SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2020

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER TWO

HERBIE HANCOCK

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

RICHARD DAVIS

(February 22-28)

JAKI BYARD

(February 29-March 6)

CHARLES LLOYD

(March 7-13)

CHICO HAMILTON

(March 14-20)

JOHNNY HODGES

(March 21-27)

LEADBELLY

(March 28-April 3)

SIDNEY BECHET

(April 4-April 10)

DON BYAS

(April 11-17)

FLETCHER HENDERSON

(April 18-24)

JIMMY LUNCEFORD

(April 25-May 1)

KING OLIVER

(May 2-8)

WAR

(May 9-15)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/king-oliver-mn0000094639/biography

King Oliver composed a lot of songs during this period, and many are jazz classics. “Snake Rag”, “Sugarfoot Stomp”, “West End Blues”, and “Dr Jazz”, the latter were covered by Jelly Roll Morton, and always in his songbook. He wrote a lot of blues, two of the better known are “Camp Meeting Blues”, and “Workingman’s Blues”. The blues he is most associated with is “Dippermouth Blues”, which is known for his soloing. He was a tough businessman as well and made sure his songs were copyrighted and he received his royalties.

By 1924 the Creole Jazz Band broke up due to the other members feeling that Oliver was not paying them properly for gigs and royalties on the recordings which everyone knew were hits. Only Louis Armstrong and Lil Hardin stayed on for awhile then they too departed.

By 1925 King Oliver had a new band, new name, and new gig. They were the Dixie Syncopators, and settled in for a two year engagement at the Plantation Café. He moved the band to New York in 1927, and landed in the Savoy Ballroom, turning down an offer from the new Cotton Club, which would be a mistake. This band he took into the studio in Chicago and between 1926 and 1928 he recorded sides for the Vocalion label. He toured the East coast briefly but they disbanded shortly after. His career would go into a period of sporadic gigs and recordings, with pick up bands and sidemen. By 1930 the Depression hit him pretty hard, he lost all his holdings in a bank collapse back in Chicago, and his health was starting to go bad. He had trouble with his teeth, which in turn made playing the trumpet difficult if not impossible for him. He did manage to record some more in New York during these years, using other trumpet players to play his parts. He kept a band somewhat together through 1935, playing the small clubs circuit, by 1937 he had lost all his teeth and his band, and was down and out. He wound up in Savannah, Georgia living in a rooming house, working odd jobs in a fruit stand and as janitor. He died sometime during the night of Apr. 10, 1938, of a cerebral hemorrhage.

There is no denying the fact that King Oliver left his mark on jazz. He took jazz from New Orleans to Chicago, California, and New York, and was instrumental in the spreading of this music to a broader audience. His glory days in Chicago with the Creole Jazz Band as performers and recording artists are monumental in their historical context. His influence lived on through Louis Armstrong who took this music around the world, and with him went a little piece of New Orleans and “Papa Joe” Oliver. Joe Oliver is one of the most important figures in early Jazz. When we use the phrase Hot Jazz, we are really referring to his style of collective improvisation (rather than solos).

He was the mentor and teacher of Louis Armstrong. Louis idolized him and called him Papa Joe. Oliver even gave Armstrong the first cornet that Louis was to own. Oliver was blinded in one eye as a child, and often played while sitting in a chair, or leaning against the wall, with a derby hat tilted so that it hid his bad eye.

Joe was famous for his using mutes, derbies, bottles and cups to alter the sound of his cornet. He was able to get a wild array of sounds out of his horn with this arsenal of gizmos. Bubber Miley is said to have been inspired by his sound.

Oliver started playing in New Orleans around 1908. At various times he was a member of several of the marching bands like The Olympia, The Onward Brass Band, The Original Superior and the Eagle Band. He often worked in Kid Ory's band and in 1917 he was being billed as “King” by the bandleader.

In 1919 he moved to Chicago with Ory and played in Bill Johnson's The Original Creole Orchestra at the Dreamland Ballroom. He toured with the band, but when he returned to Chicago in 1922 he started King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band at Lincoln Gardens (459 East 31st Street). Oliver imported his protégé Louis Armstrong from New Orleans. The band also included Johnny Dodds , Honore Dutrey, Lil Hardin and Baby Dodds among others. The group's 1923 sessions were a milestone in Jazz, introducing the playing of Louis Armstrong to the world.

Unfortunately the Creole Jazz Band gradually fell apart in 1924. Oliver went on to record a pair of duets with pianist Jelly Roll Morton that same year, and then took over Dave Peyton's band in 1925, renaming it the Dixie Syncopators. Oliver moved the band to New York in 1927, where he made some lousy business decisions, like turning down the regular gig at the Cotton Club, that went on to catapult Duke Ellington to fame.

Oliver had a life long sweet tooth. He was famous for his love of sugar sandwiches, This of course led to dental problems that made playing his cornet very painful. On top of that he was suffering from a bad back. In 1929 Luis Russell took over the Dixie Syncopators and changed the name to Luis Russell and his Orchestra. Oliver continued to record until 1931, but he was quickly becoming a forgotten name. He continued to tour the South with various groups, until he ran out of money and settled in Georgia, where he worked as a janitor in a poolroom up until his death in 1938.

Source: James Nadal

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/king-oliver-mn0000094639/biography

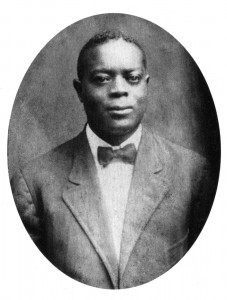

Joseph "King" Oliver

(1885-1938)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Joe "King" Oliver

was one of the great New Orleans legends, an early giant whose legacy

is only partly on records. In 1923, he led one of the classic New

Orleans jazz bands, the last significant group to emphasize collective

improvisation over solos, but ironically his second cornetist (Louis Armstrong) would soon permanently change jazz. And while Armstrong never tired of praising his idol, he actually sounded very little like Oliver; the King's influence was more deeply felt by Muggsy Spanier and Tommy Ladnier.

Although originally a trombonist, by 1905 Oliver was playing cornet regularly with various New Orleans bands. Gradually he rose to the top of the crowded local scene, and in 1917 he was being billed "King" by bandleader Kid Ory. A master of mutes, Oliver was able to get a wide variety of sounds out of his horn; Bubber Miley would later on be inspired by Oliver's expertise. In 1919, Oliver left New Orleans to join Bill Johnson's band at the Dreamland Ballroom in Chicago. By 1920, he was a leader himself and, after an unsuccessful year in California, King Oliver started playing regularly with his Creole Jazz Band at the Lincoln Gardens in Chicago. He soon sent for his protégé Louis Armstrong, and with clarinetist Johnny Dodds, trombonist Honore Dutrey, pianist Lil Harden, and drummer Baby Dodds as a core, Oliver had a remarkable band whose brilliance was only hinted at on records. As it is, the group's 1923 sessions far exceeded any jazz previously recorded; Oliver's three chorus solo on "Dippermouth Blues" has since been memorized by virtually every Dixieland trumpeter.

Unfortunately, the Creole Jazz Band gradually broke up in 1924. Oliver recorded a pair of duets with pianist Jelly Roll Morton but otherwise was off records that year. He took over Dave Peyton's band in 1925 and renamed it the Dixie Syncopators; Barney Bigard and Albert Nicholas were among the members. New recordings resulted (including "Snag It," which has a famous eight-bar passage by Oliver) but when the cornetist moved to New York in 1927, his music was behind the times and he made some bad business decisions (including turning down a chance to play regularly at the Cotton Club). Worse yet, his dental problems (caused partly by an early liking of sugar sandwiches) made playing cornet increasingly painful and, on many of his later recordings, Oliver is barely present (although he did a heroic job on 1929's "Too Late"). Pianist Luis Russell took over the Dixie Syncopators in 1929 and, although Oliver's last recordings (from 1931) are superior examples of hot dance music, he was quickly becoming a forgotten name. Unsuccessful tours in the South eventually left Oliver stranded there, working as a manager of a poolhall before his death at age 52.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/kingoliver

Although originally a trombonist, by 1905 Oliver was playing cornet regularly with various New Orleans bands. Gradually he rose to the top of the crowded local scene, and in 1917 he was being billed "King" by bandleader Kid Ory. A master of mutes, Oliver was able to get a wide variety of sounds out of his horn; Bubber Miley would later on be inspired by Oliver's expertise. In 1919, Oliver left New Orleans to join Bill Johnson's band at the Dreamland Ballroom in Chicago. By 1920, he was a leader himself and, after an unsuccessful year in California, King Oliver started playing regularly with his Creole Jazz Band at the Lincoln Gardens in Chicago. He soon sent for his protégé Louis Armstrong, and with clarinetist Johnny Dodds, trombonist Honore Dutrey, pianist Lil Harden, and drummer Baby Dodds as a core, Oliver had a remarkable band whose brilliance was only hinted at on records. As it is, the group's 1923 sessions far exceeded any jazz previously recorded; Oliver's three chorus solo on "Dippermouth Blues" has since been memorized by virtually every Dixieland trumpeter.

Unfortunately, the Creole Jazz Band gradually broke up in 1924. Oliver recorded a pair of duets with pianist Jelly Roll Morton but otherwise was off records that year. He took over Dave Peyton's band in 1925 and renamed it the Dixie Syncopators; Barney Bigard and Albert Nicholas were among the members. New recordings resulted (including "Snag It," which has a famous eight-bar passage by Oliver) but when the cornetist moved to New York in 1927, his music was behind the times and he made some bad business decisions (including turning down a chance to play regularly at the Cotton Club). Worse yet, his dental problems (caused partly by an early liking of sugar sandwiches) made playing cornet increasingly painful and, on many of his later recordings, Oliver is barely present (although he did a heroic job on 1929's "Too Late"). Pianist Luis Russell took over the Dixie Syncopators in 1929 and, although Oliver's last recordings (from 1931) are superior examples of hot dance music, he was quickly becoming a forgotten name. Unsuccessful tours in the South eventually left Oliver stranded there, working as a manager of a poolhall before his death at age 52.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/kingoliver

Joseph "King" Oliver

Joseph "King" Oliver

If we were to take all the major trumpet players in jazz, line them up

in chronological order, ask them who they listened to and were

influenced by, then send them down the long dark chute of jazz history,

they would run right smack dab into King Oliver.

Joseph Oliver was rumored to have been born on a plantation in Abend, Louisiana in 1885. His first instrument was the trombone, which by 1904 he was playing in the Onward Brass Band. He would continue with several bands, and started also playing the cornet. Being that New Orleans was a trumpet playing town, he had to work hard and long on his chops, and spent a lot of time learning to read music, which he became very good at, even in spite of having lost one eye. By 1910 he was leading his own band at Pete Lala’s the club where he started to garner a reputation, and where the name “King” was picked up, this due to his constant playing and able to obtain a sweet tone on his horn. He would go on to improve on his use of mutes and other means of getting unusual sounds out of his horn. There were also stories about trumpet battles in which he came out on top, having bested his local rivals.

By the year 1916, he teamed up with Edward “Kid” Ory on trombone, and started the Kid Ory and King Oliver Band, this was the best band in the city at the time, and they kept at it for another three years. In 1919 he wanted to leave New Orleans, and headed to Chicago where he was in two different bands one with clarinetist Lawrence Duhe, and another with bass player Bill Johnson. He stuck around Chicago until 1921 when he headed for California, with his new band the Creole Serenaders. They played in San Francisco for over a year, then he went to Los Angeles to play with Jelly Roll Morton, where they did some joint gigs around the city and caused quite a sensation. Returning to Chicago after his successful California tour, King Oliver was booked for an extended engagement at the Lincoln Gardens. The brothers Johnny and Baby Dodds, were part of the band at this time, and he sent to New Orleans for his protégé Louis Armstrong, whom had taken his place in the Kid Ory Band when Oliver left. Louis Armstrong was to be a lifelong friend to King Oliver, and kindly would refer to him as “Papa Joe”.

King Oliver and the Creole Serenaders also called the Creole Jazz Band, went on a two year tear of Chicago (1922-1924) while based out of the Lincoln Gardens, which was a lavish venue with a ballroom that could hold over one thousand dancers, it was the hottest club in town. Oliver was top cat in town, and he worked himself and his band very hard to stay there. The band was very tight, their sense of dynamics was well executed, and they had an extensive repertoire to draw from. The bands line up at this time was King Oliver and Louis Armstrong cornets, Johnny Dodds, clarinet, Honore Dutrey, trombone, Lil Hardin, piano, Bill Johnson bass and banjo, and Baby Dodds on drums. This band made over thirty recordings for the Gennett label in Richmond Indiana in 1923. These are historical jazz at its finest, and demonstrate the early stages of improvisation. There are also other recording done in Chicago that same year with some augmentation done in the line up, these were for the Okeh, Columbia, and Paramount labels.

Joseph Oliver was rumored to have been born on a plantation in Abend, Louisiana in 1885. His first instrument was the trombone, which by 1904 he was playing in the Onward Brass Band. He would continue with several bands, and started also playing the cornet. Being that New Orleans was a trumpet playing town, he had to work hard and long on his chops, and spent a lot of time learning to read music, which he became very good at, even in spite of having lost one eye. By 1910 he was leading his own band at Pete Lala’s the club where he started to garner a reputation, and where the name “King” was picked up, this due to his constant playing and able to obtain a sweet tone on his horn. He would go on to improve on his use of mutes and other means of getting unusual sounds out of his horn. There were also stories about trumpet battles in which he came out on top, having bested his local rivals.

By the year 1916, he teamed up with Edward “Kid” Ory on trombone, and started the Kid Ory and King Oliver Band, this was the best band in the city at the time, and they kept at it for another three years. In 1919 he wanted to leave New Orleans, and headed to Chicago where he was in two different bands one with clarinetist Lawrence Duhe, and another with bass player Bill Johnson. He stuck around Chicago until 1921 when he headed for California, with his new band the Creole Serenaders. They played in San Francisco for over a year, then he went to Los Angeles to play with Jelly Roll Morton, where they did some joint gigs around the city and caused quite a sensation. Returning to Chicago after his successful California tour, King Oliver was booked for an extended engagement at the Lincoln Gardens. The brothers Johnny and Baby Dodds, were part of the band at this time, and he sent to New Orleans for his protégé Louis Armstrong, whom had taken his place in the Kid Ory Band when Oliver left. Louis Armstrong was to be a lifelong friend to King Oliver, and kindly would refer to him as “Papa Joe”.

King Oliver and the Creole Serenaders also called the Creole Jazz Band, went on a two year tear of Chicago (1922-1924) while based out of the Lincoln Gardens, which was a lavish venue with a ballroom that could hold over one thousand dancers, it was the hottest club in town. Oliver was top cat in town, and he worked himself and his band very hard to stay there. The band was very tight, their sense of dynamics was well executed, and they had an extensive repertoire to draw from. The bands line up at this time was King Oliver and Louis Armstrong cornets, Johnny Dodds, clarinet, Honore Dutrey, trombone, Lil Hardin, piano, Bill Johnson bass and banjo, and Baby Dodds on drums. This band made over thirty recordings for the Gennett label in Richmond Indiana in 1923. These are historical jazz at its finest, and demonstrate the early stages of improvisation. There are also other recording done in Chicago that same year with some augmentation done in the line up, these were for the Okeh, Columbia, and Paramount labels.

King Oliver composed a lot of songs during this period, and many are jazz classics. “Snake Rag”, “Sugarfoot Stomp”, “West End Blues”, and “Dr Jazz”, the latter were covered by Jelly Roll Morton, and always in his songbook. He wrote a lot of blues, two of the better known are “Camp Meeting Blues”, and “Workingman’s Blues”. The blues he is most associated with is “Dippermouth Blues”, which is known for his soloing. He was a tough businessman as well and made sure his songs were copyrighted and he received his royalties.

By 1924 the Creole Jazz Band broke up due to the other members feeling that Oliver was not paying them properly for gigs and royalties on the recordings which everyone knew were hits. Only Louis Armstrong and Lil Hardin stayed on for awhile then they too departed.

By 1925 King Oliver had a new band, new name, and new gig. They were the Dixie Syncopators, and settled in for a two year engagement at the Plantation Café. He moved the band to New York in 1927, and landed in the Savoy Ballroom, turning down an offer from the new Cotton Club, which would be a mistake. This band he took into the studio in Chicago and between 1926 and 1928 he recorded sides for the Vocalion label. He toured the East coast briefly but they disbanded shortly after. His career would go into a period of sporadic gigs and recordings, with pick up bands and sidemen. By 1930 the Depression hit him pretty hard, he lost all his holdings in a bank collapse back in Chicago, and his health was starting to go bad. He had trouble with his teeth, which in turn made playing the trumpet difficult if not impossible for him. He did manage to record some more in New York during these years, using other trumpet players to play his parts. He kept a band somewhat together through 1935, playing the small clubs circuit, by 1937 he had lost all his teeth and his band, and was down and out. He wound up in Savannah, Georgia living in a rooming house, working odd jobs in a fruit stand and as janitor. He died sometime during the night of Apr. 10, 1938, of a cerebral hemorrhage.

There is no denying the fact that King Oliver left his mark on jazz. He took jazz from New Orleans to Chicago, California, and New York, and was instrumental in the spreading of this music to a broader audience. His glory days in Chicago with the Creole Jazz Band as performers and recording artists are monumental in their historical context. His influence lived on through Louis Armstrong who took this music around the world, and with him went a little piece of New Orleans and “Papa Joe” Oliver. Joe Oliver is one of the most important figures in early Jazz. When we use the phrase Hot Jazz, we are really referring to his style of collective improvisation (rather than solos).

He was the mentor and teacher of Louis Armstrong. Louis idolized him and called him Papa Joe. Oliver even gave Armstrong the first cornet that Louis was to own. Oliver was blinded in one eye as a child, and often played while sitting in a chair, or leaning against the wall, with a derby hat tilted so that it hid his bad eye.

Joe was famous for his using mutes, derbies, bottles and cups to alter the sound of his cornet. He was able to get a wild array of sounds out of his horn with this arsenal of gizmos. Bubber Miley is said to have been inspired by his sound.

Oliver started playing in New Orleans around 1908. At various times he was a member of several of the marching bands like The Olympia, The Onward Brass Band, The Original Superior and the Eagle Band. He often worked in Kid Ory's band and in 1917 he was being billed as “King” by the bandleader.

In 1919 he moved to Chicago with Ory and played in Bill Johnson's The Original Creole Orchestra at the Dreamland Ballroom. He toured with the band, but when he returned to Chicago in 1922 he started King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band at Lincoln Gardens (459 East 31st Street). Oliver imported his protégé Louis Armstrong from New Orleans. The band also included Johnny Dodds , Honore Dutrey, Lil Hardin and Baby Dodds among others. The group's 1923 sessions were a milestone in Jazz, introducing the playing of Louis Armstrong to the world.

Unfortunately the Creole Jazz Band gradually fell apart in 1924. Oliver went on to record a pair of duets with pianist Jelly Roll Morton that same year, and then took over Dave Peyton's band in 1925, renaming it the Dixie Syncopators. Oliver moved the band to New York in 1927, where he made some lousy business decisions, like turning down the regular gig at the Cotton Club, that went on to catapult Duke Ellington to fame.

Oliver had a life long sweet tooth. He was famous for his love of sugar sandwiches, This of course led to dental problems that made playing his cornet very painful. On top of that he was suffering from a bad back. In 1929 Luis Russell took over the Dixie Syncopators and changed the name to Luis Russell and his Orchestra. Oliver continued to record until 1931, but he was quickly becoming a forgotten name. He continued to tour the South with various groups, until he ran out of money and settled in Georgia, where he worked as a janitor in a poolroom up until his death in 1938.

Source: James Nadal

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/oliver-joseph-king-1885-1938/

Joseph “King” Oliver (1885-1938)

Mentor to Louis Armstrong and pioneer of what would become known as

the Harmon trumpet mute, Joe “King” Oliver was a key figure in the

first period of jazz history. His most significant ensemble, King

Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, was a live sensation and also the first black

New Orleans ensemble to gain recognition in the record industry.

Born in Louisiana in 1885, Joseph Oliver began his musical studies on

trombone, but switched to cornet as a teenager, touring with a brass

band at the turn of the century. Oliver worked in various marching and

cabaret bands in and around New Orleans, including bands led by Kid Ory

and Richard M. Jones, but moved north in 1918, settling in Chicago.

After a stay in California, Oliver returned to Chicago and formed his

own ensemble which included bassist Bill Johnson, trombonist Honore

Dutrey, clarinetist Johnny Dodds, his brother, drummer Warren “Baby”

Dodds, and pianist Lillian Hardin. King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, as

it was called, debuted on June 17, 1922 at the Lincoln Gardens Café in

Chicago. Shortly thereafter, Oliver wired New Orleans requesting a

second cornetist, his former apprentice Louis Armstrong. The new

ensemble was a hit, captivating audiences with its deep rhythmic

vitality, improvised polyphony, and unbelievable double-cornet breaks –

Oliver and Armstrong seemed to improvise on the spot, in perfect unison.

Stylistically, Oliver was not the exuberant soloist that Armstrong

would become; rather his innovations were largely in his use of trumpet

mutes and effects. Directly inspired by Oliver’s “wa-wa” sound, the

Harmon Company manufactured the now widely used Harmon mute. The

“jungle style” popularized by Bubber Miley in Duke Ellington’s orchestra

reflected Oliver’s mastery of the plunger, while the popularization of

the Harmon mute forged a direct link between Oliver and such modernist

trumpeters as Miles Davis and Harry Edison.

Oliver’s band set down the first significant body of records by black

jazzmen, although accounts from the period suggest that the recordings

only hinted at the power of the live group. Including several alternate

takes, thirty seven cuts survived the period, most recorded during

1923. Oliver’s most acclaimed solo, featured on the song “Dippermouth

Blues,” exemplified his uniquely vocalized style, and it was later

orchestrated by Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra as “Sugar Foot Stomp.”

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band prematurely disbanded in 1924, with

Louis Armstrong on his way to New York. Oliver recorded “Tom Cat Blues”

with pianist Jelly Roll Morton, and his new group, King Oliver’s Dixie

Syncopators, made additional records. Oliver moved to New York in 1927

and found regular work at the Savoy Ballroom, though he also supposedly

rejected a position at the Cotton Club, which instead famously went to

Duke Ellington.

Suffering from pyorrhea, a gum disease, Oliver’s abilities declined,

and he soon began delegating his solos to younger cornetists in his

ensemble. By 1935 Oliver could no longer play at all, though he would

continue to lead bands for two more years. Ailing and frustrated,

Oliver settled in Savannah, Georgia, where, having pawned his trumpet

and finest clothing, he maintained a small fruit stand and worked as a

pool-hall janitor. King Oliver died in 1938 from a heart attack, or, as

Louis Armstrong later suggested, a broken heart.

King Oliver

Copyright © 1999

Copyright © 1999

The first black band to be well documented on record was the Creole Jazz Band (1923) organized by Joe "King" Oliver (1885), although by that time Oliver too had already left New Orleans for Chicago (in 1918). King Oliver, who had developed his style at the cornet in Kid Ory's Brownskin Babies since 1914, cemented a group of talents that included Louis Armstrong, clarinetist Johnny Dodds, drummer Walter "Baby" Dodds, trombonist Honore Dutery, pianist Lil Hardin, bassist Bill Johnson. This classic line-up recorded Dippermouth Blues (april 1923), which contains Armstrong's first recorded solo, Armstrong's Weather Bird Rag (1923), Oliver's Sugar Foot Stomp (1923), and Canal Street Blues (1923), which are models of harmonious group playing despite the group improvisation: the piano, the drums and the bass provided the rhythmic foundation over which the cornets lead the melody against the petulant counterpoint of the clarinet and the bass ("tailgate") counterpoint of the trombone. Oliver basically perfected the collective improvisation of New Orleans' marching bands. Oliver also strove to produce sounds with his cornet that reflected his vision, thus becoming the first "sound artist" of jazz. His experiments continued with the Dixie Syncopators (1925-27), a larger band with three saxophones and a tuba (Barney Bigard on reeds, Luis Russell on piano, Albert Nicholas on clarinet):

WaWaWa (May 1926), for example, coined the "wah-wah" technique. Doctor Jazz (April 1926) became the most popular of his tunes.

Health problems contributed to his rapid decline. He died in 1938.

King Oliver

Joseph Nathan "King" Oliver (December 19, 1881 – April 10, 1938) was an American jazz cornet player and bandleader. He was particularly recognized for his playing style and his pioneering use of mutes in jazz. Also a notable composer, he wrote many tunes still played today, including "Dippermouth Blues", "Sweet Like This", "Canal Street Blues", and "Doctor Jazz". He was the mentor and teacher of Louis Armstrong. His influence was such that Armstrong claimed, "if it had not been for Joe Oliver, Jazz would not be what it is today."[1]

- Papa Joe: King Oliver and His Dixie Syncopators 1926–1928 (Decca, 1969)

- Louis Armstrong and King Oliver (Milestone, 1974)

- The New York Sessions (Bluebird, 1989)

- Sugar Foot Stomp The Original Decca Recordings (GRP, 1992)

- Dippermouth Blues (ASV Living Era, 1996)

- Great Original Performances 1923–1930 (Louisiana Red Hot, 1998)

- Sugar Foot Stomp Vocalion & Brunswick Recordings Vol. 1 (Frog, 2000)

- The Best of King Oliver (Blues Forever, 2001)

- The Complete Set: King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band (Retrieval, 2004)

- The Complete 1923 Jazz Band Recordings (Off the Record, 2006)

- "Snag it"

- Armstrong, Louis (2012). Satchmo: My Life In New Orleans. Ulan Press. ASIN B00AIGW6AS.

- "KID ORY, 86, DEAD; JAZZ TROMBONIST". New York Times. January 24, 1973. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Colin Larkin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. p. 919. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- Balliett, Whitney (1996). American Musicians II: Seventy-one Portraits in Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195095388.

- Barnhart, Scotty (2005). The World of Jazz Trumpet: A Comprehensive History and Practical Philosophy. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 21. ISBN 978-0634095276.

- Scott Yanow (1938-04-08). "King Oliver | Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- "Oliver, Joseph "King" (1885-1938) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". Blackpast.org. 1922-06-17. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- Gerler, Peter. "Joe 'King' Oliver". Encyclopedia of Jazz Musicians. jazz.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- There is disagreement on the date of Oliver's death. His grave marker says April 8 and this date appears in John Chilton's Who's Who in Jazz, as well as in his biography at AllMusic. However, in his biography at Portraits from Jelly Roll's New Orleans, by Peter Hanley, the author quotes an April 10 date from Oliver's Chatham County, Georgia, death certificate No. 8483.

- Williams, MT. King Oliver (Kings of Jazz). Barnes; Perpetua (1961), p. 31. ASIN: B0007ECVCE.

- King Oliver

- King Oliver discography at Discogs

- Joseph Oliver at RedHotJazz.com

- King Oliver's WWI Draft Registration Card and Essay

Biography

Life

Joseph Nathan Oliver was born in Aben, Louisiana, near Donaldsonville in Ascension Parish, and moved to New Orleans in his youth. He first studied the trombone, then changed to cornet. From 1908 to 1917 he played cornet in New Orleans brass bands and dance bands and in the city's red-light district, which came to be known as Storyville. A band he co-led with trombonist Kid Ory was considered one of the best and hottest in New Orleans in the late 1910s.[2] He was popular in New Orleans across economic and racial lines and was in demand for music jobs of all kinds.

According to an interview at Tulane University's Hogan Jazz Archive with Oliver's widow Estella, a fight broke out at a dance where Oliver was playing, and the police arrested him, his band, and the fighters. After Storyville closed, he moved to Chicago in 1918 with his wife and step-daughter, Ruby Tuesday Oliver.[3]

In Chicago, he found work with colleagues from New Orleans, such as clarinetist Lawrence Duhé, bassist Bill Johnson, trombonist Roy Palmer, and drummer Paul Barbarin.[4] He became leader of Duhé's band, playing at a number of Chicago clubs. In the summer of 1921 he took a group to the West Coast, playing engagements in San Francisco and Oakland, California.[3]

In 1922, Oliver and his band returned to Chicago, where they began performing as King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band at the Royal Gardens cabaret (later renamed the Lincoln Gardens). In addition to Oliver on cornet, the personnel included his protégé Louis Armstrong on second cornet, Baby Dodds on drums, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, Lil Hardin (later Armstrong's wife) on piano, Honoré Dutrey on trombone, and Bill Johnson on double bass.[3] Recordings made by this group in 1923 for Gennett, Okeh, Paramount, and Columbia demonstrated the New Orleans style of collective improvisation, also known as Dixieland, and brought it to a larger audience.

In the mid-1920s Oliver enlarged his band to nine musicians, performing under the name King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopators, and began using more written arrangements with jazz solos. In 1927 the band went to New York, but he disbanded it to do freelance jobs. In the later 1920s, he struggled with playing trumpet due to his gum disease, so he employed others to handle the solos, including his nephew Dave Nelson, Louis Metcalf, and Red Allen. He reunited the band in 1928, recording for Victor Talking Machine Company one year later. He continued with modest success until a downturn in the economy made it more difficult to find bookings. His periodontitis made playing the trumpet difficult. He quit playing music in 1937.[3]

Work and influence

As a player, Oliver took great interest in altering his horn's sound. He pioneered the use of mutes, including the rubber plumber's plunger, derby hat, bottles and cups. His favorite mute was a small metal mute made by the C.G. Conn Instrument Company, with which he played his famous solo on his composition the "Dippermouth Blues" (an early nickname for fellow cornetist Louis Armstrong). His recording "Wa Wa Wa" with the Dixie Syncopators can be credited with giving the name wah-wah to such techniques.

Oliver was also a talented composer, and wrote many tunes that are still regularly played, including "Dippermouth Blues," "Sweet Like This," "Canal Street Blues," and "Doctor Jazz."

Oliver performed mostly on cornet, but like many cornetists he switched to trumpet in the late 1920s. He credited jazz pioneer Buddy Bolden as an early influence, and in turn was a major influence on numerous younger cornet/trumpet players in New Orleans and Chicago, including Tommy Ladnier, Paul Mares, Muggsy Spanier, Johnny Wiggs, Frank Guarente and, the most famous of all, Armstrong. One of his protégés, Louis Panico (cornetist with the Isham Jones Orchestra), authored a book entitled The Novelty Cornetist, which is illustrated with photos showing some of the mute techniques he learned from Oliver.

As mentor to Armstrong in New Orleans, Oliver taught young Louis and gave him his job in Kid Ory's band when he went to Chicago. A few years later Oliver summoned him to Chicago to play with his band. Louis remembered Oliver as "Papa Joe" and considered him his idol and inspiration. In his autobiography, Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans, Armstrong wrote: "It was my ambition to play as he did. I still think that if it had not been for Joe Oliver, Jazz would not be what it is today. He was a creator in his own right."[1]

Hardships in later years, decline and death

Oliver's business acumen was often less than his musical ability. A succession of managers stole money from him, and he tried to negotiate more money for his band than the Savoy Ballroom was willing to pay – losing the job. He lost the chance of an important engagement at New York City's famous Cotton Club when he held out for more money; young Duke Ellington took the job and subsequently catapulted to fame.[5]

The Great Depression brought hardship to Oliver. He lost his life savings to a collapsed bank in Chicago, and he struggled to keep his band together through a series of hand-to-mouth gigs until the group broke up.

Oliver also had health problems, such as pyorrhea, a gum disease that was partly caused by his love of sugar sandwiches and it made it very difficult for him to play[6] and he soon began delegating solos to younger players, but by 1935, he could no longer play the trumpet at all.[7] Oliver was stranded in Savannah, Georgia, where he pawned his trumpet and finest suits and briefly ran a fruit stall, then he worked as a janitor at Wimberly's Recreation Hall (526-528 West Broad Street).[7]

Oliver died in poverty "of arteriosclerosis, too broke to afford treatment"[8] in a Savannah rooming house on April 8 or 10, 1938.[9] His sister spent her rent money to have his body brought to New York, where he was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. Armstrong and other loyal musician friends were in attendance.[10]

Honors and awards

Oliver was inducted as a charter member of the Gennett Records Walk of Fame in Richmond, Indiana in 2007.

Selected compilation discography

See also

References

External links

King Oliver & Louis Armstrong

“You

have to think beyond your time.” That’s how Wynton Marsalis described

the challenge of appreciating styles and sounds that precede one’s era.

His adage comes to mind whenever I listen to the groundbreaking music of

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band and other bands of the twenties and

thirties. “Dipper Mouth Blues” is a classic example of a landmark

recording that bears repeated listening. Recorded on April 7, 2923,

Oliver’s 22-year-old protege Louis Armstrong plays the cornet lead, and

Joe Oliver the three-chorus cornet solo. Composed by Oliver and

Armstrong, the tune itself is so good that it was re-invented by Don

Redman and Fletcher Henderson a few years later and became the big band

standard “Sugar Foot Stomp.” Oliver’s manner of effecting a “wah wah”

cry through a plunger mute became a ubiquitous element of jazz by the

mid-twenties and had a profound influence on the growling brass mystique

of Duke Ellington’s music, His solo is one of the most imitated of all

time, and is so paradigmatic of blues that it can be played now, on any

instrument, and still sound modern. Today is Joe “King” Oliver’s 131st

birthday anniversary. (The band pictured on the face of this YouTube

file for “Dippermouth Blues” is not the Creole Jazz Band of 1923, but

Oliver’s orchestra circa 1927.)

It’s recently come to light that there’s a 33-minute film of Louis

Armstrong in a recording studio in 1959. As it happens, it was shot in

Los Angeles during the making of his tribute album, Satchmo Plays King Oliver. Click here for

the background story on this wonderful discovery that’s now been added

to the huge Armstrong archive at the Louis Armstrong House Museum in

Queens.

https://64parishes.org/entry/king-oliver

Joseph “King” Oliver

Pioneering jazz trumpet and cornet player and band leader "King"; Oliver played an instrumental role in popularizing jazz outside of New Orleans and was an important mentor in the life of Louis Armstrong.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Joseph "King" Oliver.

A pioneering jazz trumpet and cornet player, bandleader Joseph “King” Oliver played an instrumental role in the popularization of jazz outside of New Orleans. Though born in Louisiana, Oliver spent much of his career in Chicago, where he established his legendary King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Initially, the band included Louis Armstrong, formerly Oliver’s student in New Orleans. Ironically, Armstrong’s success ultimately overshadowed his mentor’s reputation as a jazz pioneer. As both a teacher and a musician, however, Oliver played an important role in the early history of jazz.

Early Life and Influences

Joseph Nathan Oliver was born in Edgard, in St. John the Baptist Parish. Though the exact date has been in dispute, current evidence indicates that he was born on December 19, 1885. While Oliver was still young, his family moved to New Orleans. Orphaned in his early teens, he went to live with his half-sister, Victoria Davis. As a teenager and young adult, Oliver worked as a butler, but his passion was always music. He began playing as a child in a neighborhood brass band. As his musicianship progressed, Oliver performed in some of the most influential brass bands in turn-of-the-century New Orleans, including the Onward Brass Band, the Eagle Band (which included ex-members of Buddy Bolden’s group), and A. J. Piron’s Olympia Band.

Oliver’s musical skills placed him in a lineage of New Orleans trumpeters that included Buddy Bolden and Freddie Keppard. He developed a reputation as a strong player particularly adept at “freak” music, which involved using mutes to make the trumpet “talk” or imitate animals (creating, for example a “wah wah” sound). He was also well known for playing the blues in the “gut bucket” or “low down” style.

Oliver was a stern man, often quick to anger. But he also took a sincere interest in young musicians and always took the time to teach them proper technique. In was in this capacity that Oliver met Louis Armstrong. The two began a long musical relationship, with Oliver acting as a father figure to Armstrong. For the rest of his life, Armstrong spoke with deep admiration for Oliver. Oliver also taught Armstrong how to be a band leader, largely through example.

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band

In 1918 Oliver moved to Chicago to work in bassist William Manual “Bill” Johnson’s band. Oliver played with Johnson at the Royal Gardens Café. He performed with Lawrence Duhe at the Dreamland Café and in the White Sox Booster Band, which entertained audiences in the stands at baseball games. By 1920, Oliver was leading his own band at Dreamland. After performing briefly with Edward “Kid” Ory in California during 1921, he returned to Chicago to form his famous King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band in 1922. The band opened that year at Lincoln Gardens.

During the summer of 1922 Oliver sent for Armstrong to play second cornet. The band quickly gained a local reputation and made its first recordings on April 5 and 6, 1923, for Gennett Records. These recordings represented Oliver at his best and have attained legendary status in the history of jazz. The 1923 Creole Jazz Band included Oliver, Armstrong, Baby Dodds on drums, Honore Dutrey on trombone, Bill Johnson on bass, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, and Lillian Hardin on piano. Their first session produced nine tracks, including “Just Gone,” “Canal Street Blues,” “Weather Bird Rag,” “Snake Rag,” and “Dipper Mouth Blues.” Later that year, Johnny St. Cyr played banjo during a session that produced the lovely “Mabel’s Dream.” The hallmark of the Creole band sessions was the complex intertwining duets between Oliver and Armstrong, in which the student slowly surpassed the teacher. The band fell apart in late 1923, largely due to interpersonal problems among the members and financial issues. Armstrong’s increasing status led to some strain between the two, but Armstrong always deferred to Oliver on issues regarding the band. Lillian “Lil” Hardin, who had married Armstrong, pushed her husband to go to New York for better wages.

Later Career

Throughout the 1920s, Oliver frequently worked as a sideman on recording sessions for blues and popular singers. Some of these included Sara Martin, Victoria Spiver, Sippie Wallace, Texas Alexander, and the vaudeville duo Butterbeans and Susie. Oliver’s talent was particularly apparent when backing singers like Martin; his cornet performed a nearly perfect call-and-response pattern behind the singer. He also recorded duets with fellow New Orleanian Jelly Roll Morton.

In 1925 Oliver reorganized his band into a slightly larger group titled the Dixie Syncopators. This band attempted to conform to the growing demand for dance music rather than “hot” jazz. Oliver added a saxophone to his lineup and recorded popular tunes suggested by record executives. The recordings are uneven, though stellar solos and inspired segments can be found even in the poorer performances. Oliver struggled with the emerging big band sound and, in some ways, was eclipsed by Armstrong’s popularity. In 1927 he relocated to New York City. He took on more work as a sideman and appeared with various groups led by Clarence Williams. Oliver continued to front his own band, but his reputation was slowly slipping. He spent most of the 1930s touring the South and the Southwest.

By 1936 Oliver was headquartered in Savannah, Georgia. His health declined, and he experienced financial difficulties that began with the onset of the Great Depression. Though he remained optimistic about his future in music, by 1938 he was running a fruit stand and working as a janitor. He died on April 10, 1938, in Savannah and was buried in New York City.

Oliver’s reputation suffered over time, and jazz historians have often relegated him to the role of Armstrong’s mentor. Bad business decisions and difficulty adapting to changing tastes haunted him in later years. He was, however, a powerful player whose Creole Jazz Band recordings captured him at his best. He was also a hero to Louis Armstrong. In his autobiography Armstrong said, “It was my ambition to play as he did. I still think that if it had not been for Joe Oliver, Jazz would not be what it is today.”

Author

Kevin Fontenot

Suggested Reading

Armstrong, Louis. Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. New York, NY: DaCapo Press, 1986 (reprint).

Brothers, Thomas. Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2006.

Hahn, Roger. “The Forgotten King of Jazz.” Louisiana Cultural Vistas 19, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 56–61.

Williams, Martin. Jazz Masters of New Orleans. New York, NY: Macmillan Company, 1967.

___.King Oliver. New York, NY: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1960.

Wright, Laurie. “King” Oliver. Chigwell, UK: Storyville Publications, 1987.

https://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/program/sobbin-blues-joe-oliver-new-orleans-trumpet-king

Program : 264

Sobbin’ Blues:

Joe Oliver, New Orleans Trumpet King

Louis Armstrong called him 'Papa Joe’ and said that no other trumpet

player in New Orleans had the fire of Joe Oliver. By the early 1900s,

Oliver was “the King” of New Orleans trumpet men. And in 1920s Chicago

he proved himself to be a bandleader of extraordinary vision and a

highly capable composer.

Born upriver from New Orleans in 1885 Joseph Oliver belonged to a first generation of jazzmen that included Kid Ory, Sidney Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton. Even before World War I, these innovators brought the spirited, soulful sound of New Orleans jazz to national audiences in Chicago, New York and Los Angeles.

If Sidney Bechet was the first great soloist in jazz and Jelly Roll Morton its first great composer, then the genius of King Oliver lay in his skill at building and inspiring a band that reached the zenith of the art of the improvised jazz ensemble.

With outstanding sidemen like clarinetist Johnny Dodds, pianist/arranger Lil Hardin, and later the young prodigy Louis Armstrong, King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band played almost entirely in the classic New Orleans ensemble style. The entire group improvised together on tune after tune as a well-coordinated team. In Oliver's band, solos were limited to brief two-bar breaks—some of them spectacular Oliver-Armstrong cornet duets.

Oliver arrived at his own highly individual cornet style while he was making a name for himself in New Orleans dance halls and nightclubs. He is believed to be the first in jazz to make extensive use of mutes in order to achieve a vocal-like effect in his playing, at times taking on a "sobbing" quality.

This week on Riverwalk Jazz trumpeter and bandleader Duke Heitger joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band for Sobbin Blues: Joe Oliver, “The King” of New Orleans Trumpet. Together they perform classic tunes King Oliver first recorded in the early 1920s, including W.C. Handy's "Aunt Hagar's Blues" and Oliver's own compositions "Camp Meeting Blues" and "Working Man Blues."

Photo credit for Home Page: Joe Oliver. Courtesy Red Hot Jazz Archive.

Born upriver from New Orleans in 1885 Joseph Oliver belonged to a first generation of jazzmen that included Kid Ory, Sidney Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton. Even before World War I, these innovators brought the spirited, soulful sound of New Orleans jazz to national audiences in Chicago, New York and Los Angeles.

If Sidney Bechet was the first great soloist in jazz and Jelly Roll Morton its first great composer, then the genius of King Oliver lay in his skill at building and inspiring a band that reached the zenith of the art of the improvised jazz ensemble.

With outstanding sidemen like clarinetist Johnny Dodds, pianist/arranger Lil Hardin, and later the young prodigy Louis Armstrong, King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band played almost entirely in the classic New Orleans ensemble style. The entire group improvised together on tune after tune as a well-coordinated team. In Oliver's band, solos were limited to brief two-bar breaks—some of them spectacular Oliver-Armstrong cornet duets.

Oliver arrived at his own highly individual cornet style while he was making a name for himself in New Orleans dance halls and nightclubs. He is believed to be the first in jazz to make extensive use of mutes in order to achieve a vocal-like effect in his playing, at times taking on a "sobbing" quality.

This week on Riverwalk Jazz trumpeter and bandleader Duke Heitger joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band for Sobbin Blues: Joe Oliver, “The King” of New Orleans Trumpet. Together they perform classic tunes King Oliver first recorded in the early 1920s, including W.C. Handy's "Aunt Hagar's Blues" and Oliver's own compositions "Camp Meeting Blues" and "Working Man Blues."

Photo credit for Home Page: Joe Oliver. Courtesy Red Hot Jazz Archive.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2006

https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/literature-and-arts/music-popular-and-jazz-biographies/king-oliver

Became Musical Star in New Orleans

Started Own Band in Chicago

Recorded with his Creole Jazz Band

Split From Armstrong, Ended Recording Career

Ended Life in Poverty

Selected works

Sources

Joe “King” Oliver was one of the most important figures in jazz. As an influential cornet player and leader of one of the classic early New Orleans jazz bands, Oliver is a link between the earliest New Orleans incarnation of jazz and the achievements of a generation of brass players who developed their style in Chicago in the 1920s, including Oliver’s protege, Louis Armstrong. “By almost any measure—historical, musical, biographical,” wrote critic Ted Gioia in The History of Jazz, “he stands out as a seminal figure in the history of the music.”

Joseph Oliver was born on May 11, 1885. Some accounts establish his place of birth as a plantation near Donaldsville, Louisiana, where his mother worked as a cook, while others cite a house on Dryades Street in New Orleans. Little is known of his early years, and of his father. His mother, who may have worked as a servant for various white families, moved her children to several new addresses in New Orleans during Oliver’s childhood. His older half-sister, Victoria Davis, took charge of him when their mother died in 1900.

Oliver found employment as butler to a white family in New Orleans when he was about seventeen, a job he kept for the next nine years. He was already active as a musician. Around 1899 he joined a children’s brass band, formed by a Walter Kenehan, and performed on the trombone, and later the cornet, at funerals and parades. One of his eyes was damaged during a childhood accident, earning him the early nicknames of “Bad Eye” and “Monocles,” and he often played with a hat tilted over the eye to disguise it.

Career: Jazz musician, 1899-1938; butler, 1902-11; Olympia band, leader and coronetist, 1916-17; King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, 1922-25; recording artist 1923-31; Dixie Syncopators and other bands, leader and coronetist, 1926-29; Savoy Ballroom and other New York venues, bandleader and entertainer, 1927-31; toured in the South, 1931-35; janitor, 1935-38.

The young Louis Armstrong was one of Oliver’s most avid fans, spending time at Oliver’s house and enjoying the cooking of Oliver’s wife, Stella. Oliver, known for his good nature and generosity, became a father figure to his young disciple, offering musical advice and professional support, and even giving him one of his old cornets. “I prized that horn and guarded it with my life,” said Armstrong, quoted in Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. Oliver, he said, “was always willing to come to my rescue when I needed someone to tell me about life.”

In 1917 city officials closed the bars and brothels of Storyville. Oliver, like hundreds of New Orleans musicians, decided to head north to lucrative opportunities in Chicago. When Armstrong was asked to replace Oliver in Kid Ory’s band, he was excited “to have a try at taking that great man’s place,” as he remembered in “Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans,” reprinted in Literary New Orleans. In his first gig with Ory, Armstrong concentrated on “doing everything just exactly the way I’d heard Joe Oliver do it,” including wearing a bath towel around his neck. In an era of great players like Bunk Johnson and the fabled Buddy Bolden, creators of a new musical idiom, “Papa Joe” Oliver, according to Armstrong, “was the sweetest and most creative.”

Oliver’s new line-up “made momentous musical sense,” according to critic Gary Giddons in his book Visions of Jazz. “The band was a sensation, and its most widely noted effects were double-cornet breaks, seemingly improvised on the spot, yet played in perfect unison.” Ted Gioia, in The History of Jazz, suggested that the Creole Jazz Band lacked the finesse of some New Orleans-bred, Chicago-based musical ensembles, but “its hot, dirty, swinging sound comes closest to the essence of the jazz experience.” Other musicians crowded into Lincoln Gardens to hear them play.

When he invited Armstrong to join his band, Oliver was almost past his prime as a soloist, although his playing was still so powerful he was reputed to blow his horns to pieces every few months. By this time, Oliver’s achievements as an individual musician, Giddon contended in Visions of Jazz, were secondary to his great gift as a band leader. Noted for his self-discipline as a player (he claimed to have spent ten years refining his tone) and his tough style of leadership, Oliver made strict demands of professionalism of his band. Driving “an ensemble that specialized in improvised polyphony,” wrote Giddons, Oliver “created a music that is at once the apex of traditional New Orleans style and so far beyond its norm that there is little to compare with it.”

But there is no doubt that Oliver left an important legacy as a player. Famous for his expressive, blues-inflected style of playing and skill at tonal improvisation, including an innovative use of mutes to create a ‘wa-wa’ sound and other theatrical effects, Oliver’s bold New Orleans sound influenced a whole generation of jazz musicians. “His throaty, vocal sound inspired many imitators,” said Gioia, “and represented, both conceptually and historically, a meeting ground of earlier and later jazz styles.”

But on April 5, 1923, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band made its first recordings in the Gennett recording company’s studio in Richmond, Indiana. The band—Oliver and Armstrong on cornet, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, Honore Dutrey on trombone, Lil Hardin on piano, Bill Johnson on banjo, and Baby Dodds on drums—spent two days in a hot room with poor acoustics, playing into a giant megaphone. These groundbreaking recordings included a show-stealing Armstrong in his first significant recorded solo (on the Oliver composition, “Chimes Blues”). Oliver’s own plunger-muted solo in “Dippermouth Blues,” was much imitated; under the title “Sugar Foot Stomp,” the song became a jazz standard.

Many of Oliver’s own compositions made high technical demands on musicians: Walter Allen and Brian Rust, in King Oliver, suggested that it is significant that, except for “Dipper Mouth Blues,” “none of his early numbers were ever recorded by his contemporaries.” His biggest hit, “Snag It,” was written in the mid-19205, and he co-wrote a number of popular tunes with his nephew, Dave Nelson, later in the decade, many of which were recorded for Victor. Popular versions of some of his songs were recorded by other artists, like Jelly Roll Morton (“Doctor Jazz”), Fletcher Henderson (“Snag It”), and Armstrong (“West End Blues”).

At Hardin’s urging, Armstrong left Oliver early in 1925, moving to New York at Fletcher Henderson’s invitation. When he returned to Chicago, it was to star billing at the Dreamland Café, across the street from Oliver’s new theater, the Plantation Café. The two musicians briefly reunited in 1926, after Armstrong separated from Hardin, but they were no longer close friends. Armstrong’s fame had eclipsed that of the man he called “Papa Joe.”

In the early years of the Depression, with clubs closing and many musicians out of work, Oliver realized he needed a new professional strategy. He formed a new band, the Dixie Syncopators, in 1926 and together they made a number of popular dance recordings for the Vocalion ‘race’ series, as Oliver tried to adapt his performance style to the emerging big band era.

Oliver, already stricken with the severe gum disease that would end his playing life, was forced to delegate many of the cornet solos. In 1927 he moved his band to New York—in Armstrong’s opinion, too late in his career. He worked at the Savoy Ballroom and recorded for the Victor Company in 1929 and 1930. But he lost his savings when a Chicago bank failed and made the error of turning down work at the Cotton Club in 1927 (an engagement that made Duke Ellington famous) because he thought the pay too low. In 1931 Victor canceled his recording contract and Oliver made his last known recordings for Brunswick and Vocalion, before forming a new band to take on the road.

For the last few years of his life, Oliver lived in a boarding house and worked fifteen hours a day as a janitor at a pool hall in Savannah. He had separated from his wife, Stella, many years earlier. Letters to his sister testify to his demoralization and extreme poverty, as well as his stubborn pride: he refused to appeal for help to the musical community, and kept hoping to save enough money to return to New York.

Discontinuing medical treatment for his high blood pressure because of the cost, Oliver fell into deep decline and died of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 8, 1938. He was just 52 years old. His sister used rent money to pay for his body to be shipped to New York for a funeral attended by many musicians, including Clarence Williams and Louis Armstrong, who always maintained that Oliver died of a broken heart. He was buried without a headstone at Woodlawn cemetery in the Bronx. Despite his neglect by the jazz world during the last years of his life, almost all of Oliver’s recordings are available on reissues, testimony to his significant musical legacy.

(With King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band) “Dipper Mouth Blues,” Gennett, 1923.

(With King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band) “Chattanooga Stomp,” Columbia, 1923.

(With King Oliver’s Jazz Band) “Sweet Baby Doll,” OKeh, 1923.

(With King Oliver’s Jazz Band) “The Southern Stomps,” Paramount, 1923.

(With King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopators) “Doctor Jazz,” Vocalion/Brusnwick, 1926.

(With King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopators) “Snag It,” Vocalion/Brunswick, 1926.

(With King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopators) “West End Blues,” Vocalion/Brunswick, 1926.

(With King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopators) “Showboat Shuffle,” Vocalion/Brunswick, 1927.

(With King Oliver and his Orchestra) “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Victor, 1929.

(With King Oliver and his Orchestra) “Stop Crying,” Victor, 1930.

(With King Oliver and his Orchestra) “I’m Crazy ’Bout My Baby,” Brunswick, 1931.

(With the Chocolate Dandies) “One More Time,” Vocalion, 1931.

Bergreen, Laurence, Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life, Broadway Books, 1997, pp. 105, 106, 121, 176, 203, 210, 213, 232-234, 261, 388-392.

Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 1-2: To 1940, American Council of Learned Societies, 1944-1958.

Giddons, Gary, Visions of Jazz: the First Century, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 77-83.

Gioia, Ted, The History of Jazz, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 47-48, 50, 52.

Long, Judy, ed. Literary New Orleans, Hill Street Press, 1999, pp. 142-143.

Williams, Martin, King Oliver, A.S. Barnes and Company, 1960, pp. 8-9, 28-33.

“Joe ‘King’ Oliver,” PBS, www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_oliverJoe_king.htm (August 22, 2003).

“Joe Oliver,” Red Hot Jazz, www.redhotjazz.com/kingo.html (August 22, 2003).

“Joseph Oliver,” Biography Resource Center, www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC (August 22, 2003).

“King Oliver,” All Music Guide, www.allmusic.com/(August 22, 2003).

“King Oliver,” Froggy’s New Orleans Jazz, www.geocities.com/infrogmation/JOliver.html (October 12, 2003).

—Paula J.K. Morris

The King of Storyville

Armstrong Arrives

The Descent of the King

Selected discography

Sources

Billed as the “World’s Greatest Cornetist,” Joe “King” Oliver reigned as the premier trumpeter of jazz during the early 1920s. The famed musical mentor of Louis Armstrong, Oliver is perhaps best remembered for bringing the young New Orleans hornman to Chicago in 1922. With Armstrong on second cornet, Oliver performed double-cornet breaks that sent shock waves through the jazz world. Years later, Armstrong paid tribute to his elder, noting, as quoted in the liner notes to King Oliver “Papa Joe” (1926–1928), that “if it had not been for Joe Oliver, jazz would not be what it is today.”

Joseph “King” Oliver was born around New Orleans, Louisiana, on May 11, 1885. Over the next several years, his family moved a number of times, primarily throughout New Orleans’s Garden District, a section filled with large antebellum homes and high-walled courtyards. After the death of his mother in 1900, Oliver was raised by his older half-sister, Victoria Davis. He first performed on cornet with a children’s brass band under the direction of a man named Kenhen, who frequently took the ensemble on out-of-state tours. While on the road with the band, Oliver got into a fight that left him with a noticeable scar over his left eye. (The white cataract on the same eye was supposedly caused by a childhood accident.)

Like most New Orleans musicians in the early twentieth century, Oliver could not support himself solely by music. While working as a butler, his employers allowed him to hire an occasional substitute so that he could play with local brass bands that performed at picnics, funerals, and dances in the area. For over a decade, he appeared with a number of march-oriented brass bands, including the Eagle Band, the Onward Brass Band, the Melrose Brass Band, the Magnolia Band, the Original Superior, and Allen’s Brass Band. As a member of these ensembles, Oliver established connections with a number of musicians, many of whom, like fellow Melrose bandmate Honoré Dutrey, would become members of his famous Chicago-based group.

Cornetist, trumpeter. Began playing in children’s brass band; while a youngster worked as a yard boy and later as a butler; performed with a number of New Orleans brass bands, including the Eagle, Onward, Melrose, Magnolia, and Original Superior; played at nightspots in and around Storyville, LA; went to Chicago with Jimmy Noone to join bassist Bill Johnson’s band and doubled in a band led by Lawrence Duhé, 1918; led own band at the Dreamland, 1920; took his band to San Francisco to play the Pergola Dance Pavilion, 1921, and also played gigs in Los Angeles; returned to Chicago in April of 1922 and led own Creole Jazz Band at the Lincoln Gardens; recruited Louis Armstrong to play in the band, 1922; briefly joined Dave Peyton’s Symphonic Syncopators, 1924; led his Dixie Syncopators at Plantation Cafe, 1925–27; performed on recordings with Clarence Williams, 1928; formed another band and toured, 1930–37.

named Edmond Souchon recalled seeing King Oliver outside the Big 25: “I’ll never forget how big and tough he looked! His brown derby was tilted low over one eye, his shirt collar was open at the neck, and a bright red undershirt peeked out at the V. Wide suspenders held up an expanse of trousers of unbelievable width.”

Oliver’s musical reputation soon began to match his imposing stature, and by 1917 he became a formidable figure on the New Orleans music scene. His forceful melodic phrasing and use of assorted trumpet mutes earned him the title of “King.” In his autobiography Pops Foster, New Orleans bassist Foster related how “Joe had all kinds of things he put on his horn. He used to shove a kazoo in the bell to give it a different effect.” Because of Oliver’s unorthodox use of objects to mute his horn, trumpeter Mutt Carey, as quoted in Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya, referred to Oliver as a “freak trumpeter” who “did most of his playing with cups, glasses, buckets, and mutes.”

Along with his passion for music, Oliver possessed an equally voracious appetite for food. His diet consisted of sugar sandwiches made from whole loaves of bread, which he chased down with a pot of tea or a pitcher of sugar water. Foster recalled how Oliver would eat six hamburgers and a quart of milk in one sitting or how— with one dip of a finger—he would pull out an entire pouch of tobacco and chew it while blowing his horn. Affectionately known as “Papa Joe” by musicians, he was also called “Tenderfoot” because of the painful corns that covered his feet.

In 1918 bassist Bill Johnson invited Oliver to join his band at Chicago’s Royal Gardens. He accepted the offer and left for Chicago with clarinetist Jimmy Noone. Housed in a large building on 31st Street, the Royal Gardens—soon to be renamed the Lincoln Gardens-had an upstairs balcony and a spotlighted crystal chandelier that reflected on the dance floor. While playing the Gardens, Oliver doubled in another group at the Dreamland Cafe led by Lawrence Duhé. By 1920 he was leading King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band at the Dreamland and playing a second engagement from one till six in the morning at a State Street gangster hangout. During the following year, his band played a brief engagement at the Pergola Dance Pavilion in San Francisco. From the Pergola, the band traveled southward to perform in Los Angeles.

“From the testimony of musicians (and fans) who heard the 1922–1924 Oliver band live,” wrote Dan Morganstern in the liner notes to Louis Armstrong: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1923–1934, “its most potent attraction was the unique cornet team.” Though Oliver and Armstrong’s double-breaks appeared to exhibit a natural sense of spontaneity and interplay, they “were in fact worked out in a most ingenious way: at a given point in the preceding collective band chorus, Oliver would play what he intended to use as his part in the break, and Armstrong, lightning-quick on the up-take, would memorize it and devise his own second part—which always fit to perfection.” As Armstrong explained in his autobiography, Louis Armstrong —A Self Portrait, “Whatever Mister Joe played, I just put notes to it trying to make it sound as pretty as I could. I never blew my horn over Joe Oliver at no time unless he said, ‘Take it!’ Never. Papa Joe was a creator—always some little idea—and he exercised them beautifully.”

On March 31, 1923, the Oliver Band entered the Gennet Recording Company Studios in Richmond, Indiana. Along with trumpeter Armstrong, clarinetist Johnny Dodds, pianist Lil Hardin, bassist Bill Johnson, and drummer Baby Dodds, Oliver created some of the most memorable sides in jazz history. The Gennet session produced several classics, including the legendary “Dipper Mouth Blues,” a title taken from Armstrong’s nickname. In describing the Gennet sides, Martin Williams wrote in Jazz Masters of New Orleans, “They do not have merely historical or documentary interest, and their emotional impact cuts across the years.” Williams added, “The most immediately impressive characteristic of the music of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band is its unity, the wonderful integration of parts with which the individual players contribute to a dense, often hetero-phonic texture of improvised melodies. The tempos are right, the excitement of the music is projected with firmness and ease, and the peaks and climaxes come with musical excitement rather than personal frenzy, with each individual in exact control of what he is about.”

In 1924 Oliver’s band toured the Orpheum Theater circuit throughout the Midwest, including stops in Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Urged on by his then-wife and fellow Oliver bandmember Lil Hardin, Armstrong left the group in June to join the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra. Then, on Christmas Eve of the same year, the burning of the Lincoln Gardens resulted in the disbanding of Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Oliver took a temporary job at the Plantation Club with Dave Peyton’s Symphonic Syncopators. Soon thereafter, he brought a number of talented New Orleans musicians— including reedmen Albert Nicholas and Barney Bigard, drummer Paul Barbarin, and trumpeter Tommy Ladnier—into Peyton’s band. By 1925 Oliver had taken over the band. Billed as the Dixie Syncopators, the band was reorganized; with the addition of three saxophones, the Syncopators began a two-year job at the Plantation Club.

Despite the band’s wealth of talent, the Dixie Syncopators experienced problems as they expanded. After 1925 the group relied primarily on stock arrangements. In the studio, the larger band—once able to rely on intuitive group discipline—faced the problem of allowing for more individuality among members. As Williams observed in Jazz Masters of New Orleans, “The Syncopators’ rhythms are usually heavy, the horns and percussion are often unsure, the ensembles are sometimes sloppy. One passage will swing beautifully, the next will flounder.” On record the band did experience occasional moments of brilliance, especially with the presence of saxophonist-arranger Billy Paige, who contributed to the 1926 sides “Too Bad” and “Snag It.”

After the police closed down the Plantation Club in 1927, Oliver and his band played short engagements in Milwaukee and Detroit. These appearances were followed by a two-week stint at the Savoy Ballroom in New York City. Though the newspapers hailed Oliver’s visit, the Syncopators did not take the city by storm. The band received a warm reception, but Oliver’s invasion of the East had come too late. After the arrival of Armstrong and others, New York City’s music scene began to lose interest in authentic New Orleans music. Though he was offered a job at the soon-to-be famous nightspot the Cotton Club, Oliver, dissatisfied with the financial arrangement, declined the engagement. The position went to a young pianist named Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington.

After the visit to New York, Oliver sustained himself and his bands with money from a recording contract he had established with the Victor company in 1928. Unlike his earlier label, Vocalion-Brunswick, which allowed him a great deal of creative freedom, Victor limited Oliver’s creative input. By 1930 the contract with Victor had expired, and the group disbanded.

Oliver’s body was taken to New York for burial, where his stepsister spent her rent money to pay for the funeral— an occasion that attracted Armstrong and a number of musicians who never forgot their debt to Papa Joe Oliver.

With time, perhaps Oliver’s musical legacy will overshadow the story of his tragic downfall and early death— and once again bring recognition to a man who ruled New Orleans and Chicago’s South Side as the king of the jazz trumpet. Though his recordings remain crude by today’s standards, they represent moving portraits of sound that provide the listener with audible passages into American cultural history. As musician and writer Gunther Schuller wrote in Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development, “Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band represents one of jazz’s great achievements. It is worthy of our close attention, not only for its own merits, but for the lessons it can still teach us.”

Jazz Classics in Digital Stereo: Vol. 1, New Orleans, Smithsonian Folkways.

Jazz Classics in Digital Stereo: Vol. 2, Chicago, Smithsonian Folkways.

King Oliver “Papa Joe” (1926–1928), Decca.

Louis Armstrong and King Oliver, Milestone Records.

RCA-Victor Jazz: The First Half Century—The Twenties through the Sixties, RCA.

The Riverside History of Classic Jazz, Riverside.

Sound of the Trumpets, GRP Records.

Foster, Pops, Pops Foster: The Autobiography of a New Orleans Jazzman As Told to Tom Stoddard, University of California Press, 1971.

Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya: The Story of Jazz As Told by the Men Who Made It, edited by Nat Shapiro and Nat Hentoff, Dover Publications, 1955.

Jazz Panorama: From the Birth to Dixieland to the Latest “Third Stream” Innovations —The Sounds of Jazz and the Men Who Make Them, edited by Martin Williams, Collier Books, 1964.

Schuller, Gunther, Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development, Oxford University Press, 1986.

Selections from the Gutter: Jazz Portraits from the “Jazz Record,” edited by Art Hodes and Chadwick Hansen, 1977.

Williams, Martin, Jazz Masters of New Orleans, Macmillan, 1967.

Williams, Kings of Jazz: King Oliver, A. S. Barnes and Company, 1961.

Additional information for this profile was obtained from the liner notes to Louis Armstrong: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1923–1934, by Dan Morganstern, Columbia/Legacy, 1994, and the notes to King Oliver “Papa Joe” (1926–1928), Decca, by Panassté Hugues.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/literature-and-arts/music-popular-and-jazz-biographies/king-oliver

Joe “King” Oliver 1885–1938

Jazz musician, composer, bandleaderBecame Musical Star in New Orleans

Started Own Band in Chicago

Recorded with his Creole Jazz Band

Split From Armstrong, Ended Recording Career

Ended Life in Poverty

Selected works

Sources

Joe “King” Oliver was one of the most important figures in jazz. As an influential cornet player and leader of one of the classic early New Orleans jazz bands, Oliver is a link between the earliest New Orleans incarnation of jazz and the achievements of a generation of brass players who developed their style in Chicago in the 1920s, including Oliver’s protege, Louis Armstrong. “By almost any measure—historical, musical, biographical,” wrote critic Ted Gioia in The History of Jazz, “he stands out as a seminal figure in the history of the music.”

Joseph Oliver was born on May 11, 1885. Some accounts establish his place of birth as a plantation near Donaldsville, Louisiana, where his mother worked as a cook, while others cite a house on Dryades Street in New Orleans. Little is known of his early years, and of his father. His mother, who may have worked as a servant for various white families, moved her children to several new addresses in New Orleans during Oliver’s childhood. His older half-sister, Victoria Davis, took charge of him when their mother died in 1900.

Oliver found employment as butler to a white family in New Orleans when he was about seventeen, a job he kept for the next nine years. He was already active as a musician. Around 1899 he joined a children’s brass band, formed by a Walter Kenehan, and performed on the trombone, and later the cornet, at funerals and parades. One of his eyes was damaged during a childhood accident, earning him the early nicknames of “Bad Eye” and “Monocles,” and he often played with a hat tilted over the eye to disguise it.

Became Musical Star in New Orleans

Oliver played in a number of marching bands and, around 1910, started appearing in the nightclubs of New Orleans’ red-light district, Storyville, the vibrant heart of the city’s musical life. These early years of jazz saw intense competition in the raucous neighborhood’s numerous clubs, cabarets and gambling den. As a performer at the Abadie Cabaret, Oliver attracted big audiences, and soon took over the job of his rival, Freddie Keppard, at Pete Lala’s saloon club, a notorious meeting place for pimps, prostitutes and musicians. Oliver became leader of the Olympia Band around 1916 and also began playing with acclaimed trombonist and band leader Kid Ory, who claimed to have given Oliver the nickname of “King” as a tribute to his musical prowess.

At a Glance…

Born on May 11, 1885, in New Orleans, LA; died on April 8, 1938 in Savannah, GA; married Stella Oliver.

Career: Jazz musician, 1899-1938; butler, 1902-11; Olympia band, leader and coronetist, 1916-17; King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, 1922-25; recording artist 1923-31; Dixie Syncopators and other bands, leader and coronetist, 1926-29; Savoy Ballroom and other New York venues, bandleader and entertainer, 1927-31; toured in the South, 1931-35; janitor, 1935-38.

The young Louis Armstrong was one of Oliver’s most avid fans, spending time at Oliver’s house and enjoying the cooking of Oliver’s wife, Stella. Oliver, known for his good nature and generosity, became a father figure to his young disciple, offering musical advice and professional support, and even giving him one of his old cornets. “I prized that horn and guarded it with my life,” said Armstrong, quoted in Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. Oliver, he said, “was always willing to come to my rescue when I needed someone to tell me about life.”

In 1917 city officials closed the bars and brothels of Storyville. Oliver, like hundreds of New Orleans musicians, decided to head north to lucrative opportunities in Chicago. When Armstrong was asked to replace Oliver in Kid Ory’s band, he was excited “to have a try at taking that great man’s place,” as he remembered in “Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans,” reprinted in Literary New Orleans. In his first gig with Ory, Armstrong concentrated on “doing everything just exactly the way I’d heard Joe Oliver do it,” including wearing a bath towel around his neck. In an era of great players like Bunk Johnson and the fabled Buddy Bolden, creators of a new musical idiom, “Papa Joe” Oliver, according to Armstrong, “was the sweetest and most creative.”

Started Own Band in Chicago