AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/10/john-birks-dizzy-gillespie-1917-1993.html

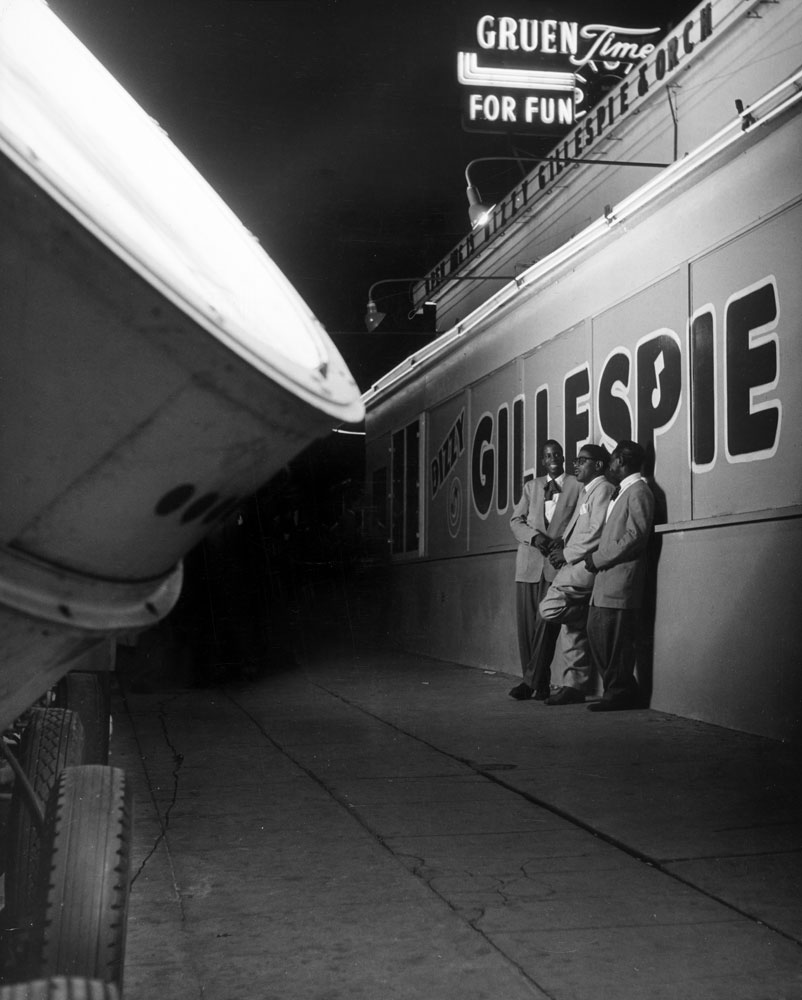

PHOTO: DIZZY GILLESPIE (1917-1993)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/dizzy-gillespie-mn0000162677

Dizzy Gillespie

(1917-1993)

Biography by Scott Yanow

Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarroinstead, and it was not until Jon Faddis' emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated. Somehow, Gillespie could make any "wrong" note fit, and harmonically he was ahead of everyone in the 1940s, including Charlie Parker. Unlike Bird, Dizzy was an enthusiastic teacher who wrote down his musical innovations and was eager to explain them to the next generation, thereby insuring that bebop would eventually become the foundation of jazz.

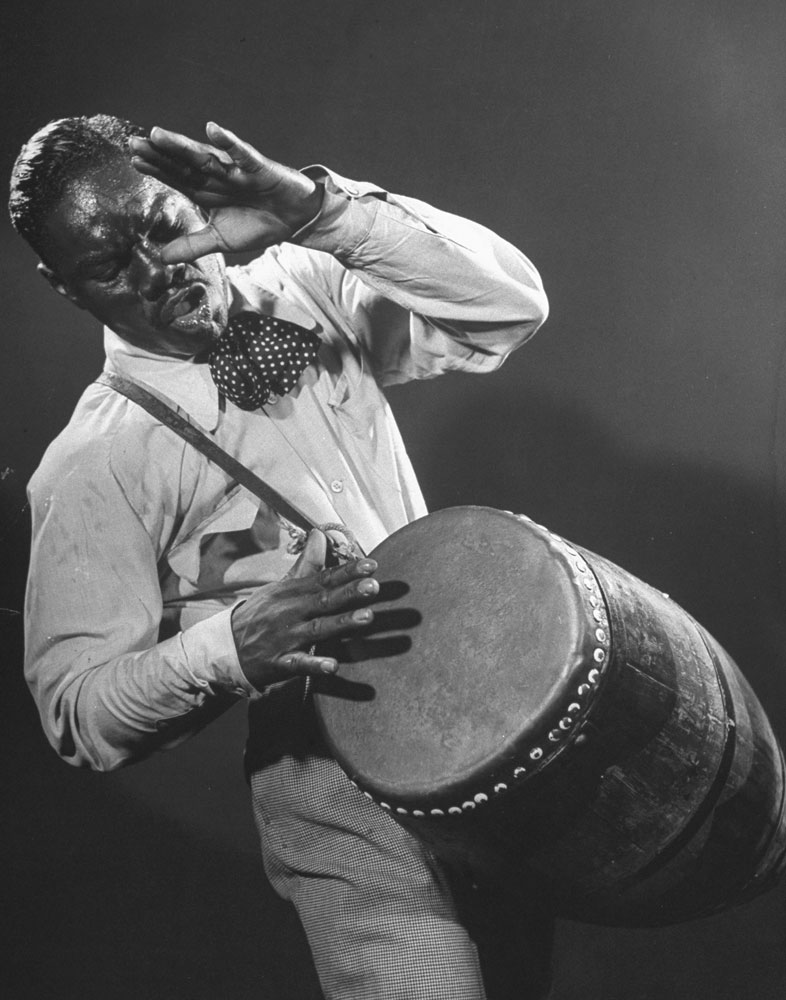

Dizzy Gillespie was also one of the key founders of Afro-Cuban (or Latin) jazz, adding Chano Pozo's conga to his orchestra in 1947, and utilizing complex poly-rhythms early on. The leader of two of the finest big bands in jazz history, Gillespie differed from many in the bop generation by being a masterful showman who could make his music seem both accessible and fun to the audience. With his puffed-out cheeks, bent trumpet (which occurred by accident in the early '50s when a dancer tripped over his horn), and quick wit, Dizzy was a colorful figure to watch. A natural comedian, Gillespie was also a superb scat singer and occasionally played Latin percussion for the fun of it, but it was his trumpet playing and leadership abilities that made him into a jazz giant.

The youngest of nine children, John Birks Gillespie taught himself trombone and then switched to trumpet when he was 12. He grew up in poverty, won a scholarship to an agricultural school (Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina), and then in 1935 dropped out of school to look for work as a musician. Inspired and initially greatly influenced by Roy Eldridge, Gillespie (who soon gained the nickname of "Dizzy") joined Frankie Fairfax's band in Philadelphia. In 1937, he became a member of Teddy Hill's orchestra in a spot formerly filled by Eldridge. Dizzy made his recording debut on Hill's rendition of "King Porter Stomp" and during his short period with the band toured Europe. After freelancing for a year, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra (1939-1941), recording frequently with the popular bandleader and taking many short solos that trace his development; "Pickin' the Cabbage" finds Dizzy starting to emerge from Eldridge's shadow. However, Calloway did not care for Gillespie's constant chance-taking, calling his solos "Chinese music." After an incident in 1941 when a spitball was mischievously thrown at Calloway (he accused Gillespie but the culprit was actually Jonah Jones), Dizzy was fired.

By then, Gillespie had already met Charlie Parker, who confirmed the validity of his musical search. During 1941-1943, Dizzy passed through many bands including those led by Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Charlie Barnet, Fess Williams, Les Hite, Claude Hopkins, Lucky Millinder (with whom he recorded in 1942), and even Duke Ellington (for four weeks). Gillespie also contributed several advanced arrangements to such bands as Benny Carter, Jimmy Dorsey, and Woody Herman; the latter advised him to give up his trumpet playing and stick to full-time arranging.

Dizzy ignored the advice, jammed at Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House where he tried out his new ideas, and in late 1942 joined Earl Hines' big band. Charlie Parker was hired on tenor and the sadly unrecorded orchestra was the first orchestra to explore early bebop. By then, Gillespie had his style together and he wrote his most famous composition "A Night in Tunisia." When Hines' singer Billy Eckstine went on his own and formed a new bop big band, Diz and Bird (along with Sarah Vaughan) were among the members. Gillespie stayed long enough to record a few numbers with Eckstine in 1944 (most noticeably "Opus X" and "Blowing the Blues Away"). That year he also participated in a pair of Coleman Hawkins-led sessions that are often thought of as the first full-fledged bebop dates, highlighted by Dizzy's composition "Woody'n You."

1945 was the breakthrough year. Dizzy Gillespie, who had led earlier bands on 52nd Street, finally teamed up with Charlie Parker on records. Their recordings of such numbers as "Salt Peanuts," "'Shaw Nuff," "Groovin' High," and "Hot House" confused swing fans who had never heard the advanced music as it was evolving; and Dizzy's rendition of "I Can't Get Started" completely reworked the former Bunny Berigan hit. It would take two years for the often frantic but ultimately logical new style to start catching on as the mainstream of jazz. Gillespie led an unsuccessful big band in 1945 (a Southern tour finished it), and late in the year he traveled with Parker to the West Coast to play a lengthy gig at Billy Berg's club in L.A. Unfortunately, the audiences were not enthusiastic (other than local musicians) and Dizzy (without Parker) soon returned to New York.

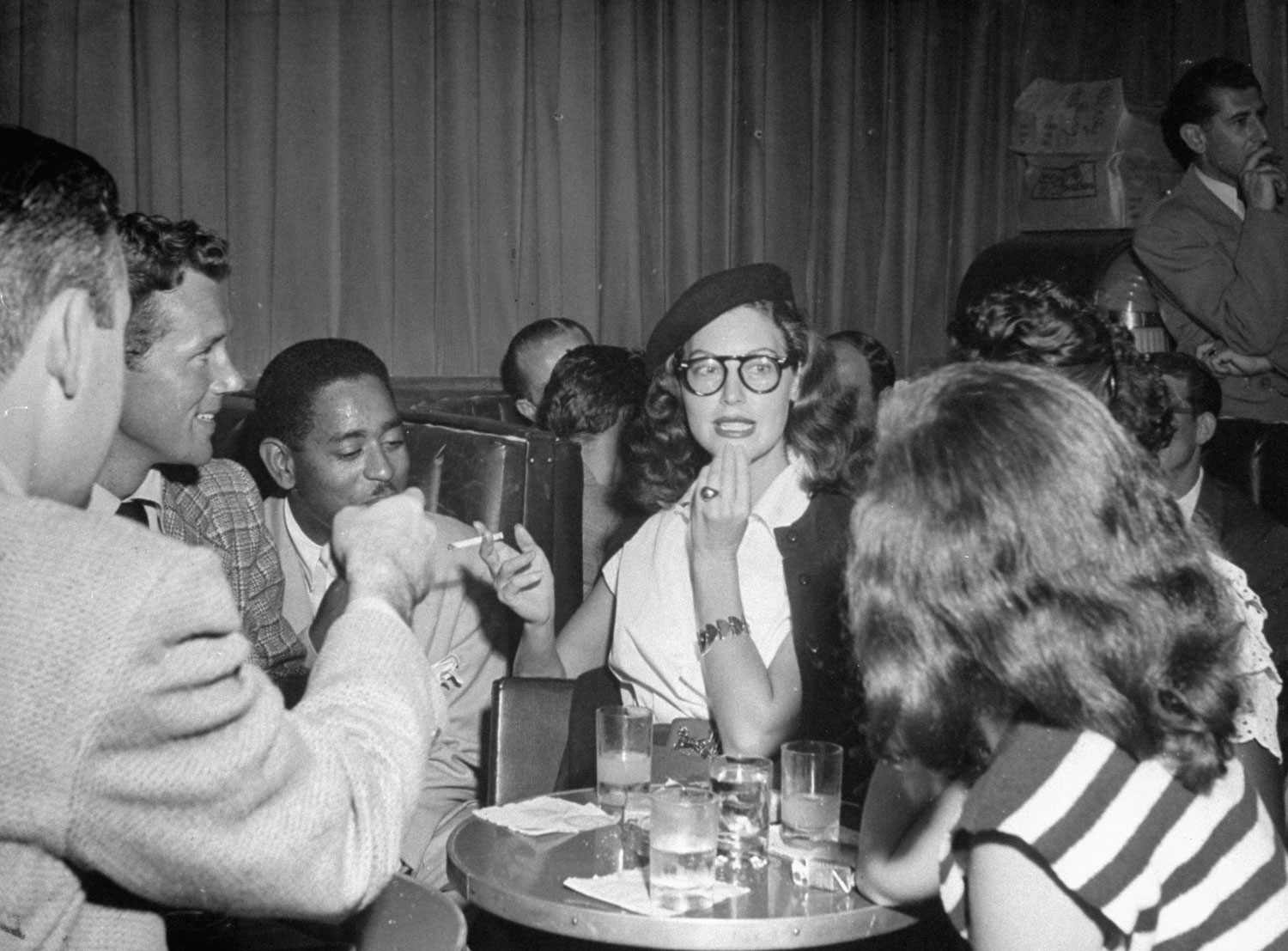

The following year, Dizzy Gillespie put together a successful and influential orchestra which survived for nearly four memorable years. "Manteca" became a standard, the exciting "Things to Come" was futuristic, and "Cubana Be/Cubana Bop" featured Chano Pozo. With such sidemen as the future original members of the Modern Jazz Quartet (Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Ray Brown, and Kenny Clarke), James Moody, J.J. Johnson, Yusef Lateef, and even a young John Coltrane, Gillespie's big band was a breeding ground for the new music. Dizzy's beret, goatee, and "bop glasses" helped make him a symbol of the music and its most popular figure. During 1948-1949, nearly every former swing band was trying to play bop, and for a brief period the major record companies tried very hard to turn the music into a fad.

By 1950, the fad had ended and Gillespie was forced, due to economic pressures, to break up his groundbreaking orchestra. He had occasional (and always exciting) reunions with Charlie Parker (including a fabled Massey Hall concert in 1953) up until Bird's death in 1955, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic (where he had opportunities to "battle" the combative Roy Eldridge), headed all-star recording sessions (using Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, and Sonny Stitt on some dates), and led combos that for a time in 1951 also featured Coltrane and Milt Jackson. In 1956, Gillespie was authorized to form a big band and play a tour overseas sponsored by the State Department. It was so successful that more traveling followed, including extensive tours to the Near East, Europe, and South America, and the band survived up to 1958. Among the young sidemen were Lee Morgan, Joe Gordon, Melba Liston, Al Grey, Billy Mitchell, Benny Golson, Ernie Henry, and Wynton Kelly; Quincy Jones (along with Golson and Liston) contributed some of the arrangements. After the orchestra broke up, Gillespie went back to leading small groups, featuring such sidemen in the 1960s as Junior Mance, Leo Wright, Lalo Schifrin, James Moody, and Kenny Barron. He retained his popularity, occasionally headed specially assembled big bands, and was a fixture at jazz festivals. In the early '70s, Gillespie toured with the Giants of Jazz and around that time his trumpet playing began to fade, a gradual decline that would make most of his '80s work quite erratic. However, Dizzy remained a world traveler, an inspiration and teacher to younger players, and during his last couple of years he was the leader of the United Nation Orchestra (featuring Paquito D'Rivera and Arturo Sandoval). He was active up until early 1992.

Dizzy Gillespie's career was very well documented from 1945 on, particularly on Musicraft, Dial, and RCA in the 1940s; Verve in the 1950s; Philips and Limelight in the 1960s; and Pablo in later years.

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1021.html

January 7, 1993

OBITUARY

Dizzy Gillespie, Who Sounded Some of Modern Jazz's Earliest Notes, Dies at 75

by PETER WATROUS

New York Times

Dizzy

Gillespie, the trumpet player whose role as a founding father of modern

jazz made him a major figure in 20th-century American music and whose

signature moon cheeks and bent trumpet made him one of the world's most

instantly recognizable figures, died yesterday at Englewood Hospital in

Englewood, N.J.

Mr. Gillespie, who was 75, had been suffering for some time from pancreatic cancer, his press agent, Virginia Wicks, said.

In

a nearly 60-year career as a composer, band leader and innovative

player, Mr. Gillespie cut a huge swath through the jazz world. In the

early 40's, along with the alto saxophonist Charlie (Yardbird) Parker,

he initiated be-bop, the sleek, intense, high-speed revolution that has

become jazz's most enduring style. In subsequent years he incorporated

Afro-Cuban music into jazz, creating a new genre from the combination.

In

the naturally effervescent Mr. Gillespie, opposites existed. His

playing -- and he performed constantly until nearly the end of his life

-- was meteoric, full of virtuosic invention and deadly serious. But

with his endlessly funny asides, his huge variety of facial expressions

and his natural comic gifts, he was as much a pure entertainer as an

accomplished artist. In some ways, he seemed to sum up all the

possibilities of American popular art.

From Carolina To the Big Bands

John

Birks Gillespie was born in Cheraw, S.C., on Oct. 21, 1917. His father,

a bricklayer, led a local band, and by the age of 14 the young

Gillespie was practicing the trumpet. He and his family moved to

Philadelphia two years later, and Mr. Gillespie, though he thought about

entering Temple University, quickly began a succession of professional

jobs.

He worked with Bill Doggett, the pianist and organist, who

fired him for not being able to read music well enough, and then Frank

Fairfax, a big-band leader whose orchestra included the trumpeter

Charlie Shavers and the clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton. Mr. Gillespie was

listening to the trumpeter Roy Eldridge, copying his solos and emulating

his style, and was soon performing with Teddy Hill's band at the Savoy

Ballroom on the basis of his ability to reproduce Mr. Eldridge's style.

According

to legend, it was Mr. Hill who gave Mr. Gillespie his nickname because

of his odd clothing style and his fondness for practical jokes. Mr.

Gillespie began cultivating his personality, putting his feet up on

music stands during shows and regularly cracking jokes. But by May 1937

he was also recording improvisations with the Hill band and helping the

performances by setting riffs behind soloists.

Two years later,

Mr. Gillepsie was considered accomplished enough to take part in a

series of all-star recordings with Lionel Hampton, Benny Carter, Coleman

Hawkins, Ben Webster and Chu Berry. He soloed on "Hot Mallets."

That

year, 1939, he joined Cab Calloway's band, one of the leading black

orchestras of the era. Though a dance band, its musicians, who included

the bassist Milt Hinton and the guitarist Danny Barker, liked to

experiment. Mr. Gillespie would work on the harmonic substitutions that

eventually became be-bop. Mr. Gillespie was a regular soloist with the

band, and by then his harmonic sensibility was beginning to take shape.

Joining With Parker To Mold New Style

It

was while touring with the Calloway band in 1940 that Mr. Gillespie met

Charlie Parker in Kansas City. And it was with him that Mr. Gillespie

began formulating the style that was eventually called be-bop. Along

with a handful of other musicians, including Thelonious Monk and Kenny

Clarke, Mr. Gillespie and Mr. Parker would regularly experiment.

On

live recordings of the period, especially the two solos on the tune

"Kerouac," recorded in 1941 at Minton's Uptown Playhouse, a club in

Harlem, can be heard his increasing interest in harmony, sleeker rhythms

and a divergence from the style of Mr. Eldridge. Mr. Gillespie was

blunt about his relationship with Mr. Parker, calling him "the other

side of my heartbeat," and freely giving him credit for some of the

rhythmic innovations of be-bop.

At the same time that Mr.

Gillespie was experimenting with the new style, he was regularly

arranging and recording for Mr. Calloway, including one of his better

improvisations on "Pickin' the Cabbage," a piece he composed and

arranged. In September 1941, at the State Theater in Hartford, Mr.

Gillespie was involved in an incident that shaped his reputation and his

career. Mr. Calloway saw a spitball thrown on stage and thought Mr.

Gillespie had done it; the two men fought, and Mr. Gillespie pulled a

knife and put a cut in Mr. Calloway's posterior that required 10

stitches to close.

Mr. Gillespie was fired from that job, but

spent the next several years working with some of the biggest names in

jazz, including Coleman Hawkins (who recorded the first version of Mr.

Gillespie's classic "Woody 'N' You"), Benny Carter, Les Hite (for whom

he recorded "Jersey Bounce," considered the first be-bop solo), Lucky

Millinder, Earl Hines, Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington. For Mr.

Millinder he made "Little John Special," which includes a riff of Mr.

Gillespie's that was later fleshed out into the composition "Salt

Peanuts," one of his best-known pieces.

The early 40's were a

turbulent time for jazz. Be-bop was slowly making itself felt, but at

the same time a series of disputes between recording companies and the

musicians' union resulted in a recording ban, so Mr. Gillespie and Mr.

Parker were rarely recorded. In 1943 Mr. Gillespie led a band with the

be-bop bassist Oscar Pettiford at the Onyx Club on 52d Street in

Manhattan. And in 1944, the singer Billy Eckstine took over part of the

Earl Hines band and created the first be-bop orchestra, of which few

recorded performaces exist. Mr. Gillespie was the music director, and

the band featured his "Night in Tunisia."

It was in 1945 that

Mr. Gillespie began to break out. He undertook an ambitious recording

schedule, recording with the pianist Clyde Hart and with Mr. Parker,

Cootie Williams, Red Norvo, Sarah Vaughan and Slim Gaillard. And he

began series of his own recordings that have since become some of jazz's

most important pieces.

Recording under his own name for the

first time, he made "I Can't Get Started," "Good Bait," "Salt Peanuts"

and "Be-bop," during one session in January 1945. He followed it up with

a recording date featuring Mr. Parker that included "Groovin' High,"

"Dizzy Atmosphere" and "All the Things You Are."

These

recordings, with their tight ensemble passages, precisely articulated

rhythms and dissonance as part of the palate of jazz, were to influence

jazz forever. Though Mr. Gillespie enjoyed playing for dancers, this was

music that was meant first and foremost to be listened to. It was

virtuosic in a way not heard before, and it was music that sent music

students scurrying to their turntables to learn the improvisations by

heart.

They were also the recordings that captured Mr. Gillespie

at his most impressive. His lines, jagged and angular, always seemed off

balance. He used chromatic figures, and was not afraid to resolve a

line on a vinegary, bitter note. And his improvising was eruptive;

suddenly, a line would bolt into the high register, only to come

tumbling down.

Mr. Gillespie did more than just record in 1945.

He put together the first of his big bands, and then formed a quintet

with Mr. Parker that Mr. Gillespie called "The height of perfection in

our music." It included Bud Powell on piano, Ray Brown on bass and Max

Roach on drums. Later that year, Mr. Gillespie reformed the big band,

called the Hepsations of 1945. Despitea tour of the South that was

almost catastrophically unsuccessful, the band stayed together for the

next four years. Another Revolution: Afro-Cuban Jazz

It was with

this big band, whose name became the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra, that Mr.

Gillespie created his second revolution in the late 1940's. An old

friend, the Cuban trumpeter Mario Bauza, who had made it possible for

him to join the Calloway orchestra, introduced Mr. Gillespie to the

Cuban conga player Luciano (Chano Pozo) Gonzales.

"Dizzy used to

ask me about Cuban rhythms all the time," said Mr. Bauza. "I introduced

him to Chano Pozo, and they wrote 'Manteca.' It was a good marriage of

two cultures. That was the beginning of Afro-Cuban jazz. That blew up

the whole world."

Mr. Gillespie quickly produced the sketches for

"Cubana Be" and "Cubana Bop," which were finished by the composer and

arranger George Russell and included some of the first modal harmonies

in jazz. And in "Manteca," Mr. Gillespie's collaboration with Mr. Pozo,

he created a work that is still performed and quoted regularly, by both

Latin orchestras and by jazz musicians. Without the sophisticated

arrangements and the conjunction of Latin rhythms and jazz harmonies

that Mr. Gillespie provided, both jazz and Latin music would be

radically different today.

The band's highest moments, however,

were when Mr. Gillespie -- in a move that characterized his career --

hired some of the young be-boppers on the scene. Among them were the

pianist John Lewis, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, bassist Ray Brown and

drummer Kenny Clarke, who went on to form the Modern Jazz Quartet. "It

was an incredible experience because so much was going on," Mr. Lewis

recalled. "Not only was he using these great be-bop arrangements but he

was so encouraging. It was my first job, a formative experience."

Mr.

Gillespie's was the last great evolutionary big band, and during its

tenure he hired the best soloists, from Jimmy Heath, James Moody and

Sonny Stitt to John Coltrane and Paul Gonzalves. Arrangements like

"Things to Come," with their exhilarating precision, were be-bop and

orchestral landmarks, with dense harmonies and flashy rhythms.

And

it was with his big band that Mr. Gillespie fully developed the other

side of his musical personality. With songs like "He Beeped When He

Should Have Bopped," "Ool Ya Koo", "Oo Pop A Da" and others, he began

popularizing the Bohemian, Dadaesque aspects of be-bop.

Mr.

Gillespie was a keen popularizer, and with his sense of comedy managed

to make his shows into an extraordinary mixture of entertainment and

esthetics. In so doing, he was following in the path of his

ex-bandleader, Mr. Calloway, as well as Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller.

From

then on, he cultivated an audience that went beyond the average jazz

fan, and it was this reputation that helped in his later career. And at

the same time, be-bop fashion made an appearance, with Mr. Gillespie, in

thick glasses and a beret, leading the way.

The big-band

business slowed down considerably in the late 1940's and early 50's, and

Mr. Gillespie teamed with Stan Kenton's orchestra as a featured

soloist. Then he began using a small group again.

He formed his

own record company in 1951, Dee Gee, which folded soon after. Mr.

Gillespie and Mr. Parker recorded for Verve, with Mr. Monk, and he and

Mr. Parker performed at Birdland in Manhattan the next year. He toured

Europe and in 1953 joined Mr. Parker, Mr. Powell, Mr. Roach and the

bassist Charles Mingus for a concert at Massey Hall in Toronto that

became legendary for its disorganization and for acrimony among

performers.

It was also in 1953 that someone fell on Mr.

Gillespie's trumpet, and bent it. When he played the misshapen

instrument, Mr. Gillespie found he could hear the sound more clearly,

and so decided to keep it. Along with those cheeks, it became his

trademark.

During the 1950's Mr. Gillespie recorded with with

Stan Getz, Stuff Smith, Sonny Stitt, Mr. Eldridge and others. In 1956,

he formed another big band and, at the behest of the United States State

Department, toured the Middle East and South America. In 1957, Mr.

Gillespie presided over "The Eternal Triangle," a recording that

includes Mr. Stitt and Sonny Rollins and some of the hardest trumpet

blowing ever recorded.

Through the 1960's and 70's, Mr. Gillespie

toured frequently, playing up to 300 shows a year, sometimes with an

electric bassist and a guitarist, sometimes with a more traditional

group. And in 1974 he signed with Pablo Records and began recording

prolifically again. He won Grammies in 1975 and 1980, and he published

his autobiography, "To Be or Not to Bop," in 1979.

In the last

decade, Mr. Gillespie's career seemed recharged, and he became

ubiquitous on the concert circuit as a special guest. He formed a Latin

big band that performed with Paquito De Rivera, among others, and he

constantly shuffled the personnel of his small groups.

Last year,

in honor of his 75th birthday, Mr. Gillepsie played for four weeks at

the Blue Note club in Manhattan, a stint that featured perhaps the

greatest selection of jazz musicians ever brought together for a

tribute. The month covered his career, from small groups, to Afro-Cuban

jazz to a big band. As usual, he was his witty amiable self, in command

of both the audience and his trumpet.

Mr. Gillespie is survived by his wife of 52 years, Lorraine.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/dizzy-gillespie/

Home » Jazz Musicians »

Dizzy Gillespie

He replaced Eldridge in the 'Teddy Hill' Band after Eldridge's departure. He eventually began experimenting and creating his own style which would eventually come to the attention of Mario Bauza, the Godfather of Afro-Cuban jazz who was then a member of the Cap Calloway Orchestra, joining Calloway in 1939, Gillespie was fired after two years when he cut a portion of the Calloway's buttocks with a knife after Calloway accused him of throwing spitballs (the two men later became lifelong friends and often retold this story with great relish until both of their deaths).

Although noted for his on and off-stage clowning, Gillespie endured as one of the founding fathers of the Afro-Cuban &/or Latin Hazz tradition. Influenced by Bauza, known as Gillespies musical father, he was able to fuse Afro-American jazz and Afro-Cuban rhythms to form a burgeoning CuBop sound. Always a musical ambassador, he toured Africa, the Middle East and Latin America under the sponsorship of the US State Department. Quite often he returned, not only with fresh musical ideas, but with musicians who would eventually go on the achieve world renown.

Among his proteges and collaborators are 'Chano Pozo'. the great Afro-Cuban percussionist; Danilo perez, a master pianist and composer originally from Pnama; Arturo Sandoval, trumpeter, composer and music educator originally from Cuba; Mongo Santamaria, an Afro-Cuban conguero, bongeuro and composer; David Sanchez, saxophonist and composer; Chucho Valdes, an Afro-Cuban virtuoso pianist and composer; and Bobby Sanabria, a Bronx, NY-born Nuyorican percussionist, composer, educator, bandleader and expert in the Afro-Cuban musical tradition. Indeed, many Latin jazz classics such as "Manteca", "A Night in Tunisia" and "Guachi Guaro [Soul Sauce]" were composed by Gillespie and his musical collaborators.

With a strong sense of pride in his Afro-American heritage, he left a legacy of musical excellence that embraced and fused all musical forms, but particularly those forms with roots deep in Africa such as the music of Cuba, other Latin American countries and the Caribbean. Additionally, he left a legacy of goodwill and good humor that infused jazz musicians and fans throughout the world with the genuine sense of jazz's ability to transcend national and ethnic boundaries—for this reason, Gillespie was and is an international treasure.

Awards

New Star Award, Esquire Magazine (1944); Handel Medallion, City of New York (1972); Paul Robeson Award, Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Studies (1972); Performs "Salt Peanuts" with President Carter at White House Jazz Concert (1978); Inducted into Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame (1982); Lifetime Achievement Award, National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) (1989); National Medal of Arts, President Bush (1989); Duke Ellington Award, Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (1989); Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1989); Kennedy Center Honors Award (1990); Fourteen honorary degrees, including Ph.D., Rutgers University (1972); Ph.D., Chicago Conservatory of Music (1978); Awarded a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Tags

Dizzy Gillespie

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (/ɡɪˈlɛspi/ gil-ESP-ee; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazztrumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer.[2] He was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuosic style of Roy Eldridge[3] but adding layers of harmonic and rhythmic complexity previously unheard in jazz. His combination of musicianship, showmanship, and wit made him a leading popularizer of the new music called bebop. His beret and horn-rimmed spectacles, scat singing, bent horn, pouched cheeks, and light-hearted personality have made him an enduring icon.[2]

In the 1940s, Gillespie, with Charlie Parker, became a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz.[4] He taught and influenced many other musicians, including trumpeters Miles Davis, Jon Faddis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Arturo Sandoval, Lee Morgan,[5] Chuck Mangione,[6] and balladeer Johnny Hartman.[7]

He pioneered Afro-Cuban jazz and won several Grammy Awards.[8] Scott Yanow wrote, "Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time, Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up being similar to those of Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis's emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated [....] Gillespie is remembered, by both critics and fans alike, as one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time".[9]

Biography

Early life and career

The youngest of nine children of Lottie and James Gillespie, Dizzy Gillespie was born in Cheraw, South Carolina.[10]His father was a local bandleader,[11] so instruments were made available to the children. Gillespie started to play the piano at the age of four.[12] Gillespie's father died when he was only ten years old. He taught himself how to play the trombone as well as the trumpet by the age of twelve. From the night he heard his idol, Roy Eldridge, on the radio, he dreamed of becoming a jazz musician.[13]

He won a music scholarship to the Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina which he attended for two years before accompanying his family when they moved to Philadelphia in 1935.[14][15]

Gillespie's first professional job was with the Frank Fairfax Orchestra in 1935, after which he joined the respective orchestras of Edgar Hayes and later Teddy Hill, replacing Frankie Newton as second trumpet in May 1937. Teddy Hill's band was where Gillespie made his first recording, "King Porter Stomp". In August 1937 while gigging with Hayes in Washington D.C., Gillespie met a young dancer named Lorraine Willis who worked a Baltimore–Philadelphia–New York City circuit which included the Apollo Theater. Willis was not immediately friendly but Gillespie was attracted anyway. The two married on May 9, 1940.[16]

Gillespie stayed with Teddy Hill's band for a year, then left and freelanced with other bands.[5] In 1939, with the help of Willis, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra.[14] He recorded one of his earliest compositions, "Pickin' the Cabbage", with Calloway in 1940. After an altercation between the two, Calloway fired Gillespie in late 1941. The incident is recounted by Gillespie and Calloway's band members Milt Hinton and Jonah Jones in Jean Bach's 1997 film, The Spitball Story. Calloway disapproved of Gillespie's mischievous humor and his adventuresome approach to soloing. According to Jones, Calloway referred to it as "Chinese music". During rehearsal, someone in the band threw a spitball. Already in a foul mood, Calloway blamed Gillespie, who refused to take the blame. Gillespie stabbed Calloway in the leg with a knife. Calloway had minor cuts on the thigh and wrist. After the two were separated, Calloway fired Gillespie. A few days later, Gillespie tried to apologize to Calloway, but he was dismissed.[17]

During his time in Calloway's band, Gillespie started writing big band music for Woody Herman and Jimmy Dorsey.[5]He then freelanced with a few bands, most notably Ella Fitzgerald's orchestra, composed of members of the Chick Webb's band.

Gillespie did not serve in World War II. At his Selective Service interview, he told the local board, "in this stage of my life here in the United States whose foot has been in my ass?" and "So if you put me out there with a gun in my hand and tell me to shoot at the enemy, I'm liable to create a case of 'mistaken identity' of who I might shoot." He was classified 4-F.[18][19] In 1943, he joined the Earl Hines band. Composer Gunther Schuller said,

... In 1943 I heard the great Earl Hines band which had Bird in it and all those other great musicians. They were playing all the flatted fifth chords and all the modern harmonies and substitutions and Gillespie runs in the trumpet section work. Two years later I read that that was 'bop' and the beginning of modern jazz ... but the band never made recordings.[20]

Gillespie said of the Hines band, "[p]eople talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit."[21]

Gillespie joined the big band of Hines' long-time collaborator Billy Eckstine, and it was as a member of Eckstine's band that he was reunited with Charlie Parker, a fellow member. In 1945, Gillespie left Eckstine's band because he wanted to play with a small combo. A "small combo" typically comprised no more than five musicians, playing the trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass and drums.

Rise of bebop

Bebop was known as the first modern jazz style. However, it was unpopular in the beginning and was not viewed as positively as swing music was. Bebop was seen as an outgrowth of swing, not a revolution. Swing introduced a diversity of new musicians in the bebop era like Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, and Gillespie. Through these musicians, a new vocabulary of musical phrases was created. With Parker, Gillespie jammed at famous jazz clubs like Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House. Parker's system also held methods of adding chords to existing chord progressions and implying additional chords within the improvised lines.

After his work with Parker, Gillespie led other small combos (including ones with Milt Jackson, John Coltrane, Lalo Schifrin, Ray Brown, Kenny Clarke, James Moody, J.J. Johnson, and Yusef Lateef) and put together his successful big bands starting in 1947. He and his big bands, with arrangements provided by Tadd Dameron, Gil Fuller, and George Russell, popularized bebop and made him a symbol of the new music.[24]

His big bands of the late 1940s also featured Cuban rumberos Chano Pozo and Sabu Martinez, sparking interest in Afro-Cuban jazz. He appeared frequently as a soloist with Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic.

Gillespie and his Bee Bop Orchestra was the featured star of the 4th Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles which was produced by Leon Hefflin, Sr. on September 12, 1948.[25] The young maestro had recently returned from Europe where his music rocked the continent. The program description noted "the musicianship, inventive technique, and daring of this young man has created a new style, which can be defined as off the chord solo gymnastics." Also on the program that day were Frankie Laine, Little Miss Cornshucks, The Sweethearts of Rhythm, The Honeydrippers, Big Joe Turner, Jimmy Witherspoon, The Blenders, and The Sensations.[26]

In 1948, Gillespie was involved in a traffic accident when the bicycle he was riding was bumped by an automobile. He was slightly injured and found that he could no longer hit the B-flat above high C. He won the case, but the jury awarded him only $1000 in view of his high earnings up to that point.[27]

In 1951, Gillespie founded his record label, Dee Gee Records; it closed in 1953.[28]

On January 6, 1953, he threw a party for his wife Lorraine at Snookie's, a club in Manhattan, where his trumpet's bell got bent upward in an accident, but he liked the sound so much he had a special trumpet made with a 45 degree raised bell, becoming his trademark.

In 1956 Gillespie organized a band to go on a State Department tour of the Middle East which was well-received internationally and earned him the nickname "the Ambassador of Jazz".[29][30] During this time, he also continued to lead a big band that performed throughout the United States and featured musicians including Pee Wee Moore and others. This band recorded a live album at the 1957 Newport jazz festival that featured Mary Lou Williams as a guest artist on piano.

Afro-Cuban jazz

In the late 1940s, Gillespie was involved in the movement called Afro-Cuban music, bringing Afro-Latin Americanmusic and elements to greater prominence in jazz and even pop music, particularly salsa. Afro-Cuban jazz is based on traditional Afro-Cuban rhythms. Gillespie was introduced to Chano Pozo in 1947 by Mario Bauza, a Latin jazz trumpet player. Chano Pozo became Gillespie's conga drummer for his band. Gillespie also worked with Mario Bauza in New York jazz clubs on 52nd Street and several famous dance clubs such as the Palladium and the Apollo Theater in Harlem. They played together in the Chick Webb band and Cab Calloway's band, where Gillespie and Bauza became lifelong friends. Gillespie helped develop and mature the Afro-Cuban jazz style. Afro-Cuban jazz was considered bebop-oriented, and some musicians classified it as a modern style. Afro-Cuban jazz was successful because it never decreased in popularity and it always attracted people to dance.[31]

Gillespie's most famous contributions to Afro-Cuban music are "Manteca" and "Tin Tin Deo" (both co-written with Chano Pozo); he was responsible for commissioning George Russell's "Cubano Be, Cubano Bop", which featured Pozo. In 1977, Gillespie met Arturo Sandoval during a jazz cruise to Havana.[32] Sandoval toured with Gillespie and defected in Rome in 1990 while touring with Gillespie and the United Nations Orchestra.[33]

Final years

In the 1980s, Gillespie led the United Nations Orchestra. For three years Flora Purim toured with the Orchestra. She credits Gillespie with improving her understanding of jazz.[34]

In 1982, he was sought out by Motown musician Stevie Wonder to play his solo in Wonder's 1982 hit single, "Do I Do".

He starred in the film The Winter in Lisbon that was released as El invierno en Lisboa in 1992 and re-released in 2004.[35] The soundtrack album, featuring him, was recorded in 1990 and released in 1991. The film is a crime drama about a jazz pianist who falls for a dangerous woman while in Portugal with an American expatriate's jazz band.

In December 1991, during an engagement at Kimball's East in Emeryville, California, he suffered a crisis from what turned out to be pancreatic cancer. He performed one more night but cancelled the rest of the tour for medical reasons, ending his 56-year touring career. He led his last recording session on January 25, 1992.

On November 26, 1992, Carnegie Hall, following the Second Baháʼí World Congress, celebrated Gillespie's 75th birthday concert and his offering to the celebration of the centenary of the passing of Baháʼu'lláh. Gillespie was to appear at Carnegie Hall for the 33rd time. The line-up included Jon Faddis, James Moody, Paquito D'Rivera, and the Mike Longo Trio with Ben Brown on bass and Mickey Roker on drums. Gillespie was too unwell to attend. "But the musicians played their real hearts out for him, no doubt suspecting that he would not play again. Each musician gave tribute to their friend, this great soul and innovator in the world of jazz."[36]

Death and postmortem

A longtime resident of Englewood, New Jersey,[37] Gillespie died of pancreatic cancer on January 6, 1993, at the age of 75 and was buried in Flushing Cemetery, Queens, New York City. Mike Longo delivered a eulogy at his funeral.

Politics and religion

In 1962, Gillespie and actor George Mathews starred in The Hole, an animated short film by John and Faith Hubley. Released the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis, it uses audio from an improvised conversation between the two debating the causes of accidents and the possibility of accidentally launching nuclear weapons. The short went on to win the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film the following year.[38]

During the 1964 United States presidential campaign, Gillespie put himself forward as an independent write-in candidate.[39][40] He promised that if he were elected, the White House would be renamed the Blues House, and he would have a cabinet composed of Duke Ellington (Secretary of State), Miles Davis (Director of the CIA), Max Roach(Secretary of Defense), Charles Mingus (Secretary of Peace), Ray Charles (Librarian of Congress), Louis Armstrong(Secretary of Agriculture), Mary Lou Williams (Ambassador to the Vatican), Thelonious Monk (Travelling Ambassador) and Malcolm X (Attorney General).[41][42] He said his running mate would be Phyllis Diller. Campaign buttons had been manufactured years before by Gillespie's booking agency as a joke[43] but proceeds went to Congress of Racial Equality, Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King Jr.;[44] in later years they became a collector's item.[45] In 1971, he announced he would run again[46][47] but withdrew before the election.[48]

Shortly after the death of Charlie Parker, Gillespie encountered an audience member after a show. They had a conversation about the oneness of humanity and the elimination of racism from the perspective of the Baháʼí Faith. Impacted by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, he became a Baháʼí that same year.[49][50] The universalist emphasis of his religion prodded him to see himself more as a global citizen and humanitarian, expanding on his interest in his African heritage. His spirituality brought out generosity and what author Nat Hentoff called an inner strength, discipline, and "soul force".[51]

Gillespie's conversion was most affected by Bill Sears' book Thief in the Night.[49] Gillespie spoke about the Baháʼí Faith frequently on his trips abroad.[52][53][54] He is honored with weekly jazz sessions at the New York Baháʼí Center in the memorial auditorium.[55]

Personal life

Gillespie married dancer Lorraine Willis in Boston on May 9, 1940.[14] They remained together until his death in 1993; Lorraine converted to Catholicism with Mary Lou Williams in 1957.[16][56] Lorraine managed his business and personal affairs.[57] The couple had no children, but Gillespie fathered a daughter, jazz singer Jeanie Bryson, born in 1958 from an affair with songwriter Connie Bryson.[58][59] Gillespie met Bryson, a Juilliard-trained pianist, at the jazz club Birdland in New York City.[59] In the mid-1960s, Gillespie settled down in Englewood, New Jersey, with his wife.[60] The local Englewood public high school, Dwight Morrow High School, named its auditorium after him: the 'Dizzy Gillespie Auditorium'.[61][62]

Artistry

Style

Gillespie has been described as the "sound of surprise".[51] The Rough Guide to Jazz describes his musical style:

The whole essence of a Gillespie solo was cliff-hanging suspense: the phrases and the angle of the approach were perpetually varied, breakneck runs were followed by pauses, by huge interval leaps, by long, immensely high notes, by slurs and smears and bluesy phrases; he always took listeners by surprise, always shocking them with a new thought. His lightning reflexes and superb ear meant his instrumental execution matched his thoughts in its power and speed. And he was concerned at all times with swing—even taking the most daring liberties with pulse or beat, his phrases never failed to swing. Gillespie's magnificent sense of time and emotional intensity of his playing came from childhood roots. His parents were Methodists, but as a boy he used to sneak off every Sunday to the uninhibited Sanctified Church. He said later, "The Sanctified Church had deep significance for me musically. I first learned the significance of rhythm there and all about how music can transport people spiritually."[63]

In Gillespie's obituary, Peter Watrous describes his performance style:

In the naturally effervescent Mr. Gillespie, opposites existed. His playing—and he performed constantly until nearly the end of his life—was meteoric, full of virtuosic invention and deadly serious. But with his endlessly funny asides, his huge variety of facial expressions and his natural comic gifts, he was as much a pure entertainer as an accomplished artist.[2]

Wynton Marsalis summarized Gillespie as a player and teacher:

"His playing showcases the importance of intelligence. His rhythmic sophistication was unequaled. He was a master of harmony—and fascinated with studying it. He took in all the music of his youth—from Roy Eldridge to Duke Ellington—and developed a unique style built on complex rhythm and harmony balanced by wit. Gillespie was so quick-minded, he could create an endless flow of ideas at unusually fast tempo. Nobody had ever even considered playing a trumpet that way, let alone had actually tried. All the musicians respected him because, in addition to outplaying everyone, he knew so much and was so generous with that knowledge..."[64]

Bent trumpet

Gillespie's trademark trumpet featured a bell which bent upward at a 45-degree angle rather than pointing straight ahead as in the conventional design. According to Gillespie's autobiography, this was originally the result of accidental damage caused by the dancers Stump and Stumpy falling onto the instrument while it was on a trumpet stand on stage at Snookie's in Manhattan on January 6, 1953, during a birthday party for Gillespie's wife Lorraine.[65] The constriction caused by the bending altered the tone of the instrument, and Gillespie liked the effect. He had the trumpet straightened out the next day, but he could not forget the tone. Gillespie sent a request to Martin to make him a "bent" trumpet from a sketch produced by Lorraine, and from that time forward played a trumpet with an upturned bell.[66]

By June 1954 he was using a professionally manufactured horn of this design, and it was to become a trademark for the rest of his life.[51]: 258–259 Such trumpets were made for him by Martin (from 1954), King Musical Instruments (from 1972) and Renold Schilke (from 1982, a gift from Jon Faddis).[66] Gillespie favored mouthpieces made by Al Cass. In December 1986 Gillespie gave the National Museum of American History his 1972 King "Silver Flair" trumpet with a Cass mouthpiece.[66][67]

In April 1995, Gillespie's Martin trumpet was auctioned at Christie's in New York City with instruments used by Coleman Hawkins, Jimi Hendrix, and Elvis Presley.[68] An image of Gillespie's trumpet was selected for the cover of the auction program. The battered instrument was sold to Manhattan builder Jeffery Brown for $63,000, the proceeds benefiting jazz musicians with cancer.[69][70][71]

In 1989, Gillespie was given the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The next year, at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts ceremonies celebrating the centennial of American jazz, Gillespie received the Kennedy Center Honors Award and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers Duke Ellington Award for 50 years of achievement as a composer, performer, and bandleader.[72][73]

In 1989, Gillespie was awarded with an honorary doctorate of music from Berklee College of Music.[74]

In 1991, Gillespie received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member Wynton Marsalis.[75]

In 1993 he received the Polar Music Prize in Sweden.[76] In 2002, he was posthumously inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame for his contributions to Afro-Cuban music.[77] He was honored on December 31, 2006 in A Jazz New Year's Eve: Freddy Cole & the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[78] In 2014, Gillespie was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.[79]

In popular culture

Samuel E. Wright played Dizzy Gillespie in the film Bird (1988), about Charlie Parker.[80] Kevin Hanchard portrayed Gillespie in the Chet Baker biopic Born to Be Blue (2015).[81] Charles S. Dutton played him in For Love or Country: The Arturo Sandoval Story (2000).

List of works

Main article: List of works by Dizzy Gillespie

See also

Biography portal

Biography portal Jazz portal

Jazz portalExternal links:

Interview with Les Tomkins in 1973

Articles at NPR Music

Short biography by C.J. Shearn

Dizzy Gillespie Showcase

Seeking the Best Of a Huge Output

Dizzy Gillespie's recorded output was immense, spanning nearly 60 years and comprising hundreds of albums. Not all of his important recordings have been issued on CD, but the vinyl versions are worth hunting for.

Afro Cuban Jazz Verve

The Be-Bop Revolution RCA

Bird and Diz Verve

The Development of an American Artist Smithsonian

Diz and Getz Verve

Dizzy and the Double Six of Paris Phillips

Dizzy at Newport Verve

Dizzy on the French Riviera Phillips

Dizzy's Diamonds Verve

Duets Verve

The Gifted Ones (with Roy Eldridge) Pablo

Live at the Royal Festival Hall Enja

Oscar Peterson and Dizzy Gillespie Pablo

Portrait of Duke Ellington Verve

Shaw Nuff Musicraft

Sonny Side Up (with Sonny Stitt) Verve

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/dizzy-gillespie-mn0000162677/biography

Dizzy Gillespie

Active: 1930s - 1990s

Born: October 21, 1917 in Cheraw, SC

Died: January 6, 1993 in Englewood, NJ

Genre: Jazz

Styles: Afro-Cuban Jazz Bop Vocal Jazz World Fusion Big Band Jazz Instrument Trumpet Jazz

Also Known As:

John "Dizzy" Gillespie

John Birks 'Dizzy' Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie

John Birks Gillespie

John Gillespie

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

http://www.openculture.com/2012/10/dizzy_gillespie_runs_for_us_president_1964_.html

Dizzy Gillespie Runs for US President, 1964.October 1st, 2012

OPEN CULTURE

A take on his trademark tune “Salt Peanuts,” “Vote Dizzy” was Gillespie’s official campaign song and includes lyrics like:

Your politics ought to be a groovier thing

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

So get a good president who’s willing to swing

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

It’s definitely groovier than either one of our current campaigns. Dizzy “believed in civil rights, withdrawing from Vietnam and recognizing communist China,” and he wanted to make Miles Davis head of the CIA, a role I think would have suited Miles perfectly. Although Dizzy’s campaign was something of a publicity stunt for his politics and his persona, it’s not unheard of for popular musicians to run for president in earnest. In 1979, revolutionary Nigerian Afrobeat star Fela Kuti put himself forward as a candidate in his country, but was rejected. More recently, Haitian musician and former Fugee Wyclef Jean attempted a sincere run at the Haitian presidency, but was disqualified for reasons of residency. It’s a little hard to imagine a popular musician mounting a serious presidential campaign in the U.S., but then again, the 80s were dominated by the strange reality of a former actor in the White House, so why not? In any case, revisiting Dizzy Gillespie’s mid-century political theater may provide a needed respite from the onslaught of the current U.S. campaign season.

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.

http://www.popmatters.com/review/gillespiedizzy-career1937/

Dizzy Gillespie

Career: 1937-1992

by Will Layman

26 May 2005

PopMatters

Dizzy Gillespie is the greatest post-war musician never to make a truly great album.

Before

bebop, of course, musicians did not make “albums”, but merely 78 RPM

singles. They recorded these “sides” in batches certainly, but they were

not conceived of as groups of songs, and so the great recordings of

Armstrong, Ellington, and Hawkins were released piecemeal and today are

collected in anthologies that we think of as “great albums.” But Dizzy

Gillespie’s contemporaries in the bop movement each birthed a collection

of songs that has become representative of their genius—Parker, Monk,

Bud Powell, and Miles Davis all made untouchable albums. In the next

generation such a feat was essentially required for the greats such as

Sonny Rollins (Saxophone Colossus) and John Coltrane (Giant Steps).

Dizzy

was as great a musician as any of these figures. Only Pops, Duke, and

Trane rival him in importance, and no one—even Armstrong—can touch him

as a pure trumpet player. It seems almost a paradox then that a musician

who recorded throughout a career that lasted until the early 1990s

never made a brilliant album. A handful of Gillespie platters were

memorable—Sonny Side Up, Swing Low Sweet Cadillac, Dizzy’s Big Four—and

of course he made a few classics with Charlie Parker. But Dizzy’s is a

career of innovation, consistency, humor, intelligence, and

integrity—but it’s also a career without a single shining moment.

All

of this makes Shout Factory’s Career compilation a grand slam—an

essential career retrospective from one of the 20th century giants of

American music. The lack of a single must-have album from The Diz makes

this two-disc set more than just good and better than great. This is

theGillespie collection on the market today.

Career is so good

because it collects highlights from nearly every phase of Dizzy’s

storied career. For those who don’t know the Gillespie legacy, this

collection lays it out, tune by tune. Dizzy started as a bright, crazy

young trumpet star in the better big bands of the late 1930s. Here, we

catch him with Teddy Hill on “King Porter Stomp” (1937), Cab Calloway on

his own composition “Pickin’ the Cabbage” (1940), and then with the

great Billy Eckstine band from 1944. Diz is clearly a disciple of Roy

Eldridge in these early recordings, but the seeds of his own style are

in evidence—an ease in the upper register and a penchant for

chromaticism as he easily glides from chord to chord.

Dizzy’s

career as an innovator, however, really takes off in the small group

sides from the mid-‘40s. Career gives us seven sextet recordings from

1945 and ‘46 that show how Dizzy conceived of a bebop sound that came

out of swing as much as reacted against it. The version of “I Can’t Get

Started” included here is hardly boppish, with a very bland

accompaniment, but you can hear Dizzy finding the most interesting notes

from the harmony in building his solo. Only two months later, on

“Groovin’ High”, Dizzy is teamed up with Charlie “Yardbird” Parker and

the sparks are genuinely flying—with the two horns playing the unison

head in perfect synch and Dizzy’s muted solo suggesting the puckish

humor that would always be part of his style. The three tracks with this

line-up (also featuring Slam Stewart on bass and Cozy Cole’s drums) are

stone gems, none better than “Dizzy Atmosphere”, where the flow from

Bird’s solo to Dizzy demonstrates why Dizzy said of Parker, “He is the

other half of my heartbeat.”

While Dizzy’s small group work is

justifiably famous, he did not abandon the big band sound as he was

helping to invent bebop. Here, we get a heaping dose of Dizzy’s

late-‘40s big band—particularly the sides that introduced the concept of

Afro-Cuban jazz, featuring Chano Pozo on congas. “Cubano Be/Cubano Bop”

and “Manteca” are diamonds that haven’t stopped shimmering in 60

years—brilliant essays in rhythm and arrangement (credited to George

Russell and Gil Fuller) that still scream out of your speakers at full

throttle. Dizzy’s lead on “Manteca” is one of the great sounds in

American music.

When Dizzy returned to small group recordings in

the 1950s, the bebop sound was no longer a scandal. “Bloomdido” is

essentially from an all-star session with Diz, Bird, Thelonious Monk on

piano, Curly Russell on bass and Buddy Rich on drums. There’s nothing to

say about music this good other than: listen to it. Dizzy’s solos here,

on “Birk’s Works” with Milt Jackson, and on the two tracks from the

all-star concert with Bird, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus and Max Roach

(“Salt Peanuts” and “Perdido”) are the pinnacle of jazz trumpet

playing—virtuosic, subtle, sliding, blue, declamatory and fiendishly

clever. It is standing ovation stuff, and don’t be surprised if you find

yourself getting to your feet in your living room.

Disc Two of

Career moves us into the more workmanlike stage of Dizzy’s career. Like a

great physicist, Dizzy did his groundbreaking work early, but the

career that followed was special if not consistently revolutionary.

During this period, Dizzy recorded a great deal for Norman Grantz’s

Verve label, appearing often with “special guests.” The “It Don’t Mean a

Thing” included here, with Stan Getz, Roach, and the Oscar Peterson

Trio, is a fine example of this kind of one-off meeting working

wonderfully well for Dizzy. His solo is like scrambled eggs and

salsa—whirling and hot as steam. The “Mean to Me” (1956)with Sonny Stitt

and John Lewis shows a more conversational side of Diz, as he cools it,

despite a double-time break at the start of this solo that reminds you

how much fuel he has in the tank even on a medium swinger.

The

later big band recordings are remarkable for their young star line-ups

(Lee Morgan, Melba Liston, Al Grey, Benny Golson, Wynton Kelly, among

others) and punch. Another from 1975 with Machito’s big band shows that,

even late in his career, Dizzy was essentially a lead trumpeter with a

bebop soul, riding over an electric bass and team of percussion. Disc

Two also features an early ‘60s working group with Lalo Schiffrin on

piano that was typical of some of the more faceless bands that Dizzy

lead in the latter part of his career, but darn if they aren’t extremely

hot recordings, demonstrating that Dizzy was a brilliant bandleader

even when his talent was less than top-shelf.

Dizzy performed

consistently for more than a half-century and, while this set properly

focuses on the ‘40s and ‘50s, it includes two tracks from the great

trumpeter’s twilight. “Wheatleigh Hall” pairs him with Cuban disciple

Arturo Sandoval. Dizzy’s adoption of Cuban music made him a hero on the

island, and Sandoval was one of many Cubans who owe their jazz careers

to the Diz. But, as a trumpeter, Sandoval will always be Dizzy’s

inferior, even on this 1982 track. The best of Dizzy’s imitators

realized that, like Miles Davis, you could apprentice in Dizzy’s

high-flying style but it was better to stake out your own ground

artistically. Sandoval is a brassy imitation without nearly the humor

and sly wit that Dizzy brings to even this late date.

The final

track on Career is a tribute date recorded shortly before Dizzy left us

to join Bird, Monk, Duke and Pops up above. Dizzy lived one of the

longest and most productive lives in jazz. He was and is the role model

for young guys in the music—no drug use, married for a half century to

one woman, a good businessman, and incomparable combination of showman

and artist. In this last recording, he’s frail, and the musician

accompanying him surely knew it. But it hardly matters. The group plays

the iconic tune “Bebop”—of course, Dizzy wrote it—and when it’s time for

the master to take his turn everyone sets a smooth, swinging table for

him.

He fumbles some, and the tone is hardly what it once was,

but Dizzy still skitters over the changes with grace, a brilliant

musical mind picking out the hip notes as it constructs one of his final

solos. There’s nothing sad about it—because Dizzy’s life was one of the

greatest solos of all.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Will

Layman is a writer, teacher and musician living in the Washington, DC

area. He is a contributor to National Public Radio and frequently

appears as a guest on WNYC's "Soundcheck" as a jazz critic. He plays

both funk and jazz in the bars and clubs in and near the nation's

capital. His fiction and humor appear in print and online.

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/john-birks-dizzy-gillespie

http://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/07/arts/dizzy-gillespie-stays-put-but-not-for-long.html

Dizzy Gillespie Stays Put, but Not for Long

by PETER WATROUS

January 7, 1992

New York Times

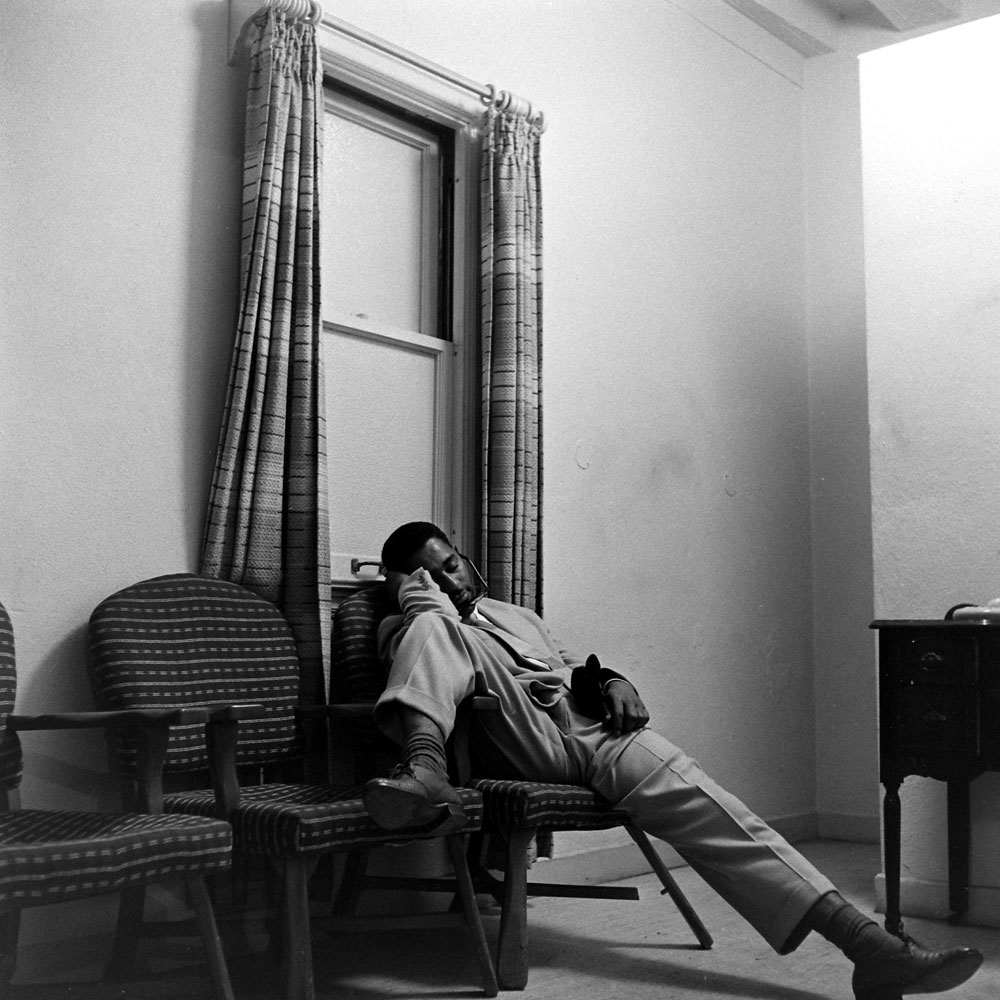

Over the next month, Dizzy Gillespie will probably wade through "A Night in Tunisia" 50 more times. Considering that he's been playing the tune twice a night, 300 nights a year for the last 50 or so years, another 50 times won't mean a thing. The idea doesn't seem to bother him.

"Even 'Night in Tunisia,' doesn't bore me; I'm never bored," Mr. Gillespie said on Sunday afternoon before rushing off to perform "The Star-Spangled Banner" at the Knicks game at Madison Square Garden. "There's always a new way to play anything."

What makes these last 50 so unusual is that Mr. Gillespie, one of the fathers of be-bop and an icon of jazz, will be playing them in the same place for a month. He is booked at the Blue Note in Greenwich Village, where 30 to 40 musicians both perform with him and pay tribute to him.

It's part of a yearlong celebration of Mr. Gillespie's 75th birthday, which will be on Oct. 21. He will also appear in Latin America, Europe and South Africa (in an appearance approved by Nelson Mandela), and this month he will release "The Winter in Lisbon," in which he stars. So the Blue Note performances are a good time to see and hear the country's best-known trumpet player amid rare musical splendor. Mr. Gillespie, who flies over 300,000 miles a year, doesn't stay in one place too long. Going Way Back

The first week begins tonight and brings together an extraordinary group of musicans: Jimmy Heath on saxophone, Slide Hampton on trombone, Kenny Barron on piano, Bob Cranshaw on bass and Elvin Jones on drums. They have all, with the exception of Mr. Jones, put in their time under Mr. Gillespie's leadership.

Mr. Gillespie's pleasure in the group makes him grope for words. "Owww, that group is good," he said over lunch in a midtown restaurant. "I've been playing with Kenny since he was a little kid, and he and Jimmy know how I think better than I do. Cranshaw has a beat like a gorilla. And I want Elvin to play like he usually does, hard."

For Mr. Heath, who first joined Mr. Gillespie's big band in the early 1940's, the show will be a homecoming.

"Diz is my guru, my teacher," Mr. Heath said. "When I joined his band, after being in love with his and Charlie Parker's music, it was a dream come true. My brother Percy and I had followed the band around. We were even wearing his costume, berets and thin artist ties. It was a school in arranging and composing and true improvisation because Dizzy never played the same thing in the same place."

Mr. Heath said he and John Coltrane, who was also in the band, would note the way the trumpeter introduced his solo in "I Can't Get Started."

"He'd play it differently each time and we'd look at each other in amazement," Mr. Heath recalled. "In that period he was far superior to anybody that played trumpet, anybody. Dizzy was the master." His Own Band

The second week at the Blue Note will feature Mr. Gillespie's 13-piece Afro-Cuban jazz band, the United Nation Orchestra, which includes the saxophonist Paquito D'Rivera, the trumpeter Claudio Roditi, the percussionist Giovanni Hidalgo, the saxophonist Mario Rivera, the drummer Charli Persip and the pianist Danilo Perez, Latin musicians who, Mr. Gillespie says, "love our music more than the original be-boppers."

"These guys play be-bop better than be-bop guys play Latin," he said, "but it's the mixture that I like. I love playing it. I'm not an authority, but I know it pretty well. I love the rhythm."

The third week has a slew of saxophonists, including a handful of younger players: Tim Warfield, David Sanchez, Vincent Herring, Antonio Hart -- to balance out the older masters. Benny Golson will appear, as will Jackie McLean, Clifford Jordan, David (Fathead) Newman, Hank Crawford and more.

For Jackie McLean, a member of one of the first groups of young musicians to absorb the lessons of Mr. Gillespie and Charlie Parker, the show is a way of getting closer to the source. "I first heard Dizzy and Bird on a tune called 'Sorta Kinda' on a record by Trummy Young, and then two days later I heard them on 'Koko,' " recalled Mr. McLean, who has begun to play occasionally with Mr. Gillespie at festivals and concerts. "I had heard all sorts of great music as a kid, but when I heard them I locked in and I knew what I wanted to say.

"Dizzy's one of my greatest heroes and idols. I've hungered to play with him and I couldn't be more motivated by the chance. Historically he belongs to the special club of only five trumpeters -- Buddy Bolden, Freddy Kepperd, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong and Dizzy. I'm so happy he's alive and reigning. As long as he's here, he's the king." Other Trumpeters

For his final week, Mr. Gillespie will be joined by trumpeters, including one of his first disciples, Red Rodney, his protege Jon Faddis and the be-bop trumpeter Donald Byrd. Doc Cheatham, who played along side Mr. Gillespie in Cab Calloway's orchestra, will be there, too, along with some of the better young trumpeters now on the jazz scene, Wynton Marsalis, Wallace Roney, Roy Hargrove and Terence Blanchard.

Like many younger musicians, Mr. Hargove has been on the receiving end of Mr. Gillespie's advice, musical or otherwise.

"Dizzy is my musical father," said the 21-year-old Mr. Hargrove. "Every time I see him, he has some advice about playing or on life in general. I hope I can play that much trumpet when I'm his age, because he's playing more than a lot of cats my age. His harmonic sense, the way he plays over chords, especially now, is on a really sophisticated level. He's definitely kept progressing, which is inspirational."

And through it all will be the clowning. Had Mr. Gillespie quit performing in 1950, he'd be remembered as an enormously influential and productive musician, someone who affected a sea change in American music with his innovations. But even before that Mr. Gillespie had done something more difficult. By mixing an infallible sense of humor with music, he had managed to combine serious expression with entertainment. With his trademark moon cheeks and his bent trumpet, he has become one of the country's most recognizable figures.

"I never looked behind me to find out what other people were playing or doing," Mr. Gillespie said. "I always liked a little fun. Charlie Parker was pretty funny himself. One time in Pine Bluff, Ark., a guy hit me in the head with a bottle. Charlie said, 'You took advantage of my friend, you cur.' I had to laugh even through I had blood coming out of my head. That's just the way I felt about it. It didn't bother me what everybody else was doing. I got fired out of Cab Calloway's band for fooling around too much. It still didn't bother me." The Schedule At the Blue Note

Here is the schedule of Dizzy Gillespie programs at the Blue Note, 131 West Third Street in Manhattan. For reservations, call (212) 475-8592.

JAN. 7-12, "Dizzy's Be-Bop Jamboree," with Kenny Barron, Bob Cranshaw, Slide Hampton, Jimmy Heath, Elvin Jones and James Moody.

JAN. 14-19, "Dizzy's United Nation," with Paquito D'Rivera, Ed Cherry, Danilo Perez, Charli Persip, Mario Rivera and David Sanchez, among others.

JAN. 21-26, "To Bird, With Love," with different guests each night, including Hank Crawford, Benny Golson, Jackie McLean, Clifford Jordan and David (Fathead) Newman.

JAN. 28-FEB. 2, "To Diz, With Love," with guest artists including Roy Hargrove, Wynton Marsalis, Doc Cheatham, Donald Byrd, Red Rodney and Jon Faddis.

Photo: "I never looked behind me to find out what other people were playing or doing," said Dizzy Gillespie, who is shown in Manhattan on Sunday. (David Gahr for The New York Times)

http://abartists.nyc/2015/07/21/the-dizzy-gillespie-tm-afro-cuban-experience/

The Dizzy Gillespie (TM) Afro Cuban Experience

The musicians are drawn from the high-calibre pool of New York-based talent that frequent the Dizzy Gillespie™ Big Band and All Star groups, such as trumpeter Freddie Hendrix, saxophonist Sharel Cassity, Brazilian pianist / vocalist Abelita Mateus, drummer Tommy Campbell and percussionist Roger Squitero. They perform with energy, verve, and style, putting their own fresh stamp on a well-known genre. The group can perform as various sizes from sextet to octet.

POP VIEW

by Peter Watrous

January 17, 1993

New York Times

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was an easy person to get hold of, if he was in this country, which wasn't often. It just took a telephone call and he'd speak with you, laconic and interested if you knew what you were talking about, monosyllabic if you didn't. Searching for answers to a musical question or for an eyewitness report on some of the more important cultural history of the 20th century would incite two types of replies -- the "Umm, yeah . . ." sort, a bit gruff, mostly bored, and obviously the response of a person watching television, or an articulate expression of what he had experienced in the course of a life that moved from rural South Carolina to the streets of the major cities of the world.

Nearly 60 years of involvement in show business in America left Gillespie, who died this month at age 75, a profound judge of character, somebody who had seen just about every type of scam, malfeasance and insincerity. An unprepared interviewer would turn into prey, and many were left with nothing. He had been burned in print before -- a long profile in The New Yorker in 1948 poked fun at him and be-boppers. He spent a good portion of the late 1950's and early 1960's a lost figure in a music he helped invent; be-bop was yesterday's music.

Being innovative in America isn't easy, especially when taking the route Gillespie chose, but the difficulties clearly helped form his immensely complicated personality. Partly his problems were of his own making: in presenting himself as both an entertainer and a brilliant musician, he was bound to be treated badly by people who were looking for either simple fun or art. For decades he was asked the same questions: Why did be-bop have such a funny name? What was Charlie Parker like?

Gillespie was expected to be witty and to maintain his stage persona even in private. He felt he was constantly under suspicion because of his race, constantly treated like a jester; the experience could have left scars. Be-bop itself, his own hard-won creation, had met with divisiveness, and its practitioners were often accused of ignoring audiences, fostering an elitist sensibility.

But Gillespie spent most of his time, oddly enough, being anything but divisive. His performances were about as inclusionary and unpatronizing as any in the history of American music, and he never excluded anyone. To his friends he was forthcoming and warm, and to other musicians he was a deity, always willing to sit down at the piano and share some of his copious insights. The writer Stanley Crouch remembers an occasion when Gillespie went to a black studies center in 1970 with a white friend and, after being challenged by the participants, stated flatly, "This is my brother."

His opened-armed affability reigned on stage. Charismatic personalities can coerce a club or concert hall, change its mood, and Gillespie regularly turned a nightclub or concert into his room, a place where absurdity and humor walked easily with musical excellence. The persona he created for the audience was full of mock aristocratic accents, raised eyebrows, gentle prods toward unruly or insensitive fans. He rid the air of pretensions; this from one of the more profound musicians to grace American music. He would begin a show by asking the audience if he could introduce the band; after people shouted yes, he would introduce the band members to one another. It suckered the audience, but in an unmalicious way, and automatically sealed a contract with the audience, showing that the audience played a role in the show.

What ensued musically during a show was, until the last few years of his life, always extraordinary. Gillespie embraced urbanity and turned the vitality of the metropolis into something enriching instead of something causing fear and despair. It is fascinating to listen to Gillespie and Charlie Parker together, to hear how Parker's use of narrative is more ordered, more calm and rural; it seems to come from an earlier period. In the tune "Dizzy Atmosphere," from 1945, for example, Gillespie's improvisations are radical in their sense of juxtaposition; they reproduce the extremes and velocity of urban life. Gillespie was a master of dynamics; he would let out shouts and follow them with a run, a whisper and a sudden burst of notes.

Jazz is often called the sound of surprise; in his hands, it was the sound of shock. And while he recorded perfectly logical improvisations over his career, his most personal improvisations were the ones in which the internal contrasts, jagged and sharp, always argued in favor of a literate conception of artistic activity. With their abrupt movements and bright flashes of sounds, Gillespie's solos were the sound of modernism, the relentless and erratic motion of a city in action.

His artistic legacy covered more ground than that of any other jazz musician aside from Duke Ellington. His small group recordings were definitive; his experiments with big bands and Afro-Cuban music gave the second half of his century a good portion of its musical profile. This was a man who well into his 70's regularly changed band members, and bands, moving easily between the Latin world and the jazz world, a man who frequently showed up as a special guest and charged the mood of concert hall after concert hall, reaping standing ovations around the world.

Nearly a year ago, Gillespie said in an interview: "I never looked behind me to find out what other people were playing or doing. I just keep going, looking for new ideas, practicing. Even a 'Night in Tunisia' doesn't bore me; I'm never bored. There's always a new way to play anything." That pretty much summed up his 60 years of change.

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on October 21, 2014):

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

IN CELEBRATION OF THE ART AND LIFE OF LEGENDARY MUSICIAN AND COMPOSER JOHN BIRKS 'DIZZY' GILLESPIE (1917-1993) ON HIS 97th BIRTHDAY

Saturday, October 17, 2015

JOHN BIRKS "DIZZY" GILLESPIE (1917-1993): Legendary, iconic, and innovative musician, composer, arranger, ensemble leader, music theorist, and teacher

All,

October 21, 2017 marks the centennial of the birth of John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (b. October 21, 1917) one of the greatest as well as most influential and inspiring musicians and composers of the 20th century who had a profound global impact on music and art and played a crucial role in the growth and development of modern music generally in a critically acclaimed career that lasted six decades until his death at 75 in 1993. In homage to and celebration of this extraordinary and groundbreaking musical virtuoso what follows is an extensive musical and video sampling as well as critical appreciation and examination of his brilliant and prolific artistry on trumpet as both an innovative small ensemble soloist and orchestral leader, composer, and arranger from 1940 to 1990. It's equally important to note that Dizzy was not only a great artist and teacher but a wonderful human being as well. ENJOY...

Kofi

WAKE FOREST HISTORICAL MUSEUM

In one of the most spectacular, and possibly strangest, moments in Wake Forest’s holiday history, music legend Dizzy Gillespie bounded off a Greyhound bus on Owen Avenue to play an impromptu jam session at the town’s Community House just days before the 1948 Wake Forest Community Christmas Dinner. It was the last week of November, time to ring in the holiday season. Although still a new tradition, the annual Christmas Dinner was extremely popular; volunteers had started it the year before to give returning World War II veterans a warm welcome home and it was fast becoming a seasonal favorite. Now the civic clubs were once again ready to decorate the Community House with evergreen garlands, table centerpieces, and a large Christmas tree. But they couldn’t do it this particular afternoon—not after the historic entrance of Gillespie and his entire 18-piece jazz band.

In those days, Gillespie was a young trumpet virtuoso with an improvisational bebop style that made him the most controversial figure in American jazz. He was traveling on tour between West Virginia and Raleigh, and a group of Wake Forest College students who called themselves the “Friends of Jazz” had invited him to take a break near campus. Somewhat surprisingly, he accepted. It was a cold, rainy day when the bus drove into town on Highway 98, sloshed through mud to the Community House, and parked at the curb. Gillespie stepped out, dressed in a turtle-neck jacket, blue jeans, ostrich leather shoes, and a French beret. The students weren’t sure what to make of him. But he spoke in an easy, interesting way and, once inside the building, he quickly transformed that gray November afternoon into something extraordinary.

Student writer Harold Hayes (later the editor of Esquire magazine) reported on the event, vividly describing the scene inside the Community House. “Most of the students had gathered around him now and were trying to figure out what made him tick. At that time more than any other, perhaps, it was apparent that Diz was in a world of his own…. So it was with a feeling of encroachment that we asked him if three or four members of his band would play a few numbers…. From his horn ripped an incoherent stream of jumbled notes, beginning and ending where you wouldn’t expect, and touching on everything but the melody so that the suspense was unbearable.”

Gillespie and his musicians enjoyed a pleasant lunch of fried chicken, side dishes, and pie for dessert. Then they ripped into an unplanned concert. The band’s Cuban percussionist, Chano Pozo, straddled his Bongo drum and pounded out a rolling, erratic rhythm that rocked the house and could be heard from the campus Administration Building to Wooten’s Hometel on South Main Street. “We had expected them to be loud,” Hayes wrote, “but the word ‘loud’ used in reference to Dizzy Gillespie’s band is a gross understatement. Some students were left wondering if beams and timbers supporting the roof would be considered safe enough to keep the building from being condemned.”

Of course, Gillespie was a legend in the making. But that’s not the only reason his visit to Wake Forest is worth remembering. His concert for a handful of students was a special moment of shared appreciation and fellowship, the same two things that make the Wake Forest Community Christmas Dinner a cherished and longstanding tradition. The very event that was held a week after Gillespie’s visit to the Community House still happens every year, and it still remains Wake Forest’s best way of welcoming the holidays with friends and neighbors.