SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2020

VOLUME NINE NUMBER ONE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SULLIVAN FORTNER

Idris Muhammad

(1939-2014)

Artist Biography by Thom Jurek

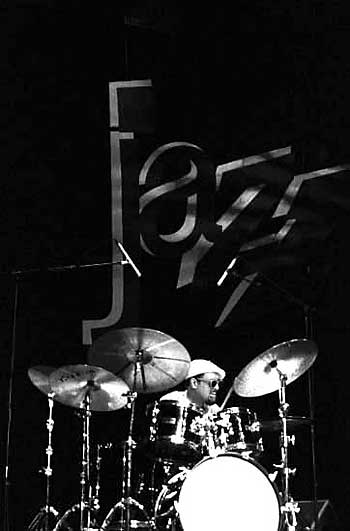

As one of contemporary music's most sampled drummers, New Orleans' Idris Muhammad's pioneering approach wed syncopated grooves, bluesy swing, and trademark funky breaks to NOLA's second line and parade rhythms. His resume includes nearly 500 recording credits that range across the genre spectrum. He began his professional career at 15 in 1954, playing on Art Neville and the Hawketts' "Mardi Gras Mambo," and at 17 backed Fats Domino on "Blueberry Hill." He spent the rest of his teens and early twenties working on the road with Sam Cooke and Curtis Mayfield & the Impressions. Muhammad toured and/or recorded with a who's-who of headline performers. He spent long tenures with Lou Donaldson, Pharoah Sanders, and Ahmad Jamal. He worked on important recordings and played tours with everyone from Roberta Flack, Grover Washington, Jr., and Bob James to Hank Crawford, Sonny Stitt, and Joe Lovano, just to name a few. His leader discography includes a number of influential, heavily sampled albums, including the mid-'70s triumvirate Power of Soul (universally regarded as a jazz-funk classic), House of the Rising Sun, and Turn This Mutha Out. During the '80s and '90s he worked as a touring sideman with John Hicks, Sanders, Nathan Davis, and Washington, Jr. His final leader date was for 2004's The Champs on Sunnyside, co-billed with organist Joey DeFrancesco and guitarist Ximo Tebar. He died in 2014.

Muhammad was born Leo Morris in New Orleans' 13th Ward. His four siblings were also drummers. Despite the influence of heredity, Muhammad claimed in his autobiography Inside the Music that the hissing, clanging, bumping rhythms from the machinery at Buddy's Cleaners and Pressing Shop next door to the family's home provided the inspiration -- and syncopation -- for his playing signature. Other than what he picked up from his siblings and Buddy's, Muhammad was completely self-taught. His family was friends with the Nevilles and that relationship helped in procuring his first real gig: At 15 he sat in with Art Neville and the Hawketts on "Mardi Gras Mambo." The youngster played with a slew of musicians in the neighborhood and hung around Cosimo Matassa's studio to watch artists such as Professor Longhair, Ernie K. Doe, and many more work their magic. At 17 he played on the Fats Domino recording session that netted "Blueberry Hill."

He toured with Sam Cooke at 18, before leaving to play behind Curtis Mayfield & the Impressions. In 1960, at age 21, he helmed the kit behind New Orleans R&B singer Joe Jones on the hit "You Talk Too Much." He worked with Coasters' guitarist Sonny Forriest & His Orchestra on Tuff Pickin' for Decca in 1966; that same year he converted to Islam and changed his name to Idris Muhammad (though labels he recorded for including Blue Note and Cadet continued to use his birth name in credits for some time). He won a traveling gig with saxophonist Lou Donaldson in 1966 and made his recording debut with him on Blowing in the Wind for Cadet in 1967. He remained with Donaldson's band until 1973. Among the many albums they cut together are Alligator Boogaloo, Mr. Shing-A-Ling, Midnight Creeper, and Everything I Play Is Funky.

In 1968, Muhammad met Galt MacDermot and won the drum slot in the house band for the original Broadway production of Hair, and subsequently played and recorded with MacDermot's studio bands. 1969 saw Muhammad's name(s) appear on a slew of significant recordings by Donald Byrd (Fancy Free), Paul Desmond (Summertime), George Benson (Tell It Like It Is, The Other Side of Abbey Road), Grant Green (Carryin' On), Charles Earland (Black Talk!), and Pharoah Sanders (Jewels of Thought).

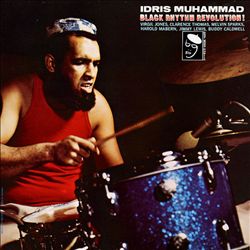

In 1970 Muhammad signed on as a house drummer for Prestige Records. He played on seminal recordings that year by Rusty Bryant and Gene Ammons and continued to work with Blue Note artists including Horace Silver. In 1971 Muhammad released his leader debut, Black Rhythm Revolution!, with a septet that included pianist Harold Mabern and Melvin Sparks. He followed it a few months later with Peace and Rhythm with Ron Carter on bass. During those two years, Muhammad's life was almost literally spent in the studio. He played on no less than three-dozen recordings including his own, and appeared on now-classic outings by Walter Bishop, Jr. (Coral Keys), Grover Washington, Jr. (Inner City Blues and Soul Box), Rusty Bryant (Fire Eater), and Bobbi Humphrey (Flute In).

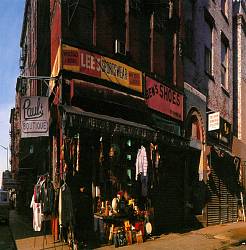

In 1973, Muhammad signed to Kudu and issued Power of Soul, his signature recording and an undisputed, oft-sampled jazz-funk classic. Comprised of four long pieces, its lineup included Bob James (who arranged the set), Randy Brecker, Ralph MacDonald, Joe Beck, and Washington, Jr. (The Beastie Boys' Paul's Boutique opens with a lengthy sample of "Loran’s Dance," Power of Soul's final track.) Inarguably a jazz outing, Muhammad claimed in an interview that he was a funk drummer, not a jazz drummer. That same year, he participated in the bicoastal sessions for Brazilian guitarist Luiz Bonfa's historic Jacaranda. Arranged by Deodato, it is inarguably one of the greatest fusion sides of the '70s. Some of the other participants in these sessions included Airto, Stanley Clarke, Ray Barretto, John Tropea, and Brecker.

Given the critical reception of the album, the drummer's studio commitments increased. He played on Roberta Flack's signature hit single "Killing Me Softly" and its accompanying album, and played on dates led by Nat Adderley, Stanley Turrentine, Morgana King, Eric Gale, Merry Clayton, and James. In 1975 he recorded House of the Rising Sun. Arranged by David Matthews and Tom Harrell, and produced by Creed Taylor, it offered a unique hearing of the drummer's musically integrated vision. A funked-up reading of the traditional title track led forays into the jazzy soul of Ashford & Simpson ("Hard to Face the Music,") an adaptation of Chopin's Prelude No. 4 ("Theme for New York City"), the Neville Brothers' NOLA funk ("Hey Pocky A-Way"), and Brazilian fusion in Ary Barroso (“Baia”). It also included the modal funk of the oft-sampled "Sudan," co-composed by Muhammad and Harrell. The session's lineup included saxophonists David Sanborn, Bob Berg, and Ronnie Cuber, with Harrell on trumpet, Will Lee on bass, and guitars by Eric Gale and Beck. The album peaked at 51 on the R&B charts.

Muhammad continued working with Flack. He played on Feel Like Makin' Love, and branched out to work with other R&B artists including Gene McDaniels and Dexter Wansel. In 1977, Muhammad released Turn This Mutha Out, a then-controversial jazz-funk and disco outing that has since become a staple among DJs, rappers, and producers. It placed in the Top 200 and spent 19 weeks on the charts. There was little time to tour as a leader; Muhammad was intensely busy alternating between recording and live roles with bandleaders Houston Person, David "Fathead" Newman, and Hilton Ruiz.

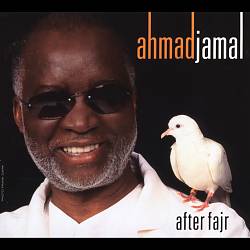

Muhammad's continued work with Jamal won him critical accolades on later albums, including After Fajr. He also played in Junior Mance's trio for the acclaimed Soul Eyes. In 2007, he joined young gun organist Wil Blades for Sketchy alongside guitarist Will Bernard. In 2008 Muhammad and bassist Cameron Brown joined trombonist Raul De Souza's studio band for Soul & Creation; the year also saw the release of his final appearance with Jamal on It's Magic. That year the drummer also became an actor; he played a prominent role in Leigh Richert's comedy My Brother's Keeper, and in 2012 appeared as himself in guerilla filmmaker Mike Redman’s provocative documentary on sampling culture, Sample: Not for Sale. Muhammad, who had been undergoing kidney dialysis for some time, passed away at home in New Orleans in July of 2014.

Idris Muhammad

Idris Muhammad

Idris Muhammad was born on November 13,1939, and began playing the drums

at age 8 in his native New Orleans. By the time he was 16, he was

performing in jazz bands. Muhammad became known as one of the most

innovative drummers in soul music of the 1960's, performing with singers

Sam Cooke, Jerry Butler, and The Impressions.He played for the popular musical Hair while performing with the house band for the Prestige Label in the early 1970's. For the rest of that decade, he accompanied popular singer Roberta Flack, led his own band, and worked with Johnny Griffin and Pharaoh Sanders.

An excellent drummer who has appeared in many types of settings, Idris Muhammad became a professional when he was 16. He played primarily soul and R&B during 1962-1964 and then spent 1965-1967 as a member of Lou Donaldson's band. He was the house drummer at Prestige Records (1970-1972), appearing on many albums as a sideman. Of his later jazz associations, Muhammad played with Johnny Griffin (1978-1979), Pharoah Sanders in the 1980s, George Coleman, and the Paris Reunion Band (1986-1988). He has recorded everything from post-bop to dance music as a leader for such labels as Prestige, Kudu, Fantasy, Theresa, and Lipstick.

Muhammad's 1993 recording My Turn includes saxophonist Grover Washington, Jr. and trumpetor Randy Brecker, both of whom are also featured performers in this year's 25th Annual University of Pittsburgh Jazz Seminar and Concert.

https://www.moderndrummer.com/2014/07/idris-muhammad-dies-age-74/

Idris Muhammad Dies at Age 74

The funk and jazz drummer Idris Muhammad, who hailed from New Orleans and spent his recent years playing with pianist Ahmad Jamal, passed away this week at age seventy-four. Muhammad’s friend Dan Williams, who’s worked with the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, confirmed the drummer’s death in a piece on NOLA.com, with few other details at press time.

Muhammad was born Leo Morris on November 13, 1939, and grew up in New Orleans’ 13th Ward. While still in his teens he played on Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill.” In the ’60s he converted to Islam and assumed his new name. “One guy told me that if I changed my name, I was going to have a problem because no one would know that Leo Morris and Idris Muhammad were the same guy,” the drummer told MD in an August 1991 Portraits piece. “But I thought, well, if I stay the same person, then people will know it’s me. And it worked like that. Everybody knew right away that it was me, because of my style of playing.”

In a May 1996 MD feature, Muhammad described the foundation of his style: “My rhythms are a mixture of the second-line street beats and the way the Indians who danced during Mardi Gras played the tambourine.” Idris’s solid time and funky feel lifted the work of countless artists in the worlds of soul, R&B, funk, pop, and jazz, including Sam Cooke, Curtis Mayfield, Gene Ammons, Lou Donaldson, Grant Green, Charles Earland, Pharoah Sanders, Betty Carter, Roberta Flack, and John Scofield. Muhammad also released many albums as a leader, beginning with 1970’s Black Rhythm Revolution! In MD in 1996 he called 1974’s Power of Soul his greatest record. “It’s only four tracks,” he said, “but the intensity of the rhythms I’m playing and how settled, and how swinging, and how hard it grooves is what makes it.”

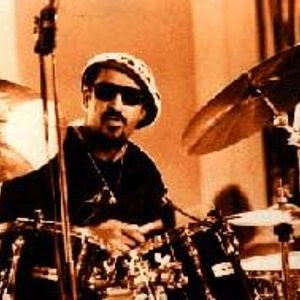

In that same 1996 feature, which came out shortly after Scofield’s Groove Elation album, which is beloved by fans in part for Muhammad’s funky playing, Ken Micallef asked Idris what went through his mind while on stage with Sco. “I’m thinking hard about the music,” Muhammad said. “I’m inside the music. Guys ask me why I wear dark glasses on the bandstand. It’s because I’m playing with my eyes closed. I don’t want to look at anybody; I don’t want to see anything. I go inside when I play.”

Watch for more coverage in the print edition of Modern Drummer.

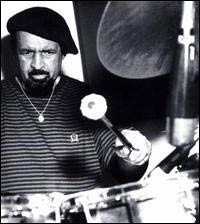

Photo by Rick Malkin

Idris Muhammad, Drummer Whose Beat Still Echoes, Dies at 74

Idris Muhammad, a drummer whose deep groove propelled both a broad career in jazz and an array of hits spanning rhythm and blues, funk and soul, died on July 29 in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. He was 74.

His death was confirmed by Dan Williams, a friend affiliated with the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation. The cause was not specified.

Mr. Muhammad was a proud product of New Orleans, whose strutting parade rhythms always lurked just beneath the surface of his style. A busy sideman as early as his teenage years, he later backed Curtis Mayfield, Sam Cooke, Roberta Flack and the jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, and as a key member of the house band laid the rhythmic foundation for the original Broadway production of “Hair.”

But the heart of his work was at the intersection of jazz, R&B and funk, especially as they converged in the 1970s. He made a string of albums now prized by connoisseurs of funk, including “Power of Soul” (1974), “House of the Rising Sun” (1976) and “Turn This Mutha Out” (1977) with a supporting cast including players like the trumpeter Randy Brecker and the keyboardist Bob James.

Mr. Muhammad’s in-the-pocket backbeat also bolstered crossover efforts by the guitarists Grant Green and George Benson and the saxophonists Lou Donaldson and Grover Washington Jr. Within the last 20 years he had worked more in an acoustic mode, most prominently with the pianist Ahmad Jamal. Among the others he worked with were the guitarist John Scofield and the saxophonist Joe Lovano, who once honored him with a tune titled “Idris.”

He was born Leo Morris on Nov. 13, 1939, in New Orleans. His father played banjo, and four of his siblings were drummers. Naturally drawn to the sound of Mardi Gras parade bands, he found his calling with no formal training. He was 15 when he played on Art Neville and the Hawketts’ enduring 1954 recording of “Mardi Gras Mambo,” and not much older when he appeared on Fats Domino’s hit version of “Blueberry Hill.”

In 1966 he married Delores Brooks, lead singer for the Crystals, a girl group with a string of pop hits, including “Da Doo Ron Ron.” The couple converted to Islam, changing their names to Idris and Sakinah Muhammad, and lived in London and Vienna before their marriage ended in divorce in 1999. They had two sons and two daughters; he also had a daughter from a previous marriage, to the former Gracie Lee Edwards.

Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Mr.

Muhammad was widely sampled by hip-hop artists, including Tupac Shakur,

the Notorious B.I.G., Eminem, Lupe Fiasco and Drake. The Beastie Boys

album “Paul’s Boutique” opens with a lengthy sample of “Loran’s Dance,”

from “The Power of Soul.” Asked in an interview how he felt about other

people using his music, he told Wax Poetics magazine, “It don’t really

belong to me, man,” adding: “The gift the Creator has given me, I can’t

be selfish with. If I keep it in my pocket, it’s not going to go

anyplace.”

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/idris-muhammad-new-orleans-jazz-drummer-who-played-teenager-fats-domino-s-hit-single-blueberry-hill-a382096.html

Idris Muhammad: New Orleans jazz drummer who played as a teenager on Fats Domino’s hit single 'Blueberry Hill'

by Brian Morton

Perhaps no single musician of recent times better captured the vivid variety and natural eclecticism of New Orleans music than drummer Idris Muhammad, who died back in the city of his birth after ill-health curtailed his seemingly unstoppable rate of production.

Muhammad’s list of performing credits covers r’n’b, funk, soul, but also what came to be known as “soul jazz” or later “acid jazz”, but he also dabbled in the avant-garde, notably with the fiery saxophonist Pharoah Sanders.

Muhammad had a natural gift for syncopation and a time-sense that allowed him to produce rhythms of almost mathematical rigour that could nonetheless slip in and out of metre as the music dictated. Like a great many drummers, he worked very largely under other leaders and the range of his associations is astonishing: with saxophonists Gene Ammons and Lou Donaldson, guitarists Ernest Ranglin and John Scofield, cornetist Nat Adderley, as well as crossover artists as varied as George Benson and Roberta Flack.

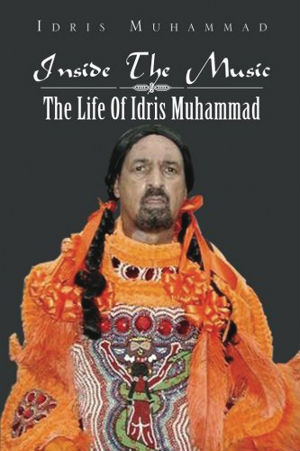

Muhammad told his own story in Inside the Music: The Life of Idris Muhammad (2012), co-written with his friend and associate Britt Alexander. It was, he told a British journalist, an attempt to “get all the scraps of memory together before it was all forgotten”.

Recent years had seen him apparently suffering from kidney problems that required dialysis. He had largely withdrawn from active playing, but his most important latter-day association was with the pianist Ahmad Jamal whose resurgent career was premised largely on a rejection of “jazz” terminology and a celebration of the continuity of African-American music.

Muhammad was born Leo Morris in New Orleans in 1939. Despite an interest in other instruments, he showed immediate and exceptional promise as a percussionist. “I wasn’t the kind of kid who went round hitting things all the time, but I just took to the drums like they were an extension of me.”

A professional career began when he was still in his teens and he can be heard as a 16-year-old on Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill”, an association he remained wryly proud of.

His first taste of national touring was with Sam Cooke, though he later worked with soul singer Jerry Butler and with Butler’s sometime collaborator Curtis Mayfield.

Until the mid-60s, he worked largely in r’n’b, but responded strongly to new agenda in black culture and found himself working more frequently in jazz and post-bop contexts.

In mid-decade, he converted to Islam and changed his name. After an early marriage failed, he married Dolores (LaLa) Brooks of The Crystals. The couple separated in 1999.

Working as house drummer for the Prestige label meant that Muhammad worked with a huge array of artists in the jazz/r’n’b orbit but he also aspired to record as leader and in 1970 and 1971 made the powerful Black Rhythm Revolution! and the more mystical Peace and Rhythm .

On these records, he attempted to synthesise the various rhythmic styles and traditions – African, martial, Latin, free – that went into the making of jazz and New Orleans music in general. On the latter recording, he explored a style of playing in which the drums, far from holding the ensemble to strict time, moved without restraint through and across the music. It was a discipline he was able to apply to many different musical contexts, and most recently to the highly successful trio with Jamal.

He enjoyed a particularly close relationship with producers and engineers, having a very clear idea of how the drums should sound in recorded music. Working for Prestige had put him in contact with Rudy van Gelder, who raised jazz recording several technical levels in a single generation, bringing out the strength and subtlety of the “rhythm section”.

In 1974 and 1976, working with luminary producer Creed Taylor, Muhammad made Power of Soul and House of the Rising Sun (for the CTI/Kudu label) a pair of recordings that once again explored the continuum of African-American music; the title track of the earlier record was a Jimi Hendrix composition, that of the second a definitive New Orleans song. (House of the Rising Sun also included a version of The Meters’ “Hey Pock-Away”.)

This was long before New Orleans roots traditions had been re-integrated with modern jazz and before the music’s centre of gravity had shifted back from New York (where Muhammad spent some obligatory mid-career time) to the Mississippi delta.

A later recording,Turn This Mutha Out, lacked the Taylor touch and was slight and light by comparison, but it gave Muhammad an underground hit with the David Matthews- and Tony Sarafino-written “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”, which has been regularly sampled ever since, most notably by Jamiroquai.

It was this younger generation of soul- and r’n’b-aware mainstream musicians that kept Muhammad’s name in wider circulation. He, meantime, continued to work in jazz with Jamal, Sanders and others until ill-health curtailed his activities and he returned to New Orleans in 2011. Following his death, Muhammad was buried according to Muslim tradition.

Idris Muhammad, jazz, r’n’b percussionist, born Leo Morris, New Orleans, Louisiana 13 November 1939 ; married twice (two sons, three daughters); died New Orleans, Louisiana 29 July 2014.

https://istanbulcymbals.com/artists/13/idris-muhammad.html

He changed his name in the 1960s upon his conversion to Islam. He is known for his funky playing style. He has released a number of albums as leader, and has played with a number of jazz legends including Lou Donaldson, Johnny Griffin, Pharoah Sanders and Grover Washington, Jr. He has been touring and recording with pianist Ahmad Jamal since 1995. At 15 years old, one of Muhammad's earliest recorded sessions as a drummer was on Fats Domino's 1956 hit "Blueberry Hill".

In 1966, he married Dolores "LaLa" Brooks (former member of the Crystals; she converted to Islam with him and went for a time under the name Sakinah Muhammad). They separated in 1999. Together, they have two sons and two daughters.

Idris Muhammad, Drummer Who Crossed Genre Lines, Dies at 74

For more than 50 years, a New Orleans fixture

Idris Muhammad, an all-purpose New Orleans-born

drummer whose career found him working both as leader and in-demand

collaborator, with artists falling into the jazz, funk and R&B

camps, died July 29, according to several news sources. The cause and

location of death were not reported, but Muhammad was known to have been

living in New Orleans since 2011, undergoing dialysis treatment.

Born Leo Morris on November 13, 1939, the musician changed his name in

the 1960s upon converting to Islam. By that time he had already logged

countless hours in New Orleans studios, beginning at age 16 when he

played on Fats Domino’s iconic R&B hit “Blueberry Hill.” He also

played with the Hawketts (including Art Neville) and toured with soul

music pioneer Sam Cooke during that period.

In 1966, he married Dolores “LaLa” Brooks of the rock and roll girl group the Crystals; they separated in 1999.

Muhammad’s long list of sideman credits includes work with such jazz

headliners as Pharoah Sanders, Lou Donaldson, Grover Washington Jr., Nat

Adderley, Gene Ammons, Grant Green, Freddie Hubbard, Ahmad Jamal,

Andrew Hill, Roberta Flack, John Scofield, Sonny Stitt, George Benson,

Randy Weston, Melvin Sparks, Joe Lovano and many others. In 1970,

Muhammad released his debut album as a leader, Black Rhythm Revolution!, on the Prestige label. He subsequently recorded more than a dozen albums under his own name.

Muhammad published his autobiography, Inside The Music: The Life of Idris Muhammad, in 2012.

https://www.drummerworld.com/drummers/Idris_Muhammad.html

DRUMMERWORLD

November 13, 1939 - July 29, 2014

| Idris Muhammad |

Idris Muhammad was born on November 13, 1939, and began playing the

drums at age 8 in his native New Orleans. By the time he was 16, he was

performing in jazz bands. Muhammad became known as one of the most

innovative drummers in soul music of the 1960's, performing with singers

Sam Cooke, Jerry Butler, and The Impressions. He played for the popular musical Hair while performing with the house band for the Prestige Label in the early 1970's. For the rest of that decade, he accompanied popular singer Roberta Flack, led his own band, and worked with Johnny Griffin and Pharaoh Sanders. An excellent drummer who has appeared in many types of settings, Idris Muhammad became a professional when he was 16. He played primarily soul and R&B during 1962-1964 and then spent 1965-1967 as a member of Lou Donaldson's band. He was the house drummer at Prestige Records (1970-1972), appearing on many albums as a sideman. Of his later jazz associations, Muhammad played with Johnny Griffin (1978-1979), Pharoah Sanders in the 1980s, George Coleman, and the Paris Reunion Band (1986-1988). He has recorded everything from post-bop to dance music as a leader for such labels as Prestige, Kudu, Fantasy, Theresa, and Lipstick. Muhammad's 1993 recording My Turn includes saxophonist Grover Washington, Jr. and trumpetor Randy Brecker, both of whom are also featured performers in this year's 25th Annual University of Pittsburgh Jazz Seminar and Concert. Idris Muhammad died at age 74 - July 29, 2014. His cause of death was not immediately known, but Muhammad had been receiving dialysis since retiring to his native New Orleans in 2011 |

© Timothy Orr

© Dimitri Ianni

© Timothy Orr

© Earl Perry

© John Ballon

© Sophie Leroux

©John Froehlich

Idris Muhammad - Joe Lovano

thanks for your visit!

Idris Muhammad: Coming to Grips with His Greatness

AllAboutJazz

"Style? No, I just play, man. I don't really have a style. Just being able to play music is a style, you know?" says the veteran drummer master Idris Muhammad in his laid-back and understated style.

This drummer may be under appreciated to those outside music—but not

those inside. Only in the last few years, however, has he actually

acknowledged his own greatness, finally ready to say that, yeah, he's

pretty damn good. "Because I'm getting older now and getting kind of

sentimental and saying, 'Did I really do that? Did I pass that much

time?'" he says with a laugh.

You see, Idris Muhammad is just a

flat-out nice guy. He'd rather just play than have people brag on him—a

lesson he learned from Paul Barbarin, a New Orleans drummer who played

with Louis Armstrong, King Oliver and Sidney Bechet. Barbarin told a

very young Leo Morris that the accolades would come one day, but to let

them roll off his back.

Idris is an agreeable fellow, all right.

Talkative, amusing, descriptive, but not demonstrative. Twice he was

awakened from a sound sleep by an inquiry into finding interview time

within his busy schedule. Rather than being irritated, he was cordial

and patient. The second time, rather than postpone, it was: "Let's do

it. Let's see what questions you want to ask, so I can answer them," and

off he went on an open and enlightening discussion of music and his

career. Idris Muhammad is not full of himself. And unlike many musicians

who feel the need to play right up until the end, Muhammad—an

immeasurably in-demand drummer—wants to step aside soon and "retire,"

satisfied that he has lived a good life; a life of his choosing; a life

that already has its share of accomplishments.

"I would like to

stop traveling and just go fishin' and smoke my Cuban cigars

[delightfully pronounced CIGì-gars in a New Orleans-tinted way] and

drink Diet Coke. I would like to enjoy a little bit of my life, come off

of the road. I've done a lot of great things in my lifetime. And I know

I can play. Some guys never reach their goal of what they're trying to

achieve in life, you know? My life has been quite fruitful," says

Muhammad. "I'm 62 now and I've been on the road 47 years and I'm

thinkin' that I don't really want die out here."

If he does go out, he's sure had a life that any musician would be proud of.

"I

grew up in New Orleans. I started out with the Neville Brothers. That's

my family. Arthur Neville had a band when I was 14 or 15 [the

Hawkettes]. They needed a drummer. All of my brothers are drummers. They

just happened to grab a hold of me because everybody else was workin.'

That was the launching of my career, playin' professionally," says

Muhammad.

Awake and not groggy, Idris Muhammad embarked on a discourse of his career with All About Jazz.

All About Jazz: Were you self-taught?

Idris Muhammad:

I had played in school bands. I used to listen a lot to different bands

play. My brothers was playin.' I couldn't play a lot and practice a lot

because I didn't have a set of drums. In my neighborhood, there was a

lot of schoolteachers and musicians. Uptown in New Orleans. It's

actually the 13th Ward. There were bands that used to march through the

streets. They would call it a "dry run." We had a lot of bars where we

lived. Nightclubs. A restaurant in the neighborhood. So it was that kind

of active place.

The guys in the neighborhood,

they used to just start playin' at one of the guy's houses. The next

thing you know, they'd come out in the streets and they would go from

bar to bar. And the people would follow them. I was a young kid, excited

about the music. I used to go and march with the band. I would dance

under the bass drum player. I was that small. This big drum kind of

attracted me because it was so loud—this big boom. I would go under the

bass drum and dance and the guy would say to me "move your ass away from

here before I hit you with this mallet." [laughter] Then I'd walk on

the side of him.

Due to that, that was the extension of the way I

play the drums. Because my drum playin' is from the bottom up. Most

drummers play the top part of the drums, down. But I pay the bottom, up.

Due to that, I got this rhythm, this bottom of the way I play that's so

different from everybody.

AAJ: That probably came in handy playin' rhythm and blues.

IM:

Yeah. That was the basis of our music was rhythm and blues at that

time. I was never a jazz drummer. I really don't think today that I'm a

jazz drummer. They kind of made me do this. And I ended up making so

many records with everybody that they started saying I was a jazz

drummer, you know? But I started off playin' rhythm and blues with

Arthur when we had the band. We used to back up all of the artists that

would come to New Orleans. Big Joe Turner. Muddy Waters. We was the band

that backed them up. So we always knew the top 10 tunes that was on the

charts at that time.

That's what I played. I have a style that I

made up due to the marching band in the street. We had two Indian

tribes in the neighborhood. Donald Harrison's father was the chief of

our neighborhood. Then we had Uncle Charlie, he was the chief of a

couple blocks down. I used to follow the Indians. They'd sing these

songs and play these tambourines. So the rhythms of the tambourine, I

combined them. I took that rhythm and the rhythm from the second line

and that's what I played.

AAJ: You knew at a young age music was going to be your life?

IM:

Yeah. I got hooked one Mardi Gras day. I think I was about 9. Some

Dixieland guys came by to get a drummer. My mother and I and my brother

were going out to the Mardi Gras. They said they needed a drummer. This

old guy asked my mother could I play on the back of this truck with

these old Dixieland musicians. And she said, "he's 9 years old and he's

going to enjoy the Mardi Gras." Some how or another, he convinced my

mother to let me go with them.

They had a big bass drum and one

snare drum and a symbol. They built up some beer cases for a seat for me

and I played with these old guys, man. And these guys were saying,

"This kid can play." After about six hours of touring through the

streets of New Orleans, they started passing out money and he gave me

two $5 bills. And I asked him, do we get paid to do this? And he said

yes. And I think that was it for me. That was the end of shinin' shoes

and trimmin' rose bushes and cleanin' swimmin' pools. I used to do that

to make a little extra money to go to the movies, you know? But that was

it for me. I started right away, when my brother wasn't home, to

practice the drums. I thought it out as a way of makin' money to get the

things that I wanted to get without bothering my dad, you know? It led

from one thing to another. Then Arthur needed a drummer. I was 15 and

they recorded a song called "Mardi Gras Mambo" which is the theme of the

Mardi Gras today.

We worked and worked and worked and worked,

next thing you know I was on the road with Arthur and a band. We were on

the road in '57, that was the launching of my road career.

AAJ: You played those early years with people like Fats Domino and Sam Cooke.

IM:

Yeah, I did some things with Fats. And I was Sam Cooke's personal

drummer. I was workin' for a guy named Joe Jones. He had a record out

called "You Talk Too Much." It was a big record at the time. The record

had gotten kind of cold. I was going to a nice restaurant in New Orleans

to get a sandwich with Joe Jones, and I'm waiting for my sandwich and

Joe goes in the dining room and sees Sam. Sam is complaining about the

drummer with the Upsetters band. He was on tour in New Orleans that

night. Joe said, "Look, my drummer plays anything." So he came and he

got me to sit at the dining table with Sam. Sam said "Do you know any of

my music?" I said, "yeah." He started singin' and I started playin' on

the table and he hired me.

AAJ: Did you have other influences on the drums during this time?

IM:

There were guys around New Orleans. I didn't know too much about

drummer outside New Orleans. There were so many great drummers in New

Orleans. Earl Palmer was there. Ed Blackwell was there. John Boudreaux

and Smokey Johnson. We used to rehearse in my house, but they were more

advanced than I was. We used to go and watch all of these guys play.

That was my influence until I started practicing with John Boudreau and

Smokey Johnson. They knew how to play like Max Roach and Art Blakey.

They would come to my house. They would play Art Blakey and Max Roach.

And I would say "I never heard of these guys? Who is this guy?" And they

brought these records. And I would say, "Aw, I can't do that, man. I'll

stay with what I do. I can't do that." And that was my first

introduction hearing Art Blakey and Max Roach.

AAJ: All that diversity in your playin' comes from New Orleans.

IM:

Yeah, because it's such a musical place. I didn't really know that

until I went to New York how much music I heard in New Orleans and how

versatile the drummers were. We were taught to read through the school

system, because you couldn't play the drums if you didn't know how to

read the parts. We were playin' all these waltzes, "The Blue Danube

Waltz," and overtures, "Stars and Stripes," and you had to read these

drum parts. The professor made you, one at a time, read these parts, or

else you got out of the band.

So we were kind of versatile in

playin' the drums. New Orleans is so thick with rhythms, because I guess

the many mixtures of people—the French and the Indians and the

Africans, all different varieties that the French put in the colony. It

made a nice gumbo. That's what I used to say. So I learned a lot of

music. I could play, but I didn't really know I could play. They were

sayin' to me I could play. But I never thought of myself as being that

good because there was so many great drummers around and my brothers

were drummers. They kept sayin' I was that good, but I didn't believe

'em.

I had one teacher in my life that I paid for one lesson.

His name was Paul Barbarin. He used to play with Louis Armstrong. All of

the seasoned guys used to say if you want to learn how to play drums,

you got to take lessons with Paul Barbarin. So I asked Mr. Barbarin to

come to my house so I could take a lesson. He came by. He said "Ok, sit

down at the drums and play the intro to 'Bourbon Street Parade.'" He

said play a waltz, and I played a waltz. He said play a mambo, and I

played a mambo. He said play a cha-cha, and I played a cha-cha. He said,

"Listen, son. I'm a very busy man. One day you're gonna be a great

drummer, but when they say to you that you're great, let in go in one

ear and out the other ear. Now gimme my two dollars."

And that

was it, man. [laughter] That was the first and last and only paid lesson

I ever had in my life. And I took that knowledge with me until about

seven years ago that I had to acknowledge that I was with Max Roach and

Art Blakely and Elvin [Jones], that they had said to me that I was in

their class. Art gave me a set of symbols 37 years ago when he heard me

play and they told me that I was great and I was something special. So

just recently I started speaking about it, that I do have something

special about my playin.'

AAJ: How did you make it to New York?

IM:

My first trip to New York was with Sam Cooke. That was just an eye

opener. We were workin' from the south, all the way up. We played the

Apollo Theater and then we went on. I came back to New Orleans. There

was some kind of mix-up with Sam and the guitarist that played with Sam,

and another drummer named June Gardner, from New Orleans. The guitarist

wanted an older guy to play with him. But Sam hired me, so he couldn't

do anything about it. So, he called June Gardner and offered him the

gig. June took the gig, and told me I could have his gig in town. So I

took his gig in town and he went out on the road with Sam.

The

next time I saw Sam, I was Jerry Butler's musical director, me and

Curtis Mayfield. He asked me why I quit, and I told him I never quit. He

fired me. He said he would have NEVER fire me. Then we found out the

guitarist pulled a fast one. So I was already with Jerry, and Curtis

Mayfield was the guitarist. So I stood with Jerry. We were workin' at

the Apollo Theater, workin' all the theaters. Then Curtis put the

Impressions back together and he made me an offer I couldn't refuse, so I

went with Curtis. At this particular time I was living in Chicago. So I

was recording a lot of music in Chicago with Curtis. I decided that

Chicago's weather in the wintertime was very, very cold. So I decided

after about three and a half years I was gonna move to New York.

So

I moved to New York. I was workin' at the Apollo Theater. I had quite a

bit of money because Curtis gave me a point and a half of Curtom

Publishing. I didn't really know what that was at that time, but it was a

lot of money. I came to New York and went to see a show that was there

and the musical director, who knew me, asked me what I was doing in

town. I said I'm living here. In the next couple of days I got a call

from him. Charlie Persip was the drummer. He fired Charlie Persip and

gave me the job. That was my first beginning of workin' a steady job in

New York City.

Because I could play all of that music. All of

the acts that was on the road, everybody knew me. A lot of guys, at that

time, didn't know how to play the funk that I play. So it was a new

thing in New York City. I was the only guy to play that type of funk. So

I would have guys coming by and watching me play. They would say, "What

is this?" I tell you, man, I had no idea I was starting a trend, that I

was playin' a style of drums that the guys who play the drums today

learned how to play from. I had no idea. They was tellin' me this, but I

was stickin' to what Mr. Barbarin said. All I was doin' was workin,'

you know? I was married and had a kid and I was trying to take care of

my family. It wasn't that I wanted to be famous or something like that.

AAJ: Is that where you started hearing more jazz, in New York?

IM:

Well, yeah. I was listening to jazz because when I finished work at the

Apollo Theater, the guys would say "Max Roach is playin' over there,"

and I would go to the club and see him play. Then I'd go down to

Birdland and see who was playin' there, you know, Miles Davis and

Coltrane, Cannonball, all of these groups. I'd go there just to hear

something else.

AAJ: Philly Joe?

IM:

Oh man! Philly was my buddy. I would go hear Philly Joe and all of

these cats play, man. Gee whiz. It was a long time before I would get

the nerve to go up to them and say to them I played the drums. I'd just

be hanging around, listenin' at what they were sayin.' I was too young

to have a drink in Birdland. They had a space in the club they called

the Peanut Gallery. That's where all the young people used to go and

have a Coca Cola and listen to the music.

As I got older, I

would go out and hear guys playin.' One time I went from the Apollo

Theater down to the Five Spot to hear this guy that all the members in

the band was talkin' about that played three horns at one time. I

thought they was crazy. I thought it was impossible. How could you play

three horns at one time? You only have one mouth, you know? I went down

and it was Rahsaan Roland Kirk. It was amazin' to hear this guy do this.

So I asked the drummer, could I play one tune with him. It was like a

magnet drawing me to him. So he asked me where I was from. His name was

Candy Finch. And he let me play. And after the melody, Roland Kirk

turned around and said, "Who's that on them drums?" And I said I was Leo

Morris. And he said, "Keep that beat! Keep that beat!" And the next

thing you know I end up playin' the whole set.

And then this guy

came to me and said, "man, you sound great. I'd like you to play a

concert with me at Town Hall." I said I was workin' at the Apollo. He

said, "Oh, man. If you can work it in, I want you to play this concert."

So I said, "OK, what's your name?" He said Kenny Dorham. I said, "Oh

man, I can't do this." He said, "Yeah, you can do it." So I had a couple

rehearsals with him and played the concert at Town Hall. It was Kenny

Dorham's band, Freddie Hubbard's band and Lee Morgan's band, in one

night. Kenny Dorham's band played first, then all the guys were saying

"Who is this drummer?" They said, "It's this guy from New Orleans."

That's how the jazz guys got a hold of me.

I never played jazz

before. Never of that caliber. I met Betty Carter there and George

Coleman and McCoy Tyner, all of these guys I met at this one gig. The

next thing you know, jazz guys started calling me. I was in Betty

Carter's band with George Coleman and John Hicks and Paul Chambers. Then

I was making records for Blue Note with Lou Donaldson and all of these

Alligator boogaloo and all these organ records I was makin.' Guys were

callin' me to do these records. They never gave me any music. A few

times with Horace Silver, he gave me some music and played it. And he

said, "No, that don't sound right. Throw that page away and play

something." They would play a song and I would just make up a rhythm to

it. If I was a smart dude at that time, I could be rich today

[laughter], by just writing out those parts and making them pay for it.

But I was a guy who was just very friendly and kind. And kind guys, a

lot of times, they take advantage of you.

But I made a lot of

records with organ. The organ trend came on the scene and I was makin'

all these records with Charles Earland and Dr. Lonnie Smith. We have a

great history of all of these records that we have out. Now they call it

Acid Jazz. But that was the beginning of something that was a trend

that was happening. And during this period, a lot of drummers in town

was just listenin' at what I was doin' and copying what I was doin.' So

it was like a new trend. I had no idea that this was happening, until

"Hair." I'm the original drummer from the musical "Hair."

We

were on Broadway four years and a half on that play. And the drum

rhythms from "Hair" belongs to me. It's mine. I created it. A guy gave

me 43 pages of chord changes, with just titles on it. And I made up all

these rhythms. I played the show for about a year and a half and I got

really sick. And they had to send in a sub, and there was no music. So

the play was in an uproar for about five days until I got well and came

back. They had me get the drum book written. A drummer friend of mine

who was good at that, Warren Smith, he wrote the drum book for "Hair."

Then I would have different drummers coming by to hear me play "Hair."

Bernard Purdie, Alphonse Mouzon, Billy Cobham, all of these guys were

coming by checking out what I was doing with the drums, so they could be

a sub. But they couldn't play the show. But they took pieces of me with

them from that. They took pieces of rhythm. Because it was a new trend

that was happenin.' So they developed what they heard, the way they

wanted it. But it all came from me.

I was recording a lot.

Playin' the music in "Hair." You know, "Hair" had many plays going on

around the country, and overseas. So I would go to Chicago and show the

drummer how to play, go to Los Angeles, show the drummer how to play.

I'd go around at every "Hair" opening to show guys how to play the show.

That opened up a whole new avenue for me, being on Broadway. So my

exposure in New York City was—today they say, "You da man, you da man."

[laughter]

But I still didn't know this. At that time I had four

kids. So my whole thing was trying to take care of these kids. I bought

a house in New Jersey. So I was busy trying to work and take care of

responsibilities. Not trying to be so famous. I would hear people say

things, and it was nice to hear and nice to have nice write-ups and

things like that. Still today, I like to hear nice words when I talk to

people and they write about me. Because I'm getting older now and

getting kind of sentimental and saying kind of, "Did I really do that?

Did I pass that much time?"

I remember when we recorded with

Roberta Flack. She asked me to join her band. And I said I'm with

"Hair." And she said, "Whenever you quit 'Hair' I want you in my band."

After a while I decided to quit "Hair" and as soon as I did I went with

Roberta Flack. We had Eric Gale, Ralph MacDonald, Richard Tee, Chuck

Rainey and myself. We were recording all of these records.

AAJ: You must have recorded hundreds of records.

IM:

There's a studio called Rudy Van Gelder's in New Jersey. One guy in Las

Vegas was doing a story on his life and he called me for some comment.

Rudy and I were good friends. As a matter of fact, it was Rudy who

opened up my drum sound, so you could hear it on the radio and knew it

was me. Rudy's studio was like a pyramid inside.

So this guy was

asking me about Rudy and I told him and he said, "I have all of the

records that you recorded at Rudy Van Gelder's. If you like I can send

you a catalog of everything you ever recorded." He sent it to me and

much to my surprise there was like 136 albums that I did at Rudy's

alone.

AAJ: Over the years in jazz, you've played with so many guys.

IM:

Many guys. Many guys. I haven't clocked the other stuff that I did.

There are other studios in New York, you know, and Chicago.

I

would like to stop traveling and just go fishin' and smoke my Cuban

cigars and drink Diet Coke. I would like to enjoy a little bit of my

life, come off of the road and not die here on the road. I'm playin' a

lot. I've done a lot of great things in my lifetime. And I know I can

play. Some guys never reach their goal of what they're trying to achieve

in life, you know? My life has been quite fruitful. There's not many

things that I'd like to do that I still haven't done. Now, since my kids

are all grown up and they're livin' a good life and everybody's happy,

I'd like to just try to enjoy a little life, by livin' in a warm

climate, fishin' and smoking Cuban cigars.

I'll play, but I

won't travel as much as I do today. Travelin' today is kind of hectic

with the [September 11] crisis and being in the airport. It's good. I

like it, and I like to be safe. But I'm 62 now and I've traveled for 47

years, I've been on the road 47 years and I'm thinkin' that I don't

really want die out here.

AAJ: When you stop, you'll still do studio work?

IM:

I wanna play when I wanna play because I wanna play. Not because I

gotta pay a mortgage, you know what I mean? Not because I gotta pay the

rent and the light bill and all like that. I wanna do what I wanna do. A

lot of us, we don't get a chance to do that. And when we do, we're too

damn old. We live a little while and the next thing you know, we're

dead. Because the system's got it set up like that. You can't retire

until 65, and at 65, man, you might be crippled or some shit. [laughter]

So I'm trying to do it now. I like to play, man. I like to make

people happy. But I just came off a tour with Joe Lovano in Europe. I

just was out in California with the Newport Jazz things, then Joe and I

left there and went straight to Europe. So for the whole month we were

on the road, man. We was playin' music, movin' from one country to the

other. It's good and it's great, you know? But I think I got somethin'

nicer to do in my life these days [laughter]. It's just that I think I'd

like to do something else. I don't wanna be uptight for some money. If

I'm gonna do it, it's because I wanna do it, not because I need the

money to do it.

A lot of us don't get this chance and they love

the music so much that they do it until they say "He used to play better

than that." I don't wanna do that, man. If it gets to that point, I'm

goin' fishin.' If I can't make you happy with this job, then I'm not

gonna do it. It's my outlook of how I wanna play this music. I've had a

wonderful career and I wanna keep it like that. I want to leave you with

how good it was and how much fun we had and leave it like that.

AAJ: No regrets?

IM:

Yeah. I had a good life, man. And I'm healthy. That's the other part of

it. I survived through a lot of stuff, man, and I'm still healthy. And I

still can play. My kids is sayin' to me, "Pop, you ought to go to

Florida, go back to New Orleans, go someplace." I gotta check it out. I

was thinking of going to St. Lucia. But these days I don't wanna be no

place ... I lived eight years in England and nine years in Austria,

because I took my kids abroad to be educated. Now they're grown up. I

lived in Europe a lot. These days in crisis, I don't wanna be outside of

the country no more. I don't wanna have to be some place and then have

to get back to the States. I think I'll just stay in the States

somewhere, get me a warm climate and go fishin,' man.

I just wanna enjoy life a little bit and have good vibes and good spirits around me.

Photo Credit: Dr. Jazz

http://jazzbluesnews.com/2018/11/12/idris-muhammad-became-known-as-one-of-the-most-innovative-drummers-in-soul-music-of-the-1960s-video/

JazzBluesNews

Idris Muhammad became known as one of the most innovative drummers in soul music of the 1960’s: Video

13.11. – Happy Birthday !!! Idris Muhammad was born on 1939, and began playing the drums at age 8 in his native New Orleans. By the time he was 16, he was performing in jazz bands.

Muhammad became known as one of the most innovative drummers in soul music of the 1960’s, performing with singers Sam Cooke, Jerry Butler, and The Impressions.

He played for the popular musical Hair while performing with the house band for the Prestige Label in the early 1970’s. For the rest of that decade, he accompanied popular singer Roberta Flack, led his own band, and worked with Johnny Griffin and Pharaoh Sanders.

An excellent drummer who has appeared in many types of settings, Idris Muhammad became a professional when he was 16. He played primarily soul and R&B during 1962-1964 and then spent 1965-1967 as a member of Lou Donaldson’s band. He was the house drummer at Prestige Records (1970-1972), appearing on many albums as a sideman. Of his later jazz associations, Muhammad played with Johnny Griffin (1978-1979), Pharoah Sanders in the 1980s, George Coleman, and the Paris Reunion Band (1986-1988). He has recorded everything from post-bop to dance music as a leader for such labels as Prestige, Kudu, Fantasy, Theresa, and Lipstick.

Muhammad’s 1993 recording My Turn includes saxophonist Grover Washington, Jr. and trumpetor Randy Brecker, both of whom are also featured performers in this year’s 25th Annual University of Pittsburgh Jazz Seminar and Concert.

Idris Muhammad died at age 74 – July 29, 2014. His cause of death was not immediately known, but Muhammad had been receiving dialysis since retiring to his native New Orleans in 2011.

Idris Muhammad, a drummer whose deep groove propelled both a broad career in jazz and an array of hits spanning rhythm and blues, funk and soul, died on July 29 in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. He was 74.

His death was confirmed by Dan Williams, a friend affiliated with the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation. The cause was not specified.

Mr. Muhammad was a proud product of New Orleans, whose strutting parade rhythms always lurked just beneath the surface of his style. A busy sideman as early as his teenage years, he later backed Curtis Mayfield, Sam Cooke, Roberta Flack and the jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, and as a key member of the house band laid the rhythmic foundation for the original Broadway production of “Hair.”

But the heart of his work was at the intersection of jazz, R&B and funk, especially as they converged in the 1970s. He made a string of albums now prized by connoisseurs of funk, including “Power of Soul” (1974), “House of the Rising Sun” (1976) and “Turn This Mutha Out” (1977) with a supporting cast including players like the trumpeter Randy Brecker and the keyboardist Bob James.

Mr. Muhammad’s in-the-pocket backbeat also bolstered crossover efforts by the guitarists Grant Green and George Benson and the saxophonists Lou Donaldson and Grover Washington Jr. Within the last 20 years he had worked more in an acoustic mode, most prominently with the pianist Ahmad Jamal. Among the others he worked with were the guitarist John Scofield and the saxophonist Joe Lovano, who once honored him with a tune titled “Idris.”

He was born Leo Morris on Nov. 13, 1939, in New Orleans. His father played banjo, and four of his siblings were drummers. Naturally drawn to the sound of Mardi Gras parade bands, he found his calling with no formal training. He was 15 when he played on Art Neville and the Hawketts’ enduring 1954 recording of “Mardi Gras Mambo,” and not much older when he appeared on Fats Domino’s hit version of “Blueberry Hill.”

In 1966 he married Delores Brooks, lead singer for the Crystals, a girl group with a string of pop hits, including “Da Doo Ron Ron.” The couple converted to Islam, changing their names to Idris and Sakinah Muhammad, and lived in London and Vienna before their marriage ended in divorce in 1999. They had two sons and two daughters; he also had a daughter from a previous marriage, to the former Gracie Lee Edwards.

Mr. Muhammad was widely sampled by hip-hop artists, including Tupac Shakur, the Notorious B.I.G., Eminem, Lupe Fiasco and Drake. The Beastie Boys album “Paul’s Boutique” opens with a lengthy sample of “Loran’s Dance,” from “The Power of Soul.” Asked in an interview how he felt about other people using his music, he told Wax Poetics magazine, “It don’t really belong to me, man,” adding: “The gift the Creator has given me, I can’t be selfish with. If I keep it in my pocket, it’s not going to go anyplace.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idris_Muhammad

Idris Muhammad

Idris Muhammad (Arabic: إدريس محمد; born Leo Morris; November 13, 1939 – July 29, 2014) was an American jazz drummer who recorded with Ahmad Jamal, Lou Donaldson, Pharoah Sanders, and Tete Montoliu.[2]

Biography

Born Leo Morris in New Orleans, he grew up in the city's 13th Ward.[3] He showed early talent as a percussionist and began his professional career while still a teenager, playing on Fats Domino’s "Blueberry Hill".[4]

He toured with Sam Cooke, and later worked with Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield, mostly working in R&B until the mid-1960s, before going on to work more frequently in jazz.[citation needed]

Muhammad was an endorser of Istanbul Agop Cymbals.[5]

He died of kidney failure, aged 74, in 2014.[6][7]

Personal life

He changed his name to Idris Muhammad in the 1960s upon his conversion to Islam. Speaking of his name change, he later noted in an interview with Modern Drummer magazine, "One guy told me that if I changed my name, I was going to have a problem because no one would know that Leo Morris and Idris Muhammad were the same guy...But I thought, well, if I stay the same person, then people will know it’s me. And it worked like that. Everybody knew right away that it was me, because of my style of playing.”[3]

In 1966, he married Dolores "LaLa" Brooks, a former member of the Crystals. She converted to Islam with him and went for a time by the name Sakinah Muhammad. They separated in 1999. Together, they had two sons and two daughters, and he had one daughter from a previous marriage to Gracie Lee Edwards.[6]

Discography

Idris Muhammad is probably best known for his 1974 album Power of Soul, including the track "Loran's Dance", which received considerable airplay on jazz radio stations.[citation needed]

As leader

- 1970: Black Rhythm Revolution! (Prestige)

- 1971: Peace and Rhythm (Prestige)

- 1974: Power of Soul (Kudu)

- 1976: House of the Rising Sun (Kudu)

- 1977: Turn This Mutha Out (Kudu)

- 1978: Boogie to the Top (Kudu)

- 1978: You Ain't No Friend of Mine (Fantasy)

- 1979: Foxhuntin' (Fantasy)

- 1980: Make It Count (Fantasy)

- 1980: Kabsha (Theresa)

- 1992: My Turn (Lipstick)

- 1998: Right Now (Cannonball)

As sideman

With Nat Adderley

- Calling Out Loud (CTI, 1968)

With Eric Alexander

- Solid! (Milestone, 1998)

With Gene Ammons

- The Black Cat! (Prestige, 1970)

- You Talk That Talk! (Prestige, 1971)

- My Way (Prestige, 1971)

- Got My Own (Prestige, 1972)

- Big Bad Jug (Prestige, 1972)

With George Benson

- Goodies (Verve, 1968)

- Tell It Like It Is (A&M, 1969)

- The Other Side of Abbey Road (A&M, 1969)

With Walter Bishop, Jr.

- Bish Bash (Xanadu, 1968 [1975])

- Coral Keys (Black Jazz, 1971)

With Bobby Broom

- Modern Man (Delmark, 2001)

With Rusty Bryant

- Soul Liberation (Prestige, 1970)

- Fire Eater (Prestige, 1971)

- Wild Fire (Prestige, 1971)

With George Coleman

- Manhattan Panorama (Theresa, 1985)

With Hank Crawford

- Help Me Make it Through the Night (Kudu, 1972)

- Wildflower (Kudu, 1973)

- I Hear a Symphony (Kudu, 1975)

- Tight (Milestone, 1996)

With Paul Desmond

- Summertime (A&M/CTI, 1968)

With Fats Domino

With Lou Donaldson

- Fried Buzzard (Cadet, 1965)

- Blowing in the Wind (Cadet, 1966)

- Lou Donaldson At His Best (Cadet, 1966)

- Alligator Bogaloo (Blue Note, 1967)

- Mr. Shing-A-Ling (Blue Note, 1967)

- Midnight Creeper (Blue Note, 1968)

- Say It Loud! (Blue Note, 1968)

- Hot Dog (Blue Note, 1969)

- Everything I Play is Funky (Blue Note, 1970)

- Pretty Things (Blue Note, 1970)

- The Scorpion (Blue Note, 1970)

- Cosmos (Blue Note, 1971)

- Sweet Poppa Lou (Muse, 1981)

With Charles Earland

- Black Talk! (Prestige, 1969)

With Grant Green

- Carryin' On (Blue Note, 1969)

- Green Is Beautiful (Blue Note, 1970)

- Alive! (Blue Note, 1970)

- Live at Club Mozambique (Blue Note 2006, recorded 1971)

With Johnny Griffin

- NYC Underground (Galaxy, 1979 [1981])

- To the Ladies (Galaxy, 1979 [1982])

With Roy Hargrove

- Habana (Verve, 1997)

With Benjamin Herman

- Get In (1999)

With John Hicks

- Some Other Time (Theresa, 1981)

- In Concert (Theresa, 1984 [1986])

- Inc. 1 (DIW, 1985)

- I'll Give You Something to Remember Me By (Limetree, 1987)

- Is That So? (Timeless, 1991)

With Andrew Hill

- Grass Roots (Blue Note, 1968)

- Shippin' Out (Muse, 1978)

With Freddie Hubbard

- New Colors (Hip Bop Essence, 2001)

With Bobbi Humphrey

- Flute In (Blue Note, 1971)

With Willis Jackson

- Bar Wars (Muse, 1977)

With Ahmad Jamal

- The Essence Part One (Birdology, 1995)

- Big Byrd: The Essence Part 2 (Birdology, 1995)

- Nature: The Essence Part Three (Birdology, 1997)

- Picture Perfect (Birdology, 2000)

- Ahmad Jamal 70th Birthday/Olympia 2000 (Dreyfus, 2000)

- In Search of Momentum (Dreyfus, 2002)

- After Fajr (Dreyfus, 2005)

- It's Magic (Dreyfus, 2008)

With Bob James

- Touchdown (Tappan Zee, 1978)

With J. J. Johnson and Kai Winding

- Betwixt & Between (A&M/CTI, 1969)

With Etta Jones

- My Mother's Eyes (Muse, 1977)

- If You Could See Me Now (Muse, 1978)

With Rodney Jones

- Soul Manifesto (1991)

With Keystone Trio

- Heart Beats (1995)[9]

- Newklear Music (1997)[10]

With Charles Kynard

- Wa-Tu-Wa-Zui (Beautiful People) (Prestige, 1970)

With Joe Lovano

- Friendly Fire (Blue Note, 1998)

- Flights of Fancy: Trio Fascination Edition Two (Blue Note, 2000)

With Johnny Lytle

- Fast Hands (Muse, 1980)

- Good Vibes (Muse, 1982)

With Harold Mabern

- Workin' & Wailin' (Prestige, 1969)

- Greasy Kid Stuff! (Prestige, 1970)

With Jimmy McGriff

- City Lights (JAM, 1981)

With Tete Montoliu

- Catalonian Rhapsody (Alfa, 1992)

With Tisziji Munoz

- Visiting This Planet (Anami Music

- Hearing Voices (Anami Music)

- Concrete Jungle (Prestige, 1978)

- Keep the Dream Alive (Prestige, 1978)

With Don Patterson

- Why Not... (Muse, 1978)

With Houston Person

- Person to Person! (Prestige, 1970)

- The Real Thing (Eastbound, 1973)

- Wild Flower (Muse, 1977)

With Ernest Ranglin

- Below the Bassline (Island, 1998)

With Roots

- Stablemates (In+Out, 1993)

With Pharoah Sanders

- Jewels of Thought (Impulse!, 1969)

- Journey to the One (Theresa, 1980)

- Pharoah Sanders Live... (Theresa, 1982)

- Heart is a Melody (Theresa, 1982)

- Shukuru (Theresa, 1985)

- Africa (Timeless, 1987)

With John Scofield

- Groove Elation (Blue Note, 1995)

With Shirley Scott

- Lean on Me (Cadet, 1972)

With Lonnie Smith

- Turning Point (Blue Note, 1969)

With Melvin Sparks

- Sparks! (Prestige, 1970)

- Spark Plug (Prestige, 1971)

- Akilah! (Prestige, 1972)

With Leon Spencer

- Sneak Preview! (Prestige, 1970)

- Louisiana Slim (Prestige, 1971)

- Bad Walking Woman (Prestige, 1972)

- Where I'm Coming From (Prestige, 1972)

With Bob Stewart

- First Line (JMT, 1988)

With Sonny Stitt

- Turn It On! (Prestige, 1971)

- Black Vibrations (Prestige, 1971)

- Goin' Down Slow (Prestige, 1972)

With Gábor Szabó

- Macho (Salvation, 1975)

With Stanley Turrentine

- Common Touch (Blue Note, 1968)

- The Man with the Sad Face (Fantasy, 1976)

With Randy Weston

- Portraits of Duke Ellington (Verve, 1989)

- Portraits of Thelonious Monk (Verve, 1989)

- Self Portraits (Verve, 1989)

- Spirits of Our Ancestors (Verve, 1991)

With Reuben Wilson

- Love Bug (Blue Note, 1969)

With Roberto Magris

- Mating Call (JMood, 2010)

Sampled

- Beastie Boys, Paul's Boutique, "To All the Girls" (Capitol, 1989)[11]

References

External links

- Interview in Allaboutjazz

- Artist and album page of Lipstick Records

- https://www.nola.com/entertainment_life/music/article_893d49c4-312c-5c94-a32a-13237e2c947d.html

- Idris Muhammad at AllMusic

- "Idris Muhammad Dies at Age 74". Modern Drummer Magazine. 2014-07-31. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Morton, Brian (August 8, 2014). "Idris Muhammad: New Orleans jazz drummer who played as a teenager on Fats Domino's hit single 'Blueberry Hill'". The Independent.

- "Istanbul Agop 22" Signature Idris Muhammad Ride Cymbal", Memphis Drum Shop.

- Chinen, Nate (August 8, 2014). "Idris Muhammad, Drummer Whose Beat Still Echoes, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- Morton, Brian (August 8, 2014). "Idris Muhammad: New Orleans jazz drummer who played as a teenager on Fats Domino's hit single 'Blueberry Hill'4". The Independent. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Fats Domino. "Blueberry Hill". Discogs page, revealing actual date to be 1965. Retrieved January 11, 2018., .

- Allmusic Heart Beats review

- Allmusic Newklear Music review

https://www.offbeat.com/articles/inside-music-the-life-idris-muhammad-idris-muhammad-xlibris/

Inside the Music: The Life of Idris Muhammad, Idris Muhammad

Book Review

In the heyday of New Orleans rhythm and blues, it was rare that sidemen on a recording session were credited. Yet jazz aficionados are aware that it was Idris Muhammad behind the drums on an array of superb albums from the likes of pianists Ahmad Jamal and Randy Weston, saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Lou Donaldson and others.

In the ’60s, and against the advice of some business people, Leo Morris changed his name to Idris Muhammad when he became a Muslim. In his autobiography, the drummer takes the reader on his journey from a nine-year-old Morris playing on the back of a truck in a Mardi Gras parade to his adult career performing on stages and in studios around the world. No matter how far he traveled, however, his hometown of New Orleans remained in the pulse of his drumbeat.

Muhammad is undoubtedly the only drummer whose technique on the hi-hat cymbals has been inspired by the sound of a steam presser. His family lived at 1220 Lyons Street next door to Buddy’s Cleaners and Pressing Shop. “I hear this: Cracka-chew…pssst taugh… over and over again,” he writes. “Practicing the drums next to Buddy’s Cleaners, I started copying this rhythm…”

This book is full of wonderful insights into Muhammad’s distinctive style that made him a much in-demand musician. The reason he wraps his drumsticks in tape like a tennis player’s racket is because he had to switch to metal sticks after breaking his arm falling off of some monkey bars. The sticks made his hands black so he wrapped them. He continued the practice throughout his career and later chose red tape—his signature color.

To this day, Muhammad, who at 73 has retired in his hometown, declares, “I’m a funk player. I’m not a jazz musician.” The drummer, who also led and recorded his own jazz/funk groups, tells the story of the great bandleader and drummer Art Blakey putting him in a bear hug and saying, “You’re one of us [jazz musicians] and I’ll squeeze you until you say you’re one of us.”

Considering all the local references and Muhammad’s look back to New Orleans as it was in the late ‘40s and ‘50s, readers, and particularly New Orleanians, don’t necessarily have to be music buffs to enjoy this book. Part of the joy is that it is all in Muhammad’s voice without filler or interpretation. He’s telling the story in his own words, his own jargon that, like his music, speaks of New Orleans.

Architect of the Backbeat:

Remembering Idris Muhammad, Funk Drumming Legend

Howard Denner/Getty Images

The birth of American popular music can be traced to the emergence of the backbeat, the alternating boom and crack created when the swing rhythms of jazz migrated from the cymbals down to the bass and snare drums. The backbeat is the unifying feature of all African-influenced American pop music styles. It’s the backbeat that made early rock and roll so irresistible to Eisenhower era kids and akin to “savage jungle beat music” in the eyes and ears of their Ward and June Cleaver parental units. It’s the beat that underpinned early R&B, which, when combined with jazz and New Orleans marching band elements, became the funk music of the 1960s and ’70s. By the ’80s, DJs and producers were chipping funk out of its vinyl amber to be reconstructed with repurposed home audio equipment to live again as the pastiche DNA of hip-hop.

The beat lives on. Rap is a hegemony. Rock is, perhaps, ailing, but still here. And the various forms of EDM are really just aural mutations of those backbeat rhythms shot out through waveform filters and replayed with computer precision and machine implacability. The beat lives, but the drummer’s moment is over. There’s a musician’s joke that goes like this: How many drummers does it take to screw in a lightbulb? None. They have machines that do that now.

Despite the vitality of the backbeat itself, the time when the drummer would’ve been recognized for giving music its spine is gone. If it ever really existed. James Brown might be the godfather of funk, but his drummer Clyde Stubblefield did as much to create the sound of the genre as anyone. Just like any other industry, dudes who do work for hire don’t get to own the product. “The Big Beat” by Billy Squier is one of the most sampled drum breaks of all time, used by Jay Z, Alicia Keys, Run-D.M.C., and many more. That’s well known and often remarked upon. Yet it’s Bobby Chouinard’s drumming that forms the basis for those samples, not Squier’s pants-too-tight vocal screech.

Idris Muhammad, who died July 29 at the age of 74, is one of those forgotten architects of the backbeat. Most likely, you’ve heard his work without even realizing it in songs by Drake, Beastie Boys, Fatboy Slim, Eminem, Nas, LL Cool J, the Notorious B.I.G., Kool G Rap, 2Pac, and many others. He was among the first drummers — perhaps the very first — to bring funk beats to jazz and played an important part in the development of funk drumming. Which makes him, by extension, a building block in the edifice of hip-hop and modern music.

A native of New Orleans, Muhammad, whose family was originally from Nigeria, was steeped in the city’s rich music traditions. In an interesting inversion of his later role as a hip-hop sample cornerstone, one of his earliest influences was the machine stomp and hiss sound of the steam presses at the dry cleaner next to his childhood home, a sound he says informed his signature hi-hat technique.

In New Orleans, then as now, if you could play, your name got around. He sat in with his neighborhood friends, Arthur and Aaron Neville, whose band the Hawkettes would eventually become the Meters. He backed Fats Domino after Fats’s sax player Clarence Ford heard him around town. He was introduced to Sam Cooke in a restaurant and auditioned for his band by banging out the beats to Cooke’s songs on a tabletop while Cooke sang, a voice and a beat foreshadowing the ad hoc cyphers of the rap age.

It was Cooke who brought Muhammad to New York for the first time, and after short stints back in New Orleans and Chicago, Muhammad moved to New York City in the mid-1960s. “When I got there, I had no gig,” Muhammad said in an interview with Eothen Alapatt in Wax Poetics. “So I went to the Apollo Theater. I met with Reuben Phillips, the Apollo’s bandleader, and let him know I was in town. He fired the drummer in the Apollo band and hired me! So I was in the band for about a year and a half.”

The Apollo led to Muhammad’s introduction to the New York jazz scene, most notably sax player Lou Donaldson. Donaldson, who started his career as a sideman in more or less straight-ahead jazz settings, had begun experimenting with more bluesy beat-heavy styles in the early 1960s. Muhammad joined Donaldson’s band in 1967 and recorded a string of influential albums on the Blue Note label that in many ways mirrored the stylistic innovations that Brown (with Stubblefield) was creating with his solo work, only in an instrumental idiom.

Those records, starting with 1967’s Alligator Bogaloo, are a trove of hip-hop samples. “Ode to Billie Joe” off 1967’s Mr. Shing-a-Ling would later provide the marching funk shuffle of Kanye’s “Jesus Walks” and Eminem’s “Bad Guy.” 1970’s Pretty Things produced the swinging groove “Pot Belly,” later to be sampled by Dr. Dre on “Rat-Tat-Tat-Tat” off 1992’s seminal gangster rap touchstone The Chronic and by RZA for “Give It to Ya Raw,” the B side to Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s 1995 single “Brooklyn Zoo.” Donaldson and Muhammad’s 1969 cover of the Isley Brothers’ “It’s Your Thing” off 1969’s Hot Dog provided the New Orleans–inflected bounce for songs by De La Soul, Brand Nubian, and, semi-strangely, Madonna in her third-wave post-Sex Maverick Records iteration on “I’d Rather Be Your Lover” off 1995’s Bedtime Stories. The hypnotic rhodes and drum groove of “Loran’s Dance” off Muhammad’s 1974 solo album, The Power of Soul, would become the Dust Brothers–produced “To All the Girls,” the lead track off Beastie Boys’ legendary Paul’s Boutique. To name just a few.

Speaking to Alapatt in Wax Poetics, Muhammad would say of the sample-bred immortality of his work, “It don’t really belong to me, man; I’m only the creator. If you take something I create, and you do something with it, then someone else will take it and move it to another stage. And this is what happened with hip-hop. This is in my aura. I’m doing stuff for people to put out there so people can grab it.”

Idris Muhammad’s death was noted in many drummer-centric websites and was deeply felt in New Orleans. “I’d put him on the Mount Rushmore of New Orleans drummers,” said radio host and Tulane professor George Ingmire. It took a few days for the news to appear on other news sites, and it took until August 8 for an obituary to appear in the New York Times. Even in death, Idris Muhammad is overlooked.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Jason Concepcion is a staff writer for Grantland and coauthor of We’ll Always Have Linsanity.

https://www.musicismysanctuary.com/tribute-idris-muhammad-1939-2014

Drummer Idris Muhammad was truly a musical giant. If many other legends have excelled or innovated, it usually involved a particular genre of music. Not many can be found to have explored so many styles of Jazz let alone Soul, Funk, R-n-B, Rock and various New-Orleans styles to their repertoire.

Many great drummers have been at the forefront of their ensembles and although Muhammad’s own group discography is impressive with a dozen releases from 1971 onwards, it’s his work as a sideman that truly helps propel him into musical royalty. With Idris, it was more than names, it was also breadth. He started as early as the 50s recording with Fats Domino and touring with Sam Cooke and went on to play with experimental jazz greats Pharoah Sanders (1969 to 1987) and Ahmad Jahmal (1995-2008). Basically the man featured on 136 albums recorded in Rudy Van Gelder’s legendary New Jersey recording studio alone. Finally this interview in a Youssou N’Dour documentary showcases his often cited infectious personality and is a testament to his international stature.

What I personally like the most about his playing is that not only was it stellar, but it seemed to always be featured on the most creative and fascinating projects from otherwise more traditional musicians. He added a doseof funkiness to Alive! by Blue Note guitarist Grant Green and grooved hard on Nat Adderley’s genre bending Calling Out Loud album. Whether by Andrew Hill or Rueben Wilson it seems Idris was trusted as understanding the voyage the musicians wanted to embark on, but also helped them reach their destination by propelling them to a higher ground off the strengths of his drum-kit.

His label moves are also telling. His time at Blue Note led to him participating in many classic records, but his rawest ones are with saxophonist Lou Donaldson. After recording on the more open minded Cadet label with Lou, they paved the way for a string of Jazz-Funk releases on Blue Note that have provided samples and Idris breaks for an entire decade of Hip-Hop production. He recorded with Donaldson until 1970, before going solo and releasing his literally revolutionary album Black Rhythm Revolution on Prestige. But I personally cherish his time on CTI/Kudu the most. The quality of arrangements, artistic freedom and funkier approach of the label seemed tailor-made for Muhamad to shine and did he ever! Bob James’ Nautilus pretty much sums up all of my descriptions so far in one incredible piece of music.

For me the Idris Muhamad experience is encapsulated in two records and ironically Power of Soul was one of my first finds and I just found Turn This Mutha Out a month ago. It also helps define the fine line between Soul-Jazz and Jazz-Funk and you can basically do so by simply looking at Muhammad’s face on both covers. Power of Soul is a lush contemplative effort where the soul-jazz drumming infuses energy into the subtle Fender Rhodes work as heard in the heavily sampled Loran’s Dance and my personal favorite Peace of Mind. On the other hand Idris “turns it out” on his jazz-funk opus that is edging closer to disco sounds to come, yet there is deep meaning to the rambunctious songs as the unfortunately aptly titled “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” indicates.