SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BAIKIDA CARROLL

(September 3-9)

BILLY DRUMMOND

(September 10-16)

BOBBY MCFERRIN

(September 17-23)

ALBERT KING

(September 24-30)

CLORA BRYANT

(October 1-7)

DEAN DIXON

(October 8-14)

DOROTHY DONEGAN

(October 15-21)

BOBBY BLUE BLAND

(October 22-28)

CARLOS SIMON

(October 29-November 4)

VALERIE CAPERS

(November 5-11)

CHARLES MCPHERSON

(November 12-18)

PAUL ROBESON

(November 19-25)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/paul-robeson-mn0000028464/biography

Paul Robeson

(1898-1976)

Biography by Ronnie D. Lankford, Jr.

Paul Robeson excelled as an athlete, actor, singer, and activist, making him a contemporary renaissance man. His early accomplishments as a professional football player, Columbia law school graduate, and an actor on Broadway in the 1920s seemed but a prologue to even greater achievements to come. Involvement with the political left in the 1940s, however, led to a confrontation with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in the late '40s. He was blacklisted, his passport was revoked, and his career came to a halt.

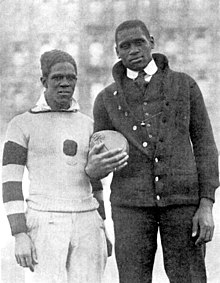

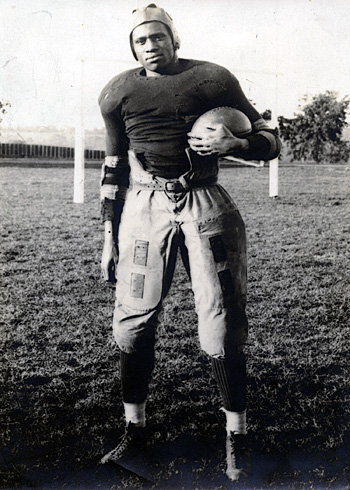

Robeson was born on April 9, 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey. His father was a runaway slave who became a Methodist minister, and his mother died from a stove-fire accident when he was six. At the age of 17, Robeson became the third Black student to enter Rutgers College (now University) where he made All-American in football and lettered in four varsity sports. Many of these achievements were nonetheless overshadowed by racism: his teammates often harassed him, and he was barred from the school's glee club. After Rutgers, he played professional football on the weekends to support his studies in law at Columbia University. Following graduation, he obtained work at a New York law firm, but quit when a stenographer refused to copy a memo, telling him, "I never take diction from a n*****."

Since Robeson already had experience in theater, his wife, Eslanda Cardozo Goode, encouraged him to pursue acting. In 1922 he appeared on Broadway, playing Jim in Jim H. Harris' Taboo, and then traveled to England where he revised the role. He joined Eugene O'Neill's Greenwich Village Provincetown Players on his return and appeared in All God's Chillun Got Wings. He also won critical acclaim for his starring role in The Emperor Jones in 1925. Robeson toured England and the United States over the next three years, singing Black spirituals and creating a sensation with his role as Joe in Showboat.

For the next ten years, Robeson lived abroad, avoiding the simmering racial conflicts in the United States. He appeared in Othello and The Hairy Ape, toured Europe, and even visited Russia, where he was well-received. In the late 1930s he also reexamined his passive stance on political issues. After singing for Franco's opponents in Spain, he embraced communism and decided to return to America to fight racism. Stateside, Robeson busied himself with protesting lynching, picketing the White House, and refusing to perform for segregated audiences.

Even with his awakened interest in politics, Robeson maintained a busy acting and singing schedule in the early '40s, first appearing in a radio performance of Ballad for Americans and later in the first American version of Othello to include a Black actor in the lead role. His controversial political positions, including a suggestion that Blacks should refuse to fight if the United States went to war with Russia, soon caused repercussions. When appearing before HUAC, the Committee asked him why he didn't relocate to Russia. He replied: "Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay right here and have a part of it just like you."

The U.S. State Department revoked Robeson's passport in 1950, which meant he would be forced to remain in the United States, where he was blacklisted. When he completed his autobiography in 1958, even The New York Times and The New York Herald-Tribune chose not to review it. After his passport was reinstated in 1958, he traveled once again to Britain and Russia, where he remained popular. Following stage work in Europe and Australia, Robeson returned to the United States in 1963 due to declining health.

On April 15, 1973, admirers gathered at New York's Carnegie Hall to celebrate his 75th birthday. Robeson was admitted to Presbyterian University Hospital in Philadelphia on December 28, 1975 following a massive stroke. He died on January 23, 1976.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Robeson

Paul Robeson

When Paul Robeson graduated from Rutgers in 1919, he thought he’d become a lawyer. But soon after he earned a degree from Columbia and landed a job with a law firm, a secretary who was white refused to take dictation from him because he was black. Robeson quit – not just the job, but the profession, too.

“He was hoping to be accepted on the basis of merit, merit that transcends race,” explains Wayne Glasker, an associate professor specializing in African-American and 20th-century U.S. history at Rutgers University-Camden. “But he was judged on the basis of color.”

Fortunately, there was a plan B – one formulated, in part, by Robeson’s newlywed, Eslanda Goode, who had encouraged him to pursue acting and singing. It didn’t hurt that they were participants in the Harlem Renaissance, a social and cultural movement of black artists and intellectuals.

Robeson was famous for his film and stage appearance as Joe in Showboat (photo: John D. Kisch/Getty Images)

Robeson was a shining example. The singer and scholar, having already appeared in off-Broadway productions, drew the attention of the Provincetown Players, including cofounder Eugene O’Neill. In 1924, he recruited Robeson to star in two of his plays, All God’s Chillun Got Wings and The Emperor Jones. Robeson hadn’t formally trained as an actor, but he earned favorable reviews and an acting career was born.

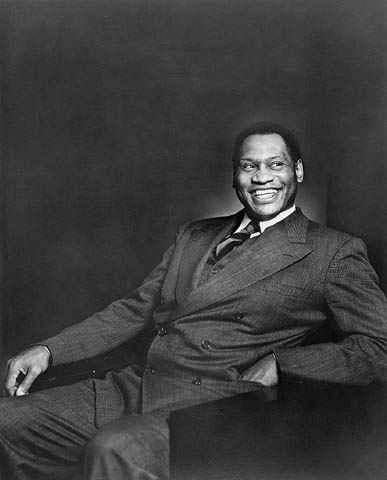

Although he lacked technique, “he had a commanding presence; he was very charismatic,” Glasker notes. Andrew Flack, a playwright who cocreated I Go On Singing, a multimedia musical account of Robeson’s life, adds: “He was an Adonis, a David, and he had that voice.”

It was the melodious bass-baritone Robeson had used in his pastor father’s churches, in vocal performances at Rutgers and at paying gigs. His singing was inspired by a wellspring of Negro spirituals that he had heard throughout his childhood. But not until he teamed up with Lawrence Brown, an accomplished pianist-arranger, did he consider concentrating solely on those songs. In April 1925, in a Greenwich Village theater in New York City overflowing with a mixed-race audience, the duo did just that, prompting 16 calls for encores and raves from critics, one calling Robeson “the new American Caruso.”

Over the next three decades, Robeson balanced acting with singing—selling out concerts, producing albums and traveling internationally. His exposure to foreign cultures prompted Robeson to add popular folk songs from around the world to his own repertoire. And there was one stage production in particular that married his acting and singing talents memorably.

Show Boat, a wildly popular 1930s musical, featured Robeson in the role of Joe, an amiable stevedore. The part was small, but it gave him the chance to sing “Ol’ Man River,” which was later immortalized on film. “There are people who know almost nothing about Paul Robeson but remember him as Joe singing ‘Ol’ Man River,’” says Glasker.

The role, however, perpetuated a stereotype Robeson would come to despise. The theatrical world “never understood how to use him because they didn’t have the material for him,” Flack says. “He was way ahead of his time. They couldn’t imagine a story about an intelligent, complicated black man.”

The one exception was Othello, Shakespeare’s tale of a Moorish army general who murders his white wife after she’s falsely accused of cheating on him. While that storyline was, as Glasker says, taboo at the time, Robeson eagerly dove into the role thrice during his career – first in 1930, as an actor still in training, and second in a 1943-44 Broadway production, which ran for 296 performances and established him as the era’s definitive Othello.

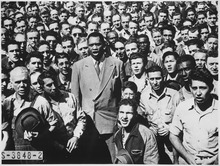

Robeson, at that time, “was one of the best-known humans in the world,” Flack says. “Here was an educated, erudite, sophisticated man. A world traveler, a jet-setter. He knew everybody; everybody knew him. He was truly a modern American man.”

But he was also headed for trouble. By the time World War II began, Robeson’s left-leaning political views and support of Joseph Stalin had drawn the attention of the federal government, which, in 1950, revoked his passport – in effect putting his performing career on hold. Nine years later, after his passport had been reinstated, Robeson took a third stab at Othello, in a London production. But his career, aside from occasional concerts, was all but over. A year later, his health in decline, he ceased performing altogether.

He had, however, opened the door for a new generation of actors and singers – among them Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte – who took on roles and performed songs rooted in the black experience.

Salamishah Tillet, professor of African-American and African studies and associate director of the Clement A. Price Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience at Rutgers University–Newark, says of that legacy: “He’s an exceptional figure because he’s proof of this idea of trying to use one’s talents and genius to create a space for others and to create a freedom trail for others.”

Rutgers is honoring Paul Robeson’s legacy as a scholar, athlete, actor, singer and global activist in a yearlong celebration to mark the 100th anniversary of his graduation. Read more from our ongoing series on Robeson's life and learn more about the celebration by visiting robeson100.rutgers.edu or by following #Robeson100 on social media.

He was the man the US government tried to erase from history. From the 1920s through the early 1960s legendary bass-baritone Paul Robeson was a musical giant on the world stage but from the late 1940s he was almost unknown within his own country. Part folk hero, part star of stage and screen, Big Paul became famous at a time when segregation was legal in the United States and black people couldn't get a meal in a New York cafe, let alone walk safely in the south, where lynching was not a crime.

Born in 1898, Robeson was a 6'3" black man in a world where most people were 5'4" and most white Americans were afraid of blacks. Despite the everyday racism of the society he lived in, he was renowned for his charismatic warmth, as well as the rare beauty of his voice. It was a voice that people could feel resonating inside them and the intensely personal connection that deep sound made with an audience allowed Robeson to cross racial boundaries and be both loved and respected as a performer.

He used his music to bring Negro spirituals to public attention and through them the traditional folk culture of his people. Big Paul’s father was an escaped slave who put himself through university and became a minister. By taking the spirituals to the concert stages of the world Big Paul was signalling that they were of equal value to any other musical form.

There's no such thing as a backward human being, there is only a society which says they are backward.

As well as advancing the cause of black Americans, he used his music to share the cultures of other countries and to benefit the labour and social movements of his time. A linguist, he sang songs promoting world peace and human rights in 25 languages, including Russian, Chinese and several African languages. They were often traditional spirituals or folk songs telling of struggle, resilience and survival.

More than just a singer, Robeson was also a champion athlete, an actor, and graduated in law from Columbia University. He was also a public champion of the socialist experiment in the Soviet Union, a country that created hope among black people around the world when its constitution outlawed racism. During the 1920s and '30s Big Paul performed in the Soviet Union a number of times and he and his wife and then manager, Essie, sent their son Paul Jr. to boarding school in the Soviet Union so that he could experience a place where people did not respond to him first on the basis of his colour. Paul Jr. attended the same school as Stalin’s son and he says the experiment worked. Attending that school taught him for the first time that all white people were not racist.

In 1939 Big Paul and Essie returned to America after a dozen years living in London, associating with socialist intellectuals like George Bernard Shaw and HG Wells, while Robeson performed across Europe, including a record-breaking two year run in London of the musical Show Boat. But he had a tense marriage, and had continual relationships with other women.

From their return to the United States in 1939 until the late 1940s, Americans loved Robeson. The Soviet Union was their ally and friend during WW2 and due to his spectacularly successful live performances of patriotic hit Ballad for Americans, Big Paul was regarded by all but the FBI as one of the country's leading patriots.

Major concert halls around the country were packed for his concerts and he was earning immense amounts of money from performances and recording contracts. But it didn’t last. The political wind was shifting with the beginnings of the Cold War, and Robeson was unwilling to moderate his public statements to suit the new climate. He refused to shut up or be careful.

Along with the huge concerts, he continued to make speeches demanding justice for people of colour, including American and Caribbean blacks, as well as the right to independence of all colonised people around the world. He and Essie were friends with Nehru and with the emerging black African leaders of the independence struggles against Britain. It was his unflagging support for the Soviet Union throughout the late 1940s and the 1950s though, when America plunged into ‘reds under the bed’ hysteria, that made him an enemy of the state.

From 1941 Robeson was under surveillance by the FBI and as the years passed, interference in his life intensified. The re-enactment we hear in the Into the Music documentary of his appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956 is stirring stuff. Big Paul plays himself. The official recordings of those who testified against Robeson still exist but like almost all US news and radio recordings of him, the recording of his appearance before HUAC was destroyed. Only the transcript remains.

After a speech Robeson made in 1949 at a Paris peace conference was misreported in the US press, more than 80 concerts were cancelled on him and it became almost impossible to buy his records. He had reportedly said the black people of America, a country built on slavery where blacks were discriminated against, would not fight in any war against the Soviet Union; a place he believed was without racism. Robeson never said those words in Paris but there was a kernel of truth in the report and when challenged before repeated inquiries, he refused to deny his friendship with the Soviet Union.

Big Paul was branded a traitor. There was a concerted attempt by Americans as a whole to erase this enormous figure from the public record. He was no longer included in the roll of honour of ‘All-American’ footballers and his Othello was removed from the record books as the longest running Shakespearean play on Broadway. The government and those who supported it—or who feared during the McCarthy years to cross it—attempted to make Big Paul voiceless.

They largely succeeded. Recording studios and concert halls were closed to him. One of the largest riots in the country's history occurred at one of his concerts, held in a relatively small outdoor venue in New York State. Concertgoers were attacked while police stood by and watched. There are photos of police beating black men with batons, including one decorated African-American returned serviceman, as well as taking down the number-plates of concertgoers’ cars to add to the government’s ‘Communist’ file. Around 200 people were injured trying to leave the concert. After that, many towns and cities tried to stop Big Paul performing in any venue. One large city council tried to ban his performing on the grounds that with the possibility of rioting, insurance for the city would be too costly.

Outside of America though, Robeson remained a star. His recordings still sold and he continued to receive invitations to perform around the world. To prevent this, for eight years the US government took away his passport. He was trapped inside a country where he had almost no opportunities to work. The State Department gave as its reasons: that he promoted the independence struggles of colonised people in Africa and Asia and that he criticised the treatment of African-Americans by their government. Both were true. But even to escape the punitive restrictions that now bound him, Big Paul wouldn't let up.

He charged the US government with genocide before the United Nations, over its failure to outlaw the lynching of black men in the South. And while he couldn't perform in large concert halls any more, he continued to sing in church halls and at union gatherings, and down the new transatlantic phone line to public gatherings in Britain, sometimes of thousands of people. He sang and spoke wherever people would listen, determined to still get his message out.

In 1958, after eight years, the government was finally compelled by the courts to return his passport. No longer young, Big Paul and his indomitable wife Essie headed to London and began to tour again. In 1960 they came to Australia and in this Into the Music program we hear some rare archival interviews with Robeson and with people who experienced the magic of his concerts, whether in a town hall or on the building site of the new Sydney Opera House.

They speak in these recordings about the feeling of warmth and compassion he projected—of that amazing voice and of his huge size, but especially his gentleness. He and Essie asked to meet indigenous people throughout Australia and New Zealand and Robeson told the press, ‘There's no such thing as a backward human being, there is only a society which says they are backward.’

Indigenous activist Faith Bandler talks in those archival recordings about the tears that burst from Robeson when he was shown a documentary film of the conditions that Aboriginal people were living under in the Warburton Ranges. This was an area where the Maralinga atomic tests had taken place. She says he became furious and promised he would return to help them. They would go to the centre of the country together, he said, and force the Australian government to take notice of the conditions of its people.

He never returned to Australia. Back in Europe, Robeson travelled with a film crew to Moscow for a concert. Essie was not with him. It was now 1961. Stalin was dead and five years earlier, in a secret speech that rapidly became known to the outside world, the new leader, Khrushchev, had denounced Stalin’s ‘personality cult’ and brutal purges. Nobody knows what Robeson thought of those revelations. He didn’t talk about them publicly and left no writing about them.

Like other Communist sympathisers, up until then he probably believed that the whispers about the persecution of Jews, intellectuals and anyone who threatened Stalin were simply US propaganda. On a visit to Moscow in 1949, when Big Paul asked to meet with Jewish friends from previous visits, he learned firsthand that this was not the case. In protest, he ended his Moscow concert by singing in Yiddish the Song of Resistance of the Warsaw Ghetto. An edited recording of that extraordinary performance still exists, and is available on YouTube. Some people booed the song but many more cheered and cheered.

Nevertheless, despite what he had learned, Robeson continued to support the work towards equality and a just society he still believed was taking place in the Soviet Union, and never said anything publicly to undermine it. With his international profile, he was still a significant weapon for the Soviet Union in the propaganda war.

One night in 1961, while he was on that trip to Moscow to perform, a (reportedly) uncharacteristically wild party was held in Big Paul’s hotel suite. According to his son, Paul Jr, it’s not clear who organised the party but he says it wasn’t his father, or the Soviet government. It just seems to have happened. The Soviet Union was going through a period of relaxed rules under the new leader and all sorts of people were coming out of the woodwork, including dissidents. Some were at the party.

At some stage during the evening Big Paul didn’t feel well and locked himself in his room. He began to feel worthless and depressed, he hallucinated and towards morning he attempted to kill himself by slitting his wrists. He told this to Paul Jr. when his son, who had been contacted by the Soviet authorities, arrived in Moscow a couple of days later. Paul Jr. believes the CIA arranged for his father to be drugged.

He says there was no evidence on the footage taken by the documentary film crew who were following Robeson around during this Moscow visit of any depression before that night. At the time the CIA was running a project called MKUltra, designed to manipulate people's mental states and alter brain function. The program included the surreptitious administration of drugs including LSD; also hypnosis, sensory deprivation, isolation, verbal and sexual abuse, as well as various forms of torture.

Essie joined them and Big Paul was taken to a Soviet sanatorium to recover. When he was stable, the family headed back to London. Once there Robeson relapsed and was placed in a psychiatric hospital called the Priory. The treatment was extreme. Big Paul received 54 doses of electroshock therapy during the two years he was at the Priory. Paul Jr. is on record saying he believes the treatment his father received there was part of the MKUltra project. He believes the CIA wanted to neutralise his father.

After years of requests for access to his father’s Priory medical records, almost forty years later in 1999 Paul Jr. finally received them. He says that according to the records, his father was being treated for a non-specific depression. Aside from the 54 doses of electroshock therapy, the doctors also prescribed a cocktail of powerful depressive and anti-depressive drugs. Essie approved the treatment, over her son’s protests. The physicians at the Priory had never requested access to his father’s previous medical records and Big Paul received no psychotherapy during those two years. He was never the same man again.

Not everyone agrees with Paul Jr. that his father was drugged or subjected to CIA controlled mind de-patterning. Some believe that the years of US government pressure and his public rejection by much of the country during the late 1940s and the 1950s were enough to break anyone and it was only a surprise Big Paul hadn’t collapsed from the strain earlier. Some suggested he must have had a tendency towards bipolar behaviour all along, although that illness was never diagnosed.

In August 1963, disturbed by his treatment at the Priory, friends finally managed to have Robeson transferred to the Buch Clinic in East Berlin. The doctors there used psychotherapy and less medication but while Robeson improved they still found him to be without initiative. They questioned the high level of barbiturates and ECT that had been administered in London. His doctor advised that, ‘what little is left of Paul's health must be quietly conserved.’

After returning to the United States later in 1963, Robeson briefly participated in the burgeoning Civil Rights movement but not for long. He continued to refuse to repudiate the Soviet Union or Communism and as a result was not accepted within the mainstream Civil Rights power structure. Regardless, from 1965 his health was too poor to allow him to be politically active. The result was that for most Americans his name and deeds remained forgotten for decades to come. He did not appear in the history of the fight for civil rights. Today that is changing and Big Paul is finally being recognised for the ground-breaking work he did in fighting for black Americans' and workers’ rights and the rights of colonised peoples around the world.

Robeson died in 1976. Two years later his films were shown on American television for the first time. Show Boat, with 'Ol’ Man River', the song for which he’s best known, finally appeared on US screens in 1983. More than twenty years after his death, he was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Around the world festivals and awards are now named after him, and his work towards ending apartheid in South Africa has been posthumously rewarded by the United Nations General Assembly.

Robeson’s epitaph quotes his words from the Spanish Civil War, when he travelled to the front line to sing for the International Brigade volunteers who’d come from around the world to fight fascism: ‘The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.’

This article was first published on 7/6/13. Find out more at Into The Music.

How Paul Robeson found his political voice in the Welsh valleys

Paul Robeson possessed one of the most beautiful voices of the 20th century. He was an acclaimed stage actor. He could sing in more than 20 different languages; he held a law degree; he won prizes for oratory. He was widely acknowledged as the greatest American footballer of his generation. But he was also a political activist, who, in the 1930s and 1940s, exerted an influence comparable to Martin Luther King and Malcolm X in a later era.

The son of an escaped slave, Robeson built his career despite the segregation of the Jim Crow laws – basically, an American apartheid system that controlled every aspect of African American life. He came to London with his wife Eslanda – known as Essie – partly to escape the crushing racism of his homeland. Yet later in life he always insisted that he became a radical as much because of his experiences in Britain as in America. In particular, he developed a deep bond with the labour movement – particularly with the miners of Wales. That was why, in 2016, I travelled from my home in Australia to visit the landscape that shaped Robeson’s politics.

Pontypridd was a village carved out of stone. Grey terraced cottages, grey cobbled streets, and an ancient grey bridge arching across the River Taff.

The sky was slate, too, a stark contrast with the surrounding hills, which were streaked with seasonal russet, teal and laurel.

I was accustomed to towns that sprawled, as white settlers stretched themselves out to occupy a newly colonised land. Pontypridd, I realised, huddled. Its pubs and churches and old-fashioned stores were clutched tightly in the valley, in a cosy snugness that left me feeling a long way from home. I’d come here to see Beverley Humphreys, a singer and the host of Beverley’s World of Music on BBC Wales.

“I have a strong feeling that we might meet in October!” she’d written, when I’d emailed her about the Paul Robeson exhibition she was organising. “I know from personal experience that once you start delving into Paul Robeson’s life, he just won’t leave you alone.”

In that correspondence, she’d described Pontypridd as the ideal place to grasp Paul’s rich relationship with Wales and its people. I knew that, in the winter of 1929, Paul had been returning from a matinee performance of Show Boat [in London] when he heard male voices wafting from the street. He stopped, startled by the perfect harmonisation and then by the realisation that the singers, when they came into view, were working men, carrying protest banners as they sang.

By accident, he’d encountered a party of Welsh miners from the Rhondda valley. They were stragglers from the great working-class army routed during what the poet Idris Davies called the “summer of soups and speeches” – the general strike of 1926. Blacklisted by their employers after the unions’ defeat, they had walked all the way to London searching for ways to feed their families. By then, Robeson’s stardom and wealth were sufficient to insulate him from the immiseration facing many British workers, as the industrialised world sank into the economic downturn known as the Great Depression.

Yet he remembered his father’s dependence on charity, and he was temperamentally sympathetic to the underdog. Without hesitation, he joined the march.

Some 50 years later, [his son] Pauli Robeson visited the Talygarn Miners’ Rehabilitation Centre and met an elderly man who’d been present on that day in 1929. The old miner talked of how stunned the marchers had been when Robeson attached himself to their procession: a huge African American stranger in formal attire incongruous next to the half-starved Welshmen in their rough-hewn clothes and mining boots.

But Robeson had a talent for friendship, and the men were grateful for his support. He had remained with the protest until they stopped outside a city building, and then he leaped on to the stone steps to sing Ol’ Man River and a selection of spirituals chosen to entertain his new comrades but also because sorrow songs, with their blend of pain and hope, expressed emotions that he thought desperate men far from home might be feeling.

Afterwards, he gave a donation so the miners could ride the train back to Wales, in a carriage crammed with clothing and food.

That was how it began. Before the year was out, he’d contributed the proceeds of a concert to the Welsh miners’ relief fund; on his subsequent tour, he sang for the men and their families in Cardiff, Neath, and Aberdare, and visited the Talygarn miners’ rest home in Pontyclun.

From then on, his ties with Wales only grew.

Robeson remained [living] in Buckingham Street, London. He and Essie maintained a public profile as a celebrity couple, still mixing easily with polite society and the intelligentsia. But Robeson was now aware of the labour movement, and began to pay attention to its victories and defeats. His frequent visits to mining towns in Wales were part of that newfound political orientation.

“You can see why he’s remembered around here,” Humphreys said. “He was so famous when he made those connections, and the Welsh mining community was so very cowed. In the wake of the general strike, people felt pretty hopeless.”

A Robeson exhibition opened in Pontypridd in October 2015 and was an echo of a much grander presentation from 2001, which Humphreys had assembled with Hywel Francis, then Labour MP for Aberavon, and Paul Robeson Jr [Robeson’s son died in 2014]. It was first shown at the National Museum in Cardiff and then toured the country.

Staging that event had been a revelation for Humphreys. She’d known that memories of Robeson ran deep in Wales, but she’d still been astonished by the response. Every day of the exhibit, people shared their recollections, speaking with a hushed fervour about encounters with Paul that had stayed with them for ever.

Paul’s interactions with Wales were shaped by the violence of mining life: the everyday hardship of long hours and low wages, but also the sudden spectacular catastrophes that decimated communities. In 1934, he’d been performing in Caernarfon when news arrived of a disaster in the Gresford colliery. The mine there had caught fire, creating an inferno so intense that most of the 266 men who died underground, in darkness and smoke, were never brought to the surface for burial. At once, Robeson offered his fees for the Caernarfon concert to the fund established for the orphans and children of the dead – an important donation materially, but far more meaningful as a moral and political gesture.

That was part, Humphreys said, of why Wales remembered him. He was by then among the most famous stars of the day, the recording artist whose songs many hummed, and yet he was showing an impoverished and struggling community – people who felt themselves isolated and abandoned — that he cared deeply about them.

And the continuing affection for Robeson was more than a recollection of generosity. “The Welsh sensed the relationship was reciprocal, said Humphreys. “That he was deriving something from their friendships, from seeing how people in the mining communities supported one another and cared for one another. He later said he learned more from the white working class in Wales than from anyone.”.

Certainly, Robeson discovered Wales – and the British working class in general – at just the right time. He’d signed up, with great hopes, for a film version of [Eugene O’Neill’s play] The Emperor Jones in 1933 – the first commercial film with a black man in the lead. But the process played out according to a familiar and dispiriting pattern. Robeson’s contract stipulated that, during his return to America, he wouldn’t be asked to film in Jim Crow states. Star or not, it was impossible to be shielded from institutional racism. At the end of his stay, as he arrived at a swanky New York function, he was directed to the servants’ entrance rather than the elevator. One witness said he had to be dissuaded from punching out the doorman, in a manifestation of anger he’d never have revealed in the past.

The Emperor Jones itself was still very much shaped by conservative sensibilities: among other humiliations, the studio darkened the skin of his co-star, lest audiences thought Robeson was kissing a white woman. Not surprisingly, while white critics loved the film and Robeson’s performance, he was again attacked in the African American press for presenting a demeaning stereotype.

A few years earlier, he might have found refuge in London from the impossible dilemmas confronting a black artist in America. But he’d learned to see respectable England as disconcertingly similar, albeit with its prejudices expressed through nicely graduated hierarchies of social class. To friends, he spoke of his dismay at how the British upper orders related to those below them. He was ready, both intellectually and emotionally, for the encounter with the Welsh labour movement.

“There was just something,” Humphreys said, “that drew Welsh people and Paul Robeson together. I think it was like a love affair, in a way.” And that seemed entirely right.

The next morning, Humphreys and I walked down the hill, beneath a sky that warned constantly of rain. We made our way to St David’s Uniting Church on Gelliwastad Road. From the outside, it seemed like a typically stern embodiment of Victorian religiosity: a grey, rather grim legacy of the 1880s.

Inside, though, the traditional church interior – the pews, the pulpit, the altar – was supplemented by a huge banner from the Abercrave lodge of the National Union of Mineworkers, hanging just below the stained-glass windows. Workers of the world unite for peace and socialism, it proclaimed, with an image of a black miner holding a lamp out to his white comrade in front of a globe of the world.

The walls held huge photos of Paul Robeson: in his football helmet on the field at Rutgers [University]; on a concert stage, his mouth open in song; marching on a picket line. These were the displays extracted from the 2001 exhibition.

We chatted with parishioners, who were taking turns to keep the Robeson display open during the day for black history month.

The service itself reminded me of my morning in the Witherspoon Street church, except that, while in Princeton [where Robeson was born] I’d marvelled at the worshippers’ command of the black vocal tradition, here I was confronted by the harmonic power of Welsh choristers: the old hymns voiced in a great wall of sound resonating and reverberating throughout the interior.

Robeson, of course, had made that comparison many times. Both the Wesleyan chapels of the Welsh miners and the churches in which he’d worshipped with his father were, he said, places where a weary and oppressed people drew succour from prayer and song.

His movie The Proud Valley (released as The Tunnel in the US), which had brought him to Pontypridd in 1939, rested on precisely that conceit. In the film (the only one of his movies in which he took much pride), Robeson played David Goliath, an unemployed seaman who wanders into the Welsh valley and is embraced by the miners when the choir leader hears him sing.

Throughout the 1930s, the analogy between African Americans and workers in Britain (and especially Wales) helped reorient Robeson, both aesthetically and politically, after his disillusionment with the English establishment.

His contact with working-class communities in Britain provided him with an important reassurance. He told his friend Marie Seton about a letter he received from a cotton-spinner during one of his tours. “This man said he understood my singing, for while my father was working as a slave, his own father was working as a wage slave in the mills of Manchester.”

That was in northern England, but he experienced a similar commonality everywhere, and it pleased and intrigued him. If the slave songs of the US were worth celebrating, what about the music emerging from other oppressed communities? What connections might the exploration of distinctive cultural traditions forge between different peoples?

Significantly, it was in Wales where Robeson first articulated this new perspective. In 1934, he gave a concert in Wrexham, in north Wales, between the Welsh mountains and the lower Dee valley alongside the border with England. Yet again it was a charity performance, staged at the Majestic Cinema for the benefit of the St John Ambulance Association.

During the visit, Robeson was interviewed by the local paper, and he told the writer he was no longer wedded to a classical repertoire. He’d come to regard himself as a folk singer, devoted to what he called “the eternal music of common humanity”. To that end, he was studying languages, working his way haphazardly through Russian, German, French, Dutch, Hungarian, Turkish, Hebrew, and sundry other tongues so as to perform the songs of different cultures in the tongues in which they had been written. He had become, he said, a singer for the people.

The confidence of that statement reflected another lesson drawn primarily from Wales. In African American life, the black church had mattered so much because religion provided almost the only institutional stability for people buffeted by racial oppression. In particular, because Jim Crow segregated the workplace, black communities struggled to form and maintain trade unions. Wales, though, was different. The miners found consolation in religion, with every village dotted with chapels. But they believed just as fervently in trade unionism.

The Gresford disaster showed why. In an industry such as mining, you relied on your workmates – both to get the job done safely and to stand up for your rights. The battle was necessarily collective. A single miner possessed no power at all; the miners as a whole, however, could shut down the entire nation, as they’d demonstrated in 1926.

In particular, the cooperation mandated by modern industry might, at least in theory, break down the prejudices that divided workers – even, perhaps, the stigma attached to race. That was the point Robeson dramatised in The Proud Valley, a film in which the solidarity of the workplace overcomes the miners’ suspicion about a dark-skinned stranger. “Aren’t we all black down that pit?” asks one of the men.

“It’s from the miners in Wales,” Robeson explained, “[that] I first understood the struggle of Negro and white together.”

“To understand Paul’s relationship with Wales,” Humphreys told me the following day, “you need to understand Tiger Bay.”

She introduced me to Lesley Clarke and to Harry Ernest and his son Ian. The three of them came from Tiger Bay, the centre of Wales’s black community. They’d worked on the original exhibition in Cardiff, after Humphreys had insisted that the National Gallery employ black guides, and now they’d come to Pontypridd to witness the new display.

At 82, Lesley Clarke was thin but sprightly and alert. She spoke slowly and carefully. “I hadn’t realised there was a colour bar until I left Tiger Bay. When I went to grammar school, I realised for the first time that there were people who just didn’t like coloured people. Didn’t know anything about us, but didn’t like us. I didn’t know I was poor and I didn’t know I was black: all I knew was that I was me.”

Tiger Bay was forged by some of the worst racial attacks in British history. In June 1919, returning soldiers encountered a group of black men walking with white women. Outraged, the troops, led by colonials (mostly Australians), rampaged throughout Butetown, attacking people of colour, destroying houses, and leaving four dead.

For Clarke and Ernest’s generation, the colour bar was very real, especially in employment. Ernest was impish and bald, and his eyes crinkled as he spoke, almost as if he took a perverse humour in the recollection. “We’d ask if a job was open,” he said, “and soon as they said yes, we’d say, ‘Can I come for an interview right now?’ To narrow the gap, because the minute you got there they would say, ‘Oh, the job is gone.’”

“The minute they saw you were black, that was it,” said Clarke. “You just took it for granted that it was going to happen. There were very few outlets, especially for girls. You either worked in the brush factory or you worked in Ziggy’s, selling rags and whatnot, or there was a place just over the bridge that did uniforms.”

“I worked in the brush factory for a while,” Ernest said. “Oh, Jesus!”

He shook his head and laughed in dismay. “Jesus.”

Robeson had reached out to the Welsh miners when his career was at its height. They came back to him at his lowest ebb, almost two decades later, at a time when all he’d achieved seemed to have been taken from him. In the midst of the cold war, the FBI prevented Robeson from performing at home. [He’d proclaimed his sympathy for the Soviet Union ever since the mid-30s. That leftism now made him a target. He became, in Pete Seeger’s words, “the most blacklisted performer in America”, effectively silenced in his home country,] Worse still, the US state department confiscated his passport, so he could not travel abroad. He was left in a kind of limbo: silenced, isolated, and increasingly despairing.

On 5 October 1957, the Porthcawl Grand Pavilion filled with perhaps 5,000 people for the miners’ eisteddfod. Will Painter, the union leader, took to the microphone. After welcoming the delegates, he announced that they would soon hear from Paul Robeson, who’d be joining them via a transatlantic telephone line.

When Painter spoke again, he was addressing Robeson directly. “We are happy that it has been possible for us to arrange that you speak and sing to us today,” he said. “We would be far happier if you were with us in person.”

Miraculously, Robeson’s deep voice crackled out of the speakers in response. “My warmest greetings to the people of my beloved Wales, and a special hello to the miners of south Wales at your great festival. It is a privilege to be participating in this historic festival.”

He was seated in a studio in New York. Down the telephone line, he performed a selection of his songs, dedicating them to their joint struggle for what he called “a world where we can live abundant and dignified lives”.

The musical reply came from the mighty Treorchy Male Choir, the winners of that year’s eisteddfod, and a group that traces its history back to 1883. Robeson joined the choir in a performance of the Welsh national anthem, Land of My Fathers, before the entire audience – all 5,000 of them – serenaded him with We’ll Keep a Welcome. “This land you knew will still be singing,” they chorused. “When you come home again to Wales.”

Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, and Interviews, a Centennial Celebration

Citadel, 2002

https://theintercept.com/2020/07/15/the-revolutionary-life-of-paul-robeson-scholar-gerald-horne-on-the-great-antifascist-singer-artist-and-rebel/

The Revolutionary Life of Paul Robeson: Scholar Gerald Horne on the Great Anti-Fascist Singer, Artist, and Rebel

Historian Gerald Horne discusses the life and legacy of Paul Robeson, who committed himself to the liberation of oppressed people across the globe.

As Donald Trump campaigns for reelection, he is increasingly sounding like a fanatical Cold War relic, railing against the communists, anarchists, and socialists while pledging to protect the real Americans from this growing Red Menace. This week on Intercepted: As Trump vows to smash leftist movements, we take a comprehensive look at the life of the revolutionary Black socialist, anti-fascist, and artist Paul Robeson. University of Houston historian Gerald Horne, author of “Paul Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary,” discusses Robeson’s life from his early years to his time in Europe on the brink of a fascist war. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson rose to international fame as a singer and actor, but committed himself to the liberation of oppressed people across the globe and was a tenacious fighter for the freedom of Black people in the U.S. Robeson was heavily surveilled by the FBI and CIA, dragged before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and was stripped of his passport by the U.S. government.

Audio of Robeson’s testimony at the House Un-American Activities Committee, used throughout this episode, is a dramatization by actor James Earl Jones in the stage play, “Are You Now or Have You Ever Been?”

Sean Hannity: Joining us now on the phone is President Donald Trump from the White House tonight. Mr. President, thank you, sir, for being with us.

Donald Trump: Well, thank you very much. And how good is Mark?

[Sounds of toilet]

SH: I want to start — Um, Mr. President? We have an election in 117 days, Mr. President, and —

DJT: I actually took cognitive tests.

SH: Ok.

DJT: Very recently when I proved I was all there because I aced it. I aced the test —

SH: You know —

DJT: — in front of doctors and they were very surprised. They said that’s an unbelievable thing. Rarely does anybody do what you just did.

SH: What is your second term agenda?

DJT: Our country will suffer. Our stock markets will crash. Cases all over the place. People dying.

SH: Thank you for your time. We appreciate you being with us. And 117 days to go. Alright.

DJT: Thank you very much, Sean. Thank you.

[Musical interlude]

Jeremy Scahill: This is Intercepted.

[Musical interlude]

JS: I’m Jeremy Scahill, coming to you from my basement in New York City. And this is episode 138 of Intercepted.

Catherine Herridge [CBS]: Why are African Americans still dying at the hands of law enforcement in this country?

DJT: And so are white people. So are white people. What a terrible question to ask. So are white people — more white people by the way.

JS: The United States is in the midst of a period of great reckoning. While many major media outlets have moved on in their coverage, demonstrations for racial justice and Black Lives continue in cities and towns across this country.

Protesters: George Floyd! Say his name! George Floyd! Say his name! George Floyd!

JS: At the same time, the pandemic is continuing its carnage, due in no small part to the criminal incompetence of President Donald Trump. While Wall Street celebrates its gains and basks in the perceived contradictions, workers across this country are suffering. Millions of people are at risk of losing or already have already lost their employer-based health care. The paltry means-tested so-called economic stimulus was at its inception an inadequate bandaid, and now the wounds on working families are becoming infected. At the same time, the billions doled out to corporations are shrouded in unaccountability and secrecy.

And, as Trump campaigns for re-election, he is increasingly sounding like an early Cold War fanatic, railing against the communists, anarchists, socialists while pledging to protect the real Americans from this growing Red Menace.

DJT: We are now in the process of defeating the radical left, the marxists, the anarchists, the agitators, the looters, and people who, in many instances, have absolutely no clue what they are doing.

JS: In these times, the long shadow of history stretches over us all. And in thinking of the magnitude of the current world and national crisis, I’ve found myself reading books, watching films, listening to music that was produced during times of crisis and struggle throughout history.

[“Water Boy” sung by Paul Robeson plays.]

Paul Robeson: [Singing] Water boy, where are you hiding? If you don’t come, I’m going to tell your Mamie.

JS: One of the great stories of the past century is that of the life of Paul Robeson. He was born in New Jersey to a father who escaped slavery. He was an athlete, a lawyer, an actor, and a singer. And his songs propelled him to international fame beginning in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

But Paul Robeson represented something much bigger than his art or his biography. His ascent to fame came as the world was in upheaval, the market crash and the Great Depression, the rise of fascist forces in Europe, and the grinding oppression of Jim Crow America. Robeson spent many of his prime years living outside the United States. He said he felt more free as a Black artist abroad than he did in the land of his birth. He traveled the world performing in the great concert halls and theater venues of Europe and beyond. He was enamored of the Soviet Union and the great hope that he placed in the liberation of Black people from the shackles of colonialism in Africa. He mastered several languages, among them German and Russian, and he gave in London what is to this day considered to be one of the greatest performances of Othello ever staged.

Paul Robeson reciting Shakespeare’s Othello: Soft you, a word or two before you go. I have done the state some service, and they know’t. No more of that. I pray you, in your letters, when you shall these unlucky deeds relate, speak of me as I am. Nothing extenuate, nor set down aught in malice.

JS: Paul Robeson was an international man of resistance, of worker solidarity, and he was a proud Marxist. He could have lived a life of extreme comfort and luxury. He could have chosen to just be an artist. But at his core, Paul Robeson believed that the struggle to liberate workers across the globe and to overthrow the tyranny of fascists was connected to the liberation of Black people in the United States. And when Robeson was outside of the U.S. or inside of it, he always spoke with an international perspective. After visiting with coal miners in the Welsh valley in the U.K. in the 1950s, Robeson described his political evolution in a radio interview on KPFA.

PR: And I went down in the mines with the workers and they explained to me that Paul, you may be successful here in England, but your people suffer like ours. We are poor people. And you belong to us, you don’t belong to the bigwigs here in this country. And so I today feel as much at home in the Welsh valley as I would in my own Negro section in any city in the United States. And I just did a broadcast by transatlantic cable to the Welsh valley a few weeks ago. And here was the first understanding that the struggle of the Negro people, or of any people, cannot be by itself. That is, the human struggle. And so I was attracted then to… met many members of the Labor Party and my politics embraced also the common struggle of all oppressed peoples, including especially the working masses, specifically the laboring people of all the world. And that, that defines my philosophy. It’s a joing one of, we are a working people, a laboring people the Negro people. And there’s a unity between our struggle and those of white workers in the South. I’ve had white workers shake my hand and say, “Paul, we’re fighting for the same thing.” And so this defines my attitude toward socialism, and toward many other things in the world. I do not believe that a few people should control the wealth of any land, that it should be a collective ownership.

JS: Today on the show, we are going to take a journey through the life and times of Paul Robeson. From his early years to his rise to fame, to his time in Europe on the brink of a fascist war. We will hear how Robeson traveled to the frontlines of the war against General Franco to perform for the international anti-fascist brigades. We’ll hear of the FBI investigations, Robeson’s appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee and of how Paul Robeson was stripped of his passport by a U.S. government afraid that he would become a “Black Stalin.”

Our guest for today’s program is the historian and scholar Dr. Gerald Horne. He currently holds the John J. and Rebecca Moores Chair of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston. He is a prolific author and among his works is the recent book “Paul Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary.” Dr. Horne’s newest book, just published, is “The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century.” Dr. Gerald Horne, thank you so much for joining us here on Intercepted.

Gerald Horne: Thank you for inviting me.

JS: As we’ve watched these events unfold over the past months, not just with the pandemic, but centrally with the uprisings that we’ve seen around the country in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd, I found myself thinking a lot about Paul Robeson.

Dramatization by James Earl Jones as Paul Robeson: Is that when I am abroad, I speak out against injustices against the Negro people in this land. That is why I’m here. I’m not being tried for whether I’m a communist. I’m being tried for fighting for the rights of my people, who are still second class citizens in this country, in this United States of America. My father was a slave. I stand here struggling for the rights of my people to be full citizens in this country. And they are not.

JS: Paul Robeson was a militant anti-fascist, a radical thinker, and in your book on him, you say that he was the forerunner to Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, and that in studying his life we can understand better this history that we all continue to live through. For people that are not familiar, just give an overview of why you put Paul Robeson in that historical context.

GH: Well, Paul Robeson was born in New Jersey in 1898, passes away in Philadelphia in 1976. In between, he was a star scholar at Rutgers University, one of the few Black Americans admitted to that state school. He was also an All-American football player and a baseball catcher. He also attended Columbia University Law School and practiced law for a while. But it was soon revealed and discovered that he had a marvelous singing voice.

PR: [Singing] I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night, alive as you and me. Says I, “But Joe, you’re ten years dead.” “I never died” says he, “I never died” says he.

GH: And he quickly transferred to being a star concert singer and a star of the stage, and ultimately film.

PR: Lord God of Abraham, Isaac and Israel.

GH: From the 1920s up through the late 1930s, he was actually in exile. He lived in London. And there he came into contact with many anticolonial leaders. But a turning point in Paul Robeson’s life comes in the early 1930s, when he comes face to face with fascism as it’s rising in Germany. And his transition to becoming this stellar anti-fascist activist is assisted in no small measure by his good friend, another Black lawyer, speaking of William Patterson, who went on to spearhead the defense of the Scottsboro Nine in the 1930s. Recall these are the nine Black youth in Alabama who are accused falsely of sexual molestation of two Euro-American women. Their case becomes a cause célèbre all over the world. It’s not unlike the antiapartheid movement, which in the 1980s and 1990s becomes an international movement. And in fact I argue that the Scottsboro Nine, in some ways, was a precursor and necessary prelude to the eruption of the anti-Jim Crow movement in the 1950s in the United States of America.

In any case, Paul Robeson becomes an advocate of socialism. He visits the Soviet Union early on. The turning point, in a sense, in Paul Robeson’s life comes with the dawning of what London would call World War II, that is to say 1939. And he felt that with his family he might be caught in the midst of a war so he decided to return to the land of his birth. And for a while it seemed as if he was in accord with main political trends in the United States after all. But alas, with the end of World War II, you see the rise of the Red Scare, the Cold War. Robeson quickly becomes persona non grata. A turning point again in his star-crossed life comes when he confronts President Harry Truman in the White House, when Mr. Robeson is campaigning against lynching — the extrajudicial murder of Black Americans, non unlike what befell George Floyd in Minnesota in May 2020.

PR: A very broad committee went in to protest the lynchings of the Negro boys in the South. He said that it wasn’t politically expedient to do anything about lynching.

GH: And as Mr. Truman was being berated by Mr. Robeson, therein you can espy the onset of the decline of Mr. Robeson. He quickly becomes “blacklisted.” He becomes an early victim of McCarthyism. He still has a certain kind of contact with the emerging civil rights movement. I mean, for example, he rubs shoulders with Malcolm X while in London. He confers with Dr. Martin Luther King and some of Dr. King’s representatives. But it’s fair to say that the final decade of his life is spent generally in seclusion and he passes away in Philadelphia in early 1976.

JS: As Robeson discovers his gift for the performance arts, particularly singing and acting in the United States, and he is given some early opportunities to perform in the plays of Eugene O’Neill, what was Robeson’s life like as he entered entertainment? And ultimately what brings him then to Europe?

GH: After leaving Rutgers, he enrolls in law school and is well on his way to becoming a well-paid lawyer. But like many people, that is to say many Black people in particular, he felt that his individual success was insignificant compared to the kind of relentless Jim Crow and mindless lynching that his people were being subjected to. But, as suggested, he left that particular life and that particular career. And then, in the early 1920s, moving to London on the premise, which proved out, that there would be more opportunities in London for a Black performer than in the land of his birth.

While in London, he’s exposed to a number of radical intellectuals when Britain was considered to be a so-called top dog in the imperialist and capitalist world. That process led to the creation of a number of leading anti-fascist, anti-imperialist intellectuals. And this kind of environment influenced Robeson quite deeply and, as suggested, along with his trip to Germany as fascism was being born, helped to move him decisively to the left.

PR: I would say that, unquestionably, I am an American. Born there. My father slaved there. Upon the backs of my people was developed the primary wealth of America. The primary wealth. There’s a lot of America that belongs to me yet, you understand? But just like a Scottish-American is proud of being from Scotland, I’m proud for being African. Now in our school books they tried to tell me that all Africans were savages until I got to London and found that most Africans that I knew were going to Oxford and Cambridge and doing very well and learned their culture. So I would say today that I’m an American who is infinitely prouder to be of African descent, no question about it, no question about it. I’m an Afro-American and I don’t use the word American ever loosely again.

JS: In 1934, he travels to Moscow for the first time and Robeson said that, “Through Africa I found the Soviet Union.” Talk about how that first trip to the Soviet Union really profoundly changed Robeson’s trajectory.

GH: Well, you know, I find that people in the United States, at least certain elites and certain folks who don’t know better, they’ve really been able to convince Black people in the United States that everybody hates us. You go anywhere in the world, they don’t like Black people. Which, of course, sort of lets U.S. Jim Crow and U.S. apartheid off the hook, lets U.S. white supremacy off the hook because the U.S. is just reflecting these global trends. But of course you don’t have to be a historical materialist to recognize that these anti-Black attitudes come out of a particular cultural and historical context.

And if you look at Russia, in particular, a European country that, I think it’s fair to say, that was not as avid a participant in the African slave trade as some of its Western European counterparts — including England and France and Portugal and Spain most notably — and not only that but the man who’s considered to be the founder of the modern Russian language, speaking of Pushkin, was of partial African descent himself and still is seen as a hero today.

Then there’s the rather pragmatic political point, which is that the Soviet Union, at that time, needless to say, was being encircled by a number of antagonists, including imperial London, including imperial France, including Germany. So there was a pragmatic reason for Moscow to try to win favor amongst the colonial subjects of its antagonists. Not to mention those who were victimized by bigotry and racism and white supremacy in the United States of America.

There were many good reasons and many sound historical reasons for Moscow to open its embrace to Robeson. It helped to solidify his already growing attraction to the ideas of socialism. And of course he was not alone in this. This circle included many of the Black intellectuals of that time and this pro-Moscow, pro-socialist attitude is not unusual because Black people were looking for allies against U.S. imperialism and white supremacy. Just like by June 22, 1941, when Germany invades the Soviet Union, the United States is looking for allies. Which is why you have this rapid turn about in the United States of America with regard to its opinion of the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin becomes man of the year according to Time magazine. You have Hollywood producing pro-Soviet movies, which I think you can still find on YouTube.

[Mission to Moscow clip plays.]

Mr. Davies: I believe, sir, that history will record you as a great builder for the benefit of mankind.

Stalin: It is not my achievement, Mr. Davies. Our five-year plans were conceived by Lenin and carried out by the people themselves.

Mr. Davies: The results have been a revelation to me. I confess I wasn’t prepared for what I found here. You see, Mr. Stalin, I’m a capitalist as you probably know.

Stalin: Yes, we know you’re a capitalist. There can be no doubt about that.

GH: Which presents a vision of the Soviet Union which contrasts with the pre-World War II and post-World War II approach. And of course we all know that after the war ends, these Hollywood creators are then dragged to Washington and grilled as to why they made these pro-Soviet movies.

Newsreel: Investigating alleged communism in Hollywood, the Washington Committee on Un-American Activities has been hearing the testimony of prominent film personalities.

Eric Johnston: The motion picture industry has been accused of putting subversive and un-American propaganda on the screen. We deny that without any reservation. The pictures themselves are complete proof of its falsity.

GH: Of course, the answer was that Franklin Delanoe Roosevelt suggested that this was a good idea in order to massage U.S. public consciousness so that the U.S. population would be more prone to go along with this alliance with the Soviet Union against imperial Tokyo and fascist Berlin.

And so Robeson was part of that overall political environment. The difference is, is that after 1945, the U.S. did a 180 degree reversal with regard to its pro-Soviet attitudes. Robeson chose not to, not least because the Soviets were still supporting African liberation movements. Now this rather simple political historical understanding, it’s oftentimes difficult for whatever reason for many of our friends in the United States to grasp.

PR: For the first time, as I stepped on Soviet soil, I felt myself a full human being — a full human being. So it’s unthinkable for me today that colored peoples in any part of the world would ever join a war or attacks upon the Soviet Union. I’m an anti-fascist and I would feel perhaps that any war against the Soviet Union would be a fascist war. Why not talk about peace and friendship with the Soviet people.

Journalist: What are your political opinions? Have they been changed today?

PR: My political opinions about the Soviet Union have only been deepened. As I said, in the Soviet Union, I’m a believer in socialism and I would say with Dr. Du Bois that I believe that the socialist lands, in the sense of the Soviet Union, China, and the peoples’ democracies are the hope — can I repeat it? — the hope for the future.

JS: Part of history that I think is so vital that people understand but it’s almost never talked about, is the Spanish Civil War that preceded Hitler’s war of conquest and genocide throughout Europe and eventually extending elsewhere. But you had, from the United States just as an example, three thousand people who signed up under the auspices of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade — people who were communists or anarchists, socialists — that went to Spain to fight against the rise of fascism. And, in fact, the United States officially declared itself to be neutral. And as you write about, Paul Robeson himself goes to the frontlines in Spain to perform for the anti-fascist forces that really were at the vanguard of trying to prevent fascism from taking hold in Europe.

PR [Singing]: But your courageous children. But your courageous children.

JS: Talk about that episode and why Robeson decided to go to Spain to perform on the front lines for the anti-fascists.

GH: Robeson was not alone in terms of those sentiments in favor of the Republican regime in Spain that was being challenged by the ultimate victor, the proto-fascist Francisco Franco who, as you correctly suggest, was backed by the fascist powers. But not only backed by the fascist powers, Berlin not least, but also, you may recall, that Henry Ford, one of the top manufacturers, as they’re called in the United States — and his eponymous automobile company is still with us. And so on the other side of the ledger, not only had Robeson, who went to Spain to sing before the beleaguered forces and troops, but Langston Hughes, who was perhaps the leading Black writer of the 20th century was also a part of that crew that descended on Spain.

And, interestingly enough, a number of Black Americans whose names sadly have been lost to history, they were sufficiently motivated to go to Spain as well because, like Robeson, they felt that if fascism could be defeated on the Iberian peninsula that that would bode well for its close cousin, Jim Crow, being defeated on these shores. And likewise, if fascism were to emerge victorious on the Iberian peninsula, this would give a shot in the arm to its close cousin, speaking of Jim Crow, on these shores. And so that’s what motivated Robeson to go to Spain in the 1930s. Like his trip to fascist Germany, like his trip to the Soviet Union, this had a catalytic and a positive impact on his emerging anti-fascist consciousness and was one more factor that was pushing him steadily to the left.

JS: Yeah, I wanted to read a quote that you cite in your book from Robeson’s own description of why he travels to Spain to perform for the anti-fascist forces.

PR: I am deeply happy to contribute to this cause of Spanish culture and of the Basque children in particular. A cause which must concern everyone who stands for freedom, progressive democracy, and for humanity. Today, the artist cannot hold himself aloof.

JS: He said, “Every artist, every scientist must decide now where he stands. He has no alternative. There is no standing above the conflict on Olympian heights” since, “ the artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.” When Robeson was asked why he said because, “The history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people.” Put that in context.

GH: I still get chills when I hear that quote being rendered. Obviously he’s referring to the origins of capitalism itself, something I’ve dealt with in a number of books, including my most recent book, “The Dawning of the Apocalypse,” which deals with the 16th century. And as Karl Marx himself put it, capitalism comes upon the world stage dripping with blood — with the blood of Africans in particular because it was the African slave trade, one of the most profitable enterprises known to humankind. As you know, the African slave trade was the precursor for bringing millions of Africans to these shores, including my ancestors, I’m afraid to say. And after suffering through centuries of slavery, we were able to create conditions that led to a U.S. Civil War, culminating in 1865, and then we were then degraded by a century further of U.S. apartheid in this so-called land of liberty and land of freedom. So this is what Robeson was making reference to when he made those rather scalding comments about what was happening to Black people, what was happening to his people.

JS: Tell the story of how Robeson was impacted by the case of the Scottsboro Boys. This starts in 1931, where you have nine Black teenagers ranging in age from 13 to 19 years old who are falsely accused of raping two white women on a train.

Clarence Norris: The three of us were surrounded with a mob. They had shotguns, pistols, sticks, pieces of iron, everything. The crowd commenced to holler: Let’s take these Black sons of bitches up in here and put ’em to a tree. I did thought that I was going to die.

JS: Maybe set the Scottsboro Boys case and Robeson’s response to it in context.

GH: These nine Black youth are riding trains in the middle of a collapsing economy. It was quite common for folks to hop on trains to get from a city of unemployment to a city where they hoped there would be employment. These two women are riding the train too. There are controversies and confrontations between the nine Black youth, all from Dixie, and the two women. It leads to this allegation that turns out to not to be accurate that they had sexually molested these women. What happens is that the aforementioned William Patterson, who becomes a leader of the International Labor Defense, in many ways they take up the banner of the Scottsboro Nine. They use this case to illustrate the frailties, if you like, of Jim Crow, the noxious nature of white supremacy. Because the International Labor Defense has an international network, because the Communist Party and the Communist International, headquartered in the then Soviet Union, that is to say speaking of the latter, it’s part of an international organization. And so when this Communist International and International Labor Defense take up this case, they’re able to generate a worldwide movement against U.S. Jim Crow.

James W. Ford: It is only the Communist Party, which day in and day out, fights for every demand and need of the Negroes in the terror-and lynch-ridden South.

GH: Because of the disadvantageous conditions that Black Americans face in the United States of America, historically Black Americans have needed international solidarity and international support to make a step forward. And fortunately that was present in the 1930s. Now, it turns out that it takes quite a bit of activism to free the Scottsboro Nine. For most of the 1930s, despite this international protest, picketing at U.S. consulates and legations and embassies all over the world, boycotts of U.S. based corporations, etc., they still spend most of the 1930s in prison. But eventually, they are not executed — because they were definitely slated to be executed, which, I might say, was the fate of too many Black people, that is to say being accused falsely then either rushed to the electric chair of the gas chamber or dragged unceremoniously from the prison and lynched, that is to say murdered without due process of law. But fortunately that fate did not befall the Scottsboro Nine and it also, I should say, not only helped to give U.S. imperialism a black eye in the international community, it also helped to drive many Black people into the ranks of the U.S. Communist Party, including a number of its leaders. And certainly it was a factor in helping to bring Paul Robeson closer to the U.S. Communist Party. I should say at this point that in his testimony before the U.S. Congress in the 1950s, the interrogators said that he was a member of the U.S. Communist Party under a false flag, under a false name. He denied that. I guess because they were not expert interrogators, they did not ask him if he had been a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, and I suspect that he was. And in any case that remains an avenue of research that has not been fruitfully explored.

Unidentified Actor as Richard Arens: Are you now a member of the Communist Party?

James Earl Jones as Paul Robeson: Oh, please, please, please.

Unidentified Actor as Richard Arens: Please answer, will you, Mr. Robeson.

James Earl Jones as Paul Robeson: What is the Communist Party? What do you mean by that?

Unidentified Actor as Richard Arens: Are you now a member of the Communist Party?

James Earl Jones as Paul Robeson: Would you like to come to the ballot box when I vote and take out the ballot and see?

Unidentified Actor as Richard Arens: Mr. Chairman, I respectfully suggest that the witness be directed to answer the question.

Unidentified Actor as Chairman Francis E. Walter: You are directed to answer the question.

James Earl Jones as Paul Robeson: I invoke the Fifth Amendment and forget it.

Unidentified Actor as Richard Arens: I respectfully suggest the witness be directed to answer the question.

JS: Robeson is in Europe and he returns to the United States not just completely in the grips of the Jim Crow politics and reign of the leaders of the time, but also the FBI begins to investigate Paul Robeson as well. His activism is escalating during this time, and you had fears among powerful white interests in the United States that Robeson was going to become possibly a “Black Stalin.” Explain that.

GH: Historically, many Black people have fled the United States and have found homes in Western Europe in particular. But what happens is that with the rise of fascism and Hitler and Mussolini taking over most of Europe, they are not, shall we say, as friendly to these Black exiles as previous governments had been. And so many of them end up in concentration camps. Many of them perish. And this is what Robeson feared would befall him and so he decided the better part of wisdom was to get out of dodge, which actually made good sense.

But as already noted, he comes back to the United States and the United States is in the process of shifting to antifascism, shifts out of antifascism almost simultaneously with the signing of the treaty of surrender on the battleship Missouri in September 1945, as Japan surrenders. And then what happens is that this is taking place at a time when the United States is still officially a Jim Crow country. It’s still an apartheid country. The United States is a rigorously segregated society. But the flipside of that is that in some ways this hands the Black community on a silver platter to those who profess antiracism, which was quite unusual at the time. And so what happens is that Robeson has a certain modicum of popularity in the Black community. And this is at a time, too, when the left had not been purged from leadership of unions. Robeson in many ways was the titular leader, not only of the Black radical, or even Black progressive movement, but in some ways, a leader of the U.S. progressive movement as well. And it was felt by those who majored in hysteria that somehow this would catapult him into a leadership role in Washington where he would become the so-called Black Stalin that is ruling the United States, subjecting his political antagonists to labor camps and even worse. And this was part of the hysteria that gripped the United States at that moment. What unfolds is this rather adroit maneuver by U.S. ruling circles whereby those with foresight and vision, such as Robeson, Du Bois, et. al., are marginalized and, to a degree, are isolated. And at the same time you have this attempt to erode Jim Crow, per the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision of 1954 saying that U.S. apartheid now is unconstitutional. And so you have this anomaly where Black people somehow, at least on a formal level, procedural level, get the right to eat in restaurants that they had been barred from, but because of the weakening of progressive unions — and most Black people are working class and survive and are able to thrive because of being part of unions — but because of the weakening of unions, they don’t have the money to pay the bill at the restaurant.

JS: We are speaking to Dr. Gerald Horne of the University of Houston. In a moment, we’re going to continue this conversation by taking a look at the U.S. government’s investigation of Paul Robeson during the Red Scare period as the Cold War was intensifying. Stay with us.

[Paul Robeson performing his version of “Old Man River”]

You and me, we sweat and strain

Body all achin’ and racked with pain

Tote that barge and lift that bale