stories features six originals plus three classics: Sonny Rollins's Oleo, Dizzy Gillespie's A Night in Tunisia and Paul Desmond's Take Five. The former disc might appeal more for the iconic familiarity of its repertoire (Miles Davis's 1960 Kind of Blue is the best-selling jazz album ever), but both discs hum with life.

Harrison always stood out for his combination of Charlie Parker-like attack, southern soul and bold, Coltrane-era angle on harmony. Real Life Stories emphasises what he calls "nouveau swing": a mixture of bop time, funk, Latin and reggae, with jazz always uppermost. A fine band, including a superb Eric Reed on piano, saves the disc from sounding like another stuttering, jump-cut, idiomatically indecisive post-bop formality. Harrison's Keep the Faith is a jubilant, jazz-gospel sermon, and of the standards, A Night in Tunisia is gentler and more whimsical than usual. Oleo features a scything alto solo bordering on free jazz, and Take Five is more sinewy than the Desmond/Brubeck hit version.

Kind of New is much straighter and very respectful. The title track cleverly blends the famous Milestones vamp with other celebrated Davis echoes from the period, and on the ballads teenage trumpeter Christian Scott mixes uptempo bravura with a muted-Miles type of impassioned murmur. Harrison's energy, agility and formidable clarity of purpose put his signature all over a furious alto solo on Freddie Freeloader. But this is a tribute disc for which the title is misleading, and Real Life Stories better balances Harrison's resourcefulness with some unexpected turns to the story.

For Donald Harrison’s 55th Birthday, a Downbeat Feature From 2002

Best of birthdays to the magnificent alto saxophonist Donald Harrison, who turns 55 today. For the occasion, I’m posting a feature piece that DownBeat gave me an opportunity to write about him in 2002. (The restaurant, unfortunately, went out of business a few years ago.)

* * *

The alto saxophonist Donald Harrison is particular — make that very particular — about his gumbo. After two decades in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene-Clinton Hill district, the 41-year-old son of New Orleans had never found a decent local version of his hometown delicacy, and a new spot on Fulton Street called Restaurant New Orleans has piqued his curiosity. There we sit on a crisp December afternoon, and as we wait for our bowls, he discusses Congo Nation, a smallish Mardi Gras Indian krewe of musicians that he founded a year ago and represents as Big Chief. Adorned in elaborately detailed, brilliantly colored regalia, this year’s edition — including iconic Crescent City drummer Idris Muhammad, masking for the first time at 60 — will parade, sing and dance through the streets of New Orleans during Mardi Gras festivities on February 12th. Harrison has been shopping for Muhammad’s costume, and will begin to sew it when he returns home to New Orleans a few weeks hence.

Black New Orleanians began to mask as American Indians in the 19th century, and the ritual chants and steps of this tradition descend in a more or less uninterrupted line to Congo Square, where African slaves were allowed to congregate and play the drums on Sundays. Harrison learned both the moves of the game and its cultural context from his father, Donald Harrison, Sr., himself a widely respected Big Chief of several tribes, including Creole Wild West, the Wild Eagles and the Guardians of the Flame. Mr. Harrison passed away in 1998, carrying with him a comprehensive knowledge of Mardi Gras Indian folklore, a keen sense of its African origins, and a clear vision of what it might contribute to contemporary culture. Erudite and charismatic, he not only walked the walk but talked the talk, able to communicate his message as effectively to the man on the street as in the halls of academe.

He imprinted the message on his son, for whom the spectacle of Mardi Gras Indian ceremonial is part and parcel of earliest memory. “I see it in the back of my head,” Harrison says as the gumbo arrives. “I was in my outfit, and I could see the other Indians running and their feathers moving up and down fast; I remember hearing the music and the singing. I grew up in it, and I know the inside stuff — how to sew, how to dance, how to sing, how to meet another chief, what to say, what to do. For me it’s the same sort of mindset as a jazz band, because you’re supposed to take the whole thing and sow your own fruit, tell your story within the context of your tribe. I’ve been in what we call a circle, and that takes you to another level. You’re in touch with all those elements — spiritual, warrior, the music, the art, the dancing, the fear, the courage. Every emotion is right there, and they’re all present at the same time. It ties together what you know now with things that were happening at the inception of everything.”

This having been said, Harrison digs into his gumbo, a savory roux infused with crab and shrimp. “I can relate to this,” he smiles. As we eat, let’s bring his story up to date.

Mr. Harrison bought Donald his first saxophone in elementary school. The aspirant tried it, liked it, put it away, then became serious for keeps at 14, learning second-line and traditional repertoire in Doc Paulin’s brass band and finding work in local funk bands. “Donald had a good feel for music from being around the Indians,” recalls outcat saxophonist-educator Kidd Jordan, his primary instructor during those years. “When he was playing by ear, before his technique was straight and he learned about changes, I thought he was going to come up with something in the style of Ornette Coleman. He was hearing some real creative things. I could hear a rawness that knocked me out.”

A few years later, Mr. Harrison put Charlie Parker’s “Relaxin’ At Camarillo” and “Kind of Blue” on the turntable, and converted his son to hardcore jazz religion. He enrolled at the New Orleans Center of Contemporary Arts (NOCCA), where such faculty as Jordan, Ellis Marsalis and Alvin Batiste taught such students as Branford and Wynton Marsalis, Kent Jordan, and the slightly younger Terence Blanchard.

“The first time I heard Donald, I was amazed at his level of maturity,” recalls Blanchard, a 15-year-old sophomore when Harrison was a senior. “He never had a problem getting around his instrument or with chord changes. You didn’t hear any young guys in the city playing like that on the alto.”

Several distinctive characteristics marked the Harrison sound when he arrived at Berklee School of Music — by way of Batiste’s program at Southern University — in 1979. His technique featured a seamless five-octave range and fluid fingering, as though the saxophone were an extension of his arm, while his style blended the grand harmonic partials of John Coltrane, the soulful oomph and precise articulation of Cannonball Adderley, and phrasing that recalled the fleet rhythmic displacements of Charlie Parker. “Donald had a freeness to his playing that was beyond the bebop thing,” says Blanchard. “He had so much ability to go in different directions that you could hear him changing his mind in the middle of his solo.”

Spending as much time in New York as Boston, Harrison sat in at every opportunity, landing a gig with Roy Haynes and — at Miles Davis’ instigation — buffaloing a Fat Tuesday’s bandstand occupied by Freddie Hubbard, George Benson, Kenny Barron, Ron Carter and Al Foster. Elders and peers took notice; in 1982, Branford Marsalis recommended his homie to Art Blakey for the Jazz Messengers sax chair. Until 1986, Harrison and Blanchard — who in 1982 released New York Second Line [Concord], debuting Harrison’s penchant for framing modern jazz with second line and Mardi Gras Indian rhythms — played alongside each other in a dynamic Messengers unit. When it was time to cut the cord, the tandem combined their surnames and signed a three-album contract with Columbia.

“Unless you’ve done something, you won’t think of it,” Harrison remarks, gently daubing hot sauce over a second course of lightly fried catfish. “I can tell a story from being an Indian. I hear guys doing second-line music who were totally against it initially, so I know our music influenced them or turned them around to think differently.”

“New York Second Line sounded delightfully strange to me when I was in high school,’ says pianist Eric Reed, 31, who produced and performed on much of Real Life Stories [Nagel-Heyer], one of three Harrison-led recordings due for 2002 release. “It became apparent to me that a new sound was taking place. The way Donald and Terence were interpreting their New Orleans influence was profound and amazing; on Nascence [Columbia] the way they had Ralph Peterson incorporate the second line into an updated backbeat, syncopated-offbeat feeling was nothing short of genius. They did everything that Wynton’s group was doing with Branford and Tain, except, again, they made the New Orleans core of it so hip! — and they were doing it before Wynton had decided it was hip to do. The music was accessible and felt great because the groove was so strong. There was nothing pretentious about it, just two young guys who were playing their experience, saying whatever it was they needed to say through their instruments, and they didn’t feel a need to intellectualize or over-explain the process.”

“Donald functioned wonderfully in Art Blakey’s band, but you could hear he wanted to do his own thing,” Blanchard says. “Our band seemed to be more of a perfect fit for him, because it was truly a workshop, and he could work on his concepts. He was always trying to mix things, compounding different rhythms on top of each other or playing in different registers simultaneously in a pianistic manner, with a melody in one register and an accompaniment in another. He had a big influence on my sound.”

In 1989 Blanchard — then developing a new embouchure and finding opportunities to write film music — left the partnership, a circumstance Harrison describes as “messy, but no hard feelings.” Partly for financial reasons, the altoist retreated to New Orleans, and soon was masking with his father’s tribe. Fortified by experiences garnered from a decade traveling the world and invigorated from immersion in the ’80s Brooklyn scene, where Reggae, Soca, Calypso, Haitian, Salsa, Go-Go, Hip-Hop and various African musical and dance styles coexisted and intermingled, Harrison reconnected with his roots from a mature perspective.

“I went out with my father and the Indians at Mardi Gras, and a light switch went on inside my brain,” Harrison says. “I started hearing the swing ride cymbal pattern that Art Blakey and Papa Jo Jones played inside of the African rhythms that the tambourines and drums were playing. Mixing the Indian rhythms with the swing beat led me to put funk and reggae rhythms with the swing beat, which I call Nouveau Swing.”

Joined by his father, Dr. John, Indian percussionist Howard “Smiley” Ricks, and jazz youngbloods Carl Allen and Cyrus Chestnut from the second iteration of Harrison-Blanchard, Harrison presented his hybrid concept on Indian Blues [Candid], a 1991 classic that links “Two Way Pocky Way” to “Cherokee.” The following year, trumpeter Brian Lynch, a close friend and fellow Messenger alumnus, recruited Harrison into Eddie Palmieri’s Salsa-Jazz ensemble.

“Eddie plays from a dance perspective, he knows how to write rhythms so everything is in place, and listening to that music every night deepened my understanding,” Harrison states. “I had to develop techniques to make slides and smears on the saxophone, and learn to play the rhythms in the right clave. The rhythms were natural for me; I always knew how to dip and dive into them even if I didn’t know the specifics. But Eddie helped me to be able to speak in that music, and it carries over to what I write and play now.

“If I’m writing, say, a second line song, I know the dance, what my feet and shoulders are doing to lock up to the different rhythms of the drums. If you listen to the drummers of the Samba and look at the feet, you know it’s matching up. Certain things interlock in Classical music, too. Miles Davis told me, ‘You hear something; to make it yours, just change it up a little bit.’ It is a language, and you can change the language and add different words. I hear the kids in Brooklyn adding new words to the English language all the time! ‘Whattup, Ma?’ They’re saying hello to a woman. They keep changing, and always know what they’re saying. You can change the music, too; the traditional part is making sure everything matches up. When you write from that perspective, it’s always locked in.”

Harrison demonstrates his point on Real Life Stories,” his fourth melody-rich document of Nouveau Swing since 1996. He’s worked with bassist Vicente Archer and drummer John Lampkin — both “young guys who understand the modern texture and can play it in the context either of a jazz band or a dance band” — for several years, and each is intimate with Harrison’s fine-tuned, elegantly worked-out grooves. The altoist plays with relaxed abandon and perfect time, soaring soulfully through the attractive, gospelized “Confirmation” changes of “Keep The Faith,” spinning a sinewy statement over a funky Latin feel on “Night In Tunisia,” playing with the harmonic contours of “Oleo” as though engaging in advanced mathematics. There’s a tinge of barely restrained wildness in his tone, evoking memories of ’80s flights that distinguished Harrison’s tonal personality from his peer group.

“I used to get dogged by the critics and some musicians,” Harrison recollects. “I wasn’t inside enough for the mainstream players and I wasn’t out enough for people who liked avant-garde. But I know my peer group listened to the records with Buhaina and Terence; a lot of young saxophonists then were quoting my solos without even realizing it. I’m comfortable with what I’m doing now; I’m getting back to the way I thought when I was 19, before I began to listen to people and worry about what they said. Once I started listening to Bird, I took the approach that this music is evolutionary, which means that in order to understand it and be a master, you have to study the whole history.”

Harrison spears a final forkful of catfish. “Each person is unique,” he concludes. “The beauty of jazz is to find the things that are truly you, tell a story, and touch people. That’s why I say it’s all about love. I enjoy going out in this world, watching people, being around people, seeing the joy that what we do can bring to them. Besides all the intellect and high thinking that we put in the music, when it’s all said and done, what do you feel?

“I was never trying to be the greatest. I always felt that if you could be one of the cats, you did a great job, because the cats were so great. We do the best we can and keep moving on. Like Art Blakey used to say, ‘Light your candle and hope that somebody will see it.'”

Saxophonist-composer Donald Harrison Jr. expands musical spectrum with Quantum Jazz

'It's like quantum science with soul," says alto saxophonist and composer Donald Harrison Jr. about his new musical concept − Quantum Jazz − set for unveiling at Symphony Space on Friday.

"Because I come from so many places, it hit me: I don't have to play or

think of music just in terms of time and harmony. The starting point of

a phrase, or of the chords, can be anywhere in time. We're no longer

constrained by downbeats. You can shift the meter at any point. It opens

up more spaces for time.

"And instead of playing through the

harmony as you do in bebop, you can play across a series of changes,

slashing across the chords.

"Imagine that you're at a park, with sidewalks around it. Walking from corner to corner, that's the normal way. But I've decided to cut across the park. I don't have to go on the sidewalk anymore. Yet I'm still getting where I need to go."

The New Orleans native, now 51, lived in New York early in his career, playing in master drummer Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers with his homeboy Terence Blanchard.

In 1984, Harrison and Blanchard released "New York Second Line," a song

Harrison wrote to capture New Orleans music in a modern context.

Since, he has played with other legends − Roy Haynes, McCoy Tyner, Eddie Palmieri, Jack McDuff and Ron Carter,

to name a few − and tapped into a plethora of genres, from

straight-ahead jazz, New Orleans R&B, pop, funk, smooth jazz, and

even hip hop. Harrison calls his musical gumbo Nouveau Swing.

When Harrison says he comes from many places, he means it.

"I use Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and even Louis Armstrong as my role models. They learned from the masters before them, and extending that. I think it's important to know as much as you can before trying to extend the tradition. I want the whole spectrum of the music in what I present, from when it started here in New Orleans."

He's also a Katrina survivor. "I was in New Orleans when it hit.

Mortality ... you realize that you might not make it. All life

intensified: the music, the beat, the sun, the cold. Things you took for

granted mean so much more. It gives you focus. And every day is not

promised, so you learn to take things as they come."

When the

opportunity to consult on the award-winning HBO drama "Treme" came, he

took it. Two characters are based on Harrison: the trumpet player

Delmond Lambreaux and his father, the bass playing carpenter Albert Lambreaux, chief of a Mardi Gras Indian tribe.

Harrison Jr. is the Big Chief of the Congo Nation, following in his late father's footsteps. Harrison Sr. was a folklorist and the Big Chief of several tribes during his lifetime. "The tribes keep the Indian and Afro-New Orleans culture alive through rituals − drumming, dancing and call-and-response chants − and with music inspired by Africa, because it was the music from Congo Square, where they allowed Africans to play drums in the 19th century," he explains.

In 1991, Harrison recorded "Indian Blues" with Dr. John. Harrison wears

full Indian tribe regalia on the cover of the recording, which was

inspired by an experience reenacted on "Treme" during a Mardi Gras

parade.

"I was out with my father, and while they were playing

drums he was singing a chant, 'Shallow Water.' In the middle of it I

heard Art Blakey swingin' on the drums. And I said wait a minute, these

beats go together!"

On Friday, the first half will feature

acoustic jazz, the second, "some funky New Orleans music, and a little

hip hop." Most of the musicians performing with him at Symphony Space

have been students: Christian Scott, trumpet; Joe Dyson, drums; Max Moran, bass; Zaccai Curtis, piano; and Detroit Brooks, guitar.

Harrison says that the late Notorious B.I.G., Biggie Smalls, also studied with him, from about 13 to 18. They were neighbors in Brooklyn. "Chris was a very intelligent young man. He'd come over my house all the time when I wasn't on the road. He played hip hop for me, I played jazz and R&B for him. I guess we influenced each other like that.

"We became friends. He'd ask me: What is it like to be a musician?"

Harrison answered that and more. He advised Biggie to work on his diction, so that every word could be understood. He suggested that Biggie wear suits, and rap with a deeper voice.

"The next thing we worked on," remembers Harrison, "was understanding rhythm from the snare of a bebop drummer. If you listen to the way he rhymes, some of it is based on the rhythms of Max Roach, Kenny Clarke and Philly Joe Jones."

Harrison has benefited from the tutelage of masters, so he reaches back to younger generations to bring them along, "to give them real choices," he says.

Now he's ready to put his stamp on the tradition.

"To me, Quantum Jazz and Nouveau Swing are the crossroads where jazz tradition meets soul, science and today's dance music. It's jazz for mind, body and soul. I call it: roots to infinity."

AN EVENING WITH THE BIG CHIEF DONALD HARRISON Peter Jay Sharp Theatre at Symphony Space, 2537 Broadway, at 95th St., Friday, April 27 at 7:30 p.m., (212) 864-5400.

https://music.osu.edu/events/jazz-festival-master-class-donald-harrison-guest-saxophonist

Jazz Festival: Master Class with Donald Harrison, guest saxophonist

Donald Harrison presents a master class, which is free and open to the public. He is a featured guest artist in tonight's Jazz Festival headline concert, Charlie Parker with Strings.

Harrison, born in New Orleans, grew up in an environment saturated with the city’s traditional brass bands, Afro-New Orleans culture, modern jazz, R&B, funk, classical, world and dance music. He has deep roots in a new American style of African culture developed in New Orleans. He created “Nouveau Swing,” a style of jazz that merges it with modern dance music. He also combined jazz with Afro-New Orleans traditional music on his critically acclaimed and influential albums Indian Blues and Spirits of Congo Square. Harrison has performed and recorded in a variety of genres with numerous artists including Art Blakey, Roy Haynes, The Cookers, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Lena Horne, Ron Carter, Billy Cobham, Eddie Palmieri, Jennifer Holiday, Dr. John, Guru’s Jazzmatazz, McCoy Tyner, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Digable Planets, Notorious BIG, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra and The Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra. An evacuee/survivor of Hurricane Katrina, Harrison had a prominent role in Spike Lee’s HBO documentary, When the Levees Broke. He also appeared and co-wrote the sound track for Academy Award winning director Jonathan Demme’s feature film, Rachel’s Getting Married. Aspects of Harrison’s life and music are chronicled with two characters in David Simon’s groundbreaking HBO series, Treme. Harrison recorded Quantum Leap, which melds cutting-edge jazz with New Orleans funk, connecting the past to the present with jazz music that transcends boundaries. He recorded his first classical orchestral composition, Congo Square Part I with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. Donald Harrison is co-founder and artistic director of the Tipitana’s Intern Program, an after-school program for high school students interested in pursuing music as a career. Harrison's awards include France’s “Grand Prix du Disque” (twice), Switzerland’s “The Ascona Award,” Japan’s Swing Journal “Alto Saxophonist of the Year,” The Jazz Journalist Association’s “A List Award,” 2012 New Orleans Civic Award, 2007 Jazziz Magazine’s “Person of the Year,” the Big Easy Music Awards “Ambassador of Music” and a Downbeat Magazine’s Alto Saxophone Poll winner. He was also a 2006 resident at William and Mary College, a 1995 “Meet The Composer” recipient and a 2012 Grammy nominee.

Events Filters:

https://www.oregonmusicnews.com/donald-harrison-review

Donald Harrison: The Big Chief plays at Jack London Revue 11/19/2017

by Michael Shoehorn Conley

The Portland saxophone player listens and reacts to the New Orleans sax master.

Jack London Revue was packed when I arrived. I had deliberately skipped the opening act, wanting to get something so distinct fresh in my ears. I soon ran into some musician friends and settled in. I had first heard of Donald Harrison decades ago from reading Downbeat, and was intrigued by his self-portrayal on the HBO series Treme, where he was presented as a cat who could play "modern" and also stomp the "2nd line" funky street jazz which is arguably the basis for the second wave of popular music that emanated from the Crescent City- rock & roll.

The show was notable for the variety of styles the band was able to pivot between, with Harrison's tone and articulation as varied as the tempos and grooves. As a saxophonist myself, I had to look twice to see whether he had separate mics for the funky tunes and the straight-ahead stuff. It was almost like he had different EQ settings for the various styles.

After some introductory remarks, Harrison opened with a funky/fusion original titled "Castle of the Headhunters" that had several distinct sections and a driving beat; the saxophonist unleashing squalling flurries of notes once he got into it. He followed with the bebop staple "Groovin' High" by Dizzy Gillespie, including the intro and other arranging touches from the original recording with Charlie Parker.

Next was a blazing "Cherokee", which Harrison prefaced with an explanation to the effect that it is very fast, and very hard, and that they wanted to establish their bona fides in the speed chops department, and "once we do this we will not play this fast again- because its hard"! The piano player ripped on this and there was a cool "shout chorus" which gave the drummer some awesome fills at approximately 300 bpm.

What came next was Bechet's arrangement of Joplin's "Maple Leaf Rag", which was as stunning and exquisite in execution as it was familiar to students of jazz history and old-school rags- with the essential breaks in the rhythm for the soloists to fill. The whole rhythm section was excellent on this tune, and keyboardist Zaccai Curtis got to throw down some fine left hand power strokes, old-school- with the leader's timbre and tonguing again folded into the style with flawless aplomb.

The journey continued to reflect the "Spanish Tinge", wherein pianist Curtis performed a florid intro with enough hints of rock-hard rhythm to engage everyone's interest. Once the tune was fully underway, the young drummer, aged 22, gave ample testimony to the efficacy of a standard drum set in laying down a hot Latin Jazz groove without traditional percussion. The descarga over the montuno vamp at the end gave Harrison another opportunity to exhibit his powerful rhythm chops and emotive fire from the altissimo range of the alto saxophone. I did not catch the title of the Latin number.

Closing the first set with a vocal on the New Orleans favorite, "Iko Iko", Harrison casually assumed his mantle of "Big Chief" which he apparently inherited from his father in the Mardi Gras Indian tradition. The audience was invited to sing along during this bit.

On each of these tunes, so stylistically distinct, the band was on fire. Curtis's piano solos were technically impressive and grooved relentlessly, and the drummer had plenty to say without obvious solos, feeding off of Harrison and locked in with his partner in the bass chair, who skillfully alternated between acoustic and electric instruments.

The second set started with an impromptu blues in F, with Harrison vocally channeling the late Clark Terry, "mumbling" the licks and singing a low-key, humorous lyric about a whisky-loving female. The band here chipped in behind the leader with an understated, old-school feel, and impressed us again with the depth of their command of yet another stylistic bag.

Harrison announced they would do some "soul music" next, proceeding with a medley of originals that would not have been out of place in a set by the late Grover Washington. Again, Harrison adjusted his tone and attack to the stylistic parameters and somehow sounded different while maintaining his identity on the horn.

They did Roberta Flack's 70s hit "Feel Like Makin' Love" with an interpretive panache that did not distract the audience from chiming in on the chorus. The final number was also a vocal on another Mardi Gras favorite- " Hey Poky Way", and the crowd ate it up. Donald Harrison and his band masterfully held the audience in rapt attention with a satisfying mix of hard-core jazz chops and rollicking good-time party tunes.

https://www.nola.com/entertainment_life/festivals/article_b425ab1e-53cf-59d2-ab3b-177936938d0a.html

'A one-man jazz festival' - Donald Harrison Jr. a complex keeper of local culture

Donald Harrison performs at the New Orleans Jazz Fest, Sunday, April 25, 2010.

Donald Harrison Jr.'s set at 2009's New Orleans Jazz Festival presented by Shell was like Jazz Fest in a box.

He opened with hard-swinging contemporary jazz executed by a deft, astonishingly young-looking band.

Then Harrison brought on venerable Dr. Lonnie Smith -- born in 1942, he was Downbeat magazine's "Top Organist of 1969" and is still a renowned master of the Hammond B3 -- for some delightfully weird organ sounds.

Then Harrison put down his saxophone and reappeared in full Mardi Gras Indian finery for a pounding mini-set of street-parade music and chanting.

"I travel through so many different styles of music, it's all part of me," Harrison said in a recent interview. "My friend once said, 'You're a one-man jazz festival.' That's what lives in my heart. It sort of helps me to be able to mix genres, especially when I'm playing jazz."

Expect similar depth and breadth from Harrison when he takes to the Congo Square "My Louisiana" stage today at 1:15 p.m. at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival Presented by Shell.

Jazz Fest attendees who find their way to his set will also see a formative influence on "Treme," the new HBO drama.

Pieces of two principal characters in the show are drawn from Harrison's life.

The son of Guardians of the Flame Big Chief Donald Harrison Sr., Harrison has made his way in the wider world of jazz beyond New Orleans much like Delmond Lambreaux has in the series. (That was Harrison on the bandstand with Lambreaux in the New York nightclub scene in the series' premiere episode).

As Big Chief of the Congo Nation, Harrison is a committed keeper of the Mardi Gras Indian flame in New Orleans, deeply informing Delmond's father, bassist-carpenter-Indian chief Albert Lambreaux.

Part of a team of locals and consulting on or serving as muses for the series -- including musician/disc jockey Davis Rogan (the model for the Davis McAlary character) and chef Susan Spicer (part-inspiration for Janette Desautel) -- Harrison first met "Treme" co-creator David Simon when Simon was still making episodes of his Baltimore-set HBO series "The Wire."

After Hurricane Katrina, Simon placed New Orleans music on "The Wire" soundtrack, including a song by Harrison. The relationship developed from there.

"He was just observing and, I guess, making mental notes and seeing what I was doing and how I was doing it," Harrison said. "That's what it seemed like to me. We did sit down to lunch once, but it wasn't like a formal interview. We were just talking, a casual conversation. But maybe he was leading that casual conversation. He's quite a smart guy."

The one significant difference between Harrison's story and Delmond Lambreaux's is Harrison's comfort with the footsteps he literally walks in as a Mardi Gras Indian.

"I think he is very comfortable with the Indian tradition," Simon said. "He doesn't feel any conflict between his New York endeavors and his sense of being a New Orleanian.

"It was much more interesting to us (for the Delmond character) to feel that father-son dissonance that a lot of young men have growing up. You want to stand in your own light."

Added Harrison: "It's loosely based on how I came into being as a musician. During this stage in his development, he doesn't like New Orleans that much, which is something that is not part of my character. I've always loved New Orleans music. I know why they're doing it."

In his role as consultant for the series, Harrison has reviewed scripts and worked closely with actor Clarke Peters, whose amazing performance as Albert Lambreaux has arrested viewers' attention and appears a contender for an Emmy Award nomination.

"He's a great actor and a great person and he's a natural bass player, which was surprising to me," Harrison said. "He really understands the nature of the upright bass. I thought he'd been playing for years, and he told me he's only been playing since the series started, which kind of blew my mind. He really understands what that instrument's supposed to do."

Harrison said Peters has worked hard to capture an Indian chief's almost-aristocratic mien.

"I think what the series has picked up on is the seriousness that people who do that have," Harrison said. "They maintain the culture and the spirituality of it, and the transcendence from everyday life. Those are some of the things I think Clarke really brings out. And the regal nature of being a big chief."

Peters credited Harrison with letting him in on elements of the Indian culture that only an insider could know.

"I've gleaned that there's this tradition going on, and the remnants of it may not be in people's intellect, but it's in their hearts, it's in their dance moves," Peters said. "You have to be here to really understand what it is. It might look wonderful and eccentric and fun, but there are layers that are a lot more profound than just what we derive."

Peters added he's also learned a lot of very specific choreography and attitude from Harrison.

"I've gotten a lot of moves from Donald," Peters said. " 'Hold your head up, you're a chief.' 'Don't put your spear on the ground, because that means war.'

"I say, 'But it's just a stick,' and he says, 'Don't you dare think that's just a stick.'

"Donald's been really, really helpful."

Added Simon: "It's not easy on the consultants. There are moments that character has that are unlike what he knows to be indicative of his late father and other chiefs. He has to sort of hold his breath and go, 'This is fictional. This didn't happen.' But at the same time, (the consultants) provided us with a lot of interior logic in order to create the characters."

Harrison sees "Treme" as an opportunity to educate the world beyond New Orleans about underappreciated elements of its culture. He also believes that "Treme" could play a role in helping preserve that culture.

"What the show is doing for me is letting the world know that something is going on down here in New Orleans, and it's one of the root cultures and music styles that have influenced the whole world from the beginning," he said. "I think it's important to let the world know that we can't throw this culture away.

"A tree without roots is not going to survive. This is a strong foundation that much of our art and culture is based upon -- not just New Orleans, but the world. This is what we feed off of."

Big Chief Donald Harrison - Full Set - Live from WWOZ (2019)

Donald Harrison Jr. performs "Cool Breeze" on WBGO

Donald Harrison Jr: "Nouveau Swing" - from WWOZ's Basin St ...

Donald Harrison - The Tropic of Cool

On Congo Square and the Roots of Jazz

"The Big Chief On Bird" The Donald Harrison Interview