SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER THREE

MAX ROACH

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BEN WEBSTER

(September 7-13)

GENE AMMONS

(September 14-20)

TADD DAMERON

(September 21-27)

ROY ELDRIDGE

(September 28-October 4)

MILT JACKSON

(October 5-11)

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN

(October 12-18)

GRANT GREEN

(October 19-25)

ROY HARGROVE

(October 26-November 1)

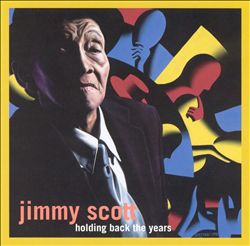

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT

(November 2-8)

BLUE MITCHELL

(November 9-15)

BOOKER ERVIN

(November 16-22)

LUCKY THOMPSON

(November 23-29)

Little Jimmy Scott

(1925-2014)Artist

Biography by William Ruhlmann

Singer Jimmy Scott (aka Little Jimmy Scott)

had an unusual career conditioned by his physical limitations and

record company machinations that sometimes prevented him from being

heard, but he mounted a major comeback late in life. He was born one of

ten children to Arthur and Justine Scott in Cleveland, Ohio, on July 17,

1925, and he first sang in church. His mother was killed in a car

accident when he was 13, leaving him to be raised by foster parents. He

suffered from a rare hereditary condition called Kallmann's Syndrome

that prevented him from experiencing puberty, such that he stopped

growing when he was less than five feet tall and his voice never changed

from a boy soprano's.

He began singing professionally during the 1940s, touring in tent shows. In 1948, he joined Lionel Hampton's band, and he made his recording debut in with Hampton

for Decca Records in January 1950. One of the songs from those

sessions, "Everybody's Somebody's Fool," entered the R&B charts in

October 1950 and became a Top Ten hit. Scott left Hampton in 1951 and went solo. An appearance with Paul Gayten's

band at Rip's Playhouse in New Orleans that year was recorded by Regal

Records, but went unissued for 40 years until Specialty Records released

it in 1991 as Regal Records Live in New Orleans From 1951 to 1955, Scott recorded singles for Royal Roost, Coral, and Roost Records.

Then, in 1955, he moved to Savoy Records, which issued his first LP, Very Truly Yours,

that year. In 1957, he switched to King Records for a series of

singles, but in 1959 he returned to Savoy, which issued his second LP, The Fabulous Little Jimmy Scott, in 1960. In 1962, he signed to Ray Charles' Tangerine label and recorded his third album, Falling in Love Is Wonderful, but it had to be withdrawn shortly after its release when Savoy claimed he was still under contract there. This debacle led Scott

to leave the music business (he eventually took a job as a shipping

clerk at the Sheraton Hotel in Cleveland). In 1969, he recorded his

fourth album, The Source, for Atlantic Records, and in 1975, he returned to Savoy for his fifth LP, Can't We Begin Again. But neither effort achieved commercial success, and he continued to work outside music.

Scott began performing in clubs again in 1985. In 1990, backed by the Jazz Expressions, he returned to the recording studio for J's Way Records. One of his longtime supporters was songwriter Doc Pomus, and when Pomus died on March 14, 1991, the by-now 65-year-old Scott sang at his funeral. The performance was heard by Seymour Stein, the head of Warner Bros. Records-distributed label Sire Records, who signed Scott to a contract. This led to a major comeback. In June 1991, Scott (billed as James V. Scott) appeared in an episode of director David Lynch's offbeat television series Twin Peaks. (Scott later appeared in the films Scotch and Milk [1998] and Chelsea Walls [2001].) He sang on Lou Reed's Sire album Magic and Loss, released in January 1992.

His own new album, All the Way (the first on which he was billed simply as Jimmy Scott),

was released by Sire/Blue Horizon/Warner Bros. later in 1992 and

reached number four on Billboard's jazz album chart, also earning a

Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Vocal Performance. The same year, he

sang on the soundtracks for the films Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me and

Glengarry Glen Ross. In 1993, Rhino Records delved into the Atlantic

Records archives to assemble Lost and Found, containing some unreleased material from sessions in 1972; the album reached number 14 in the jazz charts. Scott's next album of new material, Dream, was released by Sire/Blue Horizon/Warner Bros. in 1994 and reached number eight in the jazz charts. Heaven, an album of gospel and spiritual songs, appeared in 1996 and reached number 19 in the jazz charts.

That concluded Scott's Warner Bros. contract, but he recorded Holding Back the Years for the Artists Only! label in 1998, and it reached number 14 in the jazz charts. In 2000, he moved to Milestone Records, and Mood Indigo reached number 17 in the jazz charts. Despite passing his 75th birthday, he continued to record frequently, releasing Over the Rainbow in 2001, But Beautiful in 2002, and Moon Glow in 2003. All of Me: Live in Tokyo appeared in 2004. Savoy Jazz issued All or Nothing at All in 2005. Jimmy Scott died in June 2014 at his home in Las Vegas, Nevada; he was 88 years old.

Jimmy Scott

Jimmy Scott

The life of Jimmy Scott is not one of meteoric stardom but a journey that has taken nearly seventy years to find its much deserved success.

One of ten children, James Victor Scott was born in Cleveland, Ohio on July 17, 1925.

The first time Jimmy sang on a public stage was at school when the teacher had him sing the lead in a play “Ferdinand the Bull”, after that she always had him do the leads. He was only 12 years old when he became known as a singer around Cleveland. While in his teens a Comedian saw the potential in Jimmy, he was Tim McCoy from Akron. Whenever Tim got a “gig” around Northeast Ohio, he would take Jimmy along with him on the bill. Jimmy would sing at different clubs, they would sneak him out before the cops arrived, because he was not only under age, but looked even younger than his actual years. Later Jimmy produced the Summer Festivals, a group of talented youngsters, like his friend jazz baritone singer Jimmy Reed and dancer Barbara Taylor, that would put on shows all around the area.

They also worked and put on shows at the Metropolitan Theater where the big bands would come in to play, Jimmy set up a concession to supply the Artists with soap, clean towels, and toiletries. He was hired by the dance troupe, “The Two Flashes”, Jimmy took the job to be close to show business, its players, and the stage. While in Meadville, PA. they were working with some of the greatest jazz musicians of the day, Lester Young, Slam Stewart, Ben Webster, Papa Jo Jones, Sir Charles, etc…The music was jumpin' and so was Jimmy, he asked the dancers to see if the band would let him do a couple of numbers, they said ok. Jimmy sang “The Talk of the Town” and “Don't Take Your Love Away”, the audience went crazy showing their love for Jimmy and the thunderous applause was deafening. Every time the band ran into Jimmy, they'd ask him to come up on stage a do a couple numbers. Some of the early big bands Jimmy enjoyed were Count Basie's Band, Erskine Hawkins, and Father Earl Hines, but Lester Young was his favorite tenor sax player. He joined Lionel Hampton's Band in 1948, where he discovered the vibraphone and the strings, Jimmy said “it helped him to learn the beauty of the song and encouraged him to sing”. Lionel was a mentor to Jimmy and the one who tagged him with the stage name, “Little Jimmy Scott”, at the time he was 23, only 4'11”, thin, and very young looking. Jimmy said it was a gimmick for Lionel's show, but it wasn't too many years later that you started hearing more singers take their cue from Jimmy's stage name and call themselves Little So & So.

Jimmy met Estelle “Caldonia” Young in the early 1940's; she took Jimmy on her road show as the featured singer. Caldonia became almost a surrogate mother to Jimmy, having lost his own mother at age 13. “Caldonia's Revue” traveled the southern circuit to the east, they put up their own stages in the rural areas. There were featured male and female vocalists, tap dancers, comedians, an M.C. and Caldonia herself, she was an exotic shake dancer and contortionist. It was essentially like a touring vaudevillian tent show. Some of the others who worked with Caldonia at one time or another were Ruth Brown, Big Maybelle, Elie Adams, and Jack McDuff. Caldonia took Jimmy along with her to do a special performance at Gamby's in Baltimore in 1945, where he met up with his friend Redd Foxx who was appearing at Gamby's also. They went over to the Royal Theater to see Joe Louis. Redd and Joe told Jimmy he should be in New York performing instead of traveling around to those small towns.

They convinced him he could make it on his own, the way he sang. So they talked to Ralph Cooper who called up Nipsy Russell, the M.C. at the Baby Grand in Harlem and arranged for Jimmy to get a one week booking. Jimmy sang that one week and they kept him on for 3 more months! Billie Holiday would show up nightly while in town to listen to Jimmy. Doc Pomus was in the audience during that first week and wanted to meet this amazing singer, Jimmy said “sure” and they became fast friends. Doc took Jimmy home to have dinner to meet his parents and little brother Raoul Felder, he also showed Jimmy how to get around on the N.Y. subway system. Their friendship lasted over 45 years. Jimmy sang at Doc's funeral in 1991. It was there that record label owner Seymour Stein heard Jimmy sing and practically signed him on the spot, thus the beginning of Jimmy's re-emergence as a singer with his Grammy nominated comeback album “All The Way”. At age 67 he began to tour the world, where he was introduced to new appreciative audiences and legions of new young fans !! Now the press refers to him with reverence as the Golden Voice of Jazz, the Legendary Jimmy Scott.

Written by Jeanie Scott

After a long climb, things are really looking up for Jimmy Scott. He's established a dedicated international audience through triumphant tours of Europe and Japan; he's been the featured subject of a Bravo Profiles television special, and of an in-depth biography by award-winning author David Ritz ( Faith in Time: The Jazz Life of Jimmy Scott, due out in the fall of 2002 from Da Capo Press). Now, with But Beautiful, Jimmy Scott fleshes out a persuasive portrait of his jazz mastery and storytelling. “It represents a logical evolution of our Milestone sessions,” concludes Barkan, “and everything Jimmy has worked so hard for.” Mr. Scott adds a final coda: “The record is quite simply exquisite, and I really am as proud of it as anything I've ever done in my life.”

On December 31, 2003, Jimmy married Jean McCarthy at the Covenant Community Church in Cleveland, Ohio. Jimmy said, “...he wanted to start the New Year off right, that every New Year after that would be my special day.” The couple honeymooned in London, Istanbul, Paris, Austria and Monaco.

In 2004, Jimmy has seen the release of an Independent Lens documentary “Jimmy Scott, If You Only Knew”, that won the 2004 Audience Award. A new 28 song CD set compilation, “The Definitive Jimmy Scott: Someone To Watch Over Me” and a single CD, “All Of Me: Jimmy Scott- Live In Tokyo “

Scott himself has always focused his creative energy on the challenges with which this life has presented him. “Ya gotta go on,” he says, and not resignedly, “fortunately, I had the music to comfort me.” He has said that there isn't any disappointment in heaven, and when asked what this means, he replies, “Heaven is what you make it. You can make it hell here on earth, or you can make it heaven.”

Of the success he's achieved relatively late in life, Scott says, “I'm pleased now that (my voice) is pleasing to people. In a way, I feel like now maybe people will hear what I have to offer, whereas before the music never got to a level where all people had access to it. “All I can do is give what I really feel.”

https://www.nytimes.com/1985/05/05/arts/little-jimmy-scott-seeks-to-evoke-a-happier-past.html

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT SEEKS TO EVOKE A HAPPIER PAST

by George Goodman

See the article in its original context from

May 5, 1985, Section 1, Page 82

May 5, 1985, Section 1, Page 82

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT, the jazz singer who mesmerized fans of the Lionel Hampton band during the 1950's with his impassioned treatment of ballads and then largely dropped out of sight, returned to the New York scene last week for the first time in nearly 14 years.

Tonight,

Mr. Scott concludes an engagement at the Blue Note, 131 West Third

Street, where Jon Pareles, writing in The New York Times, likened him to

''a great Chinese calligrapher'' rendering his songs in ''spontaneous,

impassioned, irrevocable strokes.''

Mr.

Scott's sonorous soprano first drew acclaim when, as a child, he sang

in a Cleveland church choir at his mother's urging. And he later

developed the highly emotive approach that influenced singers as varied

in style as Nancy Wilson and Johnny Ray.

''They

used to sit in the front row of the Apollo Theater, uptown, when I sang

with the Hampton Band, from 1948 until 1953,'' Mr. Scott said in an

interview.

He

stopped singing in 1956, he said, because of his disillusionment over

what he called the exploitive treatment he faced at the hands of

managers and promoters. Bad luck dogged him after he returned to

Cleveland; while working as a shipping clerk, he was involved in an

accident that seriously injured his back.

''I

decided to sing again after settling in Newark in 1982,'' he said. ''I

had a burning desire to sing and lots of encouragement from my new wife,

Earlene. Now I am working, and it feels just as wonderful as I had

dreamed it would.''

IN ''Uptown Comes

Downtown,'' a special two-week Blue Note program that features other

Harlem-based musicians with whom Mr. Scott has worked, the singer said

his fellow performers have set out to evoke the ''scintillating'' mood

of Harlem during what they consider happier days. Charles Earland, whose

pyrotechnic keyboard style inspired his nick-name, ''The Mighty

Burner,'' will open Mr. Scott's performance for the last time tonight.

Next week, the program will feature the saxophonist Willis (Gatortail)

Jackson and (Brother) Jack McDuff, the organist.

Though

their names were never so well-known among white fans, during the

1950's all were top attractions in black nightclubs and concert halls,

including Count Basie's, The Club Barron, Small's Paradise, The Apollo

Theater and Minton's.

''We worked what

used to be called the chitterlin' circuit,'' said Mr. Earland. ''Most

of us didn't have big hit records, but we were good and people packed

the clubs to see us.'' Beyond Harlem, the performers were seen in

Brooklyn and New Jersey and on stages as far away as the Regal Theater

in Chicago, McKie's in Detroit, the Blue Room in Kansas City and the

Five-Four Ballroom in Los Angeles.

In

the years since the economic and social decline of Harlem and other

black communities, their careers have seen ups and downs, mostly because

of the loss of places to work.

''A

lot of places just dried up,'' said Mr. Jackson, a native of Miami and a

protege of such tenor stars as Herschel Evans and Illinois Jacquet. Mr.

Jackson, who first arrived in New York with the ''Cootie'' Williams

band of 1948, noted that during the late 1960's ''Harlem lost all kinds

of business, even barber shops and restaurants.''

Mr.

McDuff, who arrived in 1958 after working in Chicago and settled in

Harlem, said he has lived there ever since. Now 59, the organist said:

''I've been running up and down the road, and baby, it gets pretty

rough. I've done some recording, too. One guy wanted me to do a 'rap'

record and then he said, 'McDuff, we're doing you wrong. We want you to

play straight-ahead jazz.' A lot of it has been too commercial for my

taste. What I miss most are the days when I worked at Minton's and guys

like Kenny Dorham, 'Philly' Joe Jones and Stanley Turrentine would drop

by and sit in.''

Mr. Scott, who said

he arrived here in the late 1940's to work at The Club Baby Grand, had

similar recollections. The singer said that after hours he and Milt

Jackson, the vibraphonist, would play at Clark Monroe's Uptown House,

where Billy Eckstein and Billy Daniels would frequently drop in to

perform. ''It was my college education,'' said Mr. Scott, who is now 60.

Mr.

Earland, who is 43, arrived on the Harlem scene just in time to catch

the last glimmer of excitement. ''I was helped a lot by McDuff and Jimmy

Smith,'' he said of the organist who left Harlem to open his own

nightclub in the San Fernando Valley.

''I

would be happy just playing jazz, but I got involved in independent

record production because I could see the handwriting on the wall,''

said Mr. Earland, who lives in Philadelphia.

Mr.

McDuff said that this week at the Blue Note he and Mr. Jackson would

team up for the first time since 1960 ''to play the bluesy kind of jazz

that used to be standard stuff uptown - it was music that was smokin,'

but music that has a good feeling without being so complex.''

A version of this article appears in print on , Section 1, Page 82 of the National edition with the headline: LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT SEEKS TO EVOKE A HAPPIER PAST. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

Remembering Little Jimmy Scott

Little Jimmy Scott was a singer's singer. Let's start with what Nancy Wilson said about him:

"There would be no Nancy Wilson were it not for Little Jimmy Scott. I owe all that I am and all that I have to this man's singing style...when I hear Jimmy, he touches me with his unique ability for phrasing. The emotions riding on the timbre of his voice. With that all-important ability to tell a story and you get it the first time you hear it. What a gift!"

And as if that weren't enough of an encomium, Scott performed at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993, singing "Why Was I Born?". Forty years before, he performed that very same song at President Dwight Eisenhower's 1953 inauguration. Two presidential inaugurations: the first Republican, the second Democratic.

- Madonna said he was the only singer who'd ever made her cry.

- Billie Holiday said he was her favorite singer.

- Quincy Jones, who worked with Scott in the Lionel Hampton band, said, "Jimmy would tear my heart out every night with his soul-penetrating style."

- Liza Minelli said, "Every singer should get down and kiss his feet."

- When Marvin Gaye was in self-imposed exile in Belgium, he had only one record album spinning continuously: Jimmy Scott's Falling In Love Is Wonderful.

So why isn't Little Jimmy Scott more well known?

Probably because he had so many ups and downs in his career. His first Top 10 hit came in 1949, "Everybody's Somebody's Fool" with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. He did not get credit on the song (probably no royalty checks either). He had an unusually high voice, brought about by a hormonal deficiency known as Kallmann's syndrome, which prevents its victims from ever reaching puberty. He was small of stature, hence the qualifier "Little". His voice never lowered in adolescence and adulthood, he remained under 5' tall until into his 30's, when he suddenly shot up to a height of 5'7". His voice was often compared to Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday's. In fact, many who heard him thought a woman was singing. Most record labels wanted more testosterone in their male pop and jazz singers, a more "manly" sound: think of baritones like Billy Eckstine and Johnny Hartman. That was the sound they wanted. Scott would never become anybody's male heartthrob. On the other hand, Scott's high alto voice probably influenced more female singers then male: Shirley Horn, Nancy Wilson, Gloria Lynne, Abbey Lincoln to name just a few.

The magic and power of Little Jimmy Scott lies in the emotional power of his singing. He made you believe the words and the emotions behind the songs. He was convincing. He was feeling it all too.

Scott was born James Victor Scott in Cleveland, Ohio. He lost his mother in a car accident when he was 13 years old (he was 1 of 10 children in the Scott household). His father left shortly after his mother's death and all the kids were raised in foster homes.

After his top hit with Hampton, Scott entered into a contract with Savoy Records. A 1962 album called Falling In Love Is Wonderful, produced by Ray Charles and featuring the Gerald Wilson orchestra and arrangements by Marty Paich, was not released because Savoy Records said he was under an exclusive lifetime contract with Savoy. Savoy's president, Herman Lubinsky, was known as an 'arrogant bully', so this isn't surprising. The album has been reissued on CD by Rhino Records. Scott's singing career was derailed for more than 20 years because of the Savoy snafu.

And so Jimmy Scott abandoned his singing career for a decade, 1960s- 1970s a shipping clerk, waiter, hotel worker, and ward captain for the Democratic Party. He once told NPR that "there comes a time in your life where you have responsibilities and family involvements, survival, and you gotta do what you have to do: get a job, pay the rent, try to keep yourself alive".

All that changed when he appeared to sing at the funeral of his old friend Doc Pomus. Sire Records' president Seymour Stein was there and signed him to a Warner Brothers contract. The result came in 1992 with All The Way, which sold 50,000 copies and earned him a cult following in Europe and Japan. The hit album also lead to string of other popular albums produced by Todd Barkan, Craig Street, Mitchell Froom, and others. Director David Lynch was also a fan and gave Scott a cameo appearance on the hit TV series Twin Peaks finale, singing "Sycamore Trees".

And so his last 20 years were comeback ones and he finally got his due. In 2007, Scott was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Award, the nation's top honor. When receiving the award, Scott commented, "There's times, in certain songs, that I might be in my own world and who cares about who's out there, you know? You have a job to do so you do that job of singing that song or telling that story because that's what you're doing. If you're singing, you're telling a story. So to tell it and tell it right, that's it."

And despite the down years, Little Jimmy Scott bore no bitterness about many missed opportunities. And despite the hard living of heavy smoking and drinking, he beat father time, passing away at the ripe old age of 88. He will be buried in his hometown of Cleveland.

Here is a clip of Scott singing his comeback song, "All The Way". Prepare to feel something.

Rhythm Planet Playlist: 6/20/14

- Little Jimmy Scott / Why I Was Born? / Everybody's Somebody's Fool / Grp Records

- Little Jimmy Scott / All The Way / All The Way / Warner Bros.

- Little Jimmy Scott / Everybody's Somebody's Fool / Everybody's Somebody's Fool / Grp Records

- Little Jimmy Scott / If I Should Lose You / Falling In Love Is Wonderful / Rhino

- Little Jimmy Scott / Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child / Lost And Found / Rhino

- Little Jimmy Scott / Heaven / Heaven / Warner Bros.

- Little Jimmy Scott / It Shouldn't Happen To A Dream / Dream / Warner Bros.

- Little Jimmy Scott / Imagination / Mood Indigo / Milestone

A Quietus Interview

If You Only Knew: 'Little' Jimmy Scott Interviewed

by Nicholas Abrahams

December 8th, 2011

Nicholas Abrahams talks to "Little" Jimmy Scott about his music, his muse and singing for David Lynch

I asked Antony Hegarty of Antony and the Johnsons what he makes of Jimmy Scott, the 86 year old jazz legend with the voice of an angel, with whom he has shared the stage at the Carnegie Hall.

"Jimmy Scott, peerless, spirit brother of Billie Holliday, sings like a sobbing diamond. Now a great elder, he is untouchable, his sense of timing is mystical."

It is true that, in more ways than one, Jimmy is Billie Holliday's 'spirit brother". She said he was her favourite singer. When I spoke to Jimmy at his home in Las Vegas, he was sleepy, but perked up when I mentioned his one-time muse.

"Billie was more like family to me... I knew she had a rough life and she struggled through it and it was a struggle for her, but her associations, friends that she had, and you couldn't pull her away from them - they drew her into using dope and all that, and it kinda hurt to see her be taken advantage of in that way. But, oh yes, I loved to hear her singing, it was quite an attraction to me, being a young man and all, listening to her and learning from all those people...."

This month, one of the most unique voices of our time will be heard in London, on the 17th and 18th December at St Stephens Hall in Hampstead. Small in stature, but huge in style and charisma, "Little" Jimmy Scott has one of those voices that once heard is never forgotten. Ask Madonna, who said that Jimmy's voice was "the only singer who makes me cry", or Nick Cave, who asked Jimmy to perform at his wedding party, or the New York Times, who dubbed Jimmy "the most unjustly ignored American singer of the 20th century".

Lou Reed said that seeing Jimmy sing was "like seeing Hamlet or Macbeth all rolled up into a song", and that "we all bow at the altar of Jimmy Scott", consequently employing him as a backing singer on tour. Word has it that Jimmy was such a mellowing influence on the notoriously grumpy Reed that his band begged Jimmy to stay touring with them for of long as possible, which I mention to Jimmy.

"Well, ha ha ha, Lou is.. something else! It was... showbusiness! Just another job that I had got in the business, and it was totally different to what jazz was all about. I wasn't into what he was doing, it wasn't music that I had a love for but it was... something else, it was... interesting! And it gave me an opportunity to understand another person... which is a challenging business..."

Imagine all of the interview being conducted in a leisurely drawled voice by Jimmy, so that it is never certain that the end of a sentence, or thought... will... be ... reached... a stroll through a conversation as close to his manner of singing as anything, as if he is always behind the beat, whether on stage or off. The pauses were many and lengthy....

Jimmy's uniquely androgynous voice is thanks to being born with a medical condition known as Kallman's syndrome, a now curable disease, which meant that he never passed through puberty. Consequently has a singing voice which is part neither quite male, nor female, but floats pleasingly and ambiguously in between. What on one hand is a curse - Jimmy, married four times, was unable to father any children - is also a blessing, giving him a natural pitch closer to a castrato than any other singer.

"What can I say? I was born with it... and as far as marriage, it was a problem, of course. But my mother taught me to never drop my head about it. And it was never talked about, never discussed amongst the family".

But he combines that otherworldly voice with an out of space delivery, so sleepy and behind the beat that sometimes one worries the next word might not be forthcoming. It is a delivery unique in jazz. How did he develop his laidback vocal style?

"I've always liked the drums, as an instrument. In school it was my instrument, I played drums in a marching band and I got a connection with the timing from playing the drums and... it was always there and I used it accordingly... and it has never bothered me, or interfered with what I do as far as singing, so I continue to express myself in the manner that I do, and the way that I do when I sing.. I just continue doing it... what can I say?..."

Has this ever been a problem for those playing with him?

"All the great musicians, like Yardbird, Dizzy, and all of them, I came up with that thing... and they covered me very well... I have always accepted their interest in my timing, and I've never had a problem with any of the bands that I worked with. Fortunately it all panned out for the good for me.. as far as the music goes!"

These casual name drops of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker as Jimmy's musical collaborators points to the caliber of musicians he has performed with. Each generation seems to need to rediscover Jimmy for themselves, whether it was Ray Charles back in the 1960s or Antony Hegarty today.

"I was raised in a spiritual church as a kid, and all our singing in church was in a gospel style. Gospel was the first music I sang, and my mother taught me to sing. Gospel is as much a part of Jazz singing as anything else. It's creativity being expressed and it is within the person who is doing it, knowing what they can say, it is born in most of the figures that sing with the gospel spiritual attitude." Other influences he mentions are Paul Robeson and Judy Garland.

Another influence, but of a more sartorial nature, was Nat King Cole:

"He was another one I could learn from... He was a dresser, liked to dress! Oh yeah... he was a sharpy out there! I remember when he got a contract for Murray Hair Cream, they had a picture of him on the can of hair cream and it stayed there for years... it might still be in some stores today, Murray's Pomade, oh yeah! Anyhow, he taught me how to dress just so for your public. In a way presenting yourself to yourself to your public, for me, is show business. And I learnt how to keep a wardrobe for showbusiness from being around him. He dressed neat and simple, he didn't go for extremes, nor did he go to any ignorance in dressing himself. You have young artists today who dress ignorantly... money can buy you a lot of things but it can't buy you a natural attitude, that god given attachment that you have in presenting yourself, much like we said a while ago about the spiritual element in our singing, that keeps us away from the ignorance that is going on in the business."

Jimmy's career took some disastrous turns, as an early contract he signed with Savoy Records came back to haunt him in the following decades, leading to the release and sudden recall of two breakthrough albums, firstly his 1962 Ray Charles produced album Falling in Love is Beautiful and then The Source in 1969. These bitter blows to Jimmy's career are still evident in his thoughts today.

"(Savoy MD) Lubinsky didn't promote the things that I did! And even today, I have people request songs that I recorded on his label, Savoy... People will ask me: "Why don't you sing this no more?" And I say "Well...!" You know, with respect, I try to explain that it's not in my book anymore! I'm trying to build myself, you see.. and I have to explain to them without hurting anyone or trying to destroy anyone. OK, I had problems, but I don't have to use those problems to hurt anyone."

The necessities of life mean Jimmy, well into his 80s, is still singing.

"I'll be doing this as long as possible, until I get satisfaction, you know... for my welfare, income, I will be doing it until I can afford to relax. All my life I've worked somewhere... When I wasn't singing or didn't have dates, I did my best to get little jobs to keep things caught up. You know, I had to pay rent and other jobs and I would get little jobs, yeah, in hotels, and other places, restaurants, in a nursing home, I did those things and they were necessary to keep my life in order and pay my bills as I went by."

This disappearance from public life led many people to believe that Jimmy Scott had died. Fate intervened when, in 1991, Seymour Stein heard Jimmy singing at the funeral for their mutual friend Doc Pomus, and signed him immediately. When Jimmy's relaunch yet again appeared to be going nowhere fast, David Lynch stepped in, featuring Jimmy in the final episode of Twin Peaks. Lynch says that Jimmy "does things to a song that nobody else does. So he's an original, an original voice. It's haunting. And it's so pure soulful."

Yet when I asked Jimmy about Lynch he sounded wistful, and just a little bit let down.

"It was nice working with David Lynch, who was interested in what I was doing... but I don't see those folks anymore! And I sort of miss that atmosphere of the interest they had in what I was doing, and we were trying to develop and create interest in my songs and my way of singing the songs. David Lynch... well, I miss that kind of thing! There are directors I would like to work with, Martin Scorsese... and there are a couple of directors interested in my life story..."

Despite such a fragmented career and life, Jimmy stills seems to revel in future possibilities.

"I mean, you give out, but you don't give up! That's my method and my motto for life.... you give out with all you have, your heart, your soul.. and you try to do the best to make it enjoyable for the audience..."

Jimmy doesn't want to give details about his future plans, keeping deliberately vague and open ended:

"It's about the music, and that's the thing… it's music and you want to get in and be a part of what it is... there's just something that draws you deeper into the music. This, THIS is the thing. The music teaches you how to live, how to be, how to treat others, how to respect others in the business and... " [Jimmy's wife/managers voice can be heard somewhere in the background] ".. and how to love my wife, ha ha ha! I had to get that in there! Because she'll chop my head off!"

The Ballad of Little Jimmy Scott

by

See the article in its original context from August 27, 2000, Section 6, Page 28

There

are various ways to meet celebrities in this media age, many of them

involving publicists looking at their watches and saying that the

Musician or the Actor has been unavoidably delayed. So it is a little

surprising to be greeted promptly at the airport in Cleveland (Cleveland

itself being a departure from standard practice) by the slight, smiling

figure of the jazz singer Jimmy Scott. He is holding up a cardboard

sign with my last name inked in as if he is an especially cheerful limo

driver charged with taking me to see somebody really important. ''Hey,

baby,'' he greets me, ''how was the trip?''

Given

that Scott's first and only bona fide hit, the ballad ''Everybody's

Somebody's Fool,'' was recorded in 1950, you wouldn't expect him to be

overburdened with the trappings of success. Still, ever since a quartet

of albums in the 90's, Scott has held a special fascination for music

cognoscenti and show-business notables. ''Jimmy Scott is the only singer

who makes me cry,'' says Madonna, who gave him a cameo spot in one of

her videos. Lou Reed had Scott sing backup vocals on a track from his

1991 ''Magic and Loss'' album. He may well have put the Scott

genuflection competition out of reach: ''It's like seeing Hamlet or

Macbeth all rolled up into a song.''

The

Lou Reeds and Madonnas of this world are presumably attracted to Scott

because he remains, in spite of their pro bono publicity, perhaps the

most unjustly ignored American singer of the 20th century. But the

appeal of the man David Lynch featured in the final episode of ''Twin

Peaks'' is also about something else. At worst, Scott's newer fans are

drawn to a superficial freakishness, the voice that is pitched well up

in the conventionally female range and the hairless face, for decades

perpetually boyish, that in recent years has taken on the noble,

withered aspect of a tortoise. At best, one could imagine certain

show-business types, aware of the smoke and mirrors that go into their

own celebrityhood, simply wanting to be in the presence of the real

thing.

The humble limo driver guise

notwithstanding, these are thrilling make-or-break days in the career of

James Victor Scott, now 75. If in the 90's he went from presumed-dead

status to musical cult figure and celebrity pet, at the millennium he

has a shot at becoming, well, who knows, something more. The most

compelling evidence of a Scott renaissance is ''Mood Indigo,'' released

in May, a collection of ballad standards that finds the singer in his

best voice of recent vintage and in the company of worthy supporting

musicians like the alto saxophonist Hank Crawford and the pianist Cyrus

Chestnut. Not coincidentally, Scott, for perhaps the first time in his

long, harum-scarum career, has empathetic and competent management

behind him, as well as an enthusiastic, if modest-sized, new record

label in Milestone. Todd Barkan, a respected jazz producer, has worked

his longtime connections in the Japanese jazz world to help create for

Scott a nascent Far Eastern stardom -- steady touring punctuated by

regular standing ovations. Having just finished a sold-out engagement at

Birdland in Manhattan earlier this month, it's clear the singer is on a

roll at home as well.

As

it turns out, Scott doesn't just play the part of a limo driver; he

also comes armed with a real limo, his boatlike 1992 Lincoln Town Car.

Scott's license has lapsed, so he hands over the keys to his younger

brother, Kenny, a retired factory worker whom the singer recently put on

the payroll as his right-hand man. Kenny and I take the front seat;

Jimmy prefers the back, where he can keep up a steady conversational

patter and dandle Princess, a 2-year-old pug with bulging black eyes.

''She's the lady of the house,'' Scott says. A veteran of four failed,

turbulent marriages, Scott these days reserves his most effusive

attentions for Princess. ''She likes the music on the radio. She gets so

comforted.''

Jimmy Scott speaks,

unstoppably, in a high-pitched voice, roughened and phlegmy after a

lifetime of smoking and drinking, with none of, for instance, Michael

Jackson's girlish lilt. It's a hip voice, a match for the singer's

1960-vintage street-cat rap. Almost everyone is ''baby'' to his face,

usually ''hey, baby.'' Someone not present is customarily referred to as

''a hip little cat'' (a nice turn of phrase from someone who has never

completely shed the moniker Little Jimmy Scott). That lingo mixes

effortlessly with his core vocabulary of show-biz abstractions:

''expressions'' (his East Coast working band is named the Jazz

Expressions), ''dramatics,'' ''stylings'' and ''flair.'' A typical Jimmy

Scott pronouncement will run something like this: ''Yeah, baby,

Cleveland used to be a hip little town for the jazz expression but then

that rock 'n' roll flair came in. You dig?''

Scott's

uniqueness goes well beyond his redoubtable verbal flair. From birth,

Scott was marked as ineluctably different, afflicted with a hormonal

disorder, Kallmann's syndrome, that interferes with normal sexual

maturation. In Scott's case, it gave him that boy's alto voice, which

is, of course, what made him Jimmy Scott. ''Well, I learned that it was a

gift,'' he says after a pause, ''that I was able to sing this way.''

Not that he always embraced it. He was in his 30's before he gave up

hope that his range would drop, not so preposterous when you consider

that Scott was then still routinely being mistaken for a teenager.

''Many times,'' he says with a laugh, ''I'd think, I'd love to try this

in a lower register . . . but then after a while you think, Sing with

what you got.''

It has been enough. Over the years, Scott has invented his own deeply theatrical brand of American art song, the connection to his own emotional pain so palpable that the lachrymose standards in his repertory (''Why Was I Born?'' ''Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,'' ''When Did You Leave Heaven'') sound like episodes in an autobiographical melodrama.

The sound of the male voice in the higher registers has always exerted its own special pull. Think of the all-boy choirs, of Irish tenors and, disconcertingly, of the castrati in the 16th through 18th centuries in Italy. Jimmy Scott is, vocally, a natural castrato. In the 1960's, at the height of his vocal powers, Scott possessed what was arguably the most ravishing, penetrating and powerful vocal instrument in American popular music. In every other respect, Kallmann's syndrome was an unqualified drag.

''Even

today,'' Scott says, ''cats in the grocery store say, 'Miss, what do

you want?' 'Cause I have no trademarks. But I learned to ignore it. No

sense of making a big issue out of it. When I was young and ignorant --

What do you mean [expletive]! Cut you, hell, I'll shoot you!' It's

something else, baby. It's something else.' ''

For

Scott, gender or sexual ambiguity is what's in other people's minds.

He's a heterosexual male; he's pretty clear about that. But whether he

likes it or not, Scott's sound and his look strike the gender notes in

between the piano keys, the discordantly interesting ones. While today

he is the soul of liberality on matters of sexual orientation (''Some of

my best friends are. . . . ''), as a smooth-faced younger man, he felt

so intimidated by his gay following that he carried a gun. (''They would

try you,'' he says. ''Lots of times, I was tried.'') The female

attention was easier to take. His most ardent fans seem to have taken

the naked vulnerability in his voice as proof of a secret knowledge of

the female heart. Scott could be heard as the jazz version of the Greek

mythological figure Tiresias, who had been both a man and a woman and

who knew everything.

When Scott is not

recording or on tour, the house that he bought three years ago upon his

return to Cleveland consumes most of his time. Visiting the trim,

three-story home in the leafy suburban town of Euclid is not unlike

entering the portal into John Malkovich's brain. The house is Jimmy

Scott. The basement, still a jungle of packing boxes, is the site of his

dream for the future, a recording studio for his various projects. The

third-floor guest room, by contrast, is a veritable cutout bin of Jimmy

Scott's recorded life, dominated by stacks of old LP's and CD's and of

the cassettes he produced himself during the stretches between

contracts. At this moment, Scott is on his hands and knees trying to

find his first comeback album, 1992's ''All the Way,'' which has

mysteriously disappeared from its jewel box. ''I know it's here, baby,''

he says. ''Just give me a little time.'' The disc fails to materialize,

but what does is the story of the comeback and how it came to be

required in the first place.

Jimmy

Scott began his career in the early 40's as a teenage singing prodigy

from the Cleveland ghetto. Soon enough, he was snapped up by Estelle

Young, a shake dancer and contortionist, who led her troupe through the

second-tier clubs and theaters of the African-American Midwest, a

training circuit of sorts for more prestigious ''chitlin' circuit''

venues like the Apollo Theater.

He

moved on to the Lionel Hampton Orchestra and then won a contract with

Savoy, but was never able to break beyond his core audience in the black

community who caught his act in the little clubs. Scott would punish

himself and those close to him for what he considered his failure.

''Every time I'd be mad,'' he says, ''instead of saying, 'I'm mad at

you,' I'd get drunk. I allowed it. It's wrong. I don't fault anyone for

it.''

Scott's anger had its reasons.

By 1962, then in his late 30's, he had broken with Savoy and was adrift

in the business. Ray Charles, always a passionate fan, signed him to his

new Tangerine label. The record that Charles produced and played piano

on, ''Falling in Love Is Wonderful,'' is by critical accord Scott's

finest, but it stayed on the shelves only a matter of weeks before

Herman Lubinsky, the owner of Savoy, claimed an exclusive contract with

Scott, and the record was pulled. ''When I put that Tangerine record

on,'' recalls the record producer Joel Dorn, then a Philadelphia D.J.,

''the phones just lit up. Everybody was asking, 'What's her name?'

''(''Falling in Love Is Wonderful'' has never been rereleased; LP's from

the original pressing are among the most sought-after, and expensive,

on the jazz collector's market.)

In

1969, Dorn, by now a successful producer at Atlantic, teamed up with

Scott to make ''The Source,'' his first album since ''Falling in Love Is

Wonderful,'' but Lubinsky moved in again, and the album never went

beyond a first pressing. (''He went out horrible with cancer,'' Scott

says of Lubinsky. ''Nobody wishes that, but the things he did to

musicians. Baby, I wasn't the only one.'') The debacle proved too much

for Scott, and in the early 70's he packed in the singing career and

returned to Cleveland. Over the next 13 years, he worked as an aide at a

nursing home and as a shipping clerk at the Cleveland Sheraton. ''When

the gig ain't there, you still got to pay the rent,'' Scott says with an

unembarrassed smile. ''I learned that a long time ago.''

Scott's

comeback began in 1984 when a friend from his East Coast days, Earlene

Rogers, called up the jazz station WBGO in Newark to ask why Scott, an

ex-local hero, was never on the radio. They told her he was dead.

Persuaded otherwise, the station invited him to appear on an afternoon

talk show, an experience that so energized Scott that he moved back to

Newark, wound up making Rogers wife No. 4 and resumed his career full

time. But he was, in the main, singing in the same joints and dives that

had demoralized him the first time around. One of his closest friends,

the eminent songwriter Doc Pomus, even published an open letter in

Billboard beseeching the industry to take note of Scott before it was

too late.

It would take Pomus's death

in 1991 to turn things around. Scott sang at the funeral, overwhelming

Seymour Stein, the legendarily tough record executive, which led to the

album ''All the Way.'' Scott remembers: ''The next day, this cat from

Warners comes over with a contract. It was like Doc's hand reaching out

from the grave.''

Scott's compact

living room is dominated by a white piano (ornamental -- he doesn't

play) and a large white teddy bear. It makes for an interesting place to

talk about the death of his mother, the original source of the

seemingly bottomless well of pain he draws on in his work. Scott was 13

when she stepped into a Cleveland street to pull her daughter Shirley

out of harm's way. Justine Scott, mother of 10, was struck by a car and

died of internal bleeding. ''That day, instinctively I knew,'' Scott

says quietly. ''It was the craziest thing. When I got home, everything

was so quiet and the kids were sniffling.'' He blames not only the fates

for taking his mother but also his aunts and his father, by all

accounts a failure as a family man, for allowing the kids to be sent to

foster homes. ''The attack came too fast,'' Scott says, as if he were

the victim of a vicious military operation.

Scott's

adolescence was marked not only by the overwhelming thing that did

happen, his mother's death, but also by the one that didn't, puberty.

When he was young, shame and secrecy were constant companions. (He is

capable of sex, incapable of reproduction.) Today he deals with the

syndrome with admirable, even surprising candor. His attitude with women

is this: ''I'm not looking for sympathy. This is me. I come to you

honestly and fairly, and if there's anything you want to know about me,

I'm here to explain it. And if we have a relationship, then we have a

relationship. If we don't, then yes ma'am, howdy.''

In

practice, Scott has fallen for a series of women who seem to have been

more taken with the voice and the fabulous career it promised than with

the man. His neediness and his desire for control, in part traceable to

his mother's early death, were aggravated. ''I don't blame them,'' the

singer says now. ''I blame myself for my anxieties, for not studying the

situation. Stupidly, I'd jump in.'' Scott pulls up a trouser leg to

reveal an ugly scar marking the spot where, he says, one of his wives

stabbed him with a kitchen knife. ''She was a husky little thing,'' he

says ruefully.

These days, Jimmy Scott

has the energy of youth without its distracting, in his case even

disastrous, passions. He is locked in on the career. ''He is mentally

prepared for this now,'' says Maxine Harvard, Scott's new manager and a

jazz industry veteran. Hardly a disinterested party, Harvard is

nonetheless blunt in her assessment of Scott's moment on the verge. ''I

have told him that if I see him self-destructing with drinks or anything

else, then I'm gone,'' she says. ''There are probably five years

there.'' For his part, Scott indicates he's ready to do what it takes.

And

perhaps his time has finally come. In the 60's, the corporate labels

were so leery of Scott's unusualness that they replaced him on the album

covers of ''The Source'' and ''Falling in Love Is Wonderful'' with a

pretty young woman and an amorous couple, respectively. In the 90's, a

decade infatuated with sexual ambiguity, Scott's aging androgyny

undoubtedly helped him secure his cult status, but also threatened to

keep him there. Mainstream America has embraced some pretty odd

characters (see Liberace), but Scott has the inconvenience of being a

real artist with fewer obvious pleasures in his arsenal. With age, the

voice has shed much of its prettiness -- the tone is thinner, the

vibrato can sound a little cracked. Listening to his reprise of ''Day by

Day,'' on ''Mood Indigo,'' anyone who recalls his near operatic

original from ''The Source'' can be filled only with a sense of loss.

But

most of the time that loss is more than compensated by the smoke-cured

timbre of his voice, by a phrasing so idiosyncratic as to become a

private language. No one sings slower or farther behind the beat than

Jimmy Scott; his long, melismatic flights freeze conventional time.

Throughout

his career, his performances have been magnets for the socially

dispossessed -- pimps, prostitutes, gays. Sometimes the scene had a

farcical aspect: ''These old pimps used to tell me, 'Well, I'm coming in

tonight, Jimmy Scott, with four women, and you better sing that

song.''' But Scott could relate all too well to an underlying loneliness

at the social margins. ''You can understand that from the songs I

sing,'' he says.

Now, perhaps, that

loneliness can be appreciated by a new generation. Weeks after my last

visit with Scott, I am watching Ethan Hawke stare rapturously at

rough-cut footage of Scott in ''Last Word on Paradise,'' the actor's

feature-film directorial debut. ''I think Little Jimmy is going to steal

this movie,'' he says.

Hawke had

signed up Scott to play a single dramatic scene in his film, shot on

digital video and underwritten by Bravo's Independent Film Channel,

about a bunch of artist-bohos (Kris Kristofferson first among them) in

the Chelsea Hotel. But on the first day, just to set a mood, he decided

to shoot Scott singing the song ''Jealous Guy,'' which he had covered on

his 1998 modern pop album, ''Holding Back the Years.'' ''As soon as it

was done,'' Hawke says, ''it was like, 'How can this be in the movie?'

But there was no way, because it was a John Lennon song and we didn't

have the budget to get the rights.'' Hawke's assistant contacted Yoko

Ono's representatives anyway, and she approved the licensing of the

song. Ono reportedly said: ''John loved Little Jimmy so much. I'm sure

that would be great.''

Thinking of

that ''Twin Peaks'' dream sequence -- Smith warbling, a midget dancing

-- I mention to Hawke that he's not the first director to be drawn to

Scott's piquant strangeness. Hawke looks injured. ''My thing is not

about Jimmy Scott being weird,'' he says definitively. ''It's about

Jimmy Scott being cool.''

A version of this article appears in print on , Section 6, Page 28 of the National edition with the headline: The Ballad of Little Jimmy Scott. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper