SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2020

VOLUME NINE NUMBER ONE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SULLIVAN FORTNER

Ali was born and raised in Philadelphia. His mother sang with Jimmie Lunceford and his brother, Muhammad Ali, was also a drummer who later played with Albert Ayler. Ali, his brother, and father converted to Islam. He began his musical career in the U.S. Army. After returning from the service, he played with local Philly R&B groups, including Big Maybelle, before moving on to play jazz with locals Lee Morgan, Don Patterson, and Jimmy Smith.

In the early '60s, Ali moved to New York and became a fixture on the avant-garde "new thing" jazz scene. Besides joining saxophonist Sonny Rollins' band for a tour of Japan in 1963, he regularly backed up the efforts of pioneers such as Don Cherry, Pharoah Sanders, Paul Bley, Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon, and Albert Ayler. It was during this period that Ali made his first major recording debut on Archie Shepp's On This Night, and on the Marion Brown Quartet's self-titled offering. The drummer sat in with John Coltrane's group at the Half Note and other clubs around Manhattan. The saxophonist recruited Ali for his large-group free jazz project Ascension, and praised the drummer for his ability to play "multi-directional" rhythms, providing the soloist maximum freedom. But Ali dropped out shortly before the session. Coltrane didn't give up and hired the drummer to play in the expanded lineup for Meditations, but Tyner was dissatisfied with the album and the live setup: He claimed he couldn't hear himself with two drummers. He left after the album was finished and Jones followed him out the door in 1966. The saxophonist's wife Alice Coltrane became the group's new pianist and Ali its drummer.

In late February of 1967, the saxophonist met Ali at Rudy Van Gelder's New Jersey studio. It was a week after the band had cut the music that would be released as Stellar Regions in 1994. He never told Ali this would be a duo session. The melodies Coltrane employed with Ali referenced those found on the Stellar Regions material, and in fact, they often overlap: the selection "Venus" has the same melody as the title track of the previous album, while "Mars" quotes the melody of what later became known as "Iris." Fatefully, Interstellar Space was shelved after Coltrane's passage in 1967. Ali headed for Europe and gigged in Copenhagen, Germany, and Sweden before studying with Philly Joe Jones in England. In 1968 Ali returned to the States and played on Alice Coltrane's A Monastic Trio, Jackie McLean's 'Bout Soul, and Marion Brown's Why Not? In 1969 he continued with Alice on Huntington Ashram Monastery and played on Alan Shorter's Orgasm in between trips to Europe.

In 1970, Ali began trying to improve the lot of jazz musicians, especially their ability to control their own music, receive its proceeds, and find venues to work in. He briefly joined Gary Bartz's NTU Troop for the album Home for Milestone. He continued working with Alice on Journey in Satchidananda as well, and formed Survival Records in 1971 to issue his own recordings. He made his last recording with Alice, Universal Consciousness, in 1971. The following year Ali founded Ali's Alley, a club for non-commercial and "loft" jazz acts until 1979. In 1973, Ali and Frank Lowe issued Duo Exchange, the inaugural offering from Survival, a set of spontaneous sax and drum jams that gained positive reviews.

1974 saw the official release of Interstellar Space. The original album featured four tracks: "Mars" (titled "C Major" in the ABC/Paramount session sheets), "Venus" (titled "Dream Chant" in the session sheets), "Jupiter," and "Saturn." Two more tracks from the session, "Leo" and "Jupiter Variation," later appeared on the compilation album Jupiter Variation in 1978. A 2000 reissue collected all of the tracks from the session, including false starts for "Jupiter Variation." Ali felt validated at long last, given the overwhelmingly positive reviews of the set, but otherwise quietly went about doing his own thing. He released more albums for Survival including 1973's Rashied Ali Quintet with James Blood Ulmer, New Directions in Modern Music with Carlos Ward, Fred Simmons, Stafford James, and Moon Flight (unreleased until the '90s) and Swift Are the Winds of Life, a 1975 duo offering with violinist Leroy Jenkins.

Ali participated in a "Dialogue of the Drums" concert with Milford Graves and Andrew Cyrille in the mid-'70s. He kept a low profile in the '80s aside from drumming in the James Blood Ulmer/George Adams/David Murray group Phalanx. In 1984 he played a live duo gig with bassist Jaco Pastorius; it was issued as Blackbird nearly a decade later. In 1989 Ali resumed recording under his own name with Rashied Ali in France (Blue Music Group).

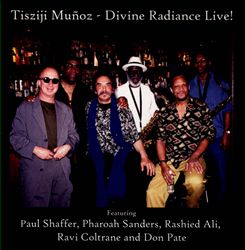

That same year, the drummer began an extensive recording and working relationship with guitarist Tisziji Munoz that resulted in the release of a dozen albums between 1997 and 2003 and three more after Ali's death in 2009. They include four 1997 dates: River of Blood, Present Without a Trace, Spirit World, and Alpha-Nebula. All but the last one featured Sanders (Munoz's former boss). Three more appeared in 1999 including Presence of Truth, Presence of Joy, and Presence of Mastery. Five additional albums were issued between 2000 and 2003, including Breaking the Wheel of Life and Death, Parallel Reality (with Ravi Coltrane), Hu-Man Spirit, Shaman-Bala, and Divine Radiance. The latter featured Ali in the company of both Ravi and Sanders bassist Cecil McBee, and pianist Paul Shaffer. Ali's double album Judgment Day was recorded in February 2005 with Jumaane Smith on trumpet, Lawrence Clark on tenor saxophone, Greg Murphy on piano, and Joris Teepe on bass. It was cut at Ali's Survival Studio. In addition to his performance activities, Ali mentored young drummers.

In 2007, Ali recorded Going to the Ritual for Porter in duo with bassist/violinist Henry Grimes. They played five duo concerts between 2007 and 2009 and a sixth in June 2007 with pianist Marilyn Crispell. A second duo recording was in post-production at the time of Ali's death from a heart attack in August 2009. Before his passing, Ali was the featured drummer on saxophonist Azar Lawrence's album Mystic Journey, released in 2010, just after Spirits Aloft, the second duo outing with Grimes.

In 2013, Munoz released Divine Radiance Live with the same lineup that played its studio date. Rashied Ali's Survival Records label was relaunched in 2019. Its two maiden releases were expanded vinyl-only reissues of the complete Duo Exchange sessions and Live at Slugs captured in 1967. These and future Survival releases will be overseen by Ali's widow, Patricia.

Rashied Ali

Rashied Ali

Rashied Ali is a progenitor and leading exponent of multidirectional rhythms/polytonal percussion. A student of Philly Joe Jones and an admirer of Art Blakey, Ali developed the style known as “free jazz” drumming, which liberates the percussionist from the role of human metronome. The drummer interfaces both rhythmically and melodically with the music, utilizing meter and sound in a unique fashion. This allows the percussionist to participate in the music in a harmonic sense, coloring both the rhythm and tonality with his personal perception. By adding his voice to the ensemble, the percussionist becomes an equal in the melodics of collective musical creation rather than a “pot banger” who keeps the others all playing at the same speed. Considered radical in the 1960s and scorned by the mediocre, multidirectional rhythms, polytonal drumming is now the landmark of the jazz percussionist.

A Philadelphia native, Rashied Ali began his percussion career in the U.S. Army and started gigging with rhythm and blues and rock groups when he returned from the service. Cutting his musical teeth with local Philly R&B groups, such as Dick Hart & the Heartaches, Big Maybelle and Lin Holt, Rashied gradually moved on to play in the local jazz scene with such notables as Lee Morgan, Don Patterson and Jimmy Smith. Early in the 1960s the Big Apple beckoned, and soon Rashied Ali was a fixture of the avant-garde jazz scene, backing up the excursions of such musical free spirits as Don Cherry, Pharoah Sanders, Paul Bley, Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon and Albert Ayler. It was during this period that Rashied Ali made his first major recording “On This Night,” with Archie Shepp, on the Impulse label, and began to sit in with John Coltrane's group at the Half Note and other clubs around Manhattan.

In November 1965 John Coltrane decided to use a two- drummer format for a gig at the Village Gate; the percussionist Trane chose to complement the already legendary Elvin Jones was Rashied Ali. Thus began a musical odyssey whose reverberations are still felt in the music today—Trane probing the outer harmonic limits and changing the melodic language of jazz while Rashied Ali turned the drum kit into a multirhythmic, polytonal propellant, helping fuel Coltrane's flights of free jazz fancy. The rolling, emotion-piercing music generated by the Coltrane/Ali association is still being discussed, analyzed, reviewed and enjoyed in awe as the new compact disk format introduces the era to a new host of the sonically aware.

After Coltrane's passing in 1967, Rashied Ali headed for Europe, where he gigged in Copenhagen, Germany and Sweden before settling in for a study period with Philly Joe Jones in England. Upon his return from the continent, Rashied Ali resumed his place at the forefront of New York's music scene, working and recording with the likes of Jackie McLean, Alice Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Gary Bartz, Dewey Redman and others too numerous to mention here. In response to the decaying New York jazz scene in the early 1970s, Rashied Ali opened the loft-jazz club Ali's Alley in 1973 and also established a companion enterprise, Survival Records.

Ali's Alley began as a musical outlet for New York avant- garde but soon became a melting pot of jazz styles. Although the Alley closed in 1979, its legacy continues in the New York jazz scene and Rashied Ali has been busy gigging with a virtual Who's Who in jazz, refining his music and encouraging a host of younger musicians.

In the '80s and '90s, his presence on the scene was sporadic; he performed on occasion with saxophonist Makanda Ken McIntyre, and recorded with multi- instrumentalist Zusaan Kali Fasteau and tenor saxophonist David Murray. In 1987 he recorded as a member of the group Phalanx. In 1991, he made the critically acclaimed album “Touchin' on Trane,” with bassist William Parker and tenor saxophonist Charles Gayle. The '90s found Ali leading the band Prima Materia, an ensemble dedicated to interpreting the late works of Coltrane and Albert Ayler.

He released “No One in Particular” on Survival Records in 2002.There is an excellent review of this recording by David Adler here at 'all about jazz.'

He remains actively touring, and is a constant source of inspiration for younger drummers.

After performing with John Coltrane, drummer Rashied Ali (shown here) started Survival Records with saxophonist Frank Lowe during the early 1970s. (Photo: Courtesy Survival Records)

Although the legendary jazz drummer Rashied Ali is best known for his work as one of John Coltrane’s pathbreaking late-career collaborators, his next steps after Coltrane’s abrupt passing in 1967 also are rich with creativity. A central node in the New York loft scene through his stewardship of Ali’s Alley, the drummer also co-founded Survival Records with saxophonist Frank Lowe in the early 1970s.

Just over a decade since Ali’s passing in 2009, Survival has been revived under the supervision of the drummer’s family. Two new reissues—Ali and Lowe’s Duo Exchange: Complete Sessions and the Rashied Ali Quintet’s First Time Out: Live At Slugs 1967—are available as limited-edition double-LP vinyl sets, as well as digitally via Bandcamp. Both recordings are a beginning of sorts for the label, and each is full of remarkable musical activity: Duo Exchange was the imprint’s first release, and First Time Out documents Ali’s first performance as a bandleader.

After both musicians had earned a reputations as key sidemen for

avant-garde jazz projects, Ali and Lowe started Survival Records to

release their first album as co-leaders; it was recorded in fall 1972

and released the following year. The album uses the expressive

drums-and-sax duo format that Ali had honed with Coltrane—but before it had received wide acclaim when Interstellar Space was released

in 1974.

One benefit of the small-group format is that listeners have ample time to hear Ali’s full range of drumset capabilities—during the solos, especially, he flourishes as an improvising storyteller. Lowe, too, takes full advantage of the solo spaces, unleashing everything from screams and howls to Sonny Rollins quotes. Although the album would be worthwhile if it only included t-he solo sections, these two are at their best playing together, conveying intimacy and creativity as they share energy and draw from one another’s ideas.

This double-LP includes previously unreleased outtakes that help frame the full process that went into making the original album. The alternate takes of “Exchange Part 1, Movement II” are especially instructive in getting a sense of the shared understandings that underpin the pieces. And the warmup fragments that open the “D” side of the album—each performer making a powerful skronk that tests whether the engineer is ready and able to record—make it clear that these guys came to play.

After releasing Duo Exchange, Ali took primary responsibility for stewarding the label, turning toward his own back catalog. First Time Out is the first item in this archive, documenting a May ’67 date of Ali’s at the renowned East Village club Slugs.

The bandleader’s drum solos are absolutely gripping throughout; each time his number is called, he shifts effortlessly from an energetic accompanist into a sharp, dynamic tone poet. Ramon Morris, a tenor saxophonist best known for his later work on the Groove Merchant label, shows energy and endurance throughout. Pianist Stanley Cowell is low in the mix but always consistent; listeners who only know his playing through his work on the Strata-East label might be surprised by some of his far-out excursions. But Dewey Johnson’s lyrical interpretation of “Ballade” is a powerful surprise, to which Ali and the trumpeter offer emotive underscoring as an attentive rhythm section. Reggie Johnson’s bass solos also stand out for their virtuosity, presence and originality.

The purposeful and heartfelt quality that the ensemble conveys is a striking testament to the generative edge that can result from the right combination of open-eared musicians and loose, spacious compositions—which became Ali’s calling card. And in keeping with the “energy music” aesthetic of the loft scene, the musicians really go for it during the open spaces that highlight featured soloists.

Unfortunately, the full performance wasn’t documented—the tape cuts off abruptly amid a captivating bass solo on “Study For As-Salaam Alikum,” just as Ali begins to take over. But there’s more than enough tape here to get a sense of the powerful free-jazz movement that was beginning to flourish in Manhattan. DB

This story originally was published in the May 2020 issue of DownBeat.

https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2009/08/the_revolutions_of_drummer_ras_1.html

The Revolutions Of Drummer Rashied Ali

Rashied Ali, pictured here in 2008, died on Wednesday.

Drummer Rashied Ali has died. A simple note on his Web site, as well as an e-mail from his manager, confirms the news.

When he was with us, from time to time Rashied would play in a group called By Any Means -- a trio with bassist William Parker and saxophonist/pianist Charles Gayle. As Parker explained to me and WBGO's Simon Rentner after the set, the band's goal was "to incite human and spiritual revolution through art ... We are not restricted by style, by sounds. You know, you use any sounds, you use any key, use any rhythm, you use any idea to promote and get where you're going." In practice this meant largely a freely improvised music that wove in and out of patterns both recognizable and foreign.

The relative few at the By Any Means trio set at the Newport Jazz Festival this year did not see Rashied Ali there; his brother Muhammad Ali was subbing on drums. I saw Roy Haynes approach the bandstand after the show, pleased to be seeing Muhammad, but inquisitive about the whereabouts of his more famous sibling. I would imagine Rashied was not in a good way on Sunday at 5 p.m. ET; according to his manager, he had been admitted to the hospital last Thursday with a mild heart attack. Just when he was about to be released, he died almost instantly of a blood clot.

I was going to write at length about free jazz at Newport this year -- the Vandermark 5 was there too -- and perhaps I still may. But as of this moment, it seems empty to think about that without acknowledging Rashied's legacy.

Ali gave much that was great into the world. In addition to the By Any Means trio, there were his several records with Alice Coltrane, his extensive discography period, his loft space/venue Ali's Alley, his own Survival Records. (Someone one day needs to devote some serious study to 1970s loft spaces and early musician-owned record labels more in depth.) I recall receiving his latest albums on Survival, Judgment Day Vols. 1 and 2, as the jazz co-director at WKCR in New York, and noting that in spite of amateur packaging, Ali still was creating some vital, interesting music. Not quite hard-bop, not quite free jazz, it was raw and fresh and very much of the now.

But when the dust settles, he'll be chiefly remembered for being John Coltrane's last drummer, the fellow who replaced Elvin Jones when Trane was looking to take his music even further into the nether regions. And he always carried on the legacy of the heavyweight champion. It's telling that the title of By Any Means' greatest recorded document is called Touchin' On Trane. Plus, WBGO has a 55-minute duet with Sonny Fortune on Coltrane's "Impressions"; this is from 2004, nearing 40 years after Trane's passing. Which has clear echoes of this:

Mars

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/111850946/94880567" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

"Mars," from John Coltrane, Interstellar Space. John Coltrane, tenor saxophone; Rashied Ali, drums. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: February 22, 1967

Like many, the Coltrane and Ali duet album Interstellar Space was a key to me understanding John Coltrane's much talked-about later work. So much sound, man. What glorious din he produced, seemingly acting as the furnace apparatus behind Coltrane's passionate, gut-level screeching. I still have trouble believing that was just one drummer. Having met and seen Rashied perform as recently as two years ago, I now have trouble believing he left us before I could see him again.

But you know what? He did incite a personal revolution, at least for this listener. And whatever comfort that can offer to his friends, family and collaborators, I'm glad for.

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/14/arts/music/14ali.html

Rashied Ali, Free-Jazz Drummer, Dies at 76

Rashied Ali, whose expressionistic, free-jazz drumming helped define the experimental style of John Coltrane’s final years, died Wednesday in Manhattan. He was 76.

The cause was a heart attack, said his wife, Patricia Ali.

Mr. Ali, who first encountered Coltrane in their Philadelphia neighborhood in the late 1950s, made the leap from admiration to collaboration in the mid-1960s, when he joined Elvin Jones as a second drummer with Coltrane’s ensemble at the Village Gate in November 1965.

Mr. Ali recorded with Coltrane and Jones on the 1965 album “Meditations” and, after replacing Jones as Coltrane’s drummer, on the duet album “Interstellar Space” (1967), one of the purest expressions of the free-jazz movement.

“I didn’t know what it was, but he called it multidirectional rhythms,” Mr. Ali said of his drumming in an interview for the documentary “The World According to John Coltrane” (1990). On Mr. Ali’s Web site, rashiedali.org, Rashid Ali's Web site his playing is described as “a multirhythmic, polytonal propellant, helping fuel Coltrane’s flights of free-jazz fancy.”

Mr. Ali was born Robert Patterson into a musical family in Philadelphia. He started out on piano and dabbled with trombone and trumpet before finding his way to the drums, which he began to play seriously while serving with Army bands during the Korean War. Perhaps thanks to his military experience, he always executed drumrolls with crisp precision.

On returning to Philadelphia, Mr. Ali played in local rhythm-and-blues and rock ’n’ roll groups before moving on to jazz. He studied with Philly Joe Jones and paid close attention to heroes like Max Roach and Art Blakey, but a turning point came when he listened to Coltrane’s recordings with Jones. “Instead of being a timekeeper drummer, I wanted to play more,” he recalled for the Coltrane documentary.

Mr. Ali moved to New York in 1963 and began playing with progressive jazz musicians like Don Cherry, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp and Albert Ayler. His first important recording was with Shepp on the album “On This Night.”

After pestering Coltrane to be allowed to sit in with his group at the Half Note jazz club and eventually getting a chance one evening, Mr. Ali passed up the golden opportunity to perform as a second drummer with Jones on the album “Ascension,” the seminal record of the free-jazz movement. He later realized his mistake and accepted second-drummer status at the Village Gate and on “Meditations.”

After Coltrane’s death in 1967, Mr. Ali performed with Alice Coltrane and then toured Europe. Returning to New York, he opened a club, Ali’s Alley, in a building he bought in SoHo, then in its early bohemian phase. The club, a showcase for free-jazz musicians, was at the center of the loft jazz scene of the 1970s. It operated until 1979, and Mr. Ali lived in the building for the rest of his life.

From the 1980s until his death, Mr. Ali performed and recorded with several avant-garde groups, including Phalanx, By Any Means and Prima Materia, an ensemble devoted to interpreting the music of Coltrane and Ayler. Most recently he appeared with the Rashied Ali Quintet, which he formed in 2003, and performed as a duo with the saxophonist Sonny Fortune.

Besides his wife, he is survived by two brothers, the jazz drummer Muhammad Ali and Theodore Patterson, both of Philadelphia, and nine children.

“He could play straight, put down the time and swing,” the critic Stanley Crouch said. “He had a good command of his instrument. He once told me that he thought of himself as playing in 4/4, but the other realms of 4/4 that we don’t usually hear.”

https://jazztimes.com/features/tributes-and-obituaries/rashied-ali-2/

Rashied Ali

7.1.35 – 8.12.09

One afternoon last summer I was performing at the City Winery in Manhattan with the fine young trumpeter Michael Rodriquez and his quartet. Midway through our set I noticed Rashied Ali take a seat with a friend near the bandstand. After one of the tunes I went to the side of the stage to say hello. He acknowledged my greeting with a few polite words but he was eyeing the bandstand with a definite intention. He wanted to play and I wanted him to play. A chance to hear and watch a master is always a welcomed opportunity.

“Man, I sure would like to play those beautiful drums!” he said.

I quickly answered, “Sir, I sure would love to have you play them!”

So Rashied dashed to the stage and took a seat behind my Craviotto drum set. Michael called “Moment’s Notice” and they were off. It was wonderful to hear Rashied offer his wonderful feel and sound to the proceedings. An additional delight was to have him christen my drums and cymbals with his vibrations.

After the set we visited a bit more and he gave me a copy of his latest recording, the Rashied Ali Quintet’s Live in Europe. It features my friend, bassist Joris Teepe, who was grateful to be in Rashied’s band. It was indeed a spirited ensemble that was not afraid to align and collide, swing and stretch or soothe and burn.

On Aug. 13 I was enjoying listening to WKCR. They were playing some various late John Coltrane explorations that were definitely beckoning the spirits. Then they announced that Rashied Ali had passed the day prior. I was in shock. I phoned the station to find out details and at that time they were unaware of the circumstances. I later discovered that he had suffered a heart attack and seemed to be recovering fine. Unfortunately, while he was preparing to go home from the hospital, he had another heart attack that took his life. I was deeply saddened. He looked so great when I saw him just a month earlier.

I became aware of Rashied’s artistry through an ABC Impulse! box set entitled The Drums that my brother gave me as a Christmas gift around 1978. The recordings and extensive liner notes gave this then 14-year-old farm boy living in Illinois great insight into the wide range of the jazz-drumming legacy. The Drums exposed me to Sid Catlett, Kenny Clarke and Roy Haynes, but also Ed Blackwell, Milford Graves, Sunny Murray and Rashied. I recollect the impact of hearing him on a selection with Alice Coltrane called “Gospel Trane.” He had a swinging cymbal beat and approach that allowed an ebb and flow with the time feel. I was unaccustomed to hearing that kind of flexibility. I dug how liberating it seemed to be part of the flow of the music, not just a steady timekeeping presence.

In college we would check out later recordings of John Coltrane with Rashied Ali like Meditations and Live in Japan. I remember listening to Live in Seattle while traveling with the Either/Orchestra and being overwhelmed, and a bit terrified, by the power of the music. Rashied propelled the explorations with a relentless intensity. His range of expression extended beyond the tangible. I first saw Rashied play live with the band Prima Materia at the Knitting Factory. It was amazing to witness his intimate physical relationship with the drum set. His focus allowed his ideas to flow effortlessly through his limbs and the sound he offered lifted the music.

I have to admit that I only recently really checked out Interstellar Space, Rashied’s legendary duet recording with John Coltrane. I feel a sensory connection beyond the aural when listening to that recording. I can see, smell and taste the sound! In any situation, Rashied’s sonic dimensions welcomed you deep inside the music, whether it was an intense flurry of energy, a deep groove or a sparse landscape. He swung with a pulse delivered through his cymbal or through polytonal bursts of propulsion. You felt a big picture pulse field in whatever he played.

Beyond his instrument, Rashied Ali was devoted to the values of freedom and personal expression. From 1973-1979 he maintained Ali’s Alley, an influential free-jazz loft club in New York. He also had his own label, Survival Records, that produced numerous recordings.

All of these elements made Rashied Ali an invaluable contributor to the jazz community. His dedication will remain a source of inspiration for generations of improvisers.

Graded on a Curve: Rashied Ali, First Time Out: Live at Slugs’ 1967 and Duo Exchange: Complete Sessions

The farther we travel forth in time, the more the belief is encouraged that 20th century music history is set in stone. Upon chiseled tablets, inquisitive minds can ascertain events and achievements that unspooled tidily like fallen lines of dominos leading to the dawn of the 21st and right up to our current moment. But two new releases featuring drummer Rashied Ali, one in duo with saxophonist Frank Lowe, take the idea of a settled music history and explode it to sweet kablooey: First Time Out: Live at Slugs’ 1967 and Duo Exchange: Complete Sessions are out now, each on double vinyl, through Survival Records.

Indeed, music history is far from codified as the progressions that define it were far from neat. One of the niftier byproducts of vinyl’s resurgence (perhaps a better term is physical product’s resurgence, as the phenomenon includes an upsurge in cassettes, multi-format box sets with books, and yes, the against the odds endurance of the compact disc) is the increased spotlight material tangibility has shed upon uncovered works by complete unknowns and of course, entities with varying heights of profile.

The latter is the case with First Time Out: Live at Slugs’ 1967, which offers nearly 92 minutes of live performance by Rashied Ali’s Quintet that would’ve been lost except for the discovery of two 7-inch tape reels in the drummer’s private recording library. In the tersely informative notes for the release, Ben Young and George Schuller, who produced the set along with Patricia Ali, and Joe Lizzi, who mastered the recording, date the shows to May of 1967, just a few months after Ali was captured in duo with John Coltrane for Interstellar Space, though that session wouldn’t be issued until 1974.

If Ali was known in 1967, it was likely due to his role in Coltrane’s band, which he joined in ’65, initially flanking and then replacing Elvin Jones. Ali also played on Archie Shepp’s terrific On This Night from ’65 and was a member of Marion Brown’s quartet for two swell ESP-Disk albums recorded in ’65-’66. Ali’s releases as a leader didn’t begin surfacing until the ’70s, with this new, early vantage point a major facet in First Time Out’s allure.

The band is a mixture of established names and more obscure figures. Next to Ali, the highest profile player is pianist Stanley Cowell. He played with Ali on Marion Brown’s ESP sets, as did First Time Out’s bassist Reggie Johnson, though not at the same time (the prolific Johnson is on The Marion Brown Quartet, while Cowell is on the follow-up Why Not?).

Trumpeter Dewey Johnson (no relation to Reggie, I don’t think) is an important but undersung name in free jazz, as he played in the large band for Coltrane’s historic Ascension recording and was part of the October Revolution in Jazz, with his participation on Barrage by the Paul Bley Quintet a direct extension of that involvement. The biggest surprise here is saxophonist Ramon Morris, who later recorded in a soul-jazz context for the Groove Merchant label.

Here, Morris gets pretty deep into post-Coltrane search mode, which is appropriate for this band and the locale. Slugs’ (initially Slugs’ Saloon) was a club in Manhattan’s East Village, a key spot for the then thriving NYC avant-garde jazz scene. Coleman played there, as did Ayler and Sun Ra. Young mentions the likelihood that Ali assembled the band quickly to fill a last-minute opening in the club’s schedule, and listening to the four side-long tracks, each over 22 minutes long, that observation seems exactly right.

This and the roughness of the audio means that First Time Out shouldn’t be anybody’s introduction to the work of Rashied Ali, though that’s not to undercut the specialness of the set overall. A term used in the notes is under-rehearsed, which is to say that this wasn’t a working band (assembled in a hurry, again), but as First Time Out isn’t a post-bop scenario, it doesn’t matter as much as you might think.

Instead, it opens up a doorway into the sort of day-to-day activity that transpired in between the epochal events and cornerstone recordings which form the history of the avant-garde jazz movement. Bands were formed for gigs and ideas were shared as possibilities were explored. First Time Out delivers an extended immersion into this sort of “everyday” environment, and the occasional roughness (and general non-pro quality) of the recording, which under normal circumstances is far from preferable, formulates a verité quality that as the four sides progress evinces a particular appeal.

Make no mistake, smoother audio would still be ideal, as would a complete take of “Study for As-Salaam Alikum” (which abruptly ends just as an Ali drum solo gets going), but the inspired nature of the interaction does shine through. First Time Out offers an extended series of snapshots of everyday jazz activity, but there is nothing humdrum about it.

In fact, as it plays, the consistency of the emotional investment led me to think of Valerie Wilmer’s outstanding jazz book As Serious as Your Life, which was first published in 1977 (imagine my pleasant surprise when I discovered that the 2018 edition of that book by Serpent’s Tail press features a cover photo by Wilmer of none other than Rashied Ali).

And the rawness of the audio only intensifies the fact that, in contrast to the then moderate (and declining) commercial plateaus of the ’60s post-bop biz (including the polite applause garnered in the more typical jazz clubs of the period), this was music made because the players deemed it an essential path of discovery. With this said, don’t get the idea that this is a feature film-length dive into wildly blown skronk and clatter, as side two’s “Ballade” explores the contemplative side of this group.

“Ballade” still fits securely into the avant-jazz mode of exploration, but it contrasts pretty sharply with the high intensity assault that’s heard on Duo Exchange: Complete Sessions. However, this edition of the record (with a new cover photo by none other than Val Wilmer), which was the first release on Ali’s Survival label (initially a joint venture between he and Lowe) and by extension a foundational document in free-jazz’s transition to self-reliance in the ’70s “loft era,” offers more than what’s ever been heard before from this session, with this expansion considerably broadening the record’s reach.

The original edition of Duo Exchange was released a year prior to Interstellar Space, and it’s important to stress how crucial this Ali-Lowe collab was to the proliferation of the instrumental duo lineup in jazz. It comes after Ali and Lowe’s roles in Alice Coltrane’s band of ’69-’71, and as the notes to this edition illuminate, the band of saxophonist Frank Wright as guests during a late 1972 performance at Artist House in NYC. Other than in Ali’s memory of the earlier session with John Coltrane (and the Impulse execs who were then sitting on the tapes), there was basically no precedent for a horn-drum duo in jazz.

And so, Duo Exchange is a total groundbreaker, but for more reasons than one, as the raw lung fury of Lowe points forward to saxophonist Charles Gayle (he was on the scene in the late ’60s but went unrecorded until decades later, another instance of jazz history documented through oral reportage); Ali played with him on the 1991 masterpiece Touchin’ on Trane. That was a live trio session with bassist William Parker, who’s debut on record came on Frank Lowe’s Black Beings, issued in 1973 by ESP-Disk.

Black Beings, like Duo Exchange, was later reissued with additional material. Once a wild tandem sprint (not a title fight) of high energy, Complete Sessions transforms it into an even more enriching experience. Up above I stated the Ali’s quintet session here shouldn’t serve as an introduction to his work, but upon consideration there are insights to be gleaned by starting the journey with the ’65 Slugs’ recording. Do you want to understand what it’s like to be free? Spend some time with First Time Out and then proceed directly to Duo Exchange. You’ll receive some major clues.

First Time Out: Live at Slugs’ 1967

A-

Duo Exchange: Complete Sessions

A+

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rashied_Ali

Rashied Ali

Rashied Ali, born Robert Patterson (July 1, 1933 – August 12, 2009)[1] was an American free jazz and avant-garde drummer best known for playing with John Coltrane in the last years of Coltrane's life.[2]

Biography

Early life

Patterson was born and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His family was musical; his mother sang with Jimmie Lunceford.[3] His brother, Muhammad Ali, is also a drummer, who played with Albert Ayler. Ali, his brother, and his father converted to Islam.[4]

Starting off as a pianist he eventually took up the drums, via trumpet and trombone. He joined the United States Army and played with military bands during the Korean War. After his military service, he returned home and studied with Philly Joe Jones,[1] then toured with Sonny Rollins.[5]

Career

Ali moved to New York in 1963 and worked in groups with Bill Dixon and Paul Bley.[3]:171 He was scheduled to be the second drummer alongside Elvin Jones on John Coltrane's free jazz album Ascension, but he dropped out just before the recording was to take place.[1] Coltrane did not replace him and settled for one drummer. Ali recorded with Coltrane beginning in 1965 on the album Meditations.

Among his credits are the last recorded work by Coltrane (The Olatunji Concert) and Interstellar Space, an album of duets recorded earlier in 1967. Ali "became important in stimulating the most avant-garde kinds of jazz activitie,"[6] playing what Coltrane described as "multi-directional rhythms".[7] After Coltrane's death, Ali performed with his widow, pianist Alice Coltrane.[1] During the early 1970s, he ran Ali's Alley, a loft club in New York City.[8]

He was a visiting artist at Wesleyan University, sponsored by Clifford Thornton. He also briefly formed a non-jazz group called Purple Trap with Japanese experimental guitarist Keiji Haino and jazz-fusion bassist Bill Laswell. Their album, Decided...Already the Motionless Heart of Tranquility, Tangling the Prayer Called "I", was released by Tzadik Records in March 1999.

In the 1980s, he was member of Phalanx, a group with guitarist James Blood Ulmer, tenor saxophonist George Adams, and bassist Sirone. From 1997–2003 he played extensively with Tisziji Munoz in a group that usually included Pharoah Sanders.

Though known for his work in jazz, Ali contributed to other experimental art forms, including multi-media performances with the Gift of Eagle Orchestra and Cosmic Legends, performances such as Devachan and the Monads, Dwarf of Oblivion, which took place at The Kitchen Center for Performance Art, and a tribute to John Cage in New York's Central Park. Other artists of the orchestra and Cosmic Legends have included Hayes Greenfield (sax), Perry Robinson (clarinet), Wayne Lopes (guitar), Dave Douglas (trumpeter), Gloria Tropp (vocals), Louise Landes Levi (sarangi)director/pianist Sylvie Degiez along with poets and actors Ira Cohen, Taylor Mead, and Judith Malina.

Later life

In the last years of his life, Ali led his own quintet. A double album entitled Judgment Day was recorded in February 2005 and features Jumaane Smith on trumpet, Lawrence Clark on tenor saxophone, Greg Murphy on piano, and Joris Teepe on bass. This album was recorded at Ali's own Survival Studio, which has been in existence since the 1970s. In addition to his performance activities Ali served as mentor to young drummers such as Matt Smith.

In 2007, Ali recorded "Going to the Ritual" in duo with bassist/violinist Henry Grimes with a second duo recording in post-production at the time of Ali's death. Ali and Grimes also played five duo concerts together between 2007 and 2009 and a sixth concert in June 2007 with pianist Marilyn Crispell. Ali is the featured drummer on Azar Lawrence's album Mystic Journey, recorded in April 2009 and released in May 2010.

Rashied Ali died at age 76 in a Manhattan hospital after suffering a heart attack.[9][10] He is survived by wife Patricia and three children.

Discography

As leader

- 1971 – New Directions in Modern Music (Survival, reissued by Knit Classics) with Carlos Ward, Fred Simmons, Stafford James

- 1972 – Duo Exchange (Survival, reissued by Knit Classics) with Frank Lowe

- 1975 – Swift Are the Winds of Life (Survival, reissued by Knit Classics) with Leroy Jenkins

- 1973 – Rashied Ali Quintet (Survival, reissued by Knit Classics) with James Blood Ulmer

- 1974 – Moon Flight (Knitting Factory)

- 1975 – N.Y. Ain't So Bad (Survival, reissued by Knit Classics)

- 1989 – Rashied Ali in France (Blue Music Group)

- 1994 – Peace on Earth: The Music of John Coltrane (Knitting Factory) with Prima Materia and guests John Zorn, Allan Chase

- 1995 – Meditations (Knitting Factory) with Prima Materia, including Greg Murphy

- 1995 – Bells (Knitting Factory) with Prima Materia

- 1999 – Rings of Saturn (Knitting Factory), duets with tenor saxophonist Louie Belogenis

- 2000 – Live at Tonic (DIW) with Wilber Morris

- 2008 – Going to the Ritual (Porter) with bassist Henry Grimes

- 2009 – At the Vision Festival with Greg Tardy, James Hurt, Omer Avital (Blue Music Group)

- 2009 – Eddie Jefferson at Ali's Alley with Eddie Jefferson (Blue Music Group)

- 2009 – Configurations, the Music of John Coltrane with Prima Materia (Blue Music Group)

- 2009 – Cutt'n Korners with Greg Tardy, Antoine Drye and Abraham Burton (Blue Music Group)

- 2010 – Spirits Aloft (Porter) with bassist Henry Grimes

- 2020 – First Time Out: Live At Slugs 1967 (Rashied Ali Quintet)

As sideman

With Gary Bartz

- Home! (Milestone, 1970)

With Peter Brötzmann

- Songlines (1991)

With Michael Bocian

- "Go Groove"" (1991)

With Marion Brown

- Marion Brown Quartet (1966)

- Why Not? (1967)

With Alice Coltrane

- A Monastic Trio (1968)

- Huntington Ashram Monastery (1969)

- Journey in Satchidananda (1970)

- Universal Consciousness (1971)

With John Coltrane

- Meditations (Impulse!, 1965)

- Live in Japan (Impulse!, 1966)

- Live at the Village Vanguard Again! (Impulse!, 1966)

- Interstellar Space (Impulse!, 1967)

- Stellar Regions (Impulse!, 1967)

- Expression (Impulse!, 1967)

- The Olatunji Concert: The Last Live Recording (Impulse!, 1967)

- Cosmic Music (Impulse!, 1968)

With Charles Gayle

- Touchin' on Trane (FMP, 1991 [1993])

With Jackie McLean

- 'Bout Soul (Blue Note, 1967)

With Tisziji Munoz

- The River of Blood (Anami Music, 1997)

- Present Without A Trace (Anami Music, 1997)

- Spirit World (Anami Music, 1997)

- Presence of Truth (Anami Music, 1999)

- Presence of Joy (Anami Music, 1999)

- Presence of Mastery (Anami Music, 1999)

- Breaking the Wheel of Life and Death (Anami Music, 2000)

- Parallel Reality (Anami Music, 2000)

- The Hu-Man Spirit (Anami Music, 2001)

- Shaman-Bala (Anami Music, 2002)

- Divine Radiance (Anami Music, 2003)

- Divine Radiance Live! (Anami Music, 2013)

- Paul Shaffer Presents: Tisziji Muñoz – Divine Radiance Live! DVD (Anami Music, 2013)

- Sky Worlds (Anami Music, 2014)

With David Murray

- Body and Soul (1993)

With Phalanx

- Original Phalanx (DIW, 1987)

- In Touch (DIW, 1988)

With Archie Shepp

- On This Night (Impulse, 1965)

With Alan Shorter

With James Blood Ulmer

- Music Speaks Louder Than Words (DIW, 1996)

References

- "Le batteur de jazz Rashied Ali est mort". fr: Citizenjazz.com. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

External links

https://www.artsjournal.com/jazzbeyondjazz/2009/08/rashied_ali_1935_-_2009_multi.html

Howard Mandel's Urban Improvisation

Rashied Ali (1935–2009), multi-directional drummer, speaks

A 1990 interview with drummer Rashied Ali, about his relationship with John Coltrane.

In 1990 I interviewed drummer Rashied Ali for The World According to John Coltrane, a documentary produced and directed by Toby Byron. It was the first but not the last time I spoke to Ali, a sorely underrated musician and jazz presence who died yesterday (August 12, 2009) following a heart attack at age 74. Here’s a transcript of our talk, slightly edited and annotated, mostly about Coltrane, with whom Ali became famous. He describes hearing the saxophonist practicing at his mother’s home in Philadelphia, how he first began to play with Coltrane, Trane’s dedication to improving his instrumental skills, their tour of Japan, of dreaming about Coltrane and of their duet recording Interstellar Space. Only excerpts were used in the film.

HM:Rashied, will you introduce yourself for the camera and to me, and sort ofinclude in it how you think of yourself in relationship to John Coltrane.

RA: Well,I’m Rashied Ali, and I play drums and how I can relate myself with John is . . .well, for one thing he put the name on the type of drums I was playing. Ididn’t know what it was, but he called it multi-directional rhythms. Which Ilooked up in the dictionary and found that it means playing three or fourdifferent rhythms at the same time. And I guess I can relate to John as tryingto be the best that I can be in whatever I do. Because just the thing that heseemed to instill on me and on people around him as to try to be really be thebest at what you do. So I can relate that way to him.

HM: You weresaying that as a kid you used to go to his mother’s house in Philadelphia andsit around there?

RA: Well, his mom lived on 33rd Streetright across from the park. It was a section of Philadelphia called Strawberry Mansion.And I lived in that same section. And during the time he was working with MilesDavis we used to, you know, go around to his house just trying to see if wecould see him outside or sitting around. Anywhere. And a lot of times we would just hear him practicing out of his window, so we just sit around the steps and sit around and listen to him practice. Actually to meet him and to talk to himcame years later after I had really got into playing. I met him at a club inPhiladelphia for the first time.

HM: Was he like a local hero of a sort, somebody who was really admired among the young guys?

RA: Yeah, he had something for the young musicians at that time. He was playing a totally different kind of saxophone sound than we had been accustomed to listening to. We were listening to Charlie Parker and Stan Getz even and Dexter Gordon and people like that, you know, and Gerry Mulligan, But Coltrane —he sort of had grown into this new way of playing. It’s hard to explain the way it was but the youngsters got on to it right away. I mean we were listening toit right away. First it sort of seemed strange to us and at first I was going,like, ‘You know, I think I’d rather listen to Dexter Gordon,’ because some ofthe stuff he was playing, I couldn’t really understand what it was. And then after a while listening to him play with Miles Davis, everybody just fell in love with that stuff.

HM: What were these first records that you were hearing, that seemed odd?

RA: The firstrecords that he did with Miles. I was into Miles Davis. I was listening to everything he’d do. Miles came out with his first LP for Prestige Records called Musing With Miles. He just had a jacket on and a hat [in the cover photo] and I think it was Philly Joe Jones and Oscar Pettiford and was there a pianist on it? Red Garland, or one of those people. Well, anyway, Miles came out with this record and then somehow, Miles was looking for a saxophone player and Philly Joe Jones came from Philly and introduced him to ‘Trane and then ‘Trane got with Miles and they started doing these records on Prestige, Workin’ and‘Round Midnight. No, I think that was on Columbia Records. But Workin’ anda few other good records [Cookin’, Steamin’, Relaxin’] that came out of there[Prestige]. That’s when I heard Trane the first time that really made an impression on me, when I heard him play with Miles on those records and that’s when I started looking for all Coltrane’s records.

HM: Were you already playing by the time you heard Coltrane?

RA: Yeah, I was playing at that time. I started playing drums at a very early age. I was playing drums when I was in high school. So, I knew about Trane even before Miles Davis because I have cousins, well, second cousins, my father’s first cousins —Charlie Rice and Berna [?] Rice who play drums also. They both play drums and they both played around with each other, like Jimmy Heath and Charlie Rice and Coltrane, they all played together, so like, I’d always heard of him through that source. But I never got a chance to really see him play until I got into playing myself.

HM: Even when you were listening to his records, did the music that Miles and Coltrane play effect how you played the drums?

RA: Yeah,it definitely effected my playing. Because I was very influenced and still am— well, not very influenced now, but I learned a lot from listening to people like Max Roach and Art Blakey. Max Roach had a hot band in those days with Clifford Brown, and Blakey, he just had one hot band after another with that Jazz Messengers. Between those two, I was listening a lot to the way they played drums. But then when I hear Coltrane play with Elvin Jones…now I had heard him play before with different drummers like Philly Jo Jones and people like that who complemented Coltrane, what he was doing really good, but when Elvin came into the band somehow that was like a Charlie Parker and Max Roach combination. That was like the ultimate combination and that, and listening to Ornette Coleman and different people, it sort of changed my feelings about the drum set. Instead of being a timekeeper drummer, I wanted to play more. You know I wanted to be more freer and play more drums than just being a timekeeper, you know. So, that’s how it influenced me by listening to Coltrane and Elvin Jones play some of those duets that they were playing. When everybody would just drop out, McCoy [Tyner, pianist] would drop out and Jimmy [Garrison, bassist] would drop out and, and Jones and Trane had it. That influenced me quite a bit. I was very taken back by that type of music.

HM: Did you seek out somebody that you could have that kind of partnership with?

RA: Oh,definitely, in fact, I was doing things like that round Philadelphia on my own. I have two brothers who also play drums and we would put bands together, withsaxophone players. We would sometimes just have two sets of drums and three saxophone players for the whole band. We were doing a lot of drums and saxophones and stuff like that — double quartets — like coming from Ornette type of thing [documented on Free Jazz] two groups playing at the same time simultaneously. This was like in the late '50s and early ’60s.

HM: Why was there so much searching going on? Is that something that Coltrane was an example of, looking for things?

RA: He sort of opened things up because he such a relentless player and searcher. He never stopped playing. When I used to go to hear ‘Trane, he would always be playing. He would be playing in his dressing room. He would be playing before he got to me. Just like a fighter would warm up in the dressing room, he’d come out in the ring and he’d be sweating from warming up, he would do the same thing in the dressing room. He would just play and play and play. He would break a sweat in the dressing room and then when he would come out on the bandstand, he had all that — I don’t know where he got that energy from. He was relentless. He was always pressuring the music, I mean trying to get as much out of it as he could. As far as the music was concerned, it was hard to keep up with a person like that. I mean, most people, they play — but with Coltrane, that was all he did. That was every bit of it. He wasn’t into sports; he wasn’t into baseball, basketball. He wasn’t into anything but music. So he just did that all the time, all the time. It was a heck of a thing to be around a person like that. I think I learned a lot from just being around a person that way.

HM: It sounds almost frightening. Sort of like, doesn’t this guy have any other life at all?

RA: He had only music. I mean, I’m sure he had other life, other than music, but for the life of me I couldn’t see anything else that he did except play. He just played all the time. Even when I was with the band. When I was working with the band, he played on the airplane. He had a flute or something. On the train, in the hotel room. You walk in the hotel room you hear this saxophone all up and down the hotel. Everywhere he played, the first thing he wanted to know was would he be able to play, before he even got a place to stay. And they would go, “Oh yeah, sure.” That’s the way he did all the time. You know what? That helped me a lot. You know, to see somebody with that kind of dedication.

He wasalways playing and I think that’s what really got me the most with him. I was heavily influenced by the man’s music, just his music. But then, you know, after I’d seen what it took to be great like that — I mean, it was awesome. He always had an instrument in his hand. He was always playing something. He was always trying to be better than he was and it seemed like, you know, how could he get better? How could he do anything better than that, than what he’s done already? And after playing all these years with all these different people, King Kolax and Eddie Vinson and all these rock and rollers and rhythm and blues artists and jazz artists, the man still had a vision that he could be betterthan he was and he was still practicing. You know, after awhile you stop practicing. This man was in his 40s, right? And he had played with everybody and he was still playing

everyday. So that was a profound statement as far as I was concerned.

When I was younger, I practiced like that — hard, everyday, 12 hours a day. And you know, here I was playing with Coltrane, like I made it. Okay. I was makin’ it. I was playing with Coltrane — but this man was still practicing like he was 20 years old. So that I think that influenced me again. See, I was influenced being around him to try to keep up with what hewas doing and I think that helped me musically.

HM: When you did begin to play as a professional, did you start off with rock and roll and rhythm and blues bands and then played with jazz musicians and then played something that was like

beyond jazz?

RA: I think jazz is like everything else. You learn how to play that and then after you play that you you become who you are. You become yourself, I mean. I’ve heard Coltranewas influenced by people like Dexter Gordon and people like that, you know. AndBird. In fact, he told me himself that when he heard Bird he stopped playingalto saxophone, because he had started playing alto saxophone and he said that when he heard Bird he just didn’t want no part to that horn anymore. Because what Bird was doing with the horn was just impossible for anybody else to do. Sohe stopped playing the alto and picked up the tenor, man. And I thank Bird a thousand times-fold for getting Trane to play the tenor saxophone because whathe did with the tenor saxophone is still being reckoned with today and there are scores of players, I don’t care who they are, if they play the tenor saxophone you can hear a little bit of John Coltrane in them. And it was justthe way he was, the way he lived. He played what he lived, and it was an honor to be around him.

HM: Tell meabout when you first got the call from him to come join the band or howeverthat happened.

RA: I’mgonna tell you, I wanted to play with Trane so bad . . . I was motivated to dothat because I been listening to his records all my life and most of my practie was with Coltrane records. I would just get into my basement and I’d play these records so you could hear him a mile away and I’d be practicing and playing with these records all the time. And so I had a real good idea of what to play with Trane. So I didn’t really get the call, I just sort of put myself into a position to do that. He was working at this club, right down here on Spring St. It was called the Half Note at the time, on Hudson at Spring. Trane had that place for as long as he was in New York; if he wasn’t playing [on tour] he could go there and play for two weeks, three weeks, a month, however long he wanted to. And that’s how he got a lot ofthings together. He would write songs and he would play ’em there for the firsttime to try things out. I would go over there and I would just sit around onthe steps and I asked to play and he said ‘Well, no, not today.’

And I wouldjust sit there and ask again the next night and the next night and the nextnight. One day I just came there and I don’t know, fate, whatever, Elvin wasn’tthere yet and it was time to play and everybody was walking around the stage toplay. And I said, ‘Can I play?’ And he looked at me for a long time and hesaid, ‘All right, c’mon.’ And I went up and I played. I played for a whole setbefore Elvin came, and then I got down. And the next day I was there again andI said, ‘Can I play?’ He said, ‘Sure, c’mon.’ And I played again. And then I went there one time and Elvin seen me coming and he said, ‘C’mon up here and play for me.’ He had to run somewhere and I played again. And then he [Coltrane] asked me, he said, ‘Rashied, I’m gonna do some tapes and I wouldlike for you to play on them with me.’ And I, you know — I’m gonna tell you,

man, I had an ego bigger than this building at that point, playing with Trane. Just sitting in with him just inflated my ego to the point when I was ridiculous. Iwas young, I was ridiculous and I said, ‘Yeah I would like to play. Who else is gonna play?’ He said, ‘Elvin is gonna play.’ I said, ‘You gonna have two drummers like that?’ He said, Yeah,’ and I said, ‘Well, I don’t think I wannaplay with two drummers.’ He said, ‘Oh, you don’t?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t think so.’ So I blew the date, which

turned out to be Ascension.

You heard of that date, right? All my friends like Dewey Johnson, Archie Shepp, LarryYoung, John Tchicai, all these guys made this date and I wasn’t there, behindbeing stupid, right? I go like, ‘Oh, man!’ He was talking about a record datewhen he said tapes. I thought to myself, ‘Whoa, man, you better get ittogether.’ So then after the date, Coltrane went out with Pharoah Sanders, andhe called me up and said came back you know, ‘You know Coltrane’s back and we’regonna play at the Village Gate. You ought to call him up, man.” So, Icalled him up.

I said, ‘Hi ‘Trane.’ He said, ‘Hey Rashied, how you doing?’ I said, ‘You playing at the Village Gate?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘I would love to play with you.’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s fine, you know, but Elvin’s gonna be playing, too.’ I said, ‘Oh, that’s fine. It’s great, I mean, of course, I don’t mind. He said, ‘Okay, have your drums there at eight o’clock. Then that’s it.’ And I learned such a lesson on that, you know. I mean, I don’t have anything bad to say about musicians, hardly ever. Because I feel like you can always learn something from anybody, I don’t care how bad or how good they are. So I learned a lesson on that. My ego sort of got deflated on that one.

HM: What about Elvin? Was he not shaken by your being on the set, too?

RA: Oh,definitely not. Elvin Jones is a creative artist and there was a lot of rumors out at the time that he was upset . . . Well, maybe he might have been a littleupset, but he wasn’t shaken by no point because he’s a great artist and Ilearned a lot from Elvin Jones’ style of drumming. He was one of the direct reasonswhy I play today. It was because of the way Elvin Jones played. I was young and I was into being in a band. It was like going to college, being a sophomore or a freshman in a college. Here I was just coming into the band and I was playingwith people like Jimmy Garrison and then Elvin Jones and McCoy and I was like Ihad to keep up something, you know. I had to feel like I couldn’t show anyweaknesses, you know, because these guys were veterans, they knew everythingand I guess I sort of overreacted to a lot of things. But at the same time I have one hell of a love feeling for Elvin Jones because I think that Elvin Jones’ style of drumming helped me withthe style that I developed.

HM: Why didColtrane want another drummer? What did he hear?

RA: Because he was in a drummer thing. He just wanted to free himself from playing thesestrict changes. The bass player and the piano player would lay these chordsdown, you know, and he played just about everything he could play onthesechords. He played ’em upside down. He’d turn ’em around. He played ’emsideways. He did just about everything he could to ’em. And playing with thedrums he didn’t have to deal with chord changes and keys and stuff like that.So he was free to play however he wanted to play. There were times I played with Trane, he had a battery of drummers, like about three conga players, guys playing batas, shakers and barrels and everything. On one of his records he did that. At the Village Vanguard, live, we had a whole bunch of drummers plus thetraps. And then sometimes he would have double traps. Like in Chicago, I played double traps with a young drummer coming up there, named Jack DeJohnette.

HM: So what are the tours that you went on with Trane? In ’66 you went to Japan, didn’t you?

RA: If I can remember correctly, we did eight or nine concerts in Japan. We started in Tokyo and we went to Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Nagoya…a couple places that I can’t pronounce, and Kyoto. I remember Kyoto because this is the place where they have beer-fed cows to make the steak tender. They feed beer to the cows, that was their thing. But anyway, in Japan, that was a heck of a trip because we played in theaters and they were large theaters and it was unbelievable, the people that came out to hear Coltrane. They packed the theaters. People were sitting in the aisles and on half of the stage. And it was just jam-packed, every concert we did there. Even sneak concerts — when we first went there we had like a preview press conference-concert and that was jammed. So we got a chance to play to a lot of people in Japan, a lot of people.

HM: Why do you think they were so receptive to Coltrane?

RA: Because the Japanese, they have a reputation of being up on everything. And this was in ’67 and they were up on jazz, even in ’67. I don’t know when they got into it, but they had drummachines and all that stuff going on — I remember seeing the first drum machine in Japan when I was there in the ’66. And so, they were just waiting for Trane. When we came offthe airplane, they had life-size posters of us like, you know, like in thesheath, how you carry a flag? They had life-size posters and bigger, cut-out to shape, of each one of us at the airport and then they took a red carpet and rolled a red carpet from the plane into the terminal for Coltrane. That’s the way they did it in Japan.

HM: Have you ever gotten a reception like that anyplace else?

RA: Never, ever, never. And I don’t think it will ever happen again. That was a once in a lifetime situation.

HM: What kind of songs repertoire were you performing?

RA: Mostly all original songs. Coltrane played mostly all original songs. He played ‘Leo,’ he played ‘My Favorite Things.’ It’s hard for me to think of the names of these songs. ‘Living Colors.’ I can’t really think of the names, ‘Meditation,’ ‘Impressions’ and stuff like that, you know. He wrote a lot of new stuff for this band. He tried not to play the same kind of music he played with the previous band. He was doing things from Impressions, Meditations, “Ogunde,” stuff he was doing on the new record that came out as Cosmic Music. Stuff like that.

HM: He was playing a little flute, too, wasn’t he?

RA: Yeah, he had inherited Eric Dolphy’s instruments — the base clarinet and the flutes and so on. Eric’s mom gave him the flutes so he felt that he had to try and learn how to play the flute. He always didn’t want to know how to play it, for some reason. But when he got Eric’s horns, he started playing the flute. He was coming on with that flute, too. I mean, he only had a little while and he recorded with it. It wasn’t gonna be long before he would started playing it but he didn’t live to really get into it. I think he was on his way of becoming a good flutist.

HM: What did you notice about his health?

RA: I never noticed. I didn’t know he was sick. I had no idea he was sick. I knew he was drinking juices and stuff. But he was not the kind of person that complained. Not to me, anyway, about being sick or anything. A few things he said to me to make me think, but I wasn’t hardly listening to it because I just couldn’t see him being sick at all. The way he played on the stage and as much power he used to play the saxophone, I had no idea that he was sick. But I have pictures of him where he had his hands on his liver at times, he was getting pains there. And he complained sometimes about being tired, you know, being not as energetic as he usually was. But that was about the only complaints that I ever got. I was totally in shock when I heard that he had died that morning, July 17, when I had heard about that. I had no idea. In fact, we had just played about twoweeks or a week before that happened. And he was playing strong, but I noticed he was sitting down in a chair so I guess he was a little tired . . . The liver robs you of a lot of energy when it gets on the blink. And, that’s all you know, I just never

really realized that he was sick enough to pass.

HM: Were you close with Alice [Coltrane’s wife, then playing piano with him]? Did the family do anything? What was happening in the musical

community at that point?

RA: What do you mean?

HM: I suppose everybody felt the way you did, like shocked.

RA: Yeah, yeah.

HM: What, what was happening around Alice? What happened to the band?

RA: Well, Alice kept going with the band. She put out this record Cosmic Music, on the John Coltrane label that when it first came out [quickly re-released by Impulse!] And she did a Carnegie Hall concert to open up with the label. And we did that. And then we did a lot of different things as far as playing and recording. We did a lot of recording because Coltrane built the studio right in his basement and so it was just about going out to Deer Park [Long Island, New York] and into the basement and playing, and so we did some recordings there. And she kept it going. But it was a shock. Not only was it a shock to me and the family, it was a shock amongst all the musicians, too. Because nobody had an inkling that he was sick enough to pass.

HM: Do you think about Coltrane often these days?

RA: I dream about Coltrane, vivid dreams, like live dreams. I used to dream about him somuch when he first died I told my mother used to get very nervous about me dreaming about him. She used to always tell me, ‘If he asks you to come with him, don’t go. Refuse to go.’ My mother’s very psychic about that. She says at one point in the dream he’d extend his hand out for me to come and I shouldn’t, because he was supposed to not be here and I was saying, ‘You’re not supposed to be here.’ But the dreams were real and every now and then I dream a real dream about Coltrane and it’s such a real dream until I wake up and I have to really lay there and get it together to make sure that I’m back. Because I would definitely be gone into the dream. I mean, musical dreams. I hear some stuff in dreams that needed written down. I woke up and I would get my pencil out and I would put it down on paper, or put it down on the tape. I could remember the songs that I played. Or heard him play. Or played with him. Yeah. It was very musical.

HM: Tell me something about Interstellar Space, your duet record with Coltrane.

RA: That’s what I was getting to. Interstellar Space was like the ultimate record that Coltrane really always wanted to do, because he loved drums. In fact, he loved drums so much, if we would have a second set of drums on the stage, sometimes he would come up there and play them.

I mean, he would sit behind the drums and play with the band, you know. He really had something about drums that he loved. And to do a record with him, to do acomplete record with him, just as a duo was a big honor for me. In fact, Istill charge up from that record. I can play that record in the morning and it gets me started for the whole day. I just heard that they released some newmaterial that we’d done in Japan on some duet stuff. We just went into the studio for a day or two days and we just played and recorded, just played and recorded. And that’s the way it was. I think that was some of the greatest stuff we ever did, I think.

HM: He would give you structure, you would give him structure or — ?

RA: Ah, hedid the whole thing. He would say what kind of song it is, if it is in three orfour, if it was fast, if it was slow, if it was medium and sometimes he would just say that we’d just play and we would just make things up. We’d play slow for a little while and then I’d speed it up and play faster. He used to always tell me that he could play any kind of way with the way I played drums. He could play fast or slow, it doesn’t matter. Just because I was just always keeping something going, you know. Not necessarily keeping a tempo. You know, just wide open, just keeping it open so that he was free to play. However he felt like, or however he wished.

HM: Thanks, Rashied, that gives us plenty to work with.

RA: It’s over that quick?

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER:

Howard Mandel is a Chicago-born (and after 32 years in NYC, recently repatriated)

writer, editor, author, arts reporter for National Public Radio,

consultant and nascent videographer -- a veteran freelance journalist

working on newspapers, magazines and websites, appearing on tv and

radio, teaching at New York University and elsewhere, consulting on

media, publishing and jazz-related issues. I'm president of the Jazz

Journalists Association, a non-profit membership organization devoted to

using all media to disseminate news and views about all kinds of jazz.

My books are Future Jazz (Oxford U Press, 1999) and Miles Ornette Cecil - Jazz Beyond Jazz (Routledge, 2008). I was general editor of the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Jazz and Blues (Flame Tree 2005/Billboard Books 2006). Of course I'm working on something new.

https://www.jazzweekly.com/interviews/rali.htm

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH RASHIED ALI

I was

really into Elvin because he was the featured drummer on A Love Supreme.

I still am to some degree (having spent a hundred and fifty bucks on his

Mosaic Blue Note box), but when it comes to Trane drummers, I appreciate

what Rashied Ali brought to the table. I can't imagine another drummer

being able to duel with Trane on Interstellar Space. Or how killer is

the practically hour long "My Favorite Things" on the Live in

Japan record? I get the best of both worlds on Meditations (both Ali and

Jones play). Ali continues to pay tribute to Trane's legacy. A classic

Touchin' on Trane (Charles Gayle and William Parker), a fine In the Spirit

of John Coltrane (Sonny Fortune), and a rendition of Meditations with

his Prima Materia band. The force is strong in this one my friends. I

sat down with Rashied and the drummer spoke about his respect for Trane

and his efforts to be the standard bearer, as always, unedited and in

his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning

RASHIED

ALI: Well, actually my family was a very musical kind of a family. My

mother and her four sisters were all piano players and then my grandmother

was a minister and she had a Baptist church, sort of a little, small corner

church. Her daughters sang and played at the church. And my father, he's

a music lover. He's a jazz buff. He likes music. His first cousins, which

were the Rices, Charlie Rice and Bernard Rice, they were both drummers.

Charlie Rice was more professional. He played with people like Dizzy Gillespie

and John Coltrane, people like that in Philadelphia years ago. I just

was around music all my life and so it was just natural that I would be

a musician I guess. I started with piano, but I didn't really get that

far. I learned enough just to read music and play the piano. Then I wanted

to be a trombone player, but I never got that. I wanted to play the trumpet.

I was going through a lot of different changes. Actually, the drums just

really took over being around my cousins and friends that I knew. My aunt

married a drummer also. I just sort of gravitated towards the drum set.

But actually, I started playing congas and hand percussion instruments

before I really became sort of professional in drums.

FJ: How did you come to play with Trane?

RASHIED

ALI: Actually, I was born and raised in Philadelphia and John Coltrane

lived in Philadelphia all of his young life. He moved from North Carolina

as a kid up to Philly. So actually, I first met John in Philadelphia back

in '59, '58, while he was still playing with Miles Davis, but I wasn't

considering myself as really good enough to play with John Coltrane in

those days. I admired the man so much and I would go hear him play when

he was working with Miles Davis and he lived about four blocks, five blocks

away from me and I used to go sit on his porch and listen to him practice

because Mrs. Alice Coltrane wouldn't let us go upstairs, that's his mom,

while he was practicing and stuff like that and so we would just sit outside

and listen to him and then we would leave. When I really got enough experience

to try and play with him, he was down in Philadelphia and I asked him

a couple of times if I could sit in with him, but he said, "Not right

now." He encouraged me to go to New York and stuff like that and

so I did. I came to New York and then I got a chance to sit and play with

him in New York and the rest is history. That is when I joined the band

in 1965.

FJ: Was it competitive between Rashied Ali and Elvin Jones?

RASHIED

ALI: Not at all, Fred. In those days, things were kind of different and

I was an upstart. I was just trying to get my rhythm off and so there

was a few misunderstandings between the old band and the new band. Elvin

was one of my heroes. He was one of the guys that really got me started

to play something different. By listening to Elvin Jones, I was able to

find Rashied Ali.

FJ: Many who document the music have cheapened the innovations of Coltrane's

lessening the impact or in some circumstances, ignoring the heavyweight's

later years entirely.

RASHIED

ALI: Yeah, that's a shame too, Fred, because that is a stepping stone

to what is going on right now. Well, actually, I wouldn't say it was ignored

that much. At the time, I would like to also think of myself as really

working with John and helping him create that sound. It was just that

John was really instrumental in that kind of music because even with his

former quartet with Elvin. They were playing very avant-garde kind of

music and the people dug it because he had this thing going with Miles

Davis and with his band. When he really, really decided that he wanted

to get out of chord changes and get out of time, rhythm, and meters, that

is when things started changing as far as the public is concerned. That

went on for a while, but it was actually embraced by a lot of musicians

while John was alive because when he was alive, I played with a lot of

people like Sonny Rollins and Grachan Moncur and Don Byas and they were

embracing the free kind of music, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor. That

stuff was really happening in the Sixties and when John left us here,

that is when the music made a change. Miles Davis went to Bitches Brew

and they got into a fusion thing and all kinds of different things happened

and it just sort of kind of dropped out of the public's eye, but not for

me because I stayed in the game and I'm still in it now, Fred. Right now,

I see the music is resurging again. It is starting to come up a little

bit more because I've been doing a lot of playing lately and it is not

that I don't play conventional jazz because I do enjoy playing it, but

I'd much rather play more experimental stuff than conventional stuff.

I think when John was here, the music was hanging in there, but a lot

of people were so used to him playing certain kind of things. I think

if he had stayed here, it would be the music hat we'd be playing today.

It is actually because I'm still here and the music right now, a lot of

youngsters are embracing this music and I've been doing pretty well with

it right now.

FJ: Did you continue to legacy with Alice?

RASHIED

ALI: For a little while. I played with Alice for about a year or so after,

maybe a couple of years after Coltrane passed. I did most of the stuff

with my own band. I had a lot of different bands in those times and not

only did I have different bands, I also had a club that I opened in New

York called Ali's Alley. That club lasted for about five or six years

and that way, I was able to play a lot with my band and different bands

that I put together and getting other avant-garde bands to play because

it was at a point in the early Seventies where there wasn't too many places

out here that an avant-garde band could play. So Ali's Alley was one of

those places. That went from 1973 to 1979. It was a great club and the

club got a lot of props. People from Europe, Japan, all over the world

came to hear the club and so Ali's Alley produced a lot of avant-garde

music in those days.

FJ: The music being documented on Survival Records.

RASHIED

ALI: Yes, it is. It exactly is.

FJ: So titles reissued on CD by Knit Media.

RASHIED

ALI: Yes.

FJ: A session with a practically unknown Frank Lowe.

RASHIED

ALI: Yes, and in fact, Fred, I just recorded something with Frank Lowe

earlier this year that I am going to put out. That is the second time

that we've recorded since the very first time I recorded with him as a

duo on Survival Records.

FJ: And James Blood Ulmer.

RASHIED

ALI: Oh, yeah, James Blood is another one. In fact, we've got a band now

we call the New York Art Quartet with James Blood, Reggie Workman, and