SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2020

VOLUME NINE NUMBER ONE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SULLIVAN FORTNER

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/frank-morgan-mn0000173007/biography

Frank Morgan

(1933-2007)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/frank-morgan-frank-morgan-by-brandt-reiter.php

Frank Morgan

A young acolyte of Charlie Parker, the Minneapolis-born alto

saxophonist Frank Morgan saw his first leader's disc, the eponymous Frank Morgan

(GNP), released in 1955; three decades would pass until he cut his

second. Much of the time in between—20 years, by his own estimation—was

spent in prison, on various drug-related charges (unfortunately Morgan

had absorbed not only Bird's musical language but his heroin-fueled

lifestyle as well). Last paroled in 1985, Morgan returned to the scene

with that year's acclaimed Easy Living (Contemporary) kicking

off one of jazz' most remarkable comebacks. He has recorded and toured

with a vengeance ever since. Even a serious stroke in 1996 could only

keep the resurgent alto master off the bandstand for a mere two months.

His latest disc, City Nights (HighNote), recorded live last

fall at NYC's Jazz Standard with pianist George Cables, bassist Curtis

Lundy and drummer Billy Hart, is due out early this month.

Soft-spoken and exceedingly gracious, Morgan, now 70, talked with us last month by phone from his Taos, New Mexico home.

All About Jazz:

Before we get to the new disc, let's talk about your journey up to this

point. Your father was a guitarist with the Ink Spots...

Frank Morgan:

Yes. But he really wanted to be a jazz guitarist. He used to play

changes for all the cats in the hotel room, he used to play by my crib.

He said when I started to reach for the guitar that's when he started to

feel he was communicating with me. He wanted me to be a guitarist; I

started on it at two. But at seven, as part of my continuing music

education, I went over from Milwaukee where I was living to spend Easter

vacation with my father who was on the road in Detroit, and he took me

to hear the Jay McShann Band. And when Charlie Parker stood up to take

his first solo on "Hootie Blues," my father said I turned to him and

said "Listen, dad, that's it for the guitar." And he took me backstage

and introduced me to Bird.

FM: Yeah, at seven. And Bird made arrangements to meet us at the music store the next day to pick out what I thought was an alto saxophone. But Bird made me start on clarinet.

AAJ: For your fingering?

FM: For the embouchure. It's a great thing for you if you aspire to play the saxophone. Because you have to get in touch with your face muscles just to stop the clarinet from squeaking. I didn't like it at the time because I wanted to play what I heard, but I certainly appreciate it now.

AAJ: When did you pick up the alto?

FM: I was on clarinet for maybe a year and a half or two before I got an alto. In fact, I got a soprano before an alto. The soprano is a gorgeous instrument, but I don't play it anymore. It interferes with my alto. The alto feels cumbersome when I put the soprano down. And I can't have that.

AAJ: Did you start formal study around that time?

FM: Yes, there were two or three teachers around Milwaukee that I studied with, but mainly with a great saxophonist in Milwaukee—Leonard Gay. And then I moved to California at 14, and my father contacted Benny Carter for me. He didn't take students, but he recommended me to Merle Johnston, who taught formal saxophone. He had taught Jimmy Dorsey, a lot of great players. I studied with him, while still working with my father on guitar. We played great duos together, just working on the changes. And he helped me work on the solos, everything.

AAJ: And did you get the chance to study with Parker?

FM: We had contact every time he came to Los Angeles, which was quite often. I would spend almost all the time with him that he was in town. He loved to play sessions, you know? We had some great sessions in some of the movie stars' homes. Bird was like a superstar, then. Like the Beatles. Hollywood catered to him.

AAJ: You led your first disc out there [in L.A.] at 21?

FM: Yes, in 1954. It actually wasn't really my album to start out with. I was on an all-star date with Wild Bill Davis and Conte Candoli, and then I did another date with Wardell Gray, Conte Candoli, Carl Perkins, Larance Marable, Leroy Vinegar. And they put the two of them together and made me the leader, which was cool. (laughs) And so it became my first album.

AAJ: Parker had just passed away, and there was a lot of talk about you being the new Bird. That's a lot of weight to put on a young man's shoulders.

FM: Too much. It scared me to death; I self-destructed. Every time they tried to send me to New York I'd go back to prison. It became my pattern to play as soon as I got out of jail, and then I would start using right away, and then I would stop playing, I was so afraid of New York, and being judged, I guess I was willing to do almost anything to keep it from happening, you know? Finally I just had to say, well, shit, I'm 52, 54 years old, I'm scheduled to open at the Village Vanguard [in 1986]. Leonard Feather had told me just before he passed, "You don't have to be afraid of anything, man. Just show up and do what you do, and the world will open up to you." And Billy Higgins, who was right there in New York with me, told me, "Keep appearing, and not disappearing." Billy was holding my hand, guiding me. And Cedar [Walton] and Johnny Coles and Buster [Williams]. We were recording live [ Bebop Lives! , Contemporary], and I didn't have time to rehearse for the record. I'd be doing interviews up until the time I was due at the club. But it was thrilling. Like a fairytale. It was my first time ever seeing New York. My first night in the Vanguard, I was two hours early. I just walked around and absorbed the energy, like all those people were speaking to me.

FM: Well, that was my only source of income. Thank God they were letting me record, so I could put some money in my pocket. And putting the records out made the personal appearances come pretty quickly.

AAJ: You cut 14 discs between '85 and '96, a host of which are exceptionally good.

FM: Well, one thing runs down the center of it all. All the time, I played with the best musicians that I could get. All the time, I just kind of rode on their backs. They were showing me the way all the time, and it's been a beautiful journey.

AAJ:City Nights is a wonderful record.

FM: I haven't really heard it. I don't like to listen to my own recordings. It's always a lot of second guessing: 'I should have did this,' 'Oh, I didn't do that,' 'I played this wrong.' I am who I am—I mean, I know I'm imperfect and I'm playing imperfect music—but still, it affects me.

AAJ: "Georgia" is a surprise.

FM: I had just seen a magazine where they were saying Ray Charles was dying. It had a picture of him on the cover, and he looked horrible. So I had Ray Charles on my mind that night.

AAJ: And that's an instance where you'd get the idea on the bandstand and just start playing it, and the rhythm section would just fall in?

FM: Yeah. They give me that latitude. They know that that's the way that I like to do it. And, you know, it works. Not all the time, but, well, nothing works all the time. (laughs)

AAJ: You lead off "Summertime," but it's really given over to George [Cables].

FM: I just wanted to melodize a little, and then let him be heard. George—he's not well, you know—he's on dialysis. But he's still playing gorgeously.

AAJ: Curtis and Billy sound terrific, as usual.

FM: Yes, they're all musician's musicians. Curtis is such a beautiful cat. I love the way he plays—I feel so secure with him behind me. And Billy told me after the last gig we played, "I'm willing to go along with you just as long as you want to keep it up, Frank. I'm turning down other gigs because I really love playing with you." That made me cry.

FM: You know, for years I wasn't a big fan of Monk. I was resisting the whole thing, and I regret that. I was looking for the technique, and form, that shit, and this cat is just primitive. But it's beautiful. And to play his tunes, and give them your own interpretation, yet try to capture him...I'm still just kind of learning "'Round Midnight." I don't think I'll ever get it right.

AAJ: You're very hard on yourself.

FM: Well, I'm such a young old man, and I'm trying to correct a lot of shit as best I can. It's a humongous task. I mean, I missed the whole ballgame on Monk! For years!

AAJ: What I'm hearing new on the record is more attention to space.

FM: Yes, exactly. You got it. I'm just coming to understand better that silence is our friend, not our enemy. Silence is our best friend. It gives what you play after it more meaning.

AAJ: It's rare to see someone of your age and experience so determined to continue evolving.

FM: Oh, well, I'm just a baby, you know. And if I ever have any doubts about that, all I have to do is go listen to Charles McPherson. Or Sonny Fortune, Kenny Garrett, Donald Harrison, James Spaulding. There's so many beautiful alto players out there—you've just got to stay on top of your shit.

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/19/arts/19morgan.html

Frank Morgan, Master of Bebop Sax, Dies at 73

by

Frank Morgan, a jazz saxophonist whose promising career was derailed by drug problems in the 1950s but whose triumphant comeback 30 years later led to an unexpected taste of midlife stardom, died on Friday in Minneapolis. He was 73.

The cause was colon cancer, said his agent, Reggie Marshall. He had battled other health problems in recent years, including a stroke and kidney failure.

Mr. Morgan was heralded as one of the rising stars of the Los Angeles jazz scene when he was barely out of his teens. He worked with Lionel Hampton and recorded with the drummer Kenny Clarke and others. But it would take him decades to achieve the fame many predicted for him, primarily for reasons that had nothing to do with music.

He had taken up the alto saxophone at a young age after hearing Charlie Parker, a master of that instrument and one of the architects of bebop. So all-consuming was his admiration for Parker that he emulated not just the musical approach for which Parker was celebrated but also the heroin habit for which he was notorious.

Mr. Morgan suffered a stroke in 1998, but he was back on the road and in the studio within a few months and resumed recording, for the HighNote label, in 2004. After living in New Mexico for many years, he moved back to Minneapolis in 2005 and reduced his workload, although he continued to perform occasionally. He had just returned from a European tour when he learned he had cancer last month.

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=17354786

Obituaries

Remembering Jazz Saxophonist Frank Morgan

December 18, 2007

Heard on Fresh Air

Listen

Bebop sax player Frank Morgan told Terry Gross in 1987 that "in prison, the instrument was the thing that kept me sane — the chance to play it with hope." Ezy Blackbear

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/17354786/17354784" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

https://www.npr.org/2011/07/01/15126693/frank-morgan-on-piano-jazz

Frank Morgan On Piano Jazz

Frank Morgan on the cover of City Nights.

Set List

- "Blue Monk" (Monk)

- "In A Sentimental Mood" (Ellington)

- "I'll Remember April" (DePaul, Johnston, Raye)

- "Billie's Bounce" (C. Parker)

- "Embraceable You" (G. Gershwin, I. Gershwin)

- "Goodbye" (G. Jenkins)

Alto saxophonist Frank Morgan brings his sweet and soulful tone to a quartet setting with host Marian McPartland, bassist Gary Mazzaroppi and drummer Glenn Davis on this episode of Piano Jazz. A protégé of Charlie Parker, Morgan took a long detour into drugs and prison. Here, he adds a page to the more cheerful second chapter in his story. His alto honks, flutters, flies and cries in tunes including "Blue Monk," "Billie's Bounce" and the ballads "In a Sentimental Mood" and "Goodbye."

Frank Morgan was born in Minneapolis in 1933. His family moved to Milwaukee when he was 6 and to Los Angeles when he was 14. His father, a guitarist for the band The Ink Spots, began teaching him guitar when he was just 2 years old.

When Morgan was 7, he traveled to Detroit to spend some time with his father, who was playing a gig there. The elder Morgan took his son to the Paradise Theater, where the stage show included Jay McShann's band. Morgan recalls that his life changed the moment he heard Charlie Parker take a solo during "Hootie's Blues."

Morgan's dad took his son backstage to meet Parker. It was Parker who suggested that the child learn and master the clarinet before moving on to the alto sax. Parker later became a regular at the club opened in L.A. by the elder Morgan in 1947, Casablanca, and continued his interest in Frank Morgan's musical development. Parker was only one of the many bebop players that frequented the club, with Hollywood stars such as Ava Gardner, Gregory Peck and Ginger Rogers often in the house to hear this cutting-edge music.

Morgan recalls Casablanca as the place where he learned that drug use was "socially acceptable" — this in spite of Charlie Parker's efforts to shield him from the seamier side of the musician's life. To Parker's profound disappointment, Frank Morgan saw heroin as part of what it took to "play like Charlie Parker." Morgan began using the drug when he was 17.

Having won a TV talent contest at 15, Morgan eventually began playing with Lionel Hampton's band. Before his recording debut as a leader in 1955, he had played as a sideman with Kenny Clarke, Teddy Charles and Ray Charles. The album, Introducing Frank Morgan, received critical acclaim. However, heroin addiction and prison time were soon to rob Morgan of his time in the spotlight. Although he continued to play in prison, it was not until 1985 that he was once again able to take control of his life and music.

Morgan made his second album, Easy Living, that year and began his career again. He has continued to record, tour and reach out to those in prison and those fighting addiction. Along the way, he received critical accolades and attention from the mainstream media, including a prime-time interview with Jane Pauley. Despite suffering a stroke in 1998, Morgan made a full recovery and returned to an active career of performing and recording.

Frank Morgan died on Dec. 14, 2007, at age 73.

Originally broadcast Oct. 5, 2004. Originally recorded Feb. 16, 2004.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/frankmorgan

Frank Morgan

Frank Morgan

It is a real rarity for a jazz musician to have his career interrupted for three decades and then be able to make a complete comeback. Frank Morgan showed a great deal of promise in his early days, but it was a long time before he could fulfill his potential. The son of guitarist Stanley Morgan (who played with the Ink Spots), he took up clarinet and alto early on. Morgan moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and was approached by Duke Ellington who wanted the then 15-year-old Frank to go on the road with his band. Frank's father wanted his son to finish school so the Ellington gig never materialized, but by the time he was 17, Frank was working at LA's Club Alabam, backing the likes of Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday. Morgan worked on the bop scene of early-'50s Los Angeles, recording with Teddy Charles (1953) and Kenny Clarke (1954), and under his own name for GNP in 1955.

Unfortunately, around that same time Frank followed his idol and mentor Charlie “Bird” Parker into heroin addiction, and spent most of the next thirty years serving time for thefts to support his habit. Yet except for periods in the Los Angeles County jail system, he never strayed too far from music. At most penal institutions, there were bands made up of inmates, and Morgan was greeted as a celebrity. He was constantly made gifts of mouthpieces, drugs, food, cigarettes. “The greatest big band I ever played with was in San Quentin. Art Pepper and I were proud of that band. We had Jimmy Bunn and Frank Butler, and some other musicians who were known and some who weren't, but they could play. We played every Saturday night for what they called a Warden's Tour, which showed paying visitors only the cleanest cell blocks and exercise yards. But people would take that tour just to hear the band.”

When he was not incarcerated Frank performed occasionally around LA, but it was not until 1985 that Morgan, with the help of artist and future wife Rosalinda Kolb, managed to leave his life of “questionable interests” behind him and once again concentrate on his music. Resuming his recording career after a thirty-year hiatus, Frank was rediscovered and his unique history, combined with his equally unique sound and story-telling ability on his horn, made him a media star. He made multiple appearances on the Today Show in the '80s and '90s; starred in “Prison-Made Tuxedos,” an off-Broadway play about his life, in 1987; was the first subject of Jane Pauley's “Real Life” primetime TV show on NBC in 1990; and won the Downbeat Critics Poll for Best Alto Saxophonist in 1991.

In 1998 a new chapter was added to Frank's inspiring life story when he suffered a stroke while enroute to the Flint Jazz Festival in Michigan. Although doctors initially predicted he would never play again, Frank was gigging within six months. After a series of critically-acclaimed pre-stroke recordings for Contemporary, Antilles, and Telarc, in 2003 Frank signed a new recording agreement with New York-based HighNote Records, and today many fans and Jazz writers alike say he has never sounded better.

Frank Morgan's initial recordings for his new label, “City Nights” (HighNote HCD 7129) and “Raising the Standard” (HighNote HCD 7143), have received great reviews and significant airplay both here and abroad. Both albums were recorded live at New York's Jazz Standard on a series of triumphant evenings which heralded the reappearance of a vibrant and important voice in Jazz.

https://www.wnyc.org/story/frank-morgan/

Meet Frank Morgan: Jazzman, Conman, Charlie Parker's Successor

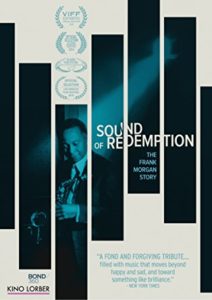

Frank Morgan was a gifted alto sax player and Charlie Parker's protégé. He was also a heroin addict and conman who spent 30 years of his life in and out of prison, most of it at San Quentin, where he performed in a big band with fellow junkie jazz musicians. Executive producer Michael Connelly tells Morgan's story in "The Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story." He will be joined by saxophonist Grace Kelly, who is featured in the documentary.

The film premieres Wednesday December 2nd at the IFC Center, 323 Sixth Avenue.

EVENT: The 7:40 P.M. show on opening night (Dec. 2nd) includes a Q&A with special guests: Michael Connelly, director NC Heikin, musicians Grace Kelly, George Cables and Mark Gross. It will be moderated by NYC jazz critic Gary Giddins.

AUDIO: <iframe frameborder="0" scrolling="no" height="130" width="100%" src="https://www.wnyc.org/widgets/ondemand_player/wnyc/#file=/audio/json/555775/&share=1"></iframe>

Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story (official trailer)

https://www.palmspringslife.com/saxophonist-great-frank-morgan-finds-redemption-in-documentary/

Saxophonist Great Frank Morgan Finds Redemption in Documentary

Film shows late musician's talents against backdrop of drug abuse and jail time

Palm Springs Life

That advice came back to help the teacher as a producer for the documentary, Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story, which makes its world premiere June 14 at the Los Angeles Film Festival.

“Our hero has enough flaws for several characters,” Egan says. “I had

to follow my own advice and see how important those flaws were to how

interesting the story is. If he had been normal and successful, it

wouldn’t have been a documentary; it would have been a tribute.”

The film profiles Morgan, a gifted saxophone player who became a protégée of Charlie Parker in the early 1950’s and whose talents attracted an offer from Duke Ellington to tour when he was just a teen. But all that talent couldn’t stop Morgan from falling prey to the lure of heroin, which led to jail stints over a 30-year period.

Most of his jail time was spent at San Quentin, which comes back to anchor the film to reveal how Morgan formed a big band in the prison called The San Quentin All Stars featuring other jazz greats who were serving time. Director NC Heikin brings the viewer back to San Quentin to witness a tribute concert to Morgan.

Egan hopes to bring the film to the Palm Springs International Film Festival in January. It wouldn’t be the first time. Egan produced Angels in the Dust, which showed at PSIFF in 2008, and Wild About Harry, which won “Best of the Fest” in 2009.

His collaboration with Heikin on the Morgan piece came from their partnership in 2009 on Kimjongilia, a documentary that unearthed children captive at North Korea prisoner camps. The film won the 2010 One World Best Human Rights Documentary Film Award from the Human Rights & Democracy Network.

Egan took a few minutes to chat with Palm Springs Life.

What made you commit to making this documentary about Frank Morgan?

“Author Michael Connelly (The Lincoln Lawyer, Blood Work) gave

us money for the North Korea documentary, and he asked to meet NC and

myself in LA. He pitched to us this story about Frank Morgan. I was

like, ‘I don’t know’. It’s a tough story. Frank got into a lot of

trouble. He stole people’s saxophones and hocked them. Michael says this

is a story about redemption. So we started this journey and he helped

finance the beginning of it.”

How much did you know about the West Coast jazz scene?

“I realized I had a lot to learn. I felt I had discovered things about

the West Coast that I had no idea existed at all. We interviewed Clora

Bryant, the first female jazz musician (trumpet player). Dizzy Gillespie

hired her. She was asked to take care of Frank when he came to LA. Here

we are in her tiny apartment, it was breathtaking, so much jazz history

all over the walls, and behind her stove you see a photo of Duke

Ellington with her. I had no idea who she was until this film started.”

Frank Morgan died in 2007. Was it difficult to make the film without him?

“The fortunate thing is that his wife/girlfriend Rosalinda Kolb had

done all of these recordings of him, interviewed him so we had all of

this great oral history. Then Steve Isoardi, a great jazz critic, also

interviewed Frank and that was part of the UCLA Library, and I didn’t

know that existed. And NBC did a special on him going back to Sing Sing

prison, so as a result of that, we found this interview with his

mother.”

What was the advantage of working with NC Heikin again?

NC is a visionary. She takes risks as a filmmaker. She’s not a trained

filmmaker. Her background is in the musical theatre. Because there is so

much music involved in this, she brings almost a theatrical quality to

documentary filmmaking. We got some of the great legends of jazz that

knew Frank.”

Visit the Frank Morgan Project website for more information.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Morgan_(musician)

Frank Morgan (musician)

Frank Morgan (December 23, 1933 – December 14, 2007) was a jazz saxophonist with a career spanning more than 50 years.[1] He mainly played alto saxophone but also played soprano saxophone. He was known as a Charlie Parker successor who primarily played bebop and ballads.[2]

Biography

Early life (1933–1947)

Frank Morgan was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1933, but spent most of his childhood living with his grandmother in Milwaukee, Wisconsin while his parents were on tour. Morgan's father Stanley was a guitarist with Harlan Leonard and the Rockets and The Ink Spots, and his mother, Geraldine, was a 14-year-old student when she gave birth to him. Morgan took up his father's instrument at an early age, but lost interest the moment he saw Charlie Parker take his first solo with the Jay McShann band at the Paradise Theater in Detroit, Michigan. Stanley introduced them backstage, where Parker offered Morgan advice about starting out on the alto sax, and they met at a music store the following day. Morgan, seven years old at the time, assumed they'd be picking out a saxophone, but Parker suggested he start on the clarinet to develop his embouchure. Morgan practiced on the clarinet for about two years before acquiring a soprano sax, and finally, an alto. Morgan moved to live with his father (by that time divorced) in Los Angeles, California at the age of 14, after his grandmother caught him with marijuana.[3][4][5]

Los Angeles (1947–1955)

As a teenager Morgan had opportunities to jam with the likes of Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray on Sunday afternoons at the Crystal Tearoom. When he was just 15 years old, Morgan was offered Johnny Hodges's spot in Duke Ellington's Orchestra, but Stanley deemed him too young for touring. Instead he joined the house band at Club Alabam where he backed vocal luminaries such as Billie Holiday and Josephine Baker.[4] That same year he won a television talent-show contest, the prize of which was a recording session with the Freddy Martin Orchestra, playing "Over the Rainbow" in an arrangement by Ray Conniff, with vocals by Merv Griffin.[3] Morgan attended Jefferson High School during the day, where he played in the school big band that also spawned jazz greats Art Farmer, Ed Thigpen, Chico Hamilton, Sonny Criss, and Dexter Gordon.[6] Morgan stayed in contact with Parker during these years, finding himself in jam sessions at Hollywood celebrities' homes when Parker visited L.A.[5] In 1952, Morgan earned a spot in Lionel Hampton's band, but his first arrest in 1953 prevented him from joining the Clifford Brown and Max Roach quintet (that role went instead to Harold Land, and later, Sonny Rollins).[3] He made his recording debut on February 20, 1953 with Teddy Charles and his West Coasters in a session for Prestige Records. This sextet featured short-lived tenor player Wardell Gray and was included on the 1983 posthumous release Wardell Gray Memorial Volume 1.[7][8] On November 1, 1954, Morgan cut five tracks with the Kenny Clarke Sextet for Savoy Records, four of which were released with Clarke billed as the leader, with "I've Lost Your Love" credited to writer Milt Jackson as leader.[9] Morgan recorded an all-star date with Wild Bill Davis and Conte Candoli on January 29, 1955 and participated in a second recording session on March 31, 1955 with Candoli, Wardell Gray, Leroy Vinnegar and others, which were combined and released in 1955 as Morgan's first album, Frank Morgan, by GNP Crescendo Records. Later releases also included five tracks cut at the Crescendo Club in West Hollywood on August 11, 1956 with a sextet featuring Bobby Timmons and Jack Sheldon. The album copy hailed Morgan as the new Charlie Parker, who had died the same year. In his own words, Morgan was "scared to death" by this and "self-destructed."[5][10]

Addiction and incarceration (1955–1985)

Following in the footsteps of Parker, Morgan had started taking heroin at 17, subsequently became addicted, and spent much of his adult life in and out of prison.[4] Morgan supported his drug habit through check forgery and fencing stolen property.[3] His first drug arrest came in 1955, the same year his debut album was released, and Morgan landed in San Quentin State Prison in 1962, where he formed a small ensemble with another addict and sax player, Art Pepper. His final incarceration, for which Morgan had turned himself in on a parole violation, ended on December 7, 1986.[4][11] Though he stayed off heroin for the last two decades of his life, Morgan took methadone daily.[6]

Comeback (1985–2007)

Fresh out of prison in April, 1985, Morgan started recording again, releasing Easy Living on Contemporary Records that June.[4] Morgan performed at the Monterey Jazz Festival on September 21, 1986, and turned down an offer to play Charlie Parker in Clint Eastwood's film Bird (Forest Whitaker took his place).[6] He made his New York debut in December 1986 at the Village Vanguard, and collaborated with George W.S. Trow on Prison-Made Tuxedos, a semi-autobiographical Off-Broadway play which included live music by the Frank Morgan Quartet (featuring Ronnie Mathews, Walter Booker, and Victor Lewis).[4][12][13] His 1990 album Mood Indigo went to number four on the Billboard jazz chart.[4] Morgan suffered a stroke in 1998, but subsequently recovered, recording and performing during the last four years of his life.[14] HighNote Records eventually released three albums worth of material from a three-night stand at the Jazz Standard in New York City in November, 2003. Morgan also participated in the 2004 Charlie Parker Jazz Festival in Tompkins Square Park.[15]

After moving to Minneapolis in the fall of 2005, Morgan headlined the 2006 Twin Cities Hot Summer Jazz Festival and played duets with Ronnie Mathews at the Dakota Jazz Club in Minneapolis and George Cables at the Artists' Quarter in St. Paul. Morgan also performed at the 2006 East Coast Jazz Festival in Washington, D.C., and on the West Coast at Yoshi's and Catalina's.[6][16] His last gig in Minneapolis featured Grace Kelly, Irv Williams, and Peter Schimke at the Dakota on July 1, 2007.[17]

For one of Morgan's final recordings, he composed and recorded music for the audiobook adaptation of Michael Connelly's crime novel The Overlook (2007), providing brief unaccompanied sax solos at the beginning and end of the book, and between chapters. Morgan is mentioned in the book by lead character Harry Bosch, a jazz enthusiast.

Shortly before his death, Morgan completed his first tour of Europe.[18]

Death

Frank Morgan died in Minneapolis on Friday, December 14, 2007 from complications due to colorectal cancer, nine days before his 74th birthday. A memorial service featuring members of Morgan's family and a performance by Irv Williams was held at the Artists' Quarter on Sunday, December 23.[18]

Legacy

The New York Times editor Peter Keepnews wrote that Frank Morgan was "a leading figure in the jazz revival of the late ’80s, a living reminder of bebop’s durability."[14] Writing in JazzTimes, David Franklin described Morgan as having a "sweet, singing tone" and praised his "subtle use of dynamic contrast" and "mature self-assuredness" which complemented his "youthful exuberance."[19][20] The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD called Morgan "a passionate improviser" who "organizes his solos in a songful, highly logical way."[21] Comparing Morgan and Art Pepper, C. Michael Bailey wrote that "both possessed a beautifully spearmint-dry ice tone in their early careers and both were unsurpassed as ballad interpreters," and that Morgan showed "why bop still matters so much."[22] Author Michael Connelly co-produced a documentary film about Morgan, Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story, directed by N.C. Heikin, which had its world premiere at the Los Angeles Film Festival on June 14, 2014 and was followed the next day by a tribute concert at The Grammy Museum, featuring George Cables, Ron Carter, Mark Gross, Grace Kelly, and Roy McCurdy.[23][24][25]

Discography

As leader

- Frank Morgan (Gene Norman Presents, 1955)

- Easy Living (Contemporary, 1985)

- Lament (Contemporary, 1986)

- Double Image (Contemporary, 1986)

- Bebop Lives! (Contemporary, 1986)

- Major Changes (Contemporary, 1987)

- Yardbird Suite (Contemporary, 1988)

- Reflections (Contemporary, 1989)

- Mood Indigo (Antilles, 1989)

- A Lovesome Thing (Antilles, 1990)

- Quiet Fire (Contemporary, 1987 [1991]) with Bud Shank

- You Must Believe in Spring (Antilles, 1992)

- Listen to the Dawn (Antilles, 1993)

- Love, Lost & Found (Telarc, 1995)

- Bop! (Telarc, 1996)

- City Nights: Live at the Jazz Standard (HighNote, 2004)

- Raising the Standard (HighNote, 2003 [2005])

- Reflections (HighNote, 2006)

- A Night in the Life (HighNote, 2003 [2007])

- Twogether (HighNote, 2005 [2010]) with John Hicks

- Montreal Memories (HighNote, 1989 [2018]) with George Cables

As sideman

With Milt Jackson

- Meet Milt Jackson (Savoy, 1954)

With Kenny Clarke

- Telefunken Blues (Savoy, 1955)

With Lyle Murphy

- Four Saxophones in Twelve Tones (GNP/Crescendo, 1955)

With L. Subramaniam

With Wardell Gray

- Wardell Gray Memorial, Vol. 1 (Prestige, 1983) recorded in 1953

With Mark Murphy

- Night Mood (Milestone, 1986)

With Terry Gibbs

- The Latin Connection (Contemporary, 1986)

With Art Farmer

- Central Avenue Reunion (Contemporary, 1990)

With Ben Sidran

- Mr. P's Shuffle (Go Jazz, 1996)

With Abbey Lincoln

- Who Used to Dance (Verve, 1996)

References

- "Frank Morgan Tribute - 2014 Los Angeles Film Festival." 20th LA Film Fest. Web. 16 June 2014.

External links

- Frank Morgan discography at Discogs

- Frank Morgan on IMDb

- Frank Morgan at Find a Grave

https://www.michaelconnelly.com/extras/sound/

Sound of Redemption – The Frank Morgan Story

by Michael Connelly

The late jazz saxophonist Frank Morgan’s tale of redemption from drug addict, conman and convict to beloved elder statesman of jazz. Produced by Michael Connelly.

Download on iTunes Movies.

Order The DVD From Amazon.

Order The DVD and Download From Kino Lorber.

Packed with thrilling music, Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story is an absorbing documentary about a gifted alto sax player and Charlie Parker’s protégée, Frank Morgan. Morgan fell hard into heroin and got to be almost as good a conman and thief as he was a musician in order to feed his habit. The habit cost him 30 years of his life in and out of prison, most of it at San Quentin, where he performed in a big band with fellow junkie jazz musicians that grew famous in the Bay Area. To bring the past into the present, director NC Heikin brought an all-star band together into the “Q” for a concert. This hyper-emotional event forms the backbone of this riveting film.

This documentary film was directed by N.C. Heikin, and produced by James Egan. Visit the film’s Facebook page. See more video clips here.

“2015 has been a great year for music docs, with films about Amy Winehouse, Nina Simone, Kurt Cobain and the Wrecking Crew all scoring with audiences and critics. And here, at year’s end, comes “Sound of Redemption” — as good as any.” – Los Angeles Times

“it’s a fond and forgiving tribute to the man, filled with music that moves beyond happy and sad, and toward something like brilliance.” – New York Times

“N.C. Heikin’s hurtin’ beauty of a doc”- The Village Voice

“the film has a strong feel for the emotion behind Frank Morgan’s acclaimed bebop.” – The Hollywood Reporter

“Heikin’s best inspiration is to stage and film a tribute concert at San Quentin. Grace Kelly’s tender “Over the Rainbow” solo might stir tears, and Heikin, unlike so many impatient directors, knows that in a doc about musicians, the music should breathe.” – LA Weekly

“Sound of Redemption is a great documentary that paints a fascinating picture of a talented musician whose music helped him get through the most difficult years of his life.” – RedCarpetCrash.com

“N.C. Heikin’s terrific music documentary interweaves a great concert by the late jazzman’s admirers and acolytes at the Bay Area prison with a stirring history of both the L.A. music scene and mid-century, African American show business in general. But really, the kickiest part is when it recounts the ingenious criminal schemes Morgan dreamed up to support his gargantuan heroin habit.” – Los Angeles Daily News

“If you’re a Jazz fan but unfamiliar with the Charlie Parker protege Frank Morgan, “Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story” will school you on a saxophone virtuoso and convict who lived what sounds like four adventurous, glamorous, tragic lives while earning the title “the new Bird.” “Redemption” traces how deep the comparisons cut into Morgan’s psyche.” – RogerEbert.com

“Morgan’s “redemption” came at a high price, and the film effectively balances realism and optimism in portraying his deeply troubled yet fulfilling life.” – Victor L. Schermer, All About Jazz

A Note From Michael

My involvement in Sound of Redemption is purely an effort to honor an artist who inspired me and had a life message that is worth sharing around the world.

I can’t say that Frank and I went way back as was the relationship with many of the people we have interviewed for the film. Though I first saw Frank on the stage about twenty years ago, it wasn’t until the last few years of his life that I started to personally get to know him. He was in his 70s, hunched over by time, but still playing and persevering. He had overcome many difficulties, from drug addiction to incarceration to the debilitating effects of a recent stroke. He had been through all of that and still had a beautiful smile and a beautiful sound. To me he was amazing.

I would say the connection I had with Frank came down to one song. “Lullaby,” the short and somehow sad song written by pianist and longtime Frank Morgan collaborator George Cables, seared me from the first time I heard it more than twenty years ago. At the time I was putting together a character for a book I was writing. The character was a detective who was a loner and liked to listen to and draw inspiration from jazz. The character – I would name him Harry Bosch – had a particular affinity for the saxophone. Its mournful sound, like a human crying out in the night, was what he was drawn to. The detective saw the worst of humanity every day on the job. He found solace every night in the sound of the saxophone.

At the time, Frank Morgan had just put out his album Mood Indigo. It got solid reviews and a lot attention in the jazz world and beyond. I read about it and read about him. It was a perfect set up because Harry Bosch did more than simply listen to the music. He identified with the musicians. I wanted him to listen to musicians who had overcome the odds to make their music because Harry had overcome great odds himself. Frank, with his history, was a perfect candidate. I went out and got the album and as they say, the rest is history. I don’t think I had ever been so emotionally moved by a record. It begins and ends with a cut of “Lullaby.” The song is short but its message is strong. It contains everything about Frank and everything about Harry. Sad and mournful, yet strong and resilient. The song is relentless in Frank Morgan’s hands. The song pierced my heart. I knew I had found Bosch’s anthem. I started playing the song each day before writing. It inspired me as well as Harry Bosch.

Many years later I got to tell Frank Morgan about the process I went through and how I discovered his sound and what it meant to both me and Harry Bosch. We were sitting in a restaurant in a hotel we were staying at in Boston. We had come in to appear together at the Berklee College of Music. Frank was going to give a master class to the saxophone students and then after we would be on stage together to talk about the symbiotic relationship between words and music. Frank was tired but happy. He talked about wanting to give back for what he considered a blessed life. He wanted to tell young musicians not to make the mistakes he had made.

The day after, as we rode in a car to the airport, Frank said he loved being with the young musicians and that he wanted to do it again. He said there were wonderful programs for young musicians in Indiana and New Orleans and other places. He wanted to go to them. He wanted us to go there and asked me to set it up. He said he already had a European tour scheduled but after that he’d be ready to go.

Well, Frank did go to Europe but he got sick. We never made it to Indiana or New Orleans. He died shortly after he got back. I feel bad about what could have been, about the musicians Frank could have reached with his unique story. My hope is that this film will capture the essence of that story and spread Frank’s message further than he ever thought.

Frank Morgan [with Cedar Walton Trio] –

Frank Morgan - Lullaby

Frank Morgan - On Green Dolphin Street

Frank Morgan - It's Only a Paper Moon

Frank Morgan (1990)

Frank Morgan - Quiet Fire - Solar

Mood Indigo

Frank Morgan - Confirmation (Live)

Frank Morgan - It's Only a Paper Moon (Live)

Frank Morgan - Bessie's Blues (Live at the Jazz

Frank Morgan - Impressions

![Tribute to Charlie Parker [Video]](https://rovimusic.rovicorp.com/image.jpg?c=jNAOq_M91HnQJQngakwKB4Af7E_1E-2MlBBPmPAXRBU=&f=3)