SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2020

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER TWO

HERBIE HANCOCK

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

RICHARD DAVIS

(February 22-28)

JAKI BYARD

(February 29-March 6)

CHARLES LLOYD

(March 7-13)

CHICO HAMILTON

(March 14-20)

JOHNNY HODGES

(March 21-27)

LEADBELLY

(March 28-April 3)

SIDNEY BECHET

(April 4-April 10)

DON BYAS

(April 11-17)

FLETCHER HENDERSON

(April 18-24)

JIMMY LUNCEFORD

(April 25-May 1)

KING OLIVER

(May 2-8)

WAR

(May 9-15)

The roots of War lay in an R&B cover band called the Creators. Guitarist Howard Scott and drummer Harold Brown started the group in 1962 while attending high school in the Compton area, and three years later, the lineup also featured keyboardist Leroy "Lonnie" Jordan, bassist Morris "B.B." Dickerson, and saxophonist/flutist Charles Miller (all of them sang). The group had an appetite for different sounds right from the start, ranging from R&B to blues to the Latin music they'd absorbed while growing up in the racially mixed ghettos of Los Angeles. Despite a two-year hiatus following Scott's induction into the service, they released several singles locally on Dore Records (their first, "Burn Baby Burn," was with singer Johnny Hamilton), and backed jazz saxophonist Tjay Contrelli, formerly of the psychedelic band Love; they also went by the names the Romeos and Señor Soul during this period. In 1968, the band was reconfigured and dubbed Nightshift; Peter Rosen was the new bassist, and percussionist Thomas Sylvester "Papa Dee" Allen, who'd previously played with Dizzy Gillespie, came onboard, along with two more horn players. B.B. Dickerson later returned when Rosen died of a drug overdose. In 1969, Nightshift began backing football star Deacon Jones (a defensive end for the L.A. Rams) during his singing performances in a small club, where they were discovered by producer Jerry Goldstein. Goldstein suggested the band as possible collaborators to former Animals lead singer Eric Burdon, who along with Danish-born harmonica player Lee Oskar (born Oskar Levetin Hansen) had been searching L.A. clubs for a new act.

After witnessing Nightshift in concert, Burdon took charge of the group. He gave them a provocative new name, War, and replaced the two extra horn players with Oskar. To develop material, War began playing marathon concert jams over which Burdon would free-associate lyrics. In August 1969, Burdon and War entered the studio for the first time, and after some more touring, they recorded their first album, 1970's Eric Burdon Declares War. The spaced-out daydream of "Spill the Wine" was a smash hit, climbing to number three and establishing the group in the public eye. A second album, The Black Man's Burdon, was released before the year's end, and over the course of two records it documented the group's increasingly long improvisations (as well as Burdon's growing tendency to ramble). It also featured War's first recorded vocal effort on "They Can't Take Away Our Music." Burdon's contract allowed War to be signed separately, and they soon inked a deal with United Artists, intending to record on their own as well as maintaining their partnership with Burdon. However, Burdon -- citing exhaustion -- suddenly quit during the middle of the group's European tour in 1971, spelling the beginning of the end; he rejoined War for a final U.S. tour and then left for good.

War had already issued their self-titled, Burdon-less debut at the beginning of 1971, but it flopped. Before the year was out, they recorded another effort, All Day Music, which spawned their first Top 40 hits in "All Day Music" and "Slippin' Into Darkness"; the album itself was a million-selling Top 20 hit. War really hit their stride on the follow-up album, 1972's The World Is a Ghetto; boosted by a sense of multi-cultural harmony, it topped the charts and sold over three million copies, making it the best-selling album of 1973. It also produced two Top Ten smashes in "The Cisco Kid" (which earned them a fervent following in the Latino community) and the title ballad. 1973's Deliver the Word was another million-selling hit, reaching the Top Ten and producing the Top Ten single "Gypsy Man" and another hit in "Me and Baby Brother." However, it had less of the urban grit that War prided themselves on; while taking some time to craft new material and rethink their direction, War consolidated their success with the double concert LP War Live, recorded over four nights in Chicago during 1974.

Released in 1975, Why Can't We Be Friends returned to the sound of The World Is a Ghetto with considerable success. The bright, anthemic title track hit the Top Ten, as did "Low Rider," an irresistible slice of Latin funk that became the group's first (and only) R&B chart-topper, and still stands as their best-known tune. 1976 brought the release of a greatest-hits package featuring the new song "Summer," which actually turned out to be War's final Top Ten pop hit; the same year, Oskar released his first solo album, backed by members of Santana. A double-LP compilation of jams and instrumentals appeared on the Blue Note jazz label in 1977, under the title Platinum Jazz; it quickly became one of the best-selling albums in Blue Note history, and produced an R&B-chart smash with an edited version of "L.A. Sunshine."

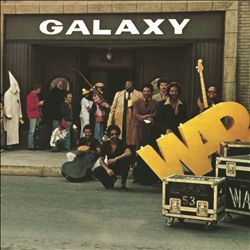

Yet disco was beginning to threaten the gritty, socially aware funk War specialized in. Later in 1977, the band switched labels, moving to MCA for Galaxy; though it sold respectably, and the disco-tinged title track was a hit on the R&B charts, it fizzled on the pop side, and proved to be the last time War would hit the Top 40. After completing the Youngblood soundtrack album in 1978, the original War lineup began to disintegrate. Dickerson left during the recording of 1979's The Music Band (which featured new female vocalist Alice Tweed Smith), and not long after, Charles Miller was murdered in a robbery attempt. After The Music Band was released, the remaining members attempted to refashion their image to fit the glitz of the era, and added some new personnel: bassist Luther Rabb, percussionist Ronnie Hammond, and saxophonist Pat Rizzo (ex-Sly & the Family Stone). The Music Band 2 flopped, and the group was thrown into disarray; Smith exited, and the follow-up took an uncharacteristic three years to prepare. Released in 1982, Outlaw was a moderate success; the title track was a Top 20 R&B hit, and "Cinco de Mayo" became a Latino holiday standard. Yet it didn't restore War's commercial standing. Rizzo left later in the year; Harold Brown followed in 1983, after Life Is So Strange flopped; and Rabb was replaced with Ricky Green in 1984. In the years that followed, War was essentially a touring outfit and nothing more. Papa Dee Allen collapsed and died on-stage of a brain aneurysm in 1988, leaving Jordan, Hammond, Oskar, and Scott as the core membership (Oskar would finally leave in 1992). Interest in War's classic material remained steady, however, thanks to frequent sampling of their grooves by hip-hop artists. 1992's Rap Declares War paired the band with a variety of rappers, paving the way for the 1994 comeback attempt Peace Sign; for that record, Brown returned on drums, and Jordan (now on bass), Scott, and Hammond were joined by saxophonists Kerry Campbell and Charles Green, percussionist Sal Rodriguez, harmonica player Tetsuya "Tex" Nakamura, and Brown's son, programmer Rae Valentine (plus guests Lee Oskar and José Feliciano). The album failed to chart, however, and the group returned to the touring circuit. Brown and Scott left the lineup in 1997.

Jordan continued to tour with a new version of the band in which he was the only original performing member. In 2008, War performed a one-off reunion date with Eric Burdon at London's Royal Albert Hall as a precursor to the Rhino reissues of his albums with the band, and a pair of compilations. Later that year, Jordan's War issued the audio/video live package entitled Greatest Hits Live, covering material from the band's best-known era, 1969-1975. In 2009 the group was nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but failed to secure enough votes for induction.

From 2009 on, War was a steady concert draw, either on the nostalgia group tour circuit or playing at festivals internationally. In 2014, the band issued Evolutionary on Universal, its first new album of studio material in a decade. The set was combined with the additional disc of its classic Greatest Hits album as an added incentive to consumers.

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/war-mn0000191947/biography

WAR

(1969-Present)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

One of the most popular funk groups of the '70s, War were also one of the most eclectic, freely melding soul, Latin, jazz, blues, reggae, and rock influences into an effortlessly funky whole. Although War's lyrics were sometimes political in nature (in keeping with their racially integrated lineup), their music almost always had a sunny, laid-back vibe emblematic of their Southern California roots. War kept the groove loose, and they were given over to extended jamming; in fact, many of their studio songs were edited together out of longer improvisations. Even if the jams sometimes got indulgent, they demonstrated War's truly group-minded approach: no one soloist or vocalist really stood above the others (even though all were clearly talented), and their grooving interplay placed War in the top echelon of funk ensembles.

The roots of War lay in an R&B cover band called the Creators. Guitarist Howard Scott and drummer Harold Brown started the group in 1962 while attending high school in the Compton area, and three years later, the lineup also featured keyboardist Leroy "Lonnie" Jordan, bassist Morris "B.B." Dickerson, and saxophonist/flutist Charles Miller (all of them sang). The group had an appetite for different sounds right from the start, ranging from R&B to blues to the Latin music they'd absorbed while growing up in the racially mixed ghettos of Los Angeles. Despite a two-year hiatus following Scott's induction into the service, they released several singles locally on Dore Records (their first, "Burn Baby Burn," was with singer Johnny Hamilton), and backed jazz saxophonist Tjay Contrelli, formerly of the psychedelic band Love; they also went by the names the Romeos and Señor Soul during this period. In 1968, the band was reconfigured and dubbed Nightshift; Peter Rosen was the new bassist, and percussionist Thomas Sylvester "Papa Dee" Allen, who'd previously played with Dizzy Gillespie, came onboard, along with two more horn players. B.B. Dickerson later returned when Rosen died of a drug overdose. In 1969, Nightshift began backing football star Deacon Jones (a defensive end for the L.A. Rams) during his singing performances in a small club, where they were discovered by producer Jerry Goldstein. Goldstein suggested the band as possible collaborators to former Animals lead singer Eric Burdon, who along with Danish-born harmonica player Lee Oskar (born Oskar Levetin Hansen) had been searching L.A. clubs for a new act.

After witnessing Nightshift in concert, Burdon took charge of the group. He gave them a provocative new name, War, and replaced the two extra horn players with Oskar. To develop material, War began playing marathon concert jams over which Burdon would free-associate lyrics. In August 1969, Burdon and War entered the studio for the first time, and after some more touring, they recorded their first album, 1970's Eric Burdon Declares War. The spaced-out daydream of "Spill the Wine" was a smash hit, climbing to number three and establishing the group in the public eye. A second album, The Black Man's Burdon, was released before the year's end, and over the course of two records it documented the group's increasingly long improvisations (as well as Burdon's growing tendency to ramble). It also featured War's first recorded vocal effort on "They Can't Take Away Our Music." Burdon's contract allowed War to be signed separately, and they soon inked a deal with United Artists, intending to record on their own as well as maintaining their partnership with Burdon. However, Burdon -- citing exhaustion -- suddenly quit during the middle of the group's European tour in 1971, spelling the beginning of the end; he rejoined War for a final U.S. tour and then left for good.

War had already issued their self-titled, Burdon-less debut at the beginning of 1971, but it flopped. Before the year was out, they recorded another effort, All Day Music, which spawned their first Top 40 hits in "All Day Music" and "Slippin' Into Darkness"; the album itself was a million-selling Top 20 hit. War really hit their stride on the follow-up album, 1972's The World Is a Ghetto; boosted by a sense of multi-cultural harmony, it topped the charts and sold over three million copies, making it the best-selling album of 1973. It also produced two Top Ten smashes in "The Cisco Kid" (which earned them a fervent following in the Latino community) and the title ballad. 1973's Deliver the Word was another million-selling hit, reaching the Top Ten and producing the Top Ten single "Gypsy Man" and another hit in "Me and Baby Brother." However, it had less of the urban grit that War prided themselves on; while taking some time to craft new material and rethink their direction, War consolidated their success with the double concert LP War Live, recorded over four nights in Chicago during 1974.

Released in 1975, Why Can't We Be Friends returned to the sound of The World Is a Ghetto with considerable success. The bright, anthemic title track hit the Top Ten, as did "Low Rider," an irresistible slice of Latin funk that became the group's first (and only) R&B chart-topper, and still stands as their best-known tune. 1976 brought the release of a greatest-hits package featuring the new song "Summer," which actually turned out to be War's final Top Ten pop hit; the same year, Oskar released his first solo album, backed by members of Santana. A double-LP compilation of jams and instrumentals appeared on the Blue Note jazz label in 1977, under the title Platinum Jazz; it quickly became one of the best-selling albums in Blue Note history, and produced an R&B-chart smash with an edited version of "L.A. Sunshine."

Yet disco was beginning to threaten the gritty, socially aware funk War specialized in. Later in 1977, the band switched labels, moving to MCA for Galaxy; though it sold respectably, and the disco-tinged title track was a hit on the R&B charts, it fizzled on the pop side, and proved to be the last time War would hit the Top 40. After completing the Youngblood soundtrack album in 1978, the original War lineup began to disintegrate. Dickerson left during the recording of 1979's The Music Band (which featured new female vocalist Alice Tweed Smith), and not long after, Charles Miller was murdered in a robbery attempt. After The Music Band was released, the remaining members attempted to refashion their image to fit the glitz of the era, and added some new personnel: bassist Luther Rabb, percussionist Ronnie Hammond, and saxophonist Pat Rizzo (ex-Sly & the Family Stone). The Music Band 2 flopped, and the group was thrown into disarray; Smith exited, and the follow-up took an uncharacteristic three years to prepare. Released in 1982, Outlaw was a moderate success; the title track was a Top 20 R&B hit, and "Cinco de Mayo" became a Latino holiday standard. Yet it didn't restore War's commercial standing. Rizzo left later in the year; Harold Brown followed in 1983, after Life Is So Strange flopped; and Rabb was replaced with Ricky Green in 1984. In the years that followed, War was essentially a touring outfit and nothing more. Papa Dee Allen collapsed and died on-stage of a brain aneurysm in 1988, leaving Jordan, Hammond, Oskar, and Scott as the core membership (Oskar would finally leave in 1992). Interest in War's classic material remained steady, however, thanks to frequent sampling of their grooves by hip-hop artists. 1992's Rap Declares War paired the band with a variety of rappers, paving the way for the 1994 comeback attempt Peace Sign; for that record, Brown returned on drums, and Jordan (now on bass), Scott, and Hammond were joined by saxophonists Kerry Campbell and Charles Green, percussionist Sal Rodriguez, harmonica player Tetsuya "Tex" Nakamura, and Brown's son, programmer Rae Valentine (plus guests Lee Oskar and José Feliciano). The album failed to chart, however, and the group returned to the touring circuit. Brown and Scott left the lineup in 1997.

Jordan continued to tour with a new version of the band in which he was the only original performing member. In 2008, War performed a one-off reunion date with Eric Burdon at London's Royal Albert Hall as a precursor to the Rhino reissues of his albums with the band, and a pair of compilations. Later that year, Jordan's War issued the audio/video live package entitled Greatest Hits Live, covering material from the band's best-known era, 1969-1975. In 2009 the group was nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but failed to secure enough votes for induction.

From 2009 on, War was a steady concert draw, either on the nostalgia group tour circuit or playing at festivals internationally. In 2014, the band issued Evolutionary on Universal, its first new album of studio material in a decade. The set was combined with the additional disc of its classic Greatest Hits album as an added incentive to consumers.

War (Rhythm & Blues Group) (1969-Present)

War is an R&B multi-cultural group that was created in 1969 and rose up to fame during the 1970s. The band originated from a high school R&B group called The Creators founded by Harold Brown and Harold E. Scott in 1962 in Long Beach, California. Within a few years Charles Miller, Morris Dickerson, Lonnie Jordan, Lee Oskar, and Papa Allen became a part of The Creators. The group was racially mixed and shared a love of diverse styles of music as most of the members grew up in racially mixed neighborhoods in Los Angeles. The Creators recorded several singles with Doré Records. In 1968, The Creators became Nightshift due to Harold Brown working night shifts at a steel yard.

In 1969 record producer Jerry Goldstein and Eric Burdon, former lead singer of the Animals, saw the group perform as background singers for Deacon Jones at the Rag Doll in North Hollywood. Goldstein became attracted to the band’s sound and their message of promoting brotherhood and harmony and using instruments and vocals to speak against racism, hunger, gangs, crimes, and turf wars. Goldstein signed the group and soon afterwards Nightshift became War. Performing with Eric Burdon throughout Southern California helped build their audience. Their debut album was in fact titled Eric Burdon Declares War when it was released in March 1970. The album produced “Spill the Wine,” the hit song that launched the band’s career.

The success of the Eric Burdon Declares War album resulted in an extensive tour through the United States and Europe. This successful tour led Eric Burdon and War to collaborate on a second album, The Black-Man’s Burdon which was also released in 1970. After the album was released Burdon decided to leave the group during their European tour. Despite the setback, the group went on to finish the tour and re-record their first album as War.

In 1971, the band released their third album, All Day Music, which included two very successful tracks, “All Day Music” and “Slippin’ into Darkness.” Both singles sold over one million copies and were awarded a gold disc by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in in June 1972.

In 1972, War released The World is a Ghetto, which became their most successful album. One of its tracks, “The Cisco Kid,” became a gold single while the album itself rose to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart in 1972 and became Billboard Magazine’s Album of the Year as the best-selling album of 1973.

War went on to release its “Greatest Hits” album in 1974 which included previously unreleased tracks that included Eric Burdon as lead singer. As musical tastes shifted to disco, War failed to duplicate its success of the early 1970s. In 1980, the group lost Charles Miller, who was murdered. The group finally disbanded in 1996 as its members pursued solo careers.

https://radiofacts.com/that-time-when-war-shouldered-the-weight-of-the-worldsmoggy-eyed/

That Time When WAR Shouldered the Weight of

the World…Smoggy-Eyed

Leroy “Lonnie” Jordan Talks About Nearly 50 Years of WAR’s Great Music

Bubbling up from the streets of Long

Beach in 1969, a group of musicians coalesced into the band WAR. Joined

initially, somewhat improbably but successfully by British belter Eric

Burdon, WAR leapt out of the radio with their hit “Spill The Wine.” A

string of radio-friendly hits followed, tracks that have gently eased

into heavy rotation and timelessness: “The World Is a Ghetto,” “The

Cisco Kid,” “Low Rider,” “East L.A.,” “Summer” and “Why Can’t We Be

Friends?”

I spoke with Leroy “Lonnie” Jordan, the singer and keyboardist of the band. He called me, and there was the Long Beach area code right on my mobile phone screen.

As the sole remaining original member, Jordan keeps the flame alive. I had a wide ranging chat with him.

Auerbach: How does touring compare to back in the day?

Jordan: Touring today is better because I can see more clearly what is going around me, not due to lighting but due to the perspective of age. It’s not just about fun, I now take my message more serious.

Auerbach: And the recording process has certainly changed since when you first started.

Jordan: It certainly has. Today the recording process has all gone digital, it’s about pushing a button. Every style has its own method of madness.

Auerbach: Do you consider WAR a funk band?

Jordan: It is hard to put a label on us, it is hard to put a library card on us. Tower Records had us in a lot of departments, jazz, reggae, RnB. Universal Street Music, that is what I call us. We covered many categories, which is probably why we didn’t win many awards, because they did not know where to put us. But our sound did not isolate us from the rest of the world.

Auerbach: How did the song “Lowrider” come about?

Jordan: No one else wrote about that style of car. There was a car club song “The In Crowd” by Dobie Gray, before he did “Drift Away.” So we wrote about it, and we had the cars – metal flaked, dropped, with record players installed. We knew the two rival car clubs, The Imperials and The Dukes, we brought them together. We gave the song to the clubs, they blasted the song out of their cars and bam the song took off. We used the car club film as backdrops, no one beyond Albuquerque knew about low riders until our song came out!

Auerbach: And how about “Slippin’ Into Darkness,” I love the vibe of that track, where did that song come from?

Jordan: Like most of the songs, it came out of long, multi hour jams. We’d then sit back and listen to the jams. The song has the attitude of gospel, it’s about a mother telling us to go in the right direction, don’t go into the dark path. You know what? I heard it on a gospel program in the 70s. “Trippin’ into Darkness” is how some people rephrased it.

Auerbach: And how about “Summer,” how did that somg come about? Growing up in Buffalo with those winters, I have always loved that track.

Jordan: “Summer” was actually inspired by New York City, and a heatwave. We never put a city name in the song, we wanted to keep it universal.

Auerbach: So let me ask you about the idea of a digital tip jar, which my brother came up with. What if folks streaming your music could leave a few dollars that go directly to the artist?

Jordan: A digital tip jar is a very interesting idea. You’d have a lot of red tape to get through, a lot of middlemen want to get a piece of the action. I’d love it. But capital gains and the tax man might get there as well.

Auerbach: Do you still get along with Eric [Burdon, who left the band fairly early]?

Jordan: Definitely, we still get along with Eric, and we are trying to get a reunion again, like we did a few years ago at Royal Albert Hall [in London]. We are looking at maybe a tour. You know, in recording “Spill the Wine” he improvised the song. The chorus [‘spill the wine, take that pearl’], people think it is ‘girl.’ But it is ‘pearl,’ that’s the lady’s nether regions.

Auerbach: You have had decades of gigs, do you have one or two that stand out?

WAR plays the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles this summer with George Clinton & Parliament Funkadelic on Saturday, May 26 at 7:00 PM. They will be joined by special guest Nortec Collective Presents: Bostich + Fussible. Tickets available via AXS.com.

https://www.songfacts.com/blog/interviews/harold-brown-of-war

I spoke with Leroy “Lonnie” Jordan, the singer and keyboardist of the band. He called me, and there was the Long Beach area code right on my mobile phone screen.

As the sole remaining original member, Jordan keeps the flame alive. I had a wide ranging chat with him.

Auerbach: How does touring compare to back in the day?

Jordan: Touring today is better because I can see more clearly what is going around me, not due to lighting but due to the perspective of age. It’s not just about fun, I now take my message more serious.

Auerbach: And the recording process has certainly changed since when you first started.

Jordan: It certainly has. Today the recording process has all gone digital, it’s about pushing a button. Every style has its own method of madness.

Leroy “Lonnie” Jordan

Jordan: It is hard to put a label on us, it is hard to put a library card on us. Tower Records had us in a lot of departments, jazz, reggae, RnB. Universal Street Music, that is what I call us. We covered many categories, which is probably why we didn’t win many awards, because they did not know where to put us. But our sound did not isolate us from the rest of the world.

Auerbach: How did the song “Lowrider” come about?

Jordan: No one else wrote about that style of car. There was a car club song “The In Crowd” by Dobie Gray, before he did “Drift Away.” So we wrote about it, and we had the cars – metal flaked, dropped, with record players installed. We knew the two rival car clubs, The Imperials and The Dukes, we brought them together. We gave the song to the clubs, they blasted the song out of their cars and bam the song took off. We used the car club film as backdrops, no one beyond Albuquerque knew about low riders until our song came out!

Auerbach: And how about “Slippin’ Into Darkness,” I love the vibe of that track, where did that song come from?

Jordan: Like most of the songs, it came out of long, multi hour jams. We’d then sit back and listen to the jams. The song has the attitude of gospel, it’s about a mother telling us to go in the right direction, don’t go into the dark path. You know what? I heard it on a gospel program in the 70s. “Trippin’ into Darkness” is how some people rephrased it.

Auerbach: And how about “Summer,” how did that somg come about? Growing up in Buffalo with those winters, I have always loved that track.

Jordan: “Summer” was actually inspired by New York City, and a heatwave. We never put a city name in the song, we wanted to keep it universal.

Auerbach: So let me ask you about the idea of a digital tip jar, which my brother came up with. What if folks streaming your music could leave a few dollars that go directly to the artist?

Jordan: A digital tip jar is a very interesting idea. You’d have a lot of red tape to get through, a lot of middlemen want to get a piece of the action. I’d love it. But capital gains and the tax man might get there as well.

Auerbach: Do you still get along with Eric [Burdon, who left the band fairly early]?

Jordan: Definitely, we still get along with Eric, and we are trying to get a reunion again, like we did a few years ago at Royal Albert Hall [in London]. We are looking at maybe a tour. You know, in recording “Spill the Wine” he improvised the song. The chorus [‘spill the wine, take that pearl’], people think it is ‘girl.’ But it is ‘pearl,’ that’s the lady’s nether regions.

Auerbach: You have had decades of gigs, do you have one or two that stand out?

A real special gig was with Eric Burdon in our early days. We played Ronnie Scott’s [in London] for five days, Hendrix sat in with us for what became his last gig. Jimi took us back to where we started, at hole in the wall gigs backing up Little Richard and all the others. We had met Jimi back in the day. When we jammed with him that night, he played with no special effects, it was all simple blues. We jammed on “Mother Earth” by Memphis Slim for one hour. Jimi went back to his flat and passed away, back to Mother Earth. That is something I will never forget.

WAR plays the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles this summer with George Clinton & Parliament Funkadelic on Saturday, May 26 at 7:00 PM. They will be joined by special guest Nortec Collective Presents: Bostich + Fussible. Tickets available via AXS.com.

https://www.songfacts.com/blog/interviews/harold-brown-of-war

Songwriter Interviews

Harold Brown of War

by Carl Wiser

As

drummer for the band War, Harold Brown was part of the vibrant music

scene of the late-'60s and early-'70s that included Jim Morrison, Jimi

Hendrix, and Bob Marley. With War, Harold came up with a distinct and

influential drumming style, and was a key contributor in a band that

leaves a lasting legacy of fellowship and funk, with songs like "Low

Rider," "Spill The Wine" and "Why Can't We Be Friends?"

In the mid-'90s, the band's manager Jerry Goldstein won control of the name, and with his authorization, original keyboardist Lonnie Jordan began touring as War with other musicians. The four other living original members of the band, including Harold, cannot use the name and perform as The Lowrider Band.

In the mid-'90s, the band's manager Jerry Goldstein won control of the name, and with his authorization, original keyboardist Lonnie Jordan began touring as War with other musicians. The four other living original members of the band, including Harold, cannot use the name and perform as The Lowrider Band.

The business side of the story is

complicated and a little shady; especially sad considering the spirit of

unity that drove the band. In this interview, Harold tells the inside

story, covering the Eric Burdon years, playing with Hendrix the night before he

died, the stories behind their famous songs, and where it all went

wrong in the end.

Carl Wiser (Songfacts): You've done other stuff besides just play music in your life, haven't you?

Harold Brown: The band, we actually started together when we were in high school – Howard Scott and I. I can remember just as vividly, Howard's father, BB's (Dickerson) father, and my daddy used to take us to gigs because we were too young to drive. We were doing our first gig in Compton, and we were taking our equipment on some wagon to do the show. It was just wild. So we started back in about 1961, and we made ourselves The Creators. And that was because at that time, all the little clubs that we'd play in South Los Angeles, and then Long Beach and the South Bay area in California, they always said, "You've got to play what's on the juke box." So we would get the records and we would learn how to play those records, but after we played the main motif of the music, we would go right to the middle, we would go into a big old jam session, we'd just start playing anything we wanted to play. We had one rule: whoever's leading the song came back, go to the head, go to the top, then comes back to that main motif. So if we were doing a James Brown "I Feel Good" or something, we'd play the whole thing all the way through, then we'd go into our jam, then we'd come out. We were playing Bobby Blue Bland, Booker T and the MGs... there were so many different people that we'd emulate. I remember Old Man Jeffty, South Los Angeles - we thought we were just as hot as James Brown, because our band was tight, we were just kids - and he looked at us and he said, 'Let me ask you this question: if you were playing here and James Brown was down the street, who would they go see?' Well of course, James Brown. So that's when we started consciously trying to come up with our own sound, not trying to imitate somebody else.

Harold Brown: The band, we actually started together when we were in high school – Howard Scott and I. I can remember just as vividly, Howard's father, BB's (Dickerson) father, and my daddy used to take us to gigs because we were too young to drive. We were doing our first gig in Compton, and we were taking our equipment on some wagon to do the show. It was just wild. So we started back in about 1961, and we made ourselves The Creators. And that was because at that time, all the little clubs that we'd play in South Los Angeles, and then Long Beach and the South Bay area in California, they always said, "You've got to play what's on the juke box." So we would get the records and we would learn how to play those records, but after we played the main motif of the music, we would go right to the middle, we would go into a big old jam session, we'd just start playing anything we wanted to play. We had one rule: whoever's leading the song came back, go to the head, go to the top, then comes back to that main motif. So if we were doing a James Brown "I Feel Good" or something, we'd play the whole thing all the way through, then we'd go into our jam, then we'd come out. We were playing Bobby Blue Bland, Booker T and the MGs... there were so many different people that we'd emulate. I remember Old Man Jeffty, South Los Angeles - we thought we were just as hot as James Brown, because our band was tight, we were just kids - and he looked at us and he said, 'Let me ask you this question: if you were playing here and James Brown was down the street, who would they go see?' Well of course, James Brown. So that's when we started consciously trying to come up with our own sound, not trying to imitate somebody else.

It's probably still Jeffty's Lounge. We

were seeing all kinds of musicians. T Bone Walker would come through

there, Don and Dewey - I mean, we were just right in the middle of all

the blues. We had a chance to go up to the Five Four Ballroom, which was

up in Los Angeles, and that's when we could see, like, Rufus Thomas,

James Brown, Bobby Blue Bland, all kinds of people. But right at that

time, Carl, in those early years, like in the late '50s and early '60s

when we were coming up, they didn't have what they call a race station.

You'd listen to Texas Tiny, and he would be playing Johnny Cash as well

as Fats Domino. A little Willy Junior, Johnny Ace, or Johnny Otis. It

was all integrated at that time, so we were being bombarded with all

types of music. We'd hear Country and Western, we'd hear Latin music,

we'd hear Blues, we'd hear the early funk, the R&B, which was James

Brown and those guys.

So, anyway, right there about '62, '63, when we were able to start driving around, we just started playing in a lot of car clubs in the Bay area. They would have hotrods and stuff they were into, and they would like for us to play. So right about '64, we came out of high school. I had a full scholarship to Valparaiso University, but I turned it down in order to be a professional musician.

Our band was the first black band to be booked up on the Sunset Strip. They had just the Knickerbockers, which was the answer to The Beatles at the time. We're talking like roughly about '63-'64. Well, when we came out of school, I had gotten everybody, we went down to join the Musician's Union, Local 47, but the thing was they were working with Desilu Productions, you know, Lucille Ball. The next thing I knew he were booked at the Palladium and Whiskey A Go-Go. Then we hooked up with Bob Eubanks, and he had a bunch of clubs called the Cinnamon Cinders - there was a song out called (sings) 'See see, Cinnamon Cinders, I see see a Cinnamon Cinder.' We were opening for the O'Jays. We were kids of the National Guard Armories and stuff. I mean, it was like destined that we were gonna be who we are. Then, the Vietnam War was coming, it was about '66 or so. I had my own business, because I didn't want anybody telling me when I had to come to work and when I left, so I went into the body and fender auto detail business. So I always had transportation, and had money – cash flow. So then that way the band, we could go for auditions and stuff. But right about '66 we had an opportunity to go to play the Fremont Hotel in Las Vegas, and all of a sudden the guys started getting drafted. But just before that happened we were in El Paso, and that's when Johnny Cash was coming across the border and he got busted with amphetamines. We used to try to buy liquor and bring it back, and the border patrols would stop us and dump it in the Rio Grande. So there was Old Man Fulbright. I used to think he was a figment of our imagination, but since then I've read about him in various books, especially anything involving Clifton Cheniere. He came through there, and he heard us playing. He said, 'I've got a young man that you guys would be a great band for, and he's upstate in Memphis.' It was Otis Redding. We didn't take the gig because our keyboard player was too young at the time.

Songfacts: Too young to do what?

Harold:

To go out on the road. He was only 15. He hadn't even finished high

school. We were about 18, 19 years old. We had a few guys older than us.

But who knows? If we'd been with Otis Redding, maybe that plane

wouldn't have crashed. That's amazing, isn't it? So anyway, all of the

sudden, the guys started getting drafted. Oh boy, Bobby Nicholson, our

trumpet player, got drafted. The next thing I know Howard, him and I are

still playing music together, Howard got drafted into the army. Our

band started getting fragmented, so we kind of like bumped around,

myself, BB Dickerson, along with our keyboard player at that time.

Harold:

To go out on the road. He was only 15. He hadn't even finished high

school. We were about 18, 19 years old. We had a few guys older than us.

But who knows? If we'd been with Otis Redding, maybe that plane

wouldn't have crashed. That's amazing, isn't it? So anyway, all of the

sudden, the guys started getting drafted. Oh boy, Bobby Nicholson, our

trumpet player, got drafted. The next thing I know Howard, him and I are

still playing music together, Howard got drafted into the army. Our

band started getting fragmented, so we kind of like bumped around,

myself, BB Dickerson, along with our keyboard player at that time.

Songfacts: How come you didn't get drafted?

Harold: Well, because I was in business for myself. So they wouldn't take me. Because nobody would run my business.

Songfacts: So if you owned your own business you didn't get drafted?

Harold: Right. That was one of the exemptions. So then when things started falling apart, my business started going down, I wound up in a class in machining. I'm the one that helped show Lee (Oskar) how to design his harmonica, got him started, because I was a Class A machinist. I was doing projects for, you know, like when they're shooting the monkeys into outer space, then they had me making bomb parts for the effort over in Vietnam.

Songfacts: That's kind of ironic. So you actually made bombs?

Harold: They would send you around different parts, different machine shops.

Songfacts: Who's "they"? Is this your training?

Harold: The government contract. Government contracts the different machine shops would get. So you would wind up making one piece of this part, another guy over in some other place is making a piece of this part, then we'd all come together, they'd put it together. Like, we were doing parts for oil drilling. I would be doing the cones, where somebody else would be doing the pipes. Just like module building.

When Kennedy came back they escalated it to even guys that were married, which, I hate to say it, I think we're repeating history. That's another story. But they wouldn't bother me because I was a machinist, I was doing government work.

So we were doing all this playing, trying to keep things together. About 1967 or so, Howard came back out of the military, he was getting ready to take a job down at the Harbor General Hospital in the South Bay area outside of Los Angeles towards San Pedro. At that time they were offering him something like $6.45 an hour. See, as a machinist I was making $400-500 a week in the '60s, and I said, 'Howard, let's try it one more time, and if we don't succeed, we'll go about our own business.' Oh boy, we did it, we went at it. It looked like we were about to not make it - I was going behind on my house note, they were getting ready to kick me out, I had three kids, and stuff - and I went looking for a job. This is how fate works. So then, I go up to North Hollywood, Thousand Oaks, and I've seen this ad for a job at some major chain company. When I got up there, they looked at me and said, 'You're in the wrong place. You go down to Los Angeles.' That's where Affirmative Action can work both ways. In my case, Affirmative Action did me a favor: They just looked at me and said, 'You're chocolate, you need to go down there.' So I'm on my way down, Carl – this is the truth. I'm driving, all of the sudden I had to take a wee-wee, and I said, 'I'm just coming to Sunset.' Well, all through those years when I had my body and fender shop, I had a good friend at that time Marshall Lieb. Marshall Lieb was a producer. He produced 'What the world needs now is love, sweet love.' Jackie Deshannon. And also 'Last Night.' He was producing those songs. Well, when I had my body and fender shop and detail, he had Ferraris, and he only trusted me to take care of his Ferrari, because they were show cars out at Disneyland. So I'm coming down – this was about 1967, and I said, 'Let me see where Marshall's at.' Because he was working at United Artists Records, which was Liberty Records at the time, right across the street from Hollywood High on Sunset Boulevard. So I go in there, and I'm looking for Marshall. Remember, I only had about seven dollars on me. They were getting ready to kick me out of the house, I had to buy gas, got my kids at home, don't know my next move. So I go in and I asked the secretary, 'Is Marshall Lieb here?' She says, 'No, he's not here.' My heart dropped. She said, 'But I can tell you where he's at.' So I started driving on down to Jim Head Productions, which was in the 9000 building, which is on Sunset, and it's on the left-hand side just before you go into Beverly Hills, over across from the Rainbow, up in the Whiskey A Go-Go area. I get up there and there's a lady sitting behind the desk. I said to her, 'I'm trying to locate Marshall Lieb.' And she says, 'He's not here.' And my heart dropped again. But she stood and she said, 'You see out the window, over there across the street? The little white house? He's in there.' So I go across the street, I see all these gold records and stuff and everything. I walked in, there's Marshall Lieb on one side of the desk, and he looks at me, and he says, 'Harold, this is Sonny Bono. Sonny, this is Harold Brown.' He said, 'Hello, what are you doing?' I said, 'I'm not doing anything.' He said, 'Wait for me,' so I go outside and I sat down. Finally the meeting was over, and Marshall says, 'Come on and go with me to the studio.' He started asking questions... all of the sudden the phone rings: 'Yeah, Timi. Oh, Timi, you need a drummer? Oh, you got a big gig? Oh, I got one of the best drummers in the city. I'll send him to you.' I was probably eating a dollar burrito, probably at that time gas was 25 cents, so I had put about a full gallon, so I drive back towards Beverly Hills and she was right on King's Road. It was Timi Yuro, the famous Jazz singer. There's this band, and these guys are telling her, "We need cars, we need amplifiers, we need this and everything." Well, I was varsity captain of our track and cross country team 4 years straight, I was one of the top distance runners in the state of California, I was in the Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts, everything, I was a quartermaster, I was gonna be prepared. So I'm sitting there and I'm listening to these guys giving all these problems. So I say to myself, "I'm not gonna say anything, I'm gonna go back, tell Marshall Lieb to call Timi Yuro, fire all those guys, I got a band, we got cars, we got instruments, ain't no problem." Well, I go back and I get there and there's a guy sitting there on the stoop, and he says, "They always take my band." It was Sonny Charles, R&B great. He was just a little guy. I looked at him and said, 'Man, you mean you got gigs? I got a band." Oh, my heart started jumping, he had a gig coming right up. I ran back out of that studio door – we're right there on Sunset, there was a gas station, there was a telephone booth next to the hotdog stand. I called up Howard, I said, "Howard, our luck is about to change. You call everybody else and tell them to get ready for rehearsal tomorrow, and we're gonna roll." The next day I get with Sonny Charles. We had like a 13-14 piece group. I got the guys, we named the group the Night Shift because I was working in the steel yard at night. The singers with us, they wound up singing with Dr. John on that Night Tripper. That's when I got Deacon Jones, the football player, for part of the revue, and Roman Gabriel... that was the skinny, wiry guy that was an athlete. I would sit there, and they would like to be in front of their girlfriends, they'd take off their shirts. I remember old Deacon Jones looking at me saying he'd like for me to punch him in his chest, and he just started laughing. And then I looked at him and I said, 'If I ever have to whoop your ass, I know how to do it. I'm just gonna pick up a mike stand and hit you with it.' And then we can get a chuckle out of it, you know.

So, anyway, right there about '62, '63, when we were able to start driving around, we just started playing in a lot of car clubs in the Bay area. They would have hotrods and stuff they were into, and they would like for us to play. So right about '64, we came out of high school. I had a full scholarship to Valparaiso University, but I turned it down in order to be a professional musician.

Our band was the first black band to be booked up on the Sunset Strip. They had just the Knickerbockers, which was the answer to The Beatles at the time. We're talking like roughly about '63-'64. Well, when we came out of school, I had gotten everybody, we went down to join the Musician's Union, Local 47, but the thing was they were working with Desilu Productions, you know, Lucille Ball. The next thing I knew he were booked at the Palladium and Whiskey A Go-Go. Then we hooked up with Bob Eubanks, and he had a bunch of clubs called the Cinnamon Cinders - there was a song out called (sings) 'See see, Cinnamon Cinders, I see see a Cinnamon Cinder.' We were opening for the O'Jays. We were kids of the National Guard Armories and stuff. I mean, it was like destined that we were gonna be who we are. Then, the Vietnam War was coming, it was about '66 or so. I had my own business, because I didn't want anybody telling me when I had to come to work and when I left, so I went into the body and fender auto detail business. So I always had transportation, and had money – cash flow. So then that way the band, we could go for auditions and stuff. But right about '66 we had an opportunity to go to play the Fremont Hotel in Las Vegas, and all of a sudden the guys started getting drafted. But just before that happened we were in El Paso, and that's when Johnny Cash was coming across the border and he got busted with amphetamines. We used to try to buy liquor and bring it back, and the border patrols would stop us and dump it in the Rio Grande. So there was Old Man Fulbright. I used to think he was a figment of our imagination, but since then I've read about him in various books, especially anything involving Clifton Cheniere. He came through there, and he heard us playing. He said, 'I've got a young man that you guys would be a great band for, and he's upstate in Memphis.' It was Otis Redding. We didn't take the gig because our keyboard player was too young at the time.

Songfacts: Too young to do what?

Songfacts: How come you didn't get drafted?

Harold: Well, because I was in business for myself. So they wouldn't take me. Because nobody would run my business.

Songfacts: So if you owned your own business you didn't get drafted?

Harold: Right. That was one of the exemptions. So then when things started falling apart, my business started going down, I wound up in a class in machining. I'm the one that helped show Lee (Oskar) how to design his harmonica, got him started, because I was a Class A machinist. I was doing projects for, you know, like when they're shooting the monkeys into outer space, then they had me making bomb parts for the effort over in Vietnam.

Songfacts: That's kind of ironic. So you actually made bombs?

Harold: They would send you around different parts, different machine shops.

Songfacts: Who's "they"? Is this your training?

Harold: The government contract. Government contracts the different machine shops would get. So you would wind up making one piece of this part, another guy over in some other place is making a piece of this part, then we'd all come together, they'd put it together. Like, we were doing parts for oil drilling. I would be doing the cones, where somebody else would be doing the pipes. Just like module building.

When Kennedy came back they escalated it to even guys that were married, which, I hate to say it, I think we're repeating history. That's another story. But they wouldn't bother me because I was a machinist, I was doing government work.

So we were doing all this playing, trying to keep things together. About 1967 or so, Howard came back out of the military, he was getting ready to take a job down at the Harbor General Hospital in the South Bay area outside of Los Angeles towards San Pedro. At that time they were offering him something like $6.45 an hour. See, as a machinist I was making $400-500 a week in the '60s, and I said, 'Howard, let's try it one more time, and if we don't succeed, we'll go about our own business.' Oh boy, we did it, we went at it. It looked like we were about to not make it - I was going behind on my house note, they were getting ready to kick me out, I had three kids, and stuff - and I went looking for a job. This is how fate works. So then, I go up to North Hollywood, Thousand Oaks, and I've seen this ad for a job at some major chain company. When I got up there, they looked at me and said, 'You're in the wrong place. You go down to Los Angeles.' That's where Affirmative Action can work both ways. In my case, Affirmative Action did me a favor: They just looked at me and said, 'You're chocolate, you need to go down there.' So I'm on my way down, Carl – this is the truth. I'm driving, all of the sudden I had to take a wee-wee, and I said, 'I'm just coming to Sunset.' Well, all through those years when I had my body and fender shop, I had a good friend at that time Marshall Lieb. Marshall Lieb was a producer. He produced 'What the world needs now is love, sweet love.' Jackie Deshannon. And also 'Last Night.' He was producing those songs. Well, when I had my body and fender shop and detail, he had Ferraris, and he only trusted me to take care of his Ferrari, because they were show cars out at Disneyland. So I'm coming down – this was about 1967, and I said, 'Let me see where Marshall's at.' Because he was working at United Artists Records, which was Liberty Records at the time, right across the street from Hollywood High on Sunset Boulevard. So I go in there, and I'm looking for Marshall. Remember, I only had about seven dollars on me. They were getting ready to kick me out of the house, I had to buy gas, got my kids at home, don't know my next move. So I go in and I asked the secretary, 'Is Marshall Lieb here?' She says, 'No, he's not here.' My heart dropped. She said, 'But I can tell you where he's at.' So I started driving on down to Jim Head Productions, which was in the 9000 building, which is on Sunset, and it's on the left-hand side just before you go into Beverly Hills, over across from the Rainbow, up in the Whiskey A Go-Go area. I get up there and there's a lady sitting behind the desk. I said to her, 'I'm trying to locate Marshall Lieb.' And she says, 'He's not here.' And my heart dropped again. But she stood and she said, 'You see out the window, over there across the street? The little white house? He's in there.' So I go across the street, I see all these gold records and stuff and everything. I walked in, there's Marshall Lieb on one side of the desk, and he looks at me, and he says, 'Harold, this is Sonny Bono. Sonny, this is Harold Brown.' He said, 'Hello, what are you doing?' I said, 'I'm not doing anything.' He said, 'Wait for me,' so I go outside and I sat down. Finally the meeting was over, and Marshall says, 'Come on and go with me to the studio.' He started asking questions... all of the sudden the phone rings: 'Yeah, Timi. Oh, Timi, you need a drummer? Oh, you got a big gig? Oh, I got one of the best drummers in the city. I'll send him to you.' I was probably eating a dollar burrito, probably at that time gas was 25 cents, so I had put about a full gallon, so I drive back towards Beverly Hills and she was right on King's Road. It was Timi Yuro, the famous Jazz singer. There's this band, and these guys are telling her, "We need cars, we need amplifiers, we need this and everything." Well, I was varsity captain of our track and cross country team 4 years straight, I was one of the top distance runners in the state of California, I was in the Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts, everything, I was a quartermaster, I was gonna be prepared. So I'm sitting there and I'm listening to these guys giving all these problems. So I say to myself, "I'm not gonna say anything, I'm gonna go back, tell Marshall Lieb to call Timi Yuro, fire all those guys, I got a band, we got cars, we got instruments, ain't no problem." Well, I go back and I get there and there's a guy sitting there on the stoop, and he says, "They always take my band." It was Sonny Charles, R&B great. He was just a little guy. I looked at him and said, 'Man, you mean you got gigs? I got a band." Oh, my heart started jumping, he had a gig coming right up. I ran back out of that studio door – we're right there on Sunset, there was a gas station, there was a telephone booth next to the hotdog stand. I called up Howard, I said, "Howard, our luck is about to change. You call everybody else and tell them to get ready for rehearsal tomorrow, and we're gonna roll." The next day I get with Sonny Charles. We had like a 13-14 piece group. I got the guys, we named the group the Night Shift because I was working in the steel yard at night. The singers with us, they wound up singing with Dr. John on that Night Tripper. That's when I got Deacon Jones, the football player, for part of the revue, and Roman Gabriel... that was the skinny, wiry guy that was an athlete. I would sit there, and they would like to be in front of their girlfriends, they'd take off their shirts. I remember old Deacon Jones looking at me saying he'd like for me to punch him in his chest, and he just started laughing. And then I looked at him and I said, 'If I ever have to whoop your ass, I know how to do it. I'm just gonna pick up a mike stand and hit you with it.' And then we can get a chuckle out of it, you know.

I

like exemplary people around me, I don't judge you by your name, your

color, or your money. I judge you by whether or not you're an exemplary

person. Because if I know you're an exemplary person, and I want you to

move this equipment from here to there, or you're building a house or

you're shining shoes or stuff, then I know you're gonna do it the best

you know how. That's the bottom line. See, that's where people keep

falling off of America here, because we get inferior people in positions

they have no business being in. I don't want a guy working on my heart,

and he's a mechanic. Well, we were at the Rag Doll in North Hollywood,

and Jerry Goldstein, who later on wound up being our producer - he

always liked to put up he found us in a topless bar, and flat out,

that's a lie. We were not in no topless bars, they'd be watching the

women more than they would us - but The Rag Doll was North Hollywood,

and the owner of the club – I'll never forget – he took me to the back

and he showed me all these gold records, gold albums and stuff. The

Spiral Staircase, they played there. Deep Purple played there. And he

looked at me, he says, 'Harold, everybody that's ever played in this

place winds up being famous.' I think that this was the night Deacon

Jones didn't come back. Hindsight, Deacon didn't show up that night

because he didn't have the heart to tell us that was our last night

there. But ironically, my bass player that I had was Peter Rosen at the

time. He was out of New York City, he's since then died. But Peter Rosen

kept telling me, 'I got a good friend, his name is Eric Burdon, and

he's gonna come and watch us one night.' And then I had another guy,

Jaye Contrelli, he used to play with the group Love. It just so happened

this was our last night, and he says to me, 'Eric is coming.' So the

word started going around the house, 'Eric is here. Eric Burdon is

here.' I'm sitting up there behind the drums, and I see this wiry guy...

now, all the time when I working in machine shops and stuff and

drilling all them – making all them parts, I was hearing this song, Sky

Pilot. I'd just hear it over and over and over. I didn't really know

what Eric looked like, but I seen this wiry, thin guy coming up with

this huge afro, and I said, 'Oh, that must be Eric.' Well, he had a

harmonica - key of C or something of that nature, and he wanted to jam

with us. Well, we're still jamming to this day. So he comes up and I'm

thinking that was him, but then we started going into this Blues. The

next thing I knew we went from a blues, and what was interesting –

because we were the Creators we knew how to jam, we would go into all

types of modes. We would start off with a shuffle, then we'd got to a

6/8, all kinds of different rhythms. It went on for about 30 minutes. We

just played straight through. When we finished, everybody was standing

on top of the tables, clapping and cheering, they were going crazy. So I

go in the back, and you know how brothers are, we got in the back, we

start giving five – 'Hey, man, we kick.' Some guy walked in, and one of

the waiters or somebody, says, 'There's a gentleman here would like to

meet you.' That's the first time we got a chance to meet Steve Gold. He

says, 'You guys are great. Maybe we can get together. Let's meet.' Well,

that was on a Saturday, probably February of 1969. The next day we went

up to Benedict Canyon, which was out up above Beverly Hills, Hollywood.

Songfacts: Just so I'm clear on this – Eric Burdon was not in the club that night?

Harold: He was there. We didn't get a chance to meet him.

Songfacts: Okay, but Lee went up… when did you realize it was Lee and not Eric Burdon?

Harold: I think I kind of realized it after he didn't sing. All he did was play.

Songfacts: All right. So Eric Burdon's in the club that night, but you don't meet him that night.

Harold: Yeah, we don't meet him. So that next day, we go to Benedict Canyon. Well, it was up in the hills, you know, Bohemian type thing. A wooded area. And we got up and we opened up the door, and the first thing I see is the secretary, I think her name was Lois or something, came up and she had one of them Hollywood black bikinis. Whoa. So we go in, and the first time I met Eric, I went out to the swimming pool, and there he was laying reclined on the swimming pool with this black swimsuit on and Ray-Bans. It was all pictured out, you know, you be over here when they come and you be over there. So I go out and the first thing he started with me, he said something about how he got beat out of a million dollars. I said, 'How could somebody do that?' Well, guess what, in the music business that can happen. Duh. But we didn't know, so he started talking to me and we got to knowing each other. The guys that were there were Eric Burdon, Lee Oskar, Howard Scott, Charles Miller, Papa Dee Allen, Steve Gold, Jerry Goldstein, Lonnie Jordan, and then there might have been some peripheral people. That was on a Sunday. The next day, we had the meeting. That's when things started happening. We sat there, Steve Gold, which wound up being a very good friend to the band later, was really instrumental in a lot of things happening for us.

I gotta say something about Steve Gold. He's been demonized, he's been Stalinized, it's hard to write him away out of history. But Steve Gold was a real record man. You don't find record men. They're sort of like that thing that they did years ago, that movie with Neil Diamond, how they built and made him a star? He was that way. He was rounded. He knew when the music sounded right, he knew when the magic was there. Like he always told me, there's a whole lot of talent out there, but there's very few people that know what to do with it. He could come up with things like the 99 cent concert at the Hollywood Bowl. The Creedence Clearwater, and I mean, so many different people. That's when Richard Pryor was there. He was so brilliant that he would go and buy billboard ads, and he would buy the back cover upside down and make it look like it was the front cover and put an ad on there for us. That kind of stuff.

So Steve Gold was sitting there, and he started saying, 'We're going to take Eric, and we're going to build on top of him.' He used the analogy of the Sputnik, how Eric was going to be the missile to take us out, and then we were going to be released from there and launched like the Sputnik. Now, this is where Lee and everybody come up with different things. I was straight, I was not into drugs, so I know my mind is real clear. I don't know what everybody else is doing, I can't speak for them. Steve got all red in the face, snot started coming out of his nose, he says, "You guys are really a motley crew. I've got a great idea, let's just call you War." And then Lee says that before that him and Eric was riding along, they see a billboard with Yoko Ono and they were talking peace - the direct opposite with the War, but the way I remember it, Steve Gold sat there and said, 'We're gonna name you War.' That's when we started going in the studio. It was unique then, because they didn't ask us to sign any kind of agreements or any contracts. Steve wanted first to see what we could do, so for about a year we just kept going in and out of studios. And then one day we were up in San Francisco, just playing and stuff. Lonnie came in acting all drunk and stuff and out. They had a bottle of wine, and some of that wine got spilled over in the console. Lee says he felt that the song didn't have anything to do with the wine going into the console, but all I know is after that they moved out of the A studio, they moved us into the B studio, and then we were playing a Latin thing, and even if Eric had been writing 'Spill The Wine' all along, and writing the concepts, that's when it all came together. That's when we went into the studio, we started playing it, Eric was putting stuff together, and all of the sudden there came our first hit, 'Spill The Wine.' It was different. It was '69 or so, that's when Jimi Hendrix would hang out with us a lot, right during that time period. It was the Chateau Marmont, located above Sunset. The hotel is still there, and in that day, they had a series of bungalows back there. At that time, Steve Gold and the company they were putting together, they had gotten a bungalow, and that was where everybody would kind of meet.

Songfacts: So are you guys playing at the same time you're recording?

Harold: Yeah, we were playing. The first gig that we played was June 6th and 7th, 1969, at Mother Liz's in San Bernardino, California. At the Chateau Marmont, after we played and stuff, it wasn't uncommon for Jimi Hendrix to be up there just sitting there with us. Him and a couple of ladies. We weren't doing drugs and stuff. They were eating a lot of pizza and drinking cokes. He used to like to sit around us because we would just start jams. Somebody would get on the piano and started playing, we'd get some pots or something out of the kitchen, be playing on it, and we'd be playing music. They would be sitting up there digging on it. I remember some of the most fun things about Jimi, we'd go to Europe, and in London, we were walking through an alley, and Jimi was in front of me, and he looked... I said, 'Jimi, where are you taking me?' And he looked back over his left shoulder at me with his floppy hat and his crushed velvet jacket, and says, 'Brown, I'm gonna show you how to eat when you come to Europe.' His favorite food was chicken tandori, and chutney and rice. The last memory I have of him is when we were all sitting up with Eric. It was in Munich, Germany. We were sitting up there and we were all eating together, sitting around a table and stuff. They had a game, he liked to pass the tequila around, and whoever would get the worm, they were the winner. Well, I would chicken out after about maybe 2 or 3 hits, but everybody else... I'd see people dropping under the table and stuff. So I think Eric is the one that got the worm, if I remember, that night. So then, Eva Maria, she comes in. Eva Maria is the woman that Jim Brown tossed over the side of the balcony years back. She heard there was a Brown, she came up there, I looked at her, 'Oh, that wasn't him.' She left. I found that was the same woman. Then after that we got on a cruise. We took a train, and we were gonna catch a ferry and go over to London. Coming down that Rhine River, we were all sitting there, Jimi started calling, naming to me all the different castles along the Rhine River. We went and we got on this ferry, we came across, then the last time I actually remember him, and hearing him talking to me, was when we were there at Ronnie Scott's, they were doing a jam that night. If I remember, I think Paul McCartney was there, and Morrison was there. We got off the stage, and then he wanted to jam a little bit. He was standing right behind me, and I remember looking to my right, seeing his fingers moving, and then him talking in my left ear. Because he liked that... one of them loping-type shuffles. And he said, "Yeah, Brown, right there, right there. Right there."

Songfacts: And this is Jimi saying this to you.

Harold: This is Jimi saying this to me. So that night we finished playing, and I had some friends there and they invited me to stay with them at some penthouse somewhere in London. The next day, that's when I got the call from Eric that Jimi had made his transition.

Songfacts: Oh, my God.

Harold: We were all tripped out, sad. Steve Gold was down, because Steve is the one that really introduced us to Jimi, because he was traveling around Europe filming Jimi. They'd been really good friends, and they'd hang out together a lot. So we come on back and we went through that transition of that part of history. And it taught some of us some valuable lessons at that time, too. You've just got to be careful. Gotta know when to hold, when to fold. We'd have parties with Morrison from the Doors. Sly Stone. We were all hanging together during that time period.

So anyway, so we got back in the studio, we started recording with Eric. We came up with a couple of more songs, couple of albums. 'Love Is All Around,' 'Black Man's Burdon,' which was on MGM. Now, 'Black Man's Burdon,' Mike Curb was the president at the time, and he wanted to be a lieutenant governor for California at one point. But he had it in for Eric and Steve Gold and different companies, because he thought he was getting us, too. And some kind of hook or crook, that 'Black Man's Burdon' never really got distributed in the United States. It was put up on the shelf to get back at some of the guys against the business deal. We go forward, and finally we were in Europe touring with Eric. Now see, Eric and I know exactly what happened, why he left the group. Because he came to my room, because him and I had an unusual kind of relationship. Years before that we were out somewhere, and I'm walking around and I come back in and Eric is all mad at the band, I guess because of a bad show or something. He started poking me in my chest and I pushed him back and I said, 'No. I don't work for you, I work with you.' After that he started giving me Porsches and stuff. He'd come by New Orleans and see me. So he came to the room, he was burned out. He'd been traveling all that time, he'd just gotten married... he was just burned out. I looked at him and I said, 'Eric, you know what? We can handle the show. If you want to go back, I say go back.' So that's when he left us there in Northern England. That's when we became our own. We started playing songs that we had on our first album War that went vinyl. That's our joke - it never made platinum or gold, it went vinyl. We had enough of our own new material, and old songs that we'd been playing before we met Eric, so we just started playing them. Our first big hit that we got for our group, we were touring in Europe. We all help write, but Howard Scott was a primary writer. Papa Dee would be in there. Charles Miller, my partner, he was like my big brother, him and I grew up together, he was two doors down from me, he's actually the one that sang "Low Rider." But he had an early… some… well, he got murdered. I don't know… it was pretty sad. But at that time we had all those writers.

Harold: He can play. He puts on a certain act. His mama's a concert pianist.

Songfacts: Jim Morrison, so he actually had musical skills?

Harold: Oh yeah, Jim Morrison was a musician. He wasn't just a rock star. He was really a musician. And then he'd get drunk, I'd look over, he'd be curled up asleep knocked out in his Superman outfit or something. He just didn't know when to back off. Janis Joplin, same thing.

Songfacts: Because you had mentioned you were never too into the whole drinking and drugs kind of thing.

Harold: No, you know, we had our different time periods where, you know, you did certain things, and there's certain things I knew were just taboo. And you know, one point where they got into the cocaine. I got liberated, and I didn't have to go to a funny farm, go and get dried out. I just knew: one day I woke up, I said, 'Wait a minute.' First of all, I don't like the way it made me feel. Because I'm an extrovert, and I go out and I talk to people. When I do that drug it makes me an introvert, and I feel like I'm canned up inside, I don't like that feeling. And then the friends and stuff that were coming around, they would want to be working with me on a project and do a lot of blow and stuff, and then they still want you to pay them. So I don't like the people around it.

Songfacts: So this whole scene, is it like at night you're at somebody's house, you're at a club…

Harold: Oh yeah, we used to have house parties. The one that I remember the most was having a birthday party for Eric, and it was at Boris Karloff's old house. And I remember, boy, it was crazy, guys would come over, be throwing kegs and stuff in the swimming pools. They'd come flying through there. Shoot a .357 up in the air.

Songfacts: And there really were drugs just flying all over the place?

Harold: During that time period, it would be around, it was acceptable. It was just the thing.

I left the group when I was about 37. I was just burned out, I think I hit that same point that Eric did when he left. And there were business things going on with the different record company, I could see certain writing on the wall. So I just kind of backed off, and for a long time, Carl, I thought I'd made a mistake. But later on when I got to be 50, the spirit came to me and said, 'No, there was no mistake.' Because 1) I would have never taken the opportunity to go to college. I would never have been who I am now. I wouldn't have grown, I've grown spiritually, I've grow as far as academic structure, computers, music – I went back and I learned how to play. I didn't start playing piano 'til I was 40. I wouldn't hire me as a piano player, but I can tell you everything on the paper, and I can write. In these past 3 years I went back and I studied architecture, geology, history. People get on this euphoria of drugs. Because, let's say you go and play to 10,000 people, 5,000, 50,000, or even 10 people. Well, you get up there, and the adrenaline, when you reach a certain point playing and communicating musically, and everybody's synched in, that's a helluva high. That's something you can't manufacture or buy. So what happens is being a musician or being an artist, that adulation, you want to try to obtain that, and then you start finding synthetic things to get you there, to that high. That was happening with Jimi and those guys: 'Oh you're the greatest, you're the greatest.' But then, I got lucky. I started achieving certain things, like get a whole new War. Get two of them. Or take in a great golf game. Or creative writing a nice piece of music, going through and achieving computer science or mastering or learning this. And then I can go back, like I'm getting a buzz when I talk to you about these things. So I replaced it. What happens to a lot of people that wind up strung out on drugs is they don't have something else they've got to replace it with. You can't just say, 'Just say no,' you've got to give them something else in place of that.

Songfacts: All right. Now, when you're talking about how Jimi… could he be stone sober throughout the day and on stage, and then it was after hours that he would get into the drugs?

Harold: I would say that would be a thing like that. You know, some people were doing cocaine and stuff, they'd be buzzed up, so then they would try to take another pill to bring them down. And so you never know where they're at.

Songfacts: So these musicians who were on drugs, they could be under the influence at just about any time, including when they're on stage?

Harold: You can, yeah. And see, I've been so far away that sometimes people tell me people are on stuff, I can't even recognize them.

Songfacts: All right. I just wanted to go back a little. Could we talk a little about "Spill The Wine"?

Harold: Sure.

Songfacts: Is Eric responsible for the lyrics?

Harold: Yes, Eric was responsible for the lyrics, but there was a glitch. If he had written the lyrics, MGM, they would have been entitled to a deal that he had made. They would have been able to administrate it, and it would have just gotten nasty for him. So we did the music and then he just gave us all the lyrics. Which, one day, you know, like Lee was saying, we just like to give it back to him. Because we've got enough of our own songs now.

Songfacts: On that song, there's the lady speaking Spanish in the background. What's all that about?

Harold: It was Eric's girlfriend. We went back there and we put up a little tent-like, candlelight, and some wine back there, and they were behind there, and Eric was doing things to her and making her talk. So we recorded the song.

Songfacts: So the whole "Spill The Wine" concept, is there a deeper meaning? Is there anything besides just, hey, somebody spilled some wine on the console, sounds like a good lyric?

Harold: I think that Eric was already working on an idea about leaking gnomes, waking up in a grassy field, and then when the wine inadvertently got knocked over, whether it was part of the song or not, it all just came together right at that moment.

Songfacts: And is he saying, "Dig that girl?"

Harold: "Spill the wine, take that girl. Spill the wind, take that pearl."

Songfacts: Okay, so it's "girl" and then it's "pearl."

Harold: Yeah. And then you know what the pearl is, you know, all the little maidens are trying to save their pearl anyway for their future loves.

Songfacts: Oh, you're going to need to explain that to me. What's the pearl?

Harold: The pearl, you know, the jewel, the jewel. The pearl is their…

Songfacts: Oh.

Harold: Their nut.

Songfacts: So that's a sexual reference, that pearl.

Harold: Yeah, right.

Songfacts: What else is in there that we don't know?

Harold: Oooo… all ladies are beautiful. You've got to look at them... it's just like, when you put someone in a field of grass and tall ones, short ones. God, I believe, put all of us here and made us all different so we could be like the flowers, you know. Like women. I look at them as beautiful flowers. Even when they get older, the flowers and so on, and that's what it really boils down to, they can be skinny, big, fat, I've seen some fine voluptuous women. And then I've seen some that are skinny, and if you look at them, they could be beautiful, depending on personality and stuff.

Songfacts: Just so I'm clear on this – Eric Burdon was not in the club that night?

Harold: He was there. We didn't get a chance to meet him.

Songfacts: Okay, but Lee went up… when did you realize it was Lee and not Eric Burdon?

Harold: I think I kind of realized it after he didn't sing. All he did was play.

Songfacts: All right. So Eric Burdon's in the club that night, but you don't meet him that night.