SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER THREE

MAX ROACH

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BEN WEBSTER

(September 7-13)

GENE AMMONS

(September 14-20)

TADD DAMERON

(September 21-27)

ROY ELDRIDGE

(September 28-October 4)

MILT JACKSON

(October 5-11)

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN

(October 12-18)

GRANT GREEN

(October 19-25)

ROY HARGROVE

(October 26-November 1)

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT

(November 2-8)

BLUE MITCHELL

(NOVEMBER 9-15) BLUE MITCHELL

BOOKER ERVIN

(November 16-22)

LUCKY THOMPSON

(November 23-29)

Booker Ervin

(1930-1970)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

A very distinctive tenor with a hard, passionate tone and an emotional style that was still tied to chordal improvisation, Booker Ervin was a true original. He was originally a trombonist, but taught himself tenor while in the Air Force (1950-1953). After studying music in Boston for two years, he made his recording debut with Ernie Fields' R&B band (1956). Ervin gained fame while playing with Charles Mingus (off and on during 1956-1962), holding his own with the volatile bassist and Eric Dolphy. He also led his own quartet, worked with Randy Weston on a few occasions in the '60s, and spent much of 1964-1966 in Europe before dying much too young from kidney disease. Ervin, who is on several notable Charles Mingus records, made dates of his own for Bethlehem, Savoy, and Candid during 1960-1961, along with later sets for Pacific Jazz and Blue Note. His nine Prestige sessions of 1963-1966 (including The Freedom Book, The Song Book, The Blues Book, and The Space Book) are among the high points of his career.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/bookerervin

Booker Ervin

Booker Ervin

Booker Ervin had a large hard tone like an

r&b tenor saxophonist, but he was actually an adventurous player

whose music fell between hard bop and the avant-garde.

Ervin

originally played trombone but taught himself the tenor when he was in

the Air Force in the early 1950s. After his discharge, he studied music

for two years before he made his recording debut with Ernie Fields in

1956. During that year he first performed with Charles Mingus and he was

a key part of Mingus’s groups during 1956-1962, offering a contrast to

the wild flights of Eric Dolphy.

During 1963-1965, Ervin led ten

albums for Prestige and each has its rewarding moments. “Exultation!”

matches Ervin with altoist Frank Strozier in an explosive quintet. “The

Freedom Book” has Ervin interacting with the unbeatable rhythm section

of pianist Jaki Byard, bassist Richard Davis, and drummer Alan Dawson.

“The Song Book,” with Tommy Flanagan in Byard’s place, features the

intense tenor interpreting a set of veteran standards. “The Blues Book,”

with trumpeter Carmell Jones and pianist Gildo Mahones, is comprised of

four very different blues and more variety than expected. The Space

Book has adventurous improvisations by Ervin, Byard, Davis, and Dawson

while Settin’ the Pace features two lengthy and exciting jam-session

numbers with fellow tenor Dexter Gordon and a pair of quartet pieces

that showcase Ervin. The tenorist is particularly passionate on the

stretched-out performances of The Trance and stars with a sextet on

Heavy. Released years later,” Groovin’ High” contains additional

material from The Freedom Book, The Blues Book, and The Space Book

sessions while Gumbo! (part of which was issued for the first time in

1999) has Ervin sharing the spotlight with altoist Pony Poindexter and

on five songs leading an organ trio with Larry Young.

Booker Ervin died much too young from kidney disease. He is one of the underrated greats of jazz history, a true individualist.

https://www.popmatters.com/booker-ervin-the-freedom-book-2496214960.html

US Release Date: 2007-05-01

UK Release Date: 2007-06-11

UK Release Date: 2007-06-11

In fact, this music shouldn't be confused with any other movement of any particular past time. It has a freshness not often found these days, and the freedom reference is mainly to the creative freedom of a tenor saxophonist as incapable of musical compromise as was Thelonious Monk. Ervin innovated in expression and substance without needing to be any kind of blatant revolutionary.

During a relatively short career ended by cancer in 1970, when he was barely forty, Ervin worked well with people doing the same serious thing he did, most famously Charles Mingus. The pianist in the perfectly organised quartet here is Jaki Byard, not only another sometime Mingus alumnus, but one of the great jazz pianists, and the most individual. The opener, "A Lunar Tune", might seem by name to belong rather to the Space Book album in this valuable series, but here we are with Byard's unique and heavy, confining chords. The startling rhythmic-harmonic structure resists possibilities of melodic development, so that when Ervin finds his improvisational line, it is -- it had to be -- intense and inspired. Though the complex chords are so much in Byard's fingers that the composition really seems his, it's in fact Ervin's. The empathy is startling throughout this session. There is a considerable sense of 'cry' in Ervin's sound, passion and melancholy and a focussedness more to be expected from a soprano saxophone, rather than a tenor. I would compare him with Dexter Gordon. Though he takes more emotional risks than that unsentimental master, he's never guilty of the least sentimentality. He might have learned from Coltrane's sound, and from Texan and midwestern tenor playing, but he is his own man.

"Cry Me Not" is a Randy Weston tune, from when the pianist's direction was more mainstream melodic (he has since gone to Africa, not least North Africa, for a new musical focus). Ervin also worked with Weston, and here the plaintive, lamenting presentation of direct melodic lines has aconsiderable emotional and spiritual depth. This is the plainer on Ervin's "A Day to Mourn", with its obvious allusion to JFK's murder in Dallas not so long before. It's almost a suite, with sections at different tempo, in different moods, and profoundly moving. Byard plays wonderfully lyrically, for once you might not know it's specifically him, but there can be no doubt that here's the extraordinary expressiveness of a major musician.

"Al's In" is named for Alan Dawson, the thoroughly admirable drummer who helped distinguish quite a number of Byard dates beside the present one. Through the melancholy opening, Dawson makes a considerable contribution, and then the pace picks up and Byard and the drummer are playing energetically and obliquely as Ervin weaves his way through choruses at once melancholy and driving, tending to produce something worthy of Fats Waller's phrase "fine Arabian stuff." The timekeeping work is in the extremely able hands of Richard Davis, very great bassist, another musician who has been at the top of his profession a long time. Davis has the power to lead the band in after a tour-de-force solo on which Dawson makes use of tuned drums. There are also solos of a high order throughout from the bassist, very notably on the slightly modified, energy-filled blues "Grant's Stand", where -- as on every track here -- everybody is on strong form.

These musicians are plainly concerned to say something all the time; they're not just superlative technicians. By 21st century standards, they don't lack anything in that respect, or in musical daring, least of all Byard. The session was supervised by the legendary Rudy Van Gelder, and this is another of the series now appearing on the Prestige label in his remastering. I've not much to say about that, since by today's standards the music has such unusual depth it's hard to listen for anything else. It retains the abiding newness of any art which says important things: a very mature player, Ervin.

The lighter note of the added "Stella" is welcome at the end, but since it might well have been recorded specially and separately for the sampler it appeared on, it does allow a complaint unusual in this century. It's not shallow, but it's too short.

https://www.jazzviews.net/booker-ervin---the-good-book-the-early-years-1960---621.html

(The Early Years 1960 - 62)

Acrobat ACQCD 7121 (4 CD set)

Every time I play I try to play as if it’s the last time I’m ever going to blow.’ If one quote can sum up a musician this one has a great deal to say about Ervin. The passion and urgency of his music is writ large on these four CDs.

Every time I play I try to play as if it’s the last time I’m ever going to blow.’ If one quote can sum up a musician this one has a great deal to say about Ervin. The passion and urgency of his music is writ large on these four CDs.

His three earliest albums - ‘The Book Cooks’, ‘Cookin'’ and ‘That's It!’ are there complete, together with appearances on recordings led by Teddy Charles, Mal Waldron and Bill Barron. In total there is material from seven albums featured.

Ervin came from Texas and the R and B circuit. He was a Texas tenor and all that implies in the jazz world. Scuffling for a time on $5 a day he came up the hard way. That was his strength and also his weakness because many critics and taste-makers pigeon-holed him and failed to see beyond his origins.

Ervin was conscious of his lack of acceptance. After ‘The Book Cooks’, he experimented with the third stream and ‘Jazz In The Garden At The Museum Art’ was originally issued under vibraphonist Teddy Charles’s name. Mal Waldron’s album The Quest on the fourth CD is almost avant-garde, the pianist features alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy.

‘Uranus’ on CD2 taken very slowly is an impressive ballad performance, with Booker’s characteristic gruff, romanticism. The same quality is heard on ‘Booker’s Blues’ as Ervin soars above George Tucker’s walking slowly bass.

Status Seeking on CD4 has Ervin with Eric Dolphy and Mal

Waldron. The bass figures are played by Ron Carter. Eric Dolphy is

unrestrained but does not out-do Ervin who is passionate, broad-brush

and more obviously appealing.

One additional reason for buying this collection is the notes by Simon Spillett. I have praised Spillett’s writing in the past but he has excelled himself here. Ervin was never given the critical plaudits that he should have received during his life and the literature about him is not easy to find. Spillett in the 51 pages here does not limit himself to the period of the recordings, he covers the life. What you have is a short book about Booker, including his early years in Texas, his time with Prestige, and when he was with Mingus. It is probably the best writing about Ervin anywhere. Spillett endeavours to answer questions about Ervin’s style and whether he can be considered an innovator. Spillett believes, and he argues it convincingly, that Ervin’s defining quality was honesty

This is a scholarly package. Playing through this CD you start to think about what is the right place for this musician in the jazz hierarchy and why such an important soloist is not widely recognised. He made a serious impact on many of the records that Mingus made at his peak but he was more than that and this selection of his early recordings looks at aspects of his work that were developed later: the passion, the velocity, the unique sound.

Reviewed by Jack Kenny

|

|

|

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fer13

ERVIN, BOOKER T., JR.

ERVIN, BOOKER T., JR. (1930–1970). Tenor saxophonist Booker T. Ervin, Jr., was born in Denison, Texas, on October 31, 1930. His father played trombone with Buddy Tate and taught Booker the instrument at an early age. After finishing high school Booker joined the United States Air Force and was stationed in Okinawa, where he learned to play the tenor sax. When his service was completed in 1953 he enrolled at the Berklee School of Music in Boston, where he learned the essentials of music theory. The following year he moved to Tulsa and joined fellow Texan Ernie Fields.Though Fields's band was primarily a rhythm-and-blues outfit, Ervin's playing became more refined, and he developed a sense of self-confidence that in 1958 led him to New York City, where he became highly regarded in local jazz circles. Shortly after his arrival he met jazz legend Charles Mingus, who was impressed with his style. Ervin joined the Mingus Jazz Workshop, and this creative association led to a string of recordings, including the 1959 masterpiece Mingus Ah-Um. Mingus was demanding and at times dictatorial, but he nurtured creativity and encouraged his musicians to improvise. Ervin soon developed a reputation as one of New York's finest young sax players. His playing could be explosive, yet his sensitive touch was powerful. Though he continued playing with Mingus through the 1960s, Ervin also recorded several solo albums for Prestige Records, including The Blues Book, The Space Book, The Freedom Book, and The Song Book. He died of kidney disease on August 31, 1970, in New York City and was buried in Long Island National Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Jane Wilkie Ervin; a son, Booker; and a daughter, Lynn.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

New York Times, September 2, 1970. Dave Oliphant, Texan Jazz (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996). Brian Priestly, Mingus: A Critical Biography (New York: Quartet Books, 1982). Gene Santoro, Myself, When I Am Real: The Life and Music of Charles Mingus (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Graded on a Curve:

Booker Ervin,

The Freedom Book

While he’s remembered foremost as a key contributor to the bands of jazz titan Charles Mingus, tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin also recorded a slew of outstanding albums as a leader, none of them better than his 1963 outing The Freedom Book. If the accumulated weight of post-bop’s golden era can sometimes feel like an unfathomable musical avalanche, this casually faultless quartet outing is unquestionably one for the hearing.

If Booker Ervin had somehow managed to appear on only one specific LP

in his career as a horn man, his historical significance would still be

solidly in the pocket. That record is Mingus Ah Um, the 1959

classic from bassist Charles Mingus, an album that’s rightfully

considered as a core document of the whole jazz experience. But Ervin

not only thrived as the go-to tenor guy for Mingus’ most creatively

fertile period, he also cemented his reputation through a wealth of

sessions as both a crucial sideman and as a leader, debuting under his

own name in 1960 with the superb The Book Cooks for the Bethlehem label and following it up with Cookin’ on Savoy later that same year.

If 1961’s That’s It found him bouncing around the label

scene as a leader (this third record was issued by Candid) he kept busy

not only with Mingus but also through appearances on vital dates by

pianist Mal Waldron (The Quest), vibist Teddy Charles (Metronome Presents Jazz in the Garden at the Museum of Modern Art), drummer Roy Haynes (Cracklin’), and fellow tenor man Bill Barron (Hot Line). His fourth LP Exultation!

hit racks in ’63 and with its release Ervin found a sturdy home through

the Prestige imprint. His next four albums were all completed through

the backing of that legendary company and they form a thematic quartet

of releases that stand for many listeners as the collected highpoint of

Ervin’s career as a bandleader.

The Freedom Book inaugurates this group of four, followed in quick succession by The Song Book, The Blues Book, and The Space Book, and for those unacquainted with Ervin’s work the series easily serves as the best place to begin. And while it’s not essential to the experience, sequential listening greatly enhances the achievement of these sleek beauties, their diverse and dynamic contents laid to tape in under a year’s span. And The Freedom Book not only provides an ample helping of Ervin’s edgy, blues-inflected tone, but it presents the debut of what’s arguably his strongest overall band.

For starters, there’s fellow Mingus alum Jaki Byard, simply one of

the most interesting pianists of the ‘60s, as anyone that’s heard the

Mingus Sextet’s 2CD Cornell 1964 or any of his own prime works

for Prestige will attest. As a living breathing textbook of jazz styles,

in some ways Byard is similar to multi-instrumentalist Roland Kirk

(with whom he frequently played), though he’s far less of a showman and

more a stately maverick of uncommon subtlety and versatility. On his own

he could run the gamut from ragtime to free, but when working in

support he always adjusted his talents to the vision of the leader

without sacrificing his own personality; he could connect with the

unconventional ideas of an composer like Don Ellis, lend context to a

harbinger of the New Thing ala Sam Rivers, and flesh out the strategies

of a Texas tenor like Ervin.

Bassist Richard Davis has anchored so many top flight records that

his status is ultimately immeasurable. Not only a contributor to

undisputed masterworks by Eric Dolphy (Out to Lunch) and Andrew Hill (Point of Departure), he was also Stravinsky’s bassist of choice and played a defining role in the achy splendor of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks.

Equally comfortable behind a trad vocalist like Sarah Vaughan, an

R&B inflected tenor like Jimmy Forrest, or a more cerebral musician

like vibist Bobby Hutcherson, Davis is what’s called an all around

mensch.

If drummer Alan Dawson is a rather unheralded name, it should be

noted that like Byard and Davis he was also an teacher; he just jumped

into academe much sooner than his counterparts, signing up at Boston’s

Berklee School of Music in the late ‘50s, far ahead of the jazz

educational curve. And because of this, Dawson’s status for many is

relegated to being the tutor of the great Tony Williams. But that’s a

rather disrespectful miscalculation, for he played on a bunch of high

quality records; the majority of them just didn’t catch the world on

fire. In addition to Ervin, he backed some of Byard’s best sessions,

assisted dates from august names like Sonny Criss, Dexter Gordon, and

Sonny Stitt, and sounds particularly strong on one of Illinois Jacquet’s

best late albums Bottoms Up.

The result of putting these four in a room is unsurprisingly

exquisite. Opener “A Lunar Tune” has Ervin presenting a teetering,

somewhat knotty opening theme before falling in with the rest of the

band and laying down an extended, fiery solo. There are detectable

similarities to John Coltrane in his tone, though Ervin is a bluesier

player, if no less inclined to experiment. Like Jackie McLean, he’s been

described as an inside-outside guy, and his flirtations with the

textures of the emerging avant-garde always feel natural and individual;

“A Lunar Tune” makes clear that The Freedom Book is a study in

advanced bop, a serious album interested in extending the possibilities

of the form instead of just elevating it’s norms. After Ervin drops

out, Byard solos with typical grace before Davis and Dawson get down to

some fine rhythm business. In fact, Dawson shines throughout the track,

using his full kit without ever feeling busy or overextended. Then Ervin

comes back in with the head to wrap things up.

As is expected with post-bop studio outings, “A Lunar Tune” gives way

to a change in tempo, the group working through Randy Weston’s ballad

“Cry Me Not” (notably, the four other tracks are all Ervin originals).

Here the saxophonist explores the gentleness required of the composition

without slipping into sentimentality or cliché, his tone ranging from

bold to introspective, and indeed all the players are actively involved

in shaping the song’s success, never falling into the role of

inexpressive support.

“Grant’s Stand” is what’s called a blowing tune, the sort of

deceptively nonchalant excursion that can raise the heat and bring down

the house, and in this Ervin nods to the stomping tradition of his Texas

roots. And again, The Freedom Book doesn’t really divert from

post-bop formula as much as it just pushes it forward with unvarnished

mastery; here as on “A Lunar Tune” Ervin opens with an extended and

ripping though never flustered solo and then lays out for Byard, who

opens a little like Monk and then shifts into something a bit

reminiscent of McCoy Tyner minus the block chords before hinting at some

angularity that’s mildly associative of early Cecil Taylor or the yet

to make the scene Don Pullen. To sum up Byard in two words; incalculably

valuable. From there Davis’ brief spot soars with creativity, never

falling into the giant rubber band tropes that often plague the bass

solo. After some nice give and take between Ervin and Dawson, the tune

concludes having packed a wealth of ideas into just eight minutes.

“A Day to Mourn” was written as a tribute to John F. Kennedy and

recorded less than two weeks after his assassination. It’s a spacious,

meditative dedication and a fitting one in how it avoids any sense of

predictability; the tempo thoughtfully shifts, Davis’ pizzicato bass

work and the diversity of Dawson’s percussion register less as solos or

strategies than as highly effective shadings of mood, and Byard moves

from contemplative to jaunting with nary a hiccup. But it’s in the sound

of Ervin’s horn that the composition really succeeds in hitting home a

half century after it was recorded. Innovation can be a fleeting thing,

but inspiration and sincerity cut through the fog of time.

Closer “Al’s In” begins at a simmer and then shifts impeccably into a

full boil, Ervin saving his most dynamic blowing for last as the rhythm

section, particularly the thorny and assertive Byard and the wickedly

committed Dawson go to work with vigor. The latter’s solo spotlight, one

of the album’s brightest moments, is a clinic in non-hackneyed drum

motion, the range of his expression capping the album, though the brief

reemergence of the full quartet before a slow fade out leaves the ear

nagging for more.

Of which there was, of course. The subsequent entries in the Book

series found Ervin shuffling and adding some members, subbing pianists

Tommy Flanagan and Gildo Mahones for Byard and adding underrated

trumpeter Carmell Jones before returning to this splendid lineup for the

final installment. And while the whole set is indispensible, The Freedom Book

sits a little above the rest. Thankfully there is no mandate limiting

ownership of Booker Ervin releases to just one LP, for he never recorded

a bad one. But if that foul edict ever came down, this sweet pup would

very likely be the one to choose.

Graded on a Curve: A+

No Need To Cook The Books: Booker Ervin's Debut LP Reissued

Monday, May 25, 2015

Booker Ervin: 1930-1970

© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Originally a trombone player, Ervin taught himself saxophone while in the services and instinctively veered towards the kind of blunt, blues-soaked sound of fellow-Texans like Arnett Cobb and Illinois Jacquet. He had his big break with Mingus, who liked his raw, unaffected approach. The career was painfully short, but Booker packed a lot in. He's still missed.”

- Richard Cook and Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, 6th Ed.

“Booker Erwin is a powerful, swinging, story-teller.”

- Ira Gitler, insert notes to Booker Ervin/Groovin' High [OJCCD-919-2/P-7417]

During a recent listening of tenor saxophonists Booker Ervin and Zoot Sims on Booker’s The Book Cooks [Bethlehem Avenue Jazz R2 76691], I was really taken by the difference in sound that each got on the same instrument.

While Zoot’s tone was its usual bright, buoyant and bouncy self, Booker’s was darker, denser and more driving; one floated over the rhythm while the other pushed through it.

Hailing from Denison, Texas it’s easy to associate Booker’s style with the big bluesy, and wailing style that has become known as the Tenor Tenor Sound, a sound that the late Julian Cannonball Adderley once described as “the tone within the moan.”

Or as Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler describe it in The Encyclopedia of Jazz: “With a sound as big as the great outdoors, and a tidal rhythmic drive, he was in the lineage of the Texas Tenors.”

While Booker’s approach to Jazz improvisation was certainly rooted in The Blues, it seemed more expansive and more expressive. But what were the qualities that made it so?

I thought it might be fun to share some observations by other Jazz writers and critics whose ideas about Booker’s approach to Jazz helped shed light on my quest to know more about how he achieved his singularity.

Sadly, Booker didn’t have long to share his secrets as he died in 1970 at the age of 40!

Let’s begin with this overview of his career by Mark Gardner which is drawn from The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz:

“Booker Ervin (b Denison, TX, 31 Oct 1930; d New York, 31 Aug 1970) was the son of a trombonist who worked for a time with Buddy Tate, and he inherited his father's instrument: between the ages of eight and 13 he played trombone. He taught himself to play saxophone while in the air force (1950—53), then studied music in Boston for two years. His first professional engagement was with Ernie Fields's rhythm-and-blues band, with which he made his earliest recordings (c!956). Ervin rose to prominence as a member of Charles Mingus's group (1958-62). He also worked frequently in a cooperative quartet, the Playhouse Four, with Horace Parlan, George Tucker, and Al Harewood, and with Randy Weston. His best work as a leader was on nine albums recorded for Prestige (1963—6).

Ervin was a powerful player whose hard tone and fondness for the blues marked him as a member of the Texas school in the tradition of Buddy Tate, Arnett Cobb, and Illinois Jacquet.

He never allowed his formidable technique to obscure the emotional intensity of his playing, and he was one of the very few tenor saxophonists of his generation to remain untouched by the influence of John Coltrane and develop a wholly personal style.”

[There seems to be some debate about Coltrane’s influence on Booker, for example, Ira Gitler maintains that “Although Booker named Coltrane as his favorite, he was less indebted to him than were the majority of his contemporaries.”The Encyclopedia of Jazz.]

Continuing on with Ira’s assessment of Booker’s talents, the following is drawn from one of the many “Book” LP’s that Erwin made for the Prestige label from around 1963 66.

“If jazz had a bible it surely would be known as The Book of the Blues, for without the blues, jazz would be a salt-water fish in fresh water. This album is not the The Book of the Blues but it is The Blues Book [Prestige OJCCD-780-2/P-7430], or how Booker Ervin feels about the blues. "There's all kinds of blues," said Booker, "and I just wanted to play some of the different kinds."

That is stated simply enough (the blues for all their variety are basically simple, too) but when Ervin becomes involved in his highly emotional blowing, all is not that simple. It is not a matter of having to break your brains to comprehend his story — Booker plays from the heart of jazz directly to your heart — but the depth, breadth, and width of his approach arm it with ramifications that are anything but plain.

The pressure exerted in a hard, extended kiss doesn't always indicate the lack of equal intensity behind it, but if that surface force is really representative of the underlying feeling then you are dealing with something powerful. The loudness or hardness of a musician's delivery doesn't necessarily stand for true depth or sincerity, but if it does, look out, for you are in for a steam-cleaning from the convolutions of your cranium down to your entrails.

Booker Ervin's tenor is like a giant steamroller of a brush, painting huge patterns on a canvas as wide and high as the sky. There is nothing small about his sound, his soul, or his talent. … His passionate music is of the '60s but it has not lost touch with the tap-roots of jazz.

Booker's phrasing (the highly-charged flurries and the excruciating, long-toned cries), harmonic conception (neither pallid nor beyond the pale), and tone (a vox humana) add up to a style that is avant garde yet evolutionary, and not one that bows to fashion or gropes unprofessionally under the guise of "freedom".

Dan Morgenstern, the esteemed author and now-retired Director of The Institute for Jazz Studies, offered this perspective on Booker’s playing in his insert notes to Booker Ervin: The Song Book [[OJCCD- 779-2/P-7318]:

“As I am writing these notes for Booker Ervin's third Prestige album, the yearly chore of filling out my Down Beat Critic's Poll ballot is very much on my mind. It is a chore because there are so many excellent musicians to choose from, and one is often forced to make rather arbitrary exclusions. But there are always a few instances in which there can be no doubt or equivocation. This year, Booker Ervin's name is one of those I'll put down without the slightest hesitation.

‘There's nothing on earth I like better than playing music,’ Booker Ervin once told me. His playing sounds like that. It is full of fire and conviction: nothing about it strikes the ear as forced, contrived or meretricious. It is no wonder that Charlie Mingus—a man who likes his music naked—has used Booker whenever he could get him.

Booker is his own man now, though. Not that that means he can't play with others ... his work with Randy Weston and Mingus in recent months proves well that he can. It does mean, however, that Booker has his own stories to tell and that he knows how to get them together without being coached. The best proof of that is his playing on his two previous Prestige albums …..

And even better proof is the album at hand. Not that it is necessarily a better album all around; each of them has its points. It's that it is an album of great pieces from the jazz repertoire, and that such a collection represents a challenge to a player: the challenge of saying something definitively on themes that have already had definitive readings; the challenge of proving that you have your own voice not only when playing your own things on your own turf but also when playing on regulation fields with traditional rules. That's major league stuff, and Booker has what it takes.”

Perhaps Ed Williams summed it up best when he wrote this about Booker in his insert notes to Ervin’s 1968 Blue Note LP - The In Between [CDP 7243 8 59379 2]:

“BIG, FULL, OPEN, "LOUD." There are other ways of describing Booker Ervin's sound. Those just happen to be a few that I think are particularly apropos. "LOUD" as I mean it, connotes a basically honest projection of his emotions, without any special regard for modulation. That, coupled with his appreciation for the "big," "full" sound his instrument is capable of producing makes him seem "loud." The important thing is the fact that it's Booker, and his way of doing it. Self-expression is indeed a precious possession.”

The following video features Booker performing his original composition "Dee Da Do" with Richard Williams, trumpet, Horace Parlan, piano, George Tucker, bass and Danny Richmond, drums.

Booker Ervin

Randy Weston has no end of praise for Booker Ervin. Weston’s tonal portrait of his mother, “Portrait of Vivian,” was introduced on his 1963 recording, African Cookbook. He says that “only Booker Ervin could play the song.” And in his autobiography, African Rhythms, he says that Ervin’s solo on “Vivian” at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1966 was “one of the greatest… I would put that solo alongside any other tenor solo. Booker literally cries on the tenor saxophone.”

Ervin worked with Weston between 1963 and ’66. The group Weston led at Monterey included Ray Copeland on trumpet, Cecil Payne on baritone sax, Vishnu Wood on bass, Lennie McBrowne on drums, and Big Black on congas. On his website, Weston points to this outfit with pride and calls it “an incredible band because number one, we had Booker Ervin, [who] for me was on the same level as John Coltrane. He was a completely original saxophonist. I don’t know anybody who played like Booker. But Booker, he was very sensitive, very quiet, not the sort of guy to push himself or talk about himself…He was a master saxophonist, and the song I wrote for my mother, ‘Portrait of Vivian,’ only he could play it; nobody else could play that song.

“In fact, African Cookbook, which I composed back in the early 60’s, was partly named after Booker because we (musicians) used to call him “Book…” Sometimes when he was playing we’d shout, “Cook, Book.” And the melody of African Cookbook was based upon Booker Ervin’s sound, a sound like the north of Africa. He would kind of take those notes and make them weave hypnotically. So, actually African Cookbook was influenced by Booker Ervin.”

Ervin’s career on the New York scene lasted only a decade before his death from kidney disease in 1969 at age 39. Notwithstanding his major contributions to the music of both Weston and Charles Mingus, he drew little attention during his lifetime, and he’s become a largely forgotten figure since. This is regrettable, for Ervin’s recordings maintain the raw power and emotional force for which they were known in their time.

We’ll hear the first of the series of “Books” that Ervin recorded for Prestige in tonight’s Jazz à la Mode. The Song Book features pianist Tommy Flanagan and includes one of the first recordings of “Come Sunday” that was made outside the realm of Ellingtonia.

Here’s a rare glimpse of Booker Ervin in action on Miles Davis’s seminal original, “Milestones.”

Ted Curson, trumpet Pony Poindexter, alto Booker Ervin, tenor Nathan Davis, flute Kenny Drew, piano Edgar Bateman, drums

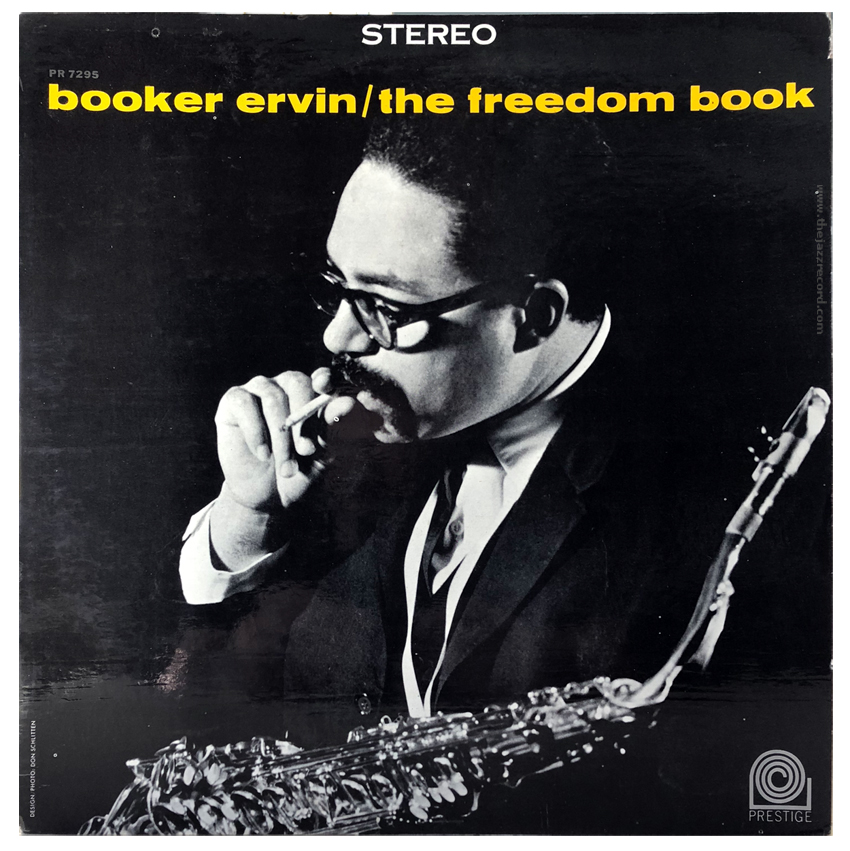

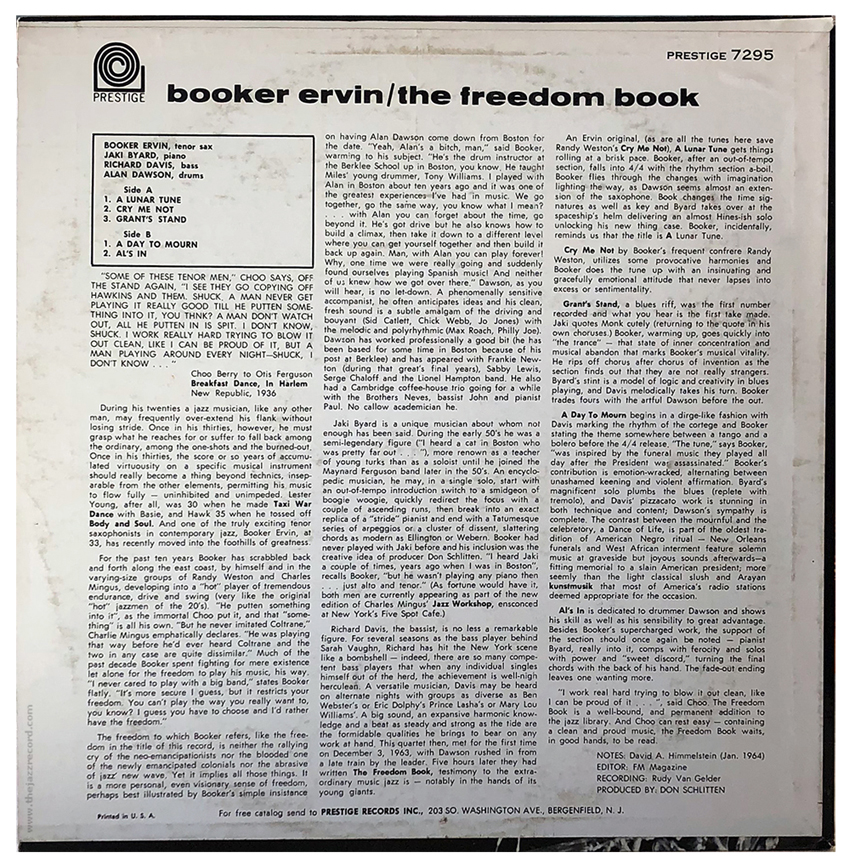

http://www.thejazzrecord.com/records/2019/1/7/booker-ervin-the-freedom-bookLeading His Own Way: Booker Ervin - "The Freedom Book"

The Tracks:

A1. A Lunar Tune

A2. Cry Me Not

A3. Grant’s Stand

B1. A Day To Mourn

B2. Al’s In

A2. Cry Me Not

A3. Grant’s Stand

B1. A Day To Mourn

B2. Al’s In

The Players:

Booker Ervin - Tenor Sax

Jaki Byard - Piano

Richard Davis - Bass

Al Dawson - Drums

Jaki Byard - Piano

Richard Davis - Bass

Al Dawson - Drums

The Selection:

The Vinyl:

When I originally picked up this beautiful second pressing of “The Freedom Book” I almost immediately set it back down in the rack, simply because these “blue trident” Prestige labels always seem like such a let down from the possibility that you could have found an ever-so-classic yellow and black “fireworks” label pressing. And, of course, there is that stupid modern day stigma of it not being a first pressing, even though I always try not to let that color my decision making when I come across a classic vintage jazz title to add to the collection.

A quick check on the smartphone showed that “The Freedom Book” dated from 1964, meaning it was entirely possible that the “blue trident” label could indicate a first pressing, and while that is not the case here, it turns out that 1964 was the year that Prestige switched label designs (couldn’t they have come up with something a little more creative looking?!?) and this album appears to have had a short run on the yellow “fireworks” label and was then quickly re-pressed on the label version seen here.

It turns out that while neither the first or second pressings from 1964 are easy to come by, they are also not all that sought after either: the original “fireworks” pressing recently fetched $200 on eBay, while the second blue label version could be had in VG+ for under $100. No one seems interested in the original black and silver “stereo fireworks” pressing, and if you aren’t a label snob it was repressed on the lime green label in the early-1970s (which have always sounded just fine on my turntable and are always a great way to grab a classic Prestige title at a bargain price). I scored my VG+ copy for $40 (after bargaining down from the original sticker price of $80), so I’m more than pleased with my purchase from a marketplace point of view. As far as the blue trident label, loyal readers know I’m far from a first-pressing snob, but these generic looking labels always get me down - I guess I’ll just have to come to terms with my design bias and learn to turn the other cheek and just enjoy the music!

The Music:

These days Booker Ervin is usually remembered for his association with Charles Mingus, a fruitful period that resulted in some amazing albums, most notably the all-time classic Mingus Ah Um (but also the great Mingus, Mingus, Mingus, Mingus, Mingus which I wrote about here). Ervin, however, also had a great run of solo records on Prestige from 1963 through 1966, the best of which are his “Book” series which began with the release of The Freedom Book in 1964 (and continued with The Song Book, The Blues Book and The Space Book).

In the liner notes, Ervin gives some insight into the title:

“I never cared to play with a big band,” states Booker flatly, “It’s more secure I guess, but it restricts your freedom. You can’t play the way you really want to, you know? I guess you have to choose and I’d rather have the freedom.”

And freedom suits Ervin perfectly. He has a muscular and hard-edged tone that is distinctly his, and he puts it to great use on this record. The quartet assembled here isn’t a working group - Ervin put the group together specifically to record the album - but their rapport is excellent. He had played with Jaki Byard during his time with Mingus (Byard is one of the true underrated talents of jazz), but he hadn’t played with drummer Alan Dawson in nearly a decade and Richard Davis on bass was a relative newcomer to the jazz scene at this point. The four musicians got together for the first time on the very same day that they recorded The Freedom Book, a risky undertaking to be sure, but as the resulting music shows, these cats meshed perfectly. It’s a testament to not only their talents, but also to the skills of Ervin as a leader.

The music the group lays down is definitely not “chilling-out-on-a-sunday-morning” jazz, but rather a set of challenging tunes that demands the listener’s attention. Ervin is definitely doing his own thing here, not concerned with which way the winds of popular jazz were blowing in the early 1960s, perhaps a trait he learned from his time playing with Mingus, a jazz cat at the top of the heap when it comes to following one’s own musical vision. The Freedom Book takes a hard bop base, adds a little post bop to the mix, and finishes things off with just a touch of the avant garde to create a record that has more than stood the test of time, and is certainly an album worthy of many repeated enjoyable spins on the turntable.

The Videos:

A couple of super cool video clips for your viewing pleasure, the first one here features the Charles Mingus Sextet performing “I’ll Remember April” at the Antibes jazz festival in 1960, with an all-star group featuring Bud Powell on piano, Booker Ervin on tenor, Eric Dolphy on alto, Ted Curson on trumpet and Dannie Richmond on drums. A truly historical clip with some of the best jazz players of their day.

The second video is an undated clip featuring Ervin and Curson joined by Pony Poindexter on alto, Nathan Davis on flute, Kenny Drew on piano and Edgar Bateman on drums running through a smoking hot take of Miles Davis’ “Milestones” in what appears to be a small jazz club judging on how tightly the players are packed on the stage. It sure doesn’t seem to bother the musicians any, though, as they show off their chops on this modal classic.

Music Reviews

No Need To Cook The Books: Booker Ervin's Debut LP Reissued

November 11, 2013

Heard on Fresh Air

Tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin came to New York in 1958. Pianist Horace Parlan heard him and invited Ervin to sit in one night with a band he worked in. That's how Ervin got hired by bassist Charles Mingus, who featured him on albums like Blues and Roots and Mingus Ah Um. Before long, Ervin was making his own records, like The Book Cooks, which has just been reissued on the re-revived Bethlehem label.

Ervin came from Northeast Texas on the Oklahoma line, field hollers coming at him from the east and cattle calls from the west. He punctuated his lines with high lonesome hollers before he got to New York and discovered that John Coltrane had a similar move. Ervin got ideas from Coltrane after that, but that cry was always his own. Coltrane's tone was as glossy as varnished hardwood. Booker Ervin's sound was more coarse, like a cane stalk shooting up out of rich earth.

For the ensemble shouts and background riffs, Booker Ervin is flanked by trumpeter Tommy Turrentine from Max Roach's band, as well as a Lester Young disciple and big-band vet, tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims. Sims could blow cool — he'd once recorded with Jack Kerouac — but also liked locking horns with fellow tenors. The saxophonists square off in a friendly way on The Book Cooks. Sims' tone is a little softer and rounder than Booker's.

The late '50s and thereabouts served as a great period for jazz rhythm sections — mighty bass players in particular. Nowadays, most bassists set the strings low to the neck so their fingers don't have to fight so hard. Back then, strings were higher and players couldn't get around so quickly. But they could pluck a string so hard, it made bass a percussion instrument. In "The Blue Book," for example, the great George Tucker's bass beat and Dannie Richmond's hi-hat and cymbals mail his message home.

The Book Cooks was Booker Ervin's first album under his own name, and it kicked off an early-'60s hot streak. He'd make the classics The Freedom Book and The Space Book with another great rhythm section, and recorded other good dates involving Tommy Flanagan, George Tucker or Dannie Richmond. But what really makes all those records is Booker Ervin's Texas shout on tenor saxophone, a sound that's both down-home and majestic.

THE

MUSIC OF BOOKER ERVIN: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF

RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS

WITH BOOKER ERVIN:

BOOKER ERVIN

Booker Ervin – The Blues Book

Booker Ervin - That's It! (Full Album)

Booker Ervin (Usa, 1965) - The Space Book (Full)

Booker Ervin - The Freedom Book [1963]

Booker Ervin - Lament For Booker Ervin (Full Album)

Don Patterson With Booker Ervin – Hip Cake Walk

Roy Haynes With Booker Ervin - Cracklin' (Full Album)

Booker Ervin With Dexter Gordon – Setting The Pace (FULL ALBUM)

BOOKER ERVIN the in between (1968)

Booker Ervin 1966 - Deep Night

Booker Ervin

Booker Telleferro Ervin II (October 31, 1930 – August 31, 1970[1]) was an American tenor saxophone player. His tenor playing was characterised by a strong, tough sound and blues/gospel phrasing. He is best known for his association with bassist Charles Mingus.

Ervin was born in Denison, Texas. He first learned to play trombone at a young age from his father, who played the instrument with Buddy Tate.[2] After leaving school, Ervin joined the United States Air Force, stationed in Okinawa, during which time he taught himself tenor saxophone.[2] After completing his service in 1953, he studied at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Moving to Tulsa in 1954, he played with the band of Ernie Fields.[2]

After stays in Denver and Pittsburgh, Ervin moved to New York City in spring 1958, initially working a day job and playing jam sessions at night. Ervin then worked with Charles Mingus regularly from late 1958 to 1960, rejoining various outfits led by the bassist at various times up to autumn 1964, when he departed for Europe. During the mid- 1960s, Ervin led his own quartet, recording for Prestige Records with, among others, ex-Mingus associate pianist Jaki Byard, along with bassist Richard Davis and Alan Dawson on drums.

Ervin later recorded for Blue Note Records and played with pianist Randy Weston, with whom he recorded between 1963 and 1966. Weston has said: "Booker Ervin, for me, was on the same level as John Coltrane. He was a completely original saxophonist.... He was a master.... 'African Cookbook', which I composed back in the early '60s, was partly named after Booker because we (musicians) used to call him 'Book,' and we would say, 'Cook, Book.' Sometimes when he was playing we'd shout, 'Cook, Book, cook.' And the melody of 'African Cookbook' was based upon Booker Ervin's sound, a sound like the north of Africa. He would kind of take those notes and make them weave hypnotically. So, actually the African Cookbook was influenced by Booker Ervin."[3]

Between October 1964 to summer 1966 Ervin worked and lived in Europe, playing gigs in France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Holland. Basing himself in Barcelona, he featured regularly at the city's Jamboree Club. He recorded and broadcast while overseas, making albums with his own quartet, Dexter Gordon and Catalonian vocalist Nuria Feliu, featuring on various radio programmes and appearing at several jazz festivals, including a notorious guest slot at the 1965 Berlin Jazz Festival, during which a twenty-five-minute improvisation left the audience divided, some thinking it Ervin's answer to Coltrane and Rollins (who was also on the gig), others believing it to be a self-indulgent rant. In 1977, this performance was issued as Blues For You on the album 'Lament For Booker Ervin' (Enja Records). To this day, it continues to divide listeners.

After returning to the US in summer 1966, Ervin again led his own outfits in various jazz clubs across the country, and appeared at both the Newport Jazz Festival (1967) and the Monterey Jazz Festival (1966). In 1968, he again appeared at clubs and festivals in Scandinavia, broadcasting with the Danish Radio Big Band. He recorded again for Prestige, but in late 1966 was signed to leading West Coast label, Pacific Jazz, for whom he taped two albums, Structurally Sound and Booker 'n' Brass (1967), before switching to Blue Note, a label that like Pacific Jazz was purchased by United Artists in the late 1960s. Ervin recorded two Blue Note albums under his own name, In Between and Tex Book Tenor, the latter going unissued during his lifetime, initially being released in the 1970s as part of a double album shared with recordings (on which Ervin features) made under the leadership of Horace Parlan (Back from the Gig). In 2005, Blue Note issued as single CD of Tex Book Tenor in its limited edition Connoisseur series. His final recorded appearance occurred in January 1969, when he guested on a further Prestige album headed by blind teenage multi-instrumentalist Eric Kloss. No further recordings beyond this point have yet come to light.

Ervin died of kidney disease in New York City in 1970, aged 39.[4]

Most biographical accounts of Ervin's death give an incorrect date. His gravestone in The National Cemetery, East Farmingdale, New York, clearly shows the date as August 31, 1970.

In 2017, Ervin was the subject of a mini-biography written by English saxophonist and author Simon Spillett, released as part of an anthology package titled 'The Good Book' (Acrobat Records)

Discography

As leader

- 1960: The Book Cooks (Bethlehem)

- 1960: Cookin' (Savoy)

- 1961: That's It! (Candid)

- 1963: Exultation! (Prestige)

- 1963: Gumbo! (Prestige) with Pony Poindexter

- 1963: The Freedom Book (Prestige)

- 1964: The Song Book (Prestige)

- 1964: The Blues Book (Prestige)

- 1964: The Space Book (Prestige)

- 1965: Groovin' High (Prestige)

- 1965: The Trance (Prestige)

- 1965: Setting the Pace (Prestige) - with Dexter Gordon

- 1966: Heavy!!! (Prestige)

- 1966: Structurally Sound (Pacific Jazz)

- 1967: Booker 'n' Brass (Pacific Jazz)

- 1968: The In Between (Blue Note)

- 1968: Tex Book Tenor (Blue Note)

- Back from the Gig (1964–68 [1976]) – compiling previously unreleased sessions which were later issued as Horace Parlan's Happy Frame of Mind in 1988 and Ervin's Tex Book Tenor in 2005.

- With Bill Barron

- Hot Line (Savoy, 1962 [1964])

- Out Front! (Prestige, 1964)

- Jazz In The Garden At The Museum Of Modern Art (Warwick, 1960)

- Urge (Fontana, 1966)

- Núria Feliu with Booker Ervin (Edigsa, 1965)

- Cracklin' (New Jazz, 1963)

- Grass Roots (Blue Note, 1968)

- In the Land of the Giants (Prestige, 1969)

- Havin' a Ball at the Village Gate (RCA, 1963)

- Jazz Portraits: Mingus in Wonderland (United Artists, 1959)

- Mingus Ah Um (Columbia, 1959)

- Mingus Dynasty (Columbia, 1959)

- Blues & Roots (Atlantic, 1959)

- Mingus (Candid, 1960

- Mingus at Antibes (Atlantic, 1960 [1976])

- Reincarnation of a Lovebird (Candid, 1960)

- Oh Yeah (Atlantic, 1961)

- Tonight at Noon (Atlantic, 1957-61 [1965])

- Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (Impulse!, 1963)

- Up & Down (Blue Note, 1961)

- Happy Frame of Mind (Blue Note, 1963 [1988])

- The Exciting New Organ of Don Patterson (Prestige, 1964)

- Hip Cake Walk (Prestige, 1964)

- Patterson's People (Prestige, 1964)

- Tune Up! (Prestige, 1964 [1971])

- Soul People (Prestige, 1965)

- The Quest (New Jazz, 1961)

- Highlife (Colpix, 1963)

- Randy (Bakton, 1964) - also released as African Cookbook (Atlantic) in 1972

- Monterey '66 (Verve, 1966)