SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER THREE

MAX ROACH

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BEN WEBSTER

(September 7-13)

GENE AMMONS

(September 14-20)

TADD DAMERON

(September 21-27)

ROY ELDRIDGE

(September 28-October 4)

MILT JACKSON

(October 5-11)

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN

(October 12-18)

GRANT GREEN

(October 19-25)

ROY HARGROVE

(October 26-November 1)

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT

(November 2-8)

BLUE MITCHELL

(NOVEMBER 9-15)

BOOKER ERVIN

(November 16-22)

LUCKY THOMPSON

(November 23-29)

Lucky Thompson

(1924-2005)

Artist Biography by Jason Ankeny

Born in Columbia, SC, on June 16, 1924, tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson

bridged the gap between the physical dynamism of swing and the cerebral

intricacies of bebop, emerging as one of his instrument's foremost

practitioners and a stylist par excellence. Eli Thompson's

lifelong nickname -- the byproduct of a jersey, given him by his

father, with the word "lucky" stitched across the chest -- would prove

bitterly inappropriate: when he was five, his mother died, and the

remainder of his childhood, spent largely in Detroit, was devoted to

helping raise his younger siblings. Thompson

loved music, but without hope of acquiring an instrument of his own, he

ran errands to earn enough money to purchase an instructional book on

the saxophone, complete with fingering chart. He then carved imitation

lines and keys into a broom handle, teaching himself to read music years

before he ever played an actual sax. According to legend, Thompson

finally received his own saxophone by accident -- a delivery company

mistakenly dropped one off at his home along with some furniture, and

after graduating high school and working briefly as a barber, he signed

on with Erskine Hawkins' 'Bama State Collegians, touring with the group until 1943, when he joined Lionel Hampton and settled in New York City.

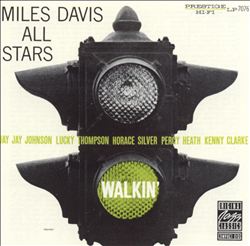

Thompson

returned to New York in 1947, leading his own band at the famed Savoy

Ballroom. The following year, he made his European debut at the Nice

Jazz Festival, and went on to feature on sessions headlined by Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis (the seminal Walkin'). Backed by a group dubbed the Lucky Seven that included trumpeter Harold Johnson and altoist Jimmy Powell, Thompson

cut his first studio session as a leader on August 14, 1953, returning

the following March 2. For the most part he remained a sideman for the

duration of his career, however, enjoying a particularly fruitful

collaboration with Milt Jackson that yielded several LPs during the mid-'50s. But many musicians, not to mention industry executives, found Thompson

difficult to deal with -- he was notoriously outspoken about what he

considered the unfair power wielded over the jazz business by record

labels, music publishers, and booking agents, and in February 1956 he

sought to escape these "vultures" by relocating his family to Paris. Two

months later he joined Stan Kenton's French tour, even returning to the U.S. with Kenton's group, but he soon found himself blacklisted by Louis Armstrong's

manager, Joe Glaser, after a bizarre conflict with the beloved jazz

pioneer over which musician should be the first to leave their plane

after landing. Without steady work, he returned to Paris, cutting

several sessions with producer Eddie Barclay.

Thompson remained in France until 1962, returning to New York and a year later headlining the Prestige LP Plays Jerome Kern and No More, which featured pianist Hank Jones. Around this same time his wife died, and in addition to struggling to raise their children on his own, Thompson's

old battles with the jazz power structure also remained, and in 1966 he

formally announced his retirement in the pages of Down Beat magazine.

Within a few months he returned to active duty, but remained frustrated

with the industry and his own ability -- during the March 20, 1968, date

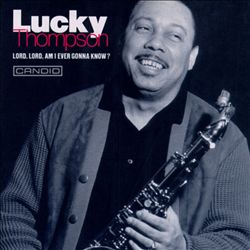

captured on the Candid CD Lord, Lord Am I Ever Gonna Know?, he says "I feel I have only scratched the surface of what I know I am capable of doing." From late 1968 to 1970, Thompson

lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, touring widely across Europe before

returning the U.S., where he taught music at Dartmouth University and in

1973 led his final recording, I Offer You. The remaining decades of Thompson's

life are in large part a mystery -- he spent several years living on

Ontario's Manitoulin Island before relocating to Savannah, GA, trading

his saxophones in exchange for dental work. He eventually migrated to

the Pacific Northwest, and after a long period of homelessness checked

into Seattle's Columbia City Assisted Living Center in 1994. Thompson remained in assisted care until his death on July 30, 2005.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/luckythompson

Back in New York by 1948, Thompson began a period of varied activity, fronting groups at the Savoy Ballroom, appearing at the Nice festival, recording with Thelonious Monk and playing on the heralded Miles Davis album, “Walkin'.” In 1956, he toured Europe with Stan Kenton, then chose to live abroad for extended periods, from 1957 to 1962, making a number of recordings with groups while overseas.

His skepticism about the jazz business may have kept him from a broader career recording as a bandleader; but there was “Tricotism,” from 1953, with the Lucky Seven. Then in 1962 Thompson came back to New York, where he signed with Prestige and recorded the sessions for albums “Happy Days Are Here Again,” “Plays Jerome Kern and No More,” and “Lucky Strikes,” from 1964, thought to be his highlight album. He did other sides for various labels as in the ’65 joining with Tommy Flanagan “Lucky Meets Tommy.” His last recordings were “Goodbye Yesterday,” (1972) and “I Offer You,” (1973), made for the Groove Merchant label.

After returning to New York for a few years, he lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, from late 1968 to 1970. He came back to New York again, taught at Dartmouth in 1973 and 1974, then disappeared from the Northeast, and soon from music entirely.

By the early 90's he was in Seattle, mostly living in the woods or in shelter offered by friends. He did not own a saxophone. He was hospitalized a number of times in 1994, and finally entered an Assisted Living Center, where he lived from 1994 until his death in July 2005.

Source: James Nadal

Lucky Thompson

Lucky Thompson

A legendary tenor and soprano saxophonist who

took his place among the elite improvisers of jazz from the 1940's to

the 1960's and then quit music. Lucky Thompson connected the swing era

to the more cerebral and complex bebop style. His sophisticated,

harmonically abstract approach to the tenor saxophone endeared him to

the beboppers, but he was also a beautiful balladeer.

Thompson was born in Columbia, South Carolina, but grew up on Detroit's East Side. He saved to buy a saxophone study book, practicing on a simulated instrument carved from a broomstick. He finally acquired a saxophone when he was 15, practiced eight hours a day and, within a month, was playing around town, most notably with the King's Aces big band, among who was vibraphonist Milt Jackson, later a frequent associate. Thompson left Cass high school early to join ex-Lunceford altoist Ted Buckner at Club 666, a top spot in the black section of Detroit.

He left the city in August 1943 with Lionel Hampton's orchestra, touring for four months before settling in New York. He was soon playing for exacting bandleaders such as Don Redman and Lucky Millinder, performing on 52nd street with drummer Big Sid Catlett, and making his recording debut in March 1944 with trumpeter Hot Lips Page.

After a run with Billy Eckstine's big band, then a hotbed of modernism, Thompson spent a fruitful year with the Count Basie orchestra. By October 1945, he was in Los Angeles, and stayed for two years, taking on the mantle of local hero and participating in more than 100 recording sessions, with everyone from Dinah Washington to Boyd Raeburn. When Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker made their legendary visit to Billy Berg's club in Los Angeles, Thompson was retained to cover for the errant Parker. Lucky played on one of Parker's most celebrated recording sessions, for Dial Records on March 28, 1946.

Thompson was born in Columbia, South Carolina, but grew up on Detroit's East Side. He saved to buy a saxophone study book, practicing on a simulated instrument carved from a broomstick. He finally acquired a saxophone when he was 15, practiced eight hours a day and, within a month, was playing around town, most notably with the King's Aces big band, among who was vibraphonist Milt Jackson, later a frequent associate. Thompson left Cass high school early to join ex-Lunceford altoist Ted Buckner at Club 666, a top spot in the black section of Detroit.

He left the city in August 1943 with Lionel Hampton's orchestra, touring for four months before settling in New York. He was soon playing for exacting bandleaders such as Don Redman and Lucky Millinder, performing on 52nd street with drummer Big Sid Catlett, and making his recording debut in March 1944 with trumpeter Hot Lips Page.

After a run with Billy Eckstine's big band, then a hotbed of modernism, Thompson spent a fruitful year with the Count Basie orchestra. By October 1945, he was in Los Angeles, and stayed for two years, taking on the mantle of local hero and participating in more than 100 recording sessions, with everyone from Dinah Washington to Boyd Raeburn. When Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker made their legendary visit to Billy Berg's club in Los Angeles, Thompson was retained to cover for the errant Parker. Lucky played on one of Parker's most celebrated recording sessions, for Dial Records on March 28, 1946.

Back in New York by 1948, Thompson began a period of varied activity, fronting groups at the Savoy Ballroom, appearing at the Nice festival, recording with Thelonious Monk and playing on the heralded Miles Davis album, “Walkin'.” In 1956, he toured Europe with Stan Kenton, then chose to live abroad for extended periods, from 1957 to 1962, making a number of recordings with groups while overseas.

His skepticism about the jazz business may have kept him from a broader career recording as a bandleader; but there was “Tricotism,” from 1953, with the Lucky Seven. Then in 1962 Thompson came back to New York, where he signed with Prestige and recorded the sessions for albums “Happy Days Are Here Again,” “Plays Jerome Kern and No More,” and “Lucky Strikes,” from 1964, thought to be his highlight album. He did other sides for various labels as in the ’65 joining with Tommy Flanagan “Lucky Meets Tommy.” His last recordings were “Goodbye Yesterday,” (1972) and “I Offer You,” (1973), made for the Groove Merchant label.

After returning to New York for a few years, he lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, from late 1968 to 1970. He came back to New York again, taught at Dartmouth in 1973 and 1974, then disappeared from the Northeast, and soon from music entirely.

By the early 90's he was in Seattle, mostly living in the woods or in shelter offered by friends. He did not own a saxophone. He was hospitalized a number of times in 1994, and finally entered an Assisted Living Center, where he lived from 1994 until his death in July 2005.

Source: James Nadal

Lucky Thompson, Jazz Saxophonist, Is Dead at 81

by Ben Ratliff

August 5, 2005

New York Times

Lucky Thompson, a legendary tenor and soprano saxophonist who took his place among the elite improvisers of jazz from the 1940's to the 1960's and then quit music, roamed the country and ended up homeless or hospitalized for more than a decade, died on Saturday in Seattle. He was 81. His death was confirmed by his son, Daryl Thompson; the cause was not announced. Mr. Thompson was living in an assisted-care facility at the Washington Center for Comprehensive Rehabilitation in Seattle. Mr. Thompson connected the swing era to the more cerebral and complex bebop style. His sophisticated, harmonically abstract approach to the tenor saxophone built off that of Don Byas and Coleman Hawkins; he played with beboppers, but resisted Charlie Parker's pervasive influence. He also played the soprano saxophone authoritatively. "Lucky had that same thing that Paul Gonsalves had, that melodic smoothness," one of his contemporaries, the saxophonist Johnny Griffin, said in an interview. "He wasn't rough like Ben Webster, and he didn't play in the Lester Young style. He was a beautiful balladeer. But he played with all the modernists."

Mr. Thompson was born Eli Thompson in Columbia, S.C., on June 16, 1924, and moved to Detroit with his family as a child. After graduating from high school in 1942, he played with Erskine Hawkins's band, then called the 'Bama State Collegians; the next year he moved to New York as a member of Lionel Hampton's big band.

After six months with Hampton, while still very young, he swiftly ascended the ranks of hip. He played in Billy Eckstine's short-lived big band, one of the first to play bebop, which also included Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. He joined the Count Basie Orchestra in 1944.

In 1945 he left Basie in Los Angeles, and in 1945 and 1946 he played on, and probably created arrangements for, record dates for the Exclusive label, including those by the black cowboy star and former Ellington singer Herb Jeffries. When the Charlie Parker-Dizzy Gillespie sextet came through Los Angeles, Mr. Thompson was hired by Gillespie as a temporary replacement for Parker. Mr. Thompson was also on one of Parker's most celebrated recording sessions, for Dial Records on March 28, 1946.

Fiercely intelligent, Mr. Thompson was outspoken in his feelings about what he considered the unfair control of the jazz business by record companies, music publishers and booking agents. Partly for these reasons, he left the United States to live in Paris from 1957 to 1962, making a number of recordings with groups including the pianist Martial Solal. After returning to New York for a few years, he lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, from late 1968 to 1970. He came back to New York again, taught at Dartmouth in 1973 and 1974, then disappeared from the Northeast, and soon from music entirely. Friends say he lived for a time on Manitoulin Island in Ontario and in Georgia before eventually moving west. By the early 90's he was in Seattle, mostly living in the woods or in shelter offered by friends. He did not own a saxophone. He walked long distances, and was reported to have been in excellent, muscular shape.

He was hospitalized a number of times in 1994, and finally entered the Washington Center for Comprehensive Rehabilitation. His skepticism about the jazz business may have kept him from a career recording as a bandleader -- "Tricotism," from 1956, and "Lucky Strikes," from 1964, are among the few albums he made under his own name -- but he left behind a pile of imposing performances as a sideman. Among them are recordings with Dinah Washington in 1945, Thelonious Monk in 1952, Miles Davis in 1954 (the "Walkin"' session, a watershed in Davis's career), and Oscar Pettiford and Stan Kenton in 1956. His final recordings were made in 1973. In addition to his son, Daryl, of Stone Mountain, Ga., Mr. Thompson is survived by a daughter, Jade Thompson-Fredericks of New Jersey; and two grandchildren. Part of Mr. Thompson's legend came from the fact that he was rarely seen in public; at times it was hard for his old friends to find him. But the drummer Kenny Washington remembered Mr. Thompson's showing up when Mr. Washington was performing with Johnny Griffin's group at Jazz Alley in Seattle in 1993. Mr. Thompson listened, conversed with the musicians, and then departed on foot for the place where he was staying -- in a wooded spot in the Beacon Hill neighborhood, more than three miles away.

A version of this article appears in print on Aug. 5, 2005, Section B, Page 7 of the National edition with the headline: Lucky Thompson, Jazz Saxophonist, Is Dead at 81. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

Lucky Thompson

American musician

Alternative Title: Eli Thompson

Lucky Thompson, nickname of Eli Thompson, (born June 16, 1924, Columbia, South Carolina, U.S.—died July 30, 2005, Seattle, Washington), American jazz musician, one of the most distinctive and creative bop-era tenor saxophonists, who in later years played soprano saxophone as well.

Lucky Thompson, c. 1948. William P. Gottlieb Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (LC-GLB13- 0852)

Thompson played tenor saxophone in the early 1940s with Lionel Hampton, the Billy Eckstine band, and Count Basie before a highly active period in Los Angeles working with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, Boyd Raeburn, and other pioneers of bebop. Even in this early stage of his career, Thompson revealed an original improvising approach. His beautiful tone was reminiscent of Ben Webster’s, with a rough edge in climactic passages; much of his phrasing was influenced by the early works of Don Byas, and his solo style was a more modern development of the Webster saxophone tradition. A subtle sense of expression, of unusual, accented harmonies, and of dramatic solo form characterized his finest work, specifically in his 1950s recordings as a bandleader (including his unique saxophone-guitar-bass trio in Tricotism [1956]) and with Milt Jackson, Jo Jones, and Miles Davis.

Thompson lived in Europe for extended periods in the 1950s and ’60s. He was less active upon subsequent returns to the United States, during which he emphasized the lyrical qualities of his style and soloed increasingly on soprano saxophone. He taught at Dartmouth College (1973–74), but disenchantment with the music business led to his early retirement.

Lucky Thompson

Perfectionist jazz saxophonist who fought against stereotyping

Friday 5 August 2005

'Lucky Thompson was a perfectionist almost to the point of mania," Ronnie Scott remembered of the time the tenor saxophonist played at his London jazz club in June 1962. "Between sets," Scott continued, "he'd clean his instruments out and pack them away, and when it was time to go on, you'd have to allow 10 or 15 minutes for him to get them out again and clean them up and get them ready."

By mixing elements of the playing of the tenor saxophonists Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young and Don Byas with a considerable helping of his own style, Lucky Thompson became one of the great players of the instrument. He fell between the swing players and the bebop musicians in terms of style, but by the Fifties had adjusted his playing so that it sat happily at his best with Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk or Milt Jackson.

Thompson was always difficult, an awkward eccentric and, sometimes with good reason, a constant complainer. He didn't like the rhythm section provided by the Scott Club and wrote an open letter which was published in the Melody Maker:

I've just done the best that's possible in the circumstances. If that's any consolation. It seems to me the main difficulty lies in the fact that there are vast differences of conception in the rhythm section itself. This makes it impossible to establish the kind of impulse to which I could respond fully.

Stan Tracey was the pianist in that rhythm section. "Socially, musically, Lucky Thompson and Don Byas were the hardest to accompany," he responded:

Just plain horrible vibrations. Used to put us down in the music - all sorts of nasty little messages flying about in the music. I was all fucked up at the time and I was Mr Nasty anyway. My nerves were all nicely bared and raw and so I used to take the piss out of them in the music.

Throughout his career Thompson used the term "vultures" to describe those whom he saw as preying on musicians to exploit them. He battled them ceaselessly and formally announced in Downbeat magazine in 1966, and on many other occasions, that he was retiring from what he called the business side of jazz.

He was born Eli Thompson in South Carolina in 1924; his mother died when he was five and Eli had to help bring up his younger siblings. At one stage his father bought him a jersey with the word "Lucky" across the chest. He didn't realise that he was setting his son's nickname for life. Given what was to follow, it was hardly an appropriate choice.

Fascinated by and absorbed in music, the boy had no hope of affording a saxophone. "I ran errands and got myself enough money to buy a saxophone book," he said.

It had a picture of a real saxophone to use as a fingering chart. I chopped the bristles off a broom and carved the main lines of a saxophone into it. I carved the keys into it, too.

Thompson finally acquired a saxophone when one was accidentally delivered to his home with some furniture. He had already taught himself to read music.

After a job as a barber, he began his musical career in the early Forties working first with territory bands, including nine months with the 'Bama State Collegians. "I came to New York in 1943 with Lionel Hampton's band," Thompson said.

Shortly after I arrived found myself replacing Ben Webster at the Three Deuces. The first night I was to play, who was in the house but Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, Lester Young and Ben Webster, all of them there at the same time.

Art Tatum was also in the audience. "I never played so horrible in my life," Thompson said. "I don't know how I survived, believe me, because for the first time, I found my fingers in between the keys."

Thompson worked in the New York clubs with the bassist Slam Stewart's quartet, that included Erroll Garner and Thompson's particular friend, the drummer Big Sid Catlett. He went out on the road again with Hampton, but left after six months to join the band led by the singer Billy Eckstine. This band was the embryo of bebop, including as it did Charlie Parker, Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie and Sarah Vaughan.

In November 1944, Thompson left for a year with Count Basie. Settling in Los Angeles at the end of 1945, he soon found work as a studio musician and as a sideman in the jazz groups led by Boyd Raeburn, Slim Gaillard, Jimmy Mundy and Dodo Marmarosa. When Parker and Gillespie visited Los Angeles, he played and recorded with them.

In 1948 he came to Europe to play at the Nice Jazz Festival, by this time having returned to live in New York. He led a band of his own at the Savoy Ballroom there, worked with Thelonious Monk and was one of the musicians on the seminal Miles Davis recording session in 1954 that produced "Walkin'". He made further outstanding albums with Milt Jackson and Jo Jones.

"I fought against being a stereotype," Thompson said. So they wrote about me as the musician "without school, without stereotype". It cost me a career. This profession was indifferent to an honest man. In fact I never had a career, but I fought for a few moments here and there.

To escape the "vultures", Thompson moved to Paris in February 1956 and in April that year joined the Stan Kenton band which was touring France and short of a baritone sax player.

I picked up a baritone sax right off the stage. Never had played one, but I had to play it in the band straight after picking it up for the first time.

Thompson returned to the States with Kenton, but was blacklisted by Joe Glaser, Louis Armstrong's manager, after a pointless row on a flight over whether Armstrong should leave the plane first when it landed. Starved of work, Thompson made another fine album with Milt Jackson and then in 1958 he bought a farm in Michigan, where he lived with his wife, Thelma, and two children.

Leaving them behind, he went back to France, where he stayed until 1962, never short of work, and at this period he became one of the first modern musicians to take up the soprano saxophone. He played frequently with another maverick musician, the bassist Oscar Pettiford, and with the remarkable pianist Martial Solal, achieving great things with both of them. Shortly after he went back to the farm in Michigan, his wife died. He drifted away from music until, in 1968, he returned to France and toured widely across Europe.

In 1973-74, Thompson taught briefly at Dartmouth College and at Yale University, after which he retired once more from music. He lived for a while in Canada before moving to Savannah, Georgia. Here he gave his instruments to a dentist in exchange for dental work. He moved on to Atlanta, where he was badly beaten up, and then to Denver, to Oregon and in the late Eighties to Seattle. He became a homeless recluse in the city until in 1994 he was taken into the Columbia City Assisted Living Center there.

Lucky Thompson In Paris: The 1961 Candid Records Session

Noal Cohen and

Chris Byars

Introduction

Unauthorized recordings of live jazz performances can be a thorn in the side of musicians but of enormous value to the historian who is in a constant search for additional examples of a subject’s creativity. Besides featuring solos that are often less inhibited and more adventurous than those recorded in a studio setting, live sessions can also provide important information not found elsewhere. For better or worse, jazz aficionados have historically recorded live music and radio broadcasts for their own use and shared them with like-minded individuals. Often the audio quality of these amateur recordings is less than optimal and unflattering to the artists involved, but in many instances, the sound is surprisingly good. The digital age has certainly facilitated the transfer of music and it seems clear that the ready availability of recordings made without the musicians’ approval is now part of the landscape. The abundance of live performances accessible on YouTube graphically demonstrates the current state of affairs.

An instructive example of the utility of live recordings in jazz research involves the saxophonist Lucky Thompson who, in the spring of 1961, led a remarkable quartet session in Paris for the Candid Records label. At the time, only one of the eight Thompson compositions recorded was issued, the remaining tracks languishing for years before finally being released in 1997; however, the titles of these pieces had never been found. Around the same time as the Candid session, he took part in a German radio broadcast with an octet, in a program involving only his own material. Fortunately, the radio broadcast had been recorded by persons unknown and as described below, collaboration between a musician, a discographer and a record collector led to the 2006 discovery that six of the tunes from the studio session were also performed during the radio broadcast. From the radio network archives, Thompson’s titles for his songs were uncovered but this was made possible only through access to the private recording.

As to the nature of these now nearly fifty year-old compositions, careful analysis reveals subtle harmonic and structural complexities not discernable through casual listening. Although insufficiently acknowledged, Thompson was as individual a writer as he was an instrumentalist.

About Lucky Thompson [1]

Of the tenor saxophonists to emerge during the bebop era of the 1940s, Eli ‘Lucky’ Thompson (1923–2005) [2] was something of an anomaly. At a time when Lester Young and Charlie Parker were the dominant stylistic models, Thompson instead drew on Coleman Hawkins, Chu Berry, Ben Webster, and Don Byas for his inspiration, ingeniously updating those earlier influences harmonically and rhythmically to create an original sound and conception that could be adapted to almost any musical context. Tad Shull has analyzed Thompson’s style and describes it as “backward” in the sense that his phrasing is the opposite of what one might expect, with accents falling in the “wrong” places on the “wrong” beats and in the “wrong” order. [3] That such an approach was successful is a tribute to Thompson’s great talent but at the same time a hindrance to the facile categorization and assimilation of his playing. The subtleties of his innovations were difficult for many listeners, critics and musicians to fully appreciate, especially in his later years.

Thompson was born in Columbia, South Carolina but soon thereafter his family moved to Detroit, Michigan where he was raised and received his first musical training and experience. By 1943 he was a member of the Lionel Hampton orchestra. Stints with the bands of Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, and Boyd Raeburn followed. With Basie, he contributed solos to the classic Columbia recordings of “Taps Miller” (December 6, 1944) and “Avenue C” (February 26, 1945). Leaving that ensemble in the fall of 1945, he settled in Los Angeles where he made his first recording as a leader for the Excelsior label. In February and March of 1946 he was part of the landmark sessions led by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker for the Dial label that introduced such bebop standards as “Confirmation”, “Yardbird Suite” and “Ornithology.” And in April 1947, four tracks recorded by “Lucky Thompson and his Lucky Seven” for RCA Victor attracted considerable attention, in particular, the leader’s bravura performance on the ballad “Just One More Chance.”

Through the 1950s Thompson’s style evolved, taking on more modern aspects while maintaining an originality that bridged eras. In April of 1954, he recorded two extended blues with Miles Davis for the Prestige label, making history in the process by helping to revive Davis’s flagging career and ushering in a sub-genre that would become known as hard bop. His solos on these tracks (“Walkin’” and “Blue ’n Boogie”) are models of melodic construction steeped in elegance and passion.

In the mid-1950s, Thompson’s star appeared to be rising as he turned out many memorable recordings under his own name and contributed significantly to sessions led by Milt Jackson, Jimmy Cleveland, Stan Kenton, Oscar Pettiford, and Quincy Jones to name just a few. In reality, however, his thorny personality and refusal to compromise were making survival in the music business difficult, at least in America.

Thompson spent a substantial portion of his career performing and recording in Europe. Motivated by a quest for self-expression without compromise and a deeply rooted distrust of the American commercial institutions that controlled most aspects of the music/entertainment industry, he lived in France and Switzerland for extended periods from 1956 until his withdrawal from activities as a professional musician in the mid 1970s. During this time, he performed widely throughout the Continent and participated in a host of recordings with the very finest English and European musicians as well as American expatriates including drummer Kenny Clarke, trombonist Nat Peck and guitarist Jimmy Gourley.

It was also in Europe that Thompson began experimenting with the soprano saxophone, recording on that horn for the French Symphonium label in January of 1959, over a year earlier than John Coltrane’s first soprano session. [4] But because Thompson’s French recordings were poorly distributed — not being issued in the U.S.A. until 1999 — his pioneering efforts on soprano were largely overlooked.

A prolific but largely unrecognized composer, Thompson produced a broad range of material from pop and rhythm and blues songs to complex post-bop pieces. He was also one of a small number of musicians of his era concerned with the protection of rights to their music through the establishment of their own publishing companies. Thompson railed against royalty theft and exploitation of composers by entrenched record producers and publishers throughout his career, burning bridges in the process and ending up deeply embittered by an industry he viewed as corrupt and insensitive to genuine creativity and quality. [5]

The later years of Thompson’s career (1968–1974) were characterized by a pattern of ups and downs associated with family and professional problems. [6] Even so, some fine recordings were made during this period including a session backed by the trio of the Spanish pianist Tete Montoliu and his last studio sessions done for Sonny Lester’s Groove Merchant label. After teaching briefly at Dartmouth College in the early 1970s, and only in his fifties, he left his professional life behind and settled for a time in Savannah, Georgia where Christopher Kuhl interviewed him in 1981. [7] But for years after that last known encounter, his whereabouts were a mystery until the mid-1990s when he was discovered in a homeless condition in the Seattle, Washington area. Suffering from paranoia and dementia, he spent his remaining years in assisted living facilities and nursing homes, being visited occasionally by musicians passing through the Seattle area. [8] Thompson succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease in 2005.

Session History

Between 1959 and 1962, Thompson participated in several European radio and TV broadcasts as well as film soundtrack recordings. Arguably, of greatest historical significance — although little known because nothing was ever issued commercially from them — are five NDR (North German Broadcasting) jazz workshops that took place on April 17, 1959 (No. 6), April 22, 1960 (No. 13), November 25, 1960 (No. 16), April 28, 1961 (No. 19), and May 31, 1962 (No. 25). Originating from studios in Hamburg and Frankfurt, the series was produced by Hans Gertberg and often featured original compositions by the ensemble members. The workshop of April 28, 1961 comprised all Thompson material, seventeen new pieces and two holdovers from 1956 [9] performed by an octet of five horns and three rhythm, an instrumentation that he seemed to favor throughout his career. Fortunately, collectors made recordings of these radio broadcasts, which, although unauthorized, must be considered valuable and enlightening components of Thompson’s oeuvre. Around the same time as the April 1961 broadcast, Thompson led a remarkable quartet recording in Paris for the Candid record label that forty-five years later would be found to have an important connection to NDR Workshop No. 19, as we will see.

Candid Records was formed in 1960 when Archie Bleyer, the owner of Cadence Records, asked writer Nat Hentoff to create a jazz subsidiary. Although short-lived, Candid was noted for issuing high quality, innovative material by jazz artists such as Charles Mingus, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Cecil Taylor, Pee Wee Russell, Coleman Hawkins, Booker Ervin, and Booker Little as well as blues figures like Lightnin’ Hopkins. As producer, Hentoff allowed the artists wide latitude, a policy that led to groundbreaking and sometimes controversial recordings, most notably Roach’s politically and sociologically charged Freedom Now Suite. When both Cadence and Candid went bankrupt, pop vocalist Andy Williams (who had recorded for Cadence) acquired the entire catalog. Some of the jazz recordings were reissued later on his Barnaby label. In 1988 the English record producer Alan Bates took control of the Candid catalog and began to reissue on compact disc the original LPs along with some new discoveries. The London-based label is still active, offering the classic 1960s recordings as well as CDs by contemporary artists. [10]

The session Thompson recorded in Paris was not supervised by Hentoff but by the saxophonist himself. He chose as sidemen his longtime associate, bebop innovator Kenny Clarke (1914–1985) on drums, the highly original Algerian-born pianist Martial Solal (1927–), and the German bassist Peter Trunk (1936–1973).

A recipient of the prestigious JAZZPAR Prize in 1999, the versatile Solal is considered one of France’s most important jazz musicians and has recorded with a broad spectrum of artists from Django Reinhardt and Sidney Bechet to Lee Konitz and Dave Douglas. Solal also produced scores for many films. Now in his eighties, he continues to appear all over the world. Thompson and Solal collaborated on a number of sessions in France between 1957 and 1961 and recently the INA (French National Audiovisual Institute) made available a video of Thompson’s octet recorded in May of 1960 at Club St. Germain, on which both Solal and Clarke participate. [11]

Frequently associated with European stalwarts like saxophonists Hans Koller and Klaus Doldinger, trombonist Albert Mangelsdorff, trumpeters Benny Bailey and Dusko Goykovic, guitarist Attila Zoller, and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, bassist Trunk was often found backing Thompson including a pianoless trio session for the French Vogue label in 1960 and NDR Workshop No. 19. He died prematurely in an auto accident in 1973.

Eight titles were recorded at the quartet session but only one of them, “Lord, Lord Am I Ever Gonna Know?”, was released initially (1961) on a Candid compilation called The Jazz Life! (Candid CM 8019/CS 9019). Other artists on this LP were an ensemble called the “Jazz Artists Guild” that included trumpeter Roy Eldridge, trombonist Jimmy Knepper, multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy, pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Charles Mingus, and drummer Jo Jones; blues guitarist/vocalist Lightnin’ Hopkins; the Calvin Massey Sextet; an octet led by Mingus; and a septet under the leadership of trumpeter Kenny Dorham. This was one of the last Candid LPs to be issued by the original label. The Thompson LP including all eight tracks, intended to be Candid 9035, never saw the light of day; however, tapes containing the entire session were eventually found in a Barnaby Records warehouse in Los Angeles after Alan Bates had acquired the Candid archives in the late 1980s. Unfortunately, song titles did not accompany the newly discovered tapes. Faced with a predicament, Bates and historian/critic Mark Gardner, who wrote the liner notes, decided to assign arbitrary titles to the seven previously unreleased and unnamed compositions when the CD Lord, Lord Am I Ever Gonna Know? (Candid (Eng.) CCD 79035) was finally issued in 1997. How this was done is intriguing. [12]

Included in the CD was a spoken “introduction” by Thompson himself, taped in 1968 for inclusion in a jazz symposium to be held in Coventry, England in May of 1968. Gardner was to give a presentation on Thompson’s career and music but the event never took place, apparently due to a lack of financial support. Nonetheless, the saxophonist’s thoughts, presented with piano background (presumably by him), provide insight into the way he viewed the music business as it was evolving at the time. While stated calmly and articulately, bitterness and frustration are apparent in Thompson’s comments which seem to foreshadow his decision six years later to leave his chosen profession for good. Using this introduction, Bates and Gardner selected phrases from which the titles for the newly discovered compositions were derived. They are highlighted in the following transcript: [13]

Hello Mark and hello there, everyone in England. This is Lucky Thompson here in good old New York City on a very beautiful Tuesday. I think it is March 20th in ’68. I’d like to say that I feel very warm inside knowing that I’ve been chosen by you to honor during your next convention. But I’m somewhat saddened by the fact that I feel like a man who’s being paid for something he’s yet to do and that’s due to the fact that I feel that I have only scratched the surface of what I know that I’m capable of doing. And I’m one that would like to feel worthy of such an honor as this so please bear with me and I hope that one day soon I will be able to find new openings by which to share these many blessings that God has so chosen to entrust in me.

You know, just recently I’ve discovered the fact that not only are the musicians and entertainers guilty of not assuming their proper share of their responsibilities which are necessary to help make their profession a healthy one. But I feel that you, the public, also must share a bit of this responsibility because, you see, I think, that some of you should reappraise your values these days; because, are you really buying a ticket to your favorite theater or your favorite concert hall because it’s your choice of artists that are appearing there, or is it the choice of those behind our profession whose desire is to exploit the arts and the artists and are also working overtime to make sure that you, the public, lose your freedom of choice?

For I say that to say this: That until you are sure as to whether or not the idols that you worship are of your own choosing, you are indirectly supporting those who are continuously exploiting our profession and the artist. And I just found out recently that all of us, whether large or small, whether recording companies, publishers, booking agents, et cetera, are completely dependent upon you, the public, for support. So reappraise your values and see if you can be the one to decide as to whether or not the artist or artists that you are idolizing happen to be of your own choice. This is all we ask.

And so I’d like to say thanks very much again to you, Mark, and all my friends there in England and throughout the world and I do sincerely hope that soon, in the very near future, I’ll have the privilege of being there with you once again. And until that time, God bless all of you and do me one favor, don’t forget to love and respect one another.

Lucky Thompson...ciao.Thus the 1997 CD was issued with the following program:

https://www.jazzwax.com/2017/09/lucky-thompson-paris-1956-59-.html

September 6, 2017

Lucky Thompson: Paris 1956-59

Eli "Lucky" Thompson was one of jazz's most confident and engaging tenor saxophonists. On recordings, his imagination on solos was so fast and bountiful that he filled virtually every spare space with warm, exciting ideas. Over the course of his career, Thompson was artistically most at home in Paris, as evidenced by his exhilarating slippery and smokey sound on recordings made there in the 1950s. In recent years, his Paris recordings have been released haphazardly on French and American labels, only to drift out of print. Now, we have all of them on two new sets from Fresh Sound.

The first is Lucky Thompson: The Complete Parisian Small-Group Sessions 1956-1959, a four-CD set that comes with a glossy 34-page booklet featuring color and black-and-white images and lengthy notes by Jordi Pujol. The second is a single CD—Lucky Thompson in Paris 1956: The All Star Orchestra Sessions. The fidelity on both sets is remarkable.

Born in Columbia, S.C., Thompson moved with his family to Ohio and then Detroit. After nearly 15 years of recording with top jazz bands and ensembles, Thompson moved to Paris in early 1956 after enduring professional problems that involved unfairness and unemployment. There were songs he wrote that weren't credited to him, clubs that tried to stiff him and record labels that shortchanged him and repeatedly passed over him when staffing dates. The work dried up.

Back in the late 1940s and early '50s, he was considered "difficult' by those skilled in chiseling musicians. Thompson simply grew wearing trying to figure out why he wasn't receiving what he was promised or due, going so far as to start his own publishing company in the late 1940s.

Prior to leaving for Paris, Thompson had established himself as a saxophone giant with a distinct sound. He first recordings were with Hot Lips Page in 1944. He recorded with Count Basie later that same year and into the first half of 1945 before recording with Boyd Raeburn's band in 1945 and '46. Thompson recorded with Charlie Parker in 1946 and '49, Johnnie Ray in 1951, Thelonious Monk in 1952, King Pleasure in 1954 and Oscar Pettiford in 1956 before leaving for Paris. During a return visit to the States that year, he recorded again with Pettiford and on Stan Kenton's Cuban Fire.

As these Paris recordings show, Lucky was spiritually free in France. His playing on standards is polished and daring, while his work on his own compositions is tremendously exciting. That's one of the great treats of this set: Thompson was a brilliant songwriter, and it shows on songs such as Passin' Time, Nothing But the Soul and Why Weep?, to name just a few.

On many of the recordings, Thompson unleashes ideas as if he's operating a Singer sewing machine. His quick thinking and steady precision take you aback. In addition, while Thompson could latch on to an uptempo song like a tiger, he was deeply emotional on ballads such as Time on My Hands and Everything Happens to Me.

But what makes this set especially rewarding are the many groups in which he recorded. There are 19 different ones in all, which means different musical moods and challenges on each one, and the results are never dull. Among these varied sessions are eight bluesy tracks with pianist Sammy Price and four hard boppers with drummer Kenny Clarke that features a masterful version of Four. All of the French sidemen on this set are terrific and easily on par with their American counterparts. There are simply too many to list here.

The all-star orchestra sessions of 1956 include a crack Quincy Jones-influenced band led by Herni Renaud and three recording sessions with drummer Gerard Pochonet. All of songs recorded by Pochonet were written and arranged by Thompson and equal to Quincy Jones's work during this period. Which makes one wonder why Thompson wasn't arranging for Basie and other big bands in the States.

Thompson returned to the U.S. in 1963 and recorded here through 1968 before moving to Lausanne, Switzerland. In the early 1970s, Thompson returned to New York, taught at Dartmouth in New Hampshire in 1973 and '74 and then disappeared. He reportedly lived for a time on Manitoulin Island in Ontario and in Georgia before moving to Oregon, where he was largely homeless in the 1990s and early 2000s. There may have been mental illness issues that went unmedicated.

Lucky Thompson died in Seattle in 2005. He was 81.

JazzWax tracks: You'll find Lucky Thompson's Complete Parisian Small-Group Sessions 1956-1959 here and here.

You'll find Lucky Thompson in Paris 1956: The All Star Orchestra Sessions here and here.

JazzWax clips: Here's Passin' Time...

Here's But Not for Tonight...

And here's Easy Going...

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=104871379

Sax In The City: A Rare Recording Of Lucky Thompson

Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews Lucky Thompson: New York City, 1964-65 featuring rare live recordings of saxophonist Lucky Thompson.

Thompson played with Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Thelonious Monk and Stan Kenton. He also made records of his own in the US and all over Europe.

Thompson passed away in 2005.

Thompson played with Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Thelonious Monk and Stan Kenton. He also made records of his own in the US and all over Europe.

Thompson passed away in 2005.

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/104871379/104871378" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

TERRY GROSS, host:

Saxophonist Lucky Thompson was in the thick of jazz for 30 years, playing with Armstrong and Basie and Monk and Stan Kenton and making records of his own in the U.S. and all over Europe. He dropped off the scene in the 1970s and never returned, passing away in 2005. Some rare, live Lucky Thompson is now out. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says that's good luck for us.

(Soundbite of music)

(Soundbite of applause)

KEVIN WHITEHEAD: Lucky Thompson's Octet, with Richard Davis on bass, at New York's Little Theater in 1964. Thompson was real saxophonist's saxophonist. Not a household name in jazz maybe, but I know some tenor players who scarf up every note they can find. I expect they'll be elated by the new set: "Lucky Thompson: New York City, 1964-65," on two CDs from the indie label Uptown. (Soundbite of music)

WHITEHEAD: Thompson loved midsized ensembles that maneuver like a small group and hint at the hurly-burly of a big band. His octet sounds a little like Sun Ra in the 1950s.

(Soundbite of music)

WHITEHEAD: Widely as the writing is, the real attraction on these rediscovered live dates is Lucky Thompson's saxophone. Like his early idol Don Byas he could play in and with different dialects, modulating his voice like a stage actor. You can spot some swing era swagger, Stan Getz's pleading tone and a little restless Coltrane. But Thompson used all that inspiration to sound more like himself to expand the expressive qualities he had already. I think that's why saxophonists love him. He shows how to fold influences into a well-rounded style of your own. This is "'Twas Yesterday."

(Soundbite of song, "'Twas Yesterday")

WHITEHEAD: The other half of the new Lucky Thompson set is a 1965 nightclub broadcast with a quartet giving him even more room to run. He was one of the first modernists to pickup the unfashionable soprano sax in the late 1950s -after Steve Lacy, but before John Coltrane. Lucky's liquid tone falls between Lacy's watery purity and Coltrane's vinegar bites.

(Soundbite of music)

WHITEHEAD: Lucky Thompson hated the music business, hated how promoters and critics and publicists tried to categorize musicians as hot or cool, swing or bebop. He was above all that. I fought all my life and said you'll never stereotype me, he told an interviewer after he gave up performing. His cool charts and hot playing, his hard or soft tone on two saxophones all made Lucky Thompson too slippery to pin down. That was a good artistic choice and maybe a bad career move.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead is currently on leave from teaching at the University of Kansas. And he's a jazz columnist for emusic.com. He reviewed "Lucky Thompson: New York City, 1964-65," on the Uptown label. You can download podcasts of our show on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

I'm Terry Gross.

Saxophonist Lucky Thompson was in the thick of jazz for 30 years, playing with Armstrong and Basie and Monk and Stan Kenton and making records of his own in the U.S. and all over Europe. He dropped off the scene in the 1970s and never returned, passing away in 2005. Some rare, live Lucky Thompson is now out. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says that's good luck for us.

(Soundbite of music)

(Soundbite of applause)

KEVIN WHITEHEAD: Lucky Thompson's Octet, with Richard Davis on bass, at New York's Little Theater in 1964. Thompson was real saxophonist's saxophonist. Not a household name in jazz maybe, but I know some tenor players who scarf up every note they can find. I expect they'll be elated by the new set: "Lucky Thompson: New York City, 1964-65," on two CDs from the indie label Uptown. (Soundbite of music)

WHITEHEAD: Thompson loved midsized ensembles that maneuver like a small group and hint at the hurly-burly of a big band. His octet sounds a little like Sun Ra in the 1950s.

(Soundbite of music)

WHITEHEAD: Widely as the writing is, the real attraction on these rediscovered live dates is Lucky Thompson's saxophone. Like his early idol Don Byas he could play in and with different dialects, modulating his voice like a stage actor. You can spot some swing era swagger, Stan Getz's pleading tone and a little restless Coltrane. But Thompson used all that inspiration to sound more like himself to expand the expressive qualities he had already. I think that's why saxophonists love him. He shows how to fold influences into a well-rounded style of your own. This is "'Twas Yesterday."

(Soundbite of song, "'Twas Yesterday")

WHITEHEAD: The other half of the new Lucky Thompson set is a 1965 nightclub broadcast with a quartet giving him even more room to run. He was one of the first modernists to pickup the unfashionable soprano sax in the late 1950s -after Steve Lacy, but before John Coltrane. Lucky's liquid tone falls between Lacy's watery purity and Coltrane's vinegar bites.

(Soundbite of music)

WHITEHEAD: Lucky Thompson hated the music business, hated how promoters and critics and publicists tried to categorize musicians as hot or cool, swing or bebop. He was above all that. I fought all my life and said you'll never stereotype me, he told an interviewer after he gave up performing. His cool charts and hot playing, his hard or soft tone on two saxophones all made Lucky Thompson too slippery to pin down. That was a good artistic choice and maybe a bad career move.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead is currently on leave from teaching at the University of Kansas. And he's a jazz columnist for emusic.com. He reviewed "Lucky Thompson: New York City, 1964-65," on the Uptown label. You can download podcasts of our show on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

I'm Terry Gross.

Copyright © 2009 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc.,

an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription

process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and

may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may

vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

https://jdisc.columbia.edu/session/lucky-thompson-april-28-1961

Home ›

Lucky Thompson April 28, 1961

Recording Date:

1961-04-28

Label Name:

NDR Jazz Workshop No. 19

Leader(s):

Ensemble Size:

octet

Venue Type:

studio

Venue Name:

Funkhaus des NDR, Studio 10

Venue Location:

Hamburg, Germany

Session Details:

This concert is unissued but copies of the radio broadcast have circulated among collectors. It was part of a series of radio and TV broadcasts produced by Hans Gertberg. The information, including Thompson's actual song titles for tracks 2, 4, 7, 12, 14 and 18, comes from the NDR (Norddeutscher Rundfunk) archives.

Timings do not include applause. Track 14 is incomplete with a drop out occurring during the piano solo. -- Noal Cohen's Lucky Thompson Discography 1957-1974.

Lucky Thompson, 81; Jazz Musician Bridged Swing and Bebop

Los Angeles Times

Thompson died July 30 at an assisted living facility in Seattle. The cause of death was not announced.

An independent figure even by jazz standards, Thompson had a quick rise, compiling an impressive resume that included stints with Billy Eckstine and Count Basie before his 21st birthday. By the mid-1950s, he had made significant recordings as a sideman with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, and was considered by many to be without peer on the tenor saxophone.

But less than 20 years later, he quit playing. He handed over his instruments to a dentist in Georgia to pay his bill.

Born Eli Thompson in Columbia, S.C., on June 16, 1924, Thompson was raised in Detroit and started playing saxophone at the age of 15. Initially, he played with local groups led by pianist Hank Jones and saxophonist Sonny Stitt. He first started gaining attention in the Basie band near the end of World War II, when he replaced saxophonist Don Byas, who was a big influence on him.

In the mid-1940s, Thompson lived in Southern California and was a busy studio musician, playing on an estimated 100 recordings in 1946 and 1947. When Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were visiting L.A. with their sextet to perform and record, Gillespie hired Thompson as insurance in case the brilliant but notoriously unreliable Parker failed to show. Gillespie used both players on the Dial Records date in March 1946.

By 1948, Thompson had moved to New York City, where he remained busy doing studio work, and made some fine recordings with bassist Oscar Pettiford and vibraphonist Milt Jackson. He can also be heard on Miles Davis’ “Walkin’ ” sessions -- working as part of the all-star band that Davis hired for the Prestige recording session.

Thompson moved to Paris in February 1956 and joined the touring Stan Kenton orchestra. He stayed mostly abroad until 1962, performing with some of Europe’s players, including pianists Matial Solal and Tete Montoliu. He also took up the soprano saxophone, an underused instrument at the time.

Through much of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, he moved back and forth

between the U.S. and Europe. He produced some of his most interesting

recordings in the United States during the early ‘60s, but he also had

long periods of inactivity.

By 1973, he had returned from Europe for good and began teaching, first at Dartmouth and then at Yale. It was at that point that he quit playing, embittered by the high fees that music promoters, record companies and music publishers were taking.

Over the years, he did make several recordings as a leader, including “Lucky Strikes” in 1964 and “Happy Days,” recorded the next year.

While Thompson dropped from public view, various reports said he was homeless. He hopscotched around the country and settled in Seattle in the late 1980s. In August 1994, he entered an assisted living facility.

He is survived by a son, a daughter and two grandchildren.

Lucky Thompson: New York City 1964-65 (Uptown)

Uptown’s two-CD Thompson set, released in 2009, inspired a brief flurry of comment and soon slipped under the radar. It deserves renewed attention. The album documents two live appearances of a musician who reached less fame than his ability and importance warranted. Thompson worked in the 1940s and ‘50s in Dizzy Gillespie’s sextet and with the big bands of Billy Eckstine, Tom Talbert and Count Basie. Hank Jones, Oscar Pettiford and Milt Jackson were among the colleagues who cherished their relationships with him. Thompson became bitter about the business part of the music business. His life began to unravel in the sixties. In the early seventies, he played little.

By 1973, he had returned from Europe for good and began teaching, first at Dartmouth and then at Yale. It was at that point that he quit playing, embittered by the high fees that music promoters, record companies and music publishers were taking.

Over the years, he did make several recordings as a leader, including “Lucky Strikes” in 1964 and “Happy Days,” recorded the next year.

While Thompson dropped from public view, various reports said he was homeless. He hopscotched around the country and settled in Seattle in the late 1980s. In August 1994, he entered an assisted living facility.

He is survived by a son, a daughter and two grandchildren.

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

Recent Listening: Lucky Thompson

Lucky Thompson: New York City 1964-65 (Uptown)

Uptown’s two-CD Thompson set, released in 2009, inspired a brief flurry of comment and soon slipped under the radar. It deserves renewed attention. The album documents two live appearances of a musician who reached less fame than his ability and importance warranted. Thompson worked in the 1940s and ‘50s in Dizzy Gillespie’s sextet and with the big bands of Billy Eckstine, Tom Talbert and Count Basie. Hank Jones, Oscar Pettiford and Milt Jackson were among the colleagues who cherished their relationships with him. Thompson became bitter about the business part of the music business. His life began to unravel in the sixties. In the early seventies, he played little.

He eventually all but dropped

out of performing to raise two sons as a

single father, developed dementia and in 2005 died all but forgotten.

Kind strangers who admired his music looked after him in his last years.

I never knew Thompson, never saw him in live performance, but his work reached me from the first time I heard it on Charlie Parker’s 1946 Dial recordings. In “Moose The Mooche,” “Yardbird Suite,” “Ornithology” and “A Night in Tunisia,” Thompson’s solos suggested elements of Coleman Hawkins and Don Byas, but the surge and thrust of his invented lines and the swagger in his delivery—particularly on the master take of “Tunisia”—set him apart from other tenor players. He was not, strictly speaking, one of the early bebop artists, but his playing fit perfectly with theirs. Later, I went back a step to 1944 to listen to Thompson on Count Basie’s “Taps Miller” and “Avenue C” and found that he was a fully formed soloist at twenty, mixing smoothness and roughness in perfect balance.

If I were to recommend essential Thompson recordings to people unfamiliar with him, I would start with the Parker Dials, then refer them to the 1954 Miles Davis Walkin’ session on Prestige, which has some of Thompson’s greatest solos. Of his own albums, I suggest Tricotimsm (1956) on Impulse! and Lucky Strikes (1964) on Prestige. Tricotism includes bassist Oscar Pettiford and pianist Hank Jones, with both of whom Thompson had special rapport. The album has been reissued under a different title. Jones, with bassist Richard Davis and drummer Connie Kay, is also on Lucky Strikes. In it, Thompson plays soprano saxophone in addition to tenor, and the album may well be his masterpiece.

He made a notable impact on Benny Golson in the early 1950s as Golson formed his style. Half a century later, the young saxophonist Chris Byars adopted Thompson as his model. When Thompson gets attention, it is invariably emphasized that his tenor saxophone style descended from Ben Webster and Don Byas and was inherited by Golson. That is true, but so simple an analysis overlooks the individuality, the recognizability, of his work.

In the first disc of the Uptown album, recorded at a 1964 concert at the Little Theater in mid-town Manhattan, Thompson led an octet. The little-big-band format allowed him an outlet for his arranger’s skills as well as his distinctive playing on tenor and soprano saxophones. With the superb rhythm section of Hank Jones, piano; Richard Davis, bass; and Al Dreares, drums, Thompson’s fellow horns are trumpeter Dave Burns, alto saxophonist

Danny Turner, baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne and trombonist Benny Powell—all among the elite of the post-bop New York scene. In Thompson’s writing, as in his playing, blues feeling predominates even when the composition’s form, as in “Firebug,” is that of a 32-bar song. “The World Awakes,” which in the sixties served Thompson as a sort of anthem, is a minor blues. His soprano solo combines intensity, light-heartedness and the penetrating tone that was an important element of his distinctiveness on the instrument. Jones (pictured left) solos, impeccably, of course, but Davis’s 12 choruses of walking bass practically steal the performance.

Still on soprano, Thompson eases into a relaxed solo, followed by Davis and Jones before the ensemble gives us the first passages of Thompson’s intriguing arrangement. The voicings reflect his accumulation of bebop wisdom as well as his admiration for the French impressionists. His first tenor saxophone feature on this disc is “’Twas Yesterday,” highlighting what the late critic John S. Wilson once described as Thompson’s “soft, furry, intimate tone.” “Firebug” brings spirited solos from Jones and Payne, a virtuosic and often very funny one from Powell, eight essential bebop choruses from the underrated Burns, then Thompson on tenor in a long solo in which each idea grows into the next; musical story-telling founded equally on logic and emotion. The ensemble accompanies Dreares, leaves him a few bars of solo space, then negotiates the intersecting contrapuntal lines of Thompson’s arrangement to an abrupt conclusion that triggers chuckles on the bandstand and in the audience.

The second CD contains a 1965 quartet date broadcast from the Half Note in lower Manhattan. Thompson’s accompanists are bassist George Tucker, drummer Oliver Jackson and the excellent little-known pianist Paul Neves (pictured right), who appears here in one of only two recordings

I’m aware of his having made. The other was Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s Spellbound,

which disappeared for a time but is again available. If anything,

Thompson is even more fluid on soprano in this version of “The World

Awakes,” spurred by Neves’ emphatic comping. The pianist’s solos and his

supportive accompaniment throughout make the attentive listener aware

that we lost a substantial musician when he died in Puerto Rico in the

1980s. He was in his early fifties. A native of Boston, Neves was the

brother of bassist John Neves, who worked with Jaki Byard, Stan Getz and

the big bands of Herb Pomeroy and Maynard Ferguson.

Neves (pictured right), who appears here in one of only two recordings

I’m aware of his having made. The other was Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s Spellbound,

which disappeared for a time but is again available. If anything,

Thompson is even more fluid on soprano in this version of “The World

Awakes,” spurred by Neves’ emphatic comping. The pianist’s solos and his

supportive accompaniment throughout make the attentive listener aware

that we lost a substantial musician when he died in Puerto Rico in the

1980s. He was in his early fifties. A native of Boston, Neves was the

brother of bassist John Neves, who worked with Jaki Byard, Stan Getz and

the big bands of Herb Pomeroy and Maynard Ferguson.

Thompson remains on soprano for a gentle exploration of “What’s New,” demonstrating the artistic strength to be found in restraint. Following the first chorus of Tadd Dameron’s “Lady Bird,” Neves drops out for a few choruses while Thompson indulges in one of his favorite tenor saxophone pursuits, strolling with bass and drums. When Neves reenters, the passion builds during a dozen more Thompson choruses and seven from Neves. Tucker makes the most of his only solo opportunity of the set. The last piece ends with a drum roll and Thompson’s “Paramount on Parade” intro on soprano. They set the stage for an incendiary “Strike Up the Band.” Thompson, on tenor, is the only soloist except for a sequence of power exchanges with Jackson, who is finally allowed to give full rein to his skills. It is a reminder of the versatility of a drummer who was equally effective in the range of jazz styles from traditional to modern.

The album recalls that, for all of the frustration he faced, the bitterness he felt and his sad end, Lucky Thompson’s music transmitted confidence and joy. In his brief conversations at the Half note with broadcast host Alan Grant, Thompson’s intelligence and gentlemanliness are apparent.

In the CD’s booklet, Noal Cohen’s comprehensive notes provide an extensive history of Thompson’s career. The 44-page booklet has several photos of Thompson, pictures and brief bios of the sidemen, and information about the Little Theater concert and the Half Note broadcast.

(Photo of Paul Neves by Katherine Hanna courtesy of Irene Kubota Neves)

single father, developed dementia and in 2005 died all but forgotten.

Kind strangers who admired his music looked after him in his last years.

I never knew Thompson, never saw him in live performance, but his work reached me from the first time I heard it on Charlie Parker’s 1946 Dial recordings. In “Moose The Mooche,” “Yardbird Suite,” “Ornithology” and “A Night in Tunisia,” Thompson’s solos suggested elements of Coleman Hawkins and Don Byas, but the surge and thrust of his invented lines and the swagger in his delivery—particularly on the master take of “Tunisia”—set him apart from other tenor players. He was not, strictly speaking, one of the early bebop artists, but his playing fit perfectly with theirs. Later, I went back a step to 1944 to listen to Thompson on Count Basie’s “Taps Miller” and “Avenue C” and found that he was a fully formed soloist at twenty, mixing smoothness and roughness in perfect balance.

If I were to recommend essential Thompson recordings to people unfamiliar with him, I would start with the Parker Dials, then refer them to the 1954 Miles Davis Walkin’ session on Prestige, which has some of Thompson’s greatest solos. Of his own albums, I suggest Tricotimsm (1956) on Impulse! and Lucky Strikes (1964) on Prestige. Tricotism includes bassist Oscar Pettiford and pianist Hank Jones, with both of whom Thompson had special rapport. The album has been reissued under a different title. Jones, with bassist Richard Davis and drummer Connie Kay, is also on Lucky Strikes. In it, Thompson plays soprano saxophone in addition to tenor, and the album may well be his masterpiece.

He made a notable impact on Benny Golson in the early 1950s as Golson formed his style. Half a century later, the young saxophonist Chris Byars adopted Thompson as his model. When Thompson gets attention, it is invariably emphasized that his tenor saxophone style descended from Ben Webster and Don Byas and was inherited by Golson. That is true, but so simple an analysis overlooks the individuality, the recognizability, of his work.

In the first disc of the Uptown album, recorded at a 1964 concert at the Little Theater in mid-town Manhattan, Thompson led an octet. The little-big-band format allowed him an outlet for his arranger’s skills as well as his distinctive playing on tenor and soprano saxophones. With the superb rhythm section of Hank Jones, piano; Richard Davis, bass; and Al Dreares, drums, Thompson’s fellow horns are trumpeter Dave Burns, alto saxophonist

Danny Turner, baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne and trombonist Benny Powell—all among the elite of the post-bop New York scene. In Thompson’s writing, as in his playing, blues feeling predominates even when the composition’s form, as in “Firebug,” is that of a 32-bar song. “The World Awakes,” which in the sixties served Thompson as a sort of anthem, is a minor blues. His soprano solo combines intensity, light-heartedness and the penetrating tone that was an important element of his distinctiveness on the instrument. Jones (pictured left) solos, impeccably, of course, but Davis’s 12 choruses of walking bass practically steal the performance.

Still on soprano, Thompson eases into a relaxed solo, followed by Davis and Jones before the ensemble gives us the first passages of Thompson’s intriguing arrangement. The voicings reflect his accumulation of bebop wisdom as well as his admiration for the French impressionists. His first tenor saxophone feature on this disc is “’Twas Yesterday,” highlighting what the late critic John S. Wilson once described as Thompson’s “soft, furry, intimate tone.” “Firebug” brings spirited solos from Jones and Payne, a virtuosic and often very funny one from Powell, eight essential bebop choruses from the underrated Burns, then Thompson on tenor in a long solo in which each idea grows into the next; musical story-telling founded equally on logic and emotion. The ensemble accompanies Dreares, leaves him a few bars of solo space, then negotiates the intersecting contrapuntal lines of Thompson’s arrangement to an abrupt conclusion that triggers chuckles on the bandstand and in the audience.

The second CD contains a 1965 quartet date broadcast from the Half Note in lower Manhattan. Thompson’s accompanists are bassist George Tucker, drummer Oliver Jackson and the excellent little-known pianist Paul

Neves (pictured right), who appears here in one of only two recordings

I’m aware of his having made. The other was Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s Spellbound,

which disappeared for a time but is again available. If anything,

Thompson is even more fluid on soprano in this version of “The World

Awakes,” spurred by Neves’ emphatic comping. The pianist’s solos and his

supportive accompaniment throughout make the attentive listener aware

that we lost a substantial musician when he died in Puerto Rico in the

1980s. He was in his early fifties. A native of Boston, Neves was the

brother of bassist John Neves, who worked with Jaki Byard, Stan Getz and

the big bands of Herb Pomeroy and Maynard Ferguson.

Neves (pictured right), who appears here in one of only two recordings

I’m aware of his having made. The other was Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s Spellbound,

which disappeared for a time but is again available. If anything,

Thompson is even more fluid on soprano in this version of “The World

Awakes,” spurred by Neves’ emphatic comping. The pianist’s solos and his

supportive accompaniment throughout make the attentive listener aware

that we lost a substantial musician when he died in Puerto Rico in the

1980s. He was in his early fifties. A native of Boston, Neves was the

brother of bassist John Neves, who worked with Jaki Byard, Stan Getz and

the big bands of Herb Pomeroy and Maynard Ferguson. Thompson remains on soprano for a gentle exploration of “What’s New,” demonstrating the artistic strength to be found in restraint. Following the first chorus of Tadd Dameron’s “Lady Bird,” Neves drops out for a few choruses while Thompson indulges in one of his favorite tenor saxophone pursuits, strolling with bass and drums. When Neves reenters, the passion builds during a dozen more Thompson choruses and seven from Neves. Tucker makes the most of his only solo opportunity of the set. The last piece ends with a drum roll and Thompson’s “Paramount on Parade” intro on soprano. They set the stage for an incendiary “Strike Up the Band.” Thompson, on tenor, is the only soloist except for a sequence of power exchanges with Jackson, who is finally allowed to give full rein to his skills. It is a reminder of the versatility of a drummer who was equally effective in the range of jazz styles from traditional to modern.

The album recalls that, for all of the frustration he faced, the bitterness he felt and his sad end, Lucky Thompson’s music transmitted confidence and joy. In his brief conversations at the Half note with broadcast host Alan Grant, Thompson’s intelligence and gentlemanliness are apparent.

In the CD’s booklet, Noal Cohen’s comprehensive notes provide an extensive history of Thompson’s career. The 44-page booklet has several photos of Thompson, pictures and brief bios of the sidemen, and information about the Little Theater concert and the Half Note broadcast.

(Photo of Paul Neves by Katherine Hanna courtesy of Irene Kubota Neves)

Rare photo of Lucky Thompson on flute, Paris, 1958 (photographer unknown)

Rare photo of Lucky Thompson on flute, Paris, 1958 (photographer unknown) Bassist Jacques Hess (left), Lucky Thompson and drummer

Bassist Jacques Hess (left), Lucky Thompson and drummer