SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER THREE

DONALD HARRISON

(October 2-8)

CHICO FREEMAN

(October 9-15)

BEN WILLIAMS

(October 16-22)

MISSY ELIOTT

(October 23-29)

SHEMEKIA COPELAND

(October 30-November 5)

VON FREEMAN

(November 6-12)

DAVID BAKER

(November 13-19)

RUTHIE FOSTER

(November 20-26)

VICTORIA SPIVEY

(November 27-December 3)

ANTONIO HART

(December 4-10)

GEORGE ‘HARMONICA’ SMITH

(December 11-17)

JAMISON ROSS

(December 18-24)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/ben-williams-mn0002686289/biography

Ben Williams

(b. December 28, 1984)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

Jazz bassist Ben Williams is a forward-thinking musician who crosses easily between straight-ahead, funk, and gospel-influenced jazz. A native of Washington, D.C., Williams graduated from the Duke Ellington School of Music before studying with renowned bassist Rodney Whitaker while earning a B.A. in jazz studies at Michigan State University. He is an in-demand sideman and has performed with a veritable who's who of jazz, including Wynton Marsalis, Roy Hargrove, Mulgrew Miller, Terence Blanchard, and others. Williams is also a regular member of Stefon Harris' hip-hop-influenced Blackout ensemble and leads his own group. In 2009 Williams won the prestigious Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition and subsequently signed a recording deal with Concord Records. Two years later, he released his debut solo album, State of Art. In 2015, Williams delivered his sophomore full-length album, Coming of Age, which featured a '70s fusion and R&B influence and included guest appearances from trumpeter Christian Scott and vocalist Goapele.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ben_Williams_(musician)

Ben Williams (musician)

|

| Ben Williams |

Ben Williams (born December 28, 1984, Washington, D.C.) is an American jazz bassist.

Biography

Ben Williams began playing bass at age 10, was raised in the District of Columbia, and graduated from Duke Ellington School of the Arts. He received a Bachelor of Arts in Music Education from Michigan State University and a Master of Music in Jazz Studies at the Juilliard School.

In 2009, he won the prestigious Thelonious Monk International Jazz Bass Competition as judged by Ron Carter, Charlie Haden, Dave Holland, Robert Hurst, Christian McBride, and John Patitucci.[1] The honor included a recording contract with Concord Records through which he released his debut album, State of Art, in 2011, featuring saxophonist Marcus Strickland, guitarist Matthew Stevens, pianist Gerald Clayton, drummer Jamire Williams, and percussionist Etienne Charles. His album Coming of Age, was released in April 2015 featuring sidemen Marcus Strickland on tenor and soprano saxophones, Matthew Stevens on electric guitar, Christian Sands on piano, and John Davis on drums.[2]

In August 2020, Williams contributed to the live streamed recording of the singer Bilal's EP VOYAGE-19, created remotely during the COVID-19 lockdowns. It was released the following month with proceeds from its sales going to participating musicians in financial hardship from the pandemic.[3][4]

Awards and honors

Williams was a member of guitarist Pat Metheny's Unity Band, which won Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Album for Unity Band in the 2013 Grammy.[5]

Williams was introduced as one of the “25 for the Future” by DownBeat magazine in 2016.[6]

Discography

As leader

As sideman

Year recorded Title Label Personnel/Notes

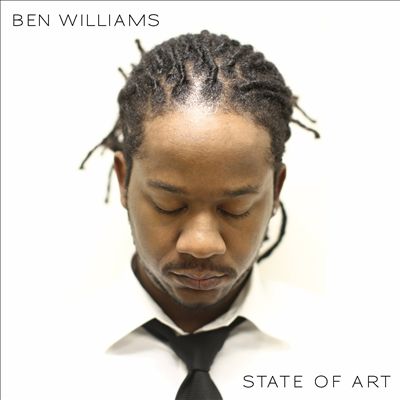

2011 State of Art Concord Quintet, with Marcus Strickland (saxophone), Matthew Stevens (guitar), Gerald Clayton (piano), Etienne Charles (percussion), and Jamire Williams (drums

2015 Coming of Age Concord Quintet, with Marcus Strickland (tenor and soprano saxophones), Matthew Stevens (electric guitar), Christian Sands (piano), and John Davis (drums)

2020 I Am A Man Rainbow Blonde Records Various artists, with Ben Williams (voice and bass), Kris Bowers (piano, keyboards), David Rosenthal (guitar), Jamire Williams (drums), Justin Brown (drums), Bendji Allonce (percussion), and special guests Year recorded Leader Title Label

2009 Stefon Harris Urbanus Concord

2010 Jacky Terrasson Push Concord

2012 Pat Metheny Unity Band Nonesuch

2014 Pat Metheny Kin Nonesuch

2016 Pat Metheny The Unity Sessions Nonesuch

2017 Steve Wilson Sit Back, Relax & Unwind J.M.I. Recordings

https://jazztimes.com/features/profiles/ben-williams-world-is-growing/

Ben Williams’ World Is Growing

With his latest album, the bassist is making a wider statement to a larger audience

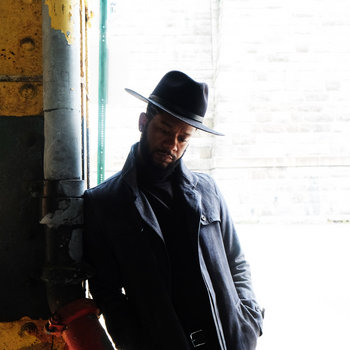

If the Hamilton isn’t sold out, it’s close.

It’s the night after Christmas in Washington, D.C., a city that famously empties for the holidays. Yet there are certainly enough people—of all ages, all genders, and all ethnicities, though a majority are African-American—to pack the 600-capacity basement venue a few blocks from the White House. No empty tables are in view, and the standing room area by the back bar is filling up fast.

The performer filling the seats at this ordinarily tough-booking time and place? Ben Williams, the jazz bassist and native Washingtonian who plays the Hamilton every year at this time. It’s a combined Christmas and birthday celebration (Williams will turn 35 two days after this concert), and family, friends, mentors, colleagues, and plain old fans have made it one of the District’s seasonal customs to turn out in droves.

This time out there’s yet another dimension to the performance. “I have a new album on the way,” he announced to cheers from the crowd. “I’m so excited to share this new music with you guys. The new album is titled I Am a Man, which of course comes from the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ strike … I wanted to address social issues in the world that was going on around me. It’s been somewhat of a journey, exploring a lot of new musical territory.”

Indeed it has. Williams brandishes not the upright wooden bass on which he made his reputation (though there is one on stage), but an electric bass guitar. He plays unabashedly funky, albeit lyrical, lines that immediately evoke his all-time hero, Prince. The real surprise, though, is this: He sings.

Williams wields a winning tenor voice, higher than his smooth baritone speaking voice and studded with R&B inflections. He starts with a dark, sexy version of Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You” and continues into a medley of Prince’s “If I Was Your Girlfriend” and “When Doves Cry,” on which he duets with Grammy-winning singer/songwriter Kendra Foster, and I Am a Man’s “If You Hear Me.” It’s a brand-new instrument for Williams—certainly this crowd hasn’t heard it before—and he’s remarkably good.

Still, the audience here might thrill at anything Williams does. They applaud politely at monster solos by saxophonist Chelsea Baratz, keyboardist Allyn Johnson, and guitarist David Rosenthal, but roar at everything the bassist/vocalist puts down. Naturally, he plays into it. “We just have one rule, just one—you have to have a good time,” he announces. “Is everybody good with that?” They respond accordingly.

To most of the jazz world, Williams is a talented, hard-working musician with an impressive arc of development; he commands respect from the likes of Christian McBride and Pat Metheny. “One of my favorite people,” says Metheny, who employed Williams in his Unity band (under whose auspices the bassist shared in a 2013 Grammy award). “He brings a level of professionalism that is increasingly difficult to find, even as there are more and more good players out there.”

In D.C., though, he’s something else again: a hometown hero.

That hero status isn’t restricted to the concert. Two days later, as we chat over lunch at a restaurant near his old neighborhood, a music lover approaches our table. “I’m thoroughly gobsmacked just to be so close to you!” he tells a blushing Williams. “Keep doing what you’re doing.”

He’s been doing it since childhood. Williams grew up in a family that loved music. His mother Bennie worked for the late U.S. Representative John Conyers (D-Mich.), the Capitol’s most outspoken lover and patron of jazz; young Ben was exposed to the music early on. But the Williamses also collectively loved Prince. “We had Purple Rain on VHS and I used to watch that all the time when I was a kid,” the bassist recalls. “He was really the reason I wanted to become a musician. In fact, I wanted to play guitar like Prince, and when I got to middle school [where school bands began in D.C.], the guitar seats had already filled up so that’s how I ended up playing bass.”

Williams didn’t treat it like something he had to settle for, though—he worked hard. When he was out of the classroom, he took lessons with every local musician who would give them. By the ninth grade, when he passed an audition for the Duke Ellington School of the Arts, he was deeply immersed.

“He was on his way,” recalls Davey Yarborough, then director of Ellington’s jazz program. “As a matter of fact he had taken piano lessons too, so he was on piano and bass. But what most impressed me was that his mother eventually became the parent group president, and every time I called her house, I would hear him practicing on either bass or piano in the background. And it was amazing to me, how studious he was.” That studiousness reaped rewards: Just before his 2002 graduation, Williams placed second in the student competition at Maryland’s East Coast Jazz Festival.

He matriculated at Michigan State University, where he studied bass with Rodney Whitaker, then enrolled in the Master of Music program at the Juilliard School in New York. Not surprisingly, Williams was soon juggling his coursework with gigs; he played some dates with Terence Blanchard, joined pianist Jacky Terrasson’s trio and vibraphonist Stefon Harris’ quintet Blackout. He had also forged a relationship with tenor saxophonist Marcus Strickland, who’d been hearing his name. “I finally got to hear him in person, and I understood why his name was floating around so much,” Strickland says. “He’s an incredible musician; I started playing trio and he was the first guy that came to mind.”

Williams was still maintaining the balancing act (though almost finished) when, in October 2009, he won what was then the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Bass Competition. “The final was on a Sunday night,” he recalls. “I had to go to class the next day.” He finished his master’s in December.

Victory in the Monk Competition rerouted Williams’ career. Included in the prize was a contract with Concord Records; for that purpose, he put together the six-piece Sound Effect, then got to work providing something for them to play. “That was really when the beginning of my career as a bandleader started,” he says. “And it definitely got me into writing a lot more, which is something I always wanted to do. Getting that opportunity allowed me to explore.”

The resulting State of Art, released in 2011, was the work of a musician still unsure of himself as a composer and leader. But it did have the beginnings of a concept. A child of the ’80s and ’90s, Williams brought an intuitive grasp of that era’s R&B and nascent hip-hop to his music. That vision would mature and deepen on his second album, 2015’s Coming of Age, becoming a full-fledged jazz fusion that also incorporated rock, funk, and go-go, the cousin of funk that is D.C.’s indigenous genre.

Along the way, Williams kept developing both his musicianship and his reputation. He continued collaborating with Strickland, who also played on Williams’ aforementioned albums; worked with pianist Eric Reed and trumpeter Marcus Printup; and accompanied vocalists Gretchen Parlato, Somi, and José James. When bassist Christian McBride couldn’t make some trio dates with Pat Metheny, he recommended Williams as a substitute; that led to his joining Metheny’s new Unity band in 2012.

“Anyone that has worked extensively in one of my bands would likely tell you that it is a pretty challenging gig,” Metheny says. “Folks have to be ready and able to play at a high level two-and-a-half to three hours every night, for sometimes 100 or 200 nights in a row, in a different city every day. No matter what, Ben was really able to hang with me every step of the way.”

As his experience broadened, so did his perspective. Williams, an African American who’s lived his whole life in cosmopolitan settings, was keenly aware of racial and other social-justice issues; he began orienting his own music—overtly, at least—in that direction on Coming of Age, with tunes like “Voice of Freedom (for Mandela)” and “Black Villain Music.” (The album came out in the wake of racial unrest surrounding the killing by police of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; its release was coincident with similar unrest in Baltimore.) In subsequent years, as societal problems became both more visible and more acute, it became clear to Williams that his art would have to engage with them full-on.

The project that became I Am a Man began germinating in the late summer of 2017, when Williams headlined the annual jazz concert at the Congressional Black Caucus’ Legislative Conference. “I did this program called ‘Protest Anthology,’ and it was the first project I did that had political and social commentary as the primary focus. So that got the wheels rolling.” Not long afterward, with politics still at the forefront of his thoughts, he saw 13th, Ava DuVernay’s documentary about race relations and incarceration.

“At the end of the film was an iconic photo from the Memphis sanitation protest, the one Dr. [Martin Luther] King had come to support when he was killed,” he says. “All these sanitation workers were holding up signs that said, ‘I am a man.’ A lot of times you see a protest where people have different signs saying different things, but in this case seeing everyone with the same sign … it was a powerful image. So that phrase just got stuck in my head.”

He began developing the idea, thinking about the nuances of that phrase. On the one hand, it affirmed his humanity and rights as a black man; on the other, it was a reminder that he was a complete human being, not easily reduced to outrage, a movement, or a slogan. The simple four-word sentence, “I am a man,” carried a tremendous load.

“I decided to make a presentation of my humanity and explore the complexities of being a black man in America—what it feels like day to day just to be that,” Williams says. “I just wanted to show that even though we’ve had this very complex experience in this country, we’ve always had to prove that we’re just human beings. But I wanted to do it in a way that was not clearly from a place of anger: We deal with the same things that every human deals with. Life, death, love, spirituality, addiction—all these struggles that are just innately human. But I wanted to explore how being black and being male adds to that complexity.”

Initially he conceived of it as an instrumental project; he would articulate the themes in his titles, then express them abstractly. It soon became apparent, however, that what he had to say was too specific for that. He was going to need to write songs: new territory for him.

The revamped concept would put his songs in the hands of various vocalists. One would be Kendra Foster, a singer/songwriter who’d worked with Parliament-Funkadelic and D’Angelo, winning a Grammy for her co-writing with the latter—which focused heavily on social-justice themes. “It was absolutely in my wheelhouse,” she says of the opportunity Williams offered. “He explained to me what the whole album was about and what he was trying to say, and I loved that it went completely direct, with no ifs, ands or buts: you know what we’re singing about. We also have this shared love of Prince, so we were on that vibe.” Foster became Williams’ co-writer on two songs; they duet on one of them, “Come Home,” which is both highly topical (about a mother’s all-too-frequent fear of her black son never coming home) and highly accessible—a stylistic homage to Prince, a pop song.

I Am a Man would ultimately feature a few other guest vocalists, including R&B singers Wes Felton and Muhsinah. Williams had hoped that José James, with whom he was touring heavily, would be the album’s big vocal star; that’s not how it worked out. “I played José a couple of the demos, and I was singing on them,” he says. “And he said, ‘That’s you singing? That sounds good. You should do that, bro.’ And I was like, ‘Sure, yeah.’ But once he put this idea into my head that I could sing these songs on my own, I started to write more with me singing in mind. I started to actually sing them on the shows, and I was just like, ‘Oh, wow. I guess I’m just gonna sing these songs now.’”

To his longtime associates, it was both surprising and unsurprising. “He called us in for this rehearsal, didn’t even tell us he was gonna sing, and then just got on the mike,” recalls Strickland, who plays on I Am a Man. “I couldn’t believe it at first, but then I was like, ‘Why not?’ Every now and then when I hear him singing along with songs in the car, when we’re on the way to a gig, I’m like, ‘Yo! He has a good voice!’ Him being out front like that, singing, is going to be an incredible adventure for him.”

“He’s evolving, just like he always has,” Yarborough

says. “He still has no fear; he’s taking calculated risks, but he’s not

afraid to step out. Introducing the singing thing, it’s going to

brighten his stage persona. He’s still got a whole lot more to give to

us.”

Among the new things Williams has to give is a reinvented stage persona—a natural outgrowth of his taking on vocal duties. At the Hamilton in D.C., another duet with Foster breaks down into a skit of sorts, with Williams remarking on the sound of footsteps. “It’s either Santa, or someone done broke into the crib,” he says with a funny smirk. “Grab the gun and the cookies, just in case.” Foster, who’s supposed to assume the role of the footstepping visitor, completely cracks up.

I Am a Man is his third album, but in a very real sense it’s also the debut of Ben Williams 2.0. He’s assumed a new creative direction, new collaborators, even a new instrument. If the subject matter isn’t entirely new, his focus and his treatment of it certainly is.

It may also be taking on new dimensions. The restaurant we’re having lunch in is part of a recent D.C. development; it leads Williams to muse about the consequences of gentrification, both in the District and in his adopted home of Harlem. “I know that the price of gentrification a lot of the time is culture and art,” he says. “I want to represent that. Do whatever I can do to remind all the newcomers that this is not just a hip urban playground, that there’s some serious culture that they need to understand.” It could be a preview of his next artistic dispatch.

“It has been great to watch Ben develop as an artist,” Metheny says. “To me, his new record is exactly the record I want to hear right now. … We need his voice in this respect. I look to him myself as a messenger as we go forward.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ben Williams

Benjamin James Williams is a native of Washington, DC. He also performs on electric bass and piano as well. His musical influence is rooted in various genres of music including jazz, hip-hop, R&B, gospel, and classical. Ben is a recent graduate of the Michigan State University School of Music where he majored in Music Education with an emphasis in Jazz, studying with Rodney Whitaker and Jack Budrow. He plans to pursue a Master’s degree in Jazz Studies at the Juilliard School. Ben has won several competitions and scholarship awards. He is a two-time winner of the Fish Middleton Jazz Scholarship Competition at the East Coast Jazz Festival; a two-time winner of the DC Public School Piano Competition; a 2002 recipient of the Duke Ellington Society Annual Scholarship Award. Most recently, Ben won first place in the 2005 International Society of Bassists (ISB) competition in the category of jazz. Ben has performed both nationally and internationally with such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Mulgrew Miller, Cyrus Chestnut, Ron Blake, Stefon Harris, Karreim Riggins, Hamiett Bluiette, James Williams, Bobby Watson, Winard Harper, Buster Williams, John Hicks, Anthony Wonsey, Me’Shelle N’degeocello, Gene Lake, Wycliffe Gordon, and Delfeayo Marsalis to name a few. He has also performed with opening acts for artists such as John Legend, Kirk Franklin, and Eric Roberson.https://downbeat.com/news/detail/ben-williams-righteous-vocal-power

Ben Williams’ Righteous Vocal Power

Ben Williams’ I Am A Man has been issued through Rainbow Blonde, a new label founded by vocalists José James and Taali and engineer Brian Bender. (Photo: Janette Beckman)

Ben Williams was completely mesmerized by 13th, director Ava DuVernay’s 2016 documentary about mass incarceration and racial inequality. The jazz bassist was especially intrigued by a still photograph depicting a 1968 strike by Memphis sanitation workers. In the picture, black union members are picketing on the city’s sidewalks, walking past a gauntlet of bayonets held by white National Guardsmen. Around each protester’s neck hangs a placard bearing this phrase in bold capital letters: “I Am A Man.” It became the title of Williams’ new album.

“After watching the movie,” Williams recalled, “I researched a little more, and realized that was why Martin Luther King was in Memphis when he got shot. The visual of this long picket line of all these men carrying the same sign reminded me of how we use hashtags today, how we all adopt a phrase to sum up how we feel.”

The photo conveys an intense level of dignity: The way the men walked in dark suits and fedoras re-

inforced the message on the signs they carried. Those four words distilled a long list of grievances—underpay, racism and working conditions—into a concise demand for recognition and respect as human beings. It was a demand the city’s government had been unwilling to meet.

“I wanted to address the social climate and deal with injustice,” Williams explained, “but I wanted to take another route and not come from a place of protest. I wanted to go into the minds and the spirits of the people who were protesting, to really deal with the humanity of those black men who had to remind society that they are men, that they are human beings. I wanted to dig into that phrase and what it means. What did it mean to them? What does it mean to me?”

The picket signs were a testament not only to the power of a union but also to the power of language. When Williams, 34, decided to make the struggle for equal rights the central theme of his third album, the bassist figured he would have to take a lesson from those signs and make language a major means of expressing himself. He would have to step forward as a singer for the first time in a recording studio.

Williams won the 2009 Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz International Jazz Bass Competition and had then, as a member of guitarist Pat Metheny’s Unity Band, cemented his reputation as one of his generation’s finest bassists. But with I Am A Man, he emerges as a lead singer. He’s asking listeners to shift their focus from his dexterous fingers to his unproven pipes.

“When I started doing this project, I was writing mostly instrumental tunes,” he said, “but I realized I could only express certain things with words. People may see you do one thing and they categorize you as that—but I don’t think of myself as one thing. I can’t say I ever imagined I’d be doing this, but when it started moving in this direction, I wasn’t afraid to go with it. This is the first time anyone, including my own mother, really has heard me sing.”

His initial idea was to compose instrumental music inspired by social issues (and he still hopes to release those pieces later in 2020), but Williams couldn’t keep lyrics out of his new project. He considered hiring established singers to handle the vocals. So, as he had in previous collaborations with vocalists, Williams created demos on his home computer, playing all the instrumental parts and singing all the vocal parts himself. But when he started playing the demo tracks for colleagues, he got an unexpected reaction.

“The first person who really heard these songs was José James,” Williams said. “I was on the road with his Bill Withers project, and we were just sitting around. I played Jose one of the demos, and he said, ‘You’re singing that song? You have a nice voice; you should sing more.’”

But Williams wasn’t ready to share his vocal talents. His own band had Chris Turner handling the singing, both on older songs and on songs from the new album. But one night, the bassist had just finished a new song and was aching to try it out.

“There wasn’t time to teach it to Chris,” Williams recalled, “so I said, ‘I’ll just try it.’ It was scary. It was one of those moments where you just take that plunge and jump off the cliff. ‘Don’t overthink it,’ I told myself. ‘Just go ahead and do it.’ I always say, ‘The higher the risk, the higher the reward.’ It went well enough that I said, ‘Let’s keep doing this and get better at it.’”

It wasn’t the only transition happening in Williams’ career. He was signed to Concord Records, which had released his acclaimed first pair of albums—State Of Art (2011) and Coming Of Age (2015)—but now, when it came to record labels, Williams “felt the arrows pointing in a different direction.” Meanwhile, James, singer Taali (aka Talia Billig) and recording engineer Brian Bender were forming a new record company, Rainbow Blonde, and they invited Williams to join the roster. Williams was a fan of Bender, for his ability to give jazz albums by Nate Smith and Kris Bowers the raw, old-school presence of Al Green or Earth, Wind & Fire. Bender wound up the engineer and programmer on I Am A Man.

“I wanted to change everything about my career—how I made records, what they sounded like,” Williams said. “I knew I couldn’t do this album the way most jazz records are recorded, two or three days in the studio, where you’re just capturing a performance. There was a lot of production on even the demos, and I knew I couldn’t replicate that in two or three days with my band. The timing of the new direction, and the new label, all came together.”

To assemble the pieces, the bandleader brought four-fifths of his road band into Bender’s L.A. studio (himself, saxophonist Marcus Strickland, guitarist David Rosenthal and drummer Justin Brown), along with guest vocalists Kendra Foster, Muhsinah, Wes Felton and Niles. Handling the keyboards was Williams’ old Juilliard classmate Kris Bowers, now based in southern California, where he works on film scores.

“I thought [Bowers] would be a perfect fit,” Williams said, “because he’s coming out the jazz harmonic tradition, and a lot of these songs are about capturing a sound and a feeling. As a film scorer, that’s what your job is.”

The core of the new album is a group of three consecutive songs about young black men being killed. This almost-cinematic trilogy begins with “Take It From Me,” written and sung by Williams over a herky-jerky drum part from Brown and inside a dense, murky sound design by Bender.

“I think Justin is one of the best drummers of our generation,” Williams said. “He listens to a lot of music. When you go on the road, you learn how diverse each guy’s musical taste is. With Justin, you can hear the influence of the great drummers, but you also hear the influence of hip-hop, r&b, gospel. When he plays a groove, it has that J Dilla feel, like it’s just off the grid a little bit, which gives it its character. It feels like our generation.”

“The vocal material felt strong, fresh and honest,” Brown said. “I kept my ear open to what he was saying musically and emotionally as a vocalist, so I could allow myself to be open to where the music needed to go. I always pay attention to the song titles. Like the song “March On,” that statement felt like an encouragement to keep pushing yourself and not to give up in a time of struggle. So, that’s the energy I tried to put into the groove.”

For “Take It From Me,” Brown’s push-and-pull beat reflects the anger and sadness that accompanies murder. As Williams’ bass and Bowers’ piano reinforce the dangers and alienation of America’s urban streets after midnight, Williams’ bleary voice laments, “Take it from me: The world is out to get us.”

That gives way to Niles’ rap segment—a father schooling his son on the realities of racism and violence. A piano solo brings in the sound of a police siren, a car pulling over, a door opening and a woman’s voice on a phone, saying, “I thought you would be home by now, but I haven’t heard from you.”

“Take It From Me” is followed by the track “Come Home,” which opens with Rosenthal’s distorted rock ’n’ roll guitar riff, supported by Williams’ fat electric bass line. A woman’s voice, perhaps the daughter of the earlier woman on the phone, sings, “Will Daddy come home? Is he safe?”

“‘Take It From Me’ and ‘Come Home’ are linked, absolutely,” Williams said. “I wanted to address police brutality, but I wanted to find creative ways of telling these common stories. So, I tried to focus on the family surrounding the victim. Every few weeks or so, you see another black man being shot by the police. You develop this anxiety in the back of your head: Will I be next? But it also creates anxiety in the people around them, the wives and children, who absorb those images on TV.”

The trilogy climaxes with “The Death Of Emmett Till,” Bob Dylan’s composition that laments the brutal 1955 murder of a 14-year-old African American boy in Mississippi. The heinous crime—and the fact that the murderers were found not guilty in a trial—fueled the civil rights movement. Williams’ version frames the story with strings, flute, blues guitar, funeral-procession drums and gospel harmonies, as if it were a bonus track on Marvin Gaye’s landmark What’s Going On.

Williams originally wrote the arrangement for the Congressional Black Caucus’ annual jazz concert on Sept. 21, 2017. He was part of a program titled “The Protest Anthology,” featuring everything from Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite to “The Death Of Emmett Till” and Common’s “Letter To The Free.” Other participants included Strickland, trumpeter Nicholas Payton, singer Jazzmeia Horn, pianist Christian Sands and tap dancer Jason Samuels Smith.

“The show was fantastic, an amazing group of musicians,” Williams recalled. “I love doing arrangements; I love to reimagine standards and give them new life. ‘Emmett Till’ has such a familiar melody that you can do so much to that song without obscuring it. I wanted to give it a millennial air and yet keep that church element to it. Those hip-hop and r&b influences often find their way into my arrangements, because I like to connect the dots, if the DNA of the music suggests it.”

Just as jazz musicians of the ’30s and ’40s used swing rhythms and Broadway tunes as raw material for their elastic arrangements and improvised solos, it makes sense that today’s jazz musicians use funk rhythms and hip-hop storytelling. And just as it was crucial for that older generation to respect their source material while finding ways to reimagine their rhythms and harmonies in contemporary ways, it’s just as important for today’s players.

“The adjustments that a musician or dancer makes moving from one style of music to another are always informed by the rhythms between the bass and the drums,” Strickland said. “Charlie Parker’s language on the alto saxophone is fluid and engaging of the harmony, while Maceo Parker’s language on the same instrument is more abrupt and punchy. Bass and drums are what makes us dance and sing differently, and the thing that ties it all together is the sound of the blues.”

“It’s important for jazz musicians to approach any style of music with the same respect and intrigue as they would jazz,” Bowers asserted. “There are times on an album like this where one can impose complex jazz harmonies or improvisation over the r&b/funk/hip-hop sound, but simplicity and part-specificity are also very important in those genres. There’s an art to playing the same exact part repeatedly and focusing on making it feel as good as possible. So, it’s important for jazz musicians to not mistake that simplicity with something being ‘easy,’ or ‘boring.’ If you don’t bring the same energy to a simple r&b/hip-hop part as you would playing on a more complex jazz composition, the music will suffer.”

Prior to this project, Williams had written many songs that featured vocals, but previously he had focused on the music and let his collaborators handle the words. This time around, because this was his project and because he felt so strongly about the message, he wanted to write the lyrics himself. He found it as challenging as learning a new instrument, and he drew inspiration from his favorite songwriters: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder, Joni Mitchell, Bill Withers and, above all, Marvin Gaye.

“Especially with this subject matter,” Williams said, “Marvin was very helpful in finding new ways of talking about serious issues. He showed us how you can talk about spirituality while wrapping it into a love song. You can fall in and out of spirituality just as you can fall in and out of love. As I looked into the soul of the black American male, the words started to write themselves.”

Perhaps the most ambitious lyric on Williams’ new album is “If You Hear Me,” the confessions of a troubled soul who has some hard questions for God. Over horns and a string quartet swooning in a minor key, and accompanied by jittery drums and guitar, Williams sings with a ghostly echo straight out of What’s Going On. “If you are who they say you are, the truth, the life, the way,” his narrator asks the deity, “why is there so much suffering? Do you hear me when I pray?”

“One of the topics I wanted to address on this album,” Williams explained, “is spirituality, which has been so essential to the black American experience. We’ve needed it in our tumultuous experience in this country. Usually you only hear about it from those who are certain. But I wanted to talk about it from the uncertain side. I wanted to go into the mind of the person who looks out the window, who believes in God, but who doesn’t always feel that love and protection. Maybe people don’t want to talk about it, but that’s an idea I wanted to express: Why are our lives like this?” DB

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/21/arts/review-ben-williams-sturdily-steps-up-on-coming-of-age.html

Review: Ben Williams Steps Up on ‘Coming of Age’

BEN WILLIAMS

“Coming of Age”

(Concord Jazz)

Ben Williams has a dark, righteous sound on an upright bass, and an almost liquid mobility through the fullness of his range. That much was established when he won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition in 2009, at 24. His development since then has had more to do with composition, leadership and artistic vision. And while an album shouldn’t necessarily function as a progress report, Mr. Williams knew what he was doing when he named his new one “Coming of Age.”

It’s his second release as a solo artist. His first, “State of Art,” arrived in 2011, an admirable but slightly overdetermined declaration of intent. Over the last few years he has recorded and toured with the guitarist Pat Metheny, a role model of consuming focus. And Mr. Williams has pushed toward a more natural, less insistent strain of jazz modernity, in his writing and in the metabolism of his own group, Sound Effect.

“Coming of Age” is a sturdy showcase for that band, with Marcus Strickland on tenor and soprano saxophones, Matthew Stevens on electric guitar, Christian Sands on piano and John Davis on drums. (The same crew, with a few additions, will appear with him on Thursday at the Cutting Room.)

Mr. Williams, who produced the album with Chris Dunn, frames its stylistic breadth within a larger unity of sound. Still, his compositions range from postbop wind sprints (“Forecast”) to the go-go of his native Washington. (“Half Steppin’ ”). A cinematic ballad titled “The Color of My Dreams” becomes a concerto of sorts for the vibraphonist Stefon Harris.

Among the album’s other special guests are Goapele, singing her own lyrics in the chilled-out soul tune “Voice of Freedom (For Mandela),” and Christian Scott, whose muted trumpet threads a breathy melodic line through “Lost & Found,” the Lianne La Havas song. The poet and actor W. Ellington Felton turns up, more awkwardly, to rap some verses (and sing a chorus) on a track called “Toy Soldiers.”

That’s one of several small missteps, another being a solo bass interpretation of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” a song that jazz musicians should no longer be mining for new truths. But Mr. Williams has his compass set, and it’s encouraging to think of this album as a marker, another checkpoint on the forward path.

https://www.wrti.org/cd-selections/2015-05-22/ben-williams-more-than-just-jazz-appeal

Ben Williams: More Than Just Jazz Appeal

It was easy to see why bassist Ben Williams’s debut CD State of Art made such a splash. It had a deserved buzz around a rising talent, and remains a primer for how to make a modern jazz record.

Since then, besides heavy side-gigging and touring with his band as Ben Williams and Sound Effect (Christian Sands, Marcus Strickland, Matthew Stevens, and John Davis), the 30-year-old had a key role in the Pat Metheny Unity Group. The band played over 150 shows internationally in 2013, which is a lot of experience in a compressed time frame.

So it’s not surprising that his follow-up CD, Coming of Age, is a rush of pleasure from beginning to end.

A taste of the new Ben Williams CD, Coming of Age:

The highly-disciplined Williams, a Juilliard graduate and winner of the 2009 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Bass Competition, weds fresh jazz to pop and R&B on seriously engaging tunes that hum and heave from his nimble bass whether he’s on acoustic or electric. The record is backboned by tracks that electrify (“Strength and Beauty”) and groove (“Half Steppin’”), yet his vocal collaborations with soul singer Goapele (“Voice of Freedom”) and a reprise of a track called “Toy Soldiers” with rap/spoken-word artist W. Ellington Felton satisfy the de rigueur groove revivalism and album’s crossover appeal.

Instrumentals like “Black Villain Music” and the sweet gloss of strings and muted trumpet by guest Christian Scott on “Lost And Found” will satisfy on multiple spins, but it’s the keyed-up guitar solos, funky electric piano, sonorous sax, and wicked beats that give Coming of Age its more-than-just-jazz appeal.

It’s a contagious hang, fueled by virtuosity and vision along with Williams’s canny sense of music-making.

This article is from the May 2015 edition of ICON Magazine, the only publication in the Greater Delaware Valley and beyond solely devoted to coverage of music, fine and performing arts, pop culture, and entertainment.Ben Williams, jazz bassist and bandleader, says his blend of genres reflects the times

The future of jazz may be in the hands of young artists like bassist and bandleader Ben Williams, who in his debut album, "State of Art" (Concord, 2011), fuses jazz, classical, hip hop and R&B.

Williams says that it "reflects the times. It's more or less a mirror of what's going on now, and what's been happening recently with music. Of course my originals are all recent stuff. Even the covers I did, I chose to cover songs by more modern artists."

His group Sound Effect "did a Stevie Wonder tune, a Michael Jackson tune, a tune by Goapele, a young R&B singer. Even on the oldest tune, 'Moonlight in Vermont,' I did a very modern take. It's just about keeping it fresh."

Williams and his band will continue the musical dialogue Wednesday at Smalls, an intimate jazz venue in the Village that seats 60.

"I hear the older cats talk about how jazz clubs back in the day were like a meeting ground, not just a place they played but where they hung out and checked out everybody else," he says. "Smalls is still one of those places. It's like a jazz community center."

The manager of Smalls, Spike Wilner, says that Williams is "at the forefront of the new generation of jazz players. He has a reverence for the tradition of this music but with an ear for the contemporary.

"He is also a humble person, a soft-spoken guy who doesn't really toot his own horn."

As you'll soon see, it's not necessary for Williams to toot his own horn when artists such as Pat Metheny will do it for him.

The winner of the 2009 Thelonious Monk International Bass Competition, Williams is a laid-back guy from Washington, D.C., who now lives in Harlem. He began on piano, and moved on to bass during high school.

"I moved to New York in 2007. I had just finished doing my undergrad work at Michigan State, to start a master's at Juilliard. This is the ultimate proving ground for musicians.

"Harlem is like the closest thing to being back in D.C., very soulful."

Williams, 27, spends much of his time as a sideman in jazz rhythm sections. Vocalist Jose James, vibraphonist Stefon Harris, pianist Jacky Terrasson, harmonica player Gregoire Maret and trumpeter Etienne Charles are some of the artists he has performed with of late.

Yet the most famous artist he has been gigging with may be guitar legend Pat Metheny, one of Williams' heroes. On Tuesday, Metheny's new group and recording project, "Unity Band," will be released with Williams holding down the bass chair. (Saxophonist Chris Potter and drummer Antonio Sanchez round out the ensemble.)

"It was a joy!" Williams exclaims when asked about recording with Metheny's new band. "He's such a musical mastermind. He doesn't just put things together without a concept behind it. Everything just fits within that. And he's just a great human being, and very supportive of the young cats."

One of Williams' mentors, bassist Christian McBride, invited Metheny to check out some of the students at Juilliard several years ago. When he heard Williams, Metheny says he "had that rare feeling of hearing someone that has something special to say. I used Ben a few times to sub for Christian with the trio and found him to be a great playing partner and a great person, too."

On his website, Metheny writes about the new recording, saying that "Ben has a fearless and open-minded approach to what music can be, which made him perfect for this band. I really enjoy playing with him and he was fun to write for, too ..."

Metheny, who went to school and later recorded with electric bass giant Jaco Pastorius, says that Williams' melodic approach is similar to Jaco's.

"Finding guys who can play great melodies has always been hard, and Ben has natural way of using space as well as being able really get around the instrument; a wonderful combination of skills."

YOU SHOULD KNOW

Ben Williams & Sound Effect, featuring Marcus Strickland, tenor sax; Matt Stevens, guitar; John Davis, drums; and Gerald Clayton, piano. Wed., 8:30-11 p.m., $20 (students $10, second set), Smalls Jazz Club, 183 W. 10th St.

JAZZ OF NOTE THIS WEEK

The Musical World of Ralph Ellison

Tues., 7-8:30 p.m., Free, NJMH Visitors Center, 104 E. 126th St., Suite 4D, (212) 348-8300.

The cultural and regional link of Ralph Ellison, a superb 20th century writer on the blues and jazz, to his native Oklahoma and to Lester (Prez) Young will be pursued by Columbia professor Robert G. O'Meally and Loren Schoenberg, artistic director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem.

Jazz Gallery Home Run Benefit Concert

Wed., 6:30, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, 515 Malcolm X Blvd., $45-250, (212) 242-1063.

The Jazz Gallery has been an institutional bridge for young jazz artists to gain needed experience and exposure on the bandstand. Currently at 290 Hudson St., they must get a new location by year's end. That's why they deserve support. The benefit features Kenny Barron, Roy Hargrove, Henry Threadgill, Linda Oh, Ravi Coltrane, Claudia Acuña, Vijay Iyer, Lionel Loueke, Dafnis Prieto and more.

https://www.music.msu.edu/news/jazz-bassist-ben-williams-receives-msu-young-alumni-award

Jazz bassist Ben Williams receives MSU Young Alumni Award

GRAMMY

Award winner Ben Williams added another high honor to his growing list

of accolades after receiving the 2013 Young Alumni Award from Michigan

State University in October. Williams earned a bachelor's degree in

music education in 2007 and studied under Rodney Whitaker, professor of

double bass and director of jazz studies, and Jack Budrow, professor of

double bass and co-chair of the string area.

"When he first auditioned at MSU, after I heard a few notes, I knew he was going to be a star," says Whitaker.

As a student and young professional, Williams won two of the most prestigious awards available to a jazz bassist. He won first place in the International Society of Bassists Collegiate Competition in 2005. Four years later, he won the annual Thelonious Monk Jazz Competition in Washington, D.C.

Since graduating MSU, Williams has soared to the top of the charts. His highly regarded 2011 album "State of Art" received a 4.5 star review in Downbeat Magazine and reached number 1 in Jazz Radio. He was named Breakthrough Artist of the Year by iTunes after his album held the number one spot on iTunes for three consecutive weeks.

In 2012, Williams was named Up and Coming Artist of the year at the 16th Annual Jazz Journalists Association Jazz Awards at the Blue Note Jazz Club in New York City. In 2013, his work with the Pat Metheny United Band received a GRAMMY for Best Instrumental Jazz Album.

Williams received his master of music in jazz studies from Juilliard School in New York City, where he now resides. He regularly collaborates with leading jazz musicians, including Stephon Harris, Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard and Dee Dee Bridgewater, and has mentored MSU jazz students who have moved to the city.

"Ben is a committed and effective educator who passes on the tradition of jazz and blues that was handed down to him," says James Forger, dean of the MSU College of Music. "He is truly an exceptional young Spartan."

https://daily.bandcamp.com/features/ben-williams-i-am-a-man-interview

FEATURES On “I Am A Man,” Jazz Bassist Ben Williams Redefines Protest Music On His Own Terms

by Shannon Effinger

February 25, 2020

Bandcamp.com

D.C.-born, New York-based musician Ben Williams is out to change the way people think about protest music. “I felt like a lot of artists really want to address the current sociopolitical climate,” he says. “And there’s definitely a lot going on right now. I wanted to not do a traditional protest record, but [instead], show all the facets of our existence. A lot of times, we’re kind of defined by our struggle. It’s definitely part of who we are. But we are also complete human beings. After—and in between—those moments of protest, we’re just regular people that go home to their families and go through life, dealing with the same thing that everybody else does. So, in addition to addressing issues like police brutality, I wanted to talk about us.”

Williams’ rise to prominence began after he won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition in the double bass category back in 2009. Three years later, he nabbed a Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Album as a member of guitarist Pat Metheny’s Unity Band. Since then, he’s released two solo albums for Concord Records—State of Art in 2011, and Coming of Age four years later. But it’s on I Am A Man that Williams discovers his true voice—both metaphorically and literally: The record marks the first time Williams contributes lead vocals to an album.

That idea came at the suggestion of frequent collaborator José James, while the two were on tour together. Wiliams played James some early demos for I Am a Man that featured his voice. “I had these songs written, but it was mostly for other people to sing,” Williams recalls. “[José] heard the demos and asked, ‘Yo, that’s you singing? You should sing!’”

I Am A Man draws its primary inspiration from the spiritual tenor and political urgency of the ‘60s—specifically, the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, which inadvertently set the stage for Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination just a few months later. The title for the album came to him while watching Ava DuVernay’s critically-acclaimed documentary 13th, which explores the connection between the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery, and the mass incarceration of people of color in the United States. Williams was particularly struck by the end of the film, which featured a collage of both present-day photos and period images, including those of the sanitation strikers holding up the now iconic signs that read “I AM A MAN” in simple boldface type.

“Visually, there was just something about it that stuck—just seeing the phrase repeated over and over; it was just so uniform and military,” he says. “I really thought [a lot] about that phrase and what it really means, and how it relates to me now. There was something about those still photos that reminded me of a hashtag—like a hashtag before [there were] hashtags. This adopted phrase, that you see over and over and over again, is sort of the same way we use hashtags today, like #BlackLivesMatter.”

On I Am A Man, the song “Promised Land” was directly inspired by King’s famous “Mountaintop” speech, which he delivered to the Memphis strikers. In the song, Williams, with Marcus Strickland on bass clarinet, lead us through a three-movement odyssey: First, Williams assumes the role of a young black man in America, faced with rampant adversity, searching for peace that is “so close, but yet so far;” then, Williams daringly “becomes” King, reciting the prophetic words of the speech he delivered less than a day before he was killed. Finally, the song reaches a crescendo that features a bravura performance from former P-Funk member and D’Angelo collaborator Kendra Foster. Together, they assure us, “We gon’ make it y’all / All you have to d o/ Is stay cool.”

Lead single “If You Hear Me” conjures the spirit of yet another D.C. native—the great Marvin Gaye. The song evokes the sound of Gaye’s classic Motown sessions, where no expense was spared in enlisting an arsenal of live musicians to fully capture the full breadth of Gaye’s vision. Williams’ own arsenal features several longtime collaborators: Strickland on tenor sax, trumpeter Keyon Harrold, Kris Bowers on keys, and drummer Jamire Williams. The song is fleshed out with a backdrop of percussion and flute (Bendji Allonce and Anne Drummond, respectively) and a lush string arrangement courtesy of violinists Chiara Fasi and Maria Im, Celia Hatton on viola, and cellist Justina Sullivan.

Though it is both politically charged and incisive, I Am A Man never feels freighted with the emotional heft of the past. Songs like “March On,” which features D.C. actor/poet Wes Felton, and “The Death of Emmett Till,” highlight pivotal moments that launched the Civil Rights Movement, but they’re balanced by Williams’ deft arrangements, which draw equally on P-Funk, Prince, and D’Angelo’s Voodoo. In a voice that’s both honest and unassuming, Williams paints a portrait of an artist—and a black man in America—in search of answers to help guide him through life. And while he never set out to make a “D.C.” record, Williams couldn’t help but feel that growing up in the DMV played a clear role in the way I Am A Man ultimately turned out. “I feel like I got to see our complete humanity on display as a culture when I was growing up in D.C.,” he says. “It’s such an Afrocentric city. Or, at least, it was when I was coming up. It was ‘Chocolate City.’ Black consciousness was always part of our thing.”

Jazzhttps://www.capitalbop.com/ben-williams-i-am-a-man-interview/

Ben Williams speaks up, and sings out, on ‘I Am a Man’

After the 2016 presidential election, bassist Ben Williams began a new project to address the changing social climate in the United States. The music he wrote was framed around two major pillars: a program of protest songs he performed at the 2017 Congressional Black Caucus Foundation jazz concert, and the “I AM A MAN” signs of the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike of 1968. And as he sought to write music of his own, confronting the present-day situation, he went off in search of a new sound.

Williams is the most prominent millennial musician to come out of the D.C. jazz scene. The 35-year-old bassist grew up in the District, studied with local legends like the late saxophonist Fred Foss, attended the Duke Ellington School of the Arts and won the 2009 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition (now the Herbie Hancock competition) in an emotional ceremony at the Kennedy Center. As his visibility in the jazz community skyrocketed, he started recording and touring as a bandleader, releasing his debut album, State of Art, in 2011 to critical acclaim, and his sophomore effort, Coming of Age, in 2015.

On Williams’ first two recordings, he worked in something akin to a modern post-bop setting, straddling the fine line between traditional deference and departure. But his new conception was based in a different aesthetic. Twisting melodies and explosive solos give way to brooding keyboard grooves and industrial, synthesized beats. And Williams, who recently started writing songs with lyrics, stands at the microphone for the first time in his two decades as a musician, singing and rapping as his fingers blend sturdy bass notes into the foundation. His newfound voice, literal and figurative, plays a prominent role on his third album I Am a Man, which was released in February of this year.

Williams was supposed to show off this new sound at D.C.’s City Winery back in March, but the COVID-19 pandemic put the kibosh on that. Regardless, we didn’t want to pass up the opportunity for a check-in with one of D.C.’s most important musical exponents. When we spoke in March, Williams was on a tour bus, finishing up a string of dates with Kamasi Washington, including a hero’s welcome at the Howard Theatre in February. Hopefully he’ll get that hometown embrace again soon.

<a href="http://benwmsonbass.bandcamp.com/album/i-am-a-man">I Am A Man by Ben Williams</a>CapitalBop: A couple things stood out to me while listening to I Am A Man. First, is there any relation to the Ron Miles project of the same name from 2017? And then, I noted some sonic and lyrical nods to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On — did any of that play a role in shaping the record?

BW: Yeah, I did check out the Ron Miles I Am a Man and it ended up being a coincidence. I kind of started conceptualizing this project before it came out.

The second [thing] you mentioned — Kendrick Lamar, To Pimp A Butterfly — I think was a pretty influential album to a lot of folks of my generation. I think it really set a bar for collaboration and creativity and it put a lot of pieces together conceptually. It brought these worlds together that I knew co-existed, but just the way they put it together and how open and free they wrote the ideas and a lot of Kendrick’s experimentation and just not really being afraid … I definitely aim to make some kind of album with that same kind of feeling of “OK, you can’t really classify this as one thing.” I love the topics that he covers too. All of his albums really are based on a lot of subjects that are maybe taboo in the community, or some things that we don’t seem to express in music.

And the third one, What’s Going On: Absolutely on how I write songs and a big influence on me, musically and conceptually. I wanted to deal with off-the-beaten-path topics with this record and I think that’s something that he does very well.

He can talk about the environment or war or divorce, just things that are part of our lives. A lot of music … centers around a lot the same subjects: romantic love, you know? He could give you the same feeling singing a song about the earth, and make you feel as if it’s a love song. So that’s what I really love about Marvin. Of course, I grew up listening to a lot of his music, because of my mother and my parents; his music was always in our ears. You start to understand more about him — where he’s from and where’s he coming from and the risk that he took in his own career and his life.

I don’t really consider this album so much a ‘protest’ record…. Really it’s more about humanity.

—Ben Williams

CB: So how did this album start? When did you start conceptualizing it and what were the catalysts that really led to its creation?

BW: It was 2017. I did a show for the Congressional Black Caucus [annual] jazz concert that the late John Conyers was responsible for putting on for many years in D.C. They asked me to be the musical guest that year, the featured guest, and I wanted to do something to speak to the social climate. I put together this concert that was called “The Protest Anthology,” basically a collection of protest songs from different eras going all the way back to like Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Bob Dylan all the way up to Common. That kind of got the wheels spinning as far as doing a record speaking to the social climate.

More specifically, the idea for calling it I Am a Man — I was watching the Ava DuVernay documentary 13th, which came around the same time, and there’s a montage at the end of the video where she shows all these still shots that tie into the film. And of them was one of those iconic shots from the [Memphis sanitation workers] protest and it went by really quick, it was just this quick flash of the man in the picket lines holding up the “I AM A MAN” sign. I think there was something about that that just stuck with me. There was something about that phrase that I couldn’t really get out of my head. So, I sort of used it as the thematic framework: how to dig into the phrase and what I felt that phrase meant to me, what it meant to those men back then and how to bring it to a modern context.

This is the first time I’m singing on an album. There’s no previous notion of what I think I’m supposed to sound like or anyone else would think. It’s all fresh; I can interpret it and do everything I want to.

—Ben Williams

CB: What does the phrase mean to you? How did you think about it and chew it over and you were writing and recording the album?

BW: Well for me, I think it’s such a declarative phrase. It’s a response to a situation, but it’s more like — to me it feels like it’s standing strong in your truth of who you are as a person. So, it’s about telling the world, telling your society that you exist, and it’s a way of telling them who you are. Back then, these were grown men, but they were often referred to as “boy” as a demeaning term. I wanted to dig into the complexity of what it is to be a black man in the United States — really in the world, but most specifically here.

CB: A lot of the discussion has described this as an album of “protest songs.” What did that idea of protest mean to you? How did you think of this idea of the protest song?

BW: I don’t really consider this album so much a “protest” record. It’s part of it, but I feel that at least half of the songs are … talking about different topics. Really it’s more about humanity. The protest part is very much tied into our experience; a lot of our history is defined by the struggle, but we’re so much more than that too. That’s not what defines us as human beings. We deal with a lot of the same issues that everybody else does and that’s why we touched on these topics like spirituality, addiction, more universal topics as well. Again, going back to the big picture, to all the layers of our existence.

<a href="http://benwmsonbass.bandcamp.com/album/i-am-a-man">I Am A Man by Ben Williams</a>CB: That declarative statement “I am a man” becomes a path to explore what it means to be human.

BW: Exactly.

CB: When you started writing, did you picture it in its end form being less of an instrumental record and more this modern vocal and hip-hop fusionist sort of thing?

BW: It actually did start as mostly instrumental tunes. At the beginning I hadn’t planned to sing at all but as I started to write, I started to write a few vocal songs that I had originally intended [for others], and the first number of shows I had other singers singing these songs that I was writing for them. I would make these demos, which I would usually do if I’m writing for a singer, and I was sitting with Jose James while we were on tour a couple of years ago and we were doing the Bill Withers tribute project and I let him hear a couple of the demos. He went, “Wait a minute, that’s you singing.” I was like, “Yeah, that’s me” and he really encouraged me to do more singing on my own. He was like, “Yeah man, you got a great voice, you should sing, man.” He can be very persuasive. He helped me build up the courage to do that. I went in the studio and just kind of went for it; I mean the songs are so personal.

Actually, the cool thing about going into it — this is the first time I’m singing on an album. There’s no previous notion of what I think I’m supposed to sound like or anyone else would think. It’s all fresh; I can interpret it and do everything I want to. The journey of the songwriting, of the material, started with a typical jazz instrumental with different influences, something closer to what I’ve done in the past — but a couple of songs here and there … were going to be vocal. Then I think at a certain point it just started to feel like it was going to be two different albums, so I focused on the vocal songs and more and more songs started to develop.

CB: Your fellow D.C. jazz ex-pat Braxton Cook started singing on his albums recently as well.

BW: Yeah, he’s a great singer too.

CB: Yeah! I’m wondering, because he and I talked about this: Was it at all difficult,m or did it feel like a huge leap to actually sing on one of your records after being an instrumentalist for so long?

BW: For me, it was a pretty bold step. Personally, I’m never afraid to try something different creatively. Truthfully speaking, when you start singing and you’re jumping in front of the mic, especially in public and on record, you start to get looked at … and you look at it in a different way. It’s hard to describe how that feels. …There’s a whole other layer of music that you have to deal with in singing. You’re expressing yourself in the purest way. …I’m still getting used to it, but I’m enjoying it. A lot of it is just kind of believing that you can do it.

CB: Can you see yourself bridging those two worlds continuously, dipping in and out of vocal and instrumental jazz?

BW: I plan on doing more of it and seeing where this path takes me. For me it’s like — I’m picking up all the pieces as I go along so it all becomes one, big home. What I’m really enjoying about this is: It’s kind of expanding my scope so I can think like a pure singer-songwriter, approach music like that. On the other end, I can keep it as jazz bass player guy. So in the end, what becomes who I am is everything in between that. It gives me a lot of room to work with. It’s very liberating, actually.

One of my heroes actually is Meshell Ndegeocello. She’s a really great example of … existing in this wide scope, having a wide range, but it’s all her. It never feels like she does anything that’s not integral to who she is.