SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LAURA MVULA

October 10-16

DIZZY GILLESPIE

October 17-23

LESTER YOUNG

October 24-30

TIA FULLER

October 31-November 6

ROSCOE MITCHELL

November 7-13

MAX ROACH

November 14-20

DINAH WASHINGTON

November 21-27

BUDDY GUY

November 28-December 4

JOE HENDERSON

December 5-11

HENRY THREADGILL

December 12-18

MUDDY WATERS

December 19-25

B.B. KING

December 26-January 1

"The music of Charlie Parker and me laid a foundation for all the music that is being played now. Our music is going to be the classical music of the future."

http://www.biography.com/people/dizzy-gillespie-9311417

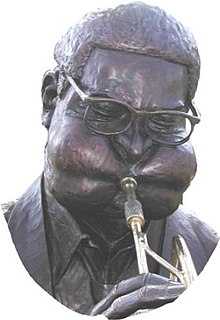

Dizzy Gillespie

(b. October 21, 1917-d. January 6, 1993)

(b. October 21, 1917-d. January 6, 1993)

Composer, Trumpet Player, Singer

(1917–1993)

A

jazz trumpeter and composer, Dizzy Gillespie played with Charlie Parker

and developed the music known as "bebop." His best-known compositions

include "Oop Bob Sh' Bam," "Groovin' High," "Salt Peanuts" and "A Night

in Tunisia."

Synopsis

Born on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina, Dizzy Gillespie, known for his "swollen" cheeks and signature (uniquely angled) trumpet's bell, got his start in the mid-1930s by working in prominent swing bands, including those of Benny Carter and Charlie Barnet. He later created his own band and developed his own signature style, known as "bebop," and worked with musical greats like Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Earl Hines, Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington. Gillespie's best-known compositions include "Oop Bob Sh' Bam," "Groovin' High," "Salt Peanuts," "A Night in Tunisia" and "Johnny Come Lately." Gillespie died in New Jersey in 1993. Today, he is considered one of the most influential figures of jazz and bebop.

Early Life

Famed jazz trumpeter and composer Dizzie Gillespie was born John Birks Gillespie on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina. He would go on to become one of the most recognizable faces of jazz music, with his "swollen" cheeks and signature (uniquely angled) trumpet's bell, as well as one of the most influential figures of jazz and bebop.

When he was 18 years old, Gillespie moved with his family to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He joined the Frankie Fairfax Orchestra not long after, and then relocated to New York City, where he performed with Teddy Hill and Edgar Hayes in the late 1930s. Gillespie went on to join Cab Calloway's band in 1939, with whom he recorded "Pickin' the Cabbage"—one of Gillespie's first compositions, and regarded by some in the jazz world as his first attempt to bring a Latin influence into his work.

Commercial Success

From 1937 to '44, Gillespie performed with prominent swing bands, including those of Benny Carter and Charlie Barnet. He also began working with musical greats such as Ella Fitzgerald, Earl Hines, Jimmy Dorsey and Charlie Parker around this time. Working as a bandleader, often with Parker on saxophone, Gillespie developed the musical genre known as "bebop"—a reaction to swing, distinct for dissonant harmonies and polyrhythms. "The music of Charlie Parker and me laid a foundation for all the music that is being played now," Gillespie said years later. "Our music is going to be the classical music of the future."

In addition to creating bebop, Gillespie is considered one of the first musicians to infuse Afro-Cuban, Caribbean and Brazilian rhythms with jazz. His work in the Latin-jazz genre includes "Manteca," "A Night in Tunisia" and "Guachi Guaro," among other recordings.

Gillespie's own big band, which performed from 1946 to '50, was his masterpiece, affording him scope as both soloist and showman. He became immediately recognizable from the unusual shape of his trumpet, with the bell tilted upward at a 45-degree angle—the result of someone accidentally sitting on it in 1953, but to good effect, for when he played it afterward, he discovered that its new shape improved the instrument's sound quality, and he had it incorporated into all his trumpets thereafter. Gillespie's best-known works from this period include the songs "Oop Bob Sh' Bam," "Groovin' High," "Leap Frog," "Salt Peanuts" and "My Melancholy Baby."

In the late 1950s, Gillespie performed with Duke Ellington, Paul Gonsalves and Johnny Hodges on Ellington's Jazz Party (1959). The following year, Gillespie released A Portrait of Duke Ellington (1960), an album dedicated to Ellington also featuring the work of Juan Tizol, Billy Strayhorn and Mercer Ellington, son of the legendary musician. Gillespie composed most of the album's recordings, including "Serenade to Sweden," "Sophisticated Lady" and "Johnny Come Lately."

Final Years

Gillespie's memoirs, entitled To BE or Not to BOP: Memoirs of Dizzy Gillespie (with Al Fraser), were published in 1979. More than a decade later, in 1990, he received the Kennedy Center Honors Award.

Dizzy Gillespie died on January 6, 1993, at age 75, in Englewood, New Jersey.

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1021.html

Dizzy Gillespie, Who Sounded Some of Modern Jazz's Earliest Notes, Dies at 75

Dizzy

Gillespie, the trumpet player whose role as a founding father of modern

jazz made him a major figure in 20th-century American music and whose

signature moon cheeks and bent trumpet made him one of the world's most

instantly recognizable figures, died yesterday at Englewood Hospital in

Englewood, N.J.

John

Birks Gillespie was born in Cheraw, S.C., on Oct. 21, 1917. His father,

a bricklayer, led a local band, and by the age of 14 the young

Gillespie was practicing the trumpet. He and his family moved to

Philadelphia two years later, and Mr. Gillespie, though he thought about

entering Temple University, quickly began a succession of professional

jobs.

Joining With Parker To Mold New Style

It

was while touring with the Calloway band in 1940 that Mr. Gillespie met

Charlie Parker in Kansas City. And it was with him that Mr. Gillespie

began formulating the style that was eventually called be-bop. Along

with a handful of other musicians, including Thelonious Monk and Kenny

Clarke, Mr. Gillespie and Mr. Parker would regularly experiment.

Synopsis

Born on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina, Dizzy Gillespie, known for his "swollen" cheeks and signature (uniquely angled) trumpet's bell, got his start in the mid-1930s by working in prominent swing bands, including those of Benny Carter and Charlie Barnet. He later created his own band and developed his own signature style, known as "bebop," and worked with musical greats like Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Earl Hines, Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington. Gillespie's best-known compositions include "Oop Bob Sh' Bam," "Groovin' High," "Salt Peanuts," "A Night in Tunisia" and "Johnny Come Lately." Gillespie died in New Jersey in 1993. Today, he is considered one of the most influential figures of jazz and bebop.

Early Life

Famed jazz trumpeter and composer Dizzie Gillespie was born John Birks Gillespie on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina. He would go on to become one of the most recognizable faces of jazz music, with his "swollen" cheeks and signature (uniquely angled) trumpet's bell, as well as one of the most influential figures of jazz and bebop.

When he was 18 years old, Gillespie moved with his family to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He joined the Frankie Fairfax Orchestra not long after, and then relocated to New York City, where he performed with Teddy Hill and Edgar Hayes in the late 1930s. Gillespie went on to join Cab Calloway's band in 1939, with whom he recorded "Pickin' the Cabbage"—one of Gillespie's first compositions, and regarded by some in the jazz world as his first attempt to bring a Latin influence into his work.

Commercial Success

From 1937 to '44, Gillespie performed with prominent swing bands, including those of Benny Carter and Charlie Barnet. He also began working with musical greats such as Ella Fitzgerald, Earl Hines, Jimmy Dorsey and Charlie Parker around this time. Working as a bandleader, often with Parker on saxophone, Gillespie developed the musical genre known as "bebop"—a reaction to swing, distinct for dissonant harmonies and polyrhythms. "The music of Charlie Parker and me laid a foundation for all the music that is being played now," Gillespie said years later. "Our music is going to be the classical music of the future."

In addition to creating bebop, Gillespie is considered one of the first musicians to infuse Afro-Cuban, Caribbean and Brazilian rhythms with jazz. His work in the Latin-jazz genre includes "Manteca," "A Night in Tunisia" and "Guachi Guaro," among other recordings.

Gillespie's own big band, which performed from 1946 to '50, was his masterpiece, affording him scope as both soloist and showman. He became immediately recognizable from the unusual shape of his trumpet, with the bell tilted upward at a 45-degree angle—the result of someone accidentally sitting on it in 1953, but to good effect, for when he played it afterward, he discovered that its new shape improved the instrument's sound quality, and he had it incorporated into all his trumpets thereafter. Gillespie's best-known works from this period include the songs "Oop Bob Sh' Bam," "Groovin' High," "Leap Frog," "Salt Peanuts" and "My Melancholy Baby."

In the late 1950s, Gillespie performed with Duke Ellington, Paul Gonsalves and Johnny Hodges on Ellington's Jazz Party (1959). The following year, Gillespie released A Portrait of Duke Ellington (1960), an album dedicated to Ellington also featuring the work of Juan Tizol, Billy Strayhorn and Mercer Ellington, son of the legendary musician. Gillespie composed most of the album's recordings, including "Serenade to Sweden," "Sophisticated Lady" and "Johnny Come Lately."

Final Years

Gillespie's memoirs, entitled To BE or Not to BOP: Memoirs of Dizzy Gillespie (with Al Fraser), were published in 1979. More than a decade later, in 1990, he received the Kennedy Center Honors Award.

Dizzy Gillespie died on January 6, 1993, at age 75, in Englewood, New Jersey.

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1021.html

January 7, 1993

OBITUARY

Dizzy Gillespie, Who Sounded Some of Modern Jazz's Earliest Notes, Dies at 75

by PETER WATROUS

New York Times

Dizzy

Gillespie, the trumpet player whose role as a founding father of modern

jazz made him a major figure in 20th-century American music and whose

signature moon cheeks and bent trumpet made him one of the world's most

instantly recognizable figures, died yesterday at Englewood Hospital in

Englewood, N.J.

Mr. Gillespie, who was 75, had been suffering for some time from pancreatic cancer, his press agent, Virginia Wicks, said.

In

a nearly 60-year career as a composer, band leader and innovative

player, Mr. Gillespie cut a huge swath through the jazz world. In the

early 40's, along with the alto saxophonist Charlie (Yardbird) Parker,

he initiated be-bop, the sleek, intense, high-speed revolution that has

become jazz's most enduring style. In subsequent years he incorporated

Afro-Cuban music into jazz, creating a new genre from the combination.

In

the naturally effervescent Mr. Gillespie, opposites existed. His

playing -- and he performed constantly until nearly the end of his life

-- was meteoric, full of virtuosic invention and deadly serious. But

with his endlessly funny asides, his huge variety of facial expressions

and his natural comic gifts, he was as much a pure entertainer as an

accomplished artist. In some ways, he seemed to sum up all the

possibilities of American popular art.

From Carolina To the Big Bands

John

Birks Gillespie was born in Cheraw, S.C., on Oct. 21, 1917. His father,

a bricklayer, led a local band, and by the age of 14 the young

Gillespie was practicing the trumpet. He and his family moved to

Philadelphia two years later, and Mr. Gillespie, though he thought about

entering Temple University, quickly began a succession of professional

jobs.

He worked with Bill Doggett, the pianist and organist, who

fired him for not being able to read music well enough, and then Frank

Fairfax, a big-band leader whose orchestra included the trumpeter

Charlie Shavers and the clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton. Mr. Gillespie was

listening to the trumpeter Roy Eldridge, copying his solos and emulating

his style, and was soon performing with Teddy Hill's band at the Savoy

Ballroom on the basis of his ability to reproduce Mr. Eldridge's style.

According

to legend, it was Mr. Hill who gave Mr. Gillespie his nickname because

of his odd clothing style and his fondness for practical jokes. Mr.

Gillespie began cultivating his personality, putting his feet up on

music stands during shows and regularly cracking jokes. But by May 1937

he was also recording improvisations with the Hill band and helping the

performances by setting riffs behind soloists.

Two years later,

Mr. Gillepsie was considered accomplished enough to take part in a

series of all-star recordings with Lionel Hampton, Benny Carter, Coleman

Hawkins, Ben Webster and Chu Berry. He soloed on "Hot Mallets."

That

year, 1939, he joined Cab Calloway's band, one of the leading black

orchestras of the era. Though a dance band, its musicians, who included

the bassist Milt Hinton and the guitarist Danny Barker, liked to

experiment. Mr. Gillespie would work on the harmonic substitutions that

eventually became be-bop. Mr. Gillespie was a regular soloist with the

band, and by then his harmonic sensibility was beginning to take shape.

Joining With Parker To Mold New Style

It

was while touring with the Calloway band in 1940 that Mr. Gillespie met

Charlie Parker in Kansas City. And it was with him that Mr. Gillespie

began formulating the style that was eventually called be-bop. Along

with a handful of other musicians, including Thelonious Monk and Kenny

Clarke, Mr. Gillespie and Mr. Parker would regularly experiment.

On

live recordings of the period, especially the two solos on the tune

"Kerouac," recorded in 1941 at Minton's Uptown Playhouse, a club in

Harlem, can be heard his increasing interest in harmony, sleeker rhythms

and a divergence from the style of Mr. Eldridge. Mr. Gillespie was

blunt about his relationship with Mr. Parker, calling him "the other

side of my heartbeat," and freely giving him credit for some of the

rhythmic innovations of be-bop.

At the same time that Mr.

Gillespie was experimenting with the new style, he was regularly

arranging and recording for Mr. Calloway, including one of his better

improvisations on "Pickin' the Cabbage," a piece he composed and

arranged. In September 1941, at the State Theater in Hartford, Mr.

Gillespie was involved in an incident that shaped his reputation and his

career. Mr. Calloway saw a spitball thrown on stage and thought Mr.

Gillespie had done it; the two men fought, and Mr. Gillespie pulled a

knife and put a cut in Mr. Calloway's posterior that required 10

stitches to close.

Mr. Gillespie was fired from that job, but

spent the next several years working with some of the biggest names in

jazz, including Coleman Hawkins (who recorded the first version of Mr.

Gillespie's classic "Woody 'N' You"), Benny Carter, Les Hite (for whom

he recorded "Jersey Bounce," considered the first be-bop solo), Lucky

Millinder, Earl Hines, Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington. For Mr.

Millinder he made "Little John Special," which includes a riff of Mr.

Gillespie's that was later fleshed out into the composition "Salt

Peanuts," one of his best-known pieces.

The early 40's were a

turbulent time for jazz. Be-bop was slowly making itself felt, but at

the same time a series of disputes between recording companies and the

musicians' union resulted in a recording ban, so Mr. Gillespie and Mr.

Parker were rarely recorded. In 1943 Mr. Gillespie led a band with the

be-bop bassist Oscar Pettiford at the Onyx Club on 52d Street in

Manhattan. And in 1944, the singer Billy Eckstine took over part of the

Earl Hines band and created the first be-bop orchestra, of which few

recorded performaces exist. Mr. Gillespie was the music director, and

the band featured his "Night in Tunisia."

It was in 1945 that

Mr. Gillespie began to break out. He undertook an ambitious recording

schedule, recording with the pianist Clyde Hart and with Mr. Parker,

Cootie Williams, Red Norvo, Sarah Vaughan and Slim Gaillard. And he

began series of his own recordings that have since become some of jazz's

most important pieces.

Recording under his own name for the

first time, he made "I Can't Get Started," "Good Bait," "Salt Peanuts"

and "Be-bop," during one session in January 1945. He followed it up with

a recording date featuring Mr. Parker that included "Groovin' High,"

"Dizzy Atmosphere" and "All the Things You Are."

These

recordings, with their tight ensemble passages, precisely articulated

rhythms and dissonance as part of the palate of jazz, were to influence

jazz forever. Though Mr. Gillespie enjoyed playing for dancers, this was

music that was meant first and foremost to be listened to. It was

virtuosic in a way not heard before, and it was music that sent music

students scurrying to their turntables to learn the improvisations by

heart.

They were also the recordings that captured Mr. Gillespie

at his most impressive. His lines, jagged and angular, always seemed off

balance. He used chromatic figures, and was not afraid to resolve a

line on a vinegary, bitter note. And his improvising was eruptive;

suddenly, a line would bolt into the high register, only to come

tumbling down.

Mr. Gillespie did more than just record in 1945.

He put together the first of his big bands, and then formed a quintet

with Mr. Parker that Mr. Gillespie called "The height of perfection in

our music." It included Bud Powell on piano, Ray Brown on bass and Max

Roach on drums. Later that year, Mr. Gillespie reformed the big band,

called the Hepsations of 1945. Despitea tour of the South that was

almost catastrophically unsuccessful, the band stayed together for the

next four years. Another Revolution: Afro-Cuban Jazz

It was with

this big band, whose name became the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra, that Mr.

Gillespie created his second revolution in the late 1940's. An old

friend, the Cuban trumpeter Mario Bauza, who had made it possible for

him to join the Calloway orchestra, introduced Mr. Gillespie to the

Cuban conga player Luciano (Chano Pozo) Gonzales.

"Dizzy used to

ask me about Cuban rhythms all the time," said Mr. Bauza. "I introduced

him to Chano Pozo, and they wrote 'Manteca.' It was a good marriage of

two cultures. That was the beginning of Afro-Cuban jazz. That blew up

the whole world."

Mr. Gillespie quickly produced the sketches for

"Cubana Be" and "Cubana Bop," which were finished by the composer and

arranger George Russell and included some of the first modal harmonies

in jazz. And in "Manteca," Mr. Gillespie's collaboration with Mr. Pozo,

he created a work that is still performed and quoted regularly, by both

Latin orchestras and by jazz musicians. Without the sophisticated

arrangements and the conjunction of Latin rhythms and jazz harmonies

that Mr. Gillespie provided, both jazz and Latin music would be

radically different today.

The band's highest moments, however,

were when Mr. Gillespie -- in a move that characterized his career --

hired some of the young be-boppers on the scene. Among them were the

pianist John Lewis, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, bassist Ray Brown and

drummer Kenny Clarke, who went on to form the Modern Jazz Quartet. "It

was an incredible experience because so much was going on," Mr. Lewis

recalled. "Not only was he using these great be-bop arrangements but he

was so encouraging. It was my first job, a formative experience."

Mr.

Gillespie's was the last great evolutionary big band, and during its

tenure he hired the best soloists, from Jimmy Heath, James Moody and

Sonny Stitt to John Coltrane and Paul Gonzalves. Arrangements like

"Things to Come," with their exhilarating precision, were be-bop and

orchestral landmarks, with dense harmonies and flashy rhythms.

And

it was with his big band that Mr. Gillespie fully developed the other

side of his musical personality. With songs like "He Beeped When He

Should Have Bopped," "Ool Ya Koo", "Oo Pop A Da" and others, he began

popularizing the Bohemian, Dadaesque aspects of be-bop.

Mr.

Gillespie was a keen popularizer, and with his sense of comedy managed

to make his shows into an extraordinary mixture of entertainment and

esthetics. In so doing, he was following in the path of his

ex-bandleader, Mr. Calloway, as well as Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller.

From

then on, he cultivated an audience that went beyond the average jazz

fan, and it was this reputation that helped in his later career. And at

the same time, be-bop fashion made an appearance, with Mr. Gillespie, in

thick glasses and a beret, leading the way.

The big-band

business slowed down considerably in the late 1940's and early 50's, and

Mr. Gillespie teamed with Stan Kenton's orchestra as a featured

soloist. Then he began using a small group again.

He formed his

own record company in 1951, Dee Gee, which folded soon after. Mr.

Gillespie and Mr. Parker recorded for Verve, with Mr. Monk, and he and

Mr. Parker performed at Birdland in Manhattan the next year. He toured

Europe and in 1953 joined Mr. Parker, Mr. Powell, Mr. Roach and the

bassist Charles Mingus for a concert at Massey Hall in Toronto that

became legendary for its disorganization and for acrimony among

performers.

It was also in 1953 that someone fell on Mr.

Gillespie's trumpet, and bent it. When he played the misshapen

instrument, Mr. Gillespie found he could hear the sound more clearly,

and so decided to keep it. Along with those cheeks, it became his

trademark.

During the 1950's Mr. Gillespie recorded with with

Stan Getz, Stuff Smith, Sonny Stitt, Mr. Eldridge and others. In 1956,

he formed another big band and, at the behest of the United States State

Department, toured the Middle East and South America. In 1957, Mr.

Gillespie presided over "The Eternal Triangle," a recording that

includes Mr. Stitt and Sonny Rollins and some of the hardest trumpet

blowing ever recorded.

Through the 1960's and 70's, Mr. Gillespie

toured frequently, playing up to 300 shows a year, sometimes with an

electric bassist and a guitarist, sometimes with a more traditional

group. And in 1974 he signed with Pablo Records and began recording

prolifically again. He won Grammies in 1975 and 1980, and he published

his autobiography, "To Be or Not to Bop," in 1979.

In the last

decade, Mr. Gillespie's career seemed recharged, and he became

ubiquitous on the concert circuit as a special guest. He formed a Latin

big band that performed with Paquito De Rivera, among others, and he

constantly shuffled the personnel of his small groups.

Last year,

in honor of his 75th birthday, Mr. Gillepsie played for four weeks at

the Blue Note club in Manhattan, a stint that featured perhaps the

greatest selection of jazz musicians ever brought together for a

tribute. The month covered his career, from small groups, to Afro-Cuban

jazz to a big band. As usual, he was his witty amiable self, in command

of both the audience and his trumpet.

Mr. Gillespie is survived by his wife of 52 years, Lorraine.

Seeking the Best Of a Huge Output

Dizzy

Gillespie's recorded output was immense, spanning nearly 60 years and

comprising hundreds of albums. Not all of his important recordings have

been issued on CD, but the vinyl versions are worth hunting for.

Afro Cuban Jazz Verve

The Be-Bop Revolution RCA

Bird and Diz Verve

The Development of an American Artist Smithsonian

Diz and Getz Verve

Dizzy and the Double Six of Paris Phillips

Dizzy at Newport Verve

Dizzy on the French Riviera Phillips

Dizzy's Diamonds Verve

Duets Verve

The Gifted Ones (with Roy Eldridge) Pablo

Live at the Royal Festival Hall Enja

Oscar Peterson and Dizzy Gillespie Pablo

Portrait of Duke Ellington Verve

Shaw Nuff Musicraft

Sonny Side Up (with Sonny Stitt) Verve

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/dizzy-gillespie-mn0000162677/biography

Dizzy Gillespie

Active: 1930s - 1990s

Born: October 21, 1917 in Cheraw, SC

Died: January 6, 1993 in Englewood, NJ

Genre: Jazz

Styles: Afro-Cuban Jazz Bop Vocal Jazz World Fusion Big Band Jazz Instrument Trumpet Jazz

Also Known As:

John "Dizzy" Gillespie

John Birks 'Dizzy' Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie

John Birks Gillespie

John Gillespie

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Trumpet

virtuoso and bop revolutionary whose desire to innovate helped invent

and define the musical vocabulary for an entire

genre.

Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis' emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated. Somehow, Gillespie could make any "wrong" note fit, and harmonically he was ahead of everyone in the 1940s, including Charlie Parker. Unlike Bird, Dizzy was an enthusiastic teacher who wrote down his musical innovations and was eager to explain them to the next generation, thereby insuring that bebop would eventually become the foundation of jazz.

Dizzy Gillespie was also one of the key founders of Afro-Cuban (or Latin) jazz, adding Chano Pozo's conga to his orchestra in 1947, and utilizing complex poly-rhythms early on. The leader of two of the finest big bands in jazz history, Gillespie differed from many in the bop generation by being a masterful showman who could make his music seem both accessible and fun to the audience. With his puffed-out cheeks, bent trumpet (which occurred by accident in the early '50s when a dancer tripped over his horn), and quick wit, Dizzy was a colorful figure to watch. A natural comedian, Gillespie was also a superb scat singer and occasionally played Latin percussion for the fun of it, but it was his trumpet playing and leadership abilities that made him into a jazz giant.

The youngest of nine children, John Birks Gillespie taught himself trombone and then switched to trumpet when he was 12. He grew up in poverty, won a scholarship to an agricultural school (Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina), and then in 1935 dropped out of school to look for work as a musician. Inspired and initially greatly influenced by Roy Eldridge, Gillespie (who soon gained the nickname of "Dizzy") joined Frankie Fairfax's band in Philadelphia. In 1937, he became a member of Teddy Hill's orchestra in a spot formerly filled by Eldridge. Dizzy made his recording debut on Hill's rendition of "King Porter Stomp" and during his short period with the band toured Europe. After freelancing for a year, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra (1939-1941), recording frequently with the popular bandleader and taking many short solos that trace his development; "Pickin' the Cabbage" finds Dizzy starting to emerge from Eldridge's shadow. However, Calloway did not care for Gillespie's constant chance-taking, calling his solos "Chinese music." After an incident in 1941 when a spitball was mischievously thrown at Calloway (he accused Gillespie but the culprit was actually Jonah Jones), Dizzy was fired.

By then, Gillespie had already met Charlie Parker, who confirmed the validity of his musical search. During 1941-1943, Dizzy passed through many bands including those led by Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Charlie Barnet, Fess Williams, Les Hite, Claude Hopkins, Lucky Millinder (with whom he recorded in 1942), and even Duke Ellington (for four weeks). Gillespie also contributed several advanced arrangements to such bands as Benny Carter, Jimmy Dorsey, and Woody Herman; the latter advised him to give up his trumpet playing and stick to full-time arranging.

Dizzy ignored the advice, jammed at Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House where he tried out his new ideas, and in late 1942 joined Earl Hines' big band. Charlie Parker was hired on tenor and the sadly unrecorded orchestra was the first orchestra to explore early bebop. By then, Gillespie had his style together and he wrote his most famous composition "A Night in Tunisia." When Hines' singer Billy Eckstine went on his own and formed a new bop big band, Diz and Bird (along with Sarah Vaughan) were among the members. Gillespie stayed long enough to record a few numbers with Eckstine in 1944 (most noticeably "Opus X" and "Blowing the Blues Away"). That year he also participated in a pair of Coleman Hawkins-led sessions that are often thought of as the first full-fledged bebop dates, highlighted by Dizzy's composition "Woody'n You."

1945 was the breakthrough year. Dizzy Gillespie, who had led earlier bands on 52nd Street, finally teamed up with Charlie Parker on records. Their recordings of such numbers as "Salt Peanuts," "'Shaw Nuff," "Groovin' High," and "Hot House" confused swing fans who had never heard the advanced music as it was evolving; and Dizzy's rendition of "I Can't Get Started" completely reworked the former Bunny Berigan hit. It would take two years for the often frantic but ultimately logical new style to start catching on as the mainstream of jazz. Gillespie led an unsuccessful big band in 1945 (a Southern tour finished it), and late in the year he traveled with Parker to the West Coast to play a lengthy gig at Billy Berg's club in L.A. Unfortunately, the audiences were not enthusiastic (other than local musicians) and Dizzy (without Parker) soon returned to New York.

The following year, Dizzy Gillespie put together a successful and influential orchestra which survived for nearly four memorable years. "Manteca" became a standard, the exciting "Things to Come" was futuristic, and "Cubana Be/Cubana Bop" featured Chano Pozo. With such sidemen as the future original members of the Modern Jazz Quartet (Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Ray Brown, and Kenny Clarke), James Moody, J.J. Johnson, Yusef Lateef, and even a young John Coltrane, Gillespie's big band was a breeding ground for the new music. Dizzy's beret, goatee, and "bop glasses" helped make him a symbol of the music and its most popular figure. During 1948-1949, nearly every former swing band was trying to play bop, and for a brief period the major record companies tried very hard to turn the music into a fad.

By 1950, the fad had ended and Gillespie was forced, due to economic pressures, to break up his groundbreaking orchestra. He had occasional (and always exciting) reunions with Charlie Parker (including a fabled Massey Hall concert in 1953) up until Bird's death in 1955, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic (where he had opportunities to "battle" the combative Roy Eldridge), headed all-star recording sessions (using Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, and Sonny Stitt on some dates), and led combos that for a time in 1951 also featured Coltrane and Milt Jackson. In 1956, Gillespie was authorized to form a big band and play a tour overseas sponsored by the State Department. It was so successful that more traveling followed, including extensive tours to the Near East, Europe, and South America, and the band survived up to 1958. Among the young sidemen were Lee Morgan, Joe Gordon, Melba Liston, Al Grey, Billy Mitchell, Benny Golson, Ernie Henry, and Wynton Kelly; Quincy Jones (along with Golson and Liston) contributed some of the arrangements. After the orchestra broke up, Gillespie went back to leading small groups, featuring such sidemen in the 1960s as Junior Mance, Leo Wright, Lalo Schifrin, James Moody, and Kenny Barron. He retained his popularity, occasionally headed specially assembled big bands, and was a fixture at jazz festivals. In the early '70s, Gillespie toured with the Giants of Jazz and around that time his trumpet playing began to fade, a gradual decline that would make most of his '80s work quite erratic. However, Dizzy remained a world traveler, an inspiration and teacher to younger players, and during his last couple of years he was the leader of the United Nation Orchestra (featuring Paquito D'Rivera and Arturo Sandoval). He was active up until early 1992.

Dizzy Gillespie's career was very well documented from 1945 on, particularly on Musicraft, Dial, and RCA in the 1940s; Verve in the 1950s; Philips and Limelight in the 1960s; and Pablo in later years.

Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis' emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated. Somehow, Gillespie could make any "wrong" note fit, and harmonically he was ahead of everyone in the 1940s, including Charlie Parker. Unlike Bird, Dizzy was an enthusiastic teacher who wrote down his musical innovations and was eager to explain them to the next generation, thereby insuring that bebop would eventually become the foundation of jazz.

Dizzy Gillespie was also one of the key founders of Afro-Cuban (or Latin) jazz, adding Chano Pozo's conga to his orchestra in 1947, and utilizing complex poly-rhythms early on. The leader of two of the finest big bands in jazz history, Gillespie differed from many in the bop generation by being a masterful showman who could make his music seem both accessible and fun to the audience. With his puffed-out cheeks, bent trumpet (which occurred by accident in the early '50s when a dancer tripped over his horn), and quick wit, Dizzy was a colorful figure to watch. A natural comedian, Gillespie was also a superb scat singer and occasionally played Latin percussion for the fun of it, but it was his trumpet playing and leadership abilities that made him into a jazz giant.

The youngest of nine children, John Birks Gillespie taught himself trombone and then switched to trumpet when he was 12. He grew up in poverty, won a scholarship to an agricultural school (Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina), and then in 1935 dropped out of school to look for work as a musician. Inspired and initially greatly influenced by Roy Eldridge, Gillespie (who soon gained the nickname of "Dizzy") joined Frankie Fairfax's band in Philadelphia. In 1937, he became a member of Teddy Hill's orchestra in a spot formerly filled by Eldridge. Dizzy made his recording debut on Hill's rendition of "King Porter Stomp" and during his short period with the band toured Europe. After freelancing for a year, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra (1939-1941), recording frequently with the popular bandleader and taking many short solos that trace his development; "Pickin' the Cabbage" finds Dizzy starting to emerge from Eldridge's shadow. However, Calloway did not care for Gillespie's constant chance-taking, calling his solos "Chinese music." After an incident in 1941 when a spitball was mischievously thrown at Calloway (he accused Gillespie but the culprit was actually Jonah Jones), Dizzy was fired.

By then, Gillespie had already met Charlie Parker, who confirmed the validity of his musical search. During 1941-1943, Dizzy passed through many bands including those led by Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Charlie Barnet, Fess Williams, Les Hite, Claude Hopkins, Lucky Millinder (with whom he recorded in 1942), and even Duke Ellington (for four weeks). Gillespie also contributed several advanced arrangements to such bands as Benny Carter, Jimmy Dorsey, and Woody Herman; the latter advised him to give up his trumpet playing and stick to full-time arranging.

Dizzy ignored the advice, jammed at Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House where he tried out his new ideas, and in late 1942 joined Earl Hines' big band. Charlie Parker was hired on tenor and the sadly unrecorded orchestra was the first orchestra to explore early bebop. By then, Gillespie had his style together and he wrote his most famous composition "A Night in Tunisia." When Hines' singer Billy Eckstine went on his own and formed a new bop big band, Diz and Bird (along with Sarah Vaughan) were among the members. Gillespie stayed long enough to record a few numbers with Eckstine in 1944 (most noticeably "Opus X" and "Blowing the Blues Away"). That year he also participated in a pair of Coleman Hawkins-led sessions that are often thought of as the first full-fledged bebop dates, highlighted by Dizzy's composition "Woody'n You."

1945 was the breakthrough year. Dizzy Gillespie, who had led earlier bands on 52nd Street, finally teamed up with Charlie Parker on records. Their recordings of such numbers as "Salt Peanuts," "'Shaw Nuff," "Groovin' High," and "Hot House" confused swing fans who had never heard the advanced music as it was evolving; and Dizzy's rendition of "I Can't Get Started" completely reworked the former Bunny Berigan hit. It would take two years for the often frantic but ultimately logical new style to start catching on as the mainstream of jazz. Gillespie led an unsuccessful big band in 1945 (a Southern tour finished it), and late in the year he traveled with Parker to the West Coast to play a lengthy gig at Billy Berg's club in L.A. Unfortunately, the audiences were not enthusiastic (other than local musicians) and Dizzy (without Parker) soon returned to New York.

The following year, Dizzy Gillespie put together a successful and influential orchestra which survived for nearly four memorable years. "Manteca" became a standard, the exciting "Things to Come" was futuristic, and "Cubana Be/Cubana Bop" featured Chano Pozo. With such sidemen as the future original members of the Modern Jazz Quartet (Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Ray Brown, and Kenny Clarke), James Moody, J.J. Johnson, Yusef Lateef, and even a young John Coltrane, Gillespie's big band was a breeding ground for the new music. Dizzy's beret, goatee, and "bop glasses" helped make him a symbol of the music and its most popular figure. During 1948-1949, nearly every former swing band was trying to play bop, and for a brief period the major record companies tried very hard to turn the music into a fad.

By 1950, the fad had ended and Gillespie was forced, due to economic pressures, to break up his groundbreaking orchestra. He had occasional (and always exciting) reunions with Charlie Parker (including a fabled Massey Hall concert in 1953) up until Bird's death in 1955, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic (where he had opportunities to "battle" the combative Roy Eldridge), headed all-star recording sessions (using Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, and Sonny Stitt on some dates), and led combos that for a time in 1951 also featured Coltrane and Milt Jackson. In 1956, Gillespie was authorized to form a big band and play a tour overseas sponsored by the State Department. It was so successful that more traveling followed, including extensive tours to the Near East, Europe, and South America, and the band survived up to 1958. Among the young sidemen were Lee Morgan, Joe Gordon, Melba Liston, Al Grey, Billy Mitchell, Benny Golson, Ernie Henry, and Wynton Kelly; Quincy Jones (along with Golson and Liston) contributed some of the arrangements. After the orchestra broke up, Gillespie went back to leading small groups, featuring such sidemen in the 1960s as Junior Mance, Leo Wright, Lalo Schifrin, James Moody, and Kenny Barron. He retained his popularity, occasionally headed specially assembled big bands, and was a fixture at jazz festivals. In the early '70s, Gillespie toured with the Giants of Jazz and around that time his trumpet playing began to fade, a gradual decline that would make most of his '80s work quite erratic. However, Dizzy remained a world traveler, an inspiration and teacher to younger players, and during his last couple of years he was the leader of the United Nation Orchestra (featuring Paquito D'Rivera and Arturo Sandoval). He was active up until early 1992.

Dizzy Gillespie's career was very well documented from 1945 on, particularly on Musicraft, Dial, and RCA in the 1940s; Verve in the 1950s; Philips and Limelight in the 1960s; and Pablo in later years.

Launch Dizzy Gillespie Radio:

Primary Instrument: Trumpet

Born: October 21, 1917 | Died: January 6, 1993

John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie was one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of the 20th century and one of the prime architects of the bebop movement in jazz. Nicknamed “Dizzy” because of his zany on-stage antics, Gillespie, a brass virtuoso, set new standards for trumpet players with his innovative, “jolting rhythmic shifts and ceaseless harmonic explorations” on the instrument during the 1940's, which ushered in a definitive change in American jazz music from swing to bebop.Gillespie, the last of nine children, was born in Cheraw, South Carolina, in 1917 to James and Lottie Gillespie. His father was a bricklayer, pianist and band leader. James Gillespie kept all the instruments from his band in the family home, so the future trumpet great was surrounded by musical instruments from childhood, including his father's large upright piano - James tore down one of the walls of the house to get the piano inside. James demanded that all his children practice instruments. However, none of them except John cared much for music. James died when John Birks was ten, so he never heard his youngest son play trumpet; he did hear him practice piano, since John began playing the intrument at a very early age.

In 1933, after graduating from Robert Smalls' secondary school, Gillespie received a music scholarship to attend the Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina. He stayed there for two years, studying harmony and theory, until his family moved to Philadelphia in 1935. Once in Philadelphia, Gillespie began playing trumpet with local bands. He learned all of his idol Eldridge's solos from records and radio broadcasts; it was also in Philadelphia that he picked up the nickname “Dizzy.” In 1937, Gillespie moved to New York, replacing Roy Eldridge in Teddy Hill's Orchestra. In 1939, Gillespie was hired to play in Cab Calloway's orchestra; he was fired by Calloway in 1941 after an altercation between the two in which Calloway mistakenly accused Gillespie of firing spitballs at him and Gillespie pulled a knife on Calloway in, he said, self-defense.

In 1937, Gillespie met his future wife, Lorraine, a chorus dancer at the famed Apollo Theater. They were married in 1940 and remained together until his death. Gillespie worked with many bands during the early 1940's - Chick Webb, Fletcher Henderson, Benny Carter, “Fatha” Hines and Billy Eckstine's seminal band - before teaming up with Charlie Parker in 1945. Their revolutionary band ushered in the bebop era and was one of the greatest small bands of the 20th century. An arranger and composer, Gillespie wrote some of the greatest jazz tunes of his era, including Groovin' High, A Night in Tunisia and Manteca, all songs which became jazz classics.

With his trumpet's upturned golden bell - the result, Gillespie stated in his autobiography, of the dancers Stump and Stumpy accidentally falling onto it during a birthday party for his wife - and his goatee, horn rim glasses and beret, Gillespie became a symbol of both jazz and a rebellious, independent spirit during the 1940's and 50's. (One of Gillespie's trumpets sold for $63,000 in 1995.) His interest in Cuban and African music helped to introduce those styles to a mainstream American audience.

In both 1964 and 1972, Gillespie ran for President of the United States. He told Jet Magazine in 1971 that, if elected, he would name the boxer Muhammad Ali Secretary of State and would name Duke Ellington as ambassador “to any country he wants to go to.” Gillespie did not win the presidency in either year.

In 1970, Gillespie became a follower of the Bahá'í Faith. His belief helped find peace and meaning in his life, and he spoke often about his faith in his later years. The Bahá'í Center in New York honors Gillespie with a yearly memorial service and holds jazz concerts in its John Birks Gillespie Auditorium.

Dizzy Gillespie died of pancreatic cancer in 1993. He was world-famous and much beloved among musicians and listeners. Gillespie influenced generations of musicians who admired and emulated not just his musicianship, his positive, upbeat, optimistic attitude, and the spiritual path he had discovered. As musicians such as Randy Weston and Wynton Marsalis attest, Gillespie continues to influence jazz musicians and listeners to this day.

Awards

New Star Award, Esquire Magazine (1944); Handel Medallion, City of New York (1972); Paul Robeson Award, Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Studies (1972); Performs "Salt Peanuts" with President Carter at White House Jazz Concert (1978); Inducted into Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame (1982); Lifetime Achievement Award, National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) (1989); National Medal of Arts, President Bush (1989); Duke Ellington Award, Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (1989); Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1989); Kennedy Center Honors Award (1990); Fourteen honorary degrees, including Ph.D., Rutgers University (1972); Ph.D., Chicago Conservatory of Music (1978); Awarded a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

http://www.jazzandbluesmasters.com/dizzy.htm

dizzy gillespie . american jazz

musician b. 1917 d. 1993

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie, one of the greatest

Jazz trumpeters of 20th century and one of the prime architects of the bebop movement in

jazz, was born in Cheraw, South Carolina and died in Englewood, New Jersey.

Nicknamed "Dizzy" because of his zany on-stage antics, Gillespie, a brass virtuoso, set new standards for trumpet players with his innovative, "jolting rhythmic shifts and ceaseless harmonic explorations" on the instrument during the 1940's period, which ushered in a definitive change in American Jazz music from swing to bebop. The last of nine children, Gillespie was born into a family whose father, James, was a bricklayer, pianist and band leader: Dizzy's mother was named Lottie. Dizzy's father kept all the instruments from his band in the family home and so the future trumpet great was around trumpets, saxophones, guitars and his father's large upright piano (his father tore down one of the walls of the house to get the piano in ) most of his young life. James use to make all of his older children practice instruments but none of them cared for music. Dizzy's father died when he was ten and never heard his youngest son play trumpet, although he did get the chance to hear him banging around on the piano, because Dizzy started trying to play this intrument at a very early age.

In 1930, Gillespie tried learning how to play the trombone but his arms were too short to play it well. That same year he started playing a friend's trumpet and heard one night over the radio a broadcast of Roy Eldridge playing trumpet in Teddy Hill's Orchestra, that was playing at the Savoy Ballroom in New York City. Young Gillespie, then 13, loved Eldridge's playing and the entire band. From that day on, he dreamed of becoming a jazz musician.

In 1933, after graduating from Robert Smalls secondary school, Gillespie received a music scholarship to attend Laurinburg Institute, in North Carolina. He stayed there for two years, studying harmony and theory until his family moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1935. In Philadelphia, Gillespie began playing trumpet with local bands, learning all of his idol Eldridge's solos from records and radio broadcasts: it was in Philadelphia that he picked up his nickname of "Dizzy.". In 1937, "Dizzy" moved to New York and replaced Eldridge in Teddy Hill's Orchestra. After a couple of years Gillespie moved on to Cab Calloway's band in 1939.

In 1937, Gillespie met his future wife, Lorraine, a chorus dancer at the famed Apollo Theater: they were married in 1940 and remained together until his death. Gillespie worked with many bands during the early 1940's (Chick Webb, Fletcher Henderson, Benny Carter, "Fatha" Hines and Billy Eckstine's seminal band ) before teaming up with Charlie Parker in 1945. Their revolutionary band ushered in the bebop era and was one of the greatest small bands of the 20th century. An arranger and composer, Gillespie wrote some of the greatest jazz tunes of his era: songs such as "Groovin' High", "A Night in Tunisia" and "Manteca" are considered jazz classics today..

With his trumpet and its upturned, golden bell, goatee, black horn rim glasses and beret, Gillespie became a symbol of both jazz and a rebellious, independent spirit during the 1940's and 50's. His interest in Cuban and African music helped to introduce those music's to a mainstream American audience. When he died he was famous and beloved everywhere and had influenced entire generations of trumpet players all over the world who loved and emulated his playing and his always positive, upbeat, optimistic attitude.

Quincy Troupe

Biography

copyright Mason Editions 2000 and Quincy Troupe.

http://www.discogs.com/artist/64694-Dizzy-GillespieDizzy Gillespie

Real Name:

John Birks Gillespie

Profile: American jazz trumpet player, bandleader, singer, and composer dubbed "the sound of surprise". (born October 21, 1917, Cheraw, South Carolina; died January 6, 1993, Englewood, New Jersey)

Together, with Charlie Parker, he was the predominant figure in the development of bebop (bop), which laid the foundation for modern jazz. He taught and influenced many other musicians, including trumpeters Miles Davis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Arturo Sandoval, Lee Morgan, Jon Faddis and Chuck Mangione.

He was also one of the key founders of Afro-Cuban (or Latin) jazz, adding Chano Pozo's conga to his orchestra in 1947, and utilizing complex poly-rhythms early on.

Career Highlights:

Awarded New Star Award from Esquire Magazine (1944)

Performs at first integrated concert in public school, Cheraw, SC (1959)

First jazz musician appointed by US department of State to undertake cultural mission (1972)

Awarded Handel Medallion from the City of New York (1972)

Received Paul Robeson Award from Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Studies (1972)

Performs at White House for President Carter and the Shah of Iran (1977)

Performs "Salt Peanuts" with President Carter at White House Jazz Concert (1978)

Inducted into Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame (1982)

Received Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences (1989)

Received National Medal of Arts from President Bush (1989)

Received Duke Ellington Award from the society og Composers, Authors, and Publishers (1989)

Awarded Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1989)

Received Kennedy Center Honors Award (1990)

Received fourteen honorary degrees, including Ph.D. Rutgers University (1972), Ph.D. Chicago Conservatory of Music (1978)

Awarded a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for recording

Sites:

In Groups:

Billy Eckstine And His Orchestra, Cab Calloway And His Cotton Club Orchestra, Charlie Parker's Re-Boppers, Coleman Hawkins And His Orchestra, Dizzy Gillespie - Stan Getz Sextet, Dizzy Gillespie And His All Star Quintet, Dizzy Gillespie and His All Stars, Dizzy Gillespie And His Orchestra, Dizzy Gillespie Big Band, Dizzy Gillespie Jazzmen, Dizzy Gillespie Quartet, Dizzy Gillespie Quintet, Dizzy Gillespie Septet, Dizzy Gillespie Sextet, Dizzy Gillespie Tempo Jazzmen, Dizzy Gillespie's Big 4, Dizzy Gillespie's Rebop Six, Lionel Hampton And His Orchestra, Metronome All Stars, Red Norvo All-Stars, Red Norvo And His Selected Sextet, Rhythmstick, Slim Gaillard And His Orchestra, Tempo Jazzmen, The Dizzy Gillespie 6, The Dizzy Gillespie Alumni All Star Big Band, The Dizzy Gillespie Big 7, The Dizzy Gillespie Octet, The Dizzy Gillespie Reunion Big Band, The Gillespie-Getz-Stitt Septet, The Modern Jazz Sextet, The Quintet, The Trumpet Kings

http://www.openculture.com/2012/10/dizzy_gillespie_runs_for_us_president_1964_.html

Dizzy Gillespie Runs for US President, 1964.

Promises to Make Miles Davis Head of the CIA

October 1st, 2012

OPEN CULTURE

There comes a point in every national election year when I reach total saturation and have to tune it all out to stay sane—the nonstop streams of vitriol, the spectacles of electoral dysfunction, the ads, the ads, the ads. I’m sure I’m not alone in this. But imagine how differently we could feel about presidential elections if people like, I don’t know, Dizzy Gillespie could get on a major ticket? That’s what might have happened in 1964 if “a little-known presidential campaign… had been able to vault the millionaires-only hurdle.” What began as one of Dizzy’s famous practical jokes, and a way to raise money for CORE (Congress for Racial Equality) and other civil rights organizations became something more, a way for Dizzy’s fans to imagine an alternative to the “millionaire’s-only” club represented by Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater.

Gillespie’s campaign had “Dizzy Gillespie for President” buttons, now collector’s items, and “Dizzy for President” became the title of an album recorded live at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1963, from which the recording comes (see right below).

A take on his trademark tune “Salt Peanuts,” “Vote Dizzy” was Gillespie’s official campaign song and includes lyrics like:

Your politics ought to be a groovier thing

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

So get a good president who’s willing to swing

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

October 1st, 2012

OPEN CULTURE

A take on his trademark tune “Salt Peanuts,” “Vote Dizzy” was Gillespie’s official campaign song and includes lyrics like:

Your politics ought to be a groovier thing

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

So get a good president who’s willing to swing

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

It’s definitely groovier than either one of our current campaigns. Dizzy “believed in civil rights, withdrawing from Vietnam and recognizing communist China,” and he wanted to make Miles Davis head of the CIA, a role I think would have suited Miles perfectly. Although Dizzy’s campaign was something of a publicity stunt for his politics and his persona, it’s not unheard of for popular musicians to run for president in earnest. In 1979, revolutionary Nigerian Afrobeat star Fela Kuti put himself forward as a candidate in his country, but was rejected. More recently, Haitian musician and former Fugee Wyclef Jean attempted a sincere run at the Haitian presidency, but was disqualified for reasons of residency. It’s a little hard to imagine a popular musician mounting a serious presidential campaign in the U.S., but then again, the 80s were dominated by the strange reality of a former actor in the White House, so why not? In any case, revisiting Dizzy Gillespie’s mid-century political theater may provide a needed respite from the onslaught of the current U.S. campaign season.

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.

http://www.popmatters.com/review/gillespiedizzy-career1937/

Dizzy Gillespie

Career: 1937-1992

by Will Layman

26 May 2005

PopMatters

Dizzy Gillespie is the greatest post-war musician never to make a truly great album.

Before bebop, of course, musicians did not make “albums”, but merely 78 RPM singles. They recorded these “sides” in batches certainly, but they were not conceived of as groups of songs, and so the great recordings of Armstrong, Ellington, and Hawkins were released piecemeal and today are collected in anthologies that we think of as “great albums.” But Dizzy Gillespie’s contemporaries in the bop movement each birthed a collection of songs that has become representative of their genius—Parker, Monk, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis all made untouchable albums. In the next generation such a feat was essentially required for the greats such as Sonny Rollins (Saxophone Colossus) and John Coltrane (Giant Steps).

Dizzy was as great a musician as any of these figures. Only Pops, Duke, and Trane rival him in importance, and no one—even Armstrong—can touch him as a pure trumpet player. It seems almost a paradox then that a musician who recorded throughout a career that lasted until the early 1990s never made a brilliant album. A handful of Gillespie platters were memorable—Sonny Side Up, Swing Low Sweet Cadillac, Dizzy’s Big Four—and of course he made a few classics with Charlie Parker. But Dizzy’s is a career of innovation, consistency, humor, intelligence, and integrity—but it’s also a career without a single shining moment.

All of this makes Shout Factory’s Career compilation a grand slam—an essential career retrospective from one of the 20th century giants of American music. The lack of a single must-have album from The Diz makes this two-disc set more than just good and better than great. This is theGillespie collection on the market today.

Career is so good because it collects highlights from nearly every phase of Dizzy’s storied career. For those who don’t know the Gillespie legacy, this collection lays it out, tune by tune. Dizzy started as a bright, crazy young trumpet star in the better big bands of the late 1930s. Here, we catch him with Teddy Hill on “King Porter Stomp” (1937), Cab Calloway on his own composition “Pickin’ the Cabbage” (1940), and then with the great Billy Eckstine band from 1944. Diz is clearly a disciple of Roy Eldridge in these early recordings, but the seeds of his own style are in evidence—an ease in the upper register and a penchant for chromaticism as he easily glides from chord to chord.

Dizzy’s career as an innovator, however, really takes off in the small group sides from the mid-‘40s. Career gives us seven sextet recordings from 1945 and ‘46 that show how Dizzy conceived of a bebop sound that came out of swing as much as reacted against it. The version of “I Can’t Get Started” included here is hardly boppish, with a very bland accompaniment, but you can hear Dizzy finding the most interesting notes from the harmony in building his solo. Only two months later, on “Groovin’ High”, Dizzy is teamed up with Charlie “Yardbird” Parker and the sparks are genuinely flying—with the two horns playing the unison head in perfect synch and Dizzy’s muted solo suggesting the puckish humor that would always be part of his style. The three tracks with this line-up (also featuring Slam Stewart on bass and Cozy Cole’s drums) are stone gems, none better than “Dizzy Atmosphere”, where the flow from Bird’s solo to Dizzy demonstrates why Dizzy said of Parker, “He is the other half of my heartbeat.”

While Dizzy’s small group work is justifiably famous, he did not abandon the big band sound as he was helping to invent bebop. Here, we get a heaping dose of Dizzy’s late-‘40s big band—particularly the sides that introduced the concept of Afro-Cuban jazz, featuring Chano Pozo on congas. “Cubano Be/Cubano Bop” and “Manteca” are diamonds that haven’t stopped shimmering in 60 years—brilliant essays in rhythm and arrangement (credited to George Russell and Gil Fuller) that still scream out of your speakers at full throttle. Dizzy’s lead on “Manteca” is one of the great sounds in American music.

When Dizzy returned to small group recordings in the 1950s, the bebop sound was no longer a scandal. “Bloomdido” is essentially from an all-star session with Diz, Bird, Thelonious Monk on piano, Curly Russell on bass and Buddy Rich on drums. There’s nothing to say about music this good other than: listen to it. Dizzy’s solos here, on “Birk’s Works” with Milt Jackson, and on the two tracks from the all-star concert with Bird, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus and Max Roach (“Salt Peanuts” and “Perdido”) are the pinnacle of jazz trumpet playing—virtuosic, subtle, sliding, blue, declamatory and fiendishly clever. It is standing ovation stuff, and don’t be surprised if you find yourself getting to your feet in your living room.

Disc Two of Career moves us into the more workmanlike stage of Dizzy’s career. Like a great physicist, Dizzy did his groundbreaking work early, but the career that followed was special if not consistently revolutionary. During this period, Dizzy recorded a great deal for Norman Grantz’s Verve label, appearing often with “special guests.” The “It Don’t Mean a Thing” included here, with Stan Getz, Roach, and the Oscar Peterson Trio, is a fine example of this kind of one-off meeting working wonderfully well for Dizzy. His solo is like scrambled eggs and salsa—whirling and hot as steam. The “Mean to Me” (1956)with Sonny Stitt and John Lewis shows a more conversational side of Diz, as he cools it, despite a double-time break at the start of this solo that reminds you how much fuel he has in the tank even on a medium swinger.

The later big band recordings are remarkable for their young star line-ups (Lee Morgan, Melba Liston, Al Grey, Benny Golson, Wynton Kelly, among others) and punch. Another from 1975 with Machito’s big band shows that, even late in his career, Dizzy was essentially a lead trumpeter with a bebop soul, riding over an electric bass and team of percussion. Disc Two also features an early ‘60s working group with Lalo Schiffrin on piano that was typical of some of the more faceless bands that Dizzy lead in the latter part of his career, but darn if they aren’t extremely hot recordings, demonstrating that Dizzy was a brilliant bandleader even when his talent was less than top-shelf.

Dizzy performed consistently for more than a half-century and, while this set properly focuses on the ‘40s and ‘50s, it includes two tracks from the great trumpeter’s twilight. “Wheatleigh Hall” pairs him with Cuban disciple Arturo Sandoval. Dizzy’s adoption of Cuban music made him a hero on the island, and Sandoval was one of many Cubans who owe their jazz careers to the Diz. But, as a trumpeter, Sandoval will always be Dizzy’s inferior, even on this 1982 track. The best of Dizzy’s imitators realized that, like Miles Davis, you could apprentice in Dizzy’s high-flying style but it was better to stake out your own ground artistically. Sandoval is a brassy imitation without nearly the humor and sly wit that Dizzy brings to even this late date.

The final track on Career is a tribute date recorded shortly before Dizzy left us to join Bird, Monk, Duke and Pops up above. Dizzy lived one of the longest and most productive lives in jazz. He was and is the role model for young guys in the music—no drug use, married for a half century to one woman, a good businessman, and incomparable combination of showman and artist. In this last recording, he’s frail, and the musician accompanying him surely knew it. But it hardly matters. The group plays the iconic tune “Bebop”—of course, Dizzy wrote it—and when it’s time for the master to take his turn everyone sets a smooth, swinging table for him.

He fumbles some, and the tone is hardly what it once was, but Dizzy still skitters over the changes with grace, a brilliant musical mind picking out the hip notes as it constructs one of his final solos. There’s nothing sad about it—because Dizzy’s life was one of the greatest solos of all.

Will Layman is a writer, teacher and musician living in the Washington, DC area. He is a contributor to National Public Radio and frequently appears as a guest on WNYC's "Soundcheck" as a jazz critic. He plays both funk and jazz in the bars and clubs in and near the nation's capital. His fiction and humor appear in print and online.

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/john-birks-dizzy-gillespie

The Dizzy Gillespie™ Afro Cuban Experience feat. Machito Jr. - Jazzwoche Burghausen 2014

1. Toccata

2. Olé

3. Fiesta Mojo

4. Black Orpheus

5. Tin Tin Deo

John Lee - bass

Freddie Hendrix - trumpet, flugelhorn

Sharel Cassity - alto sax

Tommy Campbell - drums

Roger Squitero - percussion

special guest:

Machito Jr. - percussion

● The Dizzy Gillespie™ Afro Cuban Experience feat. Machito Jr.

Live at 45. Internationale Jazzwoche Burghausen, Wackerhalle, Germany, March 29, 2014

▶ Internationale Jazzwoche Burghausen - Full Length Concerts - http://bit.ly/1BIsmTc

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Dizzy Gillespie | |

|---|---|

Gillespie in concert, Deauville, Normandy, France

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Birks Gillespie |

| Born | October 21, 1917 Cheraw, South Carolina, United States |

| Died | January 6, 1993 (aged 75) Englewood, New Jersey United States |

| Genres | Jazz, bebop, Afro-Cuban jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer |

| Instruments | Trumpet, piano, vocals |

| Years active | 1935–93 |

| Labels | Pablo, RCA Victor, Savoy, Verve |

| Associated acts | Ray Brown, Cab Calloway, Roy Eldridge, J.J. Johnson, James Moody, Chico O'Farrill, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Chano Pozo, Max Roach, Mickey Roker, Sonny Rollins, Lalo Schifrin, Sonny Stitt, William Oscar Smith, John Coltrane |

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (/ɡɨˈlɛspi/; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer and occasional singer.[1]

AllMusic's Scott Yanow wrote, "Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis's emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated [...] Arguably Gillespie is remembered, by both critics and fans alike, as one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time."[2]

Gillespie was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuoso style of Roy Eldridge[3] but adding layers of harmonic complexity previously unheard in jazz. His beret and horn-rimmed spectacles, his scat singing, his bent horn, pouched cheeks and his light-hearted personality were essential in popularizing bebop.[citation needed]

In the 1940s Gillespie, with Charlie Parker, became a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz.[4] He taught and influenced many other musicians, including trumpeters Miles Davis, Jon Faddis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Arturo Sandoval, Lee Morgan,[5] Chuck Mangione,[6] and balladeer Johnny Hartman[5]

Contents

Biography

Early life and career

Gillespie was born in Cheraw, South Carolina the youngest of nine children of James and Lottie Gillespie. James was a local bandleader, so instruments were made available to the children. Gillespie started to play the piano at the age of four. Gillespie's father died when he was was only ten years old. Gillespie taught himself how to play the trombone as well as the trumpet by the age of twelve. From the night he heard his idol, Roy Eldridge, play on the radio, he dreamed of becoming a jazz musician.[7] He received a music scholarship to the Laurinburg Institute in Lauringburg, North Carolina which he attended for two years before accompanying his family when they moved to Philadelphia.[8]

Gillespie's first professional job was with the Frank Fairfax Orchestra in 1935, after which he joined the respective orchestras of Edgar Hayes and Teddy Hill, essentially replacing Roy Eldridge as first trumpet in 1937. Teddy Hill's band was where Gillespie made his first recording, "King Porter Stomp". In August 1937 while gigging with Hayes in Washington D.C., Gillespie met a young dancer named Lorraine Willis who worked a Baltimore–Philadelphia–New York City circuit which included the Apollo Theatre. Willis was not immediately friendly but Gillespie was attracted anyway. The two finally married on May 9, 1940. They remained married until his death in 1993.[9]

Gillespie stayed with Teddy Hill's band for a year, then left and free-lanced with numerous other bands.[5] In 1939, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra, with which he recorded one of his earliest compositions, the instrumental "Pickin' the Cabbage", in 1940. (Originally released on Paradiddle, a 78rpm backed with a co-composition with Cozy Cole, Calloway's drummer at the time, on the Vocalion label, No. 5467).

Tadd Dameron, Mary Lou Williams and Dizzy Gillespie in 1947

After a notorious altercation between the two men, Calloway fired Gillespie in late 1941. The incident is recounted by Gillespie, along with fellow Calloway band members Milt Hinton and Jonah Jones, in Jean Bach's 1997 film, The Spitball Story. Calloway did not approve of Gillespie's mischievous humor, nor of his adventuresome approach to soloing; according to Jones, Calloway referred to it as "Chinese music". During one performance, Calloway saw a spitball land on the stage, and accused Gillespie of having thrown it. Gillespie denied it, and the ensuing argument led to Calloway striking Gillespie, who then pulled out a switchblade knife and charged Calloway. The two were separated by other band members, during which scuffle Calloway was cut on the hand.

During his time in Calloway's band, Gillespie started writing big band music for bandleaders like Woody Herman and Jimmy Dorsey.[5] He then freelanced with a few bands – most notably Ella Fitzgerald's orchestra, composed of members of the late Chick Webb's band, in 1942.

Gilespie avoided serving in World War II. In his Selective Service interview, he told the local board, "in this stage of my life here in the United States whose foot has been in my ass?" He was thereafter classed as 4-F.[10] In 1943, Gillespie joined the Earl Hines band. Composer Gunther Schuller said:

... In 1943 I heard the great Earl Hines band which had Bird in it and all those other great musicians. They were playing all the flatted fifth chords and all the modern harmonies and substitutions and Gillespie runs in the trumpet section work. Two years later I read that that was 'bop' and the beginning of modern jazz ... but the band never made recordings.[11]Gillespie said of the Hines band, "People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit".[12]

Then, Gillespie joined Billy Eckstine's (Earl Hines' long-time collaborator) big band and it was as a member of Eckstine's band that he was reunited with Charlie Parker, a fellow member of Hines's band. In 1945, Gillespie left Eckstine's band because he wanted to play with a small combo. A "small combo" typically comprised no more than five musicians, playing the trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass and drums.

The rise of bebop

Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Brown, Milt Jackson and Timme Rosenkrantz in September 1947, New York

Bebop was known as the first modern jazz style. However, it was unpopular in the beginning and was not viewed as positively as swing music was. Bebop was seen as an outgrowth of swing, not a revolution. Swing introduced a diversity of new musicians in the bebop era like Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, and Gillespie. Through these musicians, a new vocabulary of musical phrases was created.[13] With Charlie Parker, Gillespie jammed at famous jazz clubs like Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House. Charlie Parker's system also held methods of adding chords to existing chord progressions and implying additional chords within the improvised lines.[13]

Gillespie compositions like "Groovin' High", "Woody 'n' You" and "Salt Peanuts" sounded radically different, harmonically and rhythmically, from the swing music popular at the time. "A Night in Tunisia", written in 1942, while Gillespie was playing with Earl Hines' band, is noted for having a feature that is common in today's music, a non-walking bass line.[citation needed] The song also displays Afro-Cuban rhythms.[14] One of their first small-group performances together was only issued in 2005: a concert in New York's Town Hall on June 22, 1945. Gillespie taught many of the young musicians on 52nd Street, including Miles Davis and Max Roach, about the new style of jazz. After a lengthy gig at Billy Berg's club in Los Angeles, which left most of the audience ambivalent or hostile towards the new music, the band broke up. Unlike Parker, who was content to play in small groups and be an occasional featured soloist in big bands, Gillespie aimed to lead a big band himself; his first, unsuccessful, attempt to do this was in 1945.[citation needed]

Gillespie with John Lewis, Cecil Payne, Miles Davis, and Ray Brown, between 1946 and 1948

After his work with Parker, Gillespie led other small combos (including ones with Milt Jackson, John Coltrane, Lalo Schifrin, Ray Brown, Kenny Clarke, James Moody, J.J. Johnson, and Yusef Lateef) and finally put together his first successful big band. Gillespie and his band tried to popularize bop and make Gillespie a symbol of the new music.[15] He also appeared frequently as a soloist with Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic. He also headlined the 1946 independently produced musical revue film Jivin' in Be-Bop.[16]

In 1948 Gillespie was involved in a traffic accident when the bicycle he was riding was bumped by an automobile. He was slightly injured, and found that he could no longer hit the B-flat above high C. He won the case, but the jury awarded him only $1000, in view of his high earnings up to that point.[17]

In 1956 he organized a band to go on a State Department tour of the Middle East which was extremely well received internationally and earned him the nickname "the Ambassador of Jazz".[18][19] During this time, he also continued to lead a big band that performed throughout the United States and featured musicians including Pee Wee Moore and others. This band recorded a live album at the 1957 Newport jazz festival that featured Mary Lou Williams as a guest artist on piano.

Afro-Cuban music

Miriam Makeba and Dizzy Gillespie in concert, Deauville (Normandy, France), July 20, 1991

In the late 1940s, Gillespie was also involved in the movement called Afro-Cuban music, bringing Afro-Latin American music and elements to greater prominence in jazz and even pop music, particularly salsa. Afro-Cuban jazz is based on traditional Afro-Cuban rhythms. Gillespie was introduced to Chano Pozo in 1947 by Mario Bauza, a Latin jazz trumpet player. Chano Pozo became Gillespie's conga drummer for his band. Gillespie also worked with Mario Bauza in New York jazz clubs on 52nd Street and several famous dance clubs such as Palladium and the Apollo Theater in Harlem. They played together in the Chick Webb band and Cab Calloway's band, where Gillespie and Bauza became lifelong friends. Gillespie helped develop and mature the Afro-Cuban jazz style.[20]

Afro-Cuban jazz was considered bebop-oriented, and some musicians classified it as a modern style. Afro-Cuban jazz was successful because it never decreased in popularity and it always attracted people to dance to its unique rhythms.[20] Gillespie's most famous contributions to Afro-Cuban music are the compositions "Manteca" and "Tin Tin Deo" (both co-written with Chano Pozo); he was responsible for commissioning George Russell's "Cubano Be, Cubano Bop", which featured the great but ill-fated Cuban conga player, Chano Pozo. In 1977, Gillespie discovered Arturo Sandoval while researching music during a tour of Cuba.

Later years

Gillespie performing in 1955

His biographer Alyn Shipton quotes Don Waterhouse approvingly that Gillespie in the fifties "had begun to mellow into an amalgam of his entire jazz experience to form the basis of new classicism". Another opinion is that, unlike his contemporary Miles Davis, Gillespie essentially remained true to the bebop style for the rest of his career.[citation needed]

In 1960, he was inducted into the Down Beat magazine's Jazz Hall of Fame.