AS

OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN

THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON

NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2022/06/olu-dara-b-january-12-1941-legendary.html

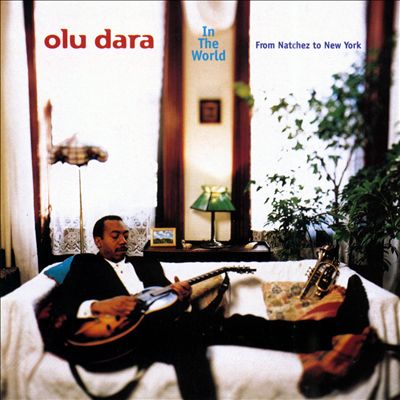

PHOTO: OLU DARA (b. January 12, 1941)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/olu-dara-mn0000890197/biography

Olu Dara

(b. January 12, 1941)

Olu Dara Biography by Chris Kelsey

Although he didn't record under his own name until 1998, Olu Dara enjoyed a reputation as one of the jazz avant-garde's leading trumpeters from the mid-'70s on. Early-'80s records and performances with the David Murray Octet and the Henry Threadgill Sextet revealed Dara to be a daring, roots-bound soloist, with a modern imagination and a big burnished tone in the style of Louis Armstrong and Roy Eldridge. Dara was born Charles Jones. He moved to New York in 1963, but did not perform publicly until the early '70s, when he became a part of the city's loft jazz culture. By that time, he had changed his name to the Yoruba Olu Dara. Besides his work with Murray and Threadgill, Dara also played with Hamiet Bluiett, James "Blood" Ulmer, and Don Pullen, among others. Dara was an intermittent presence on the jazz scene in the '80s and '90s, occasionally leading his Okra Orchestra and Natchezsippi Dance Band. In 1985, he recorded with Pullen and in 1987, with saxophonist Charles Brackeen; in the '90s he worked with vocalist Cassandra Wilson, playing on her Blue Note album, Blue Light 'Til Dawn. Not much else was heard from him -- from a jazz perspective, anyway -- until 1998, when Atlantic released In the World: From Natchez to New York, the first album released under Dara's name. The record was only tangentially related to his free jazz work. The music drew upon country-blues and African-American folk traditions. In addition to playing trumpet and cornet, Dara composed all of the tunes, sung, and accompanied himself on guitar. Atlantic released Dara's follow-up, entitled Neighborhoods, in early 2001.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/olu-dara

Olu Dara

Olu Dara is a multi-talented entertainer who has been performing since he was eight years old. Born (1941) in Natchez, Miss, Olu landed in New York in 1963 after a stint in the US Navy which took him all over the world.

“Stranded in Brooklyn” (as Olu sings in his tune, Neighborhoods), Olu turned to music to survive. During the 1970s and '80s, he gained a reputation as a trumpet/cornet player who could handle all aspects of jazz. On the one hand he could perform with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers (1973- 74), but he could also handle the demands of the free- flowing avant-garde style which formed the basis of the New York Loft scene of that period. But jazz was not the only musical style he was involved with, and gradually he turned away from it as increasingly he began to lead his own ensembles.

In the 1980s Olu put together two ensembles: Okra Orchestra, a 7-plus-member band, and the Natchezsippi Dance Band, a 5-piece unit.

Since then this has been Olu's preferred musical environment for creating the roots-based musical style that the audience now hears. In Olu's current repertoire, you will find a true fusion based on the Blues, but containing elements of African, Caribbean, R'n'B, and yes, even Jazz (but he won't admit to that) musical styles. In performance he plays the trumpet (pocket trumpet, and a wooden aboriginal instrument that he picked up on his travels), the guitar, harmonica, sings, and tells stories.

Dara, Olu

b. January 12, 1941

A highly regarded figure in the jazz scene since the 1960s, trumpeter and cornetist Olu Dara recorded his first solo record at the age of 57. Dara had always shied away from the spotlight, preferring to work with others like Art Blakey, saxophonist and composer Henry Threadgill, and the late pianist Don Pullen. Encouraged by his son, the rapper Nas, Dara finally agreed to record an album of his own songs in 1998. In the World: From Natchez to New York earned enthusiastic critical accolades for its fresh sound, which mixed Delta blues with African and Caribbean rhythms. That sound, Dara, asserts, comes from the fact that “I never practice the cornet,” he told Down Beat writer Alan Nahigian. “I never did. I was brought up that way. My teacher never said go home and practice. He said, how can you practice life? Music is life! Always go in fresh.”

As the title of his solo record hints, Dara hails from Natchez, Mississippi, where he was born Charles Jones in 1941. He was a performer from an early age, learning to tap dance and then picking up his first instrument. “This man gave me a horn, and told me to blow into it like I was blowing up a balloon,” he told Ed Bumgardner in the Winston-Salem Journal. “Next thing I know, I am playing the theme from ‘Woody Woodpecker’ and all these other cartoons I loved. If I could hear it, I could play it. Still can.” Dara left Mississippi to serve in the U.S. Navy, and played in a Navy band. He also visited parts of the Caribbean and Africa, whose musical traditions made a lasting impression on him.

Discharged, Dara was stranded in New York City in 1964 without funds to move on, and so he remained there. He claims not to have even owned an instrument for the next six years, but chance encounters with old friends from Mississippi and the Navy drew him back to music. As he recalled in the interview with Nahigian in Down Beat, his friends “were asking about playing music. I would just go and listen. When I finally started playing again, it was in the rhythm & blues bands, the natural place for me to be. We’d use two or three horns, and it was very creative.” But when this R&B style fell out of fashion, Dara moved on to jazz. Saxophonists Bill Barron and Sam Rivers helped him meet other musicians and find work in jazz ensembles, but it was still a difficult transition. “I was like a fish out of water,” Dara told Down Beat. “I loved to entertain, a song-and-dance man. I had to change my demeanor.”

Dara performed with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, a famed bebop ensemble, for a few years, even though he had never before played bebop. Blakey, realizing that Dara’s heart wasn’t in the genre, encouraged him to try something new. And so, while he was on tour in Spain with Blakey, Dara began singing, making up the words as he went along. After leaving Blakey’s band in 1974, he fell into the loft scene among New York City’s jazz set. He played with Pullen, Threadgill, and the David Murray Octet in the early 1980s, and appeared in recordings. “While the music he played was often far out, Dara won praise for an emotionally direct style that recalled traditional jazz trumpet masters Louis Armstrong and Roy Eldridge,” remarked Boston Herald journalist Larry Katz about this phase of his career. Still, Dara claimed to have been continually mystified by the jazz scene, though he was sometimes compared to Louis Armstrong. “I learned jazz in a couple of days so I could work,” he confessed to Katz. “I’d make sounds in a trumpet and they considered that top level musicianship. It really confused me. I just smiled and didn’t say anything. Then I’d go do my best work with my own bands.”

Dara’s bands included the Okra Orchestra and the Natchezsippi Dance Band. He also enjoyed working in the theater in New York City, as an actor and composer of music. Playwright August Wilson became a fan of Dara’s compositions, which included music for Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama The Piano Lesson. Moving forward and constantly moving on seemed to keep Dara’s interest piqued and his sound fresh. For many years, Dara played the trumpet, but then returned to the cornet. “When I played the trumpet, I sounded like all the other trumpet players,” he explained to Down Beat. “When I picked up the cornet, I went right back to the way I used to play.” He was sometimes hailed as the heir of cornetist Don Cherry, but at other times his musicianship evoked comparisons to African performer Hugh Masekela.

Though he was offered the occasional chance to make a solo record, Dara spurned the offers, preferring instead to work with performers like Cassandra Wilson, in whose 1991 album Blue Light’Til Dawn he appeared. He also appeared in the soundtrack for the 1996 Robert Altman film Kansas City, which fictionalized that city’s flourishing jazz scene in the 1930s.

It was only the urging of his son, on whose 1994 LP Illmatic Dara appeared, that he began to think about making a record. “He kept telling me he wanted his peers to hear me,” Dara told Bergen County Record writer Ed Condran. “He wanted to show me off, but I declined. Five minutes later Atlantic Records called and asked me to put out an album. I thought it was an omen, and I decided to make a record.” The result was In the World: From Natchez to New York, released in 1998. Dara wrote all the songs himself, sang, and played trumpet, cornet, and guitar for it. The Winston-Salem Journal’s Bumgardner described it as “a potent dose of rural blues, decorated with the street-party twitch-and-twinge of hiphop.” Bumgardner noted further that the record “pays homage to past and present while keeping the listener spellbound and, most likely, a little off-balance.” International Herald Tribune writer Mike Zwerin commented on Dara’s vocal style, finding him a “a mature, acoustic, melodic and poetic rapper—a rare and delightful cadence. He ‘blows’ his lyrics like improvising on a horn.”

Some of the tracks on Dara’s next effort, Neighborhoods, were hailed by Rolling Stone journalist Robert Christgau as “history lessons” whose force would only be appreciated twenty years hence. Again, the record featured Dara on vocals, and playing the cornet, wooden horn, and guitar. Cassandra Wilson and Dr. John appeared on tracks, and Dara also wrote a tribute to his longtime conga player, Coster Massamba. Down Beat’s Glenn Astarita liked “Massamba” and the title track, as well as other songs in which “the artist shuffles through the Delta blues and New Orleans voodoo style r&b while also extolling the virtues of nature, love and life.” Another writer for the magazine, Michael Jackson found it a record that “seeps with Delta blues, inner-city soul, Bo Diddley-fied shuffle-funk and African rhythms, furthering Dara’s voyeuristic, nostalgic odyssey through life’s highways and byways.” The Bergen County Record’s Condran also commended it as an “intense, gritty, but atmospheric jazzy release, which sounds like a slice of New York.”

Dara also earned accolades for his live shows. “What he proffers has a timelessness with context,” declared Variety reviewer Phil Gallo, “everything he plays feels familiar, with roots linked to a distinct time and place, whether it be the Mississippi Delta in 1934 or Times Square circa 1971.” Dara’s two other sons are also involved in the arts. A resident of Harlem, he was bemused by the Rolling Stone review. “It’s not that I’m ungrateful that some magazine thinks I’m cool, but, see, none of that matters to me, even though I suppose it is supposed to,” he told Bumgardner in the Winston-Salem Journal. “But if it helps bring my music to more people, if it broadens minds and heals spirits, then that can only be a good thing.”

Selected discography

In the World: From Natchez to New York, Atlantic, 1998.

Neighborhoods, Atlantic, 2001.

Sources

Periodicals

Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 15, 1998, p. D2.

Boston Herald, March 8, 2001 p. 45.

Down Beat, May 1998, p. 36; June 2001, p. 16; July 2001, p. 66.

International Herald Tribune, June 13, 2001, p. 10.

Record (Bergen County, NJ), January 18, 2002, p. 15.

Rolling Stone, May 10, 2001.

Star-Ledger (Newark, NJ), March 4, 2001, p. 6.

Time, June 24, 1996, p. 79; February 26, 2001, p. 72.

Variety, April 16, 2001, p. 36.

Winston-Salem Journal (Winston-Salem, NC), May 4, 2001, p. El.

—Carol Brennan

Olu Dara

Trumpeter, cornetist, singer, guitarist, bandleader

A performer from an early age, Olu Dara was a leading trumpet player in New York's burgeoning avant-garde loft-jazz scene in the 1960s. He has played with Art Blakey, David Murray, and Henry Threadgill, among others, and headed his own blues-oriented outfits, the Okra Orchestra and the Natchez-sippi Dance Band. Dara released his first solo album, In the World: From Natchez to New York, in 1998 at the age of 57. This album established him as a multi-faceted performer steeped in a wide variety of musical traditions.

Dara took the long, slow route to solo stardom. A mainstay on the avant-garde jazz circuit in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the leader of his own blues-oriented orchestras, the multifaceted musician did not release his first solo album until 1998. At that time, he was 57 years old. Raised in Natchez, Mississippi, Dara told Jazziz, "I didn't come from a situation where you were record-oriented. I was just a guy who was a song-and-dance man, a stage man. I didn't come to New York to record, to become a musician, so I wasn't in that mindset."

Born Charles Jones III on January 12, 1941, in Louisville, Mississippi, Dara displayed a talent for music and performance at an early age. His father was a popular singer, his uncles were traveling minstrels, and his great-uncles performed in the Rabbit's Foot and Silas Green touring carnivals. Dara first learned to play piano and clarinet, then took up the cornet. He was performing by age seven and touring by age ten. Dara continued to play trumpet and cornet throughout high school and at Tennessee State University, where he entered as a pre-med student but also joined the marching band. When he switched his major to music, he was too late to schedule any of the top-notch classes, so he dropped out of college and entered the United States Navy.

Traveling with the Navy, Dara not only played trumpet regularly but was exposed to a wide variety of rhythms and sounds from around the world. "I heard a whole lot of stuff in the navy," he told Down Beat in 1982. "I think it made me complete."

Dara was discharged in New York in 1964 and decided to stay in the city, although he did not play music for several years. Only after encountering several high school, college, and Navy friends, including drummer Freddie Waits, saxophonist Hamiet Bluiett, and vocalist Leon Thomas, did he again pick up the horn, focusing primarily on the cornet. Switching instruments allowed him to develop his singular style. "When I played the trumpet, I sounded like all the other trumpet players," Dara told Down Beat in 1998. "When I picked up the cornet, I went right back to the way I used to play. I don't think I play any different now than I did when I was 12 years old." His tone is often compared to Louis Armstrong or Roy Eldridge, and his organic channeling of the blues often reminds listeners of Taj Mahal. Dara is largely regarded as one of a kind. "Olu can play with one note what most people can only play in a whole solo," cornetist Butch Morris told Jazziz. "He also understood the mutes better than most, and how to deflect the sound."

Although his penchant was still for the blues-oriented music of his youth, as well as the multicultural sounds from his navy days, Dara became a fixture in the city's avant-garde loft jazz scene, where talented horn players were a hot commodity. It was during this time that he adopted his current name, given to him by a saxophonist who was also a Yoruba priest. One of his earliest steady gigs was with legendary jazz drummer Art Blakey, who was the first to encourage Dara to follow his own path. "'Look, this s**t is boring to you, ain't it?'" Dara recalled Blakey telling him, according to Down Beat. "'Look, go out and do what you want to.'" Given such license, Dara proceeded to sing the impromptu, storylike lyrics that are a staple of his solo releases and blow blues-inspired trumpet riffs.

This experience inspired Dara to set off on his own, forming first the Okra Orchestra, named after his favorite vegetable, and then the Natzchezsippi Dance Band. "The adventurous jazz I was playing wasn't my music. It's like having a job," Dara told the Boston Herald in 2001. "You may be working in an office and not want to be there, but you're there until you find something that you're comfortable with. That's why I formed my own band."

Dara continued to record and perform with a variety of other musicians, many of them at the forefront of the avant-garde, including Bluiett, Oliver Lake, David Murray, Henry Threadgill, Bill Laswell and James "Blood" Ulmer. He recorded two solo albums, neither of which was ever released. "I think I may have been a little too visionary," he told the New York Times. He also began to score and peform music for the theater. He has worked with playwright August Wilson, choreographer Diane McIntyre, and poet Rita Dove, among others, and he even performed in the musical Hair. In 1995 he acted in director Robert Altman's film Kansas City and contributed to the soundtrack. In the late 1980s Dara also began accompanying Cassandra Wilson, and is featured on three of the highly regarded vocalist's albums. In the 1990s, he also accompanied his son Nasir Jones, a hip-hop artist who records under the name Nas.

Honing his engaging, storytelling vocal style throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Dara finally released a solo album, In the World: From Natchez to New York, in 1998 to widespread critical acclaim. In the World was followed by Neighborhoods in 2001, and both albums made Dara's name not only as a multitalented musician, but as a captivating lyricist. "Not many artists release their debut as a leader several decades into their career, and fewer do with as stunning an artistic turn-about as Olu Dara, whose 'In the World from Natchez to New York' established the cornet player as a singer, guitarist, and top-notch storyteller," wrote Billboard 's Steve Graybow in 2001. "Dara's 'Neighborhoods' follows in the footsteps of that auspicious release, liberally mixing blues and jazz with humanistic storytelling in the African tradition." Music is, after all, a form of storytelling, Dara pointed out in a 1996 New York Times interview. "When we get together, there's no words thrown away, no idle talk," he recalled of his visits with Nas. "We'll sit down, play drums and conversate musically."

Born Charles Jones III on January 12, 1941, in Louisville, MS; married Fannie Ann Jones (divorced); married Celeste Bullock; children include: Nasir ("Nas," a rap musician), Kiani, Jabarai ("Jungle"). Education: Attended Tennessee State University.

Began playing music at age seven; joined U.S. Navy, 1960s; performed on avant-garde jazz circuit, 1960s-1970s; led the Okra Orchestra and Natzchezsippi Dance Band, 1980s; performed and recorded with other artists including Hamiet Bluiett, Cassandra Wilson, and son Nas, 1980s-1990s; released first album, In the World: From Natchez to New York, 1998; released Neighborhoods, 2001.

Addresses: Record company— Atlantic Records, web-site: http://www.atlantic-records.com.

Whether playing with an avant-garde ensemble, heading his own orchestra, scoring for the theater, or playing solo, Dara's approach has always been spontaneous and improvisational, rooted in the the blues and gospel traditions of his youth. "The whole 15 years, I think we've spent maybe a total of eight hours [practicing] altogether," Dara told Down Beat of his long-time ensemble, which includes bassist Alonzo Gardner, guiarist Kwatei Jones Quartey, drummer Greg Bandy, and conga player Acosta Musamba. This approach is long-ingrained. Dara added, "If you go to a doctor's office, he doesn't say, 'Well, let me go home and practice how I'm going to put this bandage on you.' That's the way I look at music…. I never practice the cornet. I never did. I was brought up that way. My teacher never said go home and practice. He said, how can you practice life? Music is life! Always go in fresh."

Selected discography

In the World: From Natchez to New York, Atlantic, 1998. Neighborhoods, Atlantic, 2001.

Sources

Periodicals

Billboard, February 10, 2001.

Boston Herald, March 8, 2001.

Down Beat, August 1982; May 1998.

Jazziz, April 1998.

New York Times, October 6, 1996; April 20, 2001.

Online

"Olu Dara," All Music Guide, http://www.allmusic.com (January 2, 2004).

"Olu Dara [Jones, Charles, III]," Grove Dictionary Online, http://www.grovemusic.com (January 2, 2004).

—Kristin Palm

Olu Dara & the Okra Orchestra

Yoshi's Jazz Club

July 17, 2000

Oakland, California

In a riveting display of musicianship and stagecraft the great multi-intrumentalist and consummate storyteller, blues vocalist, and Jazz griot Olu Dara led his astonishing orchestral quintet in a glorious two-set, one night appearance at the exquisite Yoshi's Jazz club in downtown Oakland.

Weaving a seamless web of African-diasporic melodic, rhythmic and sonic musical traditions, Dara and cohorts absolutely mesmerized the packed house with a stunning command of a grand smorgasbord of global black musical styles: West African highlife (both trad & Fela Kuti-inspired) Caribbean reggae, calypso, dance and ska, Mississippi delta blues, fifty years worth of prime-rib Afro-American funky rhythm & blues, and an endless array of Jazz-based and inflected styles from Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Cab Calloway, and Duke Ellington, to Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and Art Blakey (and black again).

What made the event so extraordinary, aside from the incredible versatility of Dara and his band, was Dara's heraldic and bravura tone on cornet (open & muted), guitar, and blues harp, as well as a captivatingly charming, hip and even slick, stage presence. Handsome, sly, witty, sweet, sexy, tough, downhome and vulnerable all at once, Dara looks, acts, and sounds like a great novelist's, poet's or filmmaker's idea of a legendary musician. There is something positively iconic and aesthetically arresting about the way that Dara plays, sings, talks, and moves that bring to mind such adjectives as 'heroic' and 'archetypal.' He and his amazing ensemble (Kwatel Jones-Quartey on guitars and vocals, Coster Massamba on congas, Alonzo Gardner on electric bass, and Larry Johnson, drums) somehow manage to sound like a large orchestra through ingenious instrumental voicings and harmonically deft orchestrated arrangements that conjure up a density of tonalities and quicksilver textures that effortlessly slide from one sonic area of black musical history to the next.

The really eerie thing about this band is that despite its myriad of inherited forms it NEVER sounds derivative or stuck in any static nostalgia zone (take THAT Wynton & acolytes!). Its resolutely independent sound identity is so fixed and clearly enuciated that it sounds like a series of Romare Bearden, William Johnson, Bill Traylor, Thornton Dial and Jacob Lawrence paintings come to life (with J-M Basquiat dancing fiercely along the edges!). The startlingly lucid execution and collage-like structures within such a thoroughly ROOTED musical conception also reminds me of the famous Roscoe Mitchell quote of "jitterbugging with the artifacts in the sound museum." The other sublime thing about Dara is that he can really sing and play the blues, and he possesses a poet's sensibility on cornet that can be majestic, tender, celebratory, melancholic, poignant or gruffly beautiful in a way that can only be compared to Pops Armstrong & Miles in its precise attention to emotional and expressive nuance (he even played a haunting homage to Ellington's first great soloist, and musical collaborator from the 1920s, Bubber Miley).

Finally what Dara and his orchestra demonstrate is that the creative key to African American music lies not in lazily imitating or emulating, in a repertory-like fashion, the triumphs of the past, but in fearlessly engaging, and transforming, the present (like all the former greats did). The story this band tells is not of aesthetic glories locked in the glass-case museums of yesteryear, but of the profound and dynamic adventures of this very moment and those yet to come. Our only task (aside from dancing ourselves into a frenzy) is to listen and learn...

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Kofi Natambu is a writer and cultural critic who loves great music and musicians. He lives and works in Oakland, California

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/olu-dara/

Olu Dara. Photo by Enid Farber.

Courtesy of Enid Farber Fotography.

Olu Dara is living drama. A trickster who lets aura shift around him. Anybody who’s talked to him knows that. Unbelievable events unfold every day. He allows them to collect in his bones and resolve themselves in the work. They make peace somehow. When I caught up with him, we ran smack into a hysterical man who was beating on a puppy dog because the man’s brother had died. I called the cops, conflicted regarding the man’s future. Olu bore witness, noting stock stillness on the two adjoining blocks, looks of shock and failed attempts to stop the action. He looked into the eyes of the dog. Our interview naturally emphasized one’s place in the scheme of things.

At a soul food eatery in Harlem, Olu, a multi-instrumentalist from Natchez, Mississippi, discussed his approach to music, his country look at life, and after all these years, his decision to do his own album (In the World, Atlantic Records), which includes a track of improvised (freestyle) rhymes. Olu has developed music for two of his own bands and several theater pieces. Best known for his collaborations with dancer/choreographer Diane McIntyre, Olu is currently working on a play by Rita Dove, The Darker Face of the Earth .

Tracie Morris You’ve become a professional storyteller in a way…

Olu Dara Yeah, never because I wanted to, I just had so many stories to tell. I remember as a kid, people didn’t believe me. People say truth is stranger than fiction—well, I’m one of those people.

TM You accepted your destiny?

OD I enjoyed it after awhile. I thought, maybe this is a special thing I’ve been given to fit my personality.

TM Is that why you ended up choosing so many different ways to say things?

OD I was always eclectic. Other children would select one thing to be good at, and I’d select everything. I never looked at things as being difficult. You read articles and they say the trumpet is a very hard instrument to play, you have to practice eight hours a day. I never practiced in my life. I consider it the easiest instrument to play, blowing the trumpet is as easy as blowing up a balloon. Even today, if I don’t have a gig with it, it will never come out of my bag. It’s not on my mind, because so many other things, they’re more important.

TM Like what?

OD Usually it’s just finding different instruments to play, drawing, wood burning, meeting new people. Meeting young people through my kids, that fascinates me. There’s no communication gap between me and the young. I understand their language. I listen to their music, I understand why they dress the way they dress. I never left my childlike vitality in the dust, I always kept it. I can still think like a youngster.

TM Yeah, but the stuff that you’re playing on this new record is very oriented towards tradition.

OD Yes. It came out that way. I didn’t plan that record. Half of the stuff I made up in the studio. The musicians weren’t there—I just laid up songs by myself on the guitar. I did a tribute to Zora Neal Hurston, but I didn’t think about her until I sat down and started playing—the words came to me: “Zora/ I feel so bad! So sad! I heard they ran you out of Harlem! I heard you cleaning for a man/ who owns a paper mill/ way down in Edenville…” All of the new things I composed for the record just came to me as I started playing in the studio.

TM Who suggested the piece that you and Nas (your son) did?

OD I brought him in, he listened to it—I didn’t really write that piece specifically for him. He came into the studio and sat there a long time just listening, then he came back a week later and did the same thing, just sat there and listened for a couple of hours. Finally he got up and just started talking.

TM It was a really nice collaboration. His flow works so well with yours. It’s like some sort of genetic understanding you all have.

OD That’s what it is, the same thing I had with my father, a genetic understanding. We could talk without speaking.

TM The lullaby you did for your youngest son, Kiani, was really sweet too. You sound like a doting father.

OD I am. (laughter) That’s all I am.

TM Well, you adopt everybody. Who are some of the kids that you feel you’ve raised in the performing arts industry?

OD I would hate to name names because I would have to list at least twenty or thirty of them.

TM Well, how about ten?

OD I really couldn’t name them all. There are so many musicians who have come through my bands, and dancers and actors whom I have worked with in the theater. They’re all over the place in terms of artistic medium. I see people I’ve helped raise making names for themselves now in hip-hop, blues, theater, film and literature.

TM Besides your own release, I think the last person I’ve heard you work with on a record was Cassandra Wilson, on Electric Magnolia.

OD I hope I had some influence on Cassandra. I believe I did a little bit.

TM She’s from Jackson, Mississippi. So, is it just a Mississippi value system coming through, or…?

OD Yeah, that’s what it is. I grew up in Mississippi, and I think the older I got, the more Mississippi experiences and roots started coming back in my music. You have to understand, I was high up in the avant-garde jazz situation at one time: be-bop, and Art Blakey. Way away from Mississippi. Somebody who likes to do the music like I do, up in New York, they would look at you like you’re crazy. “Blues? And country blues like that? Stop playing your harmonicas and guitar, and start playing your trumpet.” When I formed my Okra Orchestra, I’m not going to say it was a brave thing for me to do, but… everybody else was playing be-bop or avant-garde jazz. But I had to do it. I was playing with Art Blakey in Spain somewhere, a strong be-bop band—and he looked at me and said, “This shit’s boring you, isn’t it? It ain’t nothing to you, is it?” I was on the sidelines, waiting. I had finished my solo, and he was laughing like he always laughed; but he was talking to me while he was playing, saying something completely different from his expression, like, “Ha-ha-ha, this shit ain’t shit for you is it?” I thought: I’m glad he said it. It’s nothing to me. I can play this in my sleep. You play a solo and then you stand back on the stage. It ain’t enough. He said, “Go out there and do your thing. Tell jokes…” That’s what I did, I told jokes, did a split. Sang the blues… And eventually I got us out of a little trouble in certain nightclubs we played in the Midwest, because people didn’t want to hear any jazz, they wanted to hear blues, and I would come out and sing the blues and get the people off of Art.

TM Really? What kind of audience comes to hear Art Blakey, and does not expect to hear jazz?

OD They didn’t come to see Art Blakey. He had a gig in a nightclub where they hire bands, maybe somebody there liked jazz… They’d just come. I got caught in a couple of places where people would say, What the hell is this? You’d better change that shit quick.

TM So here comes Olu Dara, and what did you do?

OD Made up blues songs. Double entendre blues songs until they were satisfied, and then we’d go back and play a little jazz.

TM So tell me a little bit more about how you work on words for your songs?

OD I never come prepared with words, whether I’m going to record or do a live performance. My words come as soon as I step to the microphone. Other than that, I have a block. But when the first beat hits, I got lyrics.

TM How did you get in a position to work with so many theatrical productions?

OD When I formed my band, the Okra Orchestra, it was different from all the other bands that were playing around at the time. My band was theatrical. I told stories, we played music from all genres, all eras. I would have theatrical things happen, like girls belly dancing, girls bouncing canes on their shoulders and hips. I’d have girls washing clothes…

TM Washing clothes?

OD Actually washing clothes on stage, to the rhythm.

TM Do you mean playing washboard, or do you mean washing clothes?

OD A washtub, a washing board, soap, water, clothes, and a girl beating eggs to the rhythm. For my last performance at Symphony Space, I brought that back in a piece I did with Diane McIntyre called “Bluesrooms.” We had one girl washing clothes, and another beating eggs to a song I had written called “Kitchen, Kitchen, Let Me Go.” Two young girls visiting their aunt down South, college girls, and she had them working in the kitchen. And they’re singing with the eggs being beaten to the rhythm: “Kitchen, kitchen, let me go:” So, that’s how I got into theater and the dance world. They used to come and see me. Some of the greatest writers in America used to come down and ask me to write music, or act in a play. All the people that I had admired from a distance in other fields, I met them all through my band. They would come and see the Okra Orchestra.

TM Yeah, it was really quite an effective group. You had the Okra Orchestra and Natchezippi. What do you call the new collective that you put together for the album?

OD I don’t have any name for them. I just used my name, “Olu Dara,” because it’s not a group anymore, it’s just things I do. In Natchezippi and Okra I did specific things. They had a purpose. Okra was a theatrical nightclub band and Natchezippi was a concert band. I did fifty different things with those two bands.

TM So what made you take the plunge? This is your first lead album project, but you hold on to those other people.

OD Recording was the last thing I wanted to do. Because it didn’t mean anything to me. It won’t describe me. I can’t put what I do on a record, and I knew that. I did it because my sons wanted me to do it. People in my family, cousins, everybody just started asking me. Yves Beauvais, the producer at Atlantic Records, has been trying to get me to record for the last five, six years. He had seen everything I’d done, not just nightclub and concert stuff but theatrical stuff, the dance stuff, storytelling things. So, the combination of all these people asking me… I mean, musicians in the street saying, “Well, you should do something at least for posterity.” I thought, Okay, I could write some new stuff and do some of the music that I put together for the Okra Orchestra. With that group I was doing years ago what the hip-hoppers are now doing rhythmically and conceptually. Before I formed my band I was an original member of the Fatback band called Pretty Willie and the Soul Brothers, playing rhythm and blues. We used to mix it all up: jazz, rhythm and blues, funk, gospel, everything in one band. And that’s the concept I always liked: to be able to play everything. When I was growing up I thought a musician was someone who played all music, not just one style. I was shocked when I found out people just play one style of music for their whole lives. I couldn’t understand how somebody could do that! With so much music in the world, so many influences, and each one can make you feel so different, take you so many places.

TM What about critics who would argue that in order to do something really well, you have to focus. And that if you start to mix then you lose the integrity of that particular form…

OD That’s been disproved so many times, I disproved it myself. I’ve played with the greatest be-bop musicians, the greatest avant-garde musicians they had in my generation, funk musicians; I made a name in all those fields, and I didn’t lose nothing. I was proficient in all of them.

Olu Dara and Diane McIntyre

TM Who would you say is one of your favorite people that you’ve worked with?

OD Oh my goodness… Diane McIntyre, she’s my favorite of all time. She knows everything, more music than most musicians. I like her because we can fly. We can create shows in three days, and be successful with it. And have elements in it—drama, music, dance—surprises.

TM She’s not even a musician.

OD Not even a musician. She’s the greatest artist I’ve ever worked with, period. And I think I’ve been in more bands than any musician I know.

TM In a previous interview you talked about your close-knit community and family. How did you manage to maintain that throughout the years [in New York]?

OD New York is a small town to me. The whole five boroughs. I look at it as a small community, because I’ve played in mostly all of the communities. Black, white, whatever. A lot of people from different communities like my music. I’m easy to know.

TM You do inject a lot of humor in your work. How did that concept develop?

OD That’s natural, I was very theatrical when I was a child, doing school events, school plays. I was a very shy guy but then I developed a sense of humor because I saw that most people were not happy. I could see sadness in people’s faces, and fear. I had a certain type of exuberancy about life itself. I developed a sense of humor to make situations easier for me. That is the way I am.

TM Very social.

OD Yeah, I’m a very social person. People need other people to make them feel better, that’s all. That’s why in my music I try to keep a happy thing going on.

TM I see, parts of the album are really introspective. What was the reason for that?

OD I knew there were people who needed to hear some of the things I was saying. Usually, my themes are about women, food or children.

It just happens every time I open my mouth, the song is going to be about a woman, some food, or some children.

TM I gathered from your career that you like okra.

OD Yes, love it. Crazy about it.

TM Are you satisfied with the kind of contractual arrangements that you got with Atlantic?

OD No, I’m not satisfied. I wouldn’t be satisfied unless I got what European blues musicians get for a contract. But I don’t expect them to give me a contract like that. The Rolling Stones or any other European group can cover one of my songs and make more money than me, so I don’t expect to be satisfied monetarily. But I’m satisfied in the respect that nobody’s telling me what to play. The producers, the record company know what my career is all about and they know what I do.

TM So you had artistic freedom.

OD Yeah, that’s all I want. You can get the money other ways.

TM It seems like a lot of artists or performers now are working under severe artistic constraints. There’s a lot of rigidity in schools of thought and how people should approach music.

OD Like I said, being eclectic with music cancels all the problems. I’m just a musician, I’m not one who says this music is the greatest, be-bop, classical music or country blues. My job as a musician is to be able to get all these things out, all the music that is in my culture. If a musician lives in a village in Senegal, he has to know all the music within that village. I have to be familiar with all the music in America. A surgeon should know the total human body, and not just the leg.

TM Even if you are a specialist.

OD Exactly. If you’re a musician, then be a musician! I play for me and I play for the earth, but basically, it’s not what you’re playing, it’s who you’re playing for. There’s an audience sitting out there, that’s what I’m thinking about.

TM So you play for your audiences?

OD I play for me and the earth first, but when I say the earth, that means everybody. Each audience requires a different thing. Each place requires a different thing.

TM So, being perceived as an entertainer doesn’t bother you?

OD No, it doesn’t bother me at all, because that’s what I am. I want to do the most difficult feat, which is to entertain and to create.

TM You talk about the responsibility of someone in a village in Senegal, and I know you were in Africa when you were in the Navy. Did you extract anything from that experience that influenced your work?

OD What it did was reaffirm what I already thought music should sound like, feel like. I got a good part of what I needed musically from the country blues music that I got growing up in Mississippi. I was prepared for African music because the blues they sing in Mississippi and the rhythms they play connect with it. I understood the intricacies, all the subtleties of it, it was just like the blues language. And I don’t mean urban blues, I mean country blues. There’s a big difference.

TM There seems to be a resurgence in the blues these days.

OD There is. It’s a resurgence in old blues, but new blues is there. I consider all the hip-hop people blues people, I consider the rhythm and blues people of today, like Mary J. Blige, stoneblues; just as blues as anybody else. Even more blues because they’re using more African rhythms. The older blues rhythms only used a few rhythms because the drum had been taken away—they used the shuffle on the back beat and stuff like that. Hip-hoppers use polyrhythms. Rhythm and blues people now use polyrhythms, whereas back in the early days only one musician would have used it, and that was James Brown, and maybe Sly.

TM Sly Stone?

OD Yeah, but particularly James Brown. Everybody else was doing the shuffle and the four note beat. James Brown was unique. And now, blues is coming back. It’s here, modern blues is here. They don’t want to call it that, but that’s what it is. I look at videos and the young people, listen to their music, and I say, Man, that’s more blues than we had back in the day. But they call it other names now. All it is is blues with more sophisticated rhythms. Like Keith Sweat, that’s blues to me. I could name a lot of them, but you understand what I’m trying to say. On my album I tried to do as much old stuff as I could. I like music in all genres so I went to the Caribbean sound, the Mississippi sound, I did the African High Life, I did contemporary blues. If I do another album I’ll come an a contemporary one, where I want to be anyway. Where I really am in my heart.

TM Getting back for a second to how you see contemporary R&B as being a continuum of traditional blues forms, there’s a lot of wordplay on the record.

OD Yes, with the vocals, instrumental music has taken a back seat. It didn’t progress as fast as our vocal music in this country. Instrumental music has its leaders, whereas the blues, and hip-hop, they don’t have icons and leaders, they don’t look at one person and say, “Well, that’s the king and queen of that.” They go do their thing. Mary J. has got her thing, in hip-hop, Nas got his thing, Wu-Tang got their thing, Snoop got his thing, they’ve got many places to go.

TM That’s a radical point of view that you’re offering, because a lot of people complain that contemporary black music doesn’t have the musicality that its predecessors have had, in terms of form.

OD That’s because they’re prejudiced against the youth, and when they hear a new rhythm they’re afraid of it. They’re afraid of the lyrics, the rhythm, the way they dress, they’re intimidated because these are new people. That’s all it is, fear and intimidation. And they don’t listen to the music.

TM But a lot of the work, Olu, was developed in the studio by producers, and not as much by the artist.

OD Yeah, but the producers get their information from the artist. They don’t come out of their head with this information, if they did they would be doing it themselves. They get it from watching artists. So all they do is make the concept more palatable to the public on an LP. But when these same people go out in public, they can stretch out. I’ve done most of the things I’ve wanted to do. I’m satisfied. The last thing I hadn’t done in the art world was make a record. I’ve done everything else. So now, I do a record. Why? Because there’s nothing else to do.

TM This is the first time I’ve talked to someone who said they did a record because they didn’t have anything else better to do.

OD That’s the main reason I did it. I never was interested in records, mainly because they’re produced. I know what real people sound like. When I go and hear a record I say, That person doesn’t sound like that. He doesn’t play like that. So, that’s why it never interested me, it’s just a business venture for people to get known or whatever. I had other talents to make me happy. I didn’t need a record to be known. As a matter of fact, I kind of liked the idea of doing it on my own, to see if I could sustain my career with no records, that was fun. I still packed the places. No records. Still get new fans every year. No records.

TM Tell me about this project you’re doing with the poet laureate Rita Dove?

OD This is Rita Dove’s first play called, The Darker Face of the Earth. We did it at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival last year and it was very successful. So we’re doing it at the Crossroads Theater here in New Jersey, and we’re going to take it to the Kennedy Center in November.

TM How exciting.

OD I got a chance to write some beautiful music for it, and I enjoy her concepts. She uses a Shakespearean approach, but it has to do with slavery. I’ve never seen anything in theater with a different twist on slavery like this one, it’s beautiful. It’s epic-like.

TM How was it to collaborate with her? Did she just give you free reign, did you guys go over concepts?

OD Free reign. “Come in,” she said, “I want you to do a little music,” that was it. I met her in New Jersey.

TM How?

OD I went to the opening of The Piano Lesson. I was doing some of the music for it and I met her in the lobby with some people. They introduced her to me and she said, “I want you to do my music!” I said, “Cool.” I said, "I’ll do it different. It won’t be music you’d find in slave movies!’

TM So what influenced your decision on how to approach the music for that piece?

OD The characters are not too long out of Africa, so instead of having those old field hand type songs we’re used to hearing in slave movies, I put more of an African flavor to it: (singing in a West African motif) rather than (singing) “swing low, sweet chariot…” I had a little of that in there, because that was in the script, but everything I do has an African edge to it.

TM You mix a lot of those musics together, it seems really organic in the album.

OD You mean within one song? Yeah. I do that naturally in my performances. I didn’t know if I was able to do that on the album, but since you say so, I’m glad to hear that. I may play a couple of notes and say, That’s enough of you. Bring your cousin Henry in here. That’s the way I think when I’m playing. I get tired of one form quickly, so I had to put them all into one song.

TM Now, you told me that your songs are about women, food and children…

OD When I was growing up in the rural section, my mother would say, “We’re going to see Mrs. Mary!” I would say, “I don’t want to go. I’ll stay here!” But when she’d say, “We’re going to see Mrs. Lucille,” I’d say, “Yeah, take me with you, because Mrs. Lucille’s kitchen is popping!” I wouldn’t go to houses where there were no good cooks, that didn’t have a nice food aroma. Or I wouldn’t go to people’s houses that weren’t into cooking. It turned me off.

TM I’m with you there, you’ve got to have food. The worst thing in the world is not having enough food when somebody comes over.

OD That’s the worst feeling, hurts me to my heart. Some people don’t care, though. I want to give them a feast, if I could…

TM See, I thought that was a Southern black woman thing, but it’s obviously not if it makes you feel embarrassed too.

OD I feel a lot of troubles if people come in the house and there’s no food.

TM So you can cook and all?

OD Yeah.

TM What would you consider your primary medium of conveying your ideas?

OD It would have to be music, theater and visual arts mixed.

TM But if you had to do one thing to represent yourself?

OD That’s a hell of a question. I think what really satisfies me best is having a guitar in my hand and singing. Singing and telling stories. Sitting on a chair or a couch with just a guitar, talking. I could do that for the rest of my life.

Tracie Morris is an award-winning performance poet, bandleader and recording artist from Brooklyn, New York. Her most recent work is a text for Ralph Lemon’s Geography Project, debuting at Yale Repertory Theatre in 1997.

https://web.archive.org/web/20010718031238/

For the longest time, I merely knew Olu Dara for his avant work with David Murray and Henry Threadgill. That is until his Atlantic debut, In the World, which blew those perceptions out the window. Shows how much I know. But as the father of Nas, I would not expect any less. I still miss Olu Dara the free jazz trumpeter though. Olu Dara spoke with me by telephone and gave me significant insight into his life, his loves, and his music, as always, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

OLU DARA: I met a man, who had just moved in town that day, one day, I think I was seven years old and he started me off with the clarinet, all forms of art, visual arts or whatever, and eventually, I moved to the cornet and piano. I think we started a band maybe a year or two after that. My mother says we started the band right away. I don't remember that, but I do remember playing in a small band with him and traveling around Mississippi and Louisiana. And from that point on, I went really into show business, as they say, giving concerts at schools and performances around the neighborhood in Mississippi, Louisiana, with the band and sometimes by myself.

FJ: It almost sounds like it was work for you.

OLU DARA: I don't think I was really enthusiastic about music. To me, it was just something that I was taught to do and something that I knew that the townspeople appreciated seeing, seeing young people, the group was integrated age-wise. We had young adults and we had college people in the group and there were kids that were in middle school in the group. I think it may have been a nine-piece band. But to me, it was just something that I did, just like having a job for the community really.

FJ: So there was no interest to play like a Louis Armstrong?

OLU DARA: We didn't have, I don't think we listened to radios in the house. We didn't have record players. My parents were not really interested in that and so it was live music all the time and that spanned from opera to country blues and everything in between in a small town. We had people who could perform any type of music and of course, Mississippi is known, especially the river people, they are known for doing all kinds of music.

FJ: Why did you decide to leave the Mississippi Delta for bright lights, big city?

OLU DARA: Yes, I came here. I was still in the military and I was discharged from the military, the navy in 1964. I had played music in college and also my duration in the navy, which was four years. I got stranded in New York. I ran out of money and I stayed here, but I never really had any intentions of becoming a professional musician in New York. It never entered my mind. So I did other things for many years, maybe six or seven years before I got back into music.

FJ: How did you pass the time?

OLU DARA: Oh, many things. I worked in the administrations office at a hospital in Brooklyn and worked at the navy yard in administrations over there. I worked at a youth, child detention home in the Bronx, teaching music. Let's see. What else did I do? I ran discothèques in Brooklyn. I worked in real estate for a minute. What else? A Japanese newspaper company. And eventually, I got back into music.

FJ: With such a lapse in time, did you find it difficult to get your chops in order?

OLU DARA: No, I found it, I thought it would be. That's why I never really attempted to do anything in New York City. But once I got back into it, it was relatively easy. Right away, I started working, as soon as I got a horn. I started to work in rhythm and blues bands and I went on the road with the road company of the musical, Hair. I think it was 1970. And then after that, I came back and worked with Bill Barron and Carlos Garnett and Art Blakey. I just stayed into it.

FJ: During the better part of the Seventies, you were the trumpet player of note in the free jazz movement.

OLU DARA: Well, to be honest, Fred, I had no interest in it at all. Musicians liked me and they hired me and it was nothing else at that period musically to do around this area. There was no jobs, no money. Everything was on the low end. Rhythm and blues was going locally and bebop was going locally and that was the only thing there and I was coaxed into playing with these musicians that migrated to New York from various areas of the country like Chicago, St. Louis, and L.A. and trumpeters wouldn't play with the so called avant-garde and so that was an opportunity for me to play, although I had never really listened to it or I had never experienced playing it. But once I was in it, it was just something to do and I could do it well and I did it until I got an opportunity to form my own band.

FJ: So you played not for your own fulfillment, but out of circumstance.

OLU DARA: I never really enjoyed it because it wasn't anything I grew up listening to. I mean, it was never really in my immediate environment. I just never did it. I never thought about the music. I didn't know it existed until I started meeting these musicians. You have to understand, Fred. I'm from a small town and these people are from large cities, urban areas, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles or whatever, so their music was really not in my life at all.

FJ: But you worked with free jazz heavies like David Murray and Henry Threadgill. Did they impart anything to you?

OLU DARA: I was a more experienced musician, I think, than they were. So I think I was the one giving (laughing).

FJ: Did you ever consider yourself as being a jazz musician?

OLU DARA: No, I never called myself that. I never considered myself that. I found out, just from observation that although I was known to play jazz, I played in the rhythm and blues group, Caribbean blues groups, African groups and all others, but they never gave me a name when I was playing with those groups. They never called me an African trumpeter or a rhythm and blues trumpeter. But when I played with, I think, the first jazz musician that I played with, all of the sudden, it was important to be called a jazz musician and develop a popularity. I never could figure that out or why they pick one music to be more important than another. That name was put on me. I used to laugh when they called me that. I said, "My God, I'm not a jazz musician at all." It never entered my mind. When I observed that situation, I saw the dichotomy. I saw the attitudes about music and what's important, what's not important, although, I felt that the other stuff I was playing was much more important than the jazz I was playing.

FJ: So who is Olu Dara?

OLU DARA: A musician/songwriter.

FJ: During your on and off spells in avant-garde, did you field offers to record as a leader?

OLU DARA: I got one offer in '77, when I first came across the water, I mean, across from Brooklyn. I did one concert and got a record date out of that. I recorded two full albums and I was basically doing what I'm doing now and those records never came out. After that, I didn't really think about recording after that. It was never anything that I was thinking about doing for myself anyway. Normally, I just recorded with other artists for survival, make a nickel and dime here just to support my family or whatever. I wasn't interested, after that first thing because my band, I had organized my band and we were very popular locally and semi-national. So we worked all the time. We worked dances, theaters, theater gigs, dance companies, we were always working and we were very popular. We would play all the clubs. And because I didn't have any records out, I played all the clubs and venues that musicians who may have had twenty records could not play. I felt fortunate so I didn't really think about recording because I was already satisfied with the band and the popularity of the band. We made a pretty good living for many years like that and I didn't get many opportunities during the early Eighties because they were really looking for me to record what they call avant-garde music or some forms of bebop, which was not my interest at all. Most of the record companies were basically interested in me doing that and they looked at my band like it was something out of the hills of Appalachia or something they're not interested in. To me, what they were really saying was that he is not sophisticated enough. Some did tell me that. They wanted more of a European element in the music like I thought the avant-garde was and the bebop. That's what they really were looking for, for documentation. I knew that I did not want to be known or represented like that because it wasn't me and I knew economically, it would not be feasible. And I got no enjoyment in it. I'm a smiling type of person and I stopped smiling when I played that kind of music, so I wanted to get as far away from that as I could and I finally did.

FJ: Your Atlantic debut, In the World: From Natchez to New York, was certainly a departure.

OLU DARA: Well, they had been coming to me for almost ten years.

FJ: To do an avant-garde record?

OLU DARA: No, they didn't say what. They were coming to me at that time, but we never really talked and they would call once or twice a year. The producer, Yves Beauvais, said to me one time, "Look, I'm going to keep calling. Do you mind?" I said, "Well, I'm not going to sign anything." And he said, "I'm going to keep calling anyway. Do you mind?" I said, "No, I don't mind." So one day, one of my sons called and my family and my friends and my sons, they pushed me to do something and I still refused. My son was on Columbia. He called. That's what really got my mind and ears perked up. I figured that it meant something.

FJ: For those not in the know, who is your son?

OLU DARA: His name is Nas. He's a very well known hip-hop artist.

FJ: You must be proud.

OLU DARA: I'm very proud of him. I think he's more proud of me than I am of him because I view him as my mentor. I really do because during the days I wanted to make my split from the so called avant-garde and I was pondering over what should I do because people were giving me problems and a lot of musicians and record people would say, "That stuff you play is not cool and you should play this other stuff." I was playing my music at home and my son would listen to my music and he would listen to the other stuff I was doing and he'd say, "Look, what you're doing is right." I talking about when he was seven or eight years old. "Mix all the things that you know in." This is what he said to me. He just reaffirmed what I was thinking all the time and what I was doing. Him being my son and being so young, I started to listen to him and he's the reason that I kept doing what I was doing because at one point I was thinking about not doing it anymore. He was the reason and that's why I consider him a mentor. He's very advanced musically and artistically.

FJ: Nas is one of hip-hop's superstars.

OLU DARA: Yes, he is. I'm very proud, but at the same time, I kind of figured it would happen.

FJ: What gave it away?

OLU DARA: The family, just the family. I know how our family runs. Each generation has done a different type of music and we've all been respected in our own thing. I'm just the first one to record. No, no, Nas recorded before I did. But we were the first ones to record, but we've always had great artists in our family from generations. So I expected my sons to follow suit to what they were doing for their time. He had quite a few records out. He had three or four records out before I recorded.

FJ: Those who are familiar with your work in free jazz expected In the World to be an avant-garde record.

OLU DARA: Yes, they did, not only the writers but the musicians too. Musicians were shocked. They still are today. They're speechless.

FJ: Did you get a good laugh?

OLU DARA: Yeah, I was laughing. (Laughing) I laughed all the time. I was in New Orleans a few months ago and Terence Blanchard, who I had met many years ago when he first came to New York. He's living in New Orleans now. He came and said, "Man, I came to hear that trumpet. I didn't know you could sing." I played maybe three notes on the trumpet all night (laughing). But he came to hear some trumpet (laughing). But it was cute. It was very cute. I had a lot of fun with that.

FJ: People shouldn't be so surprised since your roots were in the blues and African-American folk music.

OLU DARA: That is what surprises me also. I think what happens is that when you move to a large, urban area, people seem to dismiss, especially if you're in America, they dismiss Southern heritage, Mississippi heritage like that, as opposed to dismissing someone from Argentina or Jamaica or whatever. They'll see a Jamaican and say that he's going to play Jamaican music because he's from Jamaica. But in America, they don't know that we have regional music.

FJ: Obviously people were not familiar with your ability to sing, but you also played guitar on the album as well.

OLU DARA: Yeah, I've always had one around since I was a kid, but I've never really played guitar, conventional guitar with six strings. I always had one or two strings, sometimes three and that was it. I was playing with just one string, one string, plucking it or either with a slide and then eventually, I would go to two strings sometimes and then three strings. But that was something that I did on a personal level at home around friends. I never took that public. I never did plan on taking that public until I started doing more acting and writing plays. I would always have a guitar and singing the blues in theatrical productions. So people who knew me in the theater knew nothing about my trumpet playing or jazz world. That was something too. I had two lives. I had two or three lives. So I surprised the theater people with my horn playing and the knowledge of my jazz once they started reading the things about me and hearing more things and vice versa.

FJ: And somewhere in there, you found time to compose.

OLU DARA: Yeah, yeah, I compose music all the time. In the theater, I must have written, in the last twenty years or so, I must have written an average of one hundred songs a year that were done publicly around the country. I got a chance to see, almost every song I wrote, I got a chance to see it performed in each production I did.

FJ: How did you choose what songs would make it on the album?

OLU DARA: It wasn't difficult. What happened was that I wouldn't really choose anything. Once friends of mine knew I was making the album, they were requesting songs. They'd say, "Why don't you do this song? I always liked that song." Or either my producer, who would come around and hear those songs in theatrical productions, he suggested some songs he liked and a lot of songs I had written for one night or something and forget about it. But people would suggest these songs and that's what would happen. Some songs are over twenty years old. Some are brand new. Some I made up on the spot and the same with the new album. Some of the songs are twenty years old. Most all these songs were suggested to me. I never said, "I'm going to put this on my record." Most all of them were suggested other than the ones that I make up on the spot.

FJ: Having been quite familiar with your work in the avant-garde, where did this singing come from?

OLU DARA: I was just a guy who sang, not in the shower, but I'm a couch singer very quietly to myself when I'm playing the guitar or whatever. Or I would call myself a mental singer. I would sing to myself in my mind all the time. I never uttered a sound of hardly any volume up until I started playing with my band. And when I started my band years ago, I didn't plan to sing in the band because singing was a no, no back in those days. If you sang, it was like you would get funny looks from the musicians and everything. So I didn't sing. It was all instrumental. I just started singing one night just playing around and people came back the next night and wanted to hear me sing again and I didn't and they complained to the club owner. The club owner just made a remark. He said, "Those people came last night and they were really disappointed you didn't sing." I had forgotten that I had sang the night before. I was just messing around.

FJ: The new release, Neighborhoods, has you paired with Cassandra Wilson, whom you've collaborated with before.

OLU DARA: Yeah, I got a chance to return a favor and we've done a lot of things together, live and recording. We have a very close feeling.

FJ: Is Atlantic coming to bat for you and supporting a tour?

OLU DARA: Yeah, we will tour. We'll start in a week or so.

FJ: Do you like the term crossover?

OLU DARA: I like it if it is used in the right context. My music already has. It already has. I am able to play all types of venues, which I love. At the jazz festivals, I'm accepted there. At blues festivals, I'm accepted there. If there is a folk festival, I'm accepted there. If there is jam music, I'm accepted there and so I am able to play all these venues, which is very good. But more than crossing over, it is crossing back and forth, crossing up, crossing down. There is all kinds of stuff.

FJ: Having recorded some stellar sessions in the avant-garde, guested with your son, Nas, on some of his releases, and now, with a couple of your own dates, blurring the lines between blues and folk music, is there any idiom you would like to get your toes wet in?

OLU DARA: Yeah, I need time to do at least twenty more CDs (laughing), so I can get all these different genres that I really like and I'm well versed in and document those. I really do wish I could get to that point. My sons want me to do a hip-hop album.

FJ: Do it.

OLU DARA: Well, now that you've cosigned on that, Fred, I think I will do it now (laughing). Olu, the hip-hopper (laughing). We said it with a straight face, Fred.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and calls South Central home. Email him.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olu_Dara

Olu Dara

Olu Dara Jones (born Charles Jones III, January 12, 1941) is an American cornetist, guitarist, and singer.

Early life

Olu Dara was born Charles Jones III January 12, 1941, in Natchez, Mississippi.[1][2] His mother, Ella Mae, was born in 1911 in Canton, Mississippi.[2] His father, Charles Jones II, also born in Natchez,[2] was a travelling musician, and sang with The Melodiers, a vocal quartet with a guitarist.[3]

As a child, Dara took piano and clarinet lessons. He studied at Tennessee State University, initially a pre-med major, switching to music theory and composition.[3]

Career

From 1959 to 1964 he was a musician in the Navy, which he described as a priceless educational experience.[3]

In 1964, he moved to New York City and changed his name to Olu Dara,[4][5] which means "God is good" in the Yoruba language.[5] In the 1970s and '80s he played alongside David Murray, Henry Threadgill, Hamiet Bluiett, Don Pullen, Charles Brackeen, James Blood Ulmer, and Cassandra Wilson. He formed two bands, the Okra Orchestra and the Natchezsippi Dance Band.[1][4]

His first album, In the World: From Natchez to New York (1998), revealed another aspect of his musical personality: the leader and singer of a band immersed in African-American tradition, playing an eclectic mix of blues, jazz, and storytelling, with tinges of funk, African popular music, and reggae. His second album Neighborhoods, with guest appearances by Dr. John and Cassandra Wilson, followed in a similar vein.

Dara played on the album Illmatic (1994) by his son, rapper Nas, and on the song "Dance" (2002), also by Nas, and he sang on Nas's song "Bridging the Gap" (2004).[5]

Discography

As leader

- In the World: From Natchez to New York (Atlantic, 1998)

- Neighborhoods (Atlantic, 2001)

With Material

- Memory Serves (1981)

- The Third Power (1991)

As sideman

With Charles Brackeen

- 1987 Attainment (Silkheart)

- 1987 Worshippers Come Nigh (Silkheart)

With Rhys Chatham

- 1984 Factor X

- 1987 Die Donnergötter (The Thundergods)

With Carlos Garnett

- 1975 Let This Melody Ring On (Muse)

- 1977 Fire

With Corey Harris

- 2002 Downhome Sophisticate

- 2005 Daily Bread

With Craig Harris

- 1985 Tributes (OTC)

- 1999 Cold Sweat Plays J. B. (JMT)

With David Murray

- Flowers for Albert: The Complete Concert (India Navigation, 1976)

- Ming (Black Saint, 1980)

- Home (Black Saint, 1981)

- Live at Sweet Basil Volume 1 (Black Saint, 1984)

- Live at Sweet Basil Volume 2 (Black Saint, 1984)

- The Tip (DIW, 1995)

- Jug-A-Lug (DIW, 1995)

With Nas

- 1994 Illmatic

- 2002 God's Son

- 2004 Bridging the Gap

- 2004 Street's Disciple

With Jamaaladeen Tacuma

- 1983 Show Stopper

- 1984 Renaissance Man

With Henry Threadgill

With James Blood Ulmer

- Are You Glad to Be in America? (1980)

- Free Lancing (1981)

- No Escape from the Blues: The Electric Lady Sessions (2003)

With Cassandra Wilson

- 1987 Days Aweigh (JMT)

- 1993 Blue Light 'Til Dawn

- 1999 Traveling Miles

- 2002 Belly of the Sun

With others

- 1970 Journey to Air, Terumasa Hino

- 1970 Who Knows What Tomorrow's Gonna Bring?, Jack McDuff

- 1973 Ethnic Expressions, Roy Brooks

- 1973 Revelation, Doug Carn

- 1975 Heavy Spirits, Oliver Lake

- 1977 Endangered Species, Hamiet Bluiett

- 1978 Live at Moers Festival, Phillip Wilson

- 1980 Flat-Out Jump Suite, Julius Hemphill

- 1982 Flying Out, Cecil McBee

- 1982 Nots, Elliott Sharp

- 1983 Nona, Nona Hendryx

- 1985 The African Flower, James Newton

- 1985 The Sixth Sense, Don Pullen

- 1993 Deconstruction: Celluloid Recordings, Bill Laswell

- 1997 KC After Dark, Kansas City Band

- 1998 Empire Box, Tim Berne

- 1998 You Don't Know My Mind, Guy Davis

- 2002 Medicated Magic, Dirty Dozen Brass Band

- 2002 Trance Atlantic (Boom Bop II), Jean-Paul Bourelly

- 2003 Chinatown, The Be Good Tanyas

- 2007 The Harlem Experiment, The Harlem Experiment

- 2007 This Is Where You Wanna Be, The Brawner Brothers[6]

https://jazztimes.com/archives/olu-dara-mr-daras-neighborhood/

Olu Dara: Mr. Dara’s Neighborhood

by Tom Terrell

April 25, 2019

JazzTimes

Ridin’ the N train, Brooklyn to 42nd Street: Over and over again phrases like “Never open a wine before its time” and the Chambers Brothers’ chant “TIME!…TIME!…TIME!” bobbed and weaved inside my dome with Olu Dara’s Neighborhoods swerving in my ‘phones. Just tuning up for Olu’s gig at B.B. King’s Manhattan juke joint.

Surfacing in the neon-mad Disney/ Warner theme park that is now Times Square, I turned left and cracked up ’cause, in spite of the billion-dollar makeover, 42nd between 7th and 8th Avenue still feels, smells, breathes like the funky, funky Square of back-in-the-days. Fittingly, B.B. King’s is smack dab in the middle of this pimp ghost town. Downstairs, the spot is laid: wood-walled restaurant to the left, main room (room-width back bar, plush booths, banquettes, couches, tables down front) to the right. Can’t be more than 75 folks here and most of ’em don’t exactly reflect Olu’s multiculti audience demographic.

Five minutes after the shrimp Po’Boy sammich comes, Olu’s muted cornet ffrip-frraps the band (percussionist Massamba, guitarist Kwatei-Jones Quartey and bassist Alonzo Gardner) into a big foot-shuffling slice of “Okra.” Midway, Olu starts jew’s-harp twanging some harmonica then takes it all home with a playful chant (“I got po-tay-toes, snap pe-ees, corn…”).

One song told the crowd all they needed to know: Olu Dara-Afrobeats and jazz licks aside-is a straight-up down-home bluesman. The next tune’s (“Natchez Shopping Blues”) black-cat-moan-spooked Delta crawl closes the deelio. The house is rocking now; sounds like a full house. Now the fun begins. Forty-five solid minutes of repaving In the World: From Natchez to New York (his ’98 Atlantic solo debut). “Your Lips” jumps like soca, “Harlem Country Girl”‘s jazzy waltz skizzs into Miles-spaced, freestyle-talking blues (“Partying to Wilson Pickett and James Brown in Brooklyn/Going to the Bronx Zoo/All the animals in cages/I don’t like it”). This shit cooks! Less cornet or guitar, more into fiercely rocking the mic, Olu gives the band plenty of room to work things out. Like the way they do the funky-Meters-Afro-boogie-breakdown all over “Movie Show” (Neighborhoods) till it births a whole ‘nother song. “When I say ‘Break it down,’ I’m going on an adventure ’cause I don’t know what they’re gonna do and they don’t know what I’m gonna do,” chuckles Mr. D. “Usually when we do that, something happens, something drops out in space and you hear something you didn’t hear in the song before in the way we were playing.”

As he took in the well-deserved standing “o” after a funkadocious set-closing whiff of the new song “Herbman,” the full measure of Olu’s sartorial dapperness-chocolate-brown porkpie hat, honey-brown metallic-rust shirt/pants, bone-neutral socks, amber Italian loafers-elicited an involuntary “Lookin’ sharp!” During check-settling time, Olu shmoozed his way ’round the room: meeting and greeting, signing ‘grafs, laughing, answering questions. “We just having fun up here,” he says on the way to the dressing room. “We just trying to give everybody a good time, a party y’know?”

Olu Dara was born knee deep in the Delta-Natchez, Mississippi-in 1941. Blessed with an arts-nurturing extended family circle (lifelong music influence: his blues-crooning grandmother), raised up in a supportive, self-sufficient black community, suckled mind-body-soul 24/7 by the blues-enriched Delta-folk culture, young blood played his first gig at a women’s auxiliary club: nothing but solos; only been playing trumpet a few months. Olu was seven years old. Was it a single-bullet theory of musical destiny in full-effect, a promise of a dream, a rite of passage? Nope. The real truth is quintessential Olu. “I don’t like the horn; I never practice it. I just played it ’cause I was good at it,” muses O.D. “I started playing horn early ’cause the guy said, ‘Look here. Take this, blow it up like you do a balloon and here is the bridge to Duke Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady.”‘ I didn’t know who Duke Ellington was till I was grown ’cause we never listened to it.”

By high-school graduation, Olu was a working multi-instrumentalist, theater actor, painter, dancer, wood-art carver. He gave college a shot, then dropped out and joined the Navy. He figured his skills would get him a seat in the Navy band, four years of government-subsidized wood-shedding and a chance to jam with cats from Morocco to Trinidad-correct on all three counts. What he didn’t factor in was the nature of the beast: conformity. “I went to one class when I got in the Navy and the guy had an attitude with me ’cause he said I sound like Miles Davis,” laughs Olu. “I don’t think I hardly knew who Miles Davis was [in 1959], yaknowhutahmean? So, he was trying to teach me how to play the horn and I said ‘I don’t want to be in this little room with you.’ He tried to tell me I couldn’t play. And I said, ‘Who, who are you? I’ve been playin’ this way since I was seven years old. You ask what books did I study on? None.'”

Discharged in 1963, O.D. relocated to New York City. He wouldn’t play for eight years. “Guys like me don’t wind up in New York; we’re not even raised not to be around trees and flowers,” chuckles homeboy. “I got stranded in Brooklyn, hustlin’, doin’ this, doin’ that. I was like a foreigner. I’d just go out and listen to music. I’m glad that I didn’t come into New York saying I want to be a musician; I’m glad I didn’t do that. That really saved me because I would have had a certain tunnel vision into one thing. New York is a horn town. Down South, they’re not horn lovers; Midwest, they’re not horn lovers; Minneapolis ain’t horn lovers. Horn lovers are in New York City, period !”

One day in ’70, on a whim, Olu “bought a horn and started messing around, ’cause that was a sign of the times. You didn’t even have to work at that time ’cause there was so much money around during the Lindsay administration.” A year later-boom!-he’s touring the world with Art Blakey. It was a mismatch made in 15-minute heaven. “I didn’t grow up listening to jazz or playing it; when I got with Art Blakey I hadn’t played no bebop before-they thought I had,” says Olu. “To me it was very simple: we got 32 bars here, 16 bars here, and you’re going back and forth, back and forth. So it wasn’t like a thing that was very difficult, it was easy. It was too easy, though; it was too boring for me.” He resigned in early ’72.

From then till now Olu Dara has evolved into the ultimate inside-outside iconoclast in a town full of ’em. Roll call: ubiquitous catalyst in the ’70s jazz-loft underground; mentor to M-Base collective; composer/musical director of several August Wilson plays (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, The Piano Lesson); critically acclaimed collaborations with choreographer Dianne McIntyre; founder/leader of the legendary Okra Orchestra and still-thriving Natchezsippi Band (20 years); father/mentor of hip-hop star Nas (that’s Olu lacing some raspy-edged cornet all up in Nas’ Illmatic track “Life’s a Bitch”); bum-rusher of most of ’98’s best-of polls for In the World.