AS

OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN

THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON

NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/01/nina-simone-1933-2003-legendary-and.html

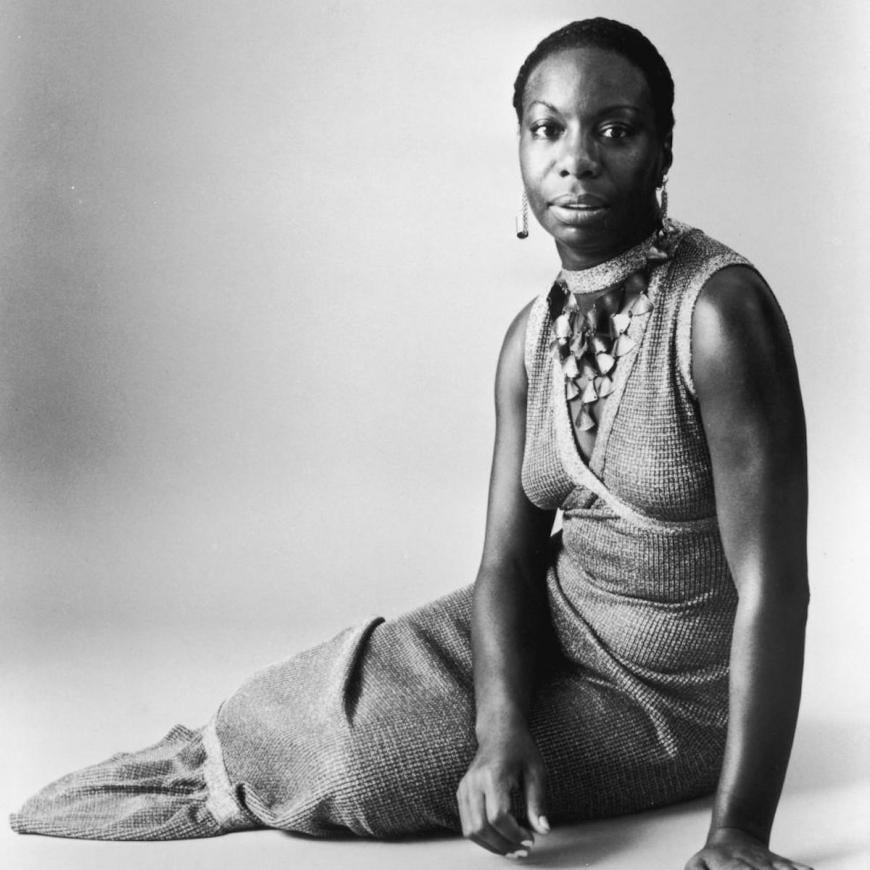

PHOTO: NINA SIMONE (1933-2003)

http://www.ninasimone.com/

Bio

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/nina-simone-mn0000411761

Nina Simone

(1933-2003)

Biography

by Mark Deming

Nina Simone was one of the most gifted vocalists of her generation, and also one of the most eclectic. Simone was a singer, pianist, and songwriter who bent genres to her will rather than allowing herself to be confined by their boundaries; her work swung back and forth between jazz, blues, soul, classical, R&B, pop, gospel, and world music, with passion, emotional honesty, and a strong grasp of technique as the constants of her musical career.

Nina Simone was born Eunice Kathleen Waymon in Tryon, North Carolina on February 21, 1933. Her mother, Mary Kate Waymon, was a Methodist minister, and her father, John Divine Waymon, was a handyman who moonlighted as a preacher. Eunice displayed a precocious musical talent at the age of three when she started picking out tunes on the family's piano, and a few years later she was playing piano at her mother's Sunday church services. Mary Kate worked part time as a housemaid, and when her employers heard Eunice play, they arranged for her to study with pianist Muriel Mazzanovich, who tutored Eunice in the classics, focusing on Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, and Schubert. After graduating at the top of her high school class, Eunice received a grant to study at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, and applied for enrollment at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. However, Eunice was denied admission at the Curtis Institute under mysterious circumstances, despite what was said to be a stellar audition performance; she would insist that her race was the key reason she was rejected.

Determined to support herself as a musician, Eunice applied for a job playing piano at the Midtown Bar & Grill in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1954. Eunice was told she would have to sing as well as play jazz standards and hits of the day. While she had no experience as a vocalist, Eunice faked it well enough to get the job, and she adopted the stage name Nina Simone -- Nina from a pet name her boyfriend used, and Simone from the French film star Simone Signoret. The newly christened Nina Simone was a quick study as a singer, and her unique mixture of jazz, blues, and the classics soon earned her a loyal audience. Within a few years, Simone was a headliner at nightclubs all along the East Coast, and in 1957 she came to the attention of Syd Nathan, the mercurial owner of the influential blues and country label King Records. Nathan offered Simone a contract with his jazz subsidiary, Bethlehem Records, and the two were soon butting heads as the strong-willed Simone insisted on choosing her own material. Simone won out, and in 1958, she enjoyed a major hit with her interpretation of "I Loves You Porgy" from Porgy and Bess. The single rose to the Top 20 of the pop charts, but like many of Nathan's signings, Simone did not see eye to eye with him about business details (particularly after she discovered she'd signed away her right to royalties upon receiving her advance), and by 1959 she had signed a new deal with Colpix Records.

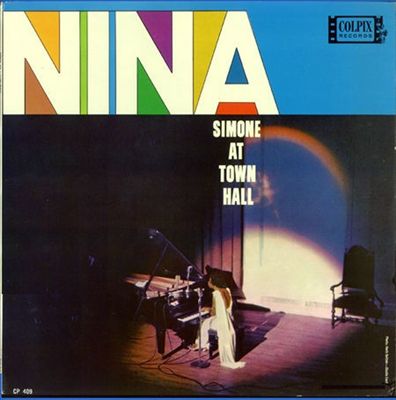

Simone's reputation as a powerful live performer had only grown by this time, and her second album for Colpix was the first of many live recordings she would release, Nina Simone at Town Hall. Simone's live performances gave her more room to show off her classical piano influences, and her albums for Colpix reflected an intelligent taste in standards, pop songs, and supper club blues, and while she didn't enjoy another American hit on the level of "I Loves You Porgy," her recordings of "Trouble in Mind" and "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out" both entered the pop charts as singles. (Simone's 7" releases for Colpix were later compiled into a collection from Rhino Records, 2018's The Colpix Singles.)

In 1964, Simone left Colpix to sign a new deal with Philips, and the move coincided with a shift in the themes of her music. While always conscious of the ongoing struggle for civil rights, Simone often avoided explicit political messages in her material; as she later wrote, "How can you take the memory of a man like Medgar Evers and reduce all that he was to three-and-a-half minutes and a simple tune?" But as the fight for racial equality became a more pressing issue in America, Simone began addressing issues of social justice in her music, penning songs such as "Mississippi Goddam," "Four Women," and "Young, Gifted and Black," the latter inspired by the work of her friend and mentor Lorraine Hansberry. Simone also enjoyed a British hit single in 1964 with "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood," and while the record didn't fare as well in the United States, a year later the Animals would take the song to the pop charts on both sides of the Atlantic. Simone would next hit the British charts with her cover of Screamin' Jay Hawkins' "I Put a Spell on You," which also rose to the Top 30 in the States.

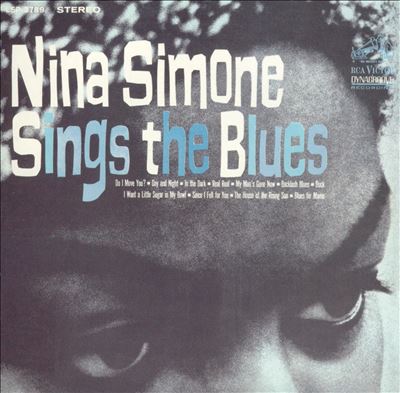

In 1967, after recording seven albums for Philips, Simone struck a new deal with RCA Records, and while her first album for her new label, Nina Simone Sings the Blues, was a straightforward collection of blues standards, her subsequent work for RCA found Simone focusing on contemporary pop, rock, and soul material, much of which dealt with topical themes and progressive philosophies (1969's To Love Somebody featured no fewer than three Bob Dylan tunes). Simone's 1968 cover of "Ain't Got No/I Got Life" (from the musical Hair) was a major chart hit in the U.K., and Simone would focus her energies on her European career when she left the United States in 1970, initially settling in Barbados and divorcing her husband and manager. Simone's exile was prompted by her increasing disillusionment with American politics, as well as her refusal to pay income taxes as a protest against U.S. involvement in Vietnam, though recording sessions and concert dates would occasionally bring her back to the United States. In 1974, Simone released her last album for RCA, It Is Finished, and spent the next several years traveling the world and playing occasional concerts; she would not return to the recording studio until 1978, when she recorded the album Baltimore at a studio in Belgium for Creed Taylor's CTI label. (That same year, Simone was arrested and charged for her non-payment of taxes from 1971 to 1973.) It would be another four years until Simone would record again, cutting Fodder on My Wings for a Swiss label in 1982.

After several more years of travel, Simone released a live album through the American VPI label, 1985's Live & Kickin, and another concert set, Let It Be Me, was issued by Verve in 1987, a year that saw Simone enjoying a major career resurgence in Europe; her 1959 recording of "My Baby Just Cares for Me" was used in a British television commercial for Chanel No. 5 perfume, and the song subsequently became a hit, rising to the Top Ten of the U.K. pop charts. In 1989, Simone was invited by Pete Townshend to sing the song "Fast Food" on his concept album The Iron Man, which also featured John Lee Hooker. Simone's autobiography I Put a Spell on You was published in 1990, and after a well-received United States concert tour, she was signed by Elektra Records, which released the album A Single Woman in 1993.

In 1995, Simone found herself in the news after she fired a gun at one of her neighbors during an argument; she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which was said to be the cause of several episodes of erratic behavior in her later years. Simone continued to perform live in Europe and the United States up until the summer of 2002, when it was discovered she had breast cancer. Simone's battle with the disease came to an end on April 21, 2003 in Carry-le-Rouet, France. Only a few days earlier, Simone had received an honorary degree from the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, the same school that had rejected her in 1953.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/nina-simone/

Nina Simone

The High Priestess

Eunice Waymon was born in Tryon, North Carolina as the sixth of seven children in a poor family. The child prodigy played piano at the age of four. With the help of her music teacher, who set up the "Eunice Waymon Fund", she could continue her general and musical education. She studied at the Julliard School of Music in New York.

To support her family financially, she started working as an accompanist. In the summer of 1954 she took a job in an Irish bar in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The bar owner told her she had to sing as well. Without having time to realize what was happening, Eunice Waymon, who was trained to become a classical pianist, stepped into show business. She changed her name into Nina ("little one") Simone ("from the French actress Simone Signoret").

In the late 50's Nina Simone recorded her first tracks for the Bethlehem label. These are still remarkable displays of her talents as a pianist, singer, arranger and composer. Songs as Plain Gold Ring, Don't Smoke In Bed and Little Girl Blue soon became standards in her repertoire.

One song, I Loves You, Porgy, from the opera "Porgy and Bess", became a hit and the nightclub singer became a star, performing at Town Hall, Carnegie Hall and the Newport Jazz Festival. Even from the beginning of her career on, her repertoire included jazz standards, gospel and spirituals, classical music, folk songs of diverse origin, blues, pop, songs from musicals and opera, African chants as well as her own compositions.

Combining Bachian counterpoint, the improvisational approach of jazz and the modulations of the blues, her talent could no longer be ignored. Other characteristics of the Simone art are: her original timing, the way she uses silence as a musical element and her often understated live act, sitting at the piano and advancing the mood and climate of her songs by a few chords.

Sometimes her voice changes from dark and raw to soft and sweet. She pauses, shouts, repeats, whispers and moans. Sometimes piano, voice and gestures seem to be separate elements, then, at once, they meet. Add to this all the way she puts her spell on an audience, and you have some of the elements that make Nina Simone into a unique artist.

When four black children were killed in the bombing of a church in Birmingham in 1963, Nina wrote Mississippi Goddam, a bitter and furious accusation of the situation of her people in the USA. The strong emotional approach of this song and the others on her first Philips record ("Nina Simone In Concert"), would become another characteristic in her art. She uses her voice with its remarkable timbre and her careful piano playing as means to achieve her artistic aim: to express love, hate, sorrow, joy, loneliness - the whole range of human emotions - through music, in a direct way.

One moment, she is the actress who turns a Kurt Weill- Bertold Brecht song as "Pirate Jenny" into great theater, then, after a set of protest songs, she will sing Jacques Brel's fragile love song "Ne Me Quitte Pas" in French.

Although Nina was called "High Priestess of Soul" and was respected by fans and critics as a mysterious, almost religious figure, she was often misunderstood as well. When she wrote Four Women in 1966, a bitter lament of four black women whose circumstances and outlook are related to subtle gradations in skin color, the song was banned on Philadelphia and New York radio stations because "it was insulting to black people..."

The High Priestess would walk different paths to find the adequate music to spread her message. Her first RCA album, "Nina Simone Sings The Blues", includes her own "I Want A Little Sugar In My Bowl", "Do I Move You?", a haunting version of My Man's Gone Now (again from "Porgy & Bess") and the protest song Backlash Blues, based on a poem written for her by Langston Hughes.

Her repertoire includes more Civil Rights songs: Why? The King of Love is Dead, capturing the tragedy of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Brown Baby, Images (based on a Waring Cuney poem), Go Limp, Old Jim Crow, … One song, To be Young, Gifted and Black, inspired by Lorraine Hansberry's play with the same title, became the black national anthem in the USA.

She surprised even her most devoted fans with an album on which she sings and plays alone. "Nina Simone And Piano!", an introspective collection of songs about reincarnation, death, loneliness and love, is still a highlight in her recording career.

Her gift to give new and deeper dimensions to songs resulted in remarkable versions of "Ain't Got No / I Got Life" (from the musical "Hair"), Leonard Cohen's "Suzanne", Bee Gees songs as "To Love Somebody", the classic "My Way" done in a tempo doubled on bongos, "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues" and four other Bob Dylan songs. This gift culminated on her record "Emergency Ward": she set up an atmosphere that left no illusions and no escape, performing two long versions of George Harrison songs: "My Sweet Lord" (to which she added a David Nelson poem, "Today is a Killer") and "Isn't it a Pity."

But Nina tried to escape anyway. She felt she had been manipulated. Disgusted with record companies, show business and racism, she left the USA in 1974 for Barbados. During the following years she lived in Liberia, Switzerland, Paris, The Netherlands and finally the South of France, where she is still residing. In 1978 a long awaited new record was released, "Baltimore", containing the definite rendition of Judy Collins' My Father and an hypnotizing "Everything Must Change."

Her next album, "Fodder On My Wings", was recorded in Paris in 1982 and is based on her self-imposed "exile" from the USA. More than ever determined to make her own music, Nina wrote, adapted and arranged the songs, played piano and harpsichord and sang in English and French. The 1988 CD re-release of this album included some bonus tracks, e.g. her extraordinary version of Alone Again Naturally, reminiscing her father's death.

In 1984, one of her concerts at Ronnie Scott's in London was filmed, resulting in a captivating video, featuring Paul Robinson on drums. A song from her very first record, "My Baby Just Cares For Me", became a huge hit and "Nina's Back" was not only the title of a new album; her concerts would take her all over the world again.

In 1989 she contributed to Pete Townsend's musical "The Iron Man". In 1990 she recorded with Maria Bethania; in 1991 with Miriam Makeba. That same year, her autobiography, "I Put A Spell On You" was published. It was translated into French ("Ne Me Quittez Pas"), German ("Meine Schwarze Seele") and Dutch ("I Put A Spell On You, - Herinneringen").

In 1993 a new studio album was released. "A Single Woman" includes several Rod McKuen songs, Nina's own Marry Me, her version of the French standard Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux and a very moving Papa, Can You Hear Me?

No less than five songs from her repertoire were used in the 1993 motion picture sound track of "Point Of No Return" (also called "The Assassin, code name: Nina"). Many other films feature her songs (e.g. "Ghosts of Mississippi", 1996: I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free, "Stealing Beauty", 1996: My Baby Just Cares For Me and "One Night Stand", 1997: Exactly Like You).

Her music continues to excite new and young listeners. Ain't Got No / I Got Life was a big hit in 1998 in The Netherlands, just as it had been there 30 years before...

Together with her regular accompanists Leopoldo Fleming (percussion), Tony Jones (bass), Paul Robinson (drums), Xavier Collados (keyboards) and her musical director Al Schackman (guitar), she still excites audiences all over the world. At the Barbican Theatre in London in 1997 she sang Every Time I Feel The Spirit as a tribute to one of America's first and foremost leaders in the cause of Civil Rights, peace and brotherhood, singer and actor Paul Robeson. More spirituals and "blood songs" would follow: Reached Down And Got My Soul, The Blood Done Change My Name and When I See The Blood.

Nina was the highlight of the Nice Jazz Festival in France in 1997, the Thessalonica Jazz Festival in Greece in 1998. At the Guinness Blues Festival in Dublin, Ireland in 1999 her daughter, Lisa Celeste, performing as "Simone", sang a few duets with her mother. Simone has toured the world, sung with Latin superstar Rafael, participated in two Disney theatre workshops, playing the title role in Aida and Nala in The Lion King. She is currently working on her upcoming debut album, "Simone Superstar".

On July 24, 1998 Nina Simone was a special guest at Nelson Mandela's 80th Birthday Party. On October 7, 1999 she received a Lifetime Achievement in Music Award in Dublin.

In 2000 she received Honorary Citizenship to Atlanta (May 26), the Diamond Award for Excellence in Music from the Association of African American Music in Philadelphia (June 9) and the Honorable Musketeer Award from the Compagnie des Mousquetaires d'Armagnac in France (August 7).

Dr. Simone passed away after a long illness at her home in her villa in Carry-le-Rouet (South of France) on April 21, 2003. As she had wished, her ashes were spread in different African countries.

The Diva, who was as well an Honorary Doctor in Music and Humanities, has an unrivalled legendary status as one of the very last 'griots". She is and will forever be the ultimate songstress and storyteller of our times.

[by Roger Nupie, President "International Dr. Nina Simone Fan Club"]

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on February 23, 2011):

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

The Magnificent Nina Simone (1933-2003)

Nina Simone: "That Blackness"

(From 1968 interview)

Released by the Estate of Nina Simone:

"That Blackness" (Part 2)

Released by the Estate of Nina Simone: Recording session & Interview:

Nina Simone

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nina Simone Live in Holland '65 & England '68:

Holland 1965:

Rudy Stevenson (Guitar,) Lisle Atkinson (Bass) Bobby Hamilton- (Drums)

Sam Waymon (Organ, Vocal, Percussion) Henry Young (Guitar) Gene Taylor (Bass) Buck Clark (Drums)

NINA SIMONE COLLECTION:

Tracklist:

Nina Simone - "Why? (The King of Love is Dead)" [Full Live Version]:

Recorded on April 7, 1968, live three days after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. and performed at the Westbury Music Fair. Nina Simone dedicated her performance to King's memory. The song was written by her bass player, Gene Taylor. An edited version of this performance appears on Simone's album, Nuff Said (1968). I felt the unedited version captures the true emotional energy of the period surrounding Simone's performance.

In 1968 RCA released "Nuff Said" a very heavily edited version of this performance. It was supposed to be a "live" album. Some songs were edited, some were remixed and some songs were studio recordings passed off as live.

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/21/movies/nina-simones-time-is-now-again.html

Nina Simone’s Time Is Now, Again

Nina Simone is striking posthumous gold as the inspiration for three films and a star-studded tribute album, and she was name-dropped in John Legend’s Oscar acceptance speech for best song. This flurry comes on the heels of a decade-long resurgence: two biographies, a poetry collection, several plays, and the sampling of her signature haunting contralto by hip-hop performers including Jay Z, the Roots and, most relentlessly, Kanye West.

Fifty years after her prominence, Nina Simone is now reaching her peak.

The documentary “What Happened, Miss Simone?,” directed by Liz Garbus (“The Farm: Angola, USA”) and due on Wednesday in New York and two days later on Netflix, opens by exploring Simone’s unorthodox blend of dusky, deep voice, classical music, gospel and jazz piano techniques, and civil rights and black-power musical activism.

Not only did she compose the movement staple “Mississippi Goddam,” but she also broadened the parameters of the great American pop artist. “How can you be an artist and not reflect the times?” Simone asks in the film. “That to me is the definition of an artist.” And in “What Happened,” Simone emerges as a singer whose unflinching pursuit of musical and political freedom establishes her appeal for contemporary activism.

Simone’s androgynous voice, genre-breaking musicianship and political consciousness may have concerned ’60s and ’70s marketing executives and concert promoters, but those are a huge draw for today’s gay, lesbian, black and female artists who want to be taken seriously for their talent, their activism or a combination of both.

“Nina has never stopped being relevant because her activism was so right on, unique, strong, said with such passion and directness,” Ms. Garbus said in an interview at a Brooklyn bakery. “But why has she come back now?” she asked, answering her own question by pointing to how little has changed, citing the protests over the police killings of unarmed African-Americans like Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, Eric Garner and Freddie Gray.

While Simone’s lyrical indictment of racial segregation and her work on behalf of civil rights organizations connects her to our contemporary moment, those closest to her felt more comfortable telling Simone’s story after her death in 2003. As Ms. Garbus said, “From a filmmaking point of view, the answer for her return is also because of the estate, and people being ready to relinquish some control of her story.”

In this case, it was Simone’s daughter, the singer and actress Lisa Simone Kelly, who shared personal diaries, letters, and audio and video footage with Ms. Garbus and has an executive producer credit on the film. Speaking by phone from her mother’s former home in Carry-le-Rouet, France, Ms. Kelly said: “It has been on my watch that this film was made. And I believe that my mother would have been forgotten if the family, my husband and I, had not taken the right steps to find the right team for her to remembered in American culture on her own terms.”

The most high-profile controversy about Simone’s legacy, however, involves Cynthia Mort’s biopic, “Nina,” due later this year. Starring Zoe Saldana in the title role, the film was initially beleaguered by public criticism over the casting, an antagonism further fueled by leaked photos of Ms. Saldana with darkened skin and a nose prosthetic. Eventually, the film’s release was set back even more by Ms. Mort’s own 2014 lawsuit against the production company, which she accused of hijacking the film, as The Hollywood Reporter put it.

Though Ms. Saldana told InStyle magazine that “I didn’t think I was right for the part,” the fallout and online petition calling for a boycott of the film nevertheless revealed a deep cultural investment in both Simone’s politics and aesthetics by a new generation.

The director Gina Prince-Bythewood said in a phone interview that she used Simone as the muse for her lead character, Noni (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), a biracial British pop sensation, in her 2014 film “Beyond the Lights” because “during her time, Nina was unapologetically black and proud of who she was, and it was reflected in the authenticity of songs like ‘Four Women.’ And this is something that Noni absolutely struggles with because she has been instructed to be a male fantasy.”

But for Ms. Prince-Bythewood, Simone is not simply an alternative to today’s image of an oversexualized or overmanufactured female artist, but the idol most suited for the multilayered identity politics of our social movements. “This moment of ‘Black Lives Matter,’ ” she said, “is a resurgence of racial pride but also a time in which black women are now at the forefront.”

Like the renaissance of interest in Malcolm X in the early 1990s, Simone’s iconography arises in yet another time of national crisis. However, her biography, as an artist who was proudly black but steadfastly rejected the musical, sexual and social conventions expected of African-American and female artists of her time, renders her a complicated pioneer.

Born Eunice Waymon in 1933, Simone grew up in segregated Tryon, N.C. At 3, she was playing her mother’s favorite gospel hymns for their church choir on piano; by 8, her talents garnered her so much attention that her mother’s white employer offered to pay for her classical music lessons for a year. Determined to become a premier classical pianist, Simone trained at Juilliard for a year, then sought and was denied admission to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia — a heartbreaking rejection that led to a series of reinventions — renaming herself Nina Simone, performing in Atlantic City nightclubs and adopting jazz standards in her repertoire.

She would go on to have her only Top 40 hit with “I Loves You, Porgy” in 1959 off her debut album, “Little Girl Blue.” To further her music career, Simone moved back to New York, where she befriended the activist-writers Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Malcolm X. Influenced by these political friendships and the momentum of the civil rights movement itself, Simone went on to compose “Mississippi Goddam” in 1964 in response to the assassination of the civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Mississippi and the murder of four African-American girls in a church bombing in Birmingham, Ala., a year earlier. The song was Simone at her best — a sly blend of the show tune, searing racial critique and apocalyptic warning.

Oh but this whole country is full of lies

You’re all gonna die and die like flies

I don’t trust you any more

You keep on saying “Go slow!”

“Go slow!”

Simone’s growing political involvement affected both her professional and personal life. Though she was bisexual, her longest romance was her 11-year turbulent marriage to Andy Stroud, a former police officer who managed her career for most of the ’60s. Stroud would use physical and sexual abuse to limit Simone’s activism and friendships, and to control her unpredictable emotional outbursts. Unfortunately, it would take another 20 years for Simone’s “mood swings” to be diagnosed as a bipolar disorder. In the interim, Simone left her marriage and country, becoming an expatriate in Liberia, Switzerland, then France. (In the film, Ms. Kelly says that because her mother became more symptomatic and abusive toward her, she had to move back in with her father.)

She had not only become more militant by aligning songs like “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” with Stokely Carmichael and the black power movement, but also found it increasingly difficult to secure contracts with American record companies. Looking back on this period in her 1991 memoir, “I Put A Spell on You,” Simone recalled, “The protest years were over not just for me but for a whole generation and in music, just like in politics, many of the greatest talents were dead or in exile and their place was filled by third-rate imitators.” She died in 2003 at her home in France.

“Nina Simone, more than anyone else, talked about using her art as a weapon against oppression, and she paid the price of it,” said Ernest Shaw, a visual artist who last year painted a mural featuring Malcolm X, James Baldwin and Simone on the wall of a Baltimore home just two miles from the scene of Freddie Gray’s arrest.

Today Simone’s multitudinous identity captures the mood of young people yearning to bring together our modern movements for racial, gender and sexual equality.

This is a large part of the appeal of the documentary “The Amazing Nina Simone,” by Jeff L. Lieberman, which features more than 50 interviews with Simone’s family, associates and academics (including me), scheduled to be released later this fall.

Mr. Lieberman said he wanted to explore the relationship between Simone and Marie-Christine Dunham Pratt, a former model and the only child of the dancer Katherine Dunham, because “many gay men and lesbians have long connected with Nina Simone because she was this outsider in her many worlds, sometimes sad, sometimes lonely, but always determined, and unrelenting in her fight for freedom.”

Still, the preoccupation with Simone has more to do with her sound than her life story. Those who have covered Simone on recent albums — including Algiers, a Southern gospel and punk band; Xiu Xiu, an experimental post-punk group; and Meshell Ndegeocello, the neo-soul, neo-funk artist — are remarkably different from one another. Their common use of Simone speaks to how her music cuts across race, gender and genre.

But it has been hip-hop, the genre that Simone once said had “ruined music, as far as I’m concerned,” that has kept her musically relevant more than anything else.

The two hip-hop artists most responsible for Simone’s current ubiquity are Kanye West and Lauryn Hill. Mr. West has rendered Simone hip-hop- and pop-friendly by sampling her in songs like “Bad News,” “New Day” and “Blood on the Leaves.” While he declined to comment on Simone, like her, he fashions himself as a controversial if not misunderstood rebel — a figure who wants to be appreciated as much for his refusal of artistic genres as for his musical virtuosity.

Ms. Hill was one of the first rappers to mention Simone in song — on the Fugees’ “Ready or Not” in 1996 — and she recorded several songs for “Nina Revisited: A Tribute to Nina Simone,” an album (due July 10) tied to “What Happened, Miss Simone?”

Jayson Jackson, Ms. Hill’s former manager and a producer of Ms. Garbus’s film, conceived “Nina Revisited,” and said that while working on the album, Ms. Hill told him, “I grew up listening to Nina Simone, so I believed everyone spoke as freely as she did.”

Paradoxically, Simone’s comeback also reveals an absence. A majority of pop artists — with the exception of a few like D’Angelo, J. Cole and Killer Mike — have largely been musically silent about police violence in Ferguson, Mo.; New York; and Baltimore.

John Legend, who covered Simone on his own 2010 protest album with the Roots, “Wake Up!,” and recently started Free America, a campaign to end mass incarceration in the United States, attributes this absence to artists unwilling or unable to take positions outside the mainstream. “I don’t think it is career suicide to take on these positions, but I think there is actually a limited number of artists who really want to say something cogent about social issues, so most do not even dive in,” he said in an interview.

He added, “To follow in her footsteps, I think it takes a degree of savvy, consciousness, communication skills, and a vibrant intellectual community that most artists aren’t encouraged to cultivate.”

Today, Simone’s sound and style have made her a compelling example of racial, sexual and gender freedom. As Angela Davis explained in the liner notes for the album, “In representing all of the women who had been silenced, in sharing her incomparable artistic genius, she was the embodiment of the revolutionary democracy we had not yet learned how to imagine.”

Salamishah Tillet is an associate professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, the author of “Sites of Slavery: Citizenship and Racial Democracy in the Post-Civil Rights Imagination” and is writing a book on Nina Simone.

Nina Simone

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nina Simone (born Eunice Kathleen Waymon; February 21, 1933 – April 21, 2003) (/ˌniːnə sɪˈmoʊn/)[1] was an American singer, songwriter, pianist, composer, arranger and civil rights activist. Her music spanned styles including classical, folk, gospel, blues, jazz, R&B, and pop.

The sixth of eight children born into a poor family in North Carolina, Simone initially aspired to be a concert pianist.[2] With the help of a few supporters in her hometown, she enrolled in the Juilliard School of Music in New York City.[3] She then applied for a scholarship to study at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where, despite a well received audition, she was denied admission,[4] which she attributed to racism. In 2003, just days before her death, the Institute awarded her an honorary degree.[5]

To make a living, Simone started playing piano at a nightclub in Atlantic City. She changed her name to "Nina Simone" to disguise herself from family members, having chosen to play "the devil's music"[4] or so-called "cocktail piano". She was told in the nightclub that she would have to sing to her own accompaniment, which effectively launched her career as a jazz vocalist.[6] She went on to record more than 40 albums between 1958 and 1974, making her debut with Little Girl Blue. She released her first hit single in the United States in 1958 with "I Loves You, Porgy".[2] Her piano playing was strongly influenced by baroque and classical music, especially Johann Sebastian Bach,[7] and accompanied expressive, jazz-like singing in her contralto voice.[8][9]

Biography

1933–1954: Early life

Simone was born on February 21, 1933, in Tryon, North Carolina. Her father, John Divine Waymon, worked as a barber and dry-cleaner as well as an entertainer, and her mother, Mary Kate Irvin, was a Methodist preacher.[10] The sixth of eight children[11] in a poor family, she began playing piano at the age of three or four; the first song she learned was "God Be With You, Till We Meet Again".[12] Demonstrating a talent with the piano, she performed at her local church. Her concert debut, a classical recital, was given when she was 12. Simone later said that during this performance, her parents, who had taken seats in the front row, were forced to move to the back of the hall to make way for white people.[13] She said that she refused to play until her parents were moved back to the front,[14][15] and that the incident contributed to her later involvement in the civil rights movement.[16] Simone's music teacher helped establish a special fund to pay for her education.[17] Subsequently, a local fund was set up to assist her continued education. With the help of this scholarship money, she was able to attend Allen High School for Girls in Asheville, North Carolina.

After her graduation, Simone spent the summer of 1950 at the Juilliard School as a student of Carl Friedberg, preparing for an audition at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.[18] Her application, however, was denied. Only 3 of 72 applicants were accepted that year,[19] but as her family had relocated to Philadelphia in the expectation of her entry to Curtis, the blow to her aspirations was particularly heavy. For the rest of her life, she suspected that her application had been denied because of racial prejudice, a charge the staff at Curtis have denied.[20] Discouraged, she took private piano lessons with Vladimir Sokoloff, a professor at Curtis, but never could re-apply. At the time the Curtis institute did not accept students over 21. She took a job as a photographer's assistant, found work as an accompanist at Arlene Smith's vocal studio, and taught piano from her home in Philadelphia.[18]

1954–1959: Early success

In order to fund her private lessons, Simone performed at the Midtown Bar & Grill on Pacific Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey, whose owner insisted that she sing as well as play the piano, which increased her income to $90 a week. In 1954, she adopted the stage name "Nina Simone". "Nina", derived from niña, was a nickname given to her by a boyfriend named Chico,[18] and "Simone" was taken from the French actress Simone Signoret, whom she had seen in the 1952 movie Casque d'Or.[21] Knowing her mother would not approve of playing "the Devil's music," she used her new stage name to remain undetected. Simone's mixture of jazz, blues, and classical music in her performances at the bar earned her a small but loyal fan base.[22]

In 1958, she befriended and married Don Ross, a beatnik who worked as a fairground barker, but quickly regretted their marriage.[23] Playing in small clubs in the same year, she recorded George Gershwin's "I Loves You, Porgy" (from Porgy and Bess), which she learned from a Billie Holiday album and performed as a favor to a friend. It became her only Billboard top 20 success in the United States, and her debut album Little Girl Blue followed in February 1959 on Bethlehem Records.[24][25][26] Because she had sold her rights outright for $3,000, Simone lost more than $1 million in royalties (notably for the 1980s re-release of her version of the jazz standard "My Baby Just Cares for Me") and never benefited financially from the album's sales.[27]

1959–1964: Burgeoning popularity

After the success of Little Girl Blue, Simone signed a contract with Colpix Records and recorded a multitude of studio and live albums. Colpix relinquished all creative control to her, including the choice of material that would be recorded, in exchange for her signing the contract with them. After the release of her live album Nina Simone at Town Hall, Simone became a favorite performer in Greenwich Village.[28] By this time, Simone performed pop music only to make money to continue her classical music studies and was indifferent about having a recording contract. She kept this attitude toward the record industry for most of her career.[29]

Simone married Andrew Stroud, a New York police detective, in December 1961. In a few years he became her manager and the father of her daughter Lisa, but later he abused Simone psychologically and physically.[4][30][31]

1964–1974: Civil Rights era

In 1964, Simone changed record distributors from Colpix, an American company, to the Dutch Philips Records, which meant a change in the content of her recordings. She had always included songs in her repertoire that drew on her African-American heritage, such as "Brown Baby" by Oscar Brown and "Zungo" by Michael Olatunji on her album Nina at the Village Gate in 1962. On her debut album for Philips, Nina Simone in Concert (1964), for the first time she addressed racial inequality in the United States in the song "Mississippi Goddam". This was her response to the June 12, 1963, murder of Medgar Evers and the September 15, 1963, bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four young black girls and partly blinded a fifth. She said that the song was "like throwing ten bullets back at them", becoming one of many other protest songs written by Simone. The song was released as a single, and it was boycotted in some[vague] southern states.[32][33] Promotional copies were smashed by a Carolina radio station and returned to Philips.[34] She later recalled how "Mississippi Goddam" was her "first civil rights song" and that the song came to her "in a rush of fury, hatred and determination". The song challenged the belief that race relations could change gradually and called for more immediate developments: "me and my people are just about due." It was a key moment in her path to Civil Rights activism.[35] "Old Jim Crow", on the same album, addressed the Jim Crow laws. After "Mississippi Goddam," a civil rights message was the norm in Simone's recordings and became part of her concerts. As her political activism rose, the rate of release of her music slowed.

Simone performed and spoke at civil rights meetings, such as at the Selma to Montgomery marches.[36] Like Malcolm X, her neighbor in Mount Vernon, New York, she supported black nationalism and advocated violent revolution rather than Martin Luther King Jr.'s non-violent approach.[37] She hoped that African Americans could use armed combat to form a separate state, though she wrote in her autobiography that she and her family regarded all races as equal.

In 1967, Simone moved from Philips to RCA Victor. She sang "Backlash Blues" written by her friend, Harlem Renaissance leader Langston Hughes, on her first RCA album, Nina Simone Sings the Blues (1967). On Silk & Soul (1967), she recorded Billy Taylor's "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free" and "Turning Point". The album 'Nuff Said! (1968) contained live recordings from the Westbury Music Fair of April 7, 1968, three days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. She dedicated the performance to him and sang "Why? (The King of Love Is Dead)," a song written by her bass player, Gene Taylor.[38] In 1969, she performed at the Harlem Cultural Festival in Harlem's Mount Morris Park. The performance was recorded and is featured in Questlove's 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.[39][40]

Simone and Weldon Irvine turned the unfinished play To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry into a civil rights song of the same name. She credited her friend Hansberry with cultivating her social and political consciousness. She performed the song live on the album Black Gold (1970). A studio recording was released as a single, and renditions of the song have been recorded by Aretha Franklin (on her 1972 album Young, Gifted and Black) and Donny Hathaway.[32] When reflecting on this period, she wrote in her autobiography, "I felt more alive then than I feel now because I was needed, and I could sing something to help my people".[41]

1974–1993: Later life

In an interview for Jet magazine, Simone stated that her controversial song "Mississippi Goddam" harmed her career. She claimed that the music industry punished her by boycotting her records.[42] Hurt and disappointed, Simone left the US in September 1970, flying to Barbados and expecting her husband and manager Stroud to communicate with her when she had to perform again. However, Stroud interpreted Simone's sudden disappearance, and the fact that she had left behind her wedding ring, as an indication of her desire for a divorce. As her manager, Stroud was in charge of Simone's income.

When Simone returned to the United States, she learned that a warrant had been issued for her arrest for unpaid taxes (allegedly unpaid as a protest against her country's involvement with the Vietnam War) and fled to Barbados to evade the authorities and prosecution.[43] Simone stayed in Barbados for quite some time and had a lengthy affair with the Prime Minister, Errol Barrow.[44][45] A close friend, singer Miriam Makeba, then persuaded her to go to Liberia.

When Simone relocated, she abandoned her daughter Lisa in Mount Vernon.[46] Lisa eventually reunited with Simone in Liberia, but, according to Lisa, her mother was physically and mentally abusive.[47] The abuse was so unbearable that Lisa became suicidal and she moved back to New York to live with her father Andrew Stroud.[46][47] Simone recorded her last album for RCA, It Is Finished, in 1974, and did not make another record until 1978, when she was persuaded to go into the recording studio by CTI Records owner Creed Taylor. The result was the album Baltimore, which, while not a commercial success, was fairly well received critically and marked a quiet artistic renaissance in Simone's recording output.[48] Her choice of material retained its eclecticism, ranging from spiritual songs to Hall & Oates' "Rich Girl". Four years later, Simone recorded Fodder on My Wings on a French label, Studio Davout.

During the 1980s, Simone performed regularly at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club in London, where she recorded the album Live at Ronnie Scott's in 1984. Although her early on-stage style could be somewhat haughty and aloof, in later years, Simone particularly seemed to enjoy engaging with her audiences sometimes, by recounting humorous anecdotes related to her career and music and by soliciting requests.[citation needed] By this time she stayed everywhere and nowhere. She lived in Liberia, Barbados and Switzerland and eventually ended up in Paris. There she regularly performed in a small jazz club called Aux Trois Mailletz for relatively small financial reward. The performances were sometimes brilliant and at other times Nina Simone gave up after fifteen minutes. Often she was too drunk to sing or play the piano properly. At other times she scolded the audience[49] Manager Raymond Gonzalez, guitarist Al Schackman and Gerrit de Bruin, a Dutch friend of hers, decided to intervene.

In 1987, Simone scored a huge European hit with the song "My Baby Just Cares for Me". Recorded by her for the first time in 1958, the song was used in a commercial for Chanel No. 5 perfume in Europe, leading to a re-release of the recording. This stormed to number 4 on the UK's NME singles chart, giving Simone a brief surge in popularity in the UK and elsewhere.[49]

In the spring of 1988, Simone moved to Nijmegen in the Netherlands. She bought an apartment next to the Belvoir Hotel with view of the Waalbrug and Ooijpolder, with the help of her friend Gerrit de Bruin, who lived with his family a few corners away and kept an eye on her. The idea was to bring Simone to Nijmegen to relax and get back on track. A daily caretaker, Jackie Hammond from London, was hired for her. She was known for her temper and outbursts of aggression. Unfortunately, the tantrums followed her to Nijmegen. Simone was diagnosed with bipolar disorder by a friend of De Bruin, who prescribed Trilafon for her. Despite the illness, it was generally a happy time for Simone in Nijmegen, where she could lead a fairly anonymous life. Only a few recognized her; most Nijmegen people did not know who she was. Slowly but surely her life started to improve, and she was even able to make money from the Chanel commercial after a legal battle. In 1991 Nina Simone exchanged Nijmegen for Amsterdam, where she lived for two years with friends and Hammond.[50][51]

1993–2003: Final years, illness and death

In 1993, Simone settled near Aix-en-Provence in southern France (Bouches-du-Rhône).[52] In the same year, her final album, A Single Woman, was released. She variously contended that she married or had a love affair with a Tunisian around this time, but that their relationship ended because, "His family didn't want him to move to France, and France didn't want him because he's a North African."[53] During a 1998 performance in Newark, she announced, "If you're going to come see me again, you've got to come to France, because I am not coming back."[54] She suffered from breast cancer for several years before she died in her sleep at her home in Carry-le-Rouet (Bouches-du-Rhône), on April 21, 2003. Her Catholic funeral service at the local parish was attended by singers Miriam Makeba and Patti LaBelle, poet Sonia Sanchez, actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, and hundreds of others. Simone's ashes were scattered in several African countries. Her daughter Lisa Celeste Stroud is an actress and singer who took the stage name Simone, and who has appeared on Broadway in Aida.[55]

Activism

Influence

Simone's consciousness on the racial and social discourse was prompted by her friendship with the playwright Lorraine Hansberry.[56] Simone stated that during her conversations with Hansberry "we never talked about men or clothes. It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution – real girls' talk."[57] The influence of Hansberry planted the seed for the provocative social commentary that became an expectation in Simone's repertoire. One of Nina's more hopeful activism anthems, "To Be Young, Gifted and Black," was written with collaborator Weldon Irvine in the years following the playwright's passing, acquiring the title of one of Hansberry's unpublished plays. Simone's social circles included notable black activists such as James Baldwin, Stokely Carmichael and Langston Hughes: the lyrics of her song "Backlash Blues" were written by Hughes.[57]

Beyond the civil rights movement

Simone's social commentary was not limited to the civil rights movement; the song "Four Women" exposed the Eurocentric appearance standards imposed on Black women in America,[58] as it explored the internalized dilemma of beauty that is experienced between four Black women with skin tones ranging from light to dark. She explains in her autobiography I Put a Spell on You that the purpose of the song was to inspire Black women to define beauty and identity for themselves without the influence of societal impositions.[59] Chardine Taylor-Stone has noted that, beyond the politics of beauty, the song also describes the stereotypical roles that many Black women have historically been restricted to: the mammy, the tragic mulatto, the sex worker, and the angry Black woman.[57]

Artistry

Simone standards

Throughout her career, Simone assembled a collection of songs that became standards in her repertoire. Some were songs that she wrote herself, while others were new arrangements of other standards, and others had been written especially for the singer. Her first hit song in America was her rendition of George Gershwin's "I Loves You, Porgy" (1958). It peaked at number 18 on the Billboard magazine Hot 100 chart.[60]

During that same period Simone recorded "My Baby Just Cares for Me," which would become her biggest success years later, in 1987, after it was featured in a 1986 Chanel No. 5 perfume commercial.[61] A music video was also created by Aardman Studios.[62] Well-known songs from her Philips albums include "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" on Broadway-Blues-Ballads (1964); "I Put a Spell on You", "Ne me quitte pas" (a rendition of a Jacques Brel song), and "Feeling Good" on I Put a Spell On You (1965); and "Lilac Wine" and "Wild Is the Wind" on Wild is the Wind (1966).[63]

"Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" and her takes on "Sinnerman" (Pastel Blues, 1965) and "Feeling Good" have remained popular in cover versions (most notably a version of the former song by The Animals), sample usage, and their use on soundtracks for various movies, television series, and video games. "Sinnerman" has been featured in the films The Crimson Pirate (1952), The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), High Crimes (2002), Cellular (2004), Déjà Vu (2006), Miami Vice (2006), Golden Door (2006), Inland Empire (2006), Harriet (2019) and Licorice Pizza (2021), as well as in TV series such as Homicide: Life on the Street (1998, "Sins of the Father"), Nash Bridges (2000, "Jackpot"), Scrubs (2001, "My Own Personal Jesus"), Boomtown (2003, "The Big Picture"), Person of Interest (2011, "Witness"), Shameless (2011, "Kidnap and Ransom"), Love/Hate (2011, "Episode 1"), Sherlock (2012, "The Reichenbach Fall"), The Blacklist (2013, "The Freelancer"), Vinyl (2016, "The Racket"), Lucifer (2017, "Favorite Son"), and The Umbrella Academy (2019, "Extra Ordinary"), and sampled by artists such as Talib Kweli (2003, "Get By"), Timbaland (2007, "Oh Timbaland"), and Flying Lotus (2012, "Until the Quiet Comes"). The song "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" was sampled by Devo Springsteen on "Misunderstood" from Common's 2007 album Finding Forever, and by little-known producers Rodnae and Mousa for the song "Don't Get It" on Lil Wayne's 2008 album Tha Carter III. "See-Line Woman" was sampled by Kanye West for "Bad News" on his album 808s & Heartbreak. The 1965 rendition of "Strange Fruit", originally recorded by Billie Holiday, was sampled by Kanye West for "Blood on the Leaves" on his album Yeezus.

Simone's years at RCA spawned many singles and album tracks that were popular, particularly in Europe. In 1968, it was "Ain't Got No, I Got Life", a medley from the musical Hair from the album 'Nuff Said! (1968) that became a surprise hit for Simone, reaching number 2 on the UK Singles Chart and introducing her to a younger audience.[64][65] In 2006, it returned to the UK Top 30 in a remixed version by Groovefinder.

The following single, a rendition of the Bee Gees' "To Love Somebody", also reached the UK Top 10 in 1969. "The House of the Rising Sun" was featured on Nina Simone Sings the Blues in 1967, but Simone had recorded the song in 1961 and it was featured on Nina at the Village Gate (1962).[66][67]

Performance style

Simone's bearing and stage presence earned her the title "the High Priestess of Soul".[68] She was a pianist, singer and performer, "separately, and simultaneously".[30] As a composer and arranger, Simone moved from gospel to blues, jazz, and folk, and to numbers with European classical styling. Besides using Bach-style counterpoint, she called upon the particular virtuosity of the 19th-century Romantic piano repertoire—Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, and others. Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis spoke highly of Simone, deeply impressed by her ability to play three-part counterpoint and incorporate it into pop songs and improvisation.[20] Onstage, she incorporated monologues and dialogues with the audience into the program, and often used silence as a musical element.[69] Throughout most of her life and recording career she was accompanied by percussionist Leopoldo Fleming and guitarist and musical director Al Schackman.[70] She was known to pay close attention to the design and acoustics of each venue, tailoring her performances to individual venues.[20]

Simone was perceived as a sometimes difficult or unpredictable performer, occasionally hectoring the audience if she felt they were disrespectful. Schackman would try to calm Simone during these episodes, performing solo until she calmed offstage and returned to finish the engagement. Her early experiences as a classical pianist had conditioned Simone to expect quiet attentive audiences, and her anger tended to flare up at nightclubs, lounges, or other locations where patrons were less attentive.[20] Schackman described her live appearances as hit or miss, either reaching heights of hypnotic brilliance or on the other hand mechanically playing a few songs and then abruptly ending concerts early.

Critical reputation

Simone is regarded as one of the most influential recording artists of 20th-century jazz, cabaret and R&B genres.[71] According to Rickey Vincent, she was a pioneering musician whose career was characterized by "fits of outrage and improvisational genius". Pointing to her composition of "Mississippi Goddam," Vincent said Simone broke the mold, having the courage as "an established black musical entertainer to break from the norms of the industry and produce direct social commentary in her music during the early 1960s".[72]

Rolling Stone wrote that "her honey-coated, slightly adenoidal cry was one of the most affecting voices of the civil rights movement," while making note of her ability to "belt barroom blues, croon cabaret and explore jazz—sometimes all on a single record".[73] In the opinion of AllMusic's Mark Deming, she was "one of the most gifted vocalists of her generation, and also one of the most eclectic".[74] Creed Taylor, who wrote the liner notes for Simone's 1978 Baltimore album, said the singer possessed a "magnificent intensity" that "turns everything—even the most simple, mundane phrase or lyric—into a radiant, poetic message".[75] Jim Fusilli, music critic for The Wall Street Journal, writes that Simone's music is still relevant today: "it didn't adhere to ephemeral trends, it isn't a relic of a bygone era; her vocal delivery and technical skills as a pianist still dazzle; and her emotional performances have a visceral impact."[76]

"She is loved or feared, adored or disliked," Maya Angelou wrote in 1970, "but few who have met her music or glimpsed her soul react with moderation."[77]

Health

Simone was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the late 1980s.[80] She was known for her temper and outbursts of aggression.[81] In 1985, Simone fired a gun at a record company executive, whom she accused of stealing royalties. Simone said she "tried to kill him" but "missed."[82] In 1995 while living in France, she shot and wounded her neighbor's son with an air gun after the boy's laughter disturbed her concentration and she perceived his response to her complaints as racial insults;[83][84] she was sentenced to eight months in jail, which was suspended pending a psychiatric evaluation and treatment.[20]

According to a biographer, Simone took medication from the mid-1960s onward, although this was supposedly only known to a small group of intimates.[85] After her death the medication was confirmed as the anti-psychotic Trilafon, which Simone's friends and caretakers sometimes surreptitiously mixed into her food when she refused to follow her treatment plan.[20] This fact was kept out of public view until 2004 when a biography, Break Down and Let It All Out, written by Sylvia Hampton and David Nathan (of her UK fan club), was published posthumously.[86] Singer-songwriter Janis Ian, a one-time friend of Simone's, related in her own autobiography, Society's Child: My Autobiography, two instances to illustrate Simone's volatility: one incident in which she forced a shoe store cashier at gunpoint to take back a pair of sandals she'd already worn; and another in which Simone demanded a royalty payment from Ian herself as an exchange for having recorded one of Ian's songs, and then ripped a pay telephone out of its wall when she was refused.[87]

Awards and recognition

Simone was the recipient of a Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 2000 for her interpretation of "I Loves You, Porgy". On Human Kindness Day 1974 in Washington, D.C., more than 10,000 people paid tribute to Simone.[88][89] Simone received two honorary degrees in music and humanities, from Amherst College and Malcolm X College.[90][91] She preferred to be called "Dr. Nina Simone" after these honors were bestowed upon her.[92] She was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018.[93]

Two days before her death, Simone learned she would be awarded an honorary degree by the Curtis Institute of Music, the music school that had refused to admit her as a student at the beginning of her career.[5]

Simone has received four career Grammy Award nominations,[94] two during her lifetime and two posthumously. In 1968, she received her first nomination for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for the track "(You'll) Go to Hell" from her thirteenth album Silk & Soul (1967). The award went to "Respect" by Aretha Franklin.

Simone garnered a second nomination in the category in 1971, for her Black Gold album, when she again lost to Franklin for "Don't Play That Song (You Lied)". Franklin would again win for her cover of Simone's "Young, Gifted and Black" two years later in the same category. In 2016, Simone posthumously received a nomination for Best Music Film for the Netflix documentary What Happened, Miss Simone? and in 2018 she received a nomination for Best Rap Song as a songwriter for Jay-Z's "The Story of O.J." from his 4:44 album which contained a sample of "Four Women" by Simone.

In 1999, Simone was given a lifetime achievement award by the Irish Music Hall of Fame, presented by Sinead O'Connor.[95]

In 2018, Simone was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[96] by fellow R&B artist Mary J. Blige.[97]

In 2019, "Mississippi Goddam" was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[98] Simone was inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame in 2021.[99]

In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Simone at No. 21 on their list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[100]

Legacy and influence

Music

Musicians who have cited Simone as important for their own musical upbringing include Elton John (who named one of his pianos after her), Madonna, Aretha Franklin, Adele, David Bowie, Patti LaBelle, Boy George, Emeli Sandé, Antony and the Johnsons, Dianne Reeves, Sade, Janis Joplin, Nick Cave, Van Morrison, Christina Aguilera, Elkie Brooks, Talib Kweli, Mos Def, Kanye West, Olivia Newton-John, Lena Horne, Bono, John Legend, Elizabeth Fraser, Cat Stevens, Anna Calvi, Cat Power, Lykke Li, Peter Gabriel, Justin Hayward, Maynard James Keenan, Cedric Bixler-Zavala, Mary J. Blige, Fantasia Barrino, Michael Gira, Angela McCluskey, Lauryn Hill, Patrice Babatunde, Alicia Keys, Alex Turner, Lana Del Rey, Hozier, Matt Bellamy, Ian MacKaye, Kerry Brothers, Jr., Krucial, Amanda Palmer, Steve Adey, and Jeff Buckley.[32][101][102][103][104][105] John Lennon cited Simone's version of "I Put a Spell on You" as a source of inspiration for the Beatles' song "Michelle".[105] American singer Meshell Ndegeocello released her own tribute album Pour une Âme Souveraine: A Dedication to Nina Simone in 2012. The following year, experimental band Xiu Xiu released a cover album, Nina. In late 2019, American rapper Wale released an album titled Wow... That's Crazy, containing a track called "Love Me Nina/Semiautomatic" which contains audio clips from Simone.

Simone's music has been featured in soundtracks of various motion pictures and video games, including La Femme Nikita (1990), Point of No Return (1993), Shallow Grave (1994), The Big Lebowski (1998), Any Given Sunday (1999), The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), Disappearing Acts (2000), Six Feet Under (2001), The Dancer Upstairs (2002), Before Sunset (2004), Cellular (2004), Inland Empire (2006), Miami Vice (2006), Sex and the City (2008), The World Unseen (2008), Revolutionary Road (2008), Home (2008), Watchmen (2009), The Saboteur (2009), Repo Men (2010), Beyond the Lights (2014), Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016), and Nobody (2021). Frequently her music is used in remixes, commercials, and TV series including "Feeling Good", which featured prominently in the Season Four Promo of Six Feet Under (2004). Simone's "Take Care of Business" is the closing theme of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (2015), Simone's cover of Janis Ian's "Stars" is played during the final moments of the season 3 finale of BoJack Horseman (2016),[106] and "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free" and "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" were included in the film Acrimony (2018).

Film

The documentary Nina Simone: La légende (The Legend) was made in the 1990s by French filmmakers and based on her autobiography I Put a Spell on You. It features live footage from different periods of her career, interviews with family, various interviews with Simone then living in the Netherlands, and while on a trip to her birthplace. A portion of footage from The Legend was taken from an earlier 26-minute biographical documentary by Peter Rodis, released in 1969 and entitled simply Nina. Her filmed 1976 performance at the Montreux Jazz Festival is available on video courtesy of Mercury Studios and is screened annually in New York City at an event called "The Rise and Fall of Nina Simone: Montreux, 1976" which is curated by Tom Blunt.[107]

Footage of Simone singing "Mississippi Goddam" for 40,000 marchers at the end of the Selma to Montgomery marches can be seen in the 1970 documentary King: A Filmed Record... Montgomery to Memphis and the 2015 Liz Garbus documentary What Happened, Miss Simone?[4]

Plans for a Simone biographical film were released at the end of 2005, to be based on Simone's autobiography I Put a Spell on You (1992) and to focus on her relationship in later life with her assistant, Clifton Henderson, who died in 2006; Simone's daughter, Lisa Simone Kelly, has since refuted the existence of a romantic relationship between Simone and Henderson on account of his homosexuality.[108] Cynthia Mort (screenwriter of Will & Grace and Roseanne), wrote the screenplay and directed the 2016 film Nina, starring Zoe Saldana, who since openly apologized for taking the controversial title role.[109][110][111][112]

In 2015, two documentary features about Simone's life and music were released. The first, directed by Liz Garbus, What Happened, Miss Simone? was produced in cooperation with Simone's estate and her daughter, who also served as the film's executive producer. The film was produced as a counterpoint to the unauthorized Cynthia Mort film (Nina, 2016), and featured previously unreleased archival footage. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2015 and was distributed by Netflix on June 26, 2015.[113] It was nominated on January 14, 2016, for a 2016 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[114]

The second documentary in 2015, The Amazing Nina Simone is an independent film written and directed by Jeff L. Lieberman, who initially consulted with Simone's daughter, Lisa before going the independent route and then worked closely with Simone's siblings, predominantly Sam Waymon.[115][116] The film debuted in cinemas in October 2015, and has since played more than 100 theaters in 10 countries.[117]

Drama

She is the subject of Nina: A Story About Me and Nina Simone, a one-woman show first performed in 2016 at the Unity Theatre, Liverpool—a "deeply personal and often searing show inspired by the singer and activist Nina Simone"[118]—and which in July 2017 ran at the Young Vic, before being scheduled to move to Edinburgh's Traverse Theatre.[119]

Books

As well as her 1992 autobiography I Put a Spell on You (1992), written with Stephen Cleary, Simone has been the subject of several books. They include Nina Simone: Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood (2002) by Richard Williams; Nina Simone: Break Down and Let It All Out (2004) by Sylvia Hampton and David Nathan; Princess Noire (2010) by Nadine Cohodas; Nina Simone (2004) by Kerry Acker; Nina Simone, Black Is the Color (2005) by Andrew Stroud; and What Happened, Miss Simone? (2016) by Alan Light.

Simone inspired a book of poetry, Me and Nina, by Monica Hand,[120] and is the focus of musician Warren Ellis's book Nina Simone's Gum (2021).[121]

Honors

In 2002, the city of Nijmegen, Netherlands, named a street after her, as "Nina Simone Street": she had lived in Nijmegen between 1988 and 1990. On August 29, 2005, the city of Nijmegen, the De Vereeniging concert hall, and more than 50 artists (among whom were Frank Boeijen, Rood Adeo, and Fay Claassen)[122] honored Simone with the tribute concert Greetings from Nijmegen.

Simone was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.[123]

In 2010, a statue in her honor was erected on Trade Street in her native Tryon, North Carolina.[124]

The promotion from the French Institute of Political Studies of Lille (Sciences Po Lille), due to obtain their master's degree in 2021, named themselves in her honor. The decision was made that this promotion was henceforth to be known as 'la promotion Nina Simone' after a vote in 2017.[125]

Simone was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018.[126]

The Proms paid a homage to Nina Simone in 2019, an event called Mississippi Goddamn was performed by The Metropole Orkest at Royal Albert Hall led by Jules Buckley. Ledisi, Lisa Fischer and Jazz Trio, LaSharVu provided vocals.[127][128]

Discography

- Acker, Kerry (2004). Nina Simone. Introduction by Betty McCollum. Philadelphia: Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-791-07456-5.

- Brun-Lambert, David (October 2006) [2006]. Nina Simone, het tragische lot van een uitzonderlijke zangeres (in Dutch). Introduction by Lisa Celeste Stroud, afterword by Gerrit de Bruin. Zwolle: Sirene. ISBN 90-5831-425-1.

- Cohodas, Nadine (2010). Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42401-4.

- Elliott, Richard (2013). Nina Simone. Icons of Pop Music. Sheffield, UK: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-845-53988-7.

- Hampton, Sylvia; Nathan, David (2004) [2004]. Nina Simone: Break Down and Let It All Out. Introduction by Lisa Celeste Stroud. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-552-0.

- Light, Alan (2016). What Happened, Miss Simone?: A Biography. New York: Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-1-101-90487-9.

- Simone, Nina; Stephen Cleary (2003) [1992]. I Put a Spell on You. Introduction by Dave Marsh (2nd ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80525-1.

- Stroud, Andy (2005). Nina Simone, "Black Is the Color...": A Book of Rare Photographs of Adolescence, Family and Early Career with Quotes in Her Own Words. Introduction by Lisa Simone Kelly. Philadelphia: Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-599-26670-1.[self-published source]

- Todd, Traci N. (2021). Nina: A Story of Nina Simone. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9781524737283.

- Williams, Richard (2002). Nina Simone: Don't Let Me Be Understood. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-841-95368-7.

Sources

External links

- Official website

- Nina Simone on Instagram

- The Amazing Nina Simone: A Documentary Film

- Nina Simone at IMDb

- Nina Simone at Curlie

- Shatz, Adam (March 10, 2016). "The Fierce Courage of Nina Simone". The New York Review of Books.

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1tffkh

THE VERY BEST OF NINA SIMONE (FULL ALBUM):

Nina Simone - 'Silk & Soul' -1967 (FULL ALBUM):

"Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues"

(Composition and lyrics by Bob Dylan (Remastered):

Nina Simone: "Why (The King of Love Is Dead)"

Why? (The King of Love Is Dead) (Live)

Nina Simone

https://www.sfcv.org/articles/feature/essential-nina-simone

The Essential Nina Simone

by Emily Wilson

People called her “the high priestess of soul” or a jazz singer, but Nina Simone said there was more folk and blues in her music than jazz. Dave Marsh, the music critic, suggested calling her a “freedom singer.” Bob Dylan said she was an artist he loved and admired, and that the fact of her recording his songs validated everything he was doing. Along with Dylan’s work, she played renditions of songs by the Animals, Leonard Cohen, and Jacque Brel. Kanye West has sampled her in his songs. Barack Obama had her song “Sinnerman” on his workout playlist. Writers Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and Langston Hughes were her close friends. She trained to be a classical pianist and Bach was her favorite composer because of his technical perfection.

Raised in Tryon, North Carolina by a mother who was a Methodist preacher and a father who did whatever work he could get during the Depression, including barber, handyman, and delivery driver, she had never been in a bar till she played at the Midtown Bar & Grill in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and when asked what she wanted to drink, she asked for a glass of milk. When Vernon Jordan, the head of the Urban League, asked her why she wasn’t more active in the Civil Rights Movement, she responded, “I am civil rights, motherfucker.”

Simone (1933 – 2003) was uncategorizable and singular, making any song she sang her own. Born Eunice Waymon, she trained to be a classical pianist and studied for a year at Juilliard but wasn’t accepted to Curtis School of Music in Philadelphia, a decision many attributed to racism. Simone was an activist during the civil rights movement, famously saying that an artist’s duty was to reflect the times. She left the United States and moved to Liberia, then to Switzerland, before finally settling in the south of France.

“Why? (The King of Love is Dead)”

Nina Simone and her band performed this song at the Westbury Music Festival on Long Island, New York, in 1968 three days after Martin Luther King was killed. They had just learned the song, which their bass player Gene Taylor wrote in response to King’s murder, and the song is enraged, heart wrenching, and catchy. Simone’s voice soars as she sings, “Turn the other cheek he’d plead/ Love thy neighbor was his creed/ Pain humiliation death he did not dread/ With his Bible by his side/ From his foes he did not hide/ It’s hard to think that this great man is dead.” The song appears on Simone’s 1968 live album, ’Nuff Said.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_Be_Young,_Gifted_and_Black

"To Be Young, Gifted and Black" is a song by Nina Simone with lyrics by Weldon Irvine. She introduced the song on August 17, 1969, to a crowd of 50,000 at the Harlem Cultural Festival, captured on broadcast video tape and released in 2021 as the documentary film Summer of Soul.[1][2] Two months later, she recorded the song as part of her concert at Philharmonic Hall, a performance that resulted in her live album Black Gold (1970). Released as a single, it peaked at number 8 on the R&B chart and number 76 on the Hot 100 in January 1970.[3] A cover version by Jamaican duo Bob and Marcia reached number 5 in the UK Singles Chart in 1970.[4]

The title of the song comes from Lorraine Hansberry's autobiographical play, To Be Young, Gifted and Black.[5][6] The song is considered an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement.[7]

Background

"To Be Young, Gifted and Black" was written in memory of Simone's late friend Lorraine Hansberry, author of the play A Raisin in the Sun, who had died in 1965 aged 34.[8][9]

Legacy

TO BE YOUNG, GIFTED AND BLACK, 1969

(Composition by Nina Simone Lyrics by Weldon Irvine):

Young, gifted and black

Oh what a lovely precious dream

To be young, gifted and black

Open your heart to what I mean

In the whole world you know

There's a million boys and girls

Who are young, gifted and black

And that's a fact

You are young, gifted and black

We must begin to tell our young

There's a world waiting for you

Yours is a quest that's just begun

When you're feeling really low

Yeah, there's a great truth that you should know

When you're young, gifted and black

Your soul's intact

How to be young, gifted and black

Oh how I long to know the truth

There are times when I look back And I am haunted by my youth

Oh but my joy of today Is that we can all be proud to say

To be young, gifted and black Is where it's at

Is where it's at

Is where it's at

#NinaSimone #ToBeYoungGiftedandBlack #BlackGold

To Be Young, Gifted And Black · Nina Simone Forever Young, Gifted And Black: Songs Of Freedom And Spirit ℗ Originally Recorded 1969. All rights reserved by BMG Music Released on: 2006-01-16

Organ, Composer, Lyricist: Weldon Irvine

Guitar: Emile Latimer

Guitar: Tom Smith

Congas: Jumma Santos

Bongos,

Drums: Don Alias

Background Vocal: The Swordsmen

Producer: Stroud Productions & Enterprises, Inc.

Mixing Engineer: Dave Swope from original 8 track masters:

To Be Young, Gifted and Black (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - October 1969):

#younggiftedblack #ninasimone

“Mississippi Goddam”:

Recording session: Live in Antibes, France July 24-25, 1965. The sixth Antibes Juan-les-Pins Jazz Festival took place from July 24 to July 29. Nina had the closing spot on the first two days.

Simone wrote this song in response to the bombing of a Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama that killed four girls and to the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi. Reportedly she sat down and wrote the song, which opens “Alabama’s got me so upset / Tennessee made me lose my rest / And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam,” in under an hour, and said it felt like firing bullets back at the Ku Klux Klan members who planted the dynamite in the church. Dick Gregory commented, “We all wanted to say it. She said it. Mississippi, God DAMN.” The song, with intense, stinging lyrics and an uptempo beat, became a famous protest song, and one that some radio stations would send back, broken in two. It was released on the 1964 album Nina Simone in Concert.

I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to be Free”

This song was an instrumental, written by jazz pianist Billy Taylor, with lyrics added later by Dick Dallas. Simone recorded it for her 1967 album Silk and Soul, and with lyrics like I wish I knew how it would feel to be free/ I wish I could break all the chains holding me/ I wish I could say all the things that I should say and I wish you could know/ What it means to be me/ Then you’d see and agree/ That every man should be free, along with Simone’s artistry, it became another song important to the Civil Rights Movement.

“Backlash Blues”

This song, included on the 1967 album Nina Simone Sings the Blues, is from a protest poem by Simone’s friend Langston Hughes. The music she wrote is more straight up blues than many of her songs, but the lyrics including, “You give me second class houses/ And second class schools/ Do you think all colored folks/ Are just second class fools?” are stirring and politically focused like many of her other songs.

I Put a Spell on You: The Autobiography of Nina Simone

In Simone’s 1991 autobiography, done with Stephen Cleary, she writes “Everything that happened to me as a child involved music.” She began piano lessons in her small North Carolina town walking two miles and crossing the railroad tracks to study with her first piano teacher, Muriel Massinovitch. At her first piano recital when she was 11, her parents were moved from their seats in the front row to the back, and she refused to play until they were back in those front row seats and could see her hands as she played.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/revolutionary-performances/

Revolutionary Performances

by Fiona I.B. Ngô

July 3, 2014

Los Angeles Review of Books

THE FIGURE of the Black Revolutionary, to a particular and change-minded audience, appeals for many reasons. The figure can represent not only who we want to be, but also what we want the nation to be. And more — if sometimes this figure carries our hopes for the future of a nation striving for social justice, sometimes the figure seems to represent the belief that social justice has already been obtained. This strange chronological versatility is important to the way our culture imagines what the Revolutionary can do: even though most actual revolutionaries responded to particular, on the ground, historical conditions, as a social figure the Black Revolutionary’s struggles seem to be continuous, existing outside of history. So, strangely, that figure can stand for our past and present, as well as our future. What this means is that the very ways in which progressive culture valorizes black revolutionaries make it difficult to understand them, as unique individuals, with specific rather than general social goals.