AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2022/07/ronald-shannon-jackson-1940-2013.html

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/ronald-shannon-jackson

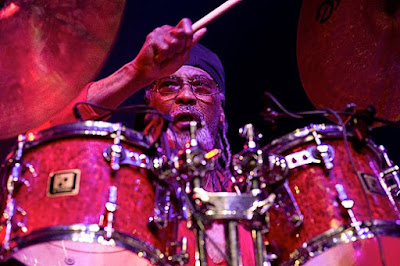

Ronald Shannon Jackson

I was born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas in 1940. Both my parents were music lovers. My mother played piano and organ at St. Andrew’s Methodist Church, and worked as a schoolteacher. My father owned the only black-owned local record store and jukebox business. On one side of my family is Curtis Ousley (who became famous as King Curtis). On the other is David “Fathead” Newman. I started playing drums in elementary school under the clarinetist John Carter, and in high school under Mr. Baxter, the same teacher who taught Ornette Coleman, Curtis Ousley, Dewey Redman, John Carter, Julius Hemphill, Charles Moffett, and James Jordan. I began playing professionally in Dallas with members of the Ray Charles band, and worked in Fort Worth, Houston, New Haven, and Bridgeport before moving to New York City in 1966. I attended New York University along with alto saxophonist René McLean, trumpeter Charles Sullivan, and bassist Abdul Malik, who had worked with Thelonious Monk.

Since that time, I have performed with many legendary jazz musicians including Charles Mingus, Betty Carter, Jackie McLean, Joe Henderson, Kenny Dorham, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Ray Bryant, Stanley Turrentine, Bennie Maupin, Shirley Scott and others.

I performed and recorded with three musical revolutionaries who virtually defined jazz in the 1970s: Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, and Ornette Coleman. I am the only musician to perform and record with all three.

After my final performance with Ornette Coleman on Saturday Night Live in 1979, I created The Decoding Society, whose classic recordings, including “Eye on You,” “Mandance,” “Street Priest,” “Barbeque Dog,” and “When Colors Play” breathed new life into American music. On more than 15 albums and countless tours, I helped launch the careers of some of the most talented musicians in jazz, including Bill Frisell, Byard Lancaster, Billy Bang, James “Blood” Ulmer, Vernon Reid, Melvin Gibbs, Akbar Ali, Jef Lee Johnson, Robin Eubanks, Eric Person, and James Carter.

During the 1980s, I traveled on behalf of the Voice of America and the U.S. Information Service to 15 African countries, India, and eight East Asian countries with The Decoding Society. During a solo trip to Africa, I composed much of “When Colors Play.”

My string quartets and other composed music have been performed by the most noted orchestras in Europe and the United States, the Cologne Jazz Society, WDR (Köln) and on radio in France, Germany, England, and Poland. I have performed in classical concerts in Europe and the U.S. with Eliot Fisk, Ruggiero Ricci, Dennis Russell Davies, and Garrett List.

I have received numerous awards and honors worldwide, including an NEA Jazz Composer Grant; three Meet the Composer awards; Jazz Artist of the Year-Tokyo; the key to the city of Osaka, Japan; an Endowment from the Government of Malaysia; the Texas Music Association Jazz Musician Award; a Letter of Commendation from the U.S.I.S. for concerts given in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. My solo album “Puttin’ on Dog” was one of the most played albums on National Public Radio for three years.

As an educator, I have given seminars and performed at Sanders Hall at Harvard University, and at Cooper Union, University of Tampa, Pepperdine University, University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Akron University, Brown University, Uppsala University in Sweden, Bryn Mawr College, Antioch College, University of Bridgeport, CalArts, Oberlin College, Grinnell College, the Cleveland Jazz Festival and in Indonesia, Taiwan and Malaysia. I was the only American representative at the 1993 World Drum Expo in South Korea, which was sponsored by KBS, Korean radio and television, and Korean airlines. I have performed live and for broadcast in France, Holland, Finland, England, the Czech Republic, Belgium, Poland, Switzerland, and Austria. My endorsements include Sonor drums, Paiste cymbals and gongs, and Shure microphones.

Ronald Shannon Jackson

(1940-2013)

Biography by Scott Yanow

Drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, and his Decoding Society of the 1980s, learned from the example of Ornette Coleman's Prime Time and were a logical extension of the group. They featured colorful and noisy ensembles; were not afraid of the influence of rock; and their rhythms were funky, loud, and unpredictable. Jackson played professionally in Texas with James Clay when he was 15. He moved to New York in 1966, where he worked with Byard Lancaster, Charles Mingus, Betty Carter, Stanley Turrentine, Jackie McLean, McCoy Tyner, Kenny Dorham, and most significantly Albert Ayler (1966-1967), among others. He took time off of the scene and then joined Ornette Coleman's Prime Time (1975-1979). Jackson also worked with Cecil Taylor (1978-1979) and James "Blood" Ulmer (1979-1980). The Decoding Society (formed in 1979), through the years, featured many talented and advanced improvisers, with the best-known ones being Vernon Reid, Zane Massey, Billy Bang, and Byard Lancaster. Jackson also played with the explosive group Last Exit (starting in 1986), and in the early '90s with Power Tools. Ronald Shannon Jackson's music is not for easy-to-offend ears. The drummer died at his home in Fort Worth, Texas on October 19, 2013 after battling leukemia; he was 73 years old.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_Shannon_Jackson

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ronald Shannon Jackson (January 12, 1940 – October 19, 2013) was an American jazz drummer from Fort Worth, Texas.[1] A pioneer of avant-garde jazz, free funk, and jazz fusion, he appeared on over 50 albums as a bandleader, sideman, arranger, and producer. Jackson and bassist Sirone are the only musicians to have performed and recorded with the three prime shapers of free jazz: pianist Cecil Taylor, and saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler.[2]

Musician, Player and Listener magazine writers David Breskin and Rafi Zabor called him "the most stately free-jazz drummer in the history of the idiom, a regal and thundering presence."[3] Gary Giddins wrote "Jackson is an astounding drummer, as everyone agrees…he has emerged as a kind of all-purpose new-music connoisseur who brings a profound and unshakably individual approach to every playing situation."[4]

In 1979, he founded his own group, the Decoding Society,[1] playing what has been dubbed free funk: a blend of funk rhythm and free jazz improvisation.

Early life and career

Jackson was born in Fort Worth, Texas.[1] As a child, he was immersed in music. His father monopolized the local jukebox business and established the only African American-owned record store in the Fort Worth area. His mother played piano and organ at their local church. Between the ages of five and nine he took piano lessons.[5] In the third grade, he studied music with John Carter.[6]

Jackson graduated from I.M. Terrell High School,[7][8] where he played with the marching band and learned about symphonic percussion.[9][10] During lunch breaks, students would conduct jam sessions in the band room.[5]

Around the same time, Jackson's mother bought him his first drum set to encourage him to graduate from high school. By the age of 15, he was playing professionally. His first paid gig was with tenor saxophonist James Clay, who went on to join Ray Charles as a sideman.[5]

Jackson recalled that "we were playing four nights a week, with two gigs each on Saturday and Sunday, anything from Ray Charles to bebop. People were dancing, and when it was time to listen, they'd listen. But I was brainwashed into thinking you couldn't make a living playing music."[5]

After graduation, Jackson attended Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. He chose Lincoln because of its proximity to St. Louis and accessibility to great musicians touring the Midwest. His roommate was pianist John Hicks. As undergraduates, they "spent as much time performing together as studying."[11] The Lincoln University band included Jackson, Hicks, trumpeter Lester Bowie, and Julius Hemphill on saxophone.[12]

Jackson then transferred to Texas Southern University, and from there went to Prairie View A & M. He decided to study history and sociology at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut. Jackson intended not to play music at all, but after exposure to various artists and styles, he concluded that "the beat is in your body" and "the music you play comes from your life."[13] By 1966, Jackson received a full music scholarship to New York University through trumpeter Kenny Dorham.[14]

New York and the Avant-Garde (1966–1978)

Once in New York, Jackson performed with many jazz musicians, including Charles Mingus, Betty Carter, Jackie McLean, Joe Henderson, Kenny Dorham, McCoy Tyner, Stanley Turrentine, and others.[15] Whenever he would ask Charles Mingus to consider him for his group, Mingus used to push him "rudely out of his way". After Jackson sat in with pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi, he heard loud clapping behind him. It was Mingus, who asked him to play with his band.[16]

In 1966 Jackson recorded drums for saxophonist Charles Tyler's release, Charles Tyler Ensemble. Between 1966 and 1967, he played with saxophonist Albert Ayler and is featured on At Slug's Saloon, Vol. 1 & 2. He is also on disks 3 and 4 of Ayler's Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962–70). Jackson said Ayler was "the first (leader) that really opened me up. He let me play the drums the way I did in Fort Worth when I wasn't playing for other people."[5] John Coltrane's death in July 1967 devastated Jackson. He spent the next few years addicted to heroin. He said, "I couldn't play drums then, spiritually.... I just didn't feel right."[5] From 1970–74, he did not perform, but continued to practice.[15]

In 1974, pianist Onaje Allan Gumbs introduced Jackson to Nichiren Buddhism and chanting. Although initially reluctant, Jackson decided to try it for three weeks. "Then three months had passed. It pulled me together and pulled me out and I was able to focus. I was a Buddhist and a vegetarian for 17 years."[5]

By 1975 he joined saxophonist Ornette Coleman's electric free funk band, Prime Time.[15] During his stint in Prime Time, Coleman taught Jackson composition and harmolodics. Jackson says that Coleman told him he was hearing music "in that piccolo range," and encouraged him to compose on the flute. Jackson went to Paris with Prime Time in 1976 to perform concerts and record Dancing in Your Head and Body Meta.[5]

In 1978, Jackson played on four albums with pianist Cecil Taylor: Cecil Taylor Unit, 3 Phasis, Live in the Black Forest, and One Too Many Salty Swift and Not Goodbye.[17]

The Decoding Society and Other Projects (1979–1999)

Jackson formed his band, The Decoding Society, in 1979, as a showcase for his blend of avant-garde jazz, rock, funk, and ethnic music.

The instrumentation and arrangements, along with Jackson's compositions and drum style, brought The Decoding Society critical acclaim.[18] Although considered to be part of the "new fusion" movement that emerged from Ornette Coleman's harmolodic concepts, Jackson was able to implement a voice of his own.[19]

The Decoding Society's music can be hot, savage, and danceable, or cool, gentle, and contemplative. American, Eastern, and African sounds are distilled under Jackson's guidance. Meters, feels, tempos, and stylistic references are heard throughout different compositions; many times within a single piece of music.[19]

Unlike many of Jackson's contemporaries, The Decoding Society incorporates pop music elements into its avant-garde approach. Guitarist Vernon Reid has said of Shannon that he "wasn't an ideological avant-gardist. He made the music he made from an outsider's view, but not to the exclusion of rock and pop – he wasn't mad at pop music for being popular the way some of his generation are. He synthesized blues shuffles with African syncopations through the lens of someone who gave vent to all manner of emotions…the collision of values in his music really represents American culture."[5]

Common characteristics among the incarnations of The Decoding Society include doubled instrumentation (basses, saxophones, or guitars). Polyphony often predominates harmony; compositions are not focused on one key. Polyphonic textures equalize harmony, rhythm, and melody, dispensing with traditional ideas of key and pitch. Each instrument can play a rhythmic, harmonic, or melodic role, or any combination of the three. The lines between solos, lead instruments, and accompaniment are blurred. Looseness in pitch and rhythm create heterophony within unison-based parts, which also adds to the tonal ambiguity.[19]

Melodies can alternate from busy, frenetic, multiple themes to simple, lazy, lyrical phrases. They often function as both heads and melodic material to accompany one or more soloist. Sometimes the melodies are diatonic, other times they are bluesy; occasionally they sound "Eastern". Although The Decoding Society is more of a composer's band rather than a vehicle for soloing or drumming, free-blowing solos abound, and Jackson's thunderous playing is heavily featured.[19]

Throughout the years, the Decoding Society has featured the performances of Akbar Ali, Bern Nix, Billy Bang, Byrad Lancaster, Cary Denigris, Charles Brackeen, David Fiuczynski, David Gordon, Tomchess, Dominic Richards, Eric Person, Henry Scott, Jef Lee Johnson, John Moody, Khan Jamal, Lee Rozie, Masujaa, Melvin Gibbs, Onaje Allan Gumbs, Reggie Washington, Reverend Bruce Johnson, Robin Eubanks, Vernon Reid, and Zane Massey.[20]

In addition to leading Decoding Society lineups, Jackson was involved in other projects. Guitarist and fellow Coleman alumnus James Blood Ulmer recruited Jackson for another group that intended to push harmolodics to a new level [18]

In 1986 Jackson, Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brötzmann, and Bill Laswell formed the free jazz supergroup, Last Exit, which performed and released five live albums and one studio album, before Sharrock's death in 1994 saw the end of the band.[21]

In the late 1980s, Jackson teamed up with Laswell on two other projects: SXL, with violinist L. Shankar, Senegalese drummer Aiyb Dieng, and Korean percussion group SamulNori,[22] and the free jazz trio, Mooko, with Japanese saxophonist Akira Sakata.[23]

With the help of some grants, Jackson took a three-month trip to West Africa and visited nine countries.[5] The trip, both a personal and artistic milestone, inspired music for the Decoding Society's When Colors Play, recorded live at the Caravan of Dreams in September 1986.[19] Author Norman C. Weinstein detailed the excursion in a chapter of his book, A Night in Tunisia: Imaginings of Africa in Jazz, titled "Ronald Shannon Jackson: Journey to Africa Without End."[24]

In 1987, Jackson formed an avant-garde power trio with bassist Melvin Gibbs and guitarist Bill Frisell called Power Tools. They released and toured behind an album titled Strange Meeting.[25] Writer Greg Tate referred to the project as "that awesome and under-sung Power Tools album…in my humble opinion, the most paradigm-shifting power trio record since Band of Gypsys."[26]

Later career (2000–2013)

His output slowed in the early 2000s due to nerve damage in his left arm. After consulting with a neurologist, Jackson declined surgery and was able to regain his strength through years of physical therapy. Physical limitations did not diminish his output as a composer, and he unveiled new material on YouTube in 2012.[27]

Jackson joined trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith's Golden Quartet with pianist Vijay Iyer and double-bassist John Lindberg in 2005. Their collaboration is documented on the Tabligh CD[28] and the Eclipse DVD.[29]

He played with the Punk Funk All Stars in 2006, which included Melvin Gibbs, Joseph Bowie, Vernon Reid, and James Blood Ulmer.[30] In 2008 Jackson and Jamaaladeen Tacuma toured Europe with The Last Poets; this collaboration was documented in the film "The Last Poets / Made in Amerikkka" directed by Claude Santiago.[31]

In 2011 Jackson, Vernon Reid and Melvin Gibbs formed a power trio called Encryption. During their trip to the Moers Festival in Germany, Jackson suffered a heart attack and underwent an angioplasty.[32] The next day, he checked himself out of the hospital to play with Reid and Gibbs at the festival. Afterwards, Jackson checked himself back in for medical observation.[33]

On July 7, 2012, Jackson performed at the Kessler Theater in Dallas with the latest version of the Decoding Society, which includes violinist Leonard Hayward, trumpeter John Weir, guitarist Gregg Prickett, and bassist Melvin Gibbs. The new compositions were described as being as strong as the best of his recorded work.[34] The performance was voted as one of the Ten Best Concerts of 2012 in the Dallas Observer.[35]

Death

Jackson died of leukemia on October 19, 2013, aged 73.[36]

Discography

As leader

- Eye on You (About Time, 1980)

- Nasty (Moers Music, 1981)

- Street Priest (Moers, 1981)

- Mandance (Antilles, 1982)

- Barbeque Dog (Antilles, 1983)

- Montreux Jazz Festival (Knit Classics, 1983)

- Pulse (Celluloid, 1984)

- Decode Yourself (Island, 1985)

- Taboo (Venture/Virgin, 1981–83)

- Earned Dream (Knit Classics, 1984)

- Live at Greenwich House (Knit Classics, 1986)

- Live at the Caravan of Dreams (Caravan of Dreams, 1986) AKA Beast in the Spider Bush

- When Colors Play (Caravan of Dreams, 1986)

- Texas (Caravan of Dreams, 1987)

- Red Warrior (Axiom, 1990)

- Raven Roc (DIW, 1992)

- Live in Warsaw (Knit Classics, 1994)

- What Spirit Say (DIW, 1994)

- Shannon's House (Koch, 1996)

(dates are recording, not release)

With Last Exit

- Last Exit (Enemy, 1986)

- The Noise of Trouble (Enemy, 1986) with guests Akira Sakata and Herbie Hancock

- Cassette Recordings '87 (Celluloid, 1987)

- Iron Path (Virgin, 1988)

- Köln (ITM, 1990)

- Headfirst into the Flames (Muworks, 1993)

As sideman

With Albert Ayler

- At Slug's Saloon, vols. 1&2 (ESP, 1966 [1982])

- Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962–70) (Revenant, 1962–70 [2004])

- La Cave Live, Cleveland 1966 Revisited (ezz-thetics, 1966 [2022])

With Ornette Coleman

- Dancing in Your Head (A&M, 1973, 1975)

- Body Meta (Artists House, 1975)

With Bertrand Gallaz

- Talk To You In A Minute (Plainisphare, 1993)

With Bill Laswell

- Baselines (Elektra Musician, 1982)

With Mooko

- Japan Concerts (Celluloid, 1988)

With Music Revelation Ensemble

- No Wave (Moers Music, 1980)

- Music Revelation Ensemble (DIW, 1988)

With Power Tools

- Strange Meeting (Antilles, 1987)

With SXL

- Live in Japan (Terrapin/Sony Japan, 1987)

- Into the Outlands (Celluloid, 1987)

With Wadada Leo Smith

- Tabligh (Cuneiform, 2008)

With Cecil Taylor

- Cecil Taylor Unit (New World, 1978)

- 3 Phasis (New World, 1978)

- One Too Many Salty Swift and Not Goodbye (hat Hut, 1978)

- Live in the Black Forest (MPS, 1978)

With Charles Tyler

- Charles Tyler Ensemble (ESP, 1966)

With James Blood Ulmer

- Are You Glad to Be in America? (Rough Trade, 1980)

- America – Do You Remember the Love? (Blue Note, 1986)

with John Zorn

- Spillane (Nonesuch, 1986–87)

http://davidbreskin.com/magazines/1-interviews/ronald-shannon-jackson/

Ronald Shannon Jackson

view pdf of the article

by Rafi Zabor and David Breskin

Note: David Breskin conducted this interview (from which all the questions have been excised, leaving Ronald Shannon Jackson to speak on his own, as he did so well) but then had to leave town on another assignment before the piece was ready for publication. The introductory and interstitial texts were subsequently authored by jazz drummer and frequent Musician contributor Rafi Zabor (who would go on to win the 1998 PEN / Faulkner Award for Fiction for his first novel, The Bear Comes Home.) Within a few months of the publication of this interview, db was on the road with Ronald Shannon Jackson and The Decoding Society, doing live sound on a European tour, and immediately thereafter, co-producing the album, Mandance.

I was born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas and I stayed there until I went off to college. My mother plays piano and organ, and my father always wanted to play the saxophone. He was the local juke-box man. He owned juke-boxes and record stores. He had the record store in the black neighborhood, and we sold gospel and race music and Red Foxx stuff, which was basically under the counter and illegal — for parties and all. We always had to put the most sellable blues on the jukes, because we didn’t have that much money and so my father had to make the right choices; it would boil down to choosing Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters and B.B. King and Bobby Bland and Guitar Slim and Gatemouth Brown. So I grew up listening to them, because that’s what he put on the boxes — all that intermixed with Horace Silver, who was hitting at the time with that Blue Note scene. This was mid-50s. I used to spend my summers out in the country, place called Aola, Texas, way out there in east Texas. Place just has a barber shop and a little grocery store. Train didn’t even stop. Local man just put the mail up on a post, trainman would snag it on the way through. That was the environment I grew up in.

I was about four years old when I saw a set of drums in a church basement in Houston, and I knew I was going to be doin’ that. I didn’t know what they were, but I knew they had something to do with me. I used to keep time on pots and pans and everything I could find to keep time on. When I was in 3rd grade was the first time I had actual access to a set. Fellow named John Carter, who now teaches at the University of Southern California, was my first music teacher. In the 3rd grade they asked everybody who had training on instruments, they write your name down an’ all, then they send you to the band room. They gave me a clarinet, but I moved to the drums in the back of the room — which I knew I wanted to do. I just happened to have a natural talent for it. So we had to learn the Sousa’s, other marches by English composers. By the time I got to junior high, we were playing Wagner. At high school, it was marching music during the football season and classical music during the rest of the year. Now for our own enjoyment, we used to jam during lunch hour. The band director let us have the band room. We had access to all the instruments, every day during lunch. He would just lock us in. We didn’t go to lunch in those days. We weren’t playing blues, we were playing jazz. Charlie Parker had been through town and there was a local contingent of guys who could really play. Dallas was bigger than Fort Worth, but Fort Worth always had the cats who were on the money in terms of the music. It had a lot to do with our music teacher there, Mr. Baxter. He played all the instruments. He loved to perfect a band. He put his whole life into music — to the point it would drive him mad, so dedicated, totally dedicated. A lot of people come through this man: he was Ornette Coleman’s teacher, he was Dewey Redman’s teacher, he was Julius Hemphill’s teacher, Charles Moffett’s teacher and John Carter’s and mine. King Curtis, my father’s cousin, also came from there. Billy Toman and I used to take our instruments home over the weekends, he was a saxophone player, used to play with Mingus. We couldn’t get into the clubs much. I’d sneak in a lotta places ’cause my father had the juke-boxes, just long enough to catch a few sounds until someone got wise and realized I wasn’t there dealing with the juke-boxes. Then we started goin’ to Dallas. Saw a group called James Clay and the Red Tops, and I loved what everybody was doing and I wanted to sit in but I just wouldn’t. Fellow named Leroy Cooper, a baritone player who played with Ray Charles, was the one that got me up there. Billy had told him I played drums. I was 15 then.

I’d been so indoctrinated to the fact that the life of a musician is so hard. I’d seen a lot of musicians, and I thought I could do better in terms of living. But the music was something I just did. In church, I sang in the choir. In school, I sang in the choir. And the bands. And I played some gospel music, some spiritual music. It took a long time to actually make up my mind that this was what I was gonna do.

I went off to school, to Lincoln University in Missouri, to study music. But when I got there I realized it wasn’t the kind of music I wanted. It wasn’t jazz, which was the music I most liked to play. I’d been gigging in Dallas with James Clay and playing in Fort Worth. Ornette, of course, was long gone by that time, and Hemphill was four, five years ahead of me. So we didn’t have a chance to play together until I got to college. In the marching band and symphony orchestra at Lincoln was Oliver Nelson, Lester Bowie, John Hicks, Julius Hemphill, a bass and tuba player, Bill Davis, and myself. There we all were in Jefferson City, Missouri. I had chosen Lincoln over other schools because Lincoln was right between St. Louis and Kansas City and I knew I’d get the chance to catch all the players that came through there. With the background I had, I was afraid to come to New York, absolutely frightened to death.

At Lincoln, I learned how to play — uh, I had to play — hillbilly music, which paid for my food. Pure Ozark music. Also, some Boots Randolph-type music, screamin’ saxophone sorta thing. Just drums and sax in these back hills clubs up in the Ozarks. It was what they call, real redneck music. Redneck Honky-tonk music, it had nothin’ to do with the blues. And there were like no black people in the club except me and the sax player. And they would call out the weirdest songs and we’d have to play ’em and make those people dance. Just me and the saxist: that’s how I got a foundation in being able to play without a bass player or anything else. Actually, it was like a life and death situation. The saxophone player grew up in that area and all the white people knew him — he was their local idol, they always gave him work. And so he could play any song that they would ever want; it might be outa tune, in the wrong key, whatever, but he could play it. He had a good ear and he could scream.

We’d have to play “The Yellow Rose of Texas” and then go to “Polkadots and Moonbeams” then “Honky-tonk” then maybe “How Much Is That Doggie In The Window.” People came down to get drunk and we couldn’t jive ’em, we really had to be playing. They’d throw all kinds of things at us. Look: we were black so we were in trouble anyway. So we’d better not do nothin’ wrong, or else; you know, just play it boy. I guess we usually came through the front door but we had to come through it pretty early in the night, which was pretty much the same thing as coming in the back. And we’d play roller skating rinks, which were much better than the bars. No organ. Just me and the saxophone. In the Ozarks I had to learn how to fill in for other instruments, like the organ at the rink, I’d hear in my head where those other instruments were supposed to be and I’d know how to fill in — and still swing.

See, the whole gist of what I’m doing now is to play music that swings — swings just as madly, just as profoundly as any music has ever swung — but without having to play it in the context of keeping time. In other words, I play rhythms and let the rhythms create the time itself. So having to do those type of things early on — playing with no bass or no piano for instance — helped me think about the drums in a different way. And I had to play for everything and anything: bar mitzvahs, weddings too, and Mass, and honky-tonks, and everything else. I bought my first telephone in New York with money from a strip-tease gig. Me and a saxophone player from Philly, C. Sharpe, had that gig. Bump an’ grind, boom ba-ba-boom ba-ba-boom and all that. Most of it was on the toms and the bass drum, geared to your basic hip-shaking and then the undressing ceremony. Uh-huh, I’ve played everything.

I was at Lincoln a few weeks less than a year, ’cause I took off to see John Coltrane and Dizzy in St. Louis. Coming from Texas you could only hear all these people on record. I played in Dallas that summer and after that enrolled at Texas Southern University in Houston. I started working an evening gig, then an evening gig and an after-hours gig. I was working so much, I quit school again. My father became very ill and I went back home to run his business. It was then I decided to take school very seriously, in terms of trying to learn something other than music.

I had dissipated an awful lot as a young person. I was always with people much older and so I was always doin’ what they were doin’. In order to prove myself I was always doin’ it to the extreme. So when I went home to take care of business it was a breather for me; I got away from the life I’d been living. I’d been playing a regular singer-type gig with bass and drums from 8-to-12, and then a be-bop and blues gig from ’bout one till 6 or 7 in the morning in these gambling joints. Gambling’s illegal down there and these joints stayed open all night long. We used to get raided all the time. Shot at and everything else. They’d be so bombed out all the time they just didn’t care. The raids wouldn’t be the sort of thing that they’d cart the black folk to jail, because where I grew up if black people killed each other it was: “Oh well, another nigger dead.” No big deal. What the cops wanted was to catch up all the piles of money before the cats could grab it away. Now Texas allowed everybody to carry a gun, so everybody had one.

So from there I decided I had to go to school and study. And I went and studied ancient philosophy and business and tried to work from that end. As a music major, they’d been teaching me out of the same books as in high school and I’d been playing the same Sousa and Wagner and the other European classics. And technically, the teachers couldn’t teach me nothing new. Meanwhile, I was looking for people to teach me jazz. I had this concept that people actually taught jazz; I’d been playing be-bop in night clubs and had the notion that someone was teaching this somewhere.

I wasn’t aware at the time that the music you play comes from your life, not teaching. I was living that type of life and that’s where the music was comin’ from. But some of the cats I’d run into on gigs would tell me a few things about the drums and I picked up on that. I wanted to go to New York but I was too scared, so I found myself a school near there — University of Bridgeport up in Connecticut — that would be close enough so I could come down to the city. I started comin’ in and go my first gig with a foot-stompin’ piano player over at the Inner Circle on Sutton Place. Just piano and drums. I played a lot of duos.

At the University of Bridgeport I was truly and sincerely trying to become an American businessman. My parents wanted that. I had fucked up so royally from all the nightlife that it was time to put this other thing together. But then I found that wherever I’d be, I’d be playing music. Or if I had some time alone I’d be drawing drum sets, designing them the way I wanted them to be. I was working at United Aircraft as a market researcher. I was only there to do calculations, so I’d take off with other reports down to New York, and down there I started putting together the kind of drum set I wanted. So, needless to say, I was back playing the drums.

I gigged around in Connecticut and then moved to the city for good early in ’67. I moved into Bennie Maupin’s place between Avenues C and D on 10th Street. Cecil McBee was living right up the street. Another bass payer’s apartment became vacant and I moved in there. One night at Slug’s, Grachan Moncur told me about there were scholarships open for jazz musicians if you could qualify and take the tests and so on. The biggest requirement was to be able to play. I got a scholarship to N.Y.U. College of Music. My life was split between the strip-tease gig, playing at Slug’s or The Five Spot or on Staten Island or New Jersey or that morning playing for high school kids. This was the situation.

Then I began working for Albert Ayler. Charles Moffett took me to a recording session he was supposed to do. He didn’t want to do it because he was working with Ornette, so he asked me to do it. Charles Tyler was the leader. I met him for the first time in the studio. He told me what his kind of music was. We sat down and made the record. All first takes, no second takes. That was my very first record. Never got paid. But one of the people in the studio was Albert Ayler. Now I don’t know if I’d even heard of Albert Ayler; if I had, I didn’t remember him. Albert comes up to me and said he liked the way I played, would I join his band. He’d just come back from Europe and was looking for a drummer. I said: O.K. it didn’t bother me, didn’t faze me one way or another ’cause not only didn’t I know who he was, but I didn’t even think he was serious.

He called me. We started playing gigs down at the Lafayette Theatre. I’d been playing by myself a lot, and I’d played with duos and trios and orchestras and choirs, but never with someone who told me to play everything I could possibly play. It blew my mind. I could try anything. All four mediums — both feet, both hands — used to the maximum, with total concentration in each one. You know, the whole set-up was so massive: the total spiritual self, which can be a million different things at one time, but trying to make it concise and particular at a given moment. It was like somebody taking the plug out of a dam. So I was playing that, but one night I went over to the Five Spot where Mingus was trying to play “Stormy Weather.” That was one of the songs I used to practice by myself all the time; my father used to love to hear Lena Horne sing “Stormy Weather,” so it was in my psych. I used to practice it all the time, I could always play phrases on the drums from “Stormy Weather,” Now Dannie Richmond was the drummer, but I had the key for the music Mingus wanted to play. But he said NO. Allright, during their break Toshiko Akioshi comes out to play some solo piano. Herb Bushier comes up and starts playing bass. So I figure, why not. When we got through playing, some tune like “I Remember April,” the audience started applauding like mad. I remember a guy, right behind me, clapping LOUD. And then the guy says, “O.K. come in tomorrow.” I turn around and it’s Mingus Crazy. I enjoyed it, I played with the group as the second drummer for a few weeks. He liked what I was doing and wanted to rent some tympani for me, ’cause Dannie was his regular drummer and he knew I could play them, and he was working on some pieces and all. But Albert Ayler had gotten more work and there was a conflict. I couldn’t do both. I’d already been bitten by this Albert Ayler bug — he had such presence, he could play just two notes in a club and everyone would have to stop to listen — so I went to work for Albert. Which went along fine, until Albert wasn’t working for awhile.

Then I started up with Betty Carter. Working with her was one of the highlights of my life. The way she sings — rhythmically, her be-bop phrasing — really allowed me to extend the playing of my left hand tremendously. She would play with the rhythm section. It was a beautiful thing, but unfortunately I was going through a lot of degrading things in my personal life and I dropped out of the scene for awhile. This is at the end of the 60s, marches, riots and all that. I moved to Queens. Worked on a lot of social jobs: high school gigs during the week, small bars at night, every Saturday morning a bar mitzvah or an Irish wedding, which paid me more money than I made all week on all my other jobs. At this time I made a recording with Weldon Irvine. I met him when I worked with the Joe Henderson/Kenny Dorham big band. Then I did a record with Teruo Nakamura. And then I started chanting.

I was driving to a gig with a young pianist Onaje Alan Gumbs. I was a real speed demon, so I was driving very fast. So he starts chanting. I’m speeding down the highway, double-clutching, and he’s scared to death. He’s chanting: Nam Myoho Renge Kyo and I say: what in the hell are you saying? He said he’d tell me about it after the gig. He did, and I picked up from there. My life changed. I realized all the things I’d been seeking were right there in the rhythm of chanting Nam Myoho Renge Kyo. In other words, all the discipline I needed in my life — the thing that was gonna put the pieces together for me — was the chanting. I moved back to Manhattan. I chanted. I wanted to live off music, not have to do anything else. That happened. I continued chanting; I wanted to put it to the test in terms of my life.

Up until this time I was playing totally from natural talent. But this made me think of music in a different way. I’d been very egotistical: I could go anywhere and just play, literally, in any musical context. And I did it all the time, sitting in all over New York: Latin, blues, rock, jazz, whatever, gospel music. But when I started chanting in ’74, this changed. I began practicing. I went to a religious convention in Hawaii, played out there in a trio with Buster Williams and Onaje. Herbie (Hancock) sat in. I came back and kept chanting. Had a steady gig in a cabaret, made a lot of money: I’d make $150.00 for 15 minutes at a press party for Elizabeth Taylor, things like that, and I’d never made money like that. You would not believe some of the places in New York: money, money, money these people had. I knew this was all happening for a reason . . .

I said my Buddhist prayers and practiced. Pray and practice. Then one Sunday morning I went down to the Pink Tea Cup, a soul food joint in the Village, and Ornette walks in. Now I had met him every once in a while over the years, Julius Hemphill had introduced me to him. I asked him what he was doing and he said he was looking for a drummer. I gave him my number. At the time I was makin’ more money than I had conceived was possible just playing the drums, so I wasn’t even thinking about it: I had a nice place, a telephone with an answering service, I could close up when I wanted to and come out when I wanted to. And he called a day later. Bern Nix was there at the rehearsal, and he’d been chanting also. Ornette had a gig with the Symphony Orchestra in Paris and he wanted to go over and spend a month. So we rehearsed for a month: Ornette; Jamaladeen Tacuma on bass, Bern Nix and Charles Ellerbee on guitars, a Chilean percussion player and myself. We rehearsed all day, every day. They’d already moved into his loft on Prince Street. And we left for Paris. This was the first time I’d been abroad and we were like travelling gypsies. We did everything ourselves. Got our own gigs. A fellow gave us the keys to his studio; all the equipment had been stolen out of it and we could use it for as long as we liked to rehearse. We ended up staying from October to March, this is ’76, ’77. We go out to Italy or wherever and play for awhile. We came back from one trip round Christmas, went into the studio and recorded Dancing In Your Head. We’d already done the pieces with the Orchestra.

Ornette had begun to show me different things: how I was playing according to the rules about playing behind someone and all, and encouraged me to do some writing, and work on my ideas. There was the same freedom to play as with Albert, but in this context you’d know everything you could or would play before you got up to the bandstand. Still improvisational, but ordered — no more guessing games. Already the chanting had allowed me to put my finger on what I wanted to do. I see music all around me. Everything is raining sixteenth and eighth notes all the time. I was becoming aware of all this and finally disciplining myself to sit down and write it out and perfect it. Since I had the keys to the studio, I’d get up early and go down there and work by myself, then the band would come by around 3:00, and we’d work till 9:00, sometimes till midnight. One night the police broke in; we were playing so late, the neighbors had complained. We played everyday, and the people ’round there weren’t used to this sort of thing. And I played all day. Any day I wasn’t there I’d be off to some museum of African art or history or maybe the Louvre, or the Museum of Man out at the Eiffel Tower ’cause that really had the stuff. I learned about the world, about life, and at the same time I was writing out all sorts of rhythms. The experience changed my life, changed what I wanted to play. We came back and played that Avery Fisher concert and then the spot on the “Saturday Night Live” show, which was the last thing I did with that group.

After that I had no place to live in the city, I had to move around again. I chanted and chanted so I could get a place to work on my ideas. And I ran into a saxophone player who was getting ready to leave his studio down on 13th street, which had a full apartment in back. All I had to do was move in, and I did. I wrote music and wrote music and wrote music and learned how to play the flute. I had no responsibilities: from the opening of my eyes to the closing of my eyes it was just music. I’d go out and work a press review or something for a few hundred dollars, but that would be it. I wasn’t working any gigs, didn’t have to. Other than rent, all I needed was 10, 15 dollars a week; I’d become a vegetarian, only eat one meal a day.

I had a loft bed, from which I’d write drum rhythms all over the ceiling. My conscious state was completely dominated by music. I’d never worked that hard, ’cause I could do all the things I’d hear being done by other drummers. But I was going for something else. I’d also been exposed to the Joujouka drummers of Morocco by Ornette. My playing was Ornette’s harmolodic concept from a rhythmic point of view. Ornette is a master saxophonist, melody-writer, magician, teacher. The whole time in Paris was like being in Coleman University. We were totally under his influence. He just paid us so we’d have money to eat and expenses. He was paying the hotel bills and everything. All we had to do was rehearse. We only played concerts when they’d pay him enough money that he thought it was worth it. My concept started there, but it didn’t begin to jell for me until I was alone down on 13th Street.

I realized that to get to the point that I wanted I would have to sacrifice for it. My father had always told me that. You’ve got to sacrifice. I’d been reading a lot of books, and learning how man can attain what he wants if he places himself in a desired state and works to stay there long enough. No one in my neighborhood cared when I played, so I played regardless of time. I’d get up at 3:00 or 5:00 in the morning and start playing the drums. Didn’t bother no one. I’d play into the afternoon, go make myself a cheese sandwich or egg sandwich, go to sleep for a few more hours, wake up and start playing again. After I’d been working on my ideas for over two years, I felt I needed actual group playing to further develop them. So I kept chanting and chanting — I’d told myself that I’d never miss my morning or evening practice — and I hadn’t so I knew if I set a goal for myself I could achieve it. I could send out the vibrations and basically get into the situation I desired.

So one night I’m walking up 7th Avenue, have a dollar in my pocket, figure I’ll go get myself a falafel sandwich. Then something in my mind said: no, don’t get something to eat now, go on up to the Vanguard. I never liked to go the Vanguard ’cause the fellah at the door and I didn’t get along, and I didn’t like havin’ to go to places where I had to pay to get in. On this night a young lady was on the door and I just walked in and went into the kitchen and there was Cecil Taylor drinking champagne out of a bottle. We started talking. He asked me what I do, I say I play drums. He ask me how good are you? And I told him I was the best person on this planet at doing what I do. I told him I play drums the way I play them better than anybody else because nobody plays ’em the way I do: playing drums from rhythm instead of from time, but still swinging. He didn’t know I had played with Ornette or anything: what impressed him was that I told him I was the baddest motherfucker that did what I did. Nobody could play drums like I could. So he said: (in a skeptical tone of voice) O.K., gimme your number, I did. The next day he calls and says come over — with your drums. I go over and he had five flights of stairs to walk up. Whew! We just started playing together and immediately hit it off. From the shit I was working on it was a great situation: I could modulate, I could play rhythms, I could play the numerical sequences I hear and construct myself — and still make it fit within the frame of what he’s doing. I could enhance his thing and still keep the drums and the rhythms as melodic as possible. Making the beat, without the time; like African rhythms, which talk about events and appearances in life, not time.

This is when I realized that the stuff I’d been working on down at the 13th street basement — ’cause I’d been down there two whole years, right? — could really happen. And Cecil liked what I was doing. So we rehearsed every day, from about 2 till 7, just the two of us. I knew he liked what I was doing ’cause friends used to call at certain times of the day. Cecil had a clock on his piano and if it was a particular time he knew someone regularly called at he’d pick up the phone, otherwise he’d let it ring and it might be from upstate or California or something, and Cecil would say “Listen to this” and go around taking all the phones in the apartment off the hook so that the whole space would be like a music chamber. Then he and I would play — maybe for 20 or 30 minutes — for these long distance calls and Cecil would pick up the phone again and say, “Did you hear that?” We had a ball. I have a whole library of cassette tapes of duos with Cecil. I’ve got alternate takes of things that are better than some of the stuff that’s been put out. I’d only heard Cecil play once before I met him, very briefly at the Five Spot. And I hadn’t heard Ornette either when I started playing with him, though we were supposed to be comrades, being from the same home town and all. I hadn’t become conscious of their music until I played with them. And I don’t think I could have handled that if I hadn’t been chanting.

Everyone sees themselves as what they are potentially capable of doing. But I think society blocks all that. There are so many obstacles. People settle for whatever they’re doing, instead of accomplishing whatever they want to do. The practice of chanting allows a person to look at and reflect on what they are and what they may become. By doing it every day, it reinforces this reflection. Since the practice requires action — it’s action because it’s vocal and rhythmical, which are actions themselves — you begin to accumulate more and more of your potential, whatever it is. Maybe you might want to be the best cab driver? Then you focus on all the things that would make people want to ride in your cab. But more than that, it makes you see that each person is an individual jewel . . . if they can take what they have and develop it. I’ve seen a lot of people fall by the wayside, who never got to where I am now ’cause they never stopped to change what they were doing. I realized the environment I was in wasn’t gonna get me to the place I want to go. I’d worked with Ayler and Mingus and Betty Carter but I’d gone back to working bar mitzvahs and parties. I heard many things, but I didn’t have the discipline to make them a reality. I was seeking, but I didn’t know who I was as a person. And that’s what chanting gave me. It broke down all the other characters and gave me me. I could sit in with anybody, anybody, ’cause I could play any kind of way — but not Shannon Jackson’s way. When I was seven years old I told my mother that I was gonna become rich by the time I was 35 but before that time I figured I might as well do everything; and David, I did everything, Believe me. About 99% of the things humans do, I did. And it’s funny, the year before my deadline I began chanting, and became rich by another standard . . .

Once Jackson put it together, he was unmistakable, one of the handful of drummers whose rhythmic identity is so strong that he changes every musician with whom he plays and the way you hear them. More than that, his inventions run so deep that you find yourself rethinking the American rhythmic tradition the way you had to, for example, when Elvin Jones came along.

One afternoon up at Soundscape, the New York City music loft where he practices, Jackson showed me how some of his rhythmic figures were put together, the right hand, left hand and right foot playing three different configurations of the same phrase while the left foot chopped out a steady series of eighth-notes on the high-hat. The result was a fairly funky, unusually spacious second-line beat that reminded me of some of the things Zig Modeliste had done with the Meters, but when Jackson began developing his three lines independently of one another he moved beyond the strictures of a 4/4 bar line into a rhythmic field in which any combination of polyrhythms was possible without any loss of beat.

A number of jazz-rock drummers since Tony Williams have worked out similar coordinations, and studio aces like Steve Gadd have evolved their own specialities; the big difference is the way Jackson has made it feel. It’s not just that he’s made the free-jazz connection or brought a lot of his playing down from the cymbals and back onto the set or even that (like two other Coleman graduates, Eddie Blackwell and Charles Moffett) he is an enthusiastic player of marches. The Jackson effect has more to do with musical essences than with new stylistic wrinkles or technical nuance; like Coleman before him, he has reconnected himself to traditions that modern jazz has either ignored or put to its own more urban uses. If music is a hidden river every artist has to find within himself, Jackson’s findings have led him back from the cluttered island of modernity to the fruitful and murderous fields of America — its folk continuum, trembling wooden churches and football fields, its festivals in Congo Square and, ultimately, Africa. So we are talking about a larger landscape than the city allows and a shared, communal music in which there is no extraneous compulsion to be clever, nor any fear of the simplicity of things as they are. Jackson’s technique may be extraordinary, he may dominate the bands in which he appears, but he does not communicate egocentricity. No matter how astonishing he gets, there is an implicit modesty in his work and a devotion to the music and what might come out of it. He communicates not “look what I can do” but “this is some of the power implicit in rhythm.”

The Jackson discography is small for the moment but impressive. Dancing in Your Head, nice start, is one of the (ahem) great recordings in the history of jazz, and the followup, Body Meta, still available on Artists House, bless ’em, comes in a notch or two lower on the pole but still sets the spirit dancing. The four recordings with Cecil Taylor reveal Jackson as the most stately free-jazz drummer in the history of the idiom, a regal and thundering presence. The two New World issues, Cecil Taylor and 3 Phasis, are colossal enough; the three-record One Too Many Salty Swift and Not Goodby on hat Hut is positively Wagnerian (also has the most obliquely feelthy title of the decade so far). Live in the Black Forest, on PAUSA, does not feature elves but does boast another shuffle and shorter, more easily assimilable pieces. Five stars to them all, or am I in the wrong magazine? Of the two albums with “James” Blood Ulmer, rock fans tends to prefer the Rough Trade import Are You Glad to be in America? (good God yes, especially now) for its raw, funk-punk spunk, but No Wave on Moers Music is my favorite for its unbridled energy and the way Jackson overpowers the already strong band of Ulmer, David Murray and Amin Ali with wave upon wave of rhythm (notice especially the stunning onslaught that opens the album).

Clearly this was one drummer who would wind up leading a band. What’s interesting about the Decoding Society’s debut disc, Eye On You, on About Time records, is not that it threatens to be the Next Big Thing (a designation apparently destined for Ulmer, who has been signed by Columbia for more money than you thought they spent on jazz) but that it looks like the beginning of a real oeuvre. Jackson did all the writing for the date — eleven tunes, since the cuts are kept short — and has effectively extended his penchant for polyrhythm into the sphere of composition. Most of the tunes are written in more than one tempo, often with haunted, Ornettish melodies suspended above faster, more driving rhythms, the orchestration thickly layered, almost sculptural in use of the two saxophone, one violin, two-guitar front line. Jackson is onto something, certainly a portion of Ornette’s harmolodic vision of the divine simultaneity, but also something all Jackson’s own just beginning to find its voice. I know where the rhythms come from, but why should the melodies and textures keep reminding me of China, Southeast Asia, Java, Chad . . . Of course, when you begin to crack the code there’s no telling what connections may turn up and what barriers may come down. The artist with a thousand faces has always enjoyed chatting with himself whenever he can get his instruments working right. Jackson resumes:

Cecil and Ornette are like suns. Not planets, but light for other planets. From Cecil I learned construction, how to really structure my ideas in terms of melody. All that time I’d been working on the rhythms and I had to sit up and block the cliches. I had to de-program all of that and say: BLOOM, you don’t have to go there no more, put in your own things. You don’t have to eat hamburgers every night. BLOOM! BLOOM! You can have shrimp and garlic sauce tonight, you can have lobster — you don’t have to play the same breaks and the same runs no more. You don’t have to play it from time, you can play it from rhythm. And from the basic rhythm you can create a million patterns from that, and keep the whole thing flowing. To me, making Cecil’s music swing means putting a beat there without actually playing it. I want the listener to feel the beat without the beat having to be there physically. The beat is in your body.

As far as be-bop time, I love the way Kenny Clarke and Max Roach and all those cats set it up. But they played it when Charlie Parker was around and this is no longer the Charlie Parker era. It’s been done. So I’m doing something different, playing time by just playing rhythms. If you ever saw the gatherings down South where people would start to dance and you’d see a person start to go in a circle ’cause the spirit hit them, and the moment it hit them might not have been on one, two, three or four. It might happen on five or six, or in between the two. Or the way the hearts beat: da-duh, da duh, da-duh — that kind of pulse can be used in different tempos. I can set up a time, using sixteenth or eighth notes on the sock cymbal, but the pulse don’t have to be with that. The pulse can just come directly from life, or from the music that’s being played. I place different rhythms, different numerical sequences together. And these rhythms aren’t corporal — one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight; the rhythms of your heartbeat; a march rhythm — but rather they’re spiritual, which can vary in their numerical sequence. That variation indicates a different pulse movement. The foundation might be the type of beat you hear in a ritual ceremony in an African village.

I go there in spirit all the time. I’ve been going there, as a matter of fact, quite frequently since 1975. I can very easily go to a dance or a celebration. I often find myself there if I begin to read something and get off in my solitude and — BLOOM — I’m there, and it will take something startling to bring me back.

The Decoding Society is an organization for decoding musical and spiritual messages. Melody itself, like poetry, comes from the spiritual world, and we serve as a medium for it. When I began to write melodies I wondered where they came from, they’d become locked in my head and I couldn’t do anything about them until I wrote them down. That happens when I walk around certain parts of the city and it happens when I play the drums. In the middle of practicing the drums I naturally hear melodies. My whole life force now is directed towards presenting what I hear.

Our society has gone as far as it can possibly go in the direction we’ve been programmed to go in. We’re becoming conscious of the problem. I think people have begun to go into themselves, much more so than even three years ago, to find some spiritual solutions. I feel I’ve been blessed with an opportunity and I’m gonna do all that’s within my power to carry it out. Perhaps it’s just that certain people are given certain keys to carry out certain plans that already exist on a metaphysical plane. Beethoven worked on his ideas, but also on spiritual ideas. I’m trying to structure my life the same way. Sometimes now I wish I had more classical training, because with it, I feel a whole other feeling could be brought to music. I’d like to be able to present my music in totally orchestrated form. Not traditionally, but the way I hear it. I’ve had glimpses of it since my youth: to be able to present the music with such joy and warmth and giving that it will carry over into the person’s regular life. In ten years I’d like to take a group, a small group, to anywhere in the world and play, perhaps supplemented by an orchestra on certain pieces.

Rhythm is the pulse of life, and when you use those rhythms in the right way, in the positive way, it can carry your life into a sphere you might not experience unless you are deep into yoga or are charged with electro-telepathic impulses like a clairvoyant. There are melodies that come directly from the drums that I’d like to play that I don’t get a chance to play: I’ve had to create in terms of producing the concert, getting the musicians together and rehearsing, putting out the flyers, helping organize, advertise, carry the whole thing through . . . All of which doesn’t allow for the leisure of just going and doin’ it. Many times I hit on an idea but I don’t have the resources to carry it out. I found myself the other day taking money I had allocated for food and the telephone bill, and buying music books with it, just so I could keep writing music. I have a lot of music I’m working on right now, but since I don’t have a contract at the moment, I can’t very well ask people to rehearse it all the time. Last year, About Time gave me enough money and a month to do it the way I wanted to do it. David Baker did a fantastic job recording the instruments. This type of music would be fantastic in Digital. You don’t need Digital for disco or be-bop, but it came along at the right time for this music. I was told at CBS there wasn’t enough money for it. But if they want to — “they” being the people who market it or rather create the market for it — they could sell this music. Hell, they can create a market for whatever they want to. They can go down the beach and pick up some rocks and sell ’em on television. “Get Your Pebbles, Get Your Pebbles!!” — put it on TV commercials and you’ll have a run on rocks. That’s the irony of them saying there’s not enough money for something. They can sell anything if they want to.

For a lot of people, my music is music they hear also. I know I’m not the only one hearing this music. If I’m hearing it, there are millions and millions of others hearing it in their own minds. And for those people my work would be a verification that they’re not alone. I want my music to be a joy for people. The problem with it — since it’s called “art” music — is that it doesn’t get the same airplay as “commercial” music. And it’s also not SupClub music, mine is not music to eat dinner to. It’s more of a ritual. It’s not “finger-popping-at work” music, and it’s certainly not “I-love-you-baby” music. But I don’t ever want to be limited, ’cause my responsibility is not limited. Just because I’ve been associated with jazz, doesn’t mean I’m limited to doing this or that. Hell, the first tune on my new record, Sortie, blends an Eastern-Africa feel with an overlay of a march, the kind of spiritual movement at a football game. As a young kid I used to sit behind the band at the football games, and they used to spread such joy when there was a touchdown or someone caught a pass. I go there, to that feeling, when I play. My father used to take me to games when I was very, very small. And I would freeze, my feet would be frozen, almost frostbit by the time the game was over. But I was so into the music: they used to have some phrases everybody would sing, and the drummers, of course, would always be playing. That was where it was.

The second piece on the album, “Nightwhistlers,” is a blues, but it’s like a person walking between buildings in New York and whistling and hearing the reflection of that sound bouncing off the buildings and singing the blues all at the same time. He’s humming the blues and whistling. In other words, coming out of the country and whistling in the kind of echo-chamber we have here in a big city creates that kind of thing. So I wrote it all down, and played it the way people feel in an environment I used to be a part of — where people worked all week picking cotton and corn, and worked in wheat fields and watermelon patches — when they’d get together, starting Saturday afternoon puttin’ all the ice on the beer, and then after the sun went down they’d get together and start dancin’. And I used the kind of beat they’d dance to, it would be goin’ up and down at the same time, it would be like a volleyball beat. In “Apache Love Cry” I interlocked two melodies; one is the result of being at a West Indian Festival over in Brooklyn, the other comes out of a Bowery bar where I used to stop and get a beer after everything closed. One guitar player plays the one —which is lively, happy, full of carnival gaiety — while the other guitarist plays the depths of despair. And “Apache” as a symbol for what this country is all about. They represent the true spirit of what this country was and still is; no matter how many bulldozers and buildings we put up you can still get the spirit of this country if you go check them out. “Shaman” is a tribute to Max Roach, who’s a shaman. The first part, which has an African influence — and by that I mean a Southern Blues beat played in 6/5 — gives way to a drum solo and then a waltz-type thing. “Eastern Voices, Western Dreams” came through chanting. While I was chanting an Oriental voice would speak to me and this is what the voice said. I just got up and wrote down specifically what the voice said. But I come from the West. I live in a western society. I think the two of them are beautiful and will come together in this country, which of course would only bring it back to where it was at first — the American Indians already had that kind of spirit.

I do a lot of writing now from the piano ’cause I have one at my disposal, but everything on the record was written on the flute, or from the drums. For instance, “Dancers of Joy” was written on the drums. When I ride the bus and the subways I see a lot of people coming from dance classes. My thinking and feeling about that is, well, people want to dance the way they feel, not the way they’re programmed to dance. If someone comes to you and says, “Here David, here’s 50 $1000 bills, no stigmas attached.” You might not jump up and down right then, but when you get out the door and get by yourself, you start dancin’ for joy. Pure delight. Gurdjieff tried to use — in fact, did use —dance in his teachings, right? When people dance another element comes in, the thing that has to do with pulse, because when you really dance and let the mind-body-spirit be itself then one’s mental-logic-reasoning system is cut off and one goes into what the ritual of the dance can bring into a person, another dimension of the self. Whirling dervishes, right? I took the title from a Buddhist phrase, which talked about dancers of joy 3,000 years ago.

“Theme For A Prince” has two melodies. I wrote it in Europe and America. The first I wrote on top of a hill in the middle of a cemetery in France. It was after midnight, I didn’t have no money, and some Algerian dude hipped me to this place. Some famous French painter, Monet or somebody, painted up there. On top of the hill there’s a bar with money from all over the world, every country that has paper money has a bill pasted to the top of the ceiling. And these people were in there enjoying themselves. Really enjoying themselves. It was like: to hell with the world, the world didn’t even matter. The title was for the person I wanted to play it, that’s all.

Ronald Shannon Jackson’s Drums

I have a standard set, a set that was self-designed. I use Sonor drums and Paiste cymbals. The cymbals are the new dark sound cymbals, New Creations. Very much like the old K. Zildjians, which were handpressed in Turkey. I use two 15″ hi-hats, an 18″ Chinese splash, a 21″ flat ride, an 18″ dark ride (as a crash), and a 16″ crash — 2000 series, and also 10″ 2000 series interchangeably with a small gong-like cymbal which was Tchaikovsky’s which his son gave me. The drums are Sonor. Basically what I wanted was a heavier sound from the mounted tom-toms, a deeper, richer, lower sound from my left hand. One of the things I had in mind was piano design, where you come from the lower registers on up. I play more drums than cymbals, because I’m more interested in getting into the depths of drums in music — since to me, a lot of melody itself comes from rhythm.

I use two different size sticks because the two hands are different. The two hands and the two feet are not evenly matched, though I’ve used a: matched-grip for the past 7 or 8 years. So in the right hand, I use a stick with some kind of round beater, to get the proper effect on both drum and cymbal, but of a lighter weight than the one for my left, since my right hand will always be a little stronger.

Ronald Shannon Jackson:

''Rhythm Is Life Itself"

Interview: April 10, 1982

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

Interviewed by Kofi NatambuEclipse Jazz Concert

The Power Center

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan

This interview appears in Solid Ground: A New World Journal

Volume 2, Number 2-3, Winter/Spring 1984

Kofi Natambu (editor)

Solid Ground: We're sitting with Mr. Ronald Shannon Jackson, drummer-composer and leader of the Decoding Society, an outstanding black creative music ensemble. Last night they appeared in concert at the University of Michigan as part of the Eclipse Jazz Series. We're going to be talking with Mr. Jackson about his philosophy of music and its relationship to what he·s been involved in over the past decade or so in this part of the world. I'd like to take this opportunity to welcome you Mr. Jackson.

Ronald: Thank you very much Kofi. The music I play, and the group I represent, is the beginning, the seed. the nucleus of the turning point of our music throughout the land as it has moved before in waves, as our people assimilated the western instruments in New Orleans and created this music in terms of furthering our development as a people in this music. By that I mean we are simply carrying on a tradition that was set in New Orleans and many other places. A tradition that was brought to a very high peak of perfection by Charlie Parker. Dizzy Gillespie. Max Roach, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, etc. who built on the foundation of Fletcher Henderson, and other great musicians in the "Swing Era" on up to Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Now we're at the point where we have electricity influencing not only music, but life. And since life is music and music is life, it's just the next step in the music. Our group. the Decoding Society, has the good fortune of being a leader in this, so the young musicians in Detroit. and throughout the United States, will be able to really harness their own musical spirit and energy and bring forth what they have to give. It would be a sad thing if we didn't allow our youth to have the necessary philosophy. or understanding the history of oursefves as a people. We have the responsibility of carrying that on. I think that what we're doing will give them that impetus.

As you know the media has flooded our homes and our people's mind (and especially our younger peoples minds) with a music that is for dancing and only allowed for dancing or made so that everyone can dance to it. Where you go and you can dance the same way every night. When as a people we oome from a background where you had dances for each occasion. Not just one steady rock or disco beat. Now we already have that influence in our homes and in our youngsters. But we can use that same electrical pulse to bring forth our true creativity, which is what we're striving to do. It's just about finding itself, its own roots, and really manifesting itself totally, throughout the whole world. As our art form "jazz" has done.

We're given the dilemma of having the fortune and misfortune at the same time. We are originators and creators of this music. but we're not the benefactors of this fruit. In other words we plow the field, we plant the seeds, we do the nurturing, we even pick the crops. But we don't get to eat the fruit. Unfortunately, that's going to continue. But we as a people have to continue also. We have to realizethat we are given a responsibility to carry on the aspect of creativity in music and man throughout the Universe at this particular time. Nothing is born from the silver spoon. It has to come from the depths of our lives and the suffering that we're going through. And that suffering is not eliminted by finncial stability. To us, that's only a pathway to bring forth more of the deep, unfathomable crealivee force we do possess.

S.G.:

Throughout the ages, music has been used as a philosophical and

spiritual way of acquiring a broader consciousness of one self in

relation to the environment. In the context of the Decoding Society, how

would you describe what the purpose or the function ol the Decoding

Society is in terms of that particular point of view?

Ronald: Like I stated before, civilization keeps ooming to certain mountain peaks. Every seven years Man changes, every several decades or centuries or so, civilization changes. In this country, at this time, the winds of change are very present. And that wind blows, and those of us who are given the responsibility of carrying on the tradition of our music have to realize this and make it manifast so that when we come to the point of understanding not only our own personal relationship with the environment and society, but our relationship with the Universe as a whole then we will feel that. The Decoding Society is a verification of that.

In other words, the Decoding Society is saying that joy, that warmth, that inner enlightenment that one sees is a glimpse of the infinite that is there in all our lives. This is present all over. In the same way that a flower can be used to show a horn owl some of the laws of nature, the Decoding Society is a group that shows that this manifestation has appeared now. And it's just the beginning of it. It's the beginning of bringing together spiritual forces. Sure, music has been used in a spiritual, philosophical vein throughout the ages because it is the highest of the art forms. That's because it's sound vibrations. Sound. Music is Sound, and sound creates the whole Universe. We're sending out sound signals now into the infinite or not so much infinite but distance. Into the distant planets and we're listening for echoes and the return of those sound waves to our planet.

It's

the same thing with Man. We send out signals, you and I. We all have

fibers that emanate from our center and although we can't see that, it's

the same as we can't see our eyebrows, it is still there. It emanates

from me to you, and emanates from you to other people. Which is saying

we're all connected and when we send our the wrong type of vibes from

those fibers, then we see the bad, or wrong type of effect. When we send

out the right type of vibes from these fibers that are emanating from

us, then we see that beautiful effect and it's embodying a law of cause

and effect. Music is the highest cause.

Personally I practice Buddhism. At one time Buddhism used music to teach people about the awareness in themselves. Because music has, or is the element that will make one look into themselves, as opposed to outside ourselves. So the Decoding Society is a vessel of the manifest realistic entity embodying the forces of music to show that unity exists in Humankind on a spiritual level.

S.G.: When I listen to the music of the Decoding Society, I get very distinct feelings. Very distinct impressions ... I can actually feel the unity between melody and what people call rhythm. To the extent that you've been involved as a composer of music and as a "drummer," how does the element of rhythm play a part in the music in terms of its energy?

Ronald: Rhythm is—as you know—life itself. Rhythm is Life and Life is Rhythm. Everything we do is rhythm. Our heartbeat ls rhythm. Our ancesters used rhythm as a way of communicating since they all didn't exist at that time. Our International Telegraph and Telephone or whatever, and we still use it. Some of our relatives still use rhythm to talk with.

Now in the Decoding Society, I use rhythm and melody to speak the way we've normally been speaking throughout the ages. You see when people said "Jazz has died, Jazz is dead" they were saying something that is not so. You know people at one time were saying that "Jazz is dying." Well we all know that is not true. What happened is that Jazz is such a universal and international force that ways were devised to exploit it and make it more "palatable" to people in terms of putting it behind TV and using it as background music throughout the world. In order to make it so it wouldn't affect you, they took the rhythm out. And that's what you're talking about. You know, that is my personal goal: To see to it that Rhythm is put back in our Music. We can talk, we communicate, we dance from rhythms and we don't, too. We are not just a disco dancing people. All of us who listen or will read what I'm saying will understand that we dance inside in millions of ways. We jump for joy, we have movements for sadness, we have dances for weddings, we have dances for births. We have dances for the celebration of just our pure being and it's not a disco beat. It is the rhythm of our life. That's what I'm doing. I'm using rhythm itself.

Rhythm is the element that we all have, and if you listen to a dog barking and the dog barks in an angry rhythm, you immediately understand it. Same way as you can listen to the flutter of the wings of a bird and feel the melodiousness behind the rhythmic activity. We all have this in us. As a kid I remember being in the kitchen and my grandmother would be humming some hymn. You know our older women were modest in those days. They had on these long dresses and long aprons. They'd grab the apron and pull it up. Not real high or anything sexually provocative, but they would pull it up so they could get their legs moving and really get in the rhythm of what they were doing. And that's there. I know that's in all of us, our people, and that's what I want people to really understand. We're not alone, you know. It's in all of us. That is the rhythmic aspect.

Melody

comes out of rhythm. You can be playing a rhythm, and once you play it

to a certain state, it begins to manifest its own melody. Life appears.

It's not something that's mystic or mysterious, it's just there and

rhythm unlocks it. Rhythm is the key that says: "Yeah, check this out."

It's the same as the air we're breathing and the atoms that surround us,

you know. We don't see it but it's there. Rhythm is there the same way.

A heartbeat. If your heartbeat misses a rhythm, you know that ... ask

anyone who had a heart attack.

S.G.:

That's crystal clear. You've obviously been playing a long time. In the

development of your own life, how did you begin to formulate some of

the ideas that you've expressed in terms of your playing? Could you

describe that process?

Ronald:

Well, actually Kofi it's a process that began before I was born this

time. I say that because I knew that I was going to be playing drums by

the time I was four years old. And I'd never played any. When I first

saw a drumset I was in the basement of a church in Houston, Texas. My

mother had taken me to Houston, and it was some kind of kiddie

program-the kids were there and I was walking through in a line and this

drum set was sitting there on this podium and I just stopped. I let

everyone else go. I was just mesmerized at that point. Although there

was nobody on the bandstand I could see all the joy in music with the

cats playing. I could see this, so I knew that that's what I was

supposed to be doing.