SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2021

VOLUME NINE NUMBER THREE

FARUQ Z. BEY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

William Parker

(January 23-29)

Jason Palmer

(January 30-February 5)

Living Colour

(February 6-12)

Charles Tolliver

(February 13-19)

Henry Grimes

(February 20-26)

Marcus Strickland

(February 27-March 5)

Kendrick Scott

(March 6-March 12)

Seth Parker Woods

(March 13-19)

Kris Bowers

(March 20-26)

Ulysses Owens

(March 27-April 2)

Steve Nelson

(April 3-9)

Steve Wilson

(April 10-16)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/steve-nelson-mn0000044991/biography

Steve Nelson

(b. August 11, 1954)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

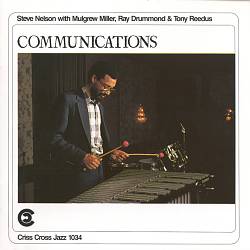

One of the most highly regarded vibraphonists of his generation, Steve Nelson is recognized for his inventive, fluidly harmonic approach to post-bop jazz. Nelson initially emerged in the '70s building upon the tradition of players like Milt Jackson and Bobby Hutcherson and playing with luminaries like Kenny Barron, Donald Brown, and James Spaulding. He is also a longtime member of bassist Dave Holland's quartet. As a leader, he has issued a handful of trio and small group dates like 1987's Communications, 2004's Fuller Nelson, and 2017's Brother's Under the Sun.

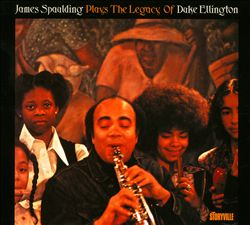

Born in 1954 in Pittsburgh, Nelson started playing the vibraphone at age 15 after being introduced to the instrument by a school friend's father, George A. Monroe. A steel worker by day, Monroe was also a talented vibraphonist in the Milt Jackson tradition. He gave Nelson crucial early instruction in jazz and even started him playing piano. Looking to focus on his jazz interests, Nelson dropped out of high school and by the early '70s was gigging regularly, honing his skills alongside such local Pittsburgh luminaries as drummers Roger Humphries and J.C. Moses, trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, saxophonists Eric Kloss and Nathan Davis, and guitarist Jerry Byrd. After several years in Pittsburgh, he moved to New Jersey where he lived with his brother while seeking out more opportunities around New York city. It was during this period that he sat-in on an outdoor concert at Rutgers University featuring professors pianist Kenny Barron, bassist Larry Ridley, and drummer Ted Dunbar. Impressed, the professors helped Nelson gain entrance to the school's then-fledgling jazz degree program, where he eventually graduated and earned a Master's degree. Along with the school, Nelson continued to find work. He made his recorded debut in 1976 on James Spaulding's Plays the Legacy of Duke Ellington, and found himself busy throughout the early '80s working with Barron, David "Fathead" Newman, Bobby Watson, and others.

As a leader, Nelson made his debut with 1987's Communications on Criss Cross, playing with Mulgrew Miller, Ray Drummond, and Tony Reedus. However, he primarily worked as a sideman, appearing on dates with Miller, Donald Brown, Geoff Keezer, and others. His second solo outing, Full Nelson, arrived in 1989 and featured Drummond and pianist Kirk Lightsey. During the '90s, Nelson distinguished himself as a regular member of bassist Dave Holland's groups, appearing on such albums as 1995's Dream of the Elders and 1998's Points of View. He returned to leading his own group on 1999's New Beginnings, which again featured Miller, as well as bassist Peter Washington and drummer Kenny Washington.

Throughout the early 2000s, Nelson continued his work with Holland. There were also notable sessions with David Hazeltine, Barbara Dennerlein, Mike LeDonne, and Eric Reed, among others. His own Fuller Nelson arrived in 2004 and found the vibraphonist again working in a trio with pianist Lightsey and bassist Drummond. He then paired again with pianist Mulgrew Miller, bassist Peter Washington, and drummer Lewis Nash for 2007's Sound-Effect. Around the same time, he contributed to albums by David "Fathead" Newman, Karrin Allyson, Louis Hayes, and more. In 2017, he issued Brothers Under the Sun with pianist Danny Grisset.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/stevenelson

Steve Nelson

Paul Motian & Steve Nelson

Not saying I’ll make it (the best laid plans and all that), but it’s my intention to go to the Village Vanguard this evening to hear the final night of Paul Motian’s week-long MJQ homage with Steve Nelson, Craig Taborn and Thomas Morgan. I’m very curious about this gig. This collection of personalities can play it straight or deconstruct – what will they do? With no disrespect to any other vibraphonist on the scene, Steve Nelson is my favorite on the instrument amongst a cohort of equals — everything is taste, after all. Comparing him to Joe Locke or Bobby Hutcherson or Gary Burton, or Stefon Harris (wunderkind Warren Wolf is getting there, and Tyler Blanton…and let’s not get into an hierarchical name game anyway, or I might get a mallet upside my head) is an endeavor about as useful it was for Robert Friedlander and I when, during games of baseball card war in the mid ’60s, we’d fight over whether Willie Mays trumped Hank Aaron or Roberto Clemente or Frank Robinson. Steve plays with such freshness in so many contexts, and his snaky rhythmic feel is singular. So for my first post, I’ll paste below a piece I wrote about Steve for DownBeat in 2007 that never made it into print. Now, this is a penultimate final draft, not the FINAL-final draft, and I would have worked more on the ending. But anyway, here it is.

* * * *

“The next young cat is going to play inside, outside, jazz, classical, play the blues, be a good reader, play with everybody—a total command,” said vibraphonist Steve Nelson last October, reflecting on the future of his instrument. “It might be a she, I don’t know. But somebody is going to take the vibraphone to a different level.”

More than a few distinguished members of Nelson’s peer group opine that although Nelson, 53, is neither a serial poll-winner nor a frequent leader of sessions, he himself is the most completely realized and original performer on the vibraphone and marimba to emerge in the wake of ’50s and ’60s pioneers like Milt Jackson, Cal Tjader, Bobby Hutcherson, Gary Burton, Walt Dickerson, and Cal Tjader. One such is Dave Holland, Nelson’s employer since 1996, with whom Nelson was preparing to embark to Asia and Australia for two weeks of gigs.

“I’ve always looked for players who are very deeply rooted in the tradition, who can move the tradition into new, contemporary areas, and Steve is one of those people,” Holland said. “The reason I use a vibraphone in my quintet and big band is because he exists. He’s an original thinker who comes to conclusions one wouldn’t expect, and he’s used our compositions as a vehicle to break new ground for the instrument.”

Upon his return, Nelson would enter Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola for a week with Wingspan, pianist Mulgrew Miller’s sextet, adding another chapter to a two-decade tenure with the band. Asked to describe Nelson’s qualities, Miller was effusive. “Steve has no limitations,” he remarked. “I can write just about anything, and he’ll make it sound beautiful. He’s definitely a swinger, but even more important is his creative fire. Like Kenny Garrett, he was already an individualist early on; they played like they were old souls already.”

Joining A-team bass-drum tandem Peter Washington and Lewis Nash, Miller plays piano on Sound-Effects [High Note], an inexorably propulsive, blues-tinged eight-tune recital that is Nelson’s first leader date since 1999. The repertoire, recorded over the course of an evening and realized mostly as first takes, includes three Nelson originals and five jazz standards, including “Night Mist Blues,” by Ahmad Jamal,” “Up Jumped Spring,” by Freddie Hubbard, and “Arioso” by the late James Williams, another frequent Nelson partner and employer throughout the ’80s and ’90s. Others who recruited Nelson for record dates or retained him for consequential tours of duty during those years include Kirk Lightsey, George Shearing, Kenny Barron, Donald Brown, Geoff Keezer, David “Fathead” Newman, and Nash.

“It was happening from the first beat,” Nash recalled of the session, which could stand as a contemporary paradigm of 21st century hardcore jazz aesthetics. “It expresses how Steve felt right then. He could easily make a record of very adventurous, modern things which are pushing the envelope in various ways, but a musician like him doesn’t feel he HAS to do that. He can go into the studio and play how he wants to play.”

“It’s a matter of the highest difficulty to play those tempos and get that kind of flow and phrasing and interplay and sound, to make the vibraphone breathe and sustain that good, swinging groove,” Nelson said in response to a comment that perhaps, given the opportunity to conduct a few pre-studio rehearsals, he might have recorded the “adventurous, modern things” to which Nash referred. “It’s not as basic as some might think. Milt Jackson did it very well, but very few people have done it, including myself. I’m trying to get to it.”|

Nelson’s protests to the contrary, his colleagues are emphatic that the 53-year-old vibraphonist-marimbist has “it” in abundance. “Steve is one of the great improvisers I’ve played with in the sense of taking chances and breaking new ground,” Holland stated over the phone from Japan. “I’ve played with him night after night, year after year, and he never fails to surprise me. Last night, for example, he did something I’ve never heard him do before, which was to use a very fast tremolo and play the voicings percussively around the rhythms that [drummer] Nate Smith was playing, which created an amazing effect. He finds so many different ways to create tonal textures with mallet combinations—we all turn our heads sideways to see the voicings he’s playing, because we can feel them. He has roots in the blues which always seem to come through somewhere, no matter what we’re playing, and he grasps all the great traditions of accompaniment through having played with so many of the great piano players.”

“I almost put him in another category than other musicians I play with,” said Chris Potter, Nelson’s bandmate with Dave Holland since 1997. “I don’t know where he channels from, or how he conceptualizes all this stuff, but I’ve played countless gigs with Steve, and I never know what he’s going to play. He’ll go along normally, then turn completely left. Or not. You just don’t know. It’s true improvisation, reacting to some inner dictates that he has access to.”

“He’s a wonderfully economical player who can say a lot with very little,” said Smith. “He’s a very abstract thinker in his comping, his rhythmic responses to odd meters, but it all makes sense, and he paints beautiful pictures with the soft and beautiful tunes he brings to the band. They say still waters run deep, and he’s the perfect example of that saying.”

The still waters metaphor also applies to Nelson’s gestural vocabulary—he coils over the keyboard, jabbing and weaving with an economy of moves to create asynchronous punctuations that bring to mind Thelonious Monk’s pouncing comp, or Muhammad’s Ali’s motto, “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” “The only thing that touches the vibraphone when you’re playing is one little piece of your foot, so you use all the wide space around you,” Nelson explained.

Nelson brings to bear a full complement of rhythmic acumen on Stompin’ at the Savoy and It Don’t Mean A Thing [M&I], both inventive Nash-led trio dates for the Japanese market on which Peter Washington plays bass. “Steve understands that the vibes are melodic as well as percussive,” Nash remarks. “He builds ideas not only harmonically or linearly, but through dynamics—he knows when to strike the bar to make it speak in a certain way. He double-times and plays across the barline; the shapes of his lines give the illusion that you’re hearing polyrhythms, because his rhythm fits on top of the primary pulse, which creates a tension. He’s extremely knowledgeable about chord structure and harmonic theory, which allows him to be free even on the most basic harmonic structures. He makes even the most tried-and-true songs sound fresh. But when he plays in situations with different meters and uncharacteristic harmonies, or vamps and ostinatos over one harmonic framework, he makes that work, too.”

The sum result, stated Keezer, who deployed Nelson on four of his ‘90s dates, is “a completely original voice—home-made might be the word. I don’t hear him coming heavily out of Milt Jackson or Bobby Hutcherson, or any other vibraphonist, but more taking that postmodern language that Woody Shaw, Mulgrew, and Kenny Garrett use, and translating it onto the vibes. His free time sense is the quality I hear now in Herbie Hancock or Wayne Shorter, which suggests that they could play anything at any time and it would sound right. It’s hard to quantify, but it’s a mark of mastery in playing.”

[BREAK]

There are reasons why Nelson, a virtuoso musician who has made consequential contributions both to the development of speculative improvising and the tradition, is less visible to the broader jazz audience than his talent warrants. For one thing, as Nash comments, “People see with their eyes, but they don’t hear with them, and you don’t necessarily match Steve’s reticence and understated personality with this kind of musicianship. He’s not jumping up and turning somersaults and flips.”

Another reason is timing. Like Bobby Watson, Brian Lynch, Fred Hersch, Steve Coleman, Joe Locke, and David Hazeltine, all tradition-to-the-future virtuosos born in the middle to late ‘50s, Nelson cut his hardcore jazz teeth with local mentors on his home-town’s indigenous jazz scene. For Nelson, out of Pittsburgh, this occurred at the cusp of the plugged-in ‘70s, with such local heros as drummers Roger Humphries, Joe Harris, and J.C. Moses, trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, saxophonists Eric Kloss, Nathan Davis, and Kenny Fisher, guitarist Jerry Byrd, and Nelson’s direct influence, a steelworker named George A. Monroe who played vibraphone in the Milt Jackson style.

“The guys in Pittsburgh were great musicians, and I could use everything they taught me when I went to college,” Nelson recalled. “Mr. Monroe was the father of my high school buddy. I heard him play one day, and I fell in love with the sound of the vibes. He started teaching me, and thought I had some talent, so he kept on teaching me. Taught me things on piano that I could copy directly—lines and so on—and a lot of tunes. Coming up in Pittsburgh, you learned your standards, and I still enjoy playing them.”

“Steve was an amazing younger player, perhaps the brightest student I ever had,” recalled Kenny Barron, who taught Nelson at Rutgers, where he earned the nickname “absent-minded professor,” during the ‘70s. “He came to Rutgers being able to play—he knew all my tunes, and I started using him in my group.”

“We were trying to be dedicated, but it was a difficult time to maintain your focus,” Nelson recalled. “But as we moved along, we got caught in the whole Young Lions thing of the early ‘80s—we weren’t older, established guys either at the time, and we never really got a chance to expand as leaders and get our names pushed out there.”

In a certain sense, Nelson’s versatility and open attitude, his dedication to serving the dictates of the moment without concern for their “progressive” or “conservative” implication, may also work against his recognition quotient in a climate when complexity and genre coalescence are in high regard.

“It wouldn’t be that different,” Nelson said in response to an observation that, given several preparatory gigs and rehearsals, Sound-Effects might have explored some different areas. “I might write a 12-bar blues with different harmonies and extensions, but it would still be a nice, medium tempo blues. I think the most important thing you can do is to play what you love. If that happens to be ultra-modern or ragtime, or something in between, that’s great. But if it’s from your heart and it’s honest, then you’re contributing to the music. Herbie Hancock was always one of my favorite musicians, because if you put him in a blues band, or a funk band, or a straight-ahead band, he’ll play the heck out of all of them. A really good musician can contribute, no matter where they go.

“When I joined Dave, I was starting to think about the unique qualities of the vibraphone. Rather than transfer piano chords or guitar chords to the vibes, what intervals can I create? How can I space things to exploit the vibraphone as a percussive instrument? On piano, you have all 10 fingers. The shape of the vibraphone keyboard gives you different intervallic ideas; with the four mallets, you can get different ways to voice chords—I guess you could call them dissonant—that you might not otherwise think of. Those intervals allow you to use space more effectively than with other instruments. I can hit a chord, and let it ring out over the band, which leaves a lot of air for the drums, with their advanced rhythmic concept, to respond to, then the soloist puts something on top.”

Nelson added: “Although we’ve had a lot of impact on other bands playing in odd meters, to me, the real important aspect of Dave’s thing is the interplay and free flowing of ideas that his structures encourage.”

He recalled an early 2007 engagement with Kirk Lightsey at Manhattan’s Jazz Standard that provided an opportunities for conversation in notes and tones. “We played ‘Temptation,’ which contained wide-open areas between the melody for segues, and we had to listen hard,” he said. “Now, Kirk has a different tone and touch on the piano than Mulgrew Miller does, but I don’t make conscious adjustments for either of them. Now, with George Shearing, the concept was the sound of the band, rather than interplay. You’re playing at a such a soft dynamic level with the guitar and piano, that you’re inside each other’s sound—it’s like a spiritual happening. Truth is, I loved it. With any musician, if you play what you hear, it magically works. If you have the basic building blocks of musicianship together, you’ll be able to play with anybody.”

Which provoked a final question on this ideal sideman’s future plans.

“It’s becoming more important to me to be a

leader, because you develop your own ideas, and want to put them out

there,” he responded. “But the truth is that learning how to play that

instrument is my central focus. Not many of us play vibraphone. There

aren’t a lot of method books to go through. You wind up trying to play

like saxophone or trumpet, or do other things that people ask, but I

don’t know that we always think so much about how to create a language

and a sound for the vibraphone itself. If I ever figure it out, I’ll

write a book!”

Steve Nelson: Vibing

AllAboutJazz: There have been so few vibraphonists in jazz; what first attracted you to the instrument?

Steve Nelson: Well, actually, there are probably more vibists than you think there are, first of all. I mean everywhere I go, at least since I've been traveling so much with Dave Holland, I actually meet—in every town that I go to—a few vibists. I guess compared to the other instruments there's not so many vibists, but there seems to be more and more coming around these days.

But anyway, I actually got into the vibes because a young guy that I used to hang around with in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where I was born and grew up—his father actually played the vibes. He was one of those kind of guys that existed then [laughs], at that time, I guess it was the seventies or something, who lived in a town like Pittsburgh and played and was a great player, but was raising a family, worked in the steel mills, etc., etc., so he never came to New York, but was a tremendous vibraphonist. So, I actually heard him play and that's how I fell in love with the instrument. His name is George Monroe. I actually dedicated a song to him on one of my records called George A—"Blues For George A, and that's how I got started—through hearing him play.

SN: Oh, I was afraid you were going to ask me that, Russ. I played a little drums, with the emphasis on very little drums, at that time and I never continued much on drums, after that. But, he got me into vibes and he also got me into piano, so I started playing a little piano around that time, too.

AAJ: When was that? About how old were you at the time?

SN: My dates are usually off, man. I don't know what year it was; I was around fifteen years old I guess—fifteen, sixteen years old.

AAJ: What kind of music did you play, once you began playing the vibes? Did you start playing jazz right away?

SN: You know, at the time ... yeah! It's a funny thing, I didn't really go through an extensive thing, like I guess most cats my age do; an extensive R&B thing and go through that whole thing, etc., etc. I had listened to all that as a kid, but when I heard this guy play, it immediately turned me around and from then on—I would really say that from the time I was fifteen or sixteen years old—I was hooked on playing jazz from then on. Before that I did everything else any other young guy would do. I listened to all the R&B stuff and everything like that, but from that moment on that was pretty much it for me.

AAJ: What music did you start listening to right away to study the vibes? Did you start with Lionel Hampton and move on to Milt Jackson and then Bobby Hutcherson?

SN: Oh, well it was Milt Jackson or nothing with this guy because he was a Milt Jackson lover in the greatest sense. Milt was his main man, so everything was Milt Jackson with him. So, I really got most exposed to Milt Jackson with him, so that was the main person on vibes I was listening to, but of course through meeting him and starting to learn how to play, I met a lot of other musicians in town, so it kind of blossomed into a thing where I started listening to everyone, to put it in a wide range.

AAJ: Did you start working right away, playing professionally on vibes?

SN: It didn't take me very long, because at that time, at around that age, I actually had just dropped out of high school, so I had nothing but time on my hands [laughs], so I just went into it full force. I didn't start working right away, but I would actually say that within about two years—which seems amazing to me now—I wasn't working, but within two years I was making my first jam sessions and everything, at least around town. I had at least gotten good to that point. I definitely would say that after three or four years I started doing gigs around town with local cats.

Who else? Actually, Tommy Turrentine had come in, back to Pittsburgh around that time, so I met him and played with him, actually in Kenny's band. Him and Kenny Fisher—he knew Kenny quite well. I mean there were tons of cats around. Roger Humphries, of course was around. Different pianists; who I can't remember all the guys' names. A guy named Jesse Kemp, he was a fine player. He was around. There were tons of cats. Eric Kloss, of course, was around Pittsburgh around that time. I did quite a few jam sessions and stuff with him. There was a little scene still in Pittsburgh around that time. Nothing like the earlier years of course, but there were still a few things going on.

AAJ: Opportunities to cut your chops.

SN: Yeah, opportunities to cut your chops and just learn the basics of the music. I think I learned most of my standards, a lot of the standards, from the guy I was telling you about. Then as I met a lot of the younger musicians I started getting into more into the things that Miles was doing and everything around that time. I got exposed to the Four & More (Columbia/Legacy, 1964) album and just tons of things that guys do who are coming up. You know, it was about the usual evolution of a young jazz musician I would say. I was real fortunate, I would say, that there was still a relatively active scene around Pittsburgh at that time, so it enabled me to work around town a little bit. Then Nathan Davis actually came on the scene a little later, so I played with him a bit.

AAJ: How did you make the move from being a high school dropout to getting a college degree in music education?

SN: [laughs] Actually, I have a Master's in music performance.

AAJ: From Rutgers?

SN: From Rutgers, yeah. Well, around that time my brother lived up in New Jersey, in New Brunswick. So, I was trying to find some direction and stuff, trying to figure out what to do and I wanted to come to New York, so my brother said "Well come on up and hang out with me, 'cause I'm close to New York and we'll go there and hang out and whatever, at least. At that time Rutgers was just starting their jazz program and I actually—my brother took me over to their campus to hang out one day and I sat in with some cats. Who was over there—Larry Ridley and Ted Dunbar, Kenny Barron—and I went over and sat in. They were having an outside jam session, I took my vibes over there— actually my brother took me over there, so I actually owe most of it to him, the whole education thing—and sat in with the cats and that was the beginning of it.

I guess they kind of liked what I was doing and they wanted to get me into the program, which was a fledgling program at that point. They were really trying to get people in, so they made quite easy for me to get in. So that's how I really got started on the scene in New York, man, because I had met all those cats—Freddie Waits was around there—it was just fate or something that I was there—you know Kenny Barron was there. Eventually I wound up playing in Freddie Waits' band—he had a band called Colors Revealed around that time—and eventually ended up playing with Kenny's band, too. I met James Spaulding there and did a lot of things with him and really got fed into the scene through that whole experience.

AAJ: You had played with Grant Green before that?

SN: Yeah, when did that happen? Somewhere in the interim there, around the time that I was still active in Pittsburgh, a little bit before I came up to New Jersey. It was around that area of time, anyway. There was a guy in Pittsburgh who is from Pittsburgh, another guy, named Jerry Byrd, who you might know; he plays a lot with Freddie Cole. I knew Jerry from Pittsburgh and we had done a lot of gigs around Pittsburgh together and had another one of those unofficial bands together. He knew Grant Green very well and Grant always used vibes in his band around that period; he always had a vibes player and his vibes player had broken his leg, or something like that and Jerry actually recommended me for that gig with Grant. So, I went with Grant and that was kind of my first road experience. It was only about a year or so that I stayed with him, so it wasn't extensive, but it was quite an experience to be next to that guitar.

AAJ: Did that bring you to the point that you heard the record Idle Moments (Blue Note, 1963) and were exposed to Bobby Hutcherson?

SN: No because at that time—I actually heard Idle Moments later—at that time that was in that period, man, where cats were into, you know cats like Lou Donaldson were into Alligator Boogaloo and all that stuff, so there was a little bit of a different vibe, even though we did play ... every night we'd play like a set of straight ahead tunes, but we'd also play sets of—I don't know what you would call it ...

AAJ: Funky stuff.

SN: Yeah.

AAJ: So you came to New York via your experience with the Kenny Barron and Spaulding and the rest of the Rutgers crew?

AAJ: I'm sure Curtis just heard you and snatched you right up. He's always been quite the talent scout. He must have gotten that from his years with Betty Carter?

SN: I can't remember. I believe it must have been through the Jeffries brother that we met.

AAJ: Okay, Darryl and Duane, who were promoters at the time.

SN: Yeah, in the original Horizon.

AAJ: Is that where you first met Mulgrew [Miller] also?

SN: Mulgrew and I actually met a little later, even though I had known about him. We met a little later, but actually it was through Rutgers, too, in a sense, because we met through Bill Fielder, who knows Mulgrew very well. He actually brought Mulgrew up to Rutgers one day and we played all day, man, and that was it. From the first time that we played together it was magic, man, and we've been playing together ever since. We immediately hooked up musically; we synced so perfectly that I knew that we were going to be playing together for a long time. So, that's how I originally met Mulgrew—I can still remember that same day, actually, but even then the years go by and you forget how things came about and how they developed and everything, but eventually Wingspan came about and we've been doing it ever since. But that's how I met him through William Fielder.

AAJ: Who else were you playing with when you first came to the New York area?

SN: I was thinking about Donald Brown, as well. There was a period there where I was recording more with Donald than anybody else. I think I've did about five records with him, so I was always doing a project or something with Donald and that was really one of my main recording experiences was with him. All through those records Early Bird (Sunnyside, 1987), Cause and Effect (Muse, 1991)—I think there's one called Cartunes (Muse, 1993); there's one we did with Alan Dawson called, I think The Sweetest Sounds (Jazz City, 1988). You know, I did a lot of recording stuff with Donald.

AAJ: How did you meet Donald? Did you meet him through Mulgrew?

SN: I actually think I met Donald through James [Williams] and that's why I wanted to discuss James, too. All during that period there, I guess it was the period around the eighties, mid-to-late eighties, I did a lot of playing with Donald and also with James, who I think introduced me to Donald. You know, all up in Boston, mostly, at those clubs The Willow, Sculler's and those kind of clubs and James used to play gigs up there all the time and call me for them and he and I and Alan Dawson did a lot of those gigs and John Lockwood would do them. I think that's where I first met Antonio Hart; it was up there, up in Boston he came and did one of those gigs with us. That was a whole network in itself because I had met James and James introduced me to Donald. Then I met Billy Pierce up there and Lockwood and [Bill] Mobley and all of those guys. So the whole relationship with James was real important because I met a lot of cats and played a lot of great music.

James had written a lot of great tunes that we played, so I actually wanted to make sure I said something about that. That was before the I.C.U. thing that he had started. That was all just before that. After that I think he got kind of busy with that band, so I didn't play with him as much, but before that played with James quite a bit. And Donald as well, doing things on the road; go up to Claremont Farond and play. We'd do quite a lot of stuff together. So those two cats, Donald and James, were definitely important cats along the way.

AAJ: They're both great writers, too.

SN: Absolutely!

AAJ: So you got to play some music you hadn't played before while playing with them.

SN: Play a ton of music I hadn't played before. They had very large books, man, they both were cats that were always writing music and their books were thick [laughs] with tunes. So, that was a great thing.

I think a little before that—I had always wanted to play with Jackie McLean—he was on my list, man, of players I had wanted to play with so bad and I had never gotten to play with and I must have put some positive energy out there 'cause lo and behold one day I got the call to do his date. So that was one of the greatest experiences for me— to do that.

AAJ: That was the Rhythm Of The Earth (Antilles, 1992) record.

SN: Yeah, Rhythm Of The Earth, yeah, with Steve Davis and the guys. So that was just a tremendous experience for me just to be hanging out with Jackie at the rehearsals and stuff and to do that date, so that was also ...

AAJ: You said you wanted to talk a little about Bobby Hutcherson's influence on your playing. Had you heard those records with Jackie and Bobby? Was that part of the reason you wanted to play with Jackie so badly?

SN: No, I just always loved Jackie's playing and his style and everything, so that ... I just loved Jackie's swinging, the way he swung so hard, man. That's really why I wanted to get a chance to play with him, because I just loved the way he played—his whole approach to playing. But Bobby, you know, the first time I heard Bobby I wasn't even all that hip to him. I knew him, I knew about him—I loved his playing, but I wanted to go hear him at the Vanguard one week, a long time ago. He had brought some cats in from the west coast and that week I think I went every night and he blew me away every night. And that's when I really started getting into Bobby and getting all the records, is when I went down to the Vanguard and sat down in front of him and heard him play. Each night I couldn't believe what I was hearing and had to come back the next night and the next night, until I finally realized that it wasn't that he was just having a good night [laughs], that was how he always.

AAJ: Do you feel that Bobby's influence caused you to make specific alterations to your own approach to the instrument?

SN: No doubt, I'm sure it did. It was a pretty logical progression though, you know, from Milt to Bobby, but I'm sure my playing opened up a lot more in terms of, you know, more open kinds of harmonies and things like that, you know, it had a big influence on me in terms of being much more open to different sounds and stretching the harmonies and things like that, which Bobby does so well. So yeah, it changed my playing, no doubt about it. You know, you pass through all your influences and things and hopefully you squeeze your own style out of there somewhere, but Bobby was a huge influence on my playing for sure, so I couldn't ... you can't go through an interview without mentioning Bobby Hutcherson, if you're a vibes player, no matter who you are.

AAJ: Getting back to your playing experience, you were with David "Fathead Newman's band for quite a while.

SN: That was a long period that I worked with Fathead. He was another one of those cats from a certain era who had developed their own sound that's immediately recognizable. I played in his band for about five years. Playing with someone with that kind of experience, it's like the learning experience is ... like they don't teach you verbally, the learning experience is just listening to them play every night, listening to the sound, number one, which he had, which is so distinctive, you know, the sound, the feeling, his playing.

There're many things you can learn from Fathead, man. He used to play and he always would, you know, he would take what was there when he played a solo. That's what I learned from him. You know in jazz sometimes the spirit is there with you and sometimes it's just not there. If it wasn't there, he'd bow out after three or four choruses, but if he struck up a groove, you know, and it was there, he could take about thirty choruses, just riding the groove, but he always knew exactly when to end a solo and when to take another chorus or a few more choruses, you know, he had that kind of intuitive knowledge and experience.

That's the kind of thing you can only get from playing with a cat like that and just listening to how they do that. If it wasn't happening after five choruses or so, he might bow out. The next solo he might take about thirty choruses and ride the wave. So it was great to check that out, not to mention that he was advancing his playing, too, all the while I was with him. I'd hear him more and more going for different things in fourths and stuff, so even from his era he was always experimenting around. Yeah, that was another great experience and always swinging.

AAJ: At first your membership in his group seemed like a bit of strange choice, but then thinking of the Ray Charles connection between both him and Bags made it seem perfectly logical.

SN: That's a good point.

AAJ: And that band did dig in very deep into some grooves.

SN: Yeah man, [laughs] we got some great grooves. We had some marvelous weeks at the Vanguard with Kirk and Eddie Gladden, the late Eddie Gladden. Yeah, we had a ball, so you know I enjoyed playing with Fathead for all those years and everything. And we would always play together, you know, if we were playing a ballad I could always kind of weave things around him and everything, while we were playing. He'd be playing the melody and I'd be kind of playing inside and outside of what he was doing. It was a good hook up,

AAJ: Is that where you first played with Kirk?

SN:

No I first played with Kirk—there used to a club in the Village called

the Jupiter Café—now I'm going way back—on 10th Street—I don't know what

year it was, but that's when I first played with Kirk. I remember that

because I think we played duo that day. Yeah, that's when I first met

Kirk Lightsey because I remember I was carrying my vibes down the street

[laughs]. First time I ever saw Kirk I was carrying my vibes and I

dropped my pedal on the street there—on 10th Street there—and I looked

back and Kirk Lightsey was behind me and he said, "Don't worry about it,

I got your back. [laughs] and he picked up my pedal. For some reason I

always remember that was my first Kirk Lightsey experience. That's where

I first met Kirk, at the Jupiter Café and then later we played together

in Fathead's band and I can't remember ... oh yeah, [bassist] David

Williams did a lot of those gigs with us, too, on bass.

SN:

No I first played with Kirk—there used to a club in the Village called

the Jupiter Café—now I'm going way back—on 10th Street—I don't know what

year it was, but that's when I first played with Kirk. I remember that

because I think we played duo that day. Yeah, that's when I first met

Kirk Lightsey because I remember I was carrying my vibes down the street

[laughs]. First time I ever saw Kirk I was carrying my vibes and I

dropped my pedal on the street there—on 10th Street there—and I looked

back and Kirk Lightsey was behind me and he said, "Don't worry about it,

I got your back. [laughs] and he picked up my pedal. For some reason I

always remember that was my first Kirk Lightsey experience. That's where

I first met Kirk, at the Jupiter Café and then later we played together

in Fathead's band and I can't remember ... oh yeah, [bassist] David

Williams did a lot of those gigs with us, too, on bass. AAJ: You also worked with George Shearing, which is a classic kind of role for a vibraphonist, since he had one of the first groups where the vibes were integrated into the whole sound of the band.

SN: Yeah, I can't even remember how I got that gig, but I worked with George for about a good three years. That was one of his last quintet bands. He had disbanded the quintet for a while. I think he was just playing duos mostly with Neil Swenson on bass and then he brought it back with Red Schwager, actually Louis Stewart first, the Red Schwager, on guitar, Dennis Mackrel [on drums] and myself. So you know, that was a whole other experience; that was a thing of subtlety. The dynamic level was just a whisper, so you really had to get inside the other person's sound and really sync up with what the band was doing because a lot of things had to be played in unison together. So that was another great experience and another lesson kind of in understatement and subtlety with George for those three years, which I thoroughly enjoyed. We played some great music and some great arrangements and just to be part of that sound was really nice for that time. So that was another really good experience.

AAJ: Did that cause you to go back and explore Cal Tjader and the sound of that group of George's with him?

SN: Well ... I'll tell you, I had already loved Cal before I even met George. Cal Tjader is actually one of my favorite vibists, you know. I love Cal Tjader's sound and I love him for the fact that he maintained his own style, all the time—separate from Milt and Hamp and Gary Burton and Bobby and everybody. He had his own concept and his own style and he always maintained it, so I always really enjoyed Cal Tjader's playing. He's one of the underrated vibes player out there, really. So I heard him before George Shearing, but yeah he did play with George. Most vibes players that you know by name probably did play with George at one time or another. A ton of them anyway—Gary Burton, Emil Richards, a lot of vibes players—Buddy, Montgomery—a lot of cats played with George. So that's another great band that I had the pleasure to play with. Not to mention all the other great musicians from my generation that I got to work with over the years, like Mulgrew and Lewis Nash and Peter Washington and all the cats I kind of came up with. Bobby Watson, Kenny Washington, all those cats. Playing together all these years, they've all been big influences on my playing

AAJ: After playing with a lot of pianists—Kenny Barron, Mulgrew, James Williams, Donald Brown, Kirk Lightsey, George Shearing—on your own recordings—and then you wound up in a piano-less band. How did you hook up with Dave Holland?

SN: I met Dave through Tony Reedus, actually. We did a record, I believe it was Tony's first record and, I guess to show you how the network had been set, I had met Tony in Wingspan, he had been playing with us in Mulgrew's band at that time and he decided to do his own record. He got a chance to do his own record and he had Dave on it. I can't remember the tenor player's name who ...oh yeah, Gary Thomas was on it; and some other people. I met Dave and we hooked up pretty well, we hooked up, but Tony actually had that idea for the vibes in the rhythm section there like that, playing four mallets. He wanted that in there, so that's we kind of did on that CD, as I recall. And I think that Dave, Dave heard that and me and Dave synced up real well and so Dave called me in to do some rehearsals after that with his band. I remember the first rehearsal. I was pretty much stumbling over myself and I didn't know if I would get the gig or not, but apparently he heard something in there that he liked and thought would work with the band, so he called me back to play with the band and that was it. But that's how I met Dave, through that gig with Tony Reedus.

AAJ: Was that one of the rare occasions that you played a gig without a piano up until that time?

SN: Well, you know, I have to say that when I first came around New York, I did that quite a bit because a lot of the things, even with Horizon, the early Horizon, we didn't have a piano all the time. Sometimes it was just me, Bobby, Curtis and Smitty, or Kenny Washington, sometimes we'd work without a piano. And then Mickey Bass, I played with his band around that time, too. And I played without piano with him, too. I met Wynton in that band; quite a few cats—Carter Jefferson came through that band and different guys. That's where I met Robin Eubanks, actually, through Mickey Bass. So, I had done some before, as well. A little bit in Pittsburgh, too. Sometimes, in this business you had to do it because the joints didn't always have pianos or the pianos were so terrible that it necessitated doing that. So, I had done a bit of it around town, but with Dave it was much more extensive.

AAJ: The role of your instrument changed a bit in Dave's band. In the other groups you were more or less playing the part of a pianist, whereas in Dave's band you blossomed into a different kind of player.

AAJ: Later the group expanded into a big band, which was really different—to have a big band with the vibes as the only chordal instrument.

SN: There are times when I make the mistake of saying that that's never been done before, but of course vibes have been in big bands before—whether it was Hamp leading a big band and Bobby on the thing with Dexter, where Slide wrote all the parts for Bobby. And there were other cats, too, but I just don't know if vibes have ever been used in that sense in a big band before. The big band in that way is an extension of the quintet—of Dave's quintet—to a large degree. So the use of the vibraphone in that big band is—is pretty unique, I'll just say that. I'm always hesitant to say something's never been done because somebody will tell me that somebody else did it in some year or other, but it's unique in that sense. And the marimba is in there and things like that. I think it makes the big band quite a unique experience, having the vibes in there.

AAJ: How do you think that your playing has changed through your years of experience with Dave?

In Dave's band, one of the things that happens, is that you have so much room in there to express yourself that you can't help but to try out a lot of new ideas and work out a lot of different rhythms and try out a lot of different harmonic structures and things behind the soloists—see if they like it or not and you discard it if they don't. He gives you so much room as a bandleader to do those things, and it's a relatively small band so everybody has room to play. So you certainly grow in terms of material that you gain just from experience as you go on. Probably there are many sounds that I've experimented with, especially with four mallets and things, that I may not have had a chance to do if I didn't have that kind of room, that kind of open room in that band. Because the thing with that band is that it's all about the interplay between the cats, between the musicians, so there's plenty of room for group improvisation and things like that, so you have a lot of room to express yourself.

But having said that, like I say, the root of it, the thread of it, goes right back to Pittsburgh, still. I'm the same kind that came up through Pittsburgh, that's trying to learn how to play. So hopefully that always comes through; the blues always comes through and melody always comes through in my playing.

AAJ: I did feel, hearing you with Kirk Lightsey at the

Jazz Standard last week, that there was more of an emphasis on group

improvisation than there would have been ten years ago. Your approach to

the instrument seems to be more bold in terms of your willingness to

play behind other soloists.

SN: That might be

true. It's a funny thing, after playing that week with Kirk, I'm so much

wanting to play with him again because I actually think that there

could be more of that. I did more probably, in terms of group

interaction and things, than I may have done at one point, but in a

weird kind of way Kirk has some of the same energy that Dave has. He

gives you a lot of space, too, and he expects you to take it and do

something with it. So, I did some of that in terms of interplay with

him, because he likes to keep the music going; rather than stop and call

tunes, he likes to keep a continuous thing happening, so there's a lot

of segues and interludes and things and those are the areas where

there's a lot of interplay and I feel like I could have been even more

open to that. So, as you say, I probably did more of that than I would

have in the Bradley's years, but I could have been even more open and

done more.

Which brings me to an important point, which is if

you have a band, you can explore more things. That's the great thing

about playing with Dave Holland. We have a band, so I can say this to

you—that I wish I would have explored more things—and then we'll have

another tour, another tour next month and I'll have a chance to do those

things. That's the beauty of having a working band.

AAJ:

Do you like being a sideman? You don't work as a leader very often. Do

you have ideas for leading a group that you want to put into play?

AAJ: You came up learning on the bandstand. These days most jazz musicians learn in the classroom, which you did also. So, you kind of have one foot in each camp. How do you feel about the growing trend of jazz becoming an academic music?

SN: Well ... I don't know. I can honestly say that; in the final analysis, I really don't know. In my case, I was left a lot alone to my own devices for many years before I started school. So I started out learning from the all the cats around town in Pittsburgh in a very, very hands on kind of way, man. I mean the guys would actually take their hands [laughs] and put them on the keys on the piano and say "no, put this finger here and this finger here, for this voicing, etcetera. That's the grounding, that's the roots that I got, so when I came to Rutgers everything was placed on top of that, but I already had the raw materials and the basis because of the background that I got coming up in Pittsburgh and actually that what the cat's saw, I think—what Kenny Barron and all those guys [at Rutgers] saw. They said, "Well he's already got the basic thing going, so he's worth spending the time to mold some more because he's already got a basis going.

The problem comes in, of course, now that there's not such a scene in the cities any more, where guys just don't get that basic training anymore, of coming up and learning from the old cats, cats you never even heard of, you know, the legendary cats in each town. I'm not so sure that there is so much of that anymore, so cats are going directly into the educational system and that's where they're trying to get their base and I think that's part of the problem—they don't have a strong connection to the roots of the music anymore except from an educational institution. But, I mean who's to say? There are fine young players out there, who seem to keep thriving and doing quite well and playing their ass off. So there is something to be said for the fact that...no one is able to say what order you should do things in. Maybe you can go to school and cop that and come out and round yourself off later. It's just not the way that I did it.

AAJ: Is there anything that we haven't talked about that you want to say?

SN: Oh man, Russ, you got so much material here that you could write a book about me.

AAJ: Well that's good because there hasn't been very much written about you up until this point. It's not like I had to spend a lot of time doing research for the interview. There's just not a lot to look up.

Selected Discography

Steve Nelson, Fuller Nelson (Sunnyside, 2004)

Dave Holland Big Band, Overtime

Mulgrew Miller and Wingspan, The Sequel (Max Jazz, 2002)

Steve Nelson, New Beginnings (TCB, 1999)

Bobby Watson, Jewel (Evidence, 1983)

Kenny Barron, Golden Lotus (Muse, 1980)

Top Photo: Jos L. Knaepen

Center Photo: Alan Nahgian

Bottom Photo: Frans Schellekens

https://www.post-gazette.com/ae/music/2009/12/03/Vibraphoning-home-Steve-Nelson-returns-for-rare-Pittsburgh-concert/stories/200912030515

Vibraphoning home: Steve Nelson returns for rare Pittsburgh concert

You might not recognize the name Steve Nelson unless you're a hard-core jazz fan. Or a jazz musician. Plenty of his colleagues know and appreciate the East Liberty native's virtuoso vibraphone playing -- they call on him regularly to tour and record. From stints with pianist Kenny Barron and sax man David "Fathead" Newman to globe-trotting with ex-Miles Davis bassist Dave Holland, Nelson has made his success mainly as a sideman.

"I'm lucky that I've always been working and been involved in projects with someone or another," the 55-year-old Nelson says on the phone from his home in Patterson, N.J., which offers a quick commute to New York's clubs. "I've been blessed even if I'm not famous or anything, because I have the respect of my peers. And that is what enables you to work more than anything else in this business."

With: Mulgrew Miller, piano; Ivan Taylor, bass; Rodney Green, drums.

Where: Kelly-Strayhorn Theater, East Liberty.

When: Saturday 8 p.m.

Tickets: $20 advance, $25 at the door; www.brownpapertickets.com or 1-800-838-3006

More information: www.kentearts.org

One place Nelson hasn't worked much since he left town in the '70s is Pittsburgh. He can recall only one gig here since then, with Holland at the Manchester Craftsmen's Guild. So his homecoming Saturday at the Kelly-Strayhorn Theater in East Liberty leading a quartet is cause for excitement -- especially among his family.

"My mother still lives in Pittsburgh. She's in Shadyside now. She's lived all her life in Pittsburgh. She has like five sisters, and they all have children in Pittsburgh. My father, who is deceased, he had uncles and aunts and nieces and nephews and cousins. I predict that the concert hall will be overflowing with family members."

Nelson's family was living on Rowan Street in East Liberty when he was born. They moved to Wilkinsburg when he was 15 or 16.

"I dropped out of high school. I don't think I ever made it through 10th grade, man. Fortunately, that coincided with my ascent into music. I had a lot of time on my hands so I practiced a lot. I wish that the concept of art high schools was available then, because I think it would have made a big difference in my life. But it all worked out."

Nelson's epiphany came when he heard his friend's dad, one George Monroe, playing the vibraphone in the Monroe family's basement.

"From the moment I heard him play, that was it. It was like a moment I'll never forget. I knew that was what I wanted to do."

Monroe, a performer before taking a job in a mill, taught Nelson and introduced him to his musical pals.

Nelson began playing around town in saxophonist Kenny Fisher's band, most frequently at an East Liberty club called the Diplomat. Fisher passed away on Oct. 25 at the age of 69. Nelson is dedicating the concert to him.

"He was a great tenor saxophonist," Nelson recalls. "He's another one of those guys that played in Pittsburgh but didn't make it out, but he certainly could have. He used to come over to my house and pick me up and we would make gigs at the Diplomat. The Crawford Grill was still happening then, and we played different concerts all around town."

Through Fisher, Nelson got to play with drummer J.C. Moses, who had recorded with Kenny Dorham and Eric Dolphy, and trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, brother of sax star Stanley Turrentine. Nelson played a few gigs with drummer Roger Humphries, who personifies Pittsburgh jazz to this day. Nelson would sit in with Spider Rondinelli on drums and Eric Kloss on sax at a club called Sonny Day's. Nathan Davis, then starting up jazz studies at Pitt, fielded a band with Nelson, Moses, trombonist Nelson Harrison (formerly with Count Basie), bassist Mike Taylor and pianist Vince Genova.

Pittsburgh guitarist Jerry Byrd, who went on to play with Freddie Cole (Nat's brother), referred Nelson to Grant Green, a nationally known guitarist. Green gave Nelson his first touring experience.

A year or so later, Nelson passed his G.E.D. exam and then began earning a master's degree in music performance at Rutgers University. Nelson's brother, a lawyer, was studying law at Rutgers at the time.

"My brother was instrumental in getting me into Rutgers. He went down to the program there and said, 'My brother is searching for some direction and he wants to play jazz.' And [bassist and program founder] Larry Ridley said, 'Well bring him down and we'll hear him and see how he does.' And that's how I got into Rutgers, I went down and played for those cats."

It was around that time that Nelson first heard live performances by Bobby Hutcherson, the adventurous vibes player who backed post-bop greats such as Herbie Hancock and "free jazz" musicians such as Archie Shepp. Nelson remembers hearing Hutcherson at New York's Village Vanguard and then going back for each night of his five-night stand. Hutcherson and Milt Jackson, the vibraphonist who brought the instrument into the bebop era, are Nelson's two biggest influences.

The faculty at Rutgers boasted name jazz musicians including Kenny Barron, drummer Freddie Waits and saxophonist Frank Foster. Nelson reached what he calls his "first big milestone" when Barron asked Nelson to play in his band.

"That put me in the New York clubs -- Sweet Basil and Fat Tuesday's, and I'm playing with Buster Williams, Kenny Barron, Ben Riley and all these great musicians, and all the great musicians are coming in to hear them. So I'm meeting everybody. And everyone is getting a chance to hear me.

"Later on when I did get with Dave Holland, that's when more acclaim started to happen. That's when I started traveling all over the world. That's when things really opened up for me."

The list of places where Nelson has played with Holland includes South Africa, Australia, Iceland, all over Europe and Scandinavia, Argentina, Ecuador, Chile, China and Greenland. (Yes, Greenland.)

Over the years, Nelson has recorded a half dozen albums as a leader -- "Sound-Effect" and "Full Nelson" among them -- more mainstream fare than the music he's recorded as a sideman with Holland and others.

But Nelson doesn't seem to seek center stage -- no Facebook page, no Twitter account. Doesn't he want to call the tunes, take the largest slice of the pie, have 8,974 virtual friends?

"I want to get more of my own things going, but most of my focus is just on really learning how to play the instrument better," he responds. "There's probably a million things about the business aspect that I should be doing better.

"But it hasn't really hurt me so far in terms of what I want to do. I'm playing great music with great musicians, and I'm enjoying it. And I have such focus on just trying to play the instrument better now, that my focus becomes less on advertising and less on promotion as I get older. In other words," he says with a laugh, "I don't know if it's going to change."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Nelson_(vibraphonist)

Steve Nelson (vibraphonist)

Steve Nelson (born August 11, 1954) is an American jazz vibraphonist and marimba player. In addition to his solo work, Nelson is known for collaborating since the 1990s with bassist Dave Holland's Quintet and Big Band.

Nelson graduated from Rutgers University with both master's and bachelor's degrees in music, and his teaching activities have included a position at Princeton University.[1]

He has appeared at concerts and festivals worldwide and has made

recordings as the leader of his own group. He has performed and recorded

with Kenny Barron, Bobby Watson, Mulgrew Miller, David "Fathead" Newman, Johnny Griffin, and Jackie McLean.

Discography

As leader

- Full Nelson (Sunnyside 1990)

- Communications (Criss Cross 1990)

- Sound-Effect (HighNote, 2007)

- Stratocluster with Bruno Vansina (W.E.R.F. 2012)

- Brothers Under the Sun (HighNote, 2017)

As sideman

With Dave Holland

- Dream of the Elders (ECM, 1995)

- Points of View (ECM,1997)

- Prime Directive (ECM, 1998)

- Not for Nothin' (ECM, 2000)

- What Goes Around (ECM, 2002)

- Extended Play: Live at Birdland (ECM, 2003)

- Overtime (Dare2, 2005)

- Critical Mass (Dare2, 2006)

- Pathways (Dare2, 2010)

- Still Hard Times (Muse, 1982)

- Heads Up (Atlantic, 1987)

- Fire! Live at the Village Vanguard (Atlantic, 1989)

- I Remember Brother Ray (HighNote, 2005)

- Life (HighNote, 2007)

- The Blessing (HighNote, 2009)

With others

- Kenny Barron, Golden Lotus (Muse, 1982)

- Donald Brown, People Music (Muse, 1990)

- Cyrus Chestnut, There's a Sweet, Sweet Spirit (HighNote, 2017)

- Billy Drummond, Native Colours (Criss Cross, 1992)

- Ray Drummond, Continuum (Arabesque, 1994)

- Geoff Keezer, Trio (Sackville, 1993)

- Jonny King, Notes from the Underground (Enja, 1996)

- Mulgrew Miller, Wingspan (Landmark, 1987)

- Mulgrew Miller, Hand in Hand (Novus, 1992)

- Houston Person, The Melody Lingers On (HighNote, 2014)

- Houston Person, Something Personal (HighNote, 2015)

- Chris Potter, Imaginary Cities (ECM, 2015)

- James Spaulding, James Spaulding Plays the Legacy of Duke Ellington (Storyville, 1977)

- Chip White, Harlem Sunset (Postcards)