ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2019/11/booker-ervin-1930-1970-legendary-iconic.html

PHOTO: BOOKER ERVIN (1930-1970)

Booker Ervin

(1930-1970)

Biography by Scott Yanow

A very distinctive tenor with a hard, passionate tone and an emotional style that was still tied to chordal improvisation, Booker Ervin was a true original. He was originally a trombonist, but taught himself tenor while in the Air Force (1950-1953). After studying music in Boston for two years, he made his recording debut with Ernie Fields' R&B band (1956). Ervin gained fame while playing with Charles Mingus (off and on during 1956-1962), holding his own with the volatile bassist and Eric Dolphy. He also led his own quartet, worked with Randy Weston on a few occasions in the '60s, and spent much of 1964-1966 in Europe before dying much too young from kidney disease. Ervin, who is on several notable Charles Mingus records, made dates of his own for Bethlehem, Savoy, and Candid during 1960-1961, along with later sets for Pacific Jazz and Blue Note. His nine Prestige sessions of 1963-1966 (including The Freedom Book, The Song Book, The Blues Book, and The Space Book) are among the high points of his career.

Booker Ervin

Booker Ervin had a large hard tone like an r&b tenor saxophonist, but he was actually an adventurous player whose music fell between hard bop and the avant-garde. Ervin originally played trombone but taught himself the tenor when he was in the Air Force in the early 1950s. After his discharge, he studied music for two years before he made his recording debut with Ernie Fields in 1956. During that year he first performed with Charles Mingus and he was a key part of Mingus’s groups during 1956-1962, offering a contrast to the wild flights of Eric Dolphy. During 1963-1965, Ervin led ten albums for Prestige and each has its rewarding moments. "Exultation!" matches Ervin with altoist Frank Strozier in an explosive quintet. "The Freedom Book" has Ervin interacting with the unbeatable rhythm section of pianist Jaki Byard, bassist Richard Davis, and drummer Alan Dawson. "The Song Book," with Tommy Flanagan in Byard’s place, features the intense tenor interpreting a set of veteran standards. "The Blues Book," with trumpeter Carmell Jones and pianist Gildo Mahones, is comprised of four very different blues and more variety than expected. The Space Book has adventurous improvisations by Ervin, Byard, Davis, and Dawson while Settin’ the Pace features two lengthy and exciting jam-session numbers with fellow tenor Dexter Gordon and a pair of quartet pieces that showcase Ervin. The tenorist is particularly passionate on the stretched-out performances of The Trance and stars with a sextet on Heavy. Released years later," Groovin’ High" contains additional material from The Freedom Book, The Blues Book, and The Space Book sessions while Gumbo! (part of which was issued for the first time in 1999) has Ervin sharing the spotlight with altoist Pony Poindexter and on five songs leading an organ trio with Larry Young. Booker Ervin died much too young from kidney disease. He is one of the underrated greats of jazz history, a true individualist.

https://www.villagepreservation.org/2023/06/23/booker-t-ervin-the-jazz-musicians-favorite/

Booker T. Ervin: The Jazz Musician’s Favorite

by Shannen Smiley

June 23, 2023

Village Preservation

We’ve recently unearthed information about another great African American jazz musician who called our neighborhood south of Union Square home, and have added him to our South of Union Square map’s music and African American history tours. Born in Dennison, Texas, on October 31, 1930, Booker T. Ervin was a tenor saxophonist who resided at 204 East 13th Street. The son of a saxophonist, Booker began his musical journey at a very young age. Upon completing high school, Ervin enlisted in the United States Air Force. While stationed in Okinawa, he learned to play tenor sax, enrolling in the Berklee School of Music following his service in 1953. Following his time at Berklee, Ervin traveled to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he played the tenor saxophone alongside another Jazz great, Ernie Fields.

Moving to New York City in May of 1958, Ervin would quickly befriend Charles Mingus and join the well-respected Mingus Jazz Workshop. From then on, Ervin would perform alongside Mingus and Randy Weston, who once also resided at 204 East 13th Street. In 1959, Ervin contributed to the monumental Mingus Ah Um album. In addition to playing alongside Mingus, he recorded various albums throughout the 1960s. Signed to Prestige Records in 1963, these albums included: The Blues Book, The Space Book, The Freedom Book, and The Song Book.

References to ‘the Book’ were described by Ervin’s close friend Randy Weston for his album, “African Cookbook,” in 1969: “the African Cookbook, which I composed back in the early 60’s, was partly named after Booker because we (musicians) used to call him “Book,” and we would say, “Cook, Book.” Sometimes when he was playing we’d shout, “Cook, Book, cook.” And the melody of African Cookbook was based upon Booker Ervin’s sound, a sound like the north of Africa.” (1993)

Despite the breadth of his compositions, Ervin remained underappreciated in jazz. As a result, he packed up with his wife Jane and two children for Europe. Heading overseas in October of 1964, Ervin would initially perform at Copenhagen’s Montmartre Club, followed by acts at the Blue Note Club in Paris, amongst others. Some additional countries that Ervin performed in included France, Holland, Sweden, Italy, and Germany. However, the country that held Ervin’s attention the longest was Spain. Locked in at a Jamboree Club gig, Ervin found stability in this Catalonian venue – extending his stay in Europe to 1966.

Upon his return, Ervin moved into 204 East 13th Street. Ervin would record his song, “204,” to honor his time in this building. The family would remain in the building throughout the remaining years of his life before Ervin passed away from kidney failure at the age of 39 on August 31, 1970. Having supported and worked closely with some of the Jazz industry giants, Ervin also holds a high honor among fellow musicians of the past and present – demonstrating his true talent as a great among the greats.

You’ll learn more about Booker Ervin’s amazing life and story on South of Union Square map’s music and African American history tours. You’ll also learn more about great musicians like Roy Orbison, Benny Goodman, Art Blakey, Tim Buckley, Frank Zappa, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa, Patti Smith, Junior Vasquez, the Clash, The Rolling Stones, Frank Sinatra, and Charles Mingus, and critical figures in African American history like W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes, Billie Holiday, Robert Earl Jones, Audre Lorde, Malcolm X, and Paul Robeson.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Booker_Ervin

Booker Ervin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Booker Telleferro Ervin II (October 31, 1930 – August 31, 1970)[1] was an American tenor saxophone player. His tenor playing was characterised by a strong, tough sound and blues/gospel phrasing. He is remembered for his association with bassist Charles Mingus.

Biography

Ervin was born in Denison, Texas, United States.[2] He first learned to play trombone at a young age from his father,[2] who played the instrument with Buddy Tate.[3] After leaving school, Ervin joined the United States Air Force, stationed in Okinawa, Japan, during which time he taught himself tenor saxophone.[3] After completing his service in 1953, he studied at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.[2] Moving to Tulsa in 1954, he played with the band of Ernie Fields.[3]

After stays in Denver and Pittsburgh, Ervin moved to New York City in spring 1958,[2] initially working a day job and playing jam sessions at night. Ervin then worked with Charles Mingus regularly from late 1958 to 1960, rejoining various outfits led by the bassist at various times up to autumn 1964, when he departed for Europe.[2] During the mid-1960s, Ervin led his own quartet,[2] recording for Prestige Records with, among others, ex-Mingus associate pianist Jaki Byard, along with bassist Richard Davis and Alan Dawson on drums.

Ervin later recorded for Blue Note Records and played with pianist Randy Weston, with whom he recorded between 1963 and 1966.[2] Weston said: "Booker Ervin, for me, was on the same level as John Coltrane. He was a completely original saxophonist.... He was a master.... 'African Cookbook', which I composed back in the early '60s, was partly named after Booker because we (musicians) used to call him 'Book,' and we would say, 'Cook, Book.' Sometimes when he was playing we'd shout, 'Cook, Book, cook.' And the melody of 'African Cookbook' was based upon Booker Ervin's sound, a sound like the north of Africa. He would kind of take those notes and make them weave hypnotically. So, actually the African Cookbook was influenced by Booker Ervin."[4]

Between October 1964 to summer 1966, Ervin worked and lived in Europe, playing gigs in France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and The Netherlands. Basing himself in Barcelona, Spain, he featured regularly at the city's Jamboree Club. He recorded and broadcast while overseas, making albums with his own quartet, Dexter Gordon and Catalan vocalist Núria Feliu, featuring on various radio programmes and appearing at several jazz festivals, including a guest slot at the 1965 Berlin Jazz Festival, during which he performed a 25-minute improvisation. This performance was issued as "Blues For You" on the album Lament For Booker Ervin (Enja Records) in 1977.

Following his return to the United States in summer 1966, Ervin led his own groups in jazz clubs throughout the country, and appeared at both the Newport Jazz Festival (1967) and the Monterey Jazz Festival (1966) performing with Randy Weston; a recording of their performance was issued on CD in 1994. In 1968, Ervin again appeared at clubs and festivals in Scandinavia, broadcasting with the Danish Radio Big Band. He recorded again for Prestige, but in late 1966 was signed to West Coast label, Pacific Jazz, for whom he taped two albums, Structurally Sound and Booker 'n' Brass (1967), before switching to Blue Note. Ervin recorded two Blue Note albums under his own name, In Between and Tex Book Tenor, the latter going unissued during his lifetime, initially being released in the 1970s as part of a double album shared with recordings (on which Ervin features) made under the leadership of Horace Parlan (Back from the Gig). In 2005, Blue Note issued as single CD of Tex Book Tenor in its limited edition Connoisseur series.

Ervin's final recorded appearance occurred in January 1969, when he guested on a further Prestige album headed by teenage multi-instrumentalist Eric Kloss.

Ervin died of kidney disease in New York City in 1970, aged 39.[5] Most biographical accounts of Ervin's death give an incorrect date. His gravestone in The National Cemetery, East Farmingdale, New York, clearly shows the date as August 31, 1970.

In 2017, Ervin was the subject of a mini-biography written by English saxophonist and author Simon Spillett, published as part of an anthology package titled The Good Book (Acrobat Records)

Tributes

Booker Ervin has been remembered by many artists, Ted Curson called one of his albums Ode to Booker Ervin; the band "Steam", in their album Real Time, called one of their tracks "Tellefero"; and others...

Discography

As leader

- 1960: The Book Cooks (Bethlehem)

- 1960: Cookin' (Savoy)

- 1961: That's It! (Candid)

- 1963: Exultation! (Prestige)

- 1963: Gumbo! (Prestige) – with Pony Poindexter

- 1963: The Freedom Book (Prestige)

- 1964: The Song Book (Prestige)

- 1964: The Blues Book (Prestige)

- 1964: The Space Book (Prestige)

- 1964: 1964-10-15, Cafe Montmartre, Copenhagen, Denmark (Bootleg)

- 1965: Groovin' High (Prestige)

- 1965: The Trance (Prestige)

- 1965: Setting the Pace (Prestige) - with Dexter Gordon

- 1965: Doug's Night Club, Berlin, Germany (Bootleg)

- 1966: Heavy!!! (Prestige)

- 1966: Structurally Sound (Pacific Jazz)

- 1967: Live At Newport '67 (Bootleg) - with Chick Corea

- 1967: Booker 'n' Brass (Pacific Jazz)

- 1968: The In Between (Blue Note)

- 1968: Tex Book Tenor (Blue Note)

- Back from the Gig (Blue Note, issued 1976) – recorded 1964 and 1968; 2-LP set of two previously unreleased sessions, which were later issued as Horace Parlan's Happy Frame of Mind in 1988 and Ervin's Tex Book Tenor in 2005.

As sideman

With Bill Barron

- Hot Line (Savoy, 1962 [1964])

With Jaki Byard

- Out Front! (Prestige, 1964)

With Teddy Charles

With Ted Curson

With Núria Feliu

- Núria Feliu with Booker Ervin (Edigsa, 1965)

With Roy Haynes

- Cracklin' (New Jazz, 1963)

With Andrew Hill

- Grass Roots (Blue Note, 1968)

With Eric Kloss

- In the Land of the Giants (Prestige, 1969)

With Lambert, Hendricks & Bavan

- Havin' a Ball at the Village Gate (RCA, 1963)

With Charles Mingus

- Jazz Portraits: Mingus in Wonderland (United Artists, 1959)

- Mingus Ah Um (Columbia, 1959)

- Mingus Dynasty (Columbia, 1959)

- Blues & Roots (Atlantic, 1959)

- Mingus (Candid, 1960)

- Mingus at Antibes (Atlantic, 1960 [1976])

- Reincarnation of a Lovebird (Candid, 1960)

- Oh Yeah (Atlantic, 1961)

- Tonight at Noon (Atlantic, 1957-61 [1965])

- Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (Impulse!, 1963)

With Horace Parlan

- Up & Down (Blue Note, 1961)

- Happy Frame of Mind (Blue Note, 1963 [1988])

With Don Patterson

- The Exciting New Organ of Don Patterson (Prestige, 1964)

- Hip Cake Walk (Prestige, 1964)

- Patterson's People (Prestige, 1964)

- Tune Up! (Prestige, 1964 [1971])

With Sonny Stitt

- Soul People (Prestige, 1965)

With Mal Waldron

- The Quest (New Jazz, 1961)

With Randy Weston

- Highlife (Colpix, 1963)

- Randy (Bakton, 1964) - also released as African Cookbook (Atlantic) in 1972

- Monterey '66 (Verve, 1966 [1994])

External links

http://www.jazzshelf.org/ervin.html

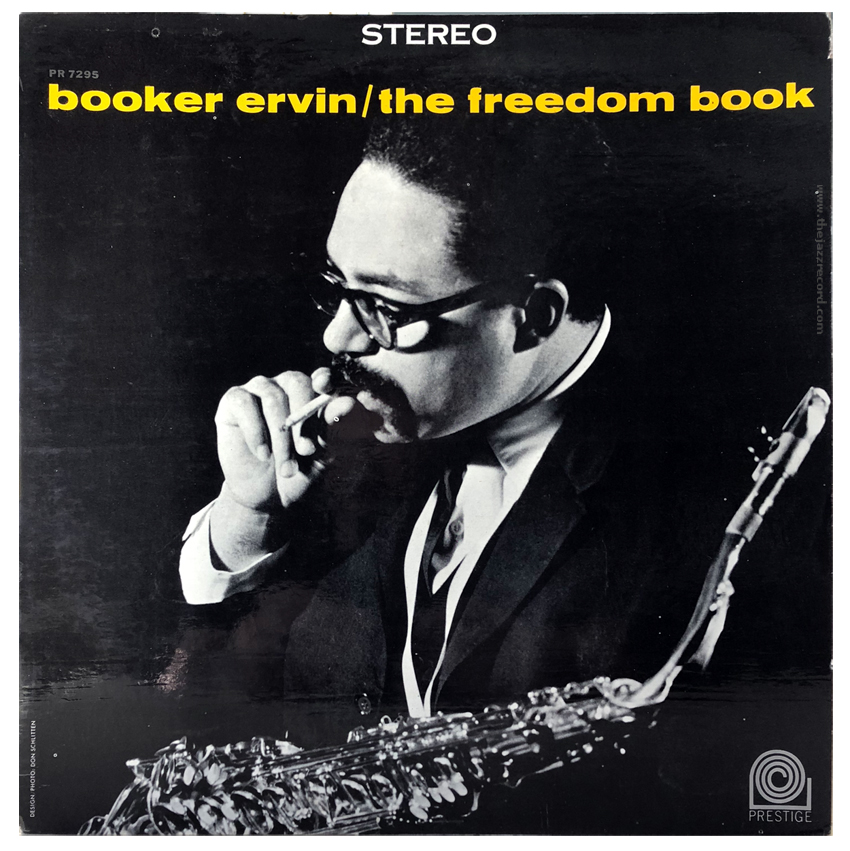

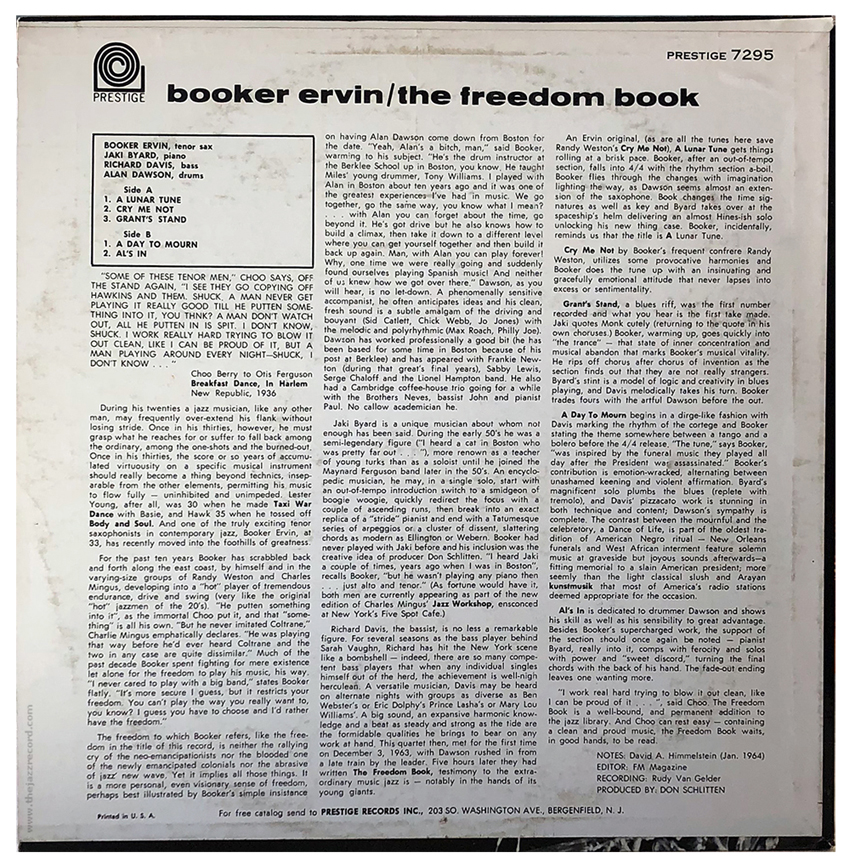

The Freedom Book

December 1963 / Prestige

This album reminds me of some of Jackie McLean’s Blue Note dates, where an impassioned bop and blues based saxophonist (who sometimes blows off pitch) explores new pastures but doesn’t abandon swing and chord changes. The rhythm section of Jaki Byard, Richard Davis, and Alan Dawson does some notable work here, and Ervin wails up a storm, starting with the modal “A Lunar Tune”. Ervin’s powerful tenor mixes microtonal cries, twisted motifs, and altered bop runs into a riveting solo that seems constantly in flux. This tune also has solos from Byard (mostly modern ideas, none of that old-timey stuff) and Davis, whose bass is so well recorded you can hear every pluck clear as day. Dawson’s lickety-split precision is impressive, and he sometimes shifts suddenly from a ride cymbal to tom-tom riffs and so forth. (Rather like his student Tony Williams, in fact.)

After “A Lunar Tune” comes “Cry Me Not”, a ballad that doesn’t sit very well in my ear due to Ervin’s off-key fluctuations. Horn players often lean sharp or flat for expressive purposes, but there’s a point where you’re just out of tune. I’m also not fond of Ervin’s tendency to let notes trail downward, which can sound crude in a tune such as this. “Grant’s Stand” is the most direct and exciting track, a blues in a pointy coat of armor that charges hard and gets a heated solo from Ervin. “A Day to Mourn”, recorded just a couple of weeks after Oswald’s crime, is a reflective elegy occasionally brightened by more affirmative patches. “Al’s In” begins in a dramatic way - almost like Coltrane’s “Drum Thing”, with the ritualistic mallets and bassline - and after picking up steam it turns to a lengthy Dawson solo. The Prestige RVG bonus track “Stella By Starlight” (originally released on a different LP, but recorded with the rest of the Freedom Book tracks) is perky and brief, although I’m again wary of Ervin’s tapered notes.

The Freedom Book is a unique record, parts of which display a

progressive sixties attitude. That being said, this music has none of

the harmonic mystery or rhythmic ambiguity you would get from Shorter,

Hancock, Hill, etc. Ervin has a more straightforward ethos, which makes

it more obvious when he’s stepping out, so to speak.

Tex Book Tenor

June 1968 / Blue Note Connoisseur

That’s Tex as in Texas tenor, which I assume refers to Ervin’s big tone and the bluesy curvature of his notes. He’s also got some Harlem in his horn, able to dive into a complex run in an instant. Both traits are heard on this fine hardbop-based album, recorded with a lineup of trumpeter Woody Shaw, pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Jan Arnet, and drummer Billy Higgins.

Flanagan’s sneaky groove “Gichi” opens with a slow funk bassline and a melody that owes a nod to “Blue Train” and “Canteloupe Island”, though Ervin’s wavering solo imports a foreign mystique to the track. The other solos are just as deep, and the rhythm vamp proves flexible when needed. Next up are a couple of meatier numbers, “Den Tex” (a tune that could have suited Blakey’s Jazz Messengers) and Shaw’s “In a Capricornian Way”, a 6/8 workout into which Ervin drops sustained calls and rapid bop lines. “Lynn’s Tune” is an ambling two-chord piece that may or may not sound too laid back, depending on how much fire one expects from an Ervin session, but it brings some relaxation after the two preceding tracks. The disc ends with the blowout “204”, a simple theme with improvisations that turn up the heat for ten solid minutes, including some thrilling passages from the leader.

I don’t know enough about Ervin’s catalog to objectively rate Tex Book Tenor

against his other titles, but it’s strong on its own, and it certainly

stands as a quality Blue Note of the hardbopping mold. The tunes are

right to the point, and there’s lots of soloing interest from Ervin and

Shaw, so I recommend it.

Back to Artists

https://www.popmatters.com/booker-ervin-the-freedom-book-2496214960.html

UK Release Date: 2007-06-11

In fact, this music shouldn't be confused with any other movement of any particular past time. It has a freshness not often found these days, and the freedom reference is mainly to the creative freedom of a tenor saxophonist as incapable of musical compromise as was Thelonious Monk. Ervin innovated in expression and substance without needing to be any kind of blatant revolutionary.

During a relatively short career ended by cancer in 1970, when he was barely forty, Ervin worked well with people doing the same serious thing he did, most famously Charles Mingus. The pianist in the perfectly organised quartet here is Jaki Byard, not only another sometime Mingus alumnus, but one of the great jazz pianists, and the most individual. The opener, "A Lunar Tune", might seem by name to belong rather to the Space Book album in this valuable series, but here we are with Byard's unique and heavy, confining chords. The startling rhythmic-harmonic structure resists possibilities of melodic development, so that when Ervin finds his improvisational line, it is -- it had to be -- intense and inspired. Though the complex chords are so much in Byard's fingers that the composition really seems his, it's in fact Ervin's. The empathy is startling throughout this session. There is a considerable sense of 'cry' in Ervin's sound, passion and melancholy and a focussedness more to be expected from a soprano saxophone, rather than a tenor. I would compare him with Dexter Gordon. Though he takes more emotional risks than that unsentimental master, he's never guilty of the least sentimentality. He might have learned from Coltrane's sound, and from Texan and midwestern tenor playing, but he is his own man.

"Cry Me Not" is a Randy Weston tune, from when the pianist's direction was more mainstream melodic (he has since gone to Africa, not least North Africa, for a new musical focus). Ervin also worked with Weston, and here the plaintive, lamenting presentation of direct melodic lines has aconsiderable emotional and spiritual depth. This is the plainer on Ervin's "A Day to Mourn", with its obvious allusion to JFK's murder in Dallas not so long before. It's almost a suite, with sections at different tempo, in different moods, and profoundly moving. Byard plays wonderfully lyrically, for once you might not know it's specifically him, but there can be no doubt that here's the extraordinary expressiveness of a major musician.

"Al's In" is named for Alan Dawson, the thoroughly admirable drummer who helped distinguish quite a number of Byard dates beside the present one. Through the melancholy opening, Dawson makes a considerable contribution, and then the pace picks up and Byard and the drummer are playing energetically and obliquely as Ervin weaves his way through choruses at once melancholy and driving, tending to produce something worthy of Fats Waller's phrase "fine Arabian stuff." The timekeeping work is in the extremely able hands of Richard Davis, a very great bassist, another musician who has been at the top of his profession a long time. Davis has the power to lead the band in after a tour-de-force solo on which Dawson makes use of tuned drums. There are also solos of a high order throughout from the bassist, very notably on the slightly modified, energy-filled blues "Grant's Stand", where -- as on every track here -- everybody is on strong form.

These musicians are plainly concerned to say something all the time; they're not just superlative technicians. By 21st century standards, they don't lack anything in that respect, or in musical daring, least of all Byard. The session was supervised by the legendary Rudy Van Gelder, and this is another of the series now appearing on the Prestige label in his remastering. I've not much to say about that, since by today's standards the music has such unusual depth it's hard to listen for anything else. It retains the abiding newness of any art which says important things: a very mature player, Ervin.

The lighter note of the added "Stella" is welcome at the end, but since it might well have been recorded specially and separately for the sampler it appeared on, it does allow a complaint unusual in this century. It's not shallow, but it's too short.

https://www.jazzviews.net/booker-ervin---the-good-book-the-early-years-1960---621.html

Every time I play I try to play as if it’s the last time I’m ever going to blow.’ If one quote can sum up a musician this one has a great deal to say about Ervin. The passion and urgency of his music is writ large on these four CDs.

His three earliest albums - ‘The Book Cooks’, ‘Cookin'’ and ‘That's It!’ are there complete, together with appearances on recordings led by Teddy Charles, Mal Waldron and Bill Barron. In total there is material from seven albums featured.

Ervin came from Texas and the R and B circuit. He was a Texas tenor and all that implies in the jazz world. Scuffling for a time on $5 a day he came up the hard way. That was his strength and also his weakness because many critics and taste-makers pigeon-holed him and failed to see beyond his origins.

Ervin was conscious of his lack of acceptance. After ‘The Book Cooks’, he experimented with the third stream and ‘Jazz In The Garden At The Museum Art’ was originally issued under vibraphonist Teddy Charles’s name. Mal Waldron’s album The Quest on the fourth CD is almost avant-garde, the pianist features alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy.

‘Uranus’ on CD2 taken very slowly is an impressive ballad performance, with Booker’s characteristic gruff, romanticism. The same quality is heard on ‘Booker’s Blues’ as Ervin soars above George Tucker’s walking slowly bass.

One additional reason for buying this collection is the notes by Simon Spillett. I have praised Spillett’s writing in the past but he has excelled himself here. Ervin was never given the critical plaudits that he should have received during his life and the literature about him is not easy to find. Spillett in the 51 pages here does not limit himself to the period of the recordings, he covers the life. What you have is a short book about Booker, including his early years in Texas, his time with Prestige, and when he was with Mingus. It is probably the best writing about Ervin anywhere. Spillett endeavours to answer questions about Ervin’s style and whether he can be considered an innovator. Spillett believes, and he argues it convincingly, that Ervin’s defining quality was honesty

This is a scholarly package. Playing through this CD you start to think about what is the right place for this musician in the jazz hierarchy and why such an important soloist is not widely recognised. He made a serious impact on many of the records that Mingus made at his peak but he was more than that and this selection of his early recordings looks at aspects of his work that were developed later: the passion, the velocity, the unique sound.

Reviewed by Jack Kenny

https://hhbrady.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/on-booker-ervin/

On Booker Ervin

He played with Charles Mingus a bunch; he’s got a very hard, brash tenor sax sound, coming from a setup that used a very narrow metal mouthpiece with a fairly pliant reed– he sounds like Don Byas 15 year later– and from Texas. Coltrane if he were more lyrical, a bit less sharp, and more traditional in his approach to melody and accompaniment. Again, basically Don Byas if he were younger.

I like his “books” series of records the best– they were called, chronologically, The Freedom Book (hard bop), The Song Book (standards), The Blues Book (I-IV-V), and The Space Book (the most “out there” of the four, but still “in,” see below). They were some very nice sessions, recorded through Prestige records from 1963 thru 1966.

There are also some early works that I really like, like “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” and “Well, well.” [See video, below.]

Want some late-period Ervin, like Tex Book Tenor? Getchu some “204,” if you want an introduction to that album– an album where the “new thing,” usually called “free jazz,” was coming into being, and you could tell that despite his background in Texas, blues-based, gutbucket, bartop-strutting indoctrination and love as a player, he really wanted to just lose it and get outer and outer as a player– you can practically feel his childlike enthusiasm for the new thing– but that Texas in him is still, somehow, stronger than that– and lets him flirt, over and over again, with free jazz, but still always sound like the Texas hard bop purveyor he is.

Plus, I love the fact that he always looks like a blerd, and yet has this hard, aggressive, full tenor sound and manner of playing and making melodies. Texas sax nerds from hell, so to speak.

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fer13

ERVIN, BOOKER T., JR.

ERVIN, BOOKER T., JR. (1930–1970). Tenor saxophonist Booker T. Ervin, Jr., was born in Denison, Texas, on October 31, 1930. His father played trombone with Buddy Tate and taught Booker the instrument at an early age. After finishing high school Booker joined the United States Air Force and was stationed in Okinawa, where he learned to play the tenor sax. When his service was completed in 1953 he enrolled at the Berklee School of Music in Boston, where he learned the essentials of music theory. The following year he moved to Tulsa and joined fellow Texan Ernie Fields.Though Fields's band was primarily a rhythm-and-blues outfit, Ervin's playing became more refined, and he developed a sense of self-confidence that in 1958 led him to New York City, where he became highly regarded in local jazz circles. Shortly after his arrival he met jazz legend Charles Mingus, who was impressed with his style. Ervin joined the Mingus Jazz Workshop, and this creative association led to a string of recordings, including the 1959 masterpiece Mingus Ah-Um. Mingus was demanding and at times dictatorial, but he nurtured creativity and encouraged his musicians to improvise. Ervin soon developed a reputation as one of New York's finest young sax players. His playing could be explosive, yet his sensitive touch was powerful. Though he continued playing with Mingus through the 1960s, Ervin also recorded several solo albums for Prestige Records, including The Blues Book, The Space Book, The Freedom Book, and The Song Book. He died of kidney disease on August 31, 1970, in New York City and was buried in Long Island National Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Jane Wilkie Ervin; a son, Booker; and a daughter, Lynn.

Graded on a Curve:

Booker Ervin

The Freedom Book

While he’s remembered foremost as a key contributor to the bands of jazz titan Charles Mingus, tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin also recorded a slew of outstanding albums as a leader, none of them better than his 1963 outing The Freedom Book. If the accumulated weight of post-bop’s golden era can sometimes feel like an unfathomable musical avalanche, this casually faultless quartet outing is unquestionably one for the hearing.

The Freedom Book inaugurates this group of four, followed in quick succession by The Song Book, The Blues Book, and The Space Book, and for those unacquainted with Ervin’s work the series easily serves as the best place to begin. And while it’s not essential to the experience, sequential listening greatly enhances the achievement of these sleek beauties, their diverse and dynamic contents laid to tape in under a year’s span. And The Freedom Book not only provides an ample helping of Ervin’s edgy, blues-inflected tone, but it presents the debut of what’s arguably his strongest overall band.

No Need To Cook The Books: Booker Ervin's Debut LP Reissued

NPR

Tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin came to New York in 1958. Pianist Horace Parlan heard him and invited Ervin to sit in one night with a band he worked in. That's how Ervin got hired by bassist Charles Mingus, who featured him on albums like Blues and Roots and Mingus Ah Um. Before long, Ervin was making his own records, like The Book Cooks, which has just been reissued on the re-revived Bethlehem label.

Ervin came from Northeast Texas on the Oklahoma line, field hollers coming at him from the east and cattle calls from the west. He punctuated his lines with high lonesome hollers before he got to New York and discovered that John Coltrane had a similar move. Ervin got ideas from Coltrane after that, but that cry was always his own. Coltrane's tone was as glossy as varnished hardwood. Booker Ervin's sound was more coarse, like a cane stalk shooting up out of rich earth.

For the ensemble shouts and background riffs, Booker Ervin is flanked by trumpeter Tommy Turrentine from Max Roach's band, as well as a Lester Young disciple and big-band vet, tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims. Sims could blow cool — he'd once recorded with Jack Kerouac — but also liked locking horns with fellow tenors. The saxophonists square off in a friendly way on The Book Cooks. Sims' tone is a little softer and rounder than Booker's.

The late '50s and thereabouts served as a great period for jazz rhythm sections — mighty bass players in particular. Nowadays, most bassists set the strings low to the neck so their fingers don't have to fight so hard. Back then, strings were higher and players couldn't get around so quickly. But they could pluck a string so hard, it made bass a percussion instrument. In "The Blue Book," for example, the great George Tucker's bass beat and Dannie Richmond's hi-hat and cymbals mail his message home.

The Book Cooks was Booker Ervin's first album under his own name, and it kicked off an early-'60s hot streak. He'd make the classics The Freedom Book and The Space Book with another great rhythm section, and recorded other good dates involving Tommy Flanagan, George Tucker or Dannie Richmond. But what really makes all those records is Booker Ervin's Texas shout on tenor saxophone, a sound that's both down-home and majestic.

https://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2015/05/booker-ervin-1930-1970.html

Monday, May 25, 2015

Booker Ervin: 1930-1970

During a recent listening of tenor saxophonists Booker Ervin and Zoot Sims on Booker’s The Book Cooks [Bethlehem Avenue Jazz R2 76691], I was really taken by the difference in sound that each got on the same instrument.

While Zoot’s tone was its usual bright, buoyant and bouncy self, Booker’s was darker, denser and more driving; one floated over the rhythm while the other pushed through it.

Hailing from Denison, Texas it’s easy to associate Booker’s style with the big bluesy, and wailing style that has become known as the Tenor Tenor Sound, a sound that the late Julian Cannonball Adderley once described as “the tone within the moan.”

Or as Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler describe it in The Encyclopedia of Jazz: “With a sound as big as the great outdoors, and a tidal rhythmic drive, he was in the lineage of the Texas Tenors.”

While Booker’s approach to Jazz improvisation was certainly rooted in The Blues, it seemed more expansive and more expressive. But what were the qualities that made it so?

I thought it might be fun to share some observations by other Jazz writers and critics whose ideas about Booker’s approach to Jazz helped shed light on my quest to know more about how he achieved his singularity.

Sadly, Booker didn’t have long to share his secrets as he died in 1970 at the age of 40!

Let’s begin with this overview of his career by Mark Gardner which is drawn from The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz:

“Booker Ervin (b Denison, TX, 31 Oct 1930; d New York, 31 Aug 1970) was the son of a trombonist who worked for a time with Buddy Tate, and he inherited his father's instrument: between the ages of eight and 13 he played trombone. He taught himself to play saxophone while in the air force (1950—53), then studied music in Boston for two years. His first professional engagement was with Ernie Fields's rhythm-and-blues band, with which he made his earliest recordings (c!956). Ervin rose to prominence as a member of Charles Mingus's group (1958-62). He also worked frequently in a cooperative quartet, the Playhouse Four, with Horace Parlan, George Tucker, and Al Harewood, and with Randy Weston. His best work as a leader was on nine albums recorded for Prestige (1963—6).

Ervin was a powerful player whose hard tone and fondness for the blues marked him as a member of the Texas school in the tradition of Buddy Tate, Arnett Cobb, and Illinois Jacquet.

He never allowed his formidable technique to obscure the emotional intensity of his playing, and he was one of the very few tenor saxophonists of his generation to remain untouched by the influence of John Coltrane and develop a wholly personal style.”

[There seems to be some debate about Coltrane’s influence on Booker, for example, Ira Gitler maintains that “Although Booker named Coltrane as his favorite, he was less indebted to him than were the majority of his contemporaries.”The Encyclopedia of Jazz.]

Continuing on with Ira’s assessment of Booker’s talents, the following is drawn from one of the many “Book” LP’s that Erwin made for the Prestige label from around 1963 66.

“If jazz had a bible it surely would be known as The Book of the Blues, for without the blues, jazz would be a salt-water fish in fresh water. This album is not the The Book of the Blues but it is The Blues Book [Prestige OJCCD-780-2/P-7430], or how Booker Ervin feels about the blues. "There's all kinds of blues," said Booker, "and I just wanted to play some of the different kinds."

That is stated simply enough (the blues for all their variety are basically simple, too) but when Ervin becomes involved in his highly emotional blowing, all is not that simple. It is not a matter of having to break your brains to comprehend his story — Booker plays from the heart of jazz directly to your heart — but the depth, breadth, and width of his approach arm it with ramifications that are anything but plain.

The pressure exerted in a hard, extended kiss doesn't always indicate the lack of equal intensity behind it, but if that surface force is really representative of the underlying feeling then you are dealing with something powerful. The loudness or hardness of a musician's delivery doesn't necessarily stand for true depth or sincerity, but if it does, look out, for you are in for a steam-cleaning from the convolutions of your cranium down to your entrails.

Booker Ervin's tenor is like a giant steamroller of a brush, painting huge patterns on a canvas as wide and high as the sky. There is nothing small about his sound, his soul, or his talent. … His passionate music is of the '60s but it has not lost touch with the tap-roots of jazz.

Booker's phrasing (the highly-charged flurries and the excruciating, long-toned cries), harmonic conception (neither pallid nor beyond the pale), and tone (a vox humana) add up to a style that is avant garde yet evolutionary, and not one that bows to fashion or gropes unprofessionally under the guise of "freedom".

“As I am writing these notes for Booker Ervin's third Prestige album, the yearly chore of filling out my Down Beat Critic's Poll ballot is very much on my mind. It is a chore because there are so many excellent musicians to choose from, and one is often forced to make rather arbitrary exclusions. But there are always a few instances in which there can be no doubt or equivocation. This year, Booker Ervin's name is one of those I'll put down without the slightest hesitation.

‘There's nothing on earth I like better than playing music,’ Booker Ervin once told me. His playing sounds like that. It is full of fire and conviction: nothing about it strikes the ear as forced, contrived or meretricious. It is no wonder that Charlie Mingus—a man who likes his music naked—has used Booker whenever he could get him.

Booker is his own man now, though. Not that that means he can't play with others ... his work with Randy Weston and Mingus in recent months proves well that he can. It does mean, however, that Booker has his own stories to tell and that he knows how to get them together without being coached. The best proof of that is his playing on his two previous Prestige albums …

And even better proof is the album at hand. Not that it is necessarily a better album all around; each of them has its points. It's that it is an album of great pieces from the jazz repertoire, and that such a collection represents a challenge to a player: the challenge of saying something definitively on themes that have already had definitive readings; the challenge of proving that you have your own voice not only when playing your own things on your own turf but also when playing on regulation fields with traditional rules. That's major league stuff, and Booker has what it takes.”

Perhaps Ed Williams summed it up best when he wrote this about Booker in his insert notes to Ervin’s 1968 Blue Note LP - The In Between [CDP 7243 8 59379 2]:

“BIG, FULL, OPEN, "LOUD." There are other ways of describing Booker Ervin's sound. Those just happen to be a few that I think are particularly apropos. "LOUD" as I mean it, connotes a basically honest projection of his emotions, without any special regard for modulation. That, coupled with his appreciation for the "big," "full" sound his instrument is capable of producing makes him seem "loud." The important thing is the fact that it's Booker, and his way of doing it. Self-expression is indeed a precious possession.”

The following video features Booker performing his original composition "Dee Da Do" with Richard Williams, trumpet, Horace Parlan, piano, George Tucker, bass and Danny Richmond, drums.

Booker Ervin

Randy Weston has no end of praise for Booker Ervin. Weston’s tonal portrait of his mother, “Portrait of Vivian,” was introduced on his 1963 recording, African Cookbook. He says that “only Booker Ervin could play the song.” And in his autobiography, African Rhythms, he says that Ervin’s solo on “Vivian” at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1966 was “one of the greatest… I would put that solo alongside any other tenor solo. Booker literally cries on the tenor saxophone.”Ervin worked with Weston between 1963 and ’66. The group Weston led at Monterey included Ray Copeland on trumpet, Cecil Payne on baritone sax, Vishnu Wood on bass, Lennie McBrowne on drums, and Big Black on congas. On his website, Weston points to this outfit with pride and calls it “an incredible band because number one, we had Booker Ervin, [who] for me was on the same level as John Coltrane. He was a completely original saxophonist. I don’t know anybody who played like Booker. But Booker, he was very sensitive, very quiet, not the sort of guy to push himself or talk about himself…He was a master saxophonist, and the song I wrote for my mother, ‘Portrait of Vivian,’ only he could play it; nobody else could play that song.

“In fact, African Cookbook, which I composed back in the early 60’s, was partly named after Booker because we (musicians) used to call him “Book…” Sometimes when he was playing we’d shout, “Cook, Book.” And the melody of African Cookbook was based upon Booker Ervin’s sound, a sound like the north of Africa. He would kind of take those notes and make them weave hypnotically. So, actually African Cookbook was influenced by Booker Ervin.”

Ervin’s career on the New York scene lasted only a decade before his death from kidney disease in 1969 at age 39. Notwithstanding his major contributions to the music of both Weston and Charles Mingus, he drew little attention during his lifetime, and he’s become a largely forgotten figure since. This is regrettable, for Ervin’s recordings maintain the raw power and emotional force for which they were known in their time.

We’ll hear the first of the series of “Books” that Ervin recorded for Prestige in tonight’s Jazz à la Mode. The Song Book features pianist Tommy Flanagan and includes one of the first recordings of “Come Sunday” that was made outside the realm of Ellingtonia.

Here’s a rare glimpse of Booker Ervin in action on Miles Davis’s seminal original, “Milestones.”:

http://www.thejazzrecord.com/records/2019/1/7/booker-ervin-the-freedom-book

Leading His Own Way: Booker Ervin - "The Freedom Book"

A2. Cry Me Not

A3. Grant’s Stand

B1. A Day To Mourn

B2. Al’s In

Jaki Byard - Piano

Richard Davis - Bass

Al Dawson - Drums

“I never cared to play with a big band,” states Booker flatly, “It’s more secure I guess, but it restricts your freedom. You can’t play the way you really want to, you know? I guess you have to choose and I’d rather have the freedom.”

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. Tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin came to New York in 1958. Pianist Horace Parlan heard him and invited Ervin to sit in one night with a band he worked in. That's how Ervin got hired by bassist Charles Mingus, who featured him on albums like "Blues and Roots" and "Mingus Ah Um." Before long, Ervin was making his own records. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews a reissue of Ervin's debut, "The Book Cooks."

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

KEVIN WHITEHEAD, BYLINE: Saxophonist Booker Ervin's sextet, playing a blues in the style of a sometime-boss Charles Mingus. It's from 1960's "The Book Cooks," back out on the re-revived Bethlehem label. Ervin came from Northeast Texas, on the Oklahoma line, field hollers coming at him from the east and cattle calls from the west.

He punctuated his lines with high, lonesome hollers before he got to New York and discovered John Coltrane had a similar move. Ervin got ideas from Coltrane after that, but that cry was always his own. Coltrane's tone was glossy as varnished hardwood. Booker Ervin's sound was more coarse, a cane stalk shooting up out of rich earth.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WHITEHEAD: For the ensemble shouts and background riffs, Booker Ervin is flanked by trumpeter Tommy Turrentine from Max Roach's band, and a tenor saxophonist who traveled in different circles, Lester Young disciple and big-band vet Zoot Sims. Zoot could blow cool - he'd once recorded with Jack Kerouac - but also liked locking horns with fellow tenors. The saxophonists square off in a friendly way on "The Book Cooks." Zoot's tone is a little softer and rounder than Booker's.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "1960")

WHITEHEAD: Booker Ervin and Zoot Sims' "1960," with Mingus' drummer Danny Richmond, and Tommy Flanagan taming an untuned piano. The late '50s and thereabouts was a great period for jazz rhythm sections - mighty bass players, in particular. Nowadays, most bassists set the strings low to the neck so their fingers don't have to fight so hard.

Back then, strings were higher, and players couldn't get around so quickly. But they could pluck a string so hard, it made bass a percussion instrument. Listen to the great George Tucker's bass beat and how Dannie Richmond's hi-hat and cymbals mail his message home.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WHITEHEAD: Trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, playing the blues. "The Book Cooks" was Booker Ervin's first album under his own name, and it kicked off an early-'60s hot streak. He'd make the classics "The Freedom Book" and "The Space Book" with another great rhythm section, and recorded other good dates involving Tommy Flanagan, George Tucker or Dannie Richmond. But what really makes all those records is Booker Ervin's Texas shout on tenor saxophone, a sound that's both down-home and majestic.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead writes for Point of Departure, Down Beat and eMusic, and is the author of "Why Jazz?" He reviewed the reissue of "The Book Cooks," featuring tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin on the Bethlehem label.

Copyright © 2013 NPR. All rights reserved.Booker Ervin - Tex Book Tenor LP (Blue Note Tone Poet Series)

Ships on: August 21, 2024

Following sideman appearances with pianist Horace Parlan in the early 1960s, Booker Ervin cut two stellar Blue Note records as a leader in 1968 including Tex Book Tenor which had to wait nearly 40 years until 2005 for its first standalone release. With a sleek post-bop quintet featuring trumpeter Woody Shaw, pianist Kenny Barron, bassist Jan Arnet, and drummer Billy Higgins,

the Texas-born saxophonist slices through a set of compelling

bandmember originals including Barron’s sinuous tune “Gichi” and Shaw’s

lilting waltz “In a Capricornian Way,” as well as Ervin’s lovely ballad

“Lynn’s Tune” and the hard-swinging “Den Tex,” named for his hometown of

Denison.

Blue Note Tone Poet Series

The Tone Poet Audiophile Vinyl Reissue Series

was born out of Blue Note President Don Was’ admiration for the

exceptional audiophile Blue Note LP reissues presented by Music Matters.

Was brought Joe Harley, a.k.a. the “Tone Poet,” on board to curate and

supervise a series of reissues from the Blue Note family of labels.

Extreme

attention to detail has been paid to getting these right in every

conceivable way, from the jacket graphics and printing quality to

superior LP mastering (direct from the master tapes) by Kevin Gray to

superb 180g audiophile LP pressings by Record Technology Inc. Every

aspect of these Tone Poet releases is done to the highest possible

standard. It means that you will never find a superior version. This is

IT.

This stereo Tone Poet Vinyl Edition was produced by Joe Harley, mastered by Kevin Gray (Cohearent Audio) from the original analog master tapes, pressed on 180g vinyl at Record Technology Inc. (RTI), and packaged in a deluxe tip-on jacket.

Tracklist:

A1: Gichi

A2: Den Tex

A3: In A Capricornian Way

B1: Lynn's Tune

B2: 204