SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BAIKIDA CARROLL

(September 3-9)

BILLY DRUMMOND

(September 10-16)

BOBBY MCFERRIN

(September 17-23)

ALBERT KING

(September 24-30)

ZENOBIA POWELL PERRY

(October 1-7)

DEAN DIXON

(October 8-14)

DOROTHY DONEGAN

(October 15-21)

BOBBY BLUE BLAND

(October 22-28)

CLORA BRYANT

(October 29-November 4)

CARLOS SIMON

(November 5-11)

VALERIE CAPERS

(November 12-18)

ROLAND HAYES

(November 19-25)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bobby-mcferrin-mn0000768367/biography

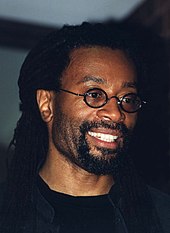

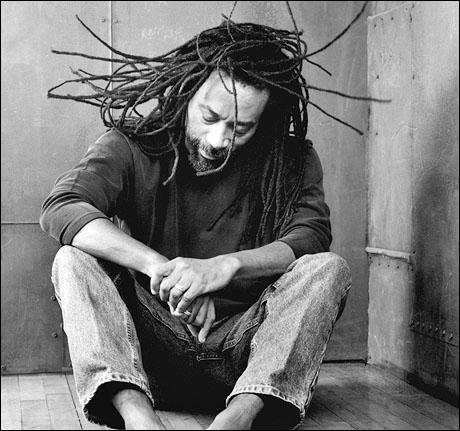

Bobby McFerrin

(b. March 11, 1950)

Biography by Jason Ankeny

Vocal virtuoso Bobby McFerrin ranks among the most distinctive and original singers in contemporary music -- equally adept in jazz, pop, and classical settings, his octave-jumping trademark style, with its rhythmic inhalations and stop-on-a-dime shifts from falsetto to deep bass notes often sounds like the work of at least two or three singers at once, while at the same time sounding quite unlike anyone else. The son of husband-and-wife classical singers, McFerrin was born in New York City on March 14, 1950, later studying piano at California State College at Sacramento and Cerritos College. After touring behind the Ice Follies, he performed with a series of cover bands, cabaret acts, and dance troupes before making his vocal debut in 1977. While living in New Orleans, he sang with the group Astral Projection before relocating to San Francisco. There he met legendary comedian Bill Cosby, who arranged for McFerrin to appear at the 1980 Playboy Jazz Festival.

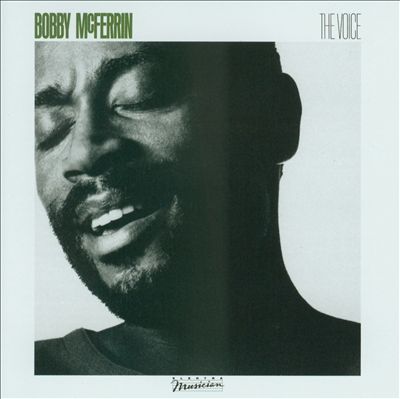

A performance at the 1981 Kool Jazz Festival led to a contract with Elektra, and the following year, McFerrin issued his self-titled debut LP. With 1984's The Voice, he made jazz history, recording the first-ever solo vocal album (sans accompaniment or overdubbing) to be released on a major label. His Blue Note debut, Spontaneous Inventions, followed in 1985 and featured contributions from Herbie Hancock, the Manhattan Transfer (on the Grammy-winning "Another Night in Tunisia"), and comic Robin Williams; McFerrin also earned mainstream exposure through his unique performance of the theme song to the television hit The Cosby Show, as well as a number of commercial spots. With 1988's Simple Pleasures, he scored a chart-topping pop smash with "Don't Worry, Be Happy"; around that time, he also formed the ten-member a cappella group Voicestra, featured on 1990's Medicine Music.

With 1992's Hush, McFerrin shifted gears to team with acclaimed cellist Yo-Yo Ma; the record remained on the Billboard Classical Crossover charts for over two years. The jazz release Play, a collaboration with pianist Chick Corea, appeared in 1992 as well. McFerrin returned to classical territory in 1995 with Paper Music, a collection of interpretations of works by Mozart, Bach, and Tchaikovsky recorded with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, (which he joined as Creative Chair a year prior). For 1996's Bang! Zoom he teamed with members of the Yellowjackets; a second collaboration with Corea, The Mozart Sessions, appeared later that same year. With 1997's Circlesongs, McFerrin returned to his roots, recording an entire album of improvised vocal performances. He then recorded a collaborative album of classical and jazz standards for Sony Music Special Products in 2001. It teamed him with such esteemed musicians as Herbie Hancock, Yo-Yo Ma, and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. A year later, Blue Note released his Beyond Words album, McFerrin's first work for the label in nearly a decade. It featured a band comprised of Chick Corea, Richard Bona, Omar Hakim, Cyro Baptista, and Gil Goldstein. Supported by a choir, McFerrin released VOCAbuLarieS in 2010. Spirityouall, released in the spring of 2013, was a tribute to McFerrin's father, Robert McFerrin, whose 1957 album Deep River brought Black spirituals into the world of high art.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/bobby-mcferrin

Bobby McFerrin

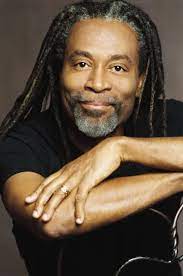

Bobby McFerrin is one of the natural wonders of the music world. A ten-time Grammy Award winner, he is one of the world's best-known vocal innovators and improvisers, a world-renowned classical conductor, the creator of "Don't Worry Be Happy", one of the most popular songs of the late 20th century, and a passionate spokesman for music education. His recordings have sold over 20 million copies, and his collaborations including those with with Yo-Yo Ma, Chick Corea, the Vienna Philharmonic, and Herbie Hancock have established him as an ambassador of both the classical and jazz worlds.

With a four-octave range and a vast array of vocal techniques, McFerrin is no mere singer; he is music's last true Renaissance man, a vocal explorer who has combined jazz, folk and a multitude of world music influences - choral, a cappella, and classical music - with his own ingredients. As a conductor, Bobby is able to convey his innate musicality in an entirely different context. He has worked with such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Vienna Philharmonic.

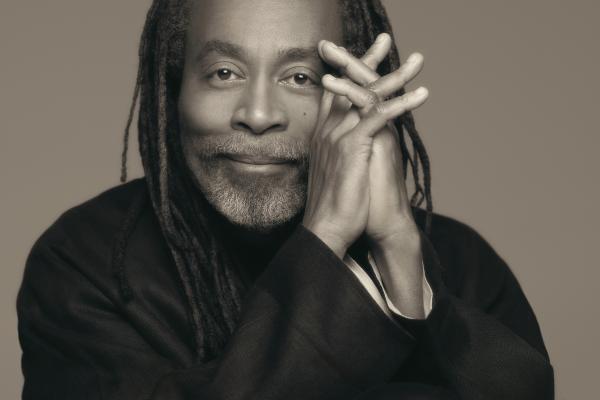

Bobby McFerrin

New York, New York

Photo by Carol Friedman

Bio

“My pursuit of music has always been about freedom and joy, finding inspiration in the folk traditions of every continent, composed music like Bach or Ives or James Brown or Bernstein, plus every sound I’ve ever heard or imagined. In the collective improvisations of jazz, to participate fully, each player brings their universe of influences, so we can listen, lead, and respond to each other in an ever-continuing real-time adventure. And, on top of all that, we actually get to play and to make up stuff for a living too! Thank you NEA for inviting me to be recognized with this honor, among so many of my dearest friends, influencers, fellow players, and some of the most imaginative beings on the planet.”

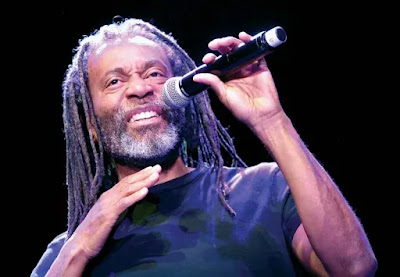

Bobby McFerrin is a master of vocal improvisation, using his four-octave range in various techniques, from scat singing to polyphonic overtone singing to vocal percussion, working both unaccompanied and with instruments. Oftentimes he will sound like an entire band all by himself, sometimes using his own body as a percussion instrument. A ten-time Grammy Award winner, McFerrin has moved comfortably among genres, and has won awards in both jazz and classical.

McFerrin’s influences started with his father, who was the first African-American male to play leading roles at the Metropolitan Opera (he sang the part of Porgy (portrayed by Sidney Poitier) in the 1959 film version of Porgy and Bess) and his mother, also a professional singer and teacher. Hearing a variety of music growing up, McFerrin began playing first the clarinet, then the piano, forming a high school jazz band and continuing to play piano in college. At 27, he realized his true calling was singing, and spent the next six years developing his style, with a performance at the 1981 Kool Jazz Festival leading to a contract with Elektra Records. His recordings for the label include The Voice (1984), considered the first solo vocal jazz album recorded for a major label with no accompaniment or overdubbing.

In 1988, McFerrin had a big hit with "Don't Worry, Be Happy," from his album Simple Pleasures. Although the song became an enduring global sensation (the first a cappella song ever to reach top 40 in America), McFerrin moved in a different direction, creating a ten-person a cappella group Voicestra and working with various artists in the classical and jazz fields, including Yo-Yo Ma, Chick Corea, and the Yellowjackets. He has also explored world music, such as on his 1997 release Circlesongs, which comprised spontaneous vocal improvisations on African and Middle Eastern themes.

In yet another turn in his career, McFerrin took up conducting in 1990 (on his 40th birthday) with the San Francisco Symphony after taking lessons from Seiji Ozawa and Gustav Meyer. “The conducting came up only because I was very curious about the art of it,” McFerrin noted. Since, he has guest conducted symphony orchestras worldwide, and from 1994 to 1998 was creative director of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. During his time with the orchestra, he developed the educational program CONNECT (Chamber Orchestra’s Neighborhood Network of Education, Curriculum and Teachers), which provides supplementary music education free-of-charge to local public schools, reaching as many as 5,000 students annually.

In 2009, he and musician, scientist, and author Daniel Levitin co-hosted The Music Instinct: Science & Song, an award-winning PBS documentary based on Levitin's bestselling book This Is Your Brain on Music that looks at how the brain reacts to music performed in a variety of ways. McFerrin continues to perform and tour internationally and participate in music education programs, making volunteer appearances as a guest music teacher and lecturer at public schools throughout the United States.

Selected Discography

The Voice, Elektra, 1984

Spontaneous Invention, Blue Note, 1986

Beyond Words, Blue Note, 2002

VOCAbuLariesS, Emarcy, 2010

Spirityouall, Masterworks, 2013

Related Video:

NEA Jazz Masters: Bobby McFerrin (2020)

August 20, 2020

Bobby McFerrin

Robert Keith McFerrin Jr. (born March 11, 1950)[1] is an American folk and jazz artist. He is known for his vocal techniques, such as singing fluidly but with quick and considerable jumps in pitch—for example, sustaining a melody while also rapidly alternating with arpeggios and harmonies—as well as scat singing, polyphonic overtone singing, and improvisational vocal percussion. He is widely known for performing and recording regularly as an unaccompanied solo vocal artist. He has frequently collaborated with other artists from both the jazz and classical scenes.[2]

McFerrin's song "Don't Worry, Be Happy" was a No. 1 U.S. pop hit in 1988 and won Song of the Year and Record of the Year honors at the 1989 Grammy Awards. McFerrin has also worked in collaboration with instrumentalists, including the pianists Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, and Joe Zawinul, the drummer Tony Williams, and the cellist Yo-Yo Ma.[2]

Early life and education

McFerrin was born in Manhattan, New York City, United States, the son of operatic baritone Robert McFerrin and singer Sara Copper. He attended Cathedral High School in Los Angeles,[3] Cerritos College,[4] University of Illinois Springfield (then known as Sangamon State University)[5] and California State University, Sacramento.[3]

Career

McFerrin's first recorded work, the self-titled album Bobby McFerrin, was not produced until 1982, when McFerrin was already 31 years old. Before that, he had spent six years developing his musical style, the first two years of which he attempted not to listen to other singers at all, in order to avoid sounding like them. He was influenced by Keith Jarrett, who had achieved great success with a series of solo improvised piano concerts including The Köln Concert of 1975, and wanted to attempt something similar vocally.[6]

In 1984, McFerrin performed onstage at the Playboy Jazz Festival in Los Angeles as a sixth member of Herbie Hancock's VSOP II, sharing horn trio parts with the Marsalis brothers.

In 1986, McFerrin was the voice of Santa Bear in Santa Bear's First Christmas, and in 1987 he was the voice of Santa Bear/Bully Bear in the sequel Santa Bear's High Flying Adventure. On September 24 of that same year, he performed the theme song for the opening credits of Season 4 of The Cosby Show.

In 1988, McFerrin recorded the song "Don't Worry, Be Happy", which became a hit and brought him widespread recognition across the world. The song's success "ended McFerrin's musical life as he had known it," and he began to pursue other musical possibilities on stage and in recording studios.[7] The song was used as the official campaign song for George H. W. Bush in the 1988 U.S. presidential election, without Bobby McFerrin's permission or endorsement. In reaction, Bobby McFerrin publicly protested that use of his song, and stated that he was going to vote against Bush. He also dropped the song from his own performance repertoire.[8]

At that time, he performed on the PBS TV special Sing Out America! with Judy Collins. McFerrin sang a Wizard of Oz medley during that television special.

In 1989, he composed and performed the music for the Pixar short film Knick Knack. The rough cut to which McFerrin recorded his vocals had the words "blah blah blah" in place of the end credits (meant to indicate that he should improvise). McFerrin spontaneously decided to sing "blah blah blah" as lyrics, and the final version of the short film includes these lyrics during the end credits. Also in 1989, he formed a ten-person "Voicestra" which he featured on both his 1990 album Medicine Music and in the score to the 1989 Oscar-winning documentary Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt.

Around 1992, an urban legend began that McFerrin had committed suicide; it has been speculated that the false story spread because people enjoyed the irony of a man known for the positive message of "Don't Worry, Be Happy" suffering from depression in real life. But in reality Mcferrin knew the song help spread the message of positivity to the world abroad and was very proud of the work as a whole.[9]

In 1993, he sang Henry Mancini's "Pink Panther Theme" for the 1993 comedy film Son of the Pink Panther.

In addition to his vocal performing career, in 1994, McFerrin was appointed as creative chair of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. He makes regular tours as a guest conductor for symphony orchestras throughout the United States and Canada, including the San Francisco Symphony (on his 40th birthday), the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the London Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic and many others. In McFerrin's concert appearances, he combines serious conducting of classical pieces with his own unique vocal improvisations, often with participation from the audience and the orchestra. For example, the concerts often end with McFerrin conducting the orchestra in an a cappella rendition of the "William Tell Overture," in which the orchestra members sing their musical parts in McFerrin's vocal style instead of playing their parts on their instruments.

For a few years in the late 1990s, he toured a concert version of Porgy and Bess, partly in honor of his father, who sang the role for Sidney Poitier in the 1959 film version, and partly "to preserve the score's jazziness" in the face of "largely white orchestras" who tend not "to play around the bar lines, to stretch and bend". McFerrin says that because of his father's work in the movie, "This music has been in my body for 40 years, probably longer than any other music."[10]

McFerrin also participates in various music education programs and makes volunteer appearances as a guest music teacher and lecturer at public schools throughout the U.S. McFerrin has collaborated with his son, Taylor, on various musical ventures.

In July 2003, McFerrin was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music during the Umbria Jazz Festival where he conducted two days of clinics.[11]

In 2009, McFerrin and psychologist Daniel Levitin hosted The Music Instinct, a two-hour documentary produced by PBS and based on Levitin's best-selling book This Is Your Brain on Music. Later that year, the two appeared together on a panel at the World Science Festival.

McFerrin was given a lifetime achievement award at the A Cappella Music Awards on May 19, 2018.

McFerrin was honored with the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters award on August 20, 2020.

Personal life

He is the father of musicians Taylor McFerrin and Madison McFerrin, and actor Jevon McFerrin.[12][13]

Vocal technique

As a vocalist, McFerrin often switches rapidly between modal and falsetto registers to create polyphonic effects, performing both the main melody and the accompanying parts of songs. He makes use of percussive effects created both with his mouth and by tapping on his chest. McFerrin is also capable of multiphonic singing.[14]

A document of McFerrin's approach to singing is his 1984 album The Voice, the first solo vocal jazz album recorded with no accompaniment or overdubbing.[15]

Discography

As leader

As sideman

- Laurie Anderson, Strange Angels, 1989

- Chick Corea, Rendezvous in New York, 2003

- Jack DeJohnette, Extra Special Edition (Blue Note, 1994)

- En Vogue, Masterpiece Theatre, 2000

- Béla Fleck and the Flecktones, Little Worlds, 2003

- Chico Freeman, Tangents, 1984

- Gal Costa, The Laziest Gal in Town, 1991

- Dizzy Gillespie, Bird Songs: The Final Recordings (Telarc, 1992)

- Dizzy Gillespie, To Bird with Love (Telarc, 1992)

- Herbie Hancock, Round Midnight, 1986

- Michael Hedges, Watching My Life Go By, 1985

- Al Jarreau, Heart's Horizon, 1988

- Quincy Jones, Back on the Block, 1989

- Charles Lloyd Quartet, A Night in Copenhagen (Blue Note, 1984)

- The Manhattan Transfer, Vocalese, 1985

- Wynton Marsalis, The Magic Hour, 2004

- George Martin, In My Life, 1998

- W.A. Mathieu, Available Light, 1987

- Modern Jazz Quartet, MJQ & Friends: A 40th Anniversary Celebration (Atlantic, 1994)

- Pharoah Sanders, Journey to the One (Theresa, 1980)

- Grover Washington Jr., The Best Is Yet to Come, 1982

- Weather Report, Sportin' Life, 1985

- Yellowjackets, Dreamland, 1995

- Joe Zawinul, Di•a•lects, 1986

Grammy Awards

- 1985, Best Jazz Vocal Performance, Male for "Another Night in Tunisia" with Jon Hendricks from the album Vocalese.

- 1985, Best Vocal Arrangement for Two or More Voices, "Another Night in Tunisia" with Cheryl Bentyne.

- 1986, Best Jazz Vocal Performance, Male, "Round Midnight" from the soundtrack album Round Midnight.

- 1987, Best Jazz Vocal Performance, Male, "What Is This Thing Called Love" from the album The Other Side of Round Midnight with Herbie Hancock.

- 1987, Best Recording for Children, "The Elephant's Child" with Jack Nicholson.

- 1988, Song of the Year, "Don't Worry, Be Happy" from the album Simple Pleasures.

- 1988, Record of the Year, "Don't Worry, Be Happy" from the album Simple Pleasures.

- 1988, Best Pop Vocal Performance, Male, "Don't Worry, Be Happy" from the album Simple Pleasures.

- 1988, Best Jazz Vocal Performance, "Brothers" from the album Duets by Rob Wasserman.

- 1992, Best Jazz Vocal Performance, "Round Midnight" from the album Play.

External links

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bobby-McFerrin

- March 11, 1950 (age 72)

- New York City New York

Bobby McFerrin, (born March 11, 1950, New York, New York, U.S.), American musician noted for his tremendous vocal control and improvisational ability. He often sang a cappella, mixing folk songs, 1960s rock and soul tunes, and jazz themes with original lyrics. He preferred to sing without fixed lyrics, and he could imitate the sounds of various musical instruments with great skill.

McFerrin’s parents both had distinguished vocal careers. His mother, a soprano, was a Metropolitan Opera judge who chaired the vocal department at Fullerton College, near Los Angeles, and his father, who sang at the Met, dubbed actor Sidney Poitier’s singing on the 1959 Porgy and Bess sound track. In McFerrin’s youth he was inclined to become a minister of music, but, after attending California State University at Sacramento and Cerritos College in Norwalk, California, he instead became a pianist and organist with the Ice Follies ice-skating show and with pop music bands. In 1977 he auditioned for and won a singing job. As a swinging jazz and ballad vocalist, by 1980 McFerrin was touring with popular jazz singer Jon Hendricks. Inspired by Keith Jarrett’s improvised piano concerts, in 1982 he worked up the nerve to sing alone.

McFerrin issued his self-titled debut album in 1982, and it was followed by The Voice (1984), which was unusual because it featured no accompaniment; Spontaneous Inventions (1985), which featured music by Herbie Hancock and Manhattan Transfer; and Simple Pleasures (1988), which featured the hit song “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” He also recorded television commercials and a theme song for The Cosby Show; improvised music for actor Jack Nicholson’s readings of Rudyard Kipling’s children’s stories; and released an album with cellist Yo-Yo Ma, titled Hush, in 1992.

McFerrin was perhaps best known for his spontaneity; in concert he might wander through the auditorium singing, make up songs on listeners’ names, conduct his audience in choirs, or burst into a condensed version of The Wizard of Oz, complete with tornado sounds and munchkin, witch, and scarecrow voices. On record he could improvise all the parts in a vocal group himself, as he did in “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” In 1995 McFerrin released Paper Music, an album he collaborated on with the St. Paul (Minnesota) Chamber Orchestra that featured orchestral works by Mozart, Bach, Rossini, and other masters, with the melodies sung instead of played.

By the beginning of the 21st century, McFerrin’s work had garnered 10 Grammy Awards. His later recordings include Circlesongs (1997) and VOCAbuLarieS (2010), for which he drew from various world-music traditions to create minimally accompanied, harmonically rich choral pieces; the impressionistic jazz album Beyond Words (2002); and Spirityouall (2013), an homage to African American spirituals. In 2020 the National Endowment for the Arts named McFerrin a Jazz Master.

John Litweiler

A Conversation With....Bobby McFerrin

While rummaging through well-worn Jazz Reports, a magazine I published for a good eighteen years beginning in 1987, I came across my interview with vocalist Bobby McFerrin from August 1988. What makes this so intriguing is the fact the issue coincides with the release of McFerrin’s triple-platinum best seller, Simple Pleasures, featuring the massive hit, Don’t Worry, Be Happy.

McFerrin’s career was on the upswing and he was most willing to sit for a conversation detailing his ambitions, vocalizing, and plans for the future. I’d been familiar with his recordings, especially his 1982 debut, Bobby McFerrin, on Electra Musician with a brilliant cover of Van Morrison’s Moondance, which I frequently played on Q-Jazz back in 1985. Here’s that conversation – and by the way – he has 10 Grammys now!

Bill King: Unlike other jazz vocalists who pay homage to the past by recording traditional standards, you have chosen to explore the songs of the ‘60s. Do you have a particular fascination with this era?

Bobby McFerrin: Not necessarily a fascination, but I do think the ‘60s were rich with distinguishable sounds, unlike the homogeneity of today. You never know who is doing what today. In the ‘60s you had all these distinctive voices like Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Led Zeppelin – great groups who wrote some exciting music. I’m a ‘60s child, and that was the music I listened to. Jazz was the last music I got into, and that was in the early ‘70s. I think I was more influenced by rock and classical music than anything else, so I thought that, on Simple Pleasures, I would tip my hat and pay homage to the good music of the ‘60s.

B.K: Some songs are deemed untouchable considering the strength of their original interpretation, but you were able to breathe new life into classics such as Van Morrison’s Moondance, Lennon and McCartney’s From Me to You, and Cream’s Sunshine of Your Love. How did you go about selecting material?

B.M: Those are the sorts of tunes I like, but even pieces that I think I like may lend themselves to immediate treatment while others may take a while to put together. I usually go for those that I have some relationship with right away. That doesn’t mean I don’t take time to work on other tunes. There was another Beatles song; She’s A Woman, that almost ended up on this record. It’s a great tune. I had put down the basic tracks, but I couldn’t figure out what else to do with it. There’s a lot of waiting involved in the recording process so, I waited for something to happen, and eventually, I found that I had waited too long. I kept coming back to She’s A Woman, but by that time, I figured I’d just save it.

B.K: Is there something in the components of a song, whether melodically or lyrically, that you look for in a tune like You Really Got a Hold on Me?

B.M: You Really Got a Hold on Me was not one of my favourite choices, although at first, I thought it would be a good idea to do. I was still a young and naïve musician at that point, and that was my first record. It was difficult for me to say no. I didn’t take any chances with it so it could have been a better arrangement. Now, I’m taking chances.

B.K: On your first LP Bobby McFerrin, on Electra Musician, you surround yourself with a band, but since then you’ve chosen to go it alone. Why have you decided to work solo?

B.M: Well, even when I was working with a band, I had already decided to go it alone, but I didn’t think that my first LP should be a solo album. It just wouldn’t have been a good idea. My manager, Linda Goldstein, probably wanted to wait and see. Another reason is that I had all of these songs that I had written a few years before, such as my arrangement of Moondance and Feline, and they needed to be put on vinyl. These were the tunes I wanted to record. It just made sense to do the first record with a band.

B.K: Do you get many opportunities to use your keyboard skills?

B.M: There’s a piece on the Elephant’s Child record, which I did with Jack Nicholson, where I played some keyboards. It depends on the piece whether I hear keyboards. I’m more into the vocal instrument, and I’m going to stick with that. I don’t see me working on or orchestrating other instruments in the foreseeable future

B.K: You paid your dues playing lounges and different jobs. Are you grateful to have those days behind you?

B.M: Yes. I don’t think I’d like doing that now, but I can now see it was all a process and indeed a valuable experience.

B.K: What was your stay in Salt Lake City like when you were based there?

B.M: It was wonderful. That’s where I started singing, playing piano bars and thinking about solo voice. I was also exposed to working with dancers, so a lot of good things came out of Salt Lake City. It’s a beautiful place to live, close to the mountains. It was a wonderful two years of musical germination, which made a lot of things clear.

B.K: You credit Keith Jarrett’s spontaneous solo concerts as being what inspired you to attempt performing as a solo artist.

B.M: Most definitely! I was intrigued by him because he dared to walk out on stage with no set idea, sit down at the piano, play and it would work. I wasn’t exposed to any other musicians who were doing that at the time. If you’re an arranger or a musician, generally you walk out with a set-in mind, sit down and play. And often, you’ve got your lights, you’ve got your smoke, you’ve got you’re dancing girls, you’ve got your lines or whatever.

For rock in the ‘60s, they didn’t do that too much. You rehearsed and knew what you were going to do, but then along comes somebody who just sits down at the piano and plays. It was new every time, and I was captivated by it all.

B.K: How do you prepare for a concert?

B.M: I eat fruits, I pace, I talk, I read letters, I have dinner, take walks, pet dogs..

B.K: Are there any particular exercises that you practice to maintain your vocal flexibility?

B.M: I don’t drink milk, and I vocalize.

B.K: You turn your body into a rhythm machine and your voice into a variety of instruments. How did you develop this technique?

B.M: Out of necessity. My body does not contain a lot of instruments. It contains sounds and colours. The technique came out of necessity. When I work on something, I must ask myself, “What are the elements? Intonation. Good intonation. I’ll focus on that and just work at it. I would like to have the best intonation in the world, but I can’t just stand out there and sing notes. So, what am I going to do with my body? Nobody is going to sit in the audience and watch a singer sing perfectly and creatively if he just stands there with his hands in his pockets. So, I started to move my body and it helped me as a singer. The audience needs to see the sound, so body movement is a way of taking a sound and putting in into a physical form. It’s giving them, the audience, something to see.

B.K: You’ve developed the ability to play rhythm patterns while improvising a horn solo. How do you bring all this together?

B.M: Drummers. Drummers fascinate me with all the things they do. Left and right feet; left and right hands and especially, drummers that sing. They can’t be thinking my left foot is doing this and my right is doing that. They can’t be thinking consciously about that. It’s impossible. You can’t divide your mind into four different activities at once.

B.K: Could you suggest a simple warm-up exercise for vocalists?

B.M: Sing tenths.

B.K: Do you have any favourite vocalist that you enjoy listening to?

B.M: Anita Baker, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, Steve Winwood, Joni Mitchell, Taj Mahal sometimes, and many others.

B.K: How do you view the music of the ‘80s?

B.M. There’s nothing distinguishable about most of the groups. You’d think that it would be the producer’s job to get the groups or musicians to be as unique as possible. The difference between the ‘60s and the ‘80s is that Janis would open her mouth, her musicians would be playing guitars plugged into amplifiers turned to 10, and they would wail. Now, you’ve got a guitar with 13 buttons, plugged into 12 more buttons on the floor, plugged into computers, plugged into a person backstage, plugged into 12 Marshalls speakers, plugged into a video screen.

There are only a few musicians I know who can handle that, creatively. Pat Metheny is one. I wouldn’t call him a rock musician. But he certainly has a rock undercurrent, along with jazz, classical and folk influences, yet he’s capable of synthesizing all these individual types of music into one voice. A lot of musicians don’t know who they are. Artists must take control of themselves. There are a lot of good vocalists out there, but many are drowned by technology.

B.K: Do you have any desire to record a pure jazz album?

B.M: I’ve thought about it, and one day I might go into the studio with a trio and do a straight-ahead jazz record, I’m not closed-minded enough to say, “No, I won’t do that,” but presently I have no such intentions.

B.K: You’ve won five Grammys, and you’re heard across North America each week on the Cosby Show and as the voice on the Levi jeans commercial. What else do you envision yourself exploring in the future?

B.M: Writing movie scores, television scores, an opera, putting a vocal group together and writing poems, along with staying home and singing in the bathtub.

https://www.eomega.org/article/sing-your-prayers-an-interview-with-bobby-mcferrin

Sing Your Prayers:

An Interview With Bobby McFerrin

Elizabeth Lesser, Omega's cofounder, talks with Bobby McFerrin about music, spirituality, and the joy of play.

Elizabeth:

Your songs often don’t use words, but they carry as much meaning,

depth, and emotion as the most beautiful, skillful lyrics. Is it a

conscious choice not to use words? How can “nonsense sounds” evoke such

an emotional response?

Bobby: I don’t think of

them as nonsense sounds; I think of them as language beyond words. When

we listen to improvisational jazz, or solo classical violinists, the way

they phrase and inflect melodies feels vocal, like they’re talking to

us. When I was figuring out how to perform solo, I wanted to move back

and forth between bass riffs, melody, and harmony, so I often used

sounds instead of—or alongside—the words of a song. I found that if I

sang a line using the consonants, vowels, shadings, and inflection we

recognize as human language sounds, people responded as if I were

talking to them. There is a human connection even though there are no

words. If I sing “you broke my heart, you left me flat,” everyone knows

exactly what that means—they know the story. But if I sing a line that’s

plaintive or wailing, people can experience their own set of emotions

and their own story. Each of us might give that phrase a different

meaning. It’s open to interpretation, and one song becomes a thousand

songs. I love that. Inviting audiences to open up and hear things

differently is an important part of what I do. But I still love to sing

songs with words, too.

Elizabeth: Was your

family religious? Was music part of your spiritual life as a kid? Do you

consider it to be part of your spiritual life as an adult?

Bobby:

My family was deeply religious, and music was one of the ways we prayed

and worshipped. My parents were both professional singers and singing

teachers, and my mother was the soprano soloist at our church. Music is

still part of my spiritual life. Sometimes I sing my prayers. When I get

audiences singing, I hope I’m helping them feel connected to something

beyond themselves.

Elizabeth: You teach musical

improvisation at Omega. Do you think improvisation is a skill that can

help people in other aspects of life—at work, or at home with families

and friends?

Bobby: Improvisation means

coming to the situation without rigid expectations or preconceptions.

The key to improvisation is motion—you keep going forward, fearful or

not, living from moment to moment. That’s how life is. Remembering that

life can be full of surprises is useful in any part of your life. You

can try a new way of singing a song you’ve performed for years, a new

way of showing your family your love for them, or a new recipe. Don’t

just play the licks you know. We’re all improvising all the time—it’s

good to recognize that and embrace it.

Elizabeth:

Sometimes when I am writing I don’t feel as if “I” am writing. Rather, I

feel something comes through me, that the words already exist and I am

just catching hold of them. Do you have that experience? Are the songs

already “out there” waiting for you to catch hold of them?

Bobby:

Yes, I know that feeling. What I do is mostly made up on the spot, so

I’m used to it, and I’m used to thinking about my options. I can catch

an idea, stay with it, and let it develop. Or, I can let go and move on

to the next thing. There’s always another idea waiting—another sound.

Elizabeth:

You’re known for so many different kinds of music. You had an early pop

hit with “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” you’re an improvisational jazz

phenomenon, you’re an orchestral conductor, and you’ve created some of

the most sacred spiritual music that I’ve ever heard. When I first heard

the way you put Psalm 23 to music, I was moved to tears. Why did you

use the word “she” when speaking about God in that piece?

Bobby:

The 23rd Psalm is dedicated to my mother. She was the driving force in

my religious and spiritual education, and I have so many memories of her

singing in church. But I wrote it because I’d been reading the Bible

one morning, and I was thinking about God’s unconditional love, about

how we crave it but have so much trouble believing we can trust it, and

how we can’t fully understand it. And then I left my reading and spent

time with my wife and our children. Watching her with them, the way she

loved them, I realized one of the ways we’re shown a glimpse of how God

loves us is through our mothers. They cherish our spirits, they demand

that we become our best selves, and they take care of us.

Elizabeth:

Years ago when you taught at Omega, I used to sit on the bench at the

Omega basketball court and watch you play with your kids and my kids.

You made all of the boys feel good just to be playing, even if they

weren’t “good” at the game. That is what happens when you teach—you just

seem to have a way of making people feel good. Is that part of the

motivation for you as a musician?

Bobby: I think

play and joy and feeling good deserve more of our time. I don’t see why

adults are supposed to grow out of those things. If I have a mission

it’s to make everyone who comes to my concerts leave feeling a

heightened sense of freedom to play, sing, and enjoy themselves.

Elizabeth:

Vice-President Al Gore once spoke at an Omega conference and we asked

you to give him a musical introduction. You started improvising the

Vice-President’s name: “Al Gore, Come on out. Al Gore, Come on out....”

The whole audience starting singing with you. By the time Al Gore came

out, he was smiling and singing himself. What you did relaxed everyone,

and when the vice president started to speak, we were with him and grace

was in the room. How does music do that?

Bobby:

I don’t know. It’s pretty great, though. Music and play can take people

out of their everyday worries and remind them of freedom and joy.

Elizabeth: Do you think music can heal us emotionally or physically?

Bobby:

Yes, I do. When I was a kid, my mother took that very literally. When

we got sick, she’d put us to bed and put music on to make us feel

better. Even now, if I’m getting ready for a concert and I have a

headache or I’m worried about something, I can usually sing my way

through it. When I come off stage, I feel better.

Elizabeth:

I’m a grandmother now. My grandson is two-and-a-half years old and is

singing about everything. In his world, everything can be turned into a

song. Everything has its own tune and lyrics. Each of his toy trucks has

its own voice and accent and tone. You seem to live in a similar world.

How are you able to teach that?

Bobby: You

know, I don’t teach it. If I stand there, appreciating the world around

me as full of amazing sounds and the possibility of new ones, I think

that invites other people to see the world that way, too. I love sharing

the experience of singing with people, and I love sharing my stories.

But when it comes to teaching, I have a lot of help. At Omega, I

surround myself with amazing singers and teachers who are each masters

at helping students find their voice.

Elizabeth:

There’s a nakedness to your music and to the way you perform—you are

being exactly, unapologetically, purely who you are. Why is it so hard

for us to be ourself? It’s what we’re drawn to in artists, it’s what we

want from each other, that authenticity, but we keep ourselves hidden.

How can we liberate ourselves from the fear of being who we are?

Bobby:

I’m not a scholar or a psychologist, so I don’t really think about why.

But I do think about what it means to sing to and with people, to offer

music to them, and to ask them to spend time with me. I try not to

“perform.” I try to come on stage and be myself, to sing the way I would

in a room by myself, to interact with the audience the way I would

relate to them if we were in my kitchen drinking tea and making up silly

songs. Maybe the way to get past the fear of being ourselves is simply

to try it more often.

In Celebration of the Human Voice - The Essential Musical Instrument

Bobby McFerrin Biography

Click Here for Arrangements, Compositions and Recordings

On the 11th of March, 1950, Bobby McFerrin was born. His parents were classical singers and he began to study music theory early on in his life. His family then moved to Los Angeles. During high school and then in College, UCSC, he focused on the piano. Once he finished college, Bobby McFerrin toured with numerous bands including the Ice Follies.

However, it was only in 1977 that Bobby McFerrin decide to become a singer. At one point he met Bill Cosby who arranged for him take part in the 1980 Playboy Jazz Festival. It was only two years later where he released his firm album called "Bobby McFerrin" in 1982. It was in 1983, that Bobby McFerrin started converting without a band. This eventually led him to make a solo tour in Germany. It was in Germany that he recorded his album "The Voice". From that point on, he continued to make solo tours in the most prestigious locations. It is also important to realize that Bobby McFerrin worked with several important people like Garrison Keillor, Jack Nicholson, and Joe Zawinul. On "Another Night in Tunisia", Bobby McFerrin won two Grammies.

McFerrin was also featured in TV commercials for Levi's and Ocean Spray and also ended up singing the theme song for the Cosby Show and the movie Round Midnight by Bertrand Tavernier which got hum another Grammy. By now, Bobby McFerrin had achieved a great deal of success as a vocal and had released his platinum album Simple Pleasures which included the hit "Don't Worry be Happy".

As an Orchestrator, Bobby McFerrin demonstrated his skills in 1990 when he released Medicine Music. He appeared on Arsenio Hall, Today and Evening at Pops. Beyond that, he recorded Hush with Yo-Yo Ma in 1992. The Hush album stayed on the Billboard Classical Crossover Chart for two years until he went gold in 1996. In 1992, Bobby McFerrin also released a new Jazz album called Play which earned him his 10th Grammy award. He is without a doubt one of the greatest Jazz Artists of all time.

McFerrin also worked with classical music. In fact, his first classical album named Paper Music was recorded with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. His symphonic conducting included the convert-length version of Porgy and Bess. This very album remains on the Billboard chart of classical bestsellers.

There is another important aspect of McFerrin's life. He was part of the artistic leadership of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and in 1994 he joined as the creative chair. Among his numerous other activities, McFerrin he developed a program called CONNECT which is an education and outreach program. In 1996, he was recognized for his work with bringing the youth into classical music as the ABC Person of the Week. Also, he was given a 60 minutes feature with Mike Wallace.

His most recent works has been his album Bang Zoom which was released in January of 1996. Also, his latest work Circle Songs he focussed on his tremendous vocal talent. He continues to conduct symphonies. Indeed, he has conducted in practically all the great orchestra including the New York Philharmonic. Over the years, Bobby McFerrin has been an inspiration to millions and a musician who has evolved the music he so passionately works with.

Awards

1986 - Grammy Winner - Best Vocal Arrangement for Two or More Voices - Night in Tunisia

1988 - Grammy Winner - Song Of The Year - Simple Pleasures

1989 - Grammy Winner - Record of the Year - Don't Worry, Be Happy

1989 - Grammy Winner - Song Of The Year - Don't Worry, Be Happy

1992 - Grammy Winner - Best Jazz Vocal Performance - Mouth Music

Groups Directed

Voicestra

Media Articles

Los Angeles Times, McFerrin's Latest Big Hit: Voicestra

Bobby McFerrin Videos

https://www.kqed.org/arts/13913133/bobby-mcferrins-circlesongs-and-the-politics-of-play

Bobby McFerrin’s ‘Circlesongs’ and the Politics of Play

Do you remember the last thing you said aloud?

No? That’s ok. Try saying this: “Wow.” Pucker up. Let the lips widen and whip around a small ball of air before returning to their pursed shape. “W-O-W.” Now do it again. See that coworker looking at you strangely? Invite them to join you. “Wow.” Keep it up, until it loses all sense and becomes pure sound.

If you’re still with me, you’ve already enacted the core principle of Bobby McFerrin’s performance practice: playful repetition. For McFerrin, there’s a thin line between spoken word and song. A simple “wow” from the crowd becomes a bebop solo or a chorale in four-part harmony.

“As musicians,” McFerrin told me last week, “we say, ‘Okay, ready, set, play.’ And I take that literally. The stage is a platform for adventure…Everything is game.”

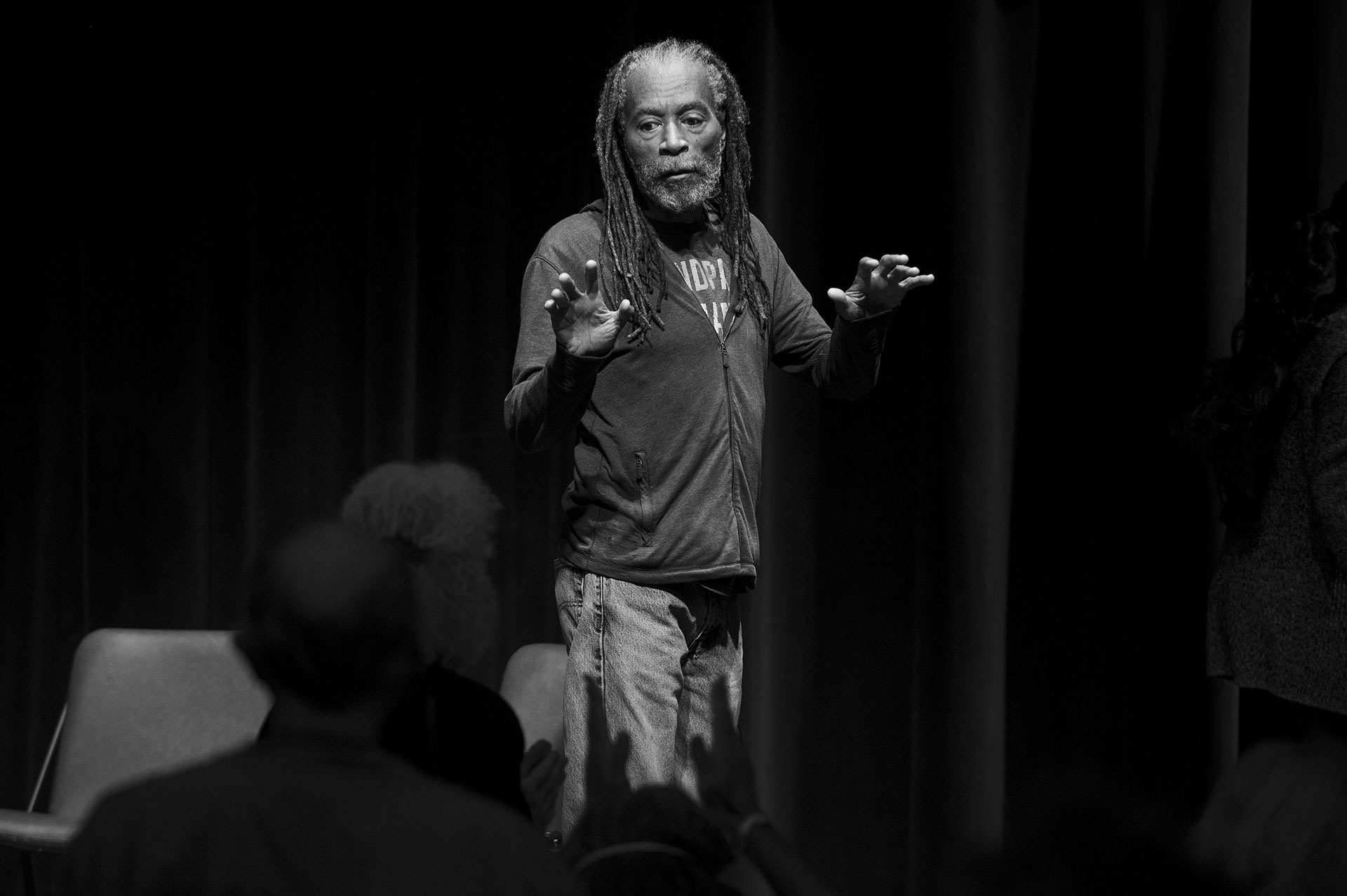

You might know McFerrin as the voice behind the 1988 hit “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” or even as one of the inspirations for Key and Peele’s “Kings of Mouth Noise” sketch. But scratch the surface of celebrity, and you’ll realize that McFerrin is one of the most inimitable musicians of the past 40 years: a virtuosic solo performer with a four-octave range, conductor of St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, and 2020 NEA Jazz Master.

Now in his seventies, McFerrin has returned to the stage, performing his Circlesongs at Freight and Salvage each Monday through the end of May. It is the best kept secret in Berkeley right now. Playing the audience as his second instrument, McFerrin is clearly still an unparalleled creative force, a peaceful warrior of song.

A Communal Jam Session

McFerrin released Circlesongs as an album in 1997, but the term describes something much bigger: a completely improvised collective performance. The project began in the late 1980s, first as “Voicestra,” then “Hard Choral” in the nineties, and, until the pandemic, “Gimme 5.” The latest group, “Motion,” is aptly named.

“The simplest definition of improvisation is motion,” says McFerrin. “Play one note, then you play another one, and then another. And everyone can do that. It's just like following words on a page.”

If improvising is like reading a book, it’s one we’re all writing. McFerrin leads Circlesongs, playing the microphone like a piccolo, his longtime soundman Dan Vicari adding just the right amount of reverb to turn the wooden paneled room into a European cathedral. But like any great improviser, McFerrin knows how to foreground others. Bryan Dyer sings a rubber-band bassline to every figure, accompanied by the uncanny realism of Dave Worm’s vocal percussion. Destani Wolf harmonizes above and below, while Tammi Brown takes us into heavens of the higher registers. If you’re a vocalist or instrumentalist, don’t forget your axe: you may find yourself onstage.

Circlesongs is a communal jam session, but it’s also a very personal affair. This is especially true for Dave Worm, who was a theology student in Berkeley in the 1980s when he discovered McFerrin’s music at Leopold’s Records. As Worm recalls, “I just thought, if I could ever sing like this guy … that would be the thing.”

Worm changed career trajectories, and later that year, when he was singing at a Christmas party at the Newman Center, in walked McFerrin. The chance encounter led to a series of auditions, and the two have now been performing together for nearly 30 years.

But of all the members on stage, Circlesongs is most personal for McFerrin. Having spoken openly about Parkinson’s and the sudden loss of his friend Chick Corea, performance is for him an act of spiritual healing.

“I’ve done some concerts, and [beforehand] I felt physically lousy,” he explains. “And then I do the gig and find out that 90 minutes later, I feel so much better.”

Democratic Principles at Play

I’m usually wary, as a secular Jew in a Christain society, of any whiff of organized religion. But to become part of McFerrin’s communal canvas is to come as close to a religious experience as I’ve ever had. Circlesongs unsettles the distinction between the spiritual and the secular: it all comes full circle.

If you’re not “wow-ed” or easily moved, you’ll definitely learn something. McFerrin often tells stories about his father, Robert McFerrin Sr., who was the first African American to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. As he tells it, “I used to hide under the piano as a kid. And so I heard some of his voice lessons.”

When he described these lessons to me, they sounded painstakingly detailed. But “Papa would take a mediocre singer and turn them into a really fine instrument.” With Circlesongs, McFerrin revises his father’s method by making play the most powerful pedagogy, teaching us that we are in fact our own best teachers.

Though singing collectively is an ancient practice, McFerrin’s Circlesongs gives it new meaning today. “I've been thinking a lot about musicians’ role during this time,” he told me, “the political unrest that's going on in the world, on the planet. The threats to our everyday lives and the role that singing can have.”

Because we’ve spent the past five years fearing the rise of fascism, and the last two terrified of each other’s breath, Circlesongs is paean to the democratic principle of shared air. The performance reminded me of the etymological meaning of inspiration: to allow yourself to be breathed into. Even though the audience is vaccinated and masked, it’s still the first time—in a long time—where everyone laughing and singing around me felt less like a burden and more like a blessing.

Thus, McFerrin’s Circlesongs offers play as not just an aesthetics but a politics, a way not of escaping the problems of the world but a way of shaping them. “This might sound really naïve,” he says “but the first thing the politicians should do is sing. Talk later. They should first become acquainted with each other’s songs and dances and rituals.” Singing for him is not simply a celebration of victory nor a palliative for defeat, but a practice, something you do to instantiate change in the world everyday.

It's no coincidence, then, that the show starts at 12pm. People are hungry for incorporating improvisation into their daily lives, and Circlesongs offers that nourishment weekly. If you can make it, but especially if you can’t, pay attention to the last thing you said—because every breath has the potential to take flight into song.

Bobby McFerrin performs ‘Circlesongs’ each Monday, at noon, at Freight & Salvage in Berkeley. Details here.

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/08/15/arts/bobby-mcferrin-unworried-and-happy-and-a-conductor.html

Bobby McFerrin:

Unworried And Happy and a Conductor

As the popular and classical musical cultures pull farther apart, crossing back and forth has become, for some reason, that much more intense. Bobby McFerrin -- the vocal explorer whose "Don't Worry, Be Happy" swept the nation in 1988 and buoyed (to Mr. McFerrin's displeasure) George Bush's Presidential campaign -- will set aside his four-octave singing range and arsenal of naturally produced sound effects for a while on Thursday to conduct the Beethoven Seventh Symphony and five other pieces.

Mr. McFerrin's foray into the jaws of the New Jersey Symphony at the Garden State Arts Center in Holmdel will include some familiar items by Bizet, Faure, Vivaldi and Bach. He will also do some of the improvisational singing for which he is best known.

There is a lot Mr. McFerrin does not know about conducting, and he says he is not afraid to ask. "If I want to get a certain sound from the orchestra," he said by phone from the Berkshires the other day, "I ask the concertmaster and he shows me how to do it. Sometimes musicians ask me questions I have to get translated. Jazz musicians just speak English to each other. I'm less used to this terminology."

"Remember, I only have one rehearsal for six pieces," he said. "One thing I have found out watching other people rehearse is that the less you say the better. You either do it with gesture or, better yet, you sing it the way you want it to sound. I'll get up there and see what happens. You never know. I believe in being prepared but not over-prepared." Separation of Traditions

Such a transfer of talents could have been transacted more easily 100 years ago, when barroom ballads shared the harmonies, singing techniques and melodic styles of Brahms and Dvorak. Since then, the enormous influence of African-American culture -- with its sophisticated rhythms and less flexible metric style -- has separated pop from a European tradition of phrases that flex and contract like breathing and human speech.

Whether the twain meet on Thursday will depend a lot on how good a conductor Mr. McFerrin is. He first tried it, after some private study, at the San Francisco Symphony a year ago. He also comes to the repertory naturally. His father, Robert McFerrin, sang at the Metropolitan Opera, and the younger Mr. McFerrin was improvising at the piano at the age of 3 and studying at Juilliard at 6. His childhood was dotted with piano lessons, harmony and counterpoint and a distaste for practicing.

He found his permanent connection to jazz and popular music as a college student in California, using Miles Davis and Keith Jarrett as models. From there Mr. McFerrin developed an unusual skill for using his own body surfaces, cavities and appendages for timbral effects. His 1988 compact disk, "Simple Pleasures" -- which includes the famous "Don't Worry, Be Happy" -- is largely a one-man effort: vocal solos, vocal support and quasi-instrumental accompaniments laminated together from separate sound tracks.

The singing style is light and agile, a good distance from the monolithic certitudes of Beethoven's A-major Symphony. Yet his 11-member singing group, Voicestra, includes voices and techniques from all along the musical spectrum. A la Mode

Mr. McFerrin has a chance on Thursday to say something interesting about concert music's current war of styles: Do we go back and do it Beethoven's way, with the sound of his instruments and his era's approach to style in our ears? Or do we transmute the past to meet the needs of the present? "I guess I would choose the latter side," said Mr. McFerrin. "I need to get in the composer's mind, but I'm a composer, too, and I'm also an improvisational artist. When I'm up there in front of an orchestra I might do something slower or faster; spontaneously try something new."

Bobby McFerrin: Live in Lviv!

October 22, 2015

Bobby McFerrin: Live in Lviv! (excerpt), June 15, 2013 with the Spirityouall Band. Bobby's solo turns into a duet with a longtime favorite collaborator: the audience. Featuring Louis Cato, drums; Scott Colley, bass; Gil Goldstein, keyboards; David Mansfield, mandolin; Armand Hirsch, guitar.

https://www.singers.com/group/Bobby-McFerrin/

Bobby McFerrin

On the 11th of March, 1950, Bobby McFerrin was born. His parents were classical singers and he began to study music theory early on in his life. His family then moved to Los Angeles. During high school and then in College, UCSC, he focused on the piano. Once he finished college, Bobby McFerrin toured with numerous bands including the Ice Follies.

However, it was only in 1977 that Bobby McFerrin decide to become a singer. At one point he met Bill Cosby who arranged for him take part in the 1980 Playboy Jazz Festival. It was only two years later where he released his firm album called "Bobby McFerrin" in 1982. It was in 1983, that Bobby McFerrin started converting without a band. This eventually led him to make a solo tour in Germany. It was in Germany that he recorded his album "The Voice". From that point on, he continued to make solo tours in the most prestigious locations. It is also important to realize that Bobby McFerrin worked with several important people like Garrison Keillor, Jack Nicholson, and Joe Zawinul. On "Another Night in Tunisia", Bobby McFerrin won two Grammies.

McFerrin was also featured in TV commercials for Levi's and Ocean Spray and also ended up singing the theme song for the Cosby Show and the movie Round Midnight by Bertrand Tavernier which got hum another Grammy. By now, Bobby McFerrin had achieved a great deal of success as a vocal and had released his platinum album Simple Pleasures which included the hit "Don't Worry be Happy".

As an Orchestrator, Bobby McFerrin demonstrated his skills in 1990 when he released Medicine Music. He appeared on Arsenio Hall, Today and Evening at Pops. Beyond that, he recorded Hush with Yo-Yo Ma in 1992. The Hush album stayed on the Billboard Classical Crossover Chart for two years until he went gold in 1996. In 1992, Bobby McFerrin also released a new Jazz album called Play which earned him his 10th Grammy award. He is without a doubt one of the greatest Jazz Artists of all time.

McFerrin also worked with classical music. In fact, his first classical album named Paper Music was recorded with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. His symphonic conducting included the convert-length version of Porgy and Bess. This very album remains on the Billboard chart of classical bestsellers.

There is another important aspect of McFerrin's life. He was part of the artistic leadership of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and in 1994 he joined as the creative chair. Among his numerous other activities, McFerrin he developed a program called CONNECT which is an education and outreach program. In 1996, he was recognized for his work with bringing the youth into classical music as the ABC Person of the Week. Also, he was given a 60 minutes feature with Mike Wallace.

His most recent works has been his album Bang Zoom which was released in January of 1996. Also, his latest work Circle Songs he focussed on his tremendous vocal talent. He continues to conduct symphonies. Indeed, he has conducted in practically all the great orchestra including the New York Philharmonic. Over the years, Bobby McFerrin has been an inspiration to millions and a musician who has evolved the music he so passionately works with.

STAY TUNED FOR

THE NEW WEBSITE

CHECK BACK SOON!

In the mean time... Why not check out

Circlesong School 2022 this August, Berkeley, CA

Bobby McFerrin: Live in Lviv!

October 22, 2015

Bobby McFerrin : Don't Worry Be Happy - Parts CD

Review: What a great way to introduce the music of Bobby McFerrin to younger choirs. Winning the Grammy in 1989 this hit tune will bring a smile to everyone's face. Discovery Level 2. Available separately: 2-Part VoiceTrax CD. Duration: ca. 3:30.

Songlist: Don't Worry Be Happy

2002p | Voicetrax CD | $24.95 Vocal Jazz VoiceTrax Recordings

Bobby McFerrin : Live In Montreal

Review: Since a cappella pioneer Bobby McFerrin singlehandedly gave the vocal arts a hand up to a whole new level of possibilities in the 1980s with his iconic hit "Don't Worry, Be Happy," we have looked at him and listened to him with awe and gratitude. Experiencing him perform live several times only increased these feelings exponentially, and we had the feeling that everyone in the audience was on exactly the same page. Well, in the early 90s Bobby seems to have picked up on that, and has invited the audience to participate, and included interaction with guest musicians, all improvised. This has cemented his reputation as a marvelous entertainer, and has created a new kind of concert-not a performance, but a "communal sharing and celebration of music." This is exactly what the new DVD "Live in Montreal" is all about. It's beautifully filmed at the "Festival International de Jazz de Montreal," In these 21 video cuts, part of the audience is right up on stage with Bobby, and he improvises and creates musical events with them and members of the main audience. He improvises with a trapeze artist above him, and with a singing viola player. I'll just list some of the cut titles to give you a taste of what happens in this very special DVD: 12. "Improvisation with Richard Bona," 13. "Improvisation, Country Stuff," 13. "Baby," 14. "Improvisation with Tamango "Well You Needn't," 15. "Bwee Do," 16. "Le Grand Choeur de Montreal, It's a Wonderful World," 17. "Circlesong One," 18. "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" and 19. "The Wizard of Oz Medley." Bobby is a living a cappella legend, and this live show is creative, funny, touching and simply brilliant. Don't miss this one!

Songlist: Improvisation Style "Little Red Book", Improvisation with the People on Stage, Improvisation with Evelyne Lamontagne on the Trapeze (Extracts from the Opera Carmen), Improvisation with the Audience, Improvisation with Jorane "Riopel", Improvisation "Gonna Move", 'The Jump", "Drive", "Ave Maria', Richard Bona "Dina Lam", Improvisation with Richard Bona, Improvisation "Country Stuff", Baby, Improvisation with Tamango "Well You Needn't", "Bwee Doo", Le Grand Choeur De Montreal "It's A Wonderful World", "Circlesong One", "Somewhere Over The Rainbow", "The Wizard of Oz Medley", Melody from "Sun Concert 5", Sings Walking Off Stage

4609d | DVD | $21.95 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz DVDs

Bobby Mcferrin : VOCAbularieS

Review: Ten-time Grammy Award winner/vocal innovator Bobby McFerrin surprises us yet again with VOCAbuLarieS, his first new release in eight years. Like his #1 worldwide hit song Don't Worry Be Happy and his multi-platinum duo album Hush with cellist Yo-Yo Ma, VOCAbuLarieS is based on Bobby's experiments with multi-track recording and his ceaseless exploration of the potential of the human voice. VOCAbuLarieS is Bobby McFerrin music for the 21st century. A collaboration with the composer/arranger/producer Roger Treece, VOCAbuLarieS features over fifty of the world's finest singers, recorded one at a time and in small groups to create a virtual choir made up of over 1,400 vocal tracks. Constructed as meticulously as a Mozart symphony or a Steely Dan album, intricately synthesized from countless stylistic elements, VOCAbuLarieS may be unlike any album anyone has ever recorded. Yet the music is always accessible, joyous, and inviting. VOCAbuLarieS celebrates Bobby's love of all musical genres, from classical to world music, R&B to gospel and beyond, building upon McFerrin's past explorations and journeying into bold new territory. If the song Don't Worry Be Happy is all you know about Bobby McFerrin, sit back and prepare to be amazed.

Songlist: Baby, Say Ladeo, Wailers, Messages, The Garden, He Ran To The Train, Brief Eternity

2336c | 1 CD | $15.95 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz CDs

Bobby McFerrin : Try This At Home

Review: Recorded in front of a live intimate audience at Minneapolis' Walker Arts Center in September 1999, "Try This At Home" features the 10-time grammy Award winner Bobby McFerrin in a version of his renowned solo vocal concert. Entirely improvised, the performance displays Bobby's astonishing vocal virtuosity and musicianship, and his gift for audience interaction. With a comedian's sense of timing, an unrestrained zany streak, and an infectious love of every genre of music, Bobby's solo show is not a 'performance' but a communal sharing and celebration of music.

Songlist: Mysteries, Harmonizin, Try this at home, In the morning, Staccato groove, Opera style, The shirt-scratching song, Head in my bed blues, Folk rap, Walkin' on the beat, Out we go, Ducks, The name song, Calyso sing, More singin

4608d | DVD | $15.98 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz DVDs

Bobby McFerrin : Beyond Words

Review: Bobby, the a cappella legend, may have crossed the line into the land of accompaniment on "Beyond Words," but let us just say that there is accompaniment, and then there is Chick Corea on piano, with musicians of similar stature on bass, percussion, drums and guitar, and Bobby himself playing the Roland XP-80 synthesizer. Let us also say that Bobby McFerrin has heavily influenced (many would say personally created) the resurgence in a cappella music in the last two decades, and that that was no mistake or lucky break. He is an artist who pushes the vocal jazz envelope, and he's pushing it here. 16 songs that take Bobby's art - what he does better than anyone else - that is, use his voice as an incredibly multi-faceted instrument, to create sounds and moods that no one has ever created before. "Invocation," "Kalimba Suite," "A Silken Road" - each is a little masterpiece of vocal and instrumental improvisation, as beautiful and earth pastel-colored as the stunning liner notes. Listen and be in awe!

Songlist: Invocation, Kalimba Suite, A Silken Road, Fertile Field, Dervishes, Ziggurat, Sisters, Circlings, Chanson, Windows, Marlowe, Mass, Pat & Joe, Taylor Made, A Piece, A Chord, Monks / The Sheperd

4489c | 1 CD | $15.98 Vocal Jazz CDs

Bobby McFerrin : Beyond Words

Review: Beyond Words traces the personal, musical, and career history of 10-time Grammy Award winner Bobby McFerrin, from his earliest musical inspirations through his vast yet intimate experiences in popular music, jazz, choral, orchestral, and solo performance. See how this consummate musician has traveled along the continuum of the musical world to find himself championing singing and performing - beyond instruments, beyod tradition and Beyond Words. In personal interviews, Bobby reveals the difficulties in finding his calling in life, his personal philosophy on creating, his classical origins, the secrets of collaborating, and the importance of family. Featuring interviews and performances with Robin Williams, Chick Corea, James Levine, Herbie Hancock, Yo-Yo Ma, and more.

Songlist:

4607d | DVD | $15.98 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz DVDs

Listen to Drive My Car

Bobby McFerrin : Simple Pleasures

Review: "Don't Worry, Be Happy" is the opening tune of a collection of multi tracked songs on which all the voices are Bobby McFerrin's. Five originals including the title track "Simple Pleasures" are interwoven with "Drive My Car" (Lennon/ McCartney), "Good Lovin'," "Susie Q," "Them Changes" (Buddy Miles) and Sunshine Of Your Love. Throughout this recording is the percussive chest thump which Bobby pioneered and really must be considered the origin of innovative vocal percussion which has become so important to contemporary a cappella.

Songlist: Don't Worry, Be Happy, All I Want, Drive My Car, Simple Pleasures, Good Lovin', Come To Me, Suzie Q, Drive, Them Changes, Sunshine Of Your Love

4153c | 1 CD | $10.98 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz CDs

Listen to

From Me To You

Bobby McFerrin : Spontaneous Inventions

Review: How do you capture spontaneous creation? Blue Note's answer was to present the widest possible variety of performances on one CD in order to capture the sense of someone who is spontaneous in every performance. They succeeded admirably! Three originals, four solo interpretations of other composer's work, singing around the piano of Herbie Hancock, facing off with the soprano sax of Wayne Shorter, and a hysterical "Beverly Hills Blues" (improv with Robin Williams), are the contents but one. That one is "Another Night In Tunisia," sung with The Manhattan Transfer and Jon Hendricks. It's a must for any collection...

Songlist: Thinkin' About Your Body, Turtle Shoes, From Me To You, There Ya Go, Cara Mia, Another Night In Tunisia, Opportunity, Walkin', I Hear Music, Beverly Hills Blues, Manan Iguana

4152c | 1 CD | $10.98 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz CDs

Bobby McFerrin : Spontaneous Invention

Review: This video was filmed for HBO live at the Aquarius Theatre in Hollywood in 1986, the year McFerrin won a Grammy - when he was at his first peak as a one man jazz band. It is absolutely marvelous to watch the energy and humor of this musical genius interact with an audience. On the CD you can hear "Thinkin' About Your Body" but you don't see the interlude where McFerrin suddenly starts improvising on someone's leather jacket. Watching him create "Bwee-Dop"using audience participation is very different from just hearing it (which is why it didn't make the CD), and there's no substitute for watching him egg on the crowd to do the hand signals in "Itsy Bitsy Spider," On "Fascinating Rhythm," his expressions are priceless as he emulates a 1940s jazz band. And his duet with/accompaniment to soprano saxaphonist Wayne Shorter is all the more astounding as you see the two of them lock eyes and minds. Of the 12 songs here, only four are on the CD. We highly recommend this DVD!

Songlist: Scrapple From The Apple/honeysuckle Rose, Bwee-Dop, Cara Mia, Fascinatin' Rhythm, Itsy Bitsy Spider, Thinkin About Your Boy, Drive, Opportunity, I Got the Feelin', Walkin, Blackbird, Manana Iguana, Don't Worry, Be Happy (music video), Good lovin (music video)

4603d | DVD | $19.95 | A Cappella Performance DVDs

Bobby McFerrin : Swinging Bach

Review: "Swinging Bach" is a 122 minute documentary of a festival that took place in the old town square of Leipzig, Germany. before a large, appreciative audience (who are standing throughout, are introduced to the groups in both English and German by an attractive pair of emcees, and who get seriously rained on later in the show). Featured are 12 groups of different genres, mostly instrumental, all playing Bach pieces or variations on Bach pieces. The German Brass and the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, directed by Christian Gansch, are followed by a jazz interpretation of "Fugue No. 5 in D Minor" by the Jacques Loussier Trio, then another Bach Concerto and Fugue by the Leipzig orchestra and the German Brass. Then comes one of our favorite pieces, Bobby McFerrin with the G. Leipzig, doing a wonderful faux (violin?) lead on "Orchestra Suite No. 3 in D Minor," followed by more German Brass, G. Leipzig and some nice pieces by two quintets, the Quintessence Saxophone Quintet and Turtle Island String Quintet. Another of our favorites follows, The King' Singers. with a brilliant a cappella medley of Bach samples, "Deconstructing Johann," with their own very funny added lyrics, which we would like to see written down so we could appreciate them more. Quite a few added features follow, our favorites being "Improvisation on "Wachet auf ruft uns de Stimme," featuring Bobby with the Loussier Trio, and a piece with Bobby and the G. Leipzig where he goes into one of his standard concert improvisational vocal riffs. "Swinging" is an amazing event with some particularly nice work by McFerrin and the King' Singers.

Songlist: Concerto in D Major, BWV 972, 1st Movement, Allegro (German Brass), Orchestra Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066, Bouree I/II (Gewandhausorchester

Leipsig, Christian Gansch

Fugue No. 5 in D Major, BWV 850, from "The Well-Tempered Clavier" (Jacques

Loussier Trio), Concerto for 2 Violins in D Minor, BWV 1043, Vivace (Gewandhausorchester

Leipzig, Christian Gansch), "Bach's Lunch," Variations on Themes by J.S. Bach (Turtle Island String

Quartet), Snow What (Turtle Island String Quartet), Deconstructing Johann (King's Singers), Improvisation on "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" (Bobby McFerrin/Jacques

Loussier Trio), Orchestra suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068, Gavotte (Jacques Loussier Trio), "Tocatta & Funk & Choral" (Quintessence Saxophone Quintet), "Seven Steps to Bach" J.S. Bach/Miles Davies (Turtle Island String Quartet), Orchestra Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067, Menuet/Badinerie (Jiri Stivin/

Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Christian Gansch), "Jazz Medley," Part A (Jiri Stivin & Collegium Quodlibet), "jazz Medley," Part B (Jiri Stivin & Collegium Quodlibet), "Improvisation" (Bobby McFerrin), Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, BWV 1054, Allegro (Jacques Loussier Trio), Orchestra Suite no. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068, Gigue; End Credits

4602d | DVD | $22.98 | A Cappella Vocal Jazz DVDs

Bobby McFerrin : Charts Package

Review: Without a doubt one of the most popular songs of the 20th century, "Don't Worry, Be Happy" is re-created here in an exact transcription of the Bobby McFerrin's original hit recording from the album "Simple Pleasures." 3 Soprano parts, 2 Alto parts, and a very hip Bass line back up the soloist or soloists of your choice - a cappella. Great fun to sing and to hear! A reverent and truly beautiful rendition of the widely known "23rd Psalm," this piece is frequently used in religious services. It's pace is slow and contemplative, and the music enhances the beauty of the language. As recorded on Bobby's "Medicine Music" CD. In "Grace," alto, tenor, and bass voices suggest the chant-like song of a carillon while the sopranos create a rhapsodic melody. This meditative score is enhanced with rhythmic breathing and optional parts for two cellos or cello section. Transcribed from "Hush," Bobby's duo album with Yo-Yo Ma. Each of Bobby's arrangements comes with extensive performance notes. With text adapted from the Book of Matthew, "Manna" provides a simple refrain with wonderfully textured variations that bring light to the thought "Whoever believes in Me will live forever." "Manna" includes a through-composed piano part as an additional color in the ensemble. "Come to Me" is rhythmic music full of life, freedom, and joy. An up-tempo piece to make everyone feel good, "come to me" with text adapted from the Book of John, includes parts for vocal percussion, body percussion, and handclaps. As recorded on Bobby's "Simple Pleasures" CD.

Songlist: knickknack, Don't Worry Be Happy, Grace, 23rd Psalm, Manna, Come to Me

https://www.okayplayer.com/news/bobby-mcferrin-questlove-blue-note-jazz-fest-interview.html

The Okayplayer Interview: Bobby McFerrin Speaks On Human Orchestras, Hip-Hop + Collaborating w/ Questlove

by Eddie "STATS"

Imported from Detroit.

June 13, 2014

This Friday June 13th Bobby McFerrin will join our own Questlove onstage at NYC’s Town Hall for a special live collaboration called Mumbo Jumbo curated by Jill Newman productions as part the Blue Note Jazz Festival. It is not clear at all what will transpire when the reigning master of drums meets the inventor of the Voicestra–probably not even to the select few who’ve seen them mess around before–but it is guaranteed to be amazing. If you are not familiar with the vocal virtuosity of Mr. McFerrin (perhaps you thought he was just the “Don’t Worry Be Happy” Guy?) he is an incredibly versatile composer and improviser who has collaborated with everyone from Pharoah Sanders, Herbie Hancock & Grover Washington, Jr on the one hand, to Gal Costa and Bela Fleck on the other…to En Vogue on the third hand (because, musically speaking, Bobby McFerrin has at least three hands). We couldn’t resist the opportunity to pick the mind of McFerrin on the hip-hop aspects of his human orchestrations, his musical progeny and his recent tour of Brazil. Read below and be sure to check out the one-of-a-kind show on Friday–who knows? Bobby may even select you as his instrument.

OKP: What exactly can we expect from you live collaboration with Questlove on Friday? Specifically what will the onstage setup to look like, as contrasted with your other performances?

Bobby McFerrin: I’m pretty sure at least there will be a drum kit for him and a microphone for me. This will be a full-on adventure, more like what I do in my solo shows [than the current Spirityouall tour, which incorporates a full band]–where I never know what’s gonna happen next.

OKP: What was the duet with Jimmy Fallon on your recent Tonight Show appearance like?

BMF: Silly and fun. He’s really musical and game.

OKP: You have worked with a pretty insane range of collaborators over your career–is there a secret to successful collaboration?

BMF: Listen to each other and have fun. Listen for the surprises.

OKP: You are well known for using an electro-acoustic approach to vocals, essentially accompanying yourself by building up multi-tracked or sampled layers as suggested by the term ‘Voicestra’. Have any of the younger musicians working in that vein (Tune-Yards; Tanya Auclair, Moses Sumney) caught your ear?

BMF: Interesting that you brought up Voicestra, which is a live performance ensemble featuring 12 voices, no electronics or multi-tracking, all improvised. That’s very different from multi-tracking in a studio situation. For me multi-tracking has been a great way to get what’s in my head to happen in real time. I confess that though I’m an open-minded type and love to interact with other musicians, I’m so focused on trying to get the music I hear in my head out where other people can hear it that I don’t listen to a lot of new music, and I haven’t heard of these new artists. I’m pretty introspective, but I’m not the analyzing, musicological type.

OKP: On a related note: what do you think of beatboxing, another type of ‘human orchestra’?

BMF: For me melody, harmony and rhythm are all wrapped up together, so I think of myself more as a singer who uses some percussion sounds and techniques than as a beatboxer. It’s been fun to see that community grow, so many people have great skills. When I meet them I encourage them all to sing too.

OKP: Have you and Chuck D ever had the chance to clear the air over his lyric (rapped on Public Enemy’s “Fight The Power”) which ran “‘Don’t Worry Be Happy’ was the #1 jam / Damn, if I say it, you can slap me right here…”? Did that experience sour you in any way towards hip-hop in general?

BMF: You should ask my son Taylor about me and hip-hop! I’m a pretty conservative guy in some ways, I don’t like cursing or violent talk in music–and I had a few things to say about a lot of what he was listening to as a teenager. But in the end I respect what shaped Taylor as a musician. I want my kids and all the young musicians out there to have the chance I had — to absorb a lot of influences and let them play together in my head.

OKP: We imagine you must be very proud of your kids’ musical endeavors, namely Cosmodrome in Madison‘s case and Taylor’s new LP Early Riser on Brainfeeder. We understand Madison has joined you on tour…can we look forward to any other cross-generational McFerrin collaborations in the near future?