AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2022/01/valerie-coleman-b-1970-outstanding.html

PHOTO: VALERIE COLEMAN (b. 1970)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/valerie-coleman-mn0002225497/biography

Valerie Coleman

(b. 1970)

Artist Biography by James Manheim

Composer and flutist Valerie Coleman has gained wide recognition for music that fuses classical styles with African American vernacular elements. She founded the wind quintet Imani Winds and has recorded frequently with that group.

Coleman was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1970, and grew up in the same West End neighborhood that had been home to boxing great Muhammad Ali. She grew up poor and took to the flute even before she had regular access to the instrument, playing with sticks in her yard and pretending they were flutes. At 11, she began formal musical education, not only on the flute but as a composer; working with a portable organ at home, she wrote three symphonies by the time she was 14. Coleman attended Boston University, earning a double degree in theory/composition and flute performance. She went on to the Mannes College of Music in New York, where her flute teachers included Julius Baker and Judith Mendenhall; she studied composition with Martin Amlin and Randall Woolf. Coleman founded Imani Winds in 1997, hoping to provide role models for young African American wind players. The group has been durably successful, earning a Grammy award nomination in 2005 for its album The Classical Underground.

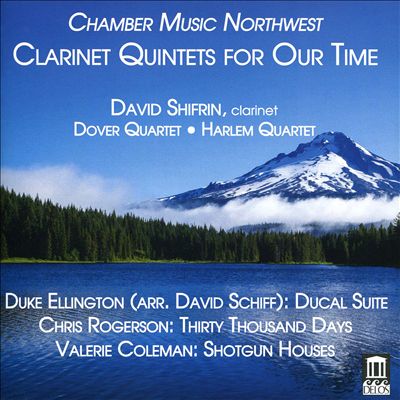

As a solo flutist, Coleman served in the early 2000s as understudy to Eugenia Zukerman at Lincoln Center in New York. She has also appeared at Alice Tully Hall in New York, Kennedy Center in Washington, and the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, among other prestigious venues. Her compositions are mostly for wind quintet (she has served as Imani Winds' resident composer), other chamber ensembles, band, orchestra, and solo flute. Her works have been recorded on the Cedille, BMG France, Sony Classics, eOne (formerly Koch International Classics), and Naxos labels, and in 2019, her Shotgun Houses was included on the Chamber Music Northwest collection Clarinet Quintets for Our Time. In 2002, Coleman's wind quintet Umoja was listed among the Top 101 Great American Works by Chamber Music America.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valerie_Coleman

Valerie Coleman

Valerie Coleman | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Louisville, Kentucky, |

| Genres | Classical, Jazz, Soul |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, Flutist, Educator |

| Instruments | Flute |

| Years active | 1997-present |

| Labels | Naxos Records Blue Note Records E1 Music |

| Associated acts | Imani Winds |

| Website | VColemanMusic.com |

Valerie Coleman is an American composer and flutist as well as the creator of the wind quintet, Imani Winds. Coleman is a distinguished artist of the century who was named Performance Today's 2020 Classical Woman of the year and was listed as “one of the Top 35 Women Composers” in the Washington Post. In the year 2019, Valerie Coleman composed a piece titled Umoja, Anthem for Unity which was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. This achievement was a very special one because it was the first time that a living African-American woman composer was commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Coleman is known for her many contributions to wind chamber music and with Imani Winds, she released a number of studio albums with the group, one of which was nominated for Grammy Award for Best Classical Crossover Album in 2005.[1]

A graduate of Mannes College of Music and taught by musicians such as Julius Baker, her compositions frequently incorporate diverse styles such as jazz with classical music and many times incorporate political or social themes. Her piece Umoja in 2002 was listed as one of the "Top 101 Great American Works" by Chamber Music America.[2] She is an alumna of Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center CMS Two Fellowship program, laureate of Concert Artists Guild competition.

Valerie is a highly sought-after recitalist and clinician with a reputation of transformative skill and has conducted masterclasses and performances at top institutions.

Early life and education

Valerie Coleman was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, in the same West End inner city neighborhood that Muhammad Ali grew up in.[3] Her father died when she was nine, and her mother raised Coleman and her sisters as a single working mother.[4]

Even as a toddler, it was clear that Valerie Coleman had a love for music and a great interest in playing the flute. Coleman even recollects picking up sticks in the backyard and pretending they were flutes. She started her formal music education in fourth grade,[4] at age eleven.[3] During her early years as a young musician, Coleman was interested in composing music. This love for composing grew and she started writing symphonies as a hobby,[4] using a portable organ that she had at her home.[5] By age fourteen she had written three full-length symphonies and won several local and state competitions,[2] as well as participating as a flutist in youth orchestra.[4] She is a graduate of Louisville Male High School.

Coleman and all her sisters attended college, and she earned[6] a double B.A. in theory/composition and flute performance from Boston University. She then graduated with a Masters Degree in flute performance from Mannes College of Music. Coleman studied flute with Julius Baker, Alan Weiss, Judith Mendenhall, Doriot Dwyer, and Mark Sparks, and composition with Martin Amlin and Randall Woolf.[2]

Imani Winds

In 1996, while still a student, Coleman began planning a chamber music ensemble.[7] She chose the name Imani Winds, Imani being the Swahili word for faith,[6] and sought African American woodwind players who might approach classical music from a similar cultural background.[7] About her reasons for starting the ensemble:

I used to be in the youth orchestra [as a child], and there were so many African Americans. But somewhere along the line, when I got to college, I was the only one in the orchestra. So I wondered what in the world happened here? It came to my mind that role models are needed.

The group grew to five people, with Coleman on flute, Torin Spellman-Diaz on oboe, Monica Ellis on bassoon, Mariam Adam on clarinet, and Jeff Scott on french horn.[4] From the beginning the ensemble focused on "championing composers that were underrepresented from the non-European side of contemporary music."[7] The repertoire frequently involves music that is inspired by many different cultures including influences from the music of Africa, Latin America and North America.[6]

Accolades

By 2001 the group had won the Concert Artists Guild competition,[6] and over the following years released five albums internationally on the E1 Music label (formerly known as Koch International Classics), with many of those tracks composed by Coleman herself.[3] About their musicianship, the New Orleans Times Picayune stated, "As an ensemble, the Imani Winds cultivate the big, rich sound one associates with classical players -- and they also display the daring, respond in-the moment qualities one associates with a swinging jazz combo."[1]

The ensemble was named resident-artists of Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and has appeared in major concert halls throughout the United States.[6] The ensemble has won awards from Artists International and the 2005 ASCAP/WQXR-FM Award for Adventurous Programming, and were honored at the 2007 ASCAP Concert Music Awards.[3]

NPR Music named their album Terra Incognita one of the "5 Best American Contemporary Classical Albums Of 2010," saying "Imani Winds' members have earned a reputation for expanding the recorded wind-quintet repertoire, but in a way that's culturally significant."[1] According to the Cleveland Classical, "Imani Winds have carved a unique path into the world of classical chamber music for themselves through inventive programs, commissioning projects, and educational activities, and above all superb musicianship."[1]

Imani Winds Chamber Music Festival (IWCMF)

In 2009 Coleman conceived and created the Imani Winds Chamber Music Festival, which is both an institute and chamber music series on the Lincoln Center Campus in New York City.[8] The festival attracts artists from all around the world, who come to be mentored by Imani Winds and explore different paths of chamber music performance and repertoire.

The third annual festival was opened with Coleman's composition "Tzigane," which according to Lucid Culture, "made a deliciously high-octane opening number: an imaginative blend of gypsy jazz and indie classical with intricately shifting voices, it was a showcase for the entirety of the ensemble."[1]

In 2012 composers were added to the roster through the Emerging Composers Program. It involved master classes with composers such as Mohammed Fairouz and Daniel Bernard Roumain,[8] and the panel of guest artists included Stefon Harris, Paula Robison, Carol Wincenc, and Stanley Drucker.[8]

Solo career

Coleman made her debut as a flutist/composer at Carnegie Hall in 2004,[5] and prior to that was the understudy for flutist Eugenia Zukerman at Lincoln Center. Coleman was also a featured soloist in the Mannes 2000 Bach Festival.[2] Throughout Coleman's career, she has had performances and premieres that have taken place in major music halls across the country such as Alice Tully Hall, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, The Kennedy Center, Chamber Music Northwest, and Philadelphia Chamber Music Society.[3]

Her compositions and performances receive regular play on classical radio stations in the United States,[3] and she has been showcased on the New York classical radio station WQXR.[2] She also appeared on NPR's Performance Today, All Things Considered, and The Ed Gordon Show; WNYC's Soundcheck, and MPR's Saint Paul Sunday.[3] In April 2008 she was featured in Flutist Quarterly.[5]

She has received commissions from orchestras and ensembles as diverse as San Francisco Chamber Orchestra, Brooklyn Philharmonic, The National Flute Association, Hartford Symphony Orchestra, College Band Director's National Association, West Michigan Flute Association, and The Flute and Clarinet Duos Consortium.[3]

She has been a teacher for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, has served on the faculty of The Juilliard School's Music Advancement Program and Interschool Orchestras of New York.[2] She's given flute masterclasses at colleges such as SUNY Purchase, Columbus State, UMass Amherst, Ohio State, Ithaca College, Utah State, Norfolk State, and Hampton University,[3] She has also been a composer/flutist in residence with Young Audiences NYC, and completed a mentorship with the Brooklyn Philharmonic.[3] Coleman is on the advisory panel of the National Flute Association.[2]

Compositions

Coleman is the resident composer of Imani Winds, though the ensemble also incorporates the work of other members and composers. Coleman's style mixes modern orchestration with genres as diverse as jazz and Afro-Cuban.[3] She has added a number of works to the flute repertory, also contributing to the literature for wind quintet, full orchestra, woodwinds, brass, and strings, many of which have been published by International Opus.

She often interposes music with the words of historical figures and poets, in some cases using manipulated speeches of people of diverse as Robert F. Kennedy, A. Philip Randolph and Cesar Chavez.[9]

About her world premiere of Painted Lady, a set of two songs for orchestra and soprano and her first commission, The Hartford Courant said "The songs are luminous works, with a tangy but accessible harmonic language, graced with a humanizing sense of melodic line and a mildly exotic rhythmic lilt. They are the work of a major talent, and they should be recorded immediately."[9] The songs used words by African American poet Margaret Danner.[9]

Her signature wind quintet piece Umoja (named for the Swahili word for "unity") in 2002 was listed as one of the "Top 101 Great American Works" by Chamber Music America.[2] Josephine Baker: A Life of le Jazz Hot in 2007 traced the life Josephine Baker,[4] receiving a glowing response in publications such as the Philadelphia Inquirer.[9]

Academia

Frost School of Music

In 2018, Coleman was appointed as Assistant Professor of Performance, Chamber Music, and Entrepreneurship; and Director of the Chamber Music program at Frost School of Music, at the University of Miami (FL).

Mannes School of Music

In 2021, Coleman was appointed a Clara Mannes Fellow within the Flute Performance and Music Composition faculty at Mannes School of Music, at The New School in New York City.

Awards

- Aspen Music Festival Wombwell Kentucky Award[2]

- Michelle E. Sahm Memorial Award at the Tanglewood Music Festival[2]

- Meet The Composer's Edward and Sally Van Lier Memorial Fund Award, 2003[3]

- the Wombwell Kentucky Award for study at the Aspen Music Festival, 2003[3]

- Michelle E. Sahm Award for flutists, 2003[3]

- Received the Multi-Arts Production Fund - a grant given to "support

innovative new works in all disciplines and traditions of performing

arts."[2]

List of compositions[10]

Wind quintet

- 2001: UMOJA

- 2002: speech. and canzone

- 2005: Afro-Cuban Concerto

- 2006: Suite: Portraits of Josephine - 4 Movements

- 2009: Red Clay and Mississippi Delta - Scherzo

- 2011: Tzigane

- Arrangements

- "Afro Blue - Mongo Santamaria"

- "NKOSI SI KE LEL 'I AFRIKA - Enoch Sontaga" (South African national anthem)

- Spirituals, Vol.1 ("Every Time I Feel the Spirit", "Steal Away", "Little David Play on Your Harp")

- "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing"

- Various holiday songs

Chamber music

- 2003: UMOJA for wind sextet

- 2005: Sonatine for Clarinet and Piano

- 2006: Maombi Asante - A Prayer of Thanksgiving for flute, violin, and cello

- 2006: Suite: Portraits of Josephine - A Ballet in 8 Movements for chamber ensemble

- 2007: Suite: Portraits of Langston for flute, clarinet & piano

- 2007: LENOX AVENUE for clarinet, violin, cello, and piano

- 2008: Des Filmes Epiques for wind and string quartet

- 2009: Our God of Voiceless Things for choir, wind quintet, and jazz ensemble

- 2011: Four Winds of Ol' Forester for flute, violin, cello and mp3

- 2012: Rubispheres for flute, clarinet and bassoon

- 2012: Ruby St. Nola for three C flutes

- Pontchartrain for flute choir

Orchestral

- 2005: The Painted Lady

- 2018: Phenomenal Women

- 2019: UMOJA

- 2020: Seven O'Clock Shout

Concert band

- 2008: UMOJA

- 2009: ROMA

- 2013: Arabia for intermediate concert band

Solo flute

- 2011: Danza de la Mariposa (Theodore Presser)

Discography

Imani Winds

- Studio albums

- 2002: Umoja

- 2005: The Classical Underground (E1 Music)

- 2006: Imani Winds (E1)

- 2007: Josephine Baker: A Life of le Jazz Hot (E1)

- 2008: This Christmas with Imani Winds (E1)

- 2010: Terra Incognita (E1)

- 2013: Mohammed Fairouz: Native Informant (Naxos Records)

- 2013: Without a Net (Blue Note Records)

Personal life

Coleman lives with her husband, Jonathan Page, and daughter, Lisa.[3]

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/the-classical-underground-imani-winds-koch-records-review-by-russ-musto

Imani Winds: The Classical Underground

| Play Imani Winds on Amazon Music Unlimited (ad) | |

Imani Winds is a contemporary woodwind quintet whose music is quietly

breaking down the artificial barrier between the classical and jazz

idioms. The group's members—Valerie Coleman (flute), Toyin Spellman

(oboe), Mariam Adam (clarinet), Monica Ellis (bassoon), and Jeff Scott

(French horn)—are young Afro-Americans intent on integrating their

American Negro and Afro-Caribbean musical traditions into their chosen

field of creative expression.

The disc opens with Scott's

arrangement of Astor Piazzolla's "Libertango, which adds percussionist

Rolando Morales Matos on cajon, emphasizing the group's desire to make

the classical canon more open to non-European influences. The album's

centerpiece, Paquito D'Rivera's "Aires Tropicales, is a most appropriate

vehicle for the quintet. The piece includes movements utilizing

traditional Cuban melodies ("Son and "Habanera ), jazz ("Dizzyness

references Gillespie's "Night In Tunisia and "Tin Tin Deo ), and

European music ("Contradanza ). The final movement, "Afro, arranged by

Scott, features René Marie's vocals and Matos' conga drums in a rhythmic

melding of seemingly disparate influences.

Valerie Coleman's

arrangement of the traditional spiritual "Steal Away (the title track of

pianist Larry Willis' excellent collaboration with Gary Bartz) and her

own "Concerto for Wind Quintet reveal the flutist's original conception,

considerable creativity, and ability to compose new music that is both

beautiful and exciting. The multitalented Lalo Schifrin's "La Nouvelle

Orleans, an appealing piece, commemorating the birthplace of jazz, is

expertly interpreted by the ensemble. The concluding "Homage To Duke, by

Jeff Scott, is an exploration and expansion of Ellington's rich tonal

palette.

Track Listing

1. Astor Piazzolla: Liber Tango (arr. Jeff Scott); 2. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Alborada; 3. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Son; 4. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Habanera; 5. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Vals Venezolano; 6. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Dizzyness; 7. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Contradanza; 8. Paquito D'Rivera: Aires Tropicales: Afro (arr. Jeff Scott); 9. traditional spiritual: Steal Away (arr. VColeman); 10. V. Coleman: Concerto for Wind Quintet: Afro; 11. V. Coleman: Concerto for Wind Quintet: Vocalise; 12. V. Coleman: Concerto for Wind Quintet: Danza; 13. Lalo Schifrin: La Nouvelle Orleans; 14. Jeff Scott: Homage to Duke.

Personnel

Valerie Coleman - flute; Mariam Adam - clarinet; Toyin Spellman - oboe; Monica Ellis - basson; Jeff Scott - French horn.

Album information

Title: The Classical Underground | Year Released: 2005 | Record Label: KOCH Records

https://www.pcmsconcerts.org/composer/valerie-coleman/

Valerie Coleman

Valerie Coleman is the founder, flutist and resident composer of the Grammy nominated Imani Winds. Through her music and vision, she has created a legacy of innovation that breaks down cultural and social barriers in classical music.

A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Coleman began her music studies at the late age of eleven. By the age of fourteen, she had already written three full-length symphonies and had won a number of local and state flute competitions. Today, her works and performances are heard regularly on Classical radio stations throughout the country: Sirius XM, NPR’s Performance Today, All Things Considered, and The Ed Gordon Show; WNYC’s Soundcheck, MPR’s Saint Paul Sunday, and globally through Radio France. Recently, Coleman took on a new challenge of being the Artistic Director of her own creation, The Imani Winds Chamber Music Festival, a highly successful summer training series and institute in New York City that serves as an advocate for aspiring musicians and young composers.

She is best known for Imani Winds’ signature piece Umoja, which was listed as one of the “Top 101 Great American Works” by Chamber Music America. Many of her contributions to wind literature are considered standard modern repertoire and are performed by ensembles globally. Commissions and/or highlight performances of her works include a Carnegie Hall debut in 2001, Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra 2001, New Haven Symphony, Composer’s Concordance Festival Orchestra, Music of NOW at Symphony Space Thalia, Wigmore Hall in London, The Kennedy Center, Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, among many others. Awards include the Aspen Music Festival Wombwell Kentucky Award, Michelle E. Sahm Memorial Award at the Tanglewood Music Festival (inaugural recipient), The Sally Van Lier Memorial Award, and the Multi-Arts Production Fund (MAPFUND). As both composer and flutist, she has been featured as a guest artist at Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Chamber Music Northwest, Chenango Music Festival, Bravo! Vail Music Festival, and Alice Tully Hall among several others.

Currently, she serves on the New Music Advisory Committee of National Flute Association, the Classical Connections Committee of Association of Performing Arts Presenters (APAP), serves as an Artistic Advisor for the Hartt School at the University of Connecticut, and is on the boards of the COR Music Project, and Composer’s Concordance. She is published by Theodore Presser International Opus, and maintains her own publishing company, V Coleman Music. Valerie currently resides in New York City with her husband Jonathan Page and baby daughter Lisa.

Imani Winds "Terra Incognita" promotional video

https://imaniwinds.com/press-blog/2016/9/12/wayne-shorter-quartet-without-a-net

Imani Winds "Terra Incognita" promotional video

Wayne Shorter's Terra Incognita - La Jolla Music Society's SummerFest 2006

Valerie Coleman

composer

“Described as one of the “Top 35 Female Composers in Classical Music” by critic Anne Midgette of the Washington Post, Valerie Coleman (B. 1970) is among the world’s most played composers living today. Whether it be live or via radio, her compositions are easily recognizable for their inspired style and can be throughout venues, institutions and competitions globally. The Boston Globe describes Coleman as a having a “talent for delineating form and emotion with shifts between ingeniously varied instrumental combinations” and The New York Times observes her compositions as “skillfully wrought, buoyant music”. With works that range from flute sonatas that recount the stories of trafficked humans during Middle Passage and orchestral and chamber works based on nomadic Roma tribes, to scherzos about moonshine in the Mississippi Delta region and motifs based from Morse Code, her body of works have been highly regarded as a deeply relevant contribution to modern music.

A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Valerie began her music studies at the age of eleven and by the age of fourteen, had written three symphonies and won several local and state performance competitions. She is the founder, creator, and former flutist of the Grammy® nominated Imani Winds, one of the world’s premier chamber music ensembles, and is currently an Assistant Professor of Performance, Chamber Music, and Entrepreneurship at the University of Miami. Through her creations and performances, Valerie has carved a unique path for her artistry, while much of her music is considered to be standard repertoire. She is perhaps best known for UMOJA, a composition that is widely recognized and was listed by Chamber Music America one of the “Top 101 Great American Ensemble Works”. Coleman has received commissions from Carnegie Hall, American Composers Orchestra, The Library of Congress, the Collegiate Band Directors National Association, Chamber Music Northwest, Virginia Tech University, Virginia Commonwealth University, National Flute Association, West Michigan Flute Society, Orchestra 2001, The San Francisco Chamber Orchestra, The Brooklyn Philharmonic, The Flute/Clarinet Duos Consortium, Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Chamber Music Northwest, and the Interlochen Arts Academy to name a few.

With over two decades of conducting masterclasses, lectures and clinics across the country, Valerie is a highly sought-after clinician and recitalist. Recently, she has immensely enjoyed being the featured guest artist of flute fairs around the country, such as Mid-South, South Carolina, Colorado, New Jersey, and Mid-Atlantic, and was also featured as an artist in residence at Boston University Tanglewood Institute, LunArts Festival, and the National Women’s Music Festival. Future appearances include Florida Flute Society, Portland, Seattle, Long Island and North Carolina Flute Fairs, and residencies at Yale, University of North Dakota, Virginia Tech, and many more. With her ensemble, she was recently an artist-in-residence at Mannes College of Music, served on the faculty of Banff Chamber Music Intensive and was a visiting lecturer at the University of Chicago. She is regularly featured as a performer and composer within many of the world’s great concert venues, series and conservatories: Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Kennedy Center, Walt Disney Hall, DaCamera Houston, Boston Celebrity Series, Krannert Center, Wigmore Hall, Montreal Jazz Festival, North Sea Jazz Festival, Paris Jazz Festival, The Juilliard School, The Eastman School, Curtis, Peabody, Mannes, The Colburn School and countless more. She has recorded with Wayne Shorter, Paquito D’Rivera, Jason Moran, Steve Coleman, Vijay Iyer, Stefon Harris, Chick Corea and more. She and her ensemble have enjoyed collaborations with Gil Kalish, Paula Robison, Yo-Yo Ma, Anne Marie McDermott, Alexa Still, Ani and Ida Kavafian, David Shifrin, Wu Han, Simon Shaheen, Sam Rivers and many more. Her music is frequently “on the air” with National and local Classical radio stations and their affiliates: Sirius XM, NPR’s Performance Today, All Things Considered, and The Ed Gordon Show; WNYC’s Soundcheck, and MPR’s Saint Paul Sunday. She has received awards and/or honors from the National Flute Association, The Herb Alpert Awards, MAPFUND, ASCAP Concert Music Awards, NARAS, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Edward and Sally Van Lier Fund, Artists International, Wombwell Kentucky Award, and Michelle E. Sahm Memorial Award to name a few.

Valerie is known among educators to be a strong advocate and mentoring source for emerging artists and ensembles around the country. In 2011, she created a summer mentorship program in New York City for highly advanced collegiate and post-graduate musicians, called Imani Winds Chamber Music Festival. Now in it’s 9th season, the festival has welcomed musicians from over 100 institutions both national and abroad. Her works are published by Theodore Presser, International Opus, and her own company, V Coleman Music. Her music can be heard on labels: Cedille Records, BMG France, Sony Classics, Eone (formerly Koch International Classics) and Naxos.”

Juilliard’s Music Advancement Program (MAP) Welcomes Flutist and Composer Valerie Coleman for Residency in 2021-22

Wednesday, August 18, 2021NEW YORK–– Flutist and composer Valerie Coleman will join Juilliard’s Music Advancement Program (MAP) for a residency in 2021-22 through American Composers Forum (ACF) and its BandQuest commission and residency program. During the 2021-22 school year, Coleman will work with the young musicians of MAP in a residency that will include workshops, conversations, performances, chamber coachings, and full ensemble collaboration. A culminating piece, co-created by Coleman with the MAP students, will receive its world premiere in New York City in the spring.

“I am honored and thrilled to be working alongside Juilliard and American Composers Forum in this exciting venture,” Coleman said. “The opportunities and resources provided to young musicians by these organizations have been invaluable to ensure that the vibrancy and enthusiasm for music playing within students remain strong throughout their young careers.” Coleman, who has served on the MAP faculty, said she looks forward to “reconnecting with the program and spending time with the students during this residency, and to create a work that celebrates and bolsters their artistic potential.”

While Coleman has had a long relationship with MAP, this new collaboration with ACF was the result of conversations about how a composer could be integrated into the preparatory program to foster creativity and deepen students’ learning.

“The Music Advancement Program is excited to participate in American Composers Forum’s BandQuest residency with the amazing Valerie Coleman,” said Weston Sprott, dean of Juilliard’s Preparatory Division. “Valerie’s return to Juilliard—to create a work for our wind ensemble, teach our students in composition and chamber music, and inspire our community in numerous other ways—promises to be a highlight of the school year.”

ACF president and CEO Vanessa Rose said that this “expansion of BandQuest enables ACF to work with several elements of a program like MAP that is dedicated to transformative work: bringing together students studying different areas of music in the spirit of creation, providing an opportunity to pilot a composer-in-residence, and inspiring the student’s ecosystem around them to work and play with a living composer. We are excited to follow the tremendous impact making music with Valerie will have on the students, and their community.”

For more than 20 years, ACF’s BandQuest program has enabled established music creators to collaborate with school band programs on creating a new musical work. The resulting pieces of music are published by ACF and distributed exclusively by Hal Leonard Corporation.

About Valerie Coleman

Valerie Coleman is an internationally acclaimed, Grammy -nominated flutist and composer. She is an alumna of Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center’s Bowers Fellowship program, laureate of Concert Artists Guild competition, American Public Radio’s 2020 classical woman of the year, and the creator of the ensemble Imani Winds. Listed as one of the top 35 women composers in the Washington Post, Coleman was the first African-American woman to be commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra and was a composer in residence for Orchestra of St. Luke’s five-borough tour. In addition to having had performances of her music by the likes of the St. Louis Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Minnesota Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, New World Symphony, Louisville Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony, and Utah Symphony, she has received the Herb Alpert Awards Ragdale Prize, Van Lier Fellowship, MAP Fund, and ASCAP Honors Award, among others. Her work UMOJA was listed by Chamber Music America as one of the top 101 great American ensemble works. In addition to multiple commissions from Carnegie Hall, she’s had commissions from the Philadelphia Orchestra, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, American Composers Orchestra, Collegiate Band Directors National Association, Chamber Music Northwest, National Flute Association, and Hartford Symphony Orchestra. Her work as a recording artist features an extensive discography with Imani Winds and appearances on albums by Wayne Shorter Quartet, Steve Coleman and the Council of Balance, Chick Corea, the Brubeck Brothers, Edward Simon, and Mohammed Fairouz on the labels Naxos, Sony Classical, Deutsche Grammophon, eOne and Cedille Records. Her compositions and performances are regularly on the air domestically at Sirius XM, NPR, WNYC, WQXR, and Minnesota Public Radio and abroad including through RadioFrance, Australian Broadcast Company, and Radio NZ. Coleman is a highly sought-after recitalist and multidisciplinary clinician with a reputation of transformative skill. She’s had master classes and performances at institutions including Juilliard, Eastman School of Music, Curtis Institute, Manhattan School of Music, Yale University, Carnegie Mellon, Oberlin College, University of Chicago, and Interlochen Arts Academy. Valerie Coleman is a Yamaha Flute Artist. vcolemanmusic.com

About Juilliard’s Music Advancement Program (MAP)

Juilliard’s Music Advancement Program (MAP) is a Saturday program for intermediate and advanced music students from New York City’s five boroughs and the tristate area who demonstrate a commitment to artistic excellence. The program actively seeks students from diverse backgrounds underrepresented in the classical music field and is committed to enrolling the most talented and deserving students regardless of their financial background. Through a rigorous curriculum, performance opportunities, and guidance from an accomplished faculty, MAP students gain the necessary skills to pursue advanced music studies while developing their talents as artists, leaders, and global citizens. Approximately 70 students are enrolled in MAP, which is led by Artistic Director Anthony McGill.

MAP is generously supported through an endowed gift in memory of Carl K. Heyman.

(ACF) supports and advocates for individuals and groups creating music today by demonstrating the vitality and relevance of their art. We connect artists with collaborators, organizations, audiences, and resources. Through storytelling, publications, recordings, hosted gatherings, and industry leadership, we activate equitable opportunities for artists. We provide direct funding and mentorship to a broad and diverse field of music creators, highlighting those who have been historically excluded from participation.

Founded in 1973 by composers Libby Larsen and Stephen Paulus as the Minnesota Composers Forum, the organization continues to invest in its Minnesota home while connecting artists and advocates across the United States, its territories, and beyond. ACF frames our work with a focus on racial equity and includes within that scope, but not limited to, diverse gender identities, musical approaches and perspectives, religions, ages, (dis)abilities, cultures, backgrounds, sexual orientations, and broad definitions of being “American.”

Visit composersforum.org and composersforum.org/bandquest/ for more information.This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit arts.gov. Additional support is provided by the I.A. O'Shaughnessy Foundation.

VALERIE COLEMAN: “Afro” and “Danza” from Afro-Cuban Concerto for Wind Quintet

Utah Symphony.org

Talk about swimming upstream! After centuries of cultural opposition to women in classical music on both sides of the Atlantic, and at a time when the under-representation of women and Black Americans in classical music professions is in the news, Valerie Coleman has overcome these obstacles to become one of the most acclaimed and widely programmed composers of our times. She was named by the syndicated radio program Performance Today as the 2020 Classical Woman of the Year, and was designated as one of the “Top 35 Female Composers in Classical Music” by influential music critic Anne Midgette. Both as a composer and an articulate voice for change, Valerie Coleman is a major voice for music and for change.

Whether live or on broadcast, Coleman’s compositions are easily recognizable for their inspired style and can be throughout venues, institutions and competitions globally. The Boston Globe described Coleman as a having a “talent for delineating form and emotion with shifts between ingeniously varied instrumental combinations,” and The New York Times observed that her compositions are “skillfully wrought, buoyant music”. With works that range from flute sonatas that recount the stories of trafficked humans during Middle Passage and orchestral and chamber works based on nomadic Roma tribes, to scherzos about moonshine in the Mississippi Delta region and motifs based from Morse Code, her body of works have been highly regarded as a deeply relevant contribution to modern music.

Valerie Coleman

A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Coleman began her music studies at the age of eleven and by the age of fourteen, had written three symphonies and won several local and state performance competitions. She is the founder, creator, and former flutist of the Grammy® nominated Imani Winds, one of the world’s premier chamber music ensembles, and is currently an Assistant Professor of Performance, Chamber Music, and Entrepreneurship at the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami. Through her creations and performances, Valerie has carved a unique path for her artistry, while much of her music is considered to be standard repertoire. She is perhaps best known for UMOJA, a composition that is widely recognized and was listed by Chamber Music America one of the “Top 101 Great American Ensemble Works”. Coleman has received commissions from Carnegie Hall, American Composers Orchestra, The Library of Congress, the Collegiate Band Directors National Association, Chamber Music Northwest, Virginia Tech University, Virginia Commonwealth University, National Flute Association, West Michigan Flute Society, Orchestra 2001, The San Francisco Chamber Orchestra, The Brooklyn Philharmonic, The Flute/Clarinet Duos Consortium, Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Chamber Music Northwest, and the Interlochen Arts Academy to name a few.

Vcoleman: Concerto For Wind Quintet: Afro

V. Coleman: Concerto For Wind Quintet: Afro

Imani Winds:classical Underground

℗ Imani Winds: Classical Underground

Released on: 2005-01-25

Coleman’s Afro-Cuban Concerto interweaves musical sources from Africa, the Americas and the Caribbean to unique and irresistible effect. The Los Angeles Times described the result as an “engaging showpiece, deftly woven polyrhythmic lines — suggesting the pulse of Cuban clave and even James Brown.” The Boston Globe cited Coleman’s “talent for delineating form and emotion with shifts between ingeniously varied instrumental combinations,” and The New York Times hailed her compositions as “skillfully wrought, buoyant music.” Not to be outdone, critic Steve Metcalf of the Hartford Courant called her as “The composer who almost made me forget Mozart”.

Valerie Coleman

Biography

Valerie Coleman (b. 1970, Louisville, Ky.) is an American composer and flautist.

Ms. Coleman began her music studies at the age of eleven, and by the age of fourteen had written three symphonies and won several local and state competitions. She has a double bachelor’s degree in theory/composition and flute performance from Boston University, and a master’s degree in flute performance from the Mannes College of Music. She studied flute with Julius Baker, Alan Weiss, and Mark Sparks; and composition with Martin Amlin and Randall Woolf.

She is not only the founder of Imani Winds, but is a resident composer of the ensemble, giving Imani Winds their signature piece Umoja (which is listed as one of the “Top 101 Great American Works” by Chamber Music America). In addition to her significant contributions to wind quintet literature, Valerie has a works list for various winds, brass, strings and full orchestra.

Her work as a composer has garnered several awards such as the Herb Alpert Awards Ragdale Prize, Van Lier Fellowship, MAPFund, ASCAP Honors Award, Chamber Music America's Classical Commissioning Program, an induction into her high school's hall of fame, and nominations from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and United States Artists.

Ms. Coleman has served on the faculty of The Juilliard School’s Music Advancement Program and Interschool Orchestras of New York. Currently, she is on the advisory panel of the National Flute Association.

Works for Winds

- Arabia (2013)

- Fanfare for Uncommon Times (2021)

- Let Woman Choose Her Sphere (2020)

- Red Clay and Mississippi Delta (2009)

- Roma (2011)

- Tzigane (2011)

- Umoja (2008)

Resources

- The Horizon Leans Forward…, compiled and edited by Erik Kar Jun Leung, GIA Publications, 2021, p. 298.

- Valerie Coleman, Theodore Presser

- Valerie Coleman website

Valerie Coleman, Founder of Imani Winds

American composer and flutist Valerie Coleman was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky. She displayed a strong interest in music as a toddler, picking up sticks in the backyard and pretending they were flutes. She started formal music training in the fourth grade, and by age fourteen she had written three symphonies.

Coleman earned degrees in composition and flute performance from Boston University and graduated with a Masters Degree in flute performance from Mannes College of Music. While she was still a student, Coleman began planning a chamber music ensemble. She chose the name Imani Winds, Imani being the Swahili word for faith. The group focuses on music by underrepresented composers from the non-European side of contemporary music, and their repertoire includes music that is inspired by influences from the music of Africa, Latin America and North America.

In 2019, Coleman composed Umoja, Anthem for Unity for the Philadelphia Orchestra, which was the first work commissioned by the orchestra from a living African-American woman. And Valerie Coleman was named Performance Today's 2020 Classical Woman of the year.

Imani Winds: Portraits of Josephine by Valerie Coleman:

May 1, 2013

Music Interviews

Classical Chamber Music Ensemble Imani Winds

May 23, 2006

Heard on News & Notes

Listen:

AUDIO:

Download

Transcript

Imani Winds.

Ms. VALERIE COLEMAN (Flutist and Composer): I can remember when I was a little kid. I used to be in the youth orchestra, and there were so many African- Americans in the orchestra. But somewhere along the line, when I got to college, I was the only one in the orchestra. So I wondered what in the world happened here?

It came to my mind that role models are needed.

ED GORDON, host:

That's flutist and composer Valerie Coleman. In 1997, while still a student, Coleman decided to start her own chamber music ensemble. The idea was to gather together some of the best African-American woodwind players around. She called the group Imani Winds.

Here, Valerie Coleman tells the story of Imani Winds.

Ms. COLEMAN: I basically called around. I gave them my whole spiel. One of the things that I asked them was who are your role models? When you were growing up, who were your role models? And, were there any African-Americans as your role model? And the answer was basically no from everyone.

Of course, you had Winton Marsalis, but he plays trumpet and we're woodwind instruments. So I said, well, guys, we have a chance to change that. We really have the opportunity to let people know that classical music is an all- inclusive thing, not exclusive.

That's basically how the group came together. We get into a practice room. It was magic from the very beginning, and I said to myself, this is going to be something.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. TORIN SPELLMAN-DIAZ (Oboe Player, Imani Winds): My name is Torin Spellman- Diaz, and I'm playing the oboe.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. MONICA ELLIS (Bassoon Player, Imani Winds): My name is Monica Ellis. I play the bassoon.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. MARIAM ADAM (Clarinet Player, Inami Winds): My name is Mariam Adam. I play clarinet.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. JEFF SCOTT (French Horn Player, Imani Winds): I'm Jeff Scott. I play the French horn.

(Soundbite of music)

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. COLEMAN: Imani Winds is, I believe, is a richer sound because of the personalities in the group. And personalities definitely reflect on the individual instruments.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: We're playing a composition that I wrote. It's actually the first movement of this piece that describes Josephine Baker's life. And this movement in particular gives you the setting of St. Louis during the time of 1920.

So this movement is basically describing all of that, and also showing us Josephine Baker as a little girl, the mischievous little girl who used to steal fruit from the stands just so she could have food to eat.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: I grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. My mom, she says that when she had me in the womb, that she would play Beethoven Sixth Symphony, the Pastorale Symphony to me all the time. And so, that's how it all began.

(Soundbite of laughter)

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: I remember being a baby, being in the backyard, picking up tree limbs and pretending that it was a flute.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: And then when I started to learn music in elementary school, I immediately started to write it down as I learned how to read music.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: By the time I was in high school, as a hobby, I would write whole symphonies and things like that. You know. Things that normal children don't do.

(Soundbite of laughter)

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: You know, I grew up in Muhammad Ali's neighborhood, the west end of Louisville. And that is about as inner-city as any inner-city can get. And my mom, she raised me right, and she worked hard at it. And, you know, my dad died when I was nine years old, so for the most part, when he died, me and my sisters - you know, my mom became a single mom at that point and she picked up the pieces. And somehow, she sent us all to college and just pulled it together and made it possible for us to get our education and what not. And I think that that's what drives me today, because I want to go back, and I want to help my community. I want to help the people in my family, particularly the men in my family.

I would say about 70 percent of them have been incarcerated, or are currently incarcerated. So my family, I always consider, is in a 9-1-1 situation, so that's what drives me. Because I know that I have to really do something about it.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. COLEMAN: What should African-Americans hear when they come to our concerts? What should they listen for? My answer is simple: listen for the soul. Listen for the soul. It's in our roots, it's in our backgrounds. We're bringing our background to the table to interpret all of the music that we play. So listen for it, because you will relate to it.

GORDON: Valerie Coleman of the classical chamber music ensemble Imani Winds. The group's third CD is self-titled.

(Soundbite of music)

GORDON: That's our program for today. Thanks for joining us.

To listen to the show, visit npr.org. NEWS AND NOTES was created by NPR News and the African-American Public Radio Consortium.

Copyright © 2006 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

Imani Winds

https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/valerie-coleman-writing-music-for-people/

Valerie Coleman: Writing Music for People

Earlier this year, New Music USA launched Amplifying Voices, a program promoting marginalized voices in the orchestral field. Following a national call, eight American orchestras are leading consortium commissions for eight different composers. The seven composers selected thus far are Tania León (the first individual composer NewMusicBox interviewed, in 1999), Tyshawn Sorey (featured in NewMusicBox last year), Jessie Montgomery (featured four years ago), Brian Raphael Nabors, Juan Pablo Contreras, Shelley Washington, and Valerie Coleman (with whom we spoke a decade ago, regarding her maverick wind quintet, Imani Winds).

One of the most exciting aspects of Imani Winds is their commitment to new music from a diverse repertoire of composers, which makes sense given that they were founded by a composer. But what about Valerie Coleman, the composer?

In our first conversation with Valerie, we barely scratched the surface of her compositional activities. Since then, these have become her primary artistic focus. Valerie has recently been chosen to participate in the Metropolitan Opera / Lincoln Center Theater New Works program, a perfect fit for her given her commitment to storytelling through her music, no matter the idiom.

So the launch of Amplifying Voices seemed like a perfect opportunity to reconnect and have a conversation about her own music—her aesthetics, her inspiration, and what she hopes she can communicate to listeners.

“That’s just how I identify and it’s because of what my ancestors have gone through,” she explains. “I feel it necessary to tell their story, but also really just embrace this idea of how to walk in the world and inform people around me. … I recognize that there are stories that are yet untold that if they were told, they would transform all those who would hear them. So it’s my job to create music that allows that transformative power to happen.”

(Transcribed by Julia Lu)

Frank J. Oteri: It’s amazing that we talked to you and the other members of Imani Winds ten years ago. In that conversation, we were mostly focused on all of you as interpreters and as curators of exciting new repertoire for wind quintet. But I really want to talk to you as a composer. I want to get back to how music first hit you.

Valerie Coleman: I cannot say when it actually first hit me. It was just very organic and just a part of my playtime as a child. Any child gravitates towards music. , whether it’s just the visceral idea of touching a keyboard and the sound just plunking out; that is something that we all shared in our young childhood. My mom has run a daycare for over 55 years now. So I grew up in a daycare setting. Even though she was the teacher to all of these kids, I was in that that group. And in our home life, she had certain things that were already out in the living room ready to play. Like these play stations.

We had this old Casio. It wasn’t even a Casio; it was like this kind of organ. I think it might have come from a second hand store. It sounded like a Hammond, but it wasn’t a Hammond. It was just something that was like this cheap knock off. I would plunk on the keys and that’s what me and my sisters would do. We would just sit there maybe for five, ten minutes to just play this instrument. But I found that my playtime on the instrument just became these whole sessions that would last for like two hours. . I must have been seven or eight or so. That sounds about right because I was born in 1970 and cassette players were really starting to become the thing to get kids at the time. It was kind of the Elmo doll of the late ‘70s. It seemed like for two Christmases in a row, we got cassette players. That just opened up a world.

I would sit there and play down a melody and record it. Then play it back and try to play another melody or sing on top of that. And so it was kind of this looping back and forth between two cassette players. It started off with just three or four layers. But then it started to get like 10 and 12 layers of loops. For those of you out there who know about cassette players, you know that the sound warps with each playback and record. I thought it was the greatest thing. It was an invention to me to be able to hear back like 10 to 12 layers, but the warped sounds—I didn’t pay any focus to it. Anybody walking by would say it’s a horror show.

But I think that that was a taste of symphonic writing. That that was on the table for me, I didn’t realize at the time. As a matter of fact, I’m just realizing it now because developing your inner ear to write symphonic works means that you have to hear contrapuntal lines and a multitude of them and see how they interlock and all the colors that come from that. At the time, I didn’t have all the colors I wanted per se, but it did help me to develop an inner ear for contrapuntal lines. When I started to play the flute—that really started to inform how I wrote. Because after a while, when you’re starting to write for yourself and you know what you want to hear, and you know what you want to play, and you know what sits well on the instrument, those things start to really impact. And when you start to work with an ensemble that you perform with, and you begin to know the dynamics of the group and the personalities, and the tendencies, and all of those things, and as you’re playing along with them you notice there are certain moments where the energy can spike within a phrase. You learn both orchestration and also how to write in a way that allows for a musician to buy into your musical idea and make it their own.

FJO: The fact that you play an instrument that is contingent upon breath gives you an innate sense of phrasing perhaps and maybe the music breathes in a kind of a larger arc, probably subconsciously, because that’s how you physically make sounds. So when you abstractly create for other people, that’s part of it.

VC: Absolutely. And I would even go as far as saying that there are times where that ability to breathe also allows some perception into dynamic contrasts and making note of that. But there are always those times where you’re writing for a wind group, and if you step away from your instrument within the writing process, sometimes you can lose that perspective. There’s many times where I’ve written for Monica Ellis. the bassoonist of the Imani Winds. She’s that powerhouse that will spoil you as you write for her. Because she can play anything.

Because of that, she has been my muse for many, many years. And I would write these long phrases, and yeah, she would have places to breathe, but she didn’t have the chop breaks. Meaning the time that she could get the bassoon off the face., and rest the chops. So there were times where she was just like, “Valerie, you gotta give a sister a break sometime in the music. You know, look at this. I get four pages, and I don’t have a rest.” And I say to her, “Monica, it’s because you sound so good.” But yeah, those things do inform for sure. I love to create lines that do breathe and feel good to the soul.

I have to admit to you, I’m not somebody who writes based on the intellectual side of composition, but rather on the side of addressing what it is within all of us. The shared qualities of human behavior, what feeds the soul, what identifies the issues or all the complexities within ourselves as human beings. That is mainly my focus. And so breathing goes right into that. Breathing, breath of life, unity, all of those things.

FJO: I’m wondering when that translated into you seeing and hearing other musicians perform and saying, “Hmm, I want to do that. I want to write for them.” Or “I want to play music with them.” Or simply “I want to do that.” Who did you hear? When did that happen? When did this become a social thing rather than an individual thing you did by yourself?

VC: There’s many layers to this because it’s all about the amount of exposure that a student gets. I was raised in the west end of Louisville, Kentucky not far away from where Breonna Taylor was killed. And it’s also not far away from where Muhammad Ali lived. And so my interactions with music were based on what I would do with my sisters. We would sing three-part harmony as kids. And that was my social outlet. And my exposure to classical music was through the radio, WUOL-FM; that’s the University of Louisville’s classical radio station.

I would sit in the backyard, and just listen to Dvořák and Copland, all the hits, and watch the sun go down. That was my exposure to vicariously enjoying a communal classical music. I couldn’t see it, but I could imagine it. I could hear it. It wasn’t really until I got into public school, in the fourth grade, when the band director came to our classroom, and handed out permission slips and said, “Who wants to play in the band?” I got that permission slip eagerly signed, and brought it back in.

I can’t even remember the number of flutists. It must have been four or five flutists. We were all sitting there trying to make a sound out of our head joints. Even at that level of being a novice, the idea of all of us just sitting there, trying to attain the same goal of making a sound out of our instruments was the start of something big for me. I’m in love with the idea of collaborating, and making music within a chamber ensemble. And so band, orchestra, Louisville Youth Orchestra, middle school band, high school band, all of those things, that was my experience. And it was because of music being in the public schools. But before that, it was really just me and my sisters. And we made our music together in our own way.

FJO: Making music with other people is this very, very social act.

VC: Absolutely.

FJO: But composing music in some ways is very anti-social. Right? You’re by yourself, you’re writing this thing down, and ideally you want to turn this anti-social thing into something social. One of the problems is that sometimes it doesn’t translate that way. So I’m curious about the composing bug. You were writing things down somehow, but I imagine when you first started writing things down, you had no idea how music notation worked. So you came up with things that would help you remember to recreate it. So I’m wondering how that became part of your process of making music.

VC: I think after a while, after doing these warped multi-tracks, the idea of writing came to me, although I had no idea about Mozart and Beethoven, the composers that young children learn about early on as being composers. That notion of actually notating something, I felt at the time was uniquely my own. I didn’t know the word composer. I didn’t identify with that, but it just wasn’t there. All I knew was that I had to keep and document what I was doing beyond the tape recorder. So I just basically did what I had to do. My notation was circles, and squares, and triangles. Any kind of crude hieroglyphics that I could make; that’s what I did. When I went back to it, it wasn’t very organized at all. It was just basically a sketch on a paper, much like a stick figure that a six-year-old would draw.

FJO: We’ve been talking about your hearing classical music on the radio. Hearing Dvořák. Hearing Copland. And then learning about Mozart and Beethoven and all these people. What about other kinds of music growing up? You were doing three-part harmony; what were those three-part harmony things?

VC: Oh, come on now. We’re talking about Emotions and the Bar-Kays. Earth, Wind & Fire. Regular pop culture. Everyday life. DeBarge, all of that stuff. The Jackson 5. We were all informed by American Bandstand. We were all informed by Soul Train and all of those shows that would come on Saturday midday; we would do the dance moves and all of that stuff. But somehow or another, there was really no distinction between that particular genre and that way of life with creating music on the keyboard. There was no distinction whatsoever. So it all blended in together. And as a matter of fact, when I started band in elementary school, there was a large number of people of African descent, Black folk, kids like me that were in band.

And what we would do in middle school as we were sitting there and we were going through ear training. I had a great ear training teacher in middle school. Great band teacher. Because that’s what he would focus on. He would focus on us identifying intervals and where the notes are on the scale. During that time, me and my friends would just sit and write down each song that we would hear on the radio. So if it was “Let’s Groove Tonight,” we would write it down. We didn’t have the rhythmic notation. We just knew the notes.

When our teacher wasn’t looking, we were playing those songs on our instruments. We were just kind of sneaking around with that. That’s how students informed themselves. When you’re raising a child, and I say this because I’m a mom, they don’t have a user’s manual. But in their own way, they are their own user’s manual. They kind of guide you in where to guide them. And I think that that’s the same thing with students who are learning music. They kind of guide you a little bit.

FJO: So you heard these songs, and you did these things in band, but then there were these names that were given to you from on high as it were. Copland was still alive at that point, but was still very far removed from the life of a little girl in Louisville, Kentucky. So how did you come to feel like this was for you and that you could be part of this?

VC: I never doubted it for a moment, and I never even posed that question. It was just there. What I can identify is that moment where things just started to lock into place for me.

But it wasn’t necessarily that I would fit into a demographic of being a composer. I already knew that subconsciously. There was also a time where I realized that I couldn’t possibly be a composer. And that was when I was in college. Up until that point, up until the point of my graduating from high school, I always just knew that composing and arranging was what I did. My summer projects were when I was a teen sitting in the backyard, in that same backyard that I listened to symphonies and wrote my own. They weren’t very good, but it didn’t stop me. And it took me the summer to do that and it helped me to train my inner ear.

But when I got into college, that’s when I noticed the demographic, because at the time I was made to feel like I did not belong. I started to recognize, whoa, maybe composers are supposed to be White male and not Black female. And so I went through school thinking that that very thing. I stopped calling myself a composer, but I kept writing. It was almost as if the idea of composing, or being a composer was this mantle that I was undeserving of. Or that I had no right to claim. And it wasn’t until when I started Imani Winds and started writing for the group—even years after that, it wasn’t until I got a review where the critic had called me a composer. I started to think, “Whoa. Maybe I am a composer. Maybe this is what I’ve been doing this whole time and now it’s just up to me to embrace that title.”

FJO: I’m wondering about the first time when something you wrote was played by someone else.

VC: Well, all through elementary school. I arranged Lisa Lisa’s “Lost in Emotion” for the pep band in high school. That moment of truth for me, though, happened when I was at Tanglewood. Boston University, Tanglewood Institute It was my very summer outside of the state of Kentucky, and I brought with me a flute trio.

It was a masterclass that I was there for that had Leone Buyse and Doriot Dwyer. They were the principals of the BSO at the time. And I remember bringing that flute trio up on the stage, and I brought my friends with me, and Doriot Dwyer, she didn’t comment on whether it was good or bad, she just said, ”Okay, let’s work on this for a little bit.” And the whole session for that day was working on that trio. And that moment I think was the life changer for me. Because in her taking the time to identify and go through the music as if it were not a student composition, but an actual piece of music, to dissect and talk about interpretation and talk about balance and blend and intonation, treat it like any other piece of music that we’ve learned.

That was such a significant validation to me that allowed me to move forward. And it also was the thing that made me to apply to Boston University, too. So it all comes together in that way. But yeah, that’s educators. It’s so important that they encourage and not discourage in what they do. And sometimes we have to be really, really careful. There’s a difference between tough love and destruction. It’s a fine line sometimes.

FJO: I didn’t know that story about Doriot Anthony Dwyer who’s a pioneer role model. She was the first female flutist in an American symphony orchestra, so to have the validation from her was a huge thing.

VC: I knew that I was lucky to have studied with her for a summer. Thank you for saying that.

FJO: That’s a story I didn’t know. I was expecting a story that happened later on. You were writing music and playing it, and then all of a sudden, there started to be pieces that you wrote that wound up being played by other people. The pieces I’m thinking of immediately are Danza de la Mariposa and Wish Sonatine. These pieces have now been played by so many different people. And I wonder in my mind how Valerie the flutist first felt hearing all these other flutists play it. It’s kind of like motherhood in a way. Your kid goes out and you’re worried when they’re going to come home. But you have to let it go. Just like when you write a piece. It has to have a life of its own.

VC: You have to let it go. That’s right. And but you know what, Frank. Let me tell you, being a mom of a six-year-old right now, I think I’m gonna have a hard time practicing what I preach.

I’ve always looked at musical compositions as my children. We all do as creators. Nothing gives us more joy than to see our compositions go out into the world and make their own mark. They’re a piece of paper. They’re music. They’re gestures. They’re sounds. But yet they function as people out in the world—how they make an impact, how they encourage or discourage people, how they have the potential of sending messages. It’s all there. And so for me once a piece is written, like a Danza de la Mariposa or Wish Sonatine, and it goes out into the world, and somebody picks it up and makes it their own—that is the highest compliment that I could ever feel towards that piece. It’s the same thing with Imani Winds, too. I retired from the group in 2018, and to me, as I’m leaving, I’m thinking, “I hope this group lasts the test of time.”

Long after we all get older, maybe there’s a new group of Imanis that come in. But I’m not looking at it as a legacy, but rather as the impact that it has, and that it is its own living entity. So that just gives me a sense of pride. I don’t know if it’s so much letting go as much as it is just loving it enough to set it off into the world and giving it room to grow and find its own path.

FJO: That’s very beautifully said, and you know, we’ll talk in ten years when your daughter’s 16.

VC: Yeah, yeah. No. She’s staying home. Ain’t going nowhere. Not dating.

FJO: Well hopefully ten years from now, we can out outside again. Right?

VC: Oh, gosh.

FJO: We’re not going there just yet; let’s talk a bit more about wind quintets. We talked about this ten years ago. The wind quintet has five very different sonorities, it’s very different from the string quartet say, or the sax quartet, or even the brass quintet. It’s sort of an orchestra in miniature.

VC: It’s miraculous. For those of you who want to write for wind quintet, please do it, and find out what the miracle is all about. The miracle is in the fact that every two instruments that you put together blend in a beautiful, distinct way. And the palette that comes from that allows a person to transform what is just woodwinds and French horn into a jazz band, an orchestra, a full marching band, a full rock band, if you want. The colors are endless. And what even makes it even more complex and beautiful is the fact that everybody produces their own sound in a different way.

All the articulations happen differently. And so it is not only the skill of the musician to be able to get a flute articulation to sound like the attack of a bassoon, but it’s also in the skill of a composer to know when to challenge that moment as well. I’m in love with writing for wind quintet because I’ve been spoiled by the very best, I have to say. When Jeff Scott and Monica Ellis come together, they can lay down the groove like the top rhythm section in the world. So I know that I can write for drums with just the two of them involved. I guess for those who are creating for wind quintet out there, I would say just try to keep some common sense going about breathing. Don’t do what I do and write without rests.

FJO: Playing in a wind quintet and writing for them, and working with all these different composers who wrote for that particular ensemble was a laboratory for you, I would dare to say, that has given you plenipotentiary now to be writing for orchestra.

VC: Absolutely. I completely agree. I do find that there are times where I have to resist in my writings for orchestra to be woodwind heavy. Because that’s my natural go-to. The idea of all the different blends and challenges of the different voices coming together, even contrapuntally does inform how I write for the orchestra as a whole. I’m still learning.

FJO: So, let’s talk about that very first writing for orchestra. You wrote this piece that sort of became a signature piece for Imani, Umoja, which means unity. And it began as a choral piece, then it became a wind quintet, then later on it became a wind band piece, and then it became a larger orchestra piece.

VC: It started off as a work for women’s choir. I had started this pan-African cultural organization when I was a student at the New School. It was the classical department and the jazz department. And we were just trying to figure out ways of making an impact in our larger New York community. And sothe holidays rolled around, and Kwanzaa-like songs came into my head, and Umoja was one of them. It started off with the women’s choir and if you can imagine us swaying back and forth, inspired by Sweet Honey in the Rock, that’s how Umoja came about. And then right after that, it wasn’t shortly after the Imani Winds was formed, one of our first gigs was for a wedding.

And it was for this actor who was very much into the Black actors’ community. He wanted to have all these different, various African culture identity themes to it. And so he asked for us to play that kind of music. So I was just like, “Okay, let’s just go ahead, and I’ll just go ahead and make Umoja an arrangement for that.” And so we learned it. I remember initially the reaction of the group was that it was really simplistic, but then when we played it in the wedding, people stopped their conversations to listen to the tune. I remember Monica saying at the end of the wedding, “Valerie, that piece works.”

Imani Winds performs Valerie Coleman's "Umoja"

Imani Winds plays Coleman, Rimsky-Korsakov, Piazzolla and more!

https://thefluteview.com/2021/03/valerie-coleman-page-artist-interview/

Valerie Coleman Page Artist Interview

Valerie Coleman is a GRAMMY Nominated flutist and composer and Performance Today’s “2020 Classical Woman of the Year”. Her visionary mind is responsible for the creation of the iconic ensemble Imani Winds, its chamber music festival, and a wealth of repertoire that has become a cornerstone legacy within American chamber music. A native of Louisville, Valerie is an alumna of Concert Artists Guild, CMS Lincoln Center Two fellowship, is listed as “one of the Top 35 Women Composers” by the Washington Post and is the first African-American woman to be commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Metropolitan Opera.

Can you give us 5 career highlights?

To be onstage performing with Jazz artist Wayne Shorter was one of the

most amazing experiences in my life, as I had the opportunity to witness

a giant performing his iconic works; it forever changed the way I

performed. Another big career highlight for me was writing for the

National Flute Association's High School Young Artist Competition, which

resulted in the creation of the work, Fanmi Imèn. Writing this piece

gave the opportunity to send a message of unity as inspired by the words

of Maya Angelou in her poem, Human Family. Having historic firsts are

highlights that I could not have imagined, but I was recently the

first African-American woman to be commissioned by the Philadelphia

Orchestra. With my composer colleagues Joel Thompson and Jessie

Montgomery, we three are the first African-American composers to be

commissioned by the Metropolitan Orchestra.

How about 3 pivotal moments that were essential to creating the artist that you've become?

The first time I picked up the flute in 4th grade, the first time my music was recognized as a valid, viable work by Doriot Dwyer at Boston University Tanglewood Institute, and the creation of Imani Winds.

What do you like best about performing?

I love being the vehicle to which a story can be told and shared, and breathing through the music in a way that it becomes alive. Performing allows music to become our companion.

What do you like best about composing?

The thing I like best is the birth of a new work, from the moment within the process that a certainty of direction manifests and the work begins to form personality and write itself, to its launch into the world.

CD releases?

No releases this year, but I am so very honored that some of the leading flutists and clarinetist in our field today have programmed my music on their albums.

Giantess, Jennie Oh Brown. Cedille Records,

2019https://www.allmusic.com/album/giantess-mw0003320044

Clarinet Quintets for Our Time,David Shifrin with Harlem String Quartet.

Delos Label,

Imani Wind Quintet playing at Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium

As a rule, we don’t expect revolutionary music trends from classical chamber ensembles. But if ears are open to the Imani Wind Quintet, even the seasoned chamber listener will be surprised by the novel delights in sound, repertory and musical associations. It’s safe to say that there’s nobody else like them.

The 16-year-old New York City-based ensemble plays Sunday at Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium with guest pianist Anne-Marie McDermott. The African American quintet consists of flautist Valerie Coleman, oboist Toyin Spellman-Diaz, clarinetist Mariam Adam, French-horn player Jeff Scott and bassoonist Monica Ellis.

“This instrumentation,” Scott says from his home in the Bronx, “has been around since the 1700s. Anton Reicha, a French composer who was a contemporary of Beethoven, is considered the father of the wind quintet form. It was popular all through the Romantic period. Composers like Giuseppi Cambini wrote serviceable music, but Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Ravel and Strauss all wrote for the form.”

“Then there was nothing for almost a century,” Scott continues. “It fell by the wayside in the modern era. The New York Wind Quintet and the Philadelphia Wind Quintet commissioned a few contemporary composers like Hindemith and Samuel Barber to write, but those pieces just never caught on, for some reason. There was nothing new for us to draw upon, so we commissioned people to write for us. We would also arrange pieces within the group. Valerie and I contributed our own compositions.”

“My first arrangement,” Scott says, “was for a William Grant Still composition, ‘Inanga.’ Looking back, I don’t think I had the requisite feel. Valerie constantly tells me I should revisit the piece and rework it.”

Would Imani Winds consider going to some of the local jazz composers who know how to write for the wind idiom, like pianist Billy Childs and flautist James Newton?

Scott chuckles at the recognition, “We know them! Billy will probably give us a piece in the next three or four years. We have a lot of music to draw from, but there are only so many concerts on our schedule each year. It’s a source of frustration.”

Scott follows a certain standard when looking for compositions. “It’s got to feel good,” he stresses, “sound good, and it has to have meaning.”

Composer and pianist Chick Corea believes that every band has to have a mission — a reason for being, and a task that no other band can carry out. Asked about Imani’s mission, Scott says, “It’s twofold. Or threefold. Originally, we were an ensemble that champions the lesser-known composers and literature for our instrumentation. We also wanted to be role models for kids who looked like us and were interested in playing classical music.”

“Over the last seven or eight years,” he continues, “we’ve tried to make this group more meaningful than just our concert schedule and recordings. We want to leave a legacy of original music for the next generation of musicians. We’ve commissioned music by some of the finest composers from many genres: symphony, jazz, African and Latin. It’s important to us that we leave something behind.”

KIRK SILSBEE writes about jazz and culture for Marquee.

What: Imani Wind Quintet with Anne-Marie McDermott

Where: Beckman Auditorium, Caltech, 332 S. Michigan Ave.