AS

OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN

THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON

NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/08/betty-carter-1929-1998-legendary-iconic.htm

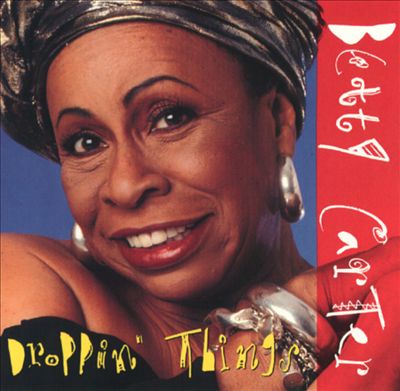

PHOTO: BETTY CARTER (1929-1998)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/betty-carter-mn0000048908/biography

Betty Carter Biography

(1929-1998)

by Steve Huey

Arguably the most adventurous female jazz singer of all time, Betty Carter was an idiosyncratic stylist and a restless improviser who pushed the limits of melody and harmony as much as any bebop horn player. The husky-voiced Carter was capable of radical, off-the-cuff reworkings of whatever she sang, abruptly changing tempos and dynamics, or rearranging the lyrics into distinctive, off-the-beat rhythmic patterns. She could solo for 20 minutes, scat at lightning speed, or drive home an emotion with wordless, bluesy moans and sighs. She wasn't quite avant-garde, but she was definitely "out." Yet as much as Carter was fascinated by pure, abstract sound, she was also a sensitive lyric interpreter when she chose, a tender and sensual ballad singer sometimes given to suggestive asides. Her wild unpredictability kept her marginalized for much of her career, and she never achieved the renown of peers like Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, or Carmen McRae. What was more, her exacting musical standards and assertive independence limited her recorded output somewhat. But Carter stuck around long enough to receive her proper due; her unwillingness to compromise eventually earned her the respect of the wider jazz audience, and many critics regarded her as perhaps the purest jazz singer active in the '80s and '90s. Additionally, Carter took an active role in developing new talent, and was a tireless advocate for the music and the freedom she found in it, right up to her death in 1998.

Betty Carter was born Lillie Mae Jones in Flint, MI, on May 16, 1930 (though some sources list 1929 instead). She grew up in Detroit, where her father worked as a church musical director, and she started studying piano at the Detroit Conservatory of Music as a child. In high school, she got hooked on bebop, and at 16 years old, she sat in with Charlie Parker during the saxophonist's Detroit gig. She won a talent contest and became a regular on the local club circuit, singing and playing piano, and also performed with the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Sarah Vaughan, and Billy Eckstine when they passed through Detroit. When Lionel Hampton came to town in 1948, he hired her as a featured vocalist. Initially billed as Lorraine Carter, she was soon dubbed "Betty Bebop" by Hampton, whose more traditional repertoire didn't always mesh with her imaginative flights of improvisation. In fact, according to legend, Hampton fired Carter seven times in two and a half years, rehiring her each time at the behest of his wife Gladys. Although the Betty Bebop nickname started out as a criticism, it stuck, and eventually Carter grew accustomed to it, enough to permanently alter her stage name.

Carter and Hampton parted ways for good in 1951, and she hit the jazz scene in New York City, singing with several different groups over the next few years. She made a few appearances at the Apollo, performing with bop legends like Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach, and cut her first album for Columbia in 1955 with pianist Ray Bryant (the aptly titled Meet Betty Carter and Ray Bryant). A 1956 session with Gigi Gryce went unissued until 1980, and in 1958 she cut two albums, I Can't Help It and Out There, that failed to attract much notice. She spent 1958 and 1959 on the road with Miles Davis, who later recommended her as a duet partner to Ray Charles. Carter signed with ABC-Paramount and recorded The Modern Sound of Betty Carter in 1960, but it wasn't until she teamed up with Charles in 1961 for the legendary duet album Ray Charles and Betty Carter that she finally caught the public's ear. A hit with critics and record buyers alike, Ray Charles and Betty Carter spawned a classic single in their sexy duet version of "Baby, It's Cold Outside," and even though the album spent years out of print, it only grew in stature as a result.

Oddly, in the wake of her breakthrough success, Carter effectively retired from music for much of the '60s in order to concentrate on raising her two sons. She did return briefly to recording in 1963 with the Atco album 'Round Midnight, which proved too challenging for critics expecting the smoothness of her work with Charles, and again in 1965 with the brief United Artists album Inside Betty Carter. Other than those efforts, Carter played only sporadic gigs around New York, and was mostly forgotten. She attempted a comeback in 1969 with the live Roulette album Finally; a second album, confusingly also titled 'Round Midnight, was released from the same concert. These two records provided the first indications of what her fully developed style sounded like, and it wasn't commercial in the least.

Unable to interest any record companies, Carter founded her own label, Bet-Car, and released her music on her own for nearly two decades. At the Village Vanguard, a live recording made in 1970, is generally acknowledged as ranking among her best; other '70s albums included The Betty Carter Album and Now It's My Turn. Carter spent most of the decade touring extensively to help make ends meet, maintaining a trio that evolved into a training ground for young jazz musicians; she preferred to hunt for and develop new talent as a way of keeping her own music fresh and vital. Over the years, her groups included musicians like pianists Jacky Terrasson, Cyrus Chestnut, Benny Green, John Hicks, Stephen Scott, and Mulgrew Miller; bassists Dave Holland, Buster Williams, Curtis Lundy, and Ira Coleman; and drummers Jack DeJohnette, Lewis Nash, Kenny Washington, and Greg Hutchinson.

Carter delivered standout performances at the Newport Jazz Festival in both 1977 and 1978, setting her on the road to a comeback. In 1979, she recorded The Audience With Betty Carter, regarded by many as her finest album and even as a landmark of vocal jazz. 1982 brought a live album with orchestra backing, Whatever Happened to Love?, and five years later, she recorded a live duets album with Carmen McRae at San Francisco's Great American Music Hall. She continued to tour as well, and when Polygram's reactivated Verve label started signing underappreciated veterans (Abbey Lincoln, Shirley Horn, Nina Simone, etc.), they gave Carter her first major-label record deal since the '60s. Verve reissued much of her Bet-Car output, giving those records far better distribution than they'd ever enjoyed, and Carter entered the studio to record a brand-new album, Look What I Got, which was released to excellent reviews in 1988. It also won Carter her first Grammy, signaling that critics and audiences alike had finally caught up to her advanced, challenging style.

Over the next few years, Carter continued to turn out acclaimed albums for Verve, winning numerous reader's polls with recordings like 1990's Droppin' Things, 1992's It's Not About the Melody, 1994's live Feed the Fire, and 1996's I'm Yours, You're Mine. Additionally, she expanded her interest in developing new jazz talent through her Jazz Ahead program, which began in 1993 and offered young musicians the chance to workshop with her at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. She also gave presentations on jazz to students of all ages, and remained an outspoken critic of the watered-down quality of much contemporary jazz. She performed at the Lincoln Center in 1993, and the following year for President Clinton at the White House; three years later, he presented her with a National Medal of Arts. Carter lost a battle with pancreatic cancer on September 26, 1998, passing away at her home in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/betty-carter/

Betty Carter

Betty Carter was born Lillie Mae Jones in Flint, Michigan, on May 16, 1930. At a young age, she began the study of piano at the Detroit Conservatory of Music, and by the time she was a teenager she was slready sitting in with Charlie Parker and other bop musicians when they performed in Detroit. After winning a local amateur contest, she turned professional at age 16, hooking up with the Lionel Hampton band by 1948, billed as Lorraine Carter. Hampton was the man who hung the nickname 'Betty Be-Bop' on her (a nickname she hated, as she found bebop limiting and wanted to do more than just scat), but it stuck, and ultimately she changed her stage name to Betty Carter. At the age of 21, she traveled to New York with the Hampton band and set up home there.

Betty spent the early 1950s as a singer with different group. She did several shows at the Apollo, playing with such notables as Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie, toured with Miles Davis in 1958 and 1959, and spent much of the rest of the time on the outskirts of the jazz scene. Her refusal to adopt a more "mainstream" jazz style led to difficulty in finding bookings and making recordings. She made her first recordings in 1955 with a then-unknown piano player named Ray Bryant. The album, Meet Betty Carter and Ray Bryant, was little received, and her second set of recordings, with the Gigi Gryce band in 1956, languished unpublished until 1980.

By 1958, she was ready to record again, and another little known album, I Can't Help It, was the result, followed closely by a recording on the Peacock label (a Texas gospel label), Out There. She was developing a reputation as a fiercely independent woman (an attitude she developed based in part on her interactions with Gladys Hampton, Lionel's no-nonsense wife) and a devoted jazz singer, and her popularity among the inner jazz circles was high, but critical and popular acclaim eluded her. She was becoming well-known for her signature style that combined off-beat interpretations of classic tunes and wild scat-singing that never seemed to find the right beat. Even a move to the ABC label for her 1960 album The Modern Sound of Betty Carter did little to help that. She needed a break, and it came in the form of Ray Charles.

Ray Charles, on a recommendation from Miles Davis, agreed to take Betty on tour with him in the late 1950s. Enchanted by her voice and looking for a partner to record a series of duets, he enlisted Ms. Carter in a project that became Ray Charles and Betty Carter. The album, recorded in 1961, became an instant critical and popular smash; the single Baby It's Cold Outside gave Betty her first introduction into the popular music scene (indeed, at the 1997 White House ceremony where President Clinton presented Ms. Carter with a National Medal of Arts, the President said, "Hearing her sing 'Baby, It's Cold Outside' makes you want to curl up in front of the fire, even in summertime."). The sessions took on almost legendary status; after fifteen years in the business, fame had found Betty Carter.

And Betty Carter chose her family. She was raising two sons at the time, Myles and Kagle Redding, and chose to concentrate on that rather than capitalize on her recent success. Other than the 1963 Atco album Round Midnight (which showcased a different side of Betty that many critics strongly disliked), and a very short 1964 United Artists album called Inside Betty Carter, she made no recordings between 1961 and 1968. She still performed, doing club dates mostly around the New York area, but the name of Betty Carter eventually faded back into obscurity again. By 1969, though, Betty was ready to get back into music. The problem was - no one seemed to want her.

She started her road back with a live recording on the Roulette album. Finally - Betty Carter (an apt title) is considered one of her finest works, but it didn't garner much interest at the time. A second live recording, again titled 'Round Midnight, met with the same fate. Unable to drum up enough interest and tired of trying to satisfy the demands of recording companies, she came up with a solution - she founded her own company. Bet-Car was founded in 1971, and would be the soul source of her recordings until she signed with Verve in 1988.

The Bet-Car years produced some of Betty's finest albums - The Betty Carter Album, Betty Carter (later rereleased as At the Village Vanguard), Now It's My Turn, and I Didn't Know What Time it Was - culminating in the December 1979 recordings that became The Audience with Betty Carter, called by some the finest vocal jazz recording ever made. Performances at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1977 and 1978 helped solidify Betty's place in the jazz world, not only as a major vocal talent but also as a discoverer of new talent (including through the years such names as John Hicks, Mulgrew Miller, Cyrus Chestnut, Mark Shim, Dave Holland, Stephen Scott and Kenny Washington).

Her Bet-Car recordings continued into the 1980s with Whatever Happened to Love? and a landmark session with fellow jazz legend Carmen McRae recorded live at a series of 1987 San Francisco dates. By 1988, finally someone took notice of her talents: Verve, on the lookout for under-appreciated jazz singers such as Abbey Lincoln and Shirley Horn, signed Ms. Carter to a contract and immediately set about rereleasing the majority of her old material.

In 1988, she burst back on to the popular jazz scene with Look What I Got, the album that earned her only Grammy award. The next decade produced several more outstanding recordings that featured a more mature sound - not reined in by any means, but perhaps softer, Betty Balladeer instead of Betty Be-Bop. She garnered Grammy nominations for 1990's Droppin' Things and 1992's It's Not About the Melody. She continued to feature young, up-and-coming musicians on most of her albums, a practice broken only on the 1994 album Feed the Fire, considered by some to be her finest work since Audience. Betty remained active in developing new musicians through the Jazz Ahead program, founded in 1993, that brought unknown jazz musicians to New York to work with her. She performed at the White House in 1994, and was a major headliner at Verve's 50th anniverary celebration in Carnegie Hall. She continued to stay active with her teaching right up until her death from pancreatic cancer on September 26, 1998.

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Betty-Carter

Carter studied piano at the Detroit Conservatory of Music in her native Michigan. At age 16 she began singing in Detroit jazz clubs, and after 1946 she worked in black bars and theatres in the Midwest, at first under the name Lorene Carter.

Influenced by the improvisational nature of bebop and inspired by vocalists Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughan, Carter strove to create a style of her own. Lionel Hampton asked Carter to join his band in 1948; however, her insistence on improvising annoyed Hampton and prompted him to fire her seven times in two and a half years. Carter left Hampton’s band for good in 1951 and performed around the country in such jazz clubs as Harlem’s Apollo Theater and the Vanguard in New York, the Showboat in Philadelphia, and Blues Alley in Washington, D.C., with such jazz artists as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Muddy Waters, T-Bone Walker, and Thelonious Monk.

Beginning in the 1970s, Carter performed on the college circuit and conducted several jazz workshops. After appearing at Carnegie Hall as part of the Newport Jazz Festival in 1977 and 1978, she went on concert tours throughout the United States and Europe. Her solo albums include Betty Carter (1953), Out There (1958), The Modern Sound of Betty Carter (1960), The Audience with Betty Carter (1979), and Look What I Got! (1988), which won a Grammy Award. Determined to encourage an interest in jazz among younger people, in April 1993 Carter initiated a program she called Jazz Ahead, an annual event at which 20 young jazz musicians spend a week training and composing with her. In 1997 she was awarded a National Medal of Arts by U.S. President Bill Clinton.

September 28, 1998

New York Times

The cause was pancreatic cancer, said her friend Ora Harris.

Ms. Carter sounded like no one in jazz, with her own diction, her own phrasing and her own sense of pitch. Though she was firmly inside the jazz-singing tradition, she was an abstractionist as well, and for her words were pliable. On her early material -- she began a solo recording career in the mid-1950's -- her light, pure voice sounded instrumental, with curved, beautifully shaped notes. It was immediately noticeable that she was after something different, and that her technique, always extraordinary, was there to work for her ideas. It was equally clear that she was a jazz musician first and a singer second.

About a decade after beginning her recording career, Ms. Carter refined her originality into a style that became the template for modern jazz singing. On ''Look No Further,'' recorded in 1964, Ms. Carter uses her voice against the bass, then as the band comes in her note choice mirrors the experimentation of instrumentalists like John Coltrane and Miles Davis; during the same session she recorded ''My Favorite Things,'' a composition associated with Mr. Coltrane. Her improvisations were explosive, tumbling out in great leaps at a velocity that expressed unfettered artistic freedom.

But it was artifice. Ms. Carter was one of jazz's most articulate small-group arrangers, and few musicians have ever controlled tempo the way she had; woe to the young musicians in the band who could not navigate the shockingly abrupt tempo changes or keep up with Ms. Carter's fastest or slowest tempos. Her snapping fingers, marking off the time, sent generations of musicians back to the practice room, chagrined.

In her hands a standard or her own compositions often contrasted some of jazz's slowest tempos with some of its fastest. She wasn't afraid to pare down the instrumentation of a group for a while, singing against piano or bass, orchestrating the arrival of other instruments. And the constant tempo-changing gave the impression of emotional extremity and careful control of the artistic environment. She sculptured sound, and it made her concerts some of the most moving experiences in jazz, a mixture of the emotional power of the songs' texts and the sheer joy of her imagination.

''I started to change my material to keep the musicians interested,'' Ms. Carter said in a 1992 interview with The New York Times. ''What do you do with a chorus and a half? You change things, stretch them out, change speed. Most musicians I played with were so good they could do what was necessary.''

Ms. Carter grew up in Detroit, which in the 1940's and 1950's was a good environment for jazz musicians, with the city producing some of the best musicians of the time.

Detroit was a stop on the jazz circuit, and a young Ms. Carter sang with Charlie Parker, who came through town. One of her nicknames was Betty Bebop, a tribute to her interests. In 1948 she began working with Lionel Hampton and his band, staying with the vibraphonist until 1951, when, during a performance in New York, she decided to remain there. During the same time she recorded the female part for King Pleasure's version of ''Red Top,'' singing a vocal rendition of Gail Brockman's original trumpet solo.

In New York in 1955 and '56, Ms. Carter began recording for Epic Records and generally taking in the city. In 1957, she recorded with Wynton Kelly and other peers; her work was irregular partly because her style was more jazz than cabaret, and partly because she tried to avoid the abusive working situations that have plagued jazz.

In 1961 Ms. Carter recorded what has become a classic album, ''Ray Charles and Betty Carter,'' with Mr. Charles; it features the pair singing astringent duets including a famous version of ''Baby, It's Cold Outside.'' Ms. Carter worked with Mr. Charles from 1960 to 1963, the year she toured Japan with Sonny Rollins and recorded an orchestral album for Atco Records.

Through the 1960's Ms. Carter struggled with her career, recording with Roulette Records in the late 1960's, during which the avant-garde and pop music rendered some artists identified with an older style commercially irrelevant. But in 1969 she started her own recording company, Bet-Car Productions, and on that label she released her albums.

In 1988 Ms. Carter began a relationship with Verve Records that included the reissue of the Bet-Car label along with the recording of a series of new albums. That same year she released ''Look What I Got!,'' which won a Grammy, and in 1994 she recorded an album, ''Feed the Fire,'' with the pianist Geri Allen, the bassist Dave Holland and the drummer Jack DeJohnette.

Also during the 1980's Ms. Carter, finally recognized for her innovations, became a concert draw internationally. She recorded duets with Carmen McRae, and she kept turning out well-rounded musicians, having trained them in her trio. Included in the alumni from the 1980's and the 1990's were the pianists Cyrus Chestnut, Benny Green, Stephen Scott, Marc Cary, Darrell Grant and Travis Shook. And her choice of drummers was extraordinary, having hired Greg Hutchinson, Clarence Penn, Winard Harper, Troy Davis and Lewis Nash. She began receiving numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts given last year by President Clinton.

In 1993 she began the Jazz Ahead series at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a program that featured young and promising musicians. This year the Jazz Ahead series was invited to appear at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington.

Ms. Carter is survived by two sons, Myles and Kagle Redding, both of New York City. A marriage to James Redding ended in divorce.

''The survival of jazz culture takes priority,'' Ms. Carter said in the interview with The Times. ''The survival of this culture depends on people playing it and living the life. The young guys playing it in 20 years will be taking the music somewhere else. There was a period where, in jazz, the music sent people away. But it's now back to making people feel better, putting happy smiles on their faces. When I was coming up, that's what jazz was about. It wasn't about money. It was about how happy you could make people.''

Photo: Betty Carter refined a style with unusual diction, pitch and phrasing that became the template for modern jazz singing. (Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times, 1973)

http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1998-10-04/features/1998277124_1_betty-carter-jazz-carter-died

A fond farewell note to a pure jazz singer Betty Carter never compromised, and jazz is poorer for her passing.

by J.D. Considine

SUN POP MUSIC CRITIC

When Betty Carter died last Saturday at age 68 of pancreatic cancer, jazz lost more than just a great vocalist. It lost some of the essence of jazz singing itself.

It's not a loss the average listener is likely to notice, sad to say, for Carter never achieved the sort of fame enjoyed by Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughan or Nancy Wilson. Indeed, there were many outside the jazz world who never heard her, or even heard of her.

Those others, after all, managed to cross over into the world of pop, occasionally even cracking the Top 40. Fitzgerald was famous enough to do TV commercials, and even listeners born years after the Big Band era knew the likes of "A-Tisket, A-Tasket."

Betty Carter, by contrast, was a jazz singer through and through. "There's really only one jazz singer - only one," Carmen McRae once said. "Betty Carter." But even as the depth of her talents earned her the respect of her peers, it did little to attract a wider audience.

That's not to say Carter toiled in obscurity. In 1961, Ray Charles invited her to join him on his first release for ABC-Paramount. "Ray Charles and Betty Carter" (recently reissued by Rhino) may not have been the most popular of Charles' albums, but the collection of coy duets did well enough, even generating a minor hit with "Baby, It's Cold Outside."

After she won a jazz Grammy in 1988 for the album "Look What I Got!", Carter made it onto TV and into the pages of Rolling Stone. She even did a few appearances on "The Bill Cosby Show," ensuring that average Americans at least saw her.

Pop, though, was not Carter's milieu. Lionel Hampton summed up her sound and attitude when he dubbed her "Betty Bebop," a nickname that reflected both the fluid agility of her vocal improvisations and the uncompromising seriousness of her aesthetic.

Born Lillie Mae Jones on May 16, 1930, in Flint, Mich., Carter studied piano at the Detroit Conservatory and was a professional singer by the age of 16. She sat in with touring be-bop musicians (including Charlie Parker) as they came through Detroit and within two years had developed enough polish and potential to earn a job with Hampton's band. Over the next few decades, she would work with such luminaries as Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins and eventually ended up leading a quartet of her own.

In later years, Carter became known as a connoisseur of up-and-coming talent, and over the years she worked with some awesomely talented young pianists. Among the alumni of her group are such now-famous names as Cyrus Chestnut, John Hicks, Mulgrew Miller, Jacky Terrasson, Benny Green, Onaje Alan Gumbs and Stephen Scott.

Despite her sterling reputation among jazz musicians, Carter was considered almost completely uncommercial by record companies and was without a recording contract for over a decade and a half. Undaunted, she formed her own label, Bet-Car, in 1971 and released a handful of critically acclaimed (though commercially negligible) albums before finally being signed by Verve in 1987.

Although Carter made plenty of studio recordings over the years, her best work was usually done before live audiences. As she once said, "An audience makes me think, makes me reach for things I'd never try in the studio." Perhaps that explains why her most lauded album was titled "Audience with Betty Carter" (a 1979 Bet-Car release, now available on Verve), punningly pointing out the almost collaborative nature of her concert performances.

For one thing, Carter was never one to hide her feelings behind a facade of professionalism. Blessed with a quick, puckish wit, she loved to lampoon the inanity of pop lyrics. She also had a legendary temper and would lambaste band members - or even members of the audience - if their behavior rubbed her the wrong way.

But the biggest reason her live recordings had more vitality than her studio work was that Carter was an improviser above all else, and as such loved the spontaneity and unpredictability of a concert crowd.

Of course, merely calling her an "improviser" doesn't quite seem appropriate. Sure, Carter could scat-sing better than almost anyone, and her wordless solos boasted a fluidity and luster any saxophonist would envy.

Carter's improvisational approach didn't end there, though. Unlike other jazz singers, who would offer a fairly straight rendition of the melody and chorus before heading off for parts unknown with the solo, Carter would impose herself on the whole of the song.

She loved to twist the words of a song around, either to amplify their emotional significance or mock their banality, and would sometimes take such liberties with the notes in the verse and chorus that the original tune would be rendered almost unrecognizable. Not for nothing did she call a 1992 album "It's Not About the Melody."

It was this total reinterpretation of words and music that led many to insist that Carter was the only true jazz singer around. And now that she's gone, it's hard to imagine who will fill that role.

There are still jazz singers whose interpretive sense is as individual and improvisatory as Carter's. Sheila Jordan, for example, will take as many chances in her performances as Carter did, while Ethel Ennis can be just as sly and insightful. Unfortunately, neither records or tours with any frequency.

Of the younger generation, Cassandra Wilson has done much to extend Carter's aesthetic beyond the boundaries of be-bop. But her recent recordings draw from such a broad range of sources that some critics have hesitated to consider her music jazz. That's a shame, because such a judgment discounts the singularity of what Wilson does. It also ignores the fact that the main thing that made Betty Carter special wasn't that she sang jazz, but that nobody else sang it like her.

To hear examples of Betty Carter's music, call Sundial at 410-783-1800 and enter the code 6146. For other local Sundial numbers, see the directory on Page 2B.

NPR's 'Jazz Profiles'

Betty Carter: Fiercely Individual

In the late '80s, Betty Carter achieved sustained recognition upon signing to a major label, which also reissued much of her back catalog.

For nearly 50 years, Betty Carter was an irrepressible and incomparable practitioner of the jazz vocal tradition, with an intense, adventurous style and a booming voice. The fiercely dedicated and demanding vocalist was a pioneer in the music business, paving the route for scores of younger musicians.

Carter was born in a strict Baptist household in Detroit, a city with a rich jazz community. She began singing in her high-school choir, and was later exposed to bebop, a style just emerging in her teenage years. She loved it instantly, and while still in her teens, she had the opportunity to sing with bebop pioneers Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker.

Her first big break came when she joined drummer Lionel Hampton's big band, a gig she held for two and a half years. Their relationship was always rocky, though, and Carter was fired numerous times. But with the help of Hampton's wife, Gladys, they always managed to get back together. "Any time that Hamp and I got into it, [Gladys] was always backing me up and making sure that I didn't leave the band too early," Carter says. "She wanted me to wait and get some experience and then leave the band."

After leaving Hampton's band in the early '50s, Carter headed to New York, where she was determined to make a name for herself. "It was very important in those days for a musician or a singer to become an individual," Carter says. "You had to be yourself if you were going to succeed." Throughout the 1950s, Carter created her own musical identity through her singing, composing and arranging.

In 1961, she was asked to record with singer Ray Charles. Their version of "Baby, It's Cold Outside" took the country by storm and made Charles a household name. During the early '60s, Carter also married and had two sons.

However, as the '60s progressed, Carter struggled with managers and record companies and developed a reputation as troublesome. So in 1969, she started her own record label, Bet-Car Productions, and by 1970 she released her first album. She began hiring and mentoring young musicians — a service some have called The University of Betty Carter. Playing in her band offered on-the-job training to drummers Clarence Penn and Lewis Nash, pianists Cyrus Chestnut and Benny Green, and bassists Chris Thomas, Michael Bowie and Curtis Lundy, among others.

During the '80s, Carter's album Look What I Got became the first independently produced jazz album to win a Grammy, and she collaborated with vocalist Carmen McRae and pianist Geri Allen. Late in her career, Carter also conducted an annual writing and performance workshop for budding young musicians all over the country.

Betty Carter continued touring, mentoring and recording until her death of pancreatic cancer in 1998.

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/betty-carter-remembered-betty-carter-by-dee-dee-mcneil.php

Betty Carter Remembered

May 13, 2006

“I finally got with a major record company that offered to give me some money and let me keep my integrity. You know, I would record for a record company for no money, if I could just keep my integrity and do what I wanna do."

In her hotel suite that morning, Carter had on a silky, lounge outfit and no make-up. When asked how it feels to be a vocal legend who weathered the musical storm from the be-bop era into the age of fusion jazz and what makes her approach so unique, a feisty Carter replied, "I don't see me like you see me. I've been doing this so long that it's natural for me. I thought it was okay to learn new music; learn how to write and to arrange your own stuff. It took a long time to realize that a lot of singers have other people doing their arrangements. But I wanted to do my own. So that meant I had to learn about the music. ...I did that when I was with Lionel Hampton.

Born May 16, 1929, this month would have been Betty Carters' 77th birthday. By the time she was a teenager, Lillie Mae Jones knew she wanted to be a professional jazz singer. A determined young woman, she was smart enough to make herself known to all the big-name jazz musicians who passed through Detroit. Even before she became Betty Carter, at sweet sixteen Lillie Mae sat in with Charlie Parker. Later, Lionel Hampton offered the young talent a job singing with his band. She was barely eighteen years old, but Lillie Mae didn't hesitate. It was Lionel Hampton who nick-named her "Betty Be Bop. Before that, she was billed as Lorraine Carter. That Betty Be Bop nickname stuck!

During her tenure with Hamp's band, a raw, inexperienced Betty Carter shared the stage with another fledgling singer. He too was destined for longevity and fame. It was none other than Little Jimmy Scott. Also in the band were two musicians who would later become giants in their own right; Charles Mingus and Wes Montgomery. Betty made only one recording with Lionel Hampton's band. It was a vocal version of "The Hucklebuck. Although she was not immediately embraced by the record-buying public, Carter made a positive impression on inner circle jazz musicians. When she recorded Red Top with King Pleasure, she surprised audiences by singing Gail Brockman's trumpet solo. Not only did it become one of her signature songs, it cast her "Be Bop title in stone. Even then, Betty's style and approach defied definition. She refused to be pigeon-holed into a category. This was evident when she was headlining at the Apollo twice a year from 1949 to 1965.

Carter would appear on the line-up at the Apollo with a diversity of musical names. Miles, Monk, Moody, Moms Mabley and me, Carter reminisced. "That was one show. Another show I did was John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee and Bo Diddley. All right! Is that a show for you? I did one with the Isley Brothers. The Flamingos. Now this is the variety that they have been able to put me on with through the years. So nobody could tell me that my thing wasn't going!

I couldn't do anything else if I wanted to, Carter continued emphatically. "I couldn't sing like Aretha Franklin. It's just not my bag. I was doing nothing but me. I think everybody's strong and survives in being themselves. I think that's what you were supposed to do in the first place. I think that's what 'the man' put you here for, to be yourself. You're an individual. He made everyone of us different!

And different she was! There are few voices that demand the respect and attention of Betty Carter's unique jazz style and phrasing. Carter's harmonics were fascinating, as was the way she could go outside boundaries of melody and time, yet always making it work.

In May of 1955, Betty Carter recorded with the Ray Bryant trio. The next recording came with Gigi Gryce's band in 1956. Unfortunately, this recording effort sat on some dusty shelf until it was released in 1980.

During the interview, an outspoken Batty Carter expressed anger about the avant-garde jazz of the day. As a product of Hampton's big band fame, she missed ballroom days, swing dancing and times when people enjoyed singing lyrics along with the music. Betty Carter didn't mince words!

"It's pathetic, Carter said, at this point, how much we don't know about our own craft. We did it to ourselves. A lot of our musicians did it to themselves. In the '60s, they became panicky. Coltrane came along, so everybody starts to play free. They didn't realize that is not black culture. The moment they did that, they alienated blacks. Whites began to absorb that free stuff, because they're classically trained. They know about dissonance. That's their culture. Blacks run from it, because none of our music would swing anymore. They were talkin' about this is the new music and I was scared to death!

View All123Next

Singer

Tuned in to Bebop

Toured With Lionel Hampton

Paid Dues in New York City

Recorded With Ray Charles

Changing Times for Jazz

Discovered by a New Audience

Thrived on Musicians’ Suggestions

Named “Jazz Legend”

Selected discography

“I don’t hear anybody out there now who really scares me, who makes me think, ‘Betty, you got to push a little harder,’” Betty Carter once told the Daily News Magazine. “So many of the good ones straddle the line between jazz and commercial. They think they can do both. But when I see someone straddling, I know I got nothin’ to worry about.”

“Straddling” has no place in Carter’s aesthetic. While many of her contemporaries went the commercial route over the years, striving for the money and fame that a hit record might bring, Carter stuck to what she set out to do as a teenager—sing jazz, her way. In the end her perseverance and talent paid off. Though she’s self-taught and considers herself not a “true” singer, she’s earned a place alongside such jazz divas as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sarah Vaughan. In jazz, after all, what matters is not so much training and technique as originality—which she has plenty of.

As noted in the New York Post, she’s a “singer who can take a standard and—without relying on facile ‘shoo-be-doo-be’ scat—reinvent it on the spot by reharmonizing the melody, changing the emphasis of the lyrics, and toying with the tempo and rhythm.” (Older-generation critics have accused her of losing the theme in the complexity of her interpretations; younger ones are usually floored by her inventions.) Each time she performs, whether standards or originals, she seems to stretch the concept of improvisation to a new limit. She’s known for taking ballads at tempos that are impossibly and mesmerizingly slow. Then there’s her inimitable contralto—deep, sensuous, and husky. And she has a character whose strength underlies the power of her voice. Throughout her four-decade-plus career she’s done things her way from start to finish, even though it meant struggling for many years. “A lot of people don’t like dealing with an independent black female, who takes care of her own business and holds her head high,” she told AP writer Mary Campbell. “But I’ve never thought about quitting. I’ve been discouraged maybe but something would always happen to make you think you’d be a star in the next six months.”

Tuned in to Bebop

For the Record…

Born Lillie Mae Jones, May 16, 1929, in Flint, MI; children: two sons.

Studied piano as a teenager at the Detroit Conservatory of Music; won a talent show at Detroit’s Paradise Theater, 1946; while still in high school, sat in on gigs with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and other bebop musicians visiting Detroit. Toured with Lionel Hampton’s band, 1948-51, Miles Davis, 1960, and Ray Charles, 1960-63; performed in Japan, 1963, London, 1964, and France, 1968. In 1969, began to work with her own trio and founded her own record company, Bet-Car Productions. In 1975, appeared in Howard Moore’s musical Don’t Call Me Man. Continues to perform and record with her trio.

Awards: Earned Grammy nominations for the albums The Audience With Betty Carter, Whatever Happened to Love?, and Look What I Got! In 1981, Bet-Car Productions won an Indy Award as the nation’s best independent label.

Addresses: Home— Brooklyn, New York. Media information— Polygram Classics, 810 Seventh Ave., New York, NY 10019.

We would gather across the street from my high school and listen to the jukebox, which was filled with bebop singles,” she told Pulse! “We would sit around and learn the solos, and go to see them whenever they came to town—we met Bird and Dizzy when they came to our school.” Soon she was singing Sunday afternoon cabaret gigs; by the age of 18 she had sat in with Bird, Dizzy, trumpeter Miles Davis, and other greats. Her first employer, though, was not a bebopper but a veteran of swing music—the vibraphonist and bandleader Lionel Hampton. In a 1988 interview with AP writer Campbell, Carter recounted their first meeting: “I went with some classmates to hear Lionel’s band. We were standing in front of the bandstand. A guy said, ‘Why don’t you let Lillie Mae sing?’ That was my name then. He said, ‘Can you sing, Gates?’ I said yes. He said, Then come on up, Gates.’”

Toured With Lionel Hampton

The impromptu audition landed her a job. From 1948 to 1951 she toured with Hampton, standing in front of his big band and scatting (improvising with nonsense syllables) segments of the tunes they played. “I didn’t get a chance to sing too many songs because Hamp had a lot of other singers at the same time; but I took care of the bebop division, you might say,” she told Pulse! with a chuckle. “He’d stick me into songs they were already doing, so I was singing a chorus here, a chorus there; I didn’t realize at the time what good training that was. And I had the late Bobby Plater teach me to orchestrate and transpose, which I really needed later on.” While she was learning from Hampton she was also learning from his wife. “I had this role model of Gladys Hampton to emulate. She took care of the band, saw to it that everything ran smoothly, that everybody got paid and such. That was the first time I’d ever experienced dealing with a woman who was the boss—and she was a black woman. It was very unusual at that time, and still is.”

Lorraine Carter, as the young singer had begun calling herself, made quite a stir at New York’s Apollo Theater. Jack Schiffman, son of the late Apollo owner Frank Schiffman, recalled his impressions for the Daily News Magazine: “Lionel Hampton introduced a small girl, hair bobbed short, eyes seemingly larger than her face, who burst out on stage, took a deep breath, and sang bebop riffs, a whole machine-gun load of them that turned the house upside down. I never saw an audience turned on so quickly to a new sound.” Hampton began calling her Betty Bebop (which evolved into Betty Carter). But the relationship between the two was a stormy one; Hampton allegedly fired her half a dozen times for mouthing off to him. “I wanted to be with a hipper band—the guys playing bebop, not swing,” Carter told Polygram. “But in retrospect I was right where I needed to be.” She elaborated in the Daily News Magazine, “I couldn’t see the advantage of his making me go out there and improvise every night. But without that training, I might not know how to be spontaneous now.” “And suppose I had been with Dizzy’s band,” she told Pulse!, “The things that were going on there”—the use of heroin among the musicians—“were things I didn’t need to come in contact with. But I didn’t know that then.”

Paid Dues in New York City

In 1952, after two and a half years of “doing what Hamp wanted me to,” as she told AP writer Campbell, “I struck out to find out what more I could do with myself. I came to New York and got work right away at the Apollo Bar, a couple of doors from the Apollo Theater.” Thus began a grueling period of dues-paying. “I did the usual, playing dives and joints, wherever I could,” she told Pulse! “There were a lot of places around to do the hustling then…. Besides all the clubs that were in New York, we had Philadelphia to work with, and Boston, and Washington, D.C.; all up and down the East Coast there were lots of places to work. And Detroit was still good then, and Chicago.” It was a golden time of opportunity. “There was a big, beautiful music world for us in the ’50s,” she told the Daily News Magazine. “We played and learned together, because we all loved music and musicianship. It wasn’t about money—we weren’t making any of that—it was about a whole community. No one had to dominate. We liked each other. I’d hang around clubs with Sarah Vaughan or Ruth Brown. I played on bills with Sonny Til and the Orioles, the Temptations, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Miles Davis. It didn’t matter what you did; you just had to be good at it. At the Apollo, you could play classical music if you did it well…. Someone should write a book about those days. There was such joy. We thought that world would never end.”

Recorded With Ray Charles

Carter’s hard work led to a theater tour with Miles Davis, which led to a tour with the famed gospel pianist and singer Ray Charles. In the midst of the latter, Charles asked Carter to do a record with him. “He asked me in Baltimore, in the hallway by the dressing rooms,” she recalled in Pulse! “After he asked me, it got silent; I mean, he had ‘Georgia’ going, a bi-iii-ig hit record; he didn’t need me.… I went to his house to work on the tunes, and then went back to the hotel numb because I was really gonna do it. I learned the tunes by thinking about it more than practicing them; we didn’t go over anything more than one time, because I was capable of understanding everything he said to me about what to do and how to do it.” The result was the 1961 classic Ray Charles and Betty Carter, which has been reissued by Dunhill on CD. “It was the one thing that kept my name out in front of people, because I didn’t have any records of my own.”

Changing Times for Jazz

During the sixties jazz got undercut by rock music, and the industry pressured jazz musicians to commercialize. As Carter told the Daily News Magazine, “the business became about money. Lots of money. And when some jazz players see that, they want some of it. Instead of $500 a night, they think they can make $4,000 in the commercial world. And some do, for a while. But the commercial world is a trap. You have one hit, they want number two, and number three. If you don’t get it, they drop you.” Carter stuck by her own bebop-rooted music and tried to convince her peers to do the same. But as she told Pulse!, “nobody in jazz paid me any attention because I was female and a singer. Had it been a male who said what I said, we might have made a dent—the way [trumpeter] Wynton Marsalis is making a dent now, saying a lot of the things that I said a long time ago. I think we might have stopped a lot of jazz artists from switching to commercial stuff.”

Refusing to change her style, Carter found herself shut out by record labels. “What do you do after you’ve tried to sell yourself and nobody wants to buy? That hurts, it really does. Anyway, I decided if I was ever going to record again I should do it myself.” In 1969 she founded her own label, Bet-Car Productions, and, along with a female business partner, assumed control of not only the recording and producing but also the financing, manufacturing, and distribution ends of the business. “I had to do everything myself only because I could not be controlled,” she told Jam Sessions. “I could not be produced by somebody else, telling me what to do; telling me how to be, how to think and how to move.”

Discovered by a New Audience

As Carter recorded for Bet-Car in the 1970s and continued to perform, her audience grew. But as she told the New York Post, “I realized I was bottling up my musicianship, trying to accommodate, trying not to be too extreme. Because a lot of my peers were talking about, ‘Why don’t you stop doing the bebop? … Why don’t you get a hit record?’ But why should I deal with something that was making me feel bad? … I decided to just stick with my music, to try to improve it, and suddenly I started going to colleges and discovered that there was a whole new audience. And the more interesting it got, the more the audience liked it.”

It seems appropriate that Carter began playing colleges, as she has always been an educator of jazz music. As Cash Box observed, she has been “one of the most eloquent drum-beaters for jazz. She sits on panels, she makes speeches, she has been very vocal in her opinion about what is jazz, what isn’t jazz, and what’s happening in this art form.” What motivates her, as she told Cash Box, is her own “black culture. I want to make these young kids realize that it was the black people who started this wonderful music of jazz, and not Dave Brubeck.” Since the 1970s, her most powerful tool as an educator has been to perform with young sidepeople, often kids straight out of college. “There’s something about having young people play for young people that makes a better impact than, say, five old men,” she told Mother Jones. “So it’s three young musicians and this old person, Grandma, if you want to say, and we get on stage and we work together. The energy is there, the enthusiasm, the fun, the charisma—everything that youth wants. See, without that, there’s no way I can compete with the hip-hoppers.”

Thrived on Musicians’ Suggestions

Carter’s band members receive an education of their own. Drummer Kenny Washington, who played with Carter from 1978 to 1980, told the Christian Science Monitor that “you have to watch Betty all the time. She has it completely in her mind what she wants. But she doesn’t say you do it my way or not at all. She thrives on suggestions. She wants you to speak what you feel and think. The minute you don’t have any ideas and suggestions, you’re gone.” Carter probably wouldn’t deny that. “I want my musicians to think all the time,” she told the Daily News Magazine, “If somebody plays the same thing 10, 12 times, I’ll say, ‘Hey, I’m tired of that. What else you got?’ The other day I gave my drummer some 7/4. He’d never played it before. It’ll give him new tools…. When I improvise, I don’t want a note. I want the note. My piano player is 18. Eighteen. And he knows how to get the note. My bass player sometimes hits a note. But he’ll get it together. I may be the only musician today who’ll tell somebody if I hear a mistake. That’s the way it used to be. You told the truth and no one’s feelings were hurt, because you did it in a positive way. You see potential, you help develop it.”

Named “Jazz Legend”

In 1988, after nearly two decades of running her own label, Carter signed a deal with Polygram’s Verve for both new recordings and reissues of Bet-Car titles. Look What I Got!, her first release on Verve, topped Billboard’s jazz chart and earned her a Grammy nomination. Her latest release is 1990’s Droppin’ Things. She continues to play both the club and college circuits. In the spring of 1991, having been named “Jazz Legend” by the Southern Arts Federation, she lectured and performed at 11 southeastern colleges.

“There’s no describing the joy of getting up on stage and doing your thing and having an audience respond to it,” Carter told the Boston Globe Magazine. “No one has told you what to do. You haven’t been produced by anybody. You’re on stage because you have talent and you know what to do. And you do it, and the audience is out of their heads. That’s what jazz allows you to do. It’s the only art form that allows you to do that. Most commercial art forms are produced. Popular music is produced by someone who tells some kid how to sing the song. Not jazz. You’re free. That’s the difference.”

Selected discography:

The Betty Carter Album, Verve, originally released 1976.

The Audience With Betty Carter, Verve, 1981.

Look What I Got!, Verve, 1988.

Ray Charles and Betty Carter, Dunhill, 1988.

The Carmen McRae-Betty Carter Album, Great American Music Hall Records/Fantasy, 1988.

Whatever Happened to Love?, Verve, 1989.

Droppin’ Things, Verve, 1990.

Sources:

Boston Globe, August 21, 1988.

Cash Box, February 13, 1988.

Christian Science Monitor, October 6, 1988.

Daily News Magazine, January 24, 1988.

Jam Sessions, March 1988.

“Jazz South” (newsletter of the Southern Arts Federation), Spring 1990.

London Times, 1985.

Mother Jones, January/February 1991.

Nation, July 30/August 6, 1988.

New York Post, January 26, 1988.

Polygram Jazz publicity biography, 1990.

Pulse!, August 1988.

Betty Carter Live at The Montreal Jazz Festival 1982- (full concert)

Betty Carter (vocal) Khalid Moss (piano) Curtis Lundy (bass) Lewis Nash (drums);

The Incredible Betty Carter Live at the Montreal Jazz Festival (1982):

Setlist:

1 - Jabbos revenge (instrumental)

2 - What's new

3 - What a little moonlight can do to you

4 - Social call

5 - Goodbye

6 - With no words

7 - Don't weep for the lady

8 - Tight

9 - Every time we say goodbye

10 - Favourite things

11 - We tried

12 - Show less

VIDEO: Tight & Tighter - Betty Carter with Branford Marsalis > YouTube

https://kalamu.posthaven.com/video-tight-tighter-betty-carter-with-branford

Betty Carter on 'Night Music Show' (NBC) 1989 - "Tight" (with Branford Marsalis):

Betty Carter - Tonight Show 1992:

Betty Carter Live at The Hamburg Jazz Festival 1993. (Full Concert):

Betty Carter Live at The Hamburg Jazz Festival, October 1993 with Geri Allen on piano, Dave Holland on Bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums.

The Audience With Betty Carter

#BettyCarter

1/15 videos:

"Sounds (Movin On)" (Live At Bradshaw's Great American Music Hall, San Francisco/1979):

Betty Carter - Medley: "This Is Always/Open The Door" (1964):

Betty Carter (born Lillie Mae Jones, May 16, 1929 – September 26, 1998) was an American jazz singer known for her improvisational technique, scatting and other complex musical abilities that demonstrated her vocal talent and imaginative interpretation of lyrics and melodies

Carmen McRae once stated " There is really only one jazz singer, Betty Carter." Taken from my personal collection the original 1964 LP "Inside Better Carter" (1993 Re-Issue). All rights to Blue Note Records, Capitol Records, and EMI. Remember listen in HD.

Betty Carter - "Spring Can Really Hang You up the Most”

Inside Betty Carter | ©1965 United Artists:

Ray Charles With Betty Carter -

"Baby It's Cold Outside" (1961):

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xx9qox_ray-charles-with-betty-carter-baby-it-s-cold-outside-1961_music

From the album Ray Charles - "Ray Charles And Betty Carter:

Betty Carter & Dave Holland - "All or Nothing at All"

Song list: 1) Feed the Fire; 2) Love Notes; 3) Sometimes I'm Happy; 4) Fake; 5) Lullaby of the Leaves; 6) Trio tune (Comp. G. Allen); 7) Stardust (duet w/piano); 8) All or Nothing at All (duet w/bass); 9) The Drum Thing (duet w/drums); 10) Long Ago and Far Away; 11) Giant Steps; 12) Day Dream; 13) B's Blues

"The Man I Love" - Betty Carter:

Betty Carter "Look What I Got!" (1988) Benny Green – piano Curtis Lundy – double bass Lewis Nash – drums, guitar Don Braden - tenor saxophone:

Early Betty Carter 1950 1961

Betty Carter (born Lillie Mae Jones; May 16, 1929 – September 26, 1998) was an American jazz singer known for her improvisational technique, scatting and other complex musical abilities that demonstrated her vocal talent and imaginative interpretation of lyrics and melodies.[1] Vocalist Carmen McRae once remarked: "There's really only one jazz singer—only one: Betty Carter."[2]: xiv [3]

Early life

Carter was born in Flint, Michigan, and grew up in Detroit, where her father, James Jones, was the musical director of a Detroit church and her mother, Bessie, was a housewife. As a child, Carter was raised to be extremely independent and to not expect nurturing from her family. Even 30 years after leaving home, Carter was still very aware of and affected by the home life she was raised in, and was quoted saying:

I have been far removed from my immediate family. There's been no real contact or phone calls home every week to find out how everybody is…As far as family is concerned, it's been a lonesome trek…It's probably just as much my fault as it is theirs, and I can't blame anybody for it. But there was…no real closeness, where the family urged me on, or said…'We're proud'…and all that. No, no…none of that happened.[2]: 7

While the lack of support from Carter's family caused her to feel isolated, it may also have instilled self-reliance and determination to succeed.[2]: 7 She studied piano at the Detroit Conservatory at the age of 15, but only attained a modest level of expertise.[4]

At the age of 16, Carter began singing.[1] As her parents were not big proponents of her pursuing a singing career, she would sneak out at night to audition for amateur shows. After winning first place at her first amateur competition, Carter felt as though she were being accepted into the music world and decided that she must pursue it tirelessly.[5] When she began performing live, she was too young to be admitted into bars, so she obtained a forged birth certificate to gain entry in order to perform.[6]

Career

Even at a young age, Carter was able to bring a new vocal style to jazz. The breathiness of her voice was a characteristic seldom heard before her appearance on the music scene.[7] She also was well known for her passion for scat singing and her strong belief that the throwaway attitude that most jazz musicians approached it with was inappropriate and wasteful. Her scatting was known to display a degree of spontaneity and basic inventiveness that was seldom seen elsewhere.[8][9]

Detroit, where Carter grew up, was a hotbed of jazz growth. After signing with a talent agent after her win at amateur night, Carter had opportunities to perform with famous jazz artists such as Dizzy Gillespie, who visited Detroit for an extensive amount of time. Gillespie is often considered responsible for her strong passion for scatting. In earlier recordings, it is apparent that her scatting had similarities to the qualities of Gillespie's.[10]

At the time of Gillespie's visit, Charlie Parker was receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital, delaying her encounter with him. However, Carter eventually performed with Parker, as well as with his band consisting of Tommy Potter, Max Roach, and Miles Davis. After receiving praise from both Gillespie and Parker for her vocal prowess, Carter felt an upsurge in confidence and knew that she could make it in the business with perseverance.[11]

Carter's confidence was well-founded. In 1948, she was asked by Lionel Hampton to join his band. She finally had her big break. Working with Hampton's group gave her the chance to be bandmates with artists such as Charles Mingus and Wes Montgomery, as well as with Ernest Harold "Benny" Bailey, who had recently vacated Gillespie's band and Albert Thornton "Al" Grey who would later go on to join Gillespie's band. Hampton had an ear for talent and a love for bebop.[12] Carter too had a deep love for bebop as well as a talent for it. Hampton's wife Gladys gave her the nickname "Betty Bebop", a nickname she reportedly detested. Despite her good ear and charming personality, Carter was fiercely independent and tended to attempt to resist Hampton's direction, while Hampton had a temper and was quick to anger.[13] Hampton expected a lot from his players and did not want them to forget that he was the band's leader.[14] She openly hated his swing style, refused to sing in a swinging way, and she was far too outspoken for his tastes.[15] Carter honed her scat singing ability while on tour, which was not well received by Hampton as he did not enjoy her penchant for improvisation.[13] Over the course of two and a half years, Hampton fired Carter a total of seven times.[1]

Carter was part of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra that played at the famed Cavalcade of Jazz in Los Angeles at Wrigley Field which was produced by Leon Hefflin, Sr. on July 10, 1949.[16] They did a second concert at Lane Field in San Diego on September 3, 1949. They also performed at the sixth famed Cavalcade of Jazz concert on June 25, 1950. Also featured on the same day were Roy Milton & His Solid Senders, Pee Wee Crayton's Orchestra, Dinah Washington, Tiny Davis & Her Hell Divers, and other artists. 16,000 people were reported to be in attendance and the concert ended early because of a fracas while Hampton's band played "Flying High".[17][18]

Being a part of Hampton's band provided a few things for "The Kid" (a nickname bestowed upon Carter that stuck for the rest of her life): connections, and a new approach to music, making it so that all future musical attitudes that came from Carter bore the mark of Hampton's guidance. Because Hampton hired Carter, she also goes down in history as one of the last big band era jazz singers in history.[19] However, by 1951, Carter left the band. After a short recuperation back home, Carter was in New York, working all over the city for the better part of the early 1950s, as well as participating in an extensive tour of the south, playing for "camp shows". This work made little to no money, but Carter believed it was necessary to develop as an artist and was a way to "pay her dues".[20]

Very soon after Carter arrived in New York City, she was allowed to record with King Pleasure and the Ray Bryant Trio, becoming more recognizable and well-known and subsequently being granted the chance to sing at the Apollo Theatre. This theatre was known for giving up-and-coming artists the final shove into becoming household names.[21] Carter was propelled into prominence, recording with Epic label by 1955, and was a well-known artist by the late 1950s.[22] Her first solo LP, Out There, was released on the Peacock label in 1958.[2]: 70

Miles Davis can be credited for Carter's bump in popularity, as he was the person who recommended to Ray Charles that he take Carter under his wing.[23] Carter began touring with Charles in 1960, then making a recording of duets with him in 1961 (Ray Charles and Betty Carter),[1] including the R&B-chart-topping "Baby, It's Cold Outside", which brought her a measure of popular recognition. In 1963 she toured in Japan with Sonny Rollins. She recorded for various labels during this period, including ABC-Paramount, Atco and United Artists, but was rarely satisfied with the resulting product. After three years of touring with Charles and a total of two recordings together,[24] Carter took a hiatus from recording to marry.[1] She and her husband had two children. However, she continued performing, not wanting to be dependent upon her husband for financial support.[25]

The 1960s became an increasingly difficult time for Carter as she began to slip into fame, refusing to sing contemporary pop music, and her youth fading. Carter was nearly forty years old, which at the time was not conducive to a career in the public eye.[26] Rock and roll, like pop, was steadily becoming more popular and provided cash flow for labels and recording companies. Carter had to work extremely hard to continue to book gigs because of the jazz decline.[27] Her marriage also was beginning to crumble. By 1971, Carter was single[28] and mainly performing live with a small group consisting of merely a piano, drums, and a bass.[1] The Betty Carter trio was one of the very few jazz groups to continue to book gigs in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[27]

Carter created her record label, Bet-Car Records, in 1969, the sole recording source of Carter's music for the next eighteen years:

....in fact, I think I was probably the first independent label out there in '69. People thought I was crazy when I did it. 'How are you gonna get any distribution?' I mean, 'How are you gonna take care of business and do that yourself?' 'Don't you need somebody else?' I said, 'Listen. Nobody was comin' this way and I wanted the records out there, so I found out that I could do it myself.' So, that's what I did. It's the best thing that ever happened to me. You know. We're talking about '69!

— Betty Carter, [27]

Some of her most famous recordings were originally issued on Bet-Car, including the double album The Audience with Betty Carter (1980). In 1980 she was the subject of a documentary film by Michelle Parkerson, But Then, She's Betty Carter. Carter's approach to music did not concern solely her method of recording and distribution, but also her choice of venues. Carter began performing at colleges and universities,[1] starting in 1972 at Goddard College in Vermont. Carter was excited at this opportunity, as it was since the mid-1960s that Carter had been wanting to visit schools and provide some sort of education for students. She began lecturing along with her musical performances, informing students of the history of jazz and its roots.[29]

By 1975, Carter's life and work prospects began to improve, and Carter was beginning to be able to pick her jobs once again,[30] touring in Europe, South America, and the United States.[27] In 1976, Carter was a guest live performer on Saturday Night Live′s first season on the air, and was also a performer at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1977 and 1978, carving out a permanent place for herself in the music business as well as in the world of jazz.[27]

In 1977, Carter enjoyed a new peak in critical and popular estimation, and taught a master class with her past mentor, Dizzy Gillespie, at Harvard.[31] In the last decade of her life, Carter began to receive even wider acclaim and recognition. In 1987 she signed with Verve Records, who reissued most of her Bet-Car albums on CD for the first time and made them available to wider audiences. In 1988 she won a Grammy for her album Look What I Got! and sang in a guest appearance on The Cosby Show (episode "How Do You Get to Carnegie Hall?"). In 1994 she performed at the White House and was a headliner at Verve's 50th-anniversary celebration in Carnegie Hall. She was the subject of a 1994 short film by Dick Fontaine, Betty Carter: New All the Time.[32]

In 1997 she was awarded a National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton. This award was one of the thousands, but Carter considered this medal to be the most important that she received in her lifetime.[27]

Death

Carter continued to perform, tour, and record, as well as search for new talent until she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the summer of 1998. She died on September 26, 1998, at the age of 69, and was cremated. She was survived by her two sons.[33]

Legacy

Carter often recruited young accompanists for performances and recordings, insisting that she "learned a lot from these young players, because they're raw and they come up with things that I would never think about doing."[34]

1993 was Carter's biggest year of innovation, creating a program called Jazz Ahead,[35] which took 20 students who were given the opportunity to spend an entire week training and composing with Carter, a program that still exists to this day and is hosted in The Kennedy Center.

Betty Carter is considered responsible for discovering great jazz talent, including John Hicks, Curtis Lundy, Mulgrew Miller, Cyrus Chestnut, Dave Holland, Stephen Scott, Kenny Washington, Benny Green, Tarik Shah, and Gregory Hutchinson.[27]

- CD compilations

- 1990: Compact Jazz – (PolyGram) – Bet-Car and Verve recordings from 1976 to 1987

- 1992: I Can't Help It – (Impulse!/GRP) – the Out There and The Modern Sound albums on one compact disc

- 1999: Priceless Jazz – (GRP) – Peacock and ABC-Paramount recordings from 1958 and 1960

- 2003: Betty Carter's Finest Hour – (Verve) – recordings from 1958 to 1992[37]

- On multi-artist compilations

- 1988: "I'm Wishing" on Stay Awake: Various Interpretations of Music from Vintage Disney Films

- 1997: "Lonely House" on September Songs – The Music of Kurt Weill

External links

- Seth Rogovoy, "Betty Carter: Still taking risks", Interview, Berkshire Eagle, November 14, 1997, via The BerkshireWeb.

- Betty Carter profile at MTV

- Martin Weil, Betty Carter Archived January 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Obituary, 1998

- Betty Carter profile at All About Jazz

- "Betty Carter: Fiercely Individual", in NPR's Jazz Profiles series, August 14, 2008