AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2016/04/bill-dixon-1925-2010-legendary-and.html

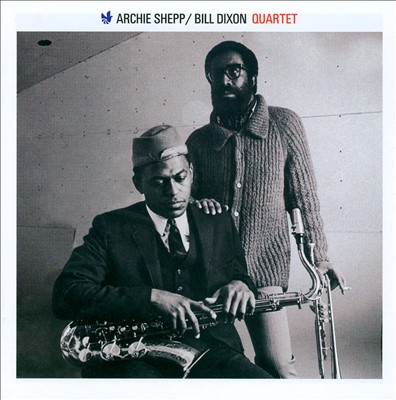

PHOTO: BILL DIXON (1925-2010)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bill-dixon-mn0000764354/biography

Bill Dixon

(1925-2010)

Biography by Chris Kelsey

One of the seminal free jazz figures, Bill Dixon made his mark as a player, organizer, and educator in a career that spanned more than 50 years. Dixon was a jaggedly lyrical trumpeter -- his delivery was as vocalic as that of any free jazz trumpeter, except perhaps Lester Bowie. As an improviser, he was somewhat similar in temperament to Ornette Coleman, yet his compositional style differed greatly from the altoist. Dixon's work featured open space, wide intervals that did not imply a specific key or mode, and dark backdrops owing to the use of two or more double bassists. His art was eminently thoughtful even as it was viscerally exciting.

Dixon grew up in New York City. His first studies were in painting. He didn't become a musician until he was discharged from the Army following World War II. He met Cecil Taylor in 1951 and the two began playing together, along with other likeminded young musicians. In the early '60s, he formed a quartet with saxophonist Archie Shepp. The band recorded the self-titled Archie Shepp-Bill Dixon Quartet LP for Savoy in 1962 (Dixon was briefly the artistic director in charge of jazz for the label). In 1964, Dixon organized the October Revolution in Jazz, a festival of new music held at the Cellar Cafe in Manhattan. About 40 groups played, including the cream of the era's free jazz crop. Out of this grew the Jazz Composer's Guild, a musician's cooperative founded in 1964 that included Dixon, Shepp, Roswell Rudd, Cecil Taylor, Paul Bley, and Carla Bley, among others. In 1967 he recorded an album of his music for RCA. Also that year, he founded the Free Conservatory of the University of the Streets, a music education program for inner-city youth in New York. Beginning in 1968, Dixon taught at Bennington College in Vermont. He was a visiting faculty member at the University of Wisconsin in 1971-1972, then returned to Bennington, where in 1973 he founded the Black Music Division. At Bennington, Dixon mentored a number of contemporary free jazz musicians, including alto saxophonist Marco Eneidi and drummer Jackson Krall.

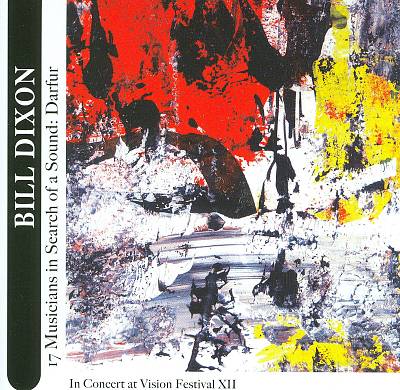

Dixon remained at Bennington until his retirement from teaching in 1996. In the years to follow, he conducted workshops and master classes around the world. A collection of his work from 1970 to 1976 was made available by the Cadence label, and from 1980 until the close of the 20th century he recorded and performed, more or less infrequently, for Soul Note. After the turn of the millennium, Dixon turned his attention to the genocide occurring in Sudan's Darfur region with 17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur, recorded live at New York City’s Vision Festival in June 2007 and released by AUM Fidelity the following year; 2008 also saw the Thrill Jockey label release of Bill Dixon with Exploding Star Orchestra, featuring Dixon with cornetist Rob Mazurek’s 13-piece Chicago-based experimental ensemble. Ill health subsequently restricted Dixon's performing schedule; however, he did make his last concert appearance (entitled Tapestries for Small Orchestra) on May 22, 2010 at the Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville in Victoriaville, Quebec. Less than a month later, on the night of June 15, 2010, Bill Dixon died in his sleep at home in North Bennington, Vermont at the age of 84.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/bill-dixon-excerpts-from-vade-mecum-bill-dixon-by-aaj-staff

Bill Dixon

A mentor to countless musicians, through both his teaching and his role as a producer for Savoy Records, Dixon turned his focus to education in the late 1960’s, serving for nearly 30 years on the faculty at the prestigious Bennington College, where he founded the historic Black Music Division in 1973.

(Originally posted on June 23, 2010):

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

MILFORD GRAVES: DRUMS

AT THE VILLAGE GATE

NYC, MAY 27, 1984

by Kofi Natambu

Luminosity's glare

fierce timbre vowels that

pierce invisible shields our pores

breathing in slivers of light

This compelling lure its open space

hidden creases in the swollen zone of

Sound

Streaking hearts trembling the fading distance that raises thought (THOTH?)from feelings

This bursting time implosion how does it

explode the vertical void that rules the AIR?

O gigantic creeping light seeping thru the earth its howling language a moving source of Color

our minds' most transparent desires

Spiralling tears of motion

a burning spectrum peering across colors' Dominion(s)

seeking blueness in an Ocean of Red

seeking blueness in an Ocean of Red

a slittering rippling sliding invocation: Tonalities hieroglyphic

Melodic holograms Now you FEEL the sound (now you HERE it!)

Blastic splutters rappling contexts

And what about the Night notes crashed thru colossal windows & glowing stones

found a place to rest amidst the huge soothing clatter?

Another pace/race breaks expectations' web

A brilliant shining this rampaging joy that cuts down all the Pain into ectastic children of Memory: the Souls efflorescence

How awful it all is

How AWE FULL!

Flames flickering inside the Glare, luminosity's not-so-sullen-secret as we dance in the wake of bestial surprises

Stutter past sidewalks dissolving in the blazing rain a staggering encounter this

Monstrous Joy that slips a stance

Crooked guffaws split lazy rhythmic questions

its nonreferential power that wants nothing especially its Self

This glance this chance this dance this prance this lance this stance that charges charges that charges charges admission to everyone at once

Inconsequential stirrings in the Heart

A rumbling MOJO expanding the leafy village between our Ears fears melting down like rainfall searing the darkness

This is the energy we call Revelation

This is the Life we call

Free…………………………………………………………………………….

Poem by Kofi Natambu

From: The Melody Never Stops

Past Tents Press, 1991

Biography

Born: October 5, 1925 | Died: June 16, 2010

Bill Dixon has been a driving force in the advancement of contemporary American Black Music for more than 45 years. His pioneering work as a musician and organizer in the early 1960’s helped lay the foundation for today’s creative improvised music scene in New York and beyond. In 1964, he founded the all-star artists collective, the Jazz Composers’ Guild, and produced and organized The October Revolution in Jazz, an unprecedented New York festival that helped put the so-called “new thing” on the cultural map.

A mentor to countless musicians, through both his teaching and his role as a producer for Savoy Records, Dixon turned his focus to education in the late 1960’s, serving for nearly 30 years on the faculty at the prestigious Bennington College, where he founded the historic Black Music Division in 1973.

With the notable exception of Cecil Taylor’s Conquistador (Blue Note), Dixon has recorded almost exclusively as a leader since 1962, most frequently for the Soul Note label in the 1980’s and 90’s. Still a prolific composer at age 82, his work as a composer and improvisor can also be heard on the critically acclaimed February 2008 CD, Bill Dixon with the Exploding Star Orchestra (Thrill Jockey), and in July 2008 he recorded a new collection of original music with an all-star nonet for the Firehouse 12 label.

Press Quotes

17 Musicians in Search of a Sound is pure Dixon, massive in scale and rigorous in execution...this is not a mere concert souvenir, but a significant statement. Dixon’s music is about the process of its becoming; while its expansions into dense, eventful fanfares and contractions into hushed, detailed dialogues may be scripted, the sound of the music is not...as group improvisations go, this one is remarkable for its poise and balance....it’s about great players subsuming their identities into an ensemble.

...Dixon has fashioned a work around which new formal paradigms will need to be constructed. Dixon’s music explodes category: it is neither free nor through-composed, though elements of both approaches are often discernible. I hope this fine addition to his discography, coupled with a renewed interest in his work, will allow more of Dixon’s orchestral compositions to be performed by equally sympathetic interpreters.

...Dixon opens up space and the musicians play it.

...the process of searching for a sound, both as an individual musician, or as a composer, is an ongoing process that leads to the creation of a certain type of music palpably, viscerally distinguishable from music that does not. Bill Dixon is nothing short of a master when it comes to this concept of sound, and at his age and stature is unique in his ability to offer us an incredibly refined vision of this different approach to sound and music.

The 13-part suite creates an ebb-and-flow effect, with the reeds and horns surging by turns amid throbbing drum rolls and calmly snaking solo lines. The work's centerpiece, the 23-minute “Sinopia,” is where Dixon best makes his presence felt as something other than conductor. It leaves room for some intimate dialogues between instrumentalists, but there's no missing the leader's entrance. With puckered blurts, upper-register trills, and rubbery bleats -- most of them enhanced with ghostly delay -- he stalks across the landscape, his utterances punctuating the arrangement like shadow puppets dancing across an illuminated screen. And even when the piece is more geared toward an ensemble sound -- which, to be fair, is most of the time -- Dixon shines brightly with his mastery of texture.

Articles [VIEW ALL]

PLEASE CLICK ON THE FOLLOWING LINKS:

Artist Profiles

Bill Dixon: In Rehearsal, In Performance

Bill Dixon: The Morality of Improvisation

CD/LP Review

Tapestries for Small Orchestra

17 Musicians in Search Of A Sound: Darfur

17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur

17 Musicians In Search Of A Sound: Darfur

Bill Dixon With Exploding Star Orchestra

Bill Dixon With Exploding Star Orchestra

Berlin Abbozzi

Berlin Abbozzi

Berlin Abbozzi

Papyrus Volume I

Extended Analysis:

Bill Dixon: Tapestries for Small Orchestra

In the Artist's Own Words:

Bill Dixon: Excerpts from Vade Mecum

Interviews:

Bill Dixon: In Medias Res

Megaphone:

Bill Dixon: The Benefits of the Struggle

Total Articles: 16

News [ MORE - POST ]

Remembering Bill Dixon: 1925-2010

Bill and Fred

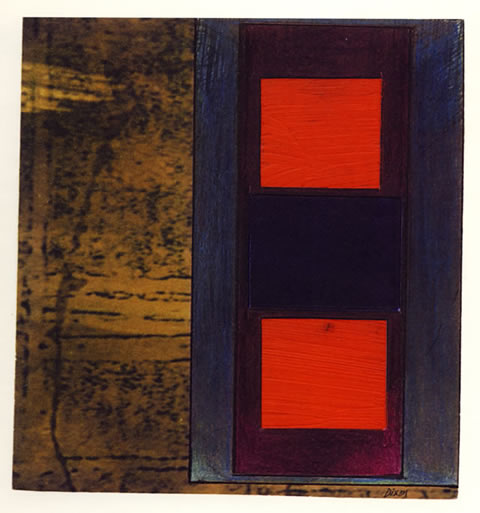

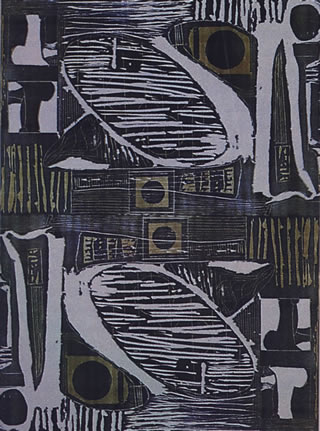

Bill Dixon Paintings, Lithographs and Drawings Now Featured at...

Trumpeter Bill Dixon Interviewed at AAJ

Bill Dixon:17 Musicians in Search of Sound: Darfur

Bill Dixon with Exploding Star Orchestra

Bill Dixon's New Orchestral CD Released Today on AUM Fidelity

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/news.php?id=58430

Trumpeter and composer Bill Dixon died June 16th at his home in North Bennington, Vermont after a two-year illness. He was 84 years old.

Dixon was a revered and idiosyncratic figure in the avant-garde of Jazz music, and a creative force who strived at all times to place the music in ever more respectful circumstances. Dixon developed an often controversial profile as an outspoken and articulate defender of musicians' rights as artists, and specifically the challenges to Black music as a contender in the culture and society of the United States. His music is known for a dark, poignant, pan-tonal abstraction that remains lyrical without relying on songs or the conventions of Jazz music-making. Through five decades as a recording artist, Dixon's music has developed a loyal worldwide following.

As a musical stylist and educator, Dixon was the progenitor of an often reserved composition and playing approach that stood in contradistinction to the trends prevailing in the avant-garde in Jazz since the Sixties. He steered an influential through short-lived collective-bargaining movement in New York in 1964-65, the Jazz composers' Guild. Under Dixon's leadership, the Guild crafted a stance to preserve the artistic self-determination of Guild membership. Though he lived in Vermont for most of the last four decades, playing only occasionally in New York and in the US altogether, Dixon remained a leader and doyen for musicians of successive generations in a diaspora of alumni of his teaching and ensembles.

The legacy of Dixon's progressive organizing activities in the music often overshadow the impact of his own music-making. Dixon emerged as a composer and bandleader in what can fairly be called a second wave of the New York avant-garde. Dixon's legacy of ensemble records (1966, 2007, 2009) frames an unparalleled body of solo music for trumpet (1970-76, mainly) and a subsequent series of small ensemble recordings (1980-1995) that stand apart in texture, instrumentation, personnel, and orientation from most of the numerous records of the period by Dixon's contemporaries.

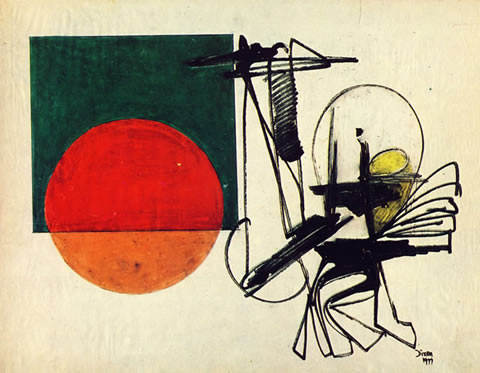

Born William Robert Dixon on October 5, 1925, he was the son of William L. Dixon and Louise Wade. His family transplanted to Harlem at the height of the depression from Nantucket, Massachusetts where Dixon was born. An early aptitude in realistic drawing led him to advanced studies in commercial art during and after high school, well before music became a serious interest. (He was also acclaimed in a group and solo shows of paintings prior to serious recognition of his music, and he was painting, drawing and creating lithographs to the end of his life). Dixon enlisted in the U.S. Army during WWII and served in Germany at the close of European theater.

Bill Dixon's deliberate study of music began at the Hartnett Conservatory of music in the mid-1940s. His journeyman years as a Jazz trumpet player in the 50s involved activity as a sideman in an array of entertainment and rehearsal projects. Daytime employment as an international civil servant at the UN Secretariat, Dixon also turned to musical advantage. He founded the United Nations Jazz Society in 1959. He worked in the same period to establish the coffee houses of Greenwich Village as a formal and legitimate venue for presenting progressive music, an early manifestation of the spirit that fed the formation of the Jazz Composers' Guild.

Bill Dixon will perhaps always be remembered for his organization of a concert series to present the new music, the October Revolution in Jazz of October 1-4, 1964, at the Cellar Cafe on west 91st Street. Though literally digested by only a handful of eyewitnesses, the concert series focused significant critical attention on the undergrowth of otherwise unrecognized creative musicians, many of whom, including Dixon, shortly would show forth as the newest voices of the new music of the Sixties.

Starting in 1966, Dixon entered a fruitful collaborative partnership with the dancer/choreographer Judith Dunn, whose background lay in the Cunningham and Judson schools. The collaboration with Dunn led Dixon to join the faculty at Bennington College where she taught in the Dance department, and Dixon pushed for the creation of the Black Music Division, a phalanx of the school's music teaching that had its own faculty, student body, and orientation. Active officially from 1975 until 1985, the program was a prototype of a kind of college-level music study that has flowered only haphazardly since, basing itself in the aesthetics and praxis of avant-garde music-making.

Dixon is remembered by many of his students as a powerful and charismatic teacher who adroitly factored student musicians at various levels of skill and development into classes and his own ensemble pieces. Within the first few years at Bennington, it became the norm for Dixon to design individual and group exercises artistically meaningful enough to become part of the compositions he developed through a term's work.

Dixon retired from teaching in 1995 and continued to perform and record, chiefly in Europe. His last years saw a dramatic increase in the frequency of his U.S. appearances, and, since 2008, in U.S.-released recordings of his works for ensembles.

Dixon is survived by his longtime partner Sharon Vogel of North Bennington, a daughter Claudia Dixon of Phoenix, Arizona and a son William R. Dixon II of New York City. He also leaves two grandchildren.

A memorial celebration of Bill Dixon's life and work will be held in New York City at a later date.

Ben Young is the author of Dixonia: A Bio-Discography of Bill Dixon (Greenwood Press, 1998).

RIP Experimental Jazz Trumpeter Bill Dixon

From his publicist comes the news that Bill Dixon, the experimental jazz trumpeter and composer, died in his sleep last night at his home in North Bennington, Vt. He was 84 years old.

Dixon was a professional musician for over 60 years and one of the most reliable exploratory voices in jazz—a word he hated. His music, in (very) large and small ensembles as well as solo work and collaborations, pushed continually outward, both artistically and politically; Dixon was the organizer of 1964’s infamous festival “The October Revolution in Jazz,” and the founder of the influential early collective the Jazz Composers Guild. He continued to defy convention over nearly three decades as an educator, making his legacy immense.

William Robert Dixon was born on Nantucket Island, Mass., in 1925, and grew up in Harlem. His family was nonmusical, but Dixon fell in love with the trumpet after seeing a Louis Armstrong concert as a child. He bought his first trumpet in high school, then attended the Hartnette Conservatory of Music in Manhattan after serving in the Army during the closing months of World War II. He began his career after graduating from Hartnette in 1951, but also began composing on his own; at the same time, however, he worked a day job at the United Nations, where in 1958 he founded a listening and discussion group for the diplomats, the UN Jazz Society.

Throughout the 1960s Dixon established himself in collaborations with forward thinkers Archie Shepp, Cecil Taylor, and avant-garde dancer/choreographer Judith Dunn. He also gained a reputation as a composer and bandleader in his own right, including a band co-led with Shepp and a large-ensemble recording, 1967’s Intents and Purposes, commonly regarded as his masterpiece.

In 1968 Dixon took a teaching position at Bennington College in Vermont. He remained affiliated with Bennington for 28 years, gaining tenure and founding and chairing the school’s Black Music Division for 19 years. Meanwhile, however, his recording and performing (as well as painting, examples of which often adorned his album covers) continued unabated, including a remarkably consistent string of albums recorded for the Italian Soul Note label in the 1980s and ’90s. His most recent recordings included two large-ensemble pieces, 2007’s 17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur and 2008’s Bill Dixon with Exploding Star Orchestra, a collaboration with Chicago post-rocker Rob Mazurek. Shortly after the release of the latter, however, Dixon withdrew from performance due to illness, which persisted until his death last night.

He is survived by his longtime partner Sharon Vogel and two children.

http://www.improvisedcommunications.com/blog/2010/06/17/dixon-obit/

Bill Dixon: The Official Obituary (June 17, 2010)

Bill Dixon’s estate has released this official obituary written by Ben Young, author of Dixonia: A Bio-Discography of Bill Dixon (Greenwood Press, 1998).

Trumpeter and composer Bill Dixon died June 16th at his home in North Bennington, Vermont after a two-year illness. He was 84 years old.

Dixon was a revered and idiosyncratic figure in the avant-garde of Jazz music, and a creative force who strived at all times to place the music in ever more respectful circumstances. Dixon developed an often controversial profile as an outspoken and articulate defender of musicians’ rights as artists, and specifically the challenges to Black music as a contender in the culture and society of the United States. His music is known for a dark, poignant, pan-tonal abstraction that remains lyrical without relying on songs or the conventions of Jazz music-making. Through five decades as a recording artist, Dixon’s music has developed a loyal worldwide following.

As a musical stylist and educator, Dixon was the progenitor of an often reserved composition and playing approach that stood in contradistinction to the trends prevailing in the avant-garde in Jazz since the Sixties. He steered an influential through short-lived collective-bargaining movement in New York in 1964–65, the Jazz Composers’ Guild. Under Dixon’s leadership, the Guild crafted a stance to preserve the artistic self-determination of Guild membership. Though he lived in Vermont for most of the last four decades, playing only occasionally in New York and in the U.S. altogether, Dixon remained a leader and doyen for musicians of successive generations in a diaspora of alumni of his teaching and ensembles.

The legacy of Dixon’s progressive organizing activities in the music often overshadow the impact of his own music-making. Dixon emerged as a composer and bandleader in what can fairly be called a second wave of the New York avant-garde. Dixon’s legacy of ensemble records (1966, 2007, 2009) frames an unparalleled body of solo music for trumpet (1970 –76, mainly) and a subsequent series of small ensemble recordings (1980–1995) that stand apart in texture, instrumentation, personnel, and orientation from most of the numerous records of the period by Dixon’s contemporaries.

Born William Robert Dixon on October 5, 1925, he was the son of William L. Dixon and Louise Wade. His family transplanted to Harlem at the height of the depression from Nantucket, Massachusetts where Dixon was born. An early aptitude in realistic drawing led him to advanced studies in commercial art during and after high school, well before music became a serious interest. (He was also acclaimed in a group and solo shows of paintings prior to serious recognition of his music, and he was painting, drawing and creating lithographs to the end of his life). Dixon enlisted in the U.S. Army during WWII and served in Germany at the close of European theater.

Bill Dixon’s deliberate study of music began at the Hartnett Conservatory of music in the mid-1940s. His journeyman years as a Jazz trumpet player in the 50s involved activity as a sideman in an array of entertainment and rehearsal projects. Daytime employment as an international civil servant at the UN Secretariat, Dixon also turned to musical advantage. He founded the United Nations Jazz Society in 1959. He worked in the same period to establish the coffee houses of Greenwich Village as a formal and legitimate venue for presenting progressive music, an early manifestation of the spirit that fed the formation of the Jazz Composers’ Guild.

Bill Dixon will perhaps always be remembered for his organization of a concert series to present the new music, the October Revolution in Jazz of October 1–4, 1964, at the Cellar Cafe on West 91st Street. Though literally digested by only a handful of eyewitnesses, the concert series focused significant critical attention on the undergrowth of otherwise unrecognized creative musicians, many of whom, including Dixon, shortly would show forth as the newest voices of the new music of the Sixties.

Starting in 1966, Dixon entered a fruitful collaborative partnership with the dancer/choreographer Judith Dunn, whose background lay in the Cunningham and Judson schools. The collaboration with Dunn led Dixon to join the faculty at Bennington College where she taught in the Dance department, and Dixon pushed for the creation of the Black Music Division, a phalanx of the school’s music teaching that had its own faculty, student body, and orientation. Active officially from 1975 until 1985, the program was a prototype of a kind of college-level music study that has flowered only haphazardly since, basing itself in the aesthetics and praxis of avant-garde music-making.

Dixon is remembered by many of his students as a powerful and charismatic teacher who adroitly factored student musicians at various levels of skill and development into classes and his own ensemble pieces. Within the first few years at Bennington, it became the norm for Dixon to design individual and group exercises artistically meaningful enough to become part of the compositions he developed through a term’s work.

Dixon retired from teaching in 1995 and continued to perform and record, chiefly in Europe. His last years saw a dramatic increase in the frequency of his U.S. appearances, and, since 2008, in U.S.-released recordings of his works for ensembles.

Dixon is survived by his longtime partner Sharon Vogel of North Bennington, a daughter Claudia Dixon of Phoenix, Arizona and a son William R. Dixon II of New York City. He also leaves two grandchildren.

A memorial celebration of Bill Dixon’s life and work will be held in New York City at a later date.

Bill Dixon - Live At Newport Jazz Festival 1966:

The world's greatest print and online music magazine. Independent since 1982

Bill Dixon interview audio

Hear Phil Freeman's full interview with Bill Dixon, on tape:

| Bill Dixon interview part one | 0:06:03 |

| Bill Dixon interview part two | 0:04:37 |

| Bill Dixon interview part three | 0:06:58 |

| Bill Dixon interview part four | 0:07:27 |

| Bill Dixon interview part five | 0:12:07 |

| Bill Dixon interview part six | 0:09:52 |

| Bill Dixon interview part seven | 0:04:04 |

| Bill Dixon interview part eight | 0:04:55 |

| Bill Dixon interview part nine | 0:06:45 |

| Bill Dixon interview part ten | 0:09:10 |

| Bill Dixon interview part eleven | 0:04:50 |

Listen to the entire audio of Phil Freeman's interview with Bill Dixon including material which never made it into the printed piece. The interview is divided into individual Question and Answer segments, totalling 75 minutes of interview time.

In the teaser trailer for last year's Tapestries for Small Orchestra, Bill Dixon said, "If you told me you couldn't do something in music, that was the thing I tried to do to prove you wrong."

And he always did.

With Dixon, music wasn't so much something to be conquered, but instead a beautiful problem to solve. Perhaps this approach came from his background in painting. Even as he began his musical journey later in his 20s, he sought a trumpet sound in broad, abstract strokes. While little recorded output exists from these early stages, co-led releases with Archie Shepp and an appearance on Cecil Taylor's Conquistador! (1966) are crucial pieces to jazz history.

Spending most of his time teaching at Bennington College in the '70s (where he taught until 1995), Dixon re-emerged to the recording world during the oft-ignored development of avant-jazz in the 1980s. Dixon always worked well in isolation, but what came challenged modern music at large. The improvised compositions heard on the two-volumed In Italy and later Vade Mecum were seemingly formless, never spurred on by the wild rhythm sections that lit a fire under jazz during the dawn of the New Thing. Instead, these pieces unfolded slowly, creeping along like some surreal Italian horror film, full of breathy yet colorful sound.

In 2005, this sound changed the way I thought about space.

At the time, I was still relatively green to avant-garde jazz, attracted to its fire and spontaneous invention. Eager to experience this music live — Athens, Ga., isn't exactly a hot bed of improv — my friend Mitch and I flew up to New York City for Vision Festival X.

In the midst of much raucous exploration, there was the Bill Dixon Quintet, performing what he then announced as a "work in progress." The shape was long and vacuous — Dixon's spits, gargles and abstract kinds of blues echoed into space. It was a language that spoke oceanic depth, a trumpet that could mimic a Wagnerian bow across a double bass. The composition's picture never quite revealed itself until the eureka moment hours, or even years, later.

A relentless innovator, educator and trumpet linguist, Dixon has died at the age of 84. He passed away in his sleep Tuesday night at his longtime home in North Bennington, Vt., after a two-year illness.

Thankfully, Dixon was very active in the latter part of this decade, particularly taking a shining to younger sound explorers like cornetist Taylor Ho Bynum. In the liner notes to Tapestries for Small Orchestra, Bynum writes that instead of following the forward momentum of his contemporaries, Dixon "[stopped] the clock and [turned] his gaze inward, towards the infinite potential of the existing moment rather than the moment to come."

Somewhere in the celestial sound space, Dixon's moments will echo forever.

More Bill Dixon remembrances: Clifford Allen, Taylor Ho Bynum, official obituary by Ben Young.

Photo: Stephen Albahari

Trumpeter Bill Dixon didn’t record much between 1966 and 1980. Having taken a position at Bennington College in Vermont, where he created the Black Music Division, he was focused on teaching during some of jazz’s most adventurous — if commercially parlous — years. He taught at Bennington from 1968 to 1995, and from 1970 to 1976 in particular was, in his own words, “in total isolation from the market places of this music.” Much later on, he released several CDs’ worth of solo explorations in the Odyssey box set, but by then he’d already re-established his reputation as an avant-garde jazz composer and conceptualist without peer, through a series of superb releases on the Soul Note label.

In 1981, though, another Italian label, Fore, released two LPs’ worth of Dixon’s music, recorded during that Seventies interregnum. Considerations 1 and 2 gather tracks recorded between 1972 and 1976. Some are solo pieces, a few feature small groups, and one is performed with an orchestra. All display the Dixon voice, with its fixation on open space, unusual intervals and juxtapositions, and disinterest in conventional rhythm.

Considerations 1 begins with the 12-minute “Places and Things,” a drumless trio featuring Dixon on trumpet, Steve Horenstein on tenor saxophone, and Alan Silva on bass. It’s a portion of a larger work, and was recorded in Paris, where the trumpeter had gone for a festival. The bassist is by far the most prominent and dominant voice; it often seems as if Dixon in particular is accompanying him, emitting long, slow tones that seem to whisper to a halt, as Silva bounces along joyfully and emphatically. The next two pieces, “Long Alone Song” and “Shrike,” are solo recordings from a studio at Bennington; both can also be found on Odyssey.

The album’s second side features another long trio piece, “Pages,” on which Horenstein reappears, Henry Letchner is on drums, and Dixon plays both trumpet and piano. The saxophonist’s playing is tender and romantic in the manner of Dexter Gordon or even Houston Person, and Dixon backs him with soft balladry before stepping away from the keyboard. When he picks up the trumpet, he begins to sputter and squeal, as was his wont, and Letchner enters, tumbling across the kit and gradually building up an almost tribal beat. Then Horenstein is heard again, unaccompanied; Dixon gets another turn, squawking and whimpering into what seem like two different microphones, with Letchner subtle behind him. Finally, Dixon returns to the piano for a romantic duo with the saxophonist. At no point do all three men play together.

Considerations 2 begins with a 14-second solo spurt called “Webern”; that’s followed by “Orchestra Piece,” recorded at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, in 1972. The piece is somewhat static — there’s no dominant melody or sense of progress, though a hand-held shaker provides accents if not rhythm. The orchestra hovers behind Dixon like a cloud as he takes a slow, languorous solo; occasionally they rise up, buzzing like hornets.

A long duo with Letchner, somewhat more aggressive than their work together on “Pages,” ends the first side and kicks off the second. (It fades out, then fades back in.) The album concludes with “Sequences,” a nearly 13-minute piece featuring Jim Tifft on trumpet, Jeff Hoyer on trombone, Horenstein on tenor sax, Jay Ash on baritone sax, and Chris Billias on percussion. Like the orchestral piece on the first side, it was recorded in performance in Wisconsin, and it has a similarly cloudy quality to start with, with the horns mostly massing behind Dixon like a Greek chorus of moaning ghosts, as he solos. But then Hoyer begins to repeat a few notes obsessively, and the saxes do something similar-but-different behind him, punctuated occasionally by a quick fluttery fanfare. Things get really exciting in the second half, when the saxes erupt in a staccato, romping-and-farting riff-storm like something the World Saxophone Quartet might play, as Billias switches from shaker to gamelan-like percussion. This might be the least “Dixonian” piece in the trumpeter’s discography. It almost rocks.

The two Considerations LPs have never been reissued on vinyl or CD; they’re not on any streaming service; and they’re not that easy to come by. Some enterprising soul should absolutely find the rights (and the tapes) and get them back out there, though, because the music is extraordinary and beautiful and 100% worth hearing for all Bill Dixon fans and anyone with an ear for adventurous, creative music.

https://taylorhobynum.com/bill-dixon-the-essence-of-a-sound-and-the-infinity-of-a-moment/

Bill Dixon: The Essence of a Sound and the Infinity of a Moment

My liner notes for Bill Dixon’s Tapestries for Small Orchestra (Firehouse 12, 2009)

The music of Bill Dixon maintains such a powerful flavor, it is one of those things where you inevitably remember the first time you taste it. For me, it was his mid-career landmark recording November 1981. Within the one minute and twenty six seconds of Webern, the opening track, I realized I had to completely rethink the possibilities of the trumpet as an improvising instrument. By the end of the album, I realized I had to examine my assumptions about the nature of creative music in general. For Dixon’s music does not adhere to the common practice of any established musical genre, be it “jazz”, “contemporary classical”, “avant-garde”, or what-have-you. While drawing upon all of these rich traditions and more, he has established his own set of rules and principles, creating a wholly individualistic canon over the course of his extraordinary career.

Bill Dixon came to music relatively late in life, in his early twenties, after training as a visual artist. From the beginning, Dixon had an advanced sense of what he wanted to accomplish in the medium, doggedly pursuing his own interests rather than following the paths others might prescribe for a more traditional student. In the ensuing 60 years, these instincts have naturally evolved and been consciously refined into an inimitable sound world. At an age where some artists might coast on a lifetime of accomplishments, Dixon’s work continues unabated and with unceasing vibrancy; the last few years have seen the exceptional orchestral recordings of Exploding Star Orchestra and 17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur. This activity culminates in Tapestries for Small Orchestra, with two hours of music and a documentary film culled from a multi-day residency with a handpicked mid-sized ensemble at the Firehouse 12 Studios in New Haven CT.

One of the exciting aspects of Tapestries is the insight it allows into Dixon’s process and the way it illuminates core structures of Dixon’s musical DNA. Ever since that first, sharp bite of November 1981 years ago, I have endeavored to gain some understanding of his music. After years of focused listening, a treasured handful of performance opportunities, and occasional conversations with the maestro, participation in this project clarified some of my rough impressions to the extent that I feel comfortable articulating them. Of course this just scratches the surface; I would recommend the interested listener search out the more detailed and scholarly research of Andrew Raffo Dewar, Ben Young, and Stanley Zappa, among many others, in addition to reading Dixon’s own writings.

There is a revealing moment in the documentary where Dixon discusses his frustration with composition teachers insisting one must never double the third. He was dissatisfied with traditional pedagogy presenting rules without taking the time to explain why. Dixon took the time to learn the “rules” of traditional music-making (in fact, he spent five years in conservatory study). However, he also learned to reject dogma that impeded the trajectory of his personal creative journey. He went on to discover doubling the third produces “one of the most beautiful sounds in music,” but it is so strong it changes the nature of the chord. For his own music, Dixon was not interested in the functionality of the harmony; he cared about what kind of sound that assemblage of notes created, not what it was supposed to lead to.

The most celebrated musical breakthroughs of the 20th century, from Schoenberg to Parker, tended to involve harmonic innovations. (Not coincidentally, also the easiest concepts for institutions to promulgate through the kind of simplistic definitions Dixon rebelled against.) Even amongst Dixon’s peers in the early 1960s like Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, and Albert Ayler, the effort to explore, subvert, or explode harmonic conventions remained a primary motivation. However, for Dixon, pushing against the constraints of harmony never seemed to be a motivating factor; instead, his consistent mission seemed to be asserting the primacy of sound itself.

In much of Dixon’s music, vertical harmony is not about moving towards (or away from) any tonal resolution, but about a distinct sonic experience existing in its own space and time. So much music is about “getting somewhere;” from the basic principles of the sonata form to impassioned free jazz improvisations leading to inevitable climaxes. But Dixon was unusual among his ‘60s contemporaries for avoiding this need for forward momentum; rather, he stops the clock, and turns his gaze inwards, towards the infinite potential of the existing moment, rather than the moment to come. His music acts like a microscope of time, peering in at the atoms of a suspended cell and the universe of activity contained therein. This sense of timelessness has always been one of his hallmarks, and allows him to explore the extremes of duration like few other artists. Dixon’s compositions might be thirty seconds or thirty minutes, but the seconds last an infinity, and the half-hour passes in a single breath.

Listen to the album’s title track, Tapestries, as an example. While the low-end instruments (cello, contrabass clarinet, acoustic bass) bubble with ceaseless motion, the brass remains wholly unperturbed, resounding slowly evolving harmonic clusters. (It is somewhat reminiscent of Charles Ives’ Unanswered Question, another revolutionary American master who managed to capture the feeling of eternity.) Again, where free jazz cliché would draw the horns into the temptations of the rhythmic excitement, Dixon holds them back, creating an exquisite tension that lasts throughout the composition.

In the past, some of Dixon’s large-ensemble works have involved extensive, traditionally styled, written notation (his talents as an arranger and orchestrator, as demonstrated on the 1966 classic Intents and Purposes, are too rarely acknowledged). However, Dixon considers all forms of information exchange as a kind of notation, understanding that new musical ideas may need similarly new means of expression. So in recent years, Dixon has gone in a different direction; he will bring in a minimal amount of materials, but painstakingly craft how those materials are played and interpreted. The process becomes the notation. In rehearsal, it is not unusual to spend an hour on how a single line is phrased, or how a solitary chord resonates. By applying this level of care to the smallest details, Dixon forces the performers to become deeply aware of and engaged in every sound they create, and how the choices they make as individuals effect the ensemble as a whole. There also are a few pieces on Tapestries that had no written materials or instruction, but they are far from “free improvisations;” by existing in the sonic environment he cultivated and adhering to the clear principles he provided, the results are unmistakably the music of Bill Dixon.

Just as it is impossible to distinguish between the moments of composition and improvisation, it is a false dichotomy to distinguish between Dixon’s identity as composer and instrumentalist. In Dixon’s music, these are simply terms for the various practices of a consistent artistic vision. But this vision is clearly delineated in his innovations as a trumpeter. For all the extended techniques he has pioneered and the virtuosity he has displayed over the years, Dixon’s most striking tools have always been the diversity of his timbral palette, the character of his tone, and the drama of his rhythmic phrasing and use of space. From his earliest recorded improvisations with Archie Shepp and Cecil Taylor to the material in this package, it has always been less about the notes he plays than the sounds he chooses and where he places them. Where some trumpet players sorely miss the pyrotechnics of youth as they get older, Dixon’s playing maintains its intensity. While the physical palette he draws from has changed with age, the mastery with which he wields the brush continues to flourish. Take the openings of Tapestries’ two trio pieces, Slivers: Sand Dance for Sophia and Allusions I. What other trumpeter could shatter the silence with that kind of authority?

Dixon’s influence on the subsequent generations of brass improvisers is profound. The trumpet and cornet players on this album (Graham Haynes, Stephen Haynes, Rob Mazurek, and myself) are but a few examples of his many musical progeny, and even amongst the four of us, the diversity of ways this influence manifests itself is striking. None of us sound alike, nor do we sound like Dixon, but all of us clearly draw upon Dixon’s legacy in how we approach our horns. (It is also interesting to note that three of us are almost exclusively cornet players, and the fourth a very frequent practitioner. While perhaps less accurate and aggressive than the trumpet, the cornet has greater timbral flexibility; it is an instrument for those who improvise with sound as much as with notes. Not a coincidence that we are all so attracted to Dixon’s music.)

This influence is by no means restricted to brass players. Dixon’s subterranean explorations in the depths of the trumpet register clearly offer a template for Michel Coté’s contrabass clarinet work. Glynnis Lomon’s cello recontextualizes the rough-edged beauty of Dixon’s sound, where resonant pedal tones alternate with thrilling harmonics. Bassist Ken Filiano met Dixon for the first time at this recording, while the masterful percussionist Warren Smith has known him for over forty years, but both demonstrate an intrinsic understanding of his concepts. They allow the music enough space to breath freely without sacrificing rhythmic intensity.

For those who are already familiar with Dixon’s music, this recording offers a bracingly fresh document from an artist who, like Ellington or Picasso, refuses to sit still even after a fifty-year career. It is one moment in a journey of uncompromised expression investigating the very principles of sound. For those approaching Dixon’s music for the first time, I envy you. Hopefully, Tapestries for Small Orchestra will be the first addictive taste, offering a sonic feast to those open to experiencing sound and time in a new way.

Taylor Ho Bynum (b. 1975) has spent his career navigating the intersections between structure and improvisation – through musical composition, performance and interdisciplinary collaboration, and through production, organizing, teaching, writing and advocacy. Bynum’s expressionistic playing on cornet and his expansive vision as composer have garnered him critical attention on over twenty recordings as a bandleader and dozens more as a sideman. He currently leads his Sextet and 7-tette, most recently documented on the critically acclaimed 4-album set “Navigation” (Firehouse 12 Records, 2013), and the debut recording of his PlusTet, a 15-piece ensemble made up of his closest long-time collaborators, will be released in the fall of 2016.

His varied endeavors include his Acoustic Bicycle Tours (where he travels to concerts solely by bike across thousands of miles) and his stewardship of Anthony Braxton’s Tri-Centric Foundation (which he serves as executive director, producing and performing on most of Braxton’s recent major projects). In addition to his own bands, his ongoing collaboration with Braxton, past work with other legendary figures such as Bill Dixon and Cecil Taylor, and current collective projects with forward thinking peers like Mary Halvorson and Tomas Fujiwara, Bynum increasingly travels the globe to conduct community-based large ensembles in explorations of new creative orchestra music. He is also a published author and contributor to The New Yorker’s Culture Blog, has taught at universities, festivals, and workshops worldwide, and has served as a panelist and consultant for leading funders, arts organizations, and individual artists. His work has received support from Creative Capital, the Connecticut Office of the Arts, Chamber Music America, New Music USA, USArtists International, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

To contact Taylor, email thobynum [at] gmail [dot] com. To subscribe to Taylor’s occasional newsletter, click here. For complete CV, discography, and hi-res photos click the link below to download EPK.

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

BILL DIXON, 1925-2010: Musician, Composer, Painter, Educator, Critic, and Activist

https://www.bbc.co.uk/music/reviews/qrgw/

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/bill-dixon-the-benefits-of-the-…

I appreciate your interest in having me say some things that you can present in your paper to interested readers, readers that may be interested in my work, how I go about it, how I have existed, what my work means, how that work is arrived at and my general feelings as they relate to music and art and all of those things [everything in toto, if one really wants to look at it definitively] that relate to them.

I thought things over and it had occurred to me that there weren't really that many people who claim an interest in this music and its non-commercial events, if they can be called that, that would even consider what I said as even being relevant. And if I am in error with regard to that then where are these people?

The genesis of feelings experienced, put together and cemented into ideas after 50 or so many years of experiences all seemingly designed and aimed at the justification of the above...

However and at the risk of being or appearing maudlin, I am coming to New York this month. Yes I am coming to NY to do the Vision Festival. I will be coming from Montreal where I will have participated in a conference sponsored by McGill University that will have focused on the relationships that exist [if they do] between the visual arts and the musical arts, the art of this music, especially. I will have shown drawings, paintings, etchings, lithographs of my work that span 30 or more so years and my "paper , more oral than written, will have concerned itself with how I have approached both of these art forms in terms of aesthetic and philosophy and methodology. I will have performed a small portion of the piece of music that I will be doing in total at the Vision Festival. While I will be doing that section in solo form there in Montreal I will be doing it situated for a quartet in NY.

In the last year I have been philosophically and methodologically engaging in an even more deeper penetration into areas of solo trumpet performance that at present, from the standpoint of being a full time endeavour, have, for most of the players, seemed only useful as an adjunct to the other areas of their performance on the instrument. And, of course the reasons for this is obvious, audiences want to hear you play the things that they want you to play that indicate to them that you can play effectively and coercively in manners that get their attention in the ways that they want their attention gotten.

In August of last year I was able, in performance at the Baha'i Center (with the quartet of double bassist Dominic Duval; vibraphonist/drummer Warren Smith and piano/synthesizer player Tony Widoff), to focus on those things that, at this particular point in time, are of principal interest to me with respect to the instrument and with music, composition and improvisation naturally being considered.

In October, I went to Baden Baden, the Donaueschingen Event, at the invitation of Cecil Taylor, as one third of three established musicians in this music that had Cecil Taylor, Tony Oxley and myself poised to do music that would serve to reflect our collective and individual places, achievements and contributions in this area of music.

The performance format utilized for the realization of such music that might ensue out of this instrumentation, which after Donaueschingen included Portugal and London in November, was such that it permitted my continuance of the work on my areas of interest without sacrifice or dereliction of my obligation as a member of the trio.

The format for the performances had, for analytical purposes of discussion the following layout: three solos that preceded a short break that then led into a tutti performance by the trio. Oxley always took the first solo orchestrated to permit him maximum leverage and continuity to reveal the focus of his musical interests and concerns.

I took the second solo which let me, knowing what had preceded my entrance and what was to follow it, work with maximum freedom, regarding material, approach to that material and the handling of that material without concern with trying to establish any idea of an [for me] "artificial relationship to the other two players long established and comfortable with the norms of their years of performance as a duo, to the extent that when I felt that I had established my point(s) of view [musical] and reference, paved the way for the next solo which was that of Taylor.

The short period of silence that followed permitted the dynamic of the totality of the trio to come to terms with all that had existed [musically] previously. A fitting way, in my opinion when one is able to understand and appreciate both the freedoms and responsibilities that are resolutely attached to this kind of performance that the uninformed prefer to label, erroneously as "free."

Because it is virtually impossible for people like myself to manage to keep a group together I have to work especially hard to maintain both the ideas that I want to express more fully and directly, by intense practice on the instrument [I continue to put in about five or six hours a day irrespective of whatever else I am doing], knowing at the same time that that is not enough for the recognition, solidification and presentation of those ideas through performance via the public arena.

For a while I was driving from my house in North Bennington, down to Hudson, NY to do some "tightening up work, concerning the duo format, with the young musician-composer Tony Widoff. It was about a four hour drive, round trip, but was well worth it since it could concern itself with the music on a pure basis: how was what it was thought "worthy to be considered for performance to be dealt with and done to the aesthetic satisfaction of the two of us.

I am trying to, as I've said at other times, in my work on the instrument to pierce the outer "shell of creative music so that the "inner shell will be more "kind , in terms of an extension of the vocabulary, to that kind of "probing around. Some may just hear it as noise and I don't have the time, inclination and am also not afforded any kind of forum to debate them [at this point], but I find it, when all of the things that need to be working [with the help of the ever present Sages, as the late and much missed pianist-composer John Benson Brooks, was wont to say on many an occasion], the most exciting time for me musically.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Trumpeter, composer, bandleader, visual artist Bill Dixon was the organizer and producer of the now legendary October Revolution in Jazz, a concert series devoted to the then "new music in 1964 - the same year he was the prime architect of the ever-significant Jazz Composers' Guild, a group whose place in the history of this music is a philosophical model and progenitor for groups that have followed such as Chicago's Advancement for the Association of Creative Musicians (AACM) and St. Louis' Black Artists Group (BAG). He joined the faculty at Bennington College in 1968, where he was a professor for nearly 30 years before retiring. Dixon has recorded some hard-to-find jazz classics including Intents and Purposes (1966) and has recorded for Soul Note since 1980, releasing nearly a dozen gems for the label such as the two-volume Vade Mecum and Papyrus series.

BILL DIXON--'November 1981'

November 1981 is double album by American jazz trumpeter and composer Bill Dixon consisting of one disc recorded live in Zurich and another in a studio in Milan, Italy in November 1981 and released on the Italian Soul Note label.

Bill Dixon--Trumpet

Laurence Cook --Drums

Mario Pavone · Bass

Alan Silva--Bass

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XrAOvvpUNdU

Track listing

All compositions by Bill Dixon

Side A:

"November 1981" -10:40

"Penthesilea" -10:10

Side B:

"The Second Son" - 5:10

"The Sirens" - 7:05

"Another Quiet Feeling" - 6:48

Side C:

Announcement" - 1:13 omitted from CD rerelease

"Webern" - 1:24

"Windswept Winterset" -15:42

Side D:

"Velvet" - 6:44

"Llaattiinnoo Suite" -15:24

Announcement - 1:40 omitted from CD rerelease

Intents and Purposes is an album by American jazz trumpeter Bill Dixon, which was released in 1967 on RCA Victor. Despite critical acclaim at the time, it was soon out of print except for appearances in 1972 on Japanese RCA and later in 1976 on French RCA. The album was reissued on CD by International Phonograph in 2011.[1] The album's title is an example of a Siamese twins idiomatic expression.

Background

In 1966 Dixon premiered his composition "Pomegranate" at the Newport jazz festival with dancer Judith Dunn, and this performance led to a contract with RCA. Dixon signed with producer Brad McCuen to do a quartet piece, but instead he started working on "Metamorphosis 1962-1966", for an ensemble of ten musicians. The personnel was an unusual mix of freemen and mainstream jazzers. Pozar and Levin were Dixon's students at the time, and Lancaster and Kennyatta frequent participants in Dixon-Dunn projects.[2]

Reception

The JazzTimes review by Mike Shanley says that "The whole release compares to very little from that period and offers a stellar example of the composer’s vision".[6]

In a 2011 Village Voice article following the CD reissue, Francis Davis wrote: "If ever a jazz LP literally qualified as 'legendary,' Intents is it... I envy anyone first hearing it now, because it's as bold and surprising as anything newly released this year."[7]

Writing for The Vinyl District, Joseph Neff noted that the album, "if often gripping and raw is never chaotic," and commented: "Intents and Purposes' large group template combined with compositional fortitude and improvisational vigor makes it essential to any free jazz library."[8]

Point of Departure's Ed Hazell stated: "What's apparent from the opening moments of 'Metamorphosis'... is how well Dixon grasps the dichotomies and contradictions in the music of the time and how completely he controls them... Dixon the composer expertly transitions from one theme or passage to another; his ability to shape compositions into self-contained wholes would remain a hallmark of his art."[9]

Track listing

- All compositions by Bill Dixon

- "Metamorphosis 1962-1966" - 13:20

- "Nightfall Pieces I" - 3:47

- "Voices" - 12:08

- "Nightfall Pieces II" - 2:25

BILL DIXON ORCHESTRA:

- Bill Dixon - trumpet, flugelhorn

- Jimmy Cheatham - bass trombone

- Byard Lancaster - alto sax, bass clarinet

- Robin Kenyatta - alto sax

- George Marge - english horn, flute

- Catherine Norris - cello

- Jimmy Garrison - bass

- Reggie Workman - bass

- Robert Frank Pozar - drums

- Marc Levin - percussion

| Released | 1967 |

|---|---|

| Recorded | October 10, 1966, January 17 & February 21, 1967 |

| Studio | RCA Victor's Studio B, New York City |

| Genre | Jazz |

| Length | 31:40 |

| Label | RCA Victor |

Bill Dixon--""For Nelson and Winnie"

(Composition and arrangement by Bill Dixon)

From the album 'Thoughts' (1985)

'Thoughts' is an album by American jazz trumpeter and composer Bill Dixon recorded in 1985 and released on the Italian Soul Note label

VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8D5fcBIMEk

Track listing:

All compositions by Bill Dixon

"Thoughts" - 11:20

"Windows" - 4:40

"For Nelson and Winnie" -18:53

"A Song for Claudia's Children" - 11:10

"Brothers" - 8:30

"Points" - 8:45

BILL DIXON SEPTET:

Bill Dixon - trumpet, flugelhorn, piano

John Buckingham - tuba

Marco Eneidi - alto saxophone

Peter Kowald, William Parker, Mario Pavone - bass

Lawrence Cook - drums

Bill Dixon: Excerpts from Vade Mecum

January 29, 2010

AllAboutJazz

Dixon first presented his writings alongside scores, photographs, and drawings in the monograph L'Opera: A Collection of Letters, Writings, Musical Scores, Drawings, and Photographs (1967-1986), vol. I (Bennington: Metamorphosis, 1986, currently out of print). A companion volume has not yet surfaced, though Dixon maintains a collection of post-1986 writings that he has given the name Vade Mecum, or a "journal." It is something that he hopes to one day have published, along with a revised edition of L'Opera. Dixon has allowed exclusive access to some selections from these writings for publication here; they are unedited and maintain the prosaic and stylistic approach that characterizes his writings (i.e., all brackets, parentheses, and non-traditional punctuation are Dixon's), with a nod to the stream-of-consciousness.

When I visited

Dixon in 2008 at his home in Bennington, Vermont, the idea of a

"selection" was both necessary and anathema—I spent several days

discussing music, art, aesthetics, philosophy and criticism with him, a

huge amount of information that somehow had to be shaped into a

publishable and concise article. With the thoughts, ideas, reactions,

and opinions presented here, it's difficult to tell a reader (much less a

compiler) where a "good starting place" is—the beginning isn't always

the beginning. Since the title of the broader work is Vade Mecum,

I chose to begin with Dixon's responses to a list of questions and

ideas presented by the writer Graham Lock, who had been asked to write

the liner notes to Vade Mecum 2 (Soul Note, 1996), the second volume of quartet music joining Dixon with drummer Tony Oxley and bassists Barry Guy and William Parker.

What follows are some of Dixon's writings on ensemble and solo playing

("process" writings), a letter discussing the relationship of artists

(and Dixon specifically) to certain parts of the jazz/new-music press,

and the responses to two then-graduate students writing their theses on

Dixon's work. These excerpts stand as a companion to the AAJ interview Bill Dixon: In Medias Res and the selections of visual art available at the AAJ Photo Gallery (search for the "Bill Dixon" tag). Ultimately, however, my hope in

presenting this material is that it may provide a window into the

thoughts that, in part, have given rise to and resulted from a

half-century of Bill Dixon's music.

Chapter Index

- To Graham Lock

- The Art of the Solo

- Materials and Ideas for Discussion for Workshop in Contemporary Improvisation and Composition as That Relates to the Performance

- For Alexandre Peirrepont: The Weavers

- Answers to Additional Questions from Andrew Raffo Dewar

- Harnette Notes

This

one side of a faxed exchange between Bill Dixon and writer Graham Lock,

where questions are answered and ideas explored in preparation for

Lock's liner essay to the second volume of Vade Mecum

recordings for the Soul Note label (released 1996). It may be helpful

for the reader to have these in hand while re-reading Lock's notes to

the album and in (partly) experiencing the recording, but they stand on

their own equally well. —CA

Dear Mr. Lock:

I am

in receipt of your fax of 20 April 1996; I was in NY for a few days and

only returned on Saturday. Since time is of the essence I will attempt

to provide answers / that are clear / to your queries.

- The

main reason(s) for Vade Mecum, 1 and 2, circulates around the idea

that, as soon as it was possible to record ideas that I felt would

sustain the time factor of a recording, I have attempted since 1980 when

I began recording more / for me / "prolifically," I attempted to do so.

Whether to the listener it is aurally visible or not, I have gone

through great pains to space the recording of my work that is commercial

recording: I have, for many years, personally, by recording, documented

almost everything that I've done / so that that work that did become

accessible to the interested listening public could, as much as

possible, reflect the different stages or formations, regarding musical

ideas that I was involved with. For me there always IS a reason: I'm

working on a specific area; line, density, intervals, spacings, etc.;

how does that INTERACT, if it does, with what other members of the

group, if a group is involved, with what THEY, individually and/or

collectively, are working on; the nature of SOUND and the placement OF

that sound relating to attack and duration as THAT relates to the basic

nature of the trumpet and how that is articulated concerning the myriad

of ways that one can NEGOTIATE notes out of the instrument / and the

list continues, etc... / and that reason serves to dominate my thinking

relating to the RECORDING of my work and in the case of Vade Mecum served for the impetus of that work.

- The MAIN problem that was addressed relating to Vade Mecumcentered

around the idea of doing a complete work with the barest minimum of

verbal or academically notated / via manuscript / instructions to the

musicians that would be complete, cohesive, and non-reflecting of the

methodologies utilized in its realization, faithful to my concept of

composition / those "compositions" being authored by me / and yet "free"

enough to permit the feelings and personalities of the musicians to

exist and co-exist sans the general "hell-for-leather" musical attitude

that is generally / and erroneously / associated with areas of this

genre of music.

- The sound of Vade Mecum is

exactly what I had in mind and could not have been realized without the

players that were used. I wouldn't characterize the sound as "foggy'; it

seems / to me / to be a liquidly dark and light sound that is, because

of the instrumentation and the manner in which the musicians are able to

extract things from their instruments, is able to cross both the

borders and the boundaries of extreme high and low; seemingly with ease.

In that instance, there is more of a pointillistic approach to the

sound / relating to painting / rather than the alla prima / or more

specifically glaze approach that might be likened to Turner or Monet.

Again, for ME, THIS analysis is, of course, in hindsight, only able to

be even THOUGHT of after the fact; since at the time of execution it is

the THING that I'm after and NOT how it is done. And, in that instance,

there are no accidents. The intuition, sensitivity, musicality and

performanceability / if I can coin such a word / of things and ideas

only vaguely suggested / by me / TO the musicians, completely

dovetailed, consequently rendering the idea of "accident" as being

non-existent.

- I could hear that this music / or this

series of thoughts / was indeed possible if I had this group of players.

I had not played with either TONY OXLEY or BARRY GUY but had done an

extensive amount of work with WILLIAM PARKER. I knew of both Barry's

work and Tony's work. And it was Cecil Taylor,

while we were doing the concerts in Italy and France a few years ago,

who virtually insisted that I meet Tony since it was his feeling that

Tony and I shared musical sensibilities.

- I view Vade Mecum

as more formally DISTILLING things that I've been interested in and due

to that instrumentation / and the particular players / permitting a

certain KIND of evolution.

- The "accident of purpose"

can best be viewed if you will consider the way and manner in which the

"OCTETTE I" was done. I wanted the sound and textural feature of eight

players; and I had four. I knew I could overdub but I didn't want the

MECHANICAL sound and feeling of that kind of device. IN recording the

piece the first time it was just done; the second time, I used

headphones so that I could hear / and thus PLACE / what I had previously

played within the FRAMEWORK of that. I wanted that kind of symmetry.

The other players opted NOT to use headphones for the second time around

of recording and, as a consequence, there are places where the

"accidental" bumping into each other is EXACTLY what I like since I,

through what I was playing and how I was placing it could BALANCE, in

terms of line, height, and weight the TOTALITY of the sound. Am I being

clear??? Listen to it closely.

- The suggestions that I

gave were, as mentioned earlier, deliberately sparse and left open to

interpretation by the players. You don't HAVE to play in any specific

tonality, if the feeling for being metric or pulsative seems to indicate

that that is what you do, do it. Space, texture, lines and counterlines

are desirable, as is the idea of unison, octave unison, if it occurs

naturally depending on the direction of the music; I will indicate

possibilities of where one can go by what I play; dynamics can be

observed by the ability to hear all of what everyone is playing at all

times. Regarding the authorship of the compositions, what I play is the

composition, and what the players do are their reflections or reactions

to these compositions; hence the orchestration and the arrangement,

however you want to designate it. In that instance, from how I view

music / in this portion of the 20th century, after 2000 years of man's

making music / any indication of ANYTHING to any musician that causes

that musician to respond in any way other than what he would were it not

so indicated, IS notation. And since I define composition as "the

assembling of musical materials, generally accessible to every musician,

into a NEW order" and improvisation as the INSTANTANEOUS realization of

composition without the benefit / or demerit / of being able to change

or alter anything for ME, all music is both composed and improvised.

- With the exception of one piece / for the time span of the CD / all works were done in the order that they appear.

- I've answered this as much as I can at this point.

- You

are exactly right in "supposing" that the titles come after the music

and that, in some cases suggest a quality that / I / hear in the music.

PRIOR to that, however, I do make a determination concerning what THIS

particular music / relating to what I am attempting to do / is about. If

you will go through the titles of my works, including the very titles

of the albums themselves you should be made aware that I'm quite

conscious about the idea of the documentation of both ideas and the

placement / in time / OF those ideas. For example: INTENTS &

PURPOSES; THOUGHTS; CONSIDERATIONS; BILL DIXON IN ITALY; HAROLD IN

ITALY????/; etc.

VADE MECUM has several meanings; I used the meaning "NOTEBOOK" or "JOURNAL." INCUNABULA has several meanings; I used the meaning "early books" or "beginnings" / And it IS Latin. / smile//. The supposed "link" referring to the music and painting/drawing is NOT, as far as I can determine, pre-ordained DELIBERATELY by me. If there is a CONSCIOUS link that would have to do with the fact that I do both and would therefore had a NATURAL affinity for attempting / even if subliminally / a rhythmic stratification / relating to sound / AND the articulation of words that might attempt either a definition or simulation OF that sound through the titling of the music, etc. As far as DELIBERATELY plotting such a course architecturally to intellectually affect or attempt a DOVETAILING of the work / music and painting / I don't do that.

- There hasn't been a "hint" or a "whisper" of Intents and Purposes

being reissued on CD. A few years ago there were some mumblings but

that is as far as that went. I've asked SOUL NOTE to see about

purchasing it from RCA VICTOR.

- I prefer both the alto

flute, which is what the late George Marge played on "NIGHTFALL PIECES,"

and the bass flute which I've done some work with. I'll send you a

cassette of some of that work when I can get around to it.

L'OPERA, which is about 400 pages and would only be of interest to those that might have an INTENSE interest in my work and my thinking about a variety of things. I hope to publish it next year and am currently working on a revised edition of the first volume of L'OPERA, There is also the possibility that there will be a Japanese edition of L'OPERA in the near future. Ben Young's DIXONIA, which he is calling a biographical discography and documentation of the performances of my works, is being published by Greenwood Press and is slated for publication in 1997.

- The orchestra

work that is being released sometime this summer is the work with TONY

OXLEY'S CELEBRATION ORCHESTRA that was done at the Berlin Festival in

1994. I'm a soloist on that work.

- The VADE MECUM

quartet will be known for the two recordings, done in 1993, one issued

in 1994 and the other one / that you're doing the liner essay for /

sometime in the summer of 1996; and the concert in November 1994 in

Villeurbanne, France at the Espace Tonkin. Incidentally, there is a

video of the performance in Villeurbanne. As far as recording is

concerned, I have an orchestra work that I'd like to record; Andrew Hill

and I have / over the years / periodically discussed the idea of a duo

recording; I'm thinking of a solo piano recording; and there are various

ideas like that coruscating around. I'm currently discussing a tour /

for fall, October 1996 / for Italy, France and possibly Germany,that

would be followed by some work in Israel. There is also work being done

for some concerts in Japan. Of course there are some new paintings that

I'm outlining for work now in addition to my wanting to publish a

calendar of my lithographs done in Lyon, France in 1994.

- It

is not so much that "New Music" has been under attack as it is patently

being ignored as a music that generated certain valuable additions to

the language / vocabulary of music. It is my feeling that no matter how

one tries to deny the past that past has existed. There is a kind of

"palatable" niceness and "softness" of much of the music / this music /

that lacks a kind of / for want of a better and possibly more

politically correct word / "masculine" bite to it. We used to call it

cocktail music and while there is absolutely nothing wrong with it, it

is at times galling that we are made to believe that that is all there

is. Yes, it would be useful were you to pursue that kind of thought. It

might just wake someone up.

- If you can get a copy of BILL DIXON IN ITALY, Vol. 2,

which has just been released on CD by SOUL NOTE. The original notes in

the interview I had with Angelo Leonardi, were replete with errors which

I have, in this edition, corrected. Read what I try to explain there

and it should give you some idea as to what I mean.

- In

going through my works to arrange and catalogue them in the last four

or five years for the radio programs that Ben Young has done for

Columbia University's radio station WKCR, I began to view the work in a

different light. There is a tremendous amount of work and, considering

its breadth and scope, by ANYONE's standards, some of it has got to be

good. While that is not the basic reason WHY I have done this work, it

hasn't escaped my attention that work of any magnitude, or done for any

reason, is not completely fulfilled AS WORK until it has been given the

opportunity to be either heard or scrutinized by an outside public. Of

course, we have a hostile public; a non-caring public who willingly and

blindly have their minds turned in the direction of the so-called

purveyors of taste and aesthetics. And they seemingly accept carte

blanche what is put before them without even a glimmer of questioning. I

used to tell students, when they, when it was convenient, complained

about the inaccessibility of the new music, that when they went into a

record store to buy what they bought / always the heavily touted and

advertised more popular stuff / that they ASSIDIOUSLY avoided the other

music; they HAD to pass by some things to get to others. That if they

did NOTHING about a problem they had, in fact, done SOMETHING about it.

So if Van Gogh's SUNFLOWERS are NOW worth about $12 million, how is that

possible??? HE couldn't sell them, so they couldn't have been worth

anything. And if they weren't worth anything then, then they can't be

worth anything now!!!! We know that things derive their value from their

marketability or their lack of same. So I was arguing, at that time

about the viability of my own work and someone had suggested something

to me that was anathema to me. But that was in the summer of 1976, I was

on my way, that fall to do the AUTUMN FESTIVAL in Paris. In twenty

years I just may have changed my mind... I don't know, but I am

assembling my works to make up my estate and the final decision may be

left up to the person who will be managing that estate.

- You

should, by all means, call both Barry Guy and Tony Oxley. I'm certain

that they will, in a less turgid fashion than I can, supply you with

relevant and important information as seen from their eyes and

experienced by them.

Graham, though I may have tended to ramble a bit I hope that you can sift through all of this and come up with what is important and necessary for you to know. I'm looking forward to seeing how you will handle this as I find in your writing a knowledge, integrity and passion for the music that, unfortunately is in short supply in your profession.