ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2014/11/sound-projections-online-quarterly.html

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/cecil-taylor-mn0000988386

Cecil Taylor

(1929-2018)

Biography by Scott Yanow

Soon after he first emerged in the mid-'50s, pianist Cecil Taylor was considered one of the most radical and boundary-pushing improvisers in jazz. Although in his early days he used some standards as vehicles for improvisation, Taylor is largely known for his often avant-garde original compositions. To simplify describing his style, one could say that his intense atonal percussive approach involved playing the piano as if it were a set of drums. He generally emphasized dense clusters of sound played with remarkable technique and endurance, often during marathon performances.

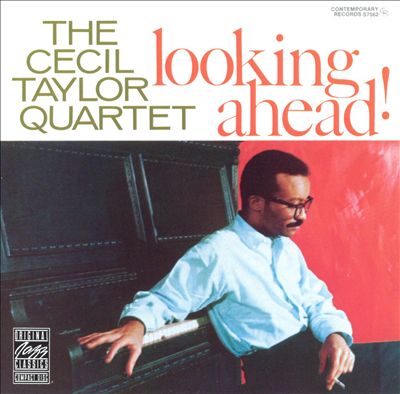

Born in 1929, and raised in Corona, Queens in New York City, Taylor started piano lessons at the age of six, and attended the New York College of Music and the New England Conservatory. His early influences included Duke Ellington and Dave Brubeck, but from the start he sounded original. Early gigs included work with groups led by Johnny Hodges and Hot Lips Page, but, after forming his quartet in the mid-'50s (which originally included Steve Lacy on soprano, bassist Buell Neidlinger, and drummer Dennis Charles), Taylor was never a sideman again. The group played at the Five Spot Cafe in 1956 for six weeks and performed at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival (which was recorded by Verve), but, despite occasional records like 1958's Looking Ahead, work was scarce.

In 1960, Taylor recorded extensively for Candid under Neidlinger's name (by then the quartet featured Archie Shepp on tenor), and the following year he sometimes substituted in the play The Connection. By 1962, Taylor's quartet featured his regular sideman Jimmy Lyons on alto and drummer Sunny Murray. He spent six months in Europe (Albert Ayler worked with Taylor's group for a time although no recordings resulted) but upon his return to the U.S., Taylor did not work again for almost a year. Even with the rise of free jazz, his music was considered too advanced. In 1964, Taylor was one of the founders of the Jazz Composer's Guild and, in 1968, he was featured on a record by the Jazz Composer's Orchestra. In the mid-'60s, Taylor recorded two very advanced sets for Blue Note, but it was generally a lean decade.

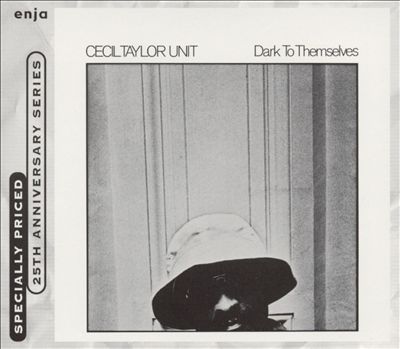

Things greatly improved starting in the '70s. Taylor taught for a time at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Antioch College, and Glassboro State College. European tours also became common. After being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973, the pianist's financial difficulties were eased a bit; he even performed at the White House (during Jimmy Carter's administration) in 1979. He also recorded more frequently, delivering albums like 1976's Dark to Themselves, and 1979's Cecil Taylor Unit. Taylor also started incorporating some of his eccentric poetry into his performances.

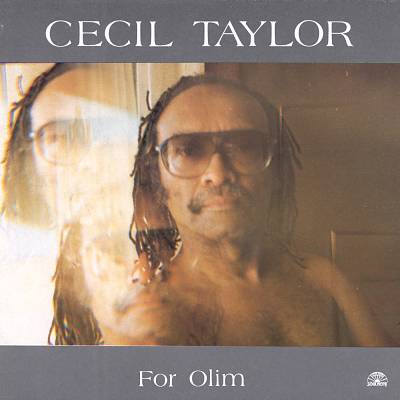

The death of longtime associate Jimmy Lyons in 1986 was a major blow, but Taylor remained active over the next few decades, issuing albums on labels such as hatART, Soul Note, Leo, and FMP, including 1986's For Olim, 1993's Always a Pleasure, and 1996's The Light of Corona. He also formed a trio with bassist William Parker and drummer Tony Oxley. During the 2000s, the pianist slowed little, often working often with his various ensembles, including his trio, and his big band. Having never compromised his musical vision, Taylor's stature grew in his later years. He was the subject of a 2006 documentary All the Notes, and in 2013 was awarded the Kyoto Prize for Music. In 2016, the Whitney Museum of American Art hosted a retrospective of his career titled Open Plan: Cecil Taylor. Taylor died on April 5, 2018 at his home in Brooklyn at the age of 89.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/cecil-taylor/

Cecil Taylor

"One of my wishes has been realized. I found love. It was difficult, but I found it. Because when Billy Holiday sang, 'You don‘t know what love is,' great singers will tell you… it‘s a partnership. It‘s a sharing." —Cecil Taylor

"Practice, to be studious at the instrument, as well as looking at a bridge, or dancing, or writing a poem, or reading, or attempting to make your home more beautiful. What goes into an improvisation is what goes into one's preparation, then allowing the prepared senses to execute at the highest level devoid of psychological or logical interference. You ask, without logic, where does the form come from? It seems something that may be forgotten is that as we begin our day and proceed through it there is a form in existence that we create out of, that the day and night itself is for. And what we choose to vary in the daily routine provides in itself the fresh building blocks to construct a living form which is easily translated into a specific act of making a musical composition." - Cecil Taylor

Cecil Taylor has been an uncompromising creative force who is a testament to his own existence and personal experience since his earliest recordings in the 1950's. In the 1960's, his music would become a leading exponent, along with that of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, of the budding "free-jazz" movement. This movement shook the very foundations on which jazz music was securely resting and marks a major turning point in the history of the music that challenged the structures of form and the tonal harmonic system. Taylor has said of his characteristic rhythmic playing that he tries "to imitate on the piano the leaps in space a dancer makes" and his orchestral facility on the piano has allowed him to innovate new musical textures in small ensemble performance. Taylor's playing has always been technically sophisticated, but as he once said, "technique is a weapon to do whatever must be done".† The personnel in his bands over his almost five decades in jazz comprises a list of astounding talent including: Steve Lacy, Jimmy Lyons, Albert Ayler, Buell Neidlinger, Dennis Charles, Archie Shepp, William Parker, Max Roach, Tony Williams, Mark Helias, Mary Lou Williams, and Bill Dixon. Additionally, he has worked with several notable dancers and choreographers including composing music for Diane McIntyre, Mikhail Barishnokov, and Heather Watts.

While his music has always been controversial to mainstream audiences, he has always been totally true to his artistic vision, and this has extended into all aspects of his life including his passions for reading, dance, theatre, and architecture. He is also an accomplished poet, and has incorporated this talent into many of his performances and recordings.

Born in New York on March 25, 1929, Cecil Taylor began playing piano and at the age of five at the encouragement of his mother. From 1951-1955 he attended the New England Conservatory where he concentrated in piano and music theory. His early professional career began working with Hot Lips Page and Johnny Hodges (c. 1953). In 1955 he formed a quartet with Steve Lacy and soon released his first important album, Jazz Avance (1956). An engagement shortly after at the Five Spot helped to establish the Greenwich Village club as a forum for East Coast new jazz. During this period he also made an appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival and the Great South Bay Jazz Festival. In 1960 his "free-jazz" quartet controversially temporarily replaced a "hard-bop" band in the play The Connection.

In 1962 he was awarded Downbeat's "new star" award for pianists while ironically unable to get work for most of the 60's. He claims he was forced to live on welfare for at least five years during this period. In 1964 he took part in the October Revolution in Jazz, a series of New York City Concerts self-sponsored by Bill Dixon's Jazz Composers Guild (consisting mostly of musicians of the avant-garde variety). In the 70's, he briefly taught at Antioch College, the University of Wisconsin, and Glassboro State College in New Jersey.

Virtually all of Taylor's recorded music between 1967 and 1977 was recorded and released in Europe. After 1973, his career began to gain momentum and he began to tour regularly as a solo pianist and leading his own groups. He was also awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and ran his own record label named Unit Core. In 1975 he was elected into the Down Beat Hall of Fame. In 1979 he composed music for the play "Tetra Stomp: Eatn' Rain in Space".

In the late 70's and early 80's Taylor began to collaborate with Diane McIntyre and her dance company Sound In Motion. This company focused on combining jazz and spoken poetry into dance. In 1988 he was honored with a month-long festival of his music in Berlin, involving many of Europe's prominent avant-garde jazz musicians. In 1990 he was named a NEA Jazz Master and in 1991 he was awarded a McArthur Foundation "genius" grant-in-aid, which provided him with considerable financial security. He was not invited to play at Jazz at Lincoln Center because of certain accusations that his music did not fit into the artistic directors' definition of "jazz", so he rented Alice Tully Hall and gave an unaccompanied piano concert, which won him a considerable amount of critical acclaim. In October of that year he gave a concert with orchestral accompaniment in San Francisco and in 1999 he appeared at a Library of Congress concert in Washington, D.C.

Taylor, now in his almost 82nd year, continues to compose music and poetry. At a time in his career when most artists of his stature could sustain themselves with a victory lap of regurgitating the past or to slip into silent retirement, Taylor continues to push new boundaries with his art. Taylor is unquestionably an artist of the highest rank, and a direct link to America's art music. His very personal and distinct artistic vision has taken him through much innovative and unexplored musical territory, demanding much of his listeners but also providing content that can be enjoyed. The musical world is awaiting the next step of Cecil Taylor.

Awards

MacArthur Foundation Genious Fellowship in 1991, Doctor Honoris Causa Columbia University, Doctor Honoris Causa New England Conservatory

“Musical categories don’t mean anything unless we talk about the actual specific acts that people go through to make music, how one speaks, dances, dresses, moves, thinks, makes love...all these things. We begin with a sound and then say, what is the function of that sound, what is determining the procedures of that sound? Then we can talk about how it motivates or regenerates itself, and that’s where we have tradition.” --Cecil Taylor, 1966

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/cecil-taylor-and-the-art-of-noise

The New Yorker

In 1993, I briefly met the composer György Ligeti, one of the towering musical figures of the past hundred years. As often happens when one is in the company of greats, I seized the opportunity to ask an idiotic question: “What do you think of Cecil Taylor?” Ligeti possessed a comprehensive knowledge of the world’s musical traditions, including jazz. But he had little more than a vaguely positive impression of Taylor. I failed to hit whatever interpretive jackpot I had been expecting.

Ligeti died in 2006, at the age of eighty-three. Taylor died last week, at eighty-nine. In truth, the two had little in common, other than a propensity for seething, maximalist textures. What united them in my mind was how they guided me as brilliant beacons at a time when I was discovering the full extent of twentieth-century musical possibility. We tend to think of genres as distinct land masses, with oceans of taste separating them. Yet, as I observed when I wrote about Taylor and Sonic Youth, in 1998, there exist polar regions where the distinctions tend to blur—namely, the zone that is often labelled “avant” or “experimental” in used-record stores. When dissonance and complexity build to a sufficient degree, works of classical, jazz, or rock descent can sound more like one another than like their parent genres.

I grew up with classical music and came late to rock, pop, and jazz. I took the northern passage between genres, and Taylor was, somewhat perversely, the first jazz figure who caught my ear—perversely because he had only one foot in jazz, as conventionally defined. The pianist and composer Ethan Iverson, commenting on a 1973 trio recording, writes that Jimmy Lyons and Andrew Cyrille, Taylor’s partners on this occasion, “sound like jazz musicians.” Taylor, however, “didn’t sound like that. He had another kind of poetry, some other kind of sheer strength of will.” The New Yorker’s Richard Brody observes that, even on the début album “Jazz Advance,” from 1956, Taylor had “left chordal jazz behind and spun musical material of his own choosing (whether harmonic, motivic, melodic, or rhythmic) into kaleidoscopic cascades of sound.” The question of whether Taylor was “really jazz” was once a hot topic in the jazz world, and he elicited a few sharp putdowns from fellow-musicians. “Total self-indulgent bullshit” was Branford Marsalis’s notorious judgment on Taylor’s modernist philosophy in the Ken Burns documentary “Jazz.” Miles Davis said, of a Taylor record, “Take it off! That’s some sad shit, man.” Such is the fate of the outsider in any genre.

For me, Taylor was the untouchable emperor of the art of noise. I first saw him in 1989, at the Western Front, a club in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Also on the bill was the David Gilmore Trio; Marvin Gilmore, Jr., David Gilmore’s father, owned the club, which was best known for its reggae nights. Several shaggy-haired patrons audibly expressed their bewilderment as the performance unfolded; it turned out that they had come expecting to hear David Gilmour, of Pink Floyd. I don’t remember much in detail about Taylor’s set, in which he was joined by William Parker, on bass, and Gregg Bendian, on drums. I do recall that for the first five or ten minutes the music was dense, intense, driving, ferocious—and then it started. Some frenzy of figuration under Taylor’s hummingbird hands set off a collective pandemonium that became purely physical in effect: I felt at once pressed backward and pulled in. It remains one of the most visceral listening experiences of my life.

Taylor always shunned labels. He often used “jazz” in virtual quotation marks, even though he recognized it as his home tradition. He was also wary of the word “composer.” A graduate of the New England Conservatory, he was rigorously trained in classical composition and performance, and could fire off precise references to Webern, Xenakis, and, yes, Ligeti. But he disliked the idea of the composer as a mastermind controlling every aspect of music behind the scenes. In 1989, Steve Lake wrote, of Taylor: “In a dismissive tone, he can make ‘composer’ sound like ‘dictator’ or ‘megalomaniac.’ ‘I don’t think I’d ever want to be considered a composer’ (accompanying the word with an expression of acute distaste).” In this Taylor was akin to his idol, Duke Ellington, who resisted European archetypes of composition and sought to create his own jazz-based African-American version of it. Ellington and Taylor were vastly different: the one suave, aristocratic, buoyant, popular; the other irregular, anarchic, confrontational, anti-commercial. But Taylor emulated Ellington’s way of composing with and through his groups. Taylor would give his collaborators notated material, yet they had the freedom to express themselves through the written notes or abandon them altogether.

Taylor could indeed create atonal music on the fly, as if he were improvising a Charles Ives sonata or a Stockhausen Klavierstück. At his most diabolical, he sounds like several of Conlon Nancarrow’s hyperkinetic player-piano rolls playing simultaneously. Those splatters of notes are hardly random, however. He pummels the piano in different registers and then repeats the gesture with startling precision. His hands always go where his brain directs them to go. And he would return to tonal groundings after long spells in a gravity-free environment. Something I particularly loved about his recordings and performances—I saw him a handful of times in the nineties and the aughts—were the grand, mournful, minor-mode themes that would periodically loom out of the harmonic fog. They struck me as fundamentally Romantic in contour—perhaps a bit Brahmsian, for lack of a better point of reference. I have stitched together a few of them, from “3 Phasis,” “Winged Serpent,” and “Alms / Tiergarten (Spree),” which you can listen to here.

The last example comes from a set of eleven CDs released by the Free Music Production label, documenting Taylor’s residency in Berlin in the summer of 1988. “Alms,” a two-hour marathon featuring a seventeen-piece group called the Cecil Taylor European Orchestra, included such avant-jazz luminaries as Evan Parker, Peter Brötzmann, Peter Kowald, and Han Bennink. The music moves in like a weather system, a slow-gathering, all-engulfing storm of sound. On the FMP recording, the orchestra is plainly working from a score and periodically settles on a particular figure, though crisp unisons are not the point. (Taylor himself often ignores the big patterns he has set in motion and dances deliriously against the grain.) I witnessed the same mighty convergence at a live show at Iridium, in 2005, with a fifteen-piece band. As the music swayed between quasi-symphonic utterances and every-which-way melees, it presented a totality, a sprawling structure built in real time.

As Iverson says, no one else played like Taylor, and no one will. Nonetheless, he leaves a potent legacy for the ever-growing body of music that unfolds in the spaces between jazz and classical traditions, between European and African-American cultures, between composition and improvisation. With Taylor, the refusal of category, the resistance to description, was rooted in an attitude of defiance that seemed variously personal, cultural, and political. At a famously contentious discussion at Bennington College in 1964, Taylor said: “The jazz musician has taken Western music and made of it what he wanted to make of it.” As a queer black man—he rejected the label “gay”—he experienced racism in the wider world and homophobia within jazz. As the purveyor of music that most people found incomprehensible, he encountered a disdain that frequently boiled over into irrational hatred. His imperious indifference followed the example of the European masters who looked nothing like him, and whose company he joins.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Alex Ross has been the magazine’s music critic since 1996. His latest book is “Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music.”

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/postscript/the-revolutionary-genius-of-cecil-taylor

One warm summer evening in the mid-nineteen-eighties, the pianist Cecil Taylor was scheduled to give a solo performance at a concert hall on the Lower East Side, all tickets sold at the door. Expecting a clamoring crowd, I got there an hour early; I was the first person to arrive. When the doors opened, there were only a handful of enthusiasts. We trickled into the hall, a converted school auditorium that could easily have seated two hundred. There was a piano onstage; at the scheduled time, some monosyllabic incantations could be heard from the wings, some shuffling of feet. The pianist poked himself out onto the hardwood stage, doing a sort of halting, tentative chant and dance, approaching the piano mysteriously, a Martian pondering a monolith. He tapped and rapped and knocked the instrument’s solid wooden body; he probed it from all angles; then he found the keyboard, struck a note, and then another, and another; his theatrical probing gave way to radiant musical illumination.

Taylor had to have noticed, as he circumnavigated the instrument, the sparse audience; he pretended that it didn’t matter. For the twenty lovers in attendance, Taylor approached the piano bench, sat down, struck a chord, crystallized a motif, and worked it out in thunder. For an hour, all by himself onstage and nearly by himself in the hall, he performed a colossal, exhausting, self-sacrificing concert of pianistic fury, filling the room with a torrential, polyrhythmic, rumbling, crashing, shattering whirlwind. It resembled the music that I had loved on records since I was a teen-ager a decade earlier, but now erupted, in my presence, with an improvisational explosion and a spontaneous compositional complexity that put it both at the forefront of modern jazz, of modern music as such. It was the mightiest and most generous musical exertion I had seen. To this day, I’ve only seen Taylor himself surpass it.

Cecil Taylor died on Thursday, at the age of eighty-nine. Of all the jazz musicians who wrought definitive, revolutionary changes in music in the late nineteen-fifties and early nineteen-sixties, Taylor’s advances went further than anyone else’s to expand the very notion of musical form. His ideas built on the emotional and intellectual framework of modern jazz in order to extend them into seemingly new dimensions—ones that have remained utterly unassimilable by the mainstream and are still in the vanguard, rushing headlong into the future.

by Ben Ratliff

June 21, 2013

New York Times

The improvising pianist Cecil Taylor, a pioneering, influential and highly experimental musician and a longtime Brooklyn resident, is one of this year’s recipients of the Kyoto Prize, awarded each year by the Inamori Foundation in Japan, the foundation announced on Friday. Mr. Taylor, 84, is this year’s laureate in the category of arts and philosophy; different fields across technology, science, art and philosophy are considered on a rotating basis, and there has been a recipient in music every four years. (The last musician laureate in 2009 was the conductor and composer Pierre Boulez.) The prize comes with a cash gift of 50 million yen (approximately $510,000), to be given at a ceremony in Kyoto in November. This year’s other laureates are the electronics engineer Dr. Robert H. Dennard and the evolutionary biologist Dr. Masatoshi Nei.

Kyoto prize to pianist/improviser Cecil Taylor

Taylor has previously been honored with Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellowships, and named an NEA Jazz Master among other awards and prizes. I posted a lengthy appreciation of him on the occasion of his 84th birthday. My personal favorites among Taylor’s approximately 70 recordings include the solos Fly! Fly! Fly! Fly! Fly! and Air Above Mountains, and his ensemble masterpieces Unit Structures and Conquistador.

The Kyoto Prize was established by Kazuo Inamori in 1984; Dr. Inamori is also the founder of the Kyocera Corporation, an international firm dealing in a wide range of products including electronic components and consumer cellular phones and cameras. It is one of the highest honors conferred in Japan. Taylor, a longtime resident of Brooklyn, will be awarded his diploma, 20K gold Kyoto Prize medal and prize money of 50 million yen (approx US$500,000) in Kyoto, November 2013. His next scheduled concert is a solo performance at the Willisau (Switzerland) Jazz Festival, on September 1.

howardmandel.com

necmusic.edu/cecil-taylor-awarded-kyoto-prizeCecil Taylor Awarded Kyoto Prize

July 25, 2013

New England Conservatory Alumnus Cecil Taylor

Awarded 2013 Kyoto Prize

The prize is an international award presented in three categories to those who have contributed significantly to the progress of science, the advancement of civilization, and the enrichment and elevation of the human spirit.

The Kyoto Prize Presentation Ceremony will be held in Kyoto, Japan, on November 10, 2013. Each laureate will be presented with a diploma, a Kyoto Prize Medal (20K gold), and prize money of 50 million yen (approximately $500,000).

As the Kyoto Foundation notes on their website, Taylor is “an innovative jazz musician who has fully explored the possibilities of piano improvisation. One of the most original pianists in the history of free jazz, Mr. Cecil Taylor has developed his innovative improvisation departing from conventional idioms through distinctive musical constructions and percussive renditions, thereby opening new possibilities in jazz. His unsurpassed virtuosity and strong will inject an intense, vital force into his music, which has exerted a profound influence on a broad range of musical genres.”

Ken Schaphorst, Chair of the Jazz Studies program at New England Conservatory, notes: "NEC has had many notable alums. But Cecil Taylor is in a class by himself. Very few musicians have influenced the course of jazz history more than Cecil. And no one has been more uncompromising in the pursuit of artistic honesty and truth."

A key figure in the birth of free jazz in the late 1950s and a revered improviser and composer who helped redefine the stylistic language of the piano, Cecil Taylor remains at the forefront of contemporary avant-garde jazz.

Born in New York City in 1929, Taylor visited relatives in Boston following World War II, which led to his enrolling at NEC. Taylor completed NEC's diploma in Arranging in 1951, attributing his education not only to his NEC studies in piano, arranging, harmony, and advanced solfege but to experiences "outside of the school or from the nonacademic aspect of school," including a friendship with saxophonist Andy McGhee that opened many doors in Boston's jazz community.

After short sideman stints with Johnny Hodges and Hot Lips Page, Taylor formed the first of his own ensembles, which, over the course of the next decade, included such significant improvisers as saxophonists Steve Lacy, Archie Shepp, Jimmy Lyons and Sam Rivers, and the drummers Sonny Murray and Andrew Cyrille.

By the time of his earliest recordings in the late 1950s, Taylor’s revolutionary style was already in place: his virtuosic technique coupled with his startling use of tonal clusters, polyrhythms, applied dissonance, and open collective ensemble improvisation was as vitally important to the growth of free jazz as the work of his contemporaries Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane. His seminal albums of the ’50s and ’60s—including Looking Ahead, Unit Structures, and Conquistador!—were signposts for a new musical era.

Over the succeeding decades, Taylor’s astonishing work as a solo pianist—as heard on such landmark recordings as Spring of Two Js—as well as his collaborations with ensembles ranging from duos to large jazz orchestras, brought him international acclaim. Acknowledged as a master musician by jazz, new music, and classical circles, Taylor has influenced countless artists from Anthony Braxton to Sonic Youth. At 84 years old, he remains as daring as ever, an inspiration for adventurous players of all musical stripes.

Photo by Tom Fitzsimmons shows Cecil Taylor's solo improvisation during 2003 celebration of the centennial of NEC's Jordan Hall.

Find more on jazz studies at NEC here.

ABOUT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY JAZZ STUDIES

NEC’s Jazz Studies department was the first fully accredited jazz studies program at a music conservatory. The brainchild of Gunther Schuller, who moved quickly to incorporate jazz into the curriculum when he became President of the Conservatory in 1967, the Jazz Studies faculty has included six MacArthur "genius" grant recipients (three currently teaching) and four NEA Jazz Masters, and alumni that reads like a who’s who of jazz. Now in its 44th year, the program has spawned numerous Grammy-winning composers and performers. As Mike West writes in JazzTimes: “NEC’s jazz studies department is among the most acclaimed and successful in the world; so says the roster of visionary artists that have comprised both its faculty and alumni.” The program currently has 114 students; 67 undergraduate and 47 graduate students from 12 countries.

Contact: Ann Braithwaite

Braithwaite & Katz

781-259-9600

ann@bkmusicpr.com

Message from Mr. Cecil Taylor on the 2013 Kyoto Prize:

The 2013 Kyoto Prize Commemorative Performance in Arts and Philosophy"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CihuLOouH8w

The 2013 Kyoto Prize Presentation Ceremony:

Published on December 10, 2013:

Each laureate received Diploma, Kyoto Prize medal and 50 million yen as prize money from Hiroo Imura, Chairman of the Inamori Foundation in the presence of Her Imperial Highness Princess Takamado and other audience (about 1,550) from political, business and the academic worlds. If you are interested in the Kyoto Prize and Inamori Foundation, please access to "http://www.inamori-f.or.jp”.

http://burningambulance.com/2013/07/04/cecil-taylor-in-paris/

Cecil Taylor In Paris

Written by burning ambulance

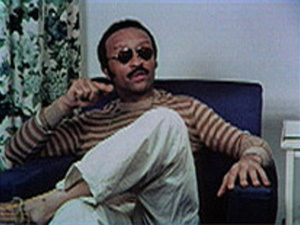

Here’s an amazing 45-minute film, Cecil Taylor à Paris – Les Grandes Répétitions 1968. It features performance footage of Taylor, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, bassist Alan Silva, and drummer Andrew Cyrille, as well as clips of Taylor being interviewed. It’s amazing stuff, especially the performance footage, which isn’t from some nightclub or even a theater—the band is located in a beautiful old Paris apartment. At one point, Lyons is standing facing the empty fireplace, blowing into it. Watch!

All,

HAPPY BIRTHDAY CECIL!

Kofi

Cecil Taylor: The Piano As Orchestra

by Kofi Natambu

“The whole question of freedom (in music) has been misunderstood, by those on the outside and even by some of the musicians in ‘the movement.’ If a man plays for a certain amount of time...eventually a kind of order asserts itself...There is no music without order--if that music comes from a man’s innards. But that order is not necessarily related to any single criterion of what order should be as imposed from the outside. This is not a question then of ‘freedom’ as opposed to ‘nonfreedom’ but rather it is a question of recognizing different ideas and expressions of order.”

Don’t look away or even blink. See the sweating boxer’s arms connected to elegant steel fingers raised in cat’s paw claw action now racing in a whiteheat blur across the tonal spectrum of 96 keys glittering? See his painter’s hands grip, jab, caress, stroke and maul the digital slabs of shining white and black ivory? As he dives into the thunder range of the now liquid instrument you glimpse his leaping fingers dancing in quick rhythmic steps across the linear tracks of the piano. The crystalline shower of notes are ringing in spiralling waves of overtones that seem to swallow up the air. Lost in a tornado of lyricism and a pulsating hurricane of instrumental virtuosity, you detect within the maelstrom a beautiful haunting song long since forgotten. It is then you discover that you have not been asleep after all. It is a waking dream and its name is Cecil Taylor.

CECIL TAYLOR. The very name has come to represent all that is truly creative, vital and innovative in contemporary 20th century American music. In an amazing career that spans some thirty years he has earned the right to be called that which is reserved for only those rarest of individuals: GENIUS. Another member of this esteemed pantheon, Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington, called these same men and women “beyond category.” Their greatness is not dependent upon the ever changing blandishments of stylistic trends. All forms are subordinate to their compelling vision and spiritual force. It is to this magnificent realm that Cecil Taylor belongs.

Possessing tremendous energy and range, and an astounding technical facility on piano, Taylor is widely considered one of the greatest virtuosos in the world on his instrument. However, this is only a small part of what he does. A former drummer in his youth and a serious student of percussion, Cecil’s concept of the piano (derived from the African folk tradition) reminds everyone that it is technically considered a percussive instrument. In fact his explosive, riveting touch on piano led the Jazz writer Valerie Wilmer to refer to his keyboard as “eighty-eight tuned drums.” Cecil is a world-class composer whose improvisational skills are unlimited. There is no one who plays as fast, with as much power or as intensely as Cecil Taylor, yet there is a precision and structural control that is also unequalled. Cecil has the kind of stamina that allows him to play for hours(!) at a time. Many times the tempos are set at a demonic speed, yet he will just as often overwhelm the listener with a soft, aching tenderness and translucent ballad style. In order to enter the singular world of Cecil Taylor one must simply be prepared to open up completely and put aside all conventional notions and expectations about music. Since Taylor is always involved in a vigorous redefinition of what is called melody, harmony, and rhythm, there are rarely any stylistic cliches in his playing.

Taylor’s music is characterized by the creative use of sound as color and texture expressed in overlapping and pyramidal layers of melodic lines, riffs, motifs, tonal clusters, and polyrhythms. Timbral dynamics and constrast, as well as a highly sophisticated use of blues-based call-and-response voicings are also integral aspects of Taylor’s orchestral approach to the piano. In ensemble settings Taylor is deeply indebted to the master Duke Ellington for basic organizational principles. Of this influence, Taylor states” “One thing I learned from Ellington is that you can make the group you play with sing if you realize each of the instruments has a distinctive personality; and you can bring out the singing aspect of that personality if you use the right timbre for the instrument.” This lesson is applied in a particularly striking manner by Taylor and his saxophonist of twenty-three years, the outstanding altoist Jimmy Lyons.

Born in Long Island City, New York on March 15, 1929, Taylor began playing at age five encouraged by his music loving parents who early on exposed young Cecil to pople like Duke Ellington. His mother was a dancer who could play the piano and violin. His father, a butler and chef by trade, sang blues, field hollers, and shouts in the home, and was also somewhat of an oral scholar in black folklore. Aside from being exposed to a very wide range of black music, Taylor was also learning about the European classical tradition.

It was because of the example of Ellington that Taylor, after high school studies at the New York College of Music, decided to go to Boston and attend the New England Conservatory of Music in 1951. Because of Ellington’s obvious mastery of large scale orchestral forms, and a casual, ironic remark by Duke that “You need everything you can get--you need the conservatory with an ear to what’s happening in the street”, Taylor decided that no music should be beyond his understanding, or more importantly, absorbed in a creative, dynamic way in the development of his own unique vision of the African American improvisational tradition. as Cecil so eloquently points out: “Musical categories don’t mean anything unless we talk about the actual specific acts that people go through to make music, how one speaks, dances, dresses, moves, thinks, makes love...all these things. We begin with a sound and then say, what is the function of that sound, what is determining the procedures of that sound? Then we can talk about how it motivates or regenerates itself, and that’s where we have tradition.”

Ironically, it was while Cecil studied at the conservatory that he discovered in just what specific ways he could find a functional use for his experience as an African American artist in a hostile and overtly racist environment. While attending this academy Cecil realized that he could learn much more about the creative aspects of music from working musicians in the black music tradition than he ever could from the elitist teachers in the conservatory. As Taylor pointed out: “I learned more music from Ellington than I ever learned from the New England Conservatory. Like learning an orchestral approach to the piano from Ellington, like, I could never have gotten that from the conservatory.”

It was during his stay in Boston in the early 1950s that Cecil heard many of his idols in live performance for the first time. It was in Boston in 1952 that Taylor first heard the legendary Charles ‘Bird’ Parker at the local Hi-Hat club. Cecil also heard the great pianist-composer Bud Powell at this time, as well as the outstanding pianist/composer/arranger Mary Lou Williams. By this time Taylor had already plunged into an extended and intensive study of many of his major influences, such giants of 20th century piano music as Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, Count Basie, Horace Silver, Thelonious Monk, and of course, Duke Ellington. However, Cecil’s deep and on-going appreciation of these artists did not keep him from also checking out people like Miles Davis, Lennie Tristano, James Brown, Igor Stranvisky, Aretha Franklin, Anton Webern, Marvin Gaye, and Bela Bartok (who Taylor said, “Showed me what you can do with folk material”). It’s important to note that Taylor not only considers these individuals to be seminal sources of inspiration in his music, but that his attitude toward this myriad of influences is not that of the blind, indiscriminate eclectic. Taylor has a very sharp and critical understanding of the relative value of the artists (and art forms) that he chooses to draw from.

Upon graduation from the conservatory in 1955, Taylor immediately made his considerable presence known with an outstanding group that recorded in December of that year when Cecil was twenty-six. It was Cecil’s first recording (Jazz Advance for the Boston-based Transition label). Many people consider this to be the first so-called” Jazz “avant-garde” recording of the modern era. This recording is now a cherished collector’s item.

As a fiercely independent and iconoclastic black artist, Taylor has had to pay the severe price of uncomprehending and often ignorant music critics judging his music using alien criteria. This kind of reception to his music by agents, promoters, clubowners, and recording executives who cannot neatly package Taylor’s sound for mass commodity sale has caused Cecil’s public career to be interrupted for long periods of time. For example, the general hostility of the music industry in the U.S. kept Taylor from being recorded in America from 1963-1966 and again from 1969-1973. There were also infrequent opportunities to work in clubs or on concert stages during the sixties and early 1970s. Consequently, Taylor has only appeared on 23 records as a leader, and just two other recordings as a featured artist, in thirty years.

However it a great testament to Taylor’s integrity and inspiring dedication and perseverance that he has not only survived this criminal neglect but has partly compensated for it by performing and recording widely in Europe and Japan (since 1967, ten of his last fifteen recordings released in this country have been for his own, or foreign-owned labels). He has also taught at the University of Wisconsin, (where he taught the largest class in the history of the school--over 1,000 students--and then proceeded to flunk over 70% of them in 1970!), Antioch College and Glassboro State College.

Cecil’s career, like that of so many great artists, is full of strange ironies and paradoxes. Despite leading recording sessions with many of the finest musicians in the world over the past twenty-five years (e.g. John Coltrane, Sam Rivers, Bill Dixon, Steve Lacy, Albert Ayler, Andrew Cyrille, Jimmy Lyons, Tony Williams, and just recently Max Roach); despite winning a Guggenheim Fellowship in Music (1973); despite playing a masterful performance at the White House in June, 1978 (that literally made then President Jimmy Carter leap up and embrace Taylor), and despite winning countless awards and kudos from all over the globe (and being written about by more poets than any artist in “Jazz” today), Cecil Taylor is still virtually unknown in the United States, even among the artistic cognoscenti.

Obviously, this shouldn’t be. For there is nothing self-consciously precious or ‘academic’ about Cecil’s playing. Steeped in the rich blues tradition (expressed in an abstract expressionist style) the music is very physical: passionate, sensuous, rigorous, and athletic. The pervasive influence of Dance is forever present in Cecil’s work. In fact, Taylor, who has often collaborated in live performances with dancers, playwrights and poets like Mikhail Baryshnikov, Diane McIntyre, Adrienne Kennedy, and Thulani Davis, has often said that he likes to “try to imitate on piano the leaps in space a dancer makes.” His music has a dancer’s grace and fluidity.

Taylor, who repudiates the traditional Western idea that form is more important than, or separate from, content in art has said that he is a constructivist (which he explains as “one who is involved in the conscious working out of given materials”). In Taylor’s music the emphasis is on building a whole, totally integrated structure through the application of the principle of kinetic improvisation.

Cecil is always quick to point out that the real basis of the music is emotional and spiritual. He has stated that “to feel is the most terrifying thing one can do in this society” and that “The thing that makes Jazz so interesting is that each man is his own academy...If he’s going to be persuasive he learns about other academies, but the idea is that he must have that special thing. And sometimes you don’t even know what it is.” Finally he states: “Most people have no idea what improvisation is...It means the most heightened perception of one’s self, but one’s self in relation to other forms of life. It means experiencing oneself as another kind of living organism much in the same way as a plant, a tree--the growth, you see, that’s what it is...I’m hopefully accurate in saying that’s what happens when we play. It’s not to do with ‘energy.’ It has to do with religious forces...it is the ability to talk coherently through the symbols.” Today Cecil is at the pinnacle of his artistic powers. Justly lionized in Europe and Japan, and a “living legend” among musicians in the U.S., Cecil commands SRO audiences wherever he performs. For the first time in his career he can afford to pay his rent and live decently on the income he earns from playing. We are the fortunate ones, for despite the on-going attempts of ‘official culture’ to deny the very existence of the contemporary black creative artist (especially as innovator and ‘cultural leader’), people like Taylor continue to provide leadership. At 57 Cecil is one of the major artists in this country. He has changed the very form and content of American music in his lifetime. For this, we owe him and his peers in African American creative music an enormous debt.

The Cecil Taylor Trio: Live at Sweet Basil’s

by Kofi Natambu

The City Sun

Brooklyn, NY

In one of his all-too-rare New York appearances, the legendary Cecil Taylor proved once again why he is one of the most important figures in the Afro-American improvisational music tradition.

In last week’s exhilarating performance at Sweet Basil that left this reviewer and a packed house of very attentive music lovers in awe, Taylor led a stunning trio ensemble. The set projected the sonic range, power and instrumental virtuosity of a large orchestra without ever once sounding bombastic, pretentious or cloying.

With a compositional precision and telepathic interplay that suggested inspired alchemy as much as great technical proficiency, Taylor and cohorts gracefully segued from one melodic/rhythmic tonal episode to the next. In an endless multilayered suite of haunting thematic motifs, riffs, sound clusters and harmonic intervals, the ensemble presented a mesmerizing ritual of interlocking rhythms and mercurial chordal movements, full of detail and passionately played. Crashing waves of sound from Taylor’s piano were deftly complemented by the masterful rippling strokes of Tony Oxley, a drummer and percussionist from Sheffield, England, Oxley’s architectonic pyramids of rhythms served as a perfect foil for Taylor’s in tense jabbing, slashing and conga-beat stylistics on piano. The sonorous orchestral tapestry was held together by the insistent buzzing big beat of the extraordinary bassist, William Parker.

Taylor, who is justly famous for possessing one of the most explosive piano techniques in the world, is much more than a mere virtuoso. He is also one of the finest organizers of sound in the world today. This profound ability was demonstrated throughout the set where he played continuously at demonic, white-heat tempos that spread out into achingly romantic arpeggios of love-talk, but without dumb sentiment gumming up the works. From there Taylor slipped rapidly into blistering multi-noted runs, leaping into liquid fire displays of lovely melodic shapes that conjured elegant images of Ellington and a richly abstract Tadd Dameron.

As Taylor tore off huge shards of melody, implying a broad canvas of harmonic colors with his delicate filigreed piano musings, Oxley pounded heavy bass drums and rode a gigantic cymbal hovering just above Taylor’s head. Parker, meanwhile, dived and swayed on his bass, as if rocking to a cosmic metronome that only he could hear.

Suddenly a torrent of notes flew from Taylor’s keyboard, cascading quickly onto a typhoon of crackling snares, rumbling bass ostinatos. A rainbow tide of tonal colors filled the air. This was the noble, magisterial Taylor using disciplined fury to display his virtuosic range. Taylor could be heard rising out of the collective storm playing a moaning blues. Stabbing, inquisitorial notes were punctuated by ominous silences. Then, just as mysteriously and defiantly as the set began, it ended with a shattering, yet, open-ended chord. Then a resounding silence. Taylor shot up from the piano bench and strolled into the back of this club. As he disappeared like a ghost, I remembered his famous quote: “to feel is the most terrifying thing one can do in this country.” Tell the truth, C.T. I just hope we’re listening...

http://www.furious.com/PERFECT/ceciltaylor.html

CECIL TAYLOR

Interview by Jason Gross

January 2001

Q: This has been sort of an interesting year for you in that you've had the chance to reconnect with several of the key drummers you've worked with over the years: you performed duets with Max Roach at Columbia University, with Elvin Jones for an album last year and a couple of performances subsequently, then with Andrew Cyrille, and just now with Tony Oxley over in Den Haag.

Well, when I think about it in retrospect, that's never happened to me before in that there were four different drummers in that period of time... All of them quite different, too, all of them a part of history. Andrew's magnificent. He's a wonderful person and a good part of my musical life. Andrew, who is really part of my skin you might say, is a great accompanist, a superlative percussionist, and one of the most amenable personalities. Playing with Mr. Jones for the fourth time was a great musical experience As you know, in September he played mostly with mallets and brushes. When I played with him the most unifying musical characteristic was that we played as if we were one person. He understands the music that I construct, all the dynamics, the aspects of form. And then the last time, even more so. Then Mr. Roach, well it was quite a phenomenal situation playing with him at Columbia in front of ten thousand people, and then Tony Oxley, he is a joy just to be with. He is immense in what he does, his conception of sound. Then again, I'm leaving out the guitarist, Derek Bailey, who was sort of astounding [during his springtime collaboration with Taylor] at Tonic. He was, well, hysteric. I don't think there's anyone else quite like Derek. So I've been very fortunate.

You know, I played in Johnny Hodges' band for about a week in 1955, in Chester, PA. That experience was so wonderful, such a pleasure I didn't even touch the piano for the first four days, until the wonderful [Ellington band trombonist] Lawrence Brown said, "er, Cecil, the piano has 88 keys, it'd be nice if you'd play one note occasionally." (laughs) Then of course, Basie's band was lighter, and their conception of that single stem or motif, which the word "riff" doesn't describe the organic nature of how that band created it's magic.

And Miles, he was the mean devil incarnate! But such a mind, such a mind. And such creative growth, from those days of genuflection to Diz and Bird. And that remarkable record that the master Bird made, it was merely the ground theme of "Embracable You", and Bird took this extraordinary solo, and then you heard Miles come and pause and make sound then, we knew that was the beginning of another voice. And soon after that, Birth of the Cool with the great master Gil Evans, and we heard the fluidity and love of Mr. Davis...Davis was one of the greatest organizers of musical sound this country has ever known.

When you think of virtuosity, how can one not talk about the extraordinary Albert Ayler and what he laid down? Technically, I don't think I've heard a saxophonist with that kind of articulation. And Eric Dolphy, he was a very considerate man, a very warm man... You know, the last two performances he did in America, I was fortunate enough to be there and I said to him, "Eric, you're the first level of greatness." Some die too soon. Albert died too soon. When you think about the implications of that band, with Albert's brother who compressed that trumpet sound, and the brilliance of that sound. There's one trumpet player alive today who comes closest to that sound, and that's [former Taylor Unit trumpeter] Raphe Malik.

What I'm saying is that we have such a rich tradition, until we get to a man like Bill Dixon, who is undoubtedly one of the great voices in American music today. I had the great pleasure of hearing he and Tony Oxley and two bassists playing in Berlin last November, absolutely extraordinary. Beyond the ken of what's thought to be important here. But, one has to allow for the decadence of merchandising...

I mean, it's such a history of accomplishment, that has gone down in America. The music has its roots in America, in the soil of America... The traditional legacy of the music which went on in Africa, that exists here by Native Americans... And when I talk about soil, grandfather on father's side was Kiowa, coming from the same region as Mingus' wonderful drummer Dannie (Richmond). And mother's mother, growing up in Long Branch think about that, that's a Native American name she was full blooded Cherokee. So having the last name Taylor, yep, there's the European. But there's also West African and Native American, so my roots in this country go very deep.

Q: Well, certainly you've known and played with some remarkable players over the years.

I think we've had fun. There's a book called The Most Beautiful House in the World [Wharton professor and urban planner Witold Rybczynski's personal account of designing and building a new house, in which] there was one chapter that had a three letter word: F-U-N. I think about that a lot. What I mean, actually, is that the fun becomes a celebration of those great practitioners who've preceded us, and the honoring of the attempt we're making. It becomes a celebration of life and becomes a joy to be permitted to attempt to create that kind of sound environment. I also find that there is in my life, a certain water rising, or a wave, the ebb and fall of it. The pull is only occasioned by things that producers perhaps don't understand.

Q: Are there some younger players whose music you enjoy?

This idea about technique, people don't understand what that is. They talk about a certain wonderful trumpet player from New Orleans. That man has no technique! The reason he has no technique is because he hasn't developed a language. And the nondescript Roy Hargrove? Clever guy, but I heard him recently, ain't nothin' happenin'. He better practice!

I'll tell you an interesting guy that I heard, was a man named James Carter. The night before, I spent with [members of Carter's current electric band, drummer] Calvin [Weston] and Jamaladeen [Tacuma, electric bassist]. And the next night I go into practice, and in walks James Carter. So I ask him, he talked about his control over his instrument and he went into [talking about] Eric Dolphy. And I asked him what he thought about Anthony Braxton's music, and he dropped his head and said, "What can you say?"

So I said to him, "One courtesy deserves another. I'll be there tonight when you play," and lemme tell you! I'm backstage, and that band starts, and Jamaladeen and Calvin... you know there's a difference between the blues and rhythm and blues, and man, when that band started, the intensity of the new rhythm and blues that they played! Carter is off stage, and when he walked in he stunned me with what he do! Know what he did? He made one harmonic sound, [imitating] eeerrrrrrrrgh, and then he walked off the fucking stage! And he comes back and makes another sound. Now, when he starts playing, when he was confronted, when he had to deal with that rhythm and blues shit, it wasn't about notes. And when James did this obbligato, man, it wasn't just technical, it was passionate! So James, at the end of that first number came and gave us his theme that demonstrated all of his control, and it was something.

This is where I almost cried. He starts a piece, alone, and he's got a sense of humor, and he knew he had the audience, and he started playing "Good Morning Heartache". Gross, I was almost reduced to tears by what he did. I thought of Charlie Gayle, and he gave us that, but he also gave us Don Byas, and then he played softly, and went into a bossa nova...

When he walked off, I'm standing there mesmerized, and he sees me and comes over and I say, "Hey, give me some more of that shit!" [laughs] I gotta hear that band again, cause man, the music is alive!

Q: We've been talking about various different styles of music. Do you ever feel insulted when people use the term "jazz" to describe what you do?

Well, Ellington said to Mr. Gillespie, "Why do you let them call your music bebop? I call my music 'Ellingtonia'!" It's about American music that never existed in the world until we did it.

http://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2010/apr/14/cecil-taylor-jazz-piano

50 great moments in jazz: Cecil Taylor's jazz piano revolution

This 1956 interpretation of Thelonious Monk's typically flinty Bemsha Swing might not sound revolutionary at first. But listen closer..

Then you remind yourself that this was 1956, when the popular notion of jazz was Chet Baker and the lyrically purring Cool School. Pianist Cecil Taylor's 1956 album, Jazz Advance, heralded new approaches to jazz that would transform the music. Taylor's uncompromising stance brought him a tough decade for work opportunities after this, but he never stopped exploring and experimenting, and by the mid-1960s was regarded as one of the key figures in the free-jazz revolution alongside Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Albert Ayler. His piano vocabulary grew voluminous, his full-on virtuosity was dazzling, his performances were improvising marathons.

I first found myself in the path of just such a Taylor piano typhoon when I heard a 1968 recording by New York's Jazz Composer's Orchestra, a co-operative that, at the time, included free-jazz luminaries Pharoah Sanders on sax and Don Cherry on trumpet. Taylor was the improvising soloist for more than half an hour on a two-part piano concerto entitled Communications (which at the time seemed like an ironic title to me). The eddies and whirlpools of jazz motifs and classical references in that playing were so densely intermingled they seemed almost impossible for the untutored listener to unpick. For years, it was a radicalism that consigned one of the great 20th-century virtuoso improvisers to dishwashing jobs in clubs that wouldn't let him on the bandstand.

In later years, when his singular vision was recognised, Taylor would pick up art-music citations by the barrow-load. He found himself sharing prestigious panel discussions on contemporary music with Pierre Boulez and playing for the ballet legend Mikhail Baryshnikov (who claimed Taylor revealed to him "another dimension about dancing to music").

Raised by an adoring mother, Taylor was a piano prodigy. He studied Stravinsky, Bartók and Elliott Carter at the New England Conservatory, and Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell and Duke Ellington in his spare time; the latter influences are fitfully clear on Bemsha Swing. The fruit of this education was one of the most culturally diverse piano styles in jazz.

Taylor's self-discipline, isolation and unwavering focus perhaps resulted in an approach so demandingly personal as to influence mainstream jazz piano hardly at all, but the inspiration of his unflinching courage to the international avant garde has been immense. European free-improv stars such as Evan Parker, Han Bennink and the late Derek Bailey became his playing partners, and the innovative British percussionist Tony Oxley has been his regular drummer for years. Taylor's breakthroughs in changing the notion of swing, improvising without chords, and spontaneous composition – combining the timbres and intonations of jazz with the vocabulary of contemporary conservatoire music – opened up new avenues for both improvisers and composers.

I interviewed Taylor in the late 1980s for the Guardian, and two remarks of his stick in my mind. One was the piece of advice he said he received in his youth from the pianist Freddie Redd: "Cecil, whatever you're doing, and I'm not sure I know what that is, don't let anybody tell you not to do it." The other concerned the impact of his mother's belief in him. Taylor described "the difficulty that I had with certain major jazz impresarios on the rare occasions they claimed they were going to make me star. Mama had already made me a galaxy. So I knew those people don't really give you anything. They say, 'We will give you money, but we want you to play this, or that'. And I always thought, if I'm going to do that, I might as well go back and be a dishwasher."

http://www.themorningnews.org/archives/profiles/cecil_taylor_explains_it_all.php

by John S. Wilson

New York Times

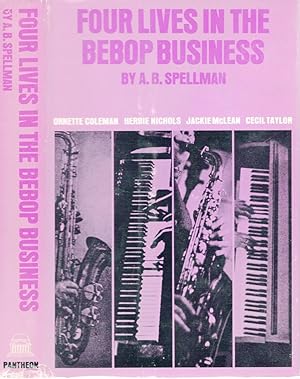

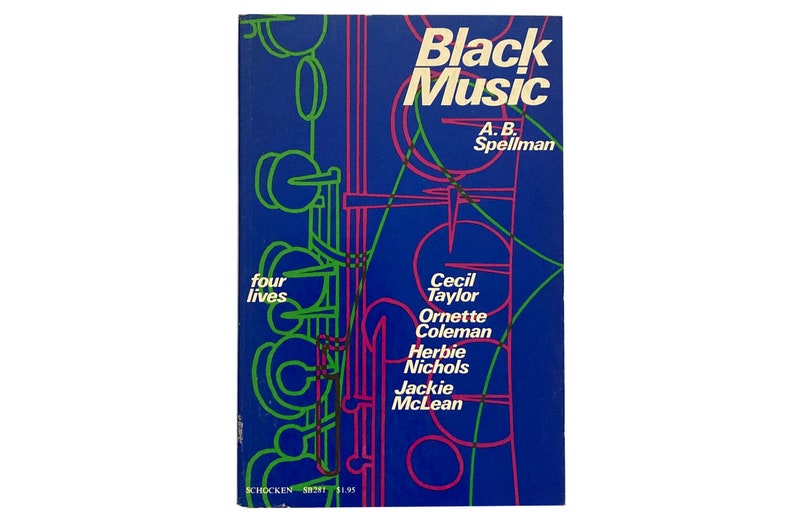

This "peculiar cross-pollination of show business and serious modern jazz" is what A.B. Spellman refers to as "the bebop business." To explore the problems that the mixture raises for contemporary musicians--specifically, for the black American musician--Spellman has examined the careers of four unusually talented jazzmen who have tried to cope with these circumstances with varying degrees of success: Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, two of the most controversial jazz musicians of the past decade (and, in Spellman's view, two of the three most important new musicians off the decade--John Coltrane is the third); Herbie Nichols, a pianist whose potential was unfulfilled when he died in 1963; and Jackie McLean, a teen-aged prodigy of the bebop era, who has survived to find a prominent place in present day jazz.

Survival, often under the direst circumstances, is one of the recurring notes in all four stories. Coleman has actually been beaten up, had his saxophone smashed, by people who did not like the way he played. Taylor is a pianist who has to express himself on, at best, half an instrument. He showed Spellman his own piano.

"Not more than half of it works," he said. "In a way, this piano is me: It half works. I get to work about half the year. Everything that's wrong with it, I did to it. I knocked those keys out. I can look at that piano and see my work from the last few years. But you know, a cat playing classical music who had come this far would be getting free pianos, because it is good for the industry. Not me, baby. The pianos I get to play on are never more than 60 per cent, have most of the ivory off the keys, and they are never in tune. Now what is that going to do for my music?"

Taylor, Coleman and Nichols have encountered relentless antagonism, not only from night club operators who were reluctant to hire them and from audiences that wanted familiar sounds, but from fellow musicians who refused "to play with them. McLean was never an outsider in this sense. But he started down a path that destroyed many young musicians of the bop period, one that included narcotics addiction.

Spellman steers clear of the misty romanticism that often colors writing about the struggles of jazz musicians. He views these men with a perceptive and understanding eye, digging through the protective surfaces and telling much of their stories in skillfully edited direct quotations that have the ring and bite of reality.

His piece on Taylor is a particularly provocative portrait of a thorny, adamant and penetrating individual with a delightfully mordant wit. It sums up much of the essence of the book. It is Taylor who provides Spellman with a microcosm of the endless, Job-like adversities that can follow an innovator through the contemporary jazz world. And it is Taylor's thoughtful analysis of the relation of European music to the cultural aspirations of the white American and the black American that clarifies not only for justification for "serious jazz" as opposed to jazz as entertainment but also the underlying reasons why he and other likeminded musicians persist in the face of alienation and frustration that are their steady lot.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

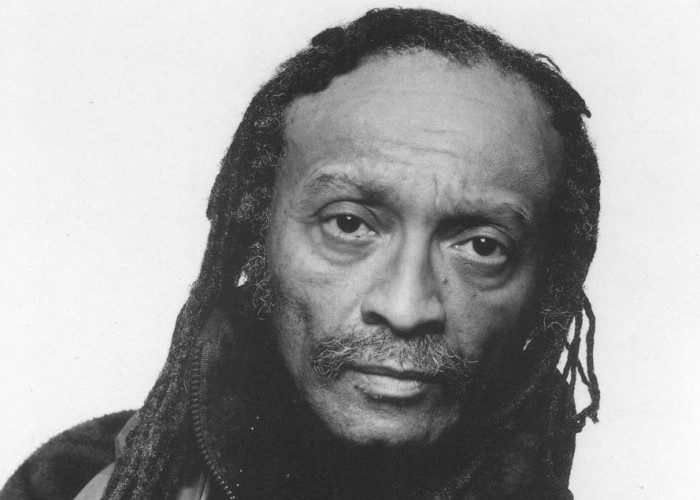

http://www.chrisfelver.com/films/taylor.html

Seated at his beloved and battered piano in his Brooklyn brownstone the maestro holds court with frequent stentorian pronouncements on life, art and music while demonstrating his technique and views infusing his super clustered playing. Students at Mills College, where Taylor has a regular teaching gig, devise an avant-garde “free composition” under his generous tutelage. Taylor plays with his band at Yoshi’s in Oakland, NYC’s Lincoln Center, and the Iridium with his large ensemble Orchestra Humane.

Since the 1950’s Taylor has steadfastly represented jazz’s avant-garde, a fact reinforced by notable commentators Elvin Jones, Amiri Baraka, Nathaniel Mackey, and Al Young. The recording of the UCLA Royce Hall solo performance is an example of his astounding mastery of complex musical constructions. All the Notes is an intimate portrait of a consummate musician and sound thinker in triumphant maturity, bringing out Taylor’s nobility, devotion and belief in a truth that can only be found after a lifetime of invention.

being matter ignited...

an interview with Cecil Taylor

text by Chris Funkhouser

published in Hambone, No. 12

Fall, 1995

Nathaniel Mackey, editor

Pianist-composer Cecil Taylor is internationally known for the brilliance and audacious beauty of his music. He has recorded dozens of albums as a solo performer and with various ensembles over a period spanning five decades. He is currently working with a large ensemble called Phthongos. He has incorporated poetry into his work in a number of ways over the years; in 1991 Leo Records released Chinampas, a recording which presents his poetry accompanied by multiinstrumental improvisations. The following interview, conducted by Chris Funkhouser, took place at Mr. Taylor's home in Brooklyn on September 3, 1994.

Funkhouser: Let's explore the literary side of the work that you do. With the exceptions of people like Sun Ra, Archie Shepp, and a few others, there aren't many jazz players who choose to work with words as a mode of expression. I wanted to ask you about your poetry, where you're coming from when you write it down or are presenting it vocally.

Taylor: Well, I don't know what jazz is. And what most people think of as jazz I don't think that's what it is at all. As a matter of fact I don't think the word has any meaning at all, but that's another conversation...

It seems to me that one of the things that is true with every--oh, for instance--like this Irish writer, William Kennedy. In reading some of his stories about life, his family members in Albany--the thing that struck me, the similarity, and the things that makes human beings who are vital electric, is the way they use language to manifest their live responses to the culture that they are in. So I got that from that. In a way, in its own way, it's like when I was very young I read Langston Hughes' Simple stories and it whetted my appetite for the possibility of using language to move outside of the self.

One of the most important things that happened to me, really--I've always had difficulty with teachers in school. Right after Pearl Harbor I wrote this poem about December 8th--I don't even know why I remember this--and the teacher said, "Oh, that's a very bad poem." Well, I knew that I should write poetry then. If she said it was bad, then it must be okay.

When I was in the Conservatory, there was a Southern woman who taught English the first year that I was there. English--well, English--American language is quite different, actually. She was talking about Tennessee Williams, and she was talking about Streetcar, and she said, 'The language in that play...there are sections of that play that are so good,' she said,'...that I could actually taste it.' And that was one of the most remarkable things that happened to me in the whole four years that I was at the Conservatory. Cause I only had three teachers, really, that were interesting, and all three of them were women. I was sixteen when that was said to me, and I remember of course when Streetcar was on Broadway--I certainly didn't see it, but I did see Talleulah Bankhead do it years later--this was a time when I was in a new environment for me. A new musical community environment, The New England Conservatory [laughs], and whatever that was about. But I was also at that point beginning to construct certain things musically. I was beginning to. And because what was important about this English woman--this English teacher--I wish I could remember her name cause I can see her--and what she gave to me--because she gave it in a not punitive way. Mother always had me reading. Mother spoke French and German and brought Shopenhauer to me when I was eleven years old, but that was something else--that was-- you didn't have a choice there with mother. Boom! That's the way that went. But here was this woman who just said this, and it I heard it. And her emotional dedication to a word--I said, "Wow...that's my dedication to music...you mean it is possible to have that kind of dedication to another art?" So, that.

I never understood how musicians could play music for poets and not read poems. I don't understand musicians who can play for dancers and not know how to dance. I mean, it's very interesting to me, you were talking about your research; well, one of the things--before I put words down, I probably have read a thousand words.

I have a lot of interests. Dance is certainly one. Architecture, particularly structural engineers. I look at basketball. I'm not interested in it though. I love horses, horseracing. I've never seen a horse race. I can remember Sea Biscuit and those things, though. I used to run when I was young. I do all these exercises everyday.

I did write a poem about Nureyev, when I saw him dance. I also wrote a poem about Albert Ayler, too. I think that for me the idea is to--I mean it changes, you know, every ten years or so--but right now I'm going through this whole thing about making these belated discoveries about mother dear. And what that really means is these few years that I have left here to really deal with a certain kind of upward- mobile bourgeoisie nonsense that entrapped a lot of--but anyway, the poetry saved my life, actually.

If you have the opportunity to play for people all in different countries, one of the things you begin to discover is that people are--you can find oppressed people all over the world, therefore somewhere along the road you get the idea that it is certainly not about yourself. Any gift that you have is not about that at all. It's about a force that is about the ungiven, the uncreative. It is about the amorphous, and you are at best merely a vessel. And once you begin to understand that [laughs]--the wonderful thing about it is--I was thinking about it today--that the first time I heard Billie Holiday, I heard it in the room of a member of the family who was not very well thought of, and the other part of the family all liked Bing Crosby. And that was alright, but there is a qualitative difference. So in our small way what we attempt to do is to look and see and receive and become a sponge and attempt to make anything that exists as part of the palette to describe whatever it is we think we want to do. And what you want to do is to be as beautiful and as loving and as all-consuming as possible, so that the statement has many, many different implications, and it has many different levels. The only way to do that, seems to me, is to research.

I think what my mother did give me unquestionably was that--maybe she didn't quite perceive it this way but--it is wonderful to be able to enjoy what it is I do now as opposed to the disciplinary aura that I had to grow up under. Now I do what I want to do because I love doing it, and it rewards me and I've been fortunate in that I've been told that other people have gotten something from what it is. It is possible to do what it is you decide you want to do with your life. For me that has been the thing that has cured whatever despondency, whatever anger, you know...well, that's that.

Funkhouser: You couldn't have been very old when you wrote a poem about Pearl Harbor--so you've been writing from elementary school onward?

Taylor: Well, actually, you know teachers--I ran into a lot of teachers where it was very clear to me that if you didn't do what they told you to do, they would try to stop you from doing anything at all. That's what that teachers do. When I went to the Conservatory, it was the same thing, and boy did I fight with those people up there. Actually, I can tell you when I started writing but that wouldn't be very interesting, cause that was all about romance. And of course that's what it is about, isn't it? But I really started writing in 1962 when I went to Europe for the first time. I was writing letters to this poet, who I was quite taken with at the time. That's when I started writing.

Funkhouser: You were playing before that. Was there a point where the writing and playing began to coincide somehow? I know I've seen you perform and it's chanting, and all sorts of...

Taylor: That's the wonderful thing about maybe never being allowed to get into the business--the music business-- because I was not a very well-behaved person according to the gangsters who control the business. I'm lucky to be alive, really. So what you had to do--and also the fact that what I was doing was considered not very viable. [Laughs] That's a cute word to mean it didn't make any money, or they didn't see how they could make any money. And they would tell you what you were supposed to do. That's the way they are. So, not being malleable that way, the resources that my mother and father gave me, since I didn't have any money--but my father would always give me money. When I wasn't working I always went to see plays on Broadway. Then years later, this woman that I was sort of involved with worked at the Living Theater. So I got a whole new concept, and a whole new thrust of beauty right there, you see. And actually I ran into Baraka around '57. So, what I mean is that one dedication leads to another, especially if it is very important for you to continue to grow, especially when they tell you that "We're not going to allow you to grow in this area." So what does that mean? Meant I had to practice at home. It also meant that I had to look around for other sources of beauty that could aid in what I was doing with the main thing. Then finally, you see, these things mesh, and it takes a while for it to happen. But then, you know, it does.

And so therefore there is no possible way that I can have any regrets about not working, where these other people did. Cause I was always working. I just didn't make any money. [Laughter]

Funkhouser: You said poetry saved your life . . .

Taylor: Yes it did. I had one or two friends that helped. But the work always brought me back. For instance, this work that I'm working on now, which has a lot to do with my mother, actually, and my relationship to her as a property of hers. Unwanted property, it seemed to me, possibly. I mean I have to think of that as a certain reality because of her attempts to kill me at a certain point. Literally. However, the fantastic thing about all of this is that if you survive, then you understand that your parents had parents too. And that must have been a trip. The extraordinary anger that I began to see that was in my family, and resulted in, really, her death at the age of thirty-four, and the death of all people in the family who followed her conception of living, because she was very powerful and very persuasive. And there were at least three people in the family who died of cancer at the age of thirty-four. Given the fact that she had been in silent movies, and that she recited poetry, and that she'd walk into a room and the room would stop--but then she found father, and father was from North Carolina, and he was an agricultural person and she was his dream. She could speak French and German, she knew how to wear clothes, and all of that shit. And then she stopped because we had the only brick house--there were only two brick houses on the block--and pop owned one. She became the lady of the manor. And I became her--so I was tapdancing when I was six. I was entering contests for young virtuosos--I was never a young virtuoso--but she tried to make me--so I was playing Chopin when I was six and all this nonsense. And I was driven. There was no--I was telling someone the other night, I said, 'I've never--I could not be idle'--you had to be doing something. And so of course, she died when I was eleven, twelve--twelve, yeah--and I had a peptic ulcer when I was thirteen. It was just a glorious experience growing up in her house. However, she gave me certain things. She was the eldest of six children, after all; her mother was Cherokee. Her father was never mentioned. Father's father--he had a great deal of problems with him-- he was Kiowa. And all of this I had to discover, and this is the language of--the language of the word is now coming to deal with all of that.

Funkhouser: Is it much different than what you were doing with Chinampas, where you were going back to another set of . . .

Taylor: Well, Chinampas is about those extraordinary Aztecs. You see, the Aztecs, you might say, are my distant relatives too because there is Kiowa and Cherokee. So we're dealing with native americans, and I'm interested in--oh, man, the culture. Like there is an extraordinary Mexican structural engineer named Felix Candello, who has done this restaurant--his most famous work--the only one that I know, actually--is this restaurant that he has constructed outside of Mexico City.

In order to deal with this, it becomes--there is like a difference between therapy, because I've been in therapy-- the last therapist I had was really very much like my father. He ended up in A.A., too. I don't even know whether he's even alive now. When you have the choice to work out your own, or to begin to see into your own emotional mechanisms, and then begin to discover who set them up for you, who gave you these intrapersonal tactics that keep you from being ever-vulnerable--and when you do it through your own experience and maybe you have one friend who does not allow you to get away with certain things--then there's always the whatever we are as people.

Our work is always perhaps more whole than we, and when you really begin to move as a human being then you begin to see the disparity between what is not an abstraction but becomes an emotional force that is akin--it is the same thing as the intellectual perception, which I feel-- cause all of the most amazing poets that I've ever--and when I use the word poet I mean Ben Webster or Billie Holiday, or Maya Pelisetskaya or the incredible Carmen Amaya. You know, these great dancers who when you see them you know that that's a life, and when you look at them they've taken yours. Because you see them and you say, "Jesus, if I ever grow up that's what I'd like to do, that's what I'd like to give."

Funkhouser: It's inside your body, something that enters your body, then . . .

Taylor: A spirit! That force, you know--I realize that my mother had that force. But what she decided not to do with it--and if you have that force and you don't use it, then you die. Because if you kill that force your body follows afterwards. My uncle, her only brother, he could live in the house with us as long as he would not be a musician. And he died of cancer at the age of thirty-four. He gave me drum lessons.

A lot of my rage was really dealing with the hypocrisy of the upwardly mobile middle-class aspirations of certain groups of people that I grew up with. And they all--I mean for instance, I had a cousin who had a beautiful voice, and they convinced her that she was too ugly to sing! [Laughter]

Funkhouser: You feel certain kinship with Aztec and the sensibilities that they developed? There was a group that ran into all kinds of trouble--and what a highly developed sense of spirit...

Taylor: What I am saying is two things: because mother insisted that I do certain things, there was a seed so that when it was left up to me to find certain things, the richness of these other poetical universes I had already had reference to.

Now, I'd rather not talk about my political adventures, beyond saying this: when I was very young, I went to the second Peekskill rally. Paul Robeson was there, [W.E.B.] DuBois was there, and it was in an area that my father's boss lived in. And what happened to me then, and I was thirteen--and the family read the Daily News at that time-- and we were lucky to get out of Peekskill alive. When I got back Monday and I read the Daily News reportage of what they said had happened, then I knew that I had to have other options because that is not what I experienced. And if they were going to say that that's what was happening then I knew that I had to choose another course.