SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2017

VOLUME FOUR NUMBER THREE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JAZZMEIA HORN

(August 12-18)

ROY HAYNES

(August 19-25)

MCCOY TYNER

(August 26-September 1)

AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE

(September 2-8)

AARON DIEHL

(September 9-15)

CECILE MCLORIN SALVANT

(September 16-22)

REGGIE WORKMAN

(September 23-29)

ANDREW CYRILLE

(September 30-October 6)

BARRY HARRIS

(October 7-13)

MARQUIS HILL

(October 14-20)

HERBIE NICHOLS

(October 21-27)

GREG OSBY

(October 28-November 3)

Herbie Nichols

(1919-1963)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

One of jazz's most tragically overlooked geniuses, Herbie Nichols was a highly original piano stylist and a composer of tremendous imagination and eclecticism. He wasn't known widely enough to exert much influence in either department, but his music eventually attracted a rabid cult following, though not quite the wide exposure it deserved.

Nichols was born January 3, 1919, in New York and began playing piano at age nine, later studying at C.C.N.Y. After serving in World War II, Nichols played with a number of different groups and was in on the ground floor of the bebop scene. However, to pay the bills he later focused on Dixieland ensembles; his own music -- a blend of Dixieland, swing, West Indian folk, Monk-like angularity, European classical harmonies via Satie and Bartók, and unorthodox structures -- was simply too unclassifiable and complex to make much sense to jazz audiences of the time. Mary Lou Williams was the first to record a Nichols composition -- "Stennell," retitled "Opus Z," in 1951; yet aside from the song he wrote for Billie Holiday, "Lady Sings the Blues," none of Nichols' work got enough attention to really catch on.

He signed with Blue Note and recorded three brilliant piano trio albums from 1955-1956, adding another one for Bethlehem in late 1957. Nicholslanguished in obscurity after those sessions, though; sadly, just when he was beginning to find a following among several of the new thing's adventurous, up-and-coming stars, he was stricken with leukemia and died on April 12, 1963. In the years that followed, Nichols became a favorite composer in avant-garde circles, with tributes to his sorely neglected legacy coming from artists like Misha Mengelberg and Roswell Rudd. He also inspired a repertory group, called the Herbie Nichols Project, and most of his recordings were reissued on CD.

In his lifetime Nichols only put out four records under his own name, three for Blue Note and one for the even smaller Bethlehem label, this time in the company of Dannie Richmond, Charles Mingus's drummer of choice. This date offers listeners evidence of his way with a standard song or two.

Ironically, he wrote an article about Thelonious Monk for the African American magazine Music Dial in 1946 that may have been instrumental in bringing Monk to the attention of producer Alfred Lion at Blue Note. Yet Nichols himself, despite sending frequent tapes to Lion, was not recorded by Blue Note until eight years after the company signed Monk in 1947.

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

There is a little dark bar I like to go to where people know things. We wile away the nights in friendly arguments. Which phase of Bergman’s career gave us the best movies, where in Mexico is Ambrose Bierce living and who are the all time greatest jazz pianists? What is interesting is that now, one of the main ingredients in determining "the best" seems to be their level of exposure.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Herbie-Nichols

Herbie Nichols, byname of Herbert Horatio Nichols (born Jan. 3, 1919, New York, N.Y., U.S.—died April 12, 1963, New York City), African-American jazz pianist and composer whose advanced bop-era concepts of rhythm, harmony, and form predicted aspects of free jazz.

He composed about 170 songs, and in 1955–57 he recorded the four albums upon which his reputation is largely based. After his death, from leukemia, most of his unrecorded compositions were destroyed in an apartment flood; however, unissued recordings by Nichols, including eight “new” songs, were discovered and released in the 1980s.

As a pianist Nichols was at his best interpreting his own compositions; he also was his own best interpreter. Like early jazz composers, Nichols created portraits (“117th Street,” “Dance Line”) and dramas (“Love, Gloom, Cash, Love,” “The Spinning Song”) in his themes. The harmonic foundations of his songs were original and often daring; his structures frequently extended song form far beyond the customary four strain, 32 measure limits. His solos, which were variations on his themes, incorporated rhythmic displacements and reharmonizations and created open spaces in his melodic lines that inspired interplay with his drummers. The generous strain of humour in his work belied the difficulties he experienced in his career.

Renaissance man: Mark Miller's recent biography places Nichols in the cultural light of his Harlem upbringing.

When Herbie Nichols died in 1963 at the age of 44, he was unknown to all but a few young jazz artists and a handful of critics and fans who’d happened to hear the LPs he recorded for Blue Note in the mid-1950s. Those who did know him nearly always spoke of a gentle, quiet, intellectually and creatively vital person. In the mid-1970s, his recordings began to circulate again, his compositions re-recorded by other jazz artists. After his death, Nichols’ music won the respect, love and acclaim that was missing during his lifetime.

What world did Nichols himself come from? In his recent book Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life, jazz writer Mark Miller makes a compelling case for the pianist as a product of the Harlem Renaissance. Miller joins us on Night Lights this week for a look at Nichols’ life and music, featuring several of the pianist’s key Blue Note recordings, as well as a side from his rarely-heard debut as a leader, and a solo from one of his few recorded Dixieland gigs that Nichols often had to take for economic survival.

The book Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life is available through both The Mercury Press and Amazon.

UPDATE: Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life is now available through Teksteditions.

UPDATE: also check out Jason Crane’s great new interview with Mark Miller on The Jazz Session.

Johnson, David Brent; Miller, Mark (5 April 2010). "Night Lights: Herbie Nichols' Third World". Indiana Public Media. WFIU Public Radio. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

Spellman, A.B. (1985). Four Lives in the Bebop Business (1 ed.). New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 0879100427.

Miller, Mark (2009). Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist's Life. Toronto: Mercury Press Publishers. ISBN 978-1-551-28146-9.

Kelsey, Chris. "Roswell Rudd". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

Layne, Joslyn. "Misha Mengelberg". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

Herbie Nichols

Herbie Nichols is a perennially neglected jazz pianist and composer. He recorded less than half of his 170 compositions on three classic trio albums for Blue Note and one for Bethlehem before dying of leukemia at the age of 43 in 1963.

He is often compared to Thelonious Monk, and his piano playing and compositions certainly do have some of the harmonic angularity people associate with Monk. But he had a very distinctive sound of his own, more melancholy and, for lack of a better word, poetic than Monk in many ways. In fact, Nichols was something of a poet, as the titles to his tunes suggest. And he was fully Monk's equal in the quality and individuality of his tunes. He is held in high critical esteem within jazz, although his tunes are still not widely recorded. Outside of jazz circles, the only tune of his anyone is likely to know is “The Lady Sings the Blues,” which Billie Holiday set lyrics to and adopted for the title of her autobiography.

Nichols was born in New York in 1919 and died there forty-four years later. In the course of his brief life he was for a time an associate of Monk's, though to consequently call his music Monk-like is to do it a grave disservice. He played with amongst others Milt Larkin and Rex Stewart out of economic necessity. His own harmonically extraordinary music was no small distance removed from theirs.

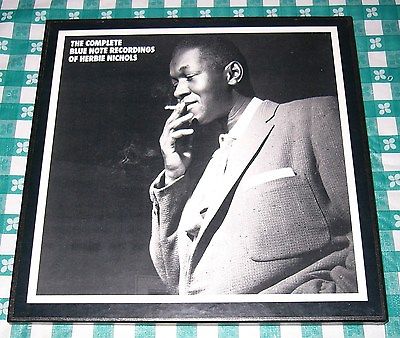

This is not to imply however that his music amounted merely to an academic exercise. As it was to be with Andrew Hill some years later, Blue Note records afforded Nichols an unprecedented opportunity to record his own music, and he made full use of it, as the three CD set of “The Complete Blue Note Recordings” shows. The music found here comes exclusively from his pen and it was recorded in a bout of concentrated recording activity between May 6, 1955, and April 19, 1956. It was all performed in the trio setting, and throughout Nichols plays with a variety of virtuosity that couldn't be included in any jazz curriculum.

As a player he has capable not only of dark lyricism but also of writing melodies so harmonically adventurous that they can make the listener laugh out loud over their audacity. Furthermore, his music was in a rhythmic league of its own, and Nichols was indeed fortunate in the drummers he worked with in his brief recording career these Blue Note sides find him in the company of both Art Blakey and Max Roach.

In his lifetime Nichols only put out four records under his own name, three for Blue Note and one for the even smaller Bethlehem label, this time in the company of Dannie Richmond, Charles Mingus's drummer of choice. This date offers listeners evidence of his way with a standard song or two.

The music of Herbie Nichols is undoubtedly an acquired taste. Whilst he plowed an individual furrow he did so with clarity of purpose and vision. The irony of it is that if he were alive today he would probably have to work outside of music in order to make a living. The passing of time has moved several steps away from the recording and marketing of music as idiosyncratic as his. As such, his life was and is a stark example of the gulf between art and commerce.

Source: Nic Jones

ALL THAT JAZZ

A Too-Brief Glimpse of Herbie Nichols

A Too-Brief Glimpse of Herbie Nichols

by DON HECKMAN | SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

Herbie Nichols is one of the forgotten heroes of jazz.

Thirty-four years after his death in 1963, he continues to be relatively unknown, even to many serious jazz fans. Sadly, the lack of recognition simply continues the circumstances of his brief life (he was 44 when he died of leukemia), since Nichols--despite a prodigious talent as a pianist and composer--recorded rarely and was obliged to spend a good part of his life accompanying shows and playing in Dixieland bands.

Ironically, he wrote an article about Thelonious Monk for the African American magazine Music Dial in 1946 that may have been instrumental in bringing Monk to the attention of producer Alfred Lion at Blue Note. Yet Nichols himself, despite sending frequent tapes to Lion, was not recorded by Blue Note until eight years after the company signed Monk in 1947.

And when he did get around to recording, his career was painfully short. In five trio sessions for Blue Note, recorded in 1955-56, he produced material intended for release on five 10-inch LPs. All of those recordings, as well as extensive alternate takes, have now been released in a three-CD collection, "Herbie Nichols: The Complete Blue Note Recordings."

What emerges is a too-brief portrait of a genuinely original talent. Nichols' playing bears references to Monk and to Art Tatum, even a few traces of Teddy Wilson and Bud Powell. And one wonders if Phineas Newborn Jr. was familiar with Nichols, given some of the similarities in their style. But mostly Nichols simply sounds like a unique player--so unique that it's hard to understand why he wasn't recorded more often.

His tunes are solid melodies, often moving in unlikely harmonic directions, and--like Monk's music--intriguing enough and filled with sufficient musical resources to attract the attention of other players. Unfortunately, the music in this compilation, attractive as it is, represents a small portion of Nichols' 170 compositions.

Still, it's all that remains of his work as a leader (he recorded on rare occasion as a backup player), and Blue Note should be commended for making it available. (Mosaic issued the same material a few years ago in a limited-edition, five-LP boxed set.)

A.B. Spellman's book "Black Music: Four Lives" (Schocken Books) includes an extensive interview with Nichols, speaking shortly before his death. "I'm not making $60 a week," Nichols told Spellman. "I'm trying to sell some copyrights, but if you don't have somebody behind you in this country, you die."

Nichols' talent, his creativity, and his intelligent observations about the music business are the stuff of an important jazz voice--one that deserves to be rescued from its current anonymity.

On the Shelves: There is plenty of interesting reading matter available for holiday gift giving for both the dedicated and the casual jazz fan. For example, no less than three Thelonious Monk books arrived in the legendary jazzman's 80th anniversary year.

"Thelonious Monk: His Life and Music," by Thomas Fitterling (Berkeley Hills Books), first published in Europe in 1987 and now available in a new translation, takes a look at Monk from three perspectives: his piano and composition techniques and his discography.

"Straight, No Chaser, The Life and Genius of Thelonious Monk," by Leslie Gourse (Schirmer Books), is written in the author's characteristically detailed style, filled with anecdotal material, and based upon extensive interviews with friends and family.

"Monk," by Laurent de Wilde (Marlowe & Company), is particularly intriguing because it was written by a first-rate jazz pianist. De Wilde's observations are all highly personal, his viewpoint that of a musician attempting to find insights and understanding in the life of a much-admired influence.

Miles Davis fans will find a variety of diverse views of the Prince of Darkness in a series of essays in "A Miles Davis Reader," edited by Bill Kirchner (Smithsonian).

Another book by a practicing musician, "What Jazz Is," by pianist Jonny King (Walker), informatively addresses questions listeners always ask about jazz--"Where's the melody?" "What does the rhythm section do?," etc.

And budding guitarists who have worn out their blues licks will enjoy the quick entree into jazz phrases provided by guitarist Sid Jacobs' "Complete Book of Jazz Guitar Lines and Phrases" (Mel Bay Publications).

Mark Miller’s Herbie Nichols: A Review

September 23rd, 2010

Jazz Journalists Association

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

by Mark Miller

Mercury Press, Toronto, 2009; 224 pp.; $19.95 paperback

The jazz world is filled with musicians who have not received the recognition they deserve. But after reading Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life by veteran journalist Mark Miller, the obscurity surrounding this pianist seems particularly tragic.

Nichols had his heart set on being a classical pianist, but because a classical career was impossible for a young African-American in the 1930s, he switched to jazz. “My earliest ambitions were to become a Prokofiev,” Miller quotes him as saying. “When I learned that I would be unable to obtain formal conservatory training I decided to become an Ellington and to enter the fascinating field of jazz.”

In the author’s notes and acknowledgements, Miller quotes one of Nichols’ admirers, pianist Frank Kimbrough: “I can’t imagine anyone coming up with enough information for a book [on Nichols].” Miller is to be commended for completing that task. However, one wonders how many jazz followers know enough about Nichols to be interested in learning more. Nichols clearly had the talent to be successful, but he had a somewhat distant personality and also seemed to be haunted by the success of his peer, Thelonious Monk.

Nichols often lamented his separation from the classical world and was critical of the attitude of other jazz musicians toward it. According to Miller, “He acknowledged the tension between classical and jazz musicians, a tension that he clearly still felt in himself, given his early aspirations in the classical field and his undying respect for its ideals and innovations.” Writing in the Harlem magazine, Rhythm, Nichols said, “The funniest thing to me is the complete realization that our florid 1946 jazzmen are austere creatures who actually sneer at the classicists. It is all an emotional mumble jumble wherein we fools should be big enough to view everything objectively.”

Nichols’s alienation from many of his contemporaries is typified in comments he made to the poet George Moorse: “I used to sit in a lot in the late thirties and forties with the guys who later became known as the bopsters. I guess my playing was even too far out for them. And most of them thought I couldn’t say anything. Of course, in those days I must have looked like a professor, with a starched white shirt. I used to talk about poetry almost as much as I talked about music.”

The vocalist Sheila Jordan recalled that Nichols would “sit in a corner. It wasn’t that he was standoffish, I think he was shy – or maybe his mind was elsewhere…. He was very quiet, stayed to himself, went and stood outside of the club, smoked his cigarets [sic]. I don’t ever remember him even talking to anybody.”

Then there were the comparisons with Monk, who did achieve the widespread recognition that alluded Nichols. According to Miller, both were “similarly influenced by Ellington,” but Monk by 1944 was “already a force among his contemporaries for the formative role that he had played at Minton’s [Playhouse] in shaping the conventions of bebop.” Critic Lawrence Gushee, writing about Nichols’s 1957 Bethlehem album Love Gloom Cash Love in The American Record Guide, said there were “pretty obvious” reasons for comparing Nichols and Monk but concluded that Nichols “is far from the champion that Monk is.” On the other hand, Alfred Lion, co-owner of Blue Note Records, told producer Michael Cuscuna in 1985 that when he first heard Nichols, “I hadn’t been so excited about someone since I first heard Monk.”

Miller’s book is at its best when describing Nichols’s live performances and his willingness, coupled with practical necessity, to play at all kinds of gigs, giving his all even when the style wasn’t his preference. The book only bogs down when Miller goes into unnecessary detail about each selection of Nichols’ recordings.

Dan Morgenstern expressed the tragedy of Herbie Nichols most succinctly in a quote at the beginning of chapter five, which covers the period from 1958-1961. “Herb Nichols,” wrote Morgenstern in the January 1959 issue of Jazz Journal, “has, of course, recorded with Rex Stewart, and with his own trio on two ten-inch Blue Note LPs and on the defunct Hi-Lo label, but all of this is out of circulation, and so is Herb.”

About the Author:

Sanford Josephson is the author of Jazz Notes: Interviews Across the Generations (Praeger/ABC-Clio), and currently writes the “Big Band in the Sky” obituary section for Jersey Jazz, the magazine of the New Jersey Jazz Society.

Bookshelf

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life by Mark Miller

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

by Mark Miller

The Mercury Press

224 pages, photos; $19.95

For all his brilliance as a pianist, composer and critic, Herbie Nichols spent his life in obscurity. Toronto-based jazz historian Mark Miller has produced an incisive and heartbreaking portrait of a deeply compelling musician. Today, Nichol’s few recordings are unavailable, and his writings remain uncollected and unpublished. But his song Lady Sings the Blues, written with Billie Holiday, has attained iconic status, and many of his other compositions, like House Party Starting, 2300 Skidoo, The Third World, and Love, Gloom, Cash, Love have become standards.

Miller has combed through the available documents on Nichols, which include autobiographical notes Nichols prepared for the day (which never came) when he would need material for publicity purposes. Miller has talked to musicians still alive who knew him, like trombonist Roswell Rudd, who along with pianist Frank Kimbrough has spearheaded a project to track down and record many of Nichols’ previously unknown compositions. By placing Nichols’music in the context of his relationship to what was happening musically around him, Miller shows how imaginative, original and advanced it was.

Miller portrays a gentle, self-effacing, introspective, and – understandably – fatalistic man. But while he constructs a coherent narrative for Nichols’ life, Nichols himself keeps slipping in and out of the story. It’s as though Nichols is as baffled by the events of his own life as everyone else.

Why was Nichols so utterly neglected? He told A.B Spellman, in the first, and up to now only profile of him in Four Lives in the Bebop Business, “It seems like you’ve got to be an Uncle Tom or a drug addict to make it in jazz, and I’m not either one.” He was rarely able to get jobs or recordings where he could play his own music in his own style. In 1956 Nichols had told the poet George Moorse, “Sometimes I may seem low...but really, I’m laughing like hell inside.” Yet, as pianist Don Coates told Miller, shortly before Nichols’ early death from leukemia in 1963 he said, “Music is a curse.” Miller has succeeded in rediscovering a visionary musical voice, and convincing us that it demands to be heard.

- 29.11.-0001

The Complete Blue Note Recordings by Herbie Nichols

There is a little dark bar I like to go to where people know things. We wile away the nights in friendly arguments. Which phase of Bergman’s career gave us the best movies, where in Mexico is Ambrose Bierce living and who are the all time greatest jazz pianists? What is interesting is that now, one of the main ingredients in determining "the best" seems to be their level of exposure.

Perhaps the greatest accolade and curse an artist can be given is to be termed "an artist's artist." The label which seems to resign them to obscurity except among the most hard core aficionados. This has largely been Herbie Nichols’ fate.

Herbie Nichols (1919-1963) started formally studying piano at the age of nine. Early on he mainly played in Dixieland bands, a start akin to two other fonts of progressive improvisation, Steve Lacy and Roswell Rudd. These two would also later prove to be two of the most talented interpreters of his music. For all of them, these early Dixieland years were more of a financial necessity than an aesthetic choice.

Herbie also played in The Savoy Sultans while mingling with the early progenitors of Bop. Aside from a friendship with Thelonious Monk, he did not get much joy out of the then fertile 52nd Street scene. During this time there was still a misplaced nobility associated with jazz musicians and addiction(s). Herbie, ever the tea-totaler was shunned. Another off-putting aspect of this quite young man was his intellect. Herbie played chess, wrote and appreciated poetry. He also wrote insightful jazz articles. Well before jazz aficionados gleaned onto him, he wrote an article on Monk for Dial Magazine.

In 1941 he was drafted into the army. It would be another two years before he was demobilized, partially eating up the time by writing poetry and lyrics.

Upon his discharge, he found himself back in New York where he had to play piano for burlesques in Greenwich Village to make rent.

Pianist Mary Lou Williams was the first to record one of Herbie’s songs (1951) "Stennell," which was re-titled "Opus Z."

Starting in 1947 he would send his music to Blue Note’s Alfred Lion. For various reasons it would take nine more years before Herbie would be signed. Herbie was one of three all time great pianist-composers signed by Alfred Lion (Thelonious Monk and Andrew Hill being the other two).

Things seemed to be looking up for Herbie. Also around this time (1956) Billy Holiday fell hard for his piece "Lady Sings the Blues" writing lyrics for it and making it her own to the point of using it for the name of her autobiography, too. The piece, originally titled "Serenade" has become an important part of the jazz lexicon and a totem of longing and heartache.

Herbie wrote over 170 songs. After his death much of his writing which was then stored at his father’s house was lost in a flood. We owe much of our knowledge of his pieces to Herbie himself, he had always been diligent about supplying the library of congress with his scores.

He would record three albums for Blue Note Records and one for Bethlehem. This would be followed by five years of studio inactivity, when jazz was in a constant frenzied state of flux. At the end of this period Herbie would die way too early of leukemia. A factor in Herbie’s long standing obscurity would seem to be lack of recorded sideman appearances. He did share the stage with some established heavy weights, but unlike another "obscure" pianist who also recorded for Blue Note, Elmo Hope, there is not sideman documentation on record for fans to hunt down or the casual listener to come across. An artistic ascension established without wax pedigree save for his own recordings.

The Blue Note boxed set collects all of his Blue Note output. It comprises thirty songs with eighteen, previously unreleased alternate tracks. Unlike some alternate tracks to be found on other musical omnibus, these alternate tracks will appeal to more than just the jazz completionists. Often it is subjective which is the "better" version of a track. The liner notes make mention that it sometimes took lengthy discussions to decide.

The packaging is aesthetically pleasing and avoids some of the more impractical concepts of other boxed sets. A cardboard slip case houses three CDs and a booklet. The tracks and musician information are listed on back of the slipcase and in the booklet itself. The CDs each go in a slim case which contains a different image on each by Francis Wolf, the man responsible for some of jazz’s most iconic images. The booklet contains the album’s original liner notes by Herbie himself and an informative essay by Frank Kimbrough and Ben Allison; the founders of The Herbie Nichols Project which is a group seeking to further appreciation of Herbie’s work through recordings and concerts.

The sound is pristine, the entire collection having been remastered by Michael Cuscuna, a man behind many important reissues over the years and a man who has made the remaster an art unto itself. The Super Bit Mapping process was used which allows the music to retain its ambient warmth while combining it with digital clarity.

From the start, Herbie’s intellect and formal training had given him an appreciation for 20th century composers. It is not too much of a stretch to see similarities between some of Herbie’s oeuvre and turn of the century French pianist/composer Erik Satie, whose deceptively simple melodies and their daydream inducing properties (Gymopedies, Gnossiennes) Herbie’s own compositions sometimes mirrors.

Also in the classical tradition, much of Herbie’s music was Programme music, music which like some of Debussy’s and Liszt’s was inspired by and describes a specific thing. Song titles were given much thought and an important part of the overall creative process for Herbie.

Although a contemporary of both Monk and Bud Powell, Herbie has often been referred to as a "disciple of.... " His playing does have some percussive aspects to it, the earliest most visible proponent of such technique being Bud Powell. I have found though, that one of the marvels of Herbie’s playing is his ability often contained within one piece to change tempos, touch and the actual cadence of his pianos tone. While there is definite joy to be had listening to the percussive school of playing, after awhile a formula is detected in a song’s structure. This never occurs with Herbie’s playing and pieces.

His friend Monk is a noticeable influence but no more so than the jagged lines to be found in the rhythmic works of Hungarian composer Bela Bartok who Herbie also greatly enjoyed.

Too often it is the easy thing to call any pianist/composer with odd time signatures or jagged note/chord clusters "Monk-like". Cecil Taylor and Andrew Hill also frequently get this adjective. What the three have in common is that they represent separate artistic evolutions stemming from the same instrument and to some extent the same inspiration of Monk. It is a new modern classical. Jazz is sometimes referred to as American classical, but these three provide a more literal example. To really listen to their music is to realize they are from jazz but not of jazz.

It is not a case of "better than" but of the three Herbie is the more accessible style wise. While he remained his own man, he drew from diverse sources such as the previously mentioned classical idiom. There was of course the vernacular of jazz in many forms to be found too in both his playing and composing, elements of bop, stride and things yet to come, but also Caribbean rhythms which made up some of his ethnic background and Indian music which was another key to his works rhythmic complexity. Cecil Taylor’s music is amazing and complex as is Andrew Hill’s, even now their music seems ahead of the curve; musical taste makers still not having caught up to them. A modernism which in its newness and containing cerebral aspects, manages to intimidate many. Herbie’s manages to be cerebral but often with a playful sense of humor.

Before these sessions, as was Blue Note’s habit, the artists were allowed ample rehearsal time. In general, this practice led to the freedom to do more complex pieces and not have to have non-touring/working bands rely on jazz standards for lack of knowledge of a new piece.

There are no weak links in what is essentially two trios. Another practice of Blue Note’s was to put a more established musician from their stable on a session by a new guy. While this has never been disastrous it had made for some odd and uncomfortable pairings, such as some of the session men of Thelonious Monk’s Blue Note Debut "The Genuis of". Al McKibbon had been the house bassist at Birdland and often played with Thelonious Monk. He is able throughout the recordings to provide a solid bottom without any hint of boredom inducing repetition.

While it is easy to lament the fact that Herbie never got to play with the likes of Elvin Jones or Tony Williams, to name but two top notch skin-men, here, Max Roach is a perfect fit.

Like Herbie and many other greats of jazz’s next era, Max formally studied at the Manhattan School of Music. At the age of eighteen Max had been the house drummer at Monroe’s Uptown House, which along with Minton’s Playhouse was ground zero for bop. Here he came into contact with jazz’s vanguard.

He and Kenny Clark were directly involved with the creation of bop. Max was one of the first, true percussion stars who helped change the way his instrument was played. Instead of keeping time and then impressing during solos with pure speed, Max created the now well known technique of creating pulse points not with the base drum as had been the standard but utilizing the cymbals. This allowed for great freedom for the other instruments’ solos as well as his own. It also allowed for more dramatic and supple tempo changes.

Max would perfect his voice initially on the early important records of Charlie Parker’s, who he was with 1945, 1947-49 and 1951-53. He would appear with the who’s who of jazz. It was not until 1953 however that he finally recorded a date as a leader. Like many of his peers, he now saw bop as becoming formulaic but still a worth while jumping off point. With Miles Davis and a host of others there would be the "Birth of the Cool" sessions where he would participate in the birth of third-stream music, a sort of hybrid of symphonic big band mixed with intricate solos which organically grew out of the main body of a piece. There was ever an ongoing process of things being added to Max’s palate, the common factor throughout it all was an intricate forward thinking bent.

Around the time he was doing the sessions with Herbie he had also had his own group, co-led with trumpeter Clifford Brown and Bud Powell’s younger pianist brother, Ritchie. The group would last for only two years, a fatal car crash taking both Clifford and Ritchie. Max would continue the group with Kenny Dorham on trumpet and Sonny Rollins replacing Harold Land on tenor sax. These two versions of his group showed him the way to naturally meld impressive solos with more intricate arrangements, arrangements which did more than serve to fill time between the musicians' solos.

With Herbie you hear a most successful partnership not born of touring but sharing the same combination of daring and highly polished talent.

On disc two "House Party Starting" contains subtle tempo changes and a long snaking rhythm which is trance inducing, like watching candlelight reflect off the polished wood of a bar. The song seems to almost stop time without relying on mere repetition. This was actually the first song I ever heard by Herbie and every time, still, I marvel at not just the song structure but his ability to seamlessly change himself within the body of one piece.

Teddy Kotick throughout his career took great pride in sticking with the rhythm section and avoiding solos. He had a rich tone which has been heard on many important jazz records from the 50’s and 60’s. What is interesting is the subtle difference in the pieces which feature him as opposed to Al. Too often if a bassist does not specialize in solos or does not take his obligatory turn during a piece, people seem hard pressed to notice a difference. But notice the subtle changes in Max’s playing on pieces which feature him with Teddy instead of Al. Both bassists add to the pieces which already contain kinetic aspects to them.

The other drummer on the sessions is Art Blakey. Art had gotten his start in the big band circuit including time in the forward thinking Flecther Henderson group. He naturally gravitated towards the bop players brining the steady funky groove concept to this new jazz.

Art felt that with the possibilities of this new music being made, a band should work as a cohesive unit, not just providing back up for whom ever was soloing. He appeared on many seminal albums before forming a sort of jazz collective, The Jazz Messengers.

Art was one of the first jazz musicians to be interested in what would later be known as world music, mixing in aspects of it in his playing. Aside from leaving a legacy of adding to percussionists over all palette, he left what could possibly be considered jazz’s version of an ivy league school, The Jazz Messengers.

Many of his band members would go on to lead groups of their own. There were many incarnations of this band and the roster reads like jazz royalty role call.

Even while working with various versions of his own ensemble, Art was frequently to be found on other artists’ dates. He played on Thelonious Monk’s first Blue Note dates (now available as two separate remasters Genuis of Modern Music vols 1&2.) Similar to this Herbie Nichols collection, he and Max split drum duties on the still amazingly powerful album "Thelonious Monk Trio (Fantasy Records 1952.)

Around the time of the Herbie Nichols session, Art and an incarnation of the Jazz Messengers which featured Clifford Brown, Horace Silever, Lou Donaldson and Curly Russell were recorded live at Birdland. (A Night at Birdland Vols 1&2 Blue Note Records). Aside from being a compelling live document of a version of the Messengers which was as powerful as it was short lived, it manages to capture if not the birth, then the infancy of what would become known as hard-bop.

Both Max and Art had always been polyrhythmic, but Art ‘s was more an emphasis on setting up a funky groove.

On the first CD "It Didn’t Happen" which Herbie wrote just four days before going into the studio. It was inspired by an unrequited romance and Art shows that funky can also be accomplished with great subtlety.

Like Monk, Herbie did not often do covers and usually when done they would be lesser known pieces that could be made their own. Here Herbie tackles Gershwin’s "Mine" from a musical revue "Of Thee I Sing".

All the music to be found on these three discs is thoroughly engrossing, but not in a way that demands one listens in silence or alone.

When it comes up again, and I am looked at with skepticism by those who have yet to discover Herbie’s art, is he one of the greatest?

All I can do is paraphrase Joyce’s Molly Bloom:

"Yes, yes.."

Additional Info

- Artist / Group Name: Herbie Nichols

- CD Title: Herbie Nichols-The Complete Blue Note Recordings

- Genre: BeBop / Hard Bop

- Year Released: 1997

- Reissue Original Release: 1955-56

- Record Label: Blue Note

- Musicians: Herbie Nichols (piano), Al McKibbon, Teddy Kotick (bass), Max Roach, Art Blakey (drums)

- Label Website: -

- Rating: Four Stars

Music

Albums We Love: Herbie Nichols

by Jessica Rand KMHD Jazz Radio | June 4, 2013 3 p.m. | Updated: April 1, 2015 12:54 p.m.

Herbie Nichols

Love, Gloom, Cash, Love (Bethlehem, 1957)

Herbie Nichols has been called one of jazz’s “most tragically overlooked geniuses” and the pianist’s final 1957 masterpiece, Love, Gloom, Cash, Love, bears witness to that description. Some think of him as a disciple of Thelonius Monk, but that’s not giving him nearly enough credit. Highly imaginative and unpredictable, Nichols was a contemporary of Monk; he was also equally innovative, curious and playful.

For those who only know his earlier Blue Note recordings, or the iconic song he composed — Lady Sings the Blues — for Billie Holiday, the Bethlehem date is a revelation. The soothing sophistication of his piano work is rounded out by Charles Mingus’ drummer Dannie Richmond and bassist George Duvivier to create the challenging, provocative and magical wonderland that is Nichols’ vision of jazz. The melodies are complex; the rhythms subdued.

Denzil Best’s 45 Degree Angle is a finger-snapping, mischievous smoker while All the Way is breathtakingly restrained and romantic. The spirited warmth of Every Cloud is a playful exchange between Nichols’ heavy piano chords and Richmond’s shifting rhythms. Beyond Recall is a call-and-response jazz march, perhaps reminiscent of his days serving in World War II. Nichols’ whimsical imagination comes to the fore in the title track, Love, Gloom, Cash, Love, a sweet, gratifying waltz.

Sadly, just as Nichols began to develop a following, he was stricken with leukemia and died too young in 1963. Humble and hard-working, he wasn’t alive long enough to reap the benefits of his genius and his works went largely forgotten. It’s time to pull this album from the vaults and rediscover the warmth, imagination and spirit of his long overlooked brilliance.

– Jessica Rand, Host of Takin’ Off, Mon-Thurs, 3-6pm.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Herbie-Nichols

Herbie Nichols

American musician

Herbie Nichols, byname of Herbert Horatio Nichols (born Jan. 3, 1919, New York, N.Y., U.S.—died April 12, 1963, New York City), African-American jazz pianist and composer whose advanced bop-era concepts of rhythm, harmony, and form predicted aspects of free jazz.

Nichols attended the City College of New York and served in the U.S. Army in 1941–43. He participated in the Harlem sessions that led to the development of bop, and Billie Holiday wrote lyrics to his song “Lady Sings the Blues.” Most of his career, however, he spent playing in Dixieland and swing groups or accompanying singers and nightclub acts, only occasionally working with stylistic contemporaries or performing his original music publicly.

He composed about 170 songs, and in 1955–57 he recorded the four albums upon which his reputation is largely based. After his death, from leukemia, most of his unrecorded compositions were destroyed in an apartment flood; however, unissued recordings by Nichols, including eight “new” songs, were discovered and released in the 1980s.

As a pianist Nichols was at his best interpreting his own compositions; he also was his own best interpreter. Like early jazz composers, Nichols created portraits (“117th Street,” “Dance Line”) and dramas (“Love, Gloom, Cash, Love,” “The Spinning Song”) in his themes. The harmonic foundations of his songs were original and often daring; his structures frequently extended song form far beyond the customary four strain, 32 measure limits. His solos, which were variations on his themes, incorporated rhythmic displacements and reharmonizations and created open spaces in his melodic lines that inspired interplay with his drummers. The generous strain of humour in his work belied the difficulties he experienced in his career.

Friday, March 13, 2015

The Music of Herbie Nichols featuring Jason Marsalis

I've got a string of interesting gigs coming up these days including several dates leading a quartet featuring Jason Marsalis on vibraphone, playing the music of pianist Herbie Nichols.

I've been fascinated with Nichols' music for over ten years now. I was first introduced to his music while I was studying with Matt Wilson in New York City in 2004 and he was playing with the Herbie Nichols Project, a band co-led by Ben Allison and Frank Kimbrough that extensively researched and performed his music.

I'm also looking forward to finally working with Jason Marsalis. He's a force on the drums AND now the vibraphone as well!

We are at the Yardbird Suite in Edmonton, AB on Friday, March 20th:

And River Park Church in Calgary on Saturday, March 21st, presented by JazzYYC:

Here's a link to a little interview I did with JazzYYC in advance of our Calgary concert:

Interview: Fay Victor on Herbie Nichols

(photo: Fay Victor by Eliseo Cardona)

Some of the most memorable – poetically exuberant and just plain house-rocking – concerts over the past five years of the Sound It Out series have been those by singer Fay Victor’s Herbie Nichols Sung band. This Friday, June 23, at Greenwich House Music School, Fay will return to lead her hard-grooving quintet in a two-set event to help celebrate the fifth anniversary of Sound It Out, as well as raise money for Greenwich House. Fay and company – Michaël Attias (alto and baritone saxophones), Anthony Coleman (piano), Ratzo Harris (double-bass) and Devin Gray (drums) – will be performing her vocal re-creations of music by the great, unsung bop-era pianist-composer Herbie Nichols, who penned the music for Billie Holiday’s “Lady Sings the Blues,” along with making evergreen trio recordings under his own name for Blue Note and Bethlehem. Nichols, a New York City native born in 1919 and who died at age 44 in 1963, would no doubt love what Fay does with his music, as he once said: “The voice is the most beautiful instrument of all.”

About her project to convey the spirit of this music vocally, Fay told me: “I’ve been working with Herbie Nichols’ music for over a decade and a half – I’m madly in love with it. His is joyous, irresistible music, even if it has been sadly underplayed. There are scholarly approaches to his pieces, but our way is to open up the forms and get that joyousness across. Except for Billie’s words to ‘Lady Sings the Blues,’ I wrote the lyrics to all the tunes, with the words coming out of the music itself and my response to it. The way the band plays is sensitive and open but with real muscularity and intensity. I hope people aren’t intimidated if they don’t know the music or even the name of Herbie Nichols – I want them to come dig the music and leave having been taken by the beauty of the melodies and their singability. I want people to fall in love with Herbie Nichols like I have.”

Before my interview with Fay continues below, it’s perhaps best to interpolate a description of Nichols’ music – the best I know – that appears in the liner notes to the indispensable boxed set The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Herbie Nichols. Describing the art of Nichols, estimable jazzers Frank Kimbrough and Ben Allison write: “As a pianist, [Herbie] was kaleidoscopic, encompassing the entire history of jazz piano and much of European classical music as well, which blended with his own innovative harmonic and rhythmic ideas – allowing him to weave a style that is essentially a school unto itself. Although his playing is often compared to that of his contemporaries Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell – and one can also detect the influence of Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum and Jelly Roll Morton, among others – [Herbie] is like no other. He possessed a touch capable of evoking the entire emotional spectrum, from quiet introspection to joyous exuberance, and from delicate sensitivity to primitive brutality…

“As a composer… [Herbie penned] tunes that are evocative, usually written with a particular place, person, event or feeling in mind. His oblique approach to melody and harmony creates musical ideas that sparkle the more they are scrutinized. Herbie’s love of mixing the strange with the familiar gives his music the feeling of simultaneously looking backward and forward in time. Imagine a Dixieland beat, a diatonic, hummable melody, and the harmonies of Bartók all woven together and you’ll get the idea. Nobody’s music grooves like Herbie’s… [It] reveals a lope and sense of humor that could only come from playing the Harlem and Greenwich Village dives where he so often worked. You can feel the sweat of the crowd, see the dancers, taste the 15-cent beers, smell the cigarette smoke swirling around the music.”

How could you not dig that? Now onto more of my conversation with Fay…

Bradley Bambarger: Was the late-’80s LP Carmen Sings Monk, by Carmen McRae, a key inspiration for you? Did it plant a seed for your Herbie Nichols Sung project?

Fay Victor: Oh, yes, that was a big inspiration, as I first heard it around the time I got started singing. I know and love that album deeply – it’s amazing, so adventurous. It was the first record I knew where a singer devoted an entire album to exploring a composer of primarily instrumental music. As much as I had loved Monk before that – and knew the famous vocal versions of “Round Midnight” that had already been done – the Carmen McRae album made Monk’s music more accessible to me as a singer. It opened up possibilities in my thinking. But a figure who inspired me directly when it came to the music of Herbie Nichols was the late Mischa Mengelberg [the Dutch pianist, composer and arranger, who recorded exciting, individualist interpretations of Nichols’ music with his ICP Orchestra]. I’m dedicating this concert to Mischa’s memory, his example. He had this deep knowledge of the jazz tradition, as well as a real love of improvisation – and a playful sense of humor.

My first work with Herbie’s music was when I wrote lyrics for his tune “House Party Starting,” calling it “Tonight.” I recorded that song for my second album, Darker Than Blue, which came out in 2001. Pianist Vijay Iyer and bassist John Hébert, who many jazz fans know well, were on that record. All these years later, and I’ve recently recorded a live trio album of Herbie Nichols music in Europe, with pianist Achim Kaufmann and reed player Tobias Delius at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam and the Loft in Cologne.

BB: What does the music of Herbie Nichols say to you?

FV: More than anything, there’s that joy in Herbie’s compositions. The sheer exuberance in his music is one element that makes it ideal for singing. You know, Herbie’s mother was from Trinidad and so was my mother. I’ve spent a lot of time down there, and I can discern a characteristic Trinidadian trait in his music, a mix of intellectual confidence on one hand and not taking yourself too seriously on the other. There’s a good-time element to Herbie’s songs coupled with a sense of cultural and creative achievement. We want to bring something of that alive in the way we use the tunes as vehicles for improvisation, taking advantage of the elasticity of the music. One thing I learned from working with Mischa and the ICP is that it’s not just the notes and the harmonic contours of a song that matter – it’s also the spirit of what it means to us. So, we open the songs up: The composition as a composition is stated, but where in the process it’s stated is open to the moment.

BB: Describe the particular sonic character of your Herbie Nichols Sung band.

FV: First of all, these guys bring a real intensity to this music, whether it’s the sort of smoldering intensity that Michaël Attias has or the burning intensity of Anthony Coleman. Ratzo Harris, too – the whole band has a strong sense of ‘inside-outside’ playing, as we’re going in and out of the structure of the material. These guys are so good at jumping between the two worlds seamlessly. For jazz repertory bands, it’s hard to find players who both know the tradition and can take it further, but these are the right musicians for it. They can take the music to a free space and then jump back to form and time effortlessly. All of these guys love Herbie’s music, and you can hear that. Michaël was into Herbie way before this band. Anthony, of course, is someone who knows jazz from its very beginnings all the way forward. He had previously delved more deeply into Monk and Jelly Roll Morton, but that experience makes him an ideal player for Herbie’s music. The usual drummer for this project, Rudy Royston, couldn’t make the gig, so we have Devin Gray – this will be his first show with the band. We rehearsed the other day, and Devin got it right off – while bringing his own energy to the music.

BB: Which tunes will be on the set list?

FV: We’ll be doing “House Party Starting,” “The Gig,” “2300 Skidoo,” “Step Tempest” and “Lady Sings the Blues,” among others. And we’ll be presenting three tunes with my lyrics for the first time live: “Double Exposure,” “Another Friend” and “Twelve Bars.” We’re really looking forward to sharing this music with the Sound It Out audience at Greenwich House. As I said before, we want people to fall in love with the music of Herbie Nichols like we have.

(photo: Fay Victor’s Herbie Nichols Sung, by Bradley Bambarger)

Posted in

Apple Music Preview

Herbie Nichols

One of jazz's most tragically overlooked geniuses, Herbie Nichols was a highly original piano stylist and a composer of tremendous imagination and eclecticism. He wasn't known widely enough to exert much influence in either department, but his music eventually attracted a rabid cult following, though not quite the wide exposure it deserved.

Nichols was born January 3, 1919, in New York and began playing piano at age nine, later studying at C.C.N.Y. After serving in World War II, Nichols played with a number of different groups and was in on the ground floor of the bebop scene. However, to pay the bills he later focused on Dixieland ensembles; his own music -- a blend of Dixieland, swing, West Indian folk, Monk-like angularity, European classical harmonies via Satie and Bartók, and unorthodox structures -- was simply too unclassifiable and complex to make much sense to jazz audiences of the time. Mary Lou Williams was the first to record a Nichols composition -- "Stennell," retitled "Opus Z," in 1951; yet aside from the song he wrote for Billie Holiday, "Lady Sings the Blues," none of Nichols' work got enough attention to really catch on.

He signed with Blue Note and recorded three brilliant piano trio albums from 1955-1956, adding another one for Bethlehem in late 1957. Nichols languished in obscurity after those sessions, though; sadly, just when he was beginning to find a following among several of the new thing's adventurous, up-and-coming stars, he was stricken with leukemia and died on April 12, 1963. In the years that followed, Nichols became a favorite composer in avant-garde circles, with tributes to his sorely neglected legacy coming from artists like Misha Mengelberg and Roswell Rudd. He also inspired a repertory group, called the Herbie Nichols Project, and most of his recordings were reissued on CD. ~ Steve Huey

- ORIGIN

- New York, NY

- GENRE

- BORN: 3 Jan 1919

Top Songs

The Third World

Original Jazz Sound: The Prophetic

The Third World

100 Jazz Masterpieces, Vol.17

The Third World (New Jersey, May 6, 1955)

Herbie Nichols Trio: Complete Studio Master Takes

Blue Chopsticks

THE MUSIC OF HERBIE NICHOLS: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH HERBIE NICHOLS:

Herbie Nichols - Step Tempest

Herbie Nichols Trio - The Lady Sings The Blues

Herbie Nichols Trio "Riff Primitif"

Herbie Nichols - House party starting

Herbie Nichols Vol 2 Side 1

Herbie Nichols Trio - Terpischore

Herbie Nichols - The Third World

Herbie Nichols Trio - The Gig

Herbie Nichols Trio - Wildflower

Herbie Nichols - Blue Chopstricks

Herbie Nichols - Shuffle Montgomery

The Best of Herbie Nichols--Jazz Piano Legend

Herbie Nichols’ Third World

by David Johnson

Posted April 5, 2010

Pianist, composer and intellectual Herbie Nichols was obscure in his lifetime, rediscovered and celebrated years later. Biographer Mark Miller joins us.

Photo: Cover art

When Herbie Nichols died in 1963 at the age of 44, he was unknown to all but a few young jazz artists and a handful of critics and fans who’d happened to hear the LPs he recorded for Blue Note in the mid-1950s. Those who did know him nearly always spoke of a gentle, quiet, intellectually and creatively vital person. In the mid-1970s, his recordings began to circulate again, his compositions re-recorded by other jazz artists. After his death, Nichols’ music won the respect, love and acclaim that was missing during his lifetime.

Music From Many Worlds

As Nichols friend and longtime advocate Roswell Rudd has noted, his music evokes everything from Africa and the West Indies of his parents’ origin to the people and places of his mid-20th-century New York City life, and to the strange and wondrous places of his own imagination as well. It radiates a kind of goodness—perhaps why Rudd has written that those who record Nichols’ music improve the world by doing so.

What world did Nichols himself come from? In his recent book Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life, jazz writer Mark Miller makes a compelling case for the pianist as a product of the Harlem Renaissance. Miller joins us on Night Lights this week for a look at Nichols’ life and music, featuring several of the pianist’s key Blue Note recordings, as well as a side from his rarely-heard debut as a leader, and a solo from one of his few recorded Dixieland gigs that Nichols often had to take for economic survival.

The book Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life is available through both The Mercury Press and Amazon.

UPDATE: Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life is now available through Teksteditions.

Unheard Herbie

Here are some outtakes from my interview with Mark Miller that didn’t make it into the program:

- Why modern jazz musicians find Nichols’ music so appealing

- Herbie Nichols and Thelonious Monk

- Nichols’ composition “Amoeba’s Dance”

UPDATE: also check out Jason Crane’s great new interview with Mark Miller on The Jazz Session.

Music Heard On This Episode

Cro-Magnon Nights

Herbie Nichols — Complete Studio Master Takes (Lonehill, 2005)

Herbie Nichols

| Herbie Nichols | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Herbert Horatio Nichols |

| Born |

January 3, 1919

San Juan Hill, Manhattan, New York, U.S.

|

| Died |

April 12, 1963 (aged 44)

New York City

|

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Labels | Blue Note, Bethlehem |

Herbert Horatio Nichols (3 January 1919 – 12 April 1963) was an American jazz pianist and composer who wrote the jazz standard "Lady Sings the Blues". Obscure during his lifetime, he is now highly regarded by many musicians and critics.[1]

Contents

Life

He was born in San Juan Hill, Manhattan in New York City to parents from St. Kitts and Trinidad and grew up in Harlem.[2]:156,174 During much of his life he took work as a Dixieland musician while working on the more adventurous kind of jazz he preferred.[2]:155–56 He is best known today for these compositions, program music that combines bop, Dixieland, and music from the Caribbean with harmonies from Erik Satie and Béla Bartók.

His first known work as a musician was with the Royal Barons in 1937, but he did not find performing at Minton's Playhouse a few years later a very happy experience. The competition didn't suit him. However, he did become friends with pianist Thelonious Monk even if his own critical neglect would be more enduring.

Nichols was drafted into the Army in 1941. After the war he worked in various settings, beginning to achieve some recognition when Mary Lou Williams recorded some of his songs in 1952.[2]:165 From about 1947 he persisted in trying to persuade Alfred Lion at Blue Note Records to sign him up.[2]:168 He finally recorded some of his compositions for Blue Note in 1955 and 1956, some of which were not issued until the 1980s. His tune "Serenade" had lyrics added, and as "Lady Sings the Blues" became firmly identified with Billie Holiday. In 1957 he recorded his last album for Bethlehem Records.

Nichols died from leukemia in New York City at the age of 44.

A biography, Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist's Life, written by Mark Miller, was published in 2009.[3]

Influence

His music has been most energetically promoted by Roswell Rudd, who worked with Nichols in the early 1960s. Rudd recorded or programmed at least three albums featuring Nichols' compositions, including The Unheard Herbie Nichols (1996) and a book The Unpublished Works (2000).[4]

In 1984, the Steve Lacy quintet with George Lewis, Misha Mengelberg, Han Bennink and Arjen Gorter performed the music of Nichols at the Ravenna Jazz Festival in Italy.[5]

A New York group, the Herbie Nichols Project (part of the Jazz Composers Collective) has recorded three albums largely dedicated to unrecorded Nichols' compositions, many of which Nichols had deposited in the Library of Congress.[6]

Discography

As leader

- 1955: The Prophetic Herbie Nichols Vol. 1 (Blue Note) with Art Blakey (drums), Al McKibbon (bass)

- 1955: The Prophetic Herbie Nichols Vol. 2 (Blue Note) with Art Blakey (drums), Al McKibbon (bass)

- 1956: Herbie Nichols Trio (Blue Note) with Max Roach (drums), Al McKibbon or Teddy Kotick (bass)

- 1957: Love, Gloom, Cash, Love (Bethlehem) with Dannie Richmond (drums), George Duvivier (bass)

References

- Corroto, Mark (1 November 2001). "Strange City: The Herbie Nichols Project". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

Further reading

- Nichols, Herbie; Rudd, Roswell (2000). The Unpublished Works of Herbie Nichols: 27 Jazz Masterpieces. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Gerard & Sarzin Pub. Co. ISBN 978-1-930-08000-3. OCLC 45456453.

- Miller, Mark (2009). Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist's Life. Toronto: Mercury Press Publishers. ISBN 978-1-551-28146-9. OCLC 705897987.