SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BAIKIDA CARROLL

(September 3-9)

BILLY DRUMMOND

(September 10-16)

BOBBY MCFERRIN

(September 17-23)

ALBERT KING

(September 24-30)

CLORA BRYANT

(October 1-7)

DEAN DIXON

(October 8-14)

DOROTHY DONEGAN

(October 15-21)

BOBBY BLUE BLAND

(October 22-28)

CARLOS SIMON

(October 29-November 4)

VALERIE CAPERS

(November 5-11)

CHARLES MCPHERSON

(November 12-18)

ROLAND HAYES

(November 19-25)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/charles-mcpherson-mn0000206020/biography

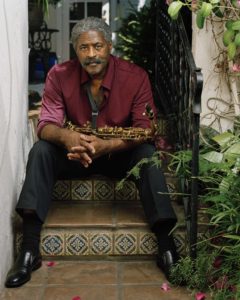

Charles McPherson

(b. July 24, 1939)

Biography by Scott Yanow

A Charlie Parker disciple who brings his own lyricism to the bebop language, Charles McPherson has been a reliable figure in modern mainstream jazz for more than 35 years. He played in the Detroit jazz scene of the mid-'50s, moved to New York in 1959, and within a year was working with Charles Mingus. McPherson and his friend Lonnie Hillyer succeeded Eric Dolphy and Ted Curson as regular members of Mingus' band in 1961 and he worked with the bassist off and on up until 1972. Although he and Hillyer had a short-lived quintet in 1966, McPherson was not a full-time leader until 1972. In 1978, he moved to San Diego, which has been his home ever since and sometimes he uses his son, Chuck McPherson, on drums. Charles McPherson, who helped out on the film Bird by playing some of the parts not taken from Charlie Parker records, has led dates through the years for Prestige (1964-1969), Mainstream, Xanadu, Discovery, and Arabesque.

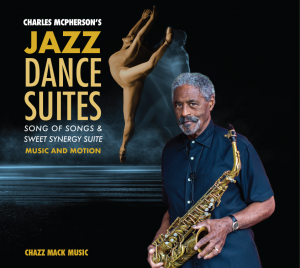

JAZZ DANCE SUITES

the buzz:

“….the original music had me entranced. Magnificent sounds somewhat inadequate! I doubt there will be a better album released this year. It is just so listenable, so danceable, so everything …”

bebop spoken here – Tuesday, August 04, 2020

Bebop luminary Charles McPherson explores the exciting relationship between jazz and dance art-forms on his new project, Jazz Dance Suites, due out September 25 via Chazz Mack Music.

JAZZIZ, The Week in Jazz

“…alluring lyricism and graceful improvisations are in splendid form on Jazz Dance Suites…”

J. Murph

Downbeat Review: ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Read More Reviews….

Legends – Fall Arts Preview

by George Varga, Union Tribune September 2019

Wynton

Marsalis, a long time admirer says: “Charles is the very definition of

excellence in our music. He’s the definitive master on his instrument.

He plays with exceptional harmonic accuracy and sophistication. He

performs free-flowing, melodic and thematically developed solos with

unbelievable fire and an unparalleled depth of soul.” Read the story here.

The enchanting “Jazz Dance Suites”

by George Varga, Union Tribune October 10, 2020

Internationally acclaimed saxophonist Charles McPherson is not the first jazz great to launch his own record label, perform a livestreamed concert or teach music classes online. But he is surely the first to do all three at the age of 81. And he is very likely the first octogenarian artist in any genre who is set to promote his new album with a drive-in concert. More…

Re-issue of “Illusions in Blue”

“McPherson has not merely remained true to his bop origins but has expanded on them, both as improvising soloist and as composer. . . .his sound bold and full, he brought his own values to three of his original pieces: “Horizons,” with its shifting moods; “Illusions in Blue,” a sort of 21st Century variation on the blues with archly ingenious piano chording and the rich, almost lushly evocative “A Tear and a Smile.” Having thus displayed his dual talents as composer/player, McPherson then felt free to tear into “Cherokee” at a breakneck pace.” Leonard Feather-Los Angeles Times

McPherson Hits Lucky Note With Tape of Live Concert

Los Angeles Times

by DIRK SUTRO

APRIL 2, 1991

Illusions In Blue 1990 – Recorded live in La Jolla California. A limited amount of this re-issue is now available through Chazz Jazz.

(read the full liner notes here)

Sample the title track of “Illusions in Blue”

Doctor of Fine Arts, Charles McPherson

California State University San Marcos awarded an honorary degree, Doctor of Fine Arts, to Charles McPherson during its commencement ceremonies on May 16, 2015. See photos, the diploma, the citation, and the University’s press release >>

Charles McPherson

Charles McPherson was born in Joplin, Missouri and grew up in Detroit . He studied with the renowned pianist Barry Harris and started playing jazz professionally at age 19. He moved from Detroit to New York in 1959 and performed with Charles Mingus from ’60 to ’72, also collaborating frequently with Harris, Lonnie Hillyer (trumpet), and George Coleman (tenor sax). Read more about Charles >>

https://charlesmcpherson.com/bio/

CHARLES MCPHERSON

“Always inventive, Charles McPherson has kept the torch of Charlie Parker burning brightly without being stuck in the past”

About Charles

Click here for the Extended Biography

Click here for a Short Biography

Charles McPherson was born in Joplin, Missouri and moved to Detroit at age nine. After growing up in Detroit, he studied with the renowned pianist Barry Harris and started playing jazz professionally at age 19. He moved from Detroit to New York in 1959 and performed with Charles Mingus from 1960 to 1972. While performing with Mingus, he collaborated frequently with Harris, Lonnie Hillyer (trumpet), and George Coleman (tenor sax).

Mr. McPherson has performed at concerts and festivals with his own variety of groups, consisting of quartets, quintets to full orchestras. Charles was featured at Lincoln Center showcasing his original compositions 15 years ago, and once again joined Wynton Marsalis and J@LC Orchestra in April, 2019 honoring his 80th Birthday where they arranged and performed 7 of Charles’ iconic original compositions. Charles has toured the U.S., Europe, Japan, Africa and South America with his own group, as well as with jazz greats Barry Harris, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton, Nat Adderly, Jay McShann, Phil Woods, Wynton Marsalis, Tom Harrell, Randy Brecker, James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie, and others.

McPherson has recorded as guest artist with Charlie Mingus, Barry Harris, Art Farmer, Kenny Drew, Toshiko Akiyoshi, the Carnegie Hall Jazz Orchestra, and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. He has recorded as a leader on Prestige, Fantasy, Mainstream, Discovery, Xanadu, Arabesque, Capri and several smaller labels in Europe and Japan.

Charles was the featured alto saxophonist in the Clint Eastwood film “Bird,” a biopic about Charlie Parker. Charles has received numerous awards, including the prestigious Don Redman Lifetime Achievement Award and an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from California State University San Marcos. Charles performed this past April at the NEA Jazz Master’s 2019 performance during Stanley Crouch’s tribute. Widely recognized as a prolific composer, Charles is now Resident Composer for the San Diego Ballet, where he has written three original suites for chamber music and jazz combos. In the summer of 2019, Dr. Donnie Norton will compile the entire book of Charles’ compositions for publication.

McPherson remains a strong, viable force on the jazz scene today. Throughout his six decades of being an integral performer of the music, Charles has not merely remained true to his Be Bop origins but has expanded on them. Stanley Crouch says in his New York Times article on Charles, “he is a singular voice who has never sacrificed the fluidity of his melody making and is held in high esteem by musicians both long seasoned and young.” Charles is a frequent guest at universities all over the world and also teaches privately. Many of his former students have gone on to have careers of their own in jazz, and have earned National Jazz Student Awards. Charles had the honor of being the subject of the Ph.D. candidate Dr. Donnie Norton’s Doctoral Dissertation: “The Jazz Saxophone Style of Charles McPherson: An Analysis through Biographical Examination and Solo Transcription.”

Charles McPherson is available internationally for Concerts, Festivals, and Club Dates as a soloist or with The Charles McPherson Group. Charles also offers Clinics and Master Classes.

Click here for the Extended Biography

![]()

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_McPherson_(musician)

Charles McPherson (musician)

Charles McPherson

Charles McPherson (born July 24, 1939)[1] is an American jazz alto saxophonist born in Joplin, Missouri, United States, and raised in Detroit, Michigan, who worked intermittently with Charles Mingus from 1960 to 1974, and as a performer leading his own groups.[1]

McPherson also was commissioned to help record ensemble renditions of pieces from Charlie Parker, on the 1988 soundtrack for the film Bird.[1]

Discography

As leader

- Bebop Revisited! (Prestige, 1965)

- Con Alma! (Prestige, 1965)

- The Quintet/Live! (Prestige, 1967)

- From This Moment On! (Prestige, 1968)

- Horizons (Prestige, 1969)

- McPherson's Mood (Prestige, 1969)

- Charles McPherson (Mainstream, 1971)

- Siku Ya Bibi (Day of the Lady) (Mainstream, 1972)

- Today's Man (Mainstream, 1973)

- Beautiful! (Xanadu, 1975)

- Live in Tokyo (Xanadu, 1976)

- New Horizons (Xanadu, 1978)

- Free Bop! (Xanadu, 1979)

- The Prophet (Discovery, 1983)

- Follow the Bouncing Ball (Discovery, 1989)

- Illusions in Blue (Chazz Jazz, 1990)

- First Flight Out (Arabesque, 1994)

- Come Play With Me (Arabesque, 1995)

- Live at Vartan Jazz (Vartan, 1997)

- Manhattan Nocturne (Arabesque, 1998)[2]

- But Beautiful (Venus, 2004)

- Charles McPherson with Strings (Clarion, 2005)

- The Journey (Capri Records, 2015)

- Jazz Dance Suites (Chazz Mack, 2020)

As sideman

With Barry Harris

- Newer Than New (Riverside, 1961)

- Bull's Eye! (Prestige, 1968)

- Stay Right with It (Milestone, 1978)

- Tokyo 1976 (Xanadu, 1980)

With Charles Mingus

- Mingus (Candid, 1961)

- Mingus at Monterey (Jazz Workshop, 1965)

- Music Written for Monterey 1965 (Jazz Workshop, 1966)

- My Favorite Quintet (Fantasy, 1964)

- Let My Children Hear Music (Columbia, 1972)

- Charles Mingus and Friends in Concert (Columbia, 1973)

- Mingus at Carnegie Hall (Atlantic, 1974)

- The Complete Town Hall Concert (United Artists, 1983)

- The Complete Candid Recordings of Charles Mingus (Mosaic, 1985)

- Shoes of the Fisherman's Wife (Columbia, 1988)

- Charles Mingus Sextet Paris, TNP October 28th 1970 (Ulysse Musique, 1988)

- Live in Chateauvallon, 1972 (France's Concert, 1989)

- Charles Mingus in Paris: The Complete America Session (Sunnyside, 2007)

- Pithycanthropus Erectus (America, 1971)

- Reincarnation of a Lovebird (Prestige, 1974)

- Something Like a Bird (Atlantic, 1980)

With others

- Pepper Adams, Pepper Adams Plays the Compositions of Charlie Mingus (Workshop Jazz, 1964)

- Toshiko Akiyoshi, Just Be Bop (Discomate [Japan], 1980)

- Ray Appleton, Killer Ray Rides Again (Sharp Nine, 1996)

- Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham, Sweet Baby Blues (Concord Jazz, 1985)

- Kenny Drew, For Sure! (Xanadu, 1981)

- Clint Eastwood, Eastwood After Hours: Live at Carnegie Hall (Warner Bros., 1997)

- Art Farmer, The Many Faces of Art Farmer (Scepter, 1964)

- Lionel Hampton, At Newport '78 (Timeless, 1980)

- Eddie Jefferson, Come Along with Me (Prestige, 1969)

- Eddie Jefferson, There I Go Again (Prestige, 1980)

- LaMont Johnson, New York Exile (Masterscores, 1980)

- Bobby Jones, Arrival of Bobby Jones (Cobblestone, 1972)

- Sam Jones, Cello Again (Xanadu, 1976)

- Dave Pike, Bluebird (Timeless, 1989)

- Jimmy Raney, The Complete Jimmy Raney in Tokyo (Xanadu, 1988)

- Red Rodney, Bird Lives! (Muse, 1974)

- Sonny Stitt & Don Patterson, Sonny Stitt/Don Patterson Vol. 2 (Prestige, 1998)

- Charles Tolliver, Impact (Strata-East, 1976)

- Charlie Parker, Bird (CBS, 1988)

- Don Patterson, Boppin' & Burnin' (Prestige, 1968)

- Don Patterson, Funk You! (Prestige, 1968)

- Larry Vuckovich, City Sounds, Village Voices (Palo Alto, 1982)

- Larry Vuckovich, Blues for Red (Hothouse, 1985)

- Dee Dee Bridgewater, Prelude to a Kiss: The Duke Ellington Album (Phillips, 1996)

External links

- Charles McPherson NAMM Oral History Interview (2008)

https://bnatural.nyc/artists/charles-mcpherson/

https://downbeat.com/news/detail/charles-mcpherson-straddles

Charles McPherson Straddles The Artistic Fence

October 13, 2020

Downbeat

Charles McPherson researched what music at the time of King Solomon might have sounded like for the saxophonist’s latest recording, Jazz Dance Suites (Chazz Music). (Photo: Tariq Johnson)

In the course of a career that has found him performing with the likes of Charles Mingus, Dizzy Gillespie and Wynton Marsalis, bebop master Charles McPherson has spent plenty of time on concert stages. Usually, he shares that space with other musicians, but in recent years, the alto saxophonist has found himself performing with dancers from the San Diego Ballet, a collaboration documented on his Jazz Dance Suites (Chazz Music).

“I’m a resident composer with the San Diego ballet,” McPherson said over the phone from his home in the coastal California city. “My daughter is one of the solo dancers with this company; I got involved with the company because of my daughter, and also a grant that was available. So, we partnered up: me, the ballet and the choreographer, Javier Velasco.

“I’ve been with them for a few years now. I’ve written two suites, and we’ve performed them ... ”

“Five, dear. Three suites,” said a woman’s voice in the background.

“Oh, um, three suites,” McPherson said. “OK, here’s Lynn, my wife. She knows more about me than I know myself. You know how that works.”

“I’m sorry to butt in,” she said, taking the phone, “but I hear Charles, and it’s like once he does something, he’s off to the next thing. It’s been a five-year relationship [with the ballet]. Three original suites, and two arrangements.” One of the arrangement projects is called Gershwin Divertissement, and the second focuses on Charlie Parker. “They weren’t able to do [the Parker ballet] yet, but hopefully they’ll do it in October,” she said. “Anyway, that’s the history of the ballet company involvement. Here he is.”

“I should just let her do the interview,” McPherson teases as he gets back on the phone. “I can just play the part of Mr. Magoo, over in the corner.”

Still, his attachment to San Diego always has been because of family, having moved to the West Coast city in 1978 to look after his mother.

“I am an only child,” he said. “My mother was getting older, and I started getting concerned about her living by herself.” He had been in New York, booked to play on the sessions that became Charles Mingus’ Something Like A Bird album. “The very next day after doing that date with Mingus, I moved to California. And not to stay, but I ended up staying.”

Moving from jazz composition to writing for dance was a different kind of leap for McPherson. At first, he was concerned about writing things that would support the dancers’ movements, but Velasco told him not to worry. “He said, ‘You just write. I will do the choreography,’” McPherson recalled. “’You write exactly what you feel, and I’ll do the body stuff with the dancers.’

“Now, writing for dancers is a little bit different,” he added. Although McPherson and his group improvise, the dancers do not, so there need to be audible signposts throughout each work that the dancers can use as cues. “They’re doing the same thing over and over again, and the cues, what they listen for, are telling them what to do with their feet and legs and arms. So, you have to have certain very concrete and very definite things happening in the same places all the time, and yet still have the improvisational aspect of it. You’re straddling the artistic fence a little bit.”

“As a dancer, it’s most artistically fulfilling when you’re moving to something that really speaks to your artistic soul and spirit,” Camille McPherson, the saxophonist’s daughter, said by phone a day later. Having grown up listening to jazz, and particularly to her father’s music, she has a natural and long-nurtured connection to the music. Even so, there are special challenges in dancing to live jazz.

“You have to be really in tune with the musicians, because they’re jazz musicians,” she said. “If you’re playing for dance, especially ballet that’s choreographed, you really have to be consistent. Jazz musicians usually have a ton of freedom, and they don’t have as much freedom when they work with [dancers]. But at the same time, it’s important that we are able to adapt to them, too—just be aware of their energy, their tempos.”

Song Of Songs, perhaps the most unusual piece on Jazz Dance Suites, finds the saxophonist inserting Middle Eastern modalities into the jazz vocabulary. And “Love Dance”—the opening number, based on the Old Testament’s Song Of Solomon—is a story of unrequited love told from a woman’s perspective and features Lorraine Castellanos singing in Hebrew.

“I did a little homework on that,” McPherson said. “I wanted to listen to ancient Hebrew music. You can find that online, if you YouTube it.” He wanted to listen to the music’s scales and tonalities to better understand what music at the time of King Solomon might have sounded like.

“My approach to this particular suite was not to Xerox ancient Hebrew music, but just glean enough nuance,” he said. “I didn’t want to clone it. It’s going to be a hybrid anyway, because I’m going to add the jazz sensitivities.”

Indeed, hearing McPherson’s searing alto work its way through these Hebraic scales adds a sensual frisson to the music that neatly mirrors the sexual desire of the lyrics.

Similarly, having to respect the structural elements of writing for dance led the saxophonist to do things compositionally that wouldn’t normally arise when writing for his quintet. For instance, the dramatic structure of Song Of Songs inspired him to recapitulate material from “Love Dance” in the closing “After The Dance,” to provide an audible connection to the beginning and end of this tragic love story.

“I wouldn’t do that writing just for a regular bebop configuration,” McPherson said. “This is what I mean by ‘thematic writing,’ and being aware of something other than just the notes and chords. It makes me more in touch with the emotional aspect of human beings.” DB

https://charlesmcpherson.com/the-journey/downbeat-magazine-review/

DownBeat Magazine review

Extracted from DownBeat Magazine Editor’s Pick March 2015 by Brian Zimmerman

Alto saxophonist Charles McPherson heard his first Charlie Parker recording in 1953, when he was 14. The song—“Tico Tico”—made a lasting impression. “I knew immediately that this is the way you’re supposed to play,” he recalled. In the decades since, McPherson has become one of the stalwarts of bebop saxophone, and Parker’s influence on him has been widely acknowledged. (In 1988, when Clint Eastwood needed a sax player to evoke the sounds of Parker’s horn in the biopic Bird, the director turned to McPherson.) But if previous albums proved why McPherson was qualified to carry Bird’s mantle, his latest, The Journey, proves why he’s now bop’s brightest star. The technical prowess he brings to bop standards like “Au Privave” and “Spring Is Here” is captivating, and the imagination he exhibits on originals like the title track and “Manhattan Nocturne” shows that the 75-year-old isn’t afraid to push at musical boundaries. Joined by a stellar rhythm section of pianist Chip Stephens, bassist Ken Walker and drummer Todd Reid, McPherson graciously shares the spotlight with Denver-based tenorist Keith Oxman. The reedists craft solos with equal poise, trading bluesy passages on Stephens’ original composition “The Decathexis From Youth (For Cole)” and burning through fast-fingered eighth-note licks on McPherson’s “Bud Like.” Each saxophonist even gets his own solo turn, McPherson on a poignant reading of “I Should Care” and Oxman on his bouncy “Tami’s Tune.” With The Journey, McPherson has put out a prodigious album, a fitting summary of his 60-plus year excursion from apprentice to bebop royalty. One listen is all it takes to know that this is the way you’re supposed to play.

https://ethaniverson.com/interview-with-charles-mcpherson/

DO THE M@TH

Interviews

Interview with Charles McPherson

I’ve had two lessons with Charles McPherson when on tour in San Diego. They have been utterly remarkable. The second one from last fall I taped: Thanks to Charles for allowing this transcription to be published on DTM.

This week Charles is playing at Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola Thursday through Sunday. It is a must-see gig for lovers of the real bebop.

Charles McPherson: Time! I’m talking about metronomic time. I’m not talking about aesthetic time. Just plain academic time. 160 on the metronome is 160. There is no subjectivity and there is no philosophy.

How you feel about 160: that’s dealing with nuance. How are you feeling in between the beat? That is the magic. That’s very, very subtle.

Many people think that how they commit to the metronomic beat is the only game in town. But in bebop, the game in between this beat and the next one is really the main game.

The gap between the beats is the moment of real creativity because once you do this [claps hands], it’s a done deal. The space before is the realm of thinking, possibility and the creative moment!

The real secret to improvising is to be alive in the space and not just alive here [claps hands].

We can look at the brain and you can see what activity is working at the moment. Now to the average player and even the good player too: if you could see brain activity, you’d see all this activity at the downbeats but in between the gaps, it would probably be flatline. There’s nothing going on and then all of a sudden there is activity again.

That ain’t right.

The improviser has to be totally alive throughout the whole spectrum of a bar. Not just a downbeat of a bar, in a micro beat way not just a macro beats.

All the “ups,” “ands” the “a’s.” If you take a whole bar and split it up you have: whole notes, half notes and dotted quarter notes, and quarter notes and eighth notes and sixteenths. Now when you slice them up into all of these little pieces, I say the consciousness of the improvising player should be very much alive on all of these little beats. That means that one should be able to start a phrase on any of that and come out right down the pike.

There’s none of that, “I’m only alive when that next beat comes up…”

If I were to point to you and say “Play now!” you would be playing and you would have something to play.

Ethan Iverson: That reminds me of Charlie Parker. When you transcribe Charlie Parker you see he constantly stops and ends at different places.

CM: He does not care where he stops and most important is he does not care where he starts. That’s what is amazing.

EI: It comes from every corner.

CM: Yeah, he can start from any spot and connect it down the pike. He’s like a drunk man who is on a tight rope. He never falls. The accents make you feel like he could never come out right and he does. All the time. He’ll start anywhere. It would be the “and of 3” in a proceeding bar and make all of the connections seamlessly. He comes out right on chord tones and everything we know for melodic logic to happen.

This is what I mean. He is alive. He is not flatlining anywhere. Now that is some real freedom. That is some serious rhythmic freedom and some serious harmonic freedom and some serious melodic freedom. (That’s the Holy Trinity of Music: melody, harmony, and rhythm.)

The bebop part of it is this: The best of them knew how to navigate through harmonic movement and connect stuff seamlessly. It did not have to be modal or pentatonic.

They could do it with eight notes and they could do it with sixteenth notes.

EI: What about triplets?

CM: Triplets create a rhythmic connection that is good for the eighth notes. It actually creates a certain amount of rhythmic tension. The feeling of three against four is an important feeling. Three and four going on at the same time. When you employ triplets and then play eighth notes right after that; it’s like you shot a bow and arrow.

A player should always have the balance between tension and release in everything. It’s not all tension and not all release, it’s the balance.

In rhythm there is supposed to be a certain amount of stuff that is alluding to tension and release. The balance is there, as opposed to rhythmically it being flat. You want your phrase to sound like it got shot from a bow and arrow. (Not like badminton!)

I’ve got a good way to practice this. You play a whole solo with eighth note triplets and don’t do anything else. At first it is going to be kind of funny to do. To play a triplet every now and then is one thing, but to play 32 bars of eighth note triplets is quite another thing.

You’ll find that in order to do that, every time that you start a new phrase it’s got to be in the world of triplet-ness. You’ll find that your vigil of where the one is and the beat is totally a higher level of vigil then what it is if you say to yourself “I can just play eighth notes to this.” Because you are adhering to triplets and making them a discipline, they draw forth from you a higher level of rhythmic ability.

EI: Barry Harris and Billy Hart both talk about the word “upbeat.”

CM: That means to be alive! Alive through the whole beat. One has to be at home starting phrases on the upbeat and making them come out right. And to have enough of that going on in four bar phrases. If you do that, then that is supplying the tension. If you play something on the upbeat, that is already tense, ’cause you’re doing something that is unexpected and it’s not on a strong side of the beat. Just starting there supplies tension from the get go.

A beat is a complete down and up. It’s the space in between. A lot of people just think a beat is just this [taps hand on table]. Here it’s just flat line. There’s nothing there. Nobody lives there. You can play music that way but it’s not that snake stuff.

Even most jazz players don’t really live in the space more than the [taps hand on table]. We can talk about race; white and black. There is only a handful of players, black, white, Chinese, Man, Woman, green, yellow, purple that can really navigate like that.

So you have Elvin Jones and you got a young professional drummer. There’s a difference. They both play drums and they are both playing four-four. The way that Elvin Jones is going to navigate these accents is totally different from the young professional. Young professional is gonna play it in a straight line. Which is good. That’s OK cause its gonna get you there.

But Elvin is playing like Michael Jordan going down the court. Now you can get down the court in a straight line, or you can go down the court like Michael Jordan which means he is pivoting all over the place in unexpected spots and faking people out. They thought he was doing this, and he pivoted and did that. They are all over there on the floor and he is over here making the basket.

We can equate Michael Jordan’s pivots with the accents of a drummer. Elvin Jones is Michael Jordan. It’s not a race thing, it’s a rhythm thing. There’s only a handful of people who feel time like that. When you got that, it’s kind of like listening to Tito Puente.

EI: Does the word “Clave” relate to bebop?

CM: I must admit that I don’t know enough about that music as I should. A lot of jazz people — including drummers — don’t know enough about that stuff. There’s a difference between 2-3 and 3-2 clave. When you play a gig with those cats and you mix that up, they will let you know right away.

I think most jazz is a particular version of the clave. I’m not sure which one. A lot of the heads, one of those works more than the other.

The thing about jazz and the way a drummer functions in a jazz rhythm section; the way he is parlaying accents and distributing them between his limbs is similar to a timbale player. Instead of having one trap drummer, they have several drummers taking care of certain things. Bongos are doing this, the congas are doing something else…The trap drummer is a new invention and he is performing the function of several people.

EI: Charlie Parker could play with Mario Bauza because his rhythmic perception fit in with that situation.

CM: Rhythmically what Charlie Parker did fits with anything. His syncopation and how he is thinking about tension and release works perfectly with that kind of music.

People play differently. Some hear things more in a straight line. Charlie Parker represents the more serpentine approach. Miles Davis, as great he is, sometimes is more straight.

There’s a good example with two different tunes. Miles Davis is the one who wrote “Donna Lee,” based off the changes of “Indiana.” It’s still a great tune, but it is not quite the same thing that Bird and Dizzy had at that time, it is a little more straight.

[Sings the melody to “Donna Lee.”]

It’s a long line of eighth notes.

OK, look at Charlie Parker’s tune. Any one of them …

[Sings “Moose the Mooche” and emphasizes the accents and the syncopation.]

Look at that…That’s Michael Jordan.

This ain’t Michael Jordan. It’s beautiful but not Jordan: [Sings “Donna Lee.”]

This is: [Sings a montuno.]

In Afro Cuban everything they are doing is that. The bass players are on the “and” of 2 and the downbeat of four. They are never on one. It sounds like they are in seven and it’s just 2/4!

You listen to them and you say “Man what is that?” and they say, “Oh it’s just 6/8, 2/4 or 4/4.” It’s because where they are choosing to accent.

[Sings Charlie Parker blues “Bird Feathers.”]

If I did not put a melody to that and just played the rhythm to it, I’d sound like a great drummer.

You see when Bird wants to play with the Afro Cuban cats….Bird was already that.

He did not have to change anything. Can you imagine Miles playing with an Afro Cuban group?

EI: I guess Sonny Rollins was the guy.

CM: He was the closest. He was next. I don’t even know if Coltrane was quite like that. Trane’s actually straighter. He was wonderful but he did not quite have the corners. If he had the corners that Sonny Rollins had in 1957 and Sonny Rollins had the harmony that Trane had…that’s the way you’d beat both of them.

Could you imagine playing “Countdown” the way Sonny Rollins would have played “Countdown?” [Laughter] That’s a whole different kind of “Countdown.”

EI: Lester Young comes to mind: how did he link to Bird?

CM: Lester Young is the first Bird. No Lester Young, no Bird.

And Buster Smith. I have heard Billy Eckstine say that Bird was such an amalgamation of so many players that you can’t pick any of them out. It’s mixed up in there and he has his own thing and it came out the way it did. The most notable stuff would be Lester Young and Buster Smith. I heard Buster on a record and Bird really got a lot of stuff from him. That one record that documents him, he was already an old man, but you can hear how Bird comes from that From what I heard there’s also Chu Berry and Coleman Hawkins and a lot of other people. Including Louis Armstrong. It’s all mishmashed and there Bird is.

EI: It seems to me Louis Armstrong has that “Michael Jordan” stuff.

CM: Yeah, he did. He just did not play as many notes as Charlie Parker but the accents are falling like that. Also there is the real gift of melody.

When a player plays, you have several choices within the chord. There are a few notes that are right and you have these choices but to eke out the best three or four, sequence-wise; that is what gift of melody is. There’s a difference between the right notes and the best notes. The best notes also have something to do with “when.” ‘Cause a note is a note. A D natural is D natural… but it being here as opposed to there and how it is phrased and the rhythm of it, makes all of the difference.

EI: You told me something last time about how the changes are there but you don’t play the changes.

CM: Yes! You’re supposed to be thinking melodically. It’s not like the changes are giving you anything. It’s the melody notes that you hear out of them. You can’t be backwards with that.

Thirds are always melodic. In a way they are the most melodic interval. Thirds are the beginning of creation. Scales are just there, but thirds are melodic and harmonic.

If you navigate in thirds, getting to chord tones by threading thirds in a million different combinations, you will always be melodic, not just playing scales. For a beginning jazz student, I might have them play a whole solo in thirds. It will stop them from being too scalar.

[I sit at the piano for 20 minutes and play along with Jamey Aebersold tracks of “All the Things You Are” and “The Song is You.” Charles coaches me on adding triplets to my line, playing the accents harder, laying back more on the beat.]

[We sit back down on the couch.]

CM: Think of the quarter notes not as marching but as ice-skating. Elvin Jones said, “I don’t think of 4/4, I think of 8/8…and the person who told me to think that way was Charlie Parker.” Elvin told that to my son.

If you are subdividing, your beat is wider. Also those subdivided beats become sentences you skate through, not just four beats goose-stepping in a march.

Another metaphor: You want it to be tai-chi, not karate.

Even if it is fast, the real bebop players skate through it all.

There’s variety in everything. Another thing you could practice is changing your touch at the piano depending on the kind of phrase you are playing. It’s not “one size fits all.”

In the end, of course, it becomes organic. You forget about all the practice when you actually play a gig.

EI: The word “asymmetrical” might be important.

CM: Yes! Symmetry is boring. Or, at least, “asymmetry” is the creative aspect of if. Some people can really snake, can really be serpentine.

Some great players are really great but don’t have that snake. Barry Harris has it.

EI: Cedar Walton is a great bebop pianist but it’s not that asymmetrical.

CM: Right. I love Cedar but he’s not Barry or Bud Powell when it comes to that.

EI: Tommy Flanagan?

CM: Tommy is so creative! Maybe even more creative than Barry. But he’s a little on top with the beat. Barry is more right in the center.

The other guy who really has the beat from Barry’s generation is Sonny Clark. They are really rare in a way, digging into the time like that.

EI: Red Garland?

CM: Yeah, but Red —and Wynton Kelly too…and Bill Evans too— they have a real dotted-quarter and sixteenth kind of swing. Not when it gets real fast of course, but at medium tempos there’s that kind of hiccup in the line. Barry, Sonny Clark, Bud, Bird, Sonny Rollins, Trane: they play more like even eighth notes, and that’s how I want to play too.

[Picks up his horn and demonstrates an exaggerated swing like Red and a smother eighth like Barry.]

EI: I guess if you are playing a more straight eighth note it can grind in a nice way against the implied triplet.

CM: Especially for horn players, if you accent the upbeat note too much in the line, it can shorten the second eight note into a sixteenth.

EI: Joshua Redman told me something like that, that at lessons with beginning saxophonists he usually had to tell them to stop trying to swing the second eighth too much, that it was too herky-jerky.

CM: Exactly. I want to play more evenly, although still with the accents and placement of course.

One way to practice getting asymmetrical is connecting the melody notes of a standard in surprising ways. Make yourself get from there to here with creative inspiration. From any part of the original melody, go! until the next part of the melody. The highest example of that is Charlie Parker with Strings. They just released some more alternate takes and it is just unbelievable, his melodic inspiration. It doesn’t matter where he is in the melody, he joins things together in new ways. That’s art!

[I didn’t think what Charles was talking about was all that hard, but when he asked me to do it on “All the Things You Are” and “The Song is You,” I found it essentially impossible. This concept is now a regular part of my practice. John Coltrane also really has this together: Listen to Trane’s melody statement on any slow or medium tempo standard.]

EI: What about playing on modal music?

CM: With the modal concept you don’t need to change anything. In fact, this is where rhythm really comes in. If you can play a lot of syncopations, you will have a real advantage over a modal player who doesn’t know that stuff. Same with playing thirds instead of scales.

After all, John Coltrane really digested bebop before he played modal. In fact, we forget that he was only six years younger than Charlie Parker. He was like a younger brother, seeing all that stuff live. There’s even that photo of him looking at Bird.

Barry Harris doesn’t like modal music, but that doesn’t mean he couldn’t do it. If he wanted to, he certainly could.

EI: Ok, last question: What about the blues?

CM: The real vibe of the blues — a slow blues, not an uptempo blues — is a state of reverence. The Greeks had different words for different kinds of love. “Eros” is sexual love. “Agape” is more how you feel about God.

In the blues, even though there’s plenty of suggestive lyrics, the feeling underneath is more Agape. There’s a longing towards God. You have to be in that kind of space to play the blues well.

—

UPDATE: A year later: I took another lesson.

Charles talked to me about patterns a bit. According to Charles, Charlie Parker didn’t play patterns, but Dizzy Gillespie did, simply because when exploring in a fashion that makes complex harmony the base, patterns are a logical way to elaborate the harmony. Charles said that Dizzy Gillespie had a copy of Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns in the 1940s. (It was published in 1947, but most of us think of it entering the jazz practice room with John Coltrane’s recommendation a decade later).

Charles mentioned “Lover” as a good place to hear how Bird avoided patterns. The harmony is all parallel, but Bird never plays sequences. This is not true (at least not in the same way) when Coltrane plays “Lover.” Tellingly, Bird starts with a major chord, Trane starts with a II/V.

I wanted to hear Charles on “Lover,” and he stomped it off at Coltrane’s fierce tempo but with a melodic purity that is closer to Bird. Lynn McPherson caught the moment on video.

https://www.detroitjazzfest.org/artist/charles-mcpherson/

Charles McPherson

https://indianapublicmedia.org/nightlights/charles-mcphersons-postbird-bop.php

Charles McPherson's Post-Bird Bop

by David Johnson

November 11, 2020

Charles McPherson is an alto saxophonist who spent much of his early career under the spell of jazz great Charlie Parker,but who fired the Parker sound with his own intense energy and expressive skills. Championed by jazz writer Ira Gitler, McPherson made a number of records for Prestige throughout the mid-to-late 1960s, garnering generally good reviews and gaining notice in a 1967 Downbeat critics‘ poll as "talent most deserving of wider recognition." But it was the era of the avant-garde, Miles Davis‘ second great quintet, and the emerging influence of rock. McPherson‘s bebop-steeped sound struck some as antiquated.

In a 1968 interview with Chris Albertson, McPherson criticized his contemporaries, who 'segregated' themselves from certain kinds of music. "I don‘t understand how cats can be my age and have missed Bird," he said. "For instance, if a cat is studying psychology, he‘s just got to read something about Freud. A musician must go way back and listen to all of it, all kinds of music..not just jazz. All the great cats did that; they knew no musical boundaries, they knew they couldn‘t afford to be prejudiced." Citing his habit of listening to everything from Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith to Stravinsky and Bach, McPherson said, "I learn from all of those cats, they all express beauty. There are still some of us who really dig love and beauty."

Watch a recent interview with Charles McPherson:

Charles McPherson Interviews Parts 1-4 | "San Diego Profiles"

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/charles-mcpherson

Charles McPherson

Musicians | Instrument: Saxophone, alto | Location: San Diego

Updated: December 22, 2020

Born: July 24, 1939

For more than 60 years, saxophonist Charles McPherson has been one of the most expressive and highly regarded voices in jazz. His rich musical style, rooted in the blues and bebop, has influenced and inspired generations of musicians and listeners.

McPherson was born in Joplin, MO, on July 24, 1939, and he developed a love for music at a young age. As a child, he began experimenting at the piano whenever one was available. He also attended summer concerts in Joplin that featured territory bands from the Midwest and Southwest. These concerts made a strong impression on McPherson, who was particularly enamored with the sound and shape of the saxophone.

McPherson moved to Detroit in 1948 at age 9. At that time, Detroit was home to one of the most vibrant jazz communities in the country. His new home was in the same neighborhood as his future mentor, pianist Barry Harris, as well as his friend and future bandmate, trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer. Additionally, McPherson now lived within blocks of the famed Blue Bird Inn jazz club.

“The street that I lived on just happened to be a street where Barry Harris lived right around the corner, five minutes away. A trumpet player named Lonnie Hillyer, who worked with Mingus along with myself for a long time, lived right on my street. And there was a jazz club a few blocks down on my street called the Blue Bird, which was, at that time, probably the hippest jazz club in Detroit. So it was interesting that, of all places, as big as Detroit is, I ended up on the same street as a really great local jazz club. The house band at that time was Barry Harris on piano, Pepper Adams playing baritone sax, Paul Chambers or Beans Richardson (on bass), and Elvin Jones was the house drummer.”

NYC Aug1962 After beginning on flugelhorn and trumpet in his school band at age 12, McPherson switched to alto saxophone at 13. Much of his knowledge of jazz at that point was from an awareness of popular big bands of the Swing Era. He was also familiar with great soloists from that time, such as alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges. Based on the recommendation of a classmate, McPherson first heard the music of Charlie Parker in his early teens. Despite not having a strong theoretical knowledge of this new music, he knew immediately that bebop was the style he wanted to play.

“One day I was in a little candy store, and there was a jukebox with records in it, and I saw Charlie Parker. And I was like ‘Oh! Let me put my money in and hear this guy!’ And when I heard that (“Tico-Tico” from Charlie Parker South of the Border), I was completely floored. I was 13 or 14 years old, and from that point on, it was like ‘that’s it.’ And I knew nothing about changes or chords, and I’m just a kid. I knew immediately that this is the way you’re supposed to play.”

From then on, McPherson immersed himself in the jazz culture of Detroit, modeling his musical style and training after the great musicians in his midst. At age 15, he began to study with Barry Harris, in addition to briefly studying saxophone at the Larry Teal School of Music in Detroit. McPherson also started to practice and perform with other future jazz luminaries within his peer group, including Hillyer, Roy Brooks, Donald Walden, and Louis Hayes, as well as future Motown legends and members of the Motown house rhythm section, bassist James Jamerson and drummer Richard “Pistol” Allen.

“What we had to do was pool our money together…and we rented a loft. We had seven or eight keys, and at any time of night, anybody could go in and play. There was a drum set there and a piano there…and it was in a neighborhood that was a business district where, after hours, nobody was there. So we could go in at 2 o’clock in the morning and have a session. And this is what we had to do in order to play, because (otherwise) we couldn’t play with those (older) cats.”

By age 19, McPherson had advanced to the point where he was working regularly throughout Detroit. He soon joined a number of his contemporaries in moving from Detroit to New York in the late 1950s. After moving to New York in 1959, McPherson began his association with Charles Mingus, which lasted for the next 12 years.

In the mid-1960s, McPherson began to record more frequently with other musicians, including Harris and trumpeter Art Farmer. McPherson’s first recording as a leader, Bebop Revisited, was made in 1964 and featured Carmell Jones on trumpet, Barry Harris on piano, Nelson Boyd on bass, and Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums. Later in the decade, McPherson starting working more with his own groups, which also included Harris, as well as tenor saxophonist George Coleman, who had recently finished his tenure as a member of Miles Davis’s band.

By 1972, McPherson stopped playing with Mingus and continued to tour and record as a leader and as a sideman. He moved to San Diego in 1978, and since then he has maintained an active career as a performer and educator throughout the United States and abroad. In 1988, McPherson was featured in the soundtrack to the Clint Eastwood film Bird as the saxophone voice of Charlie Parker in several scenes. He has performed on over 70 recordings to date, both as a leader and as a sideman. One of his most recent recordings, Love Walked In, featuring Bruce Barth on piano, Jeremy Brown on bass, and Stephen Keogh on drums was released in February 2016. Additionally, in 2017, McPherson was interviewed for the upcoming documentary Artists of Jazz, featuring other legendary jazz musicians “whose careers played an integral part in the history of jazz.” In September 2020, his newest recording, Charles McPherson's Jazz Dance Suites will be released under his own label, ChazzMackMusic. A culmination of 5 years of commissioned work with the San Diego Ballet, it includes two full original suites: "Song of Songs" and "Sweet Synergy Suite", plus more. Recorded at Van Gelder Studio with Terell Stafford - trumpet, Randy Porter and Jeb Patton - piano, Lorraine Castellanos - voice, Billy Drummond - drums, Yotam Silberstein - guitar, and David Wong - bass. BebopSpokenHere (UK) says, "I doubt there will be a better album released this year.."

McPherson has toured throughout the United States, Europe, Africa, South America, and Japan. In addition to the artists mentioned above, McPherson has performed and/or recorded with many other jazz greats, including Pepper Adams, Nat Adderley, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Randy Brecker, Jaki Byard, the Carnegie Hall Jazz Band, Ron Carter, Paul Chambers, Alan Dawson, Kenny Dorham, Kenny Drew, Billy Eckstine, Tommy Flanagan, Lionel Hampton, Tom Harrell, Billy Higgins, Sam Jones, Clifford Jordan, Duke Jordan, Brian Lynch, Wynton Marsalis, and twice with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, Pat Martino, Cecil McBee, Jay McShann, Mulgrew Miller, James Moody, Dannie Richmond, Red Rodney, Cedar Walton, Phil Woods, Snooky Young, and many others.

McPherson is also an active composer. His most recent large-scale works, Sweet Synergy Suite, Song of Songs, Reflection Turmoil & Hope, plus two medleys, are the product of a grant from the San Diego Foundation’s Creative Catalyst Fund, and private donors. The works have created a new series for San Diego Ballet with ballet and modern dance styles, featuring music by McPherson and choreography by Javier Velasco. McPherson was named Resident Composer for the San Diego Ballet. In this position, he will continue to collaborate with Velasco in creating innovative new works for the company.

In addition to being a performer and composer, McPherson is a respected and in-demand educator. In 2014, he was a guest coach with the Juilliard Jazz Artist Diploma Ensemble. He has been a clinician at countless other high schools, colleges, and universities in the United States and throughout the world, including the Amsterdam Conservatory, California State University at Bakersfield, California State University at Northridge, California State University at San Marcos, The Hartt School at the University of Hartford, New Jersey State University, the New School, Northern Illinois University, the Royal Academy of Music (London), San Diego State University, Stanford University, SUNY Purchase, Temple University, the Thelonious Monk Institute at UCLA, the University of California at San Diego, the University of North Texas, the University of Northern Colorado, and the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music.

In May 2015, McPherson was awarded an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from California State University at San Marcos for “his outstanding professional and creative accomplishments and his influential role in mentoring future generations of musical artists.” In June 2016, he was joined by drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath in receiving the Don Redman Jazz Heritage Award, which is given annually to “legends of jazz whose musicianship, humanity and dignity serve as an asset to jazz in the tradition of Don Redman, and whose work in music and education illuminates his spirit.” In 2017, McPherson was the recipient of “The Duke” Award from Soka University, recognizing his lifetime of achieving “longstanding artistic excellence, the victory of musical power and beauty fostered with the tenacity of intelligent endurance.” After a Jazz at Lincoln Center tribute featuring Charles' 80 birthday in 2019, Wynton Marsalis says of Charles, "Charles is the very definition of excellence in our music. He’s the definitive master on his instrument. He plays with exceptional harmonic accuracy and sophistication. He performs free-flowing, melodic, and thematically developed solos with unbelievable fire and an unparalleled depth of soul.”

McPherson currently lives in San Diego with his wife, Lynn, and he maintains an active schedule of performing, recording, composing, and teaching. He remains a respected and powerful force in jazz, and he is still “very much in love with the saxophone and music.”

Source: Donnie Norton

REVIEW: Charles McPherson “Jazz Dance Suites” – London Jazz News

by Frank Griffith

Alto saxophonist Charles McPherson‘s distinctive musical personality is rooted in bebop, bluesiness with a bouncy and vibrant gait. It slithers and weaves – making it an effective complement for dance. Jazz Dance Suites was inspired by and dedicated to his daughter, Camille, a soloist in the San Diego Ballet. Two works – Song of Songs and Sweet Synergy Suite – comprise most of the album which also includes a six-minute piece entitled Reflection on an Election which is a response to the 2016 American election. Read this full review here.

http://www.rabbitmoonproductions.com/events/2015/10/22/charles-mcpherson-quartet

Shows at 7:30pm & 9:30pm nightly.

More than a half–century into his professional career, alto saxophonist Charles McPherson remains a potent creative voice in jazz. McPherson logged an epic twelve–year run with the Charles Mingus group (1960–1972) and has released some 25 albums as a leader including Live at the Five Spot (Prestige, 1966) and First Flight Out(Arabesque, 1994). In 1988, McPherson was the featured alto player on the soundtrack of Clint Eastwood’s filmBird. Reviewing his 2015 CD The Journey for AllAboutJazz.com, Robert Bush wrote: “Alto saxophone legend Charles McPherson has few living peers, but even at the age of 75, he shows no signs of slowing down…Blistering post–bop remains McPherson’s signature, but there is also a modernist streak that ripples through his improvising on this disc that can only be heard in terms of things that tingle the spine.”

Charles McPherson – alto saxophone

Brian Lynch – trumpet

Jeb Patton – piano

Ray Drummond – bass

Billy Drummond – drums

Charles McPherson

Saxophone – Jazz Institute, Advanced Package

He also happens to be one of the world’s great educators, connecting deeply with students at SJW over the years, and providing a tremendous inspiration for their musical development, and a positive influence in their lives in general.

Connecting with Charles is one of the best things you can do for your own growth as a musician, and we invite you to do so this summer at Jazz Institute!

Charles was born in Joplin, Missouri but grew up in Detroit, Michigan, where he studied with the renowned pianist Barry Harris and started playing jazz professionally at age 19. He moved from Detroit to New York in 1959 and performed with Charles Mingus from 1960 to 1972. While performing with Mingus, he collaborated frequently with Harris, trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer, and tenor saxophonist George Coleman.

Charles has performed at concerts and festivals with his own variety of groups, consisting of quartets, quintets to full orchestras. He has toured the U.S., Europe, Japan, Africa and South America with his own group, as well as with jazz greats Barry Harris, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton, Nat Adderly, Jay McShann, Phil Woods, Wynton Marsalis, Tom Harrell, Randy Brecker, James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie, and others.

He has recorded as guest artist with Charlie Mingus, Barry Harris, Art Farmer, Kenny Drew, Toshiko Akiyoshi, the Carnegie Hall Jazz Orchestra, and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. He has recorded as leader on Prestige, Fantasy, Mainstream, Discovery, Xanadu, and most recently Arabesque. Charles was also the featured alto saxophonist in the Clint Eastwood film “Bird,” a biography about Charlie Parker.

Charles remains a strong, viable force on the jazz scene today. He is at the height of his powers. His playing combines passionate feeling with intricate patterns of improvisation. Throughout his five decades of being an integral performer of the music, Charles has not merely remained true to his bebop origins, but has expanded on them. Stanley Crouch says in his New York Times article on Charles, “He is a singular voice who has never sacrificed the fluidity of his melody making and is held in high esteem by musicians both long seasoned and young.”

THE

MUSIC OF CHARLES MCPHERSON: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF

RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS

WITH CHARLES MCPHERSON

Song of the Sphinx - Charles McPherson

Charles McPherson Beautiful