ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2014/11/jimi-hendrix-1942-1970-legendary.html

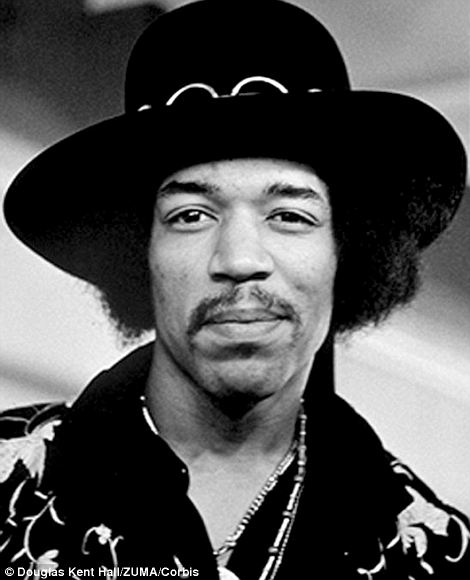

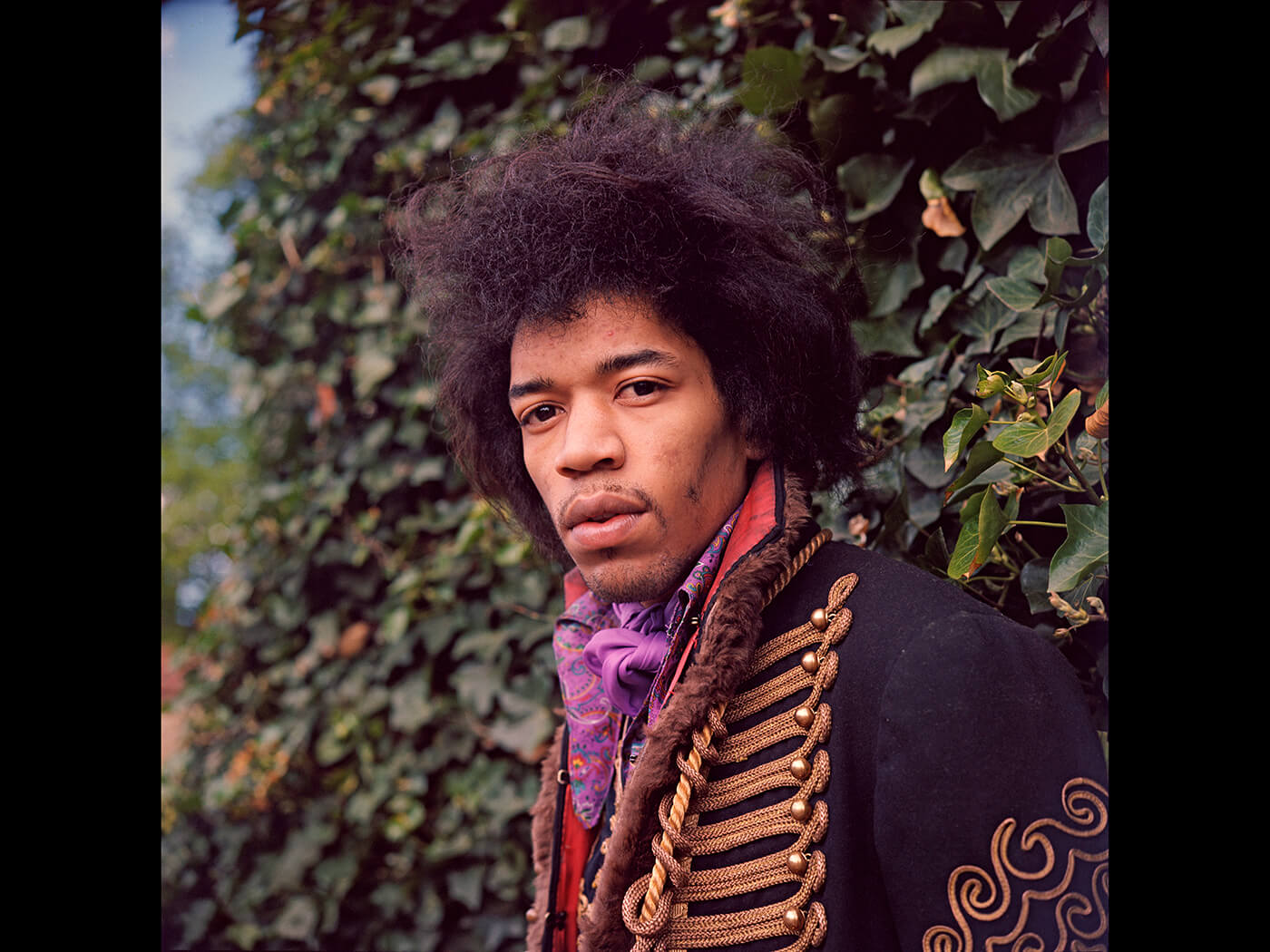

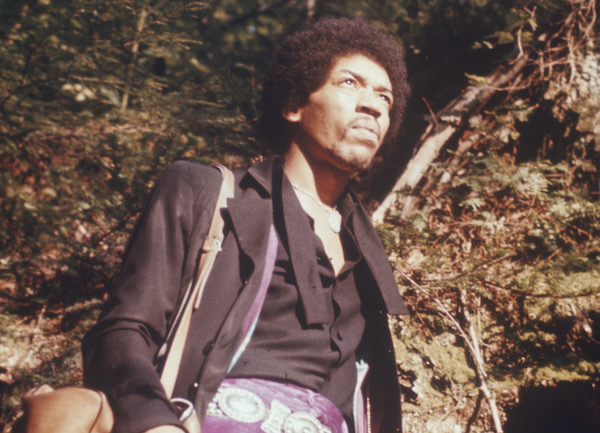

PHOTO: JIMI HENDRIX (1942-1970)

Jimi Hendrix

(1942-1970)

Biography by Richie Unterberger

In his brief four-year reign as a superstar, Jimi Hendrix expanded the vocabulary of the electric rock guitar more than anyone before or since. Hendrix was a master at coaxing all manner of unforeseen sonics from his instrument, often with innovative amplification experiments that produced astral-quality feedback, and roaring distortion. His frequent hurricane blasts of noise and dazzling showmanship -- he could and would play behind his back and with his teeth, and set his guitar on fire -- have sometimes obscured his considerable gifts as a songwriter, singer, and master of a gamut of blues, R&B, and rock styles.

When Hendrix became an international superstar in 1967, it seemed as if he'd dropped out of a Martian spaceship, but in fact he'd served his apprenticeship in numerous R&B acts on the chitlin circuit. During the early and mid-'60s, he worked with such R&B/soul greats as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, and King Curtis as a backup guitarist. Occasionally, he recorded as a sessionman (the Isley Brothers' 1964 single "Testify" is the only one of these early tracks that offers even a glimpse of his future genius). For the most part, his bosses didn't appreciate his show-stealing showmanship, and Hendrix was straitjacketed by sideman roles that didn't allow him to develop as a soloist. The logical step was for him to go out on his own, which he did in New York in the mid-'60s, playing with various musicians in local clubs, and joining white blues-rock singer John Hammond, Jr.'s band for a while.

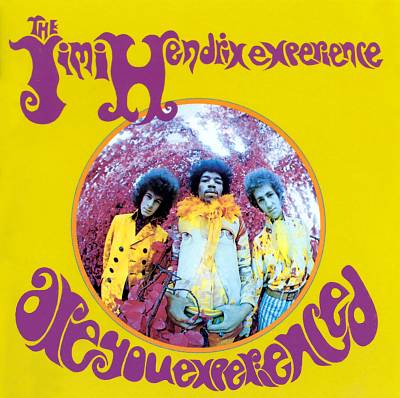

It was in a New York club that Hendrix was spotted by Animals bassist Chas Chandler. The first lineup of the Animalswas about to split, and Chandler, looking to move into management, convinced Hendrix to move to London and record as a solo act in England. There a group was built around Jimi -- featuring Mitch Mitchell on drums and Noel Reddingon bass -- that was dubbed the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The trio became stars with astonishing speed in the U.K., where "Hey Joe," "Purple Haze," and "The Wind Cries Mary" all made the Top Ten in the first half of 1967. These tracks were also featured on their debut album, Are You Experienced?, a psychedelic masterwork that became a huge hit in the U.S. after Hendrix created a sensation at the Monterey Pop Festival in June of 1967.

Are You Experienced? was an astonishing debut, particularly from a young R&B veteran who had rarely sung, and apparently never written his own material before the Experience formed. What caught most people's attention at first was his virtuosic guitar playing, which employed an arsenal of devices, including wah-wah pedals, buzzing feedback solos, crunching, distorted riffs, and lightning-quick liquid runs up and down the scales. Hendrix was also a first-rate songwriter, melding cosmic imagery with some surprisingly pop-savvy hooks and tender sentiments. Are You Experienced? was psychedelia at its most eclectic, synthesizing mod pop, soul, R&B, Dylan, and the electric guitar innovations of British pioneers like Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, and Eric Clapton.

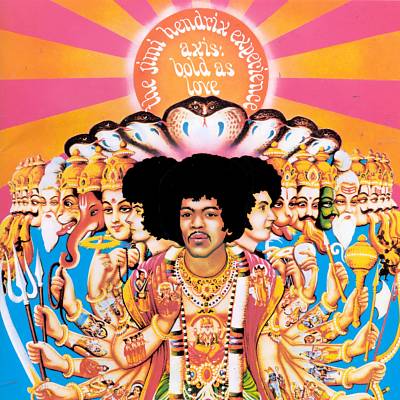

Amazingly, Hendrix would only record three fully conceived studio albums in his lifetime. Axis: Bold as Love and the double-LP Electric Ladyland were more diffuse and experimental than Are You Experienced? On Electric Ladyland in particular, Hendrix pioneered the use of the studio itself as a recording instrument, manipulating electronics and devising overdub techniques (with the help of engineer Eddie Kramer in particular) to plot uncharted sonic territory.

The final two years of Hendrix's life were turbulent ones musically, financially, and personally. He was embroiled in enough complicated management and record company disputes (some dating from ill-advised contracts he'd signed before the Experience formed) to keep the lawyers busy for years. He disbanded the Experience in 1969, forming Band of Gypsys with drummer Buddy Miles and bassist Billy Cox to pursue funkier directions. He closed Woodstock with a sprawling, shaky set, redeemed by his famous machine-gun interpretation of "The Star Spangled Banner." The rhythm section of Mitchell and Redding were underrated keys to Jimi's best work, and Band of Gypsys ultimately couldn't measure up to the same standard, although Hendrix did record an erratic live album with them. In early 1970, the Experience re-formed and disbanded again shortly afterward. At the same time, Hendrix felt torn in many directions by various fellow musicians, record company expectations, and management, all of whom had their own ideas of what Hendrix should be doing. Almost two years since Electric Ladyland, a new studio album had yet to appear, although Hendrix was recording constantly during that period.

While outside parties did contribute to bogging down Hendrix's studio work, it also seems likely that Hendrix himself was partly responsible for the stalemate, unable to form a permanent lineup of musicians, unable to decide what musical direction to pursue, unable to bring himself to complete another album despite endless jamming. A few months into 1970, Mitchell -- Hendrix's most valuable musical collaborator -- came back into the fold, replacing Miles in the drum chair, although Cox stayed in place. It was this trio that toured the world during Hendrix's final months. With them, and many guest musicians, he had been working intermittently on a new album, tentatively titled First Ray of the New Rising Sun, when he died in London on September 18, 1970, from a drug-related overdose.

Hendrix recorded a massive amount of unreleased studio material during his lifetime. Much of this (as well as entire live concerts) was issued posthumously; several of the live concerts were excellent, but the studio tapes have been the focus of enormous controversy for over 20 years. These initially came out in haphazard drabs and drubs (the first, The Cry of Love, was easily the most outstanding of the lot). In the mid-'70s, producer Alan Douglas took control of these projects, overdubbing many of Hendrix's tapes with additional parts by studio musicians. In the eyes of many Hendrix fans, this was sacrilege, destroying the integrity of the work of a musician known to exercise meticulous care over the final production of his studio recordings. Even as late as 1995, Douglas was having ex-Knack drummer Bruce Garyrecord new parts for the compilation Voodoo Soup. After a lengthy legal dispute, the rights to Hendrix's estate, including all of his recordings, returned to Al Hendrix, the guitarist's father, in July of 1995.

With the help of Jimi's stepsister Janie, Al set up Experience Hendrix to put Jimi's legacy in order. They began by hiring John McDermott and Jimi's original engineer, Eddie Kramer, to oversee the remastering process. They were able to find all the original master tapes, which had never been used for previous CD releases, and in April of 1997, Hendrix's first three albums were reissued with drastically improved sound. Accompanying those reissues was a posthumous compilation album (based on Jimi's handwritten track listings) called First Rays of the New Rising Sun, made up of tracks from the Cry of Love, Rainbow Bridge, and War Heroes.

Later in 1997, another compilation called South Saturn Delta showed up, collecting more tracks from posthumous LPs like Crash Landing, War Heroes, and Rainbow Bridge (without the '70s overdubs), along with a handful of never-before-heard material that Chas Chandler had withheld from Alan Douglas for all those years.

More archival material followed. Radio One was basically expanded to the two-disc BBC Sessions (released in 1998), and 1999 saw the release of the full show from Woodstock as well as additional concert recordings from Band of Gypsys shows entitled Live at the Fillmore East. 2000 saw the release of the Jimi Hendrix Experience four-disc box set, which compiled remaining tracks from In the West, Crash Landing, and Rainbow Bridge, along with more rarities and alternates from the Chandler cache.

The family also launched Dagger Records, essentially an authorized bootleg label, to supply hardcore Hendrix fans with material that would be of limited commercial appeal. Dagger released several live concerts (of shows in Oakland, Ottawa, Clark University in Massachusetts, Paris, San Francisco, Woburn in Bedfordshire, and Cologne) and a collection of studio jams and demos called Morning Symphony Ideas.

Mainstream Hendrix reissue activity continued during the 2000s and 2010s, spotlighted by major live albums originally recorded at the Isle of Wight (2002), Berkeley (2003), Monterey (2007), Winterland (2011), and the Miami Pop Festival (2013). In 2010, Sony issued a four-disc set titled West Coast Seattle Boy: The Jimi Hendrix Anthology, which offered a full disc of recordings from Hendrix's time as a backing guitarist.

That same year, Legacy, an imprint of Sony, released Valleys of Neptune. The compilation contained 12 previously unreleased tracks and was the first of many such releases. In 2013, a second compilation appeared. People, Hell and Angels again contained 12 never-before-released songs, which in this case were recorded while Hendrix was working on the follow-up to Electric Ladyland. The final release in this series was put out in 2018, and its ten unreleased tracks also featured guest appearances from Stephen Stills and Johnny Winter.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/jimi-hendrix/

Jimi Hendrix

After leaving the military, Hendrix pursued his music, working as a session musician and playing backup for such performers as Little Richard, Sam Cooke, and the Isley Brothers. He also formed a group of his own called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, which played gigs around New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood. In mid-1966, Hendrix met Chas Chandler, a former member of the Animals, a successful rock group, who became his manager. Chandler convinced Hendrix to go to London where he joined forces with musicians Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell to create The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Released in 1967, the band's first single, “Hey Joe,” was an instant smash in Britain, and soon followed by such other hits as “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cried Mary.” On tour in Europe to support his first album, Are You Experienced?, Hendrix delighted audiences with his outrageous guitar-playing skills and his innovative, experimental sound. He won over American music fans with his stunning performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, which ended with Hendrix lighting his guitar on fire. Quickly becoming a rock music superstar, Hendrix scored again with his second album, Axis: Bold as Love (1968). His final album as part of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Electric Ladyland (1968) was released and featured the hit “All Along the Watchtower,” which was written by Bob Dylan. The band continued to tour until it split up in 1969.

That same year, Hendrix performed at another legendary musical event, the Woodstock Festival. His rock rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” amazed the crowds and demonstrated his considerable talents as a musician. He was also an accomplished songwriter and musical experimenter. Hendrix even had his own recording studio in which he could work with different performers and try out new songs and sounds.

Hendrix tried his luck with another group, forming Band of Gypsys in late 1969 with his army buddy Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles. The band never really took off, and Hendrix began working on a new album tentatively named First Rays of the New Rising Sun, with Cox and Mitch Mitchell from the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Unfortunately Hendrix did not live to complete the project.

Hendrix died on September 18, 1970, from drug-related complications. While this talented recording artist was only 27 at the time of his passing, Hendrix left his mark on the world of rock music and remains popular to this day.

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2014/11/jimi-hendrix-1942-1970-legendary.html

Saturday, November 22, 2014

Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970): Legendary, iconic, and innovative musician, composer, singer, songwriter, arranger, ensemble leader, and teacher

http://www.jimihendrix.com/us/home

http://volume.revues.org/3384?lang=en

See more at:

https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/jimi-hendrix-experience

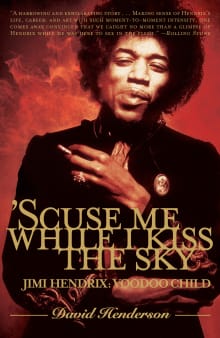

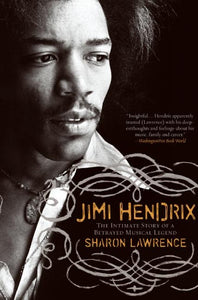

The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary by Chris Potash

New York: Schirmer Books;

Simon and Schuster Macmillan. 1996

The Jimi Hendrix Companion profiles the life and career of this seminal musician through original reviews of Hendrix's music from the British and American press, provides insights into his guitar techniques and recording styles, and invites the reader to construct their own 4-dimensional vision through interviews and scholarly exploration of the Jimi Hendrix phenomenon. Drawing on the work of well-known writers, including Jon Pareles, John Rockwell, Dave Marsh, P.J. O’Rourke, and Lester Bangs, this text provides a perfect introduction to Hendrix, his music, and his times.

The 57 pieces collected here are arranged in seven evenly-weighted chapters. As in Henry James’ evocation of the House of Fiction, each writer layers their view through press reports, two sections of criticism, periodical journalism, a breath-taking section of academic scholarship and a touching final and forward-looking memorial in order to build a panoptic view of their subject.

Potash seeks to "…document and illuminate the phenomenon of Jimi Hendrix as it was and is being played out", and to "…create a charged pastiche of more and less complex verbal constellations that conducts feeling - much like Hendrix’s approach to recording, layering sounds to build a heavy composition - as well as simply to collect some essential writings about Jimi into one volume". Evoked via inspiring, intriguing and multi-layered texts, Hendrix defies reduction to a cipher; as one layer or perspective is revealed, further dimensions unfold.

The strength of the collection is its breadth of scope: each section compliments and contextualises the next, allowing not only Jimi Hendrix but his circumstances to be illustrated from multiple viewpoints. Each chapter opens with a quotation from Jimi himself and, where appropriate, pieces are followed by a bibliography. The whole is supported by a comprehensive index. There is, however, a near-total absence of illustrations or diagrams - the exception to this being the graphic scores that accompany Sheila Whiteley’s brilliant and evocative essay. The text would benefit from imagery as intimate and intricate as some of the pen-portraits and explorations contained here.

From Dawn James’ tentative flirting with Jimi, to frankly baffling evocations of what might-have-been from Lester Bangs and Tom Gogola, the collection is challenging and informative in equal measure. The limitations of language to describe music are evidenced in Paul Suave’s 1968 work, whilst the heady excitement and regal power of Jimi’s presence is sensitively illustrated by Albert Goldman.

Jimi Hendrix emerges from this room full of mirrors remarkably fully-formed, and it is a tribute to Potash’s ability as an editor - and to the skill of the contributing writers - that their subject remains mercurially enigmatic yet engaging throughout. Ultimately, the companion is exactly that: a text which guides and informs the reader and drives them back to the greatest source of primary communion and reference; the music itself. Although out of print, the breadth and finesse of this 1996 volume demonstrates the necessity for an updated second edition that takes into account the influence of the Internet and 21st-century modalities on the Jimi Hendrix legacy. Recent years have seen the release of newly edited films, freshly discovered audio material and the marketing of innumerable digital tools, instruments, musical effects processors and clothing branded with the Hendrix name. As the Companion indicates, Jimi Hendrix is placed in human experience not as a time-locked artefact - but as a nexus of possibilities, and as an axis from which to embark on our own artistic and critical endeavours.

This text is recommended for any scholar or fan with even a passing interest in this remarkable musician and his incalculably influential music. In addition, those researching post-modern notions of intertextuality, identity and the continuing inter-disciplinary and mythological effect of seminal performers by way of posthumous performance and semiological influence will find much to consider and digest within these pages. As with Jimi’s music, this particular collection stands up to repeated reading and extended consultation over time.

References:

Bibliographical reference

Thomas Attah, « Chris Potash, The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary », Volume !, 9 : 2 | 2012, 160-161.

Electronic reference

Thomas Attah, « Chris Potash, The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary », Volume ! [Online], 9 : 2 | 2012, Online since 15 May 2015, connection on 21 November 2014.

URL : http://volume.revues.org/3384

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Tom Attah is a Ph.D. student at the University of Salford. His thesis examines the effects of technological mediation in the Blues. As a guitarist and singer, Tom performs solo, with an acoustic duo and as part of an electric band. Tom's solo acoustic work includes his own original Blues compositions and has lead to performances at major music festivals around Europe, including the Glastonbury Festival of Contemporary Performing Arts, the Great British Rhythm & Blues Festival, Blues Autour Du Zinc and multiple national and local radio appearances. Tom is an Associate Lecturer at the University of Salford, and his blues advocacy includes workshops, seminars, lectures and recitals delivered at secondary school and community level. Tom's writing is regularly featured in Blues In Britain magazine. At present Tom is preparing his original conference papers and book reviews for publication in several international peer-reviewed journals.

https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/

Jimi Hendrix Experience

Biography

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum

Jimi Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music. He expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive, technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll. Hendrix helped usher in the age of psychedelia with his 1967 debut, Are You Experienced?, and the impact of his brief but meteoric career on popular music continues to be felt.

More than any other musician, Jimi Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta blues, acid rock, R&B, soul, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob Dylan and the Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th, 1942, in Seattle. His mother was 17-year-old Lucille Jeter. His father, James “Al” Hendrix, was in the U.S. Army, stationed in Camp Rucker, Alabama, at the time of his son’s birth. Once out of the service, Al would take primary responsibility for raising him. “My dad was very strict and taught me that I must respect my elders always,” Hendrix said of his childhood. “I couldn’t speak unless I was spoken to first by grownups, so I’ve always been very quiet.” Al also formally changed his son’s name to James Marshall Hendrix at age four.

Al Hendrix father bought his son his first guitar, a secondhand acoustic that cost five dollars, when he was 16. “Jimi told me about it and I said, ‘Okay,’ and gave him the money,” Al recalled. “He strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare time he had.” A year later, he bought Jimi an electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560 S, and he joined the Rocking Kings. “My first gig with them was at a National Guard armory,” Hendrix recalled. “We earned like 35 cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the Coasters.” Hendrix, a left-hander, played a right-handed guitar without restringing it, a unique stylistic quirk.

In the summer of 1961, Hendrix enlisted in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord, California, he wrote home: “The Army’s not too bad, so far. . . . All, I mean, all my hair’s cut off and I have to shave. . . .” That fall, he was shipped Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he trained to become a paratrooper. On the side he formed a band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix’s personality made it difficult for him to adapt to the regimented life of a soldier, and in 1962 he was given an honorable discharge.

Following his abortive stint in the Army, Hendrix hit the road with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for such rhythm & blues artists as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, the Impressions, Ike and Tina Turner, and Sam Cooke. In 1965, Hendrix went to New York with Little Richard’s band and over the next several months, he’d play with a variety of musicians, including saxophonist King Curtis. He also took a job with a club band called Curtis Knight and the Squires. Recordings with that group would later be issued on Capitol Records after he achieved fame with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In 1966, Hendrix formed a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. It included 15-year-old Randy Wolfe on guitar. Renamed Randy California by Hendrix, this budding prodigy would later form the group Spirit back home in Los Angeles. Hendrix wrangled a residency lasting several months at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. In 1966, former Animals bassist Chas Chandler caught Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at Café Wha? Chandler quickly became Hendrix’s manager and convinced him to relocate to London. There, Hendrix absorbed the nascent British psychedelic movement, altered the spelling of his first name to “Jimi,” and formed a trio with two British musicians, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. The Jimi Hendrix Experience held its first rehearsal on October 6, 1966 – coincidentally, the very day that possession of LSD became illegal in the U.S. The following week, the Experience undertook a four-day French tour, supporting French pop singer Johnny Hallyday.

Hendrix was an instant sensation in Britain, where he was befriended by such admiring colleagues as Eric Clapton (then playing with Cream). The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first three singles – “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” – all made the British Top ten, with “Purple Haze” peaking at #3. Their May 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced?, became one of the defining releases of the psychedelic movement, reaching #2 in the U.K. and remaining on the British charts for eight months. Released three months later in the U.S. with a slightly amended track lineup, Are You Experienced? proved hugely influential, peaking at #5 and remaining on Billboard’s album chart for two years. The very title of the album posed a challenge – not unlike that issued on the West Coast by Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankers (“Can YOU Pass the Acid Test?) - implicitly acknowledging the notion of enlightenment through psychedelic drugs, with which Hendrix was experimenting.

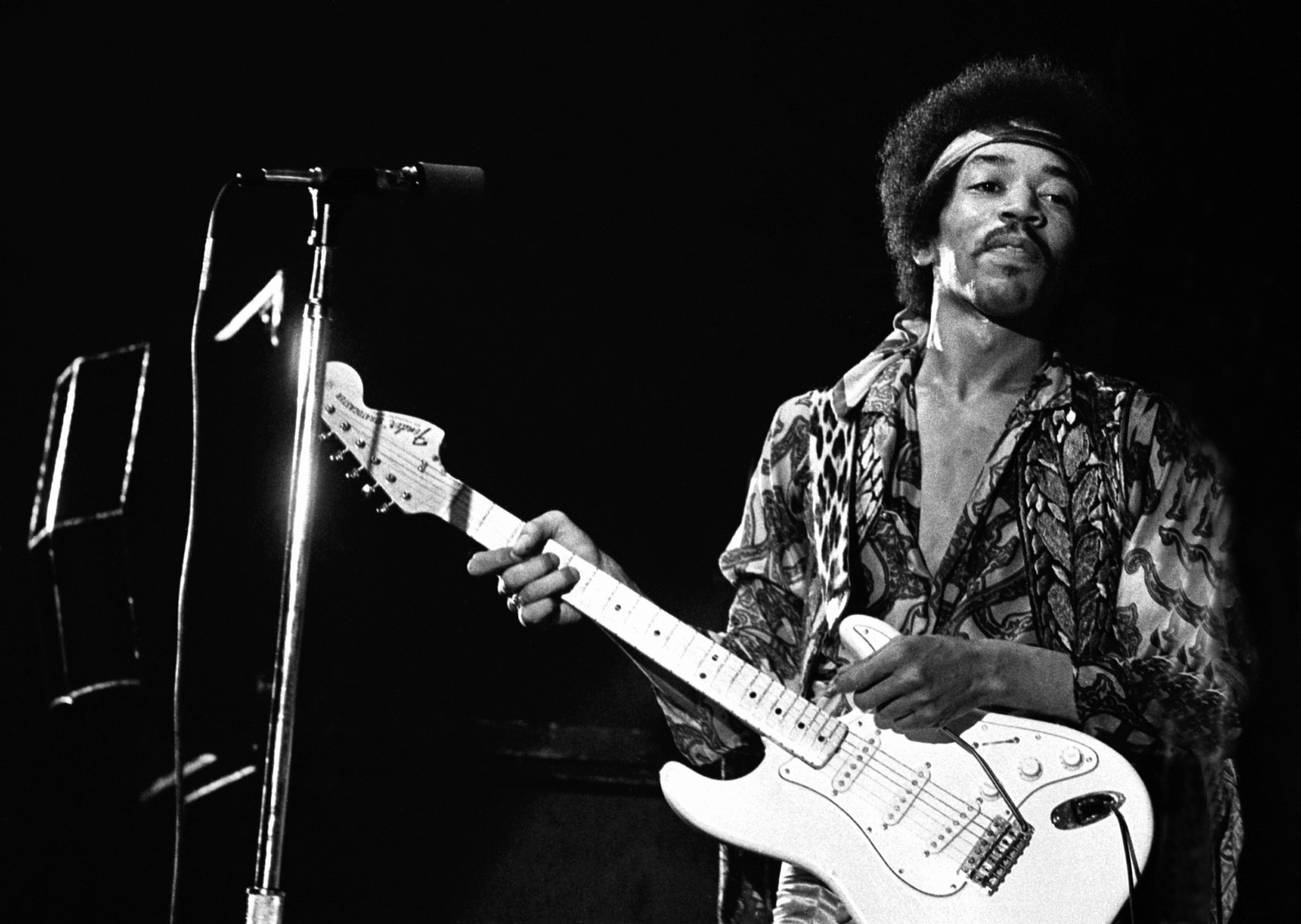

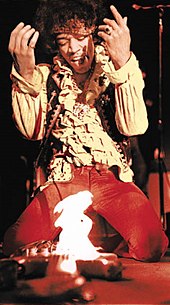

After conquering Britain, Hendrix found fame in his homeland as a result of a memorable performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival – in Monterey, California – on June 18, 1967. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s virtuosity and mastery of the emerging psychedelic style, delivered with flair and theatricality by an exotically attired Hendrix, made him one of the breakout artists of the festival (along with Janis Joplin, Otis Redding and the Who). The Jimi Hendrix Experience played only eight songs at Monterey, but the force of their performance would quickly propel him to fame in this country – thanks, in large part, to his inclusion in D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop film documentary, which included Hendrix’s incendiary finale. After a highly sexualized performance of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” Hendrix set fire to his Fender Stratocaster. “It was like a sacrifice,” Hendrix later explained. “You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar. I’d just finished painting it that day and was really into it.”

Remarkably, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded its three landmark albums - Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland - in a two-year period. Wheras Are You Experienced? was an album of discreet songs, Axis: Bold As Love was constructed as an album-length experience, and it carried Hendrix’s fascination with alien intelligence and otherworldly sounds even further. Both albums were recorded in England, with Chas Chandler producing. For Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience did most of their work in New York at the Record Plant, with Hendrix largely self-producing. Engineer Eddie Kramer, however, was again involved, as he had been for the first two albums.

Electric Ladyland upped the ante yet again, being conceived as a double album with longer tracks divided between earthy blues (such as the nearly 15-minute “Voodoo Chile”) and psychedelic fantasias (such as 1983…A Merman I Should Turn to Be”). Hendrix’s rhythm & blues roots surfaced in “Crosstown Traffic,” which reached Number 52 on the pop chart. One of the highlights of Electric Ladyland was Hendrix’s electric reworking of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” (from John Wesley Harding). “Before I came to England, I was digging a lot of the things Bob Dylan was doing,” Hendrix said. “He is giving me inspiration.” Hendrix’s dynamic new arrangement brought to the fore the portents of apolcalypse in Dylan’s lyrics, and Dylan himself would ultimately perform it much like Hendrix did.

In 1968, Smash Hits, a greatest-hits compendium, was released in Britain; a year later, it appeared in America with an altered track lineup. Meanwhile, a long-simmering schism between Redding and Hendrix, further fueled by Hendrix’s desire to explore other musical areas, led to the disbanding of the Jimi Hendrix Experience after a final performance at the Denver Pop Festival in June 1969. With the Experience defunct, Hendrix debuted a short-lived experimental band called Gypsy Sun & Rainbows at the Woodstock music festival. The group included his old army buddy, Billy Cox, on bass; the Experience’s Mitch Mitchell on drums; Larry Lee on rhythm guitar; and Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez on percussion. He took the stage on 7:30 a.m. on August 18th, 1969. It was the festival’s aftermath, and Hendrix performed a heavily jammed-out set to those stragglers who hadn’t yet left the muddy, garbage-filled site. Hendrix’s freedback-drenched version of “The Star Spangled Banner” was a highlight of the two-hour Woodstock film documentary, as Hendrix evoked the pyrotechnic sounds of war in the jungles of Vietnam as he interpreted the National Anthem for a young and increasingly war-weary generation.

Hendrix’s performances at Monterey and Woodstock have become part of rock and roll legend. What is often overlooked is how hard he worked – or how hard he was worked by his management company – as a touring artist. In the spring of 1968, for instance, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed 63 shows in 66 days. Hendrix commenced work on a projected double album and performed with a new trio, Band of Gypsys – which included bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles - at the Fillmore East on New Year’s Eve 1969 and New Year’s Day 1970. The shows were recorded and culled for relase on Capitol Records as Band of Gypsys, thereby resolving an old contractual debt to the label (dating back to pre-Experience days). Band of Gypsys was the last Hendrix-approved album released in his lifetime.

Under extreme pressure from a combination of hears of nonstop work, sudden celebrity, creative demands and drug-taking, Hendrix was beginning to show signs of exhaustion by 1970. It was evident in his relatively lackluster performance at the Isle of Wight Festival that August. He performed his last concert in Germany on September 6. On September 18, he died from suffocation, having inhaled vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. He was 27 years old.

In the wake of Hendrix’s death, a flood of posthumous albums - everything from old jams from his days as an R&B journeyman to live recordings from his 1967-1970 prime to previously unreleased or unfinished studio work - hit the market. There have been an estimated 100 of them, including The Cry of Love (1971), Rainbow Bridge (1971), War Heroes (1972) and Crash Landing (1975). The best attempt to reconstruct First Rays of the New Rising Sun, and the album Hendrix was working on at the time of his death, came decades later. Assembled from tapes, notes, interviews and song lists by Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer and Hendrix historian John McDermott, it was released on compact disc in 1997.

First Rays of the New Rising Sun appeared on MCA Records in cooperation with Experience Hendrix, the company that was formed by his father, Al Hendrix, and half-sister, Janie Hendrix, after control of his catalog was granted to them in an out-of-court settlement. The 1997 appearance of that disc coincided with remasters of the original studio albums – Are You Experiencd?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland – prepared for CD using the original two-track master tapes. There have subsequently been numerous reissues and newly issued archival works by Hendrix, including concert recordings, by Experience Hendrix.

https://www.jimihendrix.com/jimi/

James Marshall Hendrix

November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970

Jimi Hendrix, born Johnny Allen Hendrix at 10:15 a.m. on November 27, 1942, at Seattle’s King County Hospital, was later renamed James Marshall by his father, James “Al” Hendrix. Young Jimmy (as he was referred to at the time) took an interest in music, drawing influence from virtually every major artist at the time, including B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Holly, and Robert Johnson. Entirely self-taught, Jimmy’s inability to read music made him concentrate even harder on the music he heard.

Al took notice of Jimmy’s interest in the guitar, recalling, “I used to have Jimmy clean up the bedroom all the time while I was gone, and when I would come home I would find a lot of broom straws around the foot of the bed. I’d say to him, `Well didn’t you sweep up the floor?’ and he’d say, `Oh yeah,’ he did. But I’d find out later that he used to be sitting at the end of the bed there and strumming the broom like he was playing a guitar.” Al found an old one-string ukulele, which he gave to Jimmy to play a huge improvement over the broom.

By the summer of 1958, Al had purchased Jimmy a five-dollar, second-hand acoustic guitar from one of his friends. Shortly thereafter, Jimmy joined his first band, The Velvetones. After a three-month stint with the group, Jimmy left to pursue his own interests. The following summer, Al purchased Jimmy his first electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560S; Jimi used it when he joined The Rocking Kings.

In 1961, Jimmy left home to enlist in the United States Army and in November 1962 earned the right to wear the “Screaming Eagles” patch for the paratroop division. While stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, Jimmy formed The King Casuals with bassist Billy Cox. After being discharged due to an injury he received during a parachute jump, Jimmy began working as a session guitarist under the name Jimmy James. By the end of 1965, Jimmy had played with several marquee acts, including Ike and Tina Turner, Sam Cooke, the Isley Brothers, and Little Richard. Jimmy parted ways with Little Richard to form his own band, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, shedding the role of back-line guitarist for the spotlight of lead guitar.

Throughout the latter half of 1965, and into the first part of 1966, Jimmy played the rounds of smaller venues throughout Greenwich Village, catching up with Animals’ bassist Chas Chandler during a July performance at Cafe Wha? Chandler was impressed with Jimmy’s performance and returned again in September 1966 to sign Hendrix to an agreement that would have him move to London to form a new band.

Switching gears from bass player to manager, Chandler’s first task was to change Hendrix’s name to “Jimi.” Featuring drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding, the newly formed Jimi Hendrix Experience quickly became the talk of London in the fall of 1966.

The Experience’s first single, “Hey Joe,” spent ten weeks on the UK charts, topping out at spot No. 6 in early 1967. The debut single was quickly followed by the release of a full-length album Are You Experienced, a psychedelic musical compilation featuring anthems of a generation. Are You Experienced has remained one of the most popular rock albums of all time, featuring tracks like “Purple Haze,” “The Wind Cries Mary,” “Foxey Lady,” “Fire,” and “Are You Experienced?”

Although Hendrix experienced overwhelming success in Britain, it wasn’t until he returned to America in June 1967 that he ignited the crowd at the Monterey International Pop Festival with his incendiary performance of “Wild Thing.” Literally overnight, The Jimi Hendrix Experience became one of most popular and highest grossing touring acts in the world.

Hendrix followed Are You Experienced with Axis: Bold As Love. By 1968, Hendrix had taken greater control over the direction of his music; he spent considerable time working the consoles in the studio, with each turn of a knob or flick of the switch bringing clarity to his vision.

The summer of 1969 brought emotional and musical growth to Jimi Hendrix. In playing the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in August 1969, Jimi joined forces with an eclectic ensemble called Gypsy Sun & Rainbows featuring Jimi Hendrix, Mitch Mitchell, Billy Cox, Juma Sultan, and Jerry Velez. The Woodstock performance was highlighted by the renegade version of “Star Spangled Banner,” which brought the mud-soaked audience to a frenzy.

Nineteen sixty-nine also brought about a new and defining collaboration featuring Jimi Hendrix on guitar, bassist Billy Cox and Electric Flag drummer Buddy Miles. Performing as the Band of Gypsys, this trio launched a series of four New Year’s performances on December 31, 1969 and January 1, 1970. Highlights from these performances were compiled and later released on the quintessential Band of Gypsys album in mid-1970 and the expanded Hendrix: Live At The Fillmore East in 1999.

As 1970 progressed, Jimi brought back drummer Mitch Mitchell to the group and together with Billy Cox on bass, this new trio once again formed The Jimi Hendrix Experience. In the studio, the group recorded several tracks for another two LP set, tentatively titled First Rays Of The New Rising Sun. Unfortunately, Hendrix was unable to see this musical vision through to completion due to his hectic worldwide touring schedules, then tragic death on September 18, 1970. Fortunately, the recordings Hendrix slated for release on the album were finally issued through the support of his family and original studio engineer Eddie Kramer on the 1997 release First Rays Of The New Rising Sun.

From demo recordings to finished masters, Jimi Hendrix generated an amazing collection of songs over the course of his short career. The music of Jimi Hendrix embraced the influences of blues, ballads, rock, R&B, and jazz a collection of styles that continue to make Hendrix one of the most popular figures in the history of rock music.

Home » Jimi

LYRIC # 5

(For Jimi Hendrix)

A million fingers ago

you set the air on fire

and tho you 'fret like mad'

the hollow wooden ship you sail

rides the eternal crest of sound

(in thousands of spiraling waves flying...)

Brother. Safecracker.

You are the submerged marauder

attacking the edge of light

splitting sunclouds

with dancing digital decoders

(stripped layers of interior lovesongs gone)

into the hazy realm of smoke

Those bittersweet mythologies

wrapped in working thumbs and

bleeding

fingernails...

Poem by Kofi Natambu

from the book INTERVALS

Post Aesthetic Press, 1983

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimi_Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

PHOTO: Jimi Hendrix in Nottingham, England, April 20, 1967. Photo from JIMI by Janie Hendrix and John Mc Dermott. Published by Chronicle Chroma. Tony Gale / © Authentic Hendrix, LLC

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, songwriter and singer. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential electric guitarists in the history of popular music, and one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame describes him as "arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music."[1]

Born in Seattle, Washington, Hendrix began playing guitar at age 15. In 1961, he enlisted in the US Army, but was discharged the following year. Soon afterward, he moved to Clarksville then Nashville, Tennessee, and began playing gigs on the chitlin' circuit, earning a place in the Isley Brothers' backing band and later with Little Richard, with whom he continued to work through mid-1965. He then played with Curtis Knight and the Squires before moving to England in late 1966 after bassist Chas Chandler of the Animals became his manager. Within months, Hendrix had earned three UK top ten hits with the Jimi Hendrix Experience: "Hey Joe", "Purple Haze", and "The Wind Cries Mary". He achieved fame in the US after his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and in 1968 his third and final studio album, Electric Ladyland, reached number one in the US. The double LP was Hendrix's most commercially successful release and his first and only number one album. The world's highest-paid performer,[2] he headlined the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970 before his accidental death in London from barbiturate-related asphyxia in September 1970.

Hendrix was inspired by American rock and roll and electric blues. He favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain, and was instrumental in popularizing the previously undesirable sounds caused by guitar amplifier feedback. He was also one of the first guitarists to make extensive use of tone-altering effects units in mainstream rock, such as fuzz distortion, Octavia, wah-wah, and Uni-Vibe. He was the first musician to use stereophonic phasing effects in recordings. Holly George-Warren of Rolling Stone commented: "Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began."[3]

Hendrix was the recipient of several music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year and in 1968, Billboard named him the Artist of the Year and Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year. Disc and Music Echo honored him with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970, Guitar Player named him the Rock Guitarist of the Year. The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. Rolling Stone ranked the band's three studio albums, Are You Experienced (1967), Axis: Bold as Love (1967), and Electric Ladyland (1968), among the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", and they ranked Hendrix as the greatest guitarist and the sixth-greatest artist of all time. Hendrix was named the greatest guitarist of all time by Rolling Stone in 2023.[4]

Ancestry and childhood

Hendrix was of African American and Irish descent. His paternal grandfather, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix, was born in 1866 from an extramarital affair between a woman named Fanny and a grain merchant from Urbana, Ohio, or Illinois, one of the wealthiest men in the area at that time.[5][nb 1] Hendrix's paternal grandmother, Zenora "Nora" Rose Moore, was a former dancer and vaudeville performer who co-founded Fountain Chapel in Hogan's Alley.[7][nb 2] Hendrix and Moore relocated to Vancouver, Canada, where they had a son they named James Allen Hendrix on June 10, 1919; the family called him "Al".[14]

In 1941, after moving to Seattle, Washington, Al met Lucille Jeter (1925–1958) at a dance; they married on March 31, 1942.[15] Lucille's father (Jimi's maternal grandfather) was Preston Jeter (born 1875), whose mother was born in similar circumstances as Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix.[16] Lucille's mother, Clarice (née Lawson), had African-American ancestors who had been enslaved people.[17] Al, who had been drafted by the US Army to serve in World War II, left to begin his basic training three days after the wedding.[18] Johnny Allen Hendrix was born on November 27, 1942, in Seattle; he was the first of Lucille's five children. In 1946, Johnny's parents changed his name to James Marshall Hendrix, in honor of Al and his late brother Leon Marshall.[19][nb 3]

Stationed in Alabama at the time of Hendrix's birth, Al was denied the standard military furlough afforded servicemen for childbirth; his commanding officer placed him in the stockade to prevent him from going AWOL to see his infant son in Seattle. He spent two months locked up without trial, and, while in the stockade, received a telegram announcing his son's birth.[7][nb 4] During Al's three-year absence, Lucille struggled to raise their son.[23] When Al was away, Hendrix was mostly cared for by family members and friends, especially Lucille's sister Delores Hall and her friend Dorothy Harding.[24] Al received an honorable discharge from the US Army on September 1, 1945. Two months later, unable to find Lucille, Al went to the Berkeley, California, home of a family friend named Mrs. Champ, who had taken care of and attempted to adopt Hendrix; this is where Al saw his son for the first time.[25]

After returning from service, Al reunited with Lucille, but his inability to find steady work left the family impoverished. They both struggled with alcohol, and often fought when intoxicated. The violence sometimes drove Hendrix to withdraw and hide in a closet in their home.[26] His relationship with his brother Leon (born 1948) was close but precarious; with Leon in and out of foster care, they lived with an almost constant threat of fraternal separation.[27] In addition to Leon, Hendrix had three younger siblings: Joseph, born in 1949, Kathy in 1950, and Pamela in 1951, all of whom Al and Lucille gave up to foster care and adoption.[28] The family frequently moved, staying in cheap hotels and apartments around Seattle. On occasion, family members would take Hendrix to Vancouver to stay at his grandmother's. A shy and sensitive boy, he was deeply affected by his life experiences.[29] In later years, he confided to a girlfriend that he had been the victim of sexual abuse by a man in uniform.[30] On December 17, 1951, when Hendrix was nine years old, his parents divorced; the court granted Al custody of him and Leon.[31]

First instruments

At Horace Mann Elementary School in Seattle during the mid-1950s, Hendrix's habit of carrying a broom with him to emulate a guitar gained the attention of the school's social worker. After more than a year of his clinging to a broom like a security blanket, she wrote a letter requesting school funding intended for underprivileged children, insisting that leaving him without a guitar might result in psychological damage.[32] Her efforts failed, and Al refused to buy him a guitar.[32][nb 5]

In 1957, while helping his father with a side-job, Hendrix found a ukulele among the garbage they were removing from an older woman's home. She told him that he could keep the instrument, which had only one string.[34] Learning by ear, he played single notes, following along to Elvis Presley songs, particularly "Hound Dog".[35][nb 6] By the age of 33, Hendrix's mother Lucille had developed cirrhosis of the liver, and on February 2, 1958, she died when her spleen ruptured.[37] Al refused to take James and Leon to attend their mother's funeral; he instead gave them shots of whiskey and told them that was how men should deal with loss.[37][nb 7] In 1958, Hendrix completed his studies at Washington Junior High School and began attending, but did not graduate from, Garfield High School.[38][nb 8]

In mid-1958, at age 15, Hendrix acquired his first acoustic guitar, for $5[41] (equivalent to $51 in 2022). He played for hours daily, watching others and learning from more experienced guitarists, and listening to blues artists such as Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Howlin' Wolf, and Robert Johnson.[42] The first tune Hendrix learned to play was the television theme "Peter Gunn".[43] Around that time, Hendrix jammed with boyhood friend Sammy Drain and his keyboard-playing brother.[44] In 1959, attending a concert by Hank Ballard & the Midnighters in Seattle, Hendrix met the group's guitarist Billy Davis.[45] Davis showed him some guitar licks and got him a short gig with the Midnighters.[46] The two remained friends until Hendrix's death in 1970.[47]

Soon after he acquired the acoustic guitar, Hendrix formed his first band, the Velvetones. Without an electric guitar, he could barely be heard over the sound of the group. After about three months, he realized that he needed an electric guitar.[48] In mid-1959, his father relented and bought him a white Supro Ozark.[48] Hendrix's first gig was with an unnamed band in the Jaffe Room of Seattle's Temple De Hirsch, but they fired him between sets for showing off.[49] He joined the Rocking Kings, which played professionally at venues such as the Birdland club. When his guitar was stolen after he left it backstage overnight, Al bought him a red Silvertone Danelectro.[50]

Military service

Before Hendrix was 19 years old, law authorities had twice caught him riding in stolen cars. Given a choice between prison or joining the Army, he chose the latter and enlisted on May 31, 1961.[51] After completing eight weeks of basic training at Fort Ord, California, he was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.[52] He arrived on November 8, and soon afterward he wrote to his father: "There's nothing but physical training and harassment here for two weeks, then when you go to jump school ... you get hell. They work you to death, fussing and fighting."[53] In his next letter home, Hendrix, who had left his guitar in Seattle at the home of his girlfriend Betty Jean Morgan, asked his father to send it to him as soon as possible, stating: "I really need it now."[53] His father obliged and sent the red Silvertone Danelectro on which Hendrix had hand-painted the words "Betty Jean" to Fort Campbell.[54] His apparent obsession with the instrument contributed to his neglect of his duties, which led to taunting and physical abuse from his peers, who at least once hid the guitar from him until he had begged for its return.[55] In November 1961, fellow serviceman Billy Cox walked past an army club and heard Hendrix playing.[56] Impressed by Hendrix's technique, which Cox described as a combination of "John Lee Hooker and Beethoven", Cox borrowed a bass guitar and the two jammed.[57] Within weeks, they began performing at base clubs on the weekends with other musicians in a loosely organized band, the Casuals.[58]

Hendrix completed his paratrooper training and, on January 11, 1962, Major General Charles W. G. Rich awarded him the prestigious Screaming Eagles patch.[53] By February, his personal conduct had begun to draw criticism from his superiors. They labeled him an unqualified marksman and often caught him napping while on duty and failing to report for bed checks.[59] On May 24, Hendrix's platoon sergeant, James C. Spears, filed a report in which he stated: "He has no interest whatsoever in the Army ... It is my opinion that Private Hendrix will never come up to the standards required of a soldier. I feel that the military service will benefit if he is discharged as soon as possible."[60] On June 29, 1962, Hendrix was granted a general discharge under honorable conditions.[61] Hendrix later spoke of his dislike of the army and that he had received a medical discharge after breaking his ankle during his 26th parachute jump,[62][nb 9] but no Army records have been produced that indicate that he received or was discharged for any injuries.[64]

Career

Early years

In September 1962, after Cox was discharged from the Army, he and Hendrix moved about 20 miles (32 km) across the state line from Fort Campbell to Clarksville, Tennessee, and formed a band, the King Kasuals.[65] In Seattle, Hendrix saw Butch Snipes play with his teeth and now the Kasuals' second guitarist, Alphonso "Baby Boo" Young, was performing this guitar gimmick.[66] Not to be upstaged, Hendrix also learned to play in this way. He later explained: "The idea of doing that came to me ... in Tennessee. Down there you have to play with your teeth or else you get shot. There's a trail of broken teeth all over the stage."[67]

Although they began playing low-paying gigs at obscure venues, the band eventually moved to Nashville's Jefferson Street, which was the traditional heart of the city's black community and home to a thriving rhythm and blues music scene.[68] They earned a brief residency playing at a popular venue in town, the Club del Morocco, and for the next two years Hendrix made a living performing at a circuit of venues throughout the South that were affiliated with the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA), widely known as the chitlin' circuit.[69] In addition to playing in his own band, Hendrix performed as a backing musician for various soul, R&B, and blues musicians, including Wilson Pickett, Slim Harpo, Sam Cooke, Ike & Tina Turner[70] and Jackie Wilson.[71]

In January 1964, feeling he had outgrown the circuit artistically, and frustrated by having to follow the rules of bandleaders, Hendrix decided to venture out on his own. He moved into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where he befriended Lithofayne Pridgon, known as "Faye", who became his girlfriend.[72] A Harlem native with connections throughout the area's music scene, Pridgon provided him with shelter, support, and encouragement.[73] Hendrix also met the Allen twins, Arthur and Albert.[74][nb 10] In February 1964, Hendrix won first prize in the Apollo Theater amateur contest.[76] Hoping to secure a career opportunity, he played the Harlem club circuit and sat in with various bands. At the recommendation of a former associate of Joe Tex, Ronnie Isley granted Hendrix an audition that led to an offer to become the guitarist with the Isley Brothers' backing band, the I.B. Specials, which he readily accepted.[77]

First recordings

In March 1964, Hendrix recorded the two-part single "Testify" with the Isley Brothers. Released in June, it failed to chart.[78] In May, he provided guitar instrumentation for the Don Covay song, "Mercy Mercy". Issued in August by Rosemart Records and distributed by Atlantic, the track reached number 35 on the Billboard chart.[79]

Hendrix toured with the Isleys during much of 1964, but near the end of October, after growing tired of playing the same set every night, he left the band.[80][nb 11] Soon afterward, Hendrix joined Little Richard's touring band, the Upsetters.[82] During a stop in Los Angeles in February 1965, he recorded his first and only single with Richard, "I Don't Know What You Got (But It's Got Me)", written by Don Covay and released by Vee-Jay Records.[83] Richard's popularity was waning at the time, and the single peaked at number 92, where it remained for one week before dropping off the chart.[84][nb 12] Hendrix met singer Rosa Lee Brooks while staying at the Wilcox Hotel in Hollywood, and she invited him to participate in a recording session for her single, which included the Arthur Lee penned "My Diary" as the A-side, and "Utee" as the B-side.[86] Hendrix played guitar on both tracks, which also included background vocals by Lee. The single failed to chart, but Hendrix and Lee began a friendship that lasted several years; Hendrix later became an ardent supporter of Lee's band, Love.[86]

In July 1965, Hendrix made his first television appearance on Nashville's Channel 5 Night Train. Performing in Little Richard's ensemble band, he backed up vocalists Buddy and Stacy on "Shotgun". The video recording of the show marks the earliest known footage of Hendrix performing.[82] Richard and Hendrix often clashed over tardiness, wardrobe, and Hendrix's stage antics, and in late July, Richard's brother Robert fired him.[87]

On July 27, Hendrix signed his first recording contract with Juggy Murray at Sue Records and Copa Management.[88][89] He then briefly rejoined the Isley Brothers, and recorded a second single with them, "Move Over and Let Me Dance" backed with "Have You Ever Been Disappointed".[90] Later that year, he joined a New York-based R&B band, Curtis Knight and the Squires, after meeting Knight in the lobby of a hotel where both men were staying.[91] Hendrix performed with them for eight months.[92]

In October 1965, he and Knight recorded the single, "How Would You Feel" backed with "Welcome Home". Despite his two-year contract with Sue,[93] Hendrix signed a three-year recording contract with entrepreneur Ed Chalpin on October 15.[94] While the relationship with Chalpin was short-lived, his contract remained in force, which later caused legal and career problems for Hendrix.[95][nb 13] During his time with Knight, Hendrix briefly toured with Joey Dee and the Starliters, and worked with King Curtis on several recordings including Ray Sharpe's two-part single, "Help Me".[97] Hendrix earned his first composer credits for two instrumentals, "Hornets Nest" and "Knock Yourself Out", released as a Curtis Knight and the Squires single in 1966.[98][nb 14]

Feeling restricted by his experiences as an R&B sideman, Hendrix moved in 1966 to New York City's Greenwich Village, which had a vibrant and diverse music scene.[103] There, he was offered a residency at the Cafe Wha? on MacDougal Street and formed his own band that June, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, which included future Spirit guitarist Randy California.[104][nb 15] The Blue Flames played at several clubs in New York and Hendrix began developing his guitar style and material that he would soon use with the Experience.[106][107] In September, they gave some of their last concerts at the Cafe Au Go Go in Manhattan, as the backing group for a singer and guitarist then billed as John Hammond.[108][nb 16]

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

By May 1966, Hendrix was struggling to earn a living wage playing the R&B circuit, so he briefly rejoined Curtis Knight and the Squires for an engagement at one of New York City's most popular nightspots, the Cheetah Club.[109] During a performance, Linda Keith, the girlfriend of Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards, noticed Hendrix and was "mesmerised" by his playing.[109] She invited him to join her for a drink, and the two became friends.[109]

While Hendrix was playing as Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, Keith recommended him to Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and producer Seymour Stein. They failed to see Hendrix's musical potential, and rejected him.[110] Keith referred him to Chas Chandler, who was leaving the Animals and was interested in managing and producing artists.[111] Chandler saw Hendrix play in Cafe Wha?, a Greenwich Village, New York City nightclub.[111] Chandler liked the Billy Roberts song "Hey Joe", and was convinced he could create a hit single with the right artist.[112] Impressed with Hendrix's version of the song, he brought him to London on September 24, 1966,[113] and signed him to a management and production contract with himself and ex-Animals manager Michael Jeffery.[114] That night, Hendrix gave an impromptu solo performance at The Scotch of St James, and began a relationship with Kathy Etchingham that lasted for two and a half years.[115][nb 17]

Following Hendrix's arrival in London, Chandler began recruiting members for a band designed to highlight his talents, the Jimi Hendrix Experience.[117] Hendrix met guitarist Noel Redding at an audition for the New Animals, where Redding's knowledge of blues progressions impressed Hendrix, who stated that he also liked Redding's hairstyle.[118] Chandler asked Redding if he wanted to play bass guitar in Hendrix's band; Redding agreed.[118] Chandler began looking for a drummer and soon after contacted Mitch Mitchell through a mutual friend. Mitchell, who had recently been fired from Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, participated in a rehearsal with Redding and Hendrix where they found common ground in their shared interest in rhythm and blues. When Chandler phoned Mitchell later that day to offer him the position, he readily accepted.[119] Chandler also convinced Hendrix to change the spelling of his first name from Jimmy to the more exotic Jimi.[120]

On October 1, 1966, Chandler brought Hendrix to the London Polytechnic at Regent Street, where Cream was scheduled to perform, and where Hendrix and guitarist Eric Clapton met.[121] Clapton later said: "He asked if he could play a couple of numbers. I said, 'Of course', but I had a funny feeling about him."[117] Halfway through Cream's set, Hendrix took the stage and performed a frantic version of the Howlin' Wolf song "Killing Floor".[117] In 1989, Clapton described the performance: "He played just about every style you could think of, and not in a flashy way. I mean he did a few of his tricks, like playing with his teeth and behind his back, but it wasn't in an upstaging sense at all, and that was it ... He walked off, and my life was never the same again".[117]

UK success

In mid-October 1966, Chandler arranged an engagement for the Experience as Johnny Hallyday's supporting act during a brief tour of France.[120] Thus, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed their first show on October 13, 1966, at the Novelty in Evreux.[122] Their enthusiastically received 15-minute performance at the Olympia theatre in Paris on October 18 marks the earliest known recording of the band.[120] In late October, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, managers of the Who, signed the Experience to their newly formed label, Track Records, and the group recorded their first song, "Hey Joe", on October 23.[123] "Stone Free", which was Hendrix's first songwriting effort after arriving in England, was recorded on November 2.[124]

From November 8 to 11, 1966, The Jimi Hendrix Experience had a short residency at the Big Apple club in Munich, their first gigs in Germany. At this occasion Hendrix had a show experience that would define him from then on: when trying to escape in panic from a frenetic audience that had pulled him off the stage, he smashed his guitar for the first time in a sound explosion on stage, which was perceived by the audience as part of the show.[125] Observing the audience's reaction, Chandler decided that this show of violence had to become a permanent feature of the Experience's show.[126]

In mid-November, they performed at the Bag O'Nails nightclub in London, with Clapton, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, Brian Jones, Mick Jagger, and Kevin Ayers in attendance.[127] Ayers described the crowd's reaction as stunned disbelief: "All the stars were there, and I heard serious comments, you know 'shit', 'Jesus', 'damn' and other words worse than that."[127] The performance earned Hendrix his first interview, published in Record Mirror with the headline: "Mr. Phenomenon".[127] "Now hear this ... we predict that [Hendrix] is going to whirl around the business like a tornado", wrote Bill Harry, who asked the rhetorical question: "Is that full, big, swinging sound really being created by only three people?"[128] Hendrix said: "We don't want to be classed in any category ... If it must have a tag, I'd like it to be called, 'Free Feeling'. It's a mixture of rock, freak-out, rave and blues".[129] Through a distribution deal with Polydor Records, the Experience's first single, "Hey Joe", backed with "Stone Free", was released on December 16, 1966.[130] After appearances on the UK television shows Ready Steady Go! and Top of the Pops, "Hey Joe" entered the UK charts on December 29 and peaked at number six.[131] Further success came in March 1967 with the UK number three hit "Purple Haze", and in May with "The Wind Cries Mary", which remained on the UK charts for eleven weeks, peaking at number six.[132] On March 12, 1967, he performed at the Troutbeck Hotel, Ilkley, West Yorkshire, where, after about 900 people turned up (the hotel was licensed for 250) the local police stopped the gig due to safety concerns.[133]

On March 31, 1967, while the Experience waited to perform at the London Astoria, Hendrix and Chandler discussed ways in which they could increase the band's media exposure. When Chandler asked journalist Keith Altham for advice, Altham suggested that they needed to do something more dramatic than the stage show of the Who, which involved the smashing of instruments. Hendrix joked: "Maybe I can smash up an elephant", to which Altham replied: "Well, it's a pity you can't set fire to your guitar".[134] Chandler then asked road manager Gerry Stickells to procure some lighter fluid. During the show, Hendrix gave an especially dynamic performance before setting his guitar on fire at the end of a 45-minute set. In the wake of the stunt, members of London's press labeled Hendrix the "Black Elvis" and the "Wild Man of Borneo".[135][nb 18]

An enduring urban legend in the UK maintains that a possible explanation for the feral parakeets that have appeared in Great Britain since the mid-20th century may derive from a single pair of the birds that were released by Hendrix on Carnaby Street in the 1960s.[137][138][139][140] According to a study, however, which mapped historical news reports of sightings of the birds, the myth is not true.[141]

Are You Experienced?

After the UK chart success of their first two singles, "Hey Joe" and "Purple Haze", the Experience began assembling material for a full-length LP.[142] In London, recording began at De Lane Lea Studios, and later moved to the prestigious Olympic Studios.[142] The album, Are You Experienced, features a diversity of musical styles, including blues tracks such as "Red House" and the R&B song "Remember".[143] It also included the experimental science fiction piece, "Third Stone from the Sun" and the post-modern soundscapes of the title track, with prominent backwards guitar and drums.[144] "I Don't Live Today" served as a medium for Hendrix's guitar feedback improvisation and "Fire" was driven by Mitchell's drumming.[142]

Released in the UK on May 12, 1967, Are You Experienced spent 33 weeks on the charts, peaking at number two.[145][nb 19] It was prevented from reaching the top spot by the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[147][nb 20] On June 4, 1967, Hendrix opened a show at the Saville Theatre in London with his rendition of Sgt. Pepper's title track, which was released just three days previous. Beatles manager Brian Epstein owned the Saville at the time, and both George Harrison and Paul McCartney attended the performance. McCartney described the moment: "The curtains flew back and he came walking forward playing 'Sgt. Pepper'. It's a pretty major compliment in anyone's book. I put that down as one of the great honors of my career."[148] Released in the US on August 23 by Reprise Records, Are You Experienced reached number five on the Billboard 200.[149][nb 21]

In 1989, Noe Goldwasser, the founding editor of Guitar World, described Are You Experienced as "the album that shook the world ... leaving it forever changed".[151][nb 22] In 2005, Rolling Stone called the double-platinum LP Hendrix's "epochal debut", and they ranked it the 15th greatest album of all time, noting his "exploitation of amp howl", and characterizing his guitar playing as "incendiary ... historic in itself".[153]

Monterey Pop Festival

Although popular in Europe at the time, the Experience's first US single, "Hey Joe", failed to reach the Billboard Hot 100 chart upon its release on May 1, 1967.[155] Their fortunes improved when McCartney recommended them to the organizers of the Monterey Pop Festival. He insisted that the event would be incomplete without Hendrix, whom he called "an absolute ace on the guitar". McCartney agreed to join the board of organizers on the condition that the Experience perform at the festival in mid-June.[156]

On June 18, 1967,[157] introduced by Brian Jones as "the most exciting performer [he had] ever heard", Hendrix opened with a fast arrangement of Howlin' Wolf's song "Killing Floor", wearing what author Keith Shadwick described as "clothes as exotic as any on display elsewhere".[158] Shadwick wrote: "[Hendrix] was not only something utterly new musically, but an entirely original vision of what a black American entertainer should and could look like."[159] The Experience went on to perform renditions of "Hey Joe", B.B. King's "Rock Me Baby", Chip Taylor's "Wild Thing", and Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone", and four original compositions: "Foxy Lady", "Can You See Me", "The Wind Cries Mary", and "Purple Haze".[148] The set ended with Hendrix destroying his guitar and tossing pieces of it out to the audience.[160] Rolling Stone's Alex Vadukul wrote:

When Jimi Hendrix set his guitar on fire at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival he created one of rock's most perfect moments. Standing in the front row of that concert was a 17-year-old boy named Ed Caraeff. Caraeff had never seen Hendrix before nor heard his music, but he had a camera with him and there was one shot left in his roll of film. As Hendrix lit his guitar, Caraeff took a final photo. It would become one of the most famous images in rock and roll.[161][nb 23]

Caraeff stood on a chair next to the edge of the stage and took four monochrome pictures of Hendrix burning his guitar.[164][nb 24] Caraeff was close enough to the fire that he had to use his camera to protect his face from the heat. Rolling Stone later colorized the image, matching it with other pictures taken at the festival before using the shot for a 1987 magazine cover.[164] According to author Gail Buckland, the final frame of "Hendrix kneeling in front of his burning guitar, hands raised, is one of the most famous images in rock".[164] Author and historian Matthew C. Whitaker wrote that "Hendrix's burning of his guitar became an iconic image in rock history and brought him national attention".[165] The Los Angeles Times asserted that, upon leaving the stage, Hendrix "graduated from rumor to legend".[166] Author John McDermott wrote that "Hendrix left the Monterey audience stunned and in disbelief at what they'd just heard and seen".[167] According to Hendrix: "I decided to destroy my guitar at the end of a song as a sacrifice. You sacrifice things you love. I love my guitar."[168] The performance was filmed by D. A. Pennebaker, and included in the concert documentary Monterey Pop, which helped Hendrix gain popularity with the US public.[169]

After the festival, the Experience was booked for five concerts at Bill Graham's Fillmore, with Big Brother and the Holding Company and Jefferson Airplane. The Experience outperformed Jefferson Airplane during the first two nights, and replaced them at the top of the bill on the fifth.[170] Following their successful West Coast introduction, which included a free open-air concert at Golden Gate Park and a concert at the Whisky a Go Go, the Experience was booked as the opening act for the first American tour of the Monkees.[171] The Monkees requested Hendrix as a supporting act because they were fans, but their young audience disliked the Experience, who left the tour after six shows.[172] Chandler later said he engineered the tour to gain publicity for Hendrix.[173]

Axis: Bold as Love

http://www.bassistbillycox.com/biography2.html

Buddy Miles. Band of Gypsys

Along with fellow friend and star in his own right, drummer Buddy Miles, the friendship of Jimi Hendrix and Billy Cox would forever be etched in music history with the Band of Gypsys. The Band of Gypsys was a power trio that fused blues and hard rock. Rolling Stone Magazine in its 20th anniversary issue in 1987 cited the Band of Gypsys concert as one of the ten greatest concerts of all time.

https://downbeat.com/news/detail/hendrix-paradise

The Jimi Hendrix Experience In Paradise

by Robert Ham

January 22, 2021

Downbeat

PHOTO: There’s something admirable about the Jimi Hendrix estate’s willingness to put their name on Live In Maui, a warts-and-all document. (Photo: Courtesy Experience Hendrix)

As fascinating as it is to hear Live In Maui (Experience Hendrix/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Entertainment 19439799042; 51:34/48:45 ****), a thrilling document of a July 1970 Jimi Hendrix Experience performance for a few dozen fans in a pasture situated near the Haleakala Crater, the story of how this show came to pass is perhaps even more captivating.

Hendrix, drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Billy Cox had a Honolulu stadium gig and some much-needed downtime in Hawaii on their schedule. But instead of relaxing, the trio were coaxed by manager Michael Jeffrey into taking part in Rainbow Bridge—a cockamamie, independent art film—and playing a hastily assembled gig as part of what was dubbed a “vibratory color/sound experiment.”

What maybe helped convince the band to brave 30 m.p.h. winds and a gaggle of people grouped together by their astrological signs was that Jeffrey got Reprise Records to fund the construction of Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios. Or maybe—according to interviews with Chuck Wein, the film’s director, on the DVD accompanying this multidisc set—the guitarist was on board with connecting the “enlightened and unenlightened” via that “rainbow bridge.”

Whatever the case, Hendrix and the Experience gave their all at this unusual gig, which stretched over two sets—one that stuck to familiar tunes like “Foxey Lady” and “Purple Haze,” and another that highlighted material the group recorded for what would have been its fourth studio album. Footage from the performance wound up in the finished film—which also featured a wonderfully grouchy cameo from Hendrix—but, strangely, the 1971 soundtrack was made up entirely of unused studio material.

There’s a notable looseness to the first set that only becomes more pronounced as it moves through its 10 tracks. Mitchell’s playing gets especially ragged, with awkward fills and his struggling to find the downbeat on “Lover Man.” The drummer’s work wasn’t helped by technical issues with the original multitrack recordings and the raging winds that affected several songs. (Mitchell later would rerecord the drum parts for several songs that feature in the performances here.)

By the second set, a measure of stiffness creeps into the group’s playing, underlining how new some of these songs were to the trio. The Experience is still comfortable enough turning “Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)” and “Midnight Lightning” into a medley on the fly, but the punch and swing of funk-infused rockers like “Dolly Dagger” is tempered. The trio also occasionally loses sight of the finish line, as an otherwise wonderful take of “Straight Ahead” seems to crumble toward the end.

There’s definitely something admirable about the Hendrix estate’s willingness to put their name on this warts-and-all document. That decision was made a lot easier thanks to Hendrix’s stellar work here. Even at its shaggiest, his playing is never anything less than electrifying. He especially excels on the slow blues numbers: His solo on “Hear My Train A-Comin’” starts off humbly before he unfurls a furious squall of notes and fuzzed-out chords; and the band’s churning version of “Red House” is filled with the guitarist’s quick melodic curlicues and playful energy.

Whether Hendrix was onstage that afternoon as a favor to his manager or to be part of this proto-New Age experiment can’t ever be made clear—even with the filmed concert footage. What does come across as loudly as the music is just how much he loved playing with Mitchell and Cox, and how much Hendrix enjoyed performing for an audience. When he’s not completely lost in the music or plucking out a solo using his teeth, he looks entirely joyful.

Hendrix’s death less than three months later might cast some small shadow on the ebullience displayed here, but don’t let it linger. Put these discs on repeat and soak in every moment like an afternoon in the Hawaiian sun. DB

This story originally was published in the February 2021 issue of DownBeat.by Bill Milkowski

May 10, 2018

Downbeat

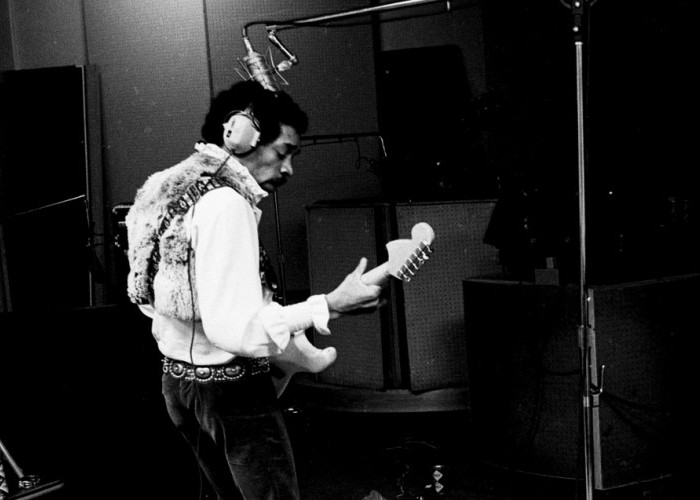

PHOTO: Jimi Hendrix working in the Record Plant Studios in New York on April 21, 1969. (Photo: Willis Hogan Jr. / © MoPOP / Authentic Hendrix, LLC)

Nearly 50 years after his death, Jimi Hendrix’s legacy is still flourishing. Experience Hendrix—the official family company that manages the iconic guitarist’s name, likeness and music—has teamed with Legacy Recordings to release Both Sides Of The Sky. The new album features 13 studio recordings made between 1968 and 1970—including 10 that are previously unreleased.

The third volume in a trilogy of albums intended to present the best and most significant unissued studio recordings remaining in the Hendrix archive, Both Sides Of The Sky is the follow-up to 2013’s People, Hell And Angels and 2010’s Valleys Of Neptune. The new album is of historic importance because it chronicles the first recording session, on April 22, 1969, of Band of Gypsys (Hendrix, bassist Billy Cox, drummer Buddy Miles). The album also includes a previously unreleased version of “Hear My Train A-Comin’,” featuring the guitarist’s bandmates in the Jimi Hendrix Experience: drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding.

The program documents sessions at New York’s Record Plant Studios and includes the instrumental “Jungle” (a variation on Hendrix’s Woodstock Festival anthem “Villanova Junction”); a moody “Cherokee Mist” (featuring Hendrix on Coral sitar guitar); an instrumental of “Angel” (titled “Sweet Angel” here); and a previously unheard original, “Send My Love To Linda,” purportedly written about Linda Keith, the woman who introduced Jimi to his future manager, Chas Chandler.

Guests on Both Sides Of The Sky include Stephen Stills, blues guitar great Johnny Winter (who flaunts some wicked slide chops on a version of Guitar Slim’s “Things I Used To Do”) and saxophonist-vocalist Lonnie Youngblood.

Newly mixed by Eddie Kramer, who served as recording engineer on every Jimi Hendrix album made during the artist’s lifetime, Both Sides Of The Sky was co-produced by Kramer, Janie Hendrix, president and CEO of Experience Hendrix, and John McDermott, catalog manager of Experience Hendrix.

“There are a bunch of songs on the new album that have not been bootlegged,” said McDermott. “Fans will be surprised to hear these recordings.”

“Sweet Angel” sounds like a template for the tune that Hendrix would craft two years later, with vocals and lead guitar, at his Electric Lady Studio. That track appeared on a posthumous 1971 release, The Cry Of Love. Regarding the instrumental rendition, Dermott said: “We felt it revealed an entirely different approach to what he would later redo entirely with the song in 1970. Remember that he really tinkered with this—another early version can be heard on The Jimi Hendrix Experience box set [nicknamed the “purple” box set and released by MCA in 2000]. It serves as a great example that Jimi was changing, adapting, creating all of these songs right up to the last minute. His creativity was relentless, and ‘Sweet Angel’ helps make clear how Jimi would take any path to achieve the creative vision he desired for each song.”

A super-funky studio version of “Power Of Soul,” recorded three weeks after Band of Gypsys’ legendary set at the Fillmore East on Jan. 1, 1970, was mixed by Hendrix and Kramer in August 1970. The version of the mystical “Cherokee Mist” included here takes a much different approach than the one that appeared on the Jimi Hendrix Experience box set.

Hendrix’s version of “Mannish Boy,” an homage to two of his blues heroes, is a hybrid of Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy” and Bo Diddley’s “I’m A Man.” Said McDermott, “This is a very different take than the one that appeared on the Blues compilation [released by MCA in 1994]. It’s much better and more fully realized than that version. ... Jimi sneaks a little of Bo Diddley’s ‘Before You Accuse Me’ during his version of ‘Things I Used To Do’ with Johnny Winter. He obviously dug Bo and it is a nice homage.”

Hendrix died on Sept. 18, 1970, and a few months later, readers voted him into the DownBeat Hall of Fame. Over the decades, his stature has grown and fans have been hungry for additional recordings from his too-short life. While there is still plenty of Hendrix material of varying quality in the vaults, McDermott said that Both Sides Of The Sky represents the cream of the crop.

“These are the recordings that we felt fans should be able to access,” McDermott said. “Hopefully, it provides them with a deeper appreciation and understanding of just how talented Jimi truly was.” DBhttps://downbeat.com/news/detail/revisiting-the-stank-groove-of-jimi-hendrix

by Bill Milkowski

February 10, 2020

Downbeat

Jimi Hendrix’s performances on Dec. 31, 1969, and Jan. 1, 1970, at the Fillmore East in New York rank as a unique moment in the guitarist’s career. (Photo: Allan Herr/MoPOP/Authentic Hendrix, LLC)