SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2020

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER TWO

HERBIE HANCOCK

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

GIGI GRYCE

(May 16-22)

CLARK TERRY

(May 23-29)

BRANFORD MARSALIS

(May 30-June 5)

ART FARMER

(June 6-12)

FATS NAVARRO

(June 13-19)

BILLY HIGGINS

(June 20-26)

HANK MOBLEY

(June 27-July 3)

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

(July 4-10)

INDIA.ARIE

(July 11-17)

JOHN CLAYTON

(July 18-24)

MARCUS MILLER

(July 25-31)

JAMES P. JOHNSON

(August 1-7)

Gigi Gryce

(1925-1983)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Gigi Gryce

was a fine altoist in the 1950s, but it was his writing skills

(including composing the standard "Minority") that were considered most

notable. After growing up in Hartford, CT, and studying at the Boston

Conservatory and in Paris, Gryce worked in New York with Max Roach, Tadd Dameron, and Clifford Brown. He toured Europe in 1953 with Lionel Hampton and led several sessions in France. After freelancing in 1954 (including recording with Thelonious Monk), Gryce worked with Oscar Pettiford's groups (1955-1957) and led the Jazz Lab Quintet (1955-1958), a band featuring Donald Byrd. He had a quintet with Richard Williams during 1959-1961, but then stopped playing altogether to become a teacher. During his short career, Gigi Gryce

recorded as a leader for Vogue (many of the releases have been issued

domestically on Prestige), Savoy, Metrojazz, New Jazz, and Mercury.

https://attictoys.com/gigi-gryce-basheer-qusim/

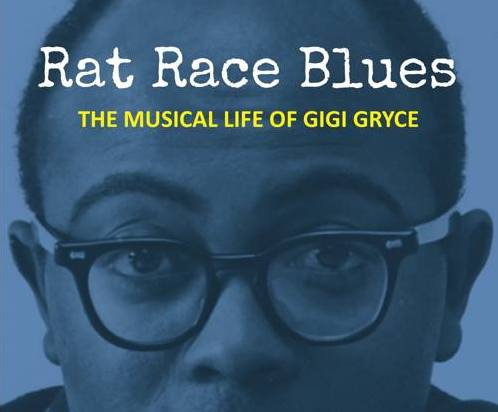

The saxophonist, arranger and composer Gigi Gryce (1925-1983) is another figure of the 1950s whose contributions are overlooked and worthy of reinvestigation. To this end, Michael Fitzgerald and I initiated in 1997 a substantial research project aimed at clearing up many of the misconceptions which surround the mysterious Gryce (known by his Muslim name, Basheer Qusim in his later years as an educator) and resurrecting his music. Over 70 interviews were conducted with musicians, relatives and observers of the music scene during the relatively short period that he was active. Our efforts culminated in the 2002 publication of “Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce” (Berkeley Hills Books, Berkeley, CA). This award winning biography, for the first time, tells the true story of this often overlooked figure and illuminates his contributions to one of the richest periods in jazz history. Included are a foreword by Benny Golson, and over 30 photographs.

The updated second edition of “Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce” is now available (October 2014). For the Gigi Gryce Discography and other important information associated with the book, see the Gigi Gryce pages menu above.

While known mainly for his consummate writing skills, Gryce was also an original although largely unrecognized player whose solos manifested great lyricism and structure. His style was clearly influenced by Charlie Parker but his tone and conception were unique when viewed within the context of the many fine alto saxophonists of his day.

Gryce’s best known composition is “Minority” which has been frequently recorded. Many of his other works such as “Nica’s Tempo,” “Up in Quincy’s Room” and “Shabozz,” written in the early 1950s, exhibit unusual forms and harmonic structures and presage later developments in jazz composition. “Social Call,” with lyrics by Jon Hendricks, has been performed by many singers including the late Betty Carter. Gryce’s catalog is published by Second Floor Music from which source lead sheets of several of his compositions can be downloaded.

A CD of previously unissued Gigi Gryce performances, Doin’ the Gigi, has been issued by Uptown Records.

A CD of Gigi Gryce music by the Chris Byars Quintet, Blue Lights: The Music of Gigi Gryce, has been issued by Steeplechase Records and available for purchase here.

Gigi Gryce was born George General Grice(sic) on 28th November, 1925 (not 1927) in Pensacola, Florida - although he was brought up in Hartford, Connecticut. He spent a short period in the Navy where he met musicians such as Clark Terry, Jimmy Nottingham and Willie Smith, who were to turn his thoughts from pursuing medicine to the possibility of making music for a living. In 1948 he began studying classical composition at the Boston Conservatory under Daniel Pinkham and Alan Hovhaness. It has been reported that he won a Fulbright scholarship and went to Paris to study under Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger, although confirmation of this has been hard to establish. Although illness interrupted his studies abroad, the fruits of this immersion in classical modernism were the production of three symphonies, a ballet (The Dance of the Green Witches), a symphonic tone-poem (Gashiya-The Overwhelming Event) and chamber works, including various fugues and sonatas, piano works for two and four hands, and string quartets.

Gryce strictly separated his classical composing from his work in jazz and received inspiration and instruction from a number of 'unsung' jazz saxophonists. The first of these was alto player Ray Shep, also from Pensacola, who had played with Noble Sissle. Then there were three musicians Gryce had met whilst based in the Navy in North Carolina. Altoists, Andrew 'Goon' Gardner, who played with the Earl Hines Band and Harry Curtis, who performed with Cab Calloway, as did tenorman Julius Pogue, for whom Gryce reserved the highest accolade. As well as alto saxophone Gryce performed on tenor and baritone saxes, clarinet, flute and piccolo - a 1958 recording for the Metrojazz label saw him multitracking all these instruments over a conventionally- recorded rhythm section.

https://attictoys.com/gigi-gryce-basheer-qusim/

Gigi Gryce (Basheer Qusim)

The saxophonist, arranger and composer Gigi Gryce (1925-1983) is another figure of the 1950s whose contributions are overlooked and worthy of reinvestigation. To this end, Michael Fitzgerald and I initiated in 1997 a substantial research project aimed at clearing up many of the misconceptions which surround the mysterious Gryce (known by his Muslim name, Basheer Qusim in his later years as an educator) and resurrecting his music. Over 70 interviews were conducted with musicians, relatives and observers of the music scene during the relatively short period that he was active. Our efforts culminated in the 2002 publication of “Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce” (Berkeley Hills Books, Berkeley, CA). This award winning biography, for the first time, tells the true story of this often overlooked figure and illuminates his contributions to one of the richest periods in jazz history. Included are a foreword by Benny Golson, and over 30 photographs.

The updated second edition of “Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce” is now available (October 2014). For the Gigi Gryce Discography and other important information associated with the book, see the Gigi Gryce pages menu above.

While known mainly for his consummate writing skills, Gryce was also an original although largely unrecognized player whose solos manifested great lyricism and structure. His style was clearly influenced by Charlie Parker but his tone and conception were unique when viewed within the context of the many fine alto saxophonists of his day.

Gryce’s best known composition is “Minority” which has been frequently recorded. Many of his other works such as “Nica’s Tempo,” “Up in Quincy’s Room” and “Shabozz,” written in the early 1950s, exhibit unusual forms and harmonic structures and presage later developments in jazz composition. “Social Call,” with lyrics by Jon Hendricks, has been performed by many singers including the late Betty Carter. Gryce’s catalog is published by Second Floor Music from which source lead sheets of several of his compositions can be downloaded.

A CD of previously unissued Gigi Gryce performances, Doin’ the Gigi, has been issued by Uptown Records.

A CD of Gigi Gryce music by the Chris Byars Quintet, Blue Lights: The Music of Gigi Gryce, has been issued by Steeplechase Records and available for purchase here.

Gigi Gryce

Gigi Gryce

Gigi Gryce was born George General Grice(sic) on 28th November, 1925 (not 1927) in Pensacola, Florida - although he was brought up in Hartford, Connecticut. He spent a short period in the Navy where he met musicians such as Clark Terry, Jimmy Nottingham and Willie Smith, who were to turn his thoughts from pursuing medicine to the possibility of making music for a living. In 1948 he began studying classical composition at the Boston Conservatory under Daniel Pinkham and Alan Hovhaness. It has been reported that he won a Fulbright scholarship and went to Paris to study under Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger, although confirmation of this has been hard to establish. Although illness interrupted his studies abroad, the fruits of this immersion in classical modernism were the production of three symphonies, a ballet (The Dance of the Green Witches), a symphonic tone-poem (Gashiya-The Overwhelming Event) and chamber works, including various fugues and sonatas, piano works for two and four hands, and string quartets.

Gryce strictly separated his classical composing from his work in jazz and received inspiration and instruction from a number of 'unsung' jazz saxophonists. The first of these was alto player Ray Shep, also from Pensacola, who had played with Noble Sissle. Then there were three musicians Gryce had met whilst based in the Navy in North Carolina. Altoists, Andrew 'Goon' Gardner, who played with the Earl Hines Band and Harry Curtis, who performed with Cab Calloway, as did tenorman Julius Pogue, for whom Gryce reserved the highest accolade. As well as alto saxophone Gryce performed on tenor and baritone saxes, clarinet, flute and piccolo - a 1958 recording for the Metrojazz label saw him multitracking all these instruments over a conventionally- recorded rhythm section.

Whilst in Boston (from 1948) Gryce arranged for Sabby

Lewis, and had working gigs with Howard McGhee and Thelonious Monk. When

playing at the Symphony Hall he attracted the attention of Stan Getz

who asked Gryce to arrange for him - Getz subsequently recorded three

Gryce originals: Yvette, Wildwood and Mosquito Knees. Dissatisfied with

these and other earlier compositions Gryce went on the Fulbright

scholarship outlined previously. Returning to New York, Gryce arranged

on record dates for Howard McGhee (Shabozz) and Max Roach (Glow Worm).

In the summer of 1953 Gryce joined Tadd Dameron's band, and in the

autumn of that year was with the Lionel Hampton band when they made

their legendary European tour. Through Hampton's band Gryce met many

musicians with which he was to collaborate with later, including

Clifford Brown , Art Farmer, Quincy Jones and Benny Golson. Against

Hampton's wishes this emerging nucleus of talent recorded a number of

sessions in Paris for French Vogue in between Hampton gigs. There were

many different permutations from quartets to a small big-band,

interestingly labelled as an orchestra, alluding to Gryce's exploration

of new orchestrations. Later that year Gryce married Eleanor Sears -

they had three children together: Bashir, Laila and Lynette - before

separating in 1964.

On returning to Manhattan after the Hampton tour, Gryce settled near to his former colleague Art Farmer, with whom he was to collaborate in a most productive quintet. In 1957 further memorable recordings were made with a group led by Thelonious Monk ('Monk's Music'), which Gryce described as one of the hardest and most humbling sessions he had known - in stark contrast with mostly first takes being used for an earlier 1955 session involving Monk. The Jazz Laboratory name, used previously for play- along records, was revived and shortened into the Jazz Lab Quintet, co-led by Gryce and trumpeter Donald Byrd. Oscar Pettiford made use of Gryce as player, composer and arranger for a couple of sessions which echoed the small orchestra Gryce had used for some French Vogue recordings. Some of the last jazz recordings Gryce made were in 1960, when he fronted a blues-oriented quintet which introduced the exuberant trumpet talent of Richard Williams.

After less than ten years in the jazz limelight Gryce decided to withdraw to the relative 'anonymity of the Long Island school system,' as jazz critic Ira Gitler critic put it. There has been much speculation as to the reasons for Gryce's sudden departure from the mainstream jazz scene, but it appears that a variety of influences and circumstances contributed to this: psychological pressures, business and publishing interests, and personal tragedy. It is often overlooked that Gryce was one of the first black musicians to form his own publishing company in order to have control over his and fellow musicians' creative output - many of the prominent black jazz musicians of the day were with Gryce's Melotone publishing company. It became clear, however, that Gryce couldn't buck the deeply ingrained system of record companies controlling (at least in part) music publishing rights as part of recording deals. Upon retiring from active involvement in the jazz scene suffering from a variety of psychological pressures, Gryce turned instead to music teaching (predominantly instrumental) - and such was his devotion that there exists a school in The Bronx named after him (PS53 Basheer Qusim School). He also married again and his second wife Ollie took his Muslim surname Qusim - it is believed that whilst in Paris, Gryce changed his name to Basheer Qusim on converting to Islam. He died of a massive heart attack upon recuperating in the town of his birth, Pensacola, on 17th March, 1983. The Jazz Society of Pensacola recently held a celebration of his music and life featuring a talk and performances and it is hoped to make this available on the website too.

Source: David Griffith

On returning to Manhattan after the Hampton tour, Gryce settled near to his former colleague Art Farmer, with whom he was to collaborate in a most productive quintet. In 1957 further memorable recordings were made with a group led by Thelonious Monk ('Monk's Music'), which Gryce described as one of the hardest and most humbling sessions he had known - in stark contrast with mostly first takes being used for an earlier 1955 session involving Monk. The Jazz Laboratory name, used previously for play- along records, was revived and shortened into the Jazz Lab Quintet, co-led by Gryce and trumpeter Donald Byrd. Oscar Pettiford made use of Gryce as player, composer and arranger for a couple of sessions which echoed the small orchestra Gryce had used for some French Vogue recordings. Some of the last jazz recordings Gryce made were in 1960, when he fronted a blues-oriented quintet which introduced the exuberant trumpet talent of Richard Williams.

After less than ten years in the jazz limelight Gryce decided to withdraw to the relative 'anonymity of the Long Island school system,' as jazz critic Ira Gitler critic put it. There has been much speculation as to the reasons for Gryce's sudden departure from the mainstream jazz scene, but it appears that a variety of influences and circumstances contributed to this: psychological pressures, business and publishing interests, and personal tragedy. It is often overlooked that Gryce was one of the first black musicians to form his own publishing company in order to have control over his and fellow musicians' creative output - many of the prominent black jazz musicians of the day were with Gryce's Melotone publishing company. It became clear, however, that Gryce couldn't buck the deeply ingrained system of record companies controlling (at least in part) music publishing rights as part of recording deals. Upon retiring from active involvement in the jazz scene suffering from a variety of psychological pressures, Gryce turned instead to music teaching (predominantly instrumental) - and such was his devotion that there exists a school in The Bronx named after him (PS53 Basheer Qusim School). He also married again and his second wife Ollie took his Muslim surname Qusim - it is believed that whilst in Paris, Gryce changed his name to Basheer Qusim on converting to Islam. He died of a massive heart attack upon recuperating in the town of his birth, Pensacola, on 17th March, 1983. The Jazz Society of Pensacola recently held a celebration of his music and life featuring a talk and performances and it is hoped to make this available on the website too.

Source: David Griffith

http://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2018/08/the-forgotten-ones-gigi-gryce-by-gordon.html

Friday, August 31, 2018

THE FORGOTTEN ONES - GIGI GRYCE by Gordon Jack

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“GIGI GRYCE, a shy, studious musician, barely out of his 'twenties, has been one of the herculean pillars of the modern jazz scene in New York through the 1950s. A composer and arranger, his work has been often heard and deeply felt wherever there is an audience for modern jazz; latterly through his own Jazz Lab, a unit which promises to release the small group from its ten years or more of strict allegiance to the Parker Quintet formula. It is, in the words of his contemporary Quincy Jones, "Always very melodic work, and it has a flowing quality with smoothly moving chord progressions. Also, it comes from that exceptional person, a conscientious composer with innocently fresh and unpretentious ideas."

As a soloist, too, he has been heard, lending a quiet and thoughtful style to the alto-saxophone at a time when the majority of its players are desperately struggling to invest themselves in the late Parker's robes.”

- Raymond Horricks,These Jazzmen of Our Times

Gordon Jack is the author of Fifties Jazz Talk: An Oral Retrospective and frequent contributor to Jazz periodicals such as JazzJournal. He also is extremely generous to the JazzProfiles “editorial staff” in allowing us to feature his well-researched and well-composed writings on these pages.

Alto saxophonist, composer and arranger Gigi Gryce impressed a lot of people with his compositions and his playing while he was on the Jazz scene in the 1950s before he vanished from it in 1961 under somewhat mysterious circumstances.

I’ve always considered Gigi to be right up there with Benny Golson, Horace Silver, Sonny Clark, Elmo Hope, and Tadd Dameron in his ability to construct intriguing and interesting modern Jazz compositions that are fun to listen to and fun to play on.

Gordon’s piece on Gigi first appeared in the August 2018 edition of JazzJournal and you can locate more information about the magazine by going here.

© - Gordon Jack/JazzJournal; used with permission; copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“In a short performing career Gigi Gryce worked with some of the most influential musicians on the dynamic New York jazz scene of the fifties including Clifford Brown, Benny Golson, Thelonious Monk and Max Roach. During that time his compositions like Minority, Social Call, and Nica’s Tempo became jazz standards. However in 1961 he mysteriously dropped out of the music scene entirely to become a teacher in the public school system in the Bronx where he was known by his Islamic name Basheer Qusim.

George General Gryce Jnr. was born in Pensacola, Florida on 28 November 1925. He came from a close and supportive family of African Methodist Episcopalians who attended services diligently. Music was important to his parents so Gigi and his siblings – four sisters and one brother - were encouraged to learn the piano. Church music was the order of the day as popular music and jazz were frowned upon. Thanks to the Works Progress Administration which was part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, Gigi began learning the clarinet when he was studying at the Booker T. Washington high school. His teacher was Raymond Sheppard who apparently had the best jazz orchestra in Pensacola. Gryce became so proficient that he won the state band competition for his clarinet solo on the William Tell Overture. When he graduated from high school he worked in the local shipyard and played with Sheppard until he was drafted in 1944. He joined the navy band at the Great Lakes Naval Training Centre which had been founded by John Philip Sousa in 1917. While in the service he had his first exposure to bebop when he bought the Charlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie recordings of Hot House and Salt Peanuts.

With the aid of the G.I. bill he enrolled at Boston’s Conservatory in 1947. He also studied privately with Serge Chaloff’s mother, the legendary Madame Margaret Chaloff. A partial list of her students would include Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, George Shearing, Ralph Burns, Leonard Bernstein and Chick Corea. By now a thoroughly well-schooled musician he began acquainting himself with Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns – a book that many other jazz musicians like John Coltrane, Pete Christlieb and Bob Cooper have found to be invaluable.

While studying at the Conservatory he was living with Sam Rivers and Jaki Byard and their basement was the scene for regular jam sessions with visiting stars from New York like Charlie Parker, Clark Terry, Stan Getz and Zoot Sims. Gryce who became particularly close to Parker told writer Robert Reisner, “I knew him as a gentleman and a scholar. He was generous to an extreme”. Many other local musicians used to come along to play like Serge Chaloff, Charlie Mariano, Alan Dawson and Joe Gordon. It is possible that Dick Twardzik who was working with Chaloff at the time and was another of Madame Chaloff’s students would have occasionally been in attendance but I have found no evidence to support this.

Although singer Margie Anderson recorded Gigi Gryce’s You’ll Always Be The One I Love in 1950, it was really Stan Getz who introduced Gryce’s music to the wider jazz public. Working at Boston’s HI-Hat in 1951 opposite Gryce’s quartet the tenor-man invited Gigi to bring some of his originals to a rehearsal. Thoroughly impressed, he recorded Gryce’s Melody Express, Yvette, Wildwood and Mosquito Knees for the Roost label later that year. Gigi had also shown Stan an intriguing blues dedicated to the lady who became his wife – Eleanor. It can be heard as part of the Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid arrangement Getz recorded at Boston’s Storyville club in October 1951. Over the years he used it as a theme-song and it became better known as Stan’s Blues. In December 1952 he recorded another Gryce original (Hymn To The Orient) on a classic set of ballads for Verve. All this material can be found on The Complete Recordings Of The Stan Getz Quintet With Jimmy Raney (Mosaic MD3-131).

Gigi left Boston and moved to Manhattan where he made his recording debut in April 1953 with a Max Roach group featuring Hank Mobley and Idrees Sulieman. Of more interest was a Howard McGhee session the following month which included two of his originals – Futurity and Shabozz. (Blue Note BLP 5024).The former is a relaxed line based on There Will Never Be Another You inspiring Gigi to probably his finest solo on the date. Although he does not solo on his next recording with Tadd Dameron, it is significant because of the presence of Clifford Brown and Benny Golson who would have close personal relationships with Gryce over the years. He and the trumpeter had similar lifestyles which did not include drinking, smoking or taking drugs. Gigi became godfather to Clifford Brown Junior and in 1958 he was the Best Man at Benny Golson’s marriage in Washington D.C.

In 1953 Tadd Dameron took a band which included Johnny Coles, Cecil Payne, Percy Heath and Philly Joe Jones along with Gryce, Golson and Brown for a summer residency at the Paradise Club in Atlantic City, New Jersey. They backed variety acts there and also played for dancers. On one occasion Sammy Davis Jnr. who was appearing at Skinny D’Amato’s 500 Club nearby sat in on drums. (The 500 Club was where Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis started out in 1946 and it eventually became a home-from-home for Sinatra and the Rat Pack.) Towards the end of the residency Quincy Jones arranged for Gryce, Brown and Golson to join the Lionel Hampton band that already boasted a number of young musicians like Art Farmer, Jimmy Cleveland, Buster Cooper, George Wallington, Annie Ross and Alan Dawson. Hampton (“The first rock & roll bandleader” according to Jones) would often have his musicians marching up and down the aisles at the Apollo theatre in Harlem and elsewhere playing The Saints, Flying Home or Hamp’s Boogie Woogie. That sort of showmanship did not go down too well with some of the newer band members, especially Brown, Gryce and Cleveland. Gigi appeared on Clifford’s debut as a leader just before the Hampton band left for their 1953 European tour. One of the stand-out tracks on the album is the trumpeter’s two choruses on Hymn To The Orient which is taken a little faster than Stan Getz’s version. Gigi has a sensitive half-chorus on Quincy Jones’s Brownie Eyes (Blue Note BLP 5032).

Lionel Hampton, encouraged by Gladys his formidable wife had a reputation of being less than generous with salaries but the lure of three months in Europe was enough for everyone except Benny Golson to overcome their reservations about the money. With its JATP-like atmosphere of excitement, the band proved to be hugely popular with European audiences. Standing ovations began at the first two concerts in Oslo where 2000 people attended and apparently continued for the rest of the tour. The Hamptons made it clear that nobody was allowed to record while they were in Europe without the leader and anyone found breaking this rule would be sent back to the States. Gryce, Brown and Cleveland found that European producers were desperate to record them and the musicians for their part were just as keen to supplement their band income. They tried, but Lionel and Gladys could not prevent numerous clandestine recordings taking place.

Henri Renaud produced a big band session in Paris with Gigi as the leader which included most of the Hampton band supplemented by local French musicians. The highlight was Gigi’s elaborate orchestral feature for Clifford Brown titled Brown Skins which after a slow, dramatic opening finds the trumpeter launching forth on a stunning up tempo examination of Cherokee –one of Brown’s favourite sequences (Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-359-2).

The next day, Brown recorded again with a sextet featuring Gryce, Jimmy Gourley, Henri Renaud, Pierre Michelot and Jean-Louis Viale. Gigi’s Blue Concept was introduced (later to be recorded by both Art Farmer and Donald Byrd) together with All The things You Are which has a fine improvised counter melody from Gryce behind Clifford’s theme statement. Goofin’ With Me is a relaxed theme-less jam on Indiana (Original Jazz Classics OJCCD 358-2). Hampton’s band then left for a series of concerts in Dusseldorf, Munich, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Berlin. On their return to Paris the Gryce-Brown sextet recorded four Gryce originals including Minority and Salute To The Bandbox which is based on I’ll Remember April (Original Jazz Classics OJCCD 358-2). Minority became Gryce’s most popular composition with over 100 recordings listed on Tom Lord’s discography by artists like Art Farmer, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans and Lee Konitz.

Hampton’s European tour which also included North African dates in Algiers and Oran was extremely successful. By the time they returned to NYC in November 1953 some of the sidemen threatened to go to the union over salary disputes. In a 1991 Jimmy Cleveland Cadence interview he said, “We got shafted with the money… (Hampton) would always do that”. For his part, the leader intended filing charges with the AFM against the musicians for recordings made in Paris using arrangements from his library without permission.

Early in 1954 Gryce and Art Farmer formed a quintet that worked quite extensively at Birdland and the Café Bohemia in NYC as well as out of town venues in Chicago, Baltimore and Boston. The following year Gigi recorded with Oscar Pettiford in an all-star group that included Ernie Royal, Donald Byrd, Bob Brookmeyer, Jerome Richardson, Don Abney and Osie Johnson. Oscar was the musical director of the Café Bohemia in Greenwich Village and Bohemia After Dark with its distinctive modal bridge is one of the album’s highlights (Bethlehem BET 6017-2). Brookmeyer told me that Oscar’s group also made an appearance on TV. Around this time Gigi organised his own publishing company (Melotone Music) in partnership with Benny Golson to handle their royalties.

In October 1955 he recorded four titles with Thelonious Monk proving to be perfectly at home in the pianist’s challenging environment. Accompanied by Percy Heath and Art Blakey he holds his own on Monk’s Shuffle Boil, Brake’s Sake and the fiendishly difficult Gallop’s Gallop (Savoy Records SV-0126). His Nica’s Tempo was debuted at the session and he later expanded it in a recording with Oscar Pettiford’s big band. At Oscar’s date he also wrote a feature for the amazing French horn players Julius Watkins and David Amram titled Two French Fries (Properbox 5002). Oscar’s band performed at Birdland and the Café Bohemia but eventually it disbanded due to a lack of work. Years later Jimmy Cleveland said, “One of the highlights of my life was playing with Oscar Pettiford’s band”.

Like the rest of the jazz world, Gryce had been impressed by the provocative tone colours and subtle dynamics created by the influential Miles Davis nonet and in late 1955 he recorded using an identical line-up. His charming Social Call with a lyric by Jon Hendricks was included as a feature for the husky-voiced Ernestine Anderson (Savoy Records SV-0126).

Metronome nominated Gigi Gryce, Mal Waldron and Donald Byrd as “The New Stars For 1956” which was the year Gryce started working with the Teddy Charles Tentet. The tentet performed innovative new material by writers like Mal Waldron, Gil Evans, George Russell, and Bob Brookmeyer and it made a well- received appearance at Newport that year. In 1956 he formed his Jazz lab Quintet initially with Idrees Sulieman and one of their first engagements was at The Nut Club in Greenwich Village where they appeared opposite Zoot Sims’ quartet. Donald Byrd soon replaced Sulieman and his sparkling ideas and warm, Clifford Brown-like sound were a perfect contrast to Gigi’s delicate alto lines. In 2006 Lonehill reissued a particularly fine example of the group’s work with a CD benefiting from the presence of the immaculate Hank Jones. It includes the popular Minority which opens with an extended ostinato - a favourite device of the Clifford Brown - Max Roach quintet. Another of Gryce’s originals – Wake Up – finds him quoting extensively from Denzil Best’s Wee aka Allen’s Alley in the second chorus (LHJ 10255).

In 1958 Gigi was one of the jazz musicians seen in the iconic Art Kane picture in Esquire magazine. For the next couple of years he continued playing and arranging on sessions with Betty Carter, Benny Golson, Jimmy Cleveland, Curtis Fuller and Randy Weston. However, something happened around 1960 because to the surprise of many in the jazz community, Gigi Gryce stopped playing entirely and dropped out of the public eye. There has been speculation that he was having business difficulties with his publishing company. Public taste of course was changing and clubs were closing. He may also have been unsympathetic to the freedoms being explored by the new generation of jazz musicians.

From 1963 and for the next 20 years he worked as a teacher in the public school system in Brooklyn and the Bronx. He had become a Muslim in the fifties and he used his Islamic name (Basheer Qusim) when teaching. The Community Elementary School No.53 was later renamed the Basheer Qusim/Gigi Gryce School in recognition of his long service. During this period, there was a surprising addendum to his musical career because his Jazz Dance Suite was featured in the 1972 documentary “Lenny Bruce Without Tears”.

George Gigi Gryce Jnr. died on March 14th. 1983 in his home town of Pensacola, Florida. Sadly, nobody from the jazz world attended his funeral.”

RECOMMENDED READING

Noal Cohen & Michael Fitzgerald – Rat Race Blues. The Musical Life Of Gigi Gryce. Berkeley Hills Books.

Nick Catalano -- Clifford Brown. The Life And Art Of The Legendary Jazz Trumpeter. Oxford University Press.

Raymond Horricks – These Jazzmen Of Our Time. Victor Gollancz.

http://hardbop.tripod.com/gryce.html

Gigi Gryce

"When evaluating Gryce's contribution it seems that he sometimes suffered in being grouped with other 'hard-boppers' of the younger New York school. Although he frequently collaborated with these musicians, Gryce, together with others more lyrically inclined, was heading in another direction."--David Griffith

Alto saxophonist, arranger, and composer Gigi Gryce grew up in Hartford, Connecticut, and began studies in composition with Daniel Pinkham and Alan Hovhaness at the Boston Conservatory in 1948. Having won a Fullbright scholarship, he contiued his studies in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger. After his return to the USA he became involved in jazz in New York, where he performed and recorded with Max Roach, Howard McGhee, Tadd Dameron, and Clifford Brown in 1953. Later that year he toured Europe with Lionel Hampton's band.

In 1954 he recorded with Donald Byrd, Lee Morgan, Thelonious Monk and others, and then the following year he began leading his own group, the Jazz Lab Quintet, which also included Byrd. In the 1960s he ceased playing jazz professionally and became a teacher.

Besides his principal instrument Gryce played clarinet and flute. His style was heavily influenced by Charlie Parker, though he had a thinner tone than Parker and lacked his melodic inventiveness. His skills as an arranger are represented by his recordings with Brown, Dizzy Gillespie, and Oscar Pettiford. His best-known jazz composition is "Minority." Among his classical compositions are three symphonies and various chamber works.

--THOMAS OWENS, The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz

The period during which this recording was done was one of entrenchment in New York for Art Farmer. He had returned from Europe in the fall of 1953, after touring with Lionel Hampton's band, and settled down in Manhattan. With his former Hampton colleague, Gigi Gryce, Art formed a quintet that recorded for Prestige but didn't work too often. By 1955, the jazz climate in New York had improved with a shift in policy of the Cafe Bohemia, which became the focal point and gathering place for musicians and aware listeners. Farmer and Gryce played with Oscar Pettiford at that Greenwich Village club, and also were able to work on their own. They recorded three times for Prestige, twice in 1955; first in May and again in September. The only constant in the rhythm section was Addison Farmer, Art's twin brother, who died tragically in February of 1963 before reaching his 35th birthday.

Gryce, with his writing skills and increasing prowess on the saxophone, co-led the Jazz Lab Quintet with Donald Byrd in the late '50s, and eventually formed his own group featuring Richard Williams. This latter combo is well-known to the Prestige audience through their recordings of the early '60s. In 1963, Gryce has been strangely silent, reportedly hibernating on Long Island.

--IRA GITLER, from the liner notes,

Art Farmer Quintet, Prestige.

A selected discography of Gigi Gryce albums.

- Nica's Tempo, 1955, Savoy.

- When Farmer Met Gryce, 1954-55, Prestige.

- The Jazz Lab Quintet, 1957, Riverside.

- The Jazz Lab, 1957, Columbia.

- Modern Jazz Perspective, 1957, Columbia.

- The Hap'nin's, 1960, Prestige.

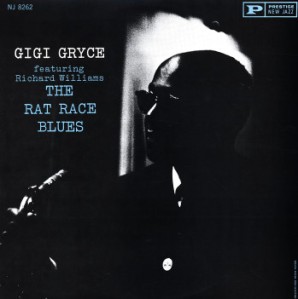

- Rat Race Blues, 1960, Prestige.

|

|

Gigi Gryce

Alto Saxophone

|

|---|

Photo by by Matt Micucci

This year, and more precisely November 28, marks the 90th anniversary of arguably one of the most influential, enigmatic and overlooked figures from the golden age of hard-bop – Gigi Gryce.

Gryce was born in 1925 in Pensacola, Florida. He had a relatively short career which lasted about a decade in the fifties and early sixties as a saxophonist, clarinetist, composer and arranger.

As a saxophonist, he was greatly influenced by Charlie Parker, who reportedly occasionally asked him to borrow his horn. He worked with some of the best-known names in jazz history, from Dizzy Gillespie to Thelonious Monk by way of Max Roach. Many of his compositions, such as Nica’s Tempo and Social Call, remain popular to this vary day and have been covered by various names numerous times.

He was acclaimed for his distinctive style. Despite Gryce being mostly associated with hard-bop, he is also praised to this day for very often pushing its boundaries to the limits of common practice. He was prone to unconventional harmonization, form and instrumentation as his style developed.

Despite his success, mysterious circumstances led to his abrupt retirement from the jazz scene in 1963. His very private nature also led him to his apparent disappearance. For decades, rumours were circulating about his wereabouts. He had, in fact, adopted his Islam name, Basher Qusim, and had alienated himself from his family. He had re-invented himself as a public school educator and was apparently an excellent music instructor. He left a partifularly long lasting legacy at Elementary School No. 53 in the Bronx, which was renamed in his honor after his death in his hometown of Pasadena in 1983 of a heart attack. He had just made his first attempt at re-connecting with his family for over twenty years.

The fascinating story of the life of this fascinating figure in jazz history is explored in the biographical book by Noal Cohen and Muchael Fitzgerald entitled Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Bryce.

The book, which finally told the true story of this often overlooked figure, was composed after years of research and dozens of interviews. In 2003, it won the Award for Excellence from the Association for Recorded Sound Collections. This was the first edition – the new edition has been updated with new information from another decade’s worth of research and is now available.

Loren Schoenberg, saxophonist and artistic director, National Jazz Museum in Harlem, said “There are any number of reasons for someone interested in the story of America and its music to delve deeply into the legacy of Gigi Gryce. To begin with, he was a superbly melodic composer who wrote pieces that linger in the memory. He was a master of writing music for larger ensembles and knew the intricacies of all of the instruments. This enabled him to combine them in ways that sounded fresh, and that were both challenging for the players and intriguing to the listener. Gigi Gryce is far too important a figure to remain in relative obscurity. This book will correct that situation.”

February 5, 2019

Gigi Gryce: Jazz Lab

The year 1957 was a bountiful one for Gigi Gryce. The alto saxophonist teamed with trumpeter Donald Byrd and formed the Jazz Lab, a group that allowed Gryce to record and perform his compositions and those by other artists with a singular feel that was outside of the jazz styles common then. From February to September 1957, Gryce and Byrd recorded Jazz Lab albums for five different labels—Columbia, Riverside, Verve, Jubilee and RCA. Despite the many attempts to gain traction for their new sound, the Gryce-Byrd experiment was short-lived.

Gryce, like Tadd Dameron, Quincy Jones, Benny Golson and Horace Silver, was a prolific, sexy writer and arranger with a distinctly arch, romantic sound that capitalized on sophisticated melodies and lush harmonies. His many jazz standards include Nica's Tempo, Blue Concepts, Minority, Wake Up!, Capri, Smoke Signal, Social Call, Satellite and An Evening in Casablanca, among others.

The Jazz Lab had less to do with experimentation in the avant-garde and was more concerned with amassing a large library of works and arrangements by a range of artists that fit its new jazz vibe and vision. As you listen to the Jazz Lab's recordings, you realize that their approach was unlike any other jazz style at the time.

The Jazz Lab didn't employ the bombast or unison horns of hard bop, the dryness of cool or nonchalance of West Coast jazz. Instead, the group had a pretty feel without being commercial. Melodies were lyrical, while background instruments functioned as sections of a band, supporting themes with complex harmony figures. As Gryce said back then, "We want to reflect all of the language of jazz and get into everybody's heart. And we're trying to develop another quality within ourselves."

In addition to Gryce's writing and arranging, he was a beautifully honest alto saxophonist with a determined urgency who favored the upper register. He was remarkable. In 1957, Byrd hadn't begun to record yet as a leader for Blue Note. That would follow in 1958 with Byrd's Off to the Races. Interestingly, his move to the label effectively ended the Jazz Lab collaboration. For eight brief months, Gryce and Byrd were on to something special.

Albums recorded by Gryce and Byrd's Jazz Lab:

- Jazz Lab (Columbia)

- Gigi Gryce and the Jazz Lab Quintet (Riverside)

- At Newport (Verve)

- New Formulas from the Jazz Lab (RCA)

- Jazz Lab (Jubilee)

- Modern Jazz Perspective (Columbia)

JazzWax tracks: You'll find the Complete Jazz Lab Studio Sessions Vol. 1 here, Vol. 2 here and Vol. 3 here. Or at Fresh Sound for less here, here and here.

Jazz Lab (Columbia) and At Newport (Verve) are at Spotify.

JazzWax clips: Here's Smoke Signal...

Here's Capri...

And here's Geraldine...

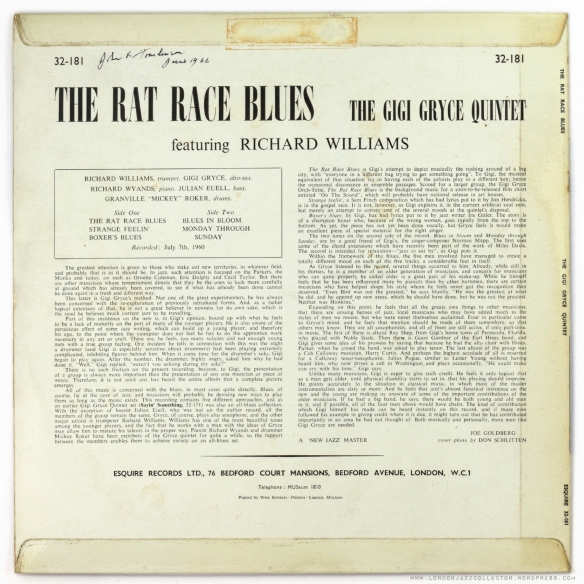

Gigi Gryce and 'Rat Race Blues'

10-Minute Listen

Even if you've never heard of Gigi Gryce, it's likely that you've heard his music. The saxophonist worked with and wrote for some of the giants of the industry, including Thelonious Monk and Quincy Jones. But after a short career, he gave it all up to become a schoolteacher. Karla Davis talks with the author of a new book about Gryce on All Things Considered.

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/1150008/150008" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

https://gigigrycebook.com/

The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce

Now Available!

Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce

By Noal Cohen & Michael Fitzgerald

Second Edition

ISBN 978-0-9906686-0-2

Published by Current Research in Jazz, Rockville, Maryland

Foreword by Benny Golson – Over 30 photographs

Winner of the 2003 Award for

Excellence from the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, the

first edition has now been updated with new information from another

decade’s worth of research.

Gigi Gryce was a saxophonist and composer who worked with some of the best-known names in jazz during the 1950s, including Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Max Roach. His many compositions remain a part of the jazz repertoire today.

His remarkable rise from poverty led to conservatory studies and tours of Europe and Africa before he established himself as a fixture on the New York scene. His efforts as a music publisher were bold and groundbreaking, and his quiet, unassuming personality set him apart from most of his peers. In only a decade as a professional musician, he earned the respect and admiration of his colleagues and served as a mentor to numerous aspiring young players. Gryce’s sudden disappearance at the start of the 1960s left the jazz world wondering as to his fate. Few were aware of his change of identity and professional rebirth.

Misinformation about Gryce abounds, and rumors have circulated for decades. Years of research and dozens of interviews were conducted for this book, resulting in a biography that finally tells the true story of this often overlooked figure and illuminates his contributions to one of the richest periods in jazz history.

“There are any number of reasons for someone interested in the story of America and its music to delve deeply into the legacy of Gigi Gryce. To begin with, he was a superbly melodic composer who wrote pieces that linger in the memory. He was a master of writing music for larger ensembles and knew the intricacies of all of the instruments. This enabled him to combine them in ways that sounded fresh, and that were both challenging for the players and intriguing to the listener. Gigi Gryce is far too important a figure to remain in relative obscurity. This book will correct that situation.” --Loren Schoenberg, saxophonist and artistic director, National Jazz Museum in Harlem

Some reviews of the first edition:

“Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce” has established a new standard against which all future jazz biographies must be judged.” – Bill Barton, Signal To Noise

“To say this biography is a comprehensive undertaking would be an understatement. It is also an interesting and important contribution to jazz literature.” – Rob Bauer, IAJRC Journal

“Cohen and Fitzgerald have done a heroic job of tracking down obscure facts and questioning the accepted details…a work of quality.” – Brian Priestley, Jazz Research News

“Cohen and Fitzgerald have done a masterful job of bringing Gryce’s life to light…an exemplary study of a neglected figure.” – Coda Magazine

Available for purchase now at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and elsewhere.

Additional Gigi Gryce Items of Interest:

- Gigi Gryce Lead Sheets from Second Floor Music

- The Gigi Gryce Project – Downloadable recordings of 12 Gryce compositions from a 1999 session produced by Don Sickler. The ensemble is an all-star quintet made up of Bobby Porcelli (alto sax), Ralph Moore (tenor sax), Richard Wyands (piano), Peter Washington (bass) and Kenny Washington (drums). The tracks are also available as play-alongs for various instruments.

- Doin’ the Gigi – Uptown Records CD

- Blue Lights: The Music of Gigi Gryce – Steeplechase Records CD by Chris Byars

Follow on Facebook

LondonJazzCollector

Adventures in collecting "modern jazz": the classical music of America from the Fifties and Sixties, on original vinyl, on a budget, from England. And writing about it, since 2011.

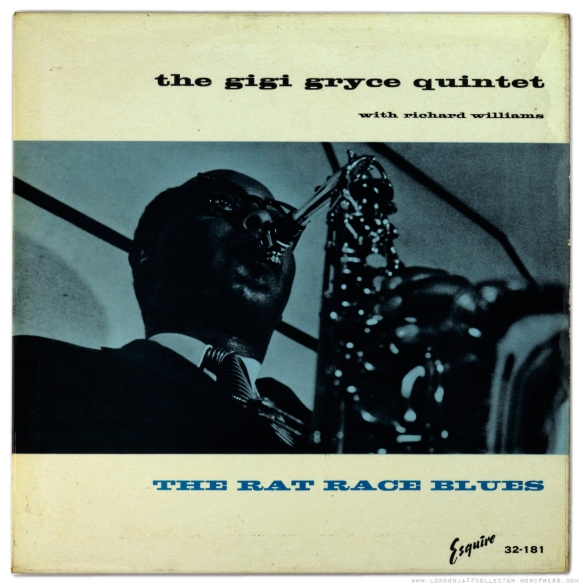

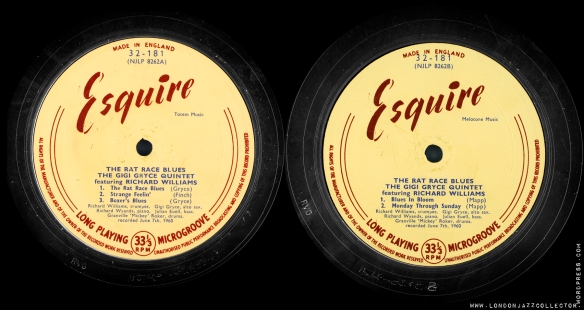

Artists: Richard Williams

(trumpet) Gigi Gryce (alto saxophone) Richard Wyands (piano) Julian

Euell (bass) Mickey Roker (drums) recorded at Rudy Van Gelder Studio,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ, June 7, 1960

From the early ’50s George General Gryce,

Gigi (or G.G. as it should be pronounced) enjoyed a ten year career in

the jazz limelight. An accomplished alto and tenor saxophonist, Gryce

was much influenced by Charlie Parker, with

whom he became friends in the mid fifties. It is said Parker would

sometimes borrow Gryce’s horn, no doubt when his own was in

hock. Playing with the likes of Howard McGhee, Thelonious Monk, Max

Roach, Clifford Brown, a partner with Donald Byrd as The Jazz Lab, Gryce was a promising star in the ascendant but Rat Race Blues was the last of three titles he recorded for Prestige, before he too threw in the sponge.

Bowing out of the music scene Gryce withdrew to the relative ‘anonymity of the Long Island school system’ (op cit. Ira Gitler)

exchanging music teaching for music performing, a destination followed

by many great players who for whatever reason found the life of a

working jazz musician personally unsustainable.

As an insight into the business side of

jazz, Gryce was noted for being one of the first to tackle the scandal

of music publishing royalties. Record companies including, I assume, Prestige, routinely helped

themselves to 50% of artists royalties simply by assigning the

artists work to their own publishing unit, who then filled in the

copyright registration forms and submitted them to the performing rights

organisation BMI. Musicians rarely understood the business side of

royalties, but record companies certainly did, and took advantage of

musicians innocence.

Record companies including, I assume, Prestige, routinely helped

themselves to 50% of artists royalties simply by assigning the

artists work to their own publishing unit, who then filled in the

copyright registration forms and submitted them to the performing rights

organisation BMI. Musicians rarely understood the business side of

royalties, but record companies certainly did, and took advantage of

musicians innocence.

Record companies including, I assume, Prestige, routinely helped

themselves to 50% of artists royalties simply by assigning the

artists work to their own publishing unit, who then filled in the

copyright registration forms and submitted them to the performing rights

organisation BMI. Musicians rarely understood the business side of

royalties, but record companies certainly did, and took advantage of

musicians innocence.

Record companies including, I assume, Prestige, routinely helped

themselves to 50% of artists royalties simply by assigning the

artists work to their own publishing unit, who then filled in the

copyright registration forms and submitted them to the performing rights

organisation BMI. Musicians rarely understood the business side of

royalties, but record companies certainly did, and took advantage of

musicians innocence.

Gryce astutely circumvented the process by self-publishing through the Melotone

company he formed jointly with Benny Golson, which affiliated to BMI

and then received royalties direct, by-passing the record company. How

popular this made him with record companies, or whether it played

any part in his departure from the music scene, is for conjecture.

AllMusic verdict on Rat Race Blues: four stars – “Interesting and generally fresh straight-ahead jazz”

Sounds great. To my ear Gryce has a wonderfully fluid propulsive touch,

soaring though the changes, lyrical, delightful to the ear, and lifted

further by the interesting presence of trumpeter Richard Williams, who

also served a similar apprenticeship to Gryce with the Lionel Hampton

Band in the early ’50s. .

Williams managed only one title to his credit as leader, on the short-lived Candid label (Candid threw in the sponge

in 1961, after only a year’s existence). Williams appears as a sideman

on numerous Blue Note and Impulse, most notably on some of Mingus’

greatest recordings, including Ah Um; Mingus Dynasty and The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. . Described as a “strong soloist with a big sound and a wide range” his promising career also faltered but he found work in the brass sections of big bands, Broadway show pits, eventually joining the excellent Mingus tribute recording group Mingus Dynasty.

Wyands comping is

remarkably uplifting, raising chordal harmonic excursions against the

time-keeping rhythmic tempo. Bassist Julian Euell aquits himself well

as a sideman. He seems to have spent a lot of time a student, opting to

take a bachelor’s in Sociology, teaching and active social

work, combining a career in public administration with occasional

musical appearances. He sort of wouldn’t let go of the sponge.

Both G.G. and Williams succumed to illness and departed in the ’80’s, before their time. At the end, it’s the sponge that throws you in.

Vinyl: Esquire 32-181 UK release of Prestige new Jazz 8262 (nice cover)

Note Side Two bears the copyright assertion “Melotone Music”, though

Side One is assigned to “Totem Music” . All these copyright assertions

on labels are only now beginning to make sense.

Report this ad

Collectors Corner

An Ebay win, not overly expensive as I recall, G.G clearly not on many

collector’s searches, and not associated with those warhorse early Blue

Notes, which I’m frankly getting a bit fed up with chasing. I can live

quite happily without an original 1st pressing of 1560 or 1558, life’s

too short, I throw in the sponge.

Collectors Corner

An Ebay win, not overly expensive as I recall, G.G clearly not on many

collector’s searches, and not associated with those warhorse early Blue

Notes, which I’m frankly getting a bit fed up with chasing. I can live

quite happily without an original 1st pressing of 1560 or 1558, life’s

too short, I throw in the sponge.

There is much more fun to be had rummaging in the bin of lesser titles, a few more of which will be coming up shortly.

Gigi Gryce

Gigi Gryce (born George General Grice Jr.; November 28, 1925 – March 14, 1983), later Basheer Qusim, was an American jazz saxophonist, flautist, clarinetist, composer, arranger, and educator.

While his performing career was relatively short, much of his work as a player, composer, and arranger was quite influential and well-recognized during his time. However, Gryce abruptly ended his jazz career in the 1960s. This, in addition to his nature as a very private person, has resulted in very little knowledge of Gryce today. Several of his compositions have been covered extensively ("Minority", "Social Call", "Nica's Tempo") and have become minor jazz standards. Gryce's compositional bent includes harmonic choices similar to those of contemporaries Benny Golson, Tadd Dameron[1] and Horace Silver. Gryce's playing, arranging, and composing are most associated with the classic hard bop era (roughly 1953–1965). He was a well-educated composer and musician, and wrote some classical works as a student at the Boston Conservatory. As a jazz musician and composer he was very much influenced by the work of Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk.[2]

Early life

George General Gryce Jr. was born in Pensacola, Florida on November 28, 1925.[1][3]

His family's strong emphasis on music, manners, and discipline had a tremendous effect on him as a child and into his later career. Grice's parents were of modest means, his mother a seamstress and his father the owner of a small cleaning and pressing service. The family belonged to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and attended services diligently. Especially as the Great Depression began to take its toll on the family's financial welfare, the Grices did their best to instill the value of discipline and hard work in their children.[4]

Music was very much emphasized in the Grice household. The family had a piano in the house, which Gigi and his siblings (four older sisters and one younger brother) were encouraged to play. Mostly church music was performed in the Grice home, while pop and jazz was mostly frowned upon. (Later, however, when Gigi pursued jazz as a career, his mother and older sisters would support him personally and financially.) Many of the Grice children were encouraged to pursue vocal performance at church, school, and other community; for a time the family even held weekly recitals in their home.[5]

The early thirties saw tragedy and hardship for the Grice family. In 1931, as the economic crisis of The Great Depression began to take hold, the Grices were forced to sell their cleaning business. Two years later, Gigi's father, George Sr., died after suffering a heart attack. Rebecca Grice was forced to raise the children as a single mother, relocating the family in order to rent out the house. Even through this hardship, however, Rebecca continued to motivate her children for success through strict but supportive parenting, encouraging musical development, hard work, discipline, and Christian morals.[6]

Gigi very much applied his family's sense of discipline to his developing passion for music. As a youth Gigi was described as bright but reserved, extremely polite, studious, and formal in nature. It is unclear exactly when Gigi first began learning the clarinet – it is rumored he may have started as early as age 9 or 10, but the first evidence for his pursuit appears later as he entered high school. The under-resourced, and at this time, mostly black Booker T. Washington High School had a series of music teachers through the Federal Music Project; Gigi first studied with Joseph Jessie and later Raymond Shepard. As it was for many, a musical instrument would have been a crippling expense for the Grices during the Depression; when Gigi and his brother Tommy studied clarinet with Shepard they allegedly borrowed the same clarinet from a friend directly before each lesson. Eventually, Gigi's mother was able to buy him his own metal cavalry clarinet, with which Gigi became quite successful as a high school student, winning school and state competitions. At school Gigi was also able to study music theory, which he very much enjoyed and continued to explore on the piano at home [7]

Early music career

Gryce graduated from high school in 1943, working at the shipyard and playing in Raymond Shepard's professional band for a time before being drafted by the navy in March 1944. Gryce continued to pursue music during his two-year term, making his way into the navy band and earning the rank of musician second class. While stationed in Great Lakes, Illinois, Gryce spent time in Chicago during leaves and became more acquainted with the sound of bebop. It was at this time that he bought his own alto saxophone and, in Chicago, that he met musicians Andrew "Goon" Gardner and Harry Curtis. Gryce may have even briefly studied at the Chicago Conservatory of Music.[8]

After completing his time in the navy, Gryce decided to continue his musical education, financially supported by the G.I. Bill as well as his mother and older sisters. He moved to Hartford to live with his sister Harriet and her husband in 1946, and the following year enrolled at the Boston Conservatory. At the Boston Conservatory Gryce developed his theoretical background and studied classical composition, writing three symphonies and a ballet in addition to other works. He was very much inspired and influenced by the work and philosophy of Boston Conservatory composer Alan Hovhaness, a musical eclectic whose passion was for melodicism and lyricism.[9]

During his time at the conservatory Gryce also developed connections in the Hartford, Boston, and New York jazz scenes which would have a tremendous effect on his later career as a jazz musician, composer, and arranger. While New York was best known for cutting edge jazz of the time, both Boston and Hartford were also the sites of active and innovative jazz scenes. Gryce traveled between the two cities, and arranged for local bands including those of Sabby Lewis, Phil Edmonds, and Bunky Emerson. While Gryce developed his theoretical background and a passion for the works of Bartok and Stravinsky, he simultaneously developed an obsession for the work of Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, with whom, around 1949, he became acquainted and also performed. Gryce developed a reputation as a well-trained and talented artist, and became relatively well known in the local Boston and Hartford scenes. He also began to explore the New York scene, where he would eventually find himself in the early fifties.[10]

Gryce is rumored to have traveled to Paris on a Fulbright scholarship in 1951 to study with Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger. However, there is much confusion and rumor surrounding this period in Gryce's life, and there is no evidence to suggest that Gryce did receive a Fulbright or formally study with the two composers. Gryce did take two semesters off to study in Europe, but little is known about his travels. It is possible that he studied with the composers privately. While Gryce did propagate the Fulbright rumor himself to substantiate his credentials, Gryce had little else to say about this time in his life.[11]

New York, the Lionel Hampton band, and Europe

After graduating with a degree in composition in 1952, Gryce relocated to New York City, where he would enjoy much success in the mid fifties. In 1953 Max Roach recorded one of Gryce's charts with his septet, and soon after Gryce recorded with Howard McGhee and wrote for Horace Silver's sextet as well.[12]

Gryce was influenced by Tadd Dameron, with whom he played in 1953 at the Paradise Club.[13] Gryce had not yet reached his peak as a musician or soloist, but was developing a reputation as a versatile and talented composer and arranger. Later in 1953 Gryce also contributed a tune, "Up in Quincy's Place" to Art Farmer's Prestige recordings. While this recording was rather inconsequential, Farmer would become one of Gryce's closest colleagues.[14]

One of the most important connections Gryce made in New York was with Quincy Jones, who encouraged Lionel Hampton to hire Gryce for his band in the summer of 1953. After playing with Hampton's band in the States, Gryce was invited to join the band for their European tour.[15]

While the style of the Hampton band was outdated and overly commercialized in Gryce's eyes, the opportunities and connections made on the European tour were largely what propelled Gryce into success as an artist. In Hampton's band, Gryce played with Anthony Ortega, Clifford Solomon (tenor saxophone), Clifford Scott, Oscar Estelle (baritone saxophone), Walter Williams (trumpet), Art Farmer, Clifford Brown, Quincy Jones, Al Hayse, Jimmy Cleveland, George "Buster" Cooper, William "Monk" Montgomery, and Alan Dawson. Gryce became particularly close friends with Clifford Brown, with whom he found much in common. The Hampton tour did not pay well, and Gryce and others frequently sought recording opportunities on the side, particularly in Stockholm and Paris, where Europeans were eager to record touring Americans. There was already some tension in the band between young bebop-influenced musicians and the more established swing musicians (including Hampton himself), and Hampton did not react well when he heard his musicians were recording on the side.[16]

The recordings Gryce made with Clifford Brown and others on the tour were often hurried and done on the fly, yet they were instrumental in building his career, particularly as a composer. Notable of these European recordings were "Paris the Beautiful", featuring tonal centers a third apart and a Parker-influenced solo by Gryce; "Brown Skins", a concerto for a large jazz ensemble; "Blue Concept", recorded by the Gryce-Brown sextet; and "Strictly Romantic", which oscillates between A flat and G major. In addition, Henri Renaud recorded an entire album exclusively of Gryce's work, which did a great deal to build his reputation.[17]

Career in the United States

Gryce and the other personnel from the Hampton Band returned to New York in November 1953, where the hard bop scene was just beginning to gain traction. This was the perfect time for Gryce to arrive on the scene. Soon after his return, he recorded with Henri Renaud, and Art Blakey recorded seven of Gryce's songs for EmArcy records. Gryce formed a quintet with Farmer in March 1954, which first recorded for Prestige Records in May of that year. Personnel included pianist Horace Silver, bassist Percy Heath, and Drummer Kenny Clarke. Gryce's works with Farmer are some of his most influential and best known. In June of that year Gryce again recorded with Farmer, this time exclusively as composer and arranger. By the time Farmer and Gryce began their third project, they had hit their creative stride.

The record made in May 1955 by the Farmer-Gryce quintet featured pianist Freddie Redd, bassist Addison Farmer, and drummer Art Taylor. This session exemplifies Gryce's feel for thematic development, all of the pieces artfully composed and arranged. Later in 1955 Gryce also played for Oscar Pettiford's octet, and got the opportunity to play alto in Thelonious Monk's recording with Percy Heath and Art Blakey for Signal Records.[18]

The final ticket to Gryce's success was his third recording with the Farmer Quintet in October 1955 and his nonet recordings for Signal Records immediately after. The Farmer record featured non-standard forms, and adventurous arrangements which pushed the limits of the hard bop idiom. His Signal Records arrangements were very much influenced by the style and instrumentation of Miles Davis's Birth of the Cool group, and were very well received by the jazz community. By the mid-1950s Gryce was a major figure in jazz, known as a great individualist, a competent studio musician, and an innovative composer.[19]

Publishing career

In addition to his musical career, Gryce was a vehement advocate of composers' and musicians' rights. In 1955 he started his own publishing company, Melotone Music, and later an additional company called Totem. This was a time when black musicians in particularly were taken advantage of by the music industry. Many musicians neglected the business side of their careers or were actively cheated by record companies. As a composer Gryce always ensured that he got credit for his work, and actively encouraged his colleagues to do the same. Silver largely credits Gryce with inspiring him to found his Ecaroh Music company and the Silveto label. Little is known about Gryce's financial troubles in the early 1960s, but this hardship very much contributed to Gryce's breakdown and withdrawal from the jazz community.[20]

Decline

Gryce stayed on the cutting edge through 1956 until his career peaked in 1957. He worked on several projects as composer and arranger with the Teddy Charles Tentet and the Oscar Pettiford Orchestra. The Tentet began as an outgrowth of Charles Mingus's Jazz Composers Workshop, and was very successful as a performing dance band despite its experimental nature. His work with the Oscar Pettiford Orchestra was also extremely well-recognized, producing significant coverage to the musicians who participated as well as to Gryce himself.[21]

In 1957 Gryce and Donald Byrd collaborated on a series of projects with Jazz Lab, which produced play-along recordings as educational tools. Gryce's arrangements were fresh but accessible, tailored for educational purposes. The rhythm section played with a soloist to give the play-alongs a more natural feel. The group also performed, and gave a rather lukewarm performance at the Newport Jazz Festival.[22]

The years 1957 to 1960 saw a series of miscellaneous projects for Gryce. He continued to play with the Jazz Lab, as well as writing for Betty Carter, Art Farmer, Jimmy Cleveland, Curtis Fuller, and Max Roach.[23] He put together his own quintet, which he renamed the Orch-tette after adding vibraphonist Eddie Costa in 1960. His recordings with the Orch-tette had potential, but featured intricate arrangements which limited space for solos.[24] Gryce worked on a handful of other projects in 1960, including a film score to On the Sound by Phil Baker and a final studio recording on Randy Weston's Uhuru Afrika. However, by this time Gryce was becoming preoccupied with business troubles associated with his publishing companies, as well as some family issues.[25] Gryce's genre of hard bop was beginning to give way to more experimental strains. Around 1963, Gryce withdrew completely from his jazz career.[citation needed]

Personal life

From childhood Gryce was always marked by a private and formal disposition. While he was very well liked by his colleagues, he was often very much an outsider in the community. Gryce also followed a strict moral lifestyle, abstaining from alcohol, drugs, and other vices common among his colleagues.[26]

Family life

Gryce is known to have had two romantic relationships before his marriage to Eleanor Sears in 1953. Gryce had a brief relationship with Evelyn "Baby" Dubose in Pensacola during his Pensacola and Navy years, for whom he named his piece "Baby" which was recorded in Europe in 1953.[27] He also had a casual relationship with vocalist Margie Anderson, with whom he worked during his time in Boston.[28] On December 20, 1953, soon after his return from the Lionel Hampton tour, he married Eleanor Sears, to whom he was introduced by trumpeter Idrees Sulieman.[29] Several of his compositions are credited to pseudonym "Lee Sears."

They had three children: Bashir (born 1957); Laila (born 1959); and Lynette (born 1963).[30] They also had a child, Bilil, in 1958 who was born prematurely and did not survive infancy.[31]

Conversion to Islam

Gryce had always been described as having a strict moral sensibility. He may have been interested in Islam as early as 1950, and as a student became interested in religious history.[32] At the Boston Conservatory in 1953 he named one of his symphonies "Gashiya" for a surah in the Qur'an.[32] Gryce reveals little about who or what urged his conversion, but Islam was an increasingly popular faith among black jazz musicians in the fifties, particularly Ahmadiyya, Nation of Islam, and Sunni Islam.[33] Gryce is believed to have converted during or shortly after his travels in Europe during his college years.[34] While Gryce did not regularly attend the mosque, he did read the Qur'an and abstain from drugs, alcohol, and pork.[35] His faith was a source of some tension in his marriage to Eleanor, who remained a practicing Christian.[35] Many of Gryce's compositions had Islamic titles and his first two children Islam-inspired names.

Withdrawal, teaching career, and death

Little is known about the real nature of Gryce's retreat from jazz, as this period is characterized by a great deal of misunderstanding and rumor. Gryce revealed very little about his business hardships, but what is known is that his publishing business encountered financial troubles in the early 1960s, with many musicians withdrawing from Melotone and Totem.[36] Many of his colleagues believe that powerful interests considered Gryce's publishing activities a threat, and were forcing him out of business. Rumors circulated about intimidation and threats to his family. While these rumors have not been confirmed, Gryce's behavior became extremely introverted and erratic during this time. He dissolved his publishing companies in 1963 and gave up his music career, thereafter adopting his Islamic name entirely, Basheer Qusim.[37]

In the 1960s Gryce reinvented himself as a public school teacher in New York. He was somewhat interested in education throughout his life, and was said to be an excellent music instructor. He received a master's degree in education from Fordham University in 1978 and developed an incredible passion for teaching. He left a lasting legacy at Elementary School No. 53 in the Bronx, which was renamed in his honor after his death. Students, colleagues, and parents who encountered Gryce during this time knew him as a very private, serious, passionate, and caring man. Believing that music aided literacy, Gryce was a strict but caring teacher, and went out of his way to aid students at educational risk, working at an under-resourced mostly black and Hispanic school.[38]

Gryce died on March 14, 1983, of a heart attack after becoming increasingly ill. Before his death he reached out to his family again, and visited Pensacola for the first time in almost thirty years.[39]

Musical style, influences, and legacy

While in many ways his work exemplifies the conventions of the hard bop era, Gryce always attempted to push the limits of common practice. As an educated composer with an extensive theoretical background, Gryce was prone to unconventional harmonization, form, and instrumentation as his style developed. In "Up in Quincy's Place", one of his very early tunes, Gryce was rather ahead of his time in his frequent use of quartal harmony, a practice that would be popularized during the cool jazz era.[40][41]

His compositions and arrangements with Farmer continued to feature non-standard forms and harmonies 175.[40] His approach to hard bop trod the line between experimental and accessible, particularly in later work with the Teddy Charles Tentet and the Oscar Pettiford Orchestra. As an experimental composer, his goal was not jazz without limits, but forms which provided boundaries which liberated the soloist.[42]

While Gryce was a very accomplished saxophonist, clarinetist, and flautist his playing tended to be less innovative than his writing. As a saxophonist he was always very much influenced by Charlie Parker, who he had always idolized and became friends with in the mid-fifties. Contemporaries recall that Parker would sometimes borrow Gryce's horn.[43]

Discography

As leader

- 1954–55 When Farmer Met Gryce (Prestige) with Art Farmer

- 1955 Nica's Tempo (Savoy)

- 1957 Jazz Lab (Columbia) with Donald Byrd

- 1957 Gigi Gryce and the Jazz Lab Quintet (Riverside)

- 1957 At Newport (Verve) with Donald Byrd [One side of LP; other side is by Cecil Taylor]

- 1957 New Formulas from the Jazz Lab (RCA Victor) – with Donald Byrd

- 1957 Jazz Lab (Jubilee) – with Donald Byrd

- 1957 Modern Jazz Perspective (Columbia) – with Donald Byrd and Jackie Paris

- 1958 Gigi Gryce (MetroJazz)

- 1960 Saying Somethin'! (New Jazz)

- 1960 The Hap'nin's (New Jazz)

- 1960 The Rat Race Blues (New Jazz)

- 1960 Reminiscin' (Mercury)

- 2011 Doin' the Gigi – previously unissued tracks 1957–1961 (Uptown)

As sideman/arranger

With Art Blakey- Blakey (EmArcy, 1954)

- Mirage (Savoy, 1957) – arranger

- Theory of Art (RCA Victor, 1957) – arranger

- New Star on the Horizon (sextet with Charlie Rouse) (Blue Note 1953) included in Blue Note Memorial Album

- Memorial Album (Blue Note, 1956)

- Memorial (Clifford Brown album) (Prestige, recorded 1953, released 1956)

- The Clifford Brown Sextet in Paris (Prestige PR 7794, Released 1970, Recorded 1953)

- Clifford Brown in Paris (Complete Master Takes) (Prestige 24020, Released 1971, Recorded 1953)

- Social Call (Columbia, 1956 [1980])

- Out There (Peacock, 1958) – rereleased as part of I Can't Help It (1982)

- The Teddy Charles Tentet (Atlantic, 1956)

- Rhythm Crazy (EmArcy, 1959 [1964]) – arranger

- Earl Coleman Returns (Prestige, 1956)

- Afro-Cuban (Blue Note, 1955) – arranger

- Jazz Contrasts (Riverside, 1957) – arranger

- The Art Farmer Septet (Prestige, 1954) – arranger

- Art Farmer Quintet featuring Gigi Gryce (Prestige 1955) (Prestige New Jazz 1962 as Evening In Casablanca)

- Modern Art (United Artists, 1958) – arranger

- Sliding Easy (United Artists, 1959) – arranger

- Jazz Recital (Norgran, 1955)

- The Greatest Trumpet of Them All (Verve, 1957)

- Benny Golson's New York Scene (Contemporary, 1957)

- The Modern Touch (Riverside, 1957) – arranger

- Benny Golson and the Philadelphians (United Artists, 1958) – arranger

- The Magnificent Thad Jones Vol. 3 (Blue Note, 1957)

- Do It Yourself Jazz Vol. 1 (Savoy, 1955) – with Duke Jordan Oscar Pettiford, Kenny Clarke

- Salute to the Flute (Epic, 1957) – arranger

- The Modern Art of Jazz (Dawn, 1956)

- Big Maybelle Sings (Savoy, 1957)

- Howard McGhee Volume 2 (Blue Note, 1953)

- Monk's Music (Riverside, 1957)

- Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane (Riverside, 1957 [1961])

- Lee Morgan Vol. 3 (Blue Note, 1957)

- Another One (Bethlehem, 1955)

- The Oscar Pettiford Orchestra in Hi-Fi (ABC-Paramount, 1956) – performer, composer and arranger

- The Oscar Pettiford Orchestra in Hi-Fi Volume Two (ABC-Paramount, 1958) – performer and arranger

- The Big Beat (Columbia, 1956)

- The Max Roach Quartet featuring Hank Mobley (Debut, 1954)

- Rich Versus Roach (Mercury, 1959) – arranger

- The Touch of Tony Scott (RCA Victor, 1956)

- The Complete Tony Scott (RCA, Victor, 1957)

- Mal-1 (Prestige, 1956)

- Uhuru Afrika (Roulette, 1960)

- Blues Shout (Atlantic, 1961) – arranger

References

- Cohen, Noal; Fitzgerald, Michael. Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce. Berkeley: Berkeley Hill Books, 2002. p. 157.

External links

https://www.gigigryce.com/

[Discography |

Critique

| Song Index | Links

|

Search |

Bibliography

| What's New]

A wealth of material has now been accumulated

that is not featured within these Web pages - if you would like further

details or information on any aspect Gryce's life and work please email

me.

Gigi Gryce was born George General Grice(sic) on 28th November, 1925 (not 1927) in Pensacola, Florida - although he was brought up in Hartford, Connecticut. He spent a short period in the Navy where he met musicians such as Clark Terry, Jimmy Nottingham and Willie Smith, who were to turn his thoughts from pursuing medicine to the possibility of making music for a living. In 1948 he began studying classical composition at the Boston Conservatory under Daniel Pinkham and Alan Hovhaness. It has been reported that he won a Fulbright scholarship and went to Paris to study under Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger, although confirmation of this has been hard to establish. Although illness interrupted his studies abroad, the fruits of this immersion in classical modernism were the production of three symphonies, a ballet (The Dance of the Green Witches), a symphonic tone-poem (Gashiya-The Overwhelming Event) and chamber works, including various fugues and sonatas, piano works for two and four hands, and string quartets.

Gryce strictly separated his classical composing from his work in jazz and received inspiration and instruction from a number of 'unsung' jazz saxophonists. The first of these was alto player Ray Shep, also from Pensacola, who had played with Noble Sissle. Then there were three musicians Gryce had met whilst based in the Navy in North Carolina. Altoists, Andrew 'Goon' Gardner, who played with the Earl Hines Band and Harry Curtis, who performed with Cab Calloway, as did tenorman Julius Pogue, for whom Gryce reserved the highest accolade. As well as alto saxophone Gryce performed on tenor and baritone saxes, clarinet, flute and piccolo - a 1958 recording for the Metrojazz label saw him multitracking all these instruments over a conventionally-recorded rhythm section.