SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BAIKIDA CARROLL

(September 3-9)

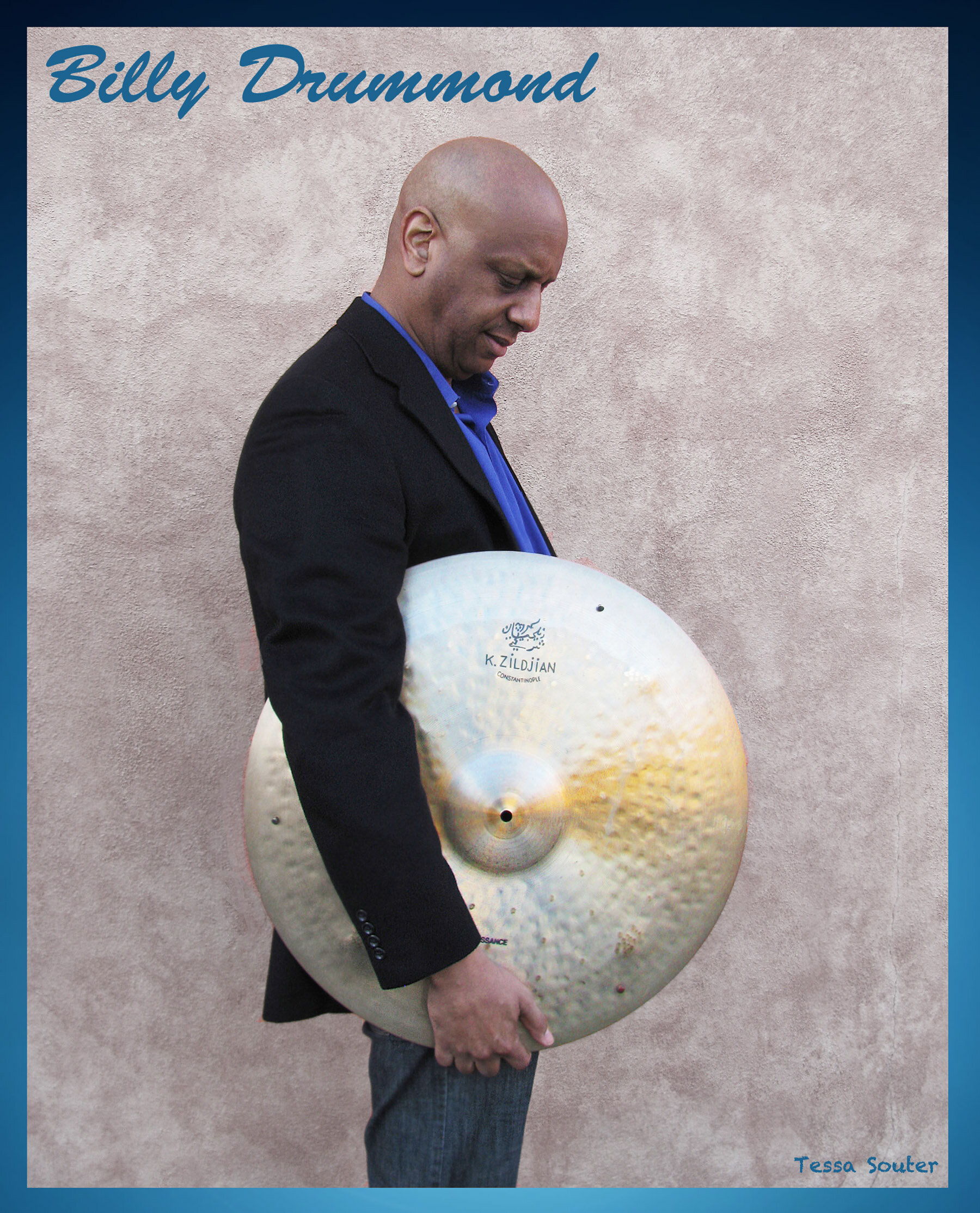

BILLY DRUMMOND

(September 10-16)

BOBBY MCFERRIN

(September 17-23)

ALBERT KING

(September 24-30)

ZENOBIA POWELL PERRY

(October 1-7)

DEAN DIXON

(October 8-14)

DOROTHY DONEGAN

(October 15-21)

BOBBY BLUE BLAND

(October 22-28)

CLORA BRYANT

(October 29-November 4)

CARLOS SIMON

(November 5-11)

VALERIE CAPERS

(November 12-18)

ROLAND HAYES

(November 19-25)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/billy-drummond-mn0000767592/biography

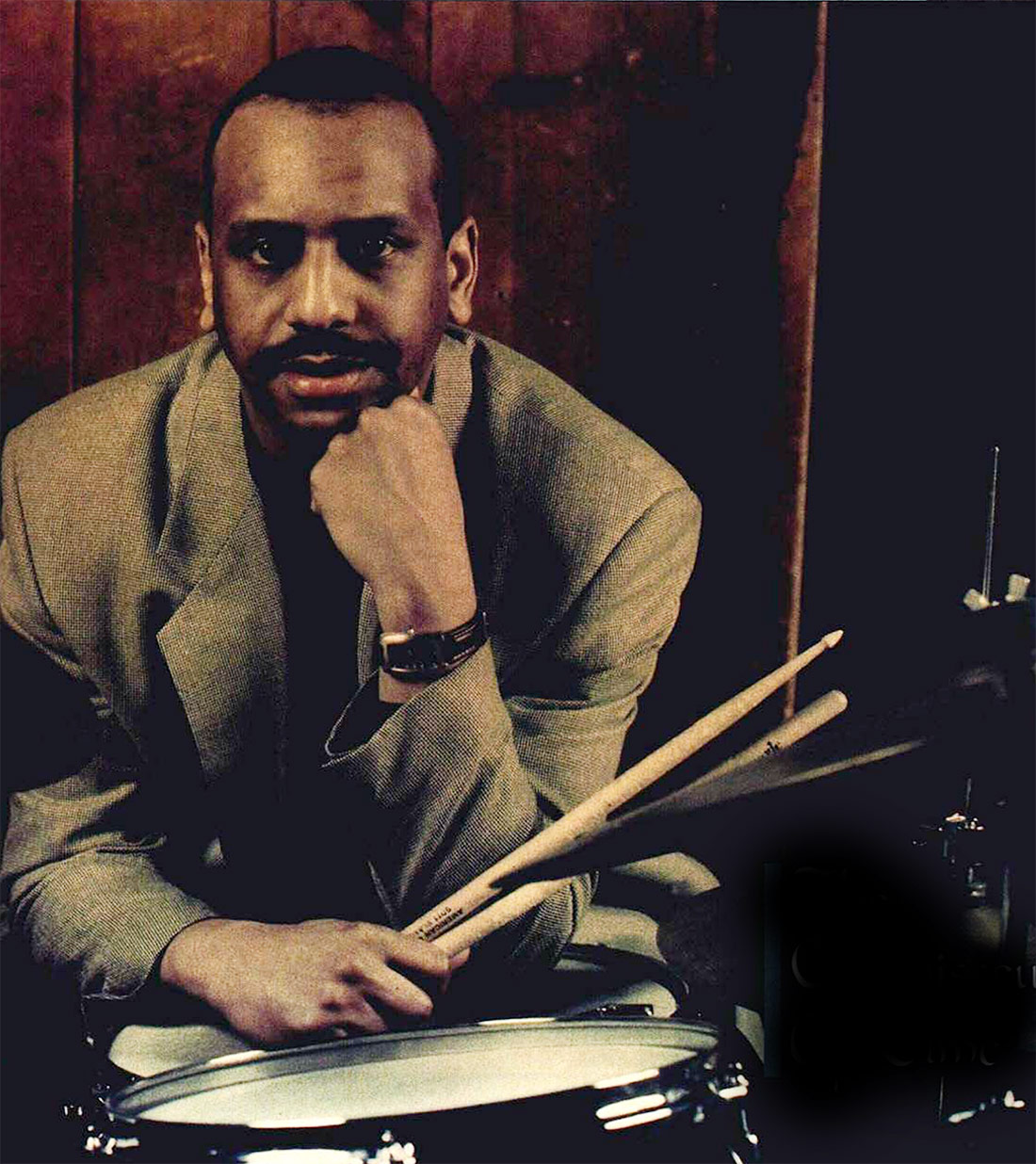

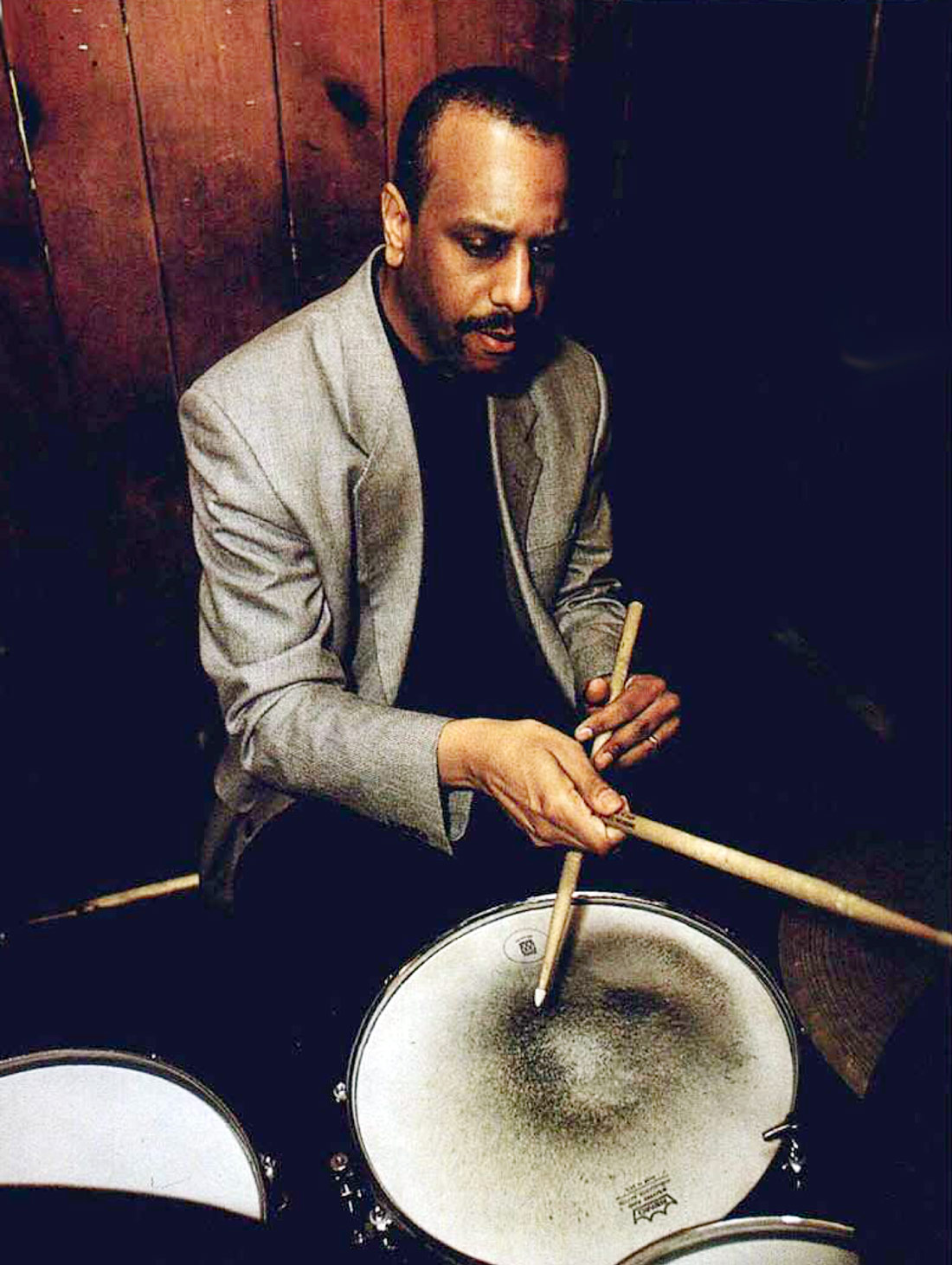

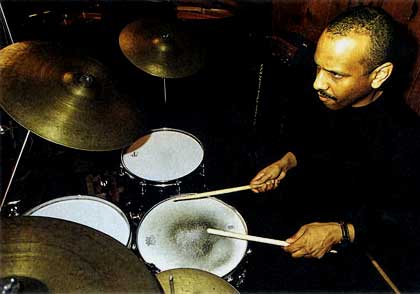

Billy Drummond

(b. June 15, 1959)

Biography by AllMusic

Drummond began playing drums at the age of four, following the example

of his drummer father. He played in high school and local bands and

thanks to hearing his father’s record collection began taking an

interest in the masters of modern jazz. In his teens he attracted

attention in New York and became one of several young musicians recorded

by Blue Note Records in their series of bands named Out Of The Blue.

He became a member of Horace Silver’s band, thereafter touring and

sometimes recording with artists including Sonny Rollins, Pat Metheny,

J.J. Johnson, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Tommy Smith, Vincent

Herring, Jon Faddis and Renée Rosnes. He has played on several records

with the latter and she plays in his band, Native Colours, which also

includes Steve Wilson. An exceptionally accomplished technician,

Drummond is a highly supportive player, always listening and eager to

bring out the best in the musicians he accompanies.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/billy-drummond

Billy Drummond

Acclaimed by Downbeat as “one of the hippest bandleaders now at work,” Billy Drummond’s thrilling, powerful and highly musical playing has also made him one of the most called-for sidemen of his generation. Mentored in the bands of jazz legends Horace Silver, Joe Henderson, Bobby Hutcherson, J J Johnson and Sonny Rollins, Drummond is now widely acknowledged as one of today’s most versatile drummers, making sideman appearances with a veritable who’s who of jazz greats on over 350 albums. He has made three albums as a leader—including Dubai, a New York Times Number 1 Jazz Album of the Year—and five as a co-leader, including We’ll Be Together Again in Three’s Company, a trio with Javon Jackson and legendary bassist Ron Carter, which made several Top Ten lists of the Year. Modern Drummer magazine recently honored Dubai as one of the 50 Crucial Jazz Drumming Recordings of the Past 100 Years—”distilling to only 50, a century’s worth of drumming on jazz recordings, which by any reasonable guess would comprise tens if not hundreds of thousands of titles.”

Born in Newport News, Virginia, where he grew up listening to his father’s extensive jazz record collection, Drummond was leading his own bands from the age of eight, and teaching adults from the age of just 14, before going on to study classical percussion at the Shenandoah Conservatory of Music. In the late 1980s, he was encouraged by Al Foster to move to New York, where he was almost immediately recruited to the young band Out of the Blue (OTB), recording Spiral Staircase for Blue Note Records. When OTB disbanded, Billy joined Horace Silver’s Sextet, simultaneously starting life-long associations with Buster Williams and Bobby Hutcherson, and subsequently joining J J Johnson’s band, followed by a three-year stint touring with Sonny Rollins.

Since then, Drummond has performed and recorded with many of the world’s jazz greats, including Horace Silver, Joe Henderson, Bobby Hutcherson, Buster Williams, Steve Kuhn, JJ Johnson, Sonny Rollins, Charles Tolliver, Nat Adderley, Charles McPherson, Eddie Henderson, James Moody, Sheila Jordan, Andrew Hill, Ron Carter, Carla Bley, Eddie Gomez, Larry Willis, Hank Jones, Freddie Hubbard, Lee Konitz, Stanley Cowell, Archie Shepp, Joe Lovano, Javon Jackson, Chris Potter, Eric Reed, Ralph Moore, Vincent Herring, Franco Ambrosetti (Italy), Karin Krog (Norway), Sadao Wantanabe (Japan), Toots Thielemans (Belgium), Barney Wilen (France), Laurent DeWilde (France), Jan Lundgren (Sweden), and Michel LeGrand (France).

“I consider myself very fortunate to have come up playing with some of the innovators of jazz who, in many instances, helped shape the way this music is and will always be played,” says Drummond.

“Priceless experience for a young person learning how to be a musician. They taught me how to be a professional – to know the material, to be on time and, most of all, to play from your heart.” In addition, Drummond is a highly respected educator who has taught some of the current generation’s best young drummers while juggling a busy touring schedule with his duties as Professor of Jazz Drums at the Juilliard School of Music and NYU. He also gives private lessons and master classes—via Zoom and in-person—all over the world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Drummond

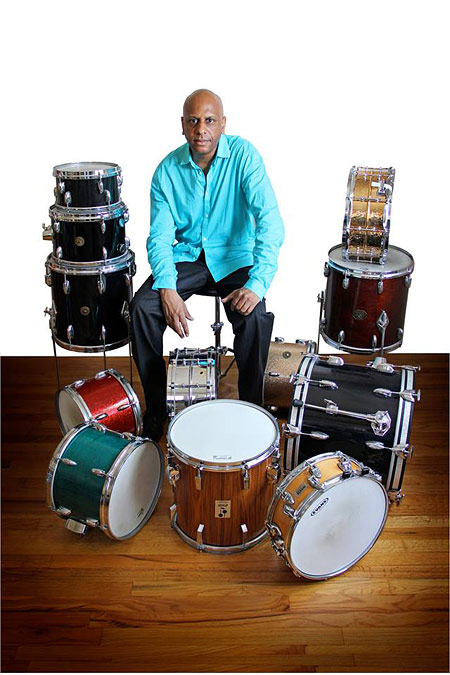

BILLY DRUMMOND IN 2008

Willis Robert "Billy" Drummond Jr. (born June 19, 1959) is an American jazz drummer.

Early life

Billy Drummond was born in Newport News, Virginia, where he grew up listening to the extensive jazz record collection of his father, an amateur drummer and jazz enthusiast. He started playing the drums at four and was performing locally in his own band by the age of eight, and playing music with other kids in the neighborhood, including childhood friends Victor Wooten and his brothers,[1] who lived a few doors away and through whom he met Consuela Lee Moorehead, composer, arranger, music theory professor, and the founder of the Springtree/Snow Hill Institute for the Performing Arts. He attended Shenandoah College and Conservatory of Music on a Classical Percussion scholarship and, upon leaving school, became a member of a local Top 40 band called The Squares with bass phenom Oteil Burbridge.[2]

Career

In 1986, encouraged by Al Foster, who had invited him to sit in at the Village Vanguard and advised him to take the next step, he moved to New York and almost immediately joined the band, Out of the Blue, with whom he recorded their last album, Spiral Staircase (Blue Note Records). A year later, he joined the Horace Silver sextet, touring extensively with him before becoming a member of Sonny Rollins's band, with whom he toured for three years. During this period he also formed long-term musical associations with Joe Henderson, Bobby Hutcherson, Buster Williams, James Moody, JJ Johnson, Andrew Hill, and others.

He has made three albums as bandleader, including his Criss Cross album Dubai (featuring Chris Potter, Walt Weiskopf and Peter Washington), which included in the list of “50 Crucial Jazz Drumming Recordings of the Past 100 Years” by Modern Drummer magazine.[3] He has made five albums as a co-leader, including We’ll Be Together Again with Javon Jackson and Ron Carter. He leads a New York-based band called Freedom of Ideas. In addition to touring he is Professor of Jazz Drums at the Juilliard School and New York University.

A sideman on over 350 records, Drummond has played and recorded with, among others, Bobby Hutcherson, Nat Adderley, Ralph Moore (1989 and subsequently), Buster Williams (1990–93), Charles Tolliver (1991), Lew Tabackin and Toshiko Akiyoshi, Hank Jones (1991), James Moody (early 1990s), Sonny Rollins, Andy LaVerne (1994), Lee Konitz (1995), Dave Stryker (1996), George Colligan (1997), Ted Rosenthal, Bruce Barth, Joe Lovano, Andrew Hill (from 1997 to 2000), Larry Willis (2006 to the present), Toots Thielmans, Freddie Hubbard (mid-1990s), Chris Potter, Eddie Gómez, Stanley Cowell, Javon Jackson, and Sheila Jordan (1990s to present). He is a long-time member of Carla Bley's Lost Chords Quartet, Sheila Jordan's Quartet, and the Steve Kuhn Trio.

Formerly married to pianist Renee Rosnes, Drummond has been a resident of West Orange, New Jersey.[4]

Discography

As leader

- 1991 Native Colours (Criss Cross)

- 1993 The Gift (Criss Cross)

- 1995 Dubai (Criss Cross)

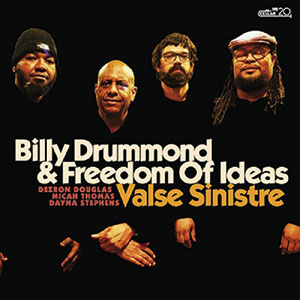

- 2022 Valse Sinistre (Cellar Live)

As co-leader

- 2003 Pas de Trois The Drummonds

- 2006 Mysterious Shorter Nicholas Payton/Bob Belden/Sam Yahel/Billy Drummond/John Hart

- 2006 Once Upon a Time The Drummonds

- 2006 Letter to Evans The Drummonds

- 2006 Beautiful Friendship The Drummonds

- 2016 Three's Company Ron Carter/Javon Jackson/Billy Drummond

With OTB

- 1989 Spiral Staircase Out of the Blue

With Nat Adderley

- The Old Country (Alfa, 1990)

With Carla Bley

- 2003 Looking for America

- 2004 The Lost Chords

- 2007 The Lost Chords find Paolo Fresu

- 2008 Appearing Nightly

With Steve Kuhn

- 1997 Dedication (Reservoir)

- 1998 Countdown (Reservoir)

- 2000 The Best Things (Reservoir)

- 2001 Temptation

- 2002 Waltz – Red Side

- 2002 Waltz – Blue Side

- 2004 Easy to Love

- 2007 Pastorale

- 2007 Baubles, Bangles and Beads

- 2007 Pavanne for a Dead Princess

- 2010 I Will Wait for You

As sideman

- Old Country (1990) with Nat Adderley

- Sam I Am (1990) with Sam Newsome

- In New York (1990) with Tomas Franck

- For the Moment (1990 with Renee Rosnes

- Mirage (1991) with Bobby Hutcherson

- Hornucopia (1991) with Jon Faddis

- John Swana and Friends (1991) with John Swana

- Mirage (1991) with Bobby Hutcherson

- Better Times (1992) with Rob Bargad

- The Charmer (1992) with Charles Fambrough

- Epistrophy (1992) with Bill Pierce

- Simplicity (1992) with Walt Weiskopf

- Without Words (1992) with Renee Rosnes

- Dawnbird (1993) with Vincent Herring

- Secret Love (1993) with Vincent Herring

- Blue Note Years (1993) with Joe Henderson

- Feeling's Mutual (1993) with John Swana

- Scheme of Things (1993) with Scott Wendholt

- In from the Cold (1994, Criss Cross) with Jonny King

- Days of Wine and Roses (1994) with Vincent Herring

- Dearly Beloved (SteepleChase, 1996) with Lee Konitz

- Notes from the Underground (1996, Enja) with Jonny King

- Bluesology with George Cables (SteepleChase, 1997)

- Out of Nowhere with Lee Konitz and Paul Bley (SteepleChase, 1997)

- RichLee! with Lee Konitz and Rich Perry (SteepleChase, 1997)

- Light Breeze with Franco Ambrosetti (Enja, 1998)

- True Blue (1998) with Archie Shepp

- Vertigo (1998) with Chris Potter

- Universal Spirits (1998) with Tim Ries

- Dusk (1999) with Andrew Hill

- Duke's Place (1999) with George Mraz

- Art & Soul (Blue Note, 1999) with Renee Rosnes

- Everything I Need (1999) with Carol Fredette

- Out of the Dark (1999) with Andy Fusco

- Pleasant Valley (1999) with Javon Jackson

- Reemergence (1999) with Eddie Henderson

- Remembrance (1999) with Sadao Watanabe

- Rendezvous (1999) with Jerome Harris

- Search (1999) with Joel Weiskopf

- Sound of Love (1999) with Tommy Smith

- Navigator (2000) with Joel Frahm

- Ask Me Now (2000) with Michael Urbaniak

- Siren (2000) with Walt Weiskopf

- Steal the Moon (2000) with Carolyn Leonhart

- Two Tenor Ballads (2000) with Mark Turner and Tad Shull

- What Goes Unsaid (2000) with Scott Wendholt

- This Will Be (2001) with Chris Potter

- Oasis (2001) with Eddie Henderson

- Song (2001) with Marty Ehrlich

- Workin' Out (2001) with John Campbell

- Cedars of Avalon (2001) with Larry Coryell

- Alternate Side (2001) with Tim Ries

- With a Little Help from My Friends (2001) with Renee Rosnes

- Deja Vu (2001) with Archie Shepp

- Waltz for Debbie (2002) with David Hazeltine

- Wurd on the Skreet (2002) with Donald Brown

- Life on Earth (2003) with Renee Rosnes

- Line on Love (2003) with Marty Ehrlich

- Little Song (2003) with Sheila Jordan

- Strings (2003) with Jim Snidero

- French Ballads (2003) with Archie Shepp

- Deja Vu (2003) with Archie Shepp

- The Lost Chords (2003) with Carla Bley

- Dream Dancing (2004) with Steve Kuhn

- Close Up (2004) with Jim Snidero

- Tea for Two (2004) with Walt Weiskopf/Andy Fusco Quartet

- Sight to Sound (2004) with Walt Weiskopf

- Winter Sonata (2004) with Gary Versace

- Cleopatra's Dream (2006) David Hazeltine

- Manhattan (2006) David Hazeltine/George Mraz Trio

- Pastorale (2007) with Steve Kuhn

- Baubles, Bangles and Beads (2007) with Steve Kuhn

- Pavanne for a Dead Princess (2007) with Steve Kuhn

- The Lost Chords Find Paolo Fresu (2007) with Carla Bley

- New Conversations (2007) with Carla Bley

- Blue Fable (2007) with Larry Willis

- Nights of Key Largo (2008) with Tessa Souter

- Moon River (2008) with Nicki Parrott

- The Offering (HighNote, 2008) with Larry Willis

- Once Upon a Melody (2008) with Javon Jackson

- Beautiful Love: The NYC Session (2008) with Al Di Meola, Eddie Gómez, Yujata Kobaya

- Appearing Nightly (2008) with Carla Bley

- Art of Organizing (2009) with Dr. Lonnie Smith

- Chick Corea Songbook (2009) with The Manhattan Transfer

- Mutual Admiration Society (2009) with Joe Locke/David Hazeltine

- New Moon (2009) with Ron McCLure

- Mays at the Movies (2009) with Bill Mays

- Crossfire (2009) with Jim Snidero

- One Night at the Kitano (2009) with Jed Levy SteepleChase

- Fly Me to the Moon (2009) with Nicki Parrott

- Mays at the Movies (2009) with Bill Mays

- The Decider (2009) with Peter Zak

- All My Friends are Here (2010) with Arif Mardin compilation

- I Will Wait for You (2010) with Steve Kuhn

- Invitation (2010) with Beat Kaestli

- Cedar Chest (2010) The Music of Cedar Walton compilation

- For All We Know (2010) with Eddie Henderson

- New York Encounter (2010) with Yakov Okun Trio

- Steeplechase Jam Session Volume 29 (2010) Andy Laverne SteepleChase

- Steeplechase Jam Session Volume 30 (2010) Don Braden SteepleChase

- Dedication (2010) with Ron McClure (2010) SteepleChase

- Live at Smalls (2011) with Tim Ries

- Live at Smalls (2011) with Jesse Davis

- Beyond the Blue (2012) with Tessa Souter

- Home Tone (2012) with Tony Lakatos

- Nordic Noon (2012) with Peter Zak SteepleChase

- Jazz in the New Harmonic (2013) with David Chesky

- The Eternal Triangle (2013) with Peter Zak SteepleChase

- Homeland (2014) with Vincent Hsu

- Are You Real (2014) with Stanley Cowell SteepleChase

- Leap of Faith (2015) with Burak Bedikyan SteepleChase

- Primal Scream (2015) with David Chesky

- Rambling Confessions (2015) with John Hebert

- Sing to the Sky (2015) with Emma Larsson

- Tales, Musings, and Other Reveries (2015) with Jeremy Pelt

- Reminiscent (2015) with Stanley Cowell SteepleChase

- Standards (2016) with Peter Zak SteepleChase

- En Rouge (2016) with Atlantico (Dave Schroeder/Sebastien Paindestre)

- Jive Culture (2016) with Jeremy Pelt

- Whirlwind (2016) w/ Andy Fusco SteepleChase

- With Due Respect (2016) w/ Freddie Redd SteepleChase

- En Rouge (2016) w/ Atlantico* Inside the Moment (2017) w/ Camille Thurman

- Live and Uncut (2017) w/ Mark Whitfield

- Cities Between Us (2017) w/ Allegra Levy SteepleChase

- No Illusions (2017) Stanley Cowell SteepleChase

- The Pendulum (2017) w/ Mike Richmond SteepleChase

- Picture in Black and White (NOA, 2018) w/ Tessa Souter

- Jubilation (2018) w/J im Snidero and Jeremy Pelt

- Trio in the New Harmonic: Aural Paintings (2018) w/ David Chesky

- Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk (Sunnyside, 2018) w/ Frank Kimbrough

- NYCD: A Tribute to Art Van Damme (2018) w/ Pierre Eriksson

- Out in the Open (2018) w/ Sam Dillon

- New Easter Island (2019) w/ Atlantico

- One Mind (2018) w/ Peter Zak Quartet

- Tones for Joan’s Bones (2018) w/ Mike Richmond SteepleChase

- New Departure (2018) w/ Takayuki Yagi

- Playing Who I Am (2019) w/ Andrea Domenici

- New Easter Island (2019) w/ Atlantico

- Friday the 13th (Steeplechase, 2020) w/ Stephen Riley

- Jazz Dance Suites (Chazz Mack Music, 2020) w/ Charles McPherson

- Kimbrough (Newvelle, 2021) A tribute album to Frank Kimbrough featuring 67 artists curated by Elan Mehler

- Early Spring (Steeplechase, 2021) w/ Anthony Ferrara

- On the Move (Stunt, 2021) w/ Gabor Bolla

Sources

- Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz. Oxford, 1999, p. 154.

- Gary W. Kennedy, "Billy Drummond". Grove Dictionary of Jazz online.

https://jazztimes.com/features/profiles/overdue-ovation-billy-drummond-true-chameleon-professional/

Overdue Ovation: Billy Drummond, True Chameleon and Professional

A look back at the drummer's four-decade career

At 62, Billy Drummond has certainly earned the title of elder statesman, though the sobriquet in this case has little to do with lifespan. Chalk it up to experience—he’s been playing since he was four, and has accumulated well over 350 album credits—and to his influence as an educator through his tenures at Juilliard and NYU. In that role he serves as a conduit for some of the music’s defining voices, having played with such legendary figures as Horace Silver, Sonny Rollins, Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Henderson, and J.J. Johnson.

Still, the unassuming drummer hardly plays the role of sage on high. “The older you get, the less you know,” he insists with a laugh, over Zoom from his home in West Orange, New Jersey. “I wish I could go back and [relive those experiences] with this headspace. When you’re involved in something like that, you’re not necessarily thinking about the historical importance of the person you’re playing with—you’re just involved in the work. But later on you look back and realize, ‘Pinch me, I’m dreaming.’”

Humility aside, Drummond’s playing has been a dream come true for countless bandleaders over the past three-and-a-half decades. He plays with a quiet authority, akin to the radiant strength of someone who can command the attention of a room without saying a word. The potential for ebullient swing is ever present, and occasionally bursts joyously forth, though never in quite the form one might expect. But Drummond’s focus tends more toward nuance and dynamics, which has made him an attractive collaborator for some of jazz’s most idiosyncratic voices, including Andrew Hill and Carla Bley. He’s a chameleon in the true sense: one whose colors change to fit the situation while his essence remains the same.

“I’ve come to believe that ultimately a musician’s value resides in his or her values,” wrote bassist Steve Swallow, who’s played alongside Drummond in Carla Bley’s Lost Chords and Remarkable Big Band. “Billy Drummond is a principled, compassionate man, and these attributes shine in his playing. Jazz drumming is rooted in cooperative ensemble playing; Billy’s impulse to serve the group makes his presence on any bandstand a reassurance and an inspiration. His devotion to the commonweal may not attract the attention of some critics and fans, but it moves the people he’s playing with deeply.”

If Drummond has been overlooked at times, it can be blamed in part on the scarcity of his work as a leader, limited at this writing to three releases on the Criss Cross label between 1991 and 1996. But if all goes according to plan (never a given in this age of viruses and variants), the appearance of this story will coincide with Drummond’s long-overdue return to the studio with his Freedom of Ideas quartet.

Drummond has been leading versions of Freedom of Ideas for the last decade; when he convenes the band in the late Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, N.J., in November it will consist of saxophonist Dayna Stephens, pianist and former student Micah Thomas, and bassist Dezron Douglas, a mainstay of the band since its formation.

“It’s called Freedom of Ideas for a reason,” Douglas says. “Billy’s a great composer and hears melody almost in a classical sense. He can swing his ass off, but he’s hearing the combination of classical with modern harmony. His tunes always have the same DNA. He brings in beautiful music, but that’s just the beginning. We take it everywhere.”

“I want it to be as democratic and as open as possible,” Drummond explains. He credits Wayne Shorter with inspiring the group’s name, drawn from an interview referring to Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet. “Miles let everybody in the band be who they were and play the way that they play. Miles being who he was, he was still the leader, but he wasn’t putting the handcuffs on anybody. I see any band that I would lead as a complete open book. Let’s play as open and as true to character as possible while not sacrificing the musical integrity.”

It’s as near to true as can be that Billy Drummond was born with drumsticks in his hands. His father was an avid jazz fan and amateur drummer who clearly passed his enthusiasm on to his son. “I never fancied the idea of being a fireman or an astronaut or any of those things that little kids say they want to be when they grow up,” Drummond says. “I had that figured out. I was lucky, because some people live their whole lives and haven’t figured that out. So I feel blessed that I knew what I wanted to do and even more blessed to have been able to do it all this time.”

Growing up in Newport News, Virginia, Drummond found himself surrounded by talented young musicians (including the Wooten brothers) and older hobbyists with whom he could hone his craft in neighborhood garages. At the same time, he was playing in school bands and in the pit for drama department productions; he went on to study at Shenandoah Conservatory as a classical percussion major.

Throughout his college years Drummond moonlighted with the Squares, a Top 40 band that covered the hits of the day in several local dance clubs. The gig funded regular visits to New York City and eventually, in 1986, a move to the city encouraged by newfound mentors like Al Foster and Art Blakey.

Shortly after his arrival he joined a group of then-rising peers in Out of the Blue, just in time to record the group’s final album, Spiral Staircase. In parallel, a call from Horace Silver to join the legendary pianist’s sextet led to his association with a number of iconic figures, including a three-year stint touring with Sonny Rollins.

“Just hearing Sonny play is enough to inspire you,” Drummond says. “That’s like going to the mountaintop, and I’ve been fortunate enough to share music with a long list of these people on a regular basis. Bobby Hutcherson, Steve Kuhn, Andrew Hill, Ron Carter—we’re talking about people that shaped this music. That’s the true mark of greatness: If you take them out of the equation, everything shifts and music would not be the same. There’s not too many people you can say that about.”

In 1991 Drummond made his leader debut with Native Colours, a quintet featuring Out of the Blue bandmates Steve Wilson on sax and then-wife Renee Rosnes on piano, along with vibraphonist Steve Wilson and bassist Ray Drummond (unrelated, though he would go on to form a collective called the Drummonds with Billy and Rosnes).

The Gift followed in 1993 with Rosnes, saxophonist Seamus Blake, and bassist Peter Washington, and then the stellar Dubai two years later, featuring a chordless two-tenor quartet with Washington, Chris Potter, and Walt Weiskopf. “A lot of the drummer-led bands that influenced me didn’t have a piano or guitar,” Drummond says, citing the likes of Max Roach, Elvin Jones, and Tony Williams. “I like that openness. There’s that word ‘freedom’ again. You play a little bit differently because there’s so much space there.”

Despite the acclaim with which Dubai was met, it marked the last time to date that Drummond would serve as sole leader on a recording date until this November (fingers crossed). The Drummonds released four albums as a collective; in 2006 Drummond joined Nicholas Payton, Bob Belden, Sam Yahel, and John Hart for the Mysterious Shorter tribute date; and in 2016 he co-headlined with Ron Carter and Javon Jackson as Three’s Company on the intimate We’ll Be Together Again.

“I see any band that I would lead as a complete open book.”

Glancing over Drummond’s discography, though, it almost seems like he’s simply been too busy to do his own thing. He’s recorded and toured constantly over the past 25 years in a staggering variety of settings. Whether navigating the eccentric contours of Carla Bley’s compositions or the quirky bop angles required by accompanying Sheila Jordan; providing a foundation for Steve Kuhn’s Evans-inspired piano trio without shattering its gorgeous fragility or propelling the individualistic swing of the late Stanley Cowell; or in countless other, vastly different situations, he’s always identifiably himself while always providing exactly what the moment requires to create captivating music.

“If someone calls me, my job is to bring their music to fruition as best I can,” Drummond insists with an enormous degree of understatement. “If they have detailed instructions, I try to use whatever musical craftsmanship I have to help them with that. But most of them don’t say anything. I think if they see something in you, they let you do what you do and probably have confidence in the fact that you’re going to be a professional. They do what I would do: pick people that have the same musical integrity and abilities that you do and it’ll take care of itself.”

Recommended Listening

Billy Drummond Quintet: Native Colours (Criss Cross, 1991)

Billy Drummond: Dubai (Criss Cross, 1995)

Andrew Hill: Dusk (Palmetto, 2000)

Carla Bley: The Lost Chords (Watt/ECM, 2004)

Steve Kuhn: Pastorale (Sunnyside, 2007)

Three’s Company: We’ll Be Together Again (Chesky, 2016)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Shaun Brady is a Philadelphia-based journalist who covers jazz along

with an eclectic array of arts, culture, and travel. Brady contributes

regularly to the Philadelphia Inquirer and JazzTimes and Jazziz magazines, with subjects ranging from legendary artists to underground experimentalists. His byline has appeared in DownBeat, Metro, NPR Music, and The A.V. Club, among other outlets. He studied filmmaking at Columbia College Chicago and continues to spend too much time in the dark.

https://www.stereophile.com/content/musicians-audiophiles-billy-drummond

Interviews

Musicians as Audiophiles: Billy Drummond

Billy is Professor of Jazz Drums at Juilliard and NYU, and he also accepts students at home. After lessons he often invites students to hear vinyl on his Basis Audio turntable, Audio Research amplification, and Magnepan speakers setup. The visiting 20-year-olds are often as confused as they are impressed.

"I've had students listen to my stereo," Drummond explains, "and when I flip the record over they ask 'Why are you doing that?' I say 'To play the other side.'

They reply "What? What 'side'? That doesn't make any sense."

I have to explain to them that a record has two sides, "A and B."

"But can't you just . . .?"

"No. You can't just push a button. You have to flip the record over."

Drummond has recorded three albums as a leader (Native Colours, The Gift, Dubai; all Criss Cross Records), ten as a co-leader, and at least 300 albums as a sideman, including Stereophile's first jazz album, Rendezous (now out of print, though one track, "The Mooche," can be found on Editor's Choice). When not recording (often at David Chesky's studio in New York) or touring globally with Steve Kuhn, Eddie Henderson, Stanley Cowell or his own group, Drummond can be heard performing locally in the Tri-State area.

Drummond's basement studio is chock-full with snare drums and cymbals—three of his prized ride cymbals bear the autographs of his heroes: Max Roach, Jack DeJohnette, and Tony Williams. Also in Drummond's studio lair, framed photos of historic rhythm masters look out over two well-used Gretsch drum sets.

Back upstairs in an unused bedroom, one of Drummond's stereo systems is literally two rigs functioning as one, with two different front ends powering Magnepan MG1.6/R speakers. Drummond's basement was flooded in early 2016, so he merged two systems together (a pair of Snell monitors remains downstairs).

Part one of the bedroom system includes the following source components: Technics SL-1200 Mk.2 Anniversary Gold Turntable with Audio Technica AT120ET cartridge; Sony SCD-CE775 SACD changer; Sony CD/recorder; Oppo DV-980H Universal Player; and California Audio Labs Sigma II tube DAC. An Audible Illusions Modulus 3A preamplifier feeds Quicksilver V4 Mono Amplifiers. Kimber, Straight Wire, AudioQuest, and Nordost comprise cabling; AudioPrism Ground Control and Tripplite, Adcom and Monster Power handle line conditioning.

In the second part the bedroom system, components include a Basis 1400 turntable/Rega RB300 arm/Ortofon Quintet Blue cartridge to the Audible Allusions Modulus 3A preamplifier and Audio Research 150.2 stereo power amp. Digital is handled via PS Audio Digital Link III DAC, Audio Research CD-1 CD player, and Sony SCD-555ES SACD changer. Symposium Roller Blocks support the Audio Research components. Cabling from AudioQuest, Lifatec, SilverSmith, Straight Wire and LessLoss and a Shunyata Research Hydra 4 conditioner complete part two. Whew!

Listening to Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition (ECM), Barry Harris's At The Jazz Workshop (Riverside) or Paul Motian's Le Voyage (ECM) on the Basis turntable-fed system sounded shockingly good in the bedroom! Hearing DeJohnette's drumming through Drummond's large Maggies was a revelation. The speakers' excellent imaging, superb transparency, effortless speed and life-sized soundstage made these familiar recordings a fresh listening experience. If Drummond ever tires of the music biz, he can put his meticulous tweaking skills to good work.

Guided by John Rutan of Verona, New Jersey's Audio Connection and StereoTimes's Clement Perry (a close neighbor), Drummond has successfully tweaked his systems, each decision impacting the sound quality. The sonic differences were palpable when switching between the Sony SACD and Audio Research CD players.

"On the Sony SACD player I'm using a Lifeatec TosLink cable to the DAC, and a Silversmith RCA cable from the Audio Research CD player to the DAC," Drummond explains. "The two sound very different. I like the attributes of the TosLink; it's a little bit faster because it's glass. The RCA cable is silver, so it's different-sounding again. And Lifeatec's cable is not that expensive, $70 a meter."

Why Maggies?

"They're open; they're fast; they're detailed," Drummond replies. "They have a huge soundstage; they image well; they're non-fatiguing. They don't have a box so they're not colored. They're dipoles, so they fire front and back.

"I like their speed for the drums," Drummond continues. "There's something special about the way a Magneplanar handles drums and cymbals. Maybe it's because the surface area is larger than a small cone. When you hear a drum through the Maggies you're hearing the drum. And because these are so fast they really get the cymbal sound right. That's been a key factor for me in choosing a speaker. If it doesn't get the cymbals right I'm not happy." (Laughs)

Billy, what is an audiophile and are you one?

"I don't know about all that!" he replied. "That's a name that somebody else gave people like us. I am someone who enjoys listening to music on high performance playback equipment. As opposed to someone listening to music on equipment that is not high performance and someone who might not be interested in extracting the most information the recording actually has on it. I am interested in that. I don't know what you call that. You can call that whatever you want." (Laughs)

Why are most musicians generally not audiophiles, or "high-performance playback" aficionados?

"Most musicians can get it without it being high-performance playback level," Billy says. "But most musicians that hear my rig are completely floored and want to get into it. I have turned students on to it; those are young people in their 20s. They're stunned hearing this. They're used to hearing music on earbuds or computer speakers. They have no clue; they've never experienced that connection to the physicality of the process. But at my place they get the bug."

In Drummond's living room, situated in front of wall-mounted photos of Billy with Sonny Rollins, Billy with Hillary Clinton, and Billy with President Obama, system two holds court.

Analog from Technics SL-1200 Mk.II turntable with Audio Technica MLA440 cartridge is contrasted by Pioneer/Oppo/Yamaha CD players signaling a MicroMega MyDAC, all into Audio Research SP16 preamplifier and Bryston 3B ST stereo power amp juicing Vandersteen 3A Signature loudspeakers. Straight Wire interconnects and speaker cables, Tempo Electric Big Twist Silver interconnects and Klee coaxial digital cable comprise connectors. Adept Response RPT 2 and Akiko Audio E-Tuning Gold Mk.II power conditioners and an Acoustic Revive RR-77 RR77 Schumann Resonator close system two. The sound here was extremely musical and warm, with no syrup in earshot!

Now to the dining area, where system three, "hobbled together from leftover pieces," includes Technics SP-10 turntable with Audiocraft tonearm, Pioneer DV45A Universal player, MSB Digital Link DAC, Nakamichi DR2 cassette player, NAD C370 integrated amplifier, Tannoy Reveal monitors and Vandersteen 2CE loudspeakers. System three, framed around Drummond's LP collection, played solid musical pleasure.

Billy, how does your inner audiophile influence your outer musician?

"I didn't say I was an audiophile!" Billy laughs. "But maybe it helps me to sonically hear the people that I am aspiring to be like or become musically. High performance playback equipment helps me get closer to my ideal. Aside from hearing the musicians play live—and there is nothing like the live performance—I can get closer when I extract the information from the disc or the records. Then I can hear clearly the sounds of these people playing their instruments. And that's something that I am in touch with. It's all about sound. We're trying to get the best sounds we can from our instruments. We like musicians for their unique and different sounds. I like being able to differentiate between those different sounds."

https://ecmreviews.com/2021/09/26/an-interview-with-billy-drummond/

An Interview with Billy Drummond

Billy Drummond took an interest in the drums as soon as he could pick up a pair of sticks. He seems predestined to have made a humble home for himself in the pantheon of the instrument, playing on over 350 recordings alongside such pillars as Horace Silver, Bobby Hutcherson and Sonny Rollins, among many others. His 1995 leader date, Dubai, was named a New York Times #1 Jazz Album of the Year. Before and since then, Drummond has contributed to projects too numerous to mention in full, including his “Freedom of Ideas” quartet, which is preparing to step into the studio. This will mark his first leader record in more than two decades, heralding a welcome return to the helm for this much sought-after musician. Most recently, he was invited by Gábor Bolla to join the Hungarian saxophonist’s own quartet under the auspices of the Copenhagen Jazz Festival, where a 10-day stint culminated in two days of recording. In this interview, we check in with Drummond to get his thoughts on the past, present and future.

Tyran Grillo: Did you ever have a “eureka” moment with the drums?

Billy Drummond: As soon as I discovered the drums, before I’d ever played with anybody, I knew that was what I wanted to do. It might seem fairytale-ish to people, but the only person I know that knew me before the drums is my older sister, Sheila, and I was just a toddler. That being said, I don’t remember my life prior to playing the drums.

TG: Does that mean you took to the drums naturally or did you struggle like everyone else?

BD: It may sound like a cliché, but you could say the drums chose me, or mutual love at first sight, I don’t know! Every instrument has its idiosyncrasies that have to be dealt with; that’s the nature of the beast. Brass musicians, for example, have to deal with their embouchure, which is a constant struggle no matter who you are. It’s a choice and depends on what you’re trying to achieve and bring to fruition. So, of course, I had struggles and still do. You’ve got prodigies like Buddy Rich. Then there’s Tony Williams, who played at a level that was quite remarkable at such a young age. But he also had an incredible work ethic and dedicated himself to emulating the drummers he loved and studied as much as he could about playing the instrument. There were a lot less options and distractions, especially during that time [the mid ’50s] to keep one from pursuing such passions once they were decided on. You could focus on one thing all day. By the time he was 18, he had become one of the very greats he aspired to be. And he wasn’t the only one. Think about others like Clifford Brown, who started later in life and developed rapidly. The challenges were there then and are still present today. It’s hard work and most musicians have to stay up on the instrument. At least I do. If I take a break, I’m reminded of it the next time I sit down and play. I tell all my students: practice now while you still can before all the obligations and commitments of life start piling up.

TG: I imagine that COVID-19, though, was an unprecedented type of struggle for everybody.

BD: The rug was pulled out from under us overnight, so our livelihood suffered greatly because of that. Fortunately, for me, I teach at two major institutions for music [Juilliard and NYU], so during the school year, that kept the wolves a little farther from my door in that regard. Teaching helps subsidize my performing career and vice versa. I was able to keep my head above water, but a lot of things just vanished. I had tours, residencies, record dates and numerous gigs. When you have those things on your calendar, you plan accordingly and all of it went up in smoke. But here I am. Things are slowly coming back, but it remains to be seen what’s going to happen with different variations on the theme, so to speak, of the virus. I got on a plane for the first time in July, went to Europe, did a festival, a bunch of gigs and a recording. It felt like the way I used to feel as a working musician from day to day. The travel part of it is not for the faint of heart. It was never really that luxurious, to say the least, but as musicians, that’s what we have to do. We can’t just play in our own back yards and expect to survive. For most of us who rely on performance, you have to get on an airplane for it to be at least somewhat lucrative.

TG: Would you say this speaks to the adaptability of those who make music?

BD: You have to go into every situation with an open mind and coalesce with everyone involved. The end result is making the music come to life. You’re presenting the music. It’s not about me as a drummer, showcasing my drumming. I can’t do that anyway! But there are those who can wow you and still be incredible contributors, like Tony Williams. Some are more overt than others. I’ve flocked around drummers for other reasons, like Billy Higgins, Al Foster and many others I could name who amaze but not overtly so. It’s all about musical conception, how the mind works in the moment. It gets beyond the rat-a-tat-tat physicality of all that. Why are they doing it and how did they come up with it? What are they listening to and for and how are they contributing to the big picture? They all have these audacious concepts and they bring them to fruition. And all that just by hitting stuff with two wooden sticks! It’s a question of how one does it completely differently while achieving musical greatness with a distinctive sound and style.

TG: Going back to the topic of practice, how do you keep yourself sharp? Do you have a set schedule or just work it in when you can?

BD: As you mature and are confronted with more of life’s responsibilities, it becomes more difficult to adhere to a schedule. That’s because you’ve got other stuff to do all the time. If you’re planning on practicing, things can interfere. When I do, I practice the same things I’ve always practiced, such as the things we drummers know as “rudiments.” Basically, these are combinations of doubles and singles in certain patterns. I also practice “time” because that’s what you’re doing 99.9% percent when playing with people. I play along with recordings, work on things I’d like to be able to do and all that. You have to stay up on these basic things to be able to bring whatever creativity that’s in your mind to fruition. You need to have a reasonable amount of facility to put your opinions out there. If you don’t, those ideas never come out. That’s what’s so remarkable about the thinking process of great drummers. We only hear the end result, but you can bet they worked on the nuts and bolts to move us with the music.

TG: Who embodies that philosophy for you?

BD: Pretty much anyone who played with Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, Jimmy Smith, Nancy Wilson, Art Blakey, Jackie McLean and all the others I grew up listening to. Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Jimmy Cobb, Philly Joe Jones…the list goes on. It’s all good stuff that I still find today to be the top of the heap in that genre of music. But you’ve also got to realize that, back then, you never saw these guys on television for obvious reasons. The star drummer in the public eye in those days was Buddy Rich, so I was enamored with him because he was billed as the world’s greatest and was more of an entertainer and a personality than some of the others I mentioned might have been perceived to be. So there he was, playing the drums and doing it really, really well. This being the early ’60s, I was attracted to what was on television. It was a natural thing. You had Batman, the Green Hornet and Buddy Rich.

TG: Who were your more immediate mentors?

BD: I would have to point to my parents and my father in particular because, being a former drummer himself, he’s the one who turned me on to jazz and the drums. As I look back on it now, he also had an incredible record collection. I was hearing all that music I mentioned as a youngster. I didn’t even know what it was, but at that age, you absorb whatever’s going on around the house. When I gravitated toward the drums, the two connected like that. Both of my parents were very supportive and encouraging of my endeavors. I was very fortunate in that regard.

TG: How have you changed the most since then?

BD: For one thing, I hope that I’ve improved as a musician who plays the drums and, with that, I hope that coincides with my improvements as a human being. Sometimes, I wish that I could go back and do things a little differently both on the personal and musical sides. For example, I think about being able to play with certain people I played with 30 years ago, only with the mindset I have now. When you’re in your 20s, you have a whole different thing going on when you arrive in New York. There’s nothing wrong with that; that’s the way life is. As we grow older, we hopefully have a better understanding of things pertaining to life. I’m trying to understand by looking at things from a different perspective. You tend to do that when there’s a lot less ahead of you than there is behind you. Now it’s like, “I’ve got to get this next stuff as close to right as possible because I’ve got no time to waste.”

TG: How does being a better person make you a better musician and vice versa?

BD: You’re a human being first and foremost. You’re faced and blessed with all the things that humans have to deal with. When you’re a musician, especially one who has devoted your whole life to music, it becomes so intertwined with your vocation as such. As someone who has surrendered his whole life to music, music and everyday life are intertwined. You wake up in the morning and a large part of your thought process is about music: playing, rehearsing, writing, listening, all of those things. I don’t think people who do certain other things for their livelihood necessarily think that way. But we creative people think about it 24/7 and that could be a problem because there are other things we have to think about, too. Society isn’t set up for creative people because we don’t fit into that same foundation.

TG: How does this relate to your life as a composer?

BD: I’m working at it. One thing I could look back on and regret is that I didn’t take the piano seriously when I had the opportunity to so now here I am at this age, struggling, just to put two notes together that sound listenable! I’ve had access to a piano for a large part of my adult life and childhood as well, but I don’t consider myself a composer. I’ve written some tunes. Horace Silver, Carla Bley, Andrew Hill and many, many others I’ve had the pleasure of working with: thoseare composers.

TG: Have you changed at all as a listener?

BD: I’ve always been a listener of recordings. No one plays in a vacuum. Listening is one of the things I consider that I do well. I can’t play anything if I don’t listen to what’s going on around me. I like to instigate and react to an action. The drummer is the de facto leader in some ways, controlling the tempo and volume, all of which can impede on or contribute to the proceedings. It’s also the loudest instrument on the bandstand, at least in an acoustic setting. But beyond that, the drummers that I admire and am influenced by are great musicians and listeners and that’s why they’re great drummers. I could name hundreds.

TG: What is the best compliment you ever got?

BD: Compliments said to me by people whose opinion I have a great deal of respect for. Beyond that, I’d say the greatest compliment is having people hire me to play with them. They could’ve had anybody, many of whom are pictured up on my own wall of drummers I admire. To be hired from that pool and the many other fantastic drummers out there? There’s no greater compliment. That’s enough to be grateful for and I certainly am.

(Billy Drummond can be seen and heard on his website here. This interview originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of The New York City Jazz Record, a full PDF of which is available here.)

https://www.billydrummonddrums.com/wp-content/uploads/Valse-Sinistre_Billy-Drummond_-Jazziz-interview.pdf

Billy Drummond: The Writers’ Drummer

by TED PANKEN

JazzIz

One of the signal releases this summer is Billy Drummond’s Valse Sinistre (Cellar Live). It’s the drum set master’s first leader date since 1996, when Criss Cross issued his third leader date, Dubai, a no-holds-barred yet highly disciplined recital on which Drummond guided the flow for saxophonists Chris Potter and Walt Weiskopf and bassist Peter Washington on repertoire by Dewey Redman, Pat Metheny, Billy Strayhorn, Irving Berlin and the participants themselves. Released in the pre-streaming heyday of CDs, Dubai made a contemporaneous splash (New York Times critic Peter Watrous selected it Best Jazz Album of 1996) and it continues to have legs — in 2017, Modern Drummer cited it in an article of “50 Crucial Jazz Drumming Recordings” over a 100-year span.

Like Dubai, Valse Sinistre — which includes compositions by Carla Bley, Stanley Cowell and Frank Kimbrough, all Drummond employers during the past two decades, as well as Jackie McLean, Grachan Moncur and Tony Williams — reflects the leader’s capacious taste and encyclopedic frame of reference. Here, though, Drummond, a 1959 baby whose selected web discography includes 160 sideman appearances since Dubai’s release, helms a virtuoso band comprised of two Gen-Xers (saxophonist Dayna Stephens and bassist Dezron Douglas) and Gen Z pianist Micah Thomas.

During the first week of July, I visited Drummond at his Essex County, New Jersey, home, which boasts six audiophile sound systems, a well-organized multitude of CDs and vinyl, and memorabilia and ephemera that includes numerous photos of heroes and colleagues and a K Zildjian cymbal signed by Tony Williams. After an hour of chit-chat and an entertaining turn-the-tables blindfold test framed around a compilation CDR with various tracks of another drum idol, Billy Higgins, we got down to the business at hand.

You call this band Freedom of Ideas, reflecting, as you write in the liner notes, the attitude and operative aesthetic of the Miles Davis Quintet with Tony Williams. What’s the gestation for the project?

I’ve been putting together bands for about 20 years. Many people have come in and out, as I don’t have enough bandleader work to keep a constant personnel. It’s mostly one-offs at places like Smalls or Smoke. So I try to get who I can get — that I like. I always try to get Dezron, who I call “the voice of reason” because he

always has interesting ideas or suggestions. We met in 2011 when Eric Reed assembled a band that played the music from Clifford Jordan’s Glass Bead Games.

These guys are all open, all bandleaders, doing their own records and playing with people in their peer group. I might not even be their first choice of someone to call. I’m from another time — the people I was hanging with back then were my age. They can go any direction, which I want to do. They all write. They all have great ideas. They prop me up, because I don’t know what they’ll do when they play. I like to ring a lot of different bells. I’m open to most anything, if I want to do it and feel I’m up to the task. I know my limitations. I know what I’m capable of. Some things I may not think I’m capable of, but I want to try anyway.

Two pieces — “Little Melonae” and Grachan Moncur’s “Frankenstein” — reference Jackie McLean.

Dezron brought in “Little Melonae” at the last minute. He went to Hartt [School, at the University of Hartford] — he’s one of Jackie’s people. I love Jackie McLean. If I want to give people an example of what I think jazz is, I’d play them something by Jackie — Capuchin Swing or New Soil or Jackie’s Bag. My dad had those records; I grew up with them.

Micah Thomas’ “Never Ends” is vibrationally in the room with Andrew Hill, who you played with for a while.

Micah brought in three or four pieces. We could have done any of them — I chose this one. The melody is straight up and down, not swung, though the rhythm section is loosely swinging behind it. The last 4-bar time signature vamp repeat is more of a blues sound. Micah takes all those elements and throws them into the way he interprets the changes in his solo. Dayna, too — he’s hinting at the melody. I have to ask Micah if he was thinking about Andrew. Micah was my student at Juilliard, though I wasn’t teaching him anything — we played and listened to music and talked. He’s very accomplished, has his own thing, and I’m sure it will develop into something different. He studied with Frank Kimbrough for most of his time at Juilliard, and Frank — who loved Andrew — turned me on to him. Frank loved a lot of the people I’d worked with — Carla and Steve Swallow, Andrew, Stanley Cowell.

Do you see connecting threads between those musicians?

Very individualistic. Like the greatest of all the people in the improvised music world, they’re immediately recognizable by their sound, their musical stamp. They’re unique. Maybe they could tell that I was interested and willing to participate with what they do. You don’t necessarily aspire to play with people like that. As you’re growing up, whatever you’re doing, somehow you encounter their music and then you’re hooked.

Before I got to New York in 1988, I didn’t belong to any one camp. There was nobody to tell me, “Don’t listen to Lee Morgan because that’s old” or “Don’t listen to the Art Ensemble of Chicago because that’s not happening” or “Don’t listen to … .” Basically, I was just soaking it all up, and I was left to my own devices to make my own decisions about what I liked. Jan Garbarek? Yeah, he’s not Hank Mobley, but I like it. And I love Hank Mobley, too! I just wanted to play, and I wasn’t trying to make any firm decisions about what group I’d be identified with. I’ve never been part of any particular clique. I’ve dipped and dabbed in all of them. My attitude was: If I can do it, if I’m up to the task, even if I’m not up to the task, let me try to play with Horace Silver; let me try to play with Marty Ehrlich. Why not? I like it all.

The title track, “Valse Sinistre,” is by Carla Bley, who you played with frequently. How did she find you?

I have my suspicions that it was Steve Swallow, because Swallow and Steve Kuhn are like brothers, and I’d been with Kuhn for years. I’d never played with Swallow, though. I didn’t even know him. But I got called in 2000 to sub for Victor Lewis in

Carla’s band, 4X4, for a concert at the Knitting Factory — it was Lew Soloff, I think Vince Herring and Craig Handy, Gary Valente on trombone, Will Boulware on organ. Victor is one of my idols. He can do anything — David Sanborn, Oliver Lake, Dexter Gordon. I had a couple of Carla Bley records, but I wasn’t well versed in her music. They sent me the music, I learned it, we rehearsed — and did the concert. After that, she invited me to play with her big band.

Now, I’m not a big band drummer, but her band is completely different than Basie or Ellington or Thad Jones-Mel Lewis. There’s people who can go in and out of a big band drummer’s mentality, like Lewis Nash. I’ve never been a guy that could

catch this hit here, set this up — though I do that to a certain degree, playing on records by all these people who write. I always want to play what I want to play. Most big band drummers got typecast into that’s what they do, like Butch Miles or Sonny Payne.

Carla wrote “Valse Sinistre” for an opera by Leonora Carrington that never came to fruition. We played it on one of the tours in the small group. I fell in love with it, and I told Carla, “One day I’m going to record this.” So when the opportunity came, I called Carla, and she gave her blessing. It’s her chart, though we approached it with a different feel.

David Raskin’s ballad “Laura,” from the Otto Preminger movie, is an interesting selection for a drummer’s record.

I love the movie, Laura, and that theme goes throughout it in different ways. To me, it conjures up film noir. I felt that song is like the Mona Lisa or something. Don’t add anything. Don’t take anything away. It says what it says — that’s it. I didn’t want to play solos. I wanted just to play this song, as if I was singing it —

like Frank Sinatra or Ella Fitzgerald or Jeanne Lee with Ran Blake, which is a great version.

Have you played with many singers over the years?

Not that many. I guess the best-known singer I’ve played and recorded with most is Sheila Jordan. She’s born the same year as my mother, in 1928, so we have a bond. My mom died when I was 20, so I didn’t get to know her as an adult. I would have loved to invite her over, fix dinner, talk and have a glass of wine — have that kind of relationship. I did with my father, who died when I was 35.

Your father got you onto the drums, I gather.

Yes. When he died, I’d moved to New York, played with the people who were his heroes, like J.J. Johnson and Sonny Rollins. I could tell him, “Guess who just called me?” “Really?!” He was a semi-professional drummer who stopped playing shortly before I was born and became a law enforcement officer. But he had a great record collection. He didn’t have his drums anymore, but my grandmother gave me a drum and then he showed me how to hold the sticks.

He was born in 1925, the same age as Roy Haynes and Max and Philly Joe and Elvin. He loved those guys, but he worshiped Chick Webb and Big Sid [Catlett]. He carried himself like a jazz guy. He had a vibe. Sonny, J.J. and Max all carried themselves a certain way. I made that connection when I saw Max Roach for the first time in 1979. “Ladies and gentlemen, Max Roach,” curtain opens and he

walks out to the drums — not arrogant, but confident. He carried himself like “I am.” It reminded me of my father and uncles and the African American men in my neighborhood that had done OK. They had a house and a family. They had made it, so to speak … not that anybody was rich. The neighborhood was called Warwick Lawns [in Newport News, Virginia], and it was the first residential neighborhood built for colored families.

You grew up around several people who became prominent musicians — the Wooten Brothers, Steve Wilson.

We all lived in that neighborhood as kids. It wasn’t necessarily jazz when we would, quote unquote, “jam” in each other’s garage or our house or whatever. We were playing music we liked from the early ’70s, Kool and the Gang, Larry Graham and stuff like that, but also new music that wasn’t necessarily commercial, but had the same instrumentation — electric bass, electric guitar, keyboards, drummers with a lot of chops. Fusion music. We were drawn to that because it was the next level of virtuosity for the instruments that guys were playing in soul bands and R&B bands. Mahavishnu and Return to Forever were new. These were jazz guys who’d moved on to this other thing, probably based on the fact that most of

them were Miles Davis alumni — McLaughlin, Chick, Lenny White, Billy Cobham, Wayne Shorter, Zawinul, Tony Williams Lifetime. We were drawn to that. If a guitar player could play, and let’s say he was into Ernie Isley and Hendrix, and then he hears McLaughlin or Al DiMeola or Allan Holdsworth — WHOO! Then that leads them … . That’s how that worked. I’d grown up in a household where my father was playing hard bop, so I was drawn to that. All that stuff was going on at the same time. Nobody thought one was hipper than the other. A lot of those people were totally into the other thing. But that was cool, too, because they were really good at that.

When did you start to play in bands?

I was playing in bands from the time I was 8 or 9. Soul pop bands with the people in my neighborhood. At the same time, I’d started taking formal snare drum lessons with a drum teacher, a guy I just spoke to last week, named Wynn Winfrey, who had me studying out of the classical snare drum books. Then I started teaching for him because he had so many students. I was 14, teaching beginners.

How did Andrew Hill find you?

Andrew came to the Vanguard a few times when I was working with Bobby Hutcherson, which is how he knew about me, I think. A few years later, I went to Sweet Basil, where my good friend Tony Reedus was playing drums with Andrew. Joe Henderson and Charles Tolliver, who I’d played with, were at the bar, so I immediately struck up a conversation with them. On the break, Andrew came up and they introduced us. He said, “I heard that you like my music.” I don’t know how he knew. Sometime long after that, he called me out of the blue and asked me to participate in this gig at the Knitting Factory, which included Marty Ehrlich and Scott Colley, who I’d played with in other situations. I had a lot of Andrew’s Blue Note records — Black Fire, Point of Departure, Judgment! and Andrew!!!, the stuff he did with Bobby Hutcherson — so I followed what Joe Chambers and Tony Williams and Roy Haynes and Billy Higgins and Elvin Jones did on those records. That set me up to come in and be able to at least acquiesce to the situation.

I saw an interview where you said you weren’t a big transcriber, but you copped.

That’s it. I didn’t write it down. At Juilliard, one prerequisite to passing is doing a jury at the end of the year, and on the list is transcribing solos that your teacher gives you. “Joe Green, I want you to transcribe the solo that Billy Higgins takes on ‘Our Man Higgins.’ Write it out. Be able to play it.” I did it more aurally. It might not even have been the whole solo, but just the things that spoke to me. “Wow. I like what he did there. What is that?” Then I’d pick up the needle and play it over and over until I figured out what it was. Certain people were easier for me, because I didn’t have the facility. Philly Joe Jones was too difficult; Buddy Rich, too difficult. Max Roach I could relate to because it was melodic. Al Foster I can relate to because it’s melodic. Elvin was more about the vibe, the feel. Nobody can play like that, not really, but we all have to do our little facsimile imitation, because you have to be able to emote that aesthetic when someone hands you music and says, “I’m hearing like an Elvin-ish kind of thing.” You know what that means right away. It doesn’t mean Buddy Rich. It doesn’t mean Ed Blackwell. It’s very specific. But in that specificity, it’s broad.

Why the big gap between the new record and Dubai?

People love that record. I was influenced by some of those drummer bands that didn’t have a piano — Jack DeJohnette; Tony Williams on the first Lifetime; Elvin, who had those bands with Dave Liebman and Steve Grossman and George Coleman and Joe Farrell; Max Roach with Billy Harper and Cecil Bridgewater; Paul Motian with Charles Brackeen and David Isaacson; Old and New Dreams with Dewey Redman and Don Cherry.

I tried to get a record date. I knocked on some doors, and doors slammed in my face. Nobody was interested. I gave up. I was like, “OK, I’ll just do my bands and have some fun playing and play with people I want to play with.” Then [trumpet player] Jeremy Pelt contacted me and asked if I wanted to record my band for Cory Weeds’ label. We’re good friends; I’d worked with him a lot and did two records with him. I’d also done a record for Cory with Sam Dillon, a tenor player who was my student.

You’ve described pianist Stanley Cowell’s “Re-confirmed” as a deconstruction-reconstruction-reimagined interpretation of “Confirmation.” You recorded it on his Steeplechase album Reminiscent, the second of your three albums with him.

Stanley would look at a song and reimagine it from the inside out. That cat was brilliant. I had worked with Stanley when Charles Tolliver reunited the Music

Incorporated band that he’d had with Jimmy Hopps and Cecil McBee in the 1970s — with me playing drums. That was a thrill, because I grew up with that music in the ’70s, when a lot of records were coming out on Strata-East, ECM, CTI, Muse,

Xanadu. You didn’t know what it would be, but you bought them because it was the cats! After that, I played with Stanley again in Charles’ big band. My first record date with Stanley was in 2014, with Jay Anderson on bass, a great musician with tons of experience. We’d done a bunch of records for Steeplechase as bass player and drummer, and I guess Nils [Winther] figured we would be a good fit with Stanley.

You said that Jackie McLean defines for you what jazz is. What’s your sense of what jazz means to your students?

I believe that you have to live in your own time. If you’re 18, 19, 20 years old, your world is completely different than my world was at that age. When hip-hop emerged, I was already a grown man. I never really was attracted to it, or rap. That’s not to say it’s good or bad. But that was the soundtrack for a lot of the younger drummers as school-age people. My soundtrack was the music I heard in my parents’ house. My sister was playing Gil Scott-Heron. My dad was playing Jackie McLean. My mom was listening to Nancy Wilson. Me and my friends were listening to Graham Central Station, plus Mahavishnu and stuff like that. Elvin Jones doesn’t have any rock and roll influence in his being. Maybe some kind of like old R&B that’s more based on a shuffle. Philly Joe Jones doesn’t have any rock and roll. He played R&B and all of that. But, see, Tony Williams is influenced by The Beatles, because of his age group — he was a teenager when The Beatles emerged.

So I turn my students on to what I know about, and I don’t force it on them. Some of them don’t get it until later. I didn’t really get Connie Kay until I was in my 40s. One of my friends did not get Billy Higgins, and some of my students were like that, too. For them, he’s not doing anything overt — and they didn’t see him play. See, we got the chance to see Billy play. It would change your life. It felt good no matter what. It wasn’t, “Look at me.” A lot of drummers now are “look at me” drummers. They’ll play something to get you to respond, or, “look at how complicated … .”

Well, you were never a look-at-me drummer.

I was never a look-at-me drummer. I wanted to be a New York jazz drummer. That meant playing in New York with jazz people. I wanted to be Billy Hart and Al Foster and Billy Higgins. I associated Higgins with New York, even though we all know he came to New York with Ornette Coleman from Los Angeles. But I just think of all those Blue Note records. That’s New York. That’s Higgins, Joe Chambers, Jack DeJohnette, Billy Hart, Al Foster. These are New York jazz drummers to the bone. And they played with everybody. The first Lifetime record, Emergency, has a Carla Bley tune. I asked Carla how that came about. She said, “Well, Tony and I knew each other and he’d come to me and go, ‘You got any tunes?’” He played on Mike Mantler, her second husband’s record, Movies.

I didn’t come here with any expectation. I came with money saved up from doing a gig with a Top 40 band called The Squares. We were playing five nights a week for dancers. We learned two songs a week. I was singing and playing the drums, playing songs off the radio — Duran Duran, Huey Lewis and the News, Prince, The Pretenders, Billy Ocean. When I had enough money to pay rent for one year, I decided to come, and I could go back if I didn’t make it, which is what I thought would probably happen. I thought: I’ll have a great time; I might meet some people; I’ll get to see a whole bunch of people play that I always dreamed of playing with. But it worked out the other way.

They say everything happens for a reason. Sometimes I tend to believe that. I prepared myself slightly financially, and I guess I was prepared musically, because I jumped into some musical situations. People threw me a bone, gave me a chance, and I didn’t sink. I swam a little bit. Boom, that’s what happens.

Review

Music Reviews

New quartet album by jazz drummer Billy Drummond is a treat

On Valse Sinistre, Drummond's ride-cymbal beat is lively, varied and full of passing cross-rhythms — the sound of a musician fully engaged and in the habit of attentive listening.

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. Over the last 30 years, jazz drummer Billy Drummond has made hundreds of records with, among many, many others, horn players John Faddis, Javon Jackson and Marty Erlich, and pianist Renee Rosnes, Steve Kuhn and Carla Bley. He also records as a leader. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says Drummond's new quartet album is a treat.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "LITTLE MELONAE")

KEVIN WHITEHEAD, BYLINE: Billy Drummond's Quartet on Jackie McLean's "Little Melonae," the sound of a drummer keeping time on ride cymbal is a familiar jazz marker, maybe even a jazz cliche. True, some drummers keeping time sound like they're on autopilot, self-hypnotized, but not the best ones like Billy Drummond. His ride cymbal beat is lively, varied and full of passing cross-rhythms, the sound of a musician fully engaged, hearing and reacting to everything happening around him.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "LITTLE MELONAE")

WHITEHEAD: Saxophonist Dayna Stephens with Billy Drummond's quartet Freedom of Ideas from their new album "Valse Sinistre." The leader doesn't take many solos, but he doesn't need stand-alone spots to show his stuff. He conducts a lot of side business while keeping time. Great jazz drummers are motivators, prodding their comrades and making sure everything swings in an interactive way. This is Micah Thomas on piano.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "RECONFIRMED")

WHITEHEAD: The title track of "Valse Sinistre" is a gem of a waltz by Drummond's old boss, Carla Bley. Dayna Stephens plays it on soprano sax whose bright tone suits the melody and leaves exposed the rhythm section's sideways moves underneath. On bass is Dezron Douglas.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "VALSE SINISTRE")

WHITEHEAD: "Valse Sinistre" by Carla Bley. The slow ballad and one standard on the album "Valse Sinistre" is David Raksin's 1944 movie theme, "Laura." Billy Drummond's quiet grace with wire brushes reminds me of the great tap dancer Bill Robinson doing a rhythmic shuffle on a sandy surface. But Drummond can also be a little contrary.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "LAURA")

WHITEHEAD: On Billy Drummond's album "Valse Sinistre," there is also music by pianist Stanley Cowell and Frank Kimbrough and drummer Tony Williams and by members of the band. The quartet revived the late trombonist Grachan Moncur's "Frankenstein" from 1963, a minor tune with odd chord changes, the kind of offbeat choice that helps make this album a treat. It's not surprising that a leader in the habit of attentive listening would turn up some good, old tunes that other folks overlook.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "FRANKENSTEIN")

WHITEHEAD: Kevin Whitehead is the author of the book "Play The Way You Feel: The Essential Guide To Jazz Stories On Film." And he writes for Point of Departure and The Audio Beat. He reviewed the new album Valse Sinistre by Billy Drummond's quartet, Freedom of Ideas.

On tomorrow's show, the risk of growing tension between China and the U.S. Michael Beckley says China is engaged in the largest military buildup since World War II and is being increasingly aggressive with its Asian neighbors and with the United States. Beckley's new book with Hal Brand (ph) is "Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict With China." I hope you can join us. For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

(SOUNDBITE OF BILLY DRUMMOND AND FREEDOM OF IDEAS' "FRANKENSTEIN")

Copyright © 2022 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

https://www.jazzwise.com/review/billy-drummond-and-freedom-of-ideas-valse-sinestre

Billy Drummond & Freedom of Ideas: Valse Sinestre

Editor's Choice

Author: Mike Hobart

View record and artist detailsBilly Drummond last released an album under his own name on the Criss Cross label in 1996 – Dubai featured Walt Weiskopf and a young Chris Potter on tenor sax. Since then, the American’s long list of credits ranges from Archie Shepp and Andrew Hill to Joe Lovano and Hank Jones. And the album’s title track marks the five years Drummond spent working with Carla Bley – that gig started in 2003, but ‘Valse Sinistre’ comes from Bley’s 1981 album Social Studies, which featured tuba and euphonium among its five-piece brass.

Impressively, Drummond captures the contours of Bley’s village-band aesthetic through the sonics of a feisty, contemporary mainstream, sax-and-rhythm quartet. Drummond’s style is rooted in Tony Williams’ work – the album closer ‘Lawra’ was composed by the late drummer – and here explosive cymbals flesh out texture and drive the band. Bassist Dezron Douglas is on form in the holding role, pianist Micah Thomas moves smoothly from swing to the avant garde and saxophonist Dayna Stephens digs deep into each cut.

Covers of Jackie McLean’s ‘Little Melonae’ and Grachan Moncur’s ‘Frankenstein’ confirm roots in Blue Note’s 1960s left-field; ‘Never Ends’, written by Thomas, is bucolic and features soprano sax; and the gorgeous arrangement of the ballad ‘Laura’ was pre-composed. Elsewhere, the leader’s ‘Changes for Trane and Monk’ delivers angularity and drive at speed and ‘Reconfirmed’ is a piano trio workout. The beautifully crafted ‘Clara's Room’, the album’s penultimate track, pays homage to its composer, pianist Frank Kimbrough, a close colleague and friend of Drummond's, who recently died. Top album.

Billy Drummond interview

21 June 2022

Marlbank

Speaking on the phone from his home in West Orange, New Jersey at noon on the longest day of the year Billy Drummond who releases his first album under his own name in many years this summer speaks of doing errands earlier in the day and ''going to a friend of mind who's an audiophile with a half million dollar system'' later. ''I've practised,'' he mused.

Outside in the neighbourhood he sees his neighbours' houses through his window. There are also ''squirrels, chipmunks, a family of rabbits'' in the leafy area. The drummer, composer, bandleader and Julliard professor, has lived there for 30 years, his home ''twenty five minutes'' from New York City by car or train.

Now in his early sixties and long since a legend among jazz fans mainly for being on other people's records as a sideperson. But what people. Carla Bley, Horace Silver, Nat Adderley, Vincent Herring, Archie Shepp, Steve Kuhn the list goes on and runs decades long - not to mention touring with Sonny Rollins - and a few choice releases of his own over the years, notably Dubai the last one he put out with its attractively brooding Eastern-tinged minor key feel, a wind-of-change atmosphere to the title track.

Playing in Montreal and in Paris he says when asked about recent gigs the upcoming record is with Drummond's Freedom of Ideas band and first under his own name in some 26 years and is on a Canadian label, Cellar Live, run by saxist and former Vancouver jazz club owner Cory Weeds.

The title track is a treatment of a Carla Bley piece 'Valse Sinistre' a tune that Billy played on the road with Carla. He told the iconic composer and bandleader ''20 years ago'' that he'd do a treatment of her composition. Promise duly kept. Billy says he wrote to Carla recently to tell her the piece would be the title track - to her palpable delight.

Album producer hard bop trumpet icon Jeremy Pelt put Billy in touch with Cellar Live to be part of a theme of African-American leaders going forward to address a lack of representation hitherto on the label.

Billy says Jeremy was good ''to have in the booth as a second pair of ears and choose the best take, whether Take 1 or Take 2. Our opinions might differ but he has good reasons for his opinions.'' The pair have played together on Pelt's records in the past including 2016 gem #Jive Culture.

Recording Valse Sinistre in Englewood Cliffs at one of the world's most famous and history making recording studios - where John Coltrane recorded A Love Supreme - Rudy Van Gelder's, we talk about Rudy a bit who passed away in 2016 and who Billy knew well having made records at the studio ''in the 1980s and 90s and the first 10 years of the 2000s but not for two or three years’’. He says Rudy could be ''prickly'' and that you didn't want to show him any attitude. ''He liked things in particular ways, like where you ate and he had his own protocol''. Billy says he wasn't there to ''ruffle any feathers'' and so following Rudy's preference didn't come into the mixing spot where the engineers were doing their thing. ''Don't play this piano or that'' he would admonish musicians. ''I don't want to have to re-tune it,'' he'd say.

On Valse Sinistre which has among its delights a version of Tony Williams classic 'Lawra' also known as 'There Comes a Time' to be newly reissued in its Play Or Die version is a former Julliard student of Billy's named Micah Thomas who at Julliard was also taught by the late Frank Kimbrough. Billy recorded with Frank, double bassist Rufus Reid and reedist Scott Robinson on an acclaimed complete Monk project that Sunnyside put out in 2018.

Billy explains that he had been playing in the now shuttered Jazz Standard and a guy in the audience, “an older guy who had seen Monk at the Five Spot,” and who turned out to be from the Sunnyside label, liked what he heard and Kimbrough’s mammoth Monk project got the green light for a recording.

Kimbrough died around the time pianist and Strata-East legend Stanley Cowell passed and Billy knew and also had played with Cowell for instance on SteepleChase album No Illusions (2017), again a loss that he feels deeply.

We talk about Jackie McLean a little bit and Billy says that growing up listening to his father's records he loved Capuchin Swing (1960) and includes a version of McLean’s Jazz Messengers-beloved 'Little Melonae' from Hard Bop (1957) on Valse Sinistre.

The late Grachan Moncur III's 'Frankenstein' also on Billy and the Freedom of Ideas' album alto sax icon McLean covered on the 1964 released One Step Beyond is another link.

It is worth pausing to reflect on more of the records Drummond has been on since the 1990s. A lot of his heroes he actually got to play with makes this even more striking. For instance he is on Andrew Hill record Dusk, a late period classic in the great composer's catalogue.

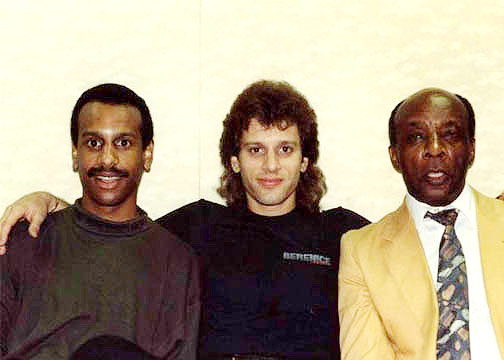

Dezron Douglas, above left, Billy Drummond, Micah Thomas, Dayna Stephens

With Micah in the Freedom of Ideas (who Frank Kimbrough his colleague at Julliard told Billy would be great with him having taught him himself) is also the acclaimed bassist Dezron Douglas known in recent times for a fine version of 'The Creator Has A Masterplan' with harpist Brandee Younger and completing the band the tender saxophone genius Dayna Stephens who is superb on the record and completes the quartet.

Billy himself is a natural born-to-play rhythm master. Spang-a-lang, driving rhythms, beautiful cymbal work especially on the David Raksin classic ‘Laura’ leads me to ask him because he played back in the day with iconic trombonist J. J. Johnson if he knows J. J.'s version from the much earlier J. J. In Person. Turns out that he doesn't. But he says he likes the Ran Blake, Frank Sinatra and Bill Evans treatments. He also liked the 1944 movie noting that it’s ''a film noir'' and says when asked that his wife fine singer Tessa Souter hasn't covered the song describing it as a 'Mona Lisa' of a creation in a great turn of phrase.