SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER THREE

MARC CARY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

REVOLUTIONARY ENSEMBLE

(June 11-17)

OLU DARA

(June 18-24)

WALTER SMITH III

(June 25-July 1)

BOBBY WATSON

(July 2-8)

JAMES MOODY

(July 9-15)

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

(July 16-22)

LEYLA McCALLA

(July 23-29)

GREG LEWIS

(July 30-August 5)

RUSSELL MALONE

(August 6-12)

JOHN HANDY

(August 13-19)

STANLEY CLARKE

(August 20-26)

JASON HAINSWORTH

(August 27-September 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bobby-watson-mn0000765494/biography

Bobby Watson

(b. August 23, 1953)

Biography by Richard Skelly

Saxophonist, composer, producer, and educator Bobby Watson is an adroit jazz performer with an aggressive, fluid style influenced by his early years with drummer Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. A native of Kansas City, Kansas, Watson's playing is steeped in the roadhouse blues tradition of his native city. He got his formal education at the University of Miami, where his fellow students included Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius, and Bruce Hornsby. After graduating in 1975, he moved to New York City, where he made his solo debut with 1977's E.T.A., followed two years later by All Because of You.

It was also at this time that he found employment as musical director for Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. Watson stuck with Blakey's group from 1977 to 1981, appearing on a bevy of the drummer's albums during this period. However, he continued to record as a leader throughout the '80s, delivering such albums as 1984's Advance and 1986's Love Remains.

In the late '80s, inspired by Blakey and pianist Horace Silver's hard-bop outfits of the '60s, Watson launched his own group, Bobby Watson & Horizon with bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Victor Lewis. The group enjoyed a modicum of mainstream attention, signing with Blue Note and debuting with 1988's No Question About It, which also featured trumpeter Roy Hargrove. More well-received albums followed, including 1989's The Inventor, 1991's Post-Motown Bop, and 1992's Present Tense with trumpeter Terell Stafford. Aside from his solo work, Watson pursued session and tour work with vigor, working with drummers Louis Hayes and Max Roach, saxophonists George Coleman and Branford Marsalis, multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers, guitarist Carlos Santana, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, and others. He also worked with a who's who in the jazz vocal world, including Joe Williams, Dianne Reeves, Lou Rawls, Betty Carter, and Carmen Lundy.

A passionate educator, he also served as a member of the adjunct faculty at William Paterson University in the mid-'80s and at the Manhattan School of Music from 1996-1999. During this period he also stayed busy, releasing the big-band effort Tailor Made and exploring funk and R&B on 1995's Urban Renewal. In 2000, he was selected as the first William D. and Mary Grant/Missouri Distinguished Professor of Jazz Studies, and spent over a decade working at the University of Missouri/Kansas City, balancing live concerts around the world with his teaching responsibilities.

However, performing remains his focus, as evidenced by such albums as 2002's Live & Learn, 2004's Horizon Reassembled, and 2008's From the Heart. A year later, he joined percussionist Ray Mantilla for the Latin-infused Everlasting. He then marked the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream Speech" with 2013's Check Cashing Day. In 2017 he delivered Made in America, recorded live at the Smoke jazz and supper club in New York City.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/bobby-watson

Bobby Watson

A saxophonist, composer, arranger and educator, Bobby Watson grew up in Kansas City, Kan. He trained formally at the University of Miami, a school with a distinguished and well-respected jazz program. After graduating, he proceeded to earn his “doctorate” – on the bandstand – as musical director of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. The group, created in 1955 by late legendary drummer who died in 1990, showcased a rotating cast of players, many who, like Watson, would go on to have substantial careers as bandleaders in their own right. The Jazz Messengers – frequently referred to as the “University of Blakey” – served as the ultimate “postgraduate school” for ambitious young players.

After completing a four-year-plus Jazz Messengers tenure (1977-1981) that incorporated more than a dozen recordings – the most of any of the great Jazz Messengers, the gifted Watson became a much-sought after musician, working along the way with a potpourri of notable artists – peers, elder statesmen and colleagues all — including, but not limited to: drummers Max Roach and Louis Hayes, fellow saxophonists George Coleman and a younger Branford Marsalis, celebrated multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers and trumpeter Wynton Marsalis (who joined the Jazz Messengers at least in part at the suggestion of Watson). In addition to working with a variety of instrumentalists, Watson served in a supporting role for a number of distinguished and stylistically varied vocalists including: Joe Williams, Dianne Reeves, Lou Rawls, Betty Carter and Carmen Lundy.

Later, in association with bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Victor Lewis, Watson launched the first edition of Horizon, an acoustic quintet modeled in many ways after the Jazz Messengers but one with its own distinct slightly more modern twist. Among the groups' other talented members were pianist Ed Simon, trumpeter TereIl Stafford and bassist Essiet Okon Essiet. Clearly, by all critical accounts, Horizon, which still performs together on special occasions, is now considered as one of the preeminent small groups of the mid-1980s to mid-1990s and even into the 2000s. The group recorded several highly acclaimed titles for the Blue Note and Columbia record labels including Post-Motown Bop (Blue Note) and Midwest Shuffle, Live! (Columbia); the latter is a compendium that captured the group in concert at a number of locations in 1993.

In addition to his work with Horizon, Watson also led a nine-piece group known as the High court of Swing – a tribute to the music of Johnny Hodges – as well as the GRAMMY-nominated 16-piece, large ensemble Tailor Made Big Band. The lyrical stylist is also a founding member of the well-respected 29th Street Saxophone Quartet, an all-horn, four-piece ensemble.

Watson's classic 1986 release, Love Remains (Red) has long been recognized by the Penguin Guide to Jazz (Penguin). Having received the publication's highest rating it was then identified in the ready reference book's seventh edition as a part of its “core collection” [i.e. a “must-have”], joining other entries by a number of aforementioned jazz masters as a recording that any jazz aficionado should own.

More recently Watson issued a series of recordings on the Palmetto label. On the heels of his No. 1 releases, Live & Learn (2005) and Horizon Reassembled (2006), which brought him back together with Lewis, Stafford, Simon and Essiet, the saxophonist issued From the Heart (2008) which unveiled yet another project where he again shares the limelight with bassist Lundy. The release also went to No. 1 on the national jazz airplay chart and remained there for nine weeks.

For more than three decades now Watson has contributed consistently intelligent, sensitive and well-thought out music to the modern-day jazz lexicon. All told, Watson, the immensely talented and now-seasoned veteran, has issued some 30 recordings as a leader and appeared on 100-plus other recordings, performing as either co-leader or in support of other like-minded musicians. Not simply a performer, the saxophonist has recorded more than 100 original compositions including the music for the soundtrack of A Bronx Tale, which marked Robert DeNiro's 1993 directorial debut. Numerous Watson compositions have become classics such as his “Time Will Tell,” “In Case You Missed It” and “Wheel within a Wheel,” each now oft-recorded titles that are interpreted by his fellow musicians both on the bandstand and on other recordings.

Bobby Watson, Educator In addition to his compositional and performance prowess Watson is equally respected as an educator. More importantly, he now inspires those a generation or more younger than himself – passing on his great knowledge. His teaching within known jazz programs and institutions began in the mid-1980s when he served as a member of the adjunct faculty and taught private saxophone at William Paterson University (1985-1986) and Manhattan School of Music (1996-1999). As the millennium hit Watson hit his stride in the educational field. The recipient of the first endowed chair at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music and Dance, the saxophonist, after using The Big Apple as his home base for 25 years, came full circle returning to his native locale in 2000. Appointed as the first William D. and Mary Grant/Missouri Distinguished Professorship in Jazz Studies, he continues to serve as the Conservatory's Director of Jazz Studies. A decade into that position Watson now attracts the city's home-grown talent as well as the region's – and some of the nation's — most gifted aspiring musicians to attend his program. He capped off his first 10 years in the position by first conceptualizing and then delivering one of his most ambitious projects to date – one where he combines all of his talents: composing, arranging, producing, teaching and performing.

In late fall 2010 Watson released his seven-part, all-originally composed The Gates BBQ Suite, which went to #4 on the National Jazz Airplay chart. The selfless Watson designed this complex work – which draws upon childhood remembrances and experiences centered on his family's involvement in the business and his home-town's semi-official food – to primarily showcase his students. Arranged as a big-band endeavor, with Watson only playing sporadically, The Gates BBQ Suite houses an abundance of ensemble playing and solos from those who study with Watson. Said Will Friedwald in the Wall Street Journal: “The Gates BBQ Suite, performed by Mr. Watson and the University of Missouri at Kansas City Concert Jazz Orchestra, is quite likely the most K.C.-specific work of his career thus far. It is, in every way, a worthy companion to the most famous long-form work celebrating jazz in that city, the 1960 ‘Kansas City Suite,' written by Benny Carter for Count Basie (neither of whom were K.C. natives, although Basie was easily the single greatest ambassador for K.C. jazz). In 1992, when Mr. Watson produced his first big band album, Tailor Made, Columbia Records trumpeted that the sessions were completely unrehearsed – as if that were somehow a positive thing; here it's abundantly clear that Mr. Watson and his students have ample rehearsal time to get everything right...” All this said, just releasing the recording was not enough for the energetic Watson. Using guile and his boundless creative energy Watson was able to create an opportunity for him and his students to travel to Japan for a 10-day tour that showcased Gates and other compositions. To say they were well-received would be a drastic understatement. Now, as 2011 hits, Watson has prepared each of Gates' seven charts to stand either together as a suite or individually and has made them available to band directors around the world so that he can serve as an artist-in-residence and/or special guest and have the work performed in whole or in part anywhere.

As in-demand as ever, the lyrical saxophonist balances his teaching responsibilities with engagements at major venues throughout the world including appearances at clubs, festivals, on campuses and at Performing Arts Centers.

Tags

Bobby Watson

Latest Release: Gates BBQ Suite

LIMITED EDITION (SOLD OUT)

On the horizon

-

October 13-15, 2021

Tru Blue Festival

Delaware

Over time, saxophonist Bobby Watson has learned to connect the idea of the blues in his life and in his music. (Photo: Jimmy & Dena Katz)

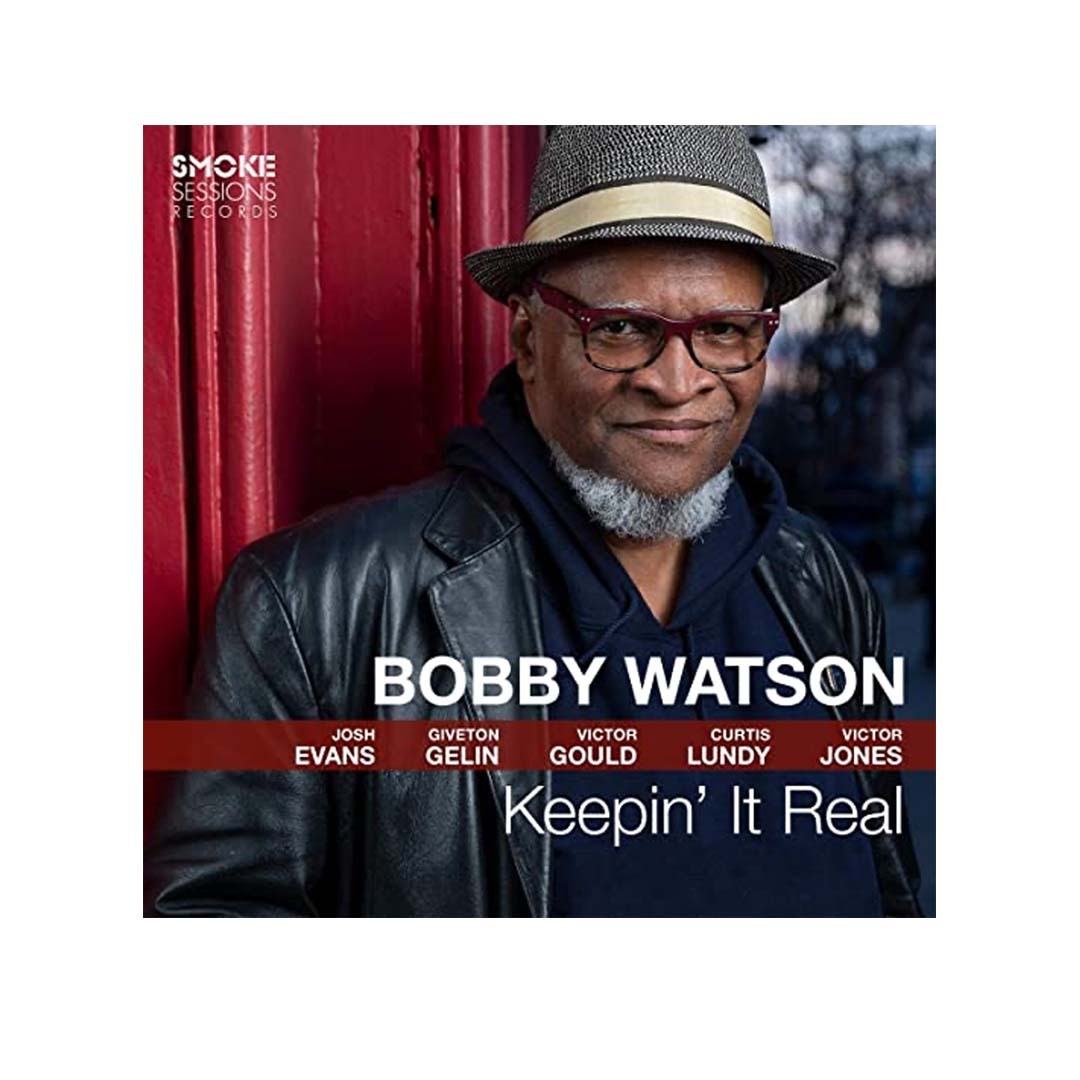

“You can’t believe how many musicians are afraid of the blues, man,” Bobby Watson said recently over the phone from his home in Lenexa, Kansas, a suburb southwest of Kansas City. It’s a natural topic, given the blues’ centrality to the sound and feel of jazz, and it’s particularly apt in light of Watson’s latest album, Keepin’ It Real (Smoke Sessions). Recorded with his new band, it maintains the bop-schooled brilliance that the alto saxophonist is known for, but flavors the music with a strong sense of the blues—and even gospel at one point.

It’s not a revolutionary move by any means. As the title suggests, that emphasis is all about getting back to basics. But as Watson has learned in his years as a performer and teacher, those basics aren’t always easy to master.

“I had this one musician, man, who asked me what I wanted to do tonight, and I says, ‘Man, I want to play some blues,’” he recalled. “Now, this was a person who was, technically, way out there, who played and wrote their own tunes. I just told him, ‘I want to play some blues,’ and the cat begged me not to. He got tears in his eyes. ‘Please, please, I suck! I don’t want to play the blues.’ And I’m like, are you kidding?”

Watson laughs as he tells the tale, but he understands the feeling. “The blues is something I think you have to grow into,” he said. Even though he grew up with the music—“It was blues on Saturday and gospel on Sunday,” he said—he understood early on that there was a difference between knowing the music and feeling it.

“I felt intimidated by the blues for many years,” Watson said. “With some people, I could tell they were feeling it from head to toe. I could play it, but I didn’t feel it the way they did. I felt like I was an impostor, you know?”

Given the stellar ascent of Watson’s career, that might seem hard to believe. Two years after graduating from the University of Miami, where classmates included Pat Metheny and Jaco Pastorius, the saxophonist joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. He was in the band from 1977 to ’81 (Branford Marsalis eventually took his place in the alto chair), and has released dozens of albums, both as a leader—often with his Horizon quintet—and as part of the 29th Street Saxophone Quartet.

Through all that, Watson was learning—not how to play the blues, but how to connect with the blues inside himself. “I can reach back to my childhood and realize that the blues has always been a part of me,” he said. “We didn’t listen to it around the house, but it was always there. Once I started to connect the dots, I realized where I fit [into] my version of the blues.

“The more seasons you get, you want to put that out there more,” he added. “You are who you are.”

It might be tempting for fans to imagine a connection between this emphasis on the blues and the end of the Horizon lineup, but Watson suggests a more prosaic culprit: success.

“As guys grow and their name starts ringing, they get gigs, man,” the saxophonist said. “And you can’t get ’em when you need ’em. Especially rhythm section players. [Horizon drummer] Victor Lewis used to put his drums in the Vanguard and leave ’em there for three weeks.”

Needless to say, this made booking dates a scheduling nightmare. “The last time we got together it took a year-and-a-half of planning ahead of time—for four gigs!” He laughed, and added, “And even at that, [bassist Essiet Essiet] couldn’t make it.”

Of course, with the new band—which, in addition to longtime collaborator Curtis Lundy on bass and veteran Victor Jones on drums, includes Victor Gould on piano, and either Giveton Gelin or Josh Evans on trumpet—booking a tour poses a different challenge: There’s no place to play.

Like the rest of us, Watson has no idea how the pandemic is going to play out, but he thinks we’ll all get through this. “[Everyone will] make adjustments,” he said. “I mean, mankind survived bubonic plague and malaria and all this other stuff. I figure it’s just a matter of being patient.”

And in the meantime, there’s always the blues.

“I started playing a blues on my gigs several years ago,” he said. “Just a blues. I call it ‘Up To The Minute Blues,’ based on this week’s current events. And I start preaching on the horn.” He sings a blues phrase to the lyrics, “I just saw Donald Trump. Oh, what a dummy he is.”

He laughs. “Obviously, I’m just thinking as I play. ‘He’s a jive motherfucker ... .’” He laughs again. “That’s what will be going through my head when I’m playing those slow blues. I just start telling people about my day.” DB

https://www.nytimes.com/1993/05/03/arts/review-jazz-bobby-watson-leads-his-own-big-band-revival.html

Review/Jazz; Bobby Watson Leads His Own Big-Band Revival

A year and a half ago, Bobby Watson pulled together some big-band arrangements he had been working on, took them to Columbia University's jazz orchestra and led the orchestra in a surprisingly successful concert. Mr. Watson, known as a saxophonist and composer, had big-band aspirations, not a fruitful thing to have, given jazz's generally enfeebled economic situation. The concert, often brilliant, looked as if it was set to go down in legend, a one-time event making Mr. Watson one of those rare jazz composers lucky enough to hear their music played by a large ensemble, if only for one night. With big bands seemingly relegated to the dustbin of history, the music was destined for the security of Mr. Watson's desk drawer.

But the current jazz renaissance has had all sorts of salutary effects, not the least of which is a flowering, albeit small, of interest in big-band music among both audiences and musicians. Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall both have jazz orchestras; Jimmy Heath and Slide Hampton have started large ensembles recently, and Wynton Marsalis moves closer to fronting a big band every year. Illinois Jacquet's orchestra was one of the highlights of the 1980's, and the American Jazz Orchestra, David Murray's big band and Clifford Jordan's orchestra have all offered exceptional music. Along comes Mr. Watson, who has just released his first album on Columbia Records, "Tailor Made," which happens to be a big-band album.

Mr. Watson brought roughly the same band heard on the album into the Village Vanguard for three nights, and on Friday night, for its first show, it played surprisingly fluid music. Over the last 15 years, Mr. Watson has been producing some of jazz's most optimistic compositions, first with Art Blakey and then with a series of his own groups. His pieces resonate with a type of blues sunniness, in which small bits of bitterness make his optimism seem realistic. Small-group arrangements and compositions don't always make an easy transition to large ensembles, but on Friday night, Mr. Watson's pieces metamorphosed into big orchestrations, with the main themes underlined and surrounded with all sorts of asides, punctuations and embellishments.

There was a real ingenuity to the material. The band dropped away occasionally, leaving Mr. Watson and several saxophonists to perform unaccompanied, or he would let the band drift into honking discord, or set up soloists improvising against one another. At times the band drifted into light Latin jazz, which kept it from swinging as hard as it should and accentuated a prettiness that seemed more like Hollywood than New York. But for the most part, Mr. Watson's music maintained his own elemental harmonic personality. And Mr. Watson, his improvisations voluminous and flaunting a ripe and fleshy tone, kept the show tense and exciting.

Bobby Watson Jazz Quintet

Bobby Watson is a post-bop jazz alto saxophonist, composer, producer, and educator, with 26 recordings as a leader to his credit. He appears on nearly 100 other recordings as either co-leader or in a supporting role and has recorded more than 100 original compositions.

Watson grew up in Bonner Springs, Kansas, and Kansas City, Kansas. He attended the University of Miami along with fellow students Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius and Bruce Hornsby. After graduating in 1975, he moved to New York City and joined Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. The Jazz Messengers, sometimes referred to as the "University of Blakey", served as the ultimate "postgraduate school" for ambitious young players. He performed with the Jazz Messengers from 1977 to 1981, eventually becoming the musical director for the group.

After completing his tenure as a Jazz Messenger, Watson became a sought after musician, working along the way with many notable musicians, including: drummers Max Roach and Louis Hayes, fellow saxophonists George Coleman and Branford Marsalis, multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers and trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. In addition to working with a variety of instrumentalists, Watson has served in a supporting role for a number of distinguished and stylistically varied vocalists, including: Joe Williams, Dianne Reeves, Lou Rawls, Betty Carter, and Carmen Lundy, and has performed as a sideman with Carlos Santana, George Coleman, Rufus and Chaka Khan, Bob Belden and John Hicks.

Later, in association with bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Victor Lewis, Watson started the first edition of Horizon, an acoustic quintet modeled after the Jazz Messengers but with its own slightly more modern twist. The group recorded several titles for the Blue Note and Columbia record labels.

In addition to his work as leader of Horizon, Watson also led a group known as the High court of Swing (a tribute to the music of Johnny Hodges), The Tailor-Made Big Band (16 pieces in all) and is a founding member of the 29th Street Saxophone Quartet, an all-horn, four-piece group with alto saxophonist Ed Jackson, tenor saxophonist Rich Rothenberg, and baritone saxophonist Jim Hartog. Watson also composed an original song for the soundtrack of Robert De Niro's A Bronx Tale.

A resident of New York for most of his professional life, Watson served as a member of the adjunct faculty and taught saxophone privately at William Paterson University from 1985 to 1986 and the Manhattan School of Music from 1996 to 1999. He is currently involved with the Thelonious Monk Institute's yearly "Jazz in America" high school outreach program. In 2000, he was approached to return to his native midwestern surroundings on the Kansas-Missouri border. Watson was selected as the first William D. and Mary Grant Distinguished Professorship in Jazz Studies.

He has served as the director of jazz studies at the University of Missouri—Kansas City Conservatory of Music, although he still manages to balance concert engagements around the world with his teaching responsibilities. Watson's ensembles at UMKC have garnered several awards and national recognition.

Bobby Watson

A saxophonist, composer, arranger and educator, Bobby Watson grew up in Kansas City, Kan. He trained formally at the University of Miami, a school with a distinguished and well-respected jazz program. After graduating and still not yet 25, he proceeded to earn his "doctorate" – on the bandstand – as musical director of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. The seminal hard-bop group, created in 1955 by late legendary drummer who died in 1990, showcased a rotating cast of players, many who, like Watson, would go on to have substantial careers as influential musicians and bandleaders in their own right. The Jazz Messengers – frequently referred to as the "University of Blakey" – served as the penultimate "post-graduate school" for talented, ambitious young players, which certainly describes Watson.

After completing a four-year-plus Jazz Messengers tenure (1977-1981), encompassing hundreds of performances and appearing on 14 recordings, Watson became a much-sought after musician. Some, but certainly not all, the notable musicians – peers, elder statesmen and colleagues all – he worked with during this period include drummers Max Roach and Louis Hayes, fellow saxophonists George Coleman and a younger Branford Marsalis, celebrated multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers and a then-young trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who is a full 10 years the saxophonist's junior. In addition to working with a variety of instrumentalists, Watson served in a supporting role for a number of distinguished and stylistically varied vocalists, including: Joe Williams, Dianne Reeves, Lou Rawls, Betty Carter and Carmen Lundy.

Later, in association with bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Victor Lewis, Watson launched the first edition of what would become one of his key calling cards: Horizon, the acoustic quintet he modeled in many ways after the Jazz Messengers – but a unit that possessed a distinct slightly more modern twist. Throughout the years Horizon's personnel rotated somewhat, however it has always stayed top-shelf; the group's repertoire at any given time is overwhelmingly comprised of original compositions. Long-standing, talented members, now established include pianist Ed Simon, trumpeter TereIl Stafford and bassist Essiet Okon Essiet. By all critical accounts, Horizon, which today still performs together on special occasions, is now thought of as one of the preeminent small groups of the past three decades. The group issued several highly acclaimed titles for Blue Note Records and then for Columbia Records. Among the band's releases: Post-Motown Bop (Blue Note) and Midwest Shuffle, Live! (Columbia), the latter a live recording capturing the group in a number of locations during a 1993 tour.

In addition to his work with Horizon, Watson also led a nine-piece group known as the High Court of Swing – a tribute to the music of Johnny Hodges – as well as the GRAMMY®-nominated, 16-piece large ensemble Tailor Made Big Band. The lyrical stylist is also a founding member of the well-respected 29th Street Saxophone Quartet, an all-horn, four-piece ensemble. Watson's classic 1986 release, Love Remains (Red) received a special citation in the Penguin Guide to Jazz (Penguin). Having received the publication's highest rating, the Love Remains was then identified in the ready reference book's seventh edition as a part what the editors considered its "core collection" [i.e. a "must-have"], thereby joining other entries issued by a number of jazz masters and icons.

More recently, Watson issued a series of recordings on the Palmetto label. On the heels of his #1 releases, Live & Learn (2005) and Horizon Reassembled (2006), where he's reunited with Lewis, Stafford, Simon and Essiet, the saxophonist issued From the Heart (2008), where he unveils yet another original project, again sharing the limelight with bassist Lundy. The release also went to #1 on the national jazz airplay chart and remained there for nine weeks.

For essentially four decades now Watson has consistently contributed intelligent, sensitive and well-thought out music to the modern-day jazz lexicon. All told, Watson, the now-seasoned veteran, has released more than 30 recordings as a leader and appeared on close to 150 other recordings, either performing as co-leader or in support of other like-minded musicians. Not simply a performer, the saxophonist has recorded more than 100 original compositions including the music for the soundtrack of A Bronx Tale, which marked Robert DeNiro's 1993 directorial debut. Numerous Watson compositions have become classics such as his "Time Will Tell," "In Case You Missed It" and "Wheel within a Wheel," with all three titles becoming oft-recorded and interpreted by his fellow musicians.

Bobby Watson, Educator

It's ever-more apparent with each passing year that in addition to his compositional and performance prowess, Watson is equally respected as an educator. More importantly, Watson now inspires and passes on his great knowledge to those a generation or more younger than himself; like his former boss Blakey, Watson does both on and off the bandstand. His teaching within known jazz programs and institutions dates to the mid-1980s when Watson served as a member of the adjunct faculty and taught private saxophone at William Paterson University (1985-1986) and Manhattan School of Music (1996-1999).

In 2000, Watson hit his stride in the educational field. The saxophonist, after using New York as home base for 25 years, came full-circle and returned to Kansas City. Offered an endowed chair as the first William D. and Mary Grant Distinguished Professorship in Jazz Studies and assigned to serve as Director of Jazz Studies at the University of Missouri-Kansas City's Conservatory of Music & Dance., Watson took the appointment to heart. He set out a plan that, over time, would increase UMKC's Jazz Studies Program's visibility. Nearly 15 years later he's still at it, however it's now fair to say that Watson's program is now considered among the top-tier college/university jazz programs in the country. As a result, he's able to attract much the city's measurable home-grown talent as well as draw interest from many other gifted aspiring younger musicians located throughout Missouri, the Midwest region and the nation.

Watson capped off the millennium's first decade conceptualizing and then delivering one of his most ambitious and personalized projects to date – one where he combines all of his talents: composing, arranging, producing, teaching and performing. In fall 2010, the saxophonist released his self-produced, seven-part, all-originally composed The Gates BBQ Suite. The recording went to #4 on national jazz radio Airplay. The selfless Watson designed this complex work – which draws upon his childhood remembrances and experiences centered on his family's involvement in the business and his home-town's semi-official food – to primarily showcase his students. Arranged as a big-band endeavor, with Watson only playing sporadically, The Gates BBQ Suite houses an abundance of ensemble playing and solos from those who study with him.

"The Gates BBQ Suite, performed by Mr. Watson and the University of Missouri at Kansas City Concert Jazz Orchestra, is quite likely the most K.C.-specific work of his career thus far," wrote Will Friedwald in the Wall Street Journal. "It is, in every way, a worthy companion to the most famous long-form work celebrating jazz in that city, the 1960 ‘Kansas City Suite,' written by Benny Carter for Count Basie (neither of whom were K.C. natives, although Basie was easily the single greatest ambassador for K.C. jazz). In 1992," continued Friedwald, "when Mr. Watson produced his first big band album, Tailor Made, Columbia Records trumpeted that the sessions were completely unrehearsed – as if that were somehow a positive thing; here it's abundantly clear that Mr. Watson and his students have ample rehearsal time to get everything right..."

Just releasing the recording was not enough for the enthusiastic Watson. Using guile and his boundless creative energy, he was able to create an opportunity for him and his students to travel to Japan for a 10-day tour that showcased Gates and other compositions. To say they were well-received would be a serious understatement; not surprisingly, the group was extremely well-received.

Bobby Watson, Present Tense

Watson remains tremendously busy during 2014. The saxophonist has now made each of Gates' seven charts available to band directors around the world, arranged in such a way that they could be played in long-form as the entire suite or performed as stand-alone compositions. This year he also released his latest self-produced project, the well-received Check Cashing Day. Wrote Downbeat's Frank Alkyer, "On Check Cashing Day, saxophonist Bobby Watson is at his best, tackling the issue of inequality in the most positive, powerful and uplifting way possible." The thematic recording, commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Martin Luther King's "I Have A Dream" speech, is yet another heart-felt undertaking, this time successfully melding instrumentals, vocals and spoken word.

Bobby Watson, Award Recipient

Of late, Watson has received a number of well-deserved awards recognizing his musical contributions during what is now a four-decade career. In 2011 the saxophonist was inducted into the Kansas Music Hall of fame. In 2013 he received the prestigious Benny Golson Jazz Masters Award from Howard University in Washington, D.C. Simultaneously Rep. John Conyers honored Bobby by officially recognizing his work in the Congressional Record.

The most recent recognition is perhaps the sweetest to date. On August 23, 2014, coincidentally his 61st birthday, Watson was selected to be among the first inductees into the newly created 18th and Vine Jazz "Walk of Fame." He joins Pat Metheny as the only other living selection along with a quartet of the city's jazz icons: Count Basie, Jay McShann, Charlie Parker and Mary Lou Williams.

As in-demand as ever, the lyrical saxophonist continues to balance teaching responsibilities with engagements at major venues throughout the world including appearances at clubs, festivals, on campuses and at Performing Arts Centers.

http://www.kcjazzambassadors.org/post/bobby-watson-jazz-messenger

Bobby Watson, Jazz Messenger

Updated: July 2, 2020

by Joe Dimino & David Basse

KCJazzAmbassadors

“Retirement, for me, will just be more touring. Doing more of what I was up to, before I landed in Kansas City. More writing, more practicing, more listening, more studying, more traveling and just getting back to where I was before. Getting ready to fly again.”

Bobby Watson 2020

You probably know by now that 2020 is the 100th Birthday of Charlie Parker. Here is Kansas City, there have been 5 years of events leading up to this moment. Then there was the Pandemic, and we all had a chance to settle in at home. But some of us have been moving so fast for so long, that settling in is not an option.

Take saxophonist Bobby Watson. The Smoke Sessions album, Bird At 100, began 2020 by topping the jazz charts. With such a powerful line-up, and the music of Charlie “Bird” Parker, this album had to be a fun to make. Recorded with Vincent Herring and Gary Bartz, Bobby Watson, hit it and has not stopped for long since. Bobby spoke with JAM magazine’s Joe Dimino in February, about where “it” was then.

Talk to me about Bird at 100.

It was fun to record this live album with 2 other alto players and I learned a lot, being around these guys. Especially Mr. Bartz as he turns 80. That's amazing!

What does it mean to you, to honor the Patron Saint of Jazz, Charlie Parker, here in his home and yours Kansas City?

The stars line up, you know. Bird at 100 is a once in a lifetime event. As I have been saying the past couple of years, it's a very blessed and fortunate time to play the alto saxophone and to be from Kansas City. I'm so happy to be a part of this celebration in so many ways.

Do you have an upcoming tour in the US and in Europe for the album, Bird at 100?

Well, once again, if the stars line up, we will be going to Poland!

The Polish musicians were here during the first week of February. We have made plans to go there with Vincent Herring and the band for a concert. The celebration will continue in August around the birthday of Bird. There is a concert scheduled in Buffalo, NY on August 29th, during their Charlie Parker Festival, and hopefully a concert at The Folly Theater, here in Kansas City, this November, in conjunction with the American Jazz Museum.

What are your thoughts on your 20-year tenure at UMKC?

It's been quite a ride being at UMKC. An incredible experience that changed my life in many ways. I have grown as a musician, able to access any type of music I’ve wanted to explore, the repertoire I have always wanted play.

The band presented the music of Oliver Nelson, Duke Ellington, Frank Foster and Jimmy Heath. We were able to bring in important living artists such as, Cuban saxophonist Paquito D'Rivera, and world class trumpeters Jon Faddis, Nicholas Payton and Sean Jones.

Kenny Drew Jr. came to Kansas City from his home in Florida as part of the program, (right before his untimely passing). Alumnus of Art Blakey’s Messengers, Curtis Fuller and Benny Golson honored us with their presence. And there was the legendary rhythm section players, Ron Carter and Joe Chambers, all part of the program.

Watching students grow as people, and as musicians is a thrill for me. Many of them have families now and most are still playing, or they are teaching at major universities. Nate Jorgensen is at the University of New Hampshire and Michael Shults is at the University of Memphis.

There was a positive learning environment created by my actions and the way I dealt with the musicians. I treated them as adults and professionals, not as students. I told them that the big band was mine. It was not a class. It was Bobby Watson's Big Band. Otherwise known as the Concert Jazz Band 303. In reality, they were in my band and I treated them as professionals. We had the chance to travel to Japan, Europe and all across the country.

Then there was having that band there. It was right. We made it to number 2 on the Jazz Week charts with our recording The Gates BBQ Suite. The other day, I was trying to make a list of all of students and, even I couldn't name them all . . . there are so many, it's overwhelming!

The thing is, I didn't do this by myself. I set the tone for the department and the environment that the students would have to work in. I would challenge them to get that flavor by using my experience and sharing that with them in a real-life manner. Then, we had a very supportive administration. Co-Director Dan Thomas was my right-hand man through the years, recruiting and remodeling the curriculum.

We had a very supportive faculty. Folks like Bob Bowman, Todd Strait, Gerald Spaits, Stanton Kessler, Roger Wilder and Marcus Lewis were all there. In the beginning we had saxophonist Horace Washington and drummer Mike Warren.

What are you going to miss the most?

Walking into work and hearing all of the music being played in the practice rooms in the morning! Some mornings you may not feel so up, but you walk in and say, “What could be better than this?” It's raining cats and dogs outside, it's 10 o'clock in the morning and we are getting ready to talk about some music. I hear all the students in there practicing. A big cacophony of sound. Man, I'm gonna miss that! I was up there today (2-24-20) teaching private lessons all day and the time just flew by. It's great doing something you love.

Kansas City has become a Destination City. It used to be a springboard. What do you think about that?

I agree with that. The older jazz community readily embraced these younger cats, they have been feeding off of their energy. I think they have inspired the older ones to create, because the younger ones have that energy. They are eager to learn and cut their teeth and get that experience.

So, these musicians and their energy have really fueled a whole renaissance here in Kansas City. Most of the guys that came here from out of town ended up staying. Kansas City is a great place to live and there is a whole lot going on here.

It is a destination city. I believe there will be some musicians from the east coast that will be moving out this way, because of the scene and the openness of the musicians here. The cost of living is so good. Students can live well here. It's been wonderful. It's beyond my wildest expectations.

You are leaving the program in good hands with Trombonist Mitch Butler. Certainly, this tradition will continue.

Oh yes. He came in here from South Carolina. Yeah, people are coming here. We have people like Dominique Sanders producing in the R & B and Hip-Hop worlds, as well as jazz. He's in California and now he's in South Africa working on a big project. Herman Mehari resides in France for a good portion of the year and comes back and forth.

It's just incredible to see. I feel very fortunate. During the time when I came back here, I always said it's a great time to be in Kansas City. It's growing. So many positive things are happening, since I have been back. The whole community has embraced me, along with the students. It's been like a dream come true.

Many times, in life we are only as good as the shoulders we stand upon. Who was the biggest mentor in your life?

Without a doubt it was Art Blakey. The Jazz Messengers were an institution. It was a jazz finishing school, where you got your graduate degree. He saved so many young musicians like me; I would’ve spent at least 10 years searching around, it was the way he laid it out, he taught by example, and that's what I have always tried to do when I teach.

I always keep my horn in the students' faces. I taught by example. I didn't want to be a talking head at the blackboard. I can demonstrate. I think that is very important. As a jazz musician, I could demonstrate what I was talking about. That really earns respect from the students.

You can talk about it, but they actually want to hear you do it. That has always been very important to me. To be able to demonstrate what I'm talking about, no matter what I'm talking about.

That motivates them to go and try and see that it's possible.

Then, bringing in guest artists of all ages, that the students can see and hear them play. They would see the older musicians, and the students would say sure he can do it, cause he's old. Then, I would bring in the younger ones, that could do it as well.

Then they would say, “I guess we better get on it.” Just because you're in Kansas City doesn't mean that you shouldn't have that drive and dedication and that focus.

I would tell the kids all the time that there are people all over the world your age practicing right now and there's no reason you can't be doing that right here in Kansas City.

You know, Kansas City itself is a big recruiting tool. You know they have nice schools out in Des Moines or Kalamazoo, but they don't have a scene. You have to drive hours to get to Chicago, or Memphis, or Cleveland. But, right here, it's right here.

This city is an international destination for tourists and artists. It makes recruiting for the UMKC Jazz Program so much easier.

The students have been our biggest recruiter over the years. When they get here, they tell their friends and then the friends come in, from places like St. Louis, Southern California, the East Coast, Texas, Minneapolis and Chicago. We get students from all over.

There's probably no better person to ask this. As an educator, recording artist and performer, how is jazz as an organism in 2020?

It's a very healthy and strong organism. I think the most important thing for the young musicians coming up, is to get experience and to keep reaching out to the older musicians. I tell the young musicians that I was their age once, but that they have never been mine. I understand what I needed at their age, so we are trying to give it to them, too. It's our duty to pass it on. It's so great that there are so many performers and players that can walk the walk, as well as talk the talk, inside of academia in schools all over the country.

A typical retirement is likely a lemonade on the front porch. But things will be different for you. What does retirement look like for Bobby Watson?

More touring! I was just in New York last week. And the week before that I was touring with my group, Horizon and we were up in Pittsburgh, then Vermont and down into Maryland. We did several nights at Dizzy's Coca-Cola, the nightclub at Jazz in Lincoln Center, in New York City.

I did another recording last week, in New York for Smoke Sessions Records. A quintet date this time, due to be released July 16th, in Kansas City. 444

Retirement, for me, will just be more touring. Doing more of what I was up to, before I landed in Kansas City. More writing, more practicing, more listening, more studying, more traveling and just getting back to where I was before. Getting ready to fly again.

What do you like best about being a performer on stage?

I like to take the audience on a journey, making them forget about time and uplifting them with the music. I love feeling their appreciation for hearing live, acoustic jazz and knowing that jazz is still a vital and viable art form, in terms of swinging. Just knowing there is a proven formula for this acoustic music, that works all over the world, is enough for me.

It's great, to get a crowd that didn't think they could hear great jazz anymore. We're holding up the banner! I just love playing for people that are listening and enjoying.

It's not the opera. So, if they want to stand up and start clapping, start dancing a little bit. It’s O.K. We want to move people.

As Art Blakey used to say, jazz will, “Wash away the dust of everyday life.”

I want the audience to look down at their watches and say, “Oh wow, where did the time go?”

What was the first live jazz show you saw in person that made you think that you wanted to get on stage and do the same thing?

Believe it or not, the first one I ever saw was the Buddy Rich Big Band when Richie Cole was in the band, back in Minneapolis. Then, I saw Phil Woods, Count Basie, Weather Report and The CTI All Stars, here in Kansas City with Freddie Hubbard and Stanley Turrentine. I saw Grover Washington back in the day, down at Union Station when they used to have jazz down there.

Let's say you have a dream tonight and you run into a younger Bobby Watson around say your late 20's to early 30's, what advice will you give that younger version?

That's a good question. I would say don't worry. Be patient. Keep the faith. Stay positive. Stay humble. Keep that horn in your mouth and everything else will work out fine.

Why do you love jazz?

I love it because I can express things on my horn with feelings and emotions that I cannot put into words. Whether it be sadness, joy, reminiscing or projections of the future that I can express through music when words don't work. Jazz is the perfect vehicle for that. When you are up there on stage, you are naked and you're baring your soul. It takes a lot of courage and I like that. You're out on a limb. You don't know what's going to happen. You don't know what's going to happen each day even though you know the music, because it's always different. It's always fresh.

Everyone has their perception of who they think you are. Your family, friends, students and fans, but you know yourself best.

Who do you think you are?

I'm a messenger. I'm like a pied piper. I want to try to bring people into the music. I want to try to heal people through music. I'm just a messenger. I'm a scribe. When I write the music, I hear it and write it down before I forget it. They call it being a composer. You have to have certain skills of the craft as they call it, but basically, I'm a scribe.

I heard an interview on the radio recently and you were quite profound about the importance of taking in water. As a musician and just a regular person. Can you elaborate on that?

I was talking about water being the new oil of this millennium. So many people don't drink enough water. That's the thing I learned over the years and that's to drink a lot of water. It helps so many things in your body. You can drink tea, energy drinks or juices, but it's not water. Water is the pure fuel for your body. I encourage everybody to drink more water.

It's going to be at a premium. I remember when they first started to bottle water and that was weird. We were up in Vermont the other day and it's hard to find bottled water up there. I said, ‘Hey we are in Vermont and can drink the water right out of the tap’.

Believe it or not, Manhattan (NYC) has some of the cleanest water in the country.

What do you like the best about Kansas City?

I like the open space. I like the pace. People are friendly here. It's my home, so it's hard to say. I'm home now. I feel like this is my home. We were lucky enough to be here for my parents. We were with them until the very end and that was very important.

I have had offers to put my name in the hat for other jobs at places like Julliard, UCLA, Chicago or Oberlin, but I told them all that I'm home now. I don't want to leave.

I love the wide-open skies. I love the sound of the trees and the wind. I love the clouds, too. Those are like our mountains. It's just beautiful here. I love the four seasons. It's great here. I just love it. I will always love New York, but I can't wait to get back. I last about two weeks, then I want to come back. I need to come home.

Bobby Watson and UMKC

“Around the turn of the century, William and Mary Grant wanted to create a Jazz Professor Chair in the UMKC Department of Music and Dance. Everyone,” said Herman, “even a non-musician, can tell that Bobby is an extraordinary musician. When there is music being played, Bobby can find a spot with ALL musicians, age, race, social status and musical styles don’t matter.”

It was Mike Herman, whose brother had a career in jazz, who introduced Bobby to Mr. and Mrs. Grant. He told them, “He’s a really good guy, from Kansas City.” For decades Mike and his wife, Karen have been funding UMKC music scholarships.

“Part of the fun,” said Herman, “is having lunch with the students and getting to know them and their education. They all LOVE Bobby.” Herman said the students all say they learned more from Bobby Watson than any teacher they have known. “Extraordinary person. Extraordinary teacher,” said Herman, “Bobby leaving UMKC is a great loss.”

A special thanks goes to Mike & Karen Herman and the many scholarships they have created through Herman Jazz Fellows in support of Bobby Watson’s years at UMKC. Herman’s response, “Kansas City’s music scene has truly benefitted from his presence.”

After Raising A Generation Of New Kansas City Jazz Musicians, Bobby Watson Is Hitting The Road

Saxophonist Bobby Watson has loved teaching at the University of Missouri-Kansas City conservatory, but he is ready to concentrate on the touring and recording that have made him an international jazz legend.

“It’s been a great 20-year chapter,” Watson says of his two decades as the first endowed jazz studies professor at the UMKC Conservatory of Music and Dance. “I think life is divided like chapters, so I’m ready to fly again.”

He’ll retire from academia at the end of the 2019-2020 school year, although he plans to remain involved with the conservatory in some capacity.

He’s preparing for a new recording in New York early next year and plans a tour through Europe next summer.

This decision comes with mixed feelings, Watson said, in a wide-ranging interview on KCUR’s Up to Date.

“I love the conservatory and the work they do there and the faculty,” he said. “I think we have a world-class faculty there and our students are also world-class. And that part is bittersweet for me.”

At age 66, Watson said it’s the right time for him to devote to performing, composing and recording.

Teaching a generation

Watson has trained more than 100 musicians since he arrived at UMKC in 2000 and has helped define the Kansas City jazz scene throughout that time.

He said it’s been tremendously rewarding to teach a generation of students who have taken their talents all over the country. A great joy has been having a “captive band” of conservatory musicians, with whom he could try out his compositions.

“It was a great palette to try things and work on material,” he said.

One of those compositions was the “Gates BBQ Suite” dedicated to Kansas City barbecue magnate Ollie Gates, who has been one of Watson’s biggest supporters.

Watson praised the conservatory’s Concert Jazz Orchestra for turning in a terrific performance that made the national jazz airplay charts.

“He (Gates) loved it,” Watson said. “He was thrilled and that made me very happy. That was one of my bucket list things I wanted to do.”

Watson is enormously proud of his students but acknowledged that his teaching duties have been demanding.

“Going into school and giving your all and really being genuinely concerned about these young people’s lives requires a lot of energy, and they take a lot out of you, in a good way,” he said. “I tell my students, ‘I probably think about you more than you think about yourselves.’”

He said the conservatory faculty members dedicate themselves to giving their students individual attention, not just providing a “talking head, cookie-cutter approach” to teaching.

Musical roots

Watson grew up in Kansas City, Kansas, and started taking piano lessons at age 10. He was born into a musical family and fondly recalls hearing his father play saxophone and his mother play piano in church. His first public performance was playing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” on clarinet in church.

He attended junior high and high school in Minneapolis, where he learned saxophone. Watson attended the University of Miami at the same time as Pat Metheny and Bruce Hornsby. He graduated in 1975 and moved to New York to begin his professional career. It was there that he learned from and performed with jazz greats Art Blakey, George Coleman, Louis Hayes, Max Roach and others.

In 2000, he was approached to return to his Midwestern roots and was named the first William and Mary Grant/Missouri Distinguished Professor in Jazz Studies at UMKC. He also maintained a worldwide performing schedule.

Watson said he and his wife, Pamela Baskin-Watson, who is also an accomplished musician, are looking forward to moving into a new home in Lenexa. Pam is a pianist, composer and vocalist. Watson says she has a musical piece premiering in New York next month.

Watson believes the conservatory and jazz studies program will continue to thrive, with the hiring of trombonist Mitch Butler, and other excellent faculty members.

“It’s in great hands. It’s new blood, new enthusiasm,” he said. “It’s about the institution and the fine faculty that the institution maintains.”

Bobby Watson is a jazz studies professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music and Dance and an internationally renowned performer and composer. He spoke with KCUR 89.3 on a recent edition of Up To Date.

Lynn Horsley is a freelance journalist and was a veteran reporter for The Kansas City Star. Follow her on Twitter @LynnHorsley

https://www.furious.com/perfect/bobbywatson.html

BOBBY WATSON

Interviews by Alexander McLean

(June 2015)

Kansas native Bobby Watson has done a lot of living at age 61. The

saxophonist started young but his real education came in Art Blakey's

Jazz Messengers in the late '70's, going on to work with jazz legends

like Max Roach and the Marsalis Brothers as well as backing up notable

singers like Joe Williams, Dianne Reeves, Lou Rawls and Betty Carter.

Watson went on to form his own group, Horizon, in the mid '80's,

recording albums for Blue Note among other places as well as leading

larger bands like High Court of Swing (honoring Ellington sax man Johnny

Hodges) and the Tailor Made Big Band. He also became an award-winning

educating, teaching in NYC and back home in Kansas also, with a number

of his own students featured in some of his bands.What we have below is a series of six video interviews with Watson, all done in May 2015, on the morning before his show at Ronnie Scott's in London. In the course of 28 minutes, he covers everything from the beginning of his own career (playing in church), his health, his most recent album (2013's Check Cashing Day), his thoughts on working with jazz greats Sam Rivers, Max Roach and Wynton Marsalis as well as a famous actor you've probably heard of, who he calls 'a frustrated saxophone player.'

Thanks to photographer Siobhan Bradshaw for her help with the videos.

Bobby Watson

Watson studied music at the University of Miami. After graduation, when the opportunity arose for an education with Art Blakey, Watson grabbed it and spent five years as a Jazz Messenger, eventually becoming the band's musical director. Watson did the same thing Benny Golson did for Blakey in the late 1950s, he helped kick-start a group that had become stagnant. He also brought to the group his energetic playing and something else Blakey needed, a songwriter to fit the Messenger groove. The best example of Watson's contribution to the Messengers is displayed on Album of the Year, featuring the best of Blakey's later bands, including a precocious trumpeter named Wynton Marsalis.

After leaving Blakey in 1981, Watson formed the first edition of his long-running band, Horizon. Watson demonstrated his diversity working as a sideman in George Coleman's hard-bop octet, Sam Rivers's experimental Winds of Manhattan ensemble, and drummer Panama Francis's Savoy Sultans. Watson was having a hard time finding a label to record his band, so he and bassist Curtis Lundy formed their own label, New Note, in 1983. A few years later, Watson helped found the 29th Street Saxophone Quartet.

He signed with Blue Note in the late 1980s and a few years later switched to Columbia where he recorded both small group sessions and an album with the big band he formed in early 1990s. print, good dates to explore exist. Watson has a bit of a populist streak, which some critics have unfairly dismissed as being facile. The alto player has a good dose of old school appreciation for creating solos that capture attention, sometimes with burning intensity or sweet lyricism, occasionally with humor. Like Horace Silver, Watson isn't afraid of writing slick, finger-popping, catchy melodies as vehicles for improvisations. One of Watson's strongest albums is Love Remains (Red Records, 1988), a quartet recording with pianist John Hicks, bassist Curtis Lundy, and drummer Marvin Smith. The album has its requisite cookers like "The Mystery of Ebop" and "Sho Thang." The title composition is one of Watson's most beautiful pieces ever, demonstrating the depth of emotion he can create when he puts his mind to it . The same band made an album under Hicks's name, Naima's Love Song (DIW, 1988), which is worth grabbing.

Biographical Sketch

Unlike the Bird's generation, Bobby Watson came up a surer and more measured path. He trained at the suggestion of his friend guitarist Pat Metheny at the University of Miami along with Jaco Pastorius, Bruce Hornsby and Danny Gottlieb. Then he got his doctorate as the musical director of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. Along the way, he worked with drummers Panama Francis, Max Roach and Louis Hayes with saxophonist George Coleman as well as Sam Rivers' avant-garde Winds of Manhattan.

In association with drummer Victor Lewis, Watson launched the first edition of Horizon, his accoustic quintet. He's also led the High Court of Swing, a tribute to the music of Johnny Hodges and the highly-acclaimed 29th Street Saxophone Quartet. By the late 1980s, Watson had become one of the best-kept secrets in jazz. His CD, Present Tense was hailed by Peter Watrous in Musician Magazine "as one of those perfect albums" and he recorded Tailor Made, a 17-piece big band project that broadened his artistic vision and his audience.

Bobby has consistently topped the critics' as well as the readers' music polls. Somehow Bobby has also found the time to interpret the works of Debussy and Chopin on Pride of the Lions and to produce several younger artists including Ryan Kisor and David Sanchez. He also composed original music for Robert DeNiro's directorial debut film, A Bronx Tale.

Never one to stand still or to be limited by categories, Bobby has added tenor saxophone and flute to his arsenal and is on to New Horizons, and Urban Renewal.

https://www.onestopjazzcollective.com/artistprofiles/bobby-watson

Bobby Watson

A saxophonist, composer, arranger and educator, Bobby Watson grew up in Kansas City. He trained formally at the University of Miami, a school with a distinguished and well-respected jazz program. After graduating, he proceeded to earn his "doctorate" – on the bandstand – as musical director of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. The group, created in 1955 by late legendary drummer who died in 1990, showcased a rotating cast of players, many who, like Watson, would go on to have substantial careers as bandleaders in their own right. The Jazz Messengers – frequently referred to as the "University of Blakey" – served as the ultimate "postgraduate school" for ambitious young players.

After completing a four-year-plus Jazz Messengers tenure (1977-1981) that incorporated more than a dozen recordings – the most of any of the great Jazz Messengers, the gifted Watson became a much-sought after musician, working along the way with a potpourri of notable artists – peers, elder statesmen and colleagues all -- including, but not limited to: drummers Max Roach and Louis Hayes, fellow saxophonists George Coleman and a younger Branford Marsalis, celebrated multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers and trumpeter Wynton Marsalis (who joined the Jazz Messengers at least in part at the suggestion of Watson).

For more than three decades now Watson has contributed consistently intelligent, sensitive and well-thought out music to the modern-day jazz lexicon. All told, Watson, the immensely talented and now-seasoned veteran, has issued some 30 recordings as a leader and appeared on 100-plus other recordings, performing as either co-leader or in support of other like-minded musicians. Not simply a performer, the saxophonist has recorded more than 100 original compositions including the music for the soundtrack of A Bronx Tale, which marked Robert DeNiro's 1993 directorial debut. Numerous Watson compositions have become classics such as his "Time Will Tell," "In Case You Missed It" and "Wheel within a Wheel," each now oft-recorded titles that are interpreted by his fellow musicians both on the bandstand and on other recordings.

NAMM Oral History Spotlight: Bobby Watson

Legendary saxophonist and Kansas City native, Bobby Watson, received his post-doctorate in jazz while on the bandstand with famed drummer Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. After completing his four-year tenure with the Jazz Messengers, sometimes referred to as the ‘University of Blakey,’ Watson went on to have a substantial career not only as a bandleader and performer but as an important figure in jazz education.

As a performer, Watson collaborated and was sought out by many notable artists, including drummers Max Roach and Louis Hayes, fellow saxophonists George Coleman and Branford Marsalis, and at the time, up-and-coming trumpeter, Wynton Marsalis. Watson also played many supporting and stylistic roles for vocalists like Joe Williams, Dianne Reeves, Lou Rawls, Betty Carter, and Carmen Lundy. As a bandleader, Watson founded Bobby Watson & Horizon, alongside fellow bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Victor Lewis. The group performed throughout the 80s and 90s and, in many ways, was modeled after the Jazz Messengers but with a distinct, modern twist.

During this time, Watson also began his role in jazz education and like the masters before him, began passing on his great knowledge. His teachings within prestigious jazz programs and institutions began when he served as a faculty member and private studio teacher at William Paterson University (1985-1986) and the Manhattan School of Music (1996-1999). At the millennium, Watson found himself at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music and Dance as the Director of Jazz Studies and after two decades in the position, Watson retired in 2020 from academia and returned to recording records. Watson’s newest project, Keepin’ it Real, was released in June 2020 and further extended the Jazz Messenger’s legacy with a reincarnation of Watson’s original Horizon band featuring Curtis Lundy on bass.

Watson sat down with Music Historian Dan Del Fiorentino in January of 2016 and shared some wonderful insight between being a jazz musician during his day versus today, as well as an important message for young jazzers and musicians. Watson explained that young musicians should always “keep your ear to what’s going on,” not just to your genre of music, because then you will be ready for any musical or artistic situation. He recalled how back in his day, it was the age of “Motown, Stevie Wonder, and James Brown,” and how he did a lot of funk and wedding gigs which had a profound impact on his versatility as a musician.

As a final piece of wisdom, Watson urged young musicians to tap into their “inner song.” He believes that musicians like Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and Herbie Hancock can be identified throughout different periods of their life as they were trying to “perfect this one song that [they] have inside of [them].” It is when we find this song, we can tap into what brings us joy while playing, and this is sure to translate to our audience.

AUDIO: <iframe width="640" height="360" src="https://namm.org/video/embed/380" frameborder="0" scrolling="auto" />

https://www.npr.org/artists/15898140/bobby-watson

Bobby Watson

Jazz Album of the Week:

Bobby Watson’s New Quintet and Old-School Mantra, Keys to Keepin’ It Real

December 28, 2020. Chasing stardom is a young man’s game. At 66, alto saxophonist Bobby Watson will tell you he’s much more interested in the zero-pretense ethos that doubles as the title of his new album.

“After you’ve lived a certain period of time you want to try to be yourself. You don’t want to BS people,” Watson said in Keepin’ It Real’s press release. “You become more committed to…the way you treat your band…what you stand for as a person.”

Watson learned the mechanics of building a band up and breaking it down before things got stale from the greatest to ever do it, Art Blakey. The Jazz Messengers’ music director from 1977 to 1981, Watson recorded over a dozen records with Blakey. The experience gave Watson heightened insight into knowing what’s best for the individual and also the collective. That’s why, for Keepin’ It Real, Watson’s re-tooled the personnel of the Horizon quintet he’s led since the late ’80s.

“The original Horizon had run its course,” said Watson, explaining the shake-up. “That’s why I wanted to start fresh, with new music, new personnel, fresh blood, and new energy.”

Aside from Watson and Horizon’s founding bassist, Curtis Lundy, everyone else is new. Goodbye, old Horizon. Hello, New Horizon.

Joining Lundy in the rhythm section are a pair of Victors, Jones (drums) and Gould (piano). Jones is hard-driving, always precise, and light when he needs to be, a perfect Blakey-style drummer. Gould, meanwhile, is as stylistically versatile as young pianists come and has played under some of Blakey’s most celebrated disciples—Ralph Peterson, Wallace Roney, Donald Harrison, and now Watson.

We first encounter one of the many shades of Gould on the album’s title track, a Watson original that speaks to Gould’s ability to play in the gospel-drenched blues of Zawinul (“Mercy, Mercy, Mercy”) and Kenny Kirkland (“Mo Better Blues”).

Of course, the immortal you’d expect to be invoked most frequently here is Blakey, and Watson does not disappoint there either. On former Messenger Jackie McLean’s “Condition Blue,” Watson and trumpeter Josh Evans, a McLean protégé, strike that Blakean hard-bop balance between clever gamesmanship and harmony.

If you’re looking for one that swings hard, no need to hire a detective. Simply set your bags down and luxuriate in “Elementary, My Dear Watson 2020.” If you fall asleep to this one, you’re inviting the ghosts of hard-bop’s past—Adderley, Chambers, Cobb, Tyner, et. al.—into the living room of your unconscious.

Nearly lost in the shuffle is pianist John Hicks. He’s not on the recording here. It’d be impressive if he were; he died 14 years ago. But it’s important to Watson and Lundy that he’s not forgotten. Lundy conceived of the original “Elementary,” a rudimentary groove over which Watson improvised the melody, in 1988 as the opener to Hicks’ Naima’s Love Song; both he and Watson were sidemen. Watson’s improvisations have since been formally incorporated to the composition, but that takes nothing away from the dynamism of Watson’s playing, which never becomes stilted as a result of what is or isn’t on the page.

If this more propulsive version of “Elementary” is a winking doff of the cap to Hicks, “One for John” is Keepin’ It Real’s explicit tribute Hicks’ playing, which Lundy and Watson likened to a 747 for the way it took flight. Watson and Evans again introduce things with vacuum-tight unison playing. Once airborne, Gould, Lundy, and Jones make the initial ascent as a piano trio before handing off to Evans for a solo. Mid-flight, Evans delivers a searing solo evocative of the late Roy Hargrove, another of Watson’s protégés. The biggest thrill comes on the descent, however, with one of the album’s few drum solos from Victor Jones.

The middle third of the nine-song set is its emotional core. These three tunes best exemplify what Watson’s idea of keepin’ it real is all about.

A cover of soul legend Donny Hathaway’s “Someday We’ll All Be Free” starts things off. Of particular weight at holiday-time, it speaks to several of Kwanzaa’s seven core principles, especially “Imani” (faith).

In Watson’s hands—as it was in Hathaway’s—it’s such a reassuring piece of music, a groovy pep-talk, a protective buoy when it feels like there are swollen seas all around you. With Gould taking to the Fender Rhodes in the spirit of verisimilitude, trumpeter Giveton Gelin providing the most memorable of his three appearances, and Watson displaying rare intonation and control in the upper reaches of his alto, it does the brilliant original justice. And, in its own right, this instrumental version might be the perfect vehicle for perseverance and optimism as we (hopefully) transition away from one of the darkest periods in recent memory.

Next is Charlie Parker’s “Mohawk” in a way you’ve never heard it before. Watson’s taken some liberties with this new arrangement, and those liberties represent the quintessence of what “keepin’ it real” means to Bobby Watson the musician.

“I’ve been playing Bird long enough now that I think I’ve earned some artistic license,” said Watson in the album’s release. “At this point in my life, I understand Bird’s music enough to make it mine.”

And that’s fair enough; last year’s collaboration with fellow altos Gary Bartz and Vincent Herring for Bird at 100 proved as much. It was during that session to commemorate Bird’s centennial that Watson came up with this arrangement of “Mohawk,” a deliberate, velvety potion of R&B-ish soul-jazz that presents more as Gamble and Huff than Bird and Diz. No doubt Grover Washington, Jr. would have felt right at home hopping out for a solo here. And if ever there were a year to raise the dead for the sake of a funky bridge….

Gould merits special mention here for doing the most with the stretched-out canvas Watson has presented. Monk didn’t have nearly as much room to stretch on the original—and he may not have wanted it—but this arrangement thoughtfully makes the best of Gould’s sensibility as a player. It’s a credit to Watson knowing his personnel.

Though there’s no member of the band Watson knows better than himself, and it’s the next one, “My Song,” that offers an unobstructed view directly into Watson’s musical soul. This one, Watson says, is closest to that one song that’s always inside of him, that succinct yet cumulative representation of everything he’s spent a career trying to say through his music.

With that kind of preface, you might expect something grandiose or overly complex. But Watson is a musical populist at heart. Just listen to the constant thwack issuing from the rim of Jones’ snare combined with the ostinato of the bass line—anyone else sensing some inspiration from Curtis Mayfield’s “Pusherman” or “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone”?

A deceptively simple head introduced in unison by Watson and Evans gives way to some of the most explosive solo work on the album, while the mesmerizing, chant-like work of the rhythm section is the perfect contextual jumping-off point for solos that are like steroids for the spirit, none more so than Watson’s principal excursion beginning just shy of the three-minute mark.

Keepin’ It Real closes with a sophisticated change-up in “Flamenco Sketches,” long a favorite of both Watson and Lundy, and “The Mystery of Ebop,” a tune reprised from Watson’s 1986 recording Love Remains.

The former is almost surprisingly lovely, not because you doubt the ability of any of these musicians to interpret Miles and Bill Evans but because it’s such an outlier among the other selections here; it’s really the only true ballad and comes on the heels of the frenetic-at-points “One for John.”

If you’re not expecting it, it’s like that sensation of going for a sip of what you believe to be water and getting literally anything else. Nevertheless, it’s gorgeous. Gould, Watson, Evans, Lundy, and Jones all have the requisite heart, head, and chops for a classic that is not easy to do well.

The latter is largely dedicated to the amazing things Victor Jones is capable of doing with a couple of sticks and a drum set. You might hear Marvin “Smitty” Smith; you’ll definitely hear Art Blakey. Also, the tribute-to-John-Hicks storyline comes full circle—it was Hicks on piano when Watson debuted the tune 34 years ago. It just goes to show that, with this music, whether you’re a branch off the Blakey tree or a branch of the Watson tree or share a common root system with both, though you may be gone, you’re never forgotten. And that’s keepin’ it real.

Bobby Watson - 'Blues For Peace' I The Bridge 909 in Studio

Bobby Watson KEEPIN' IT REAL EPK

Bobby Watson - 'The Full Session' I The Bridge 909 in Studio

Bobby Watson and the Jazz Messengers

We Fall Down by Bobby Watson

"Love Remains" Bobby Watson

Bobby Watson - Beatitudes

Bobby Watson. Wilkes BBQ