AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/01/ornette-coleman-b-march-9-1930.html

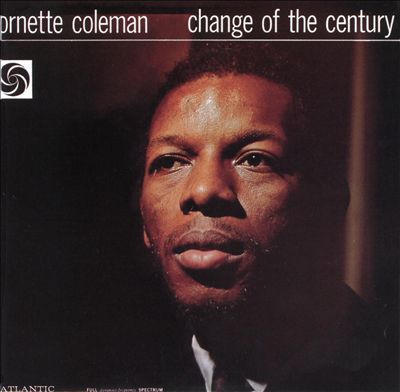

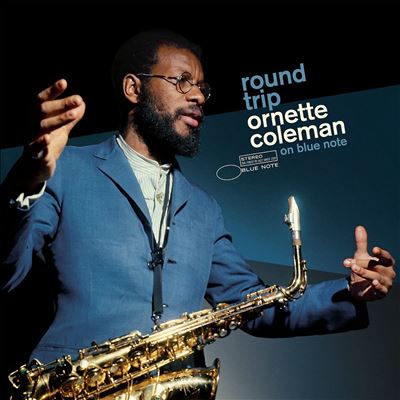

PHOTO: ORNETTE COLEMAN (1930-2015)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/ornette-coleman-mn0000484396/biography

Ornette Coleman

(1930-2015)

Biography by Thom Jurek

Saxophonist and composer Ornette Coleman was simultaneously one of the most beloved and polarizing figures in jazz history. Though now celebrated as a fearless innovator and a genius, he was initially regarded by peers and critics as rebellious, disruptive, and even a fraud. After being assaulted and having his horn smashed by hostile jazzmen, he switched to the white plastic alto sax that became his trademark. His instantly recognizable, keening, blues-drenched tone always sought to reflect the depth of human emotion and its utterance. Coleman's compositions from "Lonely Woman" to "Snowflakes and Sunshine" freed jazz from chord changes, fixed rhythms, and conventional harmony. His developed harmolodic system refused accepted notions of lone soloists improvising over accompanists, in favor of ensemble players improvising simultaneously around evolving melodic and rhythmic patterns. His revolutionary albums for Atlantic, including 1959's The Shape of Jazz to Come and 1961's Free Jazz (the album that inspired John Coltrane's Ascension), have been studied and covered by generations and taught in classrooms. In 1972 Coleman employed harmolodics in the large-scale work Skies of America in collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra. In 1976, he applied it to electric jazz-funk on Dancing in Your Head. During the 1980s, Coleman made pioneering recordings with guitarist Pat Metheny (Song X) and cut In All Languages, whose compositions were performed by an acoustic quartet and his electric Prime Time band. In 1991, he recorded Naked Lunch with Howard Shore, and in 2006 he debuted a new electro-acoustic ensemble for Sound Grammar.

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman was born in Fort Worth, Texas in 1930. He was drawn to music early on, playing kazoo with friends and imitating the sounds of the big bands that came through town. Coleman grew up poor. His father died when he was seven, forcing him to find odd jobs working at night after school let out. His mother, a seamstress, worked long hours and eventually saved enough to buy him his first alto saxophone at 14. He attended the city's I.M. Terrell High School, where he focused on music. In band class he met and played with Dewey Redman, Charles Moffett, King Curtis, Prince Lasha, and John Carter. Under the influence of a local saxophonist named Red Connors, who impressed upon him the importance of reading music, Coleman taught himself to sight read.

At 15 Coleman began playing a tenor horn in various jump bands and traveled to New York City to visit an aunt. There he was exposed to the emerging bebop revolution and returned to Fort Worth anxious to share his discovery. At 16, Coleman quit school, worked to help his mom, and formed the Jam Jivers with Lasha and Moffett. They initially played jump blues in R&B rooms and at sock hops. They eventually began playing bebop, too. Coleman often sat in with traveling jazz musicians, working on his bop chops without rejecting R&B. That trait -- his refusal to discriminate between types of music -- remained a pillar in his creative philosophy for the rest of his life.

In 1949, Coleman sat in with Silas Green's traveling minstrel troupe from New Orleans and subsequently joined his band. In 1950, he worked the road with bluesmen Clarence Samuels (where he met and played with New Orleans-born Ed Blackwell) and Pee Wee Crayton. During tours with the minstrel shows and blues bands, everyone from his bosses to ticket holders criticized his freer, blues-based playing style. In Baton Rouge, Coleman was beaten unconscious by local rednecks who didn't appreciate his soloing, bop leanings, or unconventional tone. They smashed his tenor horn, too. His response? He switched back to alto and purchased a white plastic Grafton horn similar to Charlie Parker's.

After leaving Crayton, Coleman spent time in a local R&B band in Amarillo. When the bluesman passed through Texas again, Coleman rejoined his band. They toured the American south and west and played a run of dates in Los Angeles in 1951. The work dried up and Coleman returned to Fort Worth the following year. At home there were service jobs and club work, but little to challenge him artistically. He began constructing his own systematic ideas about harmony, melody, and rhythm, and they became the root foundations of the harmolodic system he developed a few years later.

In 1953, with few prospects, Coleman opted to give Los Angeles another try. He reconnected with Blackwell, who had moved from Texas some months earlier. They shared a house in Watts and began formulating the harmolodic system, and worked many straight jobs because Coleman's playing style was off-putting to some club owners and many musicians who felt he didn't understand music or how to play his horn. He met and was befriended by Angelino drummer Billy Higgins and two Oklahoma expats, bassist Charlie Haden and trumpeter Don Cherry. All three were teens. Coleman also met and fell in love with poet and activist Jayne Cortez; they married in 1954 and had a son, Denardo, in 1956. They divorced in 1964 but remained close.

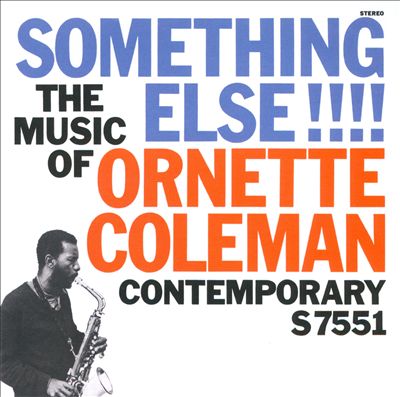

Blackwell returned to New Orleans in 1958, just before Coleman signed a record deal with Lester Koenig's Contemporary label. With Higgins, Cherry, bassist Don Payne, and pianist Walter Norris, he recorded Something Else!!!! The album shook things up on the jazz scene as critics and musicians -- including some of his more established sidemen -- couldn't accept Coleman's ideas about tonality, phrasing, or rhythm. That said, the harmonic blues interplay between the frontline players remains remarkable more than half-a-century later.

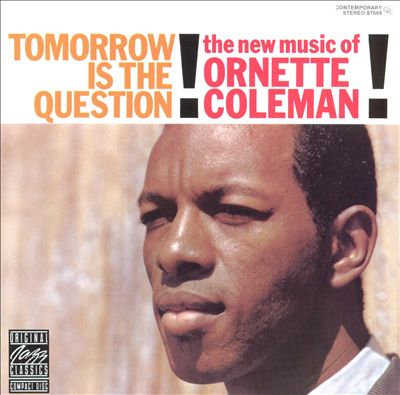

Coleman followed with 1959's Tomorrow Is the Question! He banished the piano and worked with Cherry, drummer Shelly Manne, and bassists Percy Heath and Red Mitchell. Though it received a more generous reception -- two of the album's greatest champions were John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor -- it was still burdened by the unforgiving attitudes of unsympathetic sidemen (Manne and Mitchell) and what critics erroneously perceived as a lack of cohesion.

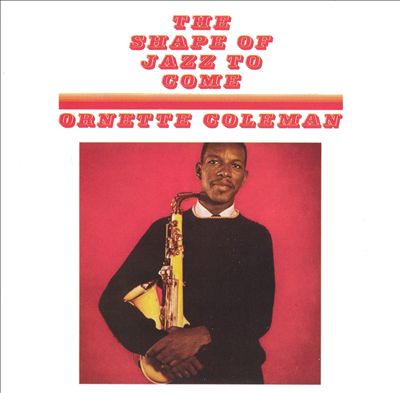

That April, Coleman signed with Atlantic Records. In May he cut The Shape of Jazz to Come with Higgins, Haden, and Cherry. He originally wanted the title to be "Focus on Sanity" (after its fourth track) but label boss Ahmet Ertegun convinced him that his own title offered listeners a peremptory idea of the album's importance. Ertegun was correct. The set contained two of Coleman's most enduring compositions, "Lonely Woman" and "Peace." That October, just before its release, the Coleman quartet returned to the studio to record Change of the Century.

By the time Shape of Jazz to Come was issued in early November, the Coleman quartet began what was supposed to be a two-week residency at the Five Spot arranged by the Modern Jazz Quartet's John Lewis. The gig created a firestorm of publicity in the press and the jazz community. It was attended and hotly debated by almost every jazz musician and critic in New York, and the band's sold-out run was extended to ten weeks: Miles Davis hated Coleman's music, but Leonard Bernstein, Sonny Rollins, and John Coltrane loved it. Charles Mingus claimed he didn't understand it, but was deeply moved by it nonetheless. Roy Eldridge was among the harshest critics; he called Coleman's music "fraudulent." Following that stand, Change of the Century was released in May 1960, to wildly contrasting reviews.

On December 21, Coleman assembled a double quartet in a New York studio that included bassists Haden and Scott LaFaro, drummers Blackwell and Higgins, trumpeters Cherry and Freddie Hubbard (an early detractor whom Coleman won over), and Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet. Adorned with a die-cut cover inset with painter Jackson Pollock's "White Light," Free Jazz opened the floodgates for vanguard music. Employing only a few brief pre-composed sections, the music was improvised by this large group in single takes with no overdubs or edits. After its release in 1962, Downbeat published two contrasting reviews -- that summed up a larger split among musicians, critics, and fans -- one article awarded its highest rating of five stars, while the other awarded none. Free Jazz ultimately became the template for two other historic jazz masterworks: Coltrane's Ascension and Peter Brötzmann's Machine Gun.

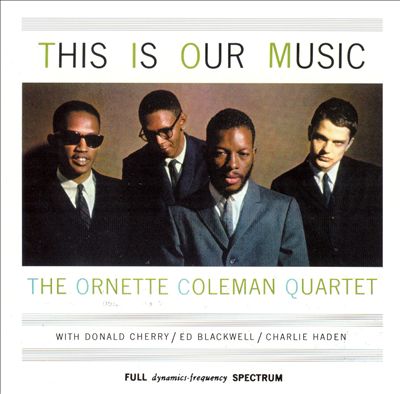

Between May 1959 and March 1961, Coleman recorded enough material for nine albums and released This Is Our Music (with Blackwell replacing Higgins), Ornette! (with LaFaro replacing Haden), Ornette on Tenor (with Jimmy Garrison on bass), and three albums released long after he left the label: Art of the Improvisers (1970), Twins (1971), and To Whom Who Keeps a Record (1975). All were compiled by Rhino in the 1993 box set Beauty Is a Rare Thing.

While the Atlantic albums had an immediate cultural impact, Coleman was discouraged and angry about the state of his career by the end of 1962. Atlantic canceled his contract, club owners and concert promoters exploited him or wouldn't book him, and most critics possessed little to no understanding of his music. He believed racism was the key reason. Coleman retreated from recording and playing live music for just over two years. During his self-imposed exile, he continued refining the harmolodic system and taught himself to play violin and trumpet. When he returned to action, it was with a new trio featuring bassist David Izenzon (a classical musician who had picked up the jazz double bass at 24) and high school friend Charles Moffett on drums. Two years earlier, Coleman composed and recorded Chappaqua Suite, a rejected score for a Conrad Rooks film that also included Pharoah Sanders on tenor. The project paid well enough for Coleman's trio to tour Europe. Chappaqua Suite was eventually released in 1966 by CBS Europe.

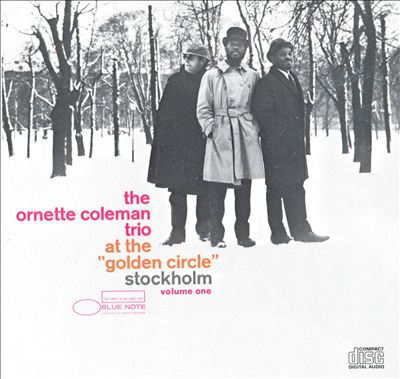

In December 1965, after touring for a couple of months, Coleman booked his new trio into the edgiest jazz club in Stockholm, the Gyllene Cirkeln (Golden Circle) for a two-week run. He had signed to Blue Note earlier that fall and the label recorded two shows, which were quickly released in 1966 as At the "Golden Circle" Stockholm: Vol. 1 & Vol. 2. These outings showcased Coleman playing his new instruments and alto in compositions and improvisations that went further out than anything he'd done before. They revealed a new emotional resonance in his own tone as well as a controlled palette of microtones that he could employ rhythmically and harmonically. While the Swedes and other Europeans embraced Coleman as a prophet of the new, critics and jazz fans in the U.S. were still having a very difficult time understanding his music.

Coleman cut five albums for Blue Note. His first date for the label was the wildly controversial studio outing The Empty Foxhole with Haden on bass and ten-year-old Denardo on drums. Critics and jazz musicians derided the album because of his son's inexperience. Coleman didn't include him because he was a master drummer, but because Denardo's emergent emotive playing style provided the saxophonist with the kind of melodic counterpoint he now found central to his music. In 1967, Coleman appeared as a collaborating sideman on Jackie McLean's New and Old Gospel, playing trumpet exclusively. Comprising a side-long suite by McLean and two Coleman tunes on the flip, the record got mixed reviews, but McLean considered it one of his most inspired recordings.

Vanguard classical musicians, critics, and listeners were beginning to embrace Coleman's advanced music. That year he collaborated with the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet and the Chamber Symphony of Philadelphia Quartet. They recorded three of his works in New York City for The Music of Ornette Coleman, issued by RCA in the U.K. Coleman was awarded the first of two Guggenheim fellowships. He returned to Blue Note for a pair of quartet dates cut in two sessions nine days apart in the spring of 1968: New York Is Now! and Love Call. His lineup on both included drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison from Coltrane's quartet, and high school friend tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman, who was also making a name for himself in New York. Despite the rhythm section's star power and their "big beat" intensity, neither album sold very well and Coleman left the label.

He signed with Impulse in July 1968, and released Ornette at 12 in early 1969. Its lineup included Haden and Redman, and marked the return of Denardo, age 12 (hence the title). Critics savaged it, but by this time Coleman no longer cared. He understood his son's gift and potential. Denardo eventually became his primary drummer, music director, and manager, roles he served for the rest of his father's life. Coleman also recorded Crisis for the label. Recorded in concert at New York University in 1969, it marked the return of Cherry to Coleman's employ alongside Haden, Redman, and Denardo; it went unreleased until 1972.

In early 1971, Coleman signed with Columbia. In April he brought a slew of alternating musicians into a New York studio including Higgins, Blackwell, Haden, Redman, and Cherry. Also joining the proceedings were trumpeters Jacques Schwarz-Bart and Bobby Bradford, and vocalist Asha Puthli. These bracing free sessions resulted in Science Fiction, Coleman's most popular album since leaving Atlantic. In the 21st century it still sounds ahead of its time. These exploratory sessions netted an abundance of quality material; the balance appeared in 1982 as Broken Shadows.

In April of 1972 Coleman teamed with the London Symphony Orchestra and recorded his first large-scale orchestral work, Skies of America. Initially conceived as a concerto grosso for jazz quartet and orchestra, the musicians union in England wouldn't allow Coleman's band to play on the album. As such, he contributed to several interludes solo. This set marked the first time Coleman's harmolodic system was employed on such a grand scale. American critics Robert Palmer and Bill Milkowski enthusiastically embraced it, as did several others. Commercially it fared well in Europe -- where it got radio play -- and it sold respectably in the U.S. It and Science Fiction have undergone major critical reappraisals in in the late '90s and 2000s, and are now considered masterworks. Coleman received his second Guggenheim Fellowship for Skies of America. In 1975, a compilation of unissued recordings from the Atlantic period appeared as To Whom Keeps a Record.

Coleman signed a one-off deal with A&M's Horizon imprint and showcased his harmolodic funk band, Prime Time. The lineup included two electric guitarists in Bern Nix and Charles Ellerbee, two drummers in Denardo and Ronald Shannon Jackson, and electric bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma. Their debut album, 1977's Dancing in Your Head, turned jazz-funk and vanguard jazz upside-down. The A-side offered two variations of "Theme for a Symphony" -- one instantly memorable melodic vamp played incessantly with cyclical soloing by all members. The flip, "Midnight Sunrise," was a sprawling collaboration with Morocco's Master Musicians of Jajouka. Sympathetic critics embraced it and compared it to the music of Parliament-Funkadelic and Sly Stone. Interestingly, some even favored it over Miles Davis' electric offerings (leading to a reassessment of Coleman by the trumpeter). It was the first jazz album to ever enter the Village Voice's Pazz & Jop Poll.

Coleman took Prime Time (sans Denardo) on tours of Europe and Japan. In Paris they entered a recording studio and cut the quintet sessions that would become 1978's Body Meta for Artist House (named after Coleman's term of endearment for his famous Prince Street loft). In 1977, Coleman and Haden recorded the acclaimed duet offering Soapsuds, Soapsuds for the same label. In 1978, Coleman, Denardo, and Tacuma backed electric guitarist James Blood Ulmer on his Artist House debut, Tales of Captain Black and toured with him.

In 1979, Prime Time entered CBS Studios in New York City with Denardo and drummer Calvin Weston. There to record a direct-to-disc outing that failed due to mechanical problems; they ultimately emerged with the first digitally recorded jazz album, 1982's Of Human Feelings. Released by Island subsidiary Antilles, it received global acclaim and registered positive notice in the U.K. from DJs such as John Peel. Unfortunately, it sold poorly and was soon deleted.

Following a dispute over royalties, Denardo replaced Coleman's manager. In 1985, Coleman and Prime Time played the inaugural concert at Caravan of Dreams, a performing arts space, gallery, and record label in his hometown of Fort Worth. The lineup included Denardo and Sabir Kamal on drums, Ellerbee and Nix on guitars, and Tacuma and Al McDowell on bass. It resulted in the album Opening the Caravan of Dreams.

Guitarist Pat Metheny had been a lifelong admirer of Coleman's. He'd cut the saxophonist's tunes on albums such as Bright Size Life, 80/81, and Rejoicing, and employed his sidemen. Metheny had just left ECM for Geffen and made a stipulation of his signing that he get to record with Coleman. They cut the co-billed Song X over three days in 1985. The lineup included Haden, Denardo, and Jack DeJohnette. It garnered glowing reviews, as Metheny's guitar synthesizer uncannily matched the tone of Coleman's horn. Metheny fans, however, had a harder time with the collaboration. The band's concert at the University of Michigan's Hill Auditorium found Coleman's fans enthusiastic about the performance, even as hundreds of Metheny fans streamed for the exits shortly after it began. The following year, Coleman released the double-length In All Languages for Caravan of Dreams. His 1950s quartet performed on one record while Prime Time played on the other.

On September 18, 1987, Coleman, Denardo, and Cecil Taylor attended a Grateful Dead concert at Madison Square Garden at the invitation of Dead bassist Phil Lesh (a longtime fan of both the pianist's and the saxophonist's). Witnessing the crowd's enthusiasm inspired Coleman to conceive, write, and record the album Virgin Beauty for Portrait Records in 1988. It presented Prime Time in a more accessible setting that included the Dead's guitarist Jerry Garcia as a guest on three tracks. (Coleman would later return the favor and perform with the Grateful Dead at a 1993 concert.) The album's airy, synthetic production values were drawn from pop music. The harder funk and R&B elements were all but absent -- they were replaced by a more dynamic, hybridized take on world music. It became Coleman's best-selling album, which makes it seem a bit strange that Prime Time wouldn't record again for seven years.

In 1990, the city of Reggio Emilia in Italy held a three-day "Portrait of the Artist" tribute to Coleman featuring his 1950s quartet. The festival also presented performances of his chamber music and Skies of America. In 1991 Coleman worked with composer Howard Shore to compose and record the score and soundtrack for David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch along with the London Symphony Orchestra. The recording offers the rare opportunity to hear Coleman playing a standard: namely, Thelonious Monk's "Misterio." In 1994, the saxophonist was awarded a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant.

Coleman founded his own Harmolodic label and signed a distribution deal with Verve. They reissued In All Languages in 1994, and in 1995 released Prime Time's Tone Dialing. This version of the band included guitarists Chris Rosenberg and Ken Wessel, bassists McDowell and Bradley Jones, Badal Roy on percussion, Denardo on drums, and Chris Walker and Dave Bryant on keyboards. Coleman also appeared on pianist Geri Allen's Eyes in the Back of Your Head that year.

In 1996 Coleman released two albums simultaneously: Sound Museum: Three Women, and Sound Museum: Hidden Man. Thirteen of his compositions were performed in radically different versions on both releases by the same quartet: Allen (the first pianist he'd worked with since the '50s), bassist Charnett Moffett, and Denardo. The lone vocal track "Don't You Know by Now" featuring Lauren Kinhan and Walker, appeared only on the former title. Later that year, Coleman and pianist Joachim Kuhn recorded a duet concert in Poland. It was released in 1997 as Colors: Live from Leipzig.

In 2000, Coleman made an unlikely sideman appearance on singer/songwriter/producer Joe Henry's album Scar. Henry claimed that Coleman initially turned him down, but after the saxophonist heard what he considered an unusual grain in the singer's voice, he eventually agreed. The pair also played a duo concert at New York's Town Hall. In 2005, Geffen remastered and reissued Song X in a greatly expanded edition.

The last album to appear under Coleman's name during his lifetime was Sound Grammar in 2007. A live offering, it was recorded two years earlier at a festival in Ludwigshafen, Germany. His quartet featured bassists Greg Cohen and Tony Falanga with Denardo on drums. That year, the Grammy Foundation presented the saxophonist with a lifetime achievement award. In September of 2010, Coleman made a guest appearance at Sonny Rollins' star-studded Sonny@80 Concert in New York City. They performed "Sonnymoon for Two" with bassist Christian McBride and drummer Roy Haynes. The track appeared on Roadshows, Vol. 2. Coleman also appeared on Tacuma's 2011 tribute album For the Love of Ornette. Though Coleman continued to work with other musicians, he issued no further recordings. He died on June 11, 2015, at age 85.

In 2022, Blue Note issued the archival six-LP box set, Round Trip: Ornette Coleman on Blue Note as part of its celebrated Tone Poet series, and Craft Recordings reissued his Contemporary albums in a deluxe vinyl package titled Genesis of Genius.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/ornette-coleman/

Ornette Coleman

Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance - Coleman was 29 at the time - but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called "harmolodic," a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as "Removing the caste system from sound." On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony.

For his essential vision and innovation, Coleman has been rewarded by many accolades, including the MacArthur "Genius" Award, and an induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letter. an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Pennsylvania, the American Music Center Letter of Distinction, and the New York State Governor Arts Award.

But the path to his present universal acclaim has not always been smooth.

Born in a largely segregated Fort Worth, Texas on March 9, 1930, Coleman's father died when he was seven. His seamstress mother worked hard to buy Coleman his first saxophone when he was 14 years old. Teaching himself sight-reading from a how-to piano book, Coleman absorbed the instrument and began playing with local rhythm and blues bands.

In his search for a sound that expressed reality as he perceived it, Coleman knew he was not alone. The competitive cutting sessions that denoted 'bebop' were all about self-expression in the highest form. "I could play and sound like Charlie Parker note-for-note, but I was only playing it from method. So I tried to figure out where to go from there," Coleman said.

Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs.

But simply by persisting, Coleman's creativity attracted champions. Bebop bassist, Red Mitchell (an old associate of Cherry's) brought the saxophone player's to Contemporary Records' Lester Koenig, originally intending to sell him some of his compositions. After realizing the difficulty musicians were having in playing the music Koenig asked Coleman if he could play the tunes himself. The meeting led to the Coleman’s debut 1958 album, Something Else.

The energy and electricity that had been building around Ornette and his players exploded during a now legendary season that Coleman played at the Five Spot jazz club in New York in November, 1959. Intrigued by rumors of the unorthodox young Texan's approach, buzz preceded the shows and as the initial two weeks extended to a six-week run, the revolutionary Coleman quartet became the must-see event of the season.

And yet, as writer and long-time Coleman associate, Robert Palmer, observes in his notes to the Beauty Is A Rare Thing box set of the Atlantic years (Rhino/Atlantic), "The present day listener will most likely hear these pieces as well conceived and superbly realized works on their own terms and will again wonder what all the controversy could have been about."

Coleman soon began to study of the trumpet and violin expanding the scope of his always prolific composition to include string quartets, woodwind quintets and symphonic works. Coleman used a Guggenheim Foundation grant to write a symphony, Skies of America.

Coleman went on a journey to Morocco in 1973, to work with the Master Musicians of Jajouka in their mountain villages. Following he also visited villages in Nigeria. Soon upon his return Coleman created with a new sound that was a full frontal harmolodic attack, a double whammy of drums and electric bass, dubbed Prime Time.

Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988's Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).

The new autonomy heralded a season in which Coleman began to reap consistent accolades for his continued adventures in music. He formed the Harmolodic Label and began an association with Polygram France. Over the course of the decade Harmolodic released a number of works beginning with Tone Dialing, on which a Bach prelude is rendered harmolodically.

One of the ultimate American accolades, the MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant, was awarded to Coleman in 1994. In general, rather than simple concerts, Coleman's performances had by now become big multimedia events that both reflected and impacted on the host town's community, lasting for several nights at a significant location.

Lincoln Center provided the backdrop for Civilization 1997. A four-night event at Avery Fisher Hall. It began with two nights of Kurt Masur conducting the New York Philharmonic together with Prime Time. Perhaps the most eagerly awaited aspect of all four nights was the first New York appearance in two decades of the Original Quartet, performing all new material. Hearing the familiar, still stimulating blend of Coleman, Haden and Higgins was an emotional experience for many listeners, who found in the depth of the players' empathy a yardstick of their own lives and the fulfillment of dreams they had when they first heard the Quartet shatter conceptions of music.

A metaphysician, philosopher and eternal student, Coleman continues to confound categorization. His Harmolodic world continues to expand along with the concepts of an artist beyond boundaries. "Most people think of me only as a saxophonist and as a jazz artist," he once stated, "but I want to be considered as a composer who could cross over all the borders."

https://www.openculture.com/2014/09/jacques-derrida-interviews-ornette-coleman.html#google_vignette

Philosopher Jacques Derrida Interviews Jazz Legend Ornette Coleman: Talk Improvisation, Language & Racism (1997)

in Jazz, Music, Philosophy

September 26th, 2014

Images of Coleman and Derrida, via Wikimedia Commons

This most certainly ranks as one of my favorite things on the internet, and I dearly wish we had audio to share with you, though I doubt any exists. What we do have is an English translation from the French of an interview that originally took place in English between philosopher Jacques Derrida and jazz great Ornette Coleman.

Now there are those who dismiss Derrida—who consider his methods fraudulent. If you’re one of them, this is obviously not for you. For those who appreciate the turns of his thought, and the fascinating possibilities inherent in a Derridian approach to jazz improvisation, not to mention the convergences and points of conflict between these two disparate cultural figures, read on.

The interview took place in 1997, “before and during Coleman’s three concerts at La Villette, a museum and performing arts complex north of Paris that houses, among other things, the world-renowned Paris Conservatory.” As I mentioned, the two spoke in English but, as translator Timothy S. Murphy—who worked with a version published in the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles—notes, “original transcripts could not be located.” Curiously, at the heart of the conversation is a discussion about language, particularly “languages of origin.” In answer to Derrida’s first question about a program Coleman would present later that year in New York called Civilization, the saxophonist replies, “I’m trying to express a concept according to which you can translate one thing into another. I think that sound has a much more democratic relationship to information, because you don’t need the alphabet to understand music.”

As one example of this “democratic relationship,” Coleman cites the relationship between the jazz musician and the composer—or his text: “the jazz musician is probably the only person for whom the composer is not a very interesting individual, in the sense that he prefers to destroy what the composer writes or says.” Coleman goes on later in the interview to clarify his ideas about improvisation as democratic communication:

[T]he idea is that two or three people can have a conversation with sounds, without trying to dominate or lead it. What I mean is that you have to be… intelligent, I suppose that’s the word. In improvised music I think the musicians are trying to reassemble an emotional or intellectual puzzle in which the instruments give the tone. It’s primarily the piano that has served at all times as the framework in music, but it’s no longer indispensable and, in fact, the commercial aspect of music is very uncertain. Commercial music is not necessarily more accessible, but it is limited.

Translating Coleman’s technique into “a domain that I know better, that of written language,” Derrida ventures to compare improvisation to reading, since it “doesn’t exclude the pre-written framework that makes it possible.” For him, the existence of a framework—a written composition—even if only loosely referenced in a jazz performance, “compromises or complicates the concept of improvisation.” As Derrida and Coleman try to work through the possibility of true improvisation, the exchange becomes a fascinating deconstructive take on the relationships between jazz and writing. (For more on this aspect of their discussion, see “Deconstructin(g) Jazz Improvisation,” an article in the open access journal Critical Studies in Improvisation.)

The interview isn’t all philosophy. It ranges all over the place, from Coleman’s early days in Texas, then New York, to the impact of technology on music, to Coleman’s completely original theory of music, which he calls “harmolodics.” They also discuss globalization and the experience of growing up as a racial minority—an experience Derrida relates to very much. At one point, Coleman observes, “being black and a descendent of slaves, I have no idea what my language of origin was.” Derrida responds in kind, referencing one of his seminal texts, Monolingualism of the Other:

JD: If we were here to talk about me, which is not the case, I would tell you that, in a different but analogous manner, it’s the same thing for me. I was born into a family of Algerian Jews who spoke French, but that was not really their language of origin [… ] I have no contact of any sort with my language of origin, or rather that of my supposed ancestors.

OC: Do you ever ask yourself if the language that you speak now interferes with your actual thoughts? Can a language of origin influence your thoughts?

JD: It is an enigma for me.

Indeed. Derrida then recalls his first visit to the United States, in 1956, where there were “‘Reserved for Whites’ signs everywhere.” “You experienced all that?” he asks Coleman, who replies:

Yes. In any case, what I like about Paris is the fact that you can’t be a snob and a racist at the same time here, because that won’t do. Paris is the only city I know where racism never exists in your presence, it’s something you hear spoken of.

“That doesn’t mean there is no racism,” says Derrida, “but one is obliged to conceal it to the extent possible.”

You really should read the whole interview. The English translation was published in the journal Genre and comes to us via Ubuweb, who host a pdf. For more excerpts, see posts at The New Yorker and The Liberator Magazine. As interesting a read as this doubly-translated interview is, the live experience itself was a painful one for Derrida. Though he had been invited by the saxophonist, Coleman’s impatient Parisian fans booed him, eventually forcing him off the stage. In a Time magazine interview, the self-conscious philosopher recalled it as “a very unhappy event.” But, he says, “it was in the paper the next day, so it was a happy ending.”

Hear more of Coleman’s thoughts on language, sound, and technology in the 2008 interview above (see here for Part 2). The year previous, in another conjunction of the worlds of language and music, Coleman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music for his live album Sound Grammar, a title that succinctly expresses Coleman’s belief in music as a universal language.

Image of Ornette Coleman by Geert Vandepoele

Related Content:

Charles Mingus Explains in His Grammy-Winning Essay “What is a Jazz Composer?”

Derrida: A 2002 Documentary on the Abstract Philosopher and the Everyday Man

1959: The Year that Changed Jazz

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/ornette-colemans-revolution

June 11, 2015

Ornette Coleman’s Revolution

by Richard Brody

The New Yorker

Coleman was a musician who always thought of his music in philosophical terms; in Shirley Clarke’s film, “Ornette: Made in America,” from 1985, Coleman discusses some of those ideas in detail; he does so, too, in this conversation with Jacques Derrida, from 1997. But the essence of Coleman’s philosophy connects it to the defining trait of philosophical thought from Socrates onward: the puncturing of shibboleths, the rational devaluation of concepts considered essential, the proof through reason that ideas and categories believed to derive from nature are merely convenient artifices and social markers and can easily be dispensed with. But those ideas and categories are dispensed with by those who cherish their freedom of spirit, and often at the cost of their social position. To expose familiar habits as fusty fabrications is to expose oneself to ridicule, as a weirdo, and to persecution, as a threat to the established order.

The order that Coleman overturned with, seemingly, a blast from his alto saxophone is, in a word, bebop. Not that he didn’t love the music of Charlie Parker. (They narrowly missed playing together at a Los Angeles club in 1951 or 1952.) Coleman said, “I wanted to have the experience of him hearing what I had done, because by the time we met, in 1951 or ’52, I was really into what I did later on my own records.” Coleman’s frequent musical collaborator, the trumpeter Don Cherry, explained what went wrong: “When he got to the club, they wouldn’t allow him in because of his long hair.”

Parker took the harmonic structures of popular songs, and of his own compositions, and complexified them, extending the range of improvisations into exotically chromatic realms. But as far as Parker’s solos may have ranged, he and his fellow musicians kept the structure of the tune in their heads, matching chords to bars and replicating, in chorus after chorus, the underlying musical architecture of the composition. Coleman’s idea was to play the melody. He didn’t get rid of the notion of harmony—he and his musicians created magnificent contrapuntal interweavings—but he got rid of the idea of a fixed series of chords that matched to a fixed series of bars and to particular beats within bars. Coleman composed melodies that had wondrous harmonic implications—and he and his bandmates adopted those implications freely, as the inspiration struck them.

Coleman was from Fort Worth and he grew up hearing and playing the blues. Much of his music was inspired by the blues, and the first thing that strikes a listener, upon hearing the 1959 recording, “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” is that, as radicalism goes, it’s damn catchy. The sobriquet “free jazz” may have been an apt slogan for what Coleman was doing, and it became the title for his 1960 album that was built around collective improvisations by Coleman’s “double quartet” (in practice, it featured individual solos punctuated freely with interjections from three other horn players), but much of what Coleman and his fellow musicians chose to do with their freedom involved irresistible melodic invention and deeply swinging grooves.

Yet to working musicians whose sense of form and craft were deeply ingrained—and whose personal artistry and place in the profession were built on improvising on the harmonies of songs—Coleman, for all his lyrical inventiveness and rhythmic drive, was a threat. Jazz could suddenly dispense with their techniques—and when Coleman became an instant succès de scandale, battle lines and generational lines were drawn.

Just as, at the very same moment, the French New Wave swept away many of the conventions of filmmaking while honoring its greatest artistic traditions, Coleman inaugurated a new era in jazz that rendered it instantly pliable to a generation of musicians whose background differed from that of classic artists. The club scene was withering; local bands were often supplanted by recordings; rock and roll had risen to take the place of jazz-like music as the central popular style; and younger musicians were likelier to have conservatory training. The instant, across-the-board freedom that Coleman heralded and that he put into action opened the door to a panorama of possibilities.

By 1962, he had composed a string quartet, while also playing with a trio that meandered through tempi and rhythms with him in vast organic compositions developed on the wing. His trumpeter, Don Cherry, became one of the early avatars of world music; the bassist in his famous quartet, Charlie Haden, became one of the key figures in a sort of archeologically eclectic classicism; and Coleman’s own music took visionary turns (as seen in Clarke’s film) that involved technological and sociological experiments, symphony orchestras, international cross-pollination, and, in the nineteen-seventies, plugging in with a band that featured multiple electric guitars and a new theory that he called “harmolodics.” (He spoke to The New Yorker’s editor, David Remnick, about it in 2000.) Here’s a remarkable early example, from 1978, of its power. It features the guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer, one of the avant-funk masters.

But if there is, above all, one core word for Coleman’s achievement, it’s passing from the realm of music—with its social and conventional implications—to the realm of sound. Coleman broke through style and structure to seek sound. He himself had a sound like no other (initially, playing a plastic saxophone). Coleman is instantly recognizable from a single note, and that sound—separated from the theoretical apparatus of music, from the modes of the profession, from the critical categories of jazz—is inseparable from his very being. Coleman’s liberation of jazz was intimate and personal from the start, for listeners and musicians alike.

Richard Brody began writing for The New Yorker in 1999, and has contributed articles about the directors François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Samuel Fuller. He writes about movies in his blog for newyorker.com.

Seeing Ornette Coleman

June 12, 2015

The New Yorker

Ornette Coleman posited that the infinite improvisational possibilities of a melody could thrive outside of a predetermined structure, that musical ideas could flow and expand in the moment as naturally as breath or speech or thought. A simple idea that shook the world of twentieth-century music—a revolutionary idea that sounded like a folk song, lilting with the loving congeniality of a parent singing to a child.

Coleman was always an outsider. While others fixated on the fluid virtuosity and harmonic sophistication of Charlie Parker, Coleman heard the bluesy cry in Parker’s tone and the rhythmic unrest just beneath the surface. He spent his early twenties touring with carnival shows and rhythm-and-blues bands, suffering ridicule (even physical abuse—he was once actually attacked and beaten after a gig) for his unconventional approach. He eventually found his way to Los Angeles, where he worked part-time as an elevator operator and began to find new allies amidst the disdain. With long hair and a beard, long before that look was in fashion, and wearing a heavy overcoat in ninety-degree weather, Coleman scared the trumpeter Don Cherry at their first meeting. But the music drew Cherry in, and soon their symbiotic telepathy recalled Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s. In addition to Cherry, such burgeoning master improvisers as the bassist Charlie Haden and the drummers Billy Higgins and Ed Blackwell heard the magic in Coleman’s concept and dedicated themselves to its ensemble realization.

In a jazz industry often obsessed with young lions, Coleman didn’t make his recording début until a month before his twenty-eighth birthday (“Something Else!!!!” on Contemporary Records in 1958). From the beginning of the album, you can recognize his mature conception, even while you hear Coleman and Cherry chafing at the more conventional forms imposed by the pianist and bassist that the label brought in. By the following year, now accompanied by like-minded collaborators of his own choosing, Coleman moved to New York City and began a series of classic recordings for Atlantic Records—including “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” “Change of the Century,” and “This is Our Music”—which lived up to their propitious titles. He also began an extended residency at the Five Spot, in New York City, that solidified his role as the figurehead of the “new music.”

Sporting a white plastic alto saxophone (matched by Don Cherry’s toy-like pocket trumpet), abandoning traditional song form and chord changes, with the microtonal vocal cry of his horn following the unforgettable cadences of his melodies, Coleman became the contentious flash point for arguments over the validity of the avant-garde. Critics were divided, pro and con, five-star reviews against zero stars, no middle ground. Some musicians rallied in Coleman’s defense, others denounced him as a charlatan. It was the loudest argument in jazz since the emergence of bebop, and perhaps the last loud enough to echo into the popular consciousness. In Thomas Pynchon’s 1963 novel “V.”, a thinly veiled character named McClintic Sphere appears, playing a “white ivory” saxophone at the “V Spot.” Pynchon’s wonderfully terse parody of the portentous debate around Coleman’s music is as follows:

“He plays all the notes Bird missed,” somebody whispered in front of Fu. Fu went silently through the motions of breaking a beer bottle on the edge of the table, jamming it into the speaker’s back and twisting.Over fifty years later, it is hard to remember what all the fuss was about—Coleman’s music is so naturally swinging, so melodic, so bluesy, especially in comparison to the more extreme abstractions of his near contemporaries such as Cecil Taylor or Albert Ayler. But we take for granted how profound his influence was. Without Coleman’s lead, neither the spiritual explorations of the late John Coltrane Quartet nor the elegant deconstructions of the Miles Davis Quintet with Wayne Shorter would have existed. Experimental rockers from the Velvet Underground to Sonic Youth cite his example; everyone from Yoko Ono to the Grateful Dead sought his collaboration. Sourcing from those examples alone, you can draw a family tree of most of the creative jazz and popular music of the past half century.

One of those Atlantic recordings, “Free Jazz,” featuring Coleman’s double quartet, was famously paired with a Jackson Pollock painting as the cover art. While the modernist comparison with Pollock is apt, I would argue the term “free jazz” is a continuing misnomer—for all its humanistic abandon, Coleman’s music is deeply grounded in structure and concept. (The term has created other misunderstandings: a rare double quartet-concert, in Cincinnati in 1961, was cancelled after a near-riot, because the patrons took the marquee billing “Ornette Coleman—Free Jazz” too literally and refused to pay admission.)

After his initial breakthrough, Coleman continued to push boundaries, in his own idiosyncratic way. He introduced more accomplices fluent in his language, like the cornet player Bobby Bradford and the tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman, two other native Texans who combined bluesy melodicism with searching improvisatory flight, as featured on Coleman’s brilliant 1971 album “Science Fiction.” He brought in his then ten-year old son Denardo to play drums on several late-sixties recordings, prioritizing a child’s joyful musical curiosity rather than technical expertise—and continued that familial collaboration for the rest of his life, as Denardo matured into one of his most frequent and trusted collaborators. Coleman taught himself how to play violin and trumpet, adding new colors to his improvisational palette—while he did not play traditionally, he coaxed sounds out of those instruments that were wholly his own and beautifully inimitable.

He composed for orchestra (“Skies of America”) and for trumpet and string quartet (“The Sacred Mind of Johnny Dolphin”), and he played with The Master Musicians of Jajouka and on film scores (“Naked Lunch”). In the nineteen-seventies, he embraced the possibilities of electric ensembles, mentoring a crew of young musicians that included James ‘Blood’ Ulmer, Bern Nix, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, and Ronald Shannon Jackson and creating Prime Time, a band that turned funk into Coleman’s own harmolodic fantasy. On extraordinary recordings such as “Body Meta” and “Dancing in Your Head,” Coleman layered line upon line and rhythm upon rhythm, trusting that the inherent beauty of his melodies and the relentless pulse of his rhythms would be amplified, not obscured.

The first time I saw Ornette Coleman in concert was at the San Francisco Jazz Festival in 1993, a double bill of a revamped Prime Time (with doubled keyboards, guitars, basses, and percussion) and a new acoustic quartet with the pianist Geri Allen, the bassist Charnett Moffett (the son of Coleman’s longtime drummer Charles Moffett), and Denardo on drums. During the intermission, Coleman invited an extreme-body-modification performance artist named Fakir Musafar to offer a demonstration—which featured young people in various states of undress being pierced through the cheeks, breasts, and other seemingly un-pierceable body parts. (My favorite line from the shocked jazz-festival crowd: “Jesse Helms is on the phone—he wants to talk about your funding!”). I later read in an interview that Coleman was interested in the ability of the body to overcome pain; what most saw as courting controversy was actually yet another example of his continual curiosity. And the music reflected that ongoing search. With two keyboards, a classical acoustic guitar, and a tabla, Prime Time had morphed from free-funk propulsion to a thick, impressionistic stew; the acoustic quartet with piano mirrored a classic jazz format yet remained untethered fom jazz cliché. Neither set sounded like anything I’d heard from Coleman before, but both sounded like nothing but Ornette Coleman.

The final time I saw Coleman live was at Carnegie Hall in 2006, this time in yet another unique ensemble—a quintet with Coleman, three bassists, and Denardo again on drums. With that much activity on the sonic bottom, the music was a marvelously oblique rumble, a tangle of thick roots over which Coleman’s alto blossomed. He was seventy-six years old at the time, but his sound, his whole concept, sounded impossibly fresh yet familiar. I remember he closed the concert with an encore of “Lonely Woman,” perhaps his most famous composition and a gesture to his past. As ever, the music was deceptively simple and implacably radical. Ornette Coleman ignored the boundaries between high art and folk music, between modernism and tradition; he recognized that the most human impulse is to explore and search for beauty. It is to all of our benefit that his own search was so fruitful.

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/…/legendary-ornette-co…

ORNETTE: IN ALL LANGUAGES

(For Ornette Coleman)

by Kofi Natambu

song while resting in the lilting liquid light

that becomes him

His sound a heady rhythmic

nomenclature on starry melodic nights

His horn erupts into turquoise flames

A turning toward Terror is not his style though he

casually conjures tempestuous histories

soaring over smokey black earths

Bluesy constellations emerging from our most hidden

desires

Poem by Kofi Natambu

(From: The Melody Never Stops, Past Tents Press, 1991)

The Blues in 4-D

by Kofi Natambu

Detroit Metro Times

June, 1982

A Review of 'Of Human Feelings'

Ornette Coleman & Prime Time

Antilles Records 1982

That is why Coleman’s latest recording, Of Human Feelings, is such an inspiring triumph. In this record we get an intimate look at a brilliant musician/composer organizing the varied elements of his music into a multi-tonal mosaic of great power, humor, color, wit, sensuality, compassion and tenderness. The fact that Ornette has once again managed to create such intelligent and passionate music using only the most venerable and fundamental of all African-American “forms” (i.e. the Blues) as an aesthetic focus is cause for celebration in a culture that worships gimmicks and cant over vision and heart. It is also an indication that like all truly “great artists,” Ornette recognizes and uses the eternal value(s) of simplicity. Of course, as any working artist can tell you, this is one of the most difficult things to do. Luckily for the rest of us, this is Coleman’s strength.

In this record, Ornette and his now six-year-old Prime Time Band never lose sight of the essential conceptual and spiritual aspects of Ornette’s musical philosophy: “Play the music, not the background.” In the eight pieces on this recording, as in all of Ornette’s music, the emphasis is never on virtuoso pyrotechnics for their own sake, or in empty stylistic phrase mongering. In every composition there is a synergy of thought and feeling that communicates instantly. There is always a dynamic unity of structure and execution that is performed with spirit and expressive animation. Coleman’s intricate and functional knowledge of black creative music tradi tions allows him to do this in a deceptively easy manner. The music literally pours out of this ensemble in strains of melody and rhythm that sums up the last 100 years of creative development in Afro-American music.

This awesome command is augmented, in Coleman’s case, with a very strong emotional affinity for the most ancient and basic “folk musics” developed by black people in the New World. Thus, in this recording there are rocking riff figures, field hollers, intensely lyrical worksongs, roaring call-and-response counterpoint, wailing melodic laments and exultations, wry little stompdown ditties and jumptime rent part be-bopping. There are also multi-rhythmic chants, sound clusters, tonal density and instrumental speechmaking. This colorful tapes try is held together by Coleman’s famous Harmolodic method, a theoretical construct that Ornette devised in the early 1970s to “allow all instruments in the band the equal opportunity to lead at any time...” This means that all members of the band can play melodic lines in any key at any time, because structurally the tempo, the rhythm and the harmonics are all equal in terms of what they can express. There is a constant modulation of tonality and rhythms as a result. In this liberated environmental setting the tonal “jumping-off point” is always the Blues, and I mean all kinds of Blues!

Ornette plays every conceivable Blues ever invented and a few that he introduced to the world. In every sound, gesture, cadence and juxtaposition. Coleman reminds us that without the Blues there would be no “jazz,” no “rock,” no “pop,” no “funk,” no “punk.” In short, no American vernacular music, just bland one-dimensional imitations of European, Asian, Latin and African musics. It is a humbling and sobering thought that makes us reflect even as we dance like mad to the throbbing, driving rhythms. Strangely, despite the echoes of Robert Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, Muddy Waters, B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix (among many others) throughout this music, the overall effect is unlike any Blues you have heard before. This is because of what Coleman does with the form in contemporary terms.

Meanwhile, Ornette rides the swelling and descending crest of these tidal waves of melody and sound through keening, darting and singing improvisations that convey a very wise and ancient message. This is the eternal blues message of joyful affirmation in the face of adversity and despair. A “heroism” based on hard-won experience and not media posturing. Whether shouting, screaming, moaning, laughing, crying or sighing, the music in Of Human Feelings never fails to express this message that lifts you higher and makes you dance no matter what “the problem.” The energy derived from the spirit of this recording is the “solution” to our problems. In fact, the title of one of Ornette’s tunes in this recording is “What is the Name of that Song?” I betcha Reagan doesn’t know. I hope we do.

'OF HUMAN FEELINGS'

ANTILLES RECORDING LABEL (1982):

All Compositions by Ornette Coleman:

A1 Sleep Talk

A2 Jump Street

A3 Him And Her

A4 Air Ship

B1 What Is The Name Of That Song?

B2 Job Mob

B3 Love Words

B4 Times Square

Alto Saxophone – Ornette Coleman

Bass Guitar – Jamaaladeen Tacuma

Drums – Calvin Weston, Ornette Denardo Coleman

Guitar – Bern Nix, Charlie Ellerbee

Cover Painting – Susan Bernstein

Recorded on April 25, 1979, N.Y.C.—Released in 1982

https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2010/09/24/130105770/why-we-love-ornette-coleman

Why We Love Ornette Coleman

Ornette Coleman may sit in with some of the performers at "Celebrating Ornette Coleman" this weekend in New York.

PHOTO: Jimmy KatzThis weekend, The Jazz Gallery in New York will host a three-day festival called Celebrating Ornette Coleman. As tributes to the jazz legend go, this one is special.

For one, the lineup is packed with stars and musician's musicians: Mark Turner, Joe Lovano, Nasheet Waits, Johnathan Blake, Kevin Hays and Joel Frahm are leading bands with such sidepersons as Matt Wilson, Seamus Blake, Marcus Gilmore, Stanley Cowell, Avishai Cohen, Joey Baron and more. (The collaborative trio of Vijay Iyer, Matana Roberts and Gerald Cleaver will also perform.) For another, The Jazz Gallery is a small room usually committed to the up-and-coming generation of artists -- this weekend, they'll be packing in artists who often command theaters and weeklong club runs. And as a third, the shows are presented by Jimmy Katz, the jazz portrait photographer and audio engineer. With his wife, Katz raised all the funds; he is also recording the shows, and the musicians will own their masters. There are no guidelines for how each group will play their tributes.

In advance of the performance, I reached out to a number of the artists performing this weekend for their brief thoughts on Ornette Coleman. Here's what I got back.

What makes Ornette Coleman special for you? Leave us a comment.

Mark Turner. Photo: Jimmy Katz

Mark Turner, saxophones: Master Ornette Coleman knows where he comes from, where he is and where he wants to go.

Joe Martin, bass: As a bassist, Ornette's music enlightens how crucial, beautiful, and dramatic the relationship between a bass line and melody is. (Of course melody and bass line counterpoint have always existed, but for me hearing Ornette's music showed me that even without a specific harmony, this said relationship is even more pronounced, perhaps essential.)

Johnathan Blake, drums: Ornette's fearlessness and honesty is a constant inspiration to me. I've always loved the humor that he puts inside his music.

Joel Frahm, saxophone: For me, Ornette is a great example of the power of flow in music; when I listen to him, I feel like he's never out to prove something to anybody. It's more like discovery and reaction. For me, he's hard to talk or write about without feeling like words are completely useless to describe him.

Matt Wilson, drums: Mr. Coleman personifies courage. He persevered through intense scrutiny and criticism to convey his sonic message. That alone is a reason to celebrate this American master.

Did you know that Ornette Coleman once commented at a rehearsal, "Let's find the right temperature for this tune"? Is that hip or what? BIG love to Maestro Coleman!

Matana Roberts, saxophone: Ornette Coleman is a saxophonist in a class all by himself. He stands for what making interesting art is all about -- having a voice all of one's own, but having a creative spirit that is wide open, selflessly nuturing and welcoming to collectivity and celebration of the human experience.

Seamus Blake, saxophone: Ornette has profoundly touched and influenced every important jazz musician since he first recorded in 1958. The genius and stylings of Wayne Shorter, Joe Lovano, Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny and John Scofield as well as many, many more greats owe a great deal to Mr Coleman. He is without a doubt as crucial a figure in jazz as Charlie Parker.

Nasheet Waits, drums: What Ornette Coleman represents to me is a fierce dedication to being yourself. He listens to the inner voice whose source is within and beyond.

Vijay Iyer, piano: Ornette Coleman's music combines conceptual innovation, rigorous detail, and profound emotional resonance. He completely changed the music we know and love, and yet his ongoing impact extends well beyond the "jazz" world, into punk rock, American literature, cinema and contemporary art. To me, the best way to pay tribute to Mr. Coleman is to follow his lead -- i.e., to be radically, audaciously yourself.

ORNETTE COLEMAN SPEAKING:

"It was when I found out I could make mistakes that I knew I was on to something."

"Jazz, rock, pop, blues, gospel, and classical are all yesterday's titles. I'm playing the music of today..."

"Play the music, not the background"

"Sound is to people what the sun is to light"

"You don't have to worry about being a number one, number two, or number three. Numbers don't have anything to do with placement. Numbers only have something to do with repetition."

"Jazz is the only music in which the same note can be played night after night but differently each time."

"That's what I was trying to say when we were talking about sound. I think that every person, whether they play music or don't play music, has a sound - their own sound, that thing that you're talking about."

"It's just someone has labelled us as having a different label to do what you do. I find that labels are the worst thing in the world for artistic expression."

"You've got to realize. In the western world, regardless of what color you are, what title the music is, it's all played by the same notes."

"How can I turn emotion into knowledge? That's what I try to do with my horn."

"The state of surviving in music is more like 'what music are you playing.' But music isn't a style, it's an idea. The idea of music, without it being a style - I don't hear that much anymore."

"There are some intervals that carry that human quality if you play them in the right pitch. I don't care how many intervals a person can play on their instrument; you can reach into the human sound of a voice on your horn if you're actually hearing and trying to express the warmth of the human voice."

"I don't try to please when I play. I try to cure."

Jacques Derrida interviews Ornette Coleman

"Sound has a much more democratic relationship to information"

LEFT: ORNETTE COLEMAN (1930-2015)

"So the comparison between bass and voice I think would be that the melodies that I’m playing on bass, for most listeners, are much more abstract than what I’m singing. We have such an ingrained connection with the human voice, that however I open my mouth and sing, it’s going to have some symbolism or meaning for the listener -- because it’s a voice. The way I breathe, the way I enunciate, even if I’m not singing lyrics, and then when you add lyrics -- okay, so then it’s not abstract at all. I’m actually telling you what I’m talking about, what I’m emoting about. So with the bass, there’s a certain freedom in the abstraction."

-Esperanza Spalding

"I'm trying to express a concept according to which you can translate one thing into another. I think that sound has a much more democratic relationship to information, because you don't need the alphabet to understand music."-Ornette Coleman

(SOURCE: Jazz Studies Online)

On improvisation

Ornette Coleman: "...the idea is that two or three people can have a conversation with sounds, without trying to dominate it or lead it. What I mean is that you have to be .. . intelligent, I suppose that's the word. In improvised music I think the musicians are trying to reassemble an emotional or intellectual puzzle, in any case a puzzle in which the instruments give the tone. It's primarily the piano that has served at all times as the framework in music, but it's no longer indispensable and, in fact, the commercial aspect of music is very uncertain. Commercial music is not necessarily more accessible, but it is limited."

On composing

Ornette Coleman: "If you're playing music that you've already recorded, most musicians think that you're hiring them to keep that music alive. And most musicians don't have as much enthusiasm when they have to play the same things every time. So I prefer to write music that they've never played before..."

"I want to stimulate them instead of asking them simply to accompany me in front of the public. But I find that it's very difficult to do, because the jazz musician is probably the only person for whom the composer is not a very interesting individual, in the sense that he prefers to destroy what the composer writes or says."

On pre-written pieces

Ornette Coleman: "I don't know if it's true for language, but in jazz you can take a very old piece and do another version of it. What's exciting is the memory that you bring to the present. What you're talking about, the form that metamorphoses into other forms, I think it's something healthy, but very rare."

On language

Ornette Coleman: Do you ever ask yourself if the language that you speak now interferes with your actual thoughts? Can a language of origin influence your thoughts?

Jaacques Derrida: It is an enigma for me. I cannot know it. I know that something speaks through me, a language that I don't understand, that I sometimes translate more or less easi¬ly into my "language." I am of course a French intellectual, I teach in French-speak¬ing schools, but I have the impression that something is forcing me to do something for the French language...

Ornette Coleman: But you know, in my case, in the United States, they call the English that blacks speak "ebonics": they can use an expression that means something else than in current English. The black community has always used a signifying language. When I arrived in California, it was the first time that I was in a place [milieu] where a white man wasn't telling me that I couldn't sit somewhere. Someone began to ask me loads of questions, and I just didn't follow, so then I decided to go see a psychiatrist to see if I understood him. And he gave me a prescription for Valium. I took that valium and threw it in the toilet. I didn't always know where I was, so I went to a library and I checked out all the books possible and imaginable on the human brain, I read them all. They said that the brain was only a conversation. They didn't say what about, but this made me understand that the fact of thinking and knowing doesn't only depend on the place of origin. I understand more and more that what we call the human brain, in the sense of knowing and being, is not the same thing as the human brain that makes us what we are." (source / pdf)

http://www.npr.org/2007/04/16/9607210/ornette-coleman-wins-music-pulitzer

Ornette Coleman Wins Music Pulitzer

Ornette Coleman has won the Pulitzer Prize for music with his recording Sound Grammar, a document of a 2005 concert recorded live in Italy.

Ornette Coleman, 77, has won the 2007 Pulitzer prize for music. Getty Images

Coleman's music was not among the 140 music nominees. Pulitzer panelists used their prerogative to skirt traditional rules by purchasing the CD and nominating the 77-year-old jazz master. This is the first time a recording has won the music Pulitzer, and a first for purely improvised music. The concert features an unorthodox line-up of instruments, including two double basses (one plucked, the other bowed), Coleman's son Denardo on drums, and Coleman himself playing alto saxophone and trumpet. Coleman has continued to shake up the jazz world ever since releasing his innovative recording The Shape of Jazz to Come in 1959. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1930, Coleman received his first saxophone at age 14. His mother saved money to buy the instrument by working as a seamstress. At first, Coleman struggled to find his own sound on the alto saxophone, but eventually developed his own formulas of composition, breaking down traditional definitions of harmony and melody. The concept, called "Harmolodic," Coleman says, removes the caste system from sound. Coleman has written music outside of the jazz realm, including string quartets, music for dance, woodwind quintets, and in the early 1970s, a symphony called Skies of America, composed with support from his Guggenheim Foundation Grant.

In 1994, Coleman earned a MacArthur Genius award, and has been inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Related NPR Stories:

Featured Artist:

Ornette Coleman's Pulitzer-winning

recording features:

Ornette Coleman: saxophone, violin, trumpet

Denardo Coleman: drums;

Gregory Cohen and Tony Falanga: basses

Ornette Coleman's 'Sound Grammar' first jazz work awarded Pulitzer Prize

Associated Press

April 24, 2007

NEW YORK -- Ornette Coleman won the Pulitzer Prize for music on Monday for his 2006 album, "Sound Grammar," the first jazz work to be bestowed with the honor. The alto saxophonist and visionary who led the free jazz movement in the 1950s and 1960s, won the Pulitzer at age 77 for his first live recording in 20 years. The only other jazz artist to win a Pulitzer is Wynton Marsalis, who won in 1997 for his classical piece, "Blood on the Fields."

The Pulitzer Prize for music, an award founded in 1943, has always focused on classical music. Legendary jazz composers Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk were honored only with posthumous citations in 1999 and 2006, respectively. In 2004, Pulitzer administrators decided to expand the criteria for the music prize, encouraging a broader range of music that included jazz, musical theater and movies.

Coleman, who grew up poor in a largely segregated Fort Worth, Texas, didn't first believe his cousin when he told Coleman that he had won the Pulitzer. He spoke by phone to The Associated Press from his New York City home minutes after hearing the news, and reflected on his long, unlikely journey. "I'm grateful to know that America is really a fantastic country," said the jazz legend, recalling when he first asked his mother for a saxophone. "And here I am." What began for Coleman as a fascination for the bebop of Charlie Parker, led him on a path to discover -- through music -- what he calls "the culture of life and intelligence." On "Sound Grammar," which was recorded at a 2005 concert in Ludwigshafen, Germany, Coleman also plays trumpet and violin. He was awarded a Grammy lifetime achievement award in February. "Of all the languages that human beings are speaking on the planet, it's some form of grammar," Coleman said of his album. "For me, playing music is analyzing grammar." Though Coleman can speak of large, heady ideas in a way not dissimilar from his often conceptual music, he said he has never wanted to be inaccessible. "I've been doing what I think I'm trying to achieve ever since I was teenager and I was only doing it because of the quality of human beings," Coleman said. "I've never really thought about being smart; I've only really thought about being good." Some members of the Pulitzer board such as Jay Harris, a professor at the University of Southern California, have said the Pulitzers have "effectively excluded some of the best of American music" by concentrating fully on classical works. Coleman's win suggests that may be changing. When asked whether he hopes more jazz musicians will follow him in winning Pulitzers, Coleman replied, "I would like to help them if I could." On the Net: http://www.pulitzer.org

(Originally posted on March 9, 2011):

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

THE LEGENDARY ORNETTE COLEMAN (b. 1930)

HAPPY 81ST BIRTHDAY ORNETTE!

It is impossible to overstate the monumental significance of the astonishing musical art and vision of the consummate musician, composer, arranger, conductor, multi-instrumentalist, philosopher, music theorist, and prophet Ornette Coleman (b. March 9, 1930 in Fort Worth, Texas). For over 50 years (!) Ornette has been a major innovator in, and creative influence on, the rich global history of improvisational and structured ensemble music alike. A grandmaster of the myriad forms, genres, and expressive/conceptual traditions and strutural legacies of Jazz, Blues, R & B, Funk, 'classical' 'Pop', and spiritual musics Coleman has left an indelible mark on the art world generally through not only his many extraordinary recordings and live performances throughout the U.S., Asia, Europe, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Pacific islands but through his electrifying and highly original creative collaborations with singers, dancers, painters, poets, visual artists (film and painting), architects, scientists, actors, martial artists, and playwrights. In celebration of the 81st birthday of this truly great artist and amazing human being what follows are a series of writings and commentary by and about Ornette by a number of different sources including critics, fellow artists, and historians. I have also contributed some of my own writing on and about Ornette and his music over the years. ENJOY...

Kofi

My biography of musician/composer Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) has struck a chord…paperback edition to be released in April 2022

Ornette nominated Best Book of 2020 by the Jazz Journalist Association, along with Philip Clark’s Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time, Will Friedwald’s Straighten Up and Fly Right; Phil Woods with Ted Panken’s Life in E Flat, Mark Ruffin’s Bebop Fairy Tales and Kevin Whitehead’s Play the Way You Feel. Ornette also nominated for JJA’s Robert Palmer – Helen Oakley Dance Award for Excellence in Writing in 2020.

Roughtrade.com, catering to music connoisseurs of all stripes, named Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure one of its ten favorite books of 2020, along with The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America, Chris Frantz, Remain In Love (Talking Heads), and Barack Obama’s Promised Land (?!).

The elegantly leftist Counterpunch.org also named Ornette one of the top books of 2020, along with Eric Holthaus’s Future Earth, Oliver Stone’s Chasing the Light, and JoAnn Wypijewski’s What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About #metoo.

‘One of the book’s virtues lies in its foregrounding of Coleman’s voice and the voices of his contemporaries…an important contribution to Coleman scholarship…a thoughtful and eminently readable account of a monumental artist.’ -Mark Mahoney, Jazz and Culture, pdf here.

‘A labor of love and a thoroughly researched, righteous homage…. Golia gets Coleman’s ravenous intellectual curiosity. Her prose is sometimes dense with context, sometimes poetic and exalted, sometimes punchy (“Jim Crow could not dictate what kind of music a person listened to.”). She gets that Ornette was never only a jazz musician. He was a thinker, a futurist, a cultural revolutionary.’ – Kathelin Gray, Los Angeles Review of Books. Gray produced of several of Ornette’s records, including “In All Languages” (1987) and of the film “Ornette Made in America” (dir. Shirley Clarke, 1986). Full review here.

‘Fittingly unconventional. . . . Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure is an atlas in prose, a guide to the territories of varied sorts—social, racial, aesthetic, economic and even geographic—that Coleman came out of, traveled through, lived near, occupied, left behind or transformed.’ – David Hadju, New York Times Book Review. Full review here.

‘[Ornette Coleman] was the shock of the new… Golia writes scenically about Coleman’s birthplace, Fort Worth, Texas, where Jim Crow and music were everywhere… With a pointillist’s talent for detail, [she] shows how Coleman’s origins in Texas blues gave way to abstraction on landmark records … ultimately leading him to create the musical paradigm he called “harmolodics.”… The “free” in [Coleman’s] “free jazz” is an ambivalent word. It doesn’t refer to the absence of oppression or musical rules, but instead the struggle to imagine a place beyond them both. In that sense, Coleman’s definition of freedom was radically inclusive, both politically and musically.’ – Josephine Livingstone, The New Republic Full review here

‘One of the finest books on the power of place and influence in a musician’s life.’ — Andrew Male, Mojo (UK)

‘Golia marshals her account with a deft touch and in very fluent and elegant style.’ – Jazz Centre Newsletter, Centrepiece (UK).

Ms. Golia aptly outlines the aesthetic dilemma, when “jazz had become aware of itself and its strengths” …[and] writes with demystifying clarity about the manifestations of compassion and rigor behind Coleman’s search for “unison” and the musical system he called “harmolodics.” [She] notably grounds Coleman’s identity in his hometown, reconstructing an “idiosyncratic collage of radio broadcasts from Harlem, Western Swing fiddlers, Tejano two-steps, high-school marching bands, and the rhythm and blues that issued from storefront churches”…[Ornette Coleman, the Territory and the Adventure] opens ears yet further to the transformative power of Coleman’s music. – Larry Blumenfeld, Wall St. Journal Download PDF here.

‘A professional account of a heady dude, without cosmic junk and jargon.’ -Colin Fleming, Jazz Times, (USA)

‘[Unlike previous books about Ornette] Golia takes a broader approach, situating the great saxophonist and composer in his cultural, social and geographical contexts. Each of the four sections pivots on a particular time and place, establishing the territory then striking out on an adventure in a manner akin to a Coleman solo . . . By deftly tracing these connections and transformations, Golia has created a valuable and highly engaging survey of Coleman’s harmolodic life.’ – Stewart Smith, The Wire (UK) Download PDF Oc.review.theWire‘

‘A wide-ranging biography of the great saxophonist, and musical tendencies that converged to make him the “patron saint of all things dissonant and defiant.”‘ Julian Lucas, Harper’s Magazine