SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2014

VOLUME ONE NUMBER ONE

MILES DAVIS

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ANTHONY BRAXTON

November 1-7

CECIL TAYLOR

November 8-14

STEVIE WONDER

November 15-21

JIMI HENDRIX

November 22-28

GERI ALLEN

November 29-December 5

HERBIE HANCOCK

December 6-12

SONNY ROLLINS

December 13-19

JANELLE MONAE

December 20-26

GARY CLARK, JR.

December 27-January 2

NINA SIMONE

January 3-January 9

ORNETTE COLEMAN

January 10-January 16

WAYNE SHORTER

January 17-23

November 1-7

CECIL TAYLOR

November 8-14

STEVIE WONDER

November 15-21

JIMI HENDRIX

November 22-28

GERI ALLEN

November 29-December 5

HERBIE HANCOCK

December 6-12

SONNY ROLLINS

December 13-19

JANELLE MONAE

December 20-26

GARY CLARK, JR.

December 27-January 2

NINA SIMONE

January 3-January 9

ORNETTE COLEMAN

January 10-January 16

WAYNE SHORTER

January 17-23

*[Special bonus feature: A celebration of the centennial year of musician, composer, orchestra leader, and philosopher SUN RA, 1914-1993]

January 24-30

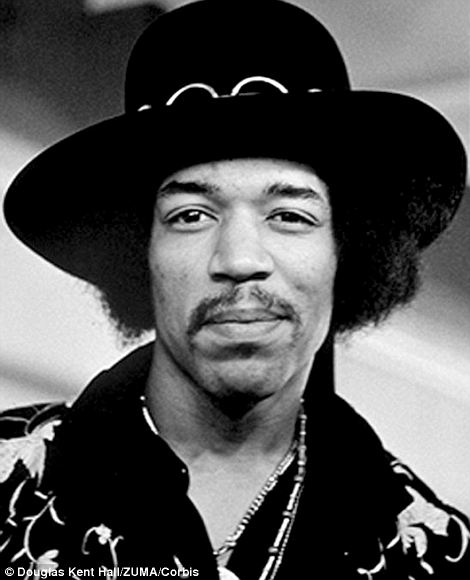

(b. November 27, 1942--d. September 18, 1970)

LYRIC # 5

(For Jimi Hendrix)

A million fingers ago

you set the air on fire

and tho you 'fret like mad'

the hollow wooden ship you sail

rides the eternal crest of sound

(in thousands of spiraling waves flying...)

Brother. Safecracker.

You are the submerged marauder

attacking the edge of light

splitting sunclouds

with dancing digital decoders

(stripped layers of interior lovesongs gone)

into the hazy realm of smoke

Those bittersweet mythologies

wrapped in working thumbs and

bleeding

fingernails...

Poem by Kofi Natambu

from the book INTERVALS

Post Aesthetic Press, 1983

THE MUSIC OF JIMI HENDRIX: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, ESSAYS AND ARTICLES PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH MR. HENDRIX

The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary by Chris Potash

New York: Schirmer Books; Simon and Schuster Macmillan. 1996, ISBN: 0028646096

Few icons

of the 20th century have carved and retain as distinct and influential a

presence on the cultural landscape as James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix. As

a creative performance musician, he not only made incalculable

contributions to defining the voice and presence of the electric guitar

in popular styles, but he also defined new possibilities for blues,

rock, jazz, soul and folk music during a meteoric rise to prominence at

the end of the 1960s. Hendrix is, as Franco Fabbri would indicate, “a

musical event” that impacts not only his own time, but resonates forward

into the present day. This event is presented here as refracted through

the prism of personal experience, reportage and the scrutiny of the

academy.

The

Jimi Hendrix Companion profiles the life and career of this seminal

musician through original reviews of Hendrix's music from the British

and American press, provides insights into his guitar techniques and

recording styles, and invites the reader to construct their own

4-dimensional vision through interviews and scholarly exploration of the

Jimi Hendrix phenomenon. Drawing on the work of well-known writers,

including Jon Pareles, John Rockwell, Dave Marsh, P.J. O’Rourke, and

Lester Bangs, this text provides a perfect introduction to Hendrix, his

music, and his times.

3The

57 pieces collected here are arranged in seven evenly-weighted chapters.

As in Henry James’ evocation of the House of Fiction, each writer

layers their view through press reports, two sections of criticism,

periodical journalism, a breath-taking section of academic scholarship

and a touching final and forward-looking memorial in order to build a

panoptic view of their subject.

Potash

seeks to "…document and illuminate the phenomenon of Jimi Hendrix as it

was and is being played out", and to "…create a charged pastiche of

more and less complex verbal constellations that conducts feeling - much

like Hendrix’s approach to recording, layering sounds to build a heavy

composition - as well as simply to collect some essential writings about

Jimi into one volume". Evoked via inspiring, intriguing and

multi-layered texts, Hendrix defies reduction to a cipher; as one layer

or perspective is revealed, further dimensions unfold.

The

strength of the collection is its breadth of scope: each section

compliments and contextualises the next, allowing not only Jimi Hendrix

but his circumstances to be illustrated from multiple viewpoints. Each

chapter opens with a quotation from Jimi himself and, where appropriate,

pieces are followed by a bibliography. The whole is supported by a

comprehensive index. There is, however, a near-total absence of

illustrations or diagrams - the exception to this being the graphic

scores that accompany Sheila Whiteley’s brilliant and evocative essay.

The text would benefit from imagery as intimate and intricate as some of

the pen-portraits and explorations contained here.

From

Dawn James’ tentative flirting with Jimi, to frankly baffling

evocations of what might-have-been from Lester Bangs and Tom Gogola, the

collection is challenging and informative in equal measure. The

limitations of language to describe music are evidenced in Paul Suave’s

1968 work, whilst the heady excitement and regal power of Jimi’s

presence is sensitively illustrated by Albert Goldman.

Jimi

Hendrix emerges from this room full of mirrors remarkably fully-formed,

and it is a tribute to Potash’s ability as an editor - and to the skill

of the contributing writers - that their subject remains mercurially

enigmatic yet engaging throughout. Ultimately, the companion is exactly

that: a text which guides and informs the reader and drives them back to

the greatest source of primary communion and reference; the music

itself. Although out of print, the breadth and finesse of this 1996

volume demonstrates the necessity for an updated second edition that

takes into account the influence of the Internet and 21st-century

modalities on the Jimi Hendrix legacy. Recent years have seen the

release of newly edited films, freshly discovered audio material and the

marketing of innumerable digital tools, instruments, musical effects

processors and clothing branded with the Hendrix name. As the Companion

indicates, Jimi Hendrix is placed in human experience not as a

time-locked artefact - but as a nexus of possibilities, and as an axis

from which to embark on our own artistic and critical endeavours.

This

text is recommended for any scholar or fan with even a passing interest

in this remarkable musician and his incalculably influential music. In

addition, those researching post-modern notions of intertextuality,

identity and the continuing inter-disciplinary and mythological effect

of seminal performers by way of posthumous performance and semiological

influence will find much to consider and digest within these pages. As

with Jimi’s music, this particular collection stands up to repeated

reading and extended consultation over time.

References

Bibliographical reference

Thomas Attah, « Chris Potash, The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary », Volume !, 9 : 2 | 2012, 160-161.

Electronic reference

Thomas Attah, « Chris Potash, The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary », Volume ! [Online], 9 : 2 | 2012, Online since 15 May 2015, connection on 21 November 2014.URL : http://volume.revues.org/3384

About the author

Thomas Attah

Tom Attah

is a Ph.D. student at the University of Salford. His thesis examines

the effects of technological mediation in the Blues. As a guitarist and

singer, Tom performs solo, with an acoustic duo and as part of an

electric band. Tom's solo acoustic work includes his own original Blues

compositions and has lead to performances at major music festivals

around Europe, including the Glastonbury Festival of Contemporary

Performing Arts, the Great British Rhythm & Blues Festival, Blues

Autour Du Zinc and multiple national and local radio appearances. Tom is

an Associate Lecturer at the University of Salford, and his blues

advocacy includes workshops, seminars, lectures and recitals delivered

at secondary school and community level. Tom's writing is regularly

featured in Blues In Britain magazine. At present Tom is preparing his

original conference papers and book reviews for publication in several

international peer-reviewed journals.

https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/

Jimi Hendrix Experience

Biography

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum

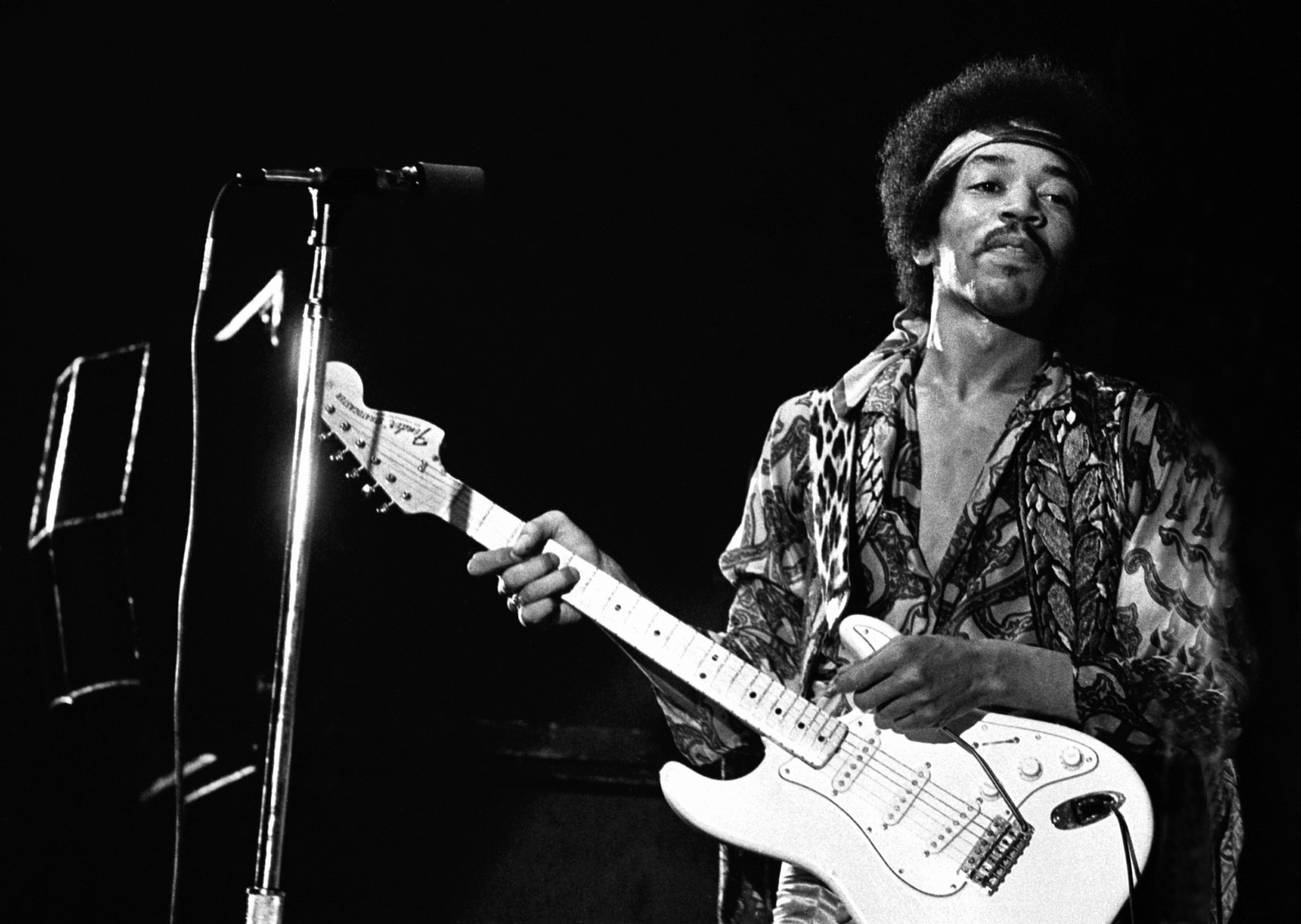

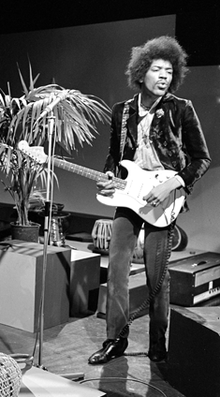

Jimi Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music. He expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive, technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll. Hendrix helped usher in the age of psychedelia with his 1967 debut, Are You Experienced?, and the impact of his brief but meteoric career on popular music continues to be felt.

More than any other musician, Jimi Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta blues, acid rock, R&B, soul, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob Dylan and the Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th, 1942, in Seattle. His mother was 17-year-old Lucille Jeter. His father, James “Al” Hendrix, was in the U.S. Army, stationed in Camp Rucker, Alabama, at the time of his son’s birth. Once out of the service, Al would take primary responsibility for raising him. “My dad was very strict and taught me that I must respect my elders always,” Hendrix said of his childhood. “I couldn’t speak unless I was spoken to first by grownups, so I’ve always been very quiet.” Al also formally changed his son’s name to James Marshall Hendrix at age four.

Al Hendrix father bought his son his first guitar, a secondhand acoustic that cost five dollars, when he was 16. “Jimi told me about it and I said, ‘Okay,’ and gave him the money,” Al recalled. “He strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare time he had.” A year later, he bought Jimi an electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560 S, and he joined the Rocking Kings. “My first gig with them was at a National Guard armory,” Hendrix recalled. “We earned like 35 cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the Coasters.” Hendrix, a left-hander, played a right-handed guitar without restringing it, a unique stylistic quirk.

In the summer of 1961, Hendrix enlisted in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord, California, he wrote home: “The Army’s not too bad, so far. . . . All, I mean, all my hair’s cut off and I have to shave. . . .” That fall, he was shipped Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he trained to become a paratrooper. On the side he formed a band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix’s personality made it difficult for him to adapt to the regimented life of a soldier, and in 1962 he was given an honorable discharge.

Following his abortive stint in the Army, Hendrix hit the road with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for such rhythm & blues artists as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, the Impressions, Ike and Tina Turner, and Sam Cooke. In 1965, Hendrix went to New York with Little Richard’s band and over the next several months, he’d play with a variety of musicians, including saxophonist King Curtis. He also took a job with a club band called Curtis Knight and the Squires. Recordings with that group would later be issued on Capitol Records after he achieved fame with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In 1966, Hendrix formed a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. It included 15-year-old Randy Wolfe on guitar. Renamed Randy California by Hendrix, this budding prodigy would later form the group Spirit back home in Los Angeles. Hendrix wrangled a residency lasting several months at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. In 1966, former Animals bassist Chas Chandler caught Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at Café Wha? Chandler quickly became Hendrix’s manager and convinced him to relocate to London. There, Hendrix absorbed the nascent British psychedelic movement, altered the spelling of his first name to “Jimi,” and formed a trio with two British musicians, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. The Jimi Hendrix Experience held its first rehearsal on October 6, 1966 – coincidentally, the very day that possession of LSD became illegal in the U.S. The following week, the Experience undertook a four-day French tour, supporting French pop singer Johnny Hallyday.

Hendrix was an instant sensation in Britain, where he was befriended by such admiring colleagues as Eric Clapton (then playing with Cream). The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first three singles – “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” – all made the British Top ten, with “Purple Haze” peaking at #3. Their May 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced?, became one of the defining releases of the psychedelic movement, reaching #2 in the U.K. and remaining on the British charts for eight months. Released three months later in the U.S. with a slightly amended track lineup, Are You Experienced? proved hugely influential, peaking at #5 and remaining on Billboard’s album chart for two years. The very title of the album posed a challenge – not unlike that issued on the West Coast by Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankers (“Can YOU Pass the Acid Test?) - implicitly acknowledging the notion of enlightenment through psychedelic drugs, with which Hendrix was experimenting.

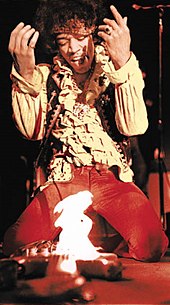

After conquering Britain, Hendrix found fame in his homeland as a result of a memorable performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival – in Monterey, California – on June 18, 1967. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s virtuosity and mastery of the emerging psychedelic style, delivered with flair and theatricality by an exotically attired Hendrix, made him one of the breakout artists of the festival (along with Janis Joplin, Otis Redding and the Who). The Jimi Hendrix Experience played only eight songs at Monterey, but the force of their performance would quickly propel him to fame in this country – thanks, in large part, to his inclusion in D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop film documentary, which included Hendrix’s incendiary finale. After a highly sexualized performance of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” Hendrix set fire to his Fender Stratocaster. “It was like a sacrifice,” Hendrix later explained. “You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar. I’d just finished painting it that day and was really into it.”

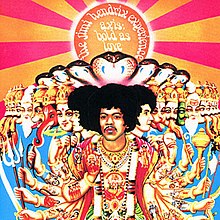

Remarkably, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded its three landmark albums - Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland - in a two-year period. Wheras Are You Experienced? was an album of discreet songs, Axis: Bold As Love was constructed as an album-length experience, and it carried Hendrix’s fascination with alien intelligence and otherworldly sounds even further. Both albums were recorded in England, with Chas Chandler producing. For Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience did most of their work in New York at the Record Plant, with Hendrix largely self-producing. Engineer Eddie Kramer, however, was again involved, as he had been for the first two albums.

Electric Ladyland upped the ante yet again, being conceived as a double album with longer tracks divided between earthy blues (such as the nearly 15-minute “Voodoo Chile”) and psychedelic fantasias (such as 1983…A Merman I Should Turn to Be”). Hendrix’s rhythm & blues roots surfaced in “Crosstown Traffic,” which reached Number 52 on the pop chart. One of the highlights of Electric Ladyland was Hendrix’s electric reworking of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” (from John Wesley Harding). “Before I came to England, I was digging a lot of the things Bob Dylan was doing,” Hendrix said. “He is giving me inspiration.” Hendrix’s dynamic new arrangement brought to the fore the portents of apolcalypse in Dylan’s lyrics, and Dylan himself would ultimately perform it much like Hendrix did.

In 1968, Smash Hits, a greatest-hits compendium, was released in Britain; a year later, it appeared in America with an altered track lineup. Meanwhile, a long-simmering schism between Redding and Hendrix, further fueled by Hendrix’s desire to explore other musical areas, led to the disbanding of the Jimi Hendrix Experience after a final performance at the Denver Pop Festival in June 1969. With the Experience defunct, Hendrix debuted a short-lived experimental band called Gypsy Sun & Rainbows at the Woodstock music festival. The group included his old army buddy, Billy Cox, on bass; the Experience’s Mitch Mitchell on drums; Larry Lee on rhythm guitar; and Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez on percussion. He took the stage on 7:30 a.m. on August 18th, 1969. It was the festival’s aftermath, and Hendrix performed a heavily jammed-out set to those stragglers who hadn’t yet left the muddy, garbage-filled site. Hendrix’s freedback-drenched version of “The Star Spangled Banner” was a highlight of the two-hour Woodstock film documentary, as Hendrix evoked the pyrotechnic sounds of war in the jungles of Vietnam as he interpreted the National Anthem for a young and increasingly war-weary generation.

Hendrix’s performances at Monterey and Woodstock have become part of rock and roll legend. What is often overlooked is how hard he worked – or how hard he was worked by his management company – as a touring artist. In the spring of 1968, for instance, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed 63 shows in 66 days. Hendrix commenced work on a projected double album and performed with a new trio, Band of Gypsys – which included bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles - at the Fillmore East on New Year’s Eve 1969 and New Year’s Day 1970. The shows were recorded and culled for relase on Capitol Records as Band of Gypsys, thereby resolving an old contractual debt to the label (dating back to pre-Experience days). Band of Gypsys was the last Hendrix-approved album released in his lifetime.

Under extreme pressure from a combination of hears of nonstop work, sudden celebrity, creative demands and drug-taking, Hendrix was beginning to show signs of exhaustion by 1970. It was evident in his relatively lackluster performance at the Isle of Wight Festival that August. He performed his last concert in Germany on September 6. On September 18, he died from suffocation, having inhaled vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. He was 27 years old.

In the wake of Hendrix’s death, a flood of posthumous albums - everything from old jams from his days as an R&B journeyman to live recordings from his 1967-1970 prime to previously unreleased or unfinished studio work - hit the market. There have been an estimated 100 of them, including The Cry of Love (1971), Rainbow Bridge (1971), War Heroes (1972) and Crash Landing (1975). The best attempt to reconstruct First Rays of the New Rising Sun, and the album Hendrix was working on at the time of his death, came decades later. Assembled from tapes, notes, interviews and song lists by Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer and Hendrix historian John McDermott, it was released on compact disc in 1997.

First Rays of the New Rising Sun appeared on MCA Records in cooperation with Experience Hendrix, the company that was formed by his father, Al Hendrix, and half-sister, Janie Hendrix, after control of his catalog was granted to them in an out-of-court settlement. The 1997 appearance of that disc coincided with remasters of the original studio albums – Are You Experiencd?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland – prepared for CD using the original two-track master tapes. There have subsequently been numerous reissues and newly issued archival works by Hendrix, including concert recordings, by Experience Hendrix.

- See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/#sthash.2yzlBRfj.dpuf

Jimi Hendrix's Greatest Hits - The Best Of Jimi Hendrix

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1DPKbrANF4Jimi Hendrix - Live At The LA Forum 1970:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVN9-Q2pjBE&list=PLq6rYir1crFnR4dajvIdwZtEtbkI6u0FH&index=2

POET AND HISTORIAN DAVID HENDERSON INTERVIEWED ABOUT HIS BOOK ON HENDRIX "S'CUSE ME WHILE I KISS THE SKY" on CACE INTERNATIONAL TV:

David

Henderson wrote the best selling Jimi Hendrix biography, S'CUSE ME

WHILE I KISS THE SKY. His was the 2nd show in the CACE INTL TV Jimi

Hendrix Series and was filmed before the Hendrix family gained control

of his estate. David has written an up-dated version that deals in

details the last days of Jimi in London and what happened.

We plan to interview Mr. Henderson again.

CACE INT'L TV, a 30 minute show, airs online weekly on Wednesday @ www.BRICartsmedia.org (MEDIA / Brooklyn Public Network, channel 1) , on BPN Cable in Brooklyn,NY, on Verizon Fios in all of NYC @ 1:30 pm & 9:30 pm (New York time). As cultural historians, CACE INT'L TV showcases the art , music and culture of our international creative artists, continuing to bring the best to our international audience.

"Together", the theme music for the CACE INT'L TV Show, is composed and performed specifically for the show by Harry Whitaker.

We plan to interview Mr. Henderson again.

CACE INT'L TV, a 30 minute show, airs online weekly on Wednesday @ www.BRICartsmedia.org (MEDIA / Brooklyn Public Network, channel 1) , on BPN Cable in Brooklyn,NY, on Verizon Fios in all of NYC @ 1:30 pm & 9:30 pm (New York time). As cultural historians, CACE INT'L TV showcases the art , music and culture of our international creative artists, continuing to bring the best to our international audience.

"Together", the theme music for the CACE INT'L TV Show, is composed and performed specifically for the show by Harry Whitaker.

David Henderson,author of Jimi Hendrix biography Part 2 (Hendrix Series part 22) on CACE INT'L TV:

This

is part two of the Jan. 25, 2014 interview with David Henderson the

best selling author of the book; 'Scuse Me While I Kiss The Sky; Jimi

Hendrix: Voodoo Child. Here he talks about people in Jimi's life and his

final day on the planet. This show will air in the spring of 2014.

CACE

INT'L TV, a 30 minute show, airs online weekly on Wednesday @

www.BRICartsmedia.org (MEDIA / Brooklyn Public Network, channel 1) , on

BPN 1 Cable in Brooklyn,NY, on Verizon Fios in all of NYC @ 1:30 pm

& 9:30 pm (New York time). As cultural historians, CACE INT'L TV

showcases the art , music and culture of our international creative

artists, continuing to bring the best to our international audience.

"Together", the theme music for the CACE INT'L TV Show, is composed and performed specifically for the show by Harry Whitaker.

For more information: WWW.CACEINTERNATIONAL.COM

WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/CACEINT'LTVSHOW

"Together", the theme music for the CACE INT'L TV Show, is composed and performed specifically for the show by Harry Whitaker.

For more information: WWW.CACEINTERNATIONAL.COM

WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/CACEINT'LTVSHOW

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Jimi Hendrix Drifting

When Jimi Hendrix died in 1970, over forty years ago this month, I was

in high school. It was a time when a number of key pop figures – all in

their twenties – never got to see thirty. A year earlier, it was Brian

Jones of The Stones, and Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison would soon follow

Hendrix to the grave. Besides sobering you with a taste of death's

final victory (right at that moment when you saw nothing but life

straight ahead), you also realized that a person's genius, their gifts,

even their youth, could do nothing to protect them.

Hendrix's death hit me harder than the others because I came to truly love the paradoxical nature of his music. (In a song that fundamentally came out of the blues like "Burning of the Midnight Lamp," he combined a harpsichord with a wah-wah electric guitar and a chorale section to create a powerfully intense emotional soundscape.) Although Jimi Hendrix was always fully recognized as a virtuoso and theatrical guitar stylist, he was rarely discussed in any great depth in terms of his gifts as a poet, singer and music innovator. (For those insights, it's best to read David Henderson's 1978 biography 'Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky which still hasn't been equalled.) But John Morthland, writing in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, captured key aspects of those many gifts that Henderson elaborates on. "As a guitarist, Hendrix quite simply redefined the instrument, in the same way that Cecil Taylor redefined the piano or John Coltrane the tenor sax," he wrote. "As a songwriter, Hendrix was capable of startling, mystical imagery as well as the down-to-earth sexual allusions of the bluesman." Those sexual allusions though also led to a particular kind of theatricality that the artist himself was growing tired of indulging. Joni Mitchell, who met Hendrix in Ottawa towards the end of his life, recognized immediately his frustration about the public and critical perception of him based on those sexual allusions. "He made his reputation by setting his guitar on fire, but that eventually became repugnant to him," Mitchell told The Guardian in 1970. "'I can't stand to do that anymore,' he said, 'but they've come to expect it. I'd like to just stand still'."

The last album he was preparing when he died, which first came out posthumously in 1971 as The Cry of Love, features plenty of songs where he is indeed 'standing still.' The material on it draws essentially from tracks he had been recording between March 1968 and August 1970. While he was then preparing a visionary double-album work to be titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun (which would eventually come out on CD in 1997 with additional tracks not included on The Cry of Love), his death and various contractual issues prevented the release at that time. John McDermott in his liner notes for the First Rays CD, acknowledging the unfinished state of the album, clearly outlines Hendrix's intent. "With full faith in his music, Hendrix was primed to introduce his audience to a new frontier, where the triumphs of his past would merge freely with his unique blending of rock with rhythm and blues." As McDermott states, the work from these sessions were split up among three albums: The Cry of Love, Rainbow Bridge (1971) and War Heroes (1972). Of the three albums, The Cry of Love is the more sustained and satisfying work.

Although The Cry of Love remains a somewhat uneven record, the working out of his own personal isolation resonates in many of its best tracks like the ripping "Ezy Ryder," the lilting "Angel," the gospel fury of "In From the Storm," his Dylanesque "My Friend," and his tip of the hat to Skip James in the country blues demo of "Belly Button Window." "Ezy Ryder," which was recorded in December 1969, was obviously inspired by the hit counter-culture film (Easy Rider) from earlier that summer. But the song, the only one on the record recorded by Hendrix's funk trio known as the Band of Gypsys (including Billy Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums), strips away the underlying masochism and paranoia that inspired the picture's theme (and made it such a hit) to arrive at something far more poignant. "There goes ezy ryder," Hendrix cries out as Buddy Miles attacks his drum kit as if firing heavy nails into it with a machine gun as he rides wave after wave of Billy Cox's pulsing bass line runs. "Riding down the highway of desire/He says the free wind takes him higher/Searchin' for his Heaven above/But he's dyin' to be loved." While "Ezy Ryder" has all the full-out propulsion of earlier songs like "Manic Depression," "Spanish Castle Magic," or "Crosstown Traffic," the recognition of death isn't brought on by resignation, or the failure of values (as in Peter Fonda's fatalistic proclamation of "We blew it" in the movie), but the desire instead to transcend earthly chains. Martin Luther King would also proclaim recognition of the Promised Land in his final speech a year earlier, a vision that allowed him to face the death he saw coming, so Jimi Hendrix also reaches for the sky in "Ezy Ryder." "He's gonna be livin' so magic," Hendrix sings. "Today is forever so he claims/He's talkin' about dyin' it's so tragic baby/But don't worry about it today/We've got freedom comin' our way."

"Angel" with its more blatant recognition of death's final victory

("Angel came down from Heaven yesterday/She stayed with me just long

enough to rescue me") became the biggest hit from the album, especially

when Rod Stewart covered it in 1972. But the track, as lovely as it is,

is too obvious in its meaning, the metaphors too easy to read: the pop

song as obit. The tune that left me wondering if he indeed saw it all

coming was the exquisite "Drifting." He'd written beautiful ballads

before like "May This Be Love" and "Little Wing," but "Drifting" was

essentially a spiritual, a contemporary interpretation of one that

offered a poignant reckoning of the fact that he knew he was moving on.

"Drifting on a sea of forgotten tear-drops," he sings with a delicate

lilt, a soft crooning that anchors the watery texture of the various

guitar melodies keeping him afloat, "On a lifeboat sailing for your

love." No doubt the wistful qualities within this spiritual were borne

out of its tonal resemblance to Curtis Mayfield's "People Get Ready." In

the song's last moments, where his guitar loops sound like seagulls

taking flight over the water, they echo the cries of liberation those

same loops once called out for in the conclusion of "If Six Was Nine."

But to a different effect. In "Drifting," you can practically see him

waving goodbye as he flies away. Liberated.

John Morthland concludes his piece on Jimi Hendrix contemplating not

only his continuing influence, but also the endless albums and

repackages of both finished and unfinished tunes. "[A]s the years go by,

it also becomes increasingly apparent that Hendrix created a branch on

the pop tree that nobody else has ventured too far out on. None has

actually extended the directions he pursued, but perhaps that is because

he took them, in his painfully short time on earth, as far as they

could go." It also may be true that he took those innovations with him

to the Promised Land.

Hendrix's death hit me harder than the others because I came to truly love the paradoxical nature of his music. (In a song that fundamentally came out of the blues like "Burning of the Midnight Lamp," he combined a harpsichord with a wah-wah electric guitar and a chorale section to create a powerfully intense emotional soundscape.) Although Jimi Hendrix was always fully recognized as a virtuoso and theatrical guitar stylist, he was rarely discussed in any great depth in terms of his gifts as a poet, singer and music innovator. (For those insights, it's best to read David Henderson's 1978 biography 'Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky which still hasn't been equalled.) But John Morthland, writing in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, captured key aspects of those many gifts that Henderson elaborates on. "As a guitarist, Hendrix quite simply redefined the instrument, in the same way that Cecil Taylor redefined the piano or John Coltrane the tenor sax," he wrote. "As a songwriter, Hendrix was capable of startling, mystical imagery as well as the down-to-earth sexual allusions of the bluesman." Those sexual allusions though also led to a particular kind of theatricality that the artist himself was growing tired of indulging. Joni Mitchell, who met Hendrix in Ottawa towards the end of his life, recognized immediately his frustration about the public and critical perception of him based on those sexual allusions. "He made his reputation by setting his guitar on fire, but that eventually became repugnant to him," Mitchell told The Guardian in 1970. "'I can't stand to do that anymore,' he said, 'but they've come to expect it. I'd like to just stand still'."

The last album he was preparing when he died, which first came out posthumously in 1971 as The Cry of Love, features plenty of songs where he is indeed 'standing still.' The material on it draws essentially from tracks he had been recording between March 1968 and August 1970. While he was then preparing a visionary double-album work to be titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun (which would eventually come out on CD in 1997 with additional tracks not included on The Cry of Love), his death and various contractual issues prevented the release at that time. John McDermott in his liner notes for the First Rays CD, acknowledging the unfinished state of the album, clearly outlines Hendrix's intent. "With full faith in his music, Hendrix was primed to introduce his audience to a new frontier, where the triumphs of his past would merge freely with his unique blending of rock with rhythm and blues." As McDermott states, the work from these sessions were split up among three albums: The Cry of Love, Rainbow Bridge (1971) and War Heroes (1972). Of the three albums, The Cry of Love is the more sustained and satisfying work.

Although The Cry of Love remains a somewhat uneven record, the working out of his own personal isolation resonates in many of its best tracks like the ripping "Ezy Ryder," the lilting "Angel," the gospel fury of "In From the Storm," his Dylanesque "My Friend," and his tip of the hat to Skip James in the country blues demo of "Belly Button Window." "Ezy Ryder," which was recorded in December 1969, was obviously inspired by the hit counter-culture film (Easy Rider) from earlier that summer. But the song, the only one on the record recorded by Hendrix's funk trio known as the Band of Gypsys (including Billy Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums), strips away the underlying masochism and paranoia that inspired the picture's theme (and made it such a hit) to arrive at something far more poignant. "There goes ezy ryder," Hendrix cries out as Buddy Miles attacks his drum kit as if firing heavy nails into it with a machine gun as he rides wave after wave of Billy Cox's pulsing bass line runs. "Riding down the highway of desire/He says the free wind takes him higher/Searchin' for his Heaven above/But he's dyin' to be loved." While "Ezy Ryder" has all the full-out propulsion of earlier songs like "Manic Depression," "Spanish Castle Magic," or "Crosstown Traffic," the recognition of death isn't brought on by resignation, or the failure of values (as in Peter Fonda's fatalistic proclamation of "We blew it" in the movie), but the desire instead to transcend earthly chains. Martin Luther King would also proclaim recognition of the Promised Land in his final speech a year earlier, a vision that allowed him to face the death he saw coming, so Jimi Hendrix also reaches for the sky in "Ezy Ryder." "He's gonna be livin' so magic," Hendrix sings. "Today is forever so he claims/He's talkin' about dyin' it's so tragic baby/But don't worry about it today/We've got freedom comin' our way."

– Kevin Courrier is a writer/broadcaster, film critic, teacher and author (Dangerous Kitchen: The Subversive World of Zappa). His forthcoming book is Reflections in the Hall of Mirrors: American Movies and the Politics of Idealism. With John Corcelli, Courrier is currently working on another radio documentary for CBC Radio's Inside the Music called The Other Me: The Avant-Garde Music of Paul McCartney.

Jimi

Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of

rock music. He expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar

into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive,

technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah

and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll. Hendrix

helped usher in the age of psychedelia with his 1967 debut, Are You

Experienced?, and the impact of his brief but meteoric career on popular

music continues to be felt.

More than any other musician, Jimi Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta blues, acid rock, R&B, soul, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob Dylan and the Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th, 1942, in Seattle. His mother was 17-year-old Lucille Jeter. His father, James “Al” Hendrix, was in the U.S. Army, stationed in Camp Rucker, Alabama, at the time of his son’s birth. Once out of the service, Al would take primary responsibility for raising him. “My dad was very strict and taught me that I must respect my elders always,” Hendrix said of his childhood. “I couldn’t speak unless I was spoken to first by grownups, so I’ve always been very quiet.” Al also formally changed his son’s name to James Marshall Hendrix at age four.

Al Hendrix father bought his son his first guitar, a secondhand acoustic that cost five dollars, when he was 16. “Jimi told me about it and I said, ‘Okay,’ and gave him the money,” Al recalled. “He strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare time he had.” A year later, he bought Jimi an electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560 S, and he joined the Rocking Kings. “My first gig with them was at a National Guard armory,” Hendrix recalled. “We earned like 35 cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the Coasters.” Hendrix, a left-hander, played a right-handed guitar without restringing it, a unique stylistic quirk.

In the summer of 1961, Hendrix enlisted in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord, California, he wrote home: “The Army’s not too bad, so far. . . . All, I mean, all my hair’s cut off and I have to shave. . . .” That fall, he was shipped Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he trained to become a paratrooper. On the side he formed a band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix’s personality made it difficult for him to adapt to the regimented life of a soldier, and in 1962 he was given an honorable discharge.

Following his abortive stint in the Army, Hendrix hit the road with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for such rhythm & blues artists as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, the Impressions, Ike and Tina Turner, and Sam Cooke. In 1965, Hendrix went to New York with Little Richard’s band and over the next several months, he’d play with a variety of musicians, including saxophonist King Curtis. He also took a job with a club band called Curtis Knight and the Squires. Recordings with that group would later be issued on Capitol Records after he achieved fame with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In 1966, Hendrix formed a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. It included 15-year-old Randy Wolfe on guitar. Renamed Randy California by Hendrix, this budding prodigy would later form the group Spirit back home in Los Angeles. Hendrix wrangled a residency lasting several months at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. In 1966, former Animals bassist Chas Chandler caught Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at Café Wha? Chandler quickly became Hendrix’s manager and convinced him to relocate to London. There, Hendrix absorbed the nascent British psychedelic movement, altered the spelling of his first name to “Jimi,” and formed a trio with two British musicians, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. The Jimi Hendrix Experience held its first rehearsal on October 6, 1966 – coincidentally, the very day that possession of LSD became illegal in the U.S. The following week, the Experience undertook a four-day French tour, supporting French pop singer Johnny Hallyday.

Hendrix was an instant sensation in Britain, where he was befriended by such admiring colleagues as Eric Clapton (then playing with Cream). The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first three singles – “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” – all made the British Top ten, with “Purple Haze” peaking at #3. Their May 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced?, became one of the defining releases of the psychedelic movement, reaching #2 in the U.K. and remaining on the British charts for eight months. Released three months later in the U.S. with a slightly amended track lineup, Are You Experienced? proved hugely influential, peaking at #5 and remaining on Billboard’s album chart for two years. The very title of the album posed a challenge – not unlike that issued on the West Coast by Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankers (“Can YOU Pass the Acid Test?) - implicitly acknowledging the notion of enlightenment through psychedelic drugs, with which Hendrix was experimenting.

After conquering Britain, Hendrix found fame in his homeland as a result of a memorable performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival – in Monterey, California – on June 18, 1967. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s virtuosity and mastery of the emerging psychedelic style, delivered with flair and theatricality by an exotically attired Hendrix, made him one of the breakout artists of the festival (along with Janis Joplin, Otis Redding and the Who). The Jimi Hendrix Experience played only eight songs at Monterey, but the force of their performance would quickly propel him to fame in this country – thanks, in large part, to his inclusion in D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop film documentary, which included Hendrix’s incendiary finale. After a highly sexualized performance of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” Hendrix set fire to his Fender Stratocaster. “It was like a sacrifice,” Hendrix later explained. “You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar. I’d just finished painting it that day and was really into it.”

Remarkably, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded its three landmark albums - Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland - in a two-year period. Wheras Are You Experienced? was an album of discreet songs, Axis: Bold As Love was constructed as an album-length experience, and it carried Hendrix’s fascination with alien intelligence and otherworldly sounds even further. Both albums were recorded in England, with Chas Chandler producing. For Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience did most of their work in New York at the Record Plant, with Hendrix largely self-producing. Engineer Eddie Kramer, however, was again involved, as he had been for the first two albums.

Electric Ladyland upped the ante yet again, being conceived as a double album with longer tracks divided between earthy blues (such as the nearly 15-minute “Voodoo Chile”) and psychedelic fantasias (such as 1983…A Merman I Should Turn to Be”). Hendrix’s rhythm & blues roots surfaced in “Crosstown Traffic,” which reached Number 52 on the pop chart. One of the highlights of Electric Ladyland was Hendrix’s electric reworking of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” (from John Wesley Harding). “Before I came to England, I was digging a lot of the things Bob Dylan was doing,” Hendrix said. “He is giving me inspiration.” Hendrix’s dynamic new arrangement brought to the fore the portents of apolcalypse in Dylan’s lyrics, and Dylan himself would ultimately perform it much like Hendrix did.

In 1968, Smash Hits, a greatest-hits compendium, was released in Britain; a year later, it appeared in America with an altered track lineup. Meanwhile, a long-simmering schism between Redding and Hendrix, further fueled by Hendrix’s desire to explore other musical areas, led to the disbanding of the Jimi Hendrix Experience after a final performance at the Denver Pop Festival in June 1969. With the Experience defunct, Hendrix debuted a short-lived experimental band called Gypsy Sun & Rainbows at the Woodstock music festival. The group included his old army buddy, Billy Cox, on bass; the Experience’s Mitch Mitchell on drums; Larry Lee on rhythm guitar; and Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez on percussion. He took the stage on 7:30 a.m. on August 18th, 1969. It was the festival’s aftermath, and Hendrix performed a heavily jammed-out set to those stragglers who hadn’t yet left the muddy, garbage-filled site. Hendrix’s freedback-drenched version of “The Star Spangled Banner” was a highlight of the two-hour Woodstock film documentary, as Hendrix evoked the pyrotechnic sounds of war in the jungles of Vietnam as he interpreted the National Anthem for a young and increasingly war-weary generation.

Hendrix’s performances at Monterey and Woodstock have become part of rock and roll legend. What is often overlooked is how hard he worked – or how hard he was worked by his management company – as a touring artist. In the spring of 1968, for instance, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed 63 shows in 66 days. Hendrix commenced work on a projected double album and performed with a new trio, Band of Gypsys – which included bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles - at the Fillmore East on New Year’s Eve 1969 and New Year’s Day 1970. The shows were recorded and culled for relase on Capitol Records as Band of Gypsys, thereby resolving an old contractual debt to the label (dating back to pre-Experience days). Band of Gypsys was the last Hendrix-approved album released in his lifetime.

Under extreme pressure from a combination of hears of nonstop work, sudden celebrity, creative demands and drug-taking, Hendrix was beginning to show signs of exhaustion by 1970. It was evident in his relatively lackluster performance at the Isle of Wight Festival that August. He performed his last concert in Germany on September 6. On September 18, he died from suffocation, having inhaled vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. He was 27 years old.

In the wake of Hendrix’s death, a flood of posthumous albums - everything from old jams from his days as an R&B journeyman to live recordings from his 1967-1970 prime to previously unreleased or unfinished studio work - hit the market. There have been an estimated 100 of them, including The Cry of Love (1971), Rainbow Bridge (1971), War Heroes (1972) and Crash Landing (1975). The best attempt to reconstruct First Rays of the New Rising Sun, and the album Hendrix was working on at the time of his death, came decades later. Assembled from tapes, notes, interviews and song lists by Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer and Hendrix historian John McDermott, it was released on compact disc in 1997.

First Rays of the New Rising Sun appeared on MCA Records in cooperation with Experience Hendrix, the company that was formed by his father, Al Hendrix, and half-sister, Janie Hendrix, after control of his catalog was granted to them in an out-of-court settlement. The 1997 appearance of that disc coincided with remasters of the original studio albums – Are You Experiencd?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland – prepared for CD using the original two-track master tapes. There have subsequently been numerous reissues and newly issued archival works by Hendrix, including concert recordings, by Experience Hendrix.

- See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/#sthash.DYylS3x3.dpuf

More than any other musician, Jimi Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta blues, acid rock, R&B, soul, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob Dylan and the Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th, 1942, in Seattle. His mother was 17-year-old Lucille Jeter. His father, James “Al” Hendrix, was in the U.S. Army, stationed in Camp Rucker, Alabama, at the time of his son’s birth. Once out of the service, Al would take primary responsibility for raising him. “My dad was very strict and taught me that I must respect my elders always,” Hendrix said of his childhood. “I couldn’t speak unless I was spoken to first by grownups, so I’ve always been very quiet.” Al also formally changed his son’s name to James Marshall Hendrix at age four.

Al Hendrix father bought his son his first guitar, a secondhand acoustic that cost five dollars, when he was 16. “Jimi told me about it and I said, ‘Okay,’ and gave him the money,” Al recalled. “He strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare time he had.” A year later, he bought Jimi an electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560 S, and he joined the Rocking Kings. “My first gig with them was at a National Guard armory,” Hendrix recalled. “We earned like 35 cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the Coasters.” Hendrix, a left-hander, played a right-handed guitar without restringing it, a unique stylistic quirk.

In the summer of 1961, Hendrix enlisted in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord, California, he wrote home: “The Army’s not too bad, so far. . . . All, I mean, all my hair’s cut off and I have to shave. . . .” That fall, he was shipped Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he trained to become a paratrooper. On the side he formed a band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix’s personality made it difficult for him to adapt to the regimented life of a soldier, and in 1962 he was given an honorable discharge.

Following his abortive stint in the Army, Hendrix hit the road with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for such rhythm & blues artists as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, the Impressions, Ike and Tina Turner, and Sam Cooke. In 1965, Hendrix went to New York with Little Richard’s band and over the next several months, he’d play with a variety of musicians, including saxophonist King Curtis. He also took a job with a club band called Curtis Knight and the Squires. Recordings with that group would later be issued on Capitol Records after he achieved fame with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In 1966, Hendrix formed a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. It included 15-year-old Randy Wolfe on guitar. Renamed Randy California by Hendrix, this budding prodigy would later form the group Spirit back home in Los Angeles. Hendrix wrangled a residency lasting several months at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. In 1966, former Animals bassist Chas Chandler caught Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at Café Wha? Chandler quickly became Hendrix’s manager and convinced him to relocate to London. There, Hendrix absorbed the nascent British psychedelic movement, altered the spelling of his first name to “Jimi,” and formed a trio with two British musicians, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. The Jimi Hendrix Experience held its first rehearsal on October 6, 1966 – coincidentally, the very day that possession of LSD became illegal in the U.S. The following week, the Experience undertook a four-day French tour, supporting French pop singer Johnny Hallyday.

Hendrix was an instant sensation in Britain, where he was befriended by such admiring colleagues as Eric Clapton (then playing with Cream). The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first three singles – “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” – all made the British Top ten, with “Purple Haze” peaking at #3. Their May 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced?, became one of the defining releases of the psychedelic movement, reaching #2 in the U.K. and remaining on the British charts for eight months. Released three months later in the U.S. with a slightly amended track lineup, Are You Experienced? proved hugely influential, peaking at #5 and remaining on Billboard’s album chart for two years. The very title of the album posed a challenge – not unlike that issued on the West Coast by Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankers (“Can YOU Pass the Acid Test?) - implicitly acknowledging the notion of enlightenment through psychedelic drugs, with which Hendrix was experimenting.

After conquering Britain, Hendrix found fame in his homeland as a result of a memorable performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival – in Monterey, California – on June 18, 1967. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s virtuosity and mastery of the emerging psychedelic style, delivered with flair and theatricality by an exotically attired Hendrix, made him one of the breakout artists of the festival (along with Janis Joplin, Otis Redding and the Who). The Jimi Hendrix Experience played only eight songs at Monterey, but the force of their performance would quickly propel him to fame in this country – thanks, in large part, to his inclusion in D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop film documentary, which included Hendrix’s incendiary finale. After a highly sexualized performance of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” Hendrix set fire to his Fender Stratocaster. “It was like a sacrifice,” Hendrix later explained. “You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar. I’d just finished painting it that day and was really into it.”

Remarkably, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded its three landmark albums - Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland - in a two-year period. Wheras Are You Experienced? was an album of discreet songs, Axis: Bold As Love was constructed as an album-length experience, and it carried Hendrix’s fascination with alien intelligence and otherworldly sounds even further. Both albums were recorded in England, with Chas Chandler producing. For Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience did most of their work in New York at the Record Plant, with Hendrix largely self-producing. Engineer Eddie Kramer, however, was again involved, as he had been for the first two albums.

Electric Ladyland upped the ante yet again, being conceived as a double album with longer tracks divided between earthy blues (such as the nearly 15-minute “Voodoo Chile”) and psychedelic fantasias (such as 1983…A Merman I Should Turn to Be”). Hendrix’s rhythm & blues roots surfaced in “Crosstown Traffic,” which reached Number 52 on the pop chart. One of the highlights of Electric Ladyland was Hendrix’s electric reworking of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” (from John Wesley Harding). “Before I came to England, I was digging a lot of the things Bob Dylan was doing,” Hendrix said. “He is giving me inspiration.” Hendrix’s dynamic new arrangement brought to the fore the portents of apolcalypse in Dylan’s lyrics, and Dylan himself would ultimately perform it much like Hendrix did.

In 1968, Smash Hits, a greatest-hits compendium, was released in Britain; a year later, it appeared in America with an altered track lineup. Meanwhile, a long-simmering schism between Redding and Hendrix, further fueled by Hendrix’s desire to explore other musical areas, led to the disbanding of the Jimi Hendrix Experience after a final performance at the Denver Pop Festival in June 1969. With the Experience defunct, Hendrix debuted a short-lived experimental band called Gypsy Sun & Rainbows at the Woodstock music festival. The group included his old army buddy, Billy Cox, on bass; the Experience’s Mitch Mitchell on drums; Larry Lee on rhythm guitar; and Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez on percussion. He took the stage on 7:30 a.m. on August 18th, 1969. It was the festival’s aftermath, and Hendrix performed a heavily jammed-out set to those stragglers who hadn’t yet left the muddy, garbage-filled site. Hendrix’s freedback-drenched version of “The Star Spangled Banner” was a highlight of the two-hour Woodstock film documentary, as Hendrix evoked the pyrotechnic sounds of war in the jungles of Vietnam as he interpreted the National Anthem for a young and increasingly war-weary generation.

Hendrix’s performances at Monterey and Woodstock have become part of rock and roll legend. What is often overlooked is how hard he worked – or how hard he was worked by his management company – as a touring artist. In the spring of 1968, for instance, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed 63 shows in 66 days. Hendrix commenced work on a projected double album and performed with a new trio, Band of Gypsys – which included bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles - at the Fillmore East on New Year’s Eve 1969 and New Year’s Day 1970. The shows were recorded and culled for relase on Capitol Records as Band of Gypsys, thereby resolving an old contractual debt to the label (dating back to pre-Experience days). Band of Gypsys was the last Hendrix-approved album released in his lifetime.

Under extreme pressure from a combination of hears of nonstop work, sudden celebrity, creative demands and drug-taking, Hendrix was beginning to show signs of exhaustion by 1970. It was evident in his relatively lackluster performance at the Isle of Wight Festival that August. He performed his last concert in Germany on September 6. On September 18, he died from suffocation, having inhaled vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. He was 27 years old.

In the wake of Hendrix’s death, a flood of posthumous albums - everything from old jams from his days as an R&B journeyman to live recordings from his 1967-1970 prime to previously unreleased or unfinished studio work - hit the market. There have been an estimated 100 of them, including The Cry of Love (1971), Rainbow Bridge (1971), War Heroes (1972) and Crash Landing (1975). The best attempt to reconstruct First Rays of the New Rising Sun, and the album Hendrix was working on at the time of his death, came decades later. Assembled from tapes, notes, interviews and song lists by Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer and Hendrix historian John McDermott, it was released on compact disc in 1997.

First Rays of the New Rising Sun appeared on MCA Records in cooperation with Experience Hendrix, the company that was formed by his father, Al Hendrix, and half-sister, Janie Hendrix, after control of his catalog was granted to them in an out-of-court settlement. The 1997 appearance of that disc coincided with remasters of the original studio albums – Are You Experiencd?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland – prepared for CD using the original two-track master tapes. There have subsequently been numerous reissues and newly issued archival works by Hendrix, including concert recordings, by Experience Hendrix.

- See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/#sthash.DYylS3x3.dpuf

Jimi

Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of

rock music. He expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar

into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive,

technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah

and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll. Hendrix

helped usher in the age of psychedelia with his 1967 debut, Are You

Experienced?, and the impact of his brief but meteoric career on popular

music continues to be felt. - See more at:

https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/#sthash.tJXroRaA.dpuf

Jimi

Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of

rock music. He expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar

into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive,

technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah

and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll. Hendrix

helped usher in the age of psychedelia with his 1967 debut, Are You

Experienced?, and the impact of his brief but meteoric career on popular

music continues to be felt.

More than any other musician, Jimi Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta blues, acid rock, R&B, soul, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob Dylan and the Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th, 1942, in Seattle. His mother was 17-year-old Lucille Jeter. His father, James “Al” Hendrix, was in the U.S. Army, stationed in Camp Rucker, Alabama, at the time of his son’s birth. Once out of the service, Al would take primary responsibility for raising him. “My dad was very strict and taught me that I must respect my elders always,” Hendrix said of his childhood. “I couldn’t speak unless I was spoken to first by grownups, so I’ve always been very quiet.” Al also formally changed his son’s name to James Marshall Hendrix at age four.

Al Hendrix father bought his son his first guitar, a secondhand acoustic that cost five dollars, when he was 16. “Jimi told me about it and I said, ‘Okay,’ and gave him the money,” Al recalled. “He strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare time he had.” A year later, he bought Jimi an electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560 S, and he joined the Rocking Kings. “My first gig with them was at a National Guard armory,” Hendrix recalled. “We earned like 35 cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the Coasters.” Hendrix, a left-hander, played a right-handed guitar without restringing it, a unique stylistic quirk.

In the summer of 1961, Hendrix enlisted in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord, California, he wrote home: “The Army’s not too bad, so far. . . . All, I mean, all my hair’s cut off and I have to shave. . . .” That fall, he was shipped Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he trained to become a paratrooper. On the side he formed a band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix’s personality made it difficult for him to adapt to the regimented life of a soldier, and in 1962 he was given an honorable discharge.

Following his abortive stint in the Army, Hendrix hit the road with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for such rhythm & blues artists as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, the Impressions, Ike and Tina Turner, and Sam Cooke. In 1965, Hendrix went to New York with Little Richard’s band and over the next several months, he’d play with a variety of musicians, including saxophonist King Curtis. He also took a job with a club band called Curtis Knight and the Squires. Recordings with that group would later be issued on Capitol Records after he achieved fame with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In 1966, Hendrix formed a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. It included 15-year-old Randy Wolfe on guitar. Renamed Randy California by Hendrix, this budding prodigy would later form the group Spirit back home in Los Angeles. Hendrix wrangled a residency lasting several months at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. In 1966, former Animals bassist Chas Chandler caught Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at Café Wha? Chandler quickly became Hendrix’s manager and convinced him to relocate to London. There, Hendrix absorbed the nascent British psychedelic movement, altered the spelling of his first name to “Jimi,” and formed a trio with two British musicians, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. The Jimi Hendrix Experience held its first rehearsal on October 6, 1966 – coincidentally, the very day that possession of LSD became illegal in the U.S. The following week, the Experience undertook a four-day French tour, supporting French pop singer Johnny Hallyday.

Hendrix was an instant sensation in Britain, where he was befriended by such admiring colleagues as Eric Clapton (then playing with Cream). The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first three singles – “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” – all made the British Top ten, with “Purple Haze” peaking at #3. Their May 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced?, became one of the defining releases of the psychedelic movement, reaching #2 in the U.K. and remaining on the British charts for eight months. Released three months later in the U.S. with a slightly amended track lineup, Are You Experienced? proved hugely influential, peaking at #5 and remaining on Billboard’s album chart for two years. The very title of the album posed a challenge – not unlike that issued on the West Coast by Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankers (“Can YOU Pass the Acid Test?) - implicitly acknowledging the notion of enlightenment through psychedelic drugs, with which Hendrix was experimenting.

After conquering Britain, Hendrix found fame in his homeland as a result of a memorable performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival – in Monterey, California – on June 18, 1967. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s virtuosity and mastery of the emerging psychedelic style, delivered with flair and theatricality by an exotically attired Hendrix, made him one of the breakout artists of the festival (along with Janis Joplin, Otis Redding and the Who). The Jimi Hendrix Experience played only eight songs at Monterey, but the force of their performance would quickly propel him to fame in this country – thanks, in large part, to his inclusion in D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop film documentary, which included Hendrix’s incendiary finale. After a highly sexualized performance of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” Hendrix set fire to his Fender Stratocaster. “It was like a sacrifice,” Hendrix later explained. “You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar. I’d just finished painting it that day and was really into it.”

Remarkably, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded its three landmark albums - Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland - in a two-year period. Wheras Are You Experienced? was an album of discreet songs, Axis: Bold As Love was constructed as an album-length experience, and it carried Hendrix’s fascination with alien intelligence and otherworldly sounds even further. Both albums were recorded in England, with Chas Chandler producing. For Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience did most of their work in New York at the Record Plant, with Hendrix largely self-producing. Engineer Eddie Kramer, however, was again involved, as he had been for the first two albums.

Electric Ladyland upped the ante yet again, being conceived as a double album with longer tracks divided between earthy blues (such as the nearly 15-minute “Voodoo Chile”) and psychedelic fantasias (such as 1983…A Merman I Should Turn to Be”). Hendrix’s rhythm & blues roots surfaced in “Crosstown Traffic,” which reached Number 52 on the pop chart. One of the highlights of Electric Ladyland was Hendrix’s electric reworking of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” (from John Wesley Harding). “Before I came to England, I was digging a lot of the things Bob Dylan was doing,” Hendrix said. “He is giving me inspiration.” Hendrix’s dynamic new arrangement brought to the fore the portents of apolcalypse in Dylan’s lyrics, and Dylan himself would ultimately perform it much like Hendrix did.

In 1968, Smash Hits, a greatest-hits compendium, was released in Britain; a year later, it appeared in America with an altered track lineup. Meanwhile, a long-simmering schism between Redding and Hendrix, further fueled by Hendrix’s desire to explore other musical areas, led to the disbanding of the Jimi Hendrix Experience after a final performance at the Denver Pop Festival in June 1969. With the Experience defunct, Hendrix debuted a short-lived experimental band called Gypsy Sun & Rainbows at the Woodstock music festival. The group included his old army buddy, Billy Cox, on bass; the Experience’s Mitch Mitchell on drums; Larry Lee on rhythm guitar; and Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez on percussion. He took the stage on 7:30 a.m. on August 18th, 1969. It was the festival’s aftermath, and Hendrix performed a heavily jammed-out set to those stragglers who hadn’t yet left the muddy, garbage-filled site. Hendrix’s freedback-drenched version of “The Star Spangled Banner” was a highlight of the two-hour Woodstock film documentary, as Hendrix evoked the pyrotechnic sounds of war in the jungles of Vietnam as he interpreted the National Anthem for a young and increasingly war-weary generation.

Hendrix’s performances at Monterey and Woodstock have become part of rock and roll legend. What is often overlooked is how hard he worked – or how hard he was worked by his management company – as a touring artist. In the spring of 1968, for instance, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed 63 shows in 66 days. Hendrix commenced work on a projected double album and performed with a new trio, Band of Gypsys – which included bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles - at the Fillmore East on New Year’s Eve 1969 and New Year’s Day 1970. The shows were recorded and culled for relase on Capitol Records as Band of Gypsys, thereby resolving an old contractual debt to the label (dating back to pre-Experience days). Band of Gypsys was the last Hendrix-approved album released in his lifetime.

Under extreme pressure from a combination of hears of nonstop work, sudden celebrity, creative demands and drug-taking, Hendrix was beginning to show signs of exhaustion by 1970. It was evident in his relatively lackluster performance at the Isle of Wight Festival that August. He performed his last concert in Germany on September 6. On September 18, he died from suffocation, having inhaled vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. He was 27 years old.

In the wake of Hendrix’s death, a flood of posthumous albums - everything from old jams from his days as an R&B journeyman to live recordings from his 1967-1970 prime to previously unreleased or unfinished studio work - hit the market. There have been an estimated 100 of them, including The Cry of Love (1971), Rainbow Bridge (1971), War Heroes (1972) and Crash Landing (1975). The best attempt to reconstruct First Rays of the New Rising Sun, and the album Hendrix was working on at the time of his death, came decades later. Assembled from tapes, notes, interviews and song lists by Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer and Hendrix historian John McDermott, it was released on compact disc in 1997.

First Rays of the New Rising Sun appeared on MCA Records in cooperation with Experience Hendrix, the company that was formed by his father, Al Hendrix, and half-sister, Janie Hendrix, after control of his catalog was granted to them in an out-of-court settlement. The 1997 appearance of that disc coincided with remasters of the original studio albums – Are You Experiencd?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland – prepared for CD using the original two-track master tapes. There have subsequently been numerous reissues and newly issued archival works by Hendrix, including concert recordings, by Experience Hendrix.

- See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/the-jimi-hendrix-experience/bio/#sthash.tJXroRaA.dpuf

More than any other musician, Jimi Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta blues, acid rock, R&B, soul, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob Dylan and the Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th, 1942, in Seattle. His mother was 17-year-old Lucille Jeter. His father, James “Al” Hendrix, was in the U.S. Army, stationed in Camp Rucker, Alabama, at the time of his son’s birth. Once out of the service, Al would take primary responsibility for raising him. “My dad was very strict and taught me that I must respect my elders always,” Hendrix said of his childhood. “I couldn’t speak unless I was spoken to first by grownups, so I’ve always been very quiet.” Al also formally changed his son’s name to James Marshall Hendrix at age four.

Al Hendrix father bought his son his first guitar, a secondhand acoustic that cost five dollars, when he was 16. “Jimi told me about it and I said, ‘Okay,’ and gave him the money,” Al recalled. “He strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare time he had.” A year later, he bought Jimi an electric guitar, a Supro Ozark 1560 S, and he joined the Rocking Kings. “My first gig with them was at a National Guard armory,” Hendrix recalled. “We earned like 35 cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the Coasters.” Hendrix, a left-hander, played a right-handed guitar without restringing it, a unique stylistic quirk.

In the summer of 1961, Hendrix enlisted in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord, California, he wrote home: “The Army’s not too bad, so far. . . . All, I mean, all my hair’s cut off and I have to shave. . . .” That fall, he was shipped Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he trained to become a paratrooper. On the side he formed a band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix’s personality made it difficult for him to adapt to the regimented life of a soldier, and in 1962 he was given an honorable discharge.

Following his abortive stint in the Army, Hendrix hit the road with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for such rhythm & blues artists as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, the Impressions, Ike and Tina Turner, and Sam Cooke. In 1965, Hendrix went to New York with Little Richard’s band and over the next several months, he’d play with a variety of musicians, including saxophonist King Curtis. He also took a job with a club band called Curtis Knight and the Squires. Recordings with that group would later be issued on Capitol Records after he achieved fame with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In 1966, Hendrix formed a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. It included 15-year-old Randy Wolfe on guitar. Renamed Randy California by Hendrix, this budding prodigy would later form the group Spirit back home in Los Angeles. Hendrix wrangled a residency lasting several months at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. In 1966, former Animals bassist Chas Chandler caught Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at Café Wha? Chandler quickly became Hendrix’s manager and convinced him to relocate to London. There, Hendrix absorbed the nascent British psychedelic movement, altered the spelling of his first name to “Jimi,” and formed a trio with two British musicians, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. The Jimi Hendrix Experience held its first rehearsal on October 6, 1966 – coincidentally, the very day that possession of LSD became illegal in the U.S. The following week, the Experience undertook a four-day French tour, supporting French pop singer Johnny Hallyday.

Hendrix was an instant sensation in Britain, where he was befriended by such admiring colleagues as Eric Clapton (then playing with Cream). The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first three singles – “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” – all made the British Top ten, with “Purple Haze” peaking at #3. Their May 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced?, became one of the defining releases of the psychedelic movement, reaching #2 in the U.K. and remaining on the British charts for eight months. Released three months later in the U.S. with a slightly amended track lineup, Are You Experienced? proved hugely influential, peaking at #5 and remaining on Billboard’s album chart for two years. The very title of the album posed a challenge – not unlike that issued on the West Coast by Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankers (“Can YOU Pass the Acid Test?) - implicitly acknowledging the notion of enlightenment through psychedelic drugs, with which Hendrix was experimenting.

After conquering Britain, Hendrix found fame in his homeland as a result of a memorable performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival – in Monterey, California – on June 18, 1967. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s virtuosity and mastery of the emerging psychedelic style, delivered with flair and theatricality by an exotically attired Hendrix, made him one of the breakout artists of the festival (along with Janis Joplin, Otis Redding and the Who). The Jimi Hendrix Experience played only eight songs at Monterey, but the force of their performance would quickly propel him to fame in this country – thanks, in large part, to his inclusion in D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop film documentary, which included Hendrix’s incendiary finale. After a highly sexualized performance of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” Hendrix set fire to his Fender Stratocaster. “It was like a sacrifice,” Hendrix later explained. “You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar. I’d just finished painting it that day and was really into it.”

Remarkably, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded its three landmark albums - Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland - in a two-year period. Wheras Are You Experienced? was an album of discreet songs, Axis: Bold As Love was constructed as an album-length experience, and it carried Hendrix’s fascination with alien intelligence and otherworldly sounds even further. Both albums were recorded in England, with Chas Chandler producing. For Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience did most of their work in New York at the Record Plant, with Hendrix largely self-producing. Engineer Eddie Kramer, however, was again involved, as he had been for the first two albums.